1. Introduction

Ceramic restorations are contemporary restorations widely used in patients with high esthetic demands for correction of minor interdental spacing, shape and color of the teeth, particularly the anterior teeth. The success of such restorations depends mainly on the durability of the bond strength between tooth structure and ceramic substrate which is achieved by using luting cements [

1]. Luting cements are essential to bond the indirect restorations with the tooth surface. Traditionally zinc phosphate was used for cementation for more than a century and hence it is considered as gold standard against which all other cements are tested and compared [

2,

3,

4]. Other luting cements include zinc polycarboxylate, glass ionomer cement and the latest being the resin cements. Today resin cements are the materials of choice over other luting cements due to their superior properties such as resistance to wear, low solubility, high retention, versatility and long lasting and good aesthetics [

5]. Also they are biocompatible, there is absence of taste, odor and toxicity, have excellent optical properties and are repairable. Resin cements were introduced in dentistry in 1970s and since then have been the material of interest and focus among the dental practitioners and researchers.

Resin cements are composite materials with less viscosity and consist of fillers and initiators that facilitate lower film thickness along with adequate working and setting time [

6]. Dual-cure resin cement is preferred resin cements due to high degree of conversion. N. Hofmann et al found that when dual-cure resin cement was only self-cured (without light exposure), there was a steep decline in its strengths, flexural strength by 68.9%, elasticity by 59.2% and hardness by 86.1% compared to the one cured both by light and self-cure [

7]. They are used for cementation of full cast-metal crowns, ceramic crowns, zirconia constructions, indirect composite restorations, traditional metal–ceramic prosthesis, metal and glass fiber post, core build-up, implant-supported crowns and bridges, ceramic veneers, orthodontic braces and so on. They basically consist of an organic resin matrix, inorganic filler particles and a coupling agent that bonds them together.

There are various types of resin cements developed over years, each with some uniqueness. Earlier resin cements consisted of polymethyl methacrylate which underwent high polymerization shrinkage after curing and it’s compressive strength (CS) and flexural strengths (FS) were too low and to overcome this, the number of methacrylates was reduced with addition of filler particles [

8]. Contemporary resin cements use dimethacrylate monomers like bisphenol-A-glycidyl methacrylate (BisGMA), bisphenol-A-ethoxy dimethacrylate (BisEMA) and urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) [

9]. Of these monomers, BisGMA is the most used due to its high strength and hardness [

10]. These monomers cause polymerization shrinkage due to their high viscosity therefore diluents like TEGDMA (triethylene glycol dimethacrylate) and EGDMA (ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) are added to reduce viscosity and faciolitate increased filler content [

11]. If polymerization is incomplete, then it results in fast degradation of resin matrix leading to higher chances of fracture and debonding [

12].

Filler particles are added to resin matrix to enhance its properties. Various filler particles were used such as quartz, silica, oxides of zinc and aluminum, calcium silicate, zirconia nanofiller etc. [

13]. Also, hydroxyapatite crystals, barium silicate, strontium silicate, zinc silicate, lithium aluminium silicate, yttrium were also used. Improving compressive strength, tensile strength and elastic modulus is the basic purpose of adding these filler particles to the resin matrix [

14]. The recommended percentage of filler content in resin cement is between 10 wt% - 30 wt% because increasing the percentage of fillers from 10 wt% up to 70 wt% results in increased material rigidity leading to increased polymerization stresses and failure [

15]. When volume percentage is taken into consideration then the filler content should be between 31 vol%- 66 vol% [

16] and between 17.36 vol%-53.56 vol% [

17]. Filler particles of same size in the material often results in void formation hence incorporating filler particles of different sizes is advisable to improve packing density and the performance of rein cement [

18,

19]. Studies have found that the use of filler particles, their size and morphology, Silane treatment greatly improvise the strength and reduce the wear and polymerization shrinkage of resin cement [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

A good bond between the organic resin matric and inorganic filler particles is essential for a resin cement to last longer and this bonding is achieved using a binding agent called a coupling agent, usually silanes [

27]. Silane has the ability to bond between the hydroxyl groups of inorganic filler particles as well as methacrylate group of organic resin matrix [

10] and hydrolysis of Silane agents often jeopardizes the bond strength.

Good luting cement not only establishes a strong bond between tooth structure and the indirect restoration but also possesses excellent physical and mechanical properties to withstand occlusal forces. Bite forces range between 100N-320N [

28]. To withstand such a force the resin cement should have high compressive and flexural strength. Some of the causes of the failure of resin cement are microleakage and secondary caries, adhesive, cohesive and mixed failures, polymerization shrinkage and so on. Till date there is no resin cement available that possesses mechanical properties resembling that of ideal resin cement therefore resin cement has been the subject of extensive studies and investigation since their introduction in dentistry.

