Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

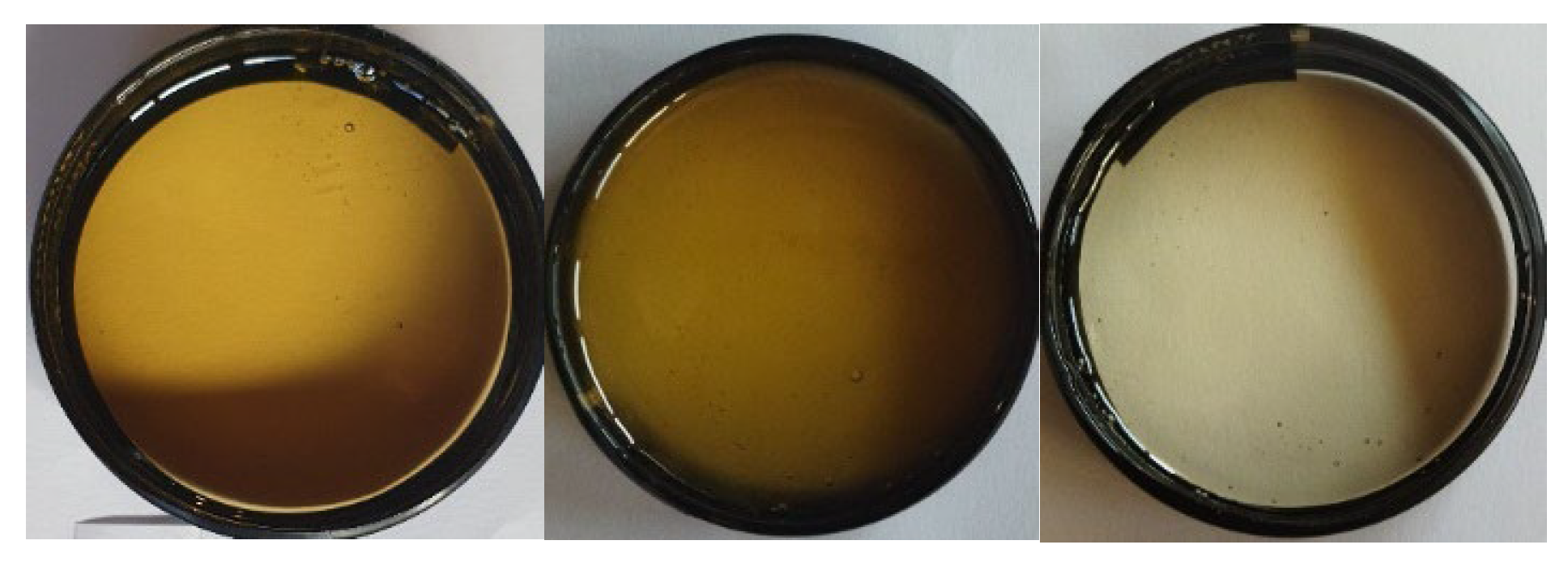

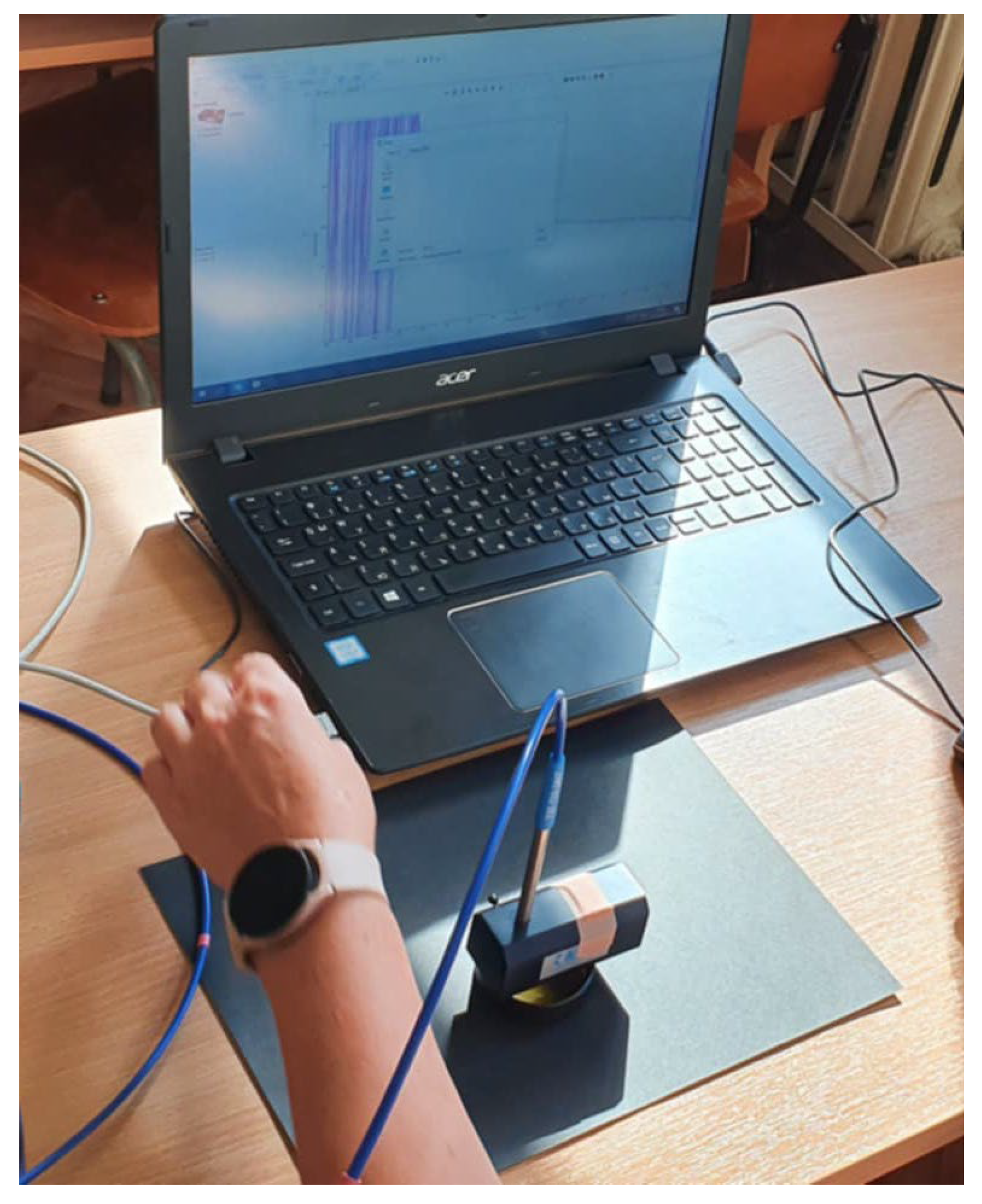

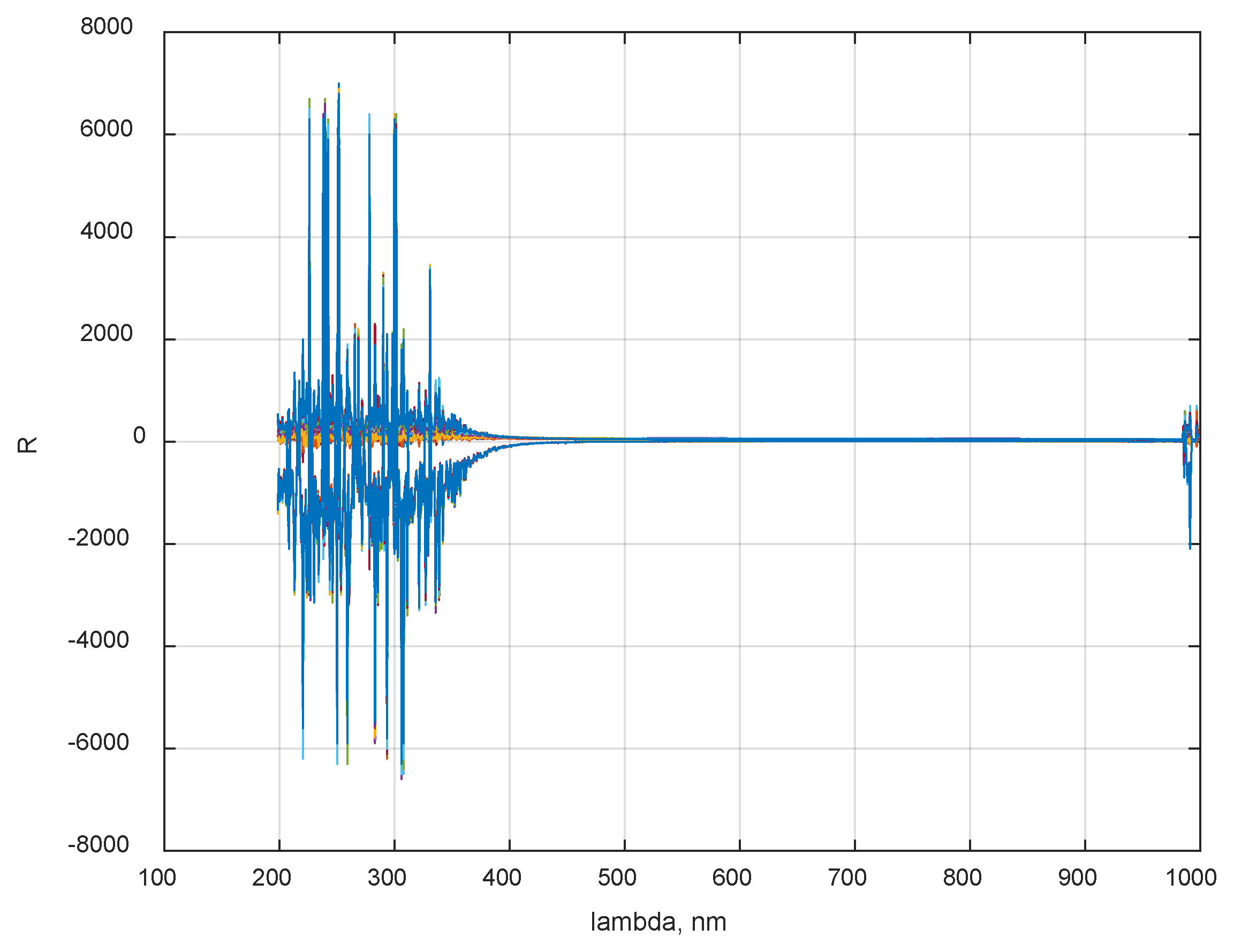

2.1. Honey Samples Collection and Spectral Data Acquisition

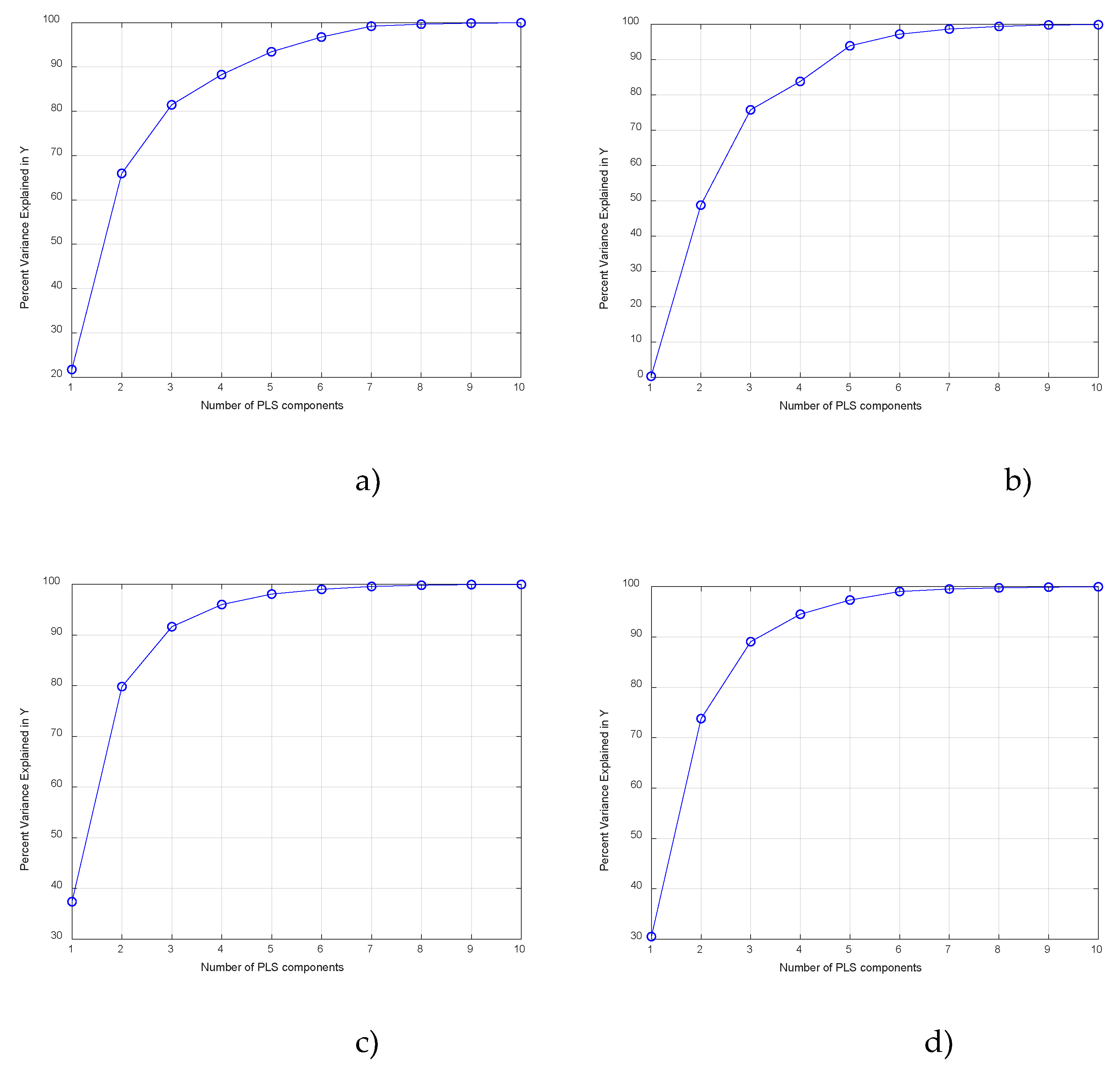

2.2. Chemometric Regression Methods Used for Quality Evaluation of Honey Samples

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results and Discussion

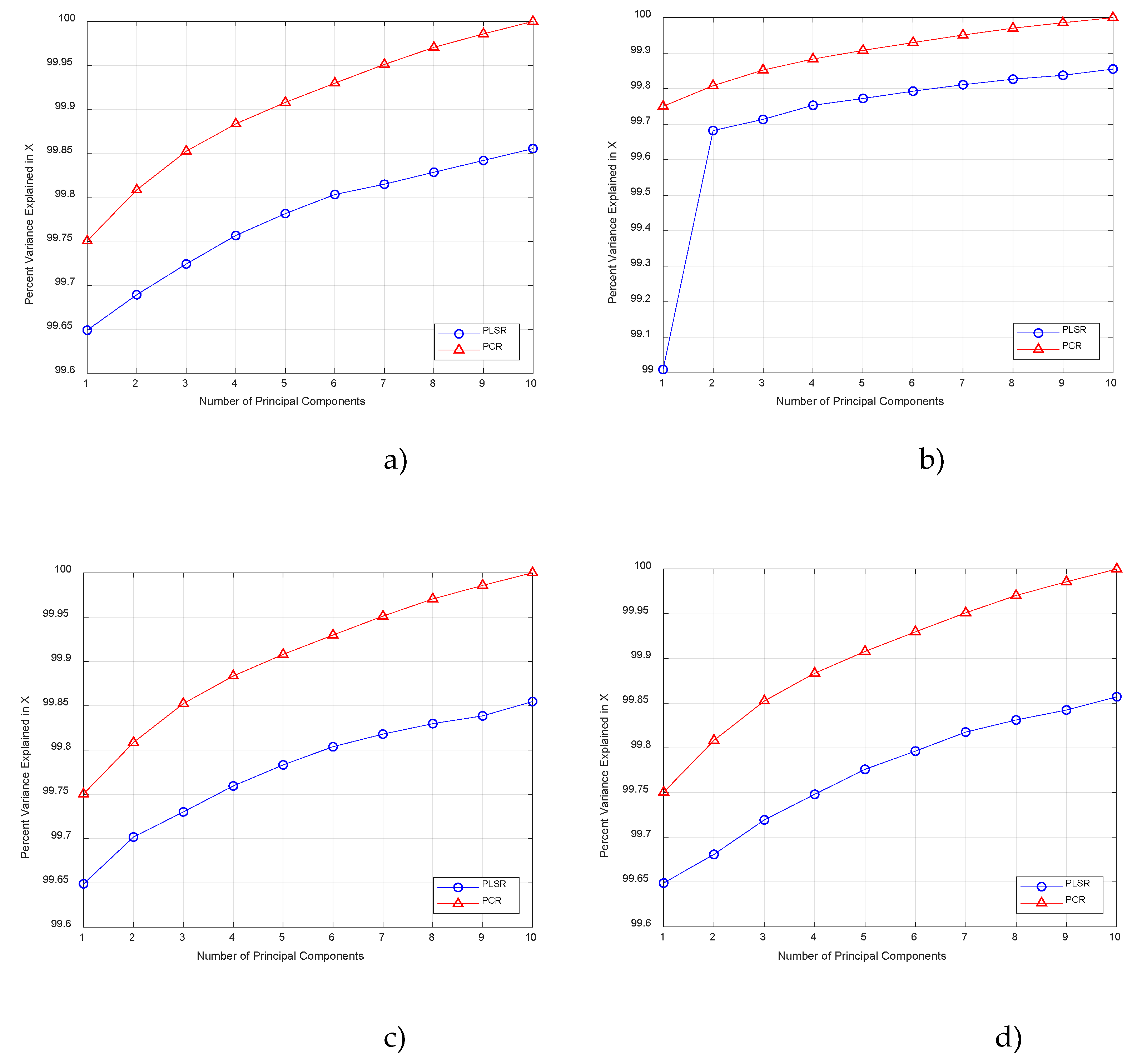

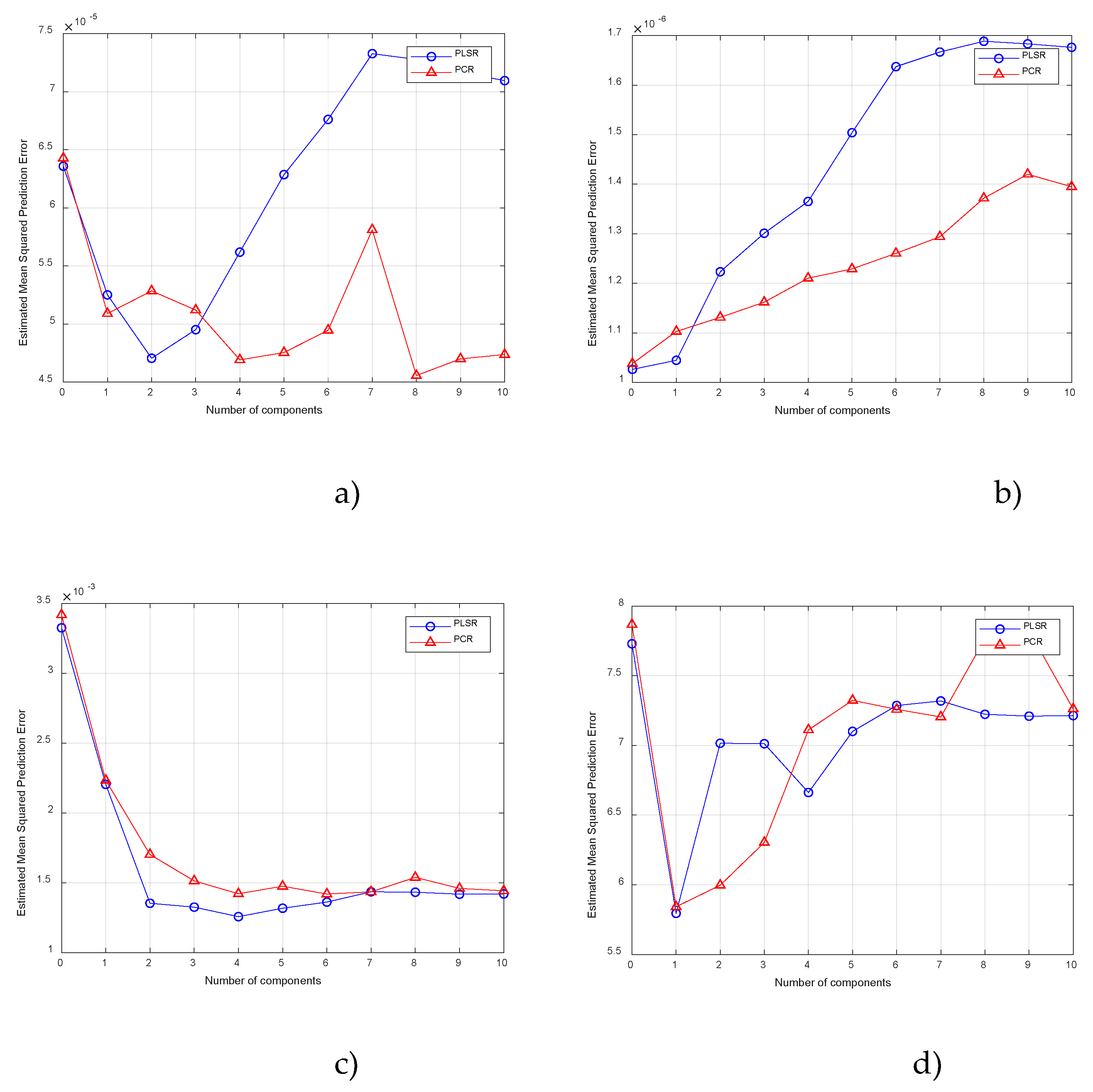

3.1. Determination the Content of the Heavy Metals

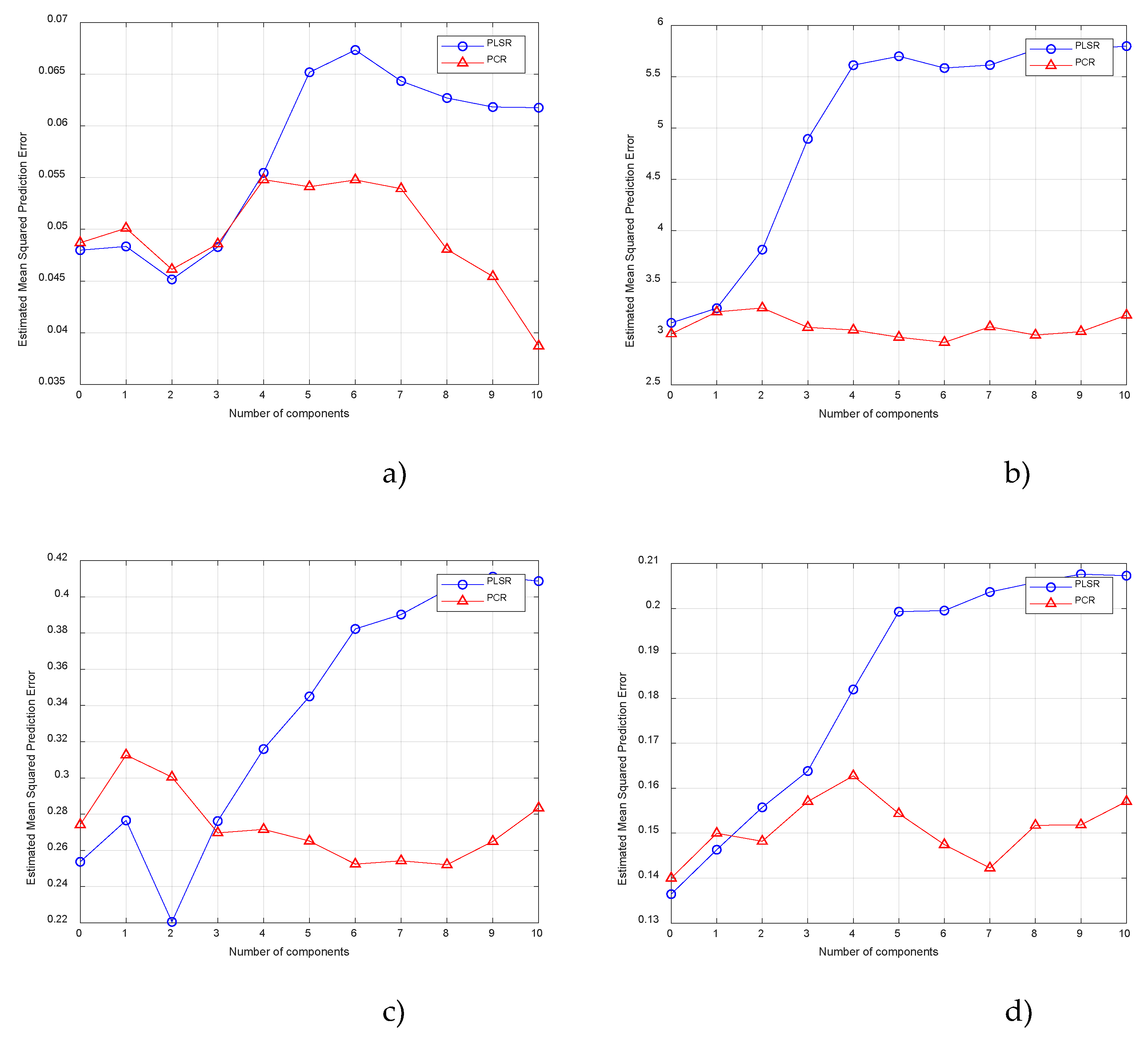

