1. Introduction

The periodic outbreaks of highly pathogenic and rapidly spreading coronaviruses (CoV) remain a major concern for global health, especially since their zoonotic origin makes emergence of previously unknown CoVs likely. This highlights the need for a better understanding of the immune-evasive nature of these CoVs, to guide the development of new treatment options in the future. Since efficient evasion of the innate immune response seems to be a hallmark of CoV infection [

1,

2] therapeutic targeting of the underlying molecular mechanism could lead to potent antiviral drugs.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, novel virulence factors for SARS-CoV-2 came into focus. One of them was the conserved MacroD-like macrodomain (Mac1), which is part of the non-structural protein 3 (nsp3) encoded by SARS-CoV-2 open reading frame 1 (ORF1). [

3,

4]. The large nsp3 is a component of pore complexes within the membrane of double membrane vesicles (DMVs), which are formed after viral infection from the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) and serve as viral replication organelles [

5,

6]. Furthermore, nsp3 has been reported to suppress the antiviral interferon (IFN) response triggered by viral replication intermediates upon host recognition [

4,

6]. Although the exact mechanism remains unclear, there is increasing evidence that Mac1 can directly interfere with cellular IFN signaling, presumably by reverting poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP)-mediated ADP-ribosylation by the host, which has been reported for SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses (e.g. SARS-CoV and MHV) in vivo [

3,

7,

8]. Thus, pharmacological targeting of viral macrodomains has received increasing attention in recent years.

Although there have already been some efforts to identify potential interactors of the viral macrodomain of SARS-CoV-2, these studies mostly used either (virus free) ectopic expression systems, (cell-free) biochemical pulldowns, enzyme assays or in silico models [

4,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, only few potential interactors have been postulated and they lack verification in physiologically more relevant test systems. Also, most of these studies are limited the lack of (commercially) available detection reagents for Mac1/nsp3, i.e. polyclonal antibodies or nanobodies. Thus, there are still no powerful detection tools for robust Mac1 detection available.

Reverse genetics approaches offer excellent tools for dissecting viral protein function through the generation of genetically modified viruses that can be studied under physiologically relevant infection conditions [

15,

16]. However, inserting epitope tags into the coronavirus replicase complex, particularly within nsp3, is technically challenging due to the large genome size, complex secondary structures, and the critical functional requirements of replicase components for CoV viability [

17].

Here we report a reverse genetic approach for epitope-tagging of SARS-CoV-2 Mac1 by specific and highly affine nanobodies, providing a versatile tool to study coronavirus pathogenesis and identify therapeutic targets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Maintenance

Vero E6 cells (ATCC® CRL-1586), CaLu-3 cells (Cytion, 305032), A549-A/T cells [

18] and HEK-293T-Ace-2-TMPRSS2 (BEI resources, NR-55293) were maintained under standard conditions in DMEM (Gibco, Life Technologies), supplemented with 10 % (Vero E6 and CaLu-3), 5% (A549-A/T) or 3% (HEK-293T-Ace-2-TMPRSS2 cells) foetal calf serum (Biochrom), 100 U/l penicillin, 100 µg/l streptomycin (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), 1 mM non-essential amino acids (Gibco, Life Technologies) and L-Glutamin. 2mM (Pan-Biotech). For A549-A/T cells, medium was additionally supplemented with Blasticidin (10 µg/ml, Invivogen) and Puromycin (0.5 µg/ml, Invitrogen).

2.2. Generation and Rescue of Recombinant SARS-CoV-2

The recombinant SARS-CoV-2 without replicase modifications (rWT) was generated based on a cDNA clone [

19] as previously described [

20]. Both the recombinant SARS-CoV-2 with ALFA-tag in nsp3 (rALFA) and the variant with deleted Mac1 in nsp3 (rΔMac1) were generated based on the cDNA clone using the CLEVER method [

21]. All PCRs for generating the required cDNA fragments CLEVER 1-5 and linker (

Table 1) were generated using a proofreading polymerase (Q5, NEB). Primers “CLEVER MacNalfa fwd (5´- agagatggaacttacaccagttgttcagactattccatctagattagaagaagaattaagaagaagattaactgaaccagaagtgaatagttttagtggttatttaaaacttactgacaatgta-3´) and CLEVER MacNalfa rev(5´- ctattcacttctggttcagttaatcttcttcttaattcttcttctaatctagatggaatagtctgaacaactggtgtaagttccatctct -3´)” were used for insertion of the ALFA-tag immediately upstream of Mac1 in nsp3 (fragments CLEVER 1a ALFA and CLEVER 1b ALFA), and primers “CLEVER del Mac fwd (5´- aggttcaacctcaattagagatggaacttacaccagttgttcagactattagtgaaaagcaagttgaacaaaagatcgctgagattcctaaagaggaagttaagccatttataactga-3´) and “CLEVER del Mac rev (5´-aacttcctctttaggaatctcagcgatcttttgttcaacttgcttttcactaatagtctgaacaactggtgtaagttccatctctaattgaggttgaacctcaacaattgt -3´)” were used for the depletion of Mac1 (fragments CLEVER 1a and CLEVER 1b). Details on the CLEVER primers can be found in

Table 1.

