1. Introduction

Bonds between carbon atoms lie at the heart of organic chemistry, underlying a variety of phenomena from the reactivity of small molecules to the architecture of advanced polymers. A basic tenet of chemical bonding holds that shorter bonds are typically stronger, reflecting greater orbital overlap and electron sharing, while long bonds indicate instability [

1,

2,

3]. This correlation between bond length and bond strength underpins much of our chemical intuition and is used constantly in the design of stable molecular frameworks [

4,

5]. However, a growing number of structurally characterised compounds appear to defy this expectation, displaying carbon–carbon single bonds that stretch well beyond conventional distances while remaining remarkably stable under ambient conditions [

6,

7,

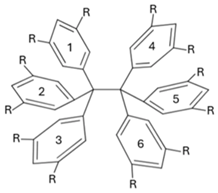

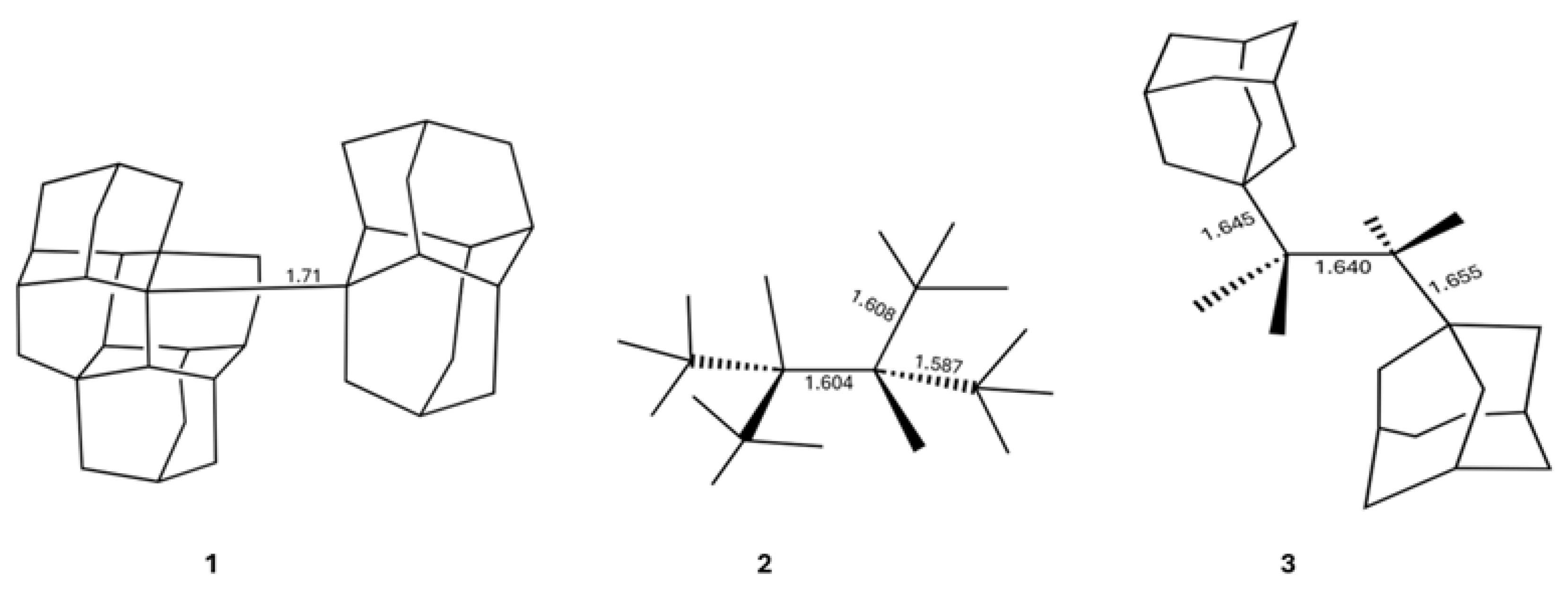

8]. Some of the most noticeable examples of this feature are diamondoid dimers, e.g., the molecule [121]tetramantane-diamantane

