Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells

2.2. Expression Constructs

2.3. Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

2.5. Production of lentiviruses Encoding Single SARS-CoV-2 Viral Proteins

2.6. Transduction of HUVEC and IFN Stimulation

2.7. RT-qPCR

2.8. Figure Generation

3. Results

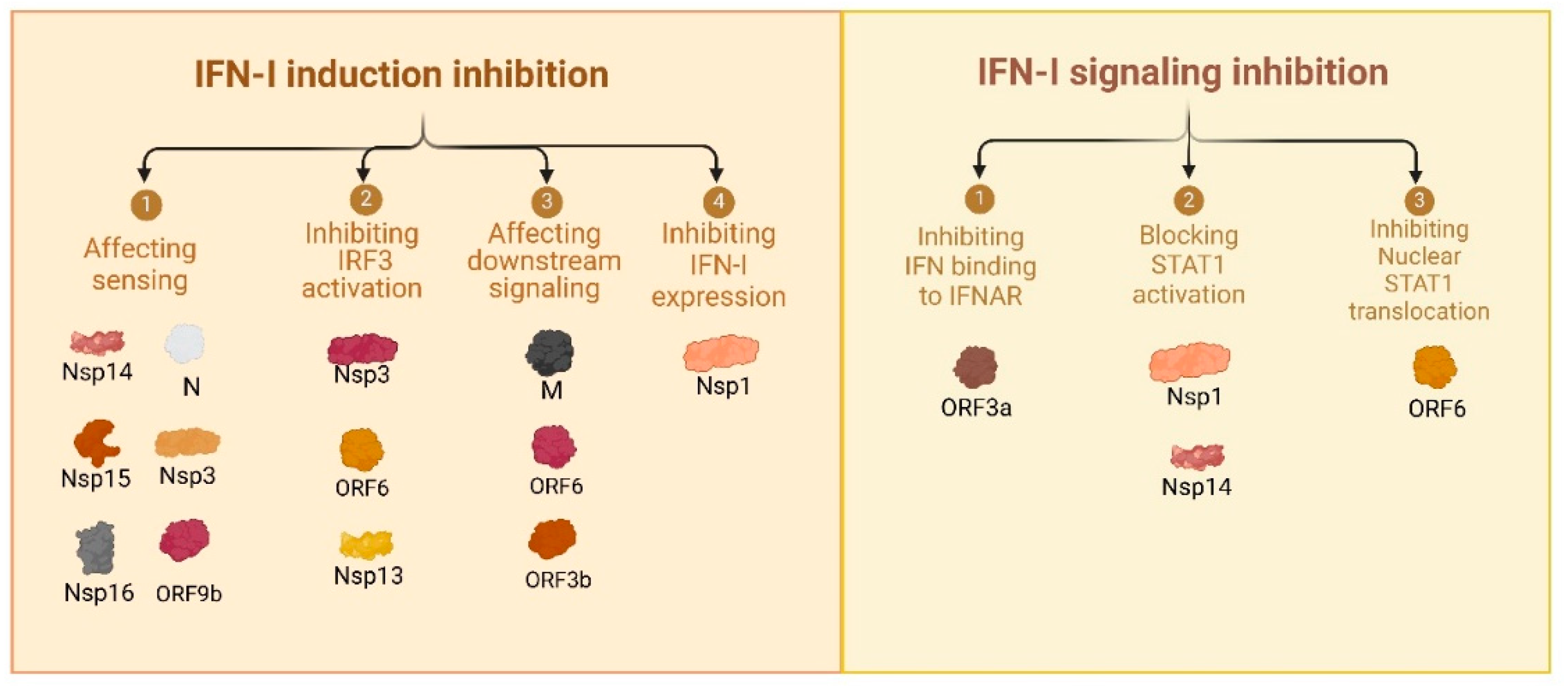

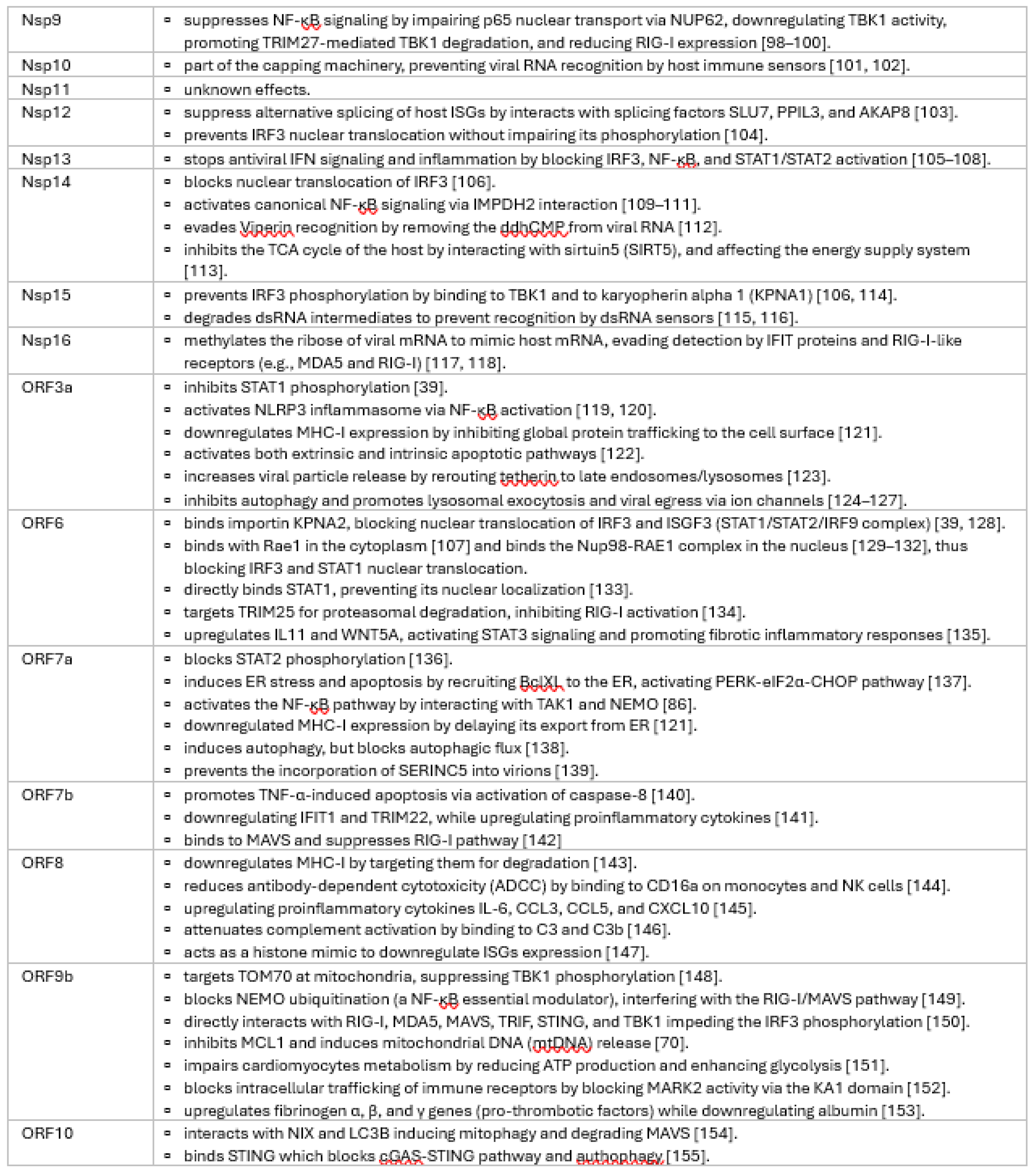

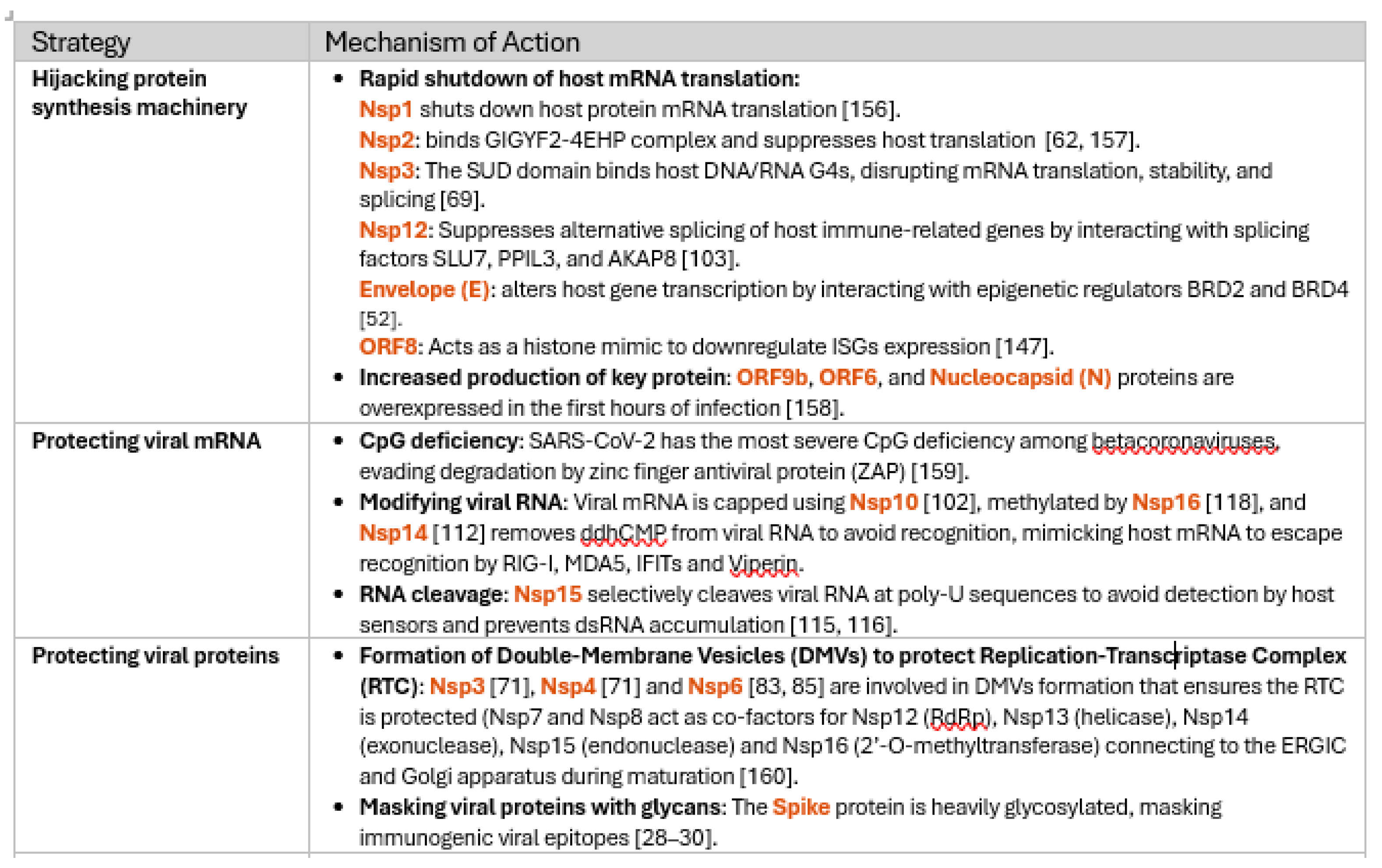

