1. Introduction

Today, tourism stands as a pivotal engine of economic growth in many countries, contributing significantly to gross domestic product (GDP), employment, and export revenues. Recent data analyzed by the World Travel & Tourism Council [

1] show that the travel and tourism sector accounts for about 10% of global GDP and supports roughly one in ten jobs worldwide. Tourism sector contributes around 5–8% to GDP in many nations, with even greater impact in tourist-intensive states [

2]. In Europe, analyses of multiple countries over several decades reveal a long-term cointegrated relationship between tourism growth and economic performance: during non-crisis periods, increases in tourist arrivals and tourism receipts stimulate national incomes and employment [

3]. As an evidence, tourism functions not merely as a service industry, but as a strategic sector crucial to economic growth. Concerning crises periods, tourism faced dramatic disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic [

4], along with nearly all other economic sectors [

5,

6]. In terms of recovery capacity, the sector distinguished itself by rebounding more rapidly, showing an unusual resilience and adaptation potentials [

7]. Despite being highly labor-intensive and heavily impacted by travel restrictions, the sector recovered quickly (the paper shows that in the analyzed case studies arrivals and overnight stays approaching pre-COVID levels just three years after the breaking down), highlighting a critical role in supporting local economy and generating spatial transformations (land uses, urban functions, environmental/cultural values exploitation, etc. Tourism can be understood as a place-based economy. Unlike digital industries, it cannot be outsourced or delocalized, since its value is inherently tied to the uniqueness values of specific locations, their cultural heritage, and environmental resources [

8]. This spatial anchoring makes tourism both a powerful driver of local development and a sector that requires careful management to balance growth with long-term sustainability. Therefore, we consider tourism as a spatial phenomenon in the perspective of urban studies approach. Affirming that it is an important factor in local socio-economic development, representing a key driver of socio-economic development in host destinations [

9,

10] we may refer to tourism externalities as positive multiscale effects on economic systems but also potential pressure on local environmental and anthropic systems. In facts, it generates business opportunities, income, and jobs, particularly when visitors rely on local accommodations, restaurants, and cafés [

11] and it creates stronger links with the local economy and spreads its benefits more widely across the community [

12]. Alongside direct jobs, the sector generates a wide range of indirect externalities, from investments in mobility infrastructure, to support the valorization of cultural heritage, stimulate local entrepreneurship, and create infrastructure that benefits both visitors and residents [

9,

13,

14]. In several former industrial cities—such as Bilbao—tourism has been a key factor in economic regeneration [

15] shaping brand new trajectories for urban development in post-industrial cities facing degrowth and crisis. It represents a lesson orienting policy maker across Europe to increasingly target urban development strategy towards tourism-based development actions [

16]. Tourism inevitably is a driver for territorial transformations processes in a continuum under-the-surface process where huge transformations often require specific urban planning actions (localization agreement, urban regeneration plans, protection acts for sensible heritage etc.) but micro ones (the majority of local effects defining local chains of tourism supply) mainly run unplanned and boosted by digital platform more than traditional systems. These dynamics taking the form of micro-scale interventions range from the generalized reuse and valorization of underexploited real estate to the overexploitation of cultural and environmental assets. What might appear as isolated adjustments could accumulate into significant structural change, altering the balance between local needs and global visitor demand. In this case a gravitational territorial effect emerges in concentrating tourism value chains on localized major destinations. Yet in destinations where mass tourism has expanded rapidly, like Barcelona or Lisbon, the downsides have become visible [

17]. Here the lesson is simple: growth alone is not enough. Once visitor flows exceed tourism supply carrying capacity [

18], the economic, social, and physical pressures on cities can outweigh the benefits, creating new challenges for local communities and stakeholders.

Overtourism has emerged as a critical challenge in contemporary tourism, referring to the excessive concentration of visitors in specific destinations [

19,

20]. This phenomenon often leads to environmental pressures, erosion of cultural authenticity, and social tensions. Cities such as Venice, Barcelona, and Dubrovnik illustrate these impacts, facing increased pollution, rising housing costs driven by short-term rentals, and growing friction between local residents and tourists [

21,

22]. Seasonality further amplifies the challenges of tourism by generating economic instability and placing excessive demand on infrastructure during peak periods, while leaving businesses and workers exposed during quieter months [

23,

24,

25]. These seasonal fluctuations affect employment, overburden local resources, and lead to inefficient use of urban infrastructure. Addressing these issues requires sustainable management strategies that balance visitor flows with the long-term economic, social, and environmental health of destinations. These patterns highlight the spatial and temporal imbalances inherent in tourism systems, requiring specific planning tools and effective management approach to ensure that destinations remain both attractive and sustainable. Against those (unplanned) gravitational processes, recent tourism development policies had been oriented to counterbalance tourism effects toward minor destinations and inner areas. We refer to those adopted in Portugal—where Porto authorities have restricted new short-term rentals to underutilized neighborhoods as part of urban regeneration efforts [

26] or Italy’s PNRR attractiveness program (

https://www.italiadomani.gov.it/it/Interventi/investimenti/attrattivita-dei-borghi.html), which promotes small towns to improve attractiveness providing incentives to enhance the appeal of underdeveloped areas. These initiatives aim to relieve pressure on overcrowded tourist destinations by promoting lesser-known areas, thereby distributing visitor flows more evenly and supporting a more sustainable balance of tourism demand. In the view of this paper, we define this policymaking effort under the overall concept of anti-gravitation of tourism development. It represents a tentative concept derived from physics, allowing us to define operatively through robust methodology application (STESY) and case studies analysis a sustainable perspective to handle tourism planning in a specific tourism destination area.

The concept of “anti-gravity” in physics [

27,

28], which explores hypothetical forces capable of neutralizing or reversing the gravitational pull between matter and antimatter, offers an interesting metaphor to define the research for more sustainable tourism development trajectories in local policymaking [

29]. In this context, the most crowded tourist areas generate a sort of “gravitational field” that attracts the majority of visitors, creating congestion, overexploitation, and pressure on local resources. The “anti-gravity tourism” approach acts as a counterforce, redistributing flows toward less-visited areas and rebalancing the tourism system. Similar to physics experiments that search for unconventional components of gravity, spatial analysis allows us to identify high-density nodes and design targeted interventions to mitigate the negative effects of “tourist gravitation,” promoting more sustainable and widespread use of the territory

The concept of “anti-gravity tourism” refers to strategies aimed at mitigating the excessive concentration of visitors in traditional hotspots by redistributing tourist flows across a destination. It seeks to “lift” tourism away from saturated areas, balancing visitor pressure, reducing congestion, and promoting underexplored sites, ultimately contributing to more sustainable and resilient tourism systems.

From a territorial perspective, we propose it as representative of a territorial system configuration expressing a balanced distribution of the tourism phenomenon, aimed at redistributing positive impacts and externalities while mitigating congestion effects across different territorial scales. This article is structured to present both the conceptual framework and the applied methodology of tourism spatial analysis using the STESY model and orienting territorial design proposal to New Urban Agenda (NUA) [

30] compliance.

The analytical part of the paper describes the application of the STESY model to four distinct case study areas, with the aim of defining a spatial assessment of tourism ecosystems through a data-driven approach. After the identification of Destination Areas (DAs) through spatial clustering techniques obtaining the territorial articulation of tourism supply in each case study area. Thereafter we interpreted through the lens of the NUA principles the design phase in each case downscaling NUA design approach to translate global sustainability principles into context-specific strategies. In the result section, the comparison of these case studies allows us to operatively highlight the evidences of anti-gravity approach in planning tourism issues and identify potential design strategies grounded sustainable development vision. Conclusions propose a critical reflection on how anti-gravity concept could represents a way to classify a global effort in ensuring tourism sustainability through the definition of anti-gravitational tourism development strategies, designed to mitigate excessive tourism pressure and promote more balanced and sustainable local development trajectories.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological framework of this study is based on the STESY framework methodology by Gatto et al. [

31] oriented to define a spatial assessment of tourism ecosystems based on a data driven approach. We compared four case study areas in order to highlight main tourism issues and potential design strategies based on NUA principles.

