Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We propose an end-to-end edge–cloud–blockchain system for SLMT.

- We evaluate our proposed system in comparison with the most used Encoder-Decoder Transformer using the largest publicly available German sign language dataset, PHOENIX14T, and our new MedASL dataset.

- We conduct experiments and numerical analysis of our system’s performance in terms of Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU), Recall Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation (ROUGE), training time, translation time, and overall end-to-end system time.

- We deploy the Encoder-Decoder Transformer and ADAT models in a unified setup, demonstrating the feasibility of our proposed system for real-world applications.

2. Related Work

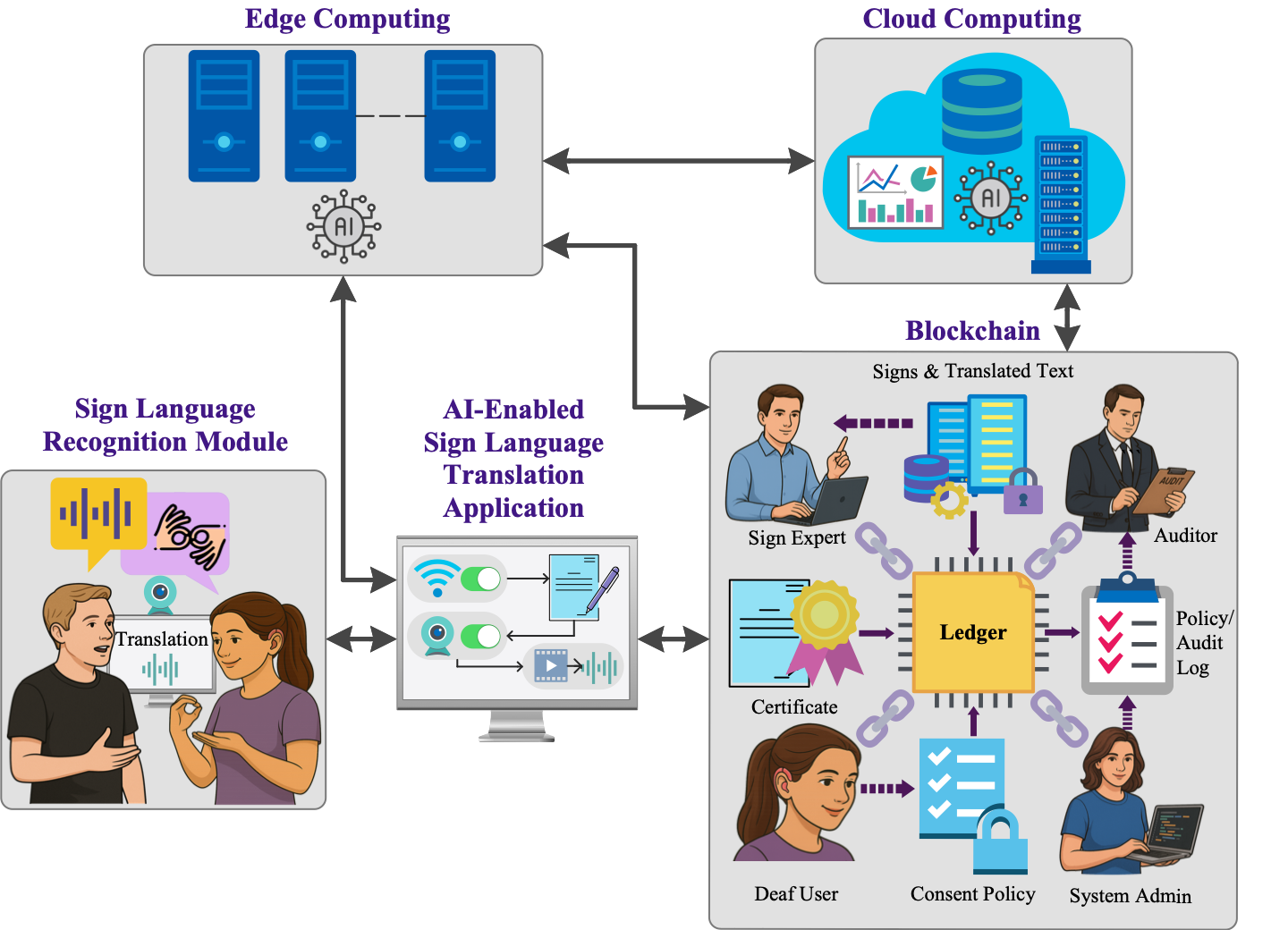