For virus rescue, the purified and sequenced cDNA fragments were transfected in equimolar ratios together with a linker fragment in HEK-293-Ace-2-TMPRSS2 cells as described [

20]. Briefly, DNA was diluted in reduced-serum medium (Opti-MEM, Gibco) and combined with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer for transfection. Fresh medium was added 4-6 hours after transfection. Cells were incubated for 2-4 days before a transfer to Vero E6 cells (passage 0 of the recombinant SARS-CoV-2) was performed. To verify viral growth, cultures were monitored for CPE every other day and RT-qPCR [

22] and/or luciferase reporter assay [

19] were performed. Virus stocks were produced in Vero E6 cells (T75 flasks).

For virus quantification, plaque assay was performed by infecting Vero E6 cells seeded to either 6-well or 24-well plates (both Sarstedt) with serial viral dilutions and a 1.2% Avicel overlay as described [

23]. Sequence integrity of recombinant viruses was verified by whole genome amplicon sequencing (DeepChek Assay whole genome SARS-CoV-2 genotyping, ABL) on an Illumina platform (iSeq 100, Illumina).

2.3. SARS-CoV-2 Replication Kinetics and Immunofluorescence Imaging

For replication kinetics, cells were seeded to 96-well plates (TPP) and infected with the recombinant viruses at indicated MOIs. After 1h adsorption at 37°C, fresh medium was added cells were incubated at 37°C and used for further analysis by luciferase assay or titration by plaque assay at indicated time points.

For immunofluorescence analysis, cells were grown on cover slips to 80% confluency and infected with recombinant viruses at MOI = 1. After 20h of incubation at 37° C, virus inactivation and fixation of cells was performed using formaline (4% in PBS). Fixated cells were washed three times with 50 mM ammonium chloride (NH

4Cl) and incubated for 5 min in fresh NH

4Cl solution at room temperature (RT) to mask free aldehyde groups. Cells were then washed again in PBS (Thermo Fisher) prior to permeabilization in PBS containing 0.1% saponin (Fluka, PBS-sap) for 10 min at RT. Details on primary detection reagents and secondary antibodies as well as their dilutions are listed in

Table 2 and

Table 3. First, cells were blocked in PBS-sap supplemented with 3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma Aldrich. PBS-sap-BSA) for 30 min at RT. After blocking, cells were incubated with primary antibody diluted in PBS-sap-BSA solution at 4 °C for 1 h in the dark. Then, cells were washed three times with PBS-sap-BSA prior to incubation with secondary antibodies solution at 4 °C for 1 h in the dark. After three washes with PBS-sap-BSA and once with PBS, cell nuclei were stained for 20 min at RT with DAPI (invitrogen) diluted in PBS. After washing twice with PBS and ultra pure H

2O, coverslips (Marienfeld) were mounted cell-side down onto a glass slide (Epredia) with mounting medium (invitrogen) and allowed to solidify for 1 h in the dark. Slides were stored at 4 °C in the dark until imaging.

A super resolution spinning-disk microscope (Visitron) equipped with a CSU-W1 SoRa Optic (2.8x, Yokogawa) and a 100x or 40x oil immersion objective was used for visualization. The technical setup included one-fold binning, gain 2 and output 50%. Laser settings were: 405 nm at 250 ms exposure time and 50% laser power, 488 nm at 400 ms and 30% power, 561 nm at 400 ms and 30% power and 647 nm at 400 ms and 30% power. Images were captured using a sCMOS camera (Orca-Flash 4.0, C13440-20CU Hamamatsu) and acquired with VisiView software by Visitron. Background correction and further image analysis was performed in FIJI (ImageJ v1.53f51).

2.4. Statistics

Replication kinetics assay data were log transformed and statistically tested with GraphPad Prism version 9.2.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA). A significance niveau (α) of 5% was applied.

