1. Introduction

Parabens are used to extend the shelf life of processed foods, medicines, cosmetics, and personal care products [

1,

2], with annual consumption by the industry of more than 8,000 tons [

3,

4]. These compounds are short alkyl chain esters of para-hydroxybenzoic acid, and the most commonly used as preservatives are those with open and linear chains, such as methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben [

5]. Among these compounds, ethylparaben (EtP) is the most widely used industrially because it has a broad antimicrobial spectrum against fungi and bacteria, moderate solubility, good stability at different temperatures and pHs [

6], and low acute toxicity to humans [

5,

7,

8], as well as being odorless, colorless, and low volatility [

7].

However, EtP may contaminate surface water, groundwater, wastewater, drinking water, sludge, and soil [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Therefore, this compound is classified as an emerging pollutant, since there is no regulation controlling its release into different environmental matrices, in part, because its adverse effects on different ecosystems are still relatively uncharacterized [

5,

6,

13,

14]. Furthermore, EtP is classified as a pseudo-persistent compound because its degradation in water and soil is relatively fast (on average, fifteen days). However, its release into the environment is uninterrupted [

5].

In water resources, the occurrence of EtP is mainly due to the inefficiency of conventional wastewater treatments to entirely remove it from domestic and industrial effluents, resulting in rivers and lakes at concentrations in the ng.L

-1 range [

7,

12,

15]. Studies with aquatic organisms have shown that EtP can cause neurobehavioral changes, oxidative stress, and bioaccumulation in fish, as well as reduced heart rate, reduced blood circulation, pericardial edema, deformation of the notochord, and yolk sac in fry [

8,

16]. In addition, EtP has shown the potential to cause cardiac and neurobehavioral changes, immobilization, and death in microcrustaceans, estrogenic effects in copepods, and reduced luminescence in bacteria [

17,

18,

19]. In vertebrate systems, this compound is genotoxic, causing shortening of telomeres, induction of micronuclei, and is associated with an increased risk of cancers, especially estrogen-sensitive cancer lines [

20,

21,

22].

In soil, EtP contamination occurs mainly through the incorporation of domestic sewage sludge into agricultural soils for fertilization purposes, the irrigation of crop areas with contaminated water, and leaching from landfills and planting soils [

5,

23], being found in these matrices in concentrations ranging from ng to µg.L

-1 [

7,

24,

25]. Agricultural crop species can absorb parabens and accumulate in their tissues [

26,

27,

28]. Bacterial pathogen contamination of leafy green crops is a serious concern and is often a result of either livestock or human waste contamination placed on the crop fields [

29,

30,

31,

32]. To mitigate bacterial contamination of leafy greens, one concept (concept only) is to use parabens as part of an integrated pathogen management plan [

33,

34]. Thus, potential contamination/application from both types of sources requires an assessment of the ecotoxicological impacts of EtP on crops and keystone species of sustainably agricultural landscapes.

Daucus carota L. (carrot),

Lycopersicum esculentum (tomato), and

Cucumis sativus L. (cucumber) are vegetables widely used in ecotoxicological analyses of organic contaminants, based mainly on physiological and biochemical parameters [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. These species are recommended by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) [

40] and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [

41]. The roots of

Allium cepa L. (onion) bulbs have been used for five decades in ecotoxicological assessments of environmental contaminants worldwide [

42,

43,

44,

45], using physiological, cytological, and biochemical parameters. The results obtained through this test system are similar to those obtained through other biomodels, such as other plants, animals, and cell cultures [

39,

42,

43,

44,

46,

47,

48,

49].

Eisenia fetida Sav. earthworms are an important edaphic representative because they are essential in the terrestrial food chain and are widely used in ecotoxicological tests of organic and inorganic contaminants present in the soil [

38,

50,

51]. These animals are susceptible to chemical and physical changes and may exhibit behavioral, physiological, and biochemical changes when exposed to contaminated environments, detecting soil pollution early on [

52,

53].

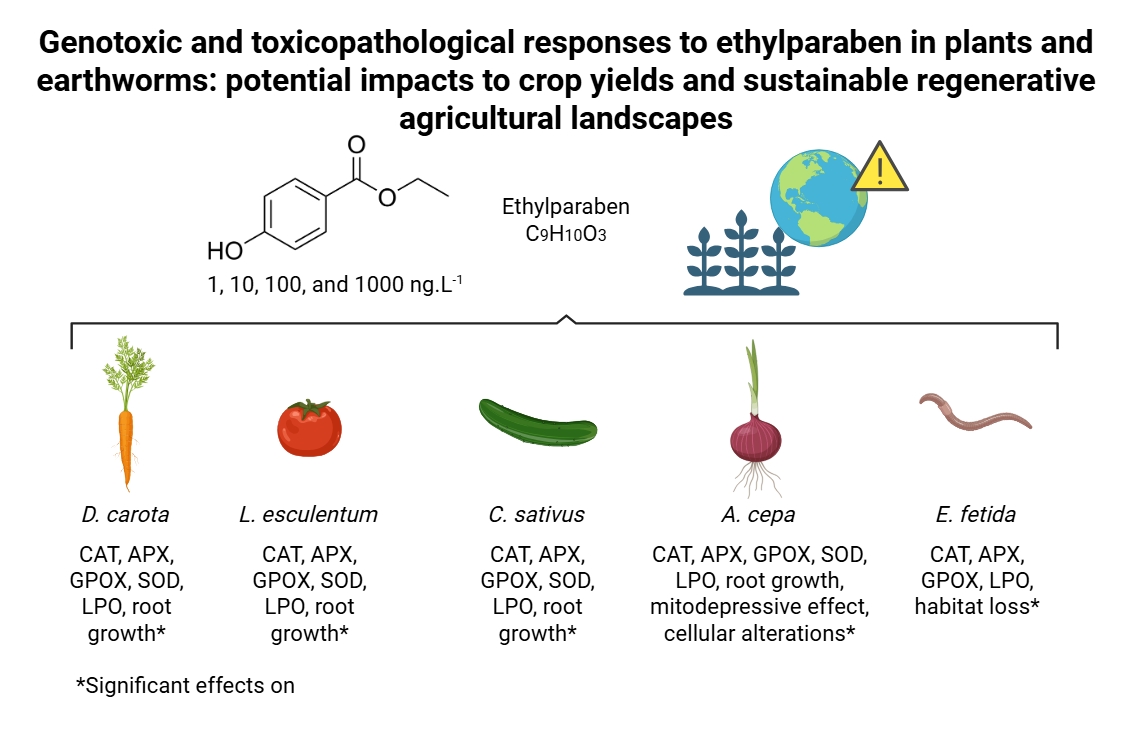

In this study, the systemic and cellular toxicity of EtP was evaluated at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1 in D. carota, L. esculentum, C. sativus, and A. cepa, based on physiological, cytogenetic, and biochemical markers, and in E. fetida, through behavioral and biochemical markers analysis. This study is expected to advance the understanding of the ecotoxicity of EtP in soil organisms, as well as encourage the establishment of regulations to control the release of parabens into the environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtaining EtP and Defining and Preparing Concentrations for Study

The ethylparaben (ethyl para-hydroxybenzoate) – CAS 120-47-8, molecular weight 166.17 g.mol-1 and log Kow 2.47 – was obtained in analytical grade from Sigma-Aldrich®, as were the other reagents used.

Identification and quantification assessments carried out in different countries have shown that EtP has been found in soils at concentrations of 1 ng.L

-1 to 170 µg.L

-1 [

5,

7], and in wastewater and domestic sewage sludge at concentrations of 195.3 to 250 µg.L

-1 [

24,

25]. Although the concentrations mentioned are mainly in the µg range, in this study, we chose to evaluate concentrations in ng (1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L

-1) in order to get as close as possible to the real environmental concentrations since EtP is pseudo-persistent in water and soil.

EtP concentrations were prepared in aqueous media using Tween® 80 as a solubilizer (at the same mass concentration as EtP).

2.2. EtP Stability Analysis in Aqueous Media

A 0.03 g.L

-1 EtP stock solution was prepared to assess the stability of this compound in aqueous media for 7 days without light (Equation 1). The analyses were carried out using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at 255 nm, and the results were presented in percentages.

where S is the stability, As the absorbance of the sample, and A0 the initial absorbance on day 0.

2.3. Plant Assays

2.3.1. Evaluation of Phytotoxic Potential in Seeds of D. carota, L. esculentum, and C. sativus

The OECD [

41] protocol was used to analyze the phytotoxic potential in seeds, and the plants considered were

D. carota,

L. esculentum, and

C. sativus. The seeds of these species, free of pesticides and non-transgenic, were purchased from an agricultural supply store. According to the packaging information, the seeds had a germination rate greater than 98% and purity between 99% and 100%. Seeds from the same batch were used for all analyses. Seeds from each plant were distributed in Petri dishes lined with filter paper and previously sterilized. 20 seeds were used per dish, and each concentration was evaluated in quintuplicate. The filter paper was moistened in each dish with up to 1.5 mL of the treatment solution (concentration). The dishes were wrapped in plastic film and placed in a Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) incubator at 25 °C, without light, for seven days. Distilled water was used as a control.

The germination percentage was calculated according to Equation 2, and a seed was considered germinated after radicle emergence.

where G is the germination, SG the number of seeds germinated, and TS the total number of seeds used.

After 7 days, the rootlets were measured with a digital caliper and the Relative Growth Index was calculated (Equation 3).

where RGI is the Relative Growth Index, RLI the average length of the roots exposed to the treatment, and RLC the average length of the control roots. According to Biruk et al. [

54], an RGI between 0.9 and 1.2 indicates that the treatment did not affect root growth, an RGI below 0.9 indicates inhibition of root elongation, and an RGI greater than 1.2 (RGI>1.2) indicates stimulation of root growth.

The Germination Index (GI) was calculated according to Equation 4. According to Mañas and Heras [

55], a GI equal to or less than 50% characterizes high danger to the plant with acute lethal potential, a GI between 50 and 80% characterizes moderate danger, and a GI greater than or equal to 80% characterizes low danger.

where GI is the Germination Index, RLI the average length of roots exposed to treatment, RLC the average length of roots in the control, GSI the number of seeds germinated under exposure to treatment, and GSC the number of seeds germinated in the control.

2.3.2. Analysis of Phytotoxic, Cytotoxic, and Genotoxic Potential in Roots of A. cepa bulbs

The analyses with

A. cepa bulb roots were performed according to Fiskesjö [

56] with modifications by Nascimento et al. [

38] and Filipi et al. [

57]. The onion bulbs were purchased from an organic garden. Before starting the experiments, the cataphylls and dry roots were removed from the onions and washed in distilled running water. The clean onions were placed in bottles with the treatment solutions (concentrations) in which the root growth zone was submerged in the solution, then placed in a BOD incubator for seven days without light. The treatment solutions were prepared and changed daily. Distilled water was used as a control, and each concentration was evaluated in quintuplicate.

After 7 days of incubation in the BOD, the length of five roots from each onion was measured with a digital caliper, and the Average Root Length (ARL) was calculated for each concentration according to Equation 5 to determine the phytotoxic potential.

In addition, roots were collected from each bulb and fixed in Carnoy’s solution 3:1 for 24 hours. Slides were then prepared from the meristematic regions of these roots, which were analyzed under an optical microscope at 40x magnification.

To evaluate cytotoxic potential, 2.000 cells from each onion were analyzed, totaling 10.000 cells per concentration analyzed, and the Mitotic Index (MI) was calculated (Equation 6). To evaluate genotoxicity, 200 cells from each onion were analyzed, totaling 2.000 cells analyzed per concentration, and the Cellular Alteration Index (CAI) was calculated (Equation 7). The cellular alterations considered in the analyses were: polyploidy, micronuclei, chromosomal abnormalities in different phases of mitosis, and chromosomal breakage.

where MI is the Mitotic Index, DC the dividing cells, TC the total number of dividing cells, CAI the Cell Alteration Index, and AC the altered cells.

2.4. E. fetida Assays

2.4.1. Obtaining the Earthworms, Constitution of the Artificial Soil, and Number of Replicates for Each Treatment

The E. fetida worms were purchased from the worm farm at the Federal Technological University of Paraná, Francisco Beltrão Campus, Paraná, Brazil. The worms used in the experiments were two months old, had formed clitellums, and weighed between 500 and 600 mg.

Artificial soil (SAT) with the following composition was used for the escape and mortality tests: 70% dry-sifted fine sand, 20% kaolin powder, and 10% powdered coconut fiber. This soil composition is recommended by the OECD [

58] for ecotoxicological studies with earthworms.

For each concentration evaluated in the escape and mortality tests, two repetitions were used, with 10 earthworms each.

2.4.2. Escape Test

The NBR ISO 17.512-1 [

59] was used to perform the escape test.

Rectangular polypropylene containers measuring 175 x 132 mm and 115 mm in height were used, with perforated lids to allow ventilation. Before conducting the tests, the polypropylene containers were divided in half with a removable plastic divider. Distilled water was used as a negative control and boric acid as a positive control (750 mg per 1 kg of soil).

