Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Parameters of Sperm Functionality

2.2. Antioxidant Status of Turkey Semen

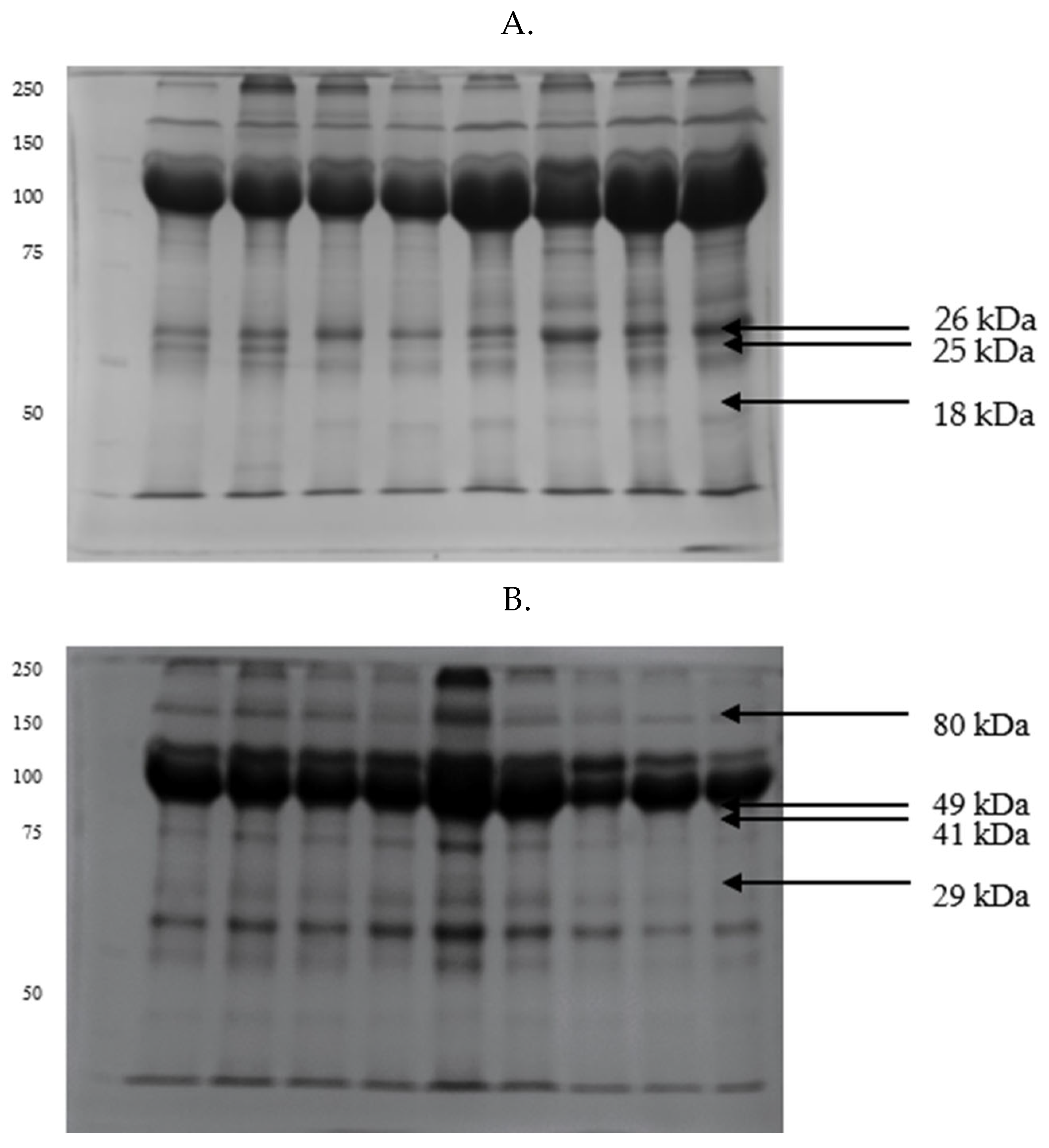

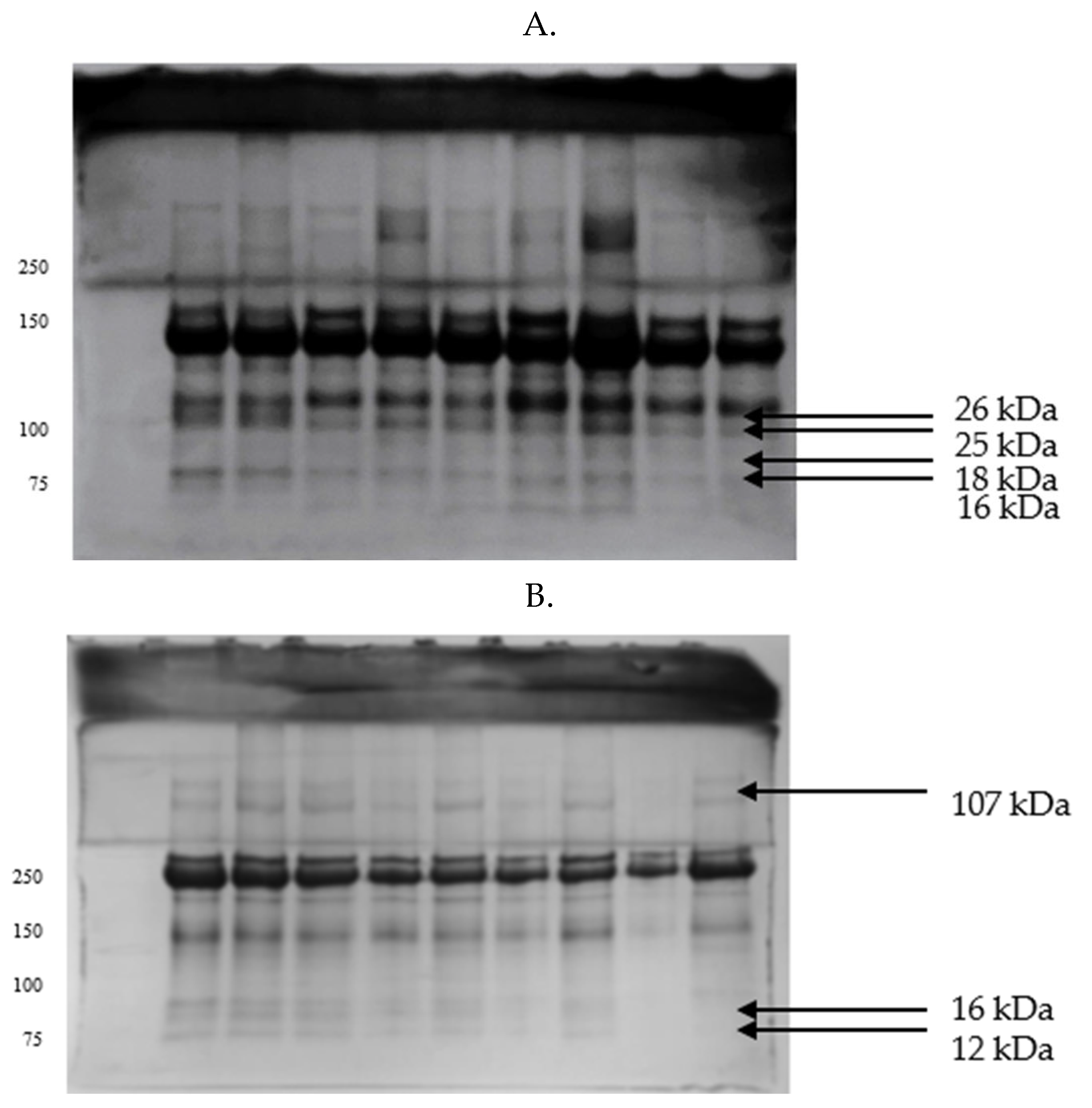

