1. Introduction

Pulmonary emphysema, a major component of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), involves irreversible destruction of alveolar walls and progressive airspace enlargement. The disease is driven by a complex interplay of inflammatory, enzymatic, and mechanical factors that disrupt the structural integrity of the lung parenchyma. Increased mechanical stress can cause extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, particularly when accompanied by an imbalance between protease and antiprotease activity (1, 2). Enhanced activity of matrix-degrading enzymes, such as neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), adversely affects ECM structural integrity, resulting in alveolar wall distention and rupture, reduced surface area for gas exchange, and compromised mechanical properties of the lung (3, 4).

This process is exacerbated by lung mechanical stress arising from transpulmonary pressure during breathing, coughing, airway obstruction, and hyperinflation of alveoli due to air trapping (5, 6). A complex network of elastic fibers in alveolar walls normally absorbs and redistributes these forces. However, the degradation of elastin, the distensible elastin component of these fibers, disrupts this balance and leads to focal concentration of stress and tissue rupture (7). The resulting micro-injuries in alveolar walls induce an inflammatory response accompanied by ECM degradation. Computational models of pulmonary emphysema have shown that stress concentrations are highest at alveolar junctions, making these regions particularly susceptible to damage (8).

The interplay between enzymatic degradation and mechanical stress accelerates the breakdown of elastin, creating a vicious cycle of tissue destruction (9,10). This damage may involve initial increases in elastin crosslinking that enhance the structural stability of elastic fibers. However, once alveolar wall diameter exceeds a threshold value, the balance between elastic fiber injury and repair undergoes a phase transition involving rapid elastin breakdown and irreversible tissue damage (11). The subsequent acceleration of airspace enlargement emphasizes the importance of early detection of alveolar wall injury that facilitates timely therapeutic intervention.

The nonlinear progression of disease may be modeled using percolation theory, where fluid movement through a network of interconnected channels represents the progression of chemical and physical phenomena (12). Regarding the lung, the percolation of mechanical forces through the elastic fiber network represents an analogous process, in which the fragmentation of elastic fibers resembles the random disconnection of percolation bonds (

Figure 1). A phase transition occurs when a critical threshold is reached, involving a widespread loss of connectivity that results in uneven transmission of mechanical forces and the emergence of clinically apparent disease (13). This transition may be manifest by changes in lung compliance and gas exchange.

The fragmentation and unraveling of elastic fibers that accompany the phase transition is characterized by a biphasic process involving initial increases in elastic fiber crosslinking, followed by an accelerating breakdown of these fibers and an exponential increase in the release of these crosslinks from disintegrating elastin peptides (11). This phase transition remains poorly understood due to the difficulty correlating biochemical changes in elastin with morphometric measurements of alveolar wall distention. In the current paper, we use previously published mass spectrometric measurements of elastin crosslinks in normal and emphysematous human postmortem lungs to construct a proposed mechanism for a phase transition based on changes in elastic fiber mechanical properties.