2. Materials and Methods

The materials used in this study were RelyX U200 dual-cure resin cement (3M ESPE), zirconia oxide nanoparticles (Vedayukt India Pvt Ltd), diamond nanoparticles (Vedayukt India Pvt Ltd) and 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate coupling agent (Tokyo Chemical Industry (India) Pvt Ltd). Three groups were prepared using these materials. The groups were as follows. Group 1: Commercial dual-cure resin cement, group 2: 10% Nanozirconia modified dual-cure resin cement, group 3: 10% Nanodiamond modified dual-cure resin cement. Nanozirconia and nanodiamond, each were added 10% volume to commercially available dual-cure resin cement RelyX U200. The volume was measured by using graduated test tube. Two different moulds made of clear acrylic were procured for testing compressive strength and flexural strength. The measurements of the moulds are as follows. Compressive strength moulds of size of 6mm height x 3mm diameter. Flexural strength moulds of size 25mm length x 2mm breadth x 2mm height.

Group 1- 11g of 100% RelyX U200 dual-cure resin cement was used as the control group. The base and catalyst were measured in small increments in equal quantities using digital weighing machine (Precision balance, LWL Germany, Model: LB-210S) and mixed manually over the glass slab to obtain a uniform mix. This mix was then loaded thoroughly in the moulds, avoiding air bubbles and voids formation. Then each sample was light cured for 40 seconds to obtain a well cured sample. Total 20 samples were prepared with 10 samples each for compressive strength and flexural strength testing. The samples were then removed from the moulds and polished at room temperature by using silicon carbide sandpapers of 1000, 1200, 1500 and 2000 grit. The samples were marked and stored at room temperature.

Group 2- 10% nanozirconia particles were mixed with coupling agent on a glass slab. This mixture was then added to base paste of commercial dual-cure resin cement (RelyX U200) taken on another glass slab. This base paste and the catalyst paste were then measured in small increments in equal quantity using digital weighing machine (Precision balance, LWL Germany, Model: LB-210S) and were mixed well on the glass slab and loaded in the moulds, avoiding air bubbles and voids formation. Then each sample was light cured for 40 seconds to obtain a well cured sample. Samples were prepared with 10 samples each for compressive strength and flexural strength testing. The samples were then removed from the moulds and polished at room temperature by using silicon carbide sandpapers of 1000, 1200, 1500 and 2000 grit. The samples were marked and stored at room temperature.

Group 3- Commercially available dual-cure resin cement (RelyX U200) was taken 90% by volume which is equivalent to 1067mg and 10% by volume nanodiamiond was measured using a graduated test tube. Similar process as that of group 2 preparation was followed to prepare group 3 using 10% nanodiamond particles by volume and the samples were stored at room temperature.

Compressive strength was measured according to ISO 4049/2019. The samples were cylindrical measuring 6mm height and 3mm diameter. The samples were placed vertically in the loading frame of computerized and software based universal instron testing machine (ACME Engineers, India Model No. UNITEST-10) and held securely using grips and load was gradually applied till the samples broke. The speed of the machine was 1mm/minute. The load at which the samples broke was recorded in newton and this value was converted to mega Pascal (MPa).

Flexural strength was measured according to ISO 4049/2019. The samples were rectangular shaped measuring 25mm length, 2mm breadth and 2mm in height. The samples were placed horizontally in the loading frame of the universal instron testing machine and held securely with grips and load was gradually applied at the head speed of 1mm/minute till the samples broke. The load measuring cell records the load applied. The load at which the samples fractured is recorded in newton and was converted to mega Pascal. The results were analysed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD Test.