For each concentration evaluated, SAT soil and distilled water or SAT soil and boric acid solution were placed on one side of the container, while SAT soil and the treatment solution (concentration) were placed on the other side. On both sides of the container, the moisture content was adjusted to 60% of the minimum water-holding capacity of the soil with the solution of interest.

After preparing each container, the plastic divider was removed and 10 earthworms were placed on the dividing line between the two sides. The containers with the worms were then covered and placed in the dark for 48 hours. After this time, the plastic dividers were reinserted into each container, separating the control soil from the treated soil, and the number of earthworms on each side was counted. When replacing the divider, if any animal was cut in half, the side of the container where most of the body remained was considered, according to Candello et al. [

60].

A double negative control was performed, in which both sides of the containers contained SAT soil and distilled water. This double negative control validates the escape test, since the worms are expected to distribute themselves evenly on both sides of the containers due to the absence of contaminants. In the escape test, in each container, the number of dead worms in each container after 48 hours of exposure to the analyzed concentrations is expected to be less than 10%.

The data were analyzed as a percentage of escape, according to Equation 8.

where % is the percentage of escape, Nc the number of earthworms found in section B (control soil), Nt the number of earthworms found in section A (test soil), and N the total number of earthworms (sum of the two repetitions).

Based on the results obtained, if the animals preferred the soil treated with the concentrations of interest, the response is negative for escape. Soil with the evaluated concentrations is considered repellent when more than 80% of the earthworms preferred the control soil.

2.4.3. Mortality Test

To perform the mortality test on E.

fetida, NBR 15537 [

61] was used, with modifications by Filipi et al. [

57] and Santo et al. [

49].

For this test, rectangular polypropylene containers measuring 175 x 132 mm and 115 mm high were used, in which 600 g of SAT plus 8 g of cattle manure and distilled water were placed up to 60% of the soil’s maximum retention capacity. 10 earthworms were placed in each plastic container. The containers were then covered with plastic lids with perforations to allow ventilation. The covered containers were placed in a BOD incubator for 7 days to acclimatize the earthworms. The BOD was set at 22 ± 2 °C, with 16 hours of light and 8 hours of darkness.

After acclimatization, the earthworms were placed in other containers containing 600 g of SAT and 8 g of cattle manure, plus distilled water (negative control) or boric acid (positive control, 750 mg.Kg-1 of SAT), or concentrations of interest. These containers remained for 14 days in a BOD incubator with the same temperature and light/dark cycle as during the acclimatization period.

On the seventh day of incubation, the containers containing the animals were weighed, and if necessary, the soil moisture was corrected with their respective treatment solutions. On the seventh day, 8 g of manure was also added to each container. After 14 days of incubation, the number of dead earthworms in each pot was counted. To confirm the death of the earthworms, the contents of the containers were poured onto a plastic tray and a mechanical stimulus was applied to the animals.

The data was expressed as a percentage of mortality (Equation 9).

where % mortality is the percentage of mortality, nM the number of dead earthworms, and N the total number of earthworms.

2.5. Enzymatic Analysis in Seed, Bulb Roots and in E. fetida

2.5.1. Preparation of Roots and Earthworms for Enzymatic Analysis

For plant analyses, 50 mg of seed roots from each repetition and root meristems from each bulb were macerated in 1 mL of HCl (38%) and 2 mL of diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (5 mM), and then centrifuged at 4.000 rpm for 15 minutes to obtain the enzyme extracts.

For earthworms, individuals that survived the mortality test in each repetition were individually crushed and homogenized in 10 mL of balanced saline solution (LBSS), prepared according to Hendawi et al. [

62], using an Ultra-Turrax

® homogenizer at 10.000 rpm for 60 seconds. The homogenates were centrifuged at 4.000 rpm for 15 minutes to obtain the enzyme extracts.

The enzyme extracts obtained were analyzed in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to evaluate the modulation of catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), guaiacol peroxidase (GPOX), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes.

2.5.2. Enzymatic Analysis

CAT activity was analyzed based on the method described by Kraus et al. [

63], with adaptations proposed by Azevedo et al. [

64]. 2.5 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) was added to 100 µL of the enzyme extract for each sample. Then, 1 mL of 1 mM hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) was added to read the enzyme activity at 240 nm. The extinction coefficient used for the calculations was 2.8 M

−1·cm

−1, and the results were expressed in µmol·min

−1·µg

−1 of protein (Equation 10).

where U is the enzyme unit, A the measured absorbance, t the analysis time, E the extinction coefficient, Ve the enzyme volume, DF the dilution factor, and P the protein, obtained from the mass of roots used.

APX activity analysis was performed according to the method by Zhu et al. [

65]. To the enzyme extracts, 2.5 mL of sodium phosphate buffer, 500 µL of 0.25 mM ascorbic acid, and 1 mL of 1 mM hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) were added. The reading was performed at 290 nm. An extinction coefficient of 2.8 M

−1·cm

−1 was used, and the results were expressed in µmol·min

−1·µg

−1 of protein (Equation 10).

The analysis of GPOX activity was performed based on the protocol by Matsuno and Uritani [

66]. To 300 µL of the enzyme extract, 2.5 mL of sodium phosphate buffer, 250 µL of 0.1 M citric acid, and 250 µL of 0.5% guaiacol were added. Next, 250 µL of 1 mM hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) was added. The mixtures were homogenized in a vortex and incubated in an oven at 30°C for 15 minutes. After this period, the samples were cooled in an ice bath for 10 minutes, and 250 µL of 2% sodium metabisulfite was added. The reading was performed at 450 nm. The extinction coefficient used was 26.6 M

−1·cm

−1, and the results were expressed in µmol·min

−1·µg

−1 of protein (Equation 10).

The SOD assay followed the protocol by Sun et al. [

67]. Samples were prepared in duplicate: half of the extract aliquots were exposed to 80 W fluorescent light for 20 minutes, while the other half were kept in the dark. To 200 µL of each aliquot, 0.8 mL of sodium phosphate buffer, 500 µL of 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 500 µL of methionine, 500 µL of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), and 200 µL of riboflavin were added. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm, and SOD activity was expressed as U per protein (Equation 11).

where B

l is the absorbance of the blank kept in the light prepared without the enzyme extract, s

l the absorbance of the sample kept in the light, B

e the absorbance of the blank kept in the dark, and se the absorbance of the sample kept in the dark. The quotient 50 represents the amount of enzyme required to inhibit 50% of the photoreduction of NBT.

2.6. Analysis of Phenolic Content (Folin-Ciocalteu) in Roots, and Lipid Peroxidation (TBARs) in Roots and Earthworms

2.6.1. Sample Preparation

For plants, 50 mg of seed roots and bulb root meristems from each replicate were centrifuged in distilled water at 4.000 rpm for 15 minutes to obtain homogenate supernatants. For animals, surviving earthworms from the mortality test were individually ground in LBSS solution using an Ultra-Turrax® homogenizer at 10.000 rpm for 60 seconds and then centrifuged at 4.000 rpm for 15 minutes to produce homogenates.

2.6.2. Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) Assay on Roots

The Folin–Ciocalteu (FC) assay was performed following the protocol of Carmona-Hernandez et al. [

68]. To 50 µL of homogenate, 100 µL of FC reagent (0.0288 g of phosphotungstic acid and 0.0182 g of phosphomolybdic acid dissolved in 5 mL of methanol), 50 µL of ethanol, and 50 µL of distilled water were added. The mixtures were kept in the dark for 10 minutes, after which 50 µL of saturated sodium bicarbonate solution was added, and the samples were incubated in darkness for an additional 50 minutes. Absorbance was then measured spectrophotometrically at 745 nm.

2.6.3. TBARs Assay on Roots and Earthworms

Lipid peroxidation was assessed following the method of Papastergiadis et al. [

69]. To 50 µL of homogenate, 250 µL of TBARs solution (46 mM) was added, and the mixture was incubated in a water bath at 90 °C for 35 minutes. After cooling, absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 532 nm.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For the results for phytotoxicity, cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, antioxidant enzymes, phenolic content, and lipid peroxidation in plants were submitted to Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance followed by Dunn’s test (p≤0.05), since the data were considered non-normal by Lilliefors’ test. The RStudio platform was used for these analyses. In the escape test, the mean data and standard deviation of the number of worms found in each section of the pots were analyzed by Fisher’s one-tailed test, using Action 6.2 software.

3. Results

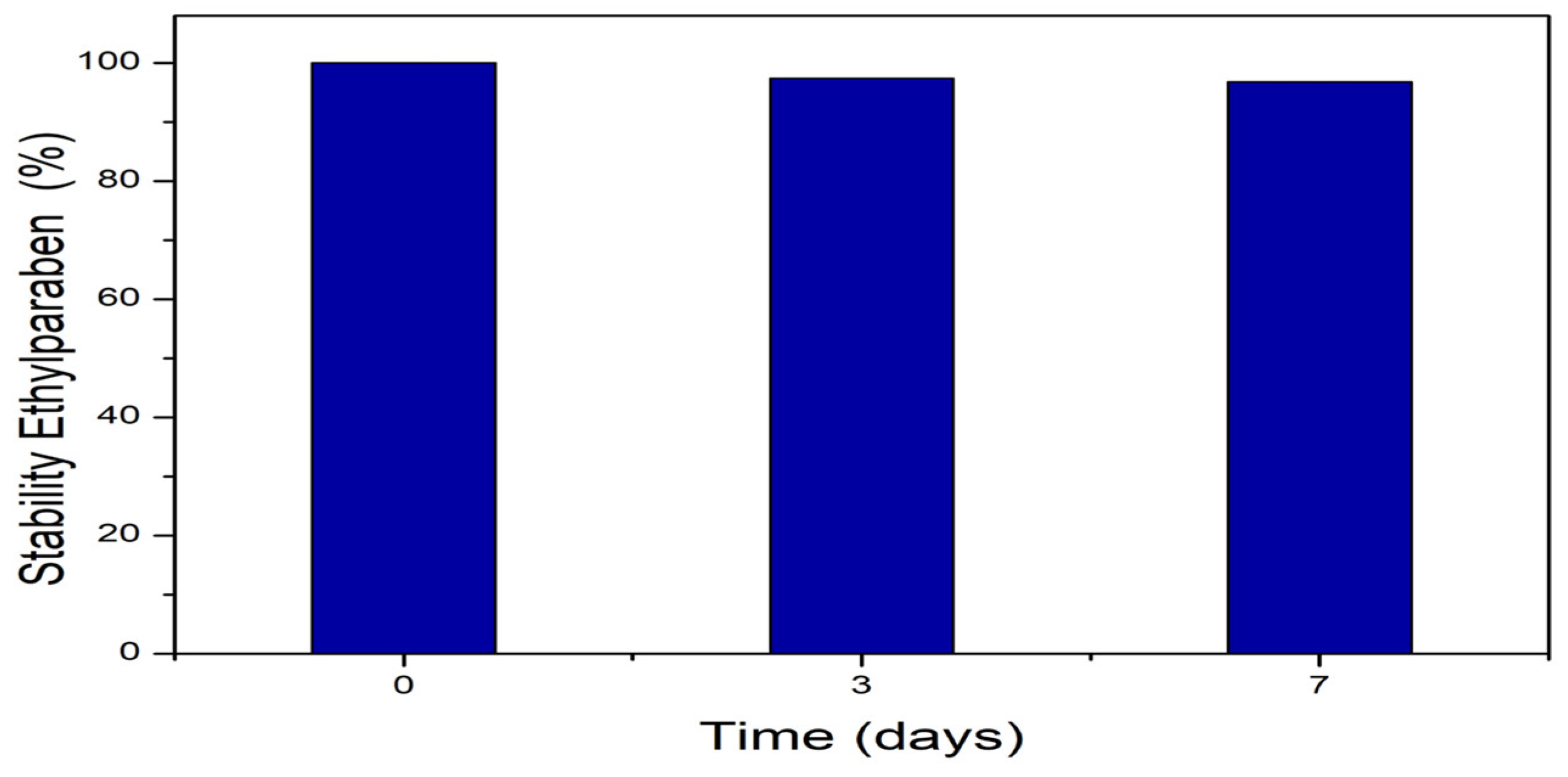

3.1. Stability in Aqueous Media

In order to provide rigor to the experimental design, the stability of EtP in aqueous media was evaluated at a concentration of 0.03 g.L

-1 (

Figure 1). It was observed that there was no change in the concentration over 7 days, demonstrating that the compound remained stable in aqueous media.