1 (

Figure 1) which is a very stable molecule with melting point of 246 °C, and yet it has the longest C–C bond for an alkane up to now (1.71 Å) [

9]. Another molecule having long, stable single C–C bonds is 1,1,2,2-tetra-

-buthyl ethane

2 (m.p. 150 °C) which presents three single C–C bonds wherein

d(C–C) > 1.58 Å [

10]. Likewise, 2,3-di-1-adamantyl-2,3-dimethyl butane

3 has three C–C bonds whose bond lengths are larger than 1.64 Å, and still, the corresponding crystal has a melting point of 167 °C [

11,

12]. These anomalously long yet stable bonds challenge textbook models of covalent bonding and raise fundamental questions about what forces can sustain such elongated chemical bonds [

12].

Among the forces capable of stabilising weak interactions between atoms, London Dispersion (LD), a long-range, non directional interaction, plays a uniquely universal role. Arising from correlated fluctuations in the electron positions, LD acts as an attractive force acting on all matter, growing stronger with increasing molecular size and polarisability [

13,

14]. In systems with large, flexible substituents,this effect becomes particularly significant. What might appear at first glance as simple steric crowding can instead give rise to a network of favorable dispersion contacts that compensate for the energetic cost of bond elongation. Rather than destabilising a stretched C–C bond, bulky groups may in some cases aid in its stabilisation by collectively lowering the total energy of the system via LD [