3. Results

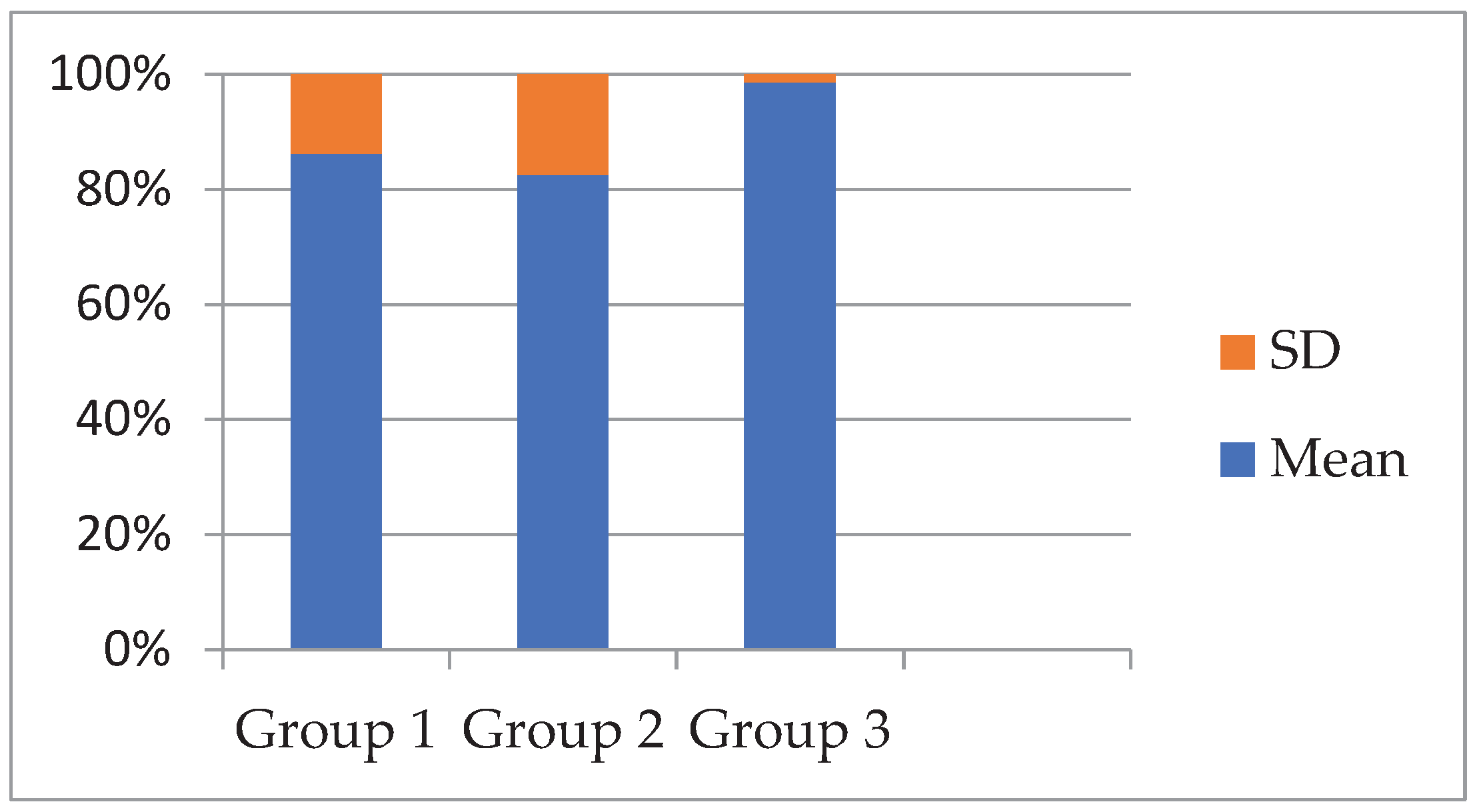

There was no statistically crucial difference in compressive strength among the groups (p = 0.505). Group II (Nano zirconia) had the highest mean compressive strength (132.18 ± 27.93 MPa), followed by Group III (Nano diamond) at 126.21 ± 12.54 MPa, and Group I (commercial cement) at 121.12 ± 19.35 MPa. While the trend suggests a slight improvement with Nano reinforcement, the statistical analysis does not support a meaningful difference between the groups.

Figure 1.

Comparison of compressive strength values of One-Way ANOVA test of all 3 groups.

Figure 1.

Comparison of compressive strength values of One-Way ANOVA test of all 3 groups.

Table 1.

Mean compressive strength values and one-way ANOVA values.

Table 1.

Mean compressive strength values and one-way ANOVA values.

| Variable |

Group1 (Mean±SD) |

Group2 (Mean±SD) |

Group3 (Mean±SD) |

F (df₁, df₂) |

p-value |

| Compressive strength |

121.12±19.35 |

132.18±27.93 |

126.21±12.54 |

F(2,27)=0.701

|

0.505 |

Table 2.

Post Hoc Multiple Comparison (Tukey HSD Test) values of CS.

Table 2.

Post Hoc Multiple Comparison (Tukey HSD Test) values of CS.

| Dependent Variable |

Comparison Groups |

Mean Difference (I–J) |

Standard Error |

p-value |

95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

| Compressive Strength |

Group 1 vs Group 2

|

-11.060

|

9.353

|

0.473 |

-34.229

|

12.109

|

Group 1 vs Group 3

|

-5.973 |

9.353

|

0.850

|

-29.143

|

17.196 |

| Group 2 vs Group 3 |

5.087 |

9.353 |

0.910 |

-18.083

|

28.257

|

Insignificant differences were observed between the groups for compressive strength (p > 0.05), suggesting that the addition of nano fillers did not meaningfully alter the compressive properties of the resin cement.

