Introduction

Cinema has always been a space for experimentation—both artistic and technical. In the twentieth century, directors sought new narrative forms that could engage audiences, while engineers developed new tools for realizing these ideas (Mendes da Silva, 2022). Today, these explorations continue in the field of artificial intelligence. Modern generative models are already capable of creating short video clips from text prompts, and in the future, they may form the basis for generating feature-length films “on the fly”—in real time, tailored to the viewer’s request.

The purpose of this article is twofold: first, to provide technical estimates for the real-time generation of a one-hour film in response to a viewer’s request, with the ability to modify the storyline interactively; and second, to discuss the broader creative, ethical, social, and psychological challenges involved, ranging from questions of authorship and digital actor rights to the transformation of collective viewing experiences.

Historical Examples

Kinoautomat (1967): The First Experiment in Interactive Cinema

The project Kinoautomat, created by Radúz Činčera and presented at Expo 67 in Montreal, entered history as the first film that allowed audiences to choose how the story developed (Hales, 2005). Spectators in the theater voted on the direction of events, while a host on stage commented and announced the results. The film was pre-recorded in several variants, and during the screening the projection switched to the relevant segment. Although the technology did not allow scenes to be generated live, the cultural significance of the project was enormous: it demonstrated that the audience could become active participants in the narrative.

Bandersnatch (2018): Netflix and the Revival of Interactive Film

In 2018, Netflix released Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, the first large-scale digital experiment in interactive film. At key points, the viewer was asked to make choices that altered the storyline, leading to multiple endings (about five main ones, with numerous variations). To implement the project, Netflix developed a special tool called Branch Manager, which handled the branching script and narrative logic. Bandersnatch provoked wide discussion, becoming an example of how traditional cinema can merge with gaming elements and interactive storytelling (Zhang, 2023). Earlier works had already examined interactive cinema in projects such as Kinoautomat and Sufferrosa (Ng, 2011).

Contemporary Advances in AI Video

Since the mid-2020s, generative video models have been advancing rapidly. OpenAI introduced Sora, Google presented Veo, and startups such as Runway, Pika, and Kling are developing tools to generate short clips from text prompts. These systems can currently produce videos lasting 10–120 seconds, sometimes at near-professional quality. However, they remain limited by weak long-term narrative coherence, difficulty in maintaining consistent characters and environments across multiple scenes, and extremely high computational costs.

Technical Performance Estimates

Generating a one-hour video in real time on user request requires aligning the computational load of image and video generation models with the available performance of modern GPUs.

1. Baseline workload model

- Modern diffusion-based image models for high-resolution images (e.g., 1024×1024 px, 30–50 diffusion steps) require on the order of 50–100 TFLOPS to generate a single frame.

- For real-time video (30 fps, 3600 seconds) the total number of frames is 108,000.

- Naive estimate without optimizations:

100 TFLOPS × 30 fps ≈ 3,000 TFLOPS (3 PFLOPS) of sustained compute. This is equivalent to hundreds of top-tier GPUs such as the NVIDIA H100.