2. Experimental Findings

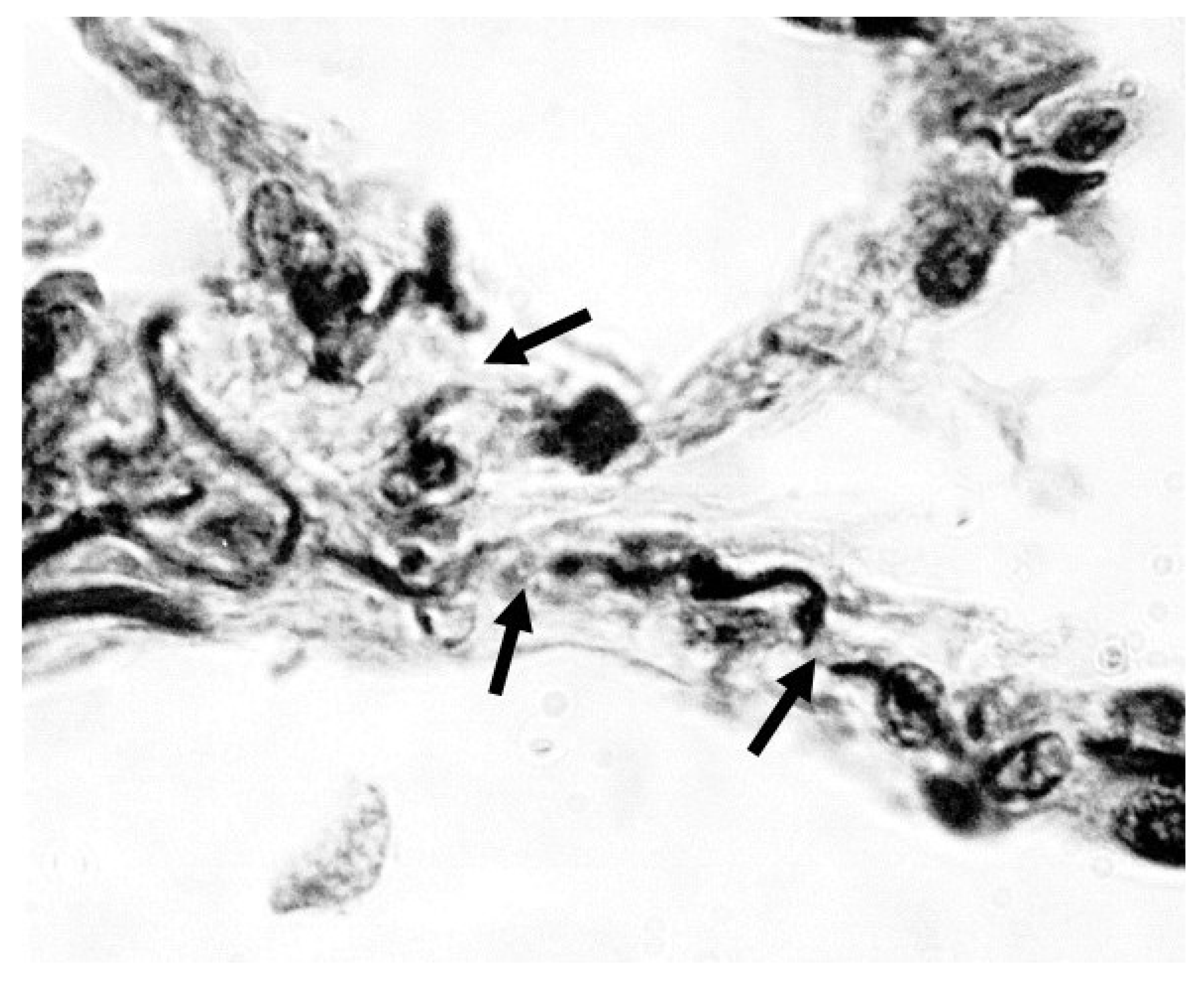

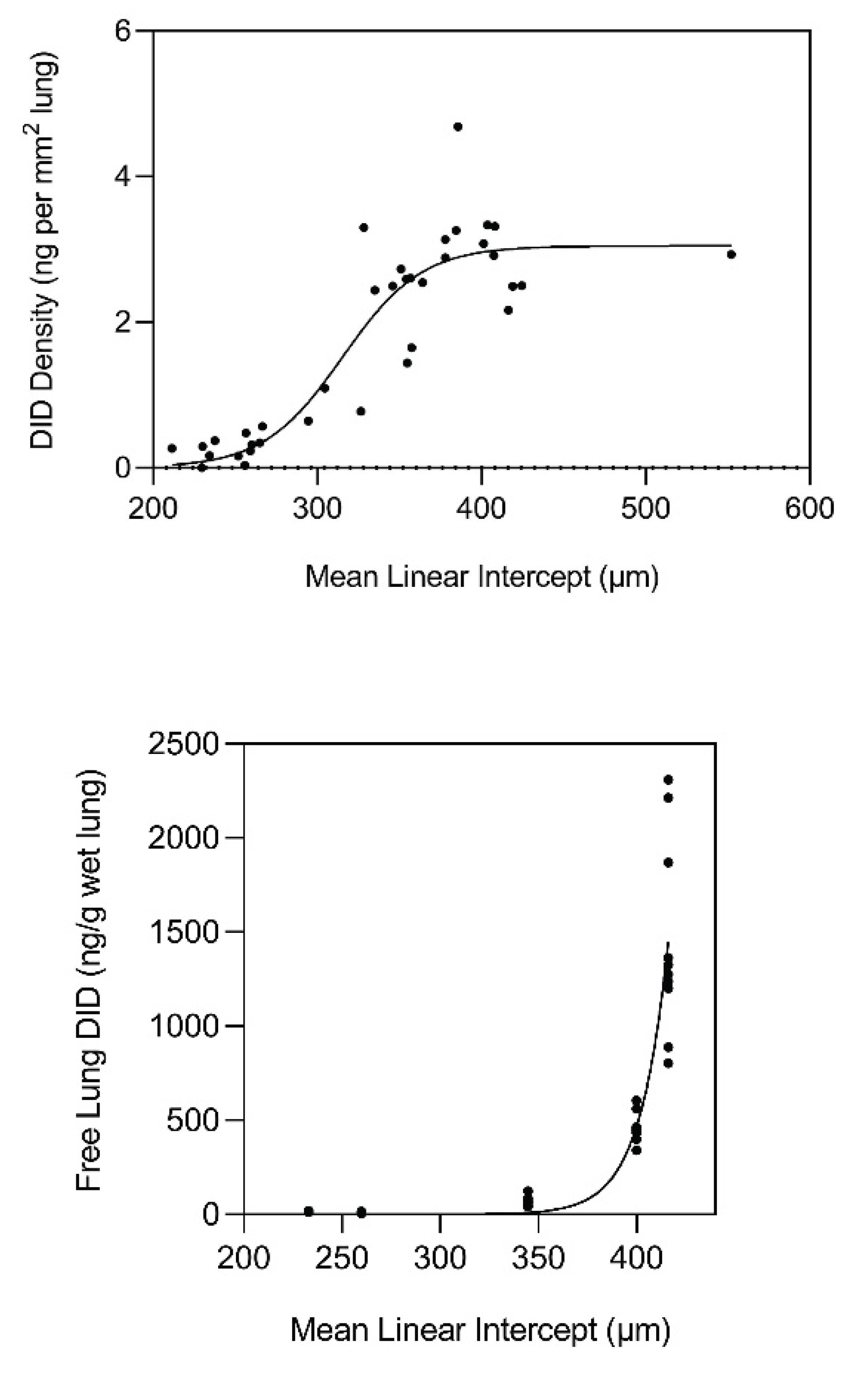

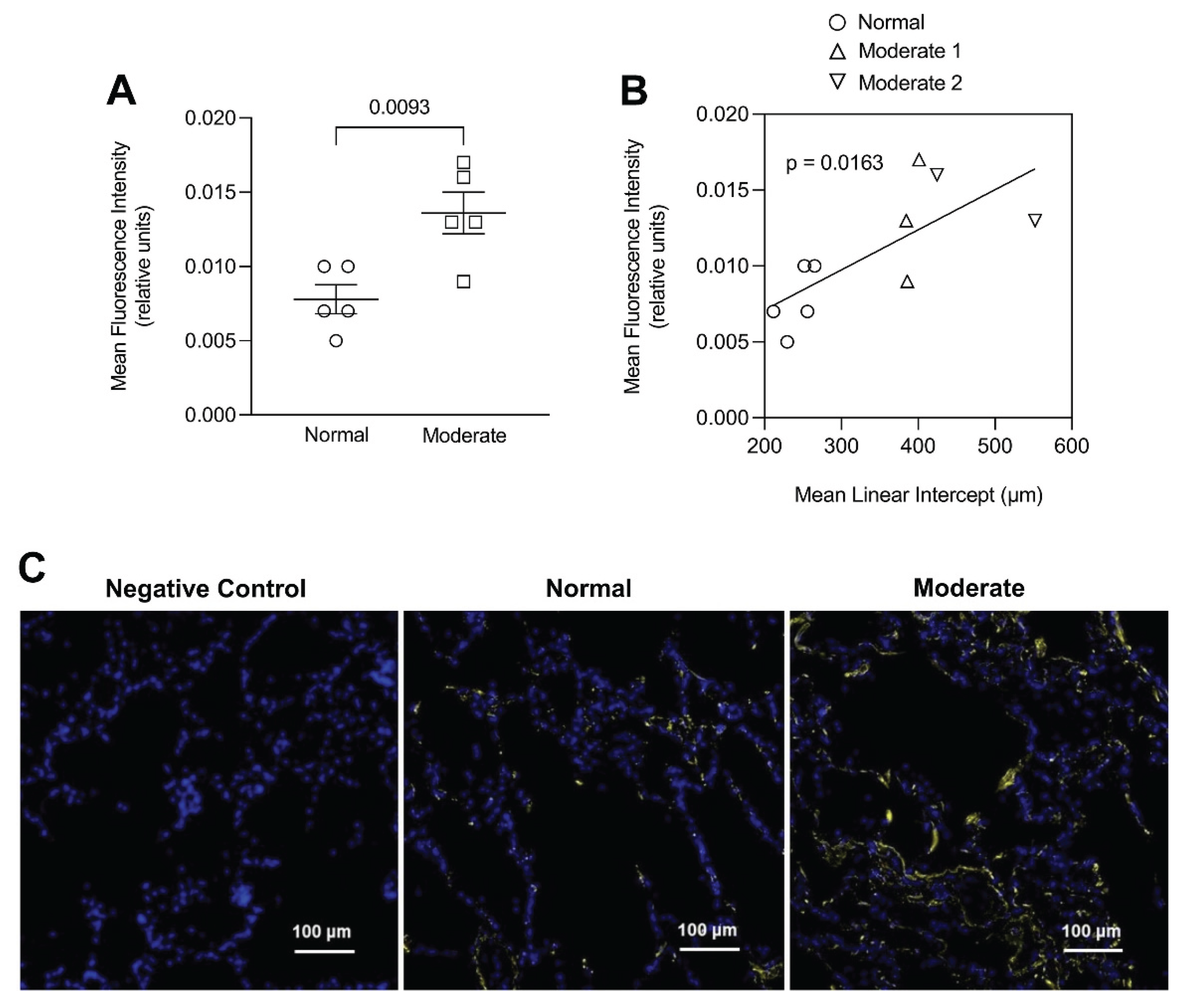

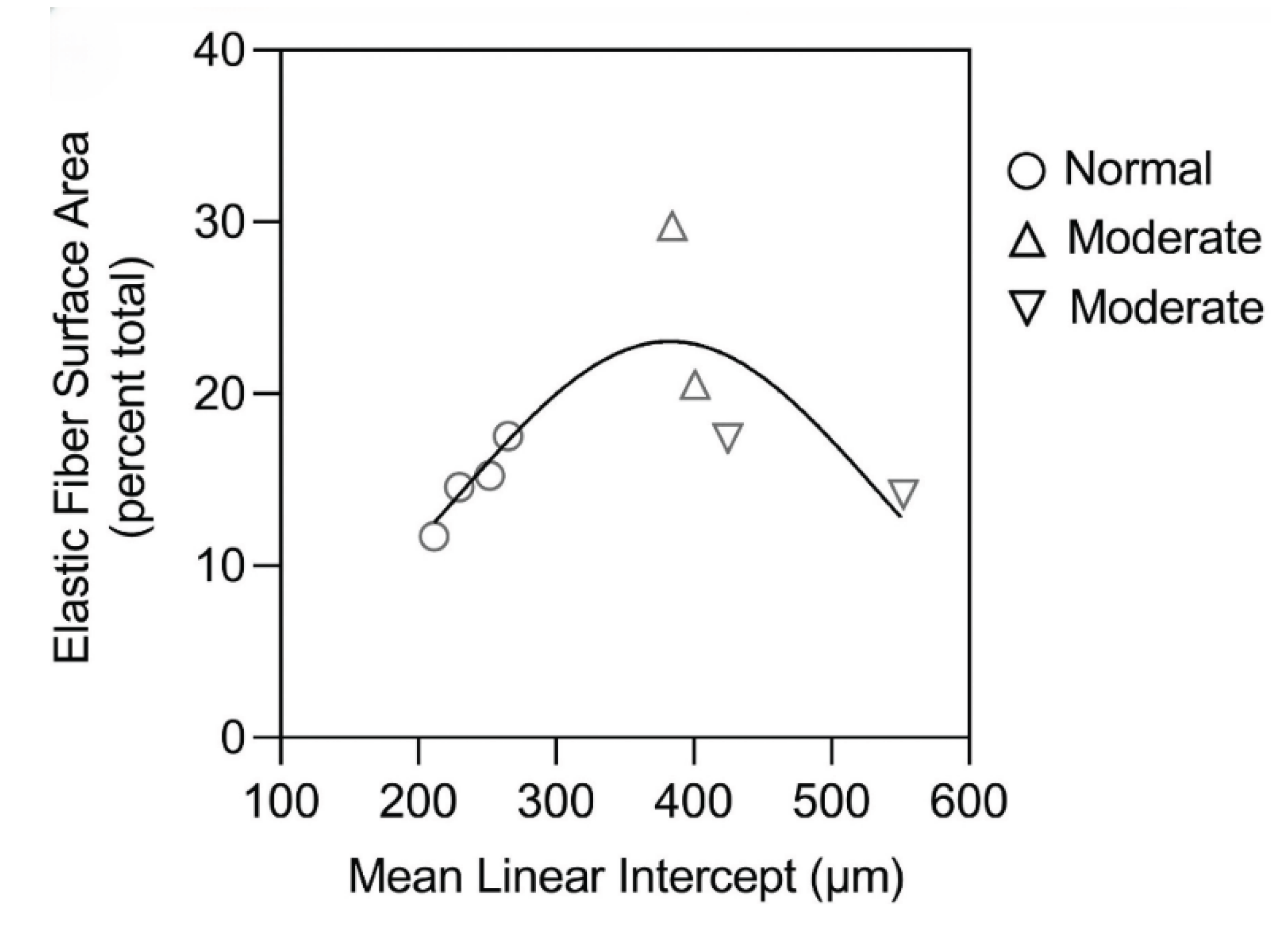

This laboratory performed measurements of peptide-free DID in the lungs of hamsters with pulmonary emphysema induced by treatment with both cigarette smoke and lipopolysaccharide (14). The results indicated a significant correlation between the level of free lung DID and alveolar diameter, supporting the role of elastin crosslinks as a biomarker for airspace enlargement. This study was followed by measurements of free lung DID in both normal and emphysematous postmortem human lungs, which showed that elastin breakdown was greatly accelerated when the mean airspace diameter exceeded 400 μm (