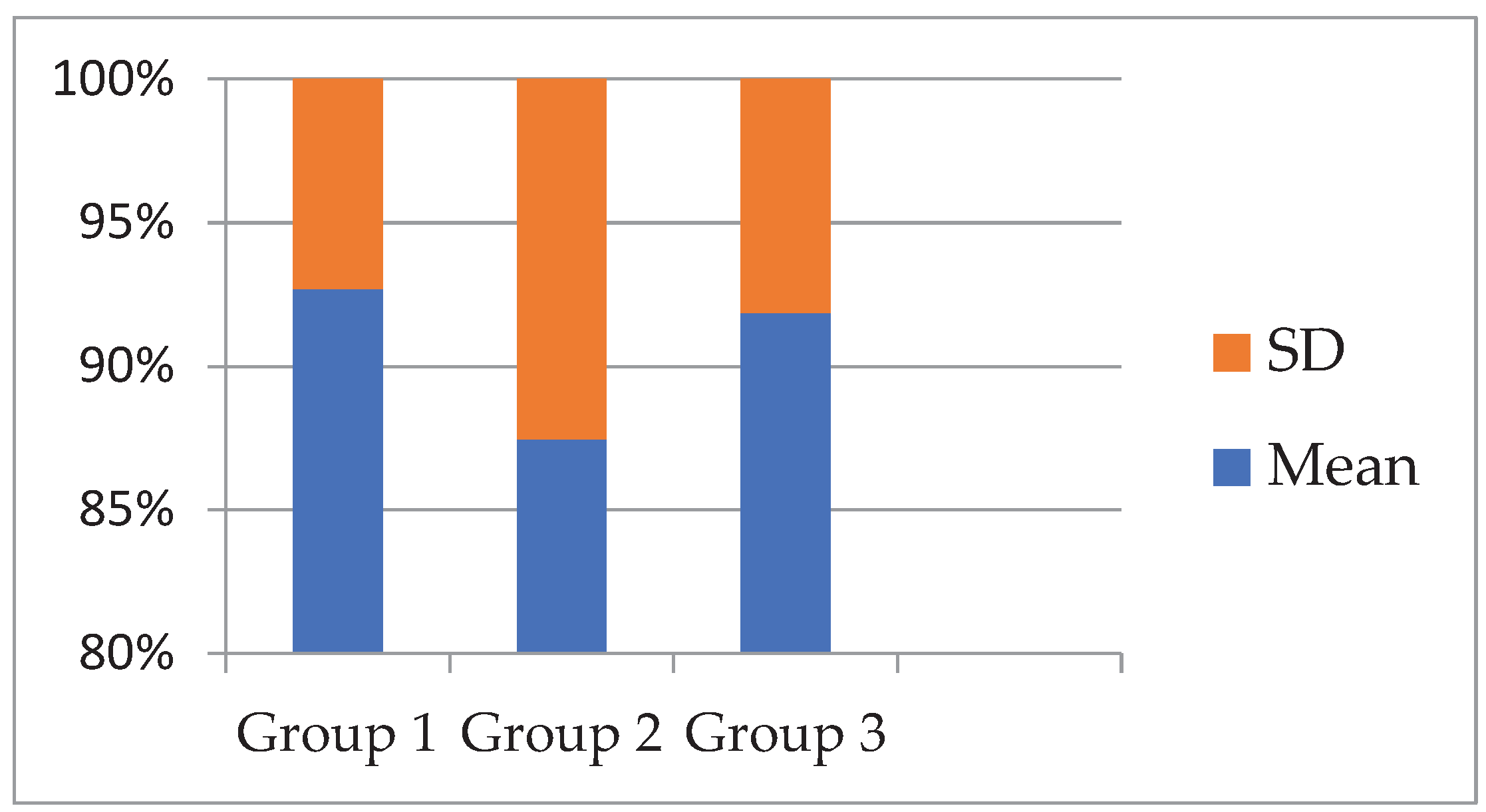

There was no statistically prominent difference in flexural strength among the three groups (p = 0.256). Group II (Nano zirconia) had the maximum mean flexural strength (72.50 ± 10.40 MPa), followed closely by Group III (Nano diamond) at 71.06 ± 6.30 MPa, and Group I (unmodified resin cement) at 66.92 ± 5.27 MPa. Although the modified groups demonstrated numerically higher values, the lack of statistical significance indicates that these differences may be due to random variation and not the effect of nanoparticle modification.

Figure 2.

Comparison of flexural strength values of One-Way ANOVA test of all 3 groups.

Figure 2.

Comparison of flexural strength values of One-Way ANOVA test of all 3 groups.

Table 3.

Mean flexural strength values and one-way ANOVA values.

Table 3.

Mean flexural strength values and one-way ANOVA values.

| Variable |

Group1 (Mean± SD) |

Group2 (Mean± SD) |

Group3 (Mean± SD) |

F (df₁, df₂) |

p-value |

| Flexural strength |

66.92 ± 5.27 |

72.50 ± 10.40 |

71.06 ± 6.30 |

F(2, 27) = 1.435 |

0.256

|

Table 4.

Post Hoc Multiple Comparison (Tukey HSD Test) values of flexural strength.

Table 4.

Post Hoc Multiple Comparison (Tukey HSD Test) values of flexural strength.

| Dependent Variable |

Comparison Groups |

Mean Diffe ence (I–J) |

Standard Error |

p-value |

95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

| Flexural Strength |

Group 1 vs

Group 2

|

-5.580 |

3.420

|

0.250

|

-14.061

|

2.901

|

Group 1 vs

Group 3

|

-4.144 |

3.420 |

0.457 |

-12.625 |

4.337 |

Group 2 vs

Group 3 |

1.436 |

3.420 |

0.909 |

-7.045 |

9.917 |

Insignificant variations were noted between any of the groups (p > 0.05), indicating that the type of resin cement had no notable impact on flexural strength.