3. Results

3.1. Generation and Characterization of a Recombinant ALFA-Tagged SARS-CoV-2

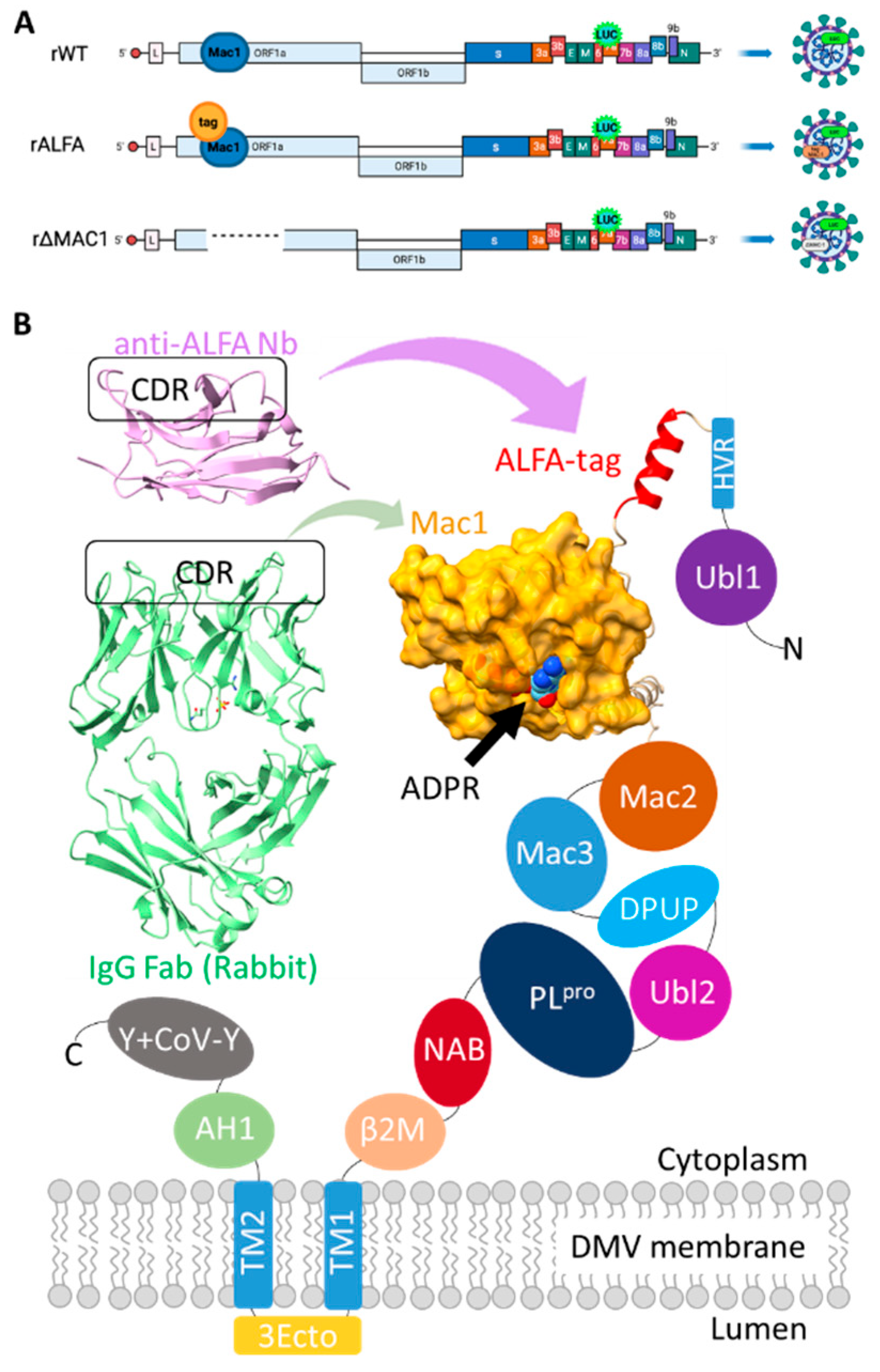

Using reverse genetics, we successfully generated recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants: a virus without replicase modifications (rWT) [

20], a variant lacking the Mac1 domain (rΔMac1), and a variant encoding an SRLEEELRRRLTE (ALFA)-tag upstream of Mac1 within nsp3 (rALFA), as illustrated in the schematic overview (

Figure 1a). The location of the tag allows for indirect (epitope) tagging of Mac1 (

Figure 1b).