3.2. Determination the Content of the Physicochemical Indicators

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen; L.; Wang; J.; Ye; Z.; Zhao; J.; Xue; X.; Heyden; Y. Vander; Sun; Q.; 2012.Classification of Chinese honeys according to their floral origin by near infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 135; 338–342. [CrossRef]

- Devi; A.; Jangir; J.; K.A.; A.-A.; 2018. Chemical characterization complemented with chemometrics for the botanical origin identification of unifloral and multifloral honeys from India. Food Res. Int. 107; 216–226. [CrossRef]

- Rochman; S.; & Mukhtar; M. N. A. (2019). Classification of the quality of honey using the spectrofotometer and machine learning system based on single board computer. Tibuana; 2(01); 45–49. [CrossRef]

- Truong T. D. H.; Reddy P.; Reis M.M.; Archer R.; (2022). Quality assessment of mānuka honeys using non-invasive Near Infrared systems; Journal of Food Composition and Analysis; Volume 114; 104780; ISSN 0889-1575. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X.; Yang J.; Lin T.; Ying Y. (2021). Food and agro-product quality evaluation based on spectroscopy and deep learning: A review; Trends in Food Science & Technology; Vol. 112; 431-441; ISSN 0924-2244.

- . [CrossRef]

- Maionea, C.; F Barbosa, Jr.; Barbosa, R.M. Predicting the botanical and geographical origin of honey with multivariate data analysis and machine learning techniques: A review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 157 (2019) 436–446. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, S.; ruoff, K.; Persano Oddo, L. (2004). Physico-chemical methods for the characterisation of unifloral honeys: a review; Apidologie 35 S4–S17; INRA/DIB-AGIB/ EDP Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Md Abdullah Al Noman; Anannya