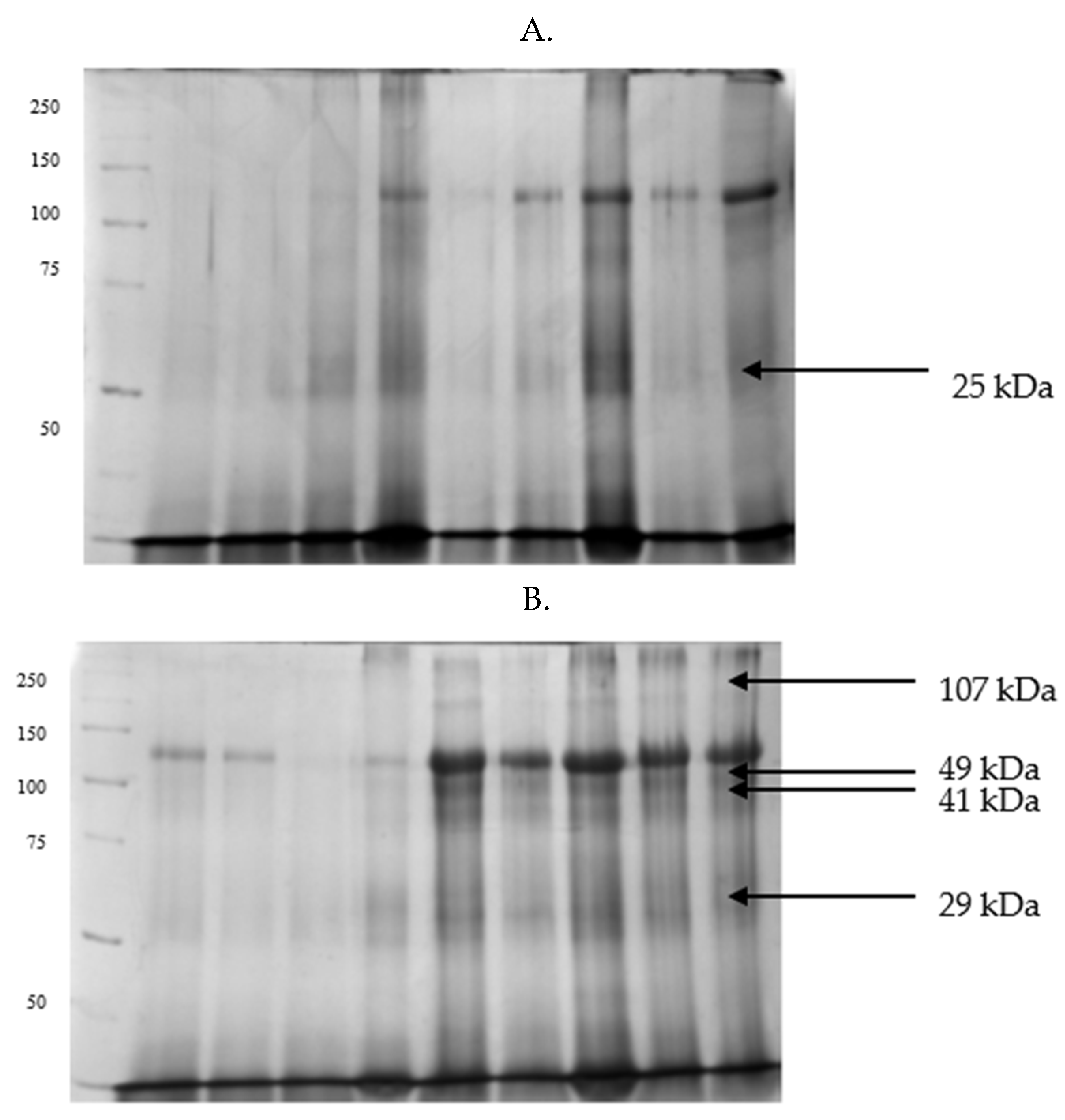

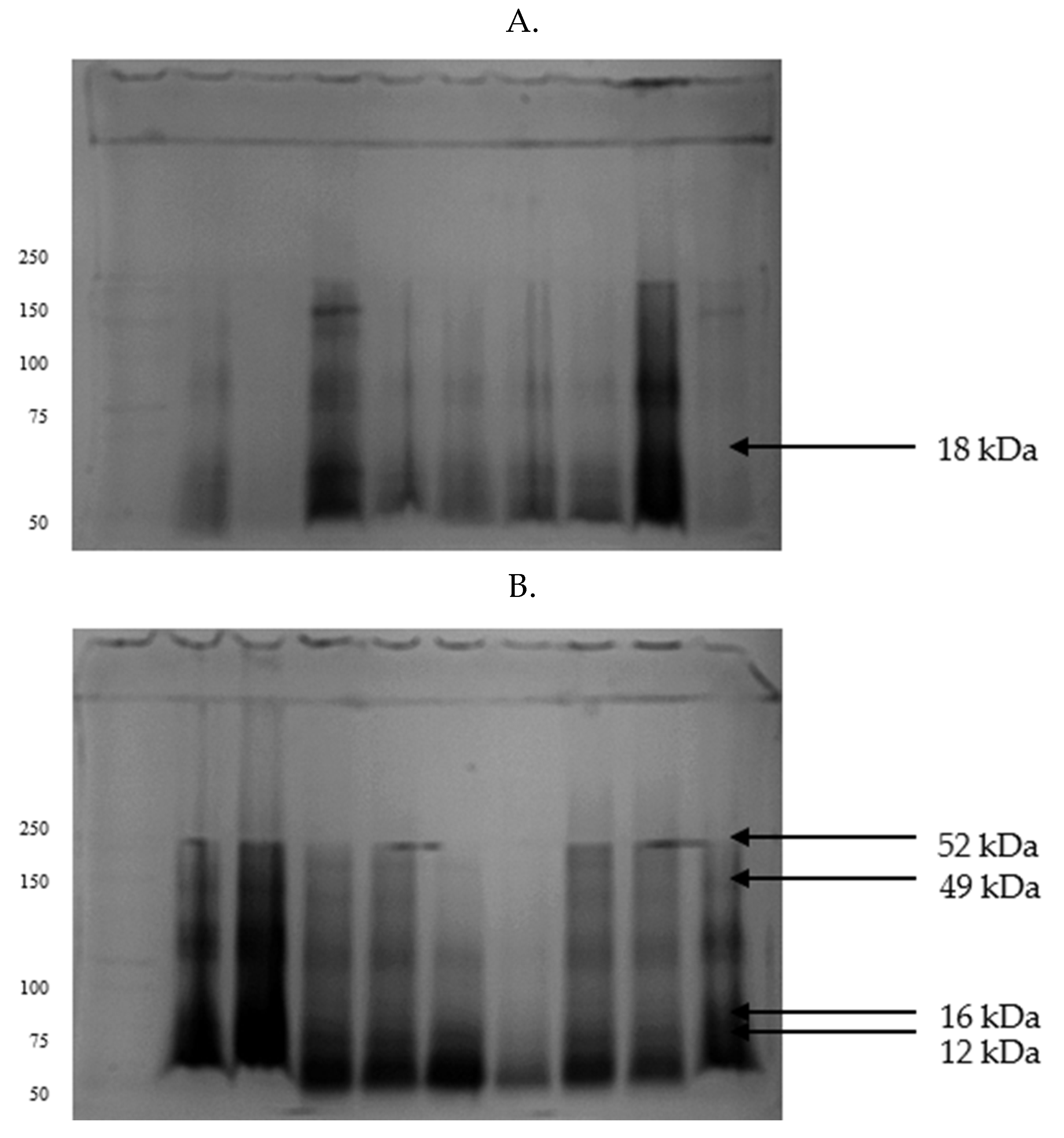

2.3. Differences in the Proteomic Profiles of Seminal Plasma and Spermatozoa from Ejaculates with Good and Impaired Fertility