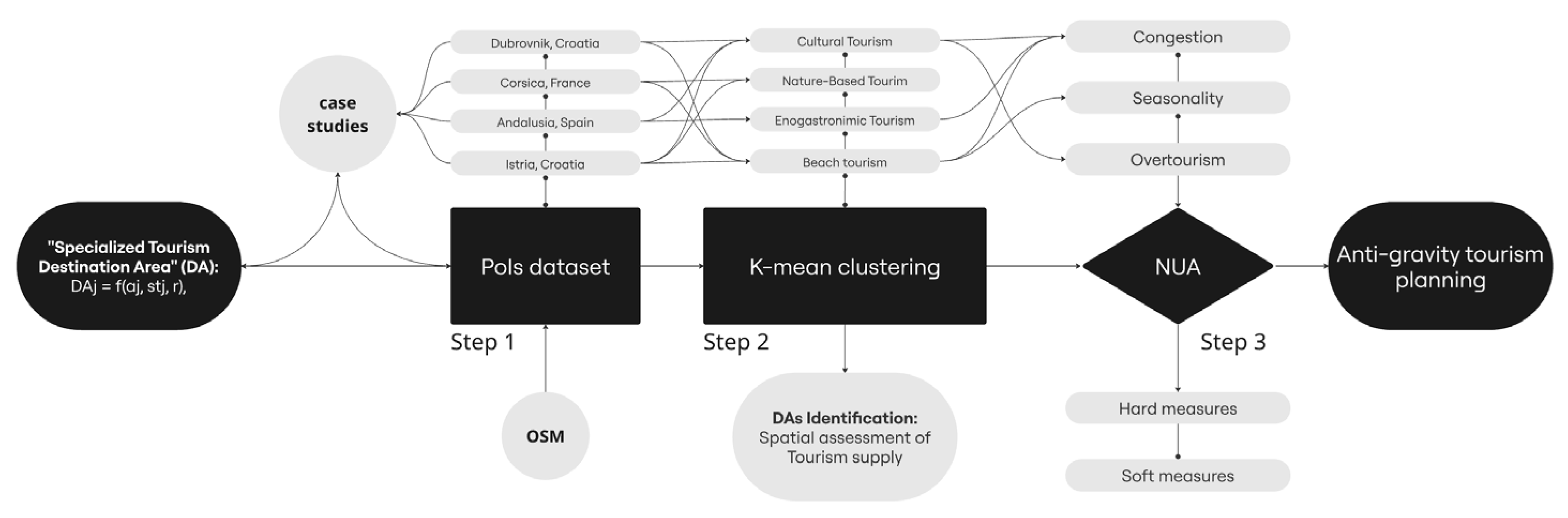

The

Figure 1 describes the methodological steps. In a first step, Points of Interest (PoIs) was selected according to STESY taxonomy and the specific tourism value chains recognized in the case studies area. Data were retrieved mainly from OpenStreetMap and open-source data services available in each case study area at national or local level, with a focus on services and facilities relevant to tourism, while tourist attractors were integrated from national and local sources such as heritage registers, cultural databases, and municipal inventories. To contextualize the individual case studies, complementary statistical information was collected from the national statistical office and local statistical portals.

In a second step, the georeferenced dataset was organized and classified according to the STESY model, which provides a standardized framework to capture the specific value chains of tourism and ensures comparability across territorial contexts. This categorization allowed for a coherent interpretation of the functional role of services and attractors within the tourism system. Subsequently, the identification of Destination Areas (DAs) was carried out through spatial clustering techniques. Through K-mean clustering, local clusters of functionally interrelated PoIs based on Euclidian proximity were identified and validated as Destination Areas, thus reflecting the territorial articulation of tourism supply within each case study. Finally, the identified DAs were interpreted through the lens of the New Urban Agenda, applying a downscaling approach to translate global principles of sustainability into context-specific strategies. The results are reported in terms of local anti-gravitational tourism development strategies, aimed at mitigating excessive tourism pressure and promoting more balanced and sustainable local development trajectories.

Four case studies were selected representing different territories characterized by different tourism specializations: European coastal and island destinations with diverse yet comparable tourism characteristics Dubrovnik (Croatia) and Istria (Croatia), Corsica (France), and Andalusia (Spain). These destinations were selected as representative of different tourism systems where externalities, depending on gravitational effects of tourism flows, are coherent with major concerns remarked in tourism sustainable development debate: Congestion, Seasonality and Overtourism. Additionally, the tourism specializations are important both for the analytical phase of the research and for the design steps. The four case studies allowed to investigate: Nature based tourism, enogastronomic tourism, beach tourism and cultural tourism. This methodological framework allows to assess tourism supply in a spatial dimension that goes beyond administrative boundaries and official statistical unit focusing on local tourism territorial values and local tourism services facilities organization. The DA represents the finest unit of tourism supply in a territorial system. The STESY model provides a conceptual framework designed to examine specialized tourism phenomena, with particular attention to their spatial and territorial dimensions. It operates as a taxonomy that allows the systematic classification and organization of knowledge, thereby supporting the analytical process from the early stage of territorial mapping to the formulation of strategic decision-making tools. The model adopts a hierarchical perspective in which specialized tourism is structured into three analytical scales: the Specialized Tourism Ecosystem, the Specialized Tourism System, and the Specialized Destination Area (DAj). The latter constitutes the fundamental unit for interpreting the territorial organization of tourism supply. A DAj is defined by the functional and spatial configuration of the local tourism system. This implies that a single destination area may extend across several municipalities, while in other contexts multiple destination areas can coexist within the limits of one municipality. The analytical definition of a DAj rests on the interrelation between attractors, services, and reachability, expressed as:

Attractors (aj) comprise the physical points of interest that generate flows, such as UNESCO World Heritage sites, historic settlements, or environmental resources recognized at national and international levels. Services (sj) refer to the facilities that sustain the tourism supply chain, including accommodation and catering establishments, each with specific locational attributes. Reachability (r) concerns the infrastructural and organizational systems that determine accessibility to the destination, such as transport hubs, mobility networks, or parking facilities. A distinctive feature of the STESY model is the introduction of the specialization parameter (j), which identifies the prevailing tourism orientation of a given destination, whether cultural, gastronomic, nature-based, or otherwise. This categorization makes it possible in deep understanding of the relationships among functional sub-regions, providing insights into how different territorial components interact within the broader tourism system.

2.1. Step 1: PoIs Dataset and Case Studies

The first step in the application of the STESY model consists of the systematic collection and classification of territorial data for each selected case study. This phase is crucial for identifying the structural components of the tourism supply system (attractors, services, and reachability), and for assessing their spatial distribution and interrelations within the destination area. The four case studies—Corsica, Andalusia, Istria, and Dubrovnik—were chosen because they represent distinct territorial contexts and tourism specializations, allowing for a comparative analysis across different spatial configurations. The data were obtained through the integration of official statistics, local tourism agency portal, OpenStreetMaps, and were organized according to the taxonomy proposed by the STESY framework. By structuring the information in this way, it is possible to highlight the specific features of each destination while maintaining a consistent analytical approach that facilitates cross-case comparison

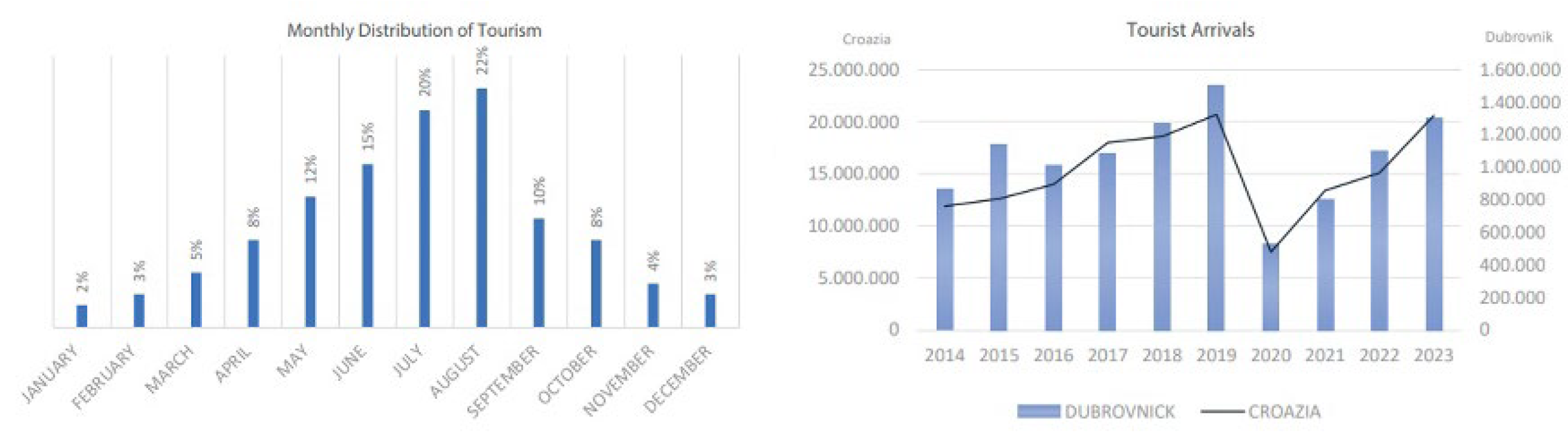

2.1.1. Dubrovnik, Croatia

Dubrovnik is among Croatia’s most visited destinations, showing consistent growth in tourist arrivals until 2019, followed by a sharp decline in 2020 due to COVID-19 travel restrictions. Since 2021, visitor numbers have gradually increased, approaching pre-pandemic levels by 2022–2023, signaling a recovery of international appeal (

Figure 2).