Figure 2). The density of DID in lung tissue sections also increased markedly beyond 300 μm and leveled off at 400 μm (

Figure 2).

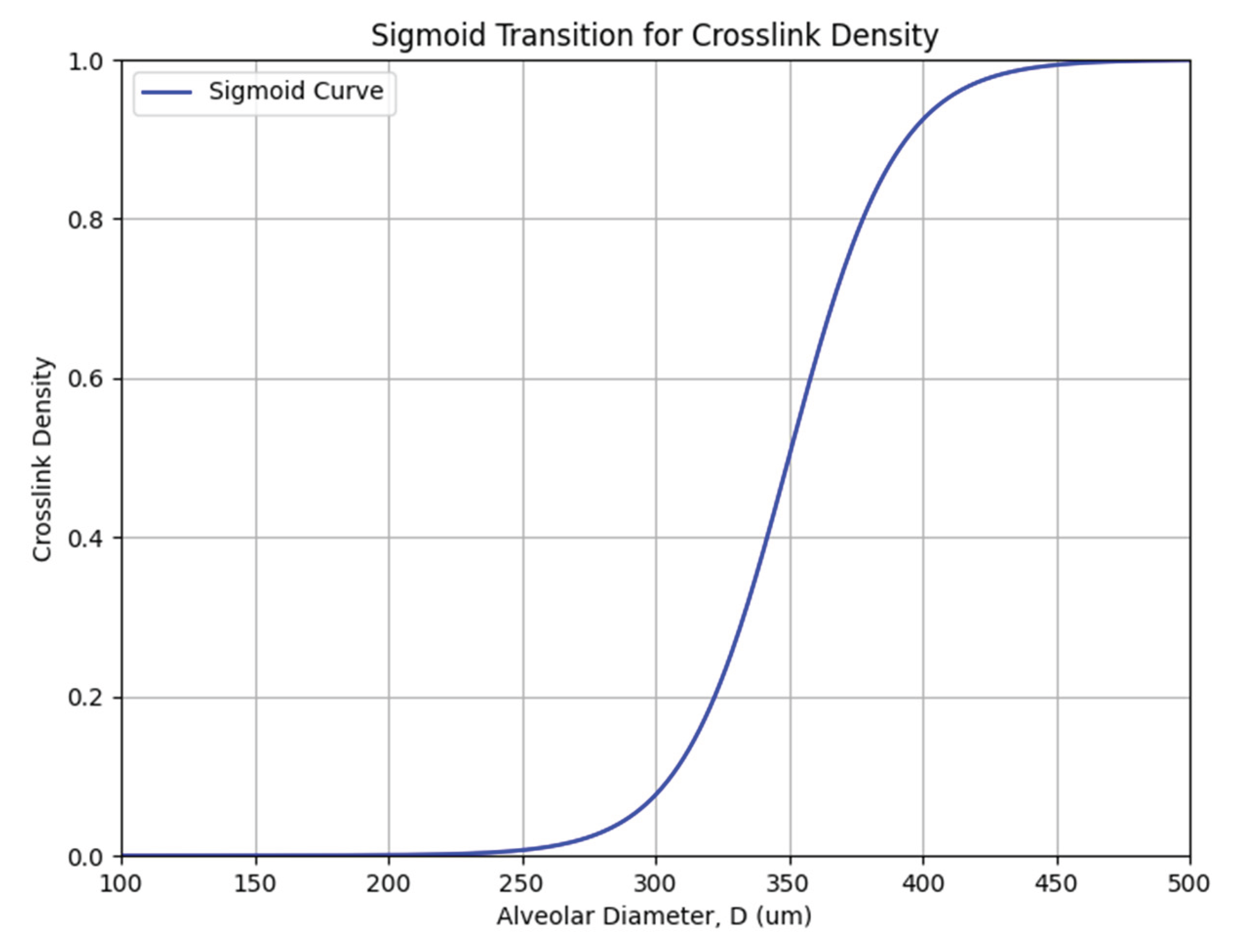

The effect of alveolar wall distention on crosslinking density may be modeled as a sigmoid curve, where DID density (ρx) undergoes an exponential increase (expressed as a value between 0 and 1) when alveolar diameter (D) reaches a critical value (Dc) of 300 µm, based on the experimental findings (

Figure 3) (11):

Here, e represents Euler’s number (~2.718), a fundamental constant used in exponential functions that describe continuous growth or decay, and k determines the rate of increase in crosslink density.