2. Refined estimates

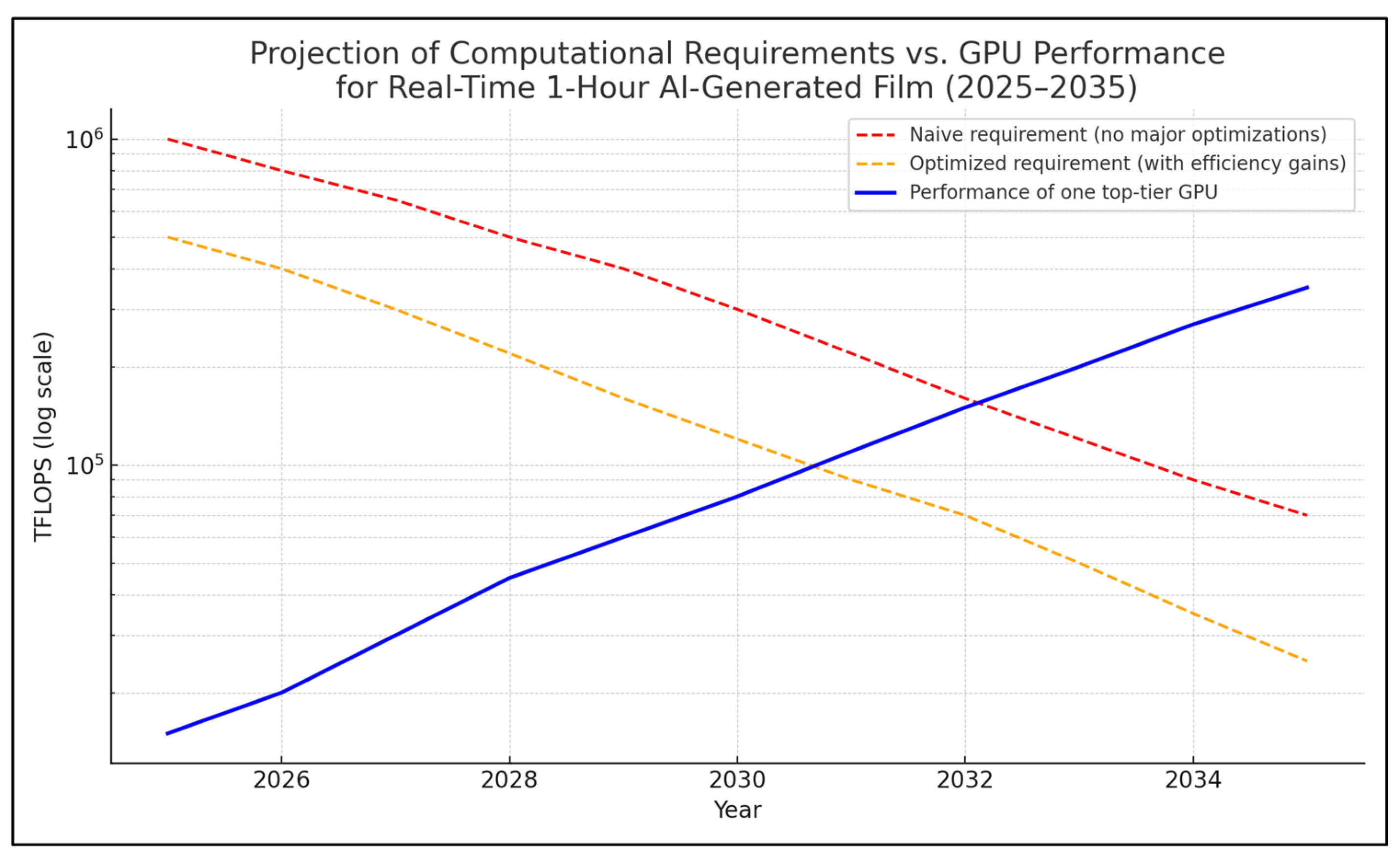

- For a full one-hour film, assuming 30–50 diffusion steps per frame, the total workload amounts to between 10^5 and 10^6 TFLOPS.

- These values form the basis of the ‘red line’ (naive scenario) in the chart.

3. Optimized scenario

- In the coming years, substantial improvements in model architectures can be expected: moving from iterative diffusion methods to direct generative transformers, hybrid motion-predictive systems, and recursive frame schemes.

- Such optimizations could reduce the workload by a factor of three to five or more. These estimates correspond to the

orange line in

Figure 1.

4. GPU performance growth

- In 2025, top GPUs deliver on the order of 15–20k TFLOPS (FP16).

Assuming a historical growth rate (~×1.5–2 every 2–3 years), consistent with empirical measurements of GPU price-performance doubling time of ~2.0–2.3 years in ML hardware (Epoch AI, 2022; Epoch AI, 2025), by 2030 a single card may reach 100–200k TFLOPS, and by 2035 up to 300–400k TFLOPS.

- These values correspond to the ‘blue line’ in the chart.

5. Curve intersections

- The naive scenario only intersects projected GPU performance after 2035.

- The optimized scenario may become feasible on a single card as early as the early 2030s, provided active algorithmic progress.

6. Conclusion

- Fully interactive, on-demand film generation in real time remains infeasible today.

- In the near term, it will require clusters of dozens of GPUs.

- By the mid-2030s, performing the task on a single GPU becomes realistic, opening the way to mass adoption.

Prospects of Kinoautomat 2.0

The next generation of technology could surpass the 1967 experiment. While Kinoautomat offered choices only between pre-filmed segments, AI may enable the creation of an entire movie tailored to the viewer—with unique actors, branching narratives, and even customizable visual styles. Applications could include personalized films, educational projects, therapeutic practices, and new entertainment formats blending cinema and gaming.

Key Challenges

1. Technical:

- Immense computational power is required, currently available only on the scale of supercomputers.

- Extremely low latency is essential: the viewer’s choices must appear on screen instantly.