Trends in overnight stays follow a similar pattern, with a strong expansion of hotel and other accommodation bookings before 2020 and a progressive recovery afterward (

Figure 2). Tourism in Dubrovnik is highly seasonal: summer months (June–September) account for the majority of visits, while winter months (November–February) see minimal tourist presence, highlighting the city’s dependence on summer tourism. The analysis of accommodation facilities shows that the majority of type of stay, around 55%, is hotels. Apartments represent the second most common option with 35% of total accommodation availability. Campsites and hostels are smaller share of accommodation typology (7%), while only 3% are alternative forms of lodging. These data suggest that Dubrovnik’s tourism profile is largely oriented toward travelers seeking mid-to-high levels of comfort. When considering the typologies of tourism practiced, cultural tourism emerges as the predominant form, with approximately 40 percent of PoIs over the total amount of attractions. This is closely followed by beach tourism, around 35 percent, which highlights the strong maritime appeal of the city in addition to its cultural heritage. Overall, the city presents a tourism offer that integrates history, culture, and maritime resources. Cultural attractions such as historical sites, museums, monuments, castles, and religious buildings coexist with seaside tourism characterized by beaches and water-based recreational activities including kayaking, snorkeling, jet skiing, and coastal walks (

https://croatia.hr/it-it).

2.1.2. Corsica, France

Tourism is a key economic sector for Corsica, an island renowned for its natural landscapes, beaches, and cultural heritage. Accommodation data show that campsites are more frequented than hotels and other collective facilities, reflecting a strong appeal of outdoor tourism. Passenger transport has steadily increased, with maritime traffic playing a significant role in supporting tourism growth.

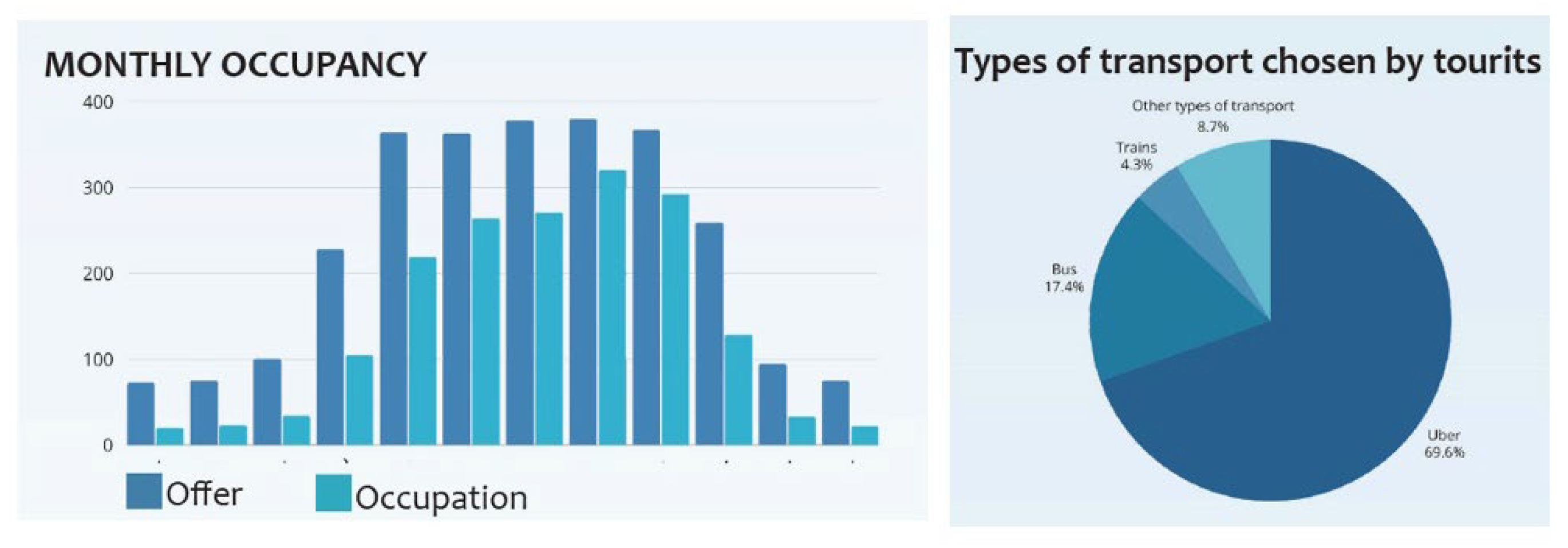

Tourist mobility relies heavily on ride-sharing services (60.6%) and buses (17.4%), with limited use of trains and other public transport, suggesting gaps in the public transport network (

Figure 3). Accommodation demand peaks in summer months (June–August), underlining strong seasonality. The initial survey of the study area reveals that more than half of the identified attractors (54%) correspond to beaches. This confirms the predominance of seaside tourism over other forms of tourism, such as nature-based or inland attractions. The spatial distribution of POIs classified according to the STESY taxonomy highlights a strong concentration along the coastline, especially near beaches, forming a continuous line of tourism resources. In contrast, the inner of the island shows a more fragmented and uneven presence of points of interest, suggesting a weaker integration of inland areas within the overall tourism system.

2.1.3. Andalusia, Spain

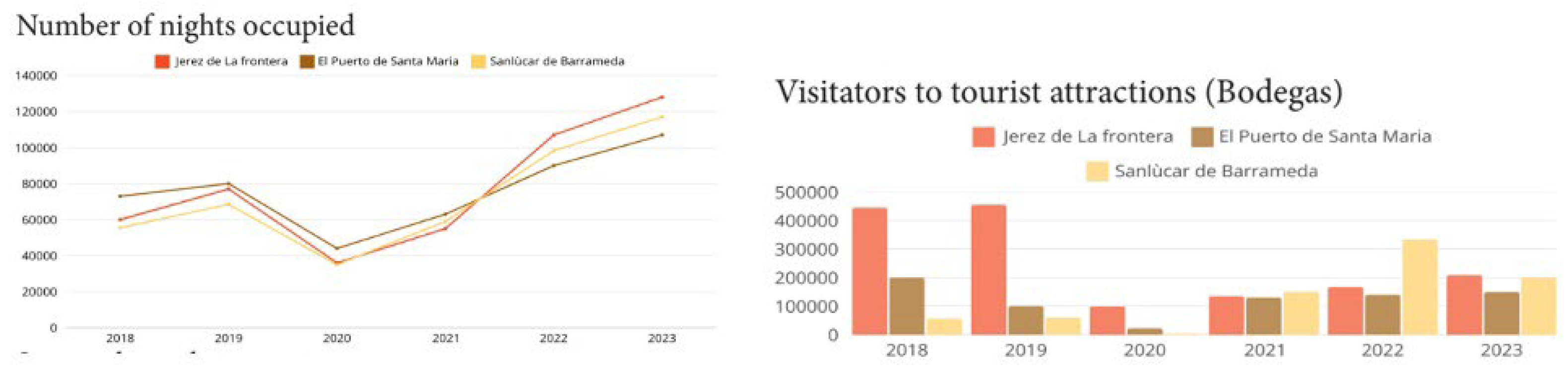

This case study examines the area encompassing cities of Jerez de la Frontera, El Puerto de Santa María, and Sanlúcar de Barrameda, in southern Spain. The study area is internationally recognized for its winemaking tradition, which plays a central role in the local economy and shapes a distinctive form of tourism. Collectively, the three cities account for 0.70% of the national tourism system, within the 3% contribution of the province of Cádiz and the 13% of Andalusia.Passenger flows through Jerez Airport have shown steady growth, reaching approximately 200,000 travelers (

www.turismojerez.com, retrieved 20/03/2025). Nonetheless, air transport does not represent the main access mode, as road transport dominates: around 87% of visitors reach the area by car, confirming the importance of terrestrial mobility for regional connectivity. Accommodation capacity has also expanded in recent years, with Jerez providing nearly 40,000 available beds, which—together with facilities in El Puerto and Sanlúcar—contributes to more than 115,000 recorded overnight stays (

Figure 4). Visitor numbers in Jerez alone exceeded 400,000 in 2018–2019, before declining sharply due to the COVID-19 crisis. Since 2021, demand has shown signs of recovery across the three cities, although the distribution of visitors has shifted. Sanlúcar now emerges as the leading destination, welcoming about 320,000 winery-related tourists in 2022, indicating a partial reconfiguration of flows within the area (

Figure 4). The collection of data points out to a significant prevalence of services, representing 73 percent of the identified POIs. Among these, traditional bars and restaurants account for 79 percent, underlining the central role of eno-gastronomy in the local tourism experience. Cultural and religious heritage also play an important role within the category of attractors. Additionally, 46 percent of the main attractions are associated with wineries, confirming the strategic importance of wine production and enotourism for the region.