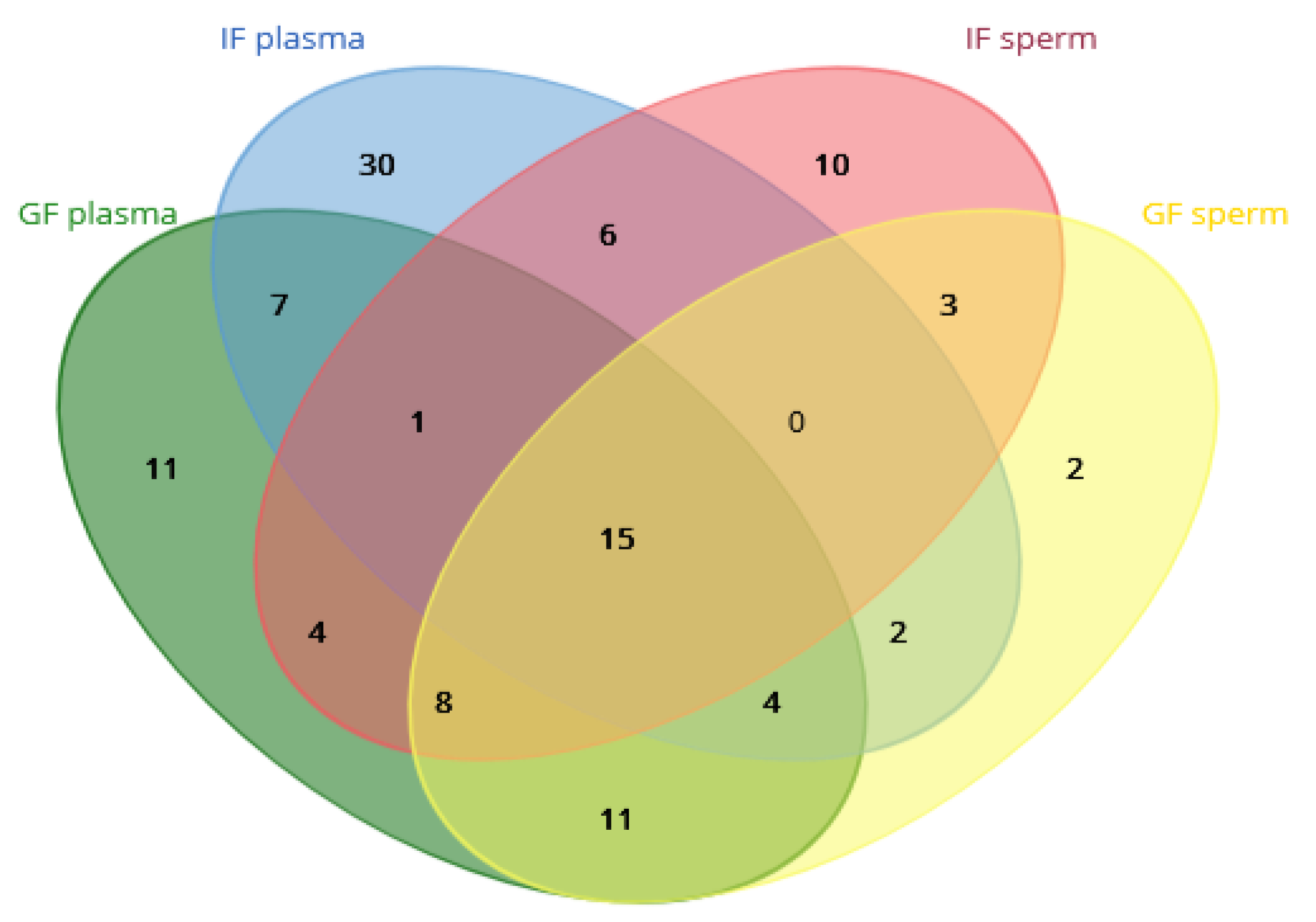

2.4. Protein Identification Results

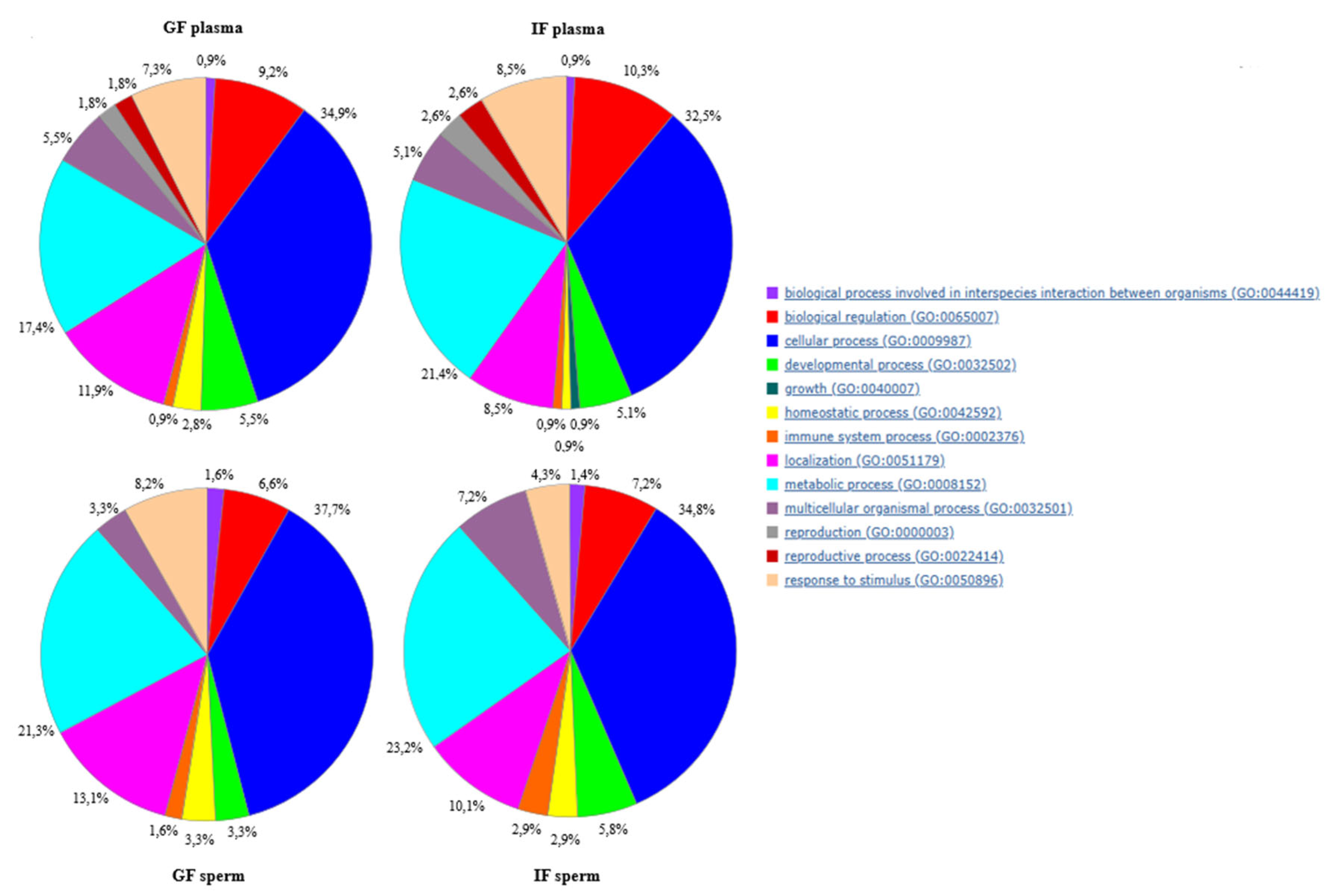

2.5. Gene Ontology Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Potential Impact of Oxidative Stress on Low-Quality Semen

3.2. Potential Impact of Proteome Composition on IF Semen

3.3. Potential Impact of Other Factors on the Parameters of IF Semen

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Material Collection

4.2. Assessment of Sperm Concentration

4.3. Assessment of Sperm Motility

4.4. Assessment of Sperm Plasma Membrane Integrity (SYBR-14/PI)

4.5. Assessment of Sperm Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (JC-1/PI)

4.6. Assessment of Nitric Oxide (NO)-Generating Spermatozoa (DAF-2DA)

4.7. Antioxidant Enzyme Triad

4.8. Determination of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity

4.9. Determination of Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) Activity

4.10. Determination of Catalase (CAT) Activity

4.11. Determination of Glutathione (GSH) Content

4.12. Determination of Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content

4.13. Determination of Zinc Content

4.14. Analysis of Turkey Semen Protein Profiles by Two Separation Methods

4.14.1. SDS-PAGE Electrophoresis

4.14.2. TRICINE-PAGE Electrophoresis

4.15. Identification of Selected Proteins by Nano LC-MS/MS Mass Spectrometry

4.16. Functional Analysis of Identified Proteins

4.17. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- King’ori, A.M. Review of the factors that influence egg fertility and hatchability in poultry. Int. J Poult. Sci. 2011, 10, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, J.L.; Wen, J.; Zhao, G.P.; Zheng, M.Q.; Liu, R.R.; Liu, W.P.; Zhao, L.H.; Liu, G.F.; Wang, Z.W. Estimation of the genetic parameters of semen quality in Beijing-You chickens. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92(10), 2606–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.hybridturkeys.com/en/news/new-laying-standards-released-for-the-hybrid-converternovo/.

- Grimes, J.L.; Noll, S.; Brannon, J.; Godwin, J.L.; Smith, J.C.; Rowland, R.D. Effect of a chelated calcium proteinate dietary supplement on the reproductive performance of Large White Turkey breeder hens. J Appl. Poult. Res. 2004, 13, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.S.; Rakha, B.A.; Akhter, S.; Akhter, A.; Blesbois, E.; Santiago-Moreno, J. Effect of glutathione on pre- and post-freezing sperm quality of Indian red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus murghi). Theriogenology 2021, 172, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, N.J.; Boonkum, W.; Chankitisakul, V. Semen Quality Traits of Two Thai Native Chickens Producing a High and a Low of Semen Volumes. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10(2), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszewicz, E. Artificial insemination - the method assisting reproduction of birds. Rocz. Nauk. Pol. Tow. Zootech. 2006, 2(1), 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- McGary, S.; Estevez, I.; Bakst, M.R.; Pollock, D.L. Phenotypic traits as reliable indicators of fertility in male broiler breeders. Poult. Sci. 2002, 81(1), 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyisa, S.G.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, B.R.; Jung, K.M.; Choi, S.B.; Cho, C.Y.; Han, J.Y. Morphological defects of sperm and their association with motility, fertility, and hatchability in four Korean native chicken breeds. Asian-Australas. J Anim. Sci. 2018 31(8), 1160-1168. [CrossRef]

- Bakst, M.R.; Welch, G.R.; Camp, M.J. Observations of turkey eggs stored up to 27 days and incubated for 8 days: embryo developmental stage and weight differences and the differentiation of fertilized from unfertilized germinal discs. Poult Sci, 2016, 95(5), 1165-1172. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.G.; Storey, B.T. Differential incorporation of fatty acids into and peroxidative loss of fatty acids from phospholipids of human spermatozoa. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1995, 42(3), 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Virk, G.; Ong, C.; du Plessis, S.S. Effect of oxidative stress on male reproduction. World J. Mens Health. 2014, 32(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Partyka, A.; Lukaszewicz, E.; Niżański, W. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes activity in avian semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 134(3-4), 184-90. [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, A.M.; Sonstegard, T.S.; King, L.M.; Smith, E.J.; Burt, D.W. Turkey sperm mobility influences paternity in the context of competitive fertilization. Biol. Reprod. 1999, 61(2), 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Xue, F.; Li, Y.; Fu, L.; Bai, H.; Ma, H.; Xu, S.; Chen, J. Differences in semen quality, testicular histomorphology, fertility, reproductive hormone levels, and expression of candidate genes according to sperm motility in Beijing-You chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98(9), 4182–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frączek, M.; Kurpisz, M. The redox system in human semen and peroxidative damage of spermatozoa. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. (Online) 2005, 59, 523–34. [Google Scholar]

- Froman, D.P.; Thurston, R.J. Chicken and turkey spermatozoal superoxide dismutase: a comparative study. Biol. Reprod. 1981, 24(1), 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partyka, A.; Niżański, W. Supplementation of Avian Semen Extenders with Antioxidants to Improve Semen Quality-Is It an Effective Strategy? Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10(12), 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surai, P.F. Antioxidant Systems in Poultry Biology: Superoxide Dismutase. J Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.R. Critical Role of Zinc as Either an Antioxidant or a Prooxidant in Cellular Systems. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 20, 9156285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.A.; Kikusato, M.; Maekawa, T.; Shirakawa, H.; Toyomizu, M. Metabolic characteristics and oxidative damage to skeletal muscle in broiler chickens exposed to chronic heat stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2010, 155(3), 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, N.K.; Morshedi, M.; Oehninger, S. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on DNA and plasma membrane integrity of human spermatozoa. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 74(6), 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Riquelme, N.; Huerta-Retamal, N.; Gómez-Torres, M.J.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Catalase as a Molecular Target for Male Infertility Diagnosis and Monitoring: An Overview. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisol, L.; Matorras, R.; Aspichueta, F.; Expósito, A.; Hernández, M.L.; Ruiz-Larrea, M.B.; Mendoza, R.; Ruiz-Sanz, J.I. Glutathione peroxidase activity in seminal plasma and its relationship to classical sperm parameters and in vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 97(4), 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujianto D.A.; Oktarina M.; Sharma Sharaswati I.A.; Yulhasri. Hydrogen Peroxide Has Adverse Effects on Human Sperm Quality Parameters, Induces Apoptosis, and Reduces Survival. J Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 14(2), 121-128. [CrossRef]