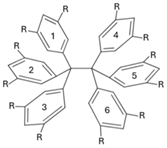

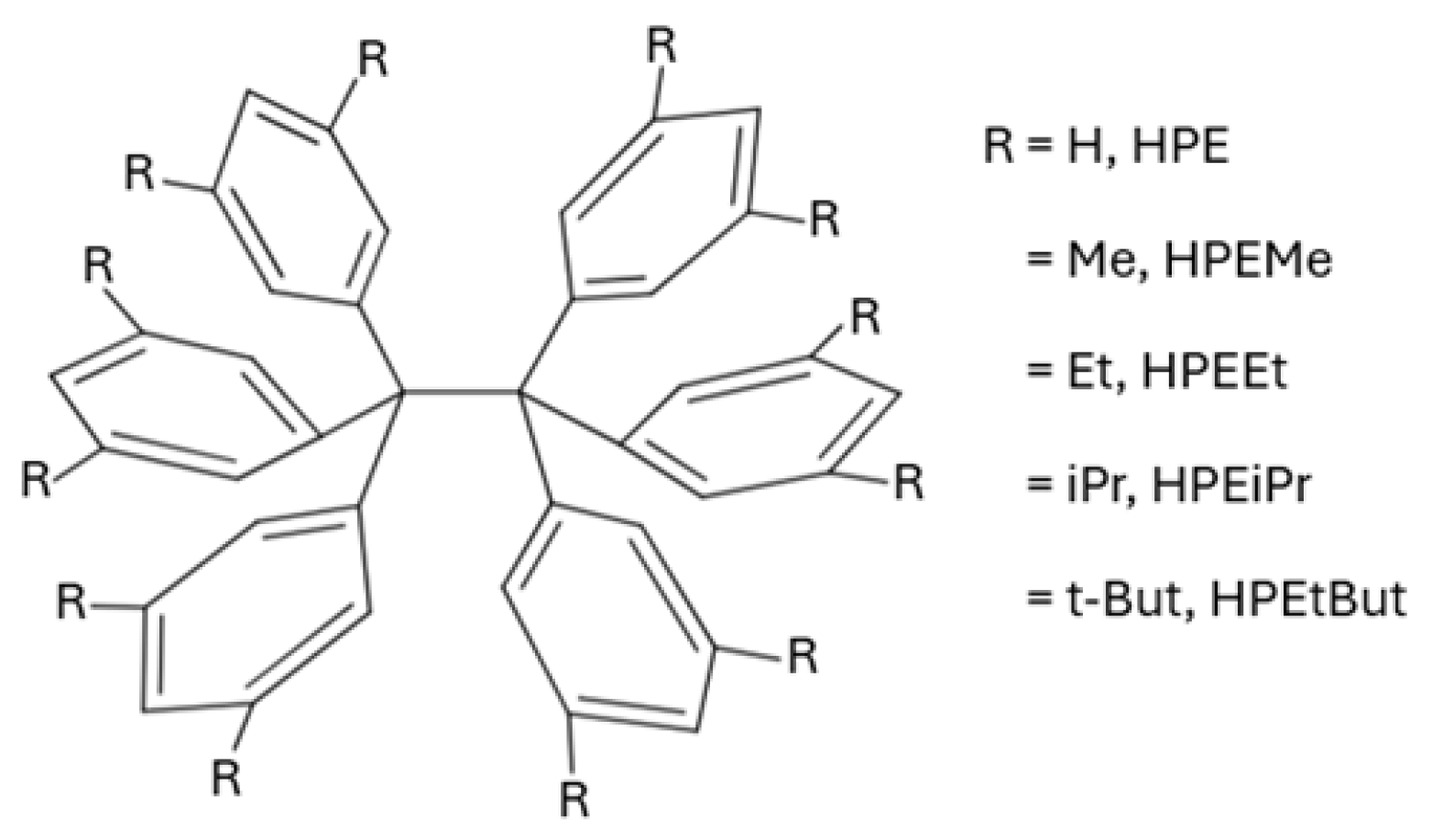

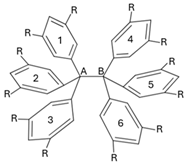

15]. A particularly conspicuous example is the effect of alkyl substituents on the hypothetical hexaphenylethane (HPE), (Ph)

3C–C(Ph)

3. Indeed, the introduction of large

tert-butyl groups in all meta positions leads to the isolation of hexa(3,5-di-

tert-butylphenyl) ethane which can be even characterised via X-ray crystal diffraction [

16,

17].

Experimental support for this view emerged most notably from the work of Schreiner and co-workers, who reported a series of remarkably stable alkanes with very long C–C bond lengths as previously shown in

Figure 1. These species, stabilised by bulky alkyl groups, are thought to owe their persistent long C–C single bonds largely to LD forces rather than conventional covalent bonding. This interpretation is based on computational studies, typically using dispersion-corrected density functional theory (e.g., PBE0-D3BJ) or high-level

ab initio methods, such as CCSD(T), which suggest a central role for dispersion in the stabilisation of these molecules. However, a detailed understanding of the energetic balance that makes such bonding possible remains incomplete. In particular, disentangling the physical contributions that stabilise very long C–C bonds remains a central challenge. Many energy decomposition schemes, though informative, rely on perturbative approximations or artificial fragmentations [

18]. These choices can misattribute stabilisation among exchange, electrostatics and dispersion, introduce strong basis and fragmentation dependence, and produce trends that vary with the partitioning scheme. Together, these issues hinder quantitative comparison across a series and can lead to misleading design rules [

19,

20]. In contrast, real-space approaches within the field of Quantum Chemical Topology (QCT) like the Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) enable a fully non-perturbative, atom-centric view of bonding [

21]. Among these, the Interacting Quantum Atoms (IQA) method offers a rigorous decomposition of the total energy into chemically interpretable intra- and interatomic components [

22,

23]. IQA has been successfully applied to a wide range of problems, including the analysis of hydrogen bonding, [

24,

25] non-covalent interactions, [

26,

27,

28,

29] transition-metal complexes, [

30,

31] and cooperative and anticooperative effects in non covalent assemblies [

32,

33,

34,

35].