4. Discussion

Nanoparticles have large surface area and disperse easily in the polymer resin matrix and hence enhance the physical and mechanical properties of the resin cements. There are various nanoparticles used so far such as silicate, aluminum, titanium, zirconia etc. and all of them have been successful in improving different mechanical properties in varying degree. In this study zirconia and diamond NPs are used and their effect on compressive strength and flexural strength is being studied.

ZrO

2 is 96%-99% crystalline because of which it has high flexural strength, fracture toughness, and hardness, increased mechanical properties, satisfactory esthetics, and excellent biocompatibility [

29].

Diamond nanoparticles are widely considered as smart nanomaterials because of their extreme hardness, thermal conductivity, biocompatibility, thermal expansion, optical transparency, chemical corrosion resistance and electrical insulation [

32,

33]. The properties of diamond nanoparticles is superior to bulk diamond form [

34,

35].

This study was conducted to compare the compressive strength and flexural strength of commercially available dual cure resin cement (RelyX U200, 3M ESPE) with that of its modification using 10% nanozirconia and 10%nanodiamond particles.

A total of 3 groups were prepared with each group having 20 samples. Since the mechanical properties of zirconia and diamond nanoparticles are superior so the idea in this study is to capitalize it and improvise the compressive strength and flexural strength of existing dual cure resin cement.

Compressive strength: It is the ability of a material to resist a force applied on it before it fractures. It is also the capacity of a material to resist a load that tends to reduce its size. CS is a very critical factor in success of the materials since high CS is essential to withstand masticatory and Para-functional stresses [

41,

42,

43]. In this study Compressive strength of group 1, group 2 and group 3 was found to be 121.12 ± 19.35, 132.18 ± 27.93, 126.21 ± 12.54, respectively. Amongst the three group, the CS of commercially available dual-cure resin cement was lowest followed by that of the resin cement modified with 10% nanodiamond filler and the highest CS was found with resin cement modified with 10% nanozirconia fillers. Though there was a slight improvement in the CS of both the modified resin cements compared to the RelyX U200 but the change was very minor and insignificant.

The compressive strength of zirconia nanoparticles is 2000 MPa [

30] as a result they are the material of high interest in various fields and have proven to be highly efficient and useful. They have been used as filler particles in various dental cements, including resin cements, and the outcome has been promising in improving the mechanical properties of the cements. Current study focuses on the effect of zirconia nanoparticles on CS of resin luting cement and the results are not satisfactory as there is only a minor improvement in CS of resin cement. This is contrary to the findings of a previous study in which significant improvement in CS was noted and higher CS was noted with higher the percentage of zirconia NPs [

44]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous study conducted using nanodiamond to evaluate their effect on compressive strength of luting resin cement. Though diamond nanoparticles are a hard and strong material so their addition was expected to enhance CS of resin cement but in this study we found very minimal improvement hence first null hypothesis was partially rejected.

Flexural strength: It is the ability of the material to withstand bending under the external force and it is determined by the highest load the material can withstand before its failure. The flexural strengths obtained in this study for group 1, group 2 and group 3 are 66.92 ± 5.27, 72.50 ± 10.40, 71.06 ± 6.30 respectively. The results were similar to that of compressive strength, that is, though there was a minor improvement in the flexural strength of experimental groups compared to control group but the change was insignificant.

The results of this study are in agreement with that of the previous study conducted wherein it was found that the addition of zirconia nanoparticles partially improved FS of resin cement and the change was insignificant [

45]. It also agrees with the studies conducted earlier wherein it was found that the type and loading of filler particles affects the FS [

38,

46,

47]. One more finding in this study, when compared to the study conducted by Raja Azman Raja Awang et al. is that the percentage of zirconia nanoparticles added is directly proportional to the FS [

49], but increasing it also increases the rigidity of the resin cement [

17] which is undesirable for a luting cement, though it is essential for restorative resins wherein a very high FS is more desirable [

48,

50,

51,

52,

53]. This study, however, is in conflict with the findings of other studies wherein incorporation of zirconia NPs was found to enhance the flexural strength of resin matrix [

54,

55,

56] .Based on the findings of this study, second null hypothesis is partially rejected as there is no significant change in the CS values of experimental resin cements.

Similarly, the addition of diamond nanoparticles also partially enhanced the flexural strength of the resin cement. Though there is no previous study on the effect of ND particles on flexural strength of resin luting cements but there is a study conducted on their effect on PMMA denture base resins and it was found that NDs enhance the FS of denture base resin [

57]. In that study it was found that addition of low concentration of ND (0.1% and 0.25%) had higher FS compared to that of higher concentration of NDs (0.5%). Similar findings were observed in another study conducted on denture base resins [

58]. These studies could possibly explain the reason for marginal improvement in the FS values with addition to a much higher percentage of NDs (10%) in this study. Though further investigation is warranted on this subject for confirmation.