- Orzołek, A.; Rafalska, K.T.; Dziekońska, A.; Rafalska, A.; Zawadzka, M. How Do Taurine and Ergothioneine Additives Improve the Parameters of High- And Low-Quality Turkey Semen During Liquid Preservation? Ann. Anim. Sci. 2025, 25(2), 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atig, F.; Raffa, M.; Habib, B.A; Kerkeni, A.; Saad, A.; Ajina, M. Impact of seminal trace element and glutathione levels on semen quality of Tunisian infertile men. BMC Urol 2012, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochsendorf, F.R.; Buhl, R.; Bästlein, A.; Beschmann, H. Glutathione in spermatozoa and seminal plasma of infertile men. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 13, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafula, R.V.; Onufrovych, O.K.; Iefremova, U.P.; Melnyk, O.V.; Nakonechnyi, I.A.; Vorobets, D.Z.; Vorobets, Z.D. Glutathione content in sperm cells of infertile men. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2017, 8(2), 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, E.; Nikzad, H.; Karimian, M. Oxidative stress and male infertility: Current knowledge of pathophysiology and role of antioxidant therapy in disease management. Cell Mol Life Sci 2020, 77(1), 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucak, M.N.; Sarıözkan, S.; Tuncer, P.B.; Sakin, F.; Ateşşahin, A.; Kulaksız, R.; Çevik, M. The effect of antioxidants on post-thawed Angora goat (Capra hircus ancryrensis) sperm parameters, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant activities. Small. Rumin. Res. 2010, 89, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Filho, I.C.; Pasini, M.; Moura, A.A. Spermatozoa and seminal plasma proteomics: Too many molecules, too few markers. The case of bovine and porcine semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 247, 107075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, C. Peroxiredoxin 6: The Protector of Male Fertility. Antioxidants (Basel) 2018, 7(12), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.B. Peroxiredoxin 6 in the repair of peroxidized cell membranes and cell signalling. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 617, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, A.R.; Fernandez, M.C.; Scarlata, E.; Dodia, C.; Feinstein, S.I.; Fisher, A.B.; O’Flaherty, C. Deficiency of peroxiredoxin 6 or inhibition of its phospholipase A2 activity impair the in vitro sperm fertilizing competence in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lamirande, E.; Gagnon, C. Reactive oxygen species and human spermatozoa. II. Depletion of adenosine triphosphate plays an important role in the inhibition of sperm motility. J. Androl. 1992, 13, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Do, H.L.; Chandimali, N.; Lee, S.B.; Mok, Y.S.; Kim, N.; Kim, S.B.; Kwon, T.; Jeong, D.K. Non-thermal plasma treatment improves chicken sperm motility via the regulation of demethylation levels. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8(1), 7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafalska, K.T.; Orzołek, A.; Ner-Kluza, J.; Wysocki, P. A Comparison of White and Yellow Seminal Plasma Phosphoproteomes Obtained from Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) Semen. Int. J Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafalska, K.T.; Orzołek, A.; Ner-Kluza, J.; Wysocki, P. Does the Type of Semen Affect the Phosphoproteome of Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) Spermatozoa? Int. J Mol. Sci. 2025, 26(8), 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhoberac, B.B.; Vidal, R. Iron, ferritin, hereditary ferritinopathy, and neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Yuge, M.; Uda, A.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Orino, K. Structural and functional analyses of chicken liver ferritin. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolea, F.; Biamonte, F.; Candeloro, P.; Di Sanzo, M.; Cozzi, A.; Di Vito, A.; Quaresima, B.; Lobello, N.; Trecroci, F.; Di Fabrizio, E. H ferritin silencing induces protein misfolding in K562 cells: a Raman analysis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orino, K.; Lehman, L.; Tsuji, Y.; Ayaki, H.; Torti, S.V.; Torti, F.M. Ferritin and the response to oxidative stress. Biochem. J 2001, 357, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scirè, A.; Cianfruglia, L.; Minnelli, C.; Romaldi, B.; Laudadio, E.; Galeazzi, R.; Antognelli, C.; Armeni, T. Glyoxalase 2: Towards a Broader View of the Second Player of the Glyoxalase System. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, M.R.; Hedges, S.B. Evolutionary history of the enolase gene family. Gene 2000, 259, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Wang, J.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Lian, S.; Guo, W.; Yang, H.; Kong, F.; Zhen, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y. Progress in the biological function of alpha-enolase. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 2(1), 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graven, K.K.; Zimmerman, L.H.; Dickson, E.W.; Weinhouse, G.L.; Farber, H.W. Endothelial cell hypoxia associated proteins are cell and stress specific. J Cell Physiol. 1993, 157, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, GJ. Maintenance of ATP concentrations in and of fertilizing ability of fowl and turkey spermatozoa in vitro. J Reprod. Fertil. 1982, 66(2), 457–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernansanz-Agustín, P.; Izquierdo-Álvarez, A.; Sánchez-Gómez, F.J.; Ramos, E.; Villa-Piña, T.; Lamas, S.; Bogdanova, A.; Martínez-Ruiz, A. Acute hypoxia produces a superoxide burst in cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 71, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R.A.; Elliott, T.J. Stress proteins, infection, and immune surveillance. Cell 1989, 59, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucker, D.S.; Jain, M.R.; Pattabiraman, G.; Palasiewicz, K.; Birge, R.B.; Li, H. Externalized glycolytic enzymes are novel, conserved, and early biomarkers of apoptosis. J Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 10625–10343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazdova, A.; Vermachova, M.; Zidkova, J.; Ulcova-Gallova, Z.; Peltre, G. Immunodominant semen proteins I: New patterns of sperm proteins related to female immune infertility. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2013, 8, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarsono, T;, Supriatna, I.; Setiadi, M. A.; Agil, M.; Purwantara B. Detection of Plasma Membrane Alpha Enolase (ENO1) and Its Relationship with Sperm Quality of Bali Cattle. Trop. Anim. Sci. J, 2023, 46(1), 36-42. [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, A.R. Role for Beta 2 Microglobulin in Speciation, Editor(s): H. PEETERS, Protides of the Biological Fluids, Elsevier 1985, 32, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Tang, F.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.F.; Li, Z.Q. Serum beta2-microglobulin acts as a biomarker for severity and prognosis in glioma patients: a preliminary clinical study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24(1), 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana, J.; Eneroth, P.; Byström, B.; Bygdeman, B. Seminal Plasma Levels of Beta2-Microglobulin and Cea-Like Protein in Infertility, Editor(s): H. PEETERS, Protides of the Biological Fluids, Elsevier 1982, 29, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chard, T.; Parslow, J.; Rehmann, T.; Dawnay, A. The concentrations of transferrin, β2-microglobulin, and albumin in seminal plasma in relation to sperm count. Fertil. Steril. 1991, 55(1), 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamponi, V.; Mazzilli, R.; Olana, S.; Russo, F.; Mancini, C.; Faggiano, A.; Salerno, G. The impact of pharmacological treatments on oxidative stress, inflammatory parameters and semen characteristics. Endocr. Abstr. 2023, 90, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Han, X.; Yuan, J.; Ma, L.; Ma, H.; Chen, J. Mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase (GOT2) protein as a potential cryodamage biomarker in rooster spermatozoa cryopreservation. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104(2), 104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuhashi, M.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Fatty Acid-Binding Proteins: Role in Metabolic Diseases and Potential as Drug Targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkoe, T.M.; Mechtler, T.P.; Weninger, M.; Pones, M.; Rebhandl, W.; Kasper, D.C. Serum Levels of Interleukin-8 and Gut-Associated Biomarkers in Diagnosing Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Preterm Infants. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 49, 1446–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Kagawa, Y.; Miyazaki, H.; Shil, S.K.; Umaru, B.A.; Yasumoto, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Owada, Y. FABP7 Protects Astrocytes Against ROS Toxicity via Lipid Droplet Formation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 5763–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, R.A.; Thurston, R.J., Biellier, H.V. Morphology of the epididymal region of turkeys producing abnormal yellow semen. Poult. Sci. 1982, 61(3), 531-539. [CrossRef]

- Atikuzzaman, M.; Sanz, L.; Pla, D.; Alvarez-Rodriguez, M.; Rubér, M.; Wright, D.; Calvete, J.J.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H. Selection for higher fertility reflects in the seminal fluid proteome of modern domestic chicken. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 2017, 21, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.V.; Soler, L.; Thélie, A.; Grasseau, I.; Cordeiro, L.; Tomas, D.; Teixeira-Gomes, A.P.; Labas, V.; Blesblois, E. Proteomic Changes Associated With Sperm Fertilizing Ability in Meat-Type Roosters. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 655866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenol, A.; Delezie, E.; Wang, Y.; Franssens, L.; Willems, E.; Ampe, B.; Everaert, N. Effects of maternal dietary EPA and DHA supplementation and breeder age on embryonic and post-hatch performance of broiler offspring. J Anim. Physiol. An. N. 2015, 99(1), 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.D.; Lorenz, F.W.; Asmundson, V.S. Semen production in the turkey male. Semen Production in the Turkey Male: 2. Age at Sexual Maturity. Poult. Sci. 1955, 34(2), 344-347. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, D.; Paudel, S.; Sapkota, S.; Shrestha, S.; Poudel, N.; Bhattari, N. Performance of egg production, fertility and hatchability of turkey in different production systems. J. Nep. Agric. Res. Counc. 2024, 10(1), 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.aviagen.com/assets/Tech_Center/BB_Resources_Tools/Hatchery_How_Tos/04HowTo4-IdentifyInfertileEggsandEarlyDeads.pdf.

- Burrows, W.H.; Quinn, J.P. The collection of spermatozoa from the domestic fowl and turkey. Poult. Sci. 1937, 16, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.L.; Johnson, L.A. Viability assessment of mammalian sperm using SYBR-14 and propidium iodide. Biol. Reprod. 1995, 53(2), 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampiao, F.; Strijdom, H.; du Plessis, S.S. Direct nitric oxide measurement in human spermatozoa: flow cytometric analysis using the fluorescent probe, diaminofluorescein. Int. J Androl. 2006, 29(5), 564–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | GF | IF |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm concentration (x109) | 4.7 ± 1.0* | 5.6 ± 1.7* |