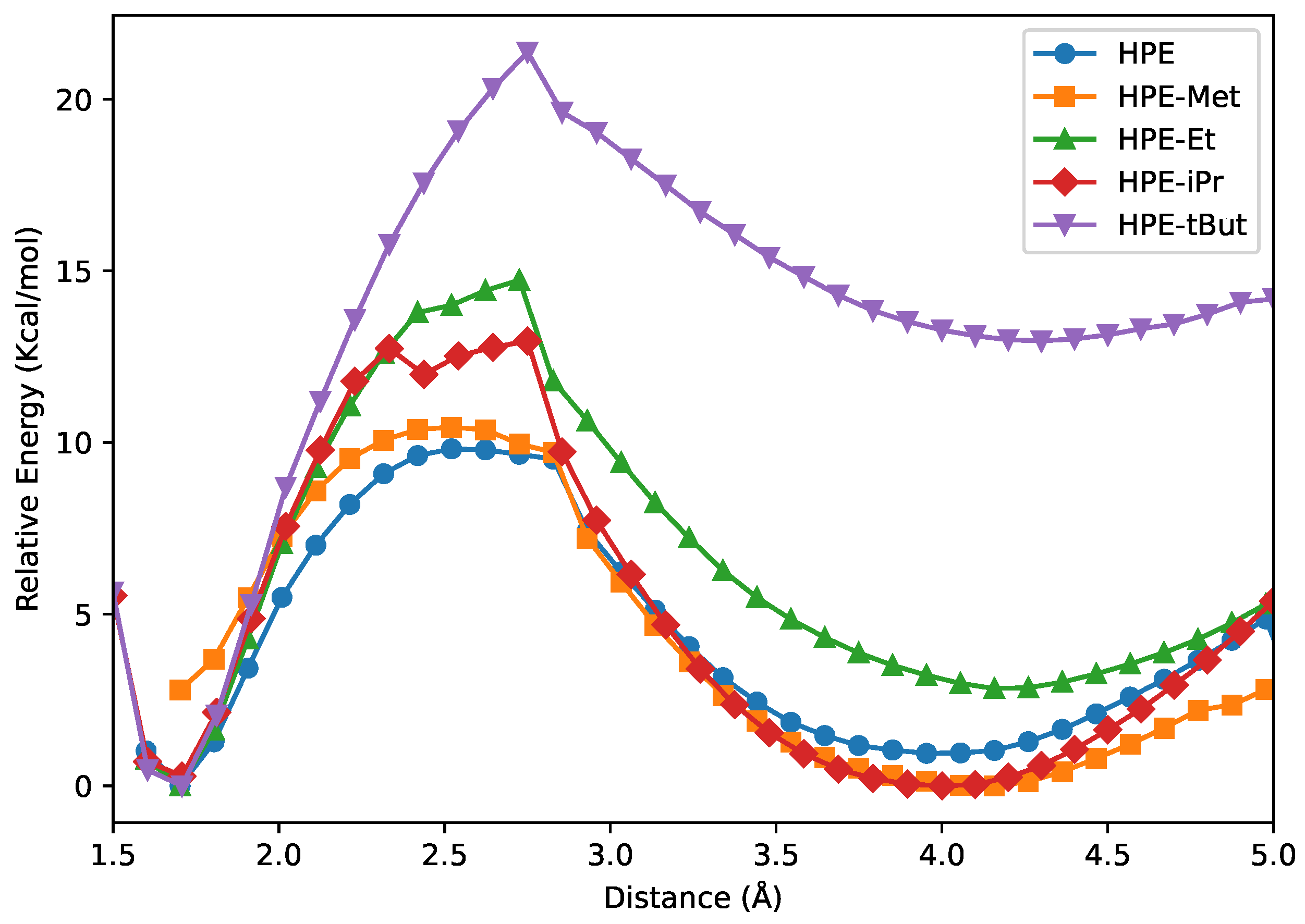

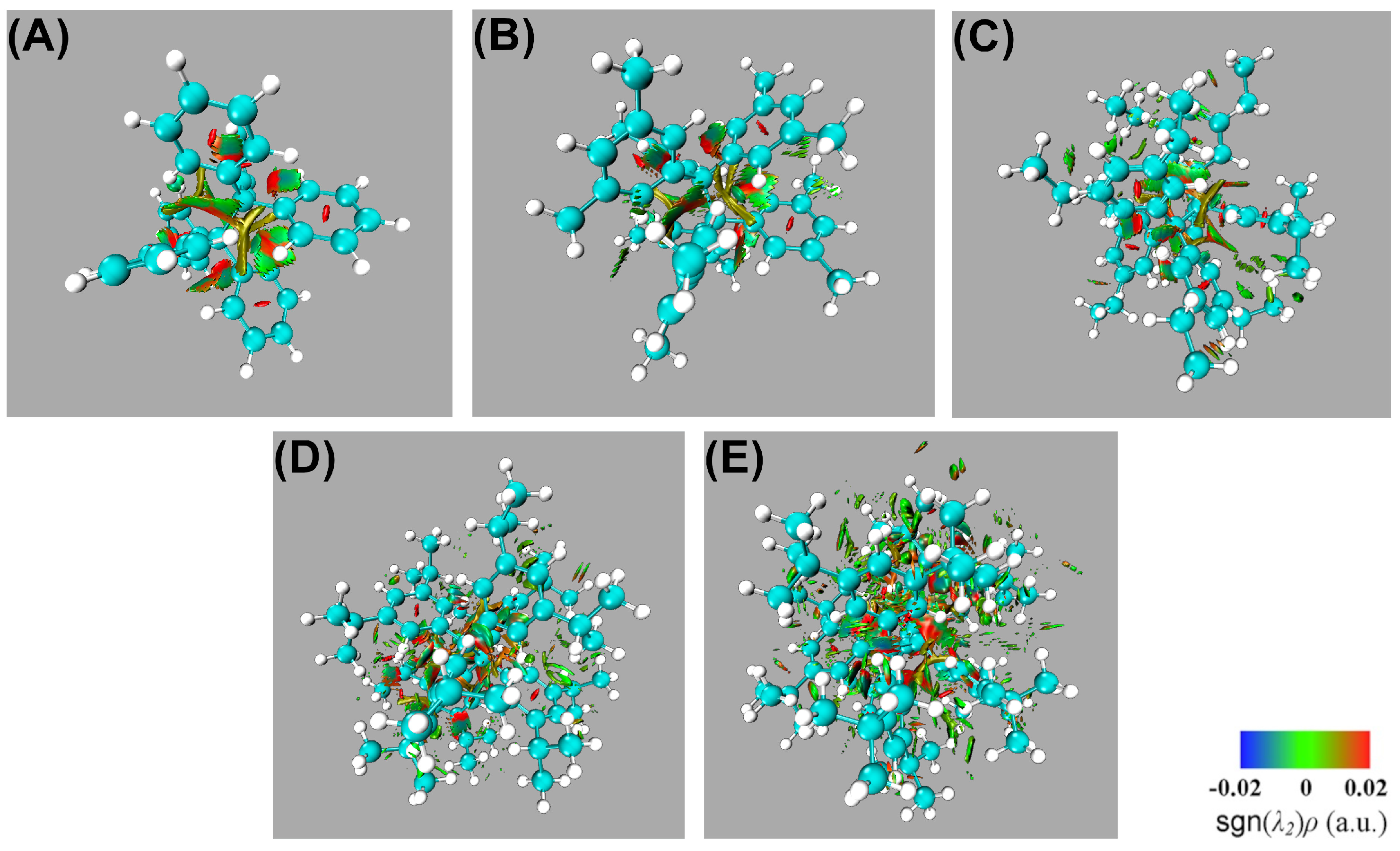

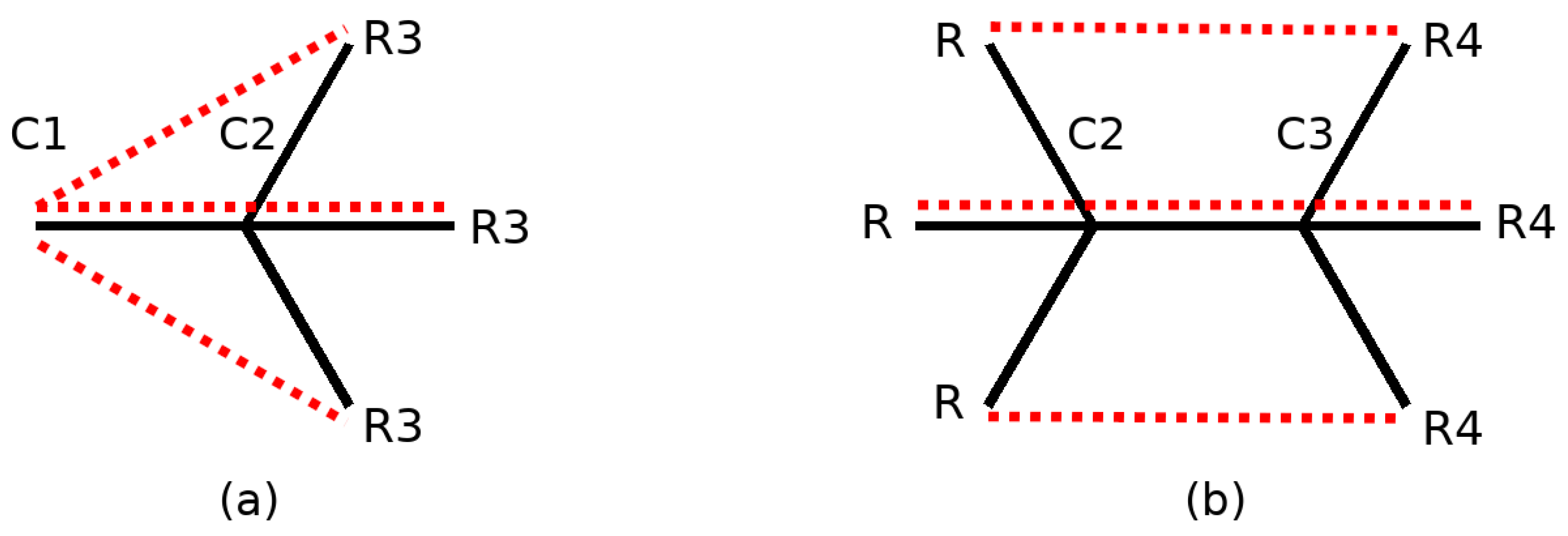

In this work, we apply QTAIM-based wave function analyses and the IQA partition of the electronic energy throughout a homologous series of compounds with long central C–C bonds to identify the most important energetic contributions in their stabilisation. More specifically, we focused on the series of compounds shown in

Figure 2, i.e., a set of HPE derivatives with progressively bulkier substituents, allowing us to track interaction energies and to examine the chemical bonding scenario evolution across this set of compounds. Altogether, our results reveal that the QCT characterisation of the strength of the central chemical C–C bond in the molecules shown in