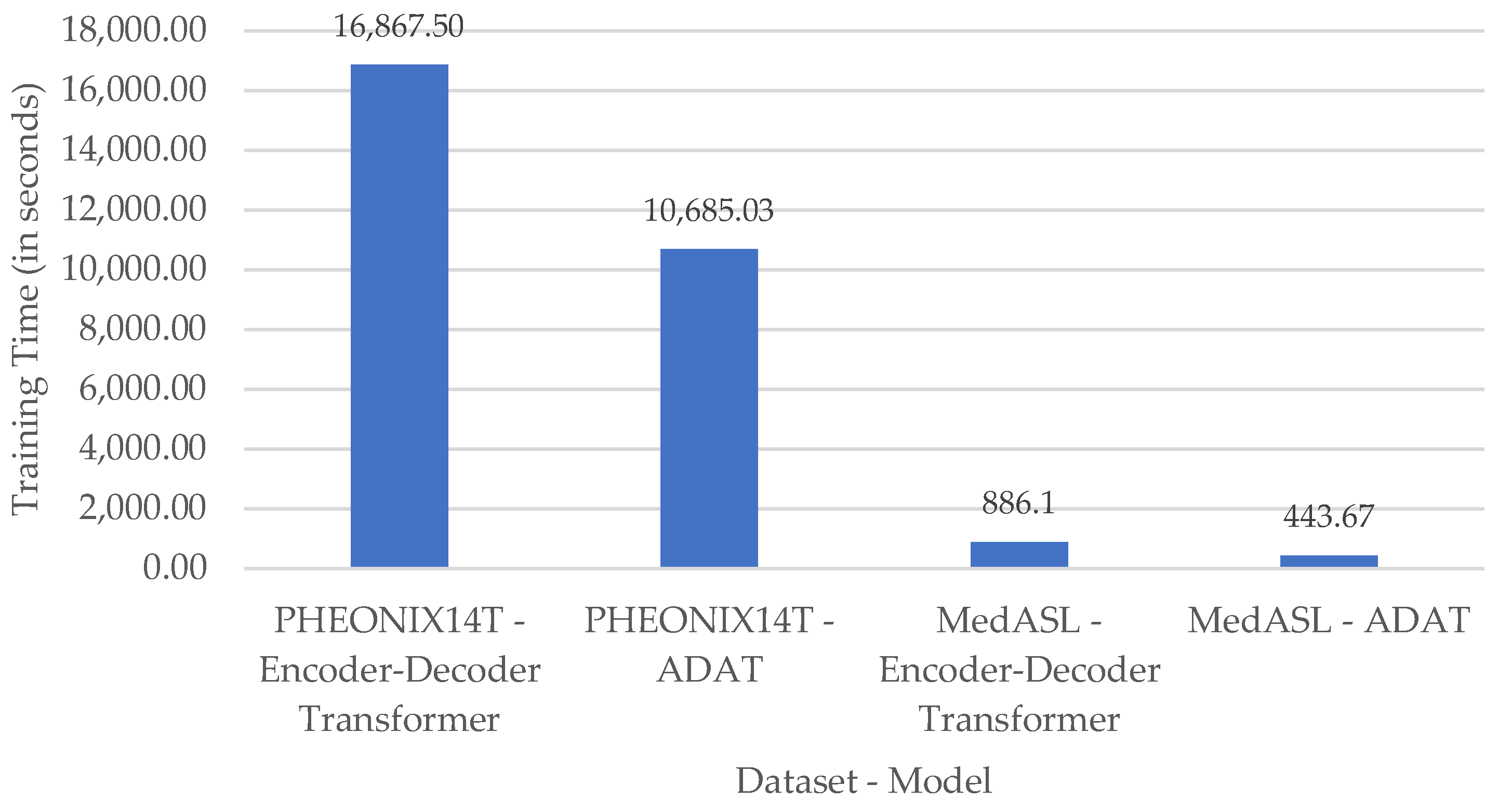

3. Proposed End-to-End System for Sign Language Translation

3.1. Sign Language Recognition Module

- Device computation: CPU, GPU, and RAM capacities determine the feasibility of capturing frames, extracting keypoints, and performing inference [40].

- Operating System (OS): The OS manages camera access, hardware accelerators, security, and user experience. User-driven access controls reduce unauthorized access. Hardware accelerators determine the feasibility of keypoint extraction and inference. Security policies enforce user privacy and implement tamper-evident safeguards, including integrity checks and tamper detection modules [43]. Permissions for camera, network, and storage are tied to user consent, ensuring legal compliance [44].

