Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. COPD Patient Exercise and Tissue Sampling

2.2. Mitochondrial Isolation

2.3. SDS-PAGE

2.4. Label-Free Mass Spectrometry

2.5. Enrichment Analysis and Hierarchical Clustering

2.6. ATPase Assay

2.7. Lipid Peroxidation Assay

2.8. Western Blot

2.9. P5cDH Gene Methylation

3. Results

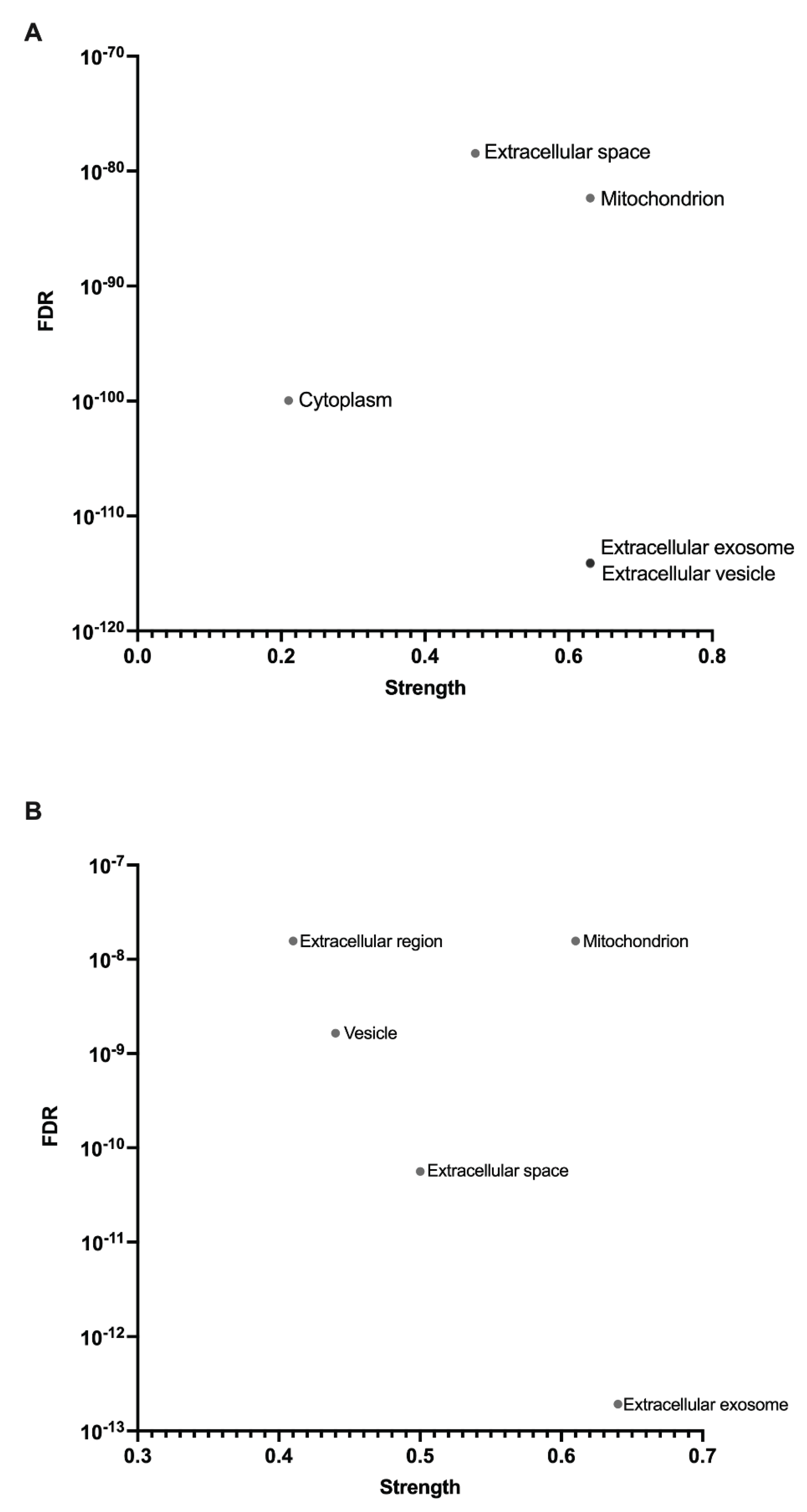

3.1. Isolated Mitochondrial Fractions Were Enriched with Mitochondrial Proteins

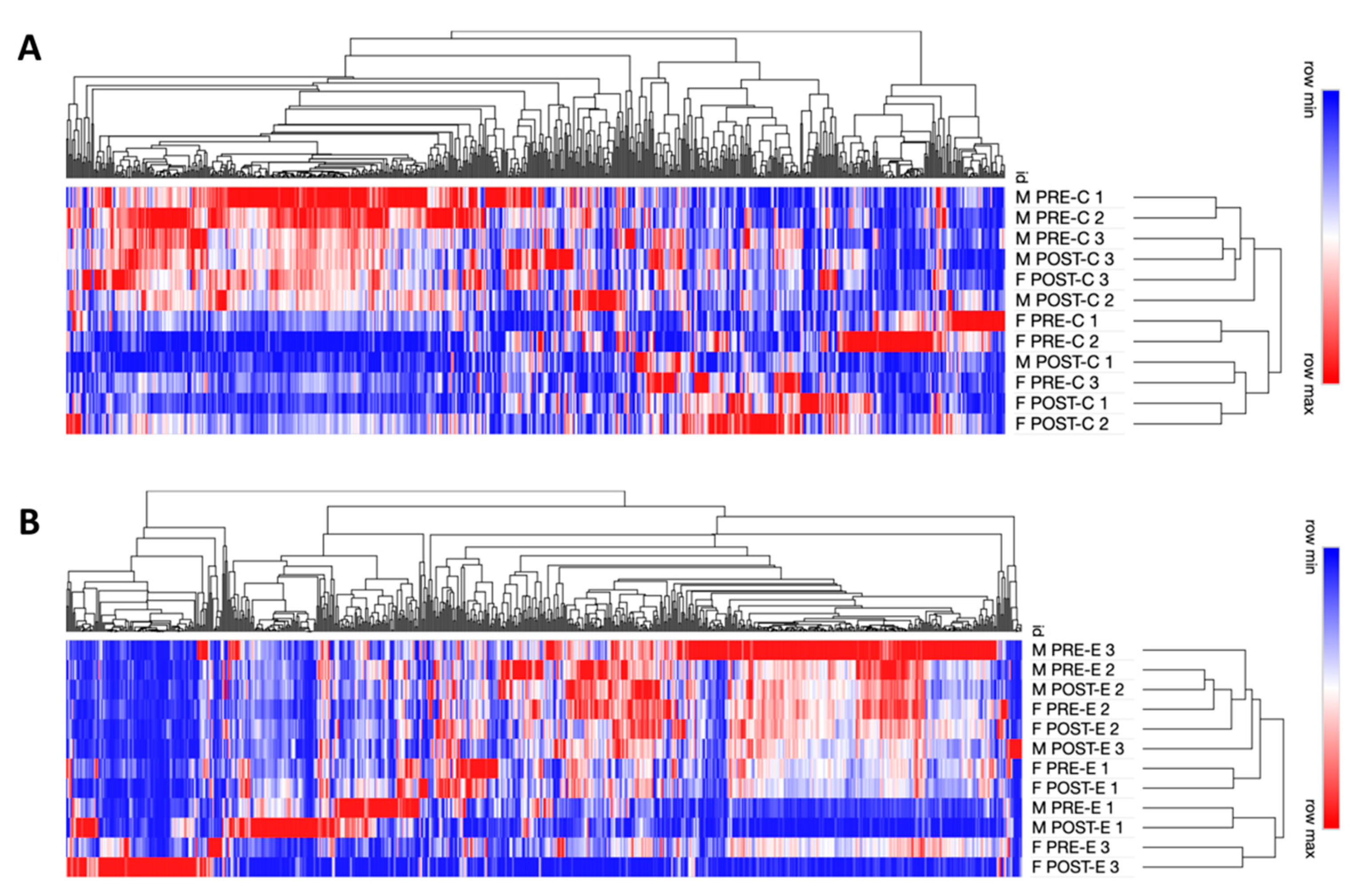