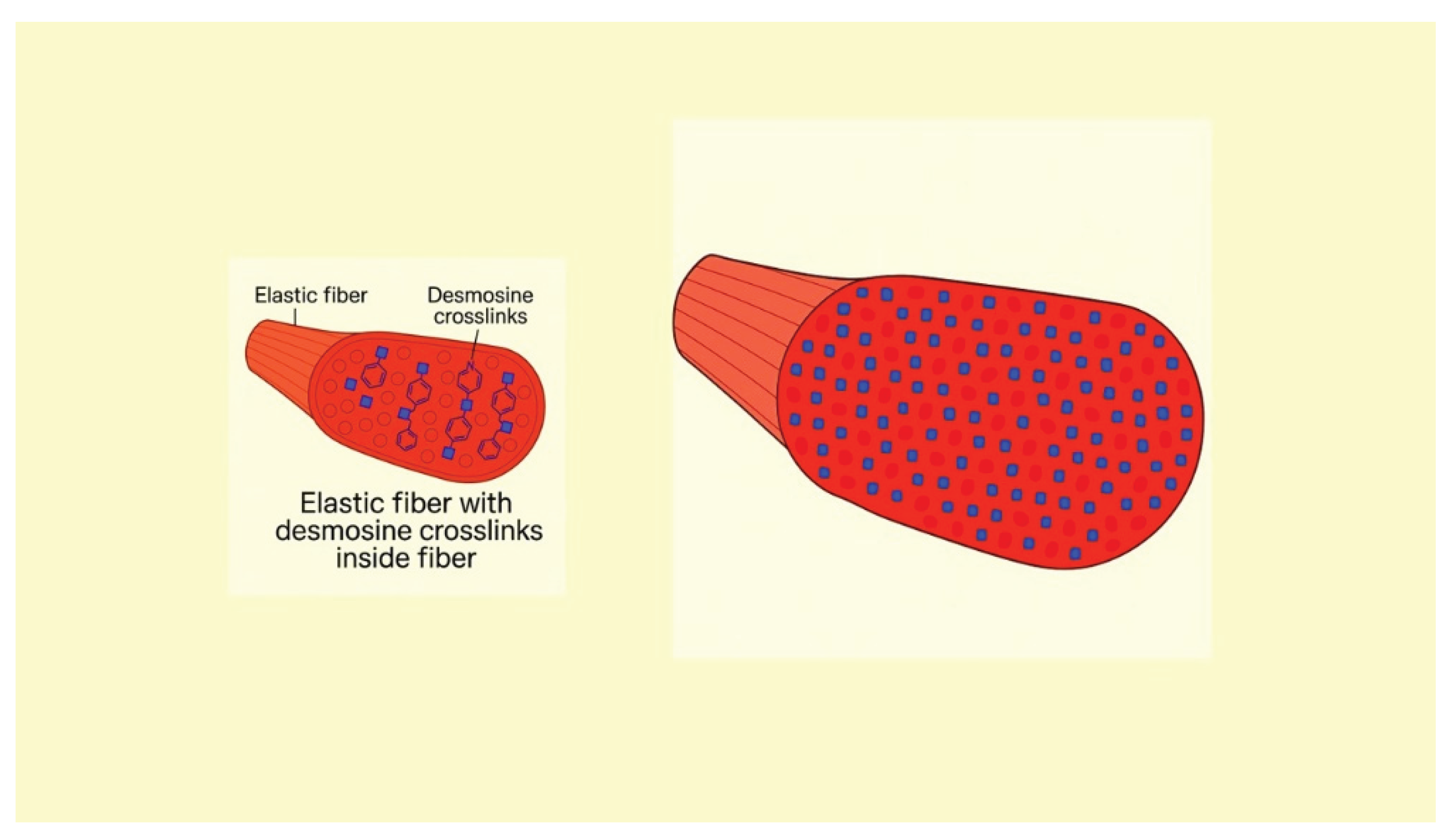

This relationship is supported by in vitro studies demonstrating that mechanical stretching enhances the formation of elastin crosslinks (

Figure 4). When subjected to tensile forces, elastin fibers undergo conformational changes that promote the interactions necessary for crosslinking (15). Additionally, mechanical stretching can increase the expression of lysyl oxidase (LOX), an enzyme that facilitates the crosslinking of elastin molecules (16).

These results suggest that the initial stages of alveolar wall injury are characterized by a balance between elastic fiber injury and repair in which greater crosslink density reflects enhanced elastin synthesis. However, when alveolar diameter exceeds 400 μm, the repair process undergoes a decompensatory phase reflected by a marked release of free DID and fragmentation of elastic fibers (11). The acceleration of elastin breakdown with increasing alveolar wall distention is consistent with the hypothesis that pulmonary emphysema is an emergent phenomenon involving a phase transition to an active disease state may be more resistant to therapeutic intervention. This transition may involve the loss of elastic fiber structural integrity as the effects of increasing alveolar wall strain cause the excessively crosslinked elastin to undergo fracture.

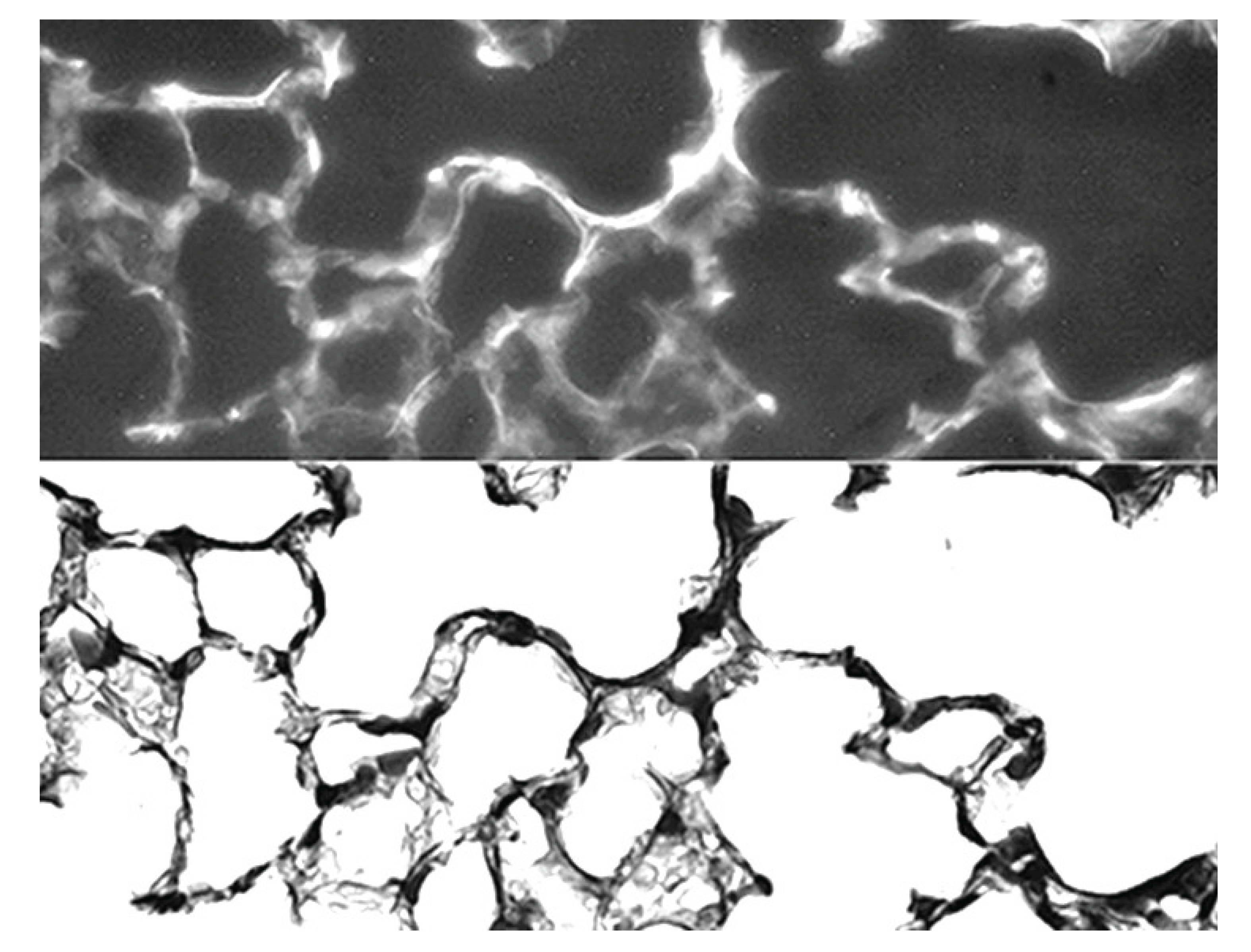

Although previous investigations have shown that pulmonary emphysema is associated with either similar or decreased elastic fiber content compared with normal lungs, our results suggest that earlier stages of the disease may involve a more balanced relationship between injury and repair, where the damaging effects of inflammation and alveolar wall strain are offset by increased elastin crosslinking (17). While there are few remaining lysine residues for crosslinking in mature elastic fibers, additional DID may result from the conversion of bifunctional crosslinks (e.g., lysinonorleucine) to DID (18). Alternatively, increased crosslink density may involve enhanced synthesis of elastin peptides incorporated into existing elastic fibers during the repair process (19). This mechanism is supported by immunofluorescence studies showing a significant correlation between alveolar wall elastin content and airspace size (

Figure 5) (11).

