Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiological Association Between Obesity and Multiple Sclerosis

2.1. The Role of Chronic Inflammation in the Pathophysiology of MS

2.1.1. Anti-Inflammatory Adipokines in MS

2.1.1.1. Adiponectin

2.1.1.2. Apelin

2.1.2. Proinflammatory Adipokines in Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

2.1.2.1. Leptin

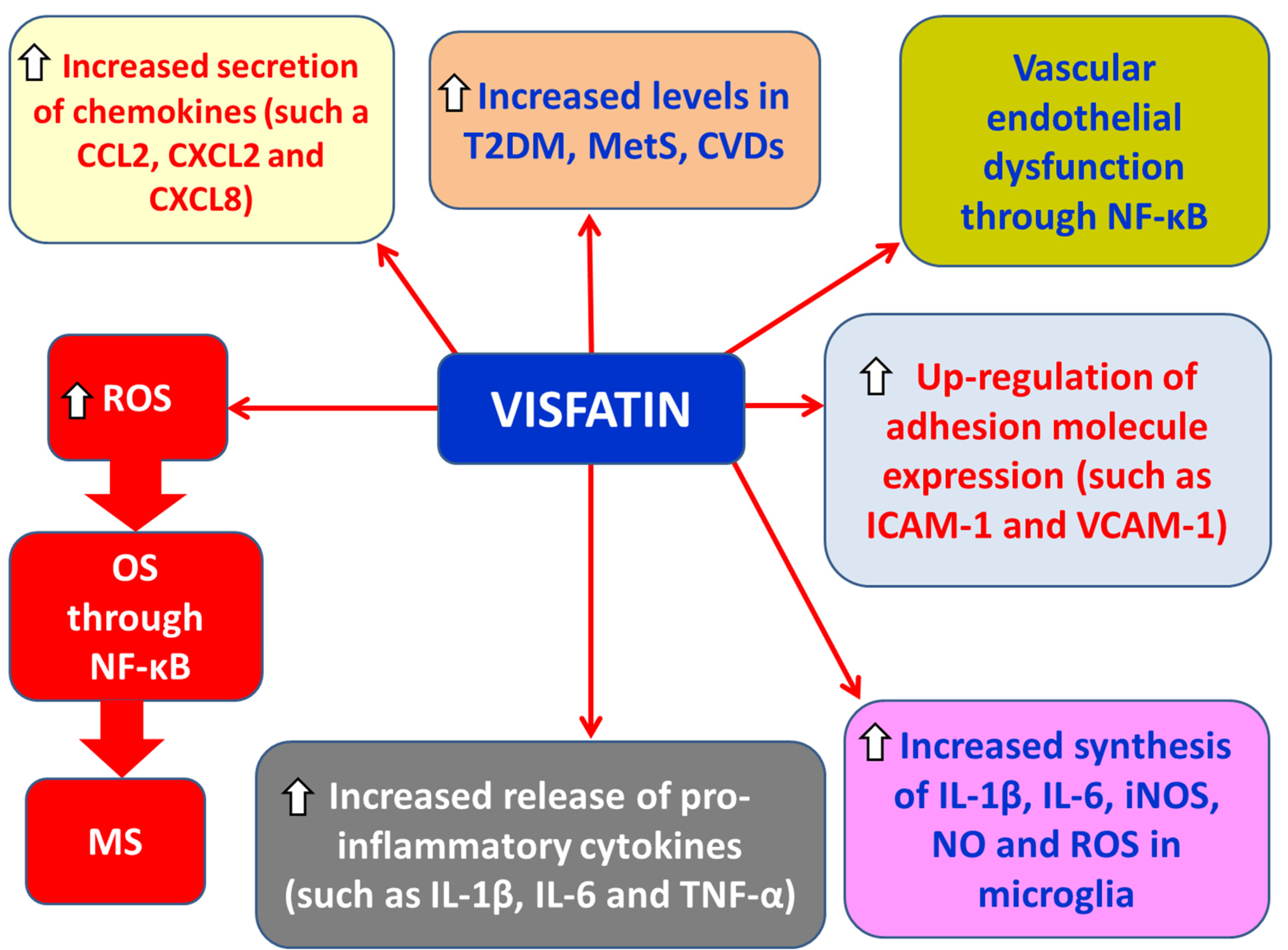

2.1.2.2. Visfatin

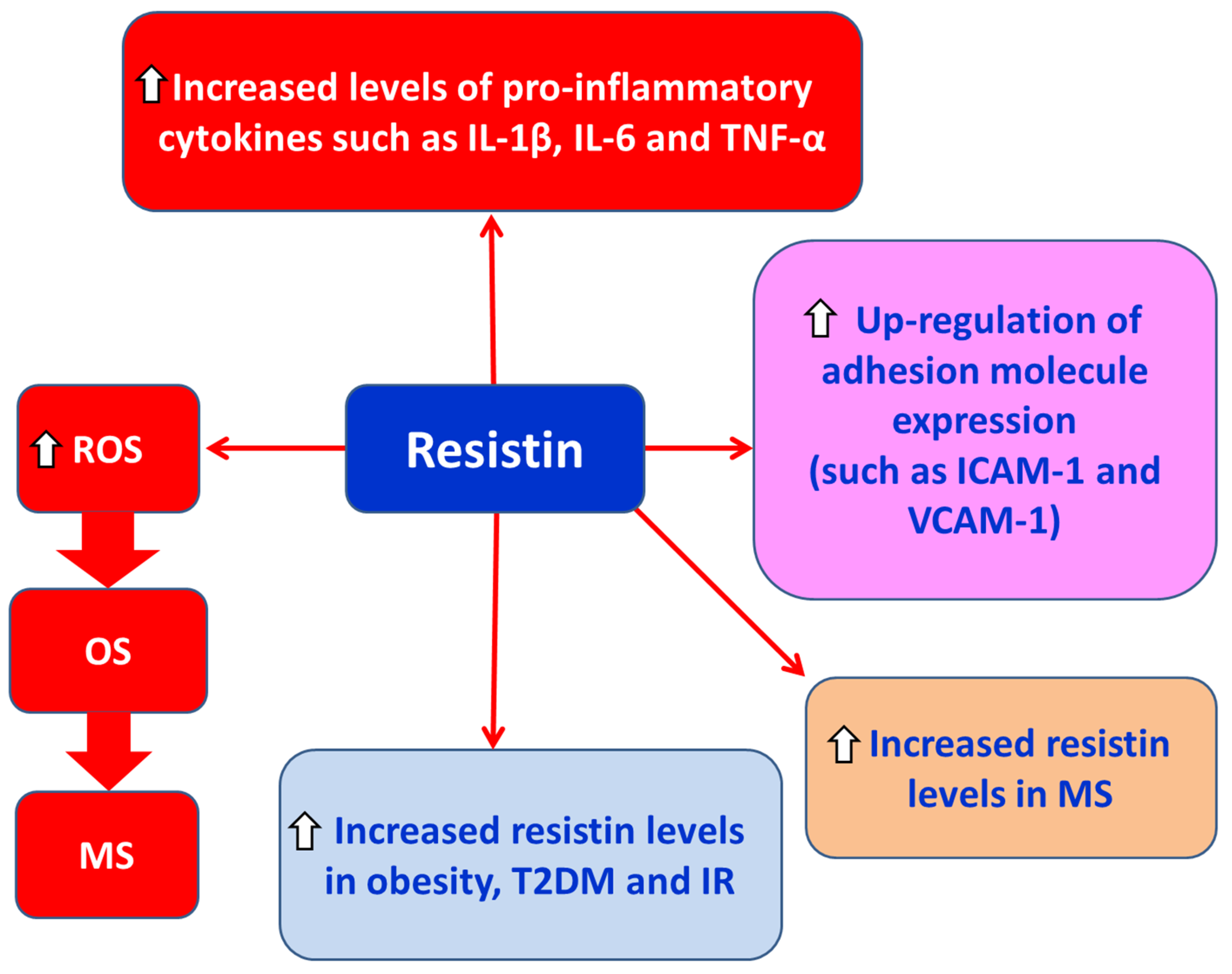

2.1.2.3. Resistin

2.1.2.4. Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)

2.1.2.5. Chemerin

2.1.2.6. Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4 (FABP-4)