3.2. AI-Enabled Sign Language Translation Application

3.3. Edge Computing

3.4. Cloud Computing

3.5. Blockchain

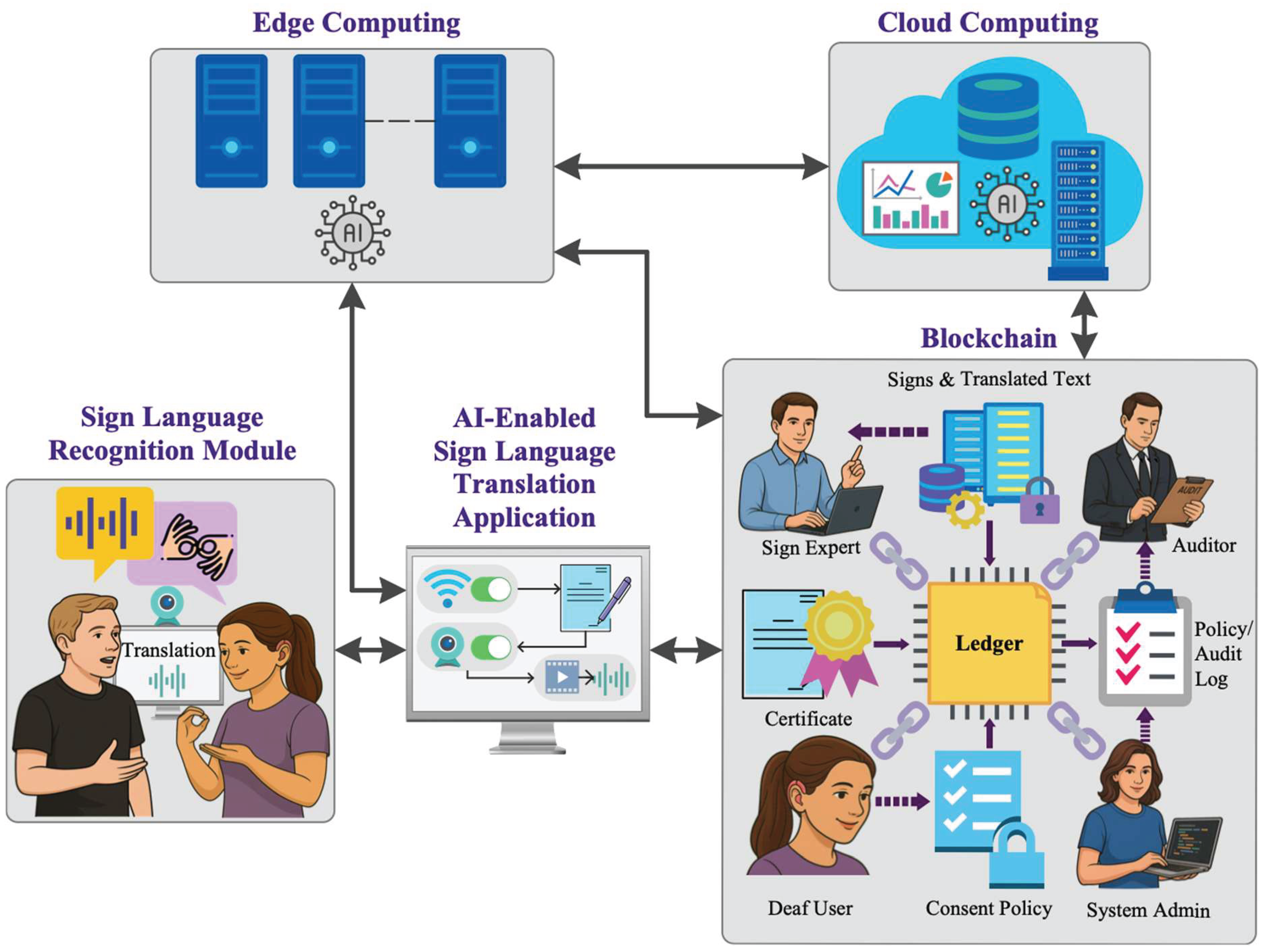

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Data Preprocessing

4.3. Model Development

4.3.1. Encoder-Decoder Transformer

4.3.2. Adaptive Transformer (ADAT)

4.4. Experimental Setup

4.5. Experiments

5. Performance Evaluation

5.1. Evaluation Metrics

5.1.1. Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU)