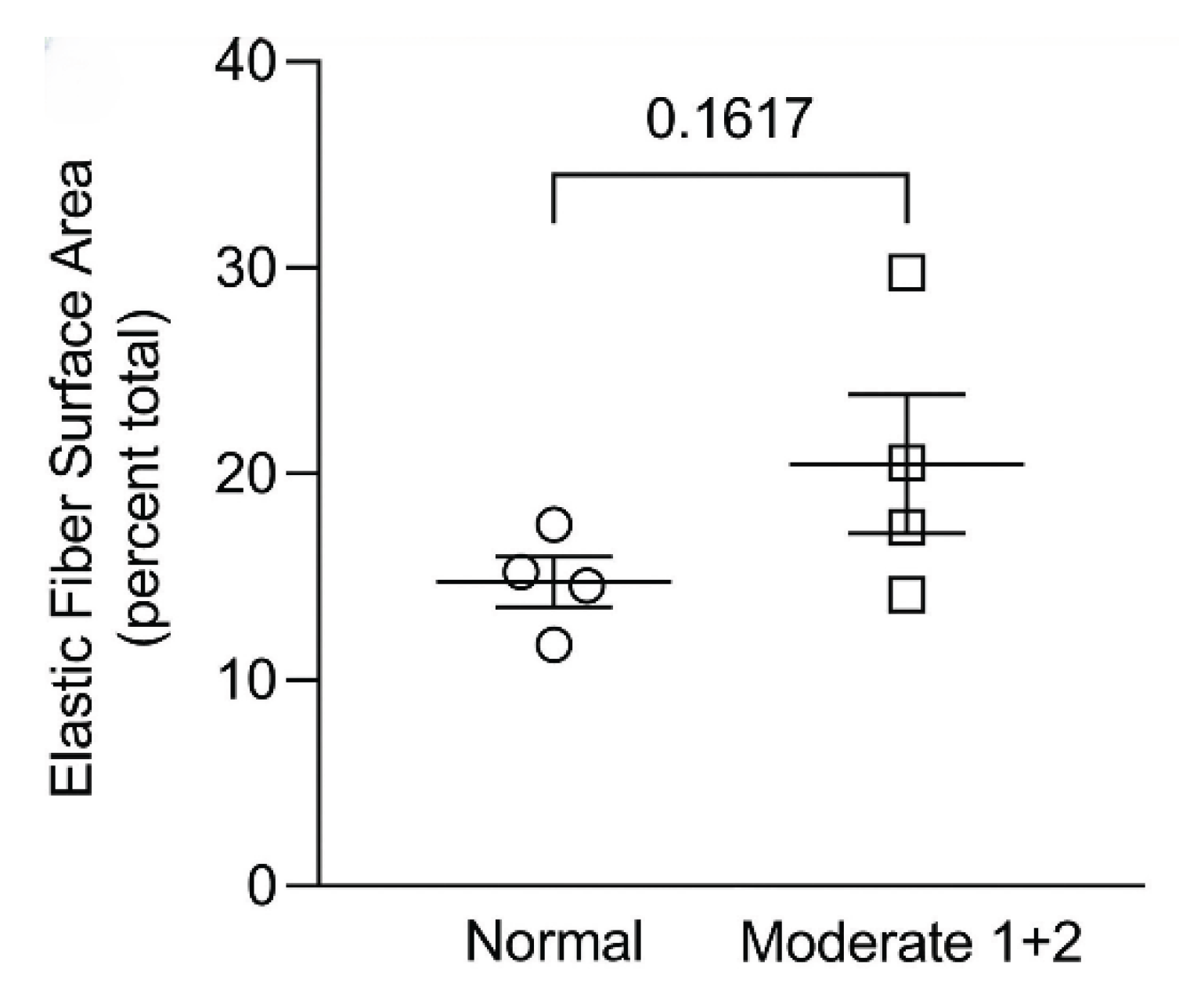

In contrast, alveolar wall elastic fiber surface area was not significantly increased, suggesting that the repair process mainly involves resynthesis of elastin rather than the entire fiber (

Figure 6) (11). Other studies support this concept by showing that de novo formation of intact elastic fibers in pulmonary emphysema is largely ineffective (20).

3. Fragmentation of Hypercrosslinked Elastic Fibers

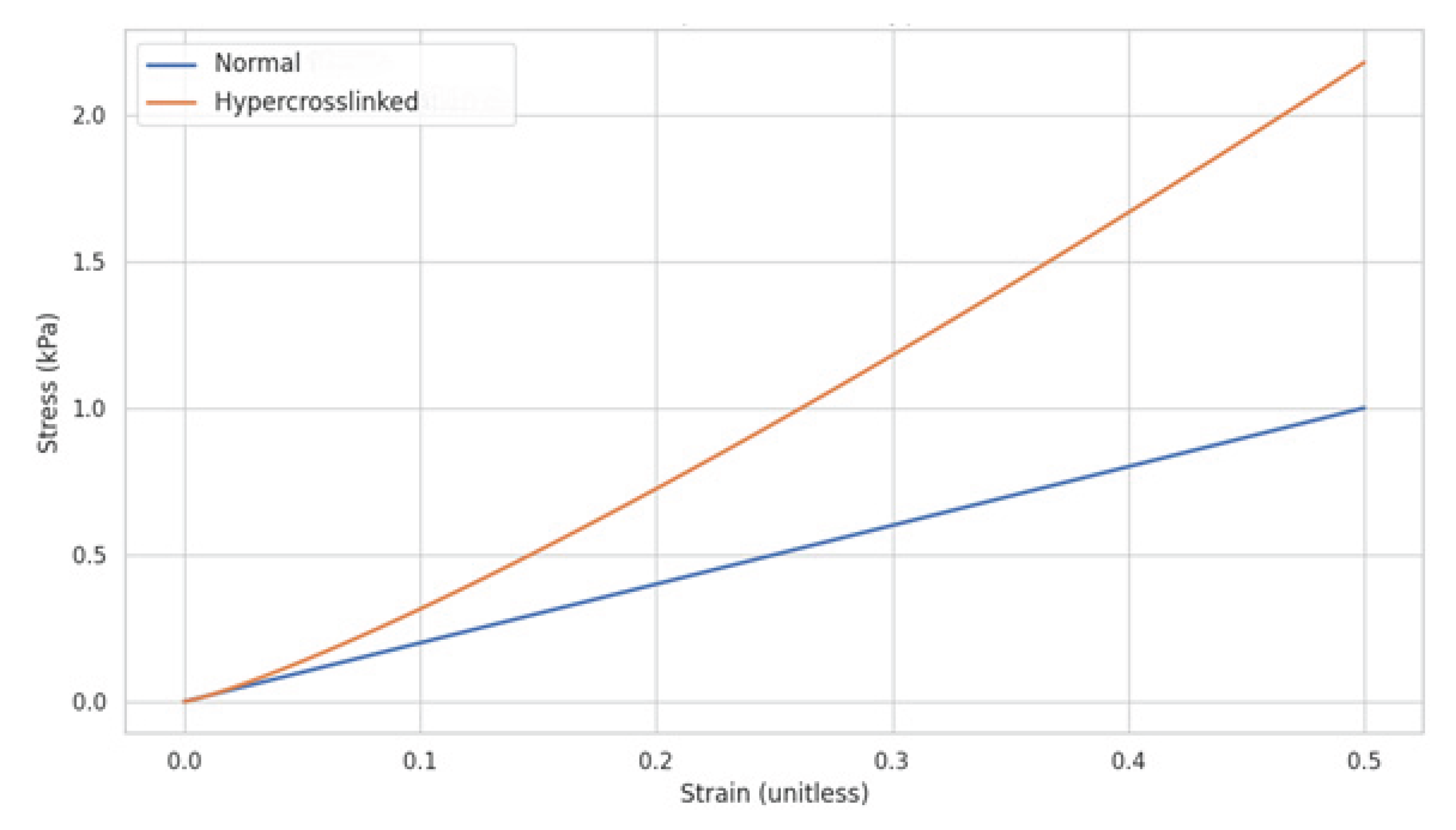

3.1. Elastin Rigidity Due to Hypercrosslinking:

It is hypothesized that the fragmentation of elastic fibers results from the continued increase in elastin rigidity, where the elastic modulus of a crosslinked polymer is directly proportional to the crosslink density (21, 22). A common formula used to describe this relationship is:

where the elastic modulus (E) is directly proportional to the polymer density (ρ), the ideal gas constant (R), and the absolute temperature (T), and inversely proportional to the molecular weight between crosslinks (Mc). A higher density usually means more polymer chains packed together, potentially leading to more crosslinks and a higher elastic modulus (21).