3.2. Changes to Protein Levels in Response to Concentric and Eccentric Exercise

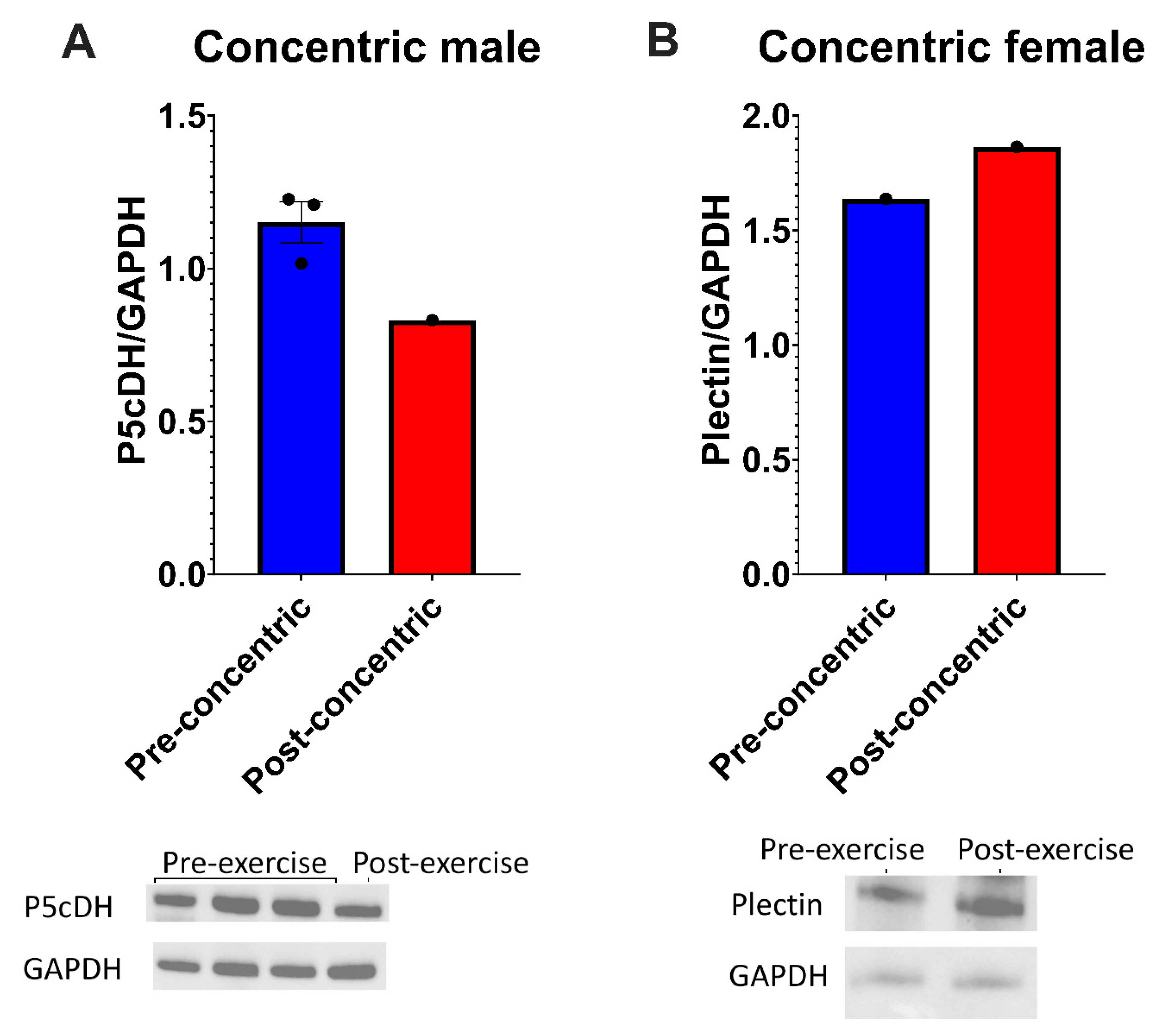

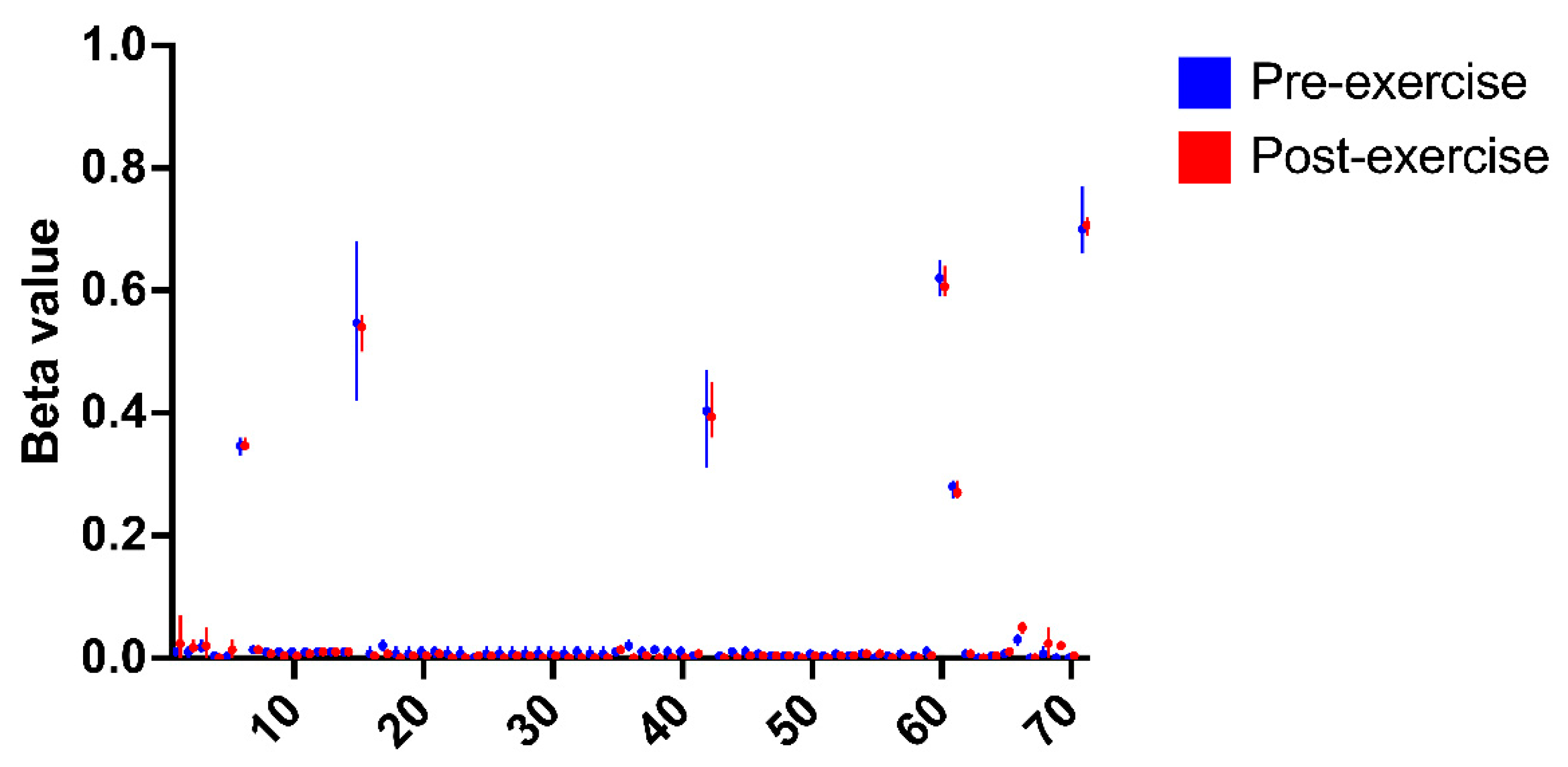

3.3. P5cDH Gene Methylation Is not the Mechanism for Decreased Abundance of this Protein Immediately After Concentric Exercise