5.1.2. Recall Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation (ROUGE)

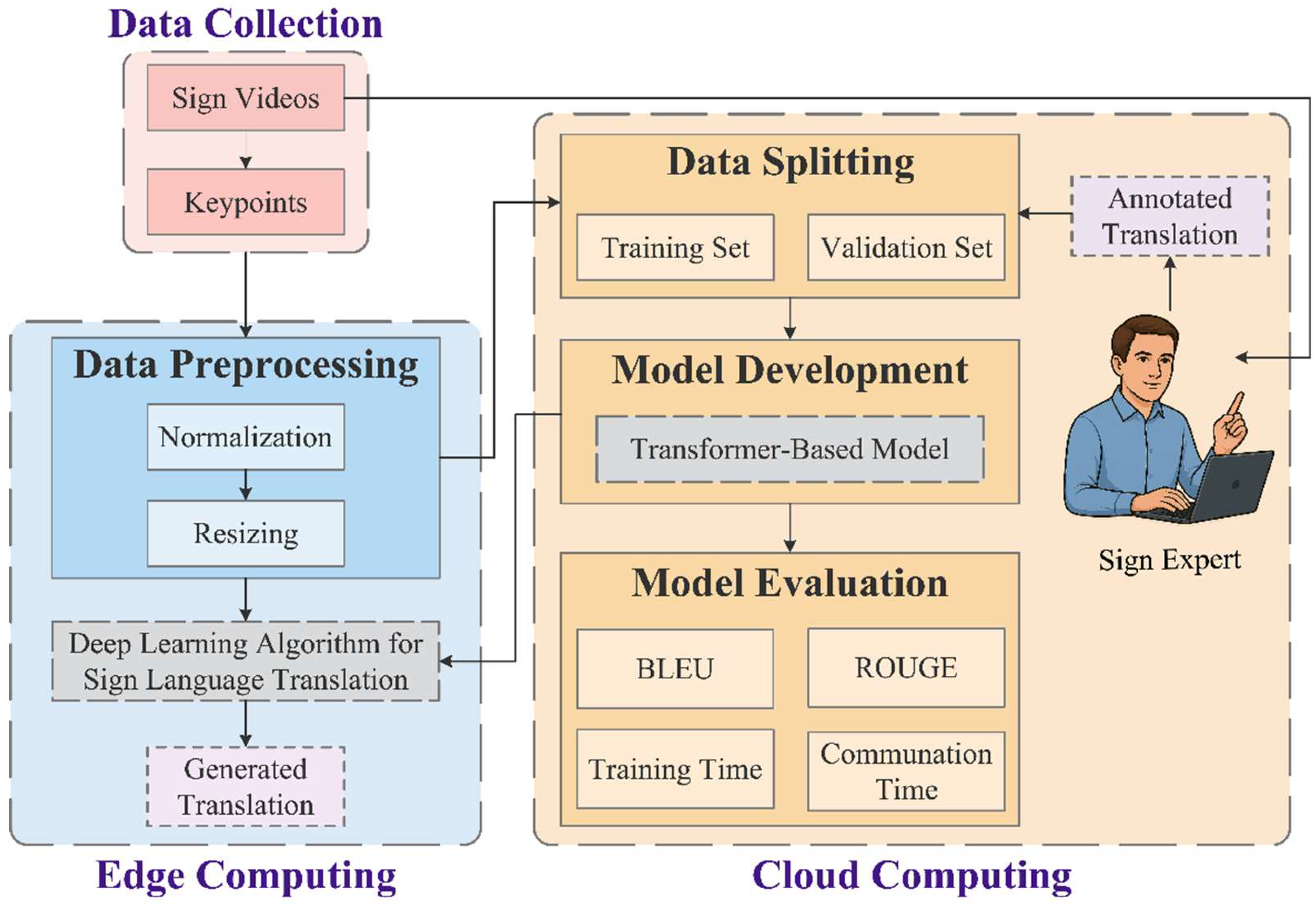

5.1.3. Runtime Efficiency

5.2. Hyperparameter Tuning

5.3. Hardware Specifications

5.4. Experimental Results Analysis

5.4.1. Translation Quality

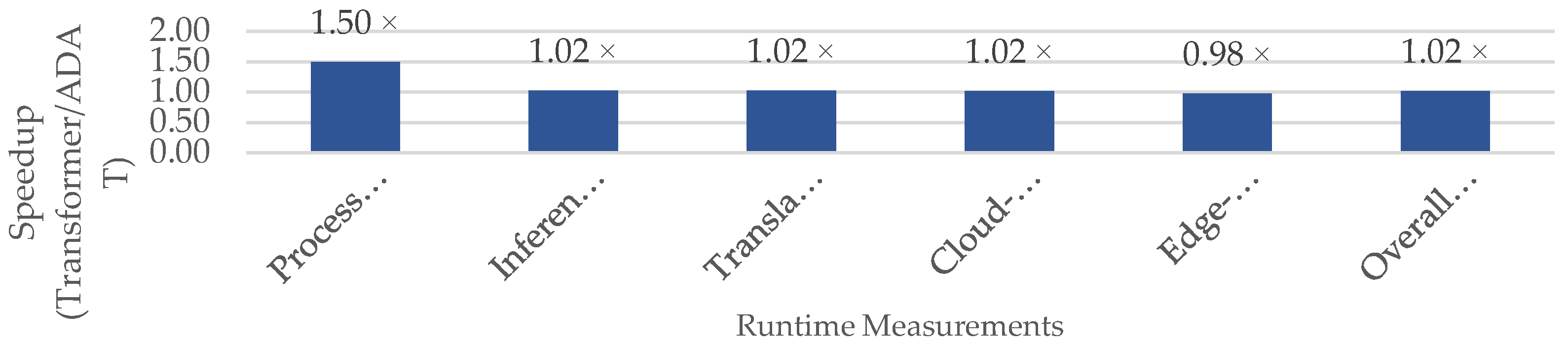

5.4.2. Runtime Efficiency

6. Responsible Deployment of the Proposed System

6.1. Ethical, Legal, and Data Rights Considerations

6.2. Security Threats and Mitigations

6.3. Minimum Requirements for Sign Language Translation System Deployment

- Translation quality must be sufficient to support transparent and precise communication between DHH individuals and the broader society. Section 5.1 shows that ADAT consistently outperforms the Encoder-Decoder Transformer across all metrics, demonstrating the feasibility of achieving precise translation.

- Latency must be minimized to ensure an efficient end-to-end translation. Section 5.2 demonstrates ADAT’s reductions in inference and communication times in the edge–cloud setup.

- Generalization across signers and environmental conditions is essential to ensure inclusivity. Achieving this requires continuous data collection from different signers, domains, and environments to improve robustness.

- Data collection and model retraining must comply with international and national regulations, such as GDPR [20] and UAE PDPL [21]. These principles ensure that users have control over their data, can withdraw their consent, and determine how their data is used. The blockchain-based logging mechanism described in Section 3.5 provides a solid foundation for meeting these obligations and ensuring accountability.

- Security and robustness are critical for reliable deployment. As discussed in Section 6.2, safeguards against video tampering and unauthorized access must be integrated into the system design.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Ageing and Health Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf Registry Available online:. Available online: https://rid.org (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Kaula, L.T.; Sati, W.O. Shaping a Resilient Future: Perspectives of Sign Language Interpreters and Deaf Community in Africa. Journal of Interpretation 2025, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, L.; Zhang, L. Information Innovation Technology in Smart Cities, 2018.