5. Conclusions

The addition of 10% zirconia and 10% diamond nanoparticles improved the compressive strength and flexural strength of the commercially available dual cure resin cement. But the results were insignificant. The outcome of the study could be affected by various factors like the size of nanoparticles, percentage of nanoparticles, and method of the preparation of samples. Further research is required to check other properties including physical and biological.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; methodology, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; software, Saleem D. Makandar.; validation, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; formal analysis, Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; investigation, Saleem D. Makandar.; resources, Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; data curation, Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; writing—original draft preparation, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; writing—review and editing, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; visualization, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; supervision, Saleem D. Makandar.; project administration, Saleem D. Makandar.; funding acquisition, Saleem D. Makandar. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This work was supported by a Universiti Sains Malaysia, Short-Term Grant with project no: R501-LR-RND002-0000001125-0000”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

“This work was supported by a Universiti Sains Malaysia, Short-Term Grant with project no: R501-LR-RND002-0000001125-0000”.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BisGMA |

bisphenol-A-ethoxy dimethacrylate |

| BisEMA |

bisphenol-A-ethoxy dimethacrylate |

| UDMA |

urethane dimethacrylate |

| CS |

Compressive strength |

| FS |

Flexural Strength |

| DCRC |

Dual cure resin cement |

References

- Peumans, M.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Lambrechts, P.; Vanherle, G. Porcelain Veneers: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Dentistry 2000, 28, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heboyan, A.; Vardanyan, A.; Karobari, M.I.; Marya, A.; Avagyan, T.; Tebyaniyan, H.; Mustafa, M.; Rokaya, D.; Avetisyan, A. Dental Luting Cements: An Updated Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, E.E. Dental Cements for Definitive Luting: A Review and Practical Clinical Considerations. Dental Clinics of North America 2007, 51, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, G.K.-H.; Wong, A.W.-Y.; Chu, C.-H.; Yu, O.Y. Update on Dental Luting Materials. Dentistry Journal 2022, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.; Lott, J. A Clinically Focused Discussion of Lutin ungg Materials. Australian Dental Journal 2011, 56, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materials for Adhesion and Luting- Craig’s restorative dental materials- 14th Edition, 2019, 273-294. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, N.; Papsthart, G.; Hugo, B.; Klaiber, B. Comparison of Photo-Activation versus Chemical or Dual-Curing of Resin-Based Luting Cements Regarding Flexural Strength, Modulus and Surface Hardness. J Oral Rehabil 2001, 28, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schricker, S.R. Composite Resin Polymerization and Relevant Parameters. In Orthodontic Applications of Biomaterials; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 153–170 ISBN 978-0-08-100383-1.

- Cramer, N.B.; Couch, C.L.; Schreck, K.M.; Carioscia, J.A.; Boulden, J.E.; Stansbury, J.W.; Bowman, C.N. Investigation of Thiol-Ene and Thiol-Ene–Methacrylate Based Resins as Dental Restorative Materials. Dental Materials 2010, 26, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletin, A.; Knežević, M.J.; Koprivica, D.Đ.; Veljović, T.; Puškar, T.; Milekić, B.; Ristić, I. Dental Resin-Based Luting Materials—Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, N.B.; Stansbury, J.W.; Bowman, C.N. Recent Advances and Developments in Composite Dental Restorative Materials. J Dent Res 2011, 90, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Shin, S.-M.; Kim, H.-J.; Paek, J.; Kim, S.-J.; Yoon, T.H.; Kim, S.-Y. Influence of Glass-Based Dental Ceramic Type and Thickness with Identical Shade on the Light Transmittance and the Degree of Conversion of Resin Cement. Int J Oral Sci 2018, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.-H.; Singh, R.K.; Lee, H.-H. A Comprehensive Review: Physical, Mechanical, and Tribological Characterization of Dental Resin Composite Materials. Tribology International 2023, 179, 108102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Kenneth J. Anusavice, Chiayi Shen, H. Ralph Rawls-Phillips' Science of Dental Materials (11th Edition). ISBN: 9781455748136.