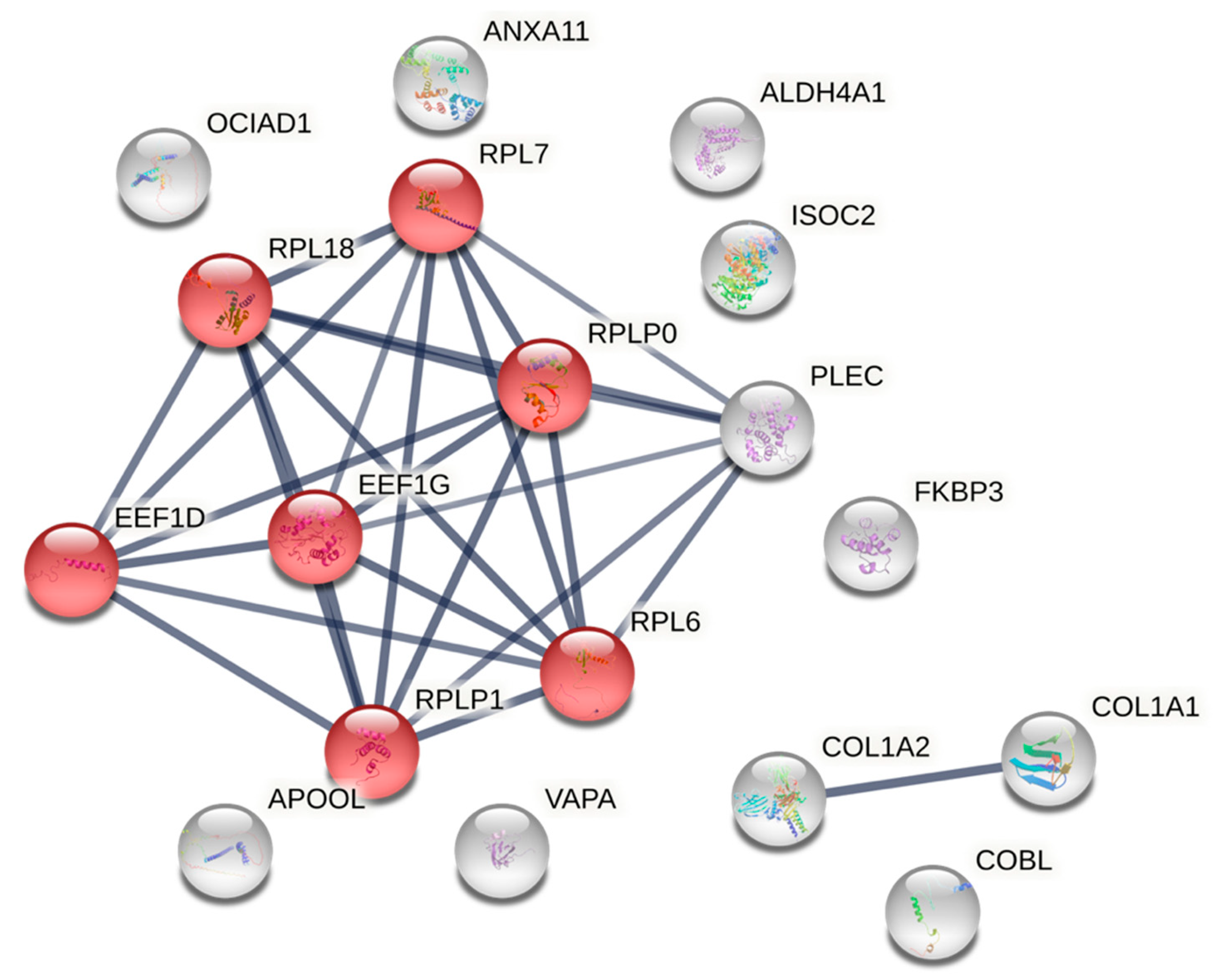

3.4. Concentric Exercise in COPD Males: Enrichment for Translation Elongation Factors

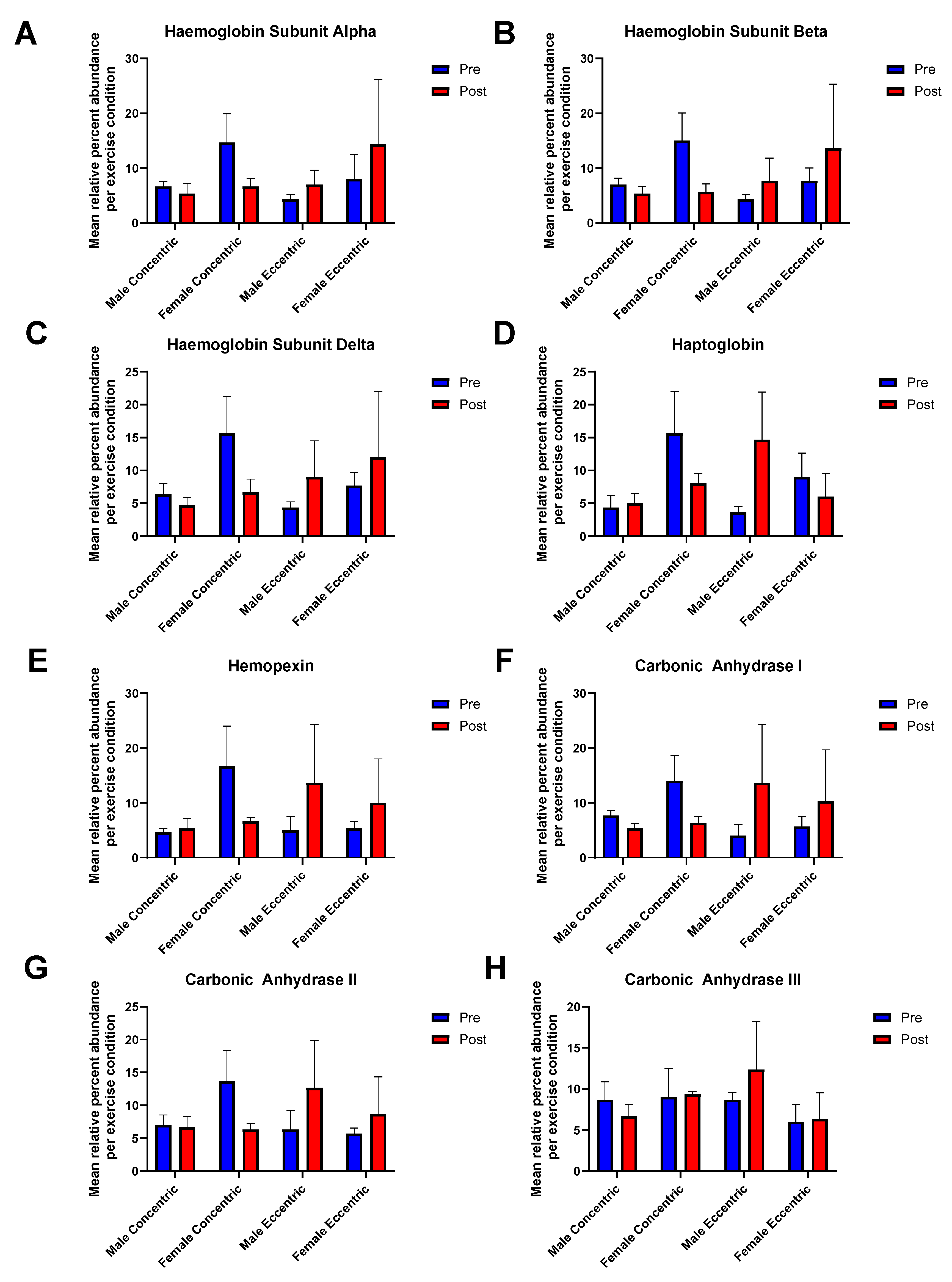

3.5. Carbonic Anhydrases I-III, Haemoglobin Subunits, and Haemoglobin Associated Proteins Are Present in COPD Skeletal Muscle Mitochondria