2.1.4. Istria, Croatia

Croatia overall has experienced rapid tourist development, ranking among Europe’s top ten destinations in 2024. Coastal areas and islands, particularly the Dalmatian coast and Istrian peninsula, attract most visitors, combining natural and cultural attractions.

Tourism infrastructure and services are concentrated along these main coastal nodes, highlighting the spatial centrality of seaside areas. This spatial distribution highlights the centrality of coastal areas in the organization of tourism-related infrastructure and mobility networks. Based on Eurostat’s statistical data, an analysis of overnight stay trends from 2020 to 2023 reveals a pronounced peak in tourist arrivals between June and August, followed by a significant decline from November to February (

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database). The region’s heritage constitutes a major attractor, including archaeological sites, historic towns, and natural landscapes that are central to its tourism identity. These are complemented by a dense network of services, ranging from accommodation and food establishments to transport facilities and experiential activities. The role of reachability is also crucial, as transport infrastructure determines the accessibility of the main POIs. Institutions such as museums and art galleries, alongside seaside resorts and archaeological areas, emerge as pivotal in shaping both the tourism offer and the preservation of Istria’s cultural and natural identity.

2.2. Step 2: K-mean Cluster Analysis

Using the GEODA software [

32,

33,

34], a cluster analysis was conducted to identify the Destination Areas of the four case study areas. The resulting clusters can be interpreted as gravitational sub-areas, capturing the spatial concentration of tourism activities and the interactions among destinations. These sub-areas highlight localized intensity as well as functional linkages, providing insights into the spatial organization of tourism within each case study.

2.2.1. Dubrovnik, Croatia

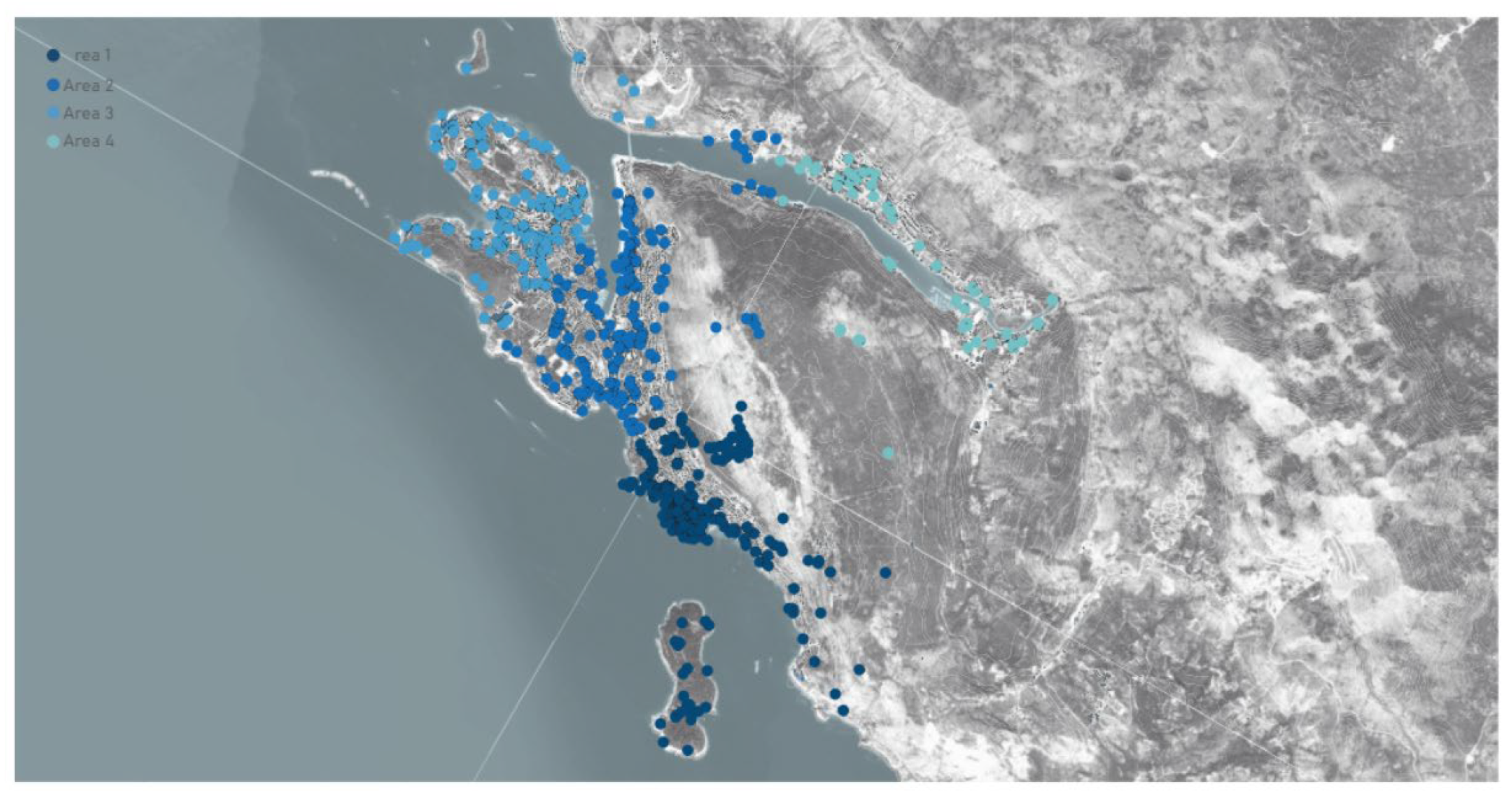

The analysis identified four Destination Areas (DAs) with distinct distributions of services, attractions, and accessibility (

Figure 5). Area 1 DA is the core of Dubrovnik’s tourism, with the highest concentration of services (178) and attractions (91), including panoramic points, memorials, and beaches. Its dense distribution generates significant overcrowding during peak seasons. Area 2 DA offers a more balanced model, with 95 services and 26 attractions, supported by 74 infrastructure points, allowing for a less crowded, practical tourism experience. Area 3 DA combines 76 services and 38 attractions with 41 transport points, emphasizing natural and scenic appeal while maintaining moderate tourist density. Area 4 DA is the least developed, with only 18 services and 7 attractions; although reachability is adequate (26 infrastructure points), low element density limits tourist pressure and appeal. Overall, tourism impacts are closely linked to the density and distribution of services and attractions, with concentrated areas experiencing higher pressure and dispersed areas providing more balanced experiences.