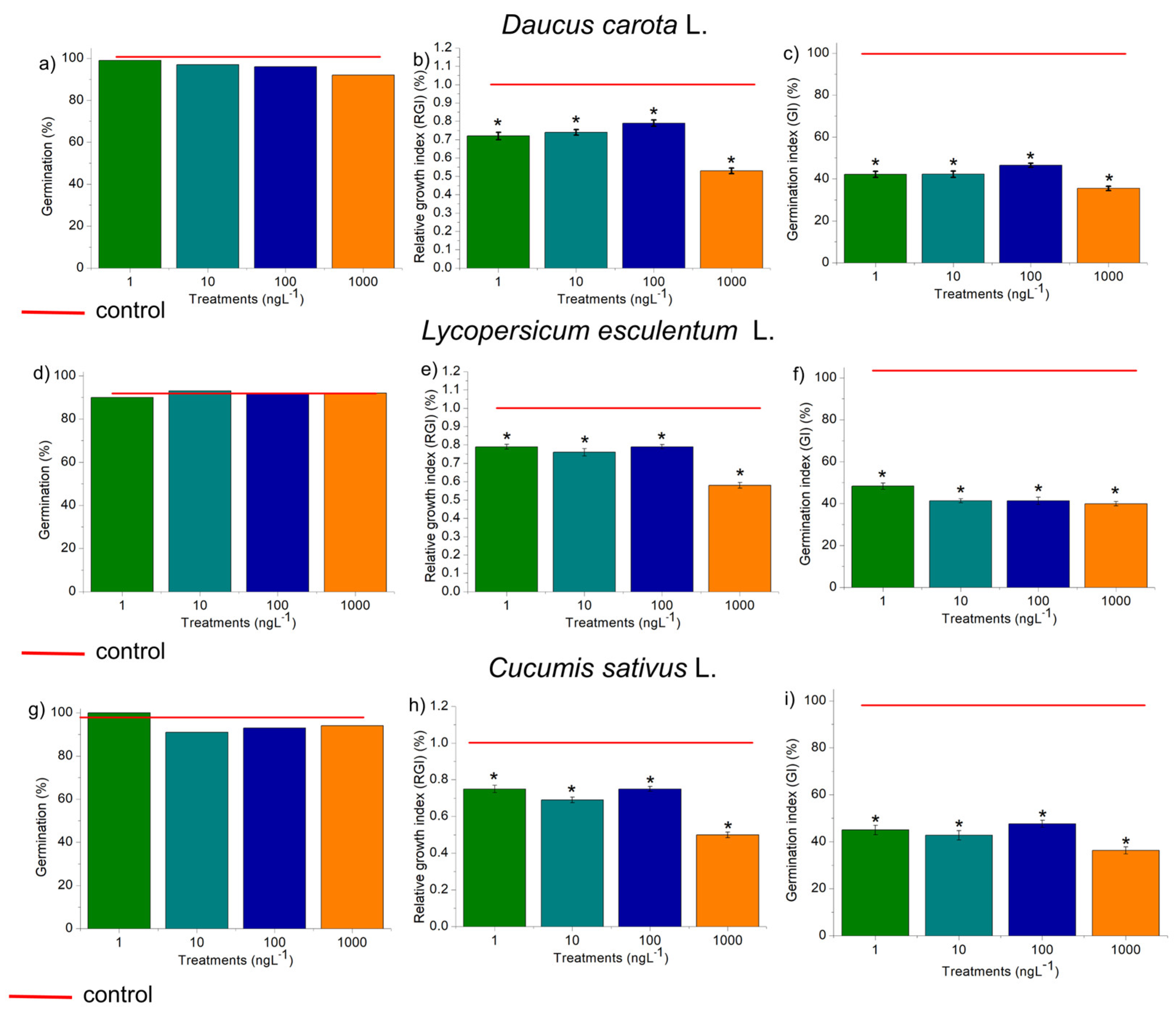

3.2. Toxicity in Seeds of D. carota, L. lycopersicim, and C. sativus and in roots of A. cepa

The four concentrations of EtP evaluated did not harm seed germination in

D. carota,

L. esculentum, and

C. sativus (

Figure 2a, d, g). However, they significantly reduced root growth in these plants, which showed Relative Growth Index (RGI) of 0.9 or less (

Figure 2b, e, h). The Germination Index (GI) is the ability of the seed to germinate, elongate rootlets, and form a healthy plant [

55]. However, the GI obtained in this study for the three vegetables was less than 50% (

Figure 2c, 2f, 2i), indicating that EtP is harmful and has the potential for acute lethality.

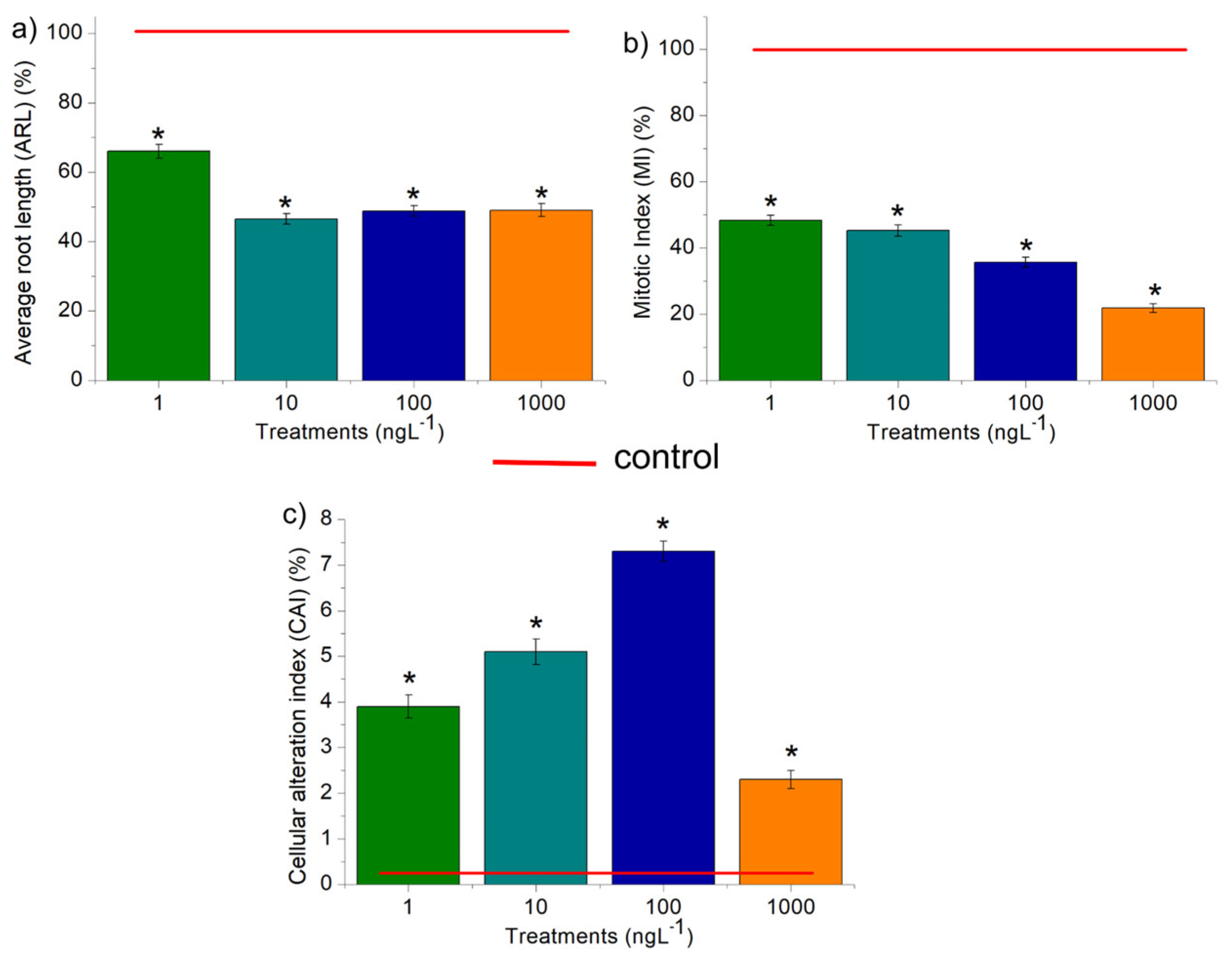

All concentrations of EtP were phytotoxic to

A. cepa bulbs as they caused a significant reduction in root growth (

Figure 3a), corroborating the results of inhibition of root elongation in

D. carota,

L. esculentum, and

C. sativus (

Figure 2b, 2e, 2h). Furthermore, EtP at all concentrations caused a significant mitodepressive effect on onion root meristems, resulting in cell division rates of less than 50% compared to the control (

Figure 3b). All concentrations induced cellular changes at a significant frequency (

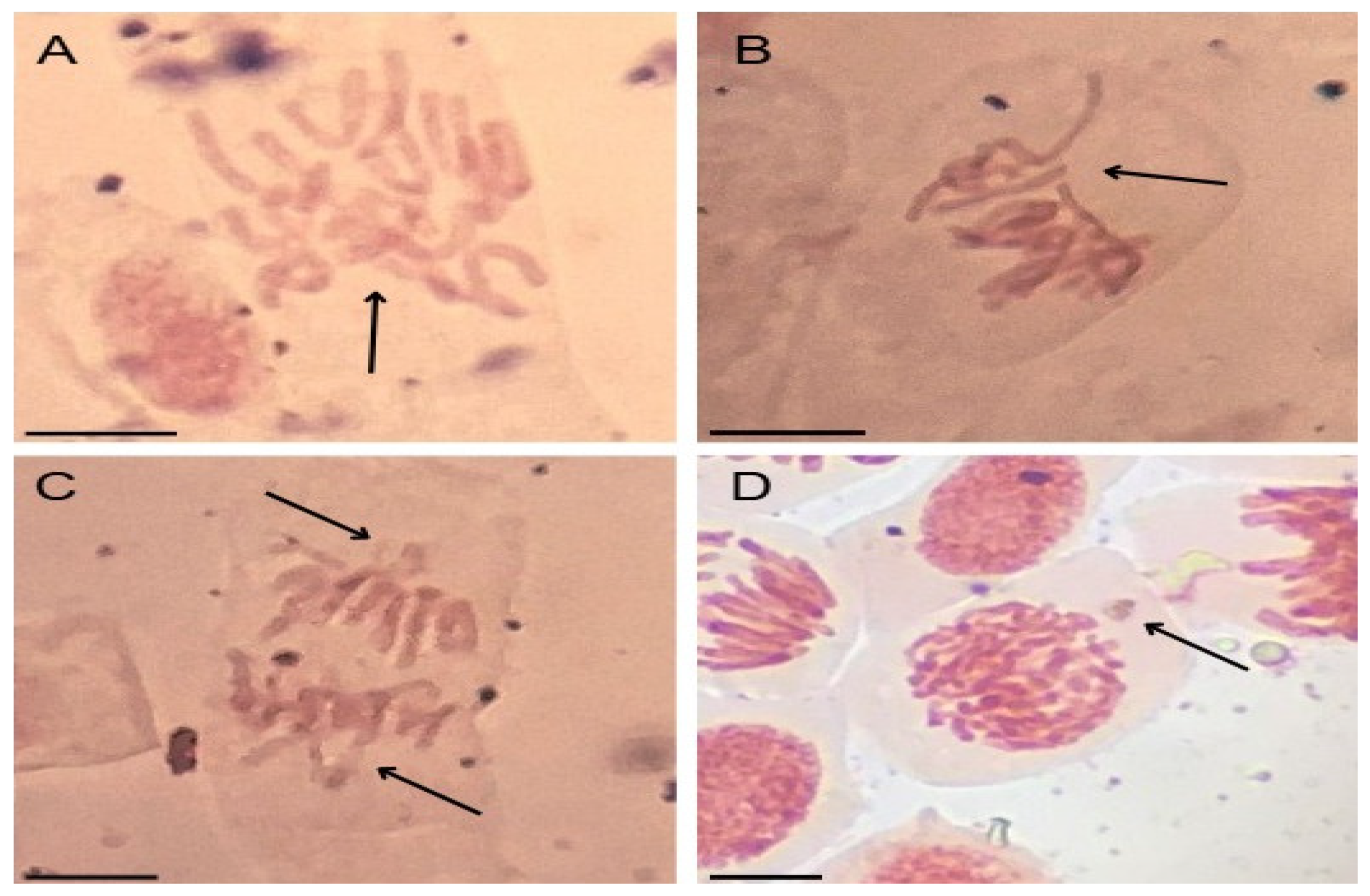

Figure 3c), showing it to be cytotoxic to the bulbs’ roots. Furthermore, the chromosomal toxicities in roots of A. cepa were observed specifically regarding chromosome disorganization in metaphase (

Figure 4a), chromosome disorganization in metaphase with chromosome loss (

Figure 4b), chromosome loss in anaphase (

Figure 4c), and micronucleus (

Figure 4d).