2.1.3. Pro-inflammatory Cytokines in MS

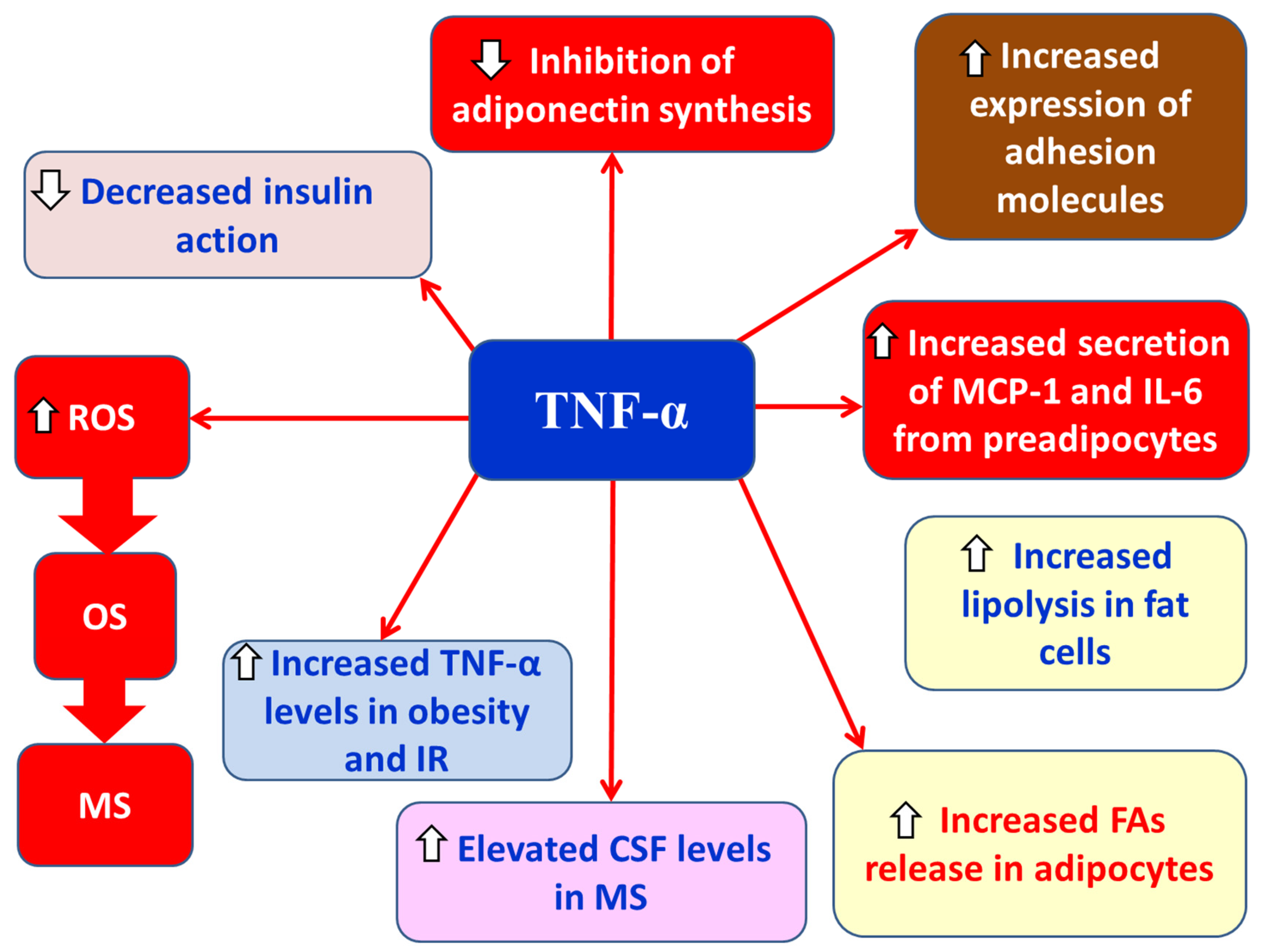

2.1.3.1. TNF-α

2.1.3.2. IL-6

2.1.3.3. IL-8

2.1.3.4. IL-18

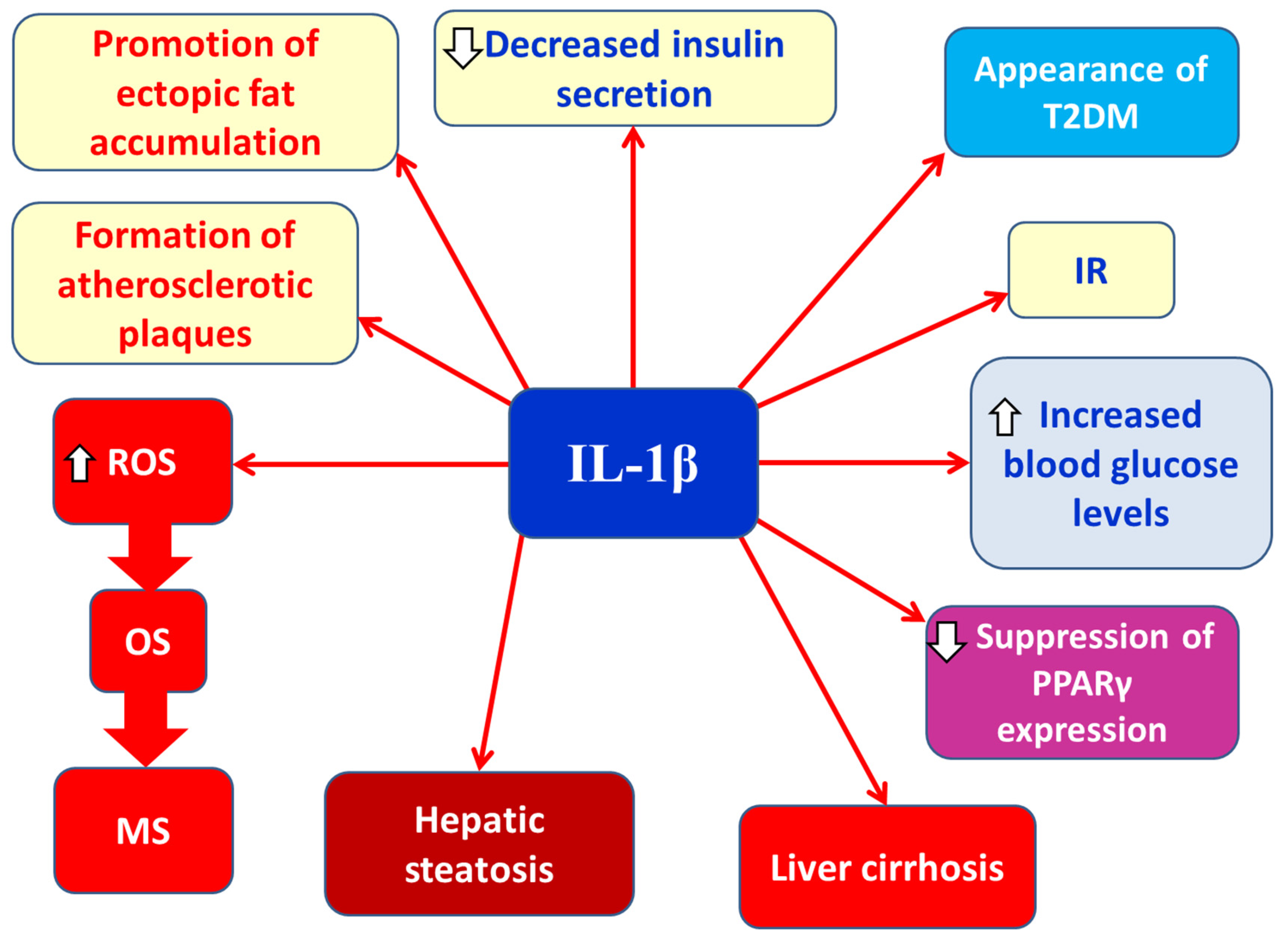

2.1.3.5. IL-1β

2.1.4. Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in MS

2.1.4.1. IL-10

2.2. Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Obesity and MS

2.3. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Obesity and Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