Barua Nijhum; Iqbal Hossain; Md Sakibul Islam; Istiaq Mahmud Sifat; Mohammad Gulzarul Aziz; Afzal Rahman; NON- ESTRUCTIVE adulterants detection in Various honey types in Bangladesh using UV–VIS–NIR spectroscopy coupled with machine learning algorithms; LWT; Volume 228; 2025; 118125; ISSN 0023-6438. [CrossRef]

- Silva A.; Maciel M.C.; Ferreira de Oliveira A.A.; Ferreira de Oliveira T.; Evaluation of the content of macro and trace elements and the geographic origin of honey in North Brazil through statistical and machine learning techniques; Journal of Food Composition and Analysis; Volume 128; 2024; 106050; ISSN 0889-1575. [CrossRef]

- Koraqi H.; Wawrzyniak J.; Aydar A. Y.; Pandiselvam R.; KhalideW.; Petkoska A. T.; Karabagias I.K.; Ramniwas S.; Rustagi S.;Application of multivariate analysis and Kohonen Neural Network to discriminate bioactive components and chemical composition of kosovan honey; Food Control; Volume 172; 2025; 111072. [CrossRef]

- Kassa A.; Ayalew M.Chemometric analysis of physicochemical properties and heavy metal content in honey: A case study from Saint Adijibar; South Wollo; Amhara; Ethiopia. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 146 (2025) 107923. [CrossRef]