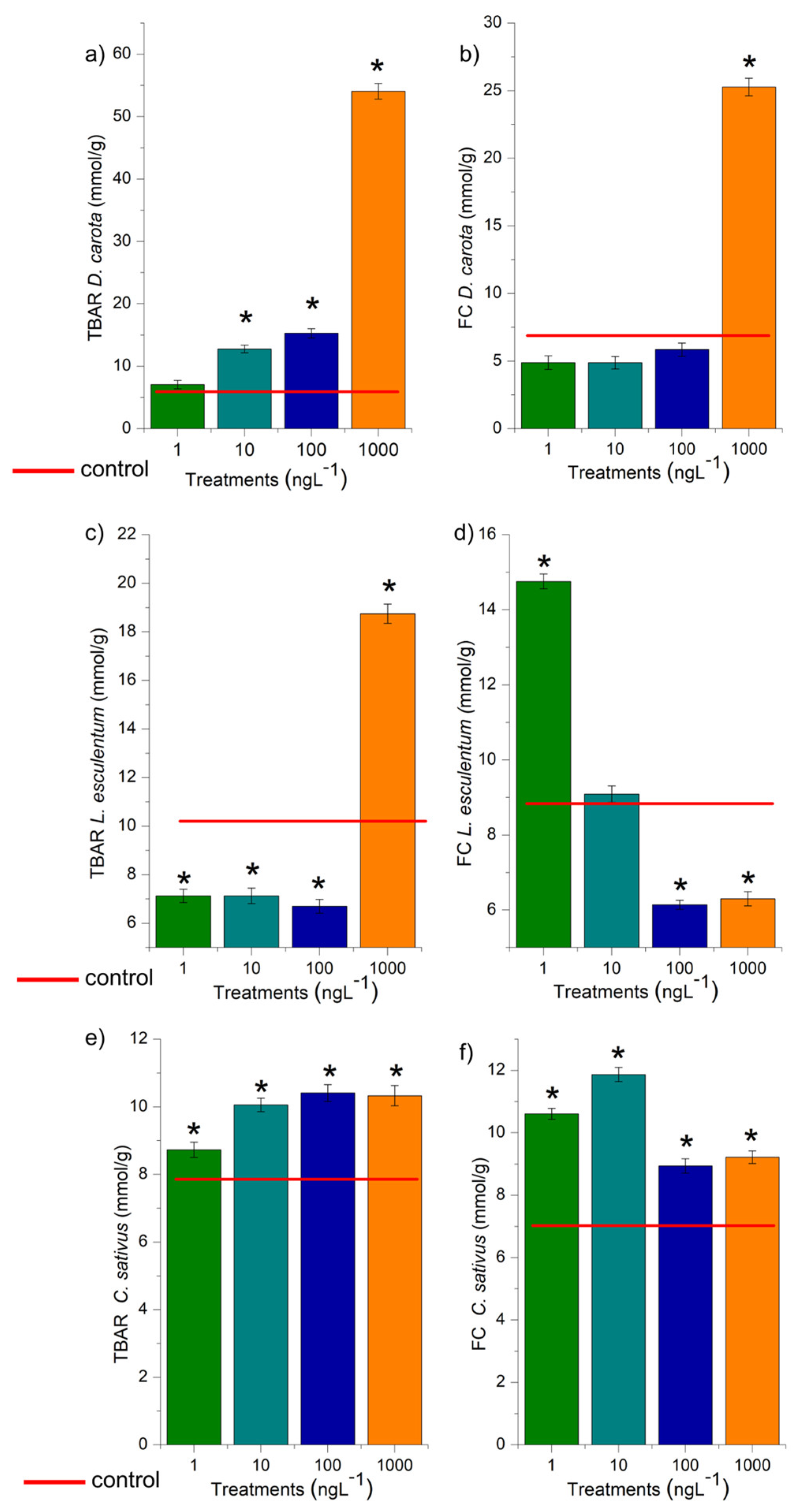

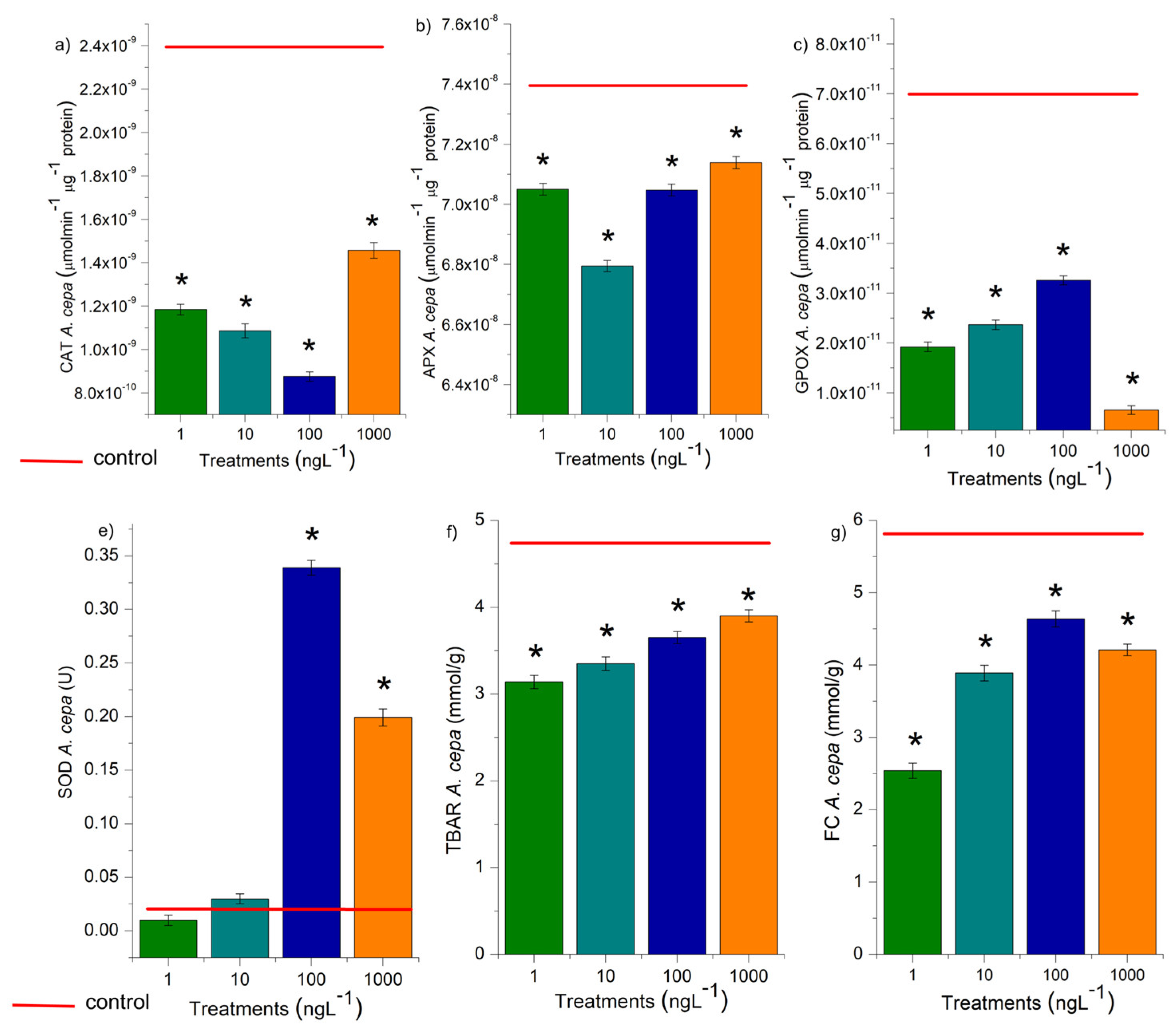

3.3. Oxidative Stress in Roots of D. carota, L. esculentum, and C. sativus, and in Roots of Bulbs of A. cepa

Enzymatic and non-enzymatic biochemical markers are essential to assess xenobiotics’ harmfulness and understand how systemic and cellular toxicity are triggered [

38]. In this study, the concentration 1000 ng.L

-1 in

D. carota (

Figure 5b), 1 ng.L

-1 in

L. esculentum (

Figure 5d), and 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L

-1 in

C. sativus (

Figure 5f), overactivated the root defense system since it significantly increased the concentration of phenolic compounds in the meristems, demonstrating that EtP caused an imbalance in cell function. However, EtP at 100 and 1000 ng.L

-1 in

L. esculentum (

Figure 5d) and at 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L

-1 in

A. cepa bulbs (

Figure 6f) caused a significant reduction in the concentration of these compounds, making cells vulnerable to stressors.

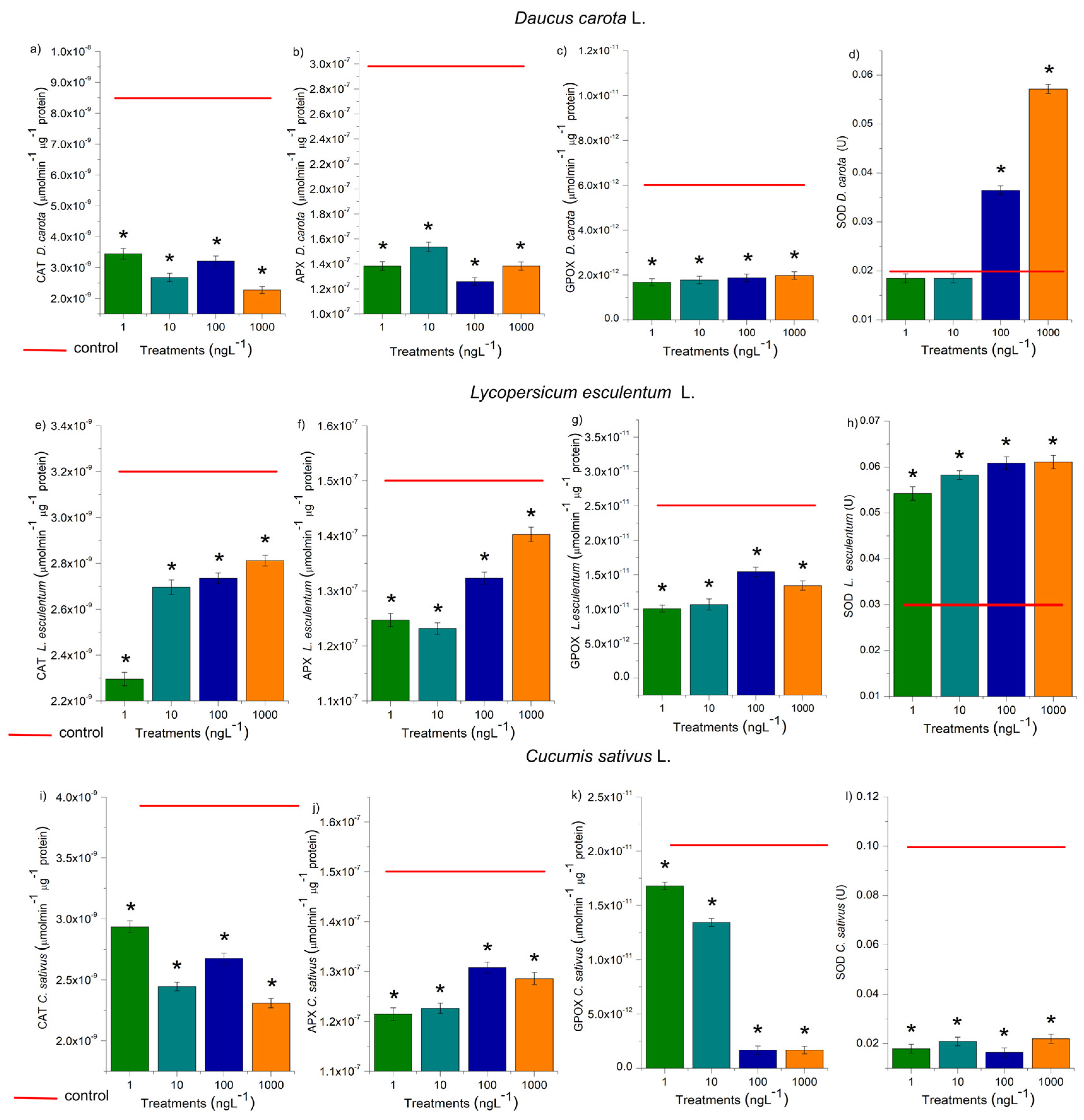

The activity of CAT, APX, SOD, and GPOX was evaluated in the radicles of

D. carota,

L. esculentum, and

C. sativus, and the roots of

A. cepa bulbs (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). These enzymes are responsible for the cell cycle’s homeostasis, which maintains cell proliferation in meristems and is essential for plant growth and development [

38]. At all EtP concentrations and in all plant species, there was a significant reduction in the activity of CAT, APX, and GPOX (

Figures 6a, b, c; 7a, b, c, e, f, g, i, j, k), potentially resulting in the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals in the cells. Furthermore, the 100 and 1000 ng.L

-1 concentrations in bulbs and carrots (

Figures 6d, 7d), as well as all concentrations in tomatoes (

Figure 7h), significantly increased SOD activity, demonstrating that EtP induced the production of superoxide radicals in tissues. In cucumber, SOD was expressly inhibited (

Figure 7l), exposing the cells to these radicals.