Figure 2 does not align with the computed dissociation energy of these systems. This observation indicates that there other factors which contribute to stabilisation apart from the sole interaction between the carbon bonds in the ethane moiety. Indeed, the IQA analysis reveal the relevance of collective covalent 1–3 and more importantly 1–4 contacts in the compounds schematised in

Figure 2 apart from LD. More broadly, these results highlight the essential features and the relevance of collective interactions and they aid in the understanding of both non-covalent interactions and covalent bonding in highly congested environments.

2. Theoretical Framework

The field of QCT comprises a series of methods of wave function analysis based on the topological study of distinct scalar fields derived from the electronic vector state. The origin of QCT resides on the Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules which relies on the topographical examination of the electron density,

. Because the electron density is the expectation vaue of a Dirac observable, i.e.,

, the QTAIM analysis is orbital-invariant and independent on elements of the particular model of computation (e.g., basis sets). The QTAIM involves the determination of the critical points of

, i.e., points wherein

vanishes. Typically, molecular stable strucutures present critical points with range

, that is to say, whith three curvatures (the eigenvalues of the Hessian of

evaluated at the corresponding critical point) different from zero. Besides the rank, critical points of

are characterised according to their signature,

s, which equals to the algebraic sum of the signs of the curvatures at the critical point. In other words, critical points can be associated with the ordinate pair

. The critial points with

are related with different elements of molecular structure. Namely, the critical points with