3.1.2. Growth Characteristics of Recombinant SARS-CoV-2

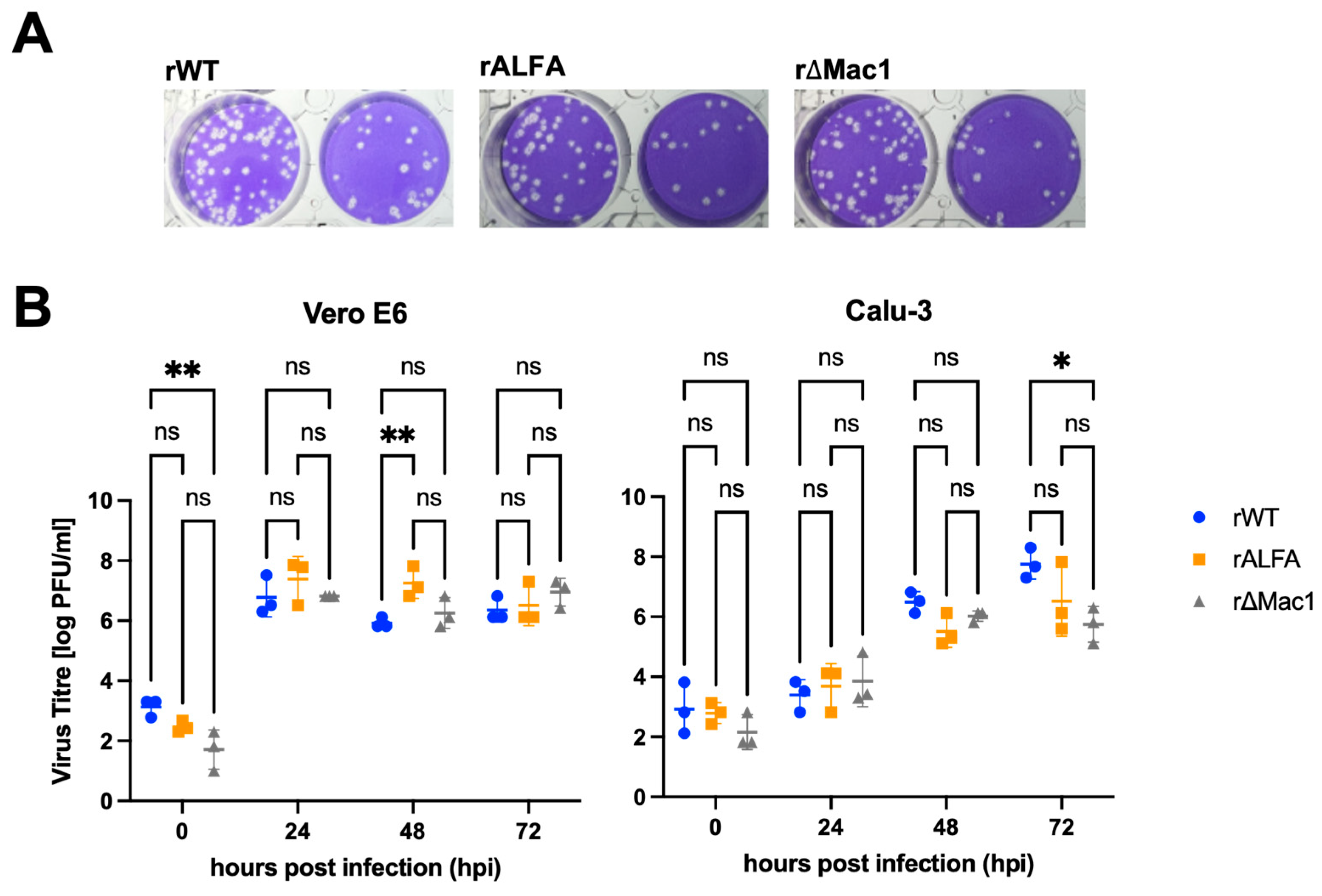

The newly generated recombinant variants rALFA and rΔMac1 were successfully rescued and proved replication competent as the previously generated rWT [

20]. On Vero E6 cells, we observed a pronounced cytopathic effect (CPE) for all viruses, thus sustained lytic infection for rALFA is evident with similar plaque morphology compared to rWT and rΔMac1 (

Figure 2A).

Replication kinetics on Vero E6 cells revealed comparable growth with high titres reached by all three variants. Notably, the tagged variant rALFA demonstrated robust replication capacity with mean peak titres (7.55 × 10

6 [range 1.33 × 10

6-2.00 × 10

7] PFU/ml) comparable to those of rWT (3.11 [range 1.33 × 10

6-6.67 × 10

6] PFU/ml) and rΔMac1 (1.20 × 10

7 [range 2.67 × 10

6-2.00 × 10

7] PFU/ml) (

Figure 2B). Interestingly, we observed an advantage for rALFA compared to rWT on Vero E6 cells 48 hpi (mean titres rWT 8.88 × 10

5 [range 6.67 × 10

5-1.33 × 10

6] PFU/ml, rALFA 2.89 × 10

7 [range 6.67 × 10

6-6.67 × 10

7] PFU/ml) (

Figure 2B).

Next, we assessed replication on Calu-3 cells, which, given their largely intact immune system, represent a more complex and physiologically relevant model. Again, at 72 hpi, rWT and rALFA reached high titres (mean 8.89 × 10

7 [range 2.00× 10

7 -2.00 × 10

8] PFU/ml for rWT and 2.28 × 10

7 PFU/ml [range 4.00× 10

5 -6.67 × 10

7] for rALFA), indicating that the ALFA tag does not impair viral replication. In contrast, rΔMac1 titres were strongly reduced (9.33 × 10

5 [range 1.33× 10

5 -2.00× 10

6] PFU/ml) on the human epithelial cells. Luciferase reporter assays demonstrated comparable reporter signals for all three recombinant viruses on both cell lines, with rALFA and rΔMac1 infection inducing reporter translation more efficiently as rWT on Vero cells (

Figure S1). These findings demonstrate that while rΔMac1 production of infectious progeny is restricted in Calu-3 cells, the inserted ALFA-tag within nsp3 does not compromise viral fitness, indicating that the Mac1 activity is not affected.