Based on the TBARs test (

Figure 5), the concentrations of 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L

-1 in

D. carota (

Figure 5a), 1000 ng.L

-1 in

L. esculentum (

Figure 5c), and all four concentrations in

C. sativus (

Figure 5e), caused lipid peroxidation in the roots. The compounds resulting from lipid oxidation in cell membranes are hydroxyl radicals, hydroperoxyl radicals, ketones, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids, which are highly reactive to cell proteins [

70]. Thus, the reduction in CAT, APX, and GPOX activity (

Figure 6a, 6b, 6c; 7a, 7b, 7c, 7e, 7f, 7g, 7i, 7j, 7k), as well as the lipid peroxidation observed in carrots and cucumbers (

Figure 5a, e), corroborate the high concentration of phytochemicals produced in the roots of these plants (

Figure 5b, d, f), which tried to contain the production of oxidizing radicals in the cells in order to preserve root growth, but without success (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

In this study, EtP at 1000 ng.L

-1 in

D. carota (

Figure 5b), at 1 ng.L

-1 in

L. esculentum (

Figure 5d), and at 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L

-1 in

C. sativus (

Figure 5f), overactivated the root defense system since it significantly increased the concentration of phenolic compounds in the meristems, demonstrating that this antimicrobial caused an imbalance in cell function. However, EtP at 100 and 1000 ng.L

-1 in

L. esculentum (

Figure 5d) and at 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L

-1 in

A. cepa bulbs (

Figure 6f) caused a significant reduction in the concentration of these compounds, making cells vulnerable to stressors.

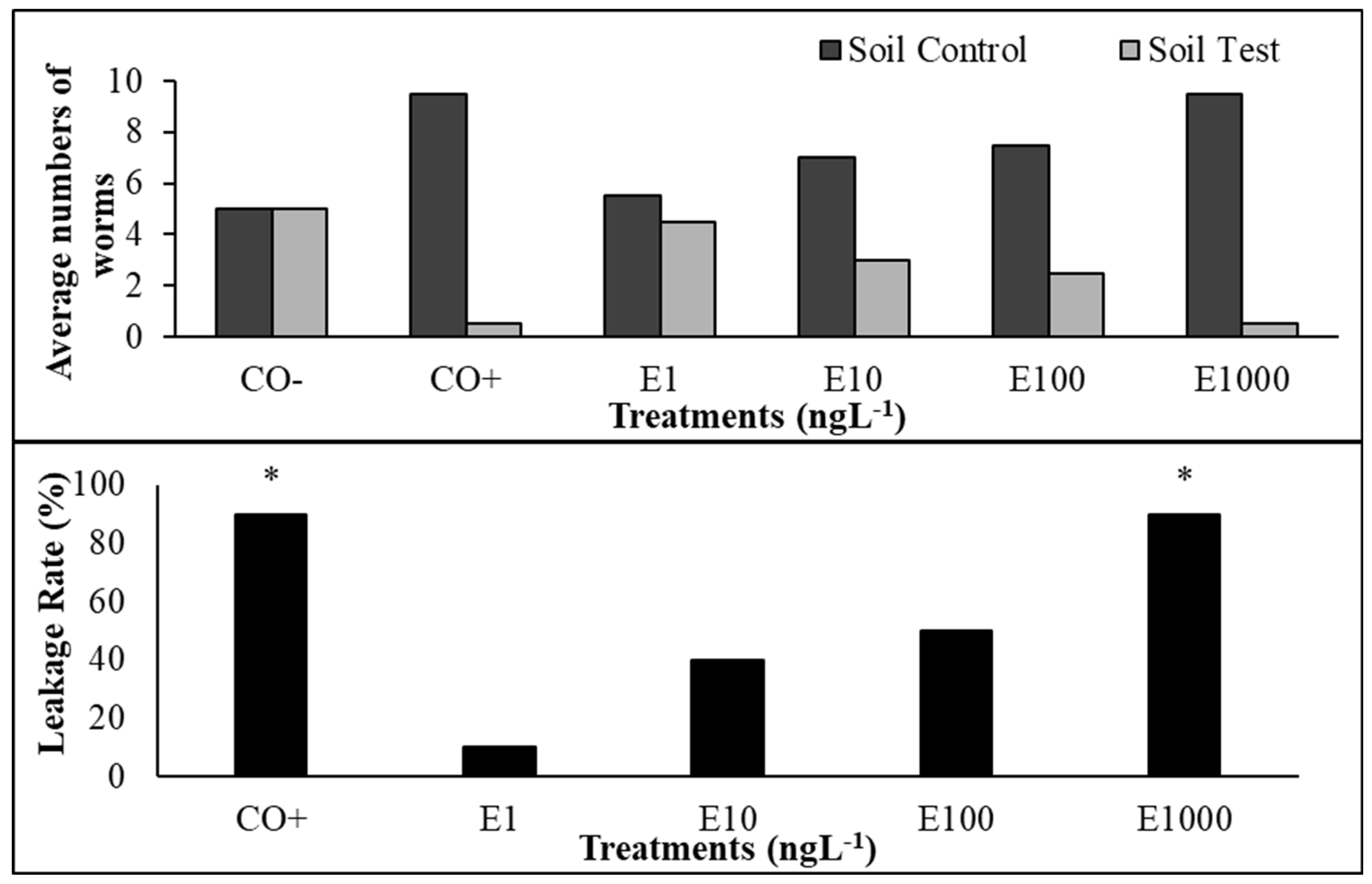

3.4. Escape and Mortality Tests, and Oxidative Stress in E. fetida Earthworms

In animals, the influence of EtP on the behavior of

E. fetida earthworms was evaluated using the escape test, which is based on the ability of these animals to perceive xenobiotics through chemoreceptor tubercles in their body, located in the region of the protostome and mouth. An increasing rate of earthworm escape was observed as the EtP concentration increased, indicating a dose-dependent pattern of aversion to EtP-treated soil (

Figure 8). The percentage of escape at 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L

-1 was 10%, 40%, 50%, and 90%, respectively.

The results of the escape test (

Figure 8) were validated by the distribution of the organisms in the control soil (

Figure 8a) since the distribution rate of the organisms remained in the desirable range, between 40% and 60%. The positive control (CO+) had 5% of the organisms in the soil test, within the range proposed by ISO 17512-1 [

71]. In addition, the results of the mortality test indicated a total absence of earthworm mortality at all the concentrations evaluated. The absence of deaths was also confirmed in the negative control, which attests to the efficiency and methodological integrity of the test.

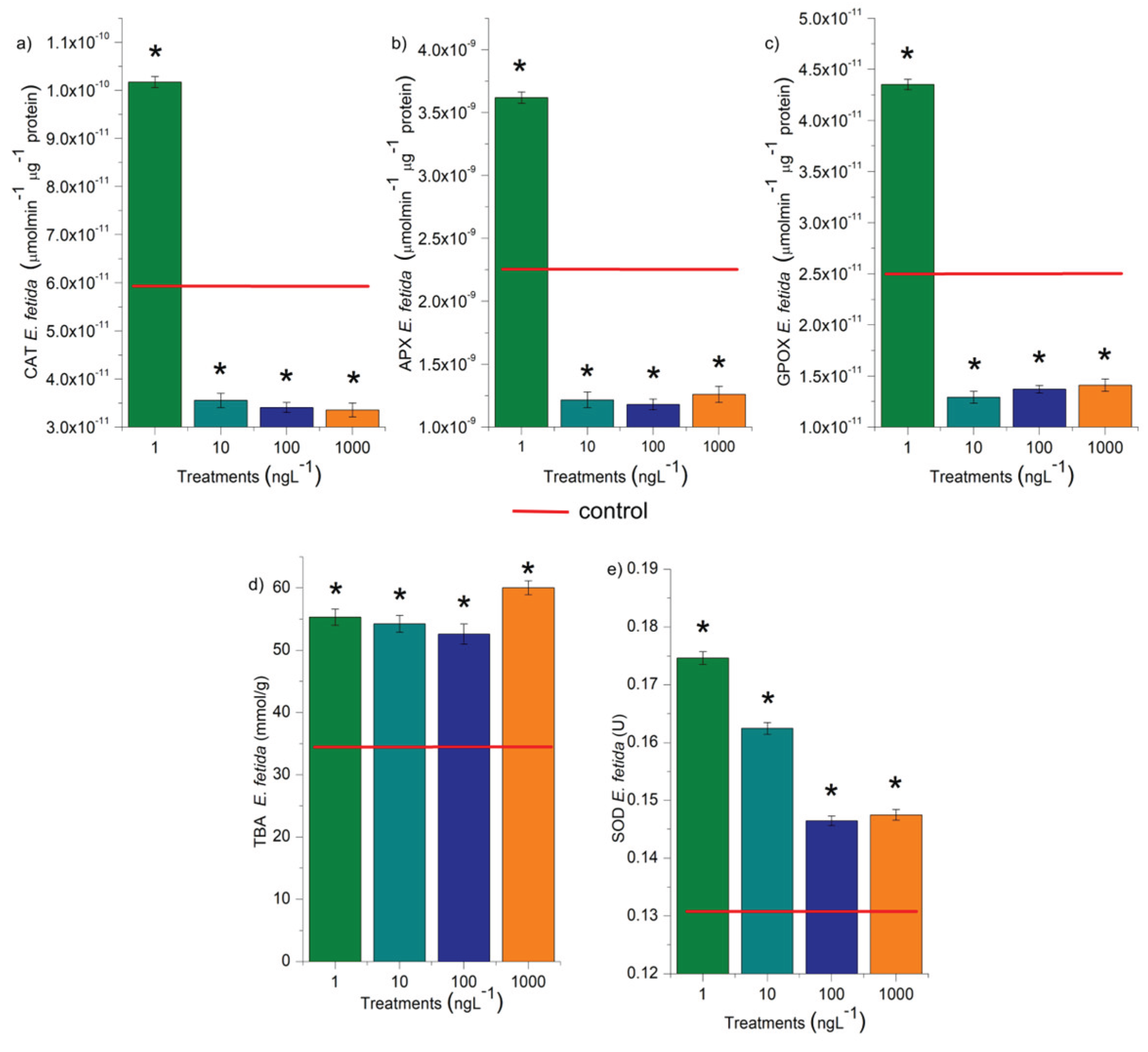

CAT, APX, GPOX, and SOD enzymes were assessed in the earthworms exposed to EtP for 14 days (

Figure 9). The results show that the concentration of 1 ng.L

-1 significantly increased the activity of these enzymes (

Figure 9a, b, c), demonstrating an increase in the production of oxidizing agents in the tissues of these animals. From 10 ng.L

-1, EtP significantly inhibited the activity of CAT, APX, and GPOX (

Figure 9a, b, c), allowing the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals in the cells. In addition, all concentrations significantly increased the concentration of SOD (

Figure 9d), which further potentiated the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide in the tissues since SOD catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. EtP, at the four concentrations evaluated, caused lipid peroxidation in the cells (

Figure 9e), further reinforcing the harmful potential of this paraben for earthworms.

4. Discussion

4.1. Histological and Chromosomal Toxicity in D. carota, L. esculentum, and C. sativus Roots and in A. cepa bulbs Roots

Although xenobiotics probably do not cause harm to seed germination, as observed for

D. carota,

L. esculentum, and

C. sativus in the present study (

Figure 2), they can be phytotoxic to the development of rootlets since the apoplastic barriers in these structures are not selective to the entry of substances that are anomalous to the metabolism of seedlings [

72]. The reduction in root growth, as observed for these three vegetables (

Figure 2), characterizes a profound sub-lethal effect on plants since it reduces the absorption of water and nutrients and can substantially compromise the development of seedlings [

73].

The reduction in cell division observed in root tips of

A. cepa (

Figure 3b) was the result of EtP inducing cell-cycle arrest, probably by disrupting cellular checkpoints in interphase, either through damage to DNA synthesis and/or protein synthesis and/or the DNA repair machinery. EtP caused mitotic indices of less than 50% in meristematic tissues – as observed for concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 ng.L

-1 (

Figure 3b). Cell division rates in meristematic cells of less than 22% – as observed for concentration 1000 ng.L

-1 (

Figure 3b) – have the potential to cause acute death/crop failure [

74,

75].

Chromosomal disorders in metaphases, such as those observed here in

A. cepa meristems (

Figure 4), are considered serious errors in the functioning of meristems since they are caused by the complete inactivation of the mitotic spindle and lead to the asymmetrical segregation of genetic material during cell division, giving rise to aneuploid and polyploid cells after successive divisions [

46,

76,

77]. Cells with chromosomal disorders (

Figure 4), with loss or gain of genetic material, have altered metabolism, but can be selectively eliminated from young tissues when their functioning is nonviable, further accentuating inhibition of cell division in meristems [

75,

78].

Micronuclei are chromosome fragments created from acentric or lagging chromosomes due to deficiencies in the shortening of microtubules during cell division that fail to incorporate into the nucleus during mitosis, such as those observed in this study in metaphase and anaphase (

Figure 4b and c) [

75,

79]. The recurring presence of micronuclei in meristems characterizes high genetic instability and can manifest as genotypic/phenotypic disturbances to the functioning of plant organs [

56,

75,

80]. Therefore, when considering the ability to cause disturbances to the mitotic spindle (

Figure 4), it is inferred that EtP, as well as being genotoxic to root meristems, proved to be a xenobiotic with a high aneugenic potential for roots.