- Ferrari, M.; Carvalho, C.A.; Goracci, C.; Antoniolli, F.; Mazzoni, A.; Mazzotti, G.; Cadenaro, M.; Breschi, L. Influence of Luting Material Filler Content on Post Cementation. J Dent Res 2009, 88, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peutzfeldt, A. Dual-Cure Resin Ceme: In Vitro Wear and Effect of Quantity of Remaining Double Bonds, Filler Volume, and Light Curing. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 1995, 53, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtos, G.; Baldea, B.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, L.; Moldovan, M.; Prejmerean, C.; Nica, L. Influence of Inorganic Filler Content on the Radiopacity of Dental Resin Cements. Dent. Mater. J. 2012, 31, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Habib, E.; Zhu, X.X. Application of Close-Packed Structures in Dental Resin Composites. Dental Materials 2017, 33, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Habib, E.; Zhu, X.X. Evaluation of the Filler Packing Structures in Dental Resin Composites: From Theory to Practice. Dental Materials 2018, 34, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto, Y.; Kitagawa, T.; Aida, M.; Nishiyama, N. Experimental and Computational Approach for Evaluating the Mechanical Characteristics of Dental Composite Resins with Various Filler Sizes. Acta Biomaterialia 2006, 2, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masouras, K.; Silikas, N.; Watts, D.C. Correlation of Filler Content and Elastic Properties of Resin-Composites. Dental Materials 2008, 24, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, M.; Fukushima, T.; Horibe, T.; Watanabe, T. [Effect of filler system on the mechanical properties of light-cured composite resins. II. Mechanical properties of visible light-cured composite resins with binary filler system]. Shika Zairyo Kikai 1989, 8, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, B.-S.; Ferracane, J.L.; Condon, J.R.; Adey, J.D. Effect of Filler Fraction and Filler Surface Treatment on Wear of Microfilled Composites. Dental Materials 2002, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, B.R.; Jaarda, M.; Wang, R. -F. Filler Particle Size and Composite Resin Classification Systems. J of Oral Rehabilitation 1992, 19, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, T.G.; Pereira, S.G.; Kalachandra, S. Effect of Treated Filler Loading on the Photopolymerization Inhibition and Shrinkage of a Dimethacrylate Matrix. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2008, 19, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, F.; Kawano, Y.; Braga, R.R. Contraction Stress Related to Composite Inorganic Content. Dental Materials 2010, 26, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sümer, E.; Değer, Y. Contemporary Permanent Luting Agents Used in Dentistry: A Literature Review. Int Dent Res 2011, 1, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, D.; Laurell, L. Occlusal Force Pattern during Chewing and Biting in Dentitions Restored with Fixed Bridges of Cross-arch Extension: II. Unilateral Posterior Two-unit Cantilevers. J of Oral Rehabilitation 1986, 13, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, R.A.; Yang, H.J.; Chaubal, T.V.; Dharmadhikari, S.; Abdulla, A.M.; Arora, S.; Rawal, S.; Kesharwani, P. Review on Synthesis, Properties and Multifarious Therapeutic Applications of Nanostructured Zirconia in Dentistry. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 12773–12793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piconi, C.; Maccauro, G. Zirconia as a Ceramic Biomaterial. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabane, A.V.; Patil, R.V.; Sardar, S.S.; Jadhav, R.D.; Patil, A.A.; Sardar, C.S. In Vitro Comparative Evaluation of Bond Strength of CAD/CAM Monolithic Zirconia Copings Influenced by Luting Agents and Finish Line Design. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice 2022, 23, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhani, T.; Latif, M.; Ahmad, I.; Rakha, S.A.; Ali, N.; Khurram, A.A. Mechanical Performance of Epoxy Matrix Hybrid Nanocomposites Containing Carbon Nanotubes and Nanodiamonds. Materials & Design 2015, 87, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Lim, D.-P.; Lim, D.-S. Tribological Behavior of PTFE Nanocomposite Films Reinforced with Carbon Nanoparticles. Composites Part B: Engineering 2007, 38, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Tiehu, L.; Zhao, T.K.; Khurram, A.A.; Khan, I.; Ullah, A.; Hayat, A.; Lone, A.L.; Ali, F.; Iqbal, S. Comparative Study of the Ball Milling and Acid Treatment of Functionalized Nanodiamond Composites. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2018, 73, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Khurram, A.A.; Tiehu, L.; Zhao, T.K.; Xiong, C.; Ali, Z.; Ali, N.; Ullah, A. Reinforcement Effect of Acid Modified Nanodiamond in Epoxy Matrix for Enhanced Mechanical and Electromagnetic Properties. Diamond and Related Materials 2017, 78, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batul, R.; Makandar, S.D.; Nawi, M.A.B.A.; Basheer, S.N.; Albar, N.H.; Assiry, A.A.; Luke, A.M.; Karobari, M.I. Comparative Evaluation of Microhardness,Water Sorption and Solubility of Biodentin and Nano-Zirconia-Modified Biodentin and FTIR Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neitzel, I.; Mochalin, V.; Bares, J.A.; Carpick, R.W.; Erdemir, A.; Gogotsi, Y. Tribological Properties of Nanodiamond-Epoxy