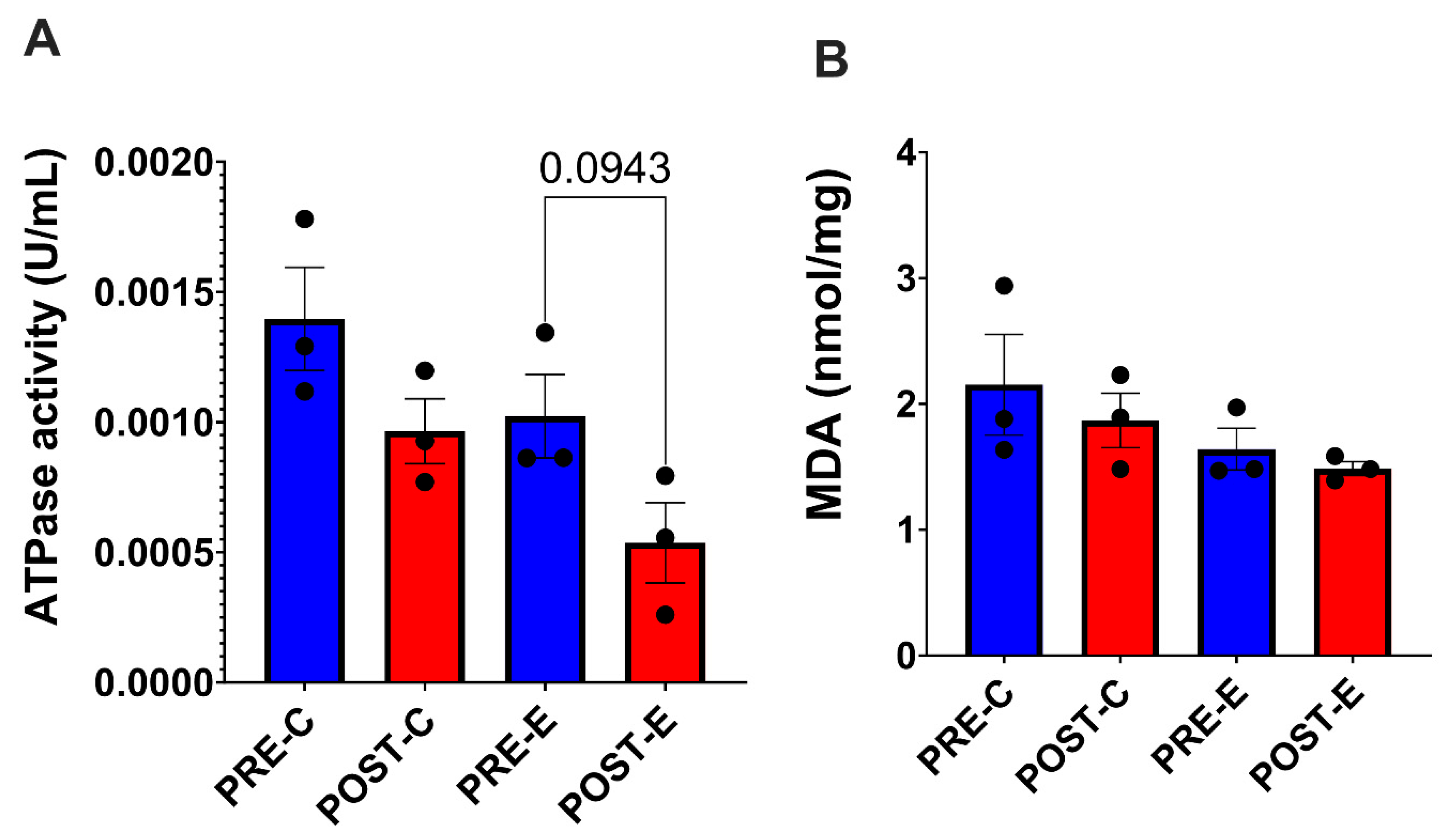

3.6. Tissue ATPase Activity and Levels of Lipid Peroxidation Did not Change Significantly in Response to Concentric or Eccentric Exercise

4. Discussion

4.1. Concentric Exercise Upregulates Plectin and Annexin Proteins in Male and Female Participants

4.2. Mitochondrial Protein Abundance Alterations Are Sex-Specific in Response to Concentric and Eccentric Exercise

4.3. Western Blotting Shows that P5cDH Is Decreased in Samples Not Analysed by Mass Spectrometry

4.4. Protein Translation and Elongation Factors Changed with Concentric Exercise in Males

4.5. Haemoglobin Subunits, Haptoglobin, Hemopexin, and Carbonic Anhydrases I, II and III Are Part of the Mitochondrial Proteome of COPD Skeletal Muscle

4.6. ATPase Activity and Levels of Lipid Peroxidation Are Unchanged in Response to Concentric and Eccentric Exercise

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adeloye, D.; Song, P.; Zhu, Y.; Campbell, H.; Sheikh, A.; Rudan, I.; Unit, N.R.G.R.H. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2022, 10, 447-458. [CrossRef]

- GOLD. Global Strategy for Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD.; 2022.

- Buist, A.S.; McBurnie, M.A.; Vollmer, W.M.; Gillespie, S.; Burney, P.; Mannino, D.M.; Menezes, A.M.; Sullivan, S.D.; Lee, T.A.; Weiss, K.B.; et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007, 370, 741-750. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2000, 343, 269-280. [CrossRef]

- Calverley, P.M. Respiratory failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J Suppl 2003, 47, 26s-30s. [CrossRef]

- Kent, B.D.; Mitchell, P.D.; McNicholas, W.T. Hypoxemia in patients with COPD: cause, effects, and disease progression. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011, 6, 199-208. [CrossRef]

- Wust, R.C.; Degens, H. Factors contributing to muscle wasting and dysfunction in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2007, 2, 289-300.