Thus, establishing that EtP causes significant accumulation of micronuclei in young tissues suggests that this micropollutant at environmentally relevant concentrations threatens crop productivity and sustainability. Furthermore, accumulation of micronuclei in reproductive tissue can result in asymmetrical gametes during meiosis, leading to aborted pollen/egg cells or the developmental pathology of tapetal cells, which manifests as reduced fertility/viable seed production – a toxic Mechanism of Action [

81,

82,

83]. A second Mechanism of Action between EtP and micronuclei in the reduction in crop productivity is the impairment of growth via inhibition of cell division in meristematic tissue [

78,

84,

85,

86,

87]. A third Mechanism of Action is the phenotype consequence of this genotoxicity, which is an increased vulnerability to other environmental stressors, such as heat stress, water stress, as well as infectious diseases [

80,

88,

89,

90]. Therefore, the presence of EtP in amended soils and irrigation water should be avoided during the early phases of crop development. Furthermore, EtP should be used for antimicrobial treatment for human pathogens in green leafy crops only near the end of their growing period, such as for vertical farming of lettuces or post-harvest [

33,

34].

4.2. Oxidative Damage and Oxidative-Stress Homeostatic Responses

Hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, superoxide radicals, and radicals from lipid peroxidation cause significant disturbances to the cell cycle in meristems by denaturing proteins/enzymes such as those responsible for DNA duplication, protein synthesis, polymerization/functioning of the mitotic spindle, and chromosome organization in the different phases of mitosis [

38,

39,

49,

91,

92,

93,

94]. EtP, at all the concentrations evaluated, induced the formation of significant levels of reactive oxygen species in cells (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), which may have contributed cell cycle arrest and mitotic spindle changes in root meristems (

Figure 3b, 3c), significantly inhibiting the growth of rootlets in carrot, tomato, and cucumber (

Figure 2) and of roots in bulbs in A. cepa (

Figure 3a). Parabens are documented to induce cell cycle arrest via non-oxidative damage mechanisms, so the relative contribution of oxidative damage and non-oxidative damage processes to the cumulative manifestation of cell cycle arrest needs to be further explored in plants [

14,

39,

95,

96,

97].

Systemic and cellular toxicity triggered by oxidative stress due to the action of xenobiotics – such as those caused by EtP on plants (

Figures 2, 3, and 4) – are among the leading causes of loss of productivity in different crops around the world, since oxidizing compounds cause disturbances to cellular and physiological mechanisms, which can ultimately alter the economics of organismal homeostasis, leading to reduced fitness and crop yields [

98,

99,

100]. In addition to impacting crop yield, the environmental persistence of EtP-contaminated soils represents a threat to successive crop plantings, altering the calculations for successful future returns of that contaminated field [

101,

102,

103,

104,

105].

Todorovac et al. [

106] observed that EtP caused a reduction in cell proliferation and induced cellular changes in plants in a 24-hour exposure test, corroborating the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity results obtained in the present study. However, the concentrations evaluated by these researchers were in the mg.L

−1 range, which is very high compared to the actual concentrations of this compound in the environment, which generally range from µg to ng. Nevertheless, the results obtained by these researchers highlight the toxicity results obtained for EtP in the present study, since this compound was evaluated at concentrations thousands of times lower, and phytotoxicity, cytotoxicity, and genotoxicity were observed in the roots at concentrations as low as 1 ng.L

−1 (

Figures 2, 3, and 4). Furthermore, Kim et al. [

14] evaluated plants in soils contaminated with EtP at concentrations above 200 mg/kg. They observed a severe reduction in stem and leaf growth and development, and the death of organisms. However, they did not report adverse effects on root development/functioning. Thus, the results obtained by Kim et al. [

14] and Todorovac et al. [

106] complement the results obtained here, suggesting that EtP, being toxic to roots, caused a reduction in water and nutrient absorption, triggering severe changes in the development of the aerial part of the plants. Furthermore, it should be noted that after a thorough search of the scientific literature, only the two studies mentioned above on evaluating EtP on plants were found, which did not consider the oxidative stress triggered by this antimicrobial in these organisms.

4.3. Impact to E. fetida Earthworms

According to ISO [

71], the aversion of earthworms to contaminated soil between 40 and 70% characterizes the moderate repellent effect of the pollutant on these animals, with escape. From 80% onwards, it has been characterized as highly repellent, with escape and loss of habitat. According to Wijayawardena et al. [

107], the repellency of these animals to the soil can significantly impact the survival of different edaphic species since earthworms make up 80% of soil biomass and are fundamental for aeration and decomposition of organic matter, as well as being essential to the terrestrial trophic chain.

Reactive oxygen species induced and resulting from lipid peroxidation have a high potential to cause tissue damage in earthworms, and when it does not cause death, may trigger significant sublethal effects with the potential to significantly alter their ecological functions [

92,

108]. The possible sublethal effects of oxidative stress on these animals can manifest as an inhibition of growth and development, loss of biomass, reduction in reproduction rate, inhibition of cell division, and intestinal and epidermal damage, which consequently make them weaker in the face of adverse environmental conditions [

107].

The mortality potential in

Eisenia andrei Sav. earthworms subjected to EtP at concentrations above 200 mg for 14 days found that the number of deaths was not significant, concluding that EtP does not cause harm to these animals [

5]. However, this study did not assess the oxidative damage levels or the sublethal effects of this xenobiotic on these animals. In Rohu (

Labeo rohita), EtP induced oxidative stress by suppressing antioxidant enzyme activity mainly by causing significant changes in CAT modulation [

109]. Silva et al. [

8] found that this xenobiotic caused oxidative stress in the gills and liver of Oreochromis niloticus, in which SOD activity increased significantly and CAT activity was inhibited. These studies corroborate the multi-animal trend of the enzymatic results observed for earthworms in the present study, emphasizing that EtP triggers oxidative stress. One hypothesis is that it does this by raising the levels of reactive oxygen species in cells through interfering with mitochondrial functionality, perhaps by interfering with electron flow through oxidative phosphorylation [

110,

111,

112,

113,

114]. If this is so, then future studies need to include the assessment of the impact on reproductive organs and their viability [

115].

5. Conclusions

This In plants, EtP triggered oxidative stress that inhibited the progression of the cell cycle and disturbed the organization of chromosomes in metaphase and anaphase, causing a significant reduction in root growth in the different plants.

EtP caused earthworms to escape from contaminated soils in animals at all the concentrations evaluated. EtP did not cause death in earthworms after 14 days of exposure. However, it caused oxidative stress, potentially triggering significant sublethal effects in these organisms.

The data shows the high potential for EtP of not only being an ecological hazard, but a potential threat to both crop productivity and seed viability, and reinforces the need to manage its contamination of agricultural landscapes, both as a component of a soil amendment and an irrigant, but also its use in hydroponics. If used as a human pathogen mitigation measure in leafy green crops that are eaten raw, applying EtP in the field is not recommended. However, it may be a consideration for post-harvest treatment.

Author Contributions

E.A.d.A.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; M.E.N.P.: methodology, investigation; C.A.S. methodology, formal analysis, investigation; A.E.M.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation; M.A.V.R.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation; E.M.G.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation; D.E.S.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; C.H.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation; O.V.J.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation; E.M.V.G.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, software; G.T.T.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation; R.d.S.G.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, supervision; E.D.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision; A.P.P.: Conceptualization, resources, data curation methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Funding

Haereticus Environmental Laboratory (HEL)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EtP |

Ethylparaben |

| BOD |

Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| RGI |

Relative Growth Index |

| GI |

Germination Index |

| ARL |

Average Root Length |

| MI |

Mitotic Index |

| CAI |

Cellular Alteration Index |

| SAT |

Artificial soil |

| CAT |

Catalase |

| APX |

Ascorbate peroxidase |

| GPX |

Guaiacol peroxidase |

| SOD |

Superoxide dismutase |

| U |

Enzyme unit |

| FC |

Folin-Ciocalteu |

References

- Samarasinghe, S.V.; Krishnan, K.; Aitken, R.J.; Naidu, R.; Megharaj, M. Persistence of the parabens in soil and their potential toxicity to earthworms. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 83, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubouchi, L.M.S.; Almeida, E.A.; Santo, D.E. , Bona, E.; Pereira, G.L.D.; Jegatheesan, V.; Valarini Junior, O. Production and Characterization of Graphene Oxide for Adsorption Analysis of the Emerging Pollutant Butylparaben. Water, 2024, 16, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, C.; Sousa, C.A.; Sousa, H.; Vale, F.; Simoes, M. Parabens removal from wastewaters by microalgae–Ecotoxicity, metabolism and pathways. Chem Eng. 2023, 45, 139631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon, C.; Rocha, M.B.; Souza, L.S.; Valarini Junior, O.; Ferreira, P.M.P.; Halmeman, M.C.O.; Oliveira, D.C.O.; Gonzalez, R.S.; Souza, D.C.; Peron, A.P. Toxicity of the emerging pollutants propylparaben and dichloropropylparaben to terrestrial plants. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2024, 31, 45834–45846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, L.; Kim, D.; Kwak, J.I.; Kim, S.W.; Cui, R.; An, Y.J. Species sensitivity distributions for ethylparaben to derive protective concentrations for soil ecosystems. Environ Geochem Health. 2022, 44, 2435–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolujoko, N.B.; Unuabonah, E.I.; Alfred, M.O.; Ogunlaja, A.; Ogunlaja, O.O.; Omorogie, M.O.; Olukanni, O.D. Toxicity and removal of parabens from water: A critical review. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 792, 148092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pycke, B.F.; Brownawell, B.J.; Kinney, C.A.; Furlong, E.T.; Halden, R.U. Occurrence, temporal variation, and estrogenic burden of five parabens in sewage sludge collected across the United States. Sci Total Environ. 2017, 593, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.C.; Serrano, L.; Oliveira, T.M.; Mansano, A.S.; Almeida, E.A.; Vieira, E.M. Effects of parabens on antioxidant system and oxidative damages in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Ecotoxiol Environ Saf. 2018, 162, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Lee, S.; Moon, H.B.; Yamashita, N.; Kannan, K. Parabens in sediment and sewage sludge from the United States, Japan, and Korea: spatial distribution and temporal trends. Environ Sci Technol. 2013, 47, 10895–10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camino-Sánchez, F.J.; Zafra-Gómez, A.; Dorival-García, N.; Juárez-Jiménez, B.; Vílchez, J.L. Determination of selected parabens, benzophenones, triclosan and triclocarban in agricultural soils after and before treatment with compost from sewage sludge: A lixiviation study. Talanta, 2016, 150, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marta-Sanchez, A.V.; Caldas, S.S.; Schneider, A.; Cardoso, S.M.; Primel, E.G. Trace analysis of parabens preservatives in drinking water treatment sludge, treated, and mineral water samples. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018, 25, 14460–14470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derisso, C.R.; Pompei, C.M.E.; Spadoto, M.; Silva, T.P.; Vieira, E.M. Occurrence of parabens in surface water, wastewater treatment plant in southeast of Brazil and assessment of their environmental risk. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Mortimer, M.; Cheng, H.; Sang, N.; Guo, L.H. Parabens as chemicals of emerging concern in the environment and humans: A review. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, M. J.; An, M. J.; Shin, G. S.; Lee, H. M.; Kim, C. H.; Kim, J. W. Methylparaben induces cell-cycle arrest and caspase-3-mediated apoptosis in human placental BeWo cells. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2020, 16, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Jeszka-Skowron, M.; Czarczyńska-Goślińska, B.; Grześkowiak, T. Determination of parabens in Polish river and lake water as a function of season. Anal. Lett. 2016, 49, 1734–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merola, C.; Lai, O.; Conte, A.; Crescenzo, G.; Torelli, T.; Alloro, M.; Perugini, M. Toxicological evaluation and developmental abnormalities induced by exposure to butylparabens and ethylparabens in early life stages of zebrafish. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020, 80, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, M.; Makino, M.; Tatarazako, N. Acute toxicity of parabens and their chlorinated byproducts with Daphnia magna and Vibrio fischeri bioassays. Appl Toxicol. 2009, 29, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.M.; Kim, M.S.; Hwang, U.K.; Jeong, C.B.; Lee, J.S. Effects of methylparaben, ethylparaben, and propylparaben on life parameters and sex ratio in the marine copepod Tigriopus japonicus. Chemosphere, 2019, 226, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghan, K.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.K. Cardio-and neuro-toxic effects of four parabens on Daphnia magna. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020, 268, 115670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byford, J.R.; Shaw, L.E.; Drew, M.G.B.; Pope, G.S.; Sauer, M.J.; Darbre, P.D. Oestrogenic activity of parabens in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002, 80, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finot, F.; Kaddour, A.; Morat, L.; Mouche, I.; Zaguia, N.; Cuceu, C.; Souvervuille, D.; Négrault, S.; Cariou, O.; Essahi, A.; Prigent, N.; Saul, J.; Paillard, L.; Heidingsfelder, P.; Al Jawhari, L.; Hempel, W.M.; El May, M.; Colicchio, B.; Dieterlen, A.; Jeandidier, E.; Sabatier, L.; Clements, J.; M’Kacher, R. Genotoxic risk of ethyl-paraben could be related to telomere shortening. J Appl Toxicol. 2017, 37, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, C.A.; Amin, M.M.; Tabatabaeian, M.; Chavoshani, A.; Amjadi, E.; Afshari, A.; Kelishadi, R. Parabens preferentially accumulate in metastatic breast tumors compared to benign breast tumors and the association of breast cancer risk factors with paraben accumulation. Environ Adv. 2023, 11, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, Y.; Thakur, R.S.; Parveen, T.; Patel, D.K.; Ram, K.R.; Satish, A. Toxicity assessment of parabens in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chemosphere, 2020, 240, 125730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.M. Hashemi, M.; Ebrahimpour, K.; Chavoshani, A. Determination of parabens in wastewater and sludge in a municipal wastewater treatment plant using microwave-assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Environ. Health Eng. Manag. 2019, 6, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenta, T. S.; Barros, A.R.M.; Carvalho, C.D.A.; Santos, A.B.; Firmino, P.I.M. Parabens in aerobic granular sludge systems: impacts on granulation and insights into removal mechanisms. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 753, 142105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabourin, L.; Duenk, P.; Bonte-Gelok, S.; Payne, M.; Lapen, D.R.; Topp, E. Uptake of pharmaceuticals, hormones and parabens into vegetables grown in soil fertilized with municipal biosolids. Sci Total Environ. 2012, 2012 431, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Chen, L.; Kannan, K. Occurrence of parabens in foodstuffs from China and its implications for human dietary exposure. Environ. Int. 2013, 57, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keerthanan, S.; Jayasinghe, C.; Biswas, J.K.; Vithanage, M. Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in the environment: Plant uptake, translocation, bioaccumulation, and human health risks. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 1221–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.I.; Selma, M.V.; Suslow, T.; Jacxsens, L.; Uyttendaele, M.; Allende, A. Pre-and postharvest preventive measures and intervention strategies to control microbial food safety hazards of fresh leafy vegetables. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015, 55, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongman, M.; Chidamba, L.; Korsten, L. Bacterial biomes and potential human pathogens in irrigation water and leafy greens from different production systems described using pyrosequencing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, L.; Ximenes, E.; Ku, S.; Ladisch, M. Foodborne pathogens in horticultural production systems: Ecology and mitigation. Sci Hortic. 2019, 236, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogren, L.; Windstam, S.; Boqvist, S.; Vågsholm, I.; Söderqvist, K.; Rosberg, A.K.; Lindén, J.; Mulaosmanovic, E.; Karlsson, M.; Uhlig, E.; Håkansson, Å. , Alsanius, B. The hurdle approach–A holistic concept for controlling food safety risks associated with pathogenic bacterial contamination of leafy green vegetables. A review. Front Microbiol. 1965. [Google Scholar]