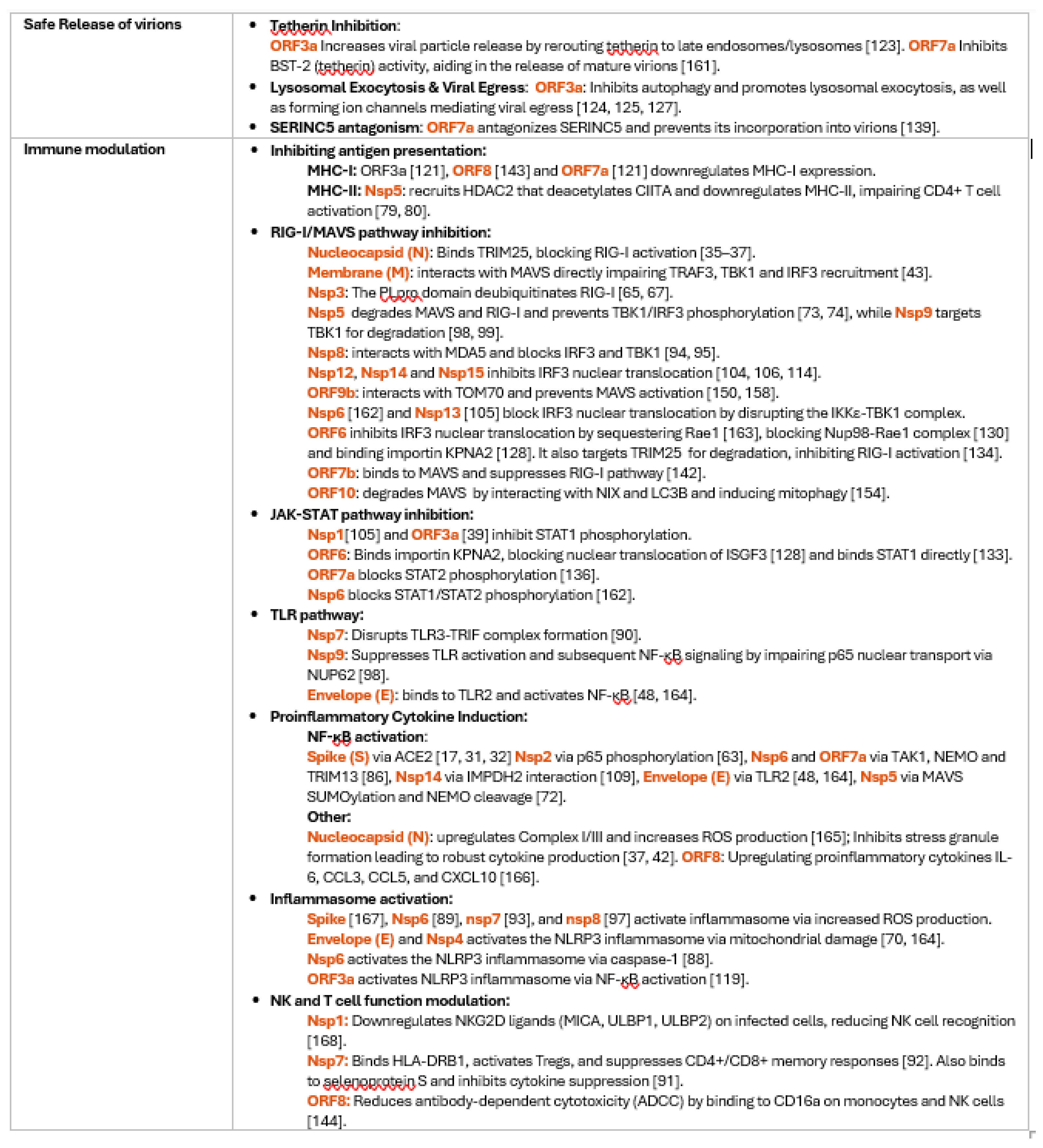

3.1. Comprehensive Review of SARS-CoV-2 Proteins and Their Immune Modulatory Effects

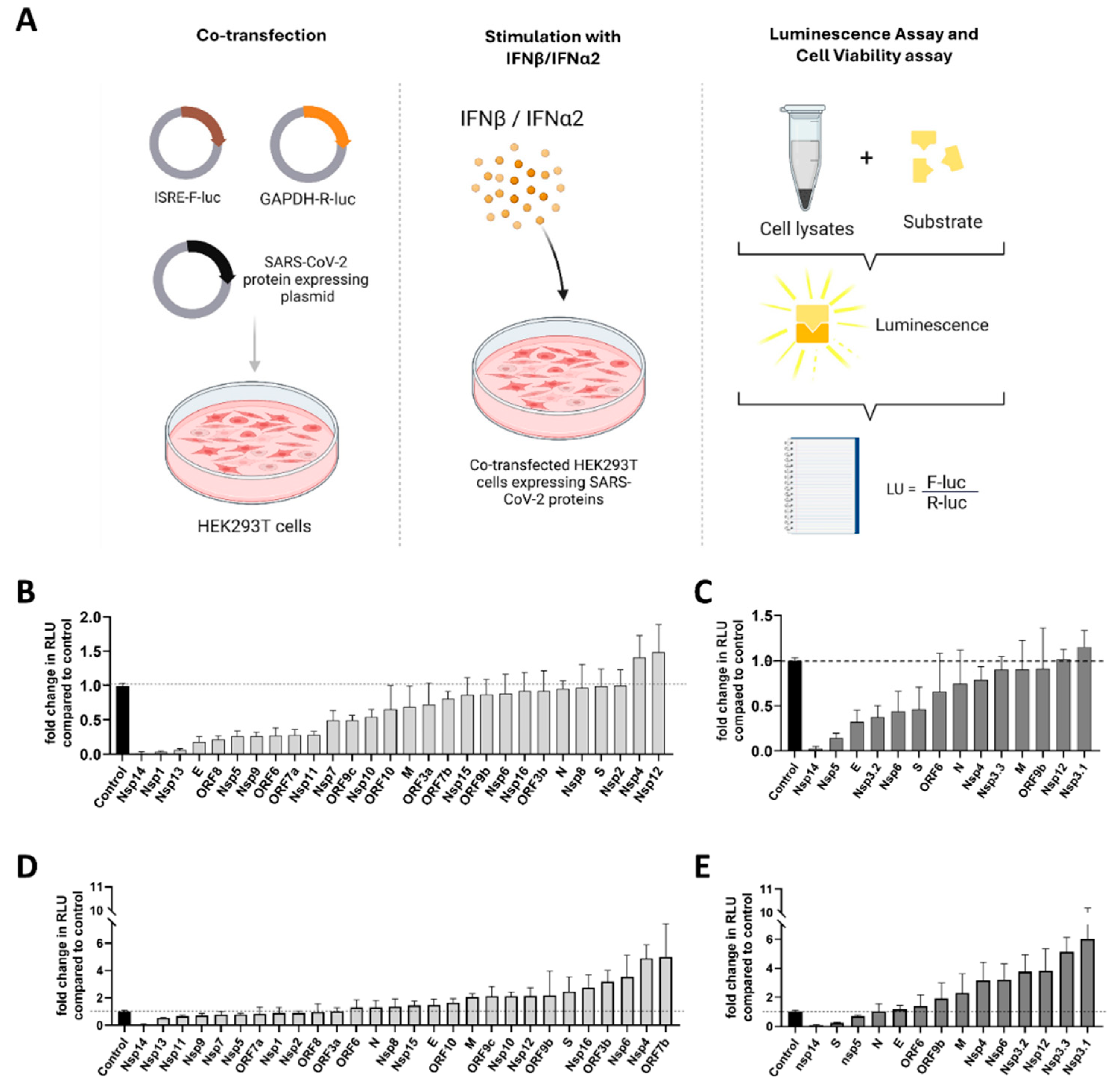

3.2. Functional Screening of SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan and Omicron Strain Proteins for Impact on Innate Immune Sensing