3. Oxidative Stress (OS) in Obesity and Multiple Sclerosis

4. Antioxidant Compounds in the Management of Multiple Sclerosis

4.1. Antioxidants as Complementary Therapy in MS

4.1.1. Vitamin D

4.1.2. Vitamin A

4.1.3. Curcumin

4.1.4. Resveratrol

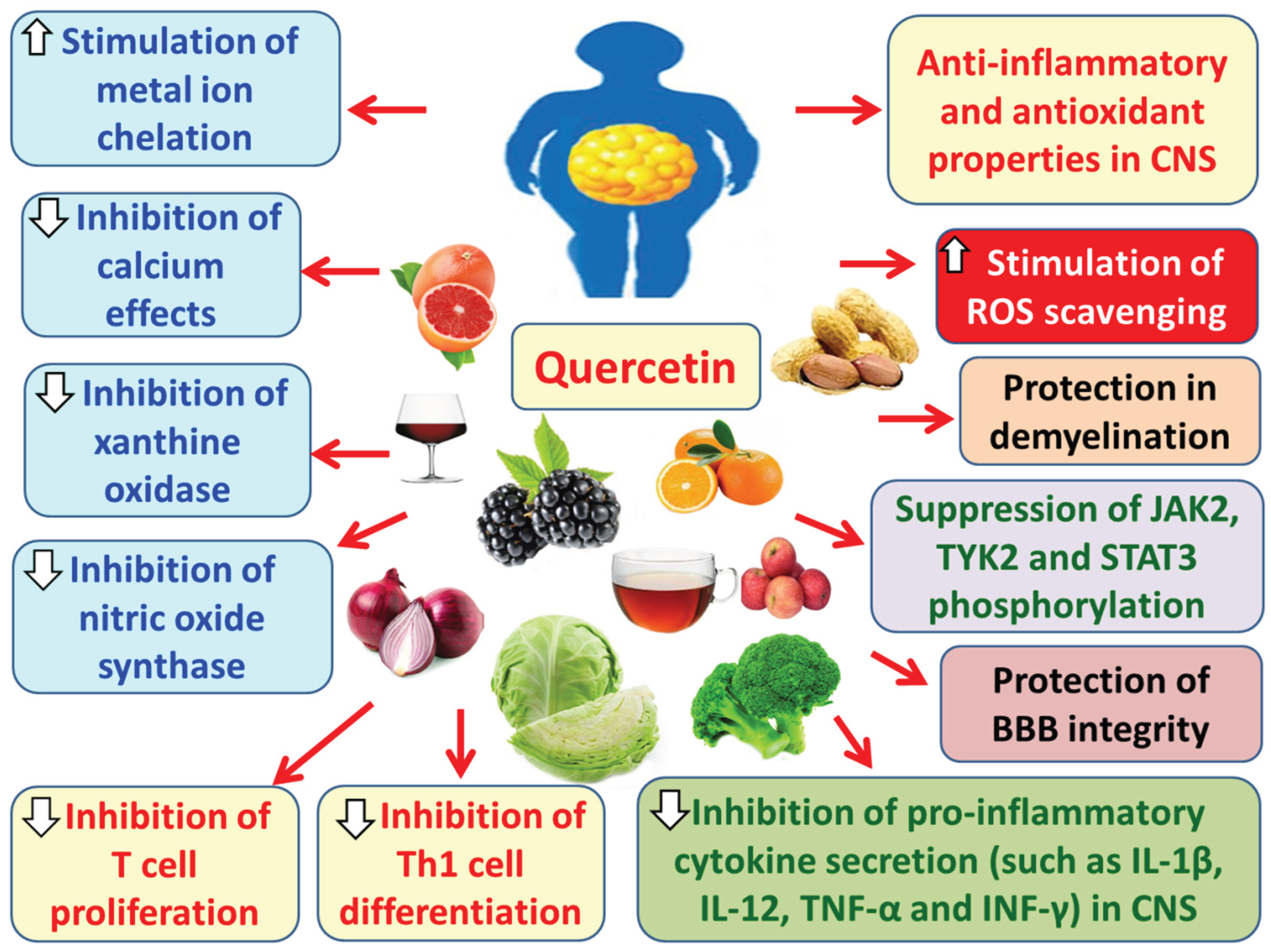

4.1.5. Quercetin

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflict of Interest

References

- Wen, X.; Zhang, B.; Wu, B.; et al. Signaling pathways in obesity: mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overs, S.; Hughes, C.M.; Haselkorn, J.K.; Turner, A.P. Modifiable comorbidities and disability in multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2012, 12, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrá-Sánchez, H.; Harhay, M.O.; Harhay, M.M.; McElligott, S. Prevalence trends of metabolic syndrome in the adult, U.S. population, 1999-2010. JACC 2013, 62, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versini, Μ.; Jeandel, P.-Y.; Rosenthal, E.; Shoenfeld, Y. Obesity in autoimmune diseases: not a passive bystander. Autoimmunity Reviews 2014, 13, 981–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremese, E.; Tolusso, B.; Gigante, M.R.; Ferraccioli, G. Obesity as a risk and severity factor in rheumatic diseases (autoimmune chronic inflammatory diseases). Front Immunol 2014, 5, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiat, V.R.; Reis, G.; Valera, I.C.; Parvatiyar, K.; Parvatiyar, M.S. Autoimmunity as a sequela to obesity and systemic inflammation. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 887702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varra, F.-N.; Varras, M.; Varra, V.-K.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P. Molecular and pathophysiological relationship between obesity and chronic inflammation in the manifestation of metabolic dysfunctions and their inflammation-mediating treatment options (Review). Mol Med Rep 2024, 29, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LMoroni, I. Bianchi, and A. Lleo: Geoepidemiology, gender and autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev 2012, 11, A386–A392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, Overweight/obesity: overweight by country. Global Health Observatory Data Repository 2008–2013, 2016, [internet]. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk factors/obesity text/en/.