- FDA (Food and Drug Administration) (2023) Leafy Greens STEC Action Plan. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/foodborne-pathogens/leafy-greens-stec-action-plan (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- National Agricultural Law Center (2025) Lettuce Keep it clean: efforts to reduce leafy green contamination. Available online: https://nationalaglawcenter.org/lettuce-keep-it-clean-efforts-to-reduce-leafy-green-contamination/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Guzmán-Guillén, R.; Campos, A.; Machado, J.; Freitas, M.; Azevedo, J.; Pinto, E.; Vasconcelos, V. Effects of Chrysosporum (Aphanizomenon) ovalisporum extracts containing cylindrospermopsin on growth, photosynthetic capacity, and mineral content of carrots (Daucus carota). Ecotoxicol. 2017, 26, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rede, D.; Santos, L.H.; Ramos, S.; Oliva-Teles, F.; Antão, C.; Sousa, S.R.; Delerue-Matos, C. Individual and mixture toxicity evaluation of three pharmaceuticals to the germination and growth of Lactuca sativa seeds. Sci Total Environ. 2019, 673, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atamaleki, A.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.; Gholizadeh, A.; Naimi, N.; Karimi, P.; Thai, V.N.; Fakhri, Y. Concentration of potentially harmful elements (PHEs) in eggplant (Solanum melongena) vegetables irrigated with wastewater: a systematic review and meta-analysis and probabilistic health risk assessment. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 32, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, G.C.S.G.; Barros, D.G.C.; Ratuchinski, L.S.; Okon, C.; Bressiani, P.A.; Santo, D.E.; Duarte, C.C.S.; Ferreira, P. M. P.; Valarini Junior, O.; Pokrywiecki, J. C.; Dusman, E.; Gonzalez, R. S.; Souza, D. C.; Peron, A. P. Adverse Effects of Octocrylene on Cultivated and Spontaneous Plants and in Soil Animal. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, T.A.C.; Ratuchinski, L.S.; Beijora, S.S.; Santo, D.E.; Caleffi, L.F.; Almeida, E.A.; Valarini Junior, O.; Feitoza, L.L.; Ferreira, P.M.P.; Gonzalez, R.S.; Souza, D.C.; Peron, A.P. Ecotoxicity of the antimicrobials methylparaben and propylparaben in mixture to plants. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA (US Environmental Protection Agency). (1996) Ecological Effects Test Guidelines. 850.4200: Seed germination/root elongation toxicity test. Oppts Eco-Effect Guide, 850 series. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_Report.cfm?Lab=ORD&dirEntryID=47927 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2006). Testing Guideline No. 208: Land Plants: Growth Test.

- Herrero, O.; Martín, J.P.; Freire, P.F.; Carvajal López, L.A.; Peropadre, A.; Hazen, M.J. Toxicological evaluation of three contaminants of emerging concern by use of the Allium cepa test. Mut Res. 2012, 743, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, K.M.S.; Oliveira, M.V.G.A.D.; Carvalho, F.R.D.S.; Peron, A.P. Cytotoxicity of food dyes sunset yellow (E-110), bordeaux red (E-123), and tartrazine yellow (E-102) on Allium cepa L. root meristematic cells. Food Sci Technol. 2013, 33, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Barbhai, M.D.; Hasan, M.; Mekhemar, M. Onion (Allium cepa L.) peels: A review on bioactive compounds and biomedical activities. Biomed Pharmacother. 1124. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, D.G.C.; Nascimento, G.C.S.G.; Okon, C.; Rocha, M.B.; Santo, D.E.; Feitoza, L.L.; Valarini Junior, O.; Gonzalez, R.S.; Souza, D.C.; Peron, A.P. Benzophenone-3 sunscreen causes phytotoxicity and cytogenotoxicity in higher plants. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023, 30, 112788–112798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leme, D.M.; Marin-Morales, M.A. Allium cepa test in environmental monitoring: a review on its application. Mut Res. 2009, 682, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Medina, S.; Galar-Martínez, M.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; Torres-Bezaury, R.M.C.; Gasca-Pérez, E. The relationship between cyto-genotoxic damage and oxidative stress produced by emerging pollutants on a bioindicator organism (Allium cepa): the carbamazepine case. Chemosphere,.

- Frâncica, L.S.; Gonçalves, E.V.; Santos, A.A.; Vicente, Y.S.; Gonzalez, R.S.; Almeida, P.M.; Peron, A.P. Antiproliferative, genotoxic and mutagenic potential of synthetic chocolate flavor for food. Braz J Biol. 2022, 82, e243628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, D.E.; Dusman, E.; Gonzalez, R.S.; Romero, A.L.; Nascimento, G.C.S.G.; Moura, M.A.S.; Filipi, A.C.K.; Gomes, E.M.V.; Pokrywiecki, J.C.; Souza, D.C.; Peron, A.P. Prospecting toxicity of octocrylene in Allium cepa L. and Eisenia fetida Sav. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023, 30, 8257–8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Carlesso, W.M.; Kuhn, D.; Altmayer, T.; Martini, M.C.; Tamiosso, C.D.; Hoehne, L. Enzymatic hydrolysis of the Eisenia andrei earthworm: Characterization and evaluation of its properties. Biocat Biotran. 2017, 35, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Singh, J.; Singh, J.; Singh, S.; Sing, S. Avoidance behavior of Eisenia fetida and Metaphire posthuma towards two different pesticides, acephate and atrazine. Chemosphere,.

- Hattab, S.; Boughattas, I.; Cappello, T.; Zitouni, N.; Touil, G.; Romdhani, I.; Banni, M. Heavy metal accumulation, biochemical and transcriptomic biomarkers in earthworms Eisenia andrei exposed to industrially contaminated soils from south-eastern Tunisia (Gabes Governorate). Sci Total Environ. 2023, 887, 163950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, S. Earthworms as Biological Tools for Assessing Soil Pollutants. Environ Ecol. 2024, 42, 2004–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biruk, L.N.; Moretton, J.; Iorio, A.F.; Weigandt, C.; Etcheverry, J.; Filippetto, J.; Magdakeno, A. Toxicity and genotoxicity assessment in sediments from the Matanza-Riachuelo river basin (Argentina) under the influence of heavy metals and organic contaminants. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2017, 15, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas, P.; Heras, J. Phytotoxicity test applied to sewage sludge using Lactuca sativa L. and Lepidium sativum L. Int J Sci Environ Technol. and Lepidium sativum L. Int J Sci Environ Technol. 2018, 15, 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Fiskesjö, G. P The Allium test as standart in enviromental monitoring. Hereditas,.

- Filipi, Á.C.K.; Santos, G.C.G.N.; Bressani, P.A.; Oliveira, A.K.G.; Santo, D.E.; Duarte, C.C.S.; Peron, A.P. Biological effects of sewage sludge–does its incorporation into agricultural soils in the state of Paraná, Brazil, represent an environmental risk? Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (1984). Testing Guideline No. 207: Earthworm, acute toxicity tests.

- ABNT (Brazilian Association of Technical Standards) Soil Quality NBR ISO 17512-1: Escape test to evaluate soil quality and effects of chemical substances on behavior - Part 1: Test with earthworms (Eisenia fetida and Eisenia andrei), 2011.

- Candello, F.P.; Guimarães, J.R.; Nour, E.A.A. Earthworm avoidance behavior to antimicrobial sulfadiazine on tropical artificial soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Contam. 2018, 13, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABNT (Brazilian Association of Technical Standards) NBR 15537: Terrestrial ecotoxicology - Acute toxicity -Test method with earthworm (Lumbricidae), 2014.

- Hendawi, M.; Sauvé, S.; Ashour, M.; Brousseau, P.; Founier, M. A new ultrasound protocol for extrusion of coelomocyte cells from the earthworm Eisenia fetida. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2004, 9, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, T.E.; McKersie, B.D.; Fletcher, R.A. Paclobutrazol-induced tolerance of wheat leaves to paraquat may involve increased antioxidant enzyme activity. J Plant Physiol. 1995, 145, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.A.; Alas, R.M.; Smith, R.J.; Lea, P.J. Response of antioxidant enzymes to transfer from elevated carbon dioxide to air and ozone fumigation, in the leaves and roots of wild-type and a catalase-deficient mutant of barley. Physiol Plant. 2022, 045, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wei, G.; Li, J.; Qian, Q.; Yu, J. Silicon alleviates salt stress and increases antioxidant enzymes activity in leaves of salt-stressed cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Plant Sci.

- Matsuno, H.; Uritani, I. Physiological behavior of peroxidase isozymes in sweet potato root tissue injured by cutting or with black rot. Plant Cell Physiol. 1972, 13, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.I.; Oberley, L.; Li, Y.A. Simple method for clinical assay of superoxide dismutase. Clin Chim Acta. 2020, 34, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Hernandez, J.C.; Taborda-Ocampo, G.; González-Correa, C.H. Folin-Ciocalteu Reaction Alternatives for Higher Polyphenol Quantitation in Colombian Passion Fruits. Int J Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 8871301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastergiadis, A.; Mubiru, E.; Van Langenhove, H.; Meulenaer, B. Malondialdehyde measurement in oxidized foods: evaluation of the spectrophotometric thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) test in various foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9589–9594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidoros, A.N.; Mylon, P.V.; Arnholdt-Schmitt, B. Aox gene structure, transcript variation and expression in plants. Physiol Plant. 2009, 137, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO International Organization for Standardization (2008) ISO 17512–1: soil quality - avoidance test for determining the quality of soils and effects of chemicals on behaviour Part 1: test with earthworms (Eisenia fetida and Eisenia andrei)., 2008.

- Sobrero, M.C.; Rimoldi, F.; Ronco, A.E. Effects of the glyphosate active ingredient and a formulation on Lemna gibba L. at different exposure levels and assessment end-points. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol.

- Borghetti, F.; Ferreira, A.G. Interpretação de resultados de germinação. Germination: from basic to applied. Porto Alegre, Artmed.

- Maluszynska, J.; Juchimiuk, J. Plant genotoxicity: a molecular cytogenetic approach in plant bioassays. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2005, 56, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Caritá, R.; Marin-Morales, M.A. Induction of chromosome aberrations in the Allium cepa test system caused by the exposure of seeds to industrial effluents contaminated with azo dyes. Chemosphere,.