- Shahin, N.; Watfa, M. Deaf and Hard of Hearing in the United Arab Emirates Interacting with Alexa, an Intelligent Personal Assistant. Technol Disabil 2020, 32, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, N.; Ismail, L. From Rule-Based Models to Deep Learning Transformers Architectures for Natural Language Processing and Sign Language Translation Systems: Survey, Taxonomy and Performance Evaluation. Artif Intell Rev 2024, 57, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin, E. The Importance of Medical Interpreters. American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal 2017, 12, 13–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Co, J.; Zhang, M. DeepASL: Enabling Ubiquitous and Non-Intrusive Word and Sentence-Level Sign Language Translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Embedded Network Sensor Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, November 6, 2017; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- S Kumar, S.; Wangyal, T.; Saboo, V.; Srinath, R. Time Series Neural Networks for Real Time Sign Language Translation. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA); IEEE, December 2018; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanawansa, I.D.V.J.; Rajakaruna, R.M.T.P. Sinhala Sign Language Interpreter Optimized for Real – Time Implementation on a Mobile Device. In Proceedings of the 2021 10th International Conference on Information and Automation for Sustainability (ICIAfS); IEEE, August 11 2021; pp. 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, S.; Yin, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Xie, L.; Lu, S. Towards Real-Time Sign Language Recognition and Translation on Edge Devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia; ACM: New York, NY, USA, October 26, 2023; pp. 4502–4512. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Müller, M.; Sennrich, R. SLTUNET: A Simple Unified Model for Sign Language Translation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Hasan, Md.A.M.; Tomioka, Y.; Shin, J. Hand Gesture Recognition for Multi-Culture Sign Language Using Graph and General Deep Learning Network. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society 2024, 5, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Miah, A.S.M.; Akiba, Y.; Hirooka, K.; Hassan, N.; Hwang, Y.S. Korean Sign Language Alphabet Recognition Through the Integration of Handcrafted and Deep Learning-Based Two-Stream Feature Extraction Approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 68303–68318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baihan, A.; Alutaibi, A.I.; Alshehri, M.; Sharma, S.K. Sign Language Recognition Using Modified Deep Learning Network and Hybrid Optimization: A Hybrid Optimizer (HO) Based Optimized CNNSa-LSTM Approach. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 26111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chouvatut, V. Video-Based Sign Language Recognition via ResNet and LSTM Network. J Imaging 2024, 10, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Hu, H.; Ma, G.-F. Part-Wise Graph Fourier Learning for Skeleton-Based Continuous Sign Language Recognition. J Imaging 2025, 11, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, L.; Shahin, N.; Tesfaye, H.; Hennebelle, A. VisioSLR: A Vision Data-Driven Framework for Sign Language Video Recognition and Performance Evaluation on Fine-Tuned YOLO Models. Procedia Comput Sci 2025, 257, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, L.; Materwala, H.; Hennebelle, A. A Scoping Review of Integrated Blockchain-Cloud (BcC) Architecture for Healthcare: Applications, Challenges and Solutions. Sensors 2021, 21, 3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. General Data Protection Regulation GDPR, 2018.

- Government of United Arab Emirates, Federal Decree by Law No.(45) of 2021 Concerning the Protection of Personal Data. 2021.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, N.; Ismail, L. ADAT: Time-Series-Aware Adaptive Transformer Architecture for Sign Language Translation. ArXiv 2025.

- Camgoz, N.C.; Hadfield, S.; Koller, O.; Ney, H.; Bowden, R. Neural Sign Language Translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR).

- Kwak, J.; Sung, Y. Automatic 3D Landmark Extraction System Based on an Encoder–Decoder Using Fusion of Vision and LiDAR. Remote Sens (Basel) 2020, 12, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Bian, J.-W.; Gu, Y.-C.; Cheng, M.-M. MobileSal: Extremely Efficient RGB-D Salient Object Detection. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2022, 44, 10261–10269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Climent-Pérez, P.; Florez-Revuelta, F. Protection of Visual Privacy in Videos Acquired with RGB Cameras for Active and Assisted Living Applications. Multimed Tools Appl 2021, 80, 23649–23664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Morerio, P.; Del Bue, A. Event Anonymization: Privacy-Preserving Person Re-Identification and Pose Estimation in Event-Based Vision. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 66964–66980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materwala, H.; Ismail, L.; Shubair, R.M.; Buyya, R. Energy-SLA-Aware Genetic Algorithm for Edge–Cloud Integrated Computation Offloading in Vehicular Networks. Future Generation Computer Systems 2022, 135, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Environment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2008 9th ACIS International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking, and Parallel/Distributed Computing.

- Ismail, L.; Materwala, H.; Khan, M.A. Performance Evaluation of a Patient-Centric Blockchain-Based Healthcare Records Management Framework. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Electronics Communication Conference.