- Guerrero-García, J.J.; Carrera-Quintanar, L.; López-Roa, R.I.; Márquez-Aguirre, A.L.; Rojas-Mayorquín, A.E.; Daniel Ortuño-Sahagún, D. Multiple Sclerosis and Obesity: Possible Roles of Adipokines. Mediators Inflamm 2016, 2016, 4036232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lublin, F.D.; Reingold, S.C.; Cohen, J.A.; Cutter, G.R.; Thompson, A.J.; Wolinsky, J.S.; et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2013, 83, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milo, R.; Miller, A. Revised diagnostic criteria of multiple sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev 2014, 13, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch-Henriksen, N.; Sørensen, P.S. The changing demographic pattern of multiple sclerosis epidemiology. Lancet Neurol 2010, 9, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trojano, M.; Lucchese, G.; Graziano, G.; Taylor, B.V.; Simpson SJr Lepore, V.; et al. Geographical variations in sex ratio trends over time in multiple sclerosis. PloS One 2012, 7, e48078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melcon, M.O.; Correale, J.; Melcon, C.M. Is it time for a new global classification of multiple sclerosis? J Neurol Sci 2014, 344, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correale, J.; Marrodan, M. Multiple sclerosis and obesity: The role of adipokines. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1038393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Leweling, H. Multiple sclerosis and nutrition. Mult Scler 2005, 11, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marck, C.H.; Neate, S.L.; Taylor, K.L.; Weiland, T.J.; Jelinek, G.A. Prevalence of comorbidities, overweight and obesity in an international sample of people withmultiple sclerosis and associations with modifiable lifestyle factors. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedström, A.; Alfredsson, L.; Olsson, T. Environmental factors and their interactions with risk genotypes in MS susceptibility. Curr Opin Neurol 2016, 29, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Habibzadeh, A.; Korkorian, R.; Mohamadi, M.; Shaygannejad, V.; Zabeti, A.; Mirmosayyeb, O. Abnormal body mass index is associated with risk of multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract 2024, 18, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrie, R.A.; Horwitz, R.I.; Cutter, G.; Tyry, T.; Vollmer, T. Association between comorbidity clinical characteristics of MS. Acta Neurol Scand 2011, 124, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S.R.; Colado Simão, A.N.; Kallaur, A.P.; et al. Disability in patients with multiple sclerosis: influence of insulin resistance, adiposity, and oxidative stress. Nutrition 2014, 30, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokry, L.E.; Ross, S.; Timpson, N.J.; et al. Obesity and multiple sclerosis: a mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med 2016, 13, e1002053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredsson, L.; Olsson, T. Lifestyle and environmental factors in multiple sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2019, 9, a028944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Yu, H.; Bu, Z.; Wen, L.; Yan, L.; Feng, J. Focus on the Role of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in multiple sclerosis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapeutics. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 894298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwitz, A.; Birk, R. Adipose tissue hyperplasia and hypertrophy in common and syndromic obesity-The case of BBS obesity. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasa, R.; Maier, S.; Barcutean, L.; Stoian, A.; Motataianu, A. The direct deleterious effect of Th17 cells in the nervous system compartment in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: One possible link between neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Rev Romana Med Laborator 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raud, B.; McGuire, P.J.; Jones, R.G.; Sparwasser, T.; Berod, L. Fatty acid metabolism in CD8+ T cell memory: Challenging current concepts. Immunol Rev 2018, 283, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varra, F.-N.; Varras, M.; Karikas, G.-A.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P. Mechanistic interrelation between Multiple Sclerosis and the factors related to obesity. Involvement of antioxidants. Pharmakeftiki, 2025, 37, 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni, G. The neurodegenerative prodrome in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2017, 16, 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalonen, T.O.; Pulkkinen, K.; Ukkonen, M.; Saarela, M.; Elovaara, I. Differential intracellular expression of CCR5 and chemokines in multiple sclerosis subtypes. J Neurol 2002, 249, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Chen, G. Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors in Multiple Sclerosis. Mediators Inflamm 2014, 2014, 659206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanski, M.; Degasperi, G.; Coope, A.; Morari, J.; Denis, R.; Cintra, D.E.; et al. Saturated fatty acids produce an inflammatory response predominantly through the activation of TLR4 signaling in hypothalamus: implications for the pathogenesis of obesity. J Neurosci 2009, 29, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccio, L.; Cantoni, C.; Henderson, J.G.; Hawiger, D.; Ramsbottom, M.; Mikesell, R.; Ryu, J.; Hsieh, C.S.; Cremasco, V.; Haynes, W.; et al. Lack of adiponectin leads to increased lymphocyte activation and increased disease severity in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Immunol 2013, 43, 2089–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, A.R.; Gholipour, S.; Sharifi, R.; Yadegari, S.; Abbasi-Kolli, M.; Masoudian, N. Plasma levels of CTRP-3, CTRP-9 and apelin in women with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2019, 333, 576968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düzel, B.; Tamam, Y.; Çoban, A.; Tüzün, E. Adipokines in multiple sclerosis patients with and without optic neuritis as the first clinical presentation. Immunol Investig 2018, 48, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signoriello, E.; Lus, G.; Polito, R.; Casertano, S.; Scudiero, O.; Coletta, M.; Monaco, M.L.; Rossi, F.; Nigro, E.; Daniele, A. Adiponectin profile at baseline is correlated to progression and severity of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2019, 26, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signoriello, E.; Mallardo, M.; Nigro, E.; Polito, R.; Casertano, S.; Di Pietro, A.; Coletta, M.; Monaco, M.L.; Rossi, F.; Lus, G.; et al. Adiponectin in cerebrospinal fluid from patients affected by multiple sclerosis is correlated with the progression and severity of disease. Mol Neurobiol 2021, 58, 2663–2670, Erratum in 2021, 58, 2671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Musabak, U.H.; Demirkaya, S.; Genç, G.; Ilikci, R.S.; Odabasi, Z. Serum adiponectin, TNF-α, IL-12p70, and IL-13 levels in multiple sclerosis and the effects of different therapy regimens. Neuroimmunomodulation 2011, 18, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraszula, Ł.; Jasińska, A.; Eusebio, M.-O.; Kuna, P.; Głąbiński, A.; Pietruczuk, M. Evaluation of the relationship between leptin, resistin, adiponectin and natural regulatory T cells in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neurochir Polska 2012, 46, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijnsburger, M.; Djuric, N.; Mulder, I.A.; de Vries, H.E. Adipokines as immune cell modulators in multiple sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 10845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pitzer, A.L.; Li, X.; Li, P.L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Instigation of endothelial Nlrp3 inflammasome by adipokine visfatin promotes inter-endothelial junction disruption: role of HMGB1. J Cell Mol Med 2015, 19, 2715–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpua, M.; Turkel, Y.; Dag, E.; Kisa, U. Apelin-13, A promising biomarker for multiple sclerosis? Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2018, 21, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Sun, W.; Chen, X. The Role of apelin/apelin receptor in energy metabolism and water homeostasis: A comprehensive narrative review. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 632886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Muramatsu, M.; Kato, Y.; Sharma, B. Age-dependent decline in remyelination capacity is mediated by apelin/APJ signaling. Nat Aging 2021, 1, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhuo, S.; Wang, X.; Gu, C.; Guo, Q.; Li, X.; et al. Apelin alleviated neuroinflammation and promoted endogenous neural cells proliferation and differentiation after spinal cord injury in rats. J Neuroinflam 2022, 19, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragano, N.R.; Haddad-Tovolli, R.; Velloso, L.A. Leptin, Neuroinflammation and Obesity. Front Horm Res 2017, 48, 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, A.G.; Crujeiras, A.B.; Casanueva, F.F.; Carreira, M.C. Leptin, obesity, and leptin resistance: Where are we 25 years later? Nutrients 2019, 11, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, R.; Bhattacharya, P.; Dey, R.; Nakhasi, H.L. Leptin Functions in Infectious Diseases. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, K.; Nichols, A.G.; Alwarawrah, Y.; MacIver, N.J. Effects of T cell leptin signaling on systemic glucose tolerance and T cell responses in obesity. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Yu, S.; Zheng, R. The leptin resistance. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018, 1090, 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.W.; Myers, M.G., Jr. Leptin and the maintenance of elevated body weight. Nat Rev Neurosci 2018, 19, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarese, G.; Carrieri, P.B.; Montella, S.; De Rosa, V.; La Cava, A. Leptin as a metabolic link to multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2010, 6, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelopoulos, M.E.; Koutsis, G.; Markianos, M. Serum leptin levels in treatment-naive patients with clinically isolated syndrome or relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Autoimmune Dis 2014, 2014, 486282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Hsuchou, H.; Kastin, A.J.; Mishra, P.K.; Wang, Y.; Pan, W. Leukocyte infiltration into spinal cord of EAE mice is attenuated by removal of endothelial leptin signaling. Brain Behav Immun 2014, 40, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.R.; Bae, Y.H.; Bae, S.K.; Choi, K.S.; Yoon, K.H.; Koo, T.H.; et al. Visfatin enhances ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression through ROS-dependent NF-kappaB activation in endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008, 1783, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 58 Xu, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, X. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial neuroinflammation: Attenuation by FK866. Neurochem Res 2021, 46, 1291–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, F.; Roncucci, L. Chemerin/chemR23 axis in inflammation onset and resolution. Inflammation Res 2015, 64, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emamgholipour, S.; Eshaghi, S.M.; Hossein-nezhad, A.; Mirzaei, K.; Maghbooli, Z.; Sahraian, M.A. Adipocytokine profile, cytokine levels and foxp3 expression in multiple sclerosis: A possible link to susceptibility and clinical course of disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein-Nezhad, A.; Varzaneh, F.N.; Mirzaei, K.; Emamgholipour, S.; Varzaneh, F.N.; Sahraian, M.A. A polymorphism in the resistin gene promoter and the risk of multiple sclerosis. Minerva Med. 2013, 104, 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, J.S.; Bhatti, G.K.; Reddy, P.H. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in metabolic disorders—A step towards mitochondria based therapeutic strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Basis Dis 2016, 1863, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, J.K.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Metabolic Messengers: Tumour necrosis factor. Nat Metab 2021, 3, 1302–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebas, H.; Guérit, S.; Picot, A.; Boulay, A.C.; Fournier, A.; Vivien, D.; Salmon, M.C.; Docagne, F.; Bardou, I. PAI-1 production by reactive astrocytes drives tissue dysfibrinolysis in multiple sclerosis models. Cell Mol Life Sci 2022, 79, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, S.; Fruscione, F.; Morando, S.; Ferrando, T.; Poggi, A.; Garuti, A.; et al. Catastrophic NAD+ depletion in activated Tlymphocytes through nampt inhibition reduces demyelination disability in, EAE. PloS One 2009, 4, e7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.R.; Bhattacharya, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Nargis, T.; Rahaman, O.; Duttagupta, P.; et al. Adipose recruitment and activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells fuel metaflammation. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3440–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, Y.M.; Li, W.Q.; Huang, C.L.; Li, J.; Xie, W.H.; et al. Ccrl2 deficiency deteriorates obesity and insulin resistance through increasing adipose tissue macrophages infiltration. Genes Dis 2022, 9, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, R.; Gafa, V.; Serafini, B.; Giacomini, E.; Visconti, A.; Remoli, M.E.; et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in multiple sclerosis: intracerebral recruitment and impaired maturation in response to interferon-beta. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2008, 67, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomalka-Kochanowska, J.; Baranowska, B.; Wolinska-Witort, E.; Uchman, D.; Litwiniuk, A.; Martynska, L.; Kalisz, M.; Bik, W.; Kochanowski, J. Plasma chemerin levels in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 2014, 35, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koskderelioglu, A.; Gedizlioglu, M.; Eskut, N.; Tamer, P.; Yalcin GBozkaya, G. Impact of chemerin, lipid profile, and insulin resistance on disease parameters in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 2021, 42, 2471–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.J.; Thompson, B.R.; Sanders, M.A.; Bernlohr, D.A. Interaction of the adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein with the hormone-sensitive lipase: regulation by fatty acids and phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 32424–32432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, R.; Healy, B.C.; Musallam, A.; Soltany, P.; Diaz-Cruz, C.; Sattarnezhad, N.; et al. Fatty acid binding protein-4 is associated with disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2019, 25, 344–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.X.; Wang, T.; Su, H.X.; Gao, D.D.; Xu, Y.C.; Li, Y.X.; et al. Exogenous FABP4 interferes with differentiation, promotes lipolysis and inflammation in adipocytes. Endocrine 2020, 67, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, S.; Vargas-Lowy, D.; Musallam, A.; Healy, B.C.; Kivisakk, P.; Gandhi, R.; et al. Increased leptin a-FABPlevels in relapsing progressive forms of MS. BMC Neurol 2013, 13, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuhashi, M.; Saitoh, S.; Shimamoto, K.; Miura, T. Fatty Acid-Binding Protein 4 (FABP4): Pathophysiological insights and potent clinical biomarker of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Clin Med Insights Cardiol 2015, 8 (Suppl. S3), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuhashi, M. Fatty acid-binding protein 4 in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb 2019, 26, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, J.M.; Liu, Q.; Brittingham, K.C.; Liu, Y.; Gruentha, M.; Gorgun, C.Z.; et al. Deficiency of fatty acid-binding proteins in mice confers protection from development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2007, 179, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Hong, H.J.; Youn, B.S.; Kim, T.S. Adiponectin induces dendritic cell activation via PLCg/JNK/NF-kB pathways, leading to Th1 and Th17 polarization. J Immunol 2012, 188, 2592–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, M.M.G.; Eisele, S.J.G. MicroRNAs as a possible biomarker in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. IBRO Neurosci Rep 2022, 13, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, R.; Ashbaugh, J.J.; Magliozzi, R.; et al. Inhibition of soluble tumour necrosis factor is therapeutic in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and promotes axon preservation and remyelination. Brain 2011, 134, 2736–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajant, H.; Siegmund, D. TNFR1 and TNFR2 in the Control of the Life and Death Balance of Macrophages. Front Cell Dev Biol 2019, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegoretti, V.; Baron, W.; Laman, J.D.; Eisel, U.L.M. Selective Modulation of TNF–TNFRs Signaling: Insights for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LProbert:, T.N.F.; its receptors in the, C.N.S. The essential, the desirable and the deleterious effects. Neuroscience 2015, 302, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hövelmeyer, N.; Hao, Z.; Kranidioti, K.; Kassiotis, G.; Buch, T.; Frommer, F.; von Hoch, L.; Kramer, D.; Minichiello, L.; Kollias, G.; Lassmann, H.; Waisman, A. Apoptosis of oligodendrocytes via Fas and TNF-R1 is a key event in the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2005, 175, 5875–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Muñoz, F.; García-Macedo, R.; Alarcón-Aguilar, F.; Cruz, M. Adipocinas, tejido adiposo y su relación con células del sistema inmune [Adipocitokines, adipose tissue and its relationship with immune system cells]. Gac Med Mex. 2005, 141, 505–512. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Lastra, G.; Manrique, C.M.; Hayden, M.R. The role of beta-cell dysfunction in the cardiometabolic syndrome. J Cardiometab Syndr 2006, 1, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brück, W. The pathology of multiple sclerosis is the result of focal inflammatory demyelination with axonal damage. J Neurol 2005, 252 (Suppl. S5), v3–v9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresegna, D.; Bullitta, S.; Musella, A.; Rizzo, F.R.; De Vito, F.; Guadalupi, L.; et al. Reexamining the role of TNF in MS pathogenesis and therapy. Cells 2020, 9, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharief, M.K.; Hentges, R. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha and disease progression in patients with multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 1991, 325, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.P.; Dendrou, C.A.; Attfield, K.E.; Haghikia, A.; Xifara, D.K.; Butter, F.; et al. TNF receptor 1 genetic risk mirrors outcome of anti-TNF therapy in multiple sclerosis. Nature 2012, 488, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, A.D.; Bethea, J.R.; Kerr, B.J. TNFa in MS and its animal models: implications for chronic pain in the disease. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 780876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oosten, B.W.; Barkhof, F.; Truyen, L.; Boringa, J.B.; Bertelsmann, F.W.; et al. Increased MRI activity and immune activation in two multiple sclerosis patients treated with the monoclonal antitumor necrosis factor antibody cA2. Neurology 1996, 47, 1531–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassiotis, G.; Kollias, G. Uncoupling the proinflammatory from the immunosuppressive properties of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) at the p55 TNF receptor level: implications for pathogenesis and therapy of autoimmune demyelination. J Exp Med 2001, 193, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeland, S.; Van Ryckeghem, S.; Van Imschoot, G.; et al. TNFR1 inhibition with a Nanobody protects against EAE development in mice. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 13646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, T.; Abe, Y.; Kamada, H.; Shibata, H.; Kayamuro, H.; Inoue, M.; et al. Therapeutic effect of PEGylated TNFR1-selective antagonistic mutant TNF in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. J Control Release 2011, 149, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.K.; Maier, O.; Fischer, R.; Fairless, R.; Hochmeister, S.; Stojic, A.; et al. Antibody-mediated inhibition of TNFR1 attenuates disease in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e90117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, F.; Williams, S.K.; John, K.; Huber, C.; Vaslin, C.; Zanker, H.; et al. The TNFR1 antagonist atrosimab is therapeutic in mouse models of acute and chronic inflammation. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 705485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, S.J.; Monson, N.L.; Davis, L.S. Seeking Balance: Potentiation and Inhibition of Multiple Sclerosis Autoimmune Responses by IL-6 and IL-10. Cytokine 2015, 73, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothaug, M.; Becker-Pauly, C.; Rose-John, S. The role of interleukin-6 signaling in nervous tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1863, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, E.S.; Lee, M.H.; Murphy, R.E.; Malloy, C.R. Pentose phosphate pathway activity parallels lipogenesis but not antioxidant processes in rat liver. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metab 2017, 314, E543–E551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugster, H.P.; et al. IL-6-deficient mice resist myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol 1998, 28, 2178–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, Y.; et al. IL-6-deficient mice are resistant to the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis provoked by myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Int Immunol 1998, 10, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Patel, K.D. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 release from IL-8-stimulated human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol 2005, 78, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straczkowski, M.; Dzienis-Straczkowska, S.; Stêpieñ, A.; Kowalska, I.; Szelachowska, M.; Kinalska, I. Plasma interleukin-8 concentrations are increased in obese subjects and related to fat mass and tumor necrosis factor-alpha system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002, 87, 4602–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makiel, Κ.; Suder, A.; Targosz, A.; Maciejczyk, Μ.; Alon Haim, A. Exercise-Induced Alternations of Adiponectin, Interleukin-8 and Indicators of Carbohydrate. Metabolism in males with metabolic syndrome. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matejčíkováa, Z.; Mareša, J.; Sládkováa, V.; Svrčinováa, T.; Vysloužilováa, J.; Zapletalováb, J.; Kaňovský, P. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum levels of interleukin-8 in patients with multiple sclerosis and its correlation with Q-albumin. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2017, 14, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, B.T.; Ashikian, N.; Ta, H.Q.; Chakryan, Y.; Manoukian, K.; Groshen, S.; Gilmore, W.; Cheema, G.S.; Stohl, W.; Burnett, M.E.; Ko, D.; Kachuck, N.J.; Weiner, L.P. 2004 Increased CXCL8 (IL-8) expression in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2004, 155, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuteboom, R.F.; Verbraak, E.; Voerman, J.S.; van Meurs, M.; Steegers, E.A.; de Groot, C.J.; Laman, J.D.; Hintzen, R.Q. First trimester interleukin 8 levels are associated with postpartum relapse in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2009, 15, 1356–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihim, S.A.; Abubakar, S.D.; Zian, Z.; Sasaki, T.; Saffarioun, M.; Maleknia, S.; Azizi, G. Interleukin-18 cytokine in immunity, inflammation, and autoimmunity: Biological role in induction, regulation, and treatment. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 919973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gris, D.; Ye, Z.; Iocca, H.A.; Wen, H.; Craven, R.R.; Gris, P.; et al. NLRP3 plays a critical role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by mediating Th1 and Th17 responses. J Immun 2010, 185, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, F.; Di-Marco, R.; Mangano, K.; Patti, F.; Reggio, E.; Nicoletti, A.; et al. Increased serum levels of interleukin-18 in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2001, 57, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chen, S.D.; Miao, L.; Liu, Z.G.; Li, W.; Zhao, Z.X.; et al. Serum levels of interleukin (IL)-18, IL-23 and IL-17 in Chinese patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2012, 243, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, F.D.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; Sarvetnick, N.; Ljunggren, H.G. IL-18 directs autoreactive T cells and promotes autodestruction in the central nervous system via induction of IFN-γ by NK cells. J Immun 2000, 165, 3099–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutcher, I.; Urich, E.; Wolter, K.; Prinz, M.; Becher, B. Interleukin 18–independent engagement of interleukin 18 receptor-α is required for autoimmune inflammation. Nat Immunol 2006, 7, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalor, S.J.; Dungan, L.S.; Sutton, C.E.; Basdeo, S.A.; Fletcher, J.M.; Mills, K.H. Caspase-1-processed cytokines IL-1beta and IL-18 promote IL-17 production by gammadelta and CD4 T cells that mediate autoimmunity. J Immun 2011, 186, 5738–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.I.; Dodelet-Devillers, A.; Kebir, H.; Ifergan, I.; Fabre, P.J.; Terouz, S.; et al. The hedgehog pathway promotes blood-brain barrier integrity and CNS immune quiescence. Science 2011, 334, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendrou, C.A.; Fugger, L.; Friese, M.A. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, W.; Shinohara, M.L. Inflammasome activation inmultiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Brain Pathology 2017, 27, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.C.; Bradstreet, T.R.; Schwarzkopf, E.A.; Jarjour, N.N.; Chou, C.; Archambault, A.S.; et al. IL-1-induced Bhlhe40 identifies pathogenic T helper cells in a model of autoimmune neuroinflammation. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2016, 213, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffenbauer, J.; Streit, W.J.; Butfiloski, E.; LaBow, M.; Edwards, C., III; Moldawer, L.L. The induction of EAE is only partially dependent on TNF receptor signaling but requires the IL-1 type I receptor. Clinical Immunology 2000, 95, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer SS, Cheng G: Role of Interleukin 10 Transcriptional Regulation in Inflammation and Autoimmune Disease. Crit Rev Immunol 2012, 32, 23–63. [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.W.; et al. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol 2001, 19, 683–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugbee, E.; Wang, A.A.; Gommerman, J.L. Under the influence: environmental factors as modulators of neuroinflammation through the IL-10/iL-10R axis. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1188750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettelli, E.; et al. IL-10 is critical in the regulation of autoimmune encephalomyelitis as demonstrated by studies of IL-10- and IL-4-deficient and transgenic mice. J Immunol 1998, 161, 3299–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoilova, E.B.; Horton, J.L.; Chen, Y. Acceleration of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in interleukin-10-deficient mice: roles of interleukin-10 in disease progression and recovery. Cell Immunol 1998, 188, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Chen, C.; Shi, G.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Fan, N.; Yang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, T. Therapeutic potential of the target on NLRP3 inflammasome in multiple sclerosis. Pharmacol Ther 2021, 227, 107880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindarajan, V.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P.; Keane, R.W. Role of inflammasomes in multiple sclerosis and their potential as therapeutic targets. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, N.; L’homme, L.; De Roover, A.; Kohnen, L.; Scheen, A.J.; Moutschen, M.; Piette, J.; Legrand-Poels, S.; Paquot, N. Obesity phenotype is related to nlrp3 inflammasome activity and immunological profile of visceral adipose tissue. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 2487–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandanmagsar, B.; Youm, Y.-H.; Ravussin, A.; Galgani, J.E.; Stadler, K.; Mynatt, R.L.; Ravussin, E.; Stephens, J.M.; Dixit, V.D. The nlrp3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Gris, D.; Lei, Y.; Jha, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, M.T.-H.; Brickey, W.J.; Ting, J.P. Fatty acid–induced nlrp3-asc inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol 2011, 12, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng X, Zhu M, Liu X, Chen X, Yuan Y, Li L, Liu J, Lu Y, Cheng J, Chen, Y; et al. Oleic acid ameliorates palmitic acid induced hepatocellular lipotoxicity by inhibition of er stress and pyroptosis. Nutr Metab 2020, 17, 1–14.