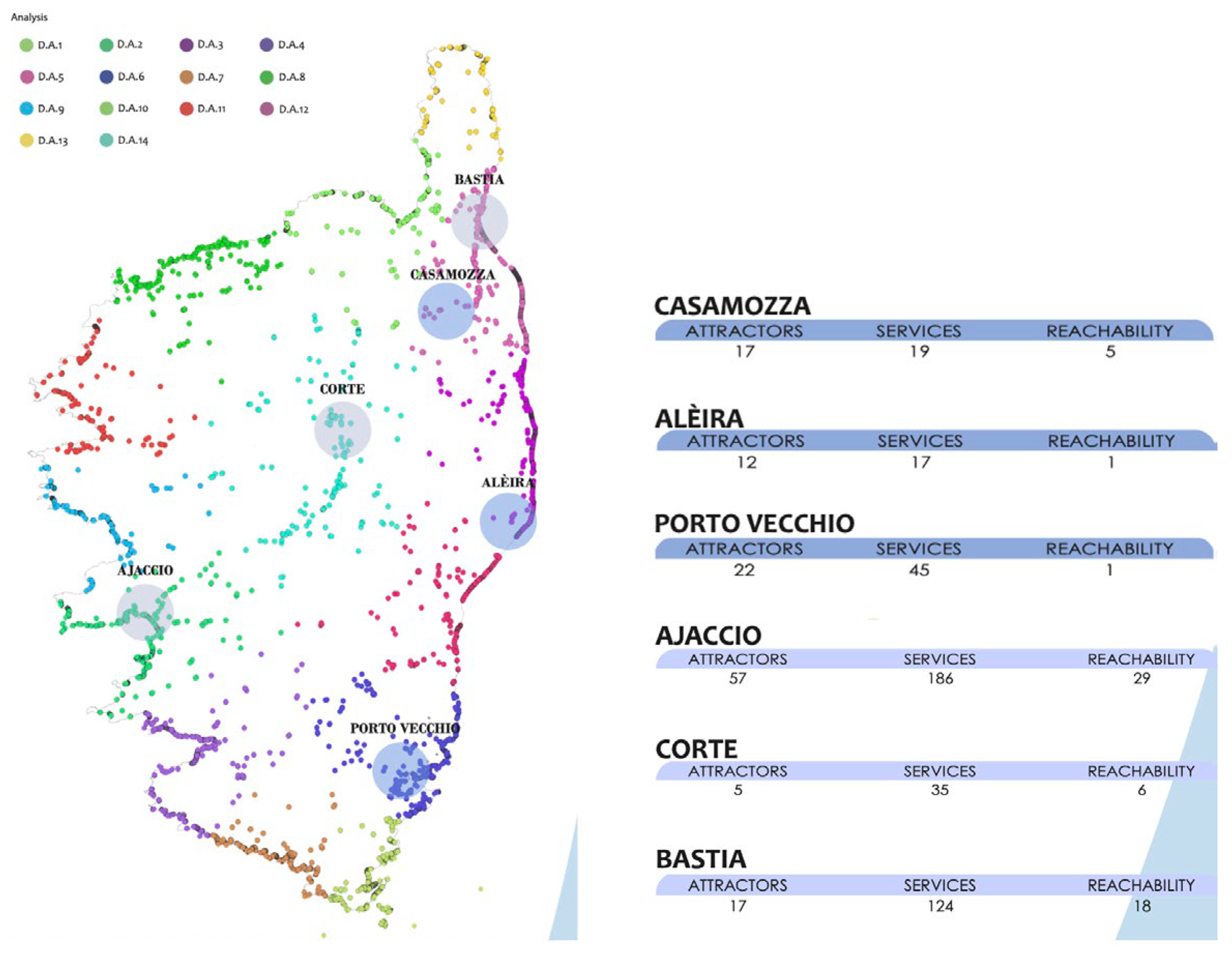

2.2.2. Corsica, France

Among the 14 identified Destination Areas (Fig, 6), a comparison was carried out focusing on structural weaknesses across the components of attractors, services, and reachability. It emerges that the communities of DA Aleira and DA Porto Vecchio exhibit the lowest levels of reachability, despite the cluster’s population size. In contrast, DA Ajaccio stands out for having the highest number of services and reachability points and attractors. In contrast, DA Bastia displays a well-developed structure of services and reachability relative to the number of attractors. Except for the DA of Corte, there is a clear and widespread tendency for the elements to be densely concentrated near the coast.

Figure 6.

Study area with Destination areas identification and evaluation.

Figure 6.

Study area with Destination areas identification and evaluation.

2.2.3. Andalusia, Spain

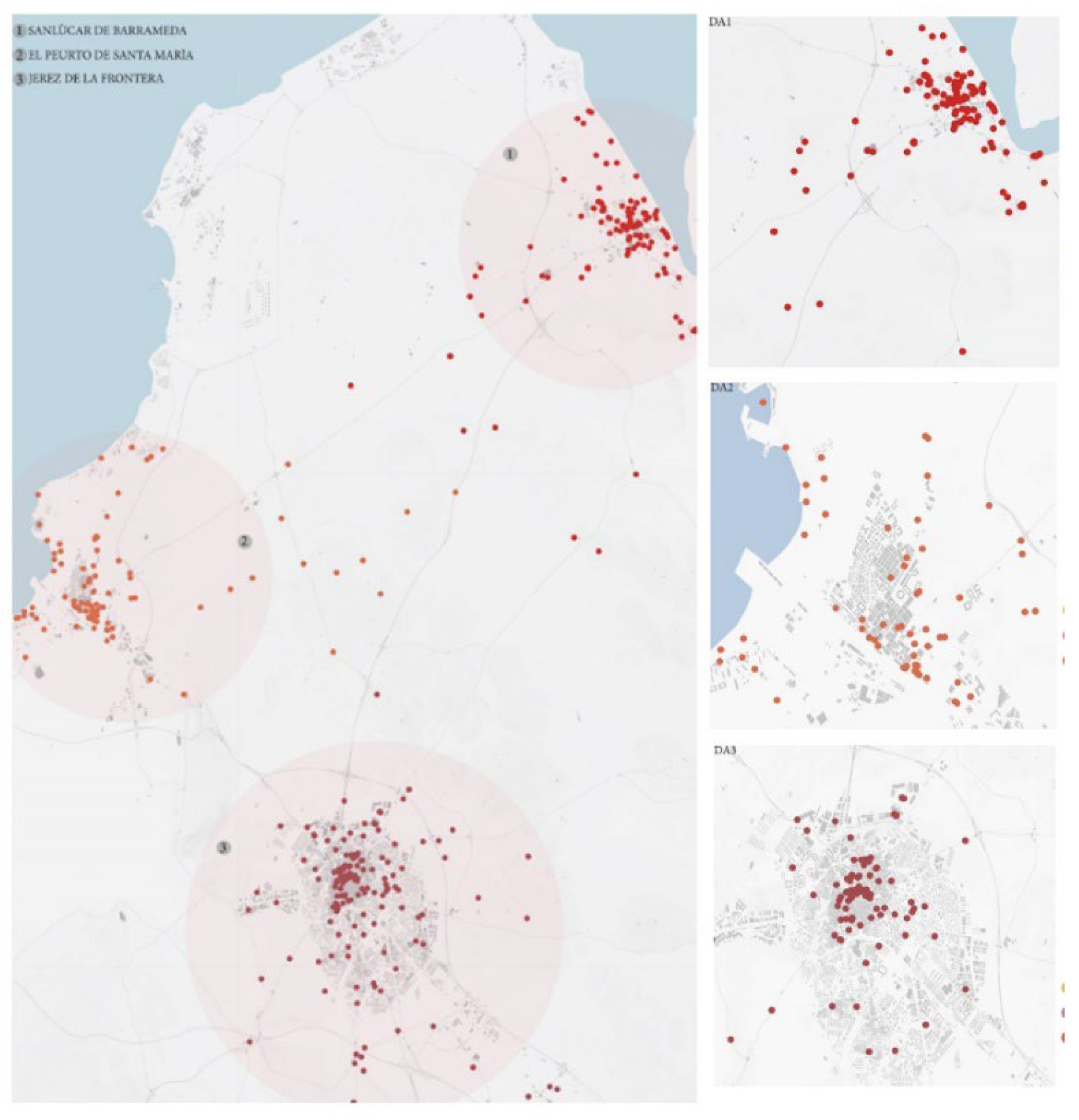

The results (

Figure 7) showed 3 distinct Das: DA in Jerez de la Frontera and DA in El Puerto de Santa María have a higher concentration of services and attractions, along with good accessibility due to key infrastructure such as the airport (for Jerez) and the port and railway network (for El Puerto). In contrast, DA in Sanlúcar de Barrameda displayed significant challenges: Limited Accessibility: There are very few reachbility point; Fewer Attractions: The analysis highlighted a lower presence of cultural and tourist attractions, which could weaken the overall tourism offering.

The figure below describes the spatial distribution of main POIs categories included in the analytical process.

Spatial congestion is concentrated around the main urban centers, gradually dispersing toward the interior of the three DAs.

2.2.4. Istria, Croatia

The analysis of Istria’s tourist clusters highlighted the presence of six main areas of interest, divided into two groups: Areas with a well-established tourist offer, characterized by a high presence of infrastructure and services; Areas with a more limited offer, where the tourism potential is still under development and requires strategic investments. As shown in

Figure 8, the analysis of Croatia’s tourism system has highlighted several issues that hinder the full development of the region’s potential—particularly the strong seasonality of the tourism supply and the limited accessibility of less developed destinations. While Istria is one of the country’s most renowned tourist regions, its visitor flow is heavily concentrated in the summer months, with a sharp decline in demand during the low season. Furthermore, locations that are part of the so-called “weaker” tourism system lack adequate infrastructure and services to attract visitors year-round.