- Satvat, K.; Shirvanian, M.; Hosseini, M.; Saxena, N. CREPE: A Privacy-Enhanced Crash Reporting System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Tenth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy; ACM: New York, NY, USA, March 16, 2020; pp. 295–306. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-J.; You, M.; Shin, S. CR-ATTACKER: Exploiting Crash-Reporting Systems Using Timing Gap and Unrestricted File-Based Workflow. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 54439–54449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struminskaya, B.; Toepoel, V.; Lugtig, P.; Haan, M.; Luiten, A.; Schouten, B. Understanding Willingness to Share Smartphone-Sensor Data. Public Opin Q 2021, 84, 725–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.; Garcia-Font, V.; Rifà-Pous, H.; Megías, D. Collaborative and Efficient Privacy-Preserving Critical Incident Management System. Expert Syst Appl 2021, 163, 113727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Gao, F.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z. Achieving Anonymous and Covert Reporting on Public Blockchain Networks. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Yang, Y.; Feng, H.; Yuan, F.; Xie, H.; Zhang, J. PriRPT: Practical Blockchain-Based Privacy-Preserving Reporting System with Rewards. Journal of Systems Architecture 2023, 143, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Koo, D.; Kim, I.K.; Lee, E.; Yoo, S.; Lee, H.-Y. Opportunities and Challenges of a Dynamic Consent-Based Application: Personalized Options for Personal Health Data Sharing and Utilization. BMC Med Ethics 2024, 25, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtenhofer, C.; Fan, H.; Malik, J.; He, K. SlowFast Networks for Video Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision.

- Lee, J.; Shi, W.; Gil, J. Accelerated Bulk Memory Operations on Heterogeneous Multi-Core Systems. J Supercomput 2018, 74, 6898–6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Choi, N. A First Look at Wi-Fi 6 in Action: Throughput, Latency, Energy Efficiency, and Security. Proceedings of the ACM on Measurement and Analysis of Computing Systems 2023, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agiwal, M.; Abhishek, R.; Saxena, N. Next Generation 5G Wireless Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2016, 18, 1617–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer, R.; Stoep, J. Vander; Brubaker, C.; Kralevich, N. The Android Platform Security Model. ACM Transactions on Privacy and Security 2021, 24, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesner, F.; Kohno, T.; Moshchuk, A.; Parno, B.; Wang, H.J.; Cowan, C. User-Driven Access Control: Rethinking Permission Granting in Modern Operating Systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy; IEEE, May 2012; pp. 224–238. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Yang, W.; Xia, S.-T.; Zhou, E. Estimation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision.

- Gong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Du, X.; Su, L.; Weng, Z. Multicow Pose Estimation Based on Keypoint Extraction. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0269259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camgoz, N.; Koller, O.; Hadfield, S.; Bowden, R. Sign Language Transformers: Joint End-to-End Sign Language Recognition and Translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition.

- Zhao, X.; Wu, X.; Miao, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, P.C.Y.; Li, Z. ALIKE: Accurate and Lightweight Keypoint Detection and Descriptor Extraction. IEEE Trans Multimedia 2023, 25, 3101–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, L.; Materwala, H. ; P. Karduck, A.; Adem, A. Requirements of Health Data Management Systems for Biomedical Care and Research: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, L.; Materwala, H. A Review of Blockchain Architecture and Consensus Protocols: Use Cases, Challenges, and Solutions. MDPI Symmetry 2019, 11, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennebelle, A.; Ismail, L.; Materwala, H.; Al Kaabi, J.; Ranjan, P.; Janardhanan, R. Secure and Privacy-Preserving Automated Machine Learning Operations into End-to-End Integrated IoT-Edge-Artificial Intelligence-Blockchain Monitoring System for Diabetes Mellitus Prediction. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2024, 23, 212–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.-J. BLEU: A Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics - ACL ’02; Association for Computational Linguistics: Morristown, NJ, USA, 2001; p. 311. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-Y. Rouge: A Package for Automatic Evaluation of Summaries. In Proceedings of the Text summarization branches out; 2004; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Google AI MediaPipe Solutions Guide Available online:. Available online: https://ai.google.dev/edge/mediapipe/solutions/guide (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Li, S.; Jin, X.; Xuan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.-X.; Yan, X. Enhancing the Locality and Breaking the Memory Bottleneck of Transformer on Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, R.; Tham, C.-K. A Position Aware Transformer Architecture for Traffic State Forecasting. In Proceedings of the IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference; IEEE: Singapore, July 26 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, N.; Ismail, L. GLoT: A Novel Gated-Logarithmic Transformer for Efficient Sign Language Translation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Future Networks World Forum (FNWF); IEEE, October 15 2024; pp. 885–890. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A.; Fernández, S.; Gomez, F.; Schmidhuber, J. Connectionist Temporal Classification: Labelling Unsegmented Sequence Data with Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning - ICML ’06; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2006; pp. 369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Heafield, K. Queries. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the sixth workshop on statistical machine translation.

- Kudo, T.; Richardson, J. SentencePiece: A Simple and Language Independent Subword Tokenizer and Detokenizer for Neural Text Processing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 1715–1725. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Li, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y.; Al-Sarawi, S.F.; Abbott, D. MUD-PQFed: Towards Malicious User Detection on Model Corruption in Privacy-Preserving Quantized Federated Learning. Comput Secur 2023, 133, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Saddique, M.; Asghar, K.; Bajwa, U.I.; Hussain, M.; Habib, Z. Digital Video Tampering Detection and Localization: Review, Representations, Challenges and Algorithm. Mathematics 2022, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, B. Using Blockchain for Improved Video Integrity Verification. IEEE Trans Multimedia 2020, 22, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, K.; Nagarajan, S. Enhancing Cloud Security: A Multi-Factor Authentication and Adaptive Cryptography Approach Using Machine Learning Techniques. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society 2025, 6, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Work | Sign Language(s) |