- Yan, Y.; Jiang, W.; Spinetti, T.; Tardivel, A.; Castillo, R.; Bourquin, C.; Guarda, G.; Tian, Z.; Tschopp, J.; Zhou, R.; et al. Omega-3 fatty acids prevent inflammation and metabolic disorder through inhibition of nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 2013, 38, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duewell, P.; Kono, H.; Rayner, K.J.; Sirois, C.M.; Vladimer, G.; Bauernfeind, F.G.; Abela, G.S.; Franchi, L.; Nuñez, G.; Schnurr, M.; et al. Nlrp3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 2010, 464, 1357–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheedy, F.J.; Grebe, A.; Rayner, K.J.; Kalantari, P.; Ramkhelawon, B.; Carpenter, S.B.; Becker, C.E.; Ediriweera, H.N.; Mullick, A.E.; Golenbock, D.T.; et al. Cd36 coordinates nlrp3 inflammasome activation by facilitating intracellular nucleation of soluble ligands into particulate ligands in sterile inflammation. Nat Immunol 2013, 14, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenen, T.B.; Stienstra, R.; Van Tits, L.J.; De Graaf, J.; Stalenhoef, A.F.; Joosten, L.A.; Tack, C.J.; Netea, M.G. Hyperglycemia activates caspase-1 and TXNIP-mediated IL-1beta transcription in human adipose tissue. Diabetes 2011, 60, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-J.; Han, A.R.; Kim, E.-A.; Yang, J.W.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Na, J.-M.; Cho, S.-W. Khg21834 attenuates glutamate-induced mitochondrial damage apoptosis nlrp3 inflammasome activation in sh-sy5y human neuroblastoma cells. Eur, J. Pharmacol. 2019, 856, 172412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D.; Amar, J.; Iglesias, M.A.; Poggi, M.; Knauf, C.; Bastelica, D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.M.; Chabo, C.; et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2007, 2007, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, X.; Ghani, A.; Malik, A.; Wilder, T.; Colegio, O.R.; Flavell, R.A.; Cronstein, B.N.; Mehal, W.Z. Adenosine is required for sustained inflammasome activation via the a 2a receptor and the hif-1α pathway. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, R.; Dietrich, W.; de Rivero Vaccari, J. Inflammasome proteins as biomarkers of multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol 2018, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voet, S.; Mc Guire, C.; Hagemeyer, N.; Martens, A.; Schroeder, A.; Wieghofer, P.; et al. A 20 critically controls microglia activation and inhibits inflammasome-dependent neuroinflammation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, P.; Shao, B.-Z.; Xu, Z.-Q.; Chen, X.-W.; Wei, W.; Liu, C. Activating a7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome through regulation of b-arrestin-1. CNS Neurosci Ther 2017, 23, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, M.; Williams, K.L.; Gunn, M.D.; Shinohara, M.L. NLRP3 inflammasome induces chemotactic immune cell migration to the CNSin experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci, U.S.A. 2012, 109, 10480–10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Lv, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, L. The autoimmune encephalitis-related cytokine TSLP in the brain primes neuroinflammation by activating the JAK2-NLRP3 axis. Clin Exp Immunol 2021, 207, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörmannsperger, G.; Haller, D. Molecular crosstalk of probiotic bacteria with the intestinal immune system: clinical relevance in the context of inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Med Microbiol 2010, 300, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, F.; Shi, M.; Lang, Y.; Shen, D.; Jin, T.; Zhu, J.; Cui, L. Gut microbiota in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: Current applications and future perspectives. Mediat Inflamm 2018, 2018, 8168717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, N.; Fernández-Rilo, A.C.; Palomba, L.; Di Marzo, V.; Cristino, L. Obesity Affects the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and the Regulation Thereof by Endocannabinoids and Related Mediators. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Possemiers, S.; Van de Wiele, T.; Guiot, Y.; Everard, A.; Rottier, O.; et al. Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2- driven improvement of gut permeability. Gut 2009, 58, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, S.; Haghikia, A.; Wilck, N.; Müller, D.N.; Linker, R.A. Impacts of microbiome metabolites on immune regulation and autoimmunity. Immunology 2018, 154, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esplugues, E.; Huber, S.; Gagliani, N.; Hauser, A.E.; Town, T.; Wan, Y.Y.; et al. Control of TH17 cells occurs in the small intestine. Nature 2011, 475, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremlett, H.; Bauer, K.C.; Appel-Cresswell, S.; Finlay, B.B.; Waubant, E. The gut microbiome in human neurological disease: A review. Ann Neurol 2017, 81, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscarinu, M.C.; Cerasoli, B.; Annibali, V.; Policano, C.; Lionetto, L.; Capi, M.; Mechelli, R.; Romano, S.; Fornasiero, A.; Mattei, G. Altered intestinal permeability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Mult Sclerosis 2017, 23, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, P.A.; Kleerebezem, M.; Brummer, R.J.; Cani, P.D.; Mercenier, A.; MacDonald, T.T.; Garcia-Rodenas, C.L.; Wells, J.M. Can probiotics modulate human disease by impacting intestinal barrier function? B J Nutr 2017, 117, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duscha, A.; Gisevius, B.; Hirschberg, S.; Yissachar, N.; Stangl, G.I.; Eilers, E.; Bader, V.; Haase, S.; Kaisler, J.; David, C.; et al. Propionic Acid Shapes the Multiple Sclerosis Disease Course by an Immunomodulatory Mechanism. Cell 2020, 180, 1067–1080.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naomi, R.; Teoh, S.H.; Embong, H.; Balan, S.S.; Othman, F.; Bahari, H.; Yazid, M.D. The Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Obesity and Its Impact on Cognitive Impairments—A Narrative Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzio, G.; Barrera, G.; Pizzimenti, S. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs) and Oxidative Stress in Physiological Conditions and in Cancer. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turrens, J.F. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol 2003, 552, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirichen, H.; Yaigoub, H.; Xu, W.; Wu, C.; Li, R.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Contribution in Chronic Kidney Disease Progression Through Oxidative Stress. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 627837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krementsov, D.N.; Thornton, T.M.; Teuscher, C.; Rincon, M. The Emerging Role of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase in Multiple Sclerosis and Its Models. Mol Cell Biol 2013, 33, 3728–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Stone, S.; Lin, W. Role of nuclear factor κB in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Neural Regen Res 2018, 13, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Upadhayay, S.; Mehan, S. Understanding Abnormal c-JNK/p38MAPK Signaling Overactivation Involved in the Progression of Multiple Sclerosis: Possible Therapeutic Targets and Impact on Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurotox Res 2021, 39, 1630–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, E.; Mychasiuk, R.; Hibbs, M.L.; Semple, B.D. Dysregulated phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling in microglia: shaping chronic neuroinfammation. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, G.G.; et al. Immunology and oxidative stress in multiple sclerosis: clinical and basic approach. Clin Dev Immunol 2013, 2013, 708659. [Google Scholar]