- Rabinovich, R.A.; Bastos, R.; Ardite, E.; Llinas, L.; Orozco-Levi, M.; Gea, J.; Vilaro, J.; Barbera, J.A.; Rodriguez-Roisin, R.; Fernandez-Checa, J.C.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in COPD patients with low body mass index. Eur Respir J 2007, 29, 643-650. [CrossRef]

- Puente-Maestu, L.; Perez-Parra, J.; Godoy, R.; Moreno, N.; Tejedor, A.; Gonzalez-Aragoneses, F.; Bravo, J.L.; Alvarez, F.V.; Camano, S.; Agusti, A. Abnormal mitochondrial function in locomotor and respiratory muscles of COPD patients. Eur Respir J 2009, 33, 1045-1052. [CrossRef]

- Haji, G.; Wiegman, C.H.; Michaeloudes, C.; Patel, M.S.; Curtis, K.; Bhavsar, P.; Polkey, M.I.; Adcock, I.M.; Chung, K.F.; consortium, C. Mitochondrial dysfunction in airways and quadriceps muscle of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res 2020, 21, 262. [CrossRef]

- Maremanda, K.P.; Sundar, I.K.; Rahman, I. Role of inner mitochondrial protein OPA1 in mitochondrial dysfunction by tobacco smoking and in the pathogenesis of COPD. Redox Biol 2021, 45, 102055. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Smith, S.B.; Yoon, Y. The short variant of the mitochondrial dynamin OPA1 maintains mitochondrial energetics and cristae structure. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 7115-7130. [CrossRef]

- Calverley, P.M.A. Exercise and dyspnoea in COPD. European Respiratory Review 15, 72-79. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, J.J.; Gilbert, R.; Gabe, R.; Auchincloss, J.H., Jr. Evaluation of an exercise therapy program for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1970, 102, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.J.C.; Lindley, M.R.; Ferguson, R.A.; Constantin, D.; Singh, S.J.; Bolton, C.E.; Evans, R.A.; Greenhaff, P.L.; Steiner, M.C. Submaximal Eccentric Cycling in People With COPD: Acute Whole-Body Cardiopulmonary and Muscle Metabolic Responses. Chest 2021, 159, 564-574. [CrossRef]

- Joschtel, B.; Gomersall, S.R.; Tweedy, S.; Petsky, H.; Chang, A.B.; Trost, S.G. Effects of exercise training on physical and psychosocial health in children with chronic respiratory disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2018, 4, e000409. [CrossRef]

- Padulo, J.; Laffaye, G.; Chamari, K.; Concu, A. Concentric and eccentric: muscle contraction or exercise? Sports Health 2013, 5, 306. [CrossRef]

- Dufour, S.P.; Lampert, E.; Doutreleau, S.; Lonsdorfer-Wolf, E.; Billat, V.L.; Piquard, F.; Richard, R. Eccentric cycle exercise: training application of specific circulatory adjustments. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004, 36, 1900-1906. [CrossRef]

- Rocha Vieira, D.S.; Baril, J.; Richard, R.; Perrault, H.; Bourbeau, J.; Taivassalo, T. Eccentric cycle exercise in severe COPD: feasibility of application. COPD 2011, 8, 270-274. [CrossRef]

- Hody, S.; Croisier, J.L.; Bury, T.; Rogister, B.; Leprince, P. Eccentric Muscle Contractions: Risks and Benefits. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 536. [CrossRef]

- Rattray, B.; Caillaud, C.; Ruell, P.A.; Thompson, M.W. Heat exposure does not alter eccentric exercise-induced increases in mitochondrial calcium and respiratory dysfunction. Eur J Appl Physiol 2011, 111, 2813-2821. [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, N.J.; Kapchinsky, S.; Konokhova, Y.; Gouspillou, G.; de Sousa Sena, R.; Jagoe, R.T.; Baril, J.; Carver, T.E.; Andersen, R.E.; Richard, R.; et al. Eccentric Ergometer Training Promotes Locomotor Muscle Strength but Not Mitochondrial Adaptation in Patients with Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front Physiol 2017, 8, 114. [CrossRef]

- Touron, J.; Costes, F.; Coudeyre, E.; Perrault, H.; Richard, R. Aerobic Metabolic Adaptations in Endurance Eccentric Exercise and Training: From Whole Body to Mitochondria. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 596351. [CrossRef]

- Isner-Horobeti, M.E.; Rasseneur, L.; Lonsdorfer-Wolf, E.; Dufour, S.P.; Doutreleau, S.; Bouitbir, J.; Zoll, J.; Kapchinsky, S.; Geny, B.; Daussin, F.N.; et al. Effect of eccentric versus concentric exercise training on mitochondrial function. Muscle Nerve 2014, 50, 803-811. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Kohler, M.; Heyder, T.; Forsslund, H.; Garberg, H.K.; Karimi, R.; Grunewald, J.; Berven, F.S.; Nyrén, S.; Magnus Sköld, C.; et al. Proteomic profiling of lung immune cells reveals dysregulation of phagocytotic pathways in female-dominated molecular COPD phenotype. Respiratory Research 2018, 19, 39. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Hoopmann, M.R.; Castaldi, P.J.; Simonsen, K.A.; Midha, M.K.; Cho, M.H.; Criner, G.J.; Bueno, R.; Liu, J.; Moritz, R.L.; et al. Lung proteomic biomarkers associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2021, 321, L1119-l1130. [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Ye, R.; Wang, C.; Sun, P.; Wang, D.; Yue, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Yu, M.; Xi, S.; et al. Identification of Proteomic Signatures in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Emphysematous Phenotype. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8, 650604. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Ahn, H.S.; Park, J.S.; Yeom, J.; Yu, J.; Kim, K.; Oh, Y.M. A Proteomics-Based Analysis of Blood Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of COPD Acute Exacerbation. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2021, 16, 1497-1508. [CrossRef]

- Ebanks, B.; Wang, Y.; Katyal, G.; Sargent, C.; Ingram, T.L.; Bowman, A.; Moisoi, N.; Chakrabarti, L. Exercising D. melanogaster Modulates the Mitochondrial Proteome and Physiology. The Effect on Lifespan Depends upon Age and Sex. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Ebanks, B.; Ingram, T.L.; Katyal, G.; Ingram, J.R.; Moisoi, N.; Chakrabarti, L. The dysregulated Pink1(-) Drosophila mitochondrial proteome is partially corrected with exercise. Aging (Albany NY) 2021, 13, 14709-14728. [CrossRef]

- Hoene, M.; Kappler, L.; Kollipara, L.; Hu, C.; Irmler, M.; Bleher, D.; Hoffmann, C.; Beckers, J.; Hrabe de Angelis, M.; Haring, H.U.; et al. Exercise prevents fatty liver by modifying the compensatory response of mitochondrial metabolism to excess substrate availability. Mol Metab 2021, 54, 101359. [CrossRef]

- David, D.C.; Hauptmann, S.; Scherping, I.; Schuessel, K.; Keil, U.; Rizzu, P.; Ravid, R.; Drose, S.; Brandt, U.; Muller, W.E.; et al. Proteomic and functional analyses reveal a mitochondrial dysfunction in P301L tau transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 23802-23814. [CrossRef]