Composites. Tribol Lett 2012, 47, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.H.; Lepe, X.; Zhang, H.; Wataha, J.C. Retention of Metal-Ceramic Crowns With Contemporary Dental Cements. The Journal of the American Dental Association 2009, 140, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savvides, N.; Bell, T.J. Microhardness and Young’s Modulus of Diamond and Diamondlike Carbon Films. Journal of Applied Physics 1992, 72, 2791–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatyrenko, S.; Kryshtal, A. Thermal Expansion Coefficients of Ag, Cu and Diamond Nanoparticles: In Situ TEM Diffraction and EELS Measurements. Materials Characterization 2021, 178, 111296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levartovsky, S.; Kuyinu, E.; Georgescu, M.; Goldstein, G.R. A Comparison of the Diametral Tensile Strength, the Flexural Strength, and the Compressive Strength of Two New Core Materials to a Silver Alloy-Reinforced Glass-Inomer Material. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1994, 72, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.C.; Kaneko, L.M.; Donovan, T.E.; White, S.N. Diametral and Compressive Strength of Dental Core Materials. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1999, 82, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygili, G.; Mahmali, S.M. Comparative Study of the Physical Properties of Core Materials. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2002, 22, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El-Kemary, B.M.; El-Borady, O.M.; Abdel Gaber, S.A.; Beltagy, T.M. Role of nano-zirconia in the Mechanical Properties Improvement of Resin Cement Used for Tooth Fragment Reattachment. Polymer Composites 2021, 42, 3307–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beketova, A.; Tzanakakis, E.-G.C.; Vouvoudi, E.; Anastasiadis, K.; Rigos, A.E.; Pandoleon, P.; Bikiaris, D.; Tzoutzas, I.G.; Kontonasaki, E. Zirconia Nanoparticles as Reinforcing Agents for Contemporary Dental Luting Cements: Physicochemical Properties and Shear Bond Strength to Monolithic Zirconia. IJMS 2023, 24, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundie, F.; Azhari, C.H. Effects of Filler Size on the Mechanical Properties of Polymer-Filled Dental Composites: A Review of Recent Developments. JPS 2018, 29, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, S.; Takamizawa, T.; Tsujimoto, A.; Moritake, N.; Ishii, R.; Barkmeier, W.W.; Latta, M.A.; Miyazaki, M. Influence of Different Curing Modes on Flexural Properties, Fracture Toughness, and Wear Behavior of Dual-Cure Provisional Resin-Based Composites. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiremath, G.; Horati, P.; Naik, B. Evaluation and Comparison of Flexural Strength of Cention N with Resin-Modified Glass-Ionomer Cement and Composite - An in Vitro Study. J Conserv Dent 2022, 25, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja Awang, R.A.; Islam, M.S.; Jamayet, N.; Ismail, N.H. Flexural Strength and Viscosity of Dental Luting Composite Reinforced with Zirconia and Alumina. Bangladesh J Med Sci 2024, 23, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.W.; Sidhu, S.K.; Czarnecka, B. Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of Glass-Ionomer Dental Cements: A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geramipanah, F. Comparison of Flexural Strength of Resin Cements After Storing in Different Media and Bleaching Agents. European Journal of Prosthodontics and Restorative Dentistry 2015, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, A.; Oznurhan, F.; Candan, M. In Vitro Comparison of Surface Roughness, Flexural, and Microtensile Strength of Various Glass-Ionomer-Based Materials and a New Alkasite Restorative Material. Polymers 2023, 15, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchanadikar, N.T.; Kunte, S.S.; Khare, M.D. Comparison of Bond Strength, Flexural Strength, and Hardness of Conventional Composites and Self-Adhesive Composites: An in Vitro Study. IJPCDR 2016, 3, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.; Rahoma, A.; Al-Thobity, A.M.; ArRejaie, A. Influence of Incorporation of ZrO2 Nanoparticles on the Repair Strength of Polymethyl Methacrylate Denture Bases. IJN 2016, Volume 11, 5633–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, N.M.; Badawi, M.F.; Fatah, A.A. EFFECT OF REINFORCEMENT OF HIGH-IMPACT ACRYLIC RESIN WITH ZIRCONIA ON SOME PHYSICAL AND MECHANICAL PROPERTIES. Archives of Oral Research 2008, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushowmi, T.H.; AlZaher, Z.A.; Almaskin, D.F.; Qaw, M.S.; Abualsaud, R.; Akhtar, S.; Al-Thobity, A.M.; Al-Harbi, F.A.; Gad, M.M.; Baba, N.Z. Comparative Effect of Glass Fiber and Nano-Filler Addition on Denture Repair Strength. Journal of Prosthodontics 2020, 29, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouda, S.M.; Gad, M.M.; Ellakany, P.; A. Al Ghamdi, M.; Khan, S.Q.; Akhtar, S.; Ali, M.S.; Al-Harbi, F.A. Flexural Properties, Impact Strength, and Hardness of Nanodiamond-Modified PMMA Denture Base Resin. International Journal of Biomaterials 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Harbi, F.A.; Abdel-Halim, M.S.; Gad, M.M.; Fouda, S.M.; Baba, N.Z.; AlRumaih, H.S.; Akhtar, S. Effect of Nanodiamond Addition on Flexural Strength, Impact Strength, and Surface Roughness of PMMA Denture Base. Journal of Prosthodontics 2019, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).