Limitations to this equation include the possibility that not all crosslinks are equally effective in contributing to the elastic modulus. Some may be located in regions where elastic fibers have undergone injury are therefore less effective in restricting chain movement (23). Nevertheless, once a critical threshold is reached, these fibers begin to rigidify, and its shear modulus grows with a power-law dependence on the crosslink density (

Figure 7).

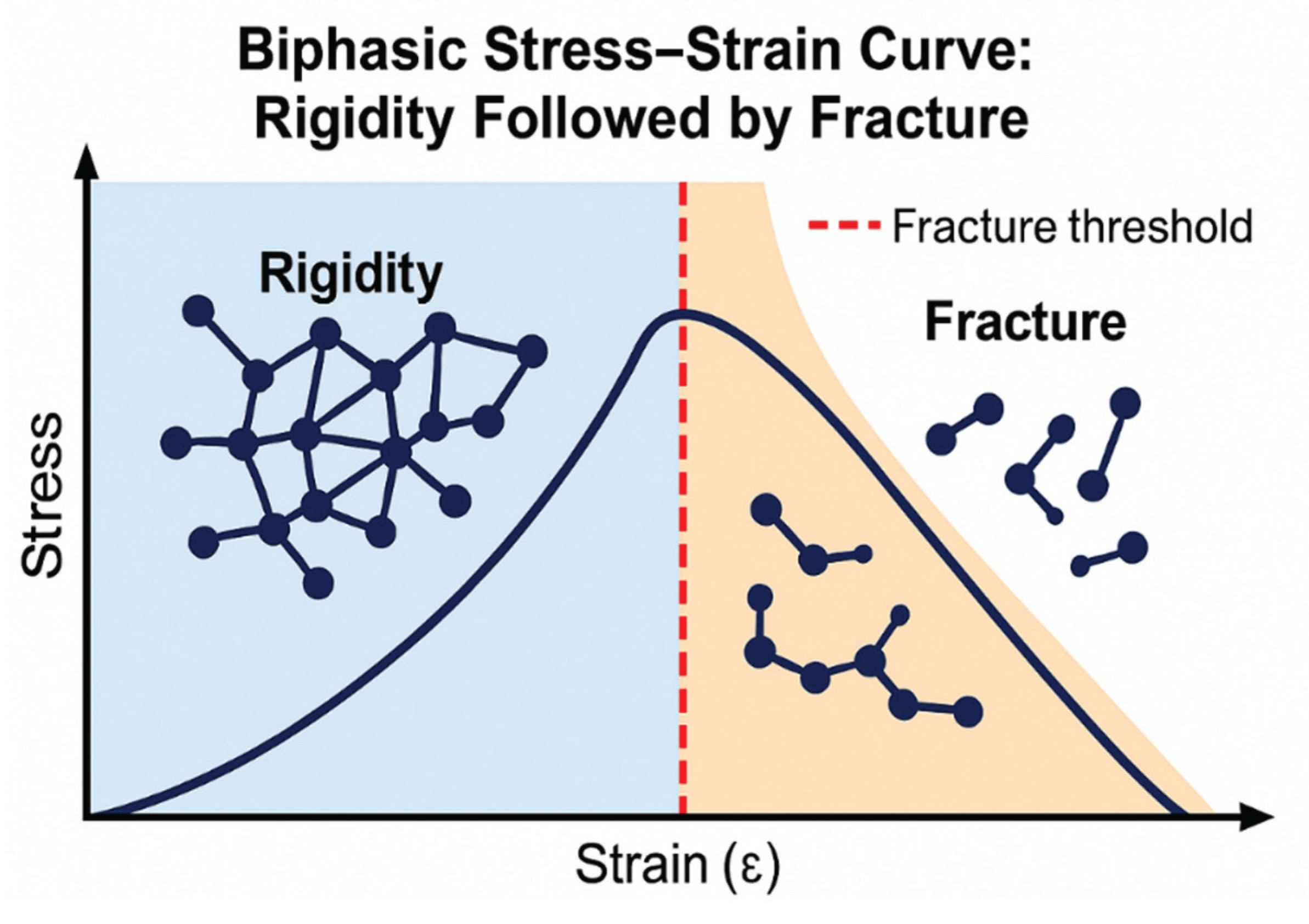

3.2. Biphasic Elastin Fracture Curve:

As elastin rigidity increases due to excessive crosslinking, it initially becomes more resistant to fracture. However, the continuation of this process results in a transition to a more rigid state, which increases the probability of fracture as alveolar wall strain intensifies (

Figure 8) (24, 25).

The biphasic relationship based on increasing elastin crosslink density may be expressed as follows:

where F represents the fracture resistance or strength of elastin, X represents the crosslink density, a is a constant that defines the shape of the pre-fracture curve, and b is a constant that determines how quickly the post-fracture curve falls off.

The similarity of the curve shown in

Figure 8 to one correlating elastic fiber surface area with airspace size in normal and emphysematous human postmortem lungs suggests that fragmentation of elastic fibers increases their susceptibility to enzymatic and oxidative degradation (

Figure 9).

4. The Role of Hydration in Elastic Fiber Fracture

One additional component that may play an important role in pulmonary mechanics is interstitial water content. In the case of elastic fibers, interactions between water molecules and hydrophobic amino acid groups within the core elastin protein are mainly responsible for elastic recoil. The absorption of water onto nonpolar hydrophobic groups during the elastin extension results in a positive free energy change that contributes to the storage of elastic energy (26). A decrease in water availability compromises this process, decreasing elastic fiber recoil. Water retention also facilitates the swelling of the elastin molecules, increasing their random energy state and enhancing recoil due to increased entropy loss during distention.

Resistance to stretching of the elastic fibers may also depend on the intramolecular forces of attraction among elastin peptide chains (27). Removing water molecules decreases the distance between the elastin peptide chains, enhancing their cohesion and reducing the distensibility of the fibers (28). This process is likely to occur in pulmonary emphysema, where the water loss may be due to the effects of decreased blood flow and damage to the hydrophilic components of the ECM. Studies of human lungs with emphysema have demonstrated a significant decrease in hyaluronan (HA), a long-chain, hydrophilic polysaccharide in proximity to elastic fibers (29). The loss of this component would adversely affect the viscoelastic properties of elastic fibers, increasing their susceptibility to fracture.

5. DID as a Biomarker of Therapeutic Efficacy

The accelerated release of free DID when airspace size exceeded 400 µm is consistent with the fragmentation of elastic fibers, where mechanical stress exceeds the fracture threshold for elastin (11). Conversely, a decline in tissue and fluid levels of DID following therapeutic intervention may indicate a shift in the remodeling of elastic fibers toward a more stable configuration, reducing the risk of alveolar wall rupture.

Currently, the only recognized endpoints for clinically evaluating the efficacy of treatments for pulmonary emphysema are lung function studies, which may not accurately reflect therapeutic efficacy (30). High-resolution CT offers a more sensitive alternative, but may require an extended period to determine a treatment effect on lung mass (31, 32). While a number of inflammatory mediators have also been proposed as therapeutic biomarkers for pulmonary emphysema, the level of DID crosslinks may have greater specificity for this disease because they are better indicators of structural changes in alveolar walls (33, 34).

While elastic fiber injury in blood vessels and other tissues could adversely affect the diagnostic role of the DID biomarker, it may nevertheless serve as a real-time indicator of therapeutic efficacy in clinical trials of novel treatment agents for pulmonary emphysema. A significant difference in crosslink levels between closely matched experimental and control groups would offset confounding factors and provide strong evidence of a positive treatment effect. Using sputum and possibly breath condensate to measure free DID would also increase the specificity for pulmonary emphysema.

To determine the role of DID levels in evaluating drug efficacy, our laboratory incorporated this biomarker in a 28-day clinical trial of hyaluronan (HA), a long-chain polysaccharide, in patients with alpha-1 antiprotease deficiency-induced pulmonary emphysema (35). Inhalation of aerosolized HA significantly decreased the amount of free DID in urine over the course of the trial, whereas levels in the placebo group remained unchanged. Free urinary DID was a more sensitive indicator of a treatment effect than total DID in either urine or plasma.

These results support the use of free DID as a biomarker for therapeutic efficacy and suggest that inhaled HA may slow the progression of pulmonary emphysema. The potential therapeutic effects of this agent are further supported by studies showing that inhalation of HA mitigated the loss of pulmonary function in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD and prevented bronchoconstriction in those with exercise-induced asthma.

6. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Elastin Preservation

6.1. Matrix Replacement Therapy:

The clinical trial involving aerosolized HA was based on a series of translational studies, beginning with one indicating that pretreatment with hyaluronidase increases airspace enlargement in an emphysema model induced by intratracheal elastase instillation (36). Subsequently, animals pretreated with HA were shown to have significantly less airspace enlargement in emphysema models induced by elastase or cigarette smoke (36).

This protective effect is due to the binding of HA to elastic fibers, where it functions as a physical barrier against various agents that degrade elastin but not as an elastase inhibitor (

Figure 10). The attachment of HA to elastic fibers may involve formation of electrostatic or hydrogen bonds. These binding sites may not be located on the elastin protein itself but may instead involve the microfibrillar component of elastic fibers. Due to its self-aggregating properties, the inhaled HA can produce large complexes that more effectively protect elastic fibers against elastases and the cells that secrete them (37).

HA may also prevent airspace enlargement by improving the mechanical properties of elastin. The negatively charged carboxyl groups within HA repel each other, expanding its domain and facilitating the entrapment of water (38). This property is crucial for regulating lung hydration, as the loss of HA from the lung interstitium has been shown to reduce extravascular water content. The interaction between water molecules and hydrophobic amino acid groups in elastin is responsible for producing a positive change in free energy that that expels air from the lung, preventing alveolar wall distention and rupture.

While it remains to be seen what effect exogenously administered HA will have on pulmonary mechanics, indirect evidence suggests that it may increase lung water content. Rats exposed to nebulized HA for 14 days showed a dose-dependent increase in lung weight, which was not due to cellular proliferation (unpublished data). Microscopically, no evidence of pulmonary edema was seen, consistent with the absorption of water by the extracellular matrix.

6.2. Crosslink Inhibition:

Targeting LOX with small molecule inhibitors represents another therapeutic strategy to mitigate pathological crosslinking (39). An example of this approach is the treatment of experimentally induced pulmonary fibrosis with β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN), an inhibitor of LOX. Decreasing the activity of this enzyme lowers crosslink density and modifies the biomechanical properties of the affected tissues.

In preclinical models of fibrosis, such as those involving lung, liver, or kidney tissues, administration of BAPN has demonstrated significant efficacy. In a murine model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, BAPN treatment resulted in decreased collagen deposition as evidenced by histological staining for collagen. Additionally, biochemical assays revealed a marked decline in the levels of soluble collagen and hydroxyproline, further supporting the notion that BAPN-induced LOX inhibition leads to alterations in ECM deposition. However, the toxicity of this agent may preclude its administration to humans, necessitating the use of other crosslink inhibitors such as penicillamine, which has a safety profile compatible with clinical trials (41).

Whether the dose of LOX inhibitors can be titrated to reduce elastin crosslinking without weakening alveolar wall structural integrity and promoting airspace enlargement remains to be seen. Optimizing the dosing regimen, evaluating the long-term safety of these agents, and exploring combination therapies with other antifibrotic agents will be crucial steps in translating these findings into an effective treatment for pulmonary emphysema. Additionally, developing more selective small-molecule inhibitors that specifically target LOX could minimize potential side effects.

6.3. Inhibition of Elastin-Derived Peptides:

An alternative therapeutic approach involves blocking the interaction between elastin-derived peptides (EDPs) and the elastin receptor complex (ERC), which may mitigate inflammation and elastic fiber injury (42). The release of EDPs during elastin degradation promotes vascular inflammation and stiffness due to their ability to activate various signaling pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells (7). This process leads to a cascade of events, including the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased MMP activity.

Recent studies have focused on developing NEU1 inhibitors and ERC antagonists as therapeutic agents that preserve vascular elasticity and prevent age-associated arterial stiffness (43). Neuraminidase 1 (NEU1) is an enzyme responsible for the desialylation of glycoproteins and glycolipids, a process thought to enhance the bioavailability of EDPs by exposing underlying receptor sites on cells (44). By inhibiting NEU1, it is hypothesized that the resulting reduction in EDP activity would limit the production of proinflammatory molecules responsible for the degradation and remodeling of elastic fibers.

An alternative strategy involves the use of ERC antagonists that prevent their interaction with EDPs, thereby blocking downstream signaling pathways that promote inflammation and remodeling. Recently developed ERC antagonists have shown efficacy in reducing EDP-induced vascular changes associated with elastic fiber remodeling in arterial walls (45).

Furthermore, studies suggest a synergistic effect of using NEU1 inhibitors alongside ERC antagonists, potentially amplifying their benefits in reducing inflammation and ECM deposition. However, this therapeutic strategy’s long-term efficacy and safety profile need to be determined before translating to the clinical setting.

6.4. Enhancing Tropoelastin Synthesis:

Strategies to upregulate tropoelastin expression may involve using several agents that promote elastin precursor synthesis and enhance matrix assembly in engineered tissues (46). Regarding this possibility, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) have significantly increased elastin synthesis (47).

Studies indicate that IGF-1 enhances tropoelastin expression in cultured fibroblasts following treatment with this agent (48). Elevated levels of tropoelastin protein were also seen, indicating that IGF-1 stimulates transcription and enhances translation of elastin precursors. Similarly, TGF-β1 has been shown in vitro to increase tropoelastin production, confirming its effect on gene expression and protein synthesis (49). These findings demonstrate the potential use of TGF-β1 and IGF-1 to promote elastin synthesis in alveolar walls at an early stage in the development of pulmonary emphysema, thereby preventing the mechanically induced distention that results in hypercrosslinking and fracture of elastic fibers.

In addition to using individual agents, biomimetic scaffolds and nanoparticles are being developed for the targeted delivery of multiple elastogenic molecules that support the regeneration of elastic fibers. Scaffolds combined with cytokines that promote elastogenesis significantly improved elastin deposition in vascular tissue, suggesting the possibility that inhaled biomaterials could preserve elastic fiber integrity and prevent alveolar wall injury (50).

7. Conclusions

Mechanical stress plays a central role in elastin degradation and remodeling of the ECM in pulmonary emphysema. The interplay between mechanical forces and biochemical processes leads to emergent phenomena that drive disease progression. Elastin degradation, a critical event in this process, is accompanied by increased crosslink density in elastic fibers, leading to their fracture. Therapeutic strategies that preserve elastin integrity and modulate ECM remodeling can alter pulmonary emphysema’s course. This approach will require a holistic understanding of the mechanical and biochemical factors that contribute to airspace enlargement, including the emergent phenomena responsible for the loss of alveolar wall elasticity.