- Granata, C.; Caruana, N.J.; Botella, J.; Jamnick, N.A.; Huynh, K.; Kuang, J.; Janssen, H.A.; Reljic, B.; Mellett, N.A.; Laskowski, A.; et al. High-intensity training induces non-stoichiometric changes in the mitochondrial proteome of human skeletal muscle without reorganisation of respiratory chain content. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 7056. [CrossRef]

- Walls, K.C.; Coskun, P.; Gallegos-Perez, J.L.; Zadourian, N.; Freude, K.; Rasool, S.; Blurton-Jones, M.; Green, K.N.; LaFerla, F.M. Swedish Alzheimer mutation induces mitochondrial dysfunction mediated by HSP60 mislocalization of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and beta-amyloid. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 30317-30327. [CrossRef]

- Broadwater, L.; Pandit, A.; Clements, R.; Azzam, S.; Vadnal, J.; Sulak, M.; Yong, V.W.; Freeman, E.J.; Gregory, R.B.; McDonough, J. Analysis of the mitochondrial proteome in multiple sclerosis cortex. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1812, 630-641. [CrossRef]

- Neilson, K.A.; Ali, N.A.; Muralidharan, S.; Mirzaei, M.; Mariani, M.; Assadourian, G.; Lee, A.; van Sluyter, S.C.; Haynes, P.A. Less label, more free: approaches in label-free quantitative mass spectrometry. Proteomics 2011, 11, 535-553. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, T.; Cox, J.; Mann, M. Proteomics on an Orbitrap benchtop mass spectrometer using all-ion fragmentation. Mol Cell Proteomics 2010, 9, 2252-2261. [CrossRef]

- Zubarev, R.A.; Makarov, A. Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 2013, 85, 5288-5296. [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D607-D613. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, D353-D361. [CrossRef]

- Shephard, F.; Greville-Heygate, O.; Marsh, O.; Anderson, S.; Chakrabarti, L. A mitochondrial location for haemoglobins--dynamic distribution in ageing and Parkinson's disease. Mitochondrion 2014, 14, 64-72. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 671-675. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, F.; Andrews, S.R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1571-1572. [CrossRef]

- Voisin, S.; Eynon, N.; Yan, X.; Bishop, D.J. Exercise training and DNA methylation in humans. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015, 213, 39-59. [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz, J.; Izquierdo, D.; Torres-Martos, A.; Baig, A.T.; Aguilera, C.M.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J. Impact of Physical Activity and Exercise on the Epigenome in Skeletal Muscle and Effects on Systemic Metabolism. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Shephard, F.; Greville-Heygate, O.; Liddell, S.; Emes, R.; Chakrabarti, L. Analysis of Mitochondrial haemoglobin in Parkinson's disease brain. Mitochondrion 2016, 29, 45-52. [CrossRef]

- Pollard, A.; Shephard, F.; Freed, J.; Liddell, S.; Chakrabarti, L. Mitochondrial proteomic profiling reveals increased carbonic anhydrase II in aging and neurodegeneration. Aging (Albany NY) 2016, 8, 2425-2436. [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.L.; Green, K.J.; Liem, R.K. Plakins: a family of versatile cytolinker proteins. Trends Cell Biol 2002, 12, 37-45. [CrossRef]

- Winter, L.; Wiche, G. The many faces of plectin and plectinopathies: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol 2013, 125, 77-93. [CrossRef]

- Reipert, S.; Steinbock, F.; Fischer, I.; Bittner, R.E.; Zeold, A.; Wiche, G. Association of mitochondria with plectin and desmin intermediate filaments in striated muscle. Exp Cell Res 1999, 252, 479-491. [CrossRef]

- Appaix, F.; Kuznetsov, A.V.; Usson, Y.; Kay, L.; Andrienko, T.; Olivares, J.; Kaambre, T.; Sikk, P.; Margreiter, R.; Saks, V. Possible role of cytoskeleton in intracellular arrangement and regulation of mitochondria. Exp Physiol 2003, 88, 175-190. [CrossRef]

- Winter, L.; Abrahamsberg, C.; Wiche, G. Plectin isoform 1b mediates mitochondrion-intermediate filament network linkage and controls organelle shape. J Cell Biol 2008, 181, 903-911. [CrossRef]

- Winter, L.; Kuznetsov, A.V.; Grimm, M.; Zeold, A.; Fischer, I.; Wiche, G. Plectin isoform P1b and P1d deficiencies differentially affect mitochondrial morphology and function in skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet 2015, 24, 4530-4544. [CrossRef]

- Rainteau, D.; Mansuelle, P.; Rochat, H.; Weinman, S. Characterization and ultrastructural localization of annexin VI from mitochondria. FEBS Lett 1995, 360, 80-84. [CrossRef]

- Chlystun, M.; Campanella, M.; Law, A.L.; Duchen, M.R.; Fatimathas, L.; Levine, T.P.; Gerke, V.; Moss, S.E. Regulation of mitochondrial morphogenesis by annexin A6. PLoS One 2013, 8, e53774. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Zhao, M.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, S.; Yao, X.; Gao, X.; Yang, S. Myostatin is involved in skeletal muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease via Drp-1 mediated abnormal mitochondrial division. Ann Transl Med 2022, 10, 162. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, I.; Ghosh, M.; Meinecke, M. MICOS and the mitochondrial inner membrane morphology - when things get out of shape. FEBS Lett 2021, 595, 1159-1183. [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.; Kondadi, A.K.; Meisterknecht, J.; Golombek, M.; Nortmann, O.; Riedel, J.; Peifer-Weiß, L.; Brocke-Ahmadinejad, N.; Schlütermann, D.; Stork, B.; et al. MIC26 and MIC27 cooperate to regulate cardiolipin levels and the landscape of OXPHOS complexes. Life Sci Alliance 2020, 3. [CrossRef]

- Bandela, M.; Suryadevara, V.; Fu, P.; Reddy, S.P.; Bikkavilli, K.; Huang, L.S.; Dhavamani, S.; Subbaiah, P.V.; Singla, S.; Dudek, S.M.; et al. Role of Lysocardiolipin Acyltransferase in Cigarette Smoke-Induced Lung Epithelial Cell Mitochondrial ROS, Mitochondrial Dynamics, and Apoptosis. Cell Biochem Biophys 2022, 80, 203-216. [CrossRef]