, i.e.,

,

,

and

indicate the occurrence of nuclei, chemical bonds between two atoms, rings and cages, respectively. Hence, these critical points are respectively denoted as Nuclear Critical Points (NCP), Bond Critical Points (BCP), Ring Critical Points (RCP) and Cage Critical Points (CCPs). Indeed, the chemical bond between two atoms, can be characterised via the values of

as well as of other scalar fields at the corresponding BCP. These scalar fields include, for example,

,

and the density of energy

[

21,

36,

37]

By considering the dynamical system established by

, the QTAIM defines a division of the 3D space in atomic basins, A, B, …which are related with the atoms of chemistry [

37]. An atomic basin is defined as the stable manifold of an NCP. The atomic basins in QTAIM are separated by an interatomic surface, i.e., the stable manifold of a BCP. Because QTAIM atomic basins are proper open quantum subsystems, one can calculate atomic expectation values of quantum mechanical operators. For example, the average number of electrons within an atom A is,

and the corresponding QTAIM charge is

The QTAIM also defines the delocalisation index between two atoms A, and B,

, as

wherein

is the covariance of the two random variables

x and

y and

is defined in Equation (

1). The value of

is the number of electrons shared by the basins A and B and therefore it is a measure of the relevance of covalency in the interacton of these two QTAIM atoms.

After establishing a partition of the 3D space into atomic basins, as QTAIM provides, one can divide the electronic energy (

E) in intra- (

) and interatomic components (

),[

22,

23,

38]

The contributions to

and

can be computed completely in terms of the first order reduced density

and the pair density

. Although Kohn-Sham DFT does not define any of these scalar fields, it is possible to carry out to introduce very reasonable approximations that allow an IQA partition energy based on the Kohn-Sham DFT pseudo wave functions. The IQA interaction energy between atoms A and B,

, can be split into classical (

) and exchange-correlation components, (

)

which are respectively associated with the ionic and the covalent contributions of the interaction between atoms A and B. The consideration of the leading terms of the multipole expansion of

and

permits to approximate these two quantites as,

The IQA partition energy allows for the gathering of atoms in functional groups,

…whose net and interaction energies are given by,

respectively. A similar equation to expression (

5) holds for

and

, so that,

Finally, the energy associated to the formation of a

adduct,

,

is given by

wherein

(

) is the deformation energy of

within the adduct

, i.e., the difference in energy of

in (i) the adduct

and in (ii) its isolated, equilibrium configuration.

The noncovalent interaction (NCI) index provides a simple real–space scalar field to locate and visualise weak interactions by analysing regions of low electron density and low density gradient [

39]. It is based on the reduced density gradient

whose small values highlight spatial domains where noncovalent contacts occur. To distinguish the nature of these contacts, NCI maps are coloured using

, where

is the second eigenvalue of the Hessian of

: negative

(blue) indicates attractive interactions such as hydrogen bonding or dispersion–dominated contacts, values near zero (green) correspond to weak van der Waals regimes, and positive

(red) signals steric repulsion. Plotting isosurfaces of

at a low threshold, coloured by

, thus yields an intuitive picture of where weak interactions stabilise or destabilise a structure. NCI does not provide energies by itself, but it complements QTAIM and IQA by revealing the spatial extent and character of the interactions that those methods quantify.

Author Contributions

A.B.-E. performed the quantum-chemical calculations (optimizations and frequencies), generated the wavefunctions, carried out the QTAIM and IQA analyses, curated the datasets, and prepared figures. J.M.G.-V. developed the analysis workflows, implemented and tested IQA post-processing scripts, validated results across the series, contributed visualizations, and wrote the first draft. E.F. contributed to the theoretical and methodological aspects of the IQA framework, advised on analysis and interpretation, and reviewed and edited the text. T.R.-R. and Á.M.P. conceived and supervised the project, refined the study design and theoretical framing, contributed to methodology, oversaw validation, led critical revisions, co-wrote and revised the manuscript, and secured funding and project administration. All authors discussed the results, contributed to the final manuscript, and approved the version to be submitted.