2.3. Step 3: NUA Compliance

The methodological approach applied a downscaling of the New Urban Agenda (NUA), aiming to translate its international guidelines into operational tools at the local territorial scale. In this process, the most relevant principles of the NUA, particularly those concerning sustainable mobility, accessibility, and urban resilience, were identified and reformulated into targeted actions. The methodology had been tested also in a teaching laboratory asking Master Architectural Students to define strategic design in each case study area. The test succesfully demonstrate the effectiveness of the methodological approach easily transferable in technical and learning environment.

2.3.1. Dubrovnik, Croatia

Following an assessment and comparison of the DA, we recognize Area 4 (Canal D’Ombra) as a potential area for development and enhancement that would attract tourists and integrate into the tourism circuit of the other three DAs, balancing the current tourist pressure. The design project has as its main objective the decentralization of part of the tourism from the historic center, favoring a more distributed and sustainable experience. To do this, the focus is on the creation of eco-sustainable accommodation, the increase of services for visitors and the enhancement of the historical and cultural heritage.

The establishment of a pedestrian and cycling path along the river offering new spaces for leisure and improving the connection between the urban center and the natural landscape.

The recovery of historical buildings and traditional houses for the creation of a widespread hotel represents a model of sustainable hospitality that enhances the existing architectural heritage.

The Castles of Memory: The restoration and enhancement of historic castles allows for the creation of thematic tourist itineraries that combine history, culture and immersive experiences, such as re-enactments and artisan workshops.

Ombla Heritage Trail: The engineering and safety of natural trails promoting trekking and hiking activities.

The project follows the principles of the Urban Agenda [

35] to ensure economic competitiveness, job creation, and climate change mitigation. Through synergy between the public and private sectors, Dubrovnik can develop sustainable tourism, enhancing its natural and cultural heritage while preserving residents’ quality of life.

By investing in alternative tourism experiences and sustainable infrastructure, Dubrovnik can reduce pressure on its historic core and create a more balanced, long-term tourism model.

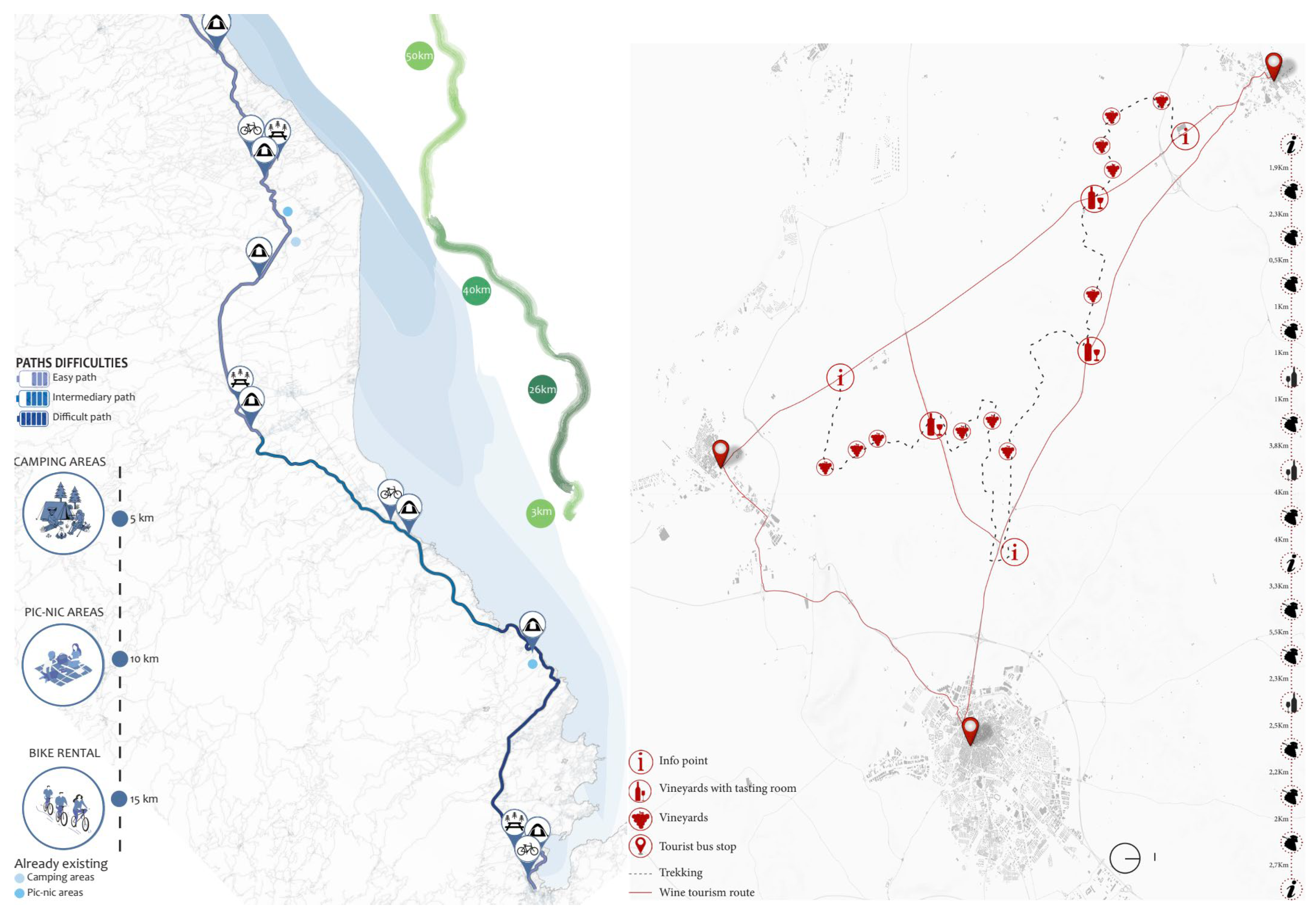

2.3.2. Corsica

The project was conceived to address the connectivity issues along Corsica’s east coast. By transforming the decommissioning of the Bastia-Porto Vecchio railway line into a greenway, the project promotes sustainable mobility, encouraging the use of bicycles and pedestrian paths over traditional motor vehicles.

This initiative aligns with a broader vision of slow tourism, offering an alternative to beach tourism while fostering a deeper connection with the island’s natural and cultural heritage. Inspired by the principles of the New Urban Agenda (NUA), the design focuses on sustainable urban mobility, environmental resilience, and inclusive economic growth. Along the route, travellers will find camping areas, picnic spots, and e-bike rental stations, strategically placed to enhance the overall experience. The greenway (

Figure 10) is designed with different difficulty levels—ranging from flat and accessible sections to more challenging hilly and mountainous terrain—allowing visitors to choose routes based on their preferences and physical abilities. Travel time estimates vary depending on the means of transport: 32-34 hours on foot, 6-7 hours by bike, and 3 hours by car.

Beyond its ecological and mobility benefits, the project is expected to have a significant economic impact, particularly in addressing the seasonality of tourism. Currently, Corsica experiences an influx of visitors during the summer, while winter tourism remains underdeveloped [

36]. By creating an all-season attraction, the design is projected to increase local revenues, particularly benefiting businesses and communities along the route.

2.3.3. Andalusia, Spain

To enhance wine tourism and improve connectivity between DA Jerez de la Frontera, DA El Puerto de Santa María, and DA Sanlúcar de Barrameda, several actions proposals have been developed in line with the objectives of the New Urban Agenda on the basis of the methodological approach oriented to the downscaling of NUA principles [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

One of the main initiatives focuses on improving transportation, with particular attention to Sanlúcar, which currently faces disadvantages due to limited access infrastructure. Strengthening the connections between the three cities would help reduce territorial inequalities and ensure a more efficient and inclusive transport system, aligning with New Urban Agenda [

42] which aims to provide safe, sustainable, and accessible transport for all[

43,

44,

45]. Another initiative is oriented to define a pedestrian route that passes through the region’s vineyards, offering visitors an immersive and direct experience of the territory (

Figure 11). This itinerary would not only promote slow tourism but also contributes to the enhancement of the natural heritage by ensuring accessible and sustainable spaces, encouraging access to inclusive and safe green spaces.

To support this project, the construction of three tasting facilities along the route has been proposed, where visitors can explore local wine varieties and learn about the production processes. This initiative would not only foster economic growth and employment but would also contribute to the protection and promotion of the region’s food and wine heritage, reinforcing the link between culture and sustainable development.