- HATEGAN A.R.; DEHELEAN A.; PUSCAS R.; CRISTEA G.; BELC N.; MUSTATEA G.; MAGDAS D.A.; The development of honey recognition models with broad applicability based on the association of isotope and elemental content with ANNs; Food Chemistry; Volume 458; 2024; 140209. [CrossRef]

- Nunes A.; Azevedo G.Z.; Rocha dos Santos B.; Melo de Liz M.S.; Schneider F.S.; Rodrigues E. R.; Moura S.; Maraschin M.; A guide for quality control of honey: Application of UV–vis scanning spectrophotometry and NIR spectroscopy for determination of chemical profiles of floral honey produced in southern Brazil; Food and Humanity; Volume 1; 2023; Pages 1423-1435. [CrossRef]

- Furong Huang; Han Song; Liu Guo; Peiwen Guang; Xinhao Yang; Liqun Li; Hongxia Zhao; Maoxun Yang; Detection of adulteration in Chinese honey using NIR and ATR-FTIR spectral data fusion; Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy; Volume 235;2020;118297; ISSN 1386-1425. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Xiao-Hua; Gu Hui-Wen; Liu Ren-Jun; Qing Xiang-Dong; Nie Jin-Fang.(2023). A comprehensive review of the current trends and recent advancements on the authenticity of honey. Food Chemistry: X 19 (2023) 100850. [CrossRef]

- Davor Valinger, Lucija Longin, Franjo Grbeš, Maja Benković, Tamara Jurina, Jasenka Gajdoš Kljusurić, Ana Jurinjak Tušek, Detection of honey adulteration – The potential of UV-VIS and NIR spectroscopy coupled with multivariate analysis, LWT, Volume 145, 2021, 111316, ISSN 0023-6438. [CrossRef]

- Andrews A. Boateng, Salma Sumaila, Michael Lartey, Mahmood B. Oppong, Kwabena F.M. Opuni, Lawrence A. Adutwum, Evaluation of chemometric classification and regression models for the detection of syrup adulteration in honey, LWT, Volume 163, 2022, 113498, ISSN 0023-6438. [CrossRef]

- Yang Li, Yue Huang, Jingjing Xia, Yanmei Xiong, Shungeng Min, Quantitative analysis of honey adulteration by spectrum analysis combined with several high-level data fusion strategies, Vibrational Spectroscopy, Volume 108, 2020, 103060, ISSN 0924-2031. [CrossRef]

| Name of Honey | № | Region of production | Year | As | Cd | Pb | Fe | pH | Reducing sugars | Saccharose | Water |

| [mg/kg] | [%] | ||||||||||

| Rapeseed | 1 | Brestovica | 2023 | 0.043 | 0.009 | 0.318 | 14.700 | 4.43±0.03 | 73.54±0.01 | 2.15±0.01 | 17.12±0.02 |

| Sunflower | 2 | Borovo - Stara Zagora | 2023 | 0.041 | 0.006 | 0.233 | 1.460 | 3.74±0.01 | 72.16±0.04 | 1.89±0.01 | 17.39±0.01 |

| Sunflower | 3 | Brestovica | 2023 | 0.041 | 0.006 | 0.264 | 8.690 | 3.79±0.01 | 72.36±0.03 | 1.83±0.03 | 17.38±0.02 |

| Linden | 4 | Yuper | 2023 | 0.034 | 0.006 | 0.255 | 6.571 | 4.23±0.03 | 73.68±0.02 | 2.11±0.01 | 17.33±0.02 |

| Multiflower | 5 | Borovo-Stara Zagora | 2023 | 0.033 | 0.005 | 0.282 | 7.570 | 3.83±0.01 | 74.19±0.03 | 2.09±0.03 | 17.85±0.03 |

| Sanflower | 6 | Modjereto | 2023 | 0.044 | 0.005 | 0.319 | 6.601 | 3.73±0.02 | 72.31±0.02 | 2.21±0.02 | 17.50±0.03 |

| Rapeseed & Amorpha | 7 | Stara Zagora- Pamukchii | 2024 | 0.049 | 0.006 | 0.304 | 7.190 | 3.66±0.03 | 71.15±0.04 | 1.31±0.02 | 17.13±0.02 |

| Acacia & Mana | 8 | Brestowica | 2023 | 0.044 | 0.006 | 0.339 | 4.191 | 3.92±0.02 | 73.15±0.01 | 1.31±0.01 | 17.09±0.03 |

| Draka & Pustren | 9 | Stara Zagora | 2023 | 0.062 | 0.006 | 0.331 | 4.591 | 3.86±0.03 | 75.43±0.03 | 1.73±0.01 | 17.02±0.02 |

| Acacia | 10 | Yuper | 2023 | 0.055 | 0.005 | 0.376 | 5.331 | 3.73±0.02 | 73.50±0.03 | 1.91±0.01 | 17.82±0.02 |