Translation Formulation |

Model | Deployment Environment |

Consent | Runtime Measurement |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Unit | Input Modality |

Preprocessing | Algorithm | Edge | Cloud | Blockchain | System | Application | Training time | Preprocessing time | Inference time | Communication time | ||

| [8] | ASL | S2G, S2T | Words + Sentences | Keypoints | Smoothing and normalization |

Hierarchical Bidirectional RNN |

✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [9] | ASL | S2G2T | Words + Sentences | RGB | Segmentation and contour extraction |

Attention-based LSTM | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [10] | SSL | S2G | Words | RGB | Segmentation, contour extraction, ROI formation, and normalization |

CNN + Tree data structure | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [11] | DGS, CSL | S2G, S2G2T |

Sentences | RGB | Greyscale, resizing, and ROI formation | GCN + Transformer decoder |

✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [12] | DGS, CSL | S2G, S2G2T |

Sentences | RGB | Cropping | Transformer | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [13] | ASL, BSL, JSL, KSL | S2G | Words | RGB | Resizing and segmentation |

Attention-based CNN | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [14] | ASL, ArSL, KSL | S2G | Characters | RGB | Resizing | MLP | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [15] | ASL, TSL | S2G | Characters + Words | RGB | Frame extraction, grayscale conversion, normalization, background subtraction, and segmentation |

Attention-based CNN + LSTM | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [16] | LSA | S2G | Words | RGB | Segmentation, rescaling | LSTM | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [17] | DGS, CSL | S2G | Sentences | Keypoints | Partwise partitioning, and graph construction |

Graph Fourier Learning |

✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [18] | ASL | S2G | Words | Keypoints | ROI formation, hand cropping, rescaling, and padding |

YOLO | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| This Work | DGS, ASL | S2G2T | Sentences | Keypoints | Normalization, rescaling, and padding | Transformer-Based | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ASL: American Sign Language; ArSL: Arabic Sign Language; BSL: Bangla Sign Language; CSL: Chinese Sign Language; DGS: German Sign Language; JSL: Japanese Sign Language; KSL: Korean Sign Language; LSA: Argentine Sign Language; SSL: Sinhala Sign Language; TSL: Turkish Sign Language CNN: Convolution Neural Network; GCN: Graph Convolution Network; LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory; RNN: Recurrent Neural Network; ROI: Region of Interest; ✓: included;✗: not included. | |||||||||||||||

| Work | Application Domain |

Use Case | Consent | Data Collected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Purpose | ||||

| [32] | Web browsing | Web browser crash reporting |

System | Improve software reliability | Crash/bug-related traces, metadata, and user information |

| [33] | Operating system | Operating system crash reporting |

System | Bug diagnosis and security analysis |

Memory snapshots, CPU registers, user credentials, browsing history, cryptographic keys |

| [34] | Digital behavior | Willingness to share data for research | Application | Participate in research | GPS location, photos/videos (house and self), wearable sensor data |

| [35] | Critical incident management | Anonymous emergency reporting to authorities |

Application | Share data with authorities | Geo-coordinates, status alerts, media (optional) |

| [36] | Blockchain-based reporting | Anonymous crime reporting to authorities |

Application | Report criminal incidents | User data, embedded report data |

| [37] | Blockchain-based reporting | Anonymous crime reporting to authorities |

Application | Report criminal incidents | Reported information and cryptographic keys |

| [38] | Digital health | Sharing personal health data with healthcare and research entities |

Application | Control data access and sharing | Personal health, genomic, medications, mental health data |

| This Work |

Assistive technology |

Sign language translation |

System and Application |

Improve software reliability, bug diagnosis, enable private communication |

Videos, system performance logs (optional) |

| Consent Type | Purpose | Required Access | Data Transmitted | Data Storage |

Revocation Effect | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application | Translation | Camera | Keypoints and metadata | None | Camera access denied, translation stops |

Mandatory |

| Application | Improvement and retraining |

Keypoints and raw sign videos | Raw videos, keypoints, and metadata | On cloud | Immediate, no future data sharing, per policy | Optional |

| System | Reliability improvement |

Raw sign videos | Incident logs, raw videos, and metadata | On cloud | Immediate, no future data sharing, per policy | Optional |

| Participant | Event | Transaction | Asset | Scope | System Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User (Deaf) | Authorize consent | Grant consent | Consent receipt | 1. Translation 2. Model improvement 3. System diagnostics |

By scope: 1. Enable translation 2. Allow data storage and access 3. Allow diagnostic uploads and access on the client |

| Change consent scope(s) | Update consent | Consent receipt | Any of the above | Adjust allowed data processing, storage, and access on the client |

|

| Withdraw consent | Revoke consent | Consent receipt | Any of the above | Stop processing under the revoked scope on the client | |

| Sign Expert | Request viewing of consented sign videos | Request data access |

Data-use receipt: access outcome (granted/ denied) |

Curation | Gate and log access on cloud |

| Begin sign video annotation |

Annotate data (if granted) |

Access outcome | Curation | Annotation proceeds on cloud only if access is granted | |

| System Administrator |

System/ model passes security/ privacy/ evaluation checks |

Deploy system/ model | System certificate | Release system/ model | Roll out new system/ model on edge and cloud |

| Policy/ system updated, retrained model improved |

Update system/ model version | System certificate | Release new system/ model version | Roll out updated system/ model on edge and cloud | |