| PMI (%) | 88.4 ± 4.6** | 78.4 ± 6.8** |

| MMP (%) | 79.7 ± 6.2 | 79.9 ± 7.9 |

| NO (%) | 29.3 ± 11.2* | 42.4 ± 19.0* |

| TMOT (%) | 81.2 ± 6.6** | 71.7 ± 8.5** |

| PMOT (%) | 49.7 ± 13.2 | 46.3 ± 24.6 |

| VAP (µm/s) | 74.0 ± 3.7 | 80.3 ± 13.3 |

| VSL (µm/s) | 70.7 ± 5.4 | 73.9 ± 15.0 |

| VCL (µm/s) | 116.8 ± 8.9* | 105.9 ± 14.4* |

| ALH (µm) | 3.59 ± 0.5 | 3.29 ± 0.6 |

| BCF (Hz) | 22.4 ±8.3 | 18.7 ± 6.8 |

| STR (%) | 81.6 ± 6.0** | 90.3 ± 5.3** |

| LIN (%) | 66.7 ± 6.3 | 71.7 ± 8.5 |

| Parameters | GF | IF |

|---|---|---|

| Total protein (mg/mL) | 7.9 ± 2.0** | 5.6 ± 1.4** |

| SOD activity (U/mL) | 2.4 ± 0.6** | 1.1 ± 0.4** |

| GPx activity (U/mL) | 0.4 ± 0.1** | 0.2 ± 0.1** |

| CAT activity (µM/min/mL) | 14.4 ± 10.3* | 39.2 ± 29.9* |

| GSH (M/mL) | 0.5 ± 0.02** | 0.9 ± 0.03** |

| MDA (µM/mL) | 11.5 ± 11.7** | 28.4 ± 12.2** |

| Zn2+ (mg %) | 151.9 ± 58.9** | 49.7 ± 24.6** |

| Parameters | GF | IF |

|---|---|---|

| SOD activity (U/mL) | 0.6 ± 0.2** | 1.2 ± 0.5** |

| GPx activity (U/mL) | 0.4 ± 0.1** | 0.2 ± 0.2** |

| CAT activity (µM/min/mL) | 114.3 ± 59.4* | 70.1 ± 44.5* |

| GSH (M/mL) | 0.2 ± 0.08** | 0.1 ± 0.07** |

| MDA (µM/mL) | 6.1 ± 4.3** | 14.8 ± 6.1** |

| Zn2+ (mg %) | 43.6 ± 12.1* | 92.2 ± 64.3* |

| Protein [kDa] |

GF | IF |

|---|---|---|

| 107 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.03 |

| 80 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 |

| 49 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.01 |

| 41 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.01 |

| 29 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.02 |

| 26 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.02 |

| 25 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.01 |

| 18 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.04 |

| 16 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.02 |

| 12 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| Protein [kDa] |

GF | IF |

|---|---|---|

| 107 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.01 |

| 52 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| 49 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 0.68 ± 0.01 |

| 41 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.01 |

| 29 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.03 |

| 25 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| 18 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.02 |

| 16 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.02 |

| Molecular weight [kDa] |

Identified protein | Gene | Species | Molecular weight (Mascot) [Da] |

No. of matched peptides | Sequence coverage [%] |

Score |

| 26 | Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 20 | 31 | 974 |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | PGAM1 | Gallus gallus | 29051 | 16 | 24 | 807 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 13 | 17 | 681 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 12 | 16 | 589 | |

| 14-3-3 protein zeta | YWHAZ | Gallus gallus | 27929 | 13 | 13 | 561 | |

| 14-3-3 protein theta | YWHAQ | Gallus gallus | 28050 | 10 | 10 | 436 | |

| Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | ASTL | Gallus gallus | 46929 | 12 | 9 | 404 | |

| 14-3-3 protein epsilon | YWHAE | Gallus gallus | 29326 | 8 | 9 | 400 | |

| Gelsolin | GSN | Gallus gallus | 86120 | 8 | 8 | 369 | |

| Peroxiredoxin-6 | PRDX6 | Gallus gallus | 25075 | 12 | 7 | 351 | |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | QSOX1 | Gallus gallus | 83939 | 8 | 11 | 312 | |

| Clusterin | CLU | Coturnix japonica | 52395 | 3 | 8 | 266 | |

| Hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolase, mitochondrial | HAGH | Gallus gallus | 34545 | 5 | 6 | 235 | |

| 14-3-3 protein gamma | YWHAG | Gallus gallus | 28384 | 4 | 6 | 209 | |

| SPARC protein | SPARC | Gallus gallus | 34894 | 3 | 5 | 164 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 3 | 5 | 161 | |

| 14-3-3 protein beta/alpha | YWHAB | Gallus gallus | 28004 | 3 | 4 | 131 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | COL12A1 | Gallus gallus | 341740 | 3 | 3 | 121 | |

| Tubulin beta-3 chain | TBB3 | Gallus gallus | 50285 | 5 | 2 | 120 | |

| Tubulin beta-7 chain | TBB7 | Gallus gallus | 50095 | 5 | 2 | 120 | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Gallus gallus | 35909 | 2 | 1 | 96 | |

| 1-phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase zeta-1 | PLCZ1 | Gallus gallus | 73285 | 2 | 1 | 94 | |

|

25 25 |

Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 24 | 38 | 1123 |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 12 | 27 | 748 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 14 | 21 | 670 | |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | TPI1 | Gallus gallus | 26832 | 11 | 18 | 499 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | ACTG1 | Gallus gallus | 42108 | 9 | 13 | 394 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic type 5 | ACT5 | Gallus gallus | 42151 | 9 | 13 | 394 | |

| Ras-related protein Rab-5B | RAB5B | Gallus gallus | 23828 | 8 | 10 | 323 | |

| Ras-related protein Rab-5C | RAB5C | Gallus gallus | 23767 | 8 | 9 | 304 | |

| Clusterin | CLU | Coturnix japonica | 52395 | 4 | 9 | 300 | |

| Peroxiredoxin-6 | PRDX6 | Gallus gallus | 25075 | 9 | 12 | 272 | |

| Ras-related protein Rab-10 | RAB10 | Gallus gallus | 22763 | 6 | 11 | 257 | |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | PGAM1 | Gallus gallus | 29051 | 5 | 8 | 252 | |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | QSOX1 | Gallus gallus | 83939 | 4 | 9 | 202 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | COL12A1 | Gallus gallus | 341740 | 5 | 9 | 200 | |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | APOA1 | Gallus gallus | 30661 | 9 | 6 | 196 | |

| Tubulin alpha-1 chain | TUBA1 | Gallus gallus | 46385 | 5 | 5 | 194 | |

| 14-3-3 protein zeta | YWHAZ | Gallus gallus | 27929 | 4 | 8 | 168 | |

| Mitochondria-eating protein | SPATA18 | Gallus gallus | 54997 | 2 | 9 | 166 | |

| Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | ASTL | Gallus gallus | 46929 | 4 | 9 | 160 | |

| Ferritin heavy chain | FTH | Gallus gallus | 21249 | 5 | 8 | 159 | |

| Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase | HPRT1 | Gallus gallus | 24878 | 3 | 7 | 146 | |

| Carbonic anhydrase 2 | CA2 | Gallus gallus | 29388 | 3 | 6 | 134 | |

| Translin | TSN | Gallus gallus | 26002 | 2 | 11 | 132 | |

| Hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolase, mitochondrial | HAGH | Gallus gallus | 34545 | 2 | 5 | 123 | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Gallus gallus | 35909 | 2 | 4 | 122 | |

| Adenylate kinase isoenzyme 1 | AK1 | Gallus gallus | 21783 | 2 | 4 | 106 | |

| Tubulin beta-1 chain | TBB1 | Gallus gallus | 50333 | 3 | 3 | 102 | |

| Tubulin beta-2 chain | TBB2 | Gallus gallus | 50377 | 3 | 3 | 102 | |

| Tubulin beta-3 chain | TBB3 | Gallus gallus | 50285 | 3 | 3 | 102 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 3 | 3 | 102 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 3 | 3 | 102 | |

| Tubulin beta-6 chain | TBB6 | Gallus gallus | 50692 | 3 | 3 | 102 | |

| Tubulin beta-7 chain | TBB7 | Gallus gallus | 50095 | 3 | 3 | 102 | |

| Protein-L-isoaspartate(D-aspartate) O-methyltransferase | PCMT1 | Gallus gallus | 24790 | 1 | 1 | 100 | |

|

18

18 |

Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 20 | 45 | 1810 |

| Tubulin beta-3 chain | TBB3 | Gallus gallus | 50285 | 21 | 37 | 1507 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 19 | 32 | 1321 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 15 | 23 | 1232 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 12 | 19 | 917 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 10 | 17 | 799 | |

| Creatine kinase S-type, mitochondrial | CKMT2 | Gallus gallus | 47510 | 9 | 15 | 687 | |

| Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 | VDAC2 | Meleagris gallopavo | 30162 | 9 | 14 | 545 | |

| Tubulin alpha-4 chain | TBA4 | Gallus gallus | 36483 | 9 | 12 | 465 | |

| Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit Rieske, mitochondrial | UQCRFS1 | Gallus gallus | 29710 | 7 | 11 | 395 | |

| Cilia- and flagella-associated protein 20 | CFAP20 | Gallus gallus | 22891 | 6 | 11 | 298 | |

| Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein eS31 fusion protein | RPS27A | Gallus gallus | 18310 | 6 | 9 | 237 | |

| Polyubiquitin-B | UBB | Gallus gallus | 34348 | 6 | 9 | 237 | |

| Ferritin heavy chain | FTH | Gallus gallus | 21249 | 5 | 8 | 199 | |

| Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulphur subunit | SDHB | Gallus gallus | 33374 | 5 | 5 | 194 | |

| Retinol-binding protein 4 | RBP4 | Gallus gallus | 22843 | 4 | 4 | 162 | |

| Lysozyme g | LYZ | Gallus gallus | 23565 | 3 | 4 | 132 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 3 | 3 | 101 | |

| Zona pellucida-binding protein 1 | ZPBP1 | Gallus gallus | 36910 | 4 | 2 | 99 | |

| T-complex protein 1 subunit theta | CCT8 | Gallus gallus | 60017 | 2 | 1 | 94 | |

|

16 16 |

Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 52 | 60 | 1967 |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 21 | 45 | 891 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 18 | 44 | 881 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 15 | 43 | 594 | |

| Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | ASTL | Gallus gallus | 46929 | 15 | 41 | 519 | |

| Gelsolin | GSN | Gallus gallus | 86120 | 10 | 39 | 431 | |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | QSOX1 | Gallus gallus | 83939 | 12 | 34 | 405 | |

| Ferritin heavy chain | FTH | Gallus gallus | 21249 | 16 | 27 | 397 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 15 | 24 | 382 | |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | APOA1 | Gallus gallus | 30661 | 14 | 18 | 358 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 12 | 15 | 308 | |

| 1-phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase zeta-1 | PLCZ1 | Gallus gallus | 73285 | 7 | 14 | 252 | |