- Ohl, K.; Tenbrock, K.; Kipp, M. Oxidative stress in multiple sclerosis: central and peripheral mode of action. Exp Neurol 2016, 277, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, R.; Jeong, N.Y. Potential for therapeutic use of hydrogen sulfide in oxidative stress-induced neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Med Sci 2019, 16, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, J.M.; et al. Therapeutic potential of curcumin for multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 2018, 39, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadidi-Niaragh, F.; Mirshafiey, A. Th17 cell the new player of neuroinflammatory process in multiple sclerosis Scand. J. Immunol. 2011, 74, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Uttara, B.; et al. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr Neuropharmacol 2009, 7, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Z.; et al. Potential utility of natural products against oxidative stress in animal models of multiple sclerosis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Hu, B.; Zang, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H. Nrf2 drives oxidative stress-induced autophagy in nucleus pulposus cells via a Keap1/Nrf2/p62 feedback loop to protect intervertebral disc from degeneration. Cell Death & Disease 2019, 10, 510. [Google Scholar]

- Emamgholipour, S.; Hossein-Nezhad, A.; Sahraian, M.A.; Askarisadr, F.; Ansari, M. Expression and enzyme activity of MnSOD and catalase in peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from multiple sclerosis patients. Arch Med Lab Sci. 2015, 1, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo, F.; et al. After cellular internalization, quercetin causes Nrf2 nuclear translocation, increases glutathione levels, and prevents neuronal death against an oxidative insult. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010, 49, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Gold, R.; Linker, R.A. Mechanisms of oxidative damage in multiple sclerosis and neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic modulation via fumaric acid esters. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, 11783–11803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; et al. Neuroprotection against oxidative stress: phytochemicals targeting TrkB signaling and the Nrf2-ARE antioxidant system. Front Mol Neurosci 2020, 13, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lü, J.-M.; Lin, P.H.; Yao, Q.; Chen, C. Chemical and molecular mechanisms of antioxidants: experimental approaches and model systems. J Cell Mol Med 2009, 14, 840–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E.; Kemp, K.; Hares, K.; Redondo, J.; Rice, C.; Scolding, N.; Wilkins, A. Increased microglial catalase activity in multiple sclerosis grey matter. Brain Res 2014, 1559, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovic, D.; Andjelic, T.; Ninkovic, M.; Dejanovic, B.; Kotur-Stevuljevic, J. Superoxide dismutase (SOD), advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP), and disease-modifying treatment are related to better relapse recovery after corticosteroid treatment in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 2021, 42, 3241–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salekzamani, S.; Pakkhesal, S.; Babaei, M.; Mirzaaghazadeh, E.; Mosaddeghi-Heris, R.; Talebi, M.; Sanaie, S.; Naseri, A. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation in multiple sclerosis; a systematic review. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2024, 2024, 106212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varra, F.N.; Gkouzgos, S.; Varras, M.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P. Efficacy of antioxidant compounds in obesity and its associated comorbidities. Pharmakeftiki 2024, 36, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Theodosis-Nobelos, P.; Rekka, E.A. The Multiple Sclerosis Modulatory Potential of Natural Multi-Targeting Antioxidants. Molecules 2022, 27, 8402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luís, J.P.; Simões, C.J.V.; Brito, R.M.M. The Therapeutic Prospects of Targeting IL-1R1 for the Modulation of Neuroinflammation in Central Nervous System Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Park, J.; Kim, M.; Scherer, P.E. Endotrophin, a multifaceted player in metabolic dysregulation and cancer progression, is a predictive biomarker for the response to PPAR agonist treatment. Diabetologia 2016, 60, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuncha, T.; Thunapong, W.; Yasom, S.; Wanchai, K.; Eaimworawuthikul, S.; Metzler, G.; Lungkaphin, A.; Pongchaidecha, A.; Sirilun, S.; Chaiyasut, C.; et al. Decreased Microglial Activation Through Gut-brain Axis by Prebiotics Probiotics or Synbiotics Effectively Restored Cognitive Function in Obese-insulin Resistant Rats, J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Zeng, X.; Tan, F.; Yi, R.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Mu, J.; Zhao, X. Lactobacillus plantarum KFY04 prevents obesity in mice through the PPAR pathway and alleviates oxidative damage and inflammation. Food Funct 2020, 11, 5460–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani, A.; Cross, A.H.; Stuve, O. Exploring the association between weight loss-inducing medications and multiple sclerosis: insights from the FDA adverse event reporting system database. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2024, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sîrbe, C.; Rednic, S.; Grama, A.; Pop, T.L. An Update on the Effects of Vitamin D on the Immune System and Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Du, S.; Zhao, L.; Jain, S.; Sahay, K.; Rizvanov, A.; et al. Autoreactive lymphocytes in multiple sclerosis: Pathogenesis and treatment target. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 996469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berer, A.; Stöckl, J.; Majdic, O.; Wagner, T.; Kollars, M.; Lechner, K.; et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits dendritic cell differentiation and maturation in vitro. Exp. Hematol. 2000, 28, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan, M.; Good, M.; Jay KKolls, J.K. Regulation of Dendritic Cell Function by Vitamin D. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8127–8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuyts, A.H.; Lee, W.P.; Bashir-Dar, R.; Berneman, Z.N.; Cools, N. Dendritic cells in multiple sclerosis: key players in the immunopathogenesis, key players for new cellular immunotherapies? Mult Scler 2013, 19, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashold, F.E.; Miller, D.J.; Hayes, C.E. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatment decreases macrophage accumulation in the CNS of mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 2000, 103, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koduah, P.; Paul, F.; Dörr, J.-M. Vitamin D in the prevention, prediction and treatment of neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory diseases. EPMA J 2017, 8, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzella-Pezavento, S.F.G.; Mimura, L.A.N.; Fraga-Silva, T.F.C.; Ishikawa, L.L.W.; França, T.G.D.; Sartori, A. Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Is Successfully Controlled by Epicutaneous Administration of MOG Plus Vitamin D Analog. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savran, Z.; Baltaci, S.B.; Aladag, T.; Mogulkoc, R.; Baltaci, A.K. Vitamin D and Neurodegenerative Diseases Such as Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s Disease (PD), Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): A Review of Current Literature. Curr Nutr Rep 2025, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, A.S.; Spagnol, G.S.; Bordeaux-Rego, P.; Oliveira, C.O.F.; Fontana, A.G.M.; de Paula, R.F.O.; et al. Vitamin D3 induces IDO+ tolerogenic DCs and enhances Treg, reducing the severity of EAE. CNS Neurosci Ther 2013, 19, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.Y. Regulatory T cells: immune suppression and beyond. Cell Mol Immunol 2010, 7, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewison, M. Vitamin D and the immune system: new perspectives on an old theme. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2010, 39, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenercioglu, A.K. The Anti-Inflammatory Roles of Vitamin D for Improving Human Health. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 13514–13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirarchi, A.; Albi, E.; Beccari, T.; Cataldo Arcuri, C. Microglia and Brain Disorders: The Role of Vitamin D and Its Receptor. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 11892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dursun, E.; Gezen-Ak, D.; Yilmazer, S. The Influence of Vitamin D Treatment on the Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (INOS) Expression in Primary Hippocampal Neurons. Noro Psikiyatr Ars 2014, 51, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galoppin, M.; Kari, S.; Soldati, S.; Pal, A.; Rival, M.; Engelhardt, B.; et al. Full spectrum of vitamin D immunomodulation in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Brain Commun 2022, 4, fcac171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; Lassmann, H. The role of nitric oxide in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2002, 1, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintzel, M.B.; Rametta, M.; Reder, A.T. Vitamin D and Multiple Sclerosis: A Comprehensive Review. Neurol Ther 2017, 7, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassard, S.D.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Qian, P.; Emrich, S.A.; Azevedo, C.J.; Goodman, A.D.; et al. High-dose vitamin D3 supplementation in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised clinical trial. EclinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnik, D.; Rabinski, T.; Halfon, A.; Anzi, S.; Plaschkes, I.; Benyamini, H.; et al. P450 oxidoreductase regulates barrier maturation by mediating retinoic acid metabolism in a model of the human BBB. Stem Cell Reports 2022, 17, 2050–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryka-Marton, M.; Grabowska, A.D.; Szukiewicz, D. Breaking the Barrier: The Role of Proinflammatory Cytokines in BBB Dysfunction. Int. J Mole Sci 2015, 26, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschuck, J.; Nair, V.P.; Galhoz, A.; Zaratiegui, C.; Tai, H.-M.; Ciceri, G.; et al. Suppression of ferroptosis by vitamin A or radical-trapping antioxidants is essential for neuronal development. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 7611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Drew, P.D. 9-Cis-retinoic acid suppresses inflammatory responses of microglia and astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2005, 171, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtal, K.A.; Wolfram, L.; Frey-Wagner, I.; Lang, S.; Scharl, M.; Vavricka, S.R.; et al. The effects of vitamin A on cells of innate immunity in vitro. Toxicol in vitro 2013, 27, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Gupta, P.; Saini, A.S.; Kaushali, C.; Sharma, S. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor: A family of nuclear receptors role in various diseases. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2011, 2, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorosty-Motlagh, A.R.; Honarvar, M.N.; Sedighiyan, M.; Abdolahi, M. The molecular mechanisms of vitamin A deficiency in multiple sclerosis. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2016, 60, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raverdeau, M.; Breen, C.J.; Misiak, A.; Mills, K.H. Retinoic acid suppresses IL-17productionandpathogenic activity of γδT-cells in CNS autoimmunity. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2016, 94, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.; Markiewicz, Ł.; Kabziński, J.; Odrobina, D.; Majsterek, I. Potential of redox therapies in neuro-degenerative disorders. Front. Biosci. 2017, 9, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, S.; Mancuso, C.; Koverech, G.; Di Mauro, P.; Ontario, M.L.; Petralia, C.C.; Petralia, A.; Maiolino, L.; Serra, A.; Calabrese, E.J.; et al. Heat shock proteins and hormesis in the diagnosis and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Immun. Ageing 2015, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Guo, T.; Qi, W.; Li, Y.; Gu, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Curcumin ameliorates ischemic stroke injury in rats by protecting the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. Exp Ther Med 2021, 22, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motavaf, M.; Sadeghizadeh, M.; Babashah, S.; Zare, L.; Javan, M. Dendrosomal nanocurcumin promotes remyelination through induction of oligodendrogenesis in experimental demyelination animal model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2020, 14, 1449–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldoveanu, C.-A.; Tomoaia-Cotisel, M.; Sevastre-Berghian, A.; Tomoaia, G.; Mocanu, A.; Pal-Racz, C.; Toma, V.-A.; Roman, I.; Ujica, M.-A.; Pop, L.-C. A Review on Current Aspects of Curcumin-Based Effects in Relation to Neurodegenerative, Neuroinflammatory and Cerebrovascular Diseases. Molecules 2025, 30, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, E.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Chin, S.; Sureshbabu, A.; Karthikeyan, A.; Do, K.; et al. A Review of the Role of Curcumin in Metal Induced Toxicity. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Gupta, S.C.; Sung, B. Curcumin: an orally bioavailable blocker of TNF and other pro-inflammatory biomarkers. Br J Pharmacol 2013, 169, 1672–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, Y.; Zamani, A.R.N.; Majidi, Z.; Sharafkandi, Ν.; Alizadeh, S.; Amir MEMofrad, A.M.E.; et al. Curcumin and targeting of molecular and metabolic pathways in multiple sclerosis. Cell Biochem Funct 2023, 41, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, Y.; Yi, X.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, S.; Li, Z.; Ni, J.; Song, Z. Curcumin inhibiting Th17 cell differentiation by regulating the metabotropic glutamate receptor-4 expression on dendritic cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2017, 46, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolati, S.; Babaloo, Z.; Ayromlou, H.; Ahmadi, M.; Rikhtegar, R.; Rostamzadeh, D.; et al. Nanocurcumin improves regulatory T-cell frequency and function in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2019, 327, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buc, M. Role of regulatory T cells in pathogenesis and biological therapy of multiple sclerosis. Mediators Inflamm 2013, 2013, 963748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.D.; Dziedzic, A.; Saluk-Bijak, J.; Bijak, M. A Review of Various Antioxidant Compounds and their Potential Utility as Complementary Therapy in Multiple Sclerosis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzerova, E.; Danhauser, K.; Haack, T.B.; Kremer, L.S.; Melcher, M.; Ingold, I.; et al. Human thioredoxin 2 deficiency impairs mitochondrial redox homeostasis and causes early-onset neurodegeneration. Brain 2016, 139, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, S.-P.; Fu, J.-S.; Zhang, S.; Bai, L.; Guo, L. Resveratrol defends blood-brain barrier integrity in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. J Neurophysiol 2016, 116, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindler, K.S.; Ventura, E.; Dutt, M.; Elliott, P.; Fitzgerald, D.C.; Rostami, A. Oral resveratrol reduces neuronal damage in a model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2010, 30, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianchecchi, E.; Fierabracci, A. Insights on the Effects of Resveratrol and Some of Its Derivatives in Cancer and Autoimmunity: A Molecule with a Dual Activity. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanbakht, P.; Yazdi, F.R.; Taghizadeh, F.; Khadivi, F.; Hamidabadi, H.G.; Kashani, I.R.; et al. Quercetin as a possible complementary therapy in multiple sclerosis: Anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and remyelination potential properties. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).