3.2. IF studies of A549 Cells Infected with Recombinant SARS-CoV-2

3.2.1. Specific Imaging of Mac1 in rWT-Infected Cells Using Directly Targeted Antibodies

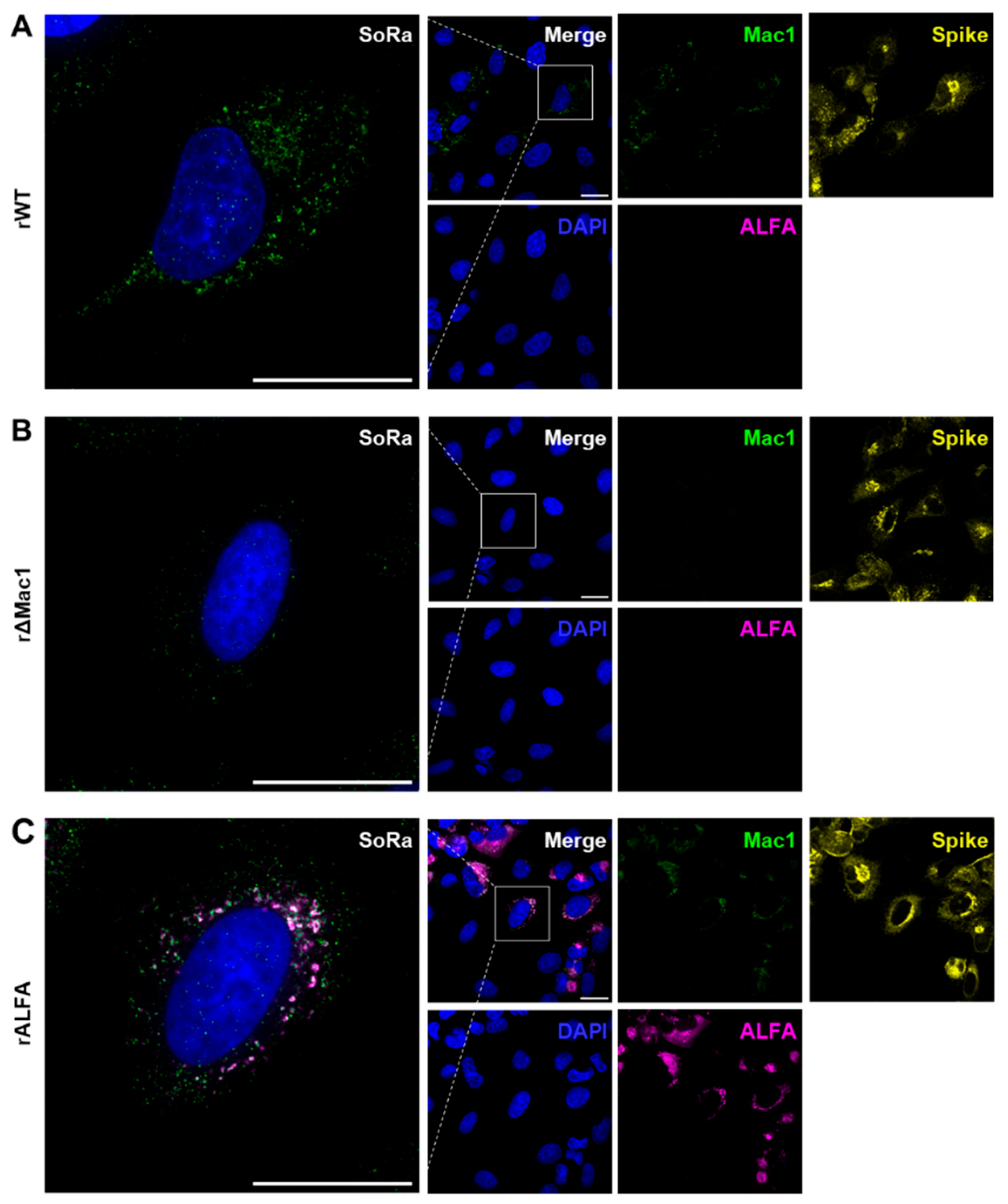

Figure 3 shows IF data of A549 cells, which were infected with the recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants. Of note, all 3 viruses, i.e. rWT, rΔMac1 and rALFA were able to infect A549 cells at the chosen MOI resulting in sufficiently high infection rate for robust imaging (>50% Spike positive).

To test for different immuno-staining strategies for Mac1, we first chose the classical approach using a directly targeted Mac1 antibody. Indeed, Mac1 staining was successful in A549 cells infected with rWT (

Figure 3A), while exhibiting only minimal background in the rΔMac1 control (

Figure 3B), thereby showing antibody specificity and viability of direct Mac1 imaging in SARS-CoV-2 infected cells.

3.2.2. N-Terminal ALFA-Tagging Enables Super Resolved Visualization of Mac1 in rALFA-Infected Cells

Next, we applied the non-canonical, indirect approach for Mac1 targeting. As proof of concept, A549 cells infected with rALFA were co-stained with both anti-ALFA nanobody and anti-Mac1 antibody (control) (

Figure 3C). At super resolution (SoRa mode), anti-Mac1 staining overlapped with the ALFA signals that were consistently absent for the other viruses (rWT and rΔMac1) (

Figure 3C), which was also the case for anti-ALFA co-staining with an anti-nsp3 antibody (

Figure S2). Interestingly, ALFA staining exhibited a halo shape comprising Mac1/nsp3 signals, which appeared as individual foci, providing insights into DMV membrane structure (

Figure 3C and

Figure S2).