2.3.3. Istria, Croatia

The design aim at transforming Croatia into a more balanced, sustainable, and year-round tourist destination. The design proposal focuses on three strategic objectives (

Figure 12):

De-seasonalizing the tourism offer, encouraging visits beyond the peak summer months and extending demand into autumn and winter through a Winter Festival (November–February), concerts and cultural events

Enhancing accessibility and connectivity in less developed areas, particularly within the Istrian region by upgrading the historic Parenzana cycling route (123 km from Trieste to Poreč).

Promoting sustainable tourism models, including soft mobility, experiential travel, and innovative forms of accommodation: Glamping units in natural settings will cater to high-end cycling tourists, offering privacy, wellness areas, and bike services

3. Discussions

The analytical process allowed to identify tourism externalities in the four case study areas. The selected cases, far to be emblematic of a specific tourism characteristic, are mainly representative of local conditions that a decision makers could identify practicing a planning process in the specific sector of tourism development. In this section of the paper, we intend to refer to the main findings in a comparative way, in order to defend the thesis based on the concept of anti-gravity approach in tourism decision making.

The four cases produced four anti-gravity sustainable strategic designs characterized by a robust reference to NUA principles. Some common issues emerged: seasonality, overtourism and congestion. In order to overcome such criticalities, the NUA strategies pointed out a common generalized objective: to link fragmented areas shifting tourism from mayor poles to minor ones.

A recurring design theme within anti-gravitational strategies is the implementation of linear infrastructures that reconnect fragmented areas in local case studies marked by varying degrees of tourism-related development. These infrastructural interventions more than material ones, act as mediating elements between over-infrastructured and underdeveloped zones, facilitating both physical and functional integration. From the point of view of the conceptualization discussed in this work we shifted from gravity interpretation models towards anti-gravity ones.

Focusing on the strategic anti-gravity tourism design it is relevant to point out characterizing actions:

The wine-tourism network in Andalusia (Spain) exemplifies this shift by strengthening transport connections between Jerez de la Frontera, El Puerto de Santa María, and Sanlúcar de Barrameda, while also enhancing slow mobility through vineyard routes and tasting facilities. This dual approach reduces territorial inequalities and reinforces the cultural value of the region’s landscape.

In Dubrovnik (Croatia), the decentralization project in the DA of Canal D’Ombra addresses the problem of congestion in the Old Town by promoting eco-sustainable accommodation, reusing historic buildings, and creating thematic cultural itineraries. The aim is to redistribute visitor flows and integrate peripheral areas into the main tourism circuit.

The Corsican greenway project converts the disused Bastia–Porto Vecchio railway into a sustainable mobility corridor, introducing cycling and pedestrian paths with rest areas and e-bike rentals. By diversifying the tourism offer beyond the summer peak and beach monoculture, the project creates an all-season attraction that supports local economies while encouraging slow tourism.

Finally, in Istria (Croatia), the upgrading of the Parenzana cycling route and the creation of innovative accommodation models such as glamping units contribute to de-seasonalization, promoting cultural events in the low season and offering high-quality services for cycling tourists. These actions strengthen regional connectivity and position Istria as a year-round tourism destination.

Figure 13.

The four anti-gravity strategies.

Figure 13.

The four anti-gravity strategies.

By bridging spatial discontinuities and re-establishing connectivity, such designs aim to promote a more balanced and sustainable territorial tourism value chain configuration, often challenging traditional hierarchies of concentration in major poles.

In each case study, a territorial framework is defined with the aim of mitigating the externalities associated with more traditional approaches to tourism management. These planning frameworks are based on the strategic localization of new functions and services in the edges and peripheral areas of each Destination Area. This approach challenges the conventional tourism development model, which tends to concentrate infrastructure and visitor flows within the historic or central cores, thereby intensifying issues such as overcrowding, spatial inequality, and the degradation of local quality of life.

From the perspective of urban and regional planning literature, this shift aligns with broader theoretical frameworks that advocate for polycentric development and the redistribution of urban functions (ref. [

46,

47]). The concept of anti-gravity is comparable with the decentralization of tourism-related activities, the proposed territorial frameworks support a more balanced spatial organization, reduce pressure on saturated tourism cores, and enhance the resilience and interconnections of peripheral zones.

Moreover, the proposed strategies resonate with the principles of ‘territorial justice’ and ‘just sustainability’, which emphasize the equitable distribution of both environmental burdens and socio-economic benefits across urban and regional spaces. The activation of inner areas as a network of minor tourist destination areas with specific supply and attraction potential due to local specializations, can foster more sustainable and diversified local economies, while also promoting spatial cohesion.

4. Conclusions

This paper investigated the spatial dimensions of tourism through the lens of territorial planning and urban studies, proposing the original concept of anti-gravity tourism as both a theoretical framework and a strategic planning approach. Building upon empirical evidence from four diverse case studies, the research has demonstrated how excessive concentration of tourism flows—what we refer to as “tourism gravitation”—produces externalities in the long-term sustainability of a place. In contrast, anti-gravity strategies aim to redistribute flows, promote peripheral areas, and rebalance territorial configurations in line with the principles of the New Urban Agenda and broader urban planning theories of polycentrism, territorial justice, and just sustainability.

The comparative analysis revealed recurring issues across the selected tourism destinations: seasonality, overtourism, and congestion. Despite their contextual differences, all four case studies converged around a common design logic: activating linear and connective infrastructures that bridge spatial discontinuities and redistribute tourism-related functions from saturated cores to underutilized peripheries. These interventions, both physical and functional, support the reconfiguration of tourism value chains and promote balanced territorial development, challenging the dominant logic of tourism centralization.

From a planning theory perspective, the findings reinforce the relevance of polycentric urban models. The anti-gravity approach aligns with recent efforts in urban regeneration (e.g., Porto, Italian “Borghi” programs) and represents a step toward more proactive, design-oriented approaches in spatial tourism planning.

In terms of results, the STESY model enabled a data-driven identification of Destination Areas (DAs) and provided a spatial typology for evaluating the distribution of tourism-related supply and services. The application of the model also allowed the formulation of strategic design proposals tailored to each context, highlighting the operational applicability of the anti-gravity concept aimed at mitigating tourism externalities.

In the discussion, we positioned anti-gravity tourism as a novel conceptual and operational tool capable of addressing some of the most pressing challenges in tourism planning today. The paper contributes to reframing tourism not as an isolated sector, but as a key driver of the spatial transformation of territories. Such an approach also reflects the evolution of planning paradigms toward more integrative and systemic models, where tourism is not treated as an isolated sector but embedded within broader strategies for urban regeneration, social inclusion, and ecological transition. Therefore, the design of these territorial frameworks represents not only a response to tourism-related challenges, but also a testing ground for contemporary urban policy principles that aim to reconfigure the relationship between center and periphery.

Limitations of the approach is in not considering the temporal evolution of the tourism phenomenon, both in terms of demand and in the configuration of the supply system. Neglecting the temporal dimension means overlooking how tourism demand has diversified and fluctuated over time, responding to fast changing socio-economic, technological, and cultural conditions.

Future developments of the anti-gravity tourism framework open several promising topics for future research and policy experimentation:

It invites further testing across different geographical and governance contexts, to assess scalability and flexibility.

It offers a lens for integrating tourism planning into broader regional development policies also assessing effects of post pandemic recovery.

It encourages to deep tourism studies in a spatial planning perspective.

Ultimately, this paper advocates for a paradigm shift in the governance of tourism: moving from passive management of visitor flows toward spatially grounded, sustainability-oriented, and design-based planning approaches. The anti-gravity model represents not only a conceptual innovation but also a practical methodology for promoting tourism as key territorial development driver.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G. and F.S.; methodology, R.G. and F.S.; formal analysis, R.G.; resources, R.G.; data curation, R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G. and F.S.; writing—review and editing, R.G. and F.S.; visualization, R.G.; supervision, F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The elaborations discussed in the paper was based exclusively on open source spatial and statistical data.