- He, F.; DiMario, P.J. Drosophila delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase (P5CDh) is required for proline breakdown and mitochondrial integrity-Establishing a fly model for human type II hyperprolinemia. Mitochondrion 2011, 11, 397-404. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xue, X.; Meng, L.; Li, D.; Qiao, W.; Wang, J.; Xie, D. Roles of autophagy-related genes in the therapeutic effects of Xuanfei Pingchuan capsules on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on transcriptome sequencing analysis. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1123882. [CrossRef]

- Maessen, M.F.H.; Schalkwijk, C.G.; Verheggen, R.; Aengevaeren, V.L.; Hopman, M.T.E.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H. A comparison of dicarbonyl stress and advanced glycation endproducts in lifelong endurance athletes vs. sedentary controls. J Sci Med Sport 2017, 20, 921-926. [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.; Strecker, V.; Urbach, J.; Wittig, I.; Reichert, A.S. Mic13 Is Essential for Formation of Crista Junctions in Mammalian Cells. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0160258. [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, S.; d'Alessi, F.; Romualdi, C.; Danieli, G.A. Differential expression of genes coding for ribosomal proteins in different human tissues. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 1152-1157. [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, A.N.; Perez, W.B.; Kinzy, T.G. The many roles of the eukaryotic elongation factor 1 complex. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2012, 3, 543-555. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, D.; Wang, T.; Ni, M.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Z. Prenatal LPS Exposure Promotes Allergic Airway Inflammation via Long Coding RNA NONMMUT033452.2, and Protein Binding Partner, Eef1D. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2023, 68, 610-624. [CrossRef]

- Gold, V.A.; Chroscicki, P.; Bragoszewski, P.; Chacinska, A. Visualization of cytosolic ribosomes on the surface of mitochondria by electron cryo-tomography. EMBO Rep 2017, 18, 1786-1800. [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Patgaonkar, M.; Shroff, A.; Ayyar, K.; Bashir, T.; Reddy, K.V. Hemoglobin expression in nonerythroid cells: novel or ubiquitous? Int J Inflam 2014, 2014, 803237. [CrossRef]

- Shah, G.N.; Hewett-Emmett, D.; Grubb, J.H.; Migas, M.C.; Fleming, R.E.; Waheed, A.; Sly, W.S. Mitochondrial carbonic anhydrase CA VB: differences in tissue distribution and pattern of evolution from those of CA VA suggest distinct physiological roles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 1677-1682. [CrossRef]

- Vullo, D.; Nishimori, I.; Innocenti, A.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase activators: an activation study of the human mitochondrial isoforms VA and VB with amino acids and amines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2007, 17, 1336-1340. [CrossRef]

- Torella, D.; Ellison, G.M.; Torella, M.; Vicinanza, C.; Aquila, I.; Iaconetti, C.; Scalise, M.; Marino, F.; Henning, B.J.; Lewis, F.C.; et al. Carbonic anhydrase activation is associated with worsened pathological remodeling in human ischemic diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc 2014, 3, e000434. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.A.; Lopes-Pacheco, M.; Rocco, P.R.M. Oxidative Stress-Derived Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Concise Review. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 6644002. [CrossRef]

- Ristow, M.; Zarse, K.; Oberbach, A.; Kloting, N.; Birringer, M.; Kiehntopf, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Kahn, C.R.; Bluher, M. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 8665-8670. [CrossRef]

| Sex | Exercise condition | Protein | Fold change | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Concentric | Elongation factor 1-delta | 5.666 | 0.039 |

| Annexin A11 | 3.166 | 0.045 | ||

| Plectin | 1.971 | 0.000 | ||

| Elongation factor 1-gamma | 1.59 | 0.030 | ||

| MICOS complex subunit MIC27 | 0.515 | 0.042 | ||

| 60S acidic ribosomal protein P1 | 0.449 | 0.015 | ||

| OCIA domain-containing protein 1 | 0.449 | 0.048 | ||

| Protein cordon-bleu | 0.394 | 0.038 | ||

| Delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase mitochondrial (P5cDH) | 0.375 | 0.042 | ||

| 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | 0.370 | 0.010 | ||

| Isochorismatase domain-containing protein 2 | 0.333 | 0.026 | ||

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase FKBP3 | 0.316 | 0.012 | ||

| Vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A | 0.316 | 0.037 | ||

| 60S ribosomal protein L18 | 0.253 | 0.038 | ||

| 60S ribosomal protein L6 | 0.250 | 0.032 | ||

| Collagen alpha-2(I) chain | 0.176 | 0.049 | ||

| 60S ribosomal protein L7 | 0.099 | 0.002 | ||

| Collagen alpha-1(I) chain | 0.000 | 0.018 | ||

| Eccentric | Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1 | 3.166 | 0.012 | |

| Hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolase mitochondrial (HAGH/GLO2) | 1.631 | 0.033 | ||

| Kelch-like protein 41 | 0.597 | 0.046 | ||

| Calpain-1 catalytic subunit | 0.578 | 0.015 | ||

| Myosin-9 | 0.429 | 0.043 | ||

| Complement C4-B | 0.408 | 0.033 | ||

| Cytosol aminopeptidase | 0.282 | 0.024 | ||

| Female | Concentric | Collagen alpha-1(VI) chain | 4.263 | 0.013 |

| Alpha-1-syntrophin | 3.949 | 0.022 | ||

| Collagen alpha-3(VI) chain | 3.166 | 0.000 | ||

| Myosin regulatory light chain 2 ventricular/cardiac muscle isoform | 2.961 | 0.028 | ||

| Heat shock protein beta-7 | 2.667 | 0.049 | ||

| Plectin | 2.333 | 0.041 | ||

| Annexin A6 | 1.564 | 0.038 | ||

| Vitronectin | 0.282 | 0.032 | ||

| Eccentric | T-complex protein 1 subunit delta | 0.754 | 0.049 | |

| Ryanodine receptor 1 | 0.190 | 0.023 | ||

| MICOS complex subunit MIC13 | 0.000 | 0.033 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).