Taken together, the IF data demonstrate i) specific and robust imaging of Mac1 by (non-canonical) ALFA-tagging, allowing for ii) super resolved co-localization studies at the Mac1/DMV interface.

4. Discussion

Despite the recognized importance of the nsp3 encoded macrodomain Mac1 as a crucial virulence factor for SARS-CoV-2 [

25,

26], the physiological substrates and interaction partners of this domain remain largely unknown. The limited availability of suitable tools for comprehensive interactome analysis has hampered progress in understanding Mac1 function and, consequently, the development of targeted therapeutics.

To address this gap, we present a novel strategy engineering a fully infectious recombinant ALFA tagged SARS-CoV-2, which enables high-resolution intracellular imaging of ALFA-tagged Mac1 in infected cells while providing a robust platform for antiviral drug discovery. Importantly, this approach is not restricted to a model system and could also be used for in vivo studies.

In comparative replication kinetics the tagged virus reveals retained biological properties, supporting its suitability for therapeutic applications. First, the ALFA-tag does not significantly impair viral growth characteristics, ensuring that drug efficacy studies will reflect authentic infection. Second, peak viral titres of the tagged virus remained within the same order of magnitude compared to the recombinant wild-type SARS-CoV-2 without nsp3 modifications, confirming that potential therapeutic compounds can be evaluated against a virus system that maintains the fundamental replication machinery. Third, the contrasting phenotype observed with our virus lacking the macrodomain, particularly the reduced replication efficiency in interferon competent cells that is in line with previously reported findings [

27], validates Mac1 as a viable therapeutic target, while suggesting that our tagging approach preserves the biological relevance essential for drug screening applications.

Our approach can provide a significant advancement for antiviral drug development, offering advantages over previous approaches for studying nsp3 function and identifying therapeutic targets. While earlier investigations have employed affinity-tagged nsp3 [

6,

9,

10], these studies relied primarily on overexpression systems that may not accurately reflect the physiological context of viral infection or provide suitable platforms for compound screening. While it has been shown that the CoV replicase may tolerate reporter genes as fusion proteins or as replacements for dispensable proteins [

28], our work presents the first recombinant SARS-CoV-2 with internally epitope-labeled full-length nsp3 that can be directly employed in drug discovery workflows.

Several technical innovations distinguish our approach and enhance its utility for therapeutic development. First, we utilized ALFA-tags, which offer substantial advantages for drug discovery applications over conventional affinity epitopes such as HA and FLAG tags that have been used for nsp3 labeling [

6] [

9,

10] These advantages include higher specificity for interaction partner identification, superior biological and chemical stability under screening conditions, and reduced background signal that improves assay reliability [

29]. Second, we strategically introduced the affinity tag in close proximity to the Mac1 domain within nsp3, enabling direct monitoring of therapeutic compound effects on Mac1 function and interactions while maintaining full viral replication competence for phenotypic screening.

The enhanced imaging and interaction analysis capabilities afforded by our system open new avenues for innovative therapeutic discovery. The high-resolution visualization of Mac1/nsp3 dynamics could provide a powerful tool for screening compounds that disrupt critical virus-host interactions or alter Mac1 subcellular localization. These capabilities, combined with the preserved viral fitness, establish rALFA as an invaluable resource for developing next-generation antivirals targeting the viral macrodomain or nsp3.

Comparative analysis across different experimental conditions confirmed the system's suitability for drug discovery applications, as no substantial alterations in Mac1/nsp3 staining patterns were observed between rALFA and rWT-infected cells. This preservation of subcellular localization will help therapeutic screening that reflect genuine nsp3/Mac1 biology, while providing high sensitivity for detecting compound-induced changes in protein distribution or interaction patterns.

5. Limitations

The Mac1 antibody used for validation of ALFA-Mac1 imaging exhibited minimal, yet readable cross-reactivity as seen in rΔMac1 infected cells. However, the cumulative evidence for the ALFA nanobody co-staining with either nsp3 or Mac1 antibodies suggests that signal overlaps were in good agreement, mitigating specificity concerns for the latter.

6. Conclusions

We report on a recombinant SARS-CoV-2 employing an internally ALFA-tagged nsp3 with full infectious capability and no evidence of compromised replicase function due to tagging. The preserved viral fitness establishes rALFA as a powerful platform for functional nsp3 studies that can be directly exploited for drug candidate testing. In particular, the improved imaging and interaction analysis capabilities can provide new impulses for therapeutic target discovery and the development of novel antiviral strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and R.F.; methodology, L.U, N.P, M.L., P.E., R.v.P and J.B.; formal analysis, L.U., S.P.; investigation, L.U. N.P., J.B.; data curation, S.P., M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.U., M.S., R.F., S.P.; writing—review and editing, M.S., R.F., S.P.; visualization, L.U., M.S., S.P.; supervision, R.F., M.S., S.P.; project administration, S.P., R.F.; funding acquisition, S.P., R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (grant number 335447717; CRC1328, project A18 to RF and SP, and RTG 2771, project P9). M.L. and S.P. are associated members of the CRC1648.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The genetic engineering work was approved by the authorities (Hamburg Ministry of the Environment, Climate, Energy and Agriculture, BUKEA) (AZ I14-29/2022).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexander Carsten (UKE) for the kind gift of the anti-ALFA nanobody. We thank Krzysztof Pyrc for providing the A549-A/T cells.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| 3Ecto |