| Policy annulled, vulnerability detected, model performance degraded |

Revoke system/ model version | System certificate | Withdraw system/ model version | Roll back to previous system/ model version on edge and cloud | |

| Approved change in policy | Commit policy | Policy log | Policy | Enforce updated policy on edge and cloud | |

| Auditor | Periodic review | Read audit trails | Audit logs | Governance and legal compliance | Verify compliance and integrity on the ledger |

| Notes: - Consent entries include scope and validity window; revocation takes effect immediately, without affecting any previous data collection. - All transactions are logged on the ledger for auditing. | |||||

| Dataset | Sign Language |

Domain | # Videos | Vocabulary Size | Sentence length | # Signers | Resolution @fps |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gloss | Text | Gloss | Text | ||||||

| PHOENIX14T [24] | German | Weather | 8,257 | 1,115 | 3,004 | 32 | 54 | 9 | 210 × 260 @25 fps |

| MedASL | American | Medical | 2,000 | 1,142 | 1,682 | 10 | 16 | 1 | 1280 × 800 @30 fps |

| Metric | Notation | Definition | Equation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training time | Time required for model convergence during training. | |||

| Preprocessing time | Time required to convert sign videos into keypoints and prepare them for inference. | Not applicable | ||

| Inference time | Time required for model inference once preprocessing is completed. | Not applicable | ||

| Translation time | Total user-perceived translation time. | |||

| Edge-cloud communication time1 |

Uplink latency for transmitting keypoints and videos from the edge to the cloud. | Not applicable | ||

| Cloud-edge communication time2 |

Downlink latency for transmitting trained models from the cloud to the edge. | Not applicable | ||

| Overall end-to-end system time | Total system latency. | |||

|

1 Occurs under application-level consent for model improvement and/or system-level consent. 2 Occurs periodically after model retraining. |

||||

| Category | Hyperparameter | Configurations Studied | Selected Configurations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization | Loss functions | Gloss: CTC loss, none Text: Cross-Entropy loss |

Gloss: CTC loss Text: Cross-Entropy loss |

| Label smoothing | 0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Optimizer | Adam with β1=0.9 (default) or 0.99 and β2=0.999 (default) or 0.98 | Adam with β1=0.9, β2=0.98 | |

| Learning rate | 5×10-5, 1×10-5, 1×10-4, 1×10-3, 1×10-2 | 5×10-5 | |

| Weight decay | 0, 0.1, 0.001 | 0 | |

| Early stopping | Patience = 3, 5 Tolerance = 0, 1×10-2, 1×10−4, 1×10−6 |

Patience = 5 Tolerance = 1×10−6 |

|

| Learning rate scheduler | Constant with linear warmup until either 1,000 steps have been taken or 5% of the total training steps are reached, whichever is larger. | ||

| Training setup | Gradient clipping | None, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Epochs | 30, 100 | 30 | |

| Batch size | 32 | 32 | |

|

Model architecture |

Embedding dimension | 256, 512 | 512 |

| Encoder layers | 1, 2, 4, 12 | 1 | |

| Decoder layers | 1, 2, 4, 12 | 1 | |

| Attention heads | 8, 16 | 8 | |

| Feed-forward size | 512, 1024 | 512 | |

| Dropout | 0, 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Decoding | Gloss | Greedy or beam search | Greedy |

| Text | Greedy or beam search | Beam search with a size of 5 with reranking using a 4-gram KenLM * (interpolation weight 0.4, length penalty 0.2). | |

| CTC: Connectionist Temporal Classification [58]. *: We build a KenLM model [59] using text tokenized with SentencePiece [60] into BPE [61] sub-word units to rerank the generated translation. | |||

| Device | CPU | GPU | Storage | RAM | Connectivity | Operating System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intel RealSense Camera |

Vision Processor D4 (ASIC) | NA | 2 MB | NA | USB Type-C | NA |

| Edge | 1 x Intel Core i7-8700 at 4.20 GHz, 6 cores/CPU |

NA | 475 GB | 8 GB | Ethernet | Windows |

| Cloud | 2 x AMD EPYC 7763 at 2.45 GHz, 64 cores/CPU |

2 x NVIDIA RTX A6000 48GB/GPU | 5 TB | 1 TB | Wi-Fi, LTE*, Ethernet |

Ubuntu |

| NA: Not available; *: Supported through external hotspot. | ||||||

| Model | Dataset | BLEU-1 | BLEU-2 | BLEU-3 | BLEU-4 | ROUGE-1 | ROUGE-L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Decoder Transformer | PHOENIX14T | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| ADAT | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.27 | |

| Encoder-Decoder Transformer | MedASL | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| ADAT | 0.43 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Model | Preprocessing Time (ms) | Inference Time (ms) | Translation Time (ms) |

Cloud-to-Edge Communication Time (ms) |

Edge-to-Cloud Communication Time (ms) |

Overall End-to-End System Time (ms) |

Model Size (MB) | Keypoints Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Decoder Transformer | 0.03 | 188.25 | 188.28 | 11,725.42 | 324.09 | 512.37 | 134.8 | 3 |

| ADAT | 0.02 | 183.75 | 183.77 | 11,517.81 | 312.85 | 496.62 | 104.9 | 3 |

| ms: milliseconds. | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).