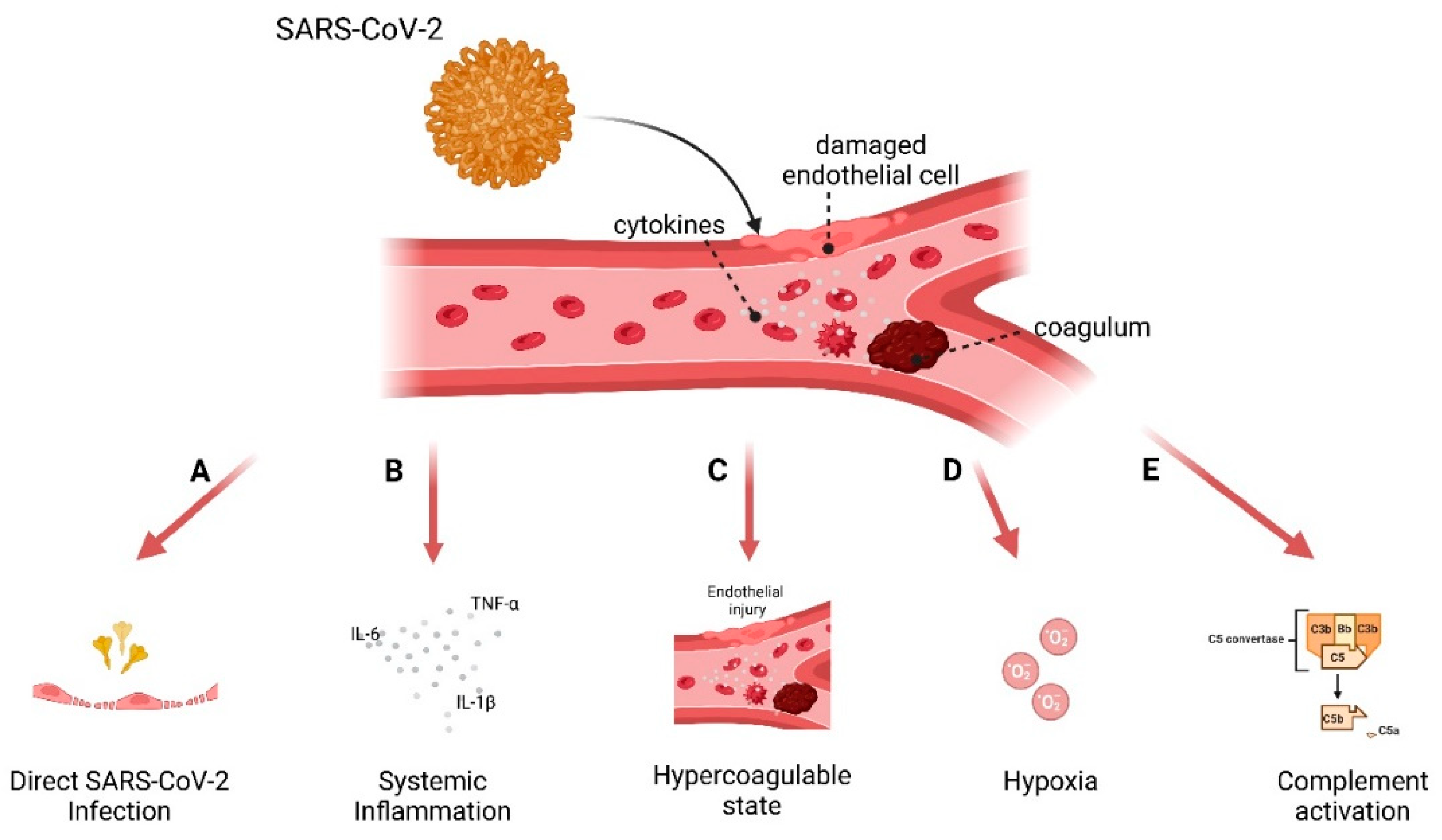