Nsp3 ectodomain |

| ADPR |

ADP-ribose |

| AH1 |

Amphipathic helix 1 |

| ALFA |

SRLEEELRRRLTE peptide |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| BSA |

Bovine serum albumin |

| CDR |

Complementary determining regions |

| CoV |

Coronavirus |

| COVID19 |

Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CPE |

Cytophatic effect |

| DAPI |

4′,6-Diamidin-2-phenylindol |

| DMV |

Double membrane vesicle |

| DPUP |

Domain Preceding Ubl2 and PL2pro

|

| ERGIC |

ER-Golgi intermediate compartment |

| FLAG |

DYKDDDDK peptide |

| HA |

hemagglutinin |

| hpi |

Hours post infection |

| HVR |

Hyper variable region |

| IF |

Immuno-fluorescence |

| IFN |

interferon |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| Mac |

Macrodomain |

| MHV |

Murine hepatitis virus |

| NAB |

Nucleic acid binding domain |

| Nb |

Nanobody |

| NH4Cl |

Ammonium chloride |

| nsp3 |

Non-structural protein 3 |

| ORF |

Open reading frame |

| PARP |

Poly-ADPR-polymerase |

| PBS |

Phosphate buffered saline |

| PDB |

Protein data bank |

| PFU |

Plaque forming units |

| PLPro

|

Papain like protease |

| RLU |

Relative light unit |

| RT |

Room temperature |

| sap |

saponin |

| SARS |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| β2M |

β-coronavirus-specific marker |

| TM |

Transmembrane domain |

| Ubl |

Ubiquitin-like domain |

References

- Lamers, M.M.; Haagmans, B.L. SARS-CoV-2 Pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkoff, J.M.; tenOever, B. Innate Immune Evasion Strategies of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Jankevicius, G.; Ahel, I.; Perlman, S. Viral Macrodomains: Unique Mediators of Viral Replication and Pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rack, J.G.M.; Zorzini, V.; Zhu, Z.; Schuller, M.; Ahel, D.; Ahel, I. Viral Macrodomains: A Structural and Evolutionary Assessment of the Pharmacological Potential. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, G.; Limpens, R.W.A.L.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; Laugks, U.; Zheng, S.; de Jong, A.W.M.; Koning, R.I.; Agard, D.A.; Grünewald, K.; Koster, A.J.; et al. A Molecular Pore Spans the Double Membrane of the Coronavirus Replication Organelle. Science 2020, 369, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, L.; Zhao, X.; Makroczyova, J.; Wachsmuth-Melm, M.; Prasad, V.; Hensel, Z.; Bartenschlager, R.; Chlanda, P. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp3 and Nsp4 Are Minimal Constituents of a Pore Spanning Replication Organelle. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, T.Y.; Suryawanshi, R.K.; Chen, I.P.; Correy, G.J.; McCavitt-Malvido, M.; O’Leary, P.C.; Jogalekar, M.P.; Diolaiti, M.E.; Kimmerly, G.R.; Tsou, C.-L.; et al. A Single Inactivating Amino Acid Change in the SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 Mac1 Domain Attenuates Viral Replication in Vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, A.R.; Athmer, J.; Channappanavar, R.; Phillips, J.M.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Perlman, S. The Nsp3 Macrodomain Promotes Virulence in Mice with Coronavirus-Induced Encephalitis. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 1523–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasy, K.M.; Davies, J.P.; Plate, L. Comparative Host Interactomes of the SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Protein 3 and Human Coronavirus Homologs. Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP 2021, 20, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Lopez, V.; Plate, L. Comparative Interactome Profiling of Nonstructural Protein 3 Across SARS-CoV-2 Variants Emerged During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses 2025, 17, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, L.C.; Tomasin, R.; Matos, I.A.; Manucci, A.C.; Sowa, S.T.; Dale, K.; Caldecott, K.W.; Lehtiö, L.; Schechtman, D.; Meotti, F.C.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 Nsp3 Macrodomain Reverses PARP9/DTX3L-Dependent ADP-Ribosylation Induced by Interferon Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhammad, Y.M.O.; Kashipathy, M.M.; Roy, A.; Gagné, J.-P.; McDonald, P.; Gao, P.; Nonfoux, L.; Battaile, K.P.; Johnson, D.K.; Holmstrom, E.D.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 Conserved Macrodomain Is a Mono-ADP-Ribosylhydrolase. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e01969–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalič, F.; Benz, C.; Kassa, E.; Lindqvist, R.; Simonetti, L.; Inturi, R.; Aronsson, H.; Andersson, E.; Chi, C.N.; Davey, N.E.; et al. Identification of Motif-Based Interactions between SARS-CoV-2 Protein Domains and Human Peptide Ligands Pinpoint Antiviral Targets. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đukić, N.; Strømland, Ø.; Elsborg, J.D.; Munnur, D.; Zhu, K.; Schuller, M.; Chatrin, C.; Kar, P.; Duma, L.; Suyari, O.; et al. PARP14 Is a PARP with Both ADP-Ribosyl Transferase and Hydrolase Activities. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahnøe, U.; Pham, L.V.; Fernandez-Antunez, C.; Costa, R.; Rivera-Rangel, L.R.; Galli, A.; Feng, S.; Mikkelsen, L.S.; Gottwein, J.M.; Scheel, T.K.H.; et al. Versatile SARS-CoV-2 Reverse-Genetics Systems for the Study of Antiviral Resistance and Replication. Viruses 2022, 14, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazán, F.; Sola, I.; Zuñiga, S.; Marquez-Jurado, S.; Morales, L.; Becares, M.; Enjuanes, L. Coronavirus Reverse Genetic Systems: Infectious Clones and Replicons. Virus Res. 2014, 189, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, J.; Kusov, Y.; Hilgenfeld, R. Nsp3 of Coronaviruses: Structures and Functions of a Large Multi-Domain Protein. Antiviral Res. 2018, 149, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, T.L.; Nocke, M.K.; Heinen, N.; Burkard, T.L.; Brüggemann, Y.; Westhoven, S.; Trüeb, B.; Ebert, N.; Thomann, L.; Lubieniecki, K.P.; et al. Mycophenolic Acid Treatment Drives the Emergence of Novel SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2025, 122, e2500276122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihn, S.J.; Merits, A.; Bakshi, S.; Turnbull, M.L.; Wickenhagen, A.; Alexander, A.J.T.; Baillie, C.; Brennan, B.; Brown, F.; Brunker, K.; et al. A Plasmid DNA-Launched SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics System and Coronavirus Toolkit for COVID-19 Research. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliegert, R.; Sandmann, M.; Tajdar, S.; Sander, S.; Carrillo, D.; Ganter, B.; Ocenas, M.; Etzold, S.; Pekarek, N.; Berger, J.; et al. Targeting a Viral Macrodomain: Design, Structure-Based Optimization and Antiviral Evaluation of Nanomolar Inhibitors for Mac1 of SARS-CoV-2 2025.