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B | PPIB | Gallus gallus | 22456 | 7 | 11 | 232 | |

| Transthyretin | TTR | Gallus gallus | 16356 | 7 | 13 | 204 | |

| Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | HSP90AA1 | Gallus gallus | 84406 | 6 | 10 | 192 | |

| Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | HSPA8 | Gallus gallus | 71011 | 6 | 9 | 187 | |

| Proteasome subunit beta type-5 | PSMB5 | Gallus gallus | 27256 | 4 | 7 | 159 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | COL12A1 | Gallus gallus | 341740 | 3 | 7 | 156 | |

| Heat shock 70 kDa protein | HSP70 | Gallus gallus | 69936 | 6 | 5 | 172 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | ACTB | Gallus gallus | 42052 | 2 | 2 | 116 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | ACTG2 | Gallus gallus | 42108 | 2 | 2 | 116 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic type 5 | ACT5 | Gallus gallus | 42151 | 2 | 2 | 116 | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Gallus gallus | 35909 | 2 | 3 | 104 | |

| Peroxiredoxin-6 | PRDX6 | Gallus gallus | 25075 | 4 | 2 | 100 |

| Molecular weight [kDa] |

Identified protein | Gene | Species | Molecular weight (Mascot) [Da] |

No. of matched peptides | Sequence coverage [%] |

Score |

| 107 | Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 39 | 41 | 1575 |

| Aminopeptidase Ey | ANPEP | Gallus gallus | 109406 | 38 | 35 | 1555 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | COL12A1 | Gallus gallus | 341740 | 27 | 32 | 1057 | |

| Alpha-enolase | ENO1 | Gallus gallus | 47617 | 23 | 31 | 870 | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic | GOT1 | Gallus gallus | 46134 | 12 | 19 | 556 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 8 | 12 | 440 | |

| Clusterin | CLU | Coturnix japonica | 52395 | 4 | 9 | 275 | |

| L-lactate dehydrogenase B | LDHB | Gallus gallus | 36694 | 8 | 4 | 265 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 5 | 6 | 259 | |

| NEL protein | NEL | Gallus gallus | 96096 | 5 | 5 | 246 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 6 | 4 | 236 | |

| Gelsolin | GSN | Gallus gallus | 86120 | 5 | 4 | 234 | |

| Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | HSPA8 | Gallus gallus | 71011 | 6 | 3 | 224 | |

| Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | ASTL | Gallus gallus | 46929 | 5 | 3 | 217 | |

| Fibrinogen beta chain | FGB | Gallus gallus | 53272 | 4 | 3 | 194 | |

| Transforming growth factor beta-2 proprotein | TGFB2 | Gallus gallus | 48431 | 3 | 8 | 182 | |

| Neuronal growth regulator 1 | NEGR1 | Gallus gallus | 38434 | 4 | 2 | 179 | |

| Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | NDK | Gallus gallus | 17448 | 2 | 2 | 137 | |

| Translin | TSN | Gallus gallus | 26002 | 7 | 1 | 131 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 2 | 2 | 91 | |

| Lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 1 | LAMP1 | Gallus gallus | 45097 | 2 | 2 | 91 | |

|

80 80 |

Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 32 | 39 | 1384 |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | COL12A1 | Gallus gallus | 341740 | 17 | 22 | 677 | |

| Cytoplasmic aconitate hydratase | ACO1 | Gallus gallus | 98639 | 11 | 18 | 551 | |

| Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | HSP90AA1 | Gallus gallus | 84406 | 13 | 17 | 455 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 8 | 12 | 387 | |

| Elongation factor 2 | EEF2 | Gallus gallus | 96343 | 10 | 9 | 358 | |

| Alpha-actinin-4 | ACTN4 | Gallus gallus | 104712 | 8 | 8 | 323 | |

| Endoplasmin | HSP90B1 | Gallus gallus | 91726 | 9 | 8 | 305 | |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | QSOX1 | Gallus gallus | 83939 | 8 | 6 | 299 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 7 | 5 | 271 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 3 | 5 | 226 | |

| Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein eS31 fusion protein | RPS27A | Gallus gallus | 18310 | 2 | 3 | 128 | |

| Polyubiquitin-B | UBB | Gallus gallus | 34348 | 2 | 3 | 128 | |

| Laminin subunit beta-1 | LAMB1 | Gallus gallus | 35775 | 1 | 1 | 95 | |

| 49 | Alpha-enolase | ENO1 | Gallus gallus | 47617 | 68 | 42 | 2660 |

| Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 32 | 31 | 1497 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 27 | 28 | 1082 | |

| Gamma-enolase | ENO2 | Gallus gallus | 47621 | 17 | 23 | 777 | |

| Tubulin alpha-1 chain | TUBA1 | Gallus gallus | 46385 | 18 | 17 | 674 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 15 | 16 | 563 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 15 | 16 | 494 | |

| ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial | ATP5B | Gallus gallus | 56650 | 15 | 10 | 488 | |

| Tubulin alpha-5 chain | TBA5 | Gallus gallus | 50715 | 10 | 12 | 446 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 8 | 11 | 404 | |

| Elongation factor 1-alpha | EEF1A | Gallus gallus | 50467 | 10 | 9 | 285 | |

| Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-II | EIF4A2 | Gallus gallus | 46570 | 6 | 8 | 225 | |

| Bleomycin hydrolase | BLMH | Gallus gallus | 53397 | 5 | 7 | 221 | |

| Na(+)/H(+) exchange regulatory cofactor NHE-RF1 | NHERF1 | Gallus gallus | 36011 | 6 | 4 | 201 | |

| Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein eS31 fusion protein | RPS27A | Gallus gallus | 18310 | 2 | 3 | 139 | |

| Polyubiquitin-B | UBB | Gallus gallus | 34348 | 2 | 3 | 139 | |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | QSOX1 | Gallus gallus | 83939 | 2 | 2 | 117 | |

| Lissencephaly-1 homolog | PAFAH1B1 | Gallus gallus | 47204 | 2 | 2 | 114 | |

| Neuroserpin | SERPINI1 | Gallus gallus | 46556 | 3 | 1 | 109 | |

| 41 | Transthyretin | TTR | Gallus gallus | 16356 | 24 | 32 | 878 |

| Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 7 | 23 | 327 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 3 | 15 | 279 | |

| Beta-2-microglobulin | B2M | Meleagris gallopavo | 11225 | 5 | 13 | 268 | |

| Fatty acid-binding protein, brain | FABP7 | Gallus gallus | 15031 | 6 | 11 | 255 | |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | QSOX1 | Gallus gallus | 83939 | 3 | 9 | 140 | |

|

29 29 |

Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 22 | 29 | 1009 |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | QSOX1 | Gallus gallus | 83939 | 22 | 25 | 844 | |

| Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | ASTL | Gallus gallus | 46929 | 17 | 22 | 575 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 11 | 18 | 566 | |

| Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 13 | 16 | 543 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 12 | 15 | 434 | |

| Transthyretin | TTR | Gallus gallus | 16356 | 10 | 15 | 406 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 7 | 14 | 343 | |

| Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | HSP90AA1 | Gallus gallus | 84406 | 9 | 13 | 331 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 5 | 13 | 324 | |

| L-lactate dehydrogenase B chain | LDHB | Gallus gallus | 36694 | 8 | 11 | 323 | |

| Clusterin | CLU | Coturnix japonica | 52395 | 5 | 11 | 301 | |

| Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 | VDAC2 | Meleagris gallopavo | 30162 | 5 | 10 | 288 | |

| Annexin A2 | ANXA2 | Gallus gallus | 38901 | 5 | 9 | 263 | |

| Annexin A5 | ANXA5 | Gallus gallus | 36290 | 7 | 8 | 248 | |

| SPARC protein | SPARC | Gallus gallus | 34894 | 4 | 7 | 192 | |

| Golgi apparatus protein 1 | GLG1 | Gallus gallus | 133560 | 4 | 6 | 189 | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Gallus gallus | 35909 | 3 | 6 | 177 | |

| Transthyretin | TTR | Gallus gallus | 16356 | 3 | 6 | 173 | |

| Malate dehydrogenase, cytoplasmic | MDH1 | Gallus gallus | 36748 | 4 | 5 | 169 | |

| T-complex protein 1 subunit theta | CCT8 | Gallus gallus | 60017 | 2 | 5 | 157 | |

| 14-3-3 protein zeta | YWHAZ | Gallus gallus | 27929 | 3 | 4 | 129 | |

| L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain | LDHA | Gallus gallus | 36776 | 2 | 4 | 126 | |

| 1-phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase zeta-1 | PLCZ1 | Gallus gallus | 73285 | 2 | 3 | 110 | |

| 14-3-3 protein gamma | YWHAG | Gallus gallus | 28384 | 2 | 3 | 101 | |

| Receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase gamma | PTPRG | Gallus gallus | 160750 | 2 | 3 | 98 | |

|

12 12 |

Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 14 | 21 | 799 |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 11 | 22 | 608 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 10 | 18 | 425 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 10 | 16 | 296 | |

| Beta-2-microglobulin | B2M | Meleagris gallopavo | 11225 | 6 | 13 | 282 | |

| Fatty acid-binding protein, brain | FABP7 | Gallus gallus | 15031 | 5 | 11 | 280 | |

| Cystatin | CYT | Gallus gallus | 15562 | 8 | 16 | 268 | |

| Ras-related protein Rab-2A | RAB2A | Gallus gallus | 23678 | 4 | 12 | 240 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 8 | 12 | 236 | |

| Lysozyme C | LYZ | Gallus gallus | 16741 | 2 | 11 | 226 | |

| Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | ASTL | Gallus gallus | 46929 | 6 | 10 | 222 | |

| Vesicle-trafficking protein SEC22b | SEC22B | Gallus gallus | 24873 | 4 | 8 | 188 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 3 | 6 | 165 | |

| Transthyretin | TTR | Gallus gallus | 16356 | 3 | 5 | 145 | |

| Gelsolin | GSN | Gallus gallus | 86120 | 3 | 4 | 145 | |

| Cytochrome c | CYC | Gallus gallus | 11817 | 4 | 3 | 142 | |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | APOA1 | Gallus gallus | 30661 | 5 | 3 | 130 | |

| Ig lambda chain C region | LAC | Gallus gallus | 11525 | 2 | 2 | 115 | |

| Prosaposin | PSAP | Gallus gallus | 59444 | 2 | 1 | 106 | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Gallus gallus | 35909 | 2 | 1 | 98 |