2. Creative:

Preserving narrative coherence. Even with audience input, the story must remain logical and emotionally engaging. For example, the viewer does not necessarily need to know the entire story arc in advance; the narrative may dynamically adapt after each choice, ensuring that the progression remains unpredictable until the very end.

Balancing freedom of choice with dramaturgical logic. Too much freedom risks producing chaos, while too little undermines the sense of interactivity.

Musical scoring: how can soundtracks remain synchronized with dynamically shifting narratives?

3. Ethical:

- Authorship: who owns a film co-created by AI and the viewer?

- Use of digital replicas of real actors: rights and consent must be strictly regulated.

4. Social:

- The experience of collective viewing may change if every spectator has a unique film.

- Will the cultural value of a “shared film” survive in such a landscape?

5. Psychological and Creative:

- Not all viewers may feel comfortable seeing themselves or loved ones as film characters.

- How much narrative freedom should the client have—from minor changes to complete rewriting?

- Age restrictions: from what age should adolescents be allowed to participate? Educational uses may prove valuable (historical reenactments, quizzes, interactive lessons).

- Where does the boundary lie between a game and a work of cinematic art?

Potential Applications Once Computing Power Is Available

1. Viewer avatars. The spectator becomes the hero of the film, with a digital avatar reproducing their appearance, voice, and mannerisms.

2. Gift films. Personalized stories where friends or loved ones appear as characters, serving as unique presents.

3. Competitions of personalized films. New formats of festivals and contests where audiences create and compare their own films.

4. Commercialization. Commissioned films as a new entertainment industry: from premium personalized blockbusters to short selfie-stories for social media.

5. Education and science. Personalized films as powerful tools for teaching and research: historical reconstructions, simulation of experiments, immersive training environments.

Prospects of Quantum Computing

Quantum computers are unlikely to directly replace GPUs for real-time video generation, but they may play an important role in accelerating training and optimization. In the long run, quantum AI may lead to new types of generative systems capable of modeling complex correlations and producing more realistic simulations. Their role will likely be indirect—serving as catalysts for new approaches in personalized cinema (Schuld et al., 2015; Biamonte et al., 2017).

Conclusions

Kinoautomat (1967) and Bandersnatch (2018) were milestones in the development of interactive cinema. Contemporary advances in AI indicate that real-time personalized film generation is a matter of time and resources. While significant technical, ethical, and social barriers remain, the trajectory is clear: in the coming decades, we may witness the emergence of a new art form—personalized, interactive cinema created in real time.

References

- Bharti, K., Cervera-Lierta, A., Kyaw, T. H., Haug, T., Alperin-Lea, S., Anand, A., … & Aspuru-Guzik, A. (2022). Noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) algorithms. Reviews of Modern Physics, 94(1), 015004. [CrossRef]

- Biamonte, J., Wittek, P., Pancotti, N., Rebentrost, P., Wiebe, N., & Lloyd, S. (2017). Quantum machine learning. Nature, 549(7671), 195–202. [CrossRef]

- Epoch AI. (2022). Trends in GPU price-performance. Retrieved from https://epoch.ai/blog/trends-in-gpu-price-performance.

- Epoch AI. (2025). Machine learning trends. Retrieved from https://epoch.ai/trends.

- Gyongyosi, L., & Imre, S. (2019). A survey on quantum computing technology. Computer Science Review, 31, 51–71. [CrossRef]

- Hales, C. (2005). Cinematic interaction: From Kinoautomat to cause and effect. Digital Creativity, 16(1), 54–64. [CrossRef]

- Lunenfeld, P., Mendes da Silva, B., Carrega, J., & Koenitz, H. (2021). The forking paths – Interactive film and media. ISBN: 978-989-9023-53-6; ISBN (eBook): 978-989-9023-54-3.

- Ng, J. (2011). Fingers, futures, fates: Viewing interactive cinema in Kinoautomat and Sufferrosa. Screening the Past, 32. http://www.screeningthepast.com/2011/11/fingers-futures-fates-viewing-interactive-cinema-in-kinoautomat-and-sufferrosa.

- Preskill, J. (2018). Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum, 2, 79. [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M., Sinayskiy, I., & Petruccione, F. (2015). An introduction to quantum machine learning. Contemporary Physics, 56(2), 172–185. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. (2023). Be a part of the narrative: How audiences are introduced to the ‘free choice dilemma’ in the interactive film Bandersnatch. Mutual Images Journal, 11, 85–107. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).