References

- Karakioulaki, M.; Tzanakis, N. Extracellular matrix remodelling in COPD. European Respiratory Review 2020, 29(158), 190124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, J.K.; Weiss, D.J.; Westergren-Thorsson, G.; Wigen, J.; Dean, C.H.; Mumby, S.; Bush, A.; Adcock, I.M. Extracellular matrix as a driver of chronic lung diseases. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 2024, 70(4), 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopoulou, M. E.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Stolz, D. Matrix metalloproteinases in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(4), 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saputra, P. B.; Purwati, D. D.; Ulhaq, A. U. D.; Yolanda, S.; Djatioetomo, Y. C. E. D.; Rosyid, A. N.; Bakhtiar, A. Neutrophil elastase in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A review. Current Respiratory Medicine Reviews 2023, 19(1), 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S. P.; Bodduluri, S.; Reinhardt, J. M.; et al. Mechanically affected lung and progression of emphysema. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhana, R. H.; Magan, A. B. Lung mechanics: A review of solid mechanical elasticity in lung parenchyma. Journal of Elasticity 2023, 153(1), 53–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, A. Elastases and elastokines: elastin degradation and its significance in health and disease. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology 2020, 55(3), 252–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, B.; Parameswaran, H. Computational modeling helps uncover mechanisms related to the progression of emphysema. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models 2015, 15, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liao, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, R.; Zeng, Z.; Cheng, M.; Chen, J. Inhibition of neutrophil elastase prevents cigarette smoke exposure-induced formation of neutrophil extracellular traps and improves lung function in a mouse model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International Immunopharmacology 2023, 114, 109537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou, M. E.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Stolz, D. Matrix metalloproteinases in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(4), 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiola, M.; Reznik, S.; Riaz, M.; Qyang, Y.; Starcher, B. C. The relationship between elastin cross-linking and alveolar wall rupture in human pulmonary emphysema. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2023, 324(1), L1–L10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, B.; Bates, J. H. Lung tissue mechanics as an emergent phenomenon. Journal of applied physiology 2011, 110(4), 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessler, H. E.; Macklem, P. T. Percolation and phase transitions. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2007, 176(11), 1065–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagiola, M.; Gu, G.; Avella, J.; Cantor, J. Free lung desmosine: a potential biomarker for elastic fiber injury in pulmonary emphysema. Biomarkers 2022, 27(4), 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, S. E.; Muiznieks, L. D.; Stahl, R.; Simonetti, K.; Sharpe, S.; Keeley, F. W. Conformational transitions of the cross-linking domains of elastin during self-assembly. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289(14), 10057–10068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. J.; Jeng, J. H.; Chang, H. H.; Huang, M. Y.; Tsai, F. F.; & Jane Yao, C. C. Differential regulation of collagen, lysyl oxidase and MMP-2 in human periodontal ligament cells by low-and high-level mechanical stretching. Journal of periodontal research 2013, 48(4), 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mecham, RP. Elastin in lung development and disease pathogenesis. Matrix Biol 2018, 73, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schräder CU, Heinz A, Majovsky P, Karaman Mayack B, Brinckmann J, Sippl W, Schmelzer CEH. Elastin is heterogeneously cross-linked. J Biol Chem. 2018, 293(39), 15107–15119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stone PJ, Morris SM, Thomas KM, Schuhwerk K, Mitchelson A. Repair of elastase-digested elastic fibers in acellular matrices by replating with neonatal rat-lung lipid interstitial fibroblasts or other elastogenic cell types. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997, 17(3), 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifren, A.; Mecham, R. P. The stumbling block in lung repair of emphysema: elastic fiber assembly. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 2006, 3(5), 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Lin, X.; Liu, J.; Li, X. Effects of cross-link density and distribution on static and dynamic properties of chemically cross-linked polymers. Macromolecules 2018, 52(1), 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xian, W.; He, J.; Li, Y. Interplay between entanglement and crosslinking in determining mechanical behaviors of polymer networks. International Journal of Smart and Nano Materials 2023, 14(4), 474–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, C. A.; Sattari, S.; Ramirez, G. O.; Eskandari, M. Effects of tissue degradation by collagenase and elastase on the biaxial mechanics of porcine airways. Respiratory Research 2023, 24(1), 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trębacz, H.; Barzycka, A. Mechanical properties and functions of elastin: an overview. Biomolecules 2023, 13(3), 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burla, F.; Mulla, Y.; Vos, B.; Aufderhorst-Roberts, A.; Koenderink, G. From mechanical resilience to active material properties in biopolymer networks. Nature Rev. Phys. 2019, 1, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamhawi, N. M.; Koder, R. L.; Wittebort, R. J. Elastin recoil is driven by the hydrophobic effect. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121(1), e2304009121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depenveiller, C.; Baud, S.; Belloy, N.; Bochicchio, B.; Dandurand, J.; Dauchez, M.; Pepe, A.; Pomès, R.; Samouillan, V.; Debelle, L. Structural and physical basis for the elasticity of elastin. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 2024, 57, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Hahn J, Zhang Y. Mechanical Properties of Arterial Elastin With Water Loss. J Biomech Eng 2018, 140(4), 0410121-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cantor, J. O.; Armand, G.; Turino, G. M. Lung hyaluronan levels are decreased in alpha-1 antiprotease deficiency COPD. Respiratory Medicine 2015, 109(7), 861–866. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0954611115001055. [CrossRef]

- Cazzola, M.; Rogliani, P.; Barnes, P.J.; Blasi, F.; Celli, B.; Hanania, N.A.; Martinez, F.J.; Miller, B.E.; Miravitlles, M.; Page, C.P.; Tal-Singer, R. An update on outcomes for COPD pharmacological trials: a COPD investigators report-reassessment of the 2008 American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on outcomes for COPD pharmacological trials. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2023, 208(4), 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Qiao, C.; Dai, H.; Hu, Y.; Xi, Q. Diagnostic efficacy of visual subtypes and low attenuation area based on HRCT in the diagnosis of COPD. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2022, 22(1), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, P.; Bastos, H.N.E.; Carvalho, A.; Lobo, A.; Guimarães, A.; Rodrigues, R.S.; Zin, W.A.; Carvalho, A.R.S. Pulmonary emphysema regional distribution and extent assessed by chest computed tomography is associated with pulmonary function impairment in patients with COPD. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8, 705184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serban, K. A.; Pratte, K. A.; Bowler, R. P. Protein biomarkers for COPD outcomes. Chest 2021, 159(6), 2244–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S. R.; Kalhan, R. Biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Translational Research 2012, 159(4), 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, J.O.; Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Campos, M.A.; Strange, C.; Stocks, J.M.; Devine, M.S.; El Bayadi, S.G.; Lipchik, R.J.; Sandhaus, R.A.; Turino, G.M. A 28-day clinical trial of aerosolized hyaluronan in alpha-1 antiprotease deficiency COPD using desmosine as a surrogate marker for drug efficacy. Respiratory medicine 2021, 182, 106402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, J. Rodent Models of Lung Disease: A Road Map for Translational Research. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26(17), 8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocourková, K.; Musilová, L.; Smolka, P.; Mráček, A.; Humenik, M.; Minařík, A. Factors determining self-assembly of hyaluronan. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 254, 117307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Guo, X.; Zhang, K.; Kang, X.; Zhang, S.; Qian, L. Hyaluronic Acid Unveiled: Exploring the Nanomechanics and Water Retention Properties at the Single-Molecule Level. Langmuir 2024, 40(5), 2616–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; Li, W. LOX/LOXL in pulmonary fibrosis: potential therapeutic targets. Journal of drug targeting 2019, 27(7), 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canelón, S. P.; Wallace, J. M. β-Aminopropionitrile-induced reduction in enzymatic crosslinking causes in vitro changes in collagen morphology and molecular composition. PloS one 2016, 11(11), e0166392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, A.; Jia, J.; Popov, Y. V.; Schuppan, D.; You, H. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) family members: rationale and their potential as therapeutic targets for liver fibrosis. Hepatology 2020, 72(2), 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Shui, H.; Chen, R.; Dong, Y.; Xiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y. Neuraminidase-1 (NEU1): biological roles and therapeutic relevance in human disease. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2024, 46(8), 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembely, D.; Henry, A.; Vanalderwiert, L.; Toussaint, K.; Bennasroune, A.; Blaise, S.; Maurice, P. The elastin receptor complex: an emerging therapeutic target against age-related vascular diseases. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13, 815356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembely, D.; Bocquet, O.; Kawecki, C.; Debret, R. Characterization of novel interactions with plasma membrane NEU1 reveals new biological functions for the elastin receptor complex in vascular diseases. Atherosclerosis 2021, 332, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahart, A.; Hocine, T.; Albrecht, C.; Henry, A.; Sarazin, T.; Martiny, L.; Duca, L. Role of elastin peptides and elastin receptor complex in metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. The FEBS journal 2019, 286(15), 2980–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Shi, H.; Silveira, P. A.; Mithieux, S. M.; Wong, W. C.; Liu, L.; Weiss, A. S. Tropoelastin modulates systemic and local tissue responses to enhance wound healing. Acta Biomaterialia 2024, 184, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanik, F. F.; Verkoelen, N.; van Blitterswijk, C.; Rotmans, J.; Moroni, L. Control delivery of multiple growth factors to actively steer differentiation and extracellular matrix protein production. Advanced Biology 2021, 5(4), 2000205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krymchenko, R.; Coşar Kutluoğlu, G.; van Hout, N.; Manikowski, D.; Doberenz, C.; van Kuppevelt, T. H.; Daamen, W. F. Elastogenesis in focus: navigating elastic fibers synthesis for advanced dermal biomaterial formulation. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2024, 13(27), 2400484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procknow, S. S.; Kozel, B. A. Emerging mechanisms of elastin transcriptional regulation. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2022, 323(3), C666–C677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, H. A.; Qendro, E. I.; Alsberg, E.; Rolle, M. W. Targeted delivery of bioactive molecules for vascular intervention and tissue engineering. Frontiers in pharmacology 2018, 9, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).