| Multiflower | 11 | Yuper | 2024 | 0.034 | 0.006 | 0.347 | 5.031 | 3.70±0.02 | 73.92±0.03 | 2.23±0.02 | 17.71±0.02 |

| Multiflower | 12 | Yuper | 2013 | 0.048 | 0.007 | 0.364 | 6.891 | 3.72±0.01 | 74.13±0.02 | 2.19±0.02 | 17.81±0.03 |

| Sunflower | 13 | Trakian University | 2023 | 0.041 | 0.006 | 0.395 | 6.010 | 3.82±0.03 | 72.32±0.03 | 1.79±0.01 | 17.40±0.02 |

| Lavender | 14 | Stara Zagora | 2022 | 0.042 | 0.006 | 0.398 | 7.003 | 3.48±0.03 | 74.47±0.04 | 3.25±0.026 | 17.52±0.03 |

| Lavender | 15 | Stara Zagora | 2023 | 0.041 | 0.006 | 0.397 | 5.551 | 3.54±0.01 | 74.35±0.02 | 3.30±0.01 | 17.64±0.02 |

| Mana | 16 | Stara Zagora | 2023 | 0.045 | 0.005 | 0.408 | 6.510 | 4.10±0.01 | 66.64±0.03 | 1.13±0.02 | 16.71±0.02 |

| Multiflower | 17 | Stara Zagora | 2023 | 0.048 | 0.008 | 0.385 | 3.550 | 3.75±0.01 | 74.43±0.03 | 2.07±0.05 | 17.64±0.01 |

| Multiflower - nr 9 | 18 | Razgrad | 2023 | 0.060 | 0.005 | 0.417 | 5.370 | 3.69±0.01 | 74.63±0.02 | 2.15±0.05 | 17.59±0.03 |

| Multoflower - nr 1 | 19 | Haskovo | 2023 | 0.043 | 0.005 | 0.448 | 1.541 | 3.67±0.02 | 74.52±0.03 | 2.11±0.01 | 17.45±0.01 |

| Multiflower -nr 10 | 20 | Ruse | 2023 | 0.051 | 0.005 | 0.368 | 3.880 | 3.79±0.02 | 74.79±0.02 | 2.23±0.04 | 17.50±0.01 |

| Multiflower - nr 8 | 21 | Razgrad | 2023 | 0.048 | 0.007 | 0.449 | 1.932 | 3.93±0.02 | 74.93±0.02 | 2.34±0.01 | 17.69±0.01 |

| Multiflower -nr 6 | 22 | Ruse | 2023 | 0.064 | 0.006 | 0.408 | 4.650 | 4.14±0.02 | 74.89±0.01 | 2.49±0.02 | 17.63±0.04 |

| Multiflower- nr 2 | 23 | Turgovishte | 2023 | 0.050 | 0.007 | 0.444 | 4.090 | 3.73±0.01 | 74.53±0.02 | 2.41±0.01 | 17.48±0.04 |

| Multiflower - nr 4 | 24 | Turgovishte | 2023 | 0.045 | 0.008 | 0.382 | 0.918 | 3.83±0.01 | 74.44±0.02 | 2.58±0.03 | 17.64±0.01 |

| Multiflower- nr 3 | 25 | Turgovishte | 2023 | 0.045 | 0.006 | 0.386 | 3.520 | 3.90±0.01 | 74.79±0.01 | 2.49±0.02 | 17.87±0.03 |

| Multiflower - nr 6 | 26 | Sliven | 2023 | 0.056 | 0.006 | 0.392 | 4.607 | 3.88±0.01 | 74.62±0.03 | 2.37±0.02 | 17.65±0.01 |

| Multiflower - nr 7 | 27 | Sliven | 2023 | 0.046 | 0.006 | 0.384 | 2.150 | 3.69±0.01 | 74.69±0.03 | 2.45±0.01 | 17.58±0.03 |

| Lindon | 28 | Novo Village | 2023 | 0.046 | 0.006 | 0.379 | 2.930 | 4.28±0.03 | 73.60±0.04 | 2.05±0.00 | 17.24±0.02 |

| Acacia & rapeseed | 29 | Ivanovo | 2024 | 0.056 | 0.005 | 0.408 | 2.330 | 3.68±0.02 | 72.23±0.03 | 1.24±0.02 | 16.14±0.03 |

| Chemometric method | values | |||

| Arsenic (As) | Cadmium (Cd) | Lead (Pb) | Iron (Fe) | |

| PLSR | 0.6598 | 0.4881 | 0.7981 | 0.7378 |

| PCR | 0.2577 | 0.0106 | 0.5883 | 0.3210 |

| Chemometric method | values | |||

| pH |

Reducing sugars |

Sweet disaccharide |

Water content |

|

| PLSR | 0.5526 | 0.4061 | 0.5693 | 0.4384 |

| PCR | 0.1523 | 0.0414 | 0.2450 | 0.0413 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).