| Molecular weight [kDa] |

Identified protein | Gene | Species | Molecular weight (Mascot) [Da] |

No. of matched peptides | Sequence coverage [%] |

Score |

| 25 | Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 21 | 41 | 1067 |

| Peroxiredoxin-6 | PRDX6 | Gallus gallus | 25075 | 19 | 32 | 1024 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 17 | 26 | 950 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 16 | 24 | 913 | |

| Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | ASTL | Gallus gallus | 46929 | 14 | 27 | 888 | |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | TPI1 | Gallus gallus | 26832 | 17 | 18 | 807 | |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | PGAM1 | Gallus gallus | 29051 | 15 | 18 | 767 | |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | QSOX1 | Gallus gallus | 83939 | 14 | 19 | 702 | |

| Carbonic anhydrase 2 | CA2 | Gallus gallus | 29388 | 13 | 16 | 634 | |

| Clusterin | CLU | Coturnix japonica | 52395 | 13 | 19 | 600 | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Gallus gallus | 35909 | 12 | 14 | 548 | |

| Adenylate kinase isoenzyme 1 | AK1 | Gallus gallus | 21783 | 12 | 14 | 534 | |

| Tubulin beta-1 chain | TBB1 | Gallus gallus | 50333 | 12 | 13 | 509 | |

| Tubulin beta-2 chain | TBB2 | Gallus gallus | 50377 | 11 | 13 | 499 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | COL12A1 | Gallus gallus | 341740 | 10 | 9 | 380 | |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | APOA1 | Gallus gallus | 30661 | 9 | 6 | 305 | |

| Glutathione S-transferase 5 | GST5 | Gallus gallus | 25282 | 9 | 10 | 287 | |

| Tubulin alpha-1 chain | TUBA1 | Gallus gallus | 46385 | 9 | 9 | 284 | |

| 14-3-3 protein zeta | YWHAZ | Gallus gallus | 27929 | 9 | 8 | 278 | |

| Mitochondria-eating protein | SPATA18 | Gallus gallus | 54997 | 7 | 9 | 276 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 8 | 8 | 269 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | ACTG1 | Gallus gallus | 42108 | 7 | 11 | 264 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic type 5 | ACT5 | Gallus gallus | 42151 | 7 | 11 | 264 | |

| Ras-related protein Rab-5B | RAB5B | Gallus gallus | 23828 | 3 | 10 | 206 | |

| Ras-related protein Rab-5C | RAB5C | Gallus gallus | 23767 | 3 | 9 | 198 | |

| Ras-related protein Rab-10 | RAB10 | Gallus gallus | 22763 | 2 | 11 | 158 | |

| Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit Rieske, mitochondrial | UQCRFS1 | Gallus gallus | 29710 | 1 | 4 | 102 | |

| Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | HSP90AA1 | Gallus gallus | 84406 | 1 | 3 | 99 | |

| 18 | Tubulin beta-3 chain | TBB3 | Gallus gallus | 50285 | 24 | 40 | 1850 |

| Tubulin beta-2 chain | TBB2 | Gallus gallus | 50377 | 26 | 22 | 1608 | |

| Tubulin beta-7 chain | TBB7 | Gallus gallus | 50095 | 26 | 21 | 1513 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 18 | 17 | 1254 | |

| Tubulin beta- 5 chain |

TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 12 | 16 | 1028 | |

| Tubulin alpha-5 chain | TBA5 | Gallus gallus | 50715 | 13 | 10 | 877 | |

| Tubulin alpha-4 chain | TBA4 | Gallus gallus | 36483 | 9 | 9 | 465 | |

| ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial | ATP5B | Gallus gallus | 56650 | 10 | 11 | 368 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 8 | 9 | 281 | |

| Tubulin alpha-2 chain | TBA2 | Gallus gallus | 50715 | 7 | 9 | 277 | |

| Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | HSPA8 | Gallus gallus | 71011 | 6 | 8 | 203 | |

| Creatine kinase S-type, mitochondrial | CKMT2 | Gallus gallus | 47510 | 5 | 7 | 188 | |

| Heat shock 70 kDa protein | HSP70 | Gallus gallus | 69936 | 6 | 5 | 172 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 5 | 4 | 126 | |

| Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 | VDAC2 | Meleagris gallopavo | 30162 | 5 | 3 | 115 | |

| Outer dense fibre protein 2 | ODF2 | Gallus gallus | 96467 | 4 | 3 | 106 | |

| Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein eS31 fusion protein | RPS27A | Gallus gallus | 18310 | 4 | 2 | 101 | |

| Polyubiquitin-B | UBB | Gallus gallus | 34348 | 4 | 2 | 101 | |

| Pyruvate kinase | PKM | Gallus gallus | 58434 | 3 | 1 | 98 | |

| Na(+)/H(+) exchange regulatory cofactor NHE-RF1 | NHERF1 | Gallus gallus | 36011 | 2 | 1 | 95 |

| Molecular weight [kDa] |

Identified protein | Gene | Species | Molecular weight (Mascot) [Da] |

No. of matched peptides | Sequence coverage [%] |

Score |

| 107 | Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 39 | 41 | 1389 |

| Cysteine protease ATG4B | ATG4B | Gallus gallus | 45007 | 36 | 38 | 1219 | |

| Fibronectin | FN1 | Gallus gallus | 276669 | 38 | 36 | 1203 | |

| Aminopeptidase Ey | ANPEP | Gallus gallus | 109406 | 28 | 35 | 1145 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 27 | 23 | 1026 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | COL12A1 | Gallus gallus | 341740 | 27 | 22 | 957 | |

| Probable cation-transporting ATPase 13A4 | ATP13A4 | Gallus gallus | 135682 | 27 | 20 | 857 | |

| Ovotransferrin | TF | Gallus gallus | 79551 | 25 | 16 | 819 | |

| Alpha-enolase | ENO1 | Gallus gallus | 47617 | 23 | 21 | 770 | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic | GOT1 | Gallus gallus | 46134 | 12 | 19 | 532 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 8 | 12 | 390 | |

| Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | ASTL | Gallus gallus | 46929 | 10 | 9 | 371 | |

| Clusterin | CLU | Coturnix japonica | 52395 | 4 | 9 | 295 | |

| L-lactate dehydrogenase B | LDHB | Gallus gallus | 36694 | 8 | 4 | 265 | |

| NEL protein | NEL | Gallus gallus | 96096 | 5 | 5 | 202 | |

| Gelsolin | GSN | Gallus gallus | 86120 | 5 | 4 | 136 | |

| Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | HSPA8 | Gallus gallus | 71011 | 6 | 3 | 104 | |

|

52 52 |

Tubulin beta-3 chain | TBB3 | Gallus gallus | 50285 | 60 | 21 | 2146 |

| Tubulin beta-7 chain | TBB7 | Gallus gallus | 50095 | 42 | 16 | 1394 | |

| Tubulin beta-2 chain | TBB2 | Gallus gallus | 50377 | 40 | 16 | 1336 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 35 | 11 | 1133 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 35 | 13 | 1130 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 16 | 17 | 836 | |

| Creatine kinase S-type, mitochondrial | CKMT2 | Gallus gallus | 47510 | 12 | 16 | 573 | |

| Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 | VDAC2 | Meleagris gallopavo | 30162 | 9 | 10 | 493 | |

| Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulphur subunit | SDHB | Gallus gallus | 33374 | 4 | 8 | 278 | |

| Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 6 | 6 | 236 | |

| Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-beta catalytic subunit | PPP1CB | Gallus gallus | 37961 | 3 | 5 | 181 | |

| 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | HSPD1 | Gallus gallus | 61105 | 2 | 4 | 153 | |

| EF-hand domain-containing family member C2 | EFHC2 | Gallus gallus | 87461 | 3 | 3 | 142 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | ACTB | Gallus gallus | 42052 | 2 | 2 | 102 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | ACTG2 | Gallus gallus | 42108 | 2 | 2 | 102 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic type 5 | ACT5 | Gallus gallus | 42151 | 2 | 2 | 102 | |

| 49 | Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 55 | 35 | 2758 |

| Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 42 | 28 | 1592 | |

| Creatine kinase S-type, mitochondrial | CKMT2 | Gallus gallus | 47510 | 29 | 25 | 1333 | |

| Tubulin beta-3 chain | TBB3 | Gallus gallus | 50285 | 36 | 19 | 1005 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 25 | 21 | 693 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 24 | 17 | 631 | |

| Alpha-enolase | ENOA | Gallus gallus | 47617 | 8 | 9 | 481 | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic | GOT1 | Gallus gallus | 46134 | 9 | 6 | 442 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 5 | 4 | 328 | |

| Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 | VDAC2 | Meleagris gallopavo | 30162 | 4 | 5 | 204 | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, mitochondrial | GOT2 | Gallus gallus | 47496 | 7 | 3 | 177 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | ACTB | Gallus gallus | 42052 | 2 | 2 | 110 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | ACTG2 | Gallus gallus | 42108 | 2 | 2 | 110 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic type 5 | ACT5 | Gallus gallus | 42151 | 2 | 2 | 110 | |

|

41 41 |

Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 | VDAC2 | Meleagris gallopavo | 30162 | 16 | 32 | 818 |

| Tubulin beta-3 chain | TBB3 | Gallus gallus | 50285 | 19 | 28 | 630 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 11 | 16 | 626 | |

| Tubulin alpha-4 chain | TBA4 | Gallus gallus | 36483 | 11 | 15 | 606 | |

| Creatine kinase S-type, mitochondrial | CKMT2 | Gallus gallus | 47510 | 8 | 19 | 484 | |

| Tubulin beta-7 chain | TBB7 | Gallus gallus | 50095 | 11 | 14 | 315 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 8 | 12 | 243 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 8 | 10 | 202 | |

| Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein eS31 fusion protein | RPS27A | Gallus gallus | 18310 | 3 | 8 | 143 | |

| Polyubiquitin-B | UBB | Gallus gallus | 34348 | 3 | 8 | 143 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 3 | 7 | 127 | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, mitochondrial | GOT2 | Gallus gallus | 47496 | 3 | 5 | 119 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | ACTB | Gallus gallus | 42052 | 2 | 2 | 112 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | ACTG2 | Gallus gallus | 42108 | 2 | 2 | 112 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic type 5 | ACT5 | Gallus gallus | 42151 | 2 | 2 | 112 | |

| Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 2 | 1 | 93 | |

| 29 | Albumin | ALB | Gallus gallus | 71868 | 72 | 51 | 2853 |

| Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 | VDAC2 | Meleagris gallopavo | 30162 | 21 | 37 | 1052 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 18 | 22 | 1038 | |

| Tubulin beta-3 chain | TBB3 | Gallus gallus | 50285 | 33 | 19 | 848 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 12 | 18 | 722 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 22 | 16 | 523 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 18 | 13 | 503 | |

| Creatine kinase S-type, mitochondrial | CKMT2 | Gallus gallus | 47510 | 7 | 10 | 412 | |

| Ig lambda chain C region | LAC | Gallus gallus | 11525 | 8 | 9 | 330 | |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | APOA1 | Gallus gallus | 30661 | 10 | 8 | 301 | |

| Tubulin alpha-4 chain | TBA4 | Gallus gallus | 36483 | 6 | 14 | 301 | |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase | PGK | Gallus gallus | 45087 | 5 | 7 | 180 | |

| ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial | ATP5B | Gallus gallus | 56650 | 6 | 6 | 171 | |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | PGAM1 | Gallus gallus | 29051 | 3 | 5 | 154 | |

| Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulphur subunit | SDHB | Gallus gallus | 33374 | 4 | 5 | 146 | |

| Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | ASTL | Gallus gallus | 46929 | 3 | 4 | 132 | |

| Tubulin alpha-2 chain | TBA2 | Gallus gallus | 50715 | 4 | 3 | 127 | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Gallus gallus | 35909 | 3 | 2 | 111 | |

| EF-hand domain-containing family member C2 | EFHC2 | Gallus gallus | 87461 | 2 | 1 | 105 | |

| Mitochondria-eating protein | SPATA18 | Gallus gallus | 54997 | 1 | 1 | 99 | |

|

16 16 |

Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 | VDAC2 | Meleagris gallopavo | 30162 | 26 | 35 | 1473 |

| Tubulin beta-7 chain | TBB7 | Gallus gallus | 50095 | 50 | 33 | 1350 | |

| Tubulin beta-5 chain | TBB5 | Gallus gallus | 50395 | 26 | 29 | 1216 | |

| Tubulin beta-4 chain | TBB4 | Gallus gallus | 50844 | 39 | 19 | 1102 | |

| Creatine kinase B-type | CKB | Gallus gallus | 43129 | 16 | 15 | 758 | |

| Tubulin alpha-4 chain | TBA4 | Gallus gallus | 36483 | 15 | 13 | 613 | |

| Acrosin | ACR | Meleagris gallopavo | 38724 | 10 | 12 | 566 | |

| ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial | ATP5B | Gallus gallus | 56650 | 11 | 10 | 478 | |

| Creatine kinase S-type, mitochondrial | CKMT2 | Gallus gallus | 47510 | 10 | 11 | 459 | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Gallus gallus | 35909 | 4 | 10 | 254 | |

| Calmodulin | CALM | Gallus gallus | 16827 | 4 | 8 | 224 | |

| EF-hand domain-containing family member C2 | EFHC2 | Gallus gallus | 87461 | 4 | 8 | 220 | |

| Fatty acid-binding protein, brain | FABP7 | Gallus gallus | 15031 | 4 | 6 | 199 | |

| Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulphur subunit | SDHB | Gallus gallus | 33374 | 2 | 7 | 188 | |

| Outer dense fibre protein 2 | ODF2 | Gallus gallus | 96467 | 4 | 5 | 168 | |

| Mitochondria-eating protein | SPATA18 | Gallus gallus | 54997 | 2 | 5 | 127 | |

| Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein eS31 fusion protein | RPS27A | Gallus gallus | 18310 | 2 | 4 | 124 | |

| Polyubiquitin-B | UBB | Gallus gallus | 34348 | 2 | 3 | 124 | |

| Cilia- and flagella-associated protein 20 | CFAP20 | Gallus gallus | 22891 | 3 | 3 | 122 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | ACTB | Gallus gallus | 42052 | 2 | 2 | 102 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | ACTG2 | Gallus gallus | 42108 | 2 | 2 | 102 | |

| Actin, cytoplasmic type 5 | ACT5 | Gallus gallus | 42151 | 2 | 2 | 102 |

| Molecular Function | #Proteins | Expected | Fold Enrichment | Raw P-Value | FDR |

| Creatine kinase activity | 2 | .01 | >100 | 4.87E-05 | 1.04E-02 |

| Phosphopyruvate hydratase activity | 2 | .01 | >100 | 4.87E-05 | 1.12E-02 |

| Structural constituent of postsynaptic actin cytoskeleton | 2 | .01 | >100 | 4.87E-05 | 9.79E-03 |

| Structural constituent of postsynapse | 2 | .02 | 99.29 | 1.69E-04 | 2.87E-02 |

| Structural molecule activity | 8 | .92 | 8.66 | 3.69E-06 | 1.70E-03 |

| Structural constituent of the cytoskeleton | 7 | .12 | 57.92 | 2.84E-11 | 9.13E-08 |

| GTP binding | 5 | .39 | 12.68 | 4.65E-05 | 1.15E-02 |

| Purine ribonucleoside triphosphate binding | 7 | .53 | 13.22 | 9.67E-07 | 1.04E-03 |

| Nucleoside phosphate binding | 7 | .82 | 8.57 | 1.68E-05 | 4.92E-03 |

| Anion binding | 9 | 1.12 | 8.04 | 1.59E-06 | 1.28E-03 |

| Ion binding | 13 | 2.13 | 6.10 | 1.44E-07 | 2.31E-04 |

| Guanyl ribonucleotide binding | 5 | .41 | 12.07 | 5.90E-05 | 1.12E-02 |

| Purine ribonucleotide binding | 7 | .63 | 11.11 | 3.08E-06 | 1.65E-03 |

| Purine nucleotide binding | 7 | .66 | 10.67 | 4.02E-06 | 1.44E-03 |

| Nucleotide binding | 7 | .82 | 8.57 | 1.68E-05 | 5.41E-03 |

| Small molecule binding | 9 | 1.13 | 7.96 | 1.73E-06 | 1.11E-03 |

| Ribonucleotide binding | 7 | .65 | 10.76 | 3.80E-06 | 1.53E-03 |

| Carbohydrate derivative binding | 7 | .92 | 7.60 | 3.61E-05 | 9.68E-03 |

| Guanyl nucleotide binding | 5 | .41 | 12.07 | 5.90E-05 | 1.05E-02 |

| Molecular Function | #Proteins | Expected | Fold Enrichment | Raw P-Value | FDR |

| Creatine kinase activity | 2 | .01 | >100 | 5.54E-05 | 3.57E-02 |

| Phosphopyruvate hydratase activity | 2 | .01 | >100 | 5.72E-05 | 3.68E-02 |

| L-lactate dehydrogenase activity | 2 | .02 | >100 | 9.22E-05 | 4.24E-02 |

| Unfolded protein binding | 4 | .21 | 18.89 | 6.01E-05 | 3.22E-02 |

| Anion binding | 9 | 1.19 | 7.54 | 2.78E-06 | 2.23E-03 |

| Ion binding | 13 | 2.27 | 5.72 | 3.20E-07 | 1.03E-03 |

| Molecular Function | #Proteins | Expected | Fold Enrichment | Raw P-Value | FDR |

| Creatine kinase activity | 2 | .01 | >100 | 2.15E-05 | 6.28E-03 |

| Phosphopyruvate hydratase activity | 2 | .01 | >100 | 2.15E-05 | 6.91E-03 |

| Structural molecule activity | 6 | .62 | 9.74 | 3.14E-05 | 7.76E-03 |

| Structural constituent of the cytoskeleton | 5 | .08 | 62.06 | 1.62E-08 | 5.21E-05 |

| GTP binding | 4 | .26 | 15.22 | 1.36E-04 | 2.91E-02 |

| Purine ribonucleoside triphosphate binding | 6 | .35 | 17.00 | 1.30E-06 | 2.09E-03 |

| Nucleoside phosphate binding | 6 | .54 | 11.01 | 1.58E-05 | 5.63E-03 |

| Anion binding | 7 | .75 | 9.38 | 8.17E-06 | 4.38E-03 |

| Ion binding | 8 | 1.42 | 5.63 | 6.87E-05 | 1.58E-02 |

| Guanyl ribonucleotide binding | 4 | .28 | 14.48 | 1.64E-04 | 3.30E-02 |

| Purine ribonucleotide binding | 6 | .42 | 14.28 | 3.57E-06 | 3.83E-03 |

| Purine nucleotide binding | 6 | .44 | 13.72 | 4.50E-06 | 2.90E-03 |

| Nucleotide binding | 6 | .54 | 11.01 | 1.58E-05 | 6.33E-03 |

| Small molecule binding | 7 | .75 | 9.28 | 8.73E-06 | 4.01E-03 |

| Ribonucleotide binding | 6 | .43 | 13.84 | 4.28E-06 | 3.44E-03 |

| Carbohydrate derivative binding | 6 | .61 | 9.77 | 3.08E-05 | 8.27E-03 |

| Guanyl nucleotide binding | 4 | .28 | 14.48 | 1.64E-04 | 3.11E-02 |

| Molecular Function | #Proteins | Expected | Fold Enrichment | Raw P-Value | FDR |

| L-aspartate:2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase activity | 2 | .01 | >100 | 1.13E-05 | 1.21E-02 |

| Creatine kinase activity | 2 | .01 | >100 | 2.26E-05 | 1.45E-02 |

| Phosphopyruvate hydratase activity | 2 | .01 | >100 | 2.26E-05 | 1.82E-02 |

| Structural constituent of the cytoskeleton | 3 | .08 | 36.33 | 7.68E-05 | 4.12E-02 |

| Anion binding | 7 | .76 | 9.15 | 9.70E-06 | 3.12E-02 |

| Ion binding | 9 | 1.46 | 6.18 | 1.09E-05 | 1.75E-02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).