- Kipfer, E.T.; Hauser, D.; Lett, M.J.; Otte, F.; Urda, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lang, C.M.R.; Chami, M.; Mittelholzer, C.; Klimkait, T. Rapid Cloning-Free Mutagenesis of New SARS-CoV-2 Variants Using a Novel Reverse Genetics Platform. eLife 2023, 12, RP89035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.T.; Nörz, D.; Grunwald, M.; Giersch, K.; Pfefferle, S.; Fischer, N.; Aepfelbacher, M.; Rohde, H.; Lütgehetmann, M. Analytical and Clinical Validation of a Novel, Laboratory-Developed, Modular Multiplex-PCR Panel for Fully Automated High-Throughput Detection of 16 Respiratory Viruses. J. Clin. Virol. Off. Publ. Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 2024, 173, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, P.; Drosten, C.; Müller, M.A. Plaque Assay for Human Coronavirus NL63 Using Human Colon Carcinoma Cells. Virol. J. 2008, 5, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soh, T.K.; Pfefferle, S.; Wurr, S.; Possel, R. von; Oestereich, L.; Rieger, T.; Uetrecht, C.; Rosenthal, M.; Bosse, J.B. A Validated Protocol to UV-Inactivate SARS-CoV-2 and Herpesvirus-Infected Cells. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0274065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, A.R.; Channappanavar, R.; Jankevicius, G.; Fett, C.; Zhao, J.; Athmer, J.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Ahel, I.; Perlman, S. The Conserved Coronavirus Macrodomain Promotes Virulence and Suppresses the Innate Immune Response during Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection. mBio 2016, 7, e01721–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, T.Y.; Suryawanshi, R.K.; Chen, I.P.; Correy, G.J.; McCavitt-Malvido, M.; O’Leary, P.C.; Jogalekar, M.P.; Diolaiti, M.E.; Kimmerly, G.R.; Tsou, C.-L.; et al. A Single Inactivating Amino Acid Change in the SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 Mac1 Domain Attenuates Viral Replication in Vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhammad, Y.M.O.; Fehr, A.R. The Viral Macrodomain Counters Host Antiviral ADP-Ribosylation. Viruses 2020, 12, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.C.; Graham, R.L.; Lu, X.; Peek, C.T.; Denison, M.R. Coronavirus Replicase-Reporter Fusions Provide Quantitative Analysis of Replication and Replication Complex Formation. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 5319–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götzke, H.; Kilisch, M.; Martínez-Carranza, M.; Sograte-Idrissi, S.; Rajavel, A.; Schlichthaerle, T.; Engels, N.; Jungmann, R.; Stenmark, P.; Opazo, F.; et al. The ALFA-Tag Is a Highly Versatile Tool for Nanobody-Based Bioscience Applications. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.14/09/2025 18:31:00 |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).