- Fernandes, T.C.; Mazzeo, D.E.C.; Marin-Morales, M.A. Mechanism of micronuclei formation in polyploidizated cells of Allium cepa exposed to trifluralin herbicide. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2007, 88, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sincinelli, F.; Gaonkar, S.S.; Tondepu, S. A. G.; Dueñas, C. J.; Pagano, A. Hallmarks of DNA Damage Response in Germination Across Model and Crop Species. Genes,.

- Jamil, M.U.; Ali, M.M.; Firyal, S.; Ijaz, M.; Awan, F.; Ullah, A. Comparative Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Assessment of Methylparaben and Propylparaben on Allium cepa Root Tips by Comet and Allium cepa Assays. Environ Toxicol. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupina, K.; Goginashvili, A.; Cleveland, D.W. Causes and consequences of micronuclei. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2021, 70, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasniewska, J.; Bara, A. W. Plant cytogenetics in the micronuclei investigation—the past, current status, and perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavarino, A.M.; Rosato, M.; Manzanero, S.; Jiménez, G.; González-Sánchez, M.; Puertas, M.J. Chromosome nondisjunction and instabilities in tapetal cells are affected by B chromosomes in maize. Genetics,.

- Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, P.; Niu, N.; Ma, S. Microspore Abortion and Abnormal Tapetal Degeneration in a Male-sterile Wheat Line Induced by the Chemical Hybridizing Agent SQ-1. Crop Sci. 2015, 55, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Park, H.R.; Park, J.E.; Yu, S.H.; Yi, G.; Kim, J.H.; Koh, W.; Kim, H.H.; Lee, S.S.; Huh, J.H. Reduced fertility caused by meiotic defects and micronuclei formation during microsporogenesis in x Brassicoraphanus. Genes Genom.,.

- Majewska, A.; Wolska, E.; Śliwińska, E.; Furmanowa, M.; Urbańska, N.; Pietrosiuk, A.; Zobel, A.; Kuraś, M. Antimitotic effect, G2/M accumulation, chromosomal and ultrastructure changes in meristematic cells of Allium cepa L. root tips treated with the extract from Rhodiola rosea roots. Caryologia,.

- Hou, J.; Liu, G.N.; Xue, W.; Fu, W.J.; Liang, B.C.; Liu, X.H. Seed germination, root elongation, root-tip mitosis, and micronucleus induction of five crop plants exposed to chromium in fluvo-aquic soil. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2014, 33, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaismailoglu, M.C. Investigation of the potential toxic effects of prometryne herbicide on Allium cepa root tip cells with mitotic activity, chromosome aberration, micronucleus frequency, nuclear DNA amount and comet assay. Caryologia,.

- Badr, A.; El-Shazly, H.H.; Mohamed, H.I. Plant responses to induced genotoxicity and oxidative stress by chemicals. In: Induced genotoxicity and oxidative stress in plants. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2021. pp 103-131.

- Fang, Y.; Gu, Y. Regulation of Plant Immunity by Nuclear Membrane-Associated Mechanisms. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 771065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souguir, D.; Berndtsson, R.; Mzahma, S.; Filali, H.; Hachicha, M. Vicia–Micronucleus Test Application for Saline Irrigation Water Risk Assessment. Plants,.

- Lohani, N.; Singh, M.B.; Bhalla, P.L. Deciphering the vulnerability of pollen to heat stress for securing crop yields in a warming climate. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 2549–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córdoba-Pedregosa, M.C.; Córdoba, F.; Villalba, J.M.; González-Reyes, J.A. Zonal changes in ascorbate and hydrogen peroxide contents, peroxidase, and ascorbate-related enzyme activities in onion roots. Plant Physiol. 2013, 131, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, N.A.; Sofo, A.; Scopa, A.; Roychoudhury, A.; Sarvajeet, S.G.; Iqbal, M.; Lukatkin, A.S.; Pereira, E.; Duarte, A. C.; Ahmad, I. Lipids and proteins - major targets of oxidative modifications in abiotic stressed plants. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015, 22, 4099–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajitha, V.; Thoppil, J.E. Genotoxic and antigenotoxic potential of the aqueous leaf extracts of Amaranthus spinosus Linn using Allium cepa assay. South Afr J Bot. 2016, 102, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijora, S.S.; Vaz, T.A.C.; Santo, D.E.; Almeida, E.A.; Valarini Junior, O.; Parolin, M.; Peron, A.P. Prospecting toxicity of the avobenzone sunscreen in plants. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2024, 31, 44308–44317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, A. M.; Gregoraszczuk, E. Ł. Differential effect of methyl-, butyl-and propylparaben and 17β-estradiol on selected cell cycle and apoptosis gene and protein expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells and MCF-10A non-malignant cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2014, 34, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv-Gal, A.; Berg, M. D.; Dean, M. Paraben exposure alters cell cycle progression and survival of spontaneously immortalized secretory murine oviductal epithelial (MOE) cells. Reprod. Toxicol. 2021, 100, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.S.; Park, Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, C.H.; An, M.J.; Lee, H.M.; Jo, A.R.; Kim, J.; Hwangbo, Y.; Kim, J.W. Propylparaben-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and initiates caspase-3-dependent apoptosis in human lung cells. Genes Genom. 2025, 47, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.S.; Khan, N.A.; Anjum, N.A.; Tuteja, N. Amelioration of cadmium stress in crop plants by nutrients management: Morphological, physiological and biochemical aspects. Plant Stress,.

- Sharma, M.; Gupta, S.K.; Deeba, F.; Pandey, V. Reactive oxygen species in plants: Boon or Bane-Revisiting the Role of ROS, pp. 117-136, 2017.

- Zhu, J.; Cai, Y.; Wakisaka, M.; Yang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Fang, W.; Xu, Y.; Omura, T.; Yu, R.; Zheng, A. L. Mitigation of oxidative stress damage caused by abiotic stress to improve biomass yield of microalgae: A review. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 896, 165200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papendick, R.I.; Elliott, L.F.; Dahlgren, R.B. Environmental consequences of modern production agriculture: How can alternative agriculture address these issues and concerns? Am J Altern Agric. 1986, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, R.L.; Oliver, D.P. contaminants. In Contaminants and the Soil Environment in the Australasia-Pacific Region: Proceedings of the First Australasia-Pacific Conference on Contaminants and Soil Environment in the Australasia-Pacific Region, held in Adelaide, Australia, 18–23 February 1996 (pp.

- Mantovi, P.; Baldoni, G.; Toderi, G. Reuse of liquid, dewatered, and composted sewage sludge on agricultural land: effects of long-term application on soil and crop. Water Res. 2005, 39, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, K.L.; Wratten, S.; Barnes, A.M.; Waterhouse, B.R.; Smith, M.; Lear, G.; Weber, P.; Pizey, M.; Boyer, S. Effects of biosolids on biodiesel crop yield and belowground communities. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 68, 278–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.H.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Buttiglieri, G. Pharmaceutical contamination in edible plants grown on soils amended with wastewater, manure, and biosolids: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2025, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovac, E.; Durmisevic, I.; Cajo, S. Evaluation of DNA and cellular damage caused by methyl-, ethyl-and butylparaben in vitro. Toxicol Environ Chem. 2021, 103, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayawardena, M.A.; Megharaj, M. , Naidu, R. Bioaccumulation and toxicity of lead, influenced by edaphic factors: using earthworms to study the effect of Pb on ecological health. J. Soils Sediments, 1064. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Tripathi, D.K.; Singh, S.; Sharma, S.; Dubey, N.K.; Chauhan, D.K.; Vaculík, M. Toxicity of aluminum on various levels of plant cells and organism: A review. Environ Exp Botany,.

- Akmal, H.; Ahmad, S. , Abbasi, M.H.; Jabeen, F.; Shahzad, K. A study on assessing the toxic effects of ethyl paraben on rohu (Labeo rohita) using different biomarkers; hemato-biochemical assays, histology, oxidant and antioxidant activity and genotoxicity. PloS One, 0302. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Moldéus, P. Mechanism of p-hydroxybenzoate ester-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cytotoxicity in isolated rat hepatocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998, 55, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Moore, G. Role of mitochondrial membrane permeability transition in p-hydroxybenzoate ester-induced cytotoxicity in rat hepatocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 58, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, R.S.; Martins, F.C.; Oliveira, P.J.; Ramalho-Santos, J.; Peixoto, F.P. Parabens in male infertility—Is there a mitochondrial connection? Reprod. Toxicol. 2009, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, F.C.; Videira, R.A.; Oliveira, M.M.; Silva-Maia, D.; Ferreira, F.M.; Peixoto, F.P. Parabens enhance the calcium-dependent testicular mitochondrial permeability transition: Their relevance on the reproductive capacity in male animals. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2021, 35, e22661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Kim, N.; Xu, Y. Methyl paraben affects porcine oocyte maturation through mitochondrial dysfunction. Biomolecules. 2024, 14, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Li, M.; Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Zhou, S.; Dai, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, M.; Tang, W.; Wen, J.; Xue, L. Chronic exposure to propylparaben at the humanly relevant dose triggers ovarian aging in adult mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 235, 113432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Stability of ethylparaben in aqueous media for 7 days in the absence of light.

Figure 1.

Stability of ethylparaben in aqueous media for 7 days in the absence of light.

Figure 2.

Phytotoxic potential of ethylparaben on seeds of Daucus carota L., Lycopersicum sculentum L., and Cucumis sativus L., at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1, based on the parameters Seed Germination, Relative Growth Index, and Germination Index. *Significant difference about the control, according to Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 2.

Phytotoxic potential of ethylparaben on seeds of Daucus carota L., Lycopersicum sculentum L., and Cucumis sativus L., at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1, based on the parameters Seed Germination, Relative Growth Index, and Germination Index. *Significant difference about the control, according to Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Phytotoxic, cytotoxic, and genotoxic potential of ethylparaben, at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1, in Allium cepa L. bulb roots, based on the parameters Average Root Length (ARL), Mitotic Index (MI) and Cell Alteration Index (CAI). *Significant difference about the control, according to Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Phytotoxic, cytotoxic, and genotoxic potential of ethylparaben, at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1, in Allium cepa L. bulb roots, based on the parameters Average Root Length (ARL), Mitotic Index (MI) and Cell Alteration Index (CAI). *Significant difference about the control, according to Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 4.

Cellular alterations observed in root meristems of Allium cepa L. bulbs exposed to ethylparaben at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1. A) chromosome disorder in metaphase, B) chromosome disorder in metaphase with chromosome loss, C) chromosome loss in anaphase, and D) micronucleus. Bar: 10 µm.

Figure 4.

Cellular alterations observed in root meristems of Allium cepa L. bulbs exposed to ethylparaben at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1. A) chromosome disorder in metaphase, B) chromosome disorder in metaphase with chromosome loss, C) chromosome loss in anaphase, and D) micronucleus. Bar: 10 µm.

Figure 5.

Lipid peroxidation (TBARs) and concentration of phenolic compounds (FC) in rootlets of Daucus carota L., Lycopersicum esculentum L., and Cucumis sativus L. exposed to ethylparaben at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1. *Significant difference from the control was observed using a Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p≤0.05).

Figure 5.

Lipid peroxidation (TBARs) and concentration of phenolic compounds (FC) in rootlets of Daucus carota L., Lycopersicum esculentum L., and Cucumis sativus L. exposed to ethylparaben at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1. *Significant difference from the control was observed using a Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p≤0.05).

Figure 6.

Modulations of the enzymes catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), guaiacol peroxidase (GPOX), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in roots of Daucus carota L., Lycopersicum esculentum L., and Cucumis sativus L. exposed to ethylparaben in concentrations 1, 10, 100, e 1000 ng.L-1. *Significant difference about the control according to Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p≤0.05).

Figure 6.

Modulations of the enzymes catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), guaiacol peroxidase (GPOX), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in roots of Daucus carota L., Lycopersicum esculentum L., and Cucumis sativus L. exposed to ethylparaben in concentrations 1, 10, 100, e 1000 ng.L-1. *Significant difference about the control according to Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p≤0.05).

Figure 7.

Modulations of the enzymes catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), guaiacol peroxidase (GPOX), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in roots of Daucus carota L., Lycopersicum esculentum L., and Cucumis sativus L. exposed to ethylparaben in concentrations 1, 10, 100, e 1000 ng.L-1. *Significant difference about the control according to Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p≤0.05).

Figure 7.

Modulations of the enzymes catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), guaiacol peroxidase (GPOX), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in roots of Daucus carota L., Lycopersicum esculentum L., and Cucumis sativus L. exposed to ethylparaben in concentrations 1, 10, 100, e 1000 ng.L-1. *Significant difference about the control according to Kruskal-Wallis H, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (p≤0.05).

Figure 8.

a) Percentage escape of Eisenia fetida Sav. exposed to the positive control (CO+) and ethylparaben at concentrations of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng.L-1 and b) percentage of earthworms in the control soil and soil with EtP concentrations. *Significant difference to the control, according to One-tailed Fischer’s Exact Test (p≤0.05). CO-: negative control; CO+: positive control; E1: 1 ng.L-1; E10: 10 ng.L-1; E100: 100 ng.L-1;; E1000: 1000 ng.L-1.

Figure 8.