References

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Travel & Tourism Economic Impact Research: Global Trends 2025; 2025;

- Seraj, M.; Ike, O.C.; Ozdeser, H. The Contribution of Tourism on GDP Growth and Sustainable Tourism Development in Africa. Future Business Journal 2025, 11, 115. [CrossRef]

- Portella-Carbó, F.; Pérez-Montiel, J.; Ozcelebi, O. Tourism-Led Economic Growth across the Business Cycle: Evidence from Europe (1995–2021). Econ Anal Policy 2023, 78, 1241–1253. [CrossRef]

- Casado-Aranda, L.A.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Bastidas-Manzano, A.B. Tourism Research after the COVID-19 Outbreak: Insights for More Sustainable, Local and Smart Cities. Sustain Cities Soc 2021, 73. [CrossRef]

- Duro, J.A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Turrion-Prats, J.; Fernández-Fernández, M. Covid-19 and Tourism Vulnerability. Tour Manag Perspect 2021, 38, 100819. [CrossRef]

- Haywood, K.M. A Post COVID-19 Future-Tourism Re-Imagined and Re-Enabled. Tourism Geographies 2020, 22, 599–609.

- Trono, A.; Schmude, J.; Duda, T. Introduction: The Future of Tourism After COVID-19. In Tourism Recovery from COVID-19; Managing Cultural Tourism: A Sustainability Approach; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2022; Vol. Volume 2, pp. 3–13 ISBN 978-981-12-6023-0.

- Metaxas, T.; Gavriilidis, G. Marketing Policies in Public Museums of Greece: Empirical Evidence and Implications for Policy. Urban Science 2025, 9, 351. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Rethinking Tourism-Driven Urban Transformation and Social Tourism Impact: A Scenario from a CEE City. Cities 2023, 134. [CrossRef]

- Mason, P. Tourism Impacts, Planning and Management; Routledge, 2020; ISBN 0429273541.

- Rossello-Geli, J. Tourism-Related Gentrification: The Case of Sóller (Mallorca). Urban Science 2025, 9. [CrossRef]

- Dorta-Preen, J.M.; Santana-Talavera, A. Shaping Places Together: The Role of Social Media Influencers in the Digital Co-Creation of Destination Image. Urban Science 2025, 9. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable Tourism: Research and Reality. Ann Tour Res 2012, 39, 528–546. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Ram, Y. Tourism, Landscapes and Cultural Ecosystem Services: A New Research Tool. Tourism Recreation Research 2017, 42, 113–119. [CrossRef]

- Raevskikh, E. Anticipating the “Bilbao Effect”: Transformations of the City of Arles before the Opening of the Luma Foundation. Cities 2018, 83, 92–107. [CrossRef]

- Brandano, M.G.; Crociata, A. Cohesion Policy, Tourism and Culture in Italy: A Regional Policy Evaluation. Reg Stud 2022, 0, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Rebollo, J.F.V.; Baidal, J.A.I. Measuring Sustainability in a Mass Tourist Destination: Pressures, Perceptions and Policy Responses in Torrevieja, Spain. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2003, 11, 181–203. [CrossRef]

- Herman, G.V.; Bucur, L.; Filimon, C.A.; Herman, M.L.; Nistor, S.; Tofan, G.-B.; Stupariu, M.; Bacter, R.V.; Caciora, T. Exploring the Relationships Between Bicycle Paths and Urban Services in Oradea, Romania. Urban Science 2025, 9, 373. [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. The Phenomena of Overtourism: A Review. International Journal of Tourism Cities 2019, 5, 519–528. [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, E.M. Measuring Overtourism : A Necessary Tool for Landscape Planning. 2021.

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M. Reframing Urban Overtourism through the Smart-City Lens. Cities 2020, 102. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.-M.; Borrajo-Millán, F.; Yi, L. Are Social Media Data Pushing Overtourism? The Case of Barcelona and Chinese Tourists. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3356.

- Duro, J.A.; Turrión-Prats, J. Tourism Seasonality Worldwide. Tour Manag Perspect 2019, 31, 38–53. [CrossRef]

- Cannas, R. An Overview of Tourism Seasonality: Key Concepts and Policies. Almatourism—Journal of Tourism, Culture and Territorial Development 2012, 3, 40–58.

- Stojčić, N.; Mikulić, J.; Vizek, M. High Season, Low Growth: The Impact of Tourism Seasonality and Vulnerability to Tourism on the Emergence of High-Growth Firms. Tour Manag 2022, 89, 104455. [CrossRef]

- Bei, G.; Celata, F. Challenges and Effects of Short-Term Rentals Regulation: A Counterfactual Assessment of European Cities. Ann Tour Res 2023, 101. [CrossRef]

- Huan Koo, J. Anti-Gravity;

- Nieto, M.M.; Goldman, T. The Arguments against “Antigravity” and the Gravitational Acceleration of Antimatter. Phys Rep 1991, 205, 221–281. [CrossRef]

- Nieto, M.M.; Goldman, T. The Arguments against “Antigravity” and the Gravitational Acceleration of Antimatter. Phys Rep 1991, 205, 221–281. [CrossRef]

- UNhabitat The New Urban Agenda; 2016; ISBN 9789211328691.

- Gatto, R.V.; Corrado, S.; Scorza, F. A Taxonomy of Specialized Tourism Ecosystems (STESY): Toward New Geographies for Sustainable Territorial Planning. International Journal of E-Planning Research 2025.

- Anselin, L.; Syabri, I.; Kho, Y. GeoDa: An Introduction to Spatial Data Analysis. Geogr Anal 2006, 38, 5–22. [CrossRef]

- Anselin Luc and Syabri, I. and K.Y. GeoDa: An Introduction to Spatial Data Analysis. In Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis: Software Tools, Methods and Applications; Fischer Manfred M. and Getis, A., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 73–89 ISBN 978-3-642-03647-7.

- Anselin, L.; Li, X.; Koschinsky, J. GeoDa, From the Desktop to an Ecosystem for Exploring Spatial Data. Geogr Anal 2022, 54, 439–466. [CrossRef]

- UNhabitat The New Urban Agenda; 2016; ISBN 9789211328691.

- Huda, S.S.M.S. Potential of Neighborhood Tourism in New Normal: A Research Agenda. Sustainable Communities 2024, 1, 2371578. [CrossRef]

- Santopietro, L.; Solimene, S.; Lucchese, M.; Di Carlo, F.; Scorza, F. An Economic Appraisal of the SE(C)AP Public Interventions towards the EU 2050 Target: The Case Study of Basilicata Region. Cities 2024, 149. [CrossRef]

- Scorza, F.; Pilogallo, A.; Las Casas, G. Investigating Tourism Attractiveness in Inland Areas: Ecosystem Services, Open Data and Smart Specializations. In Proceedings of the New Metropolitan Perspectives; Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Bevilacqua, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; Vol. 100, pp. 30–38.

- Scorza, F.; Fortunato, G. Active Mobility-Oriented Urban Development: A Morpho-Syntactic Scenario for a Mid-Sized Town. European Planning Studies 2022, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Scorza, F.; Fortunato, G. Cyclable Cities: Building Feasible Scenario through Urban Space Morphology Assessment. J Urban Plan Dev 2021, 147, 05021039. [CrossRef]

- Santopietro, L.; Scorza, F. Voluntary Planning and City Networks: A Systematic Bibliometric Review Addressing Current Issues for Sustainable and Climate-Responsive Planning. Sustainability 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Scorza, F.; Casas, G. Las; Murgante, B.; Las Casas, G.B.; Scorza, F.; Murgante, B.; Casas, G. Las; Murgante, B. Overcoming Interoperability Weaknesses in E-Government Processes: Organizing and Sharing Knowledge in Regional Development Programs Using Ontologies. In Organizational, Business, and Technological Aspects of the Knowledge Society; Springer, 2010; Vol. 112, pp. 243–253 ISBN 3642163238.

- Fortunato, G.; Scorza, F.; Murgante, B. Cyclable City: A Territorial Assessment Procedure for Disruptive Policy-Making on Urban Mobility. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2019; Misra, S., Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Stankova, E., Korkhov, V., Torre, C., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Tarantino, E., Eds.; Springer, Cham, 2019; pp. 291–307.

- Scorza, F.; Fortunato, G.; Carbone, R.; Murgante, B.; Pontrandolfi, P. Increasing Urban Walkability through Citizens’ Participation Processes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5835. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, R.; Fortunato, G.; Pace, G.; Pastore, E.; Pietragalla, L.; Postiglione, L.; Scorza, F. Using Open Data and Open Tools in Defining Strategies for the Enhancement of Basilicata Region. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer Verlag, 2018; Vol. 10964, pp. 725–733.

- Hall, P.; Pain, K. The Polycentric Metropolis; Routledge.; Routledge, 2012; ISBN 9781136547690.

- Meijers, E. Measuring Polycentricity and Its Promises. European Planning Studies 2008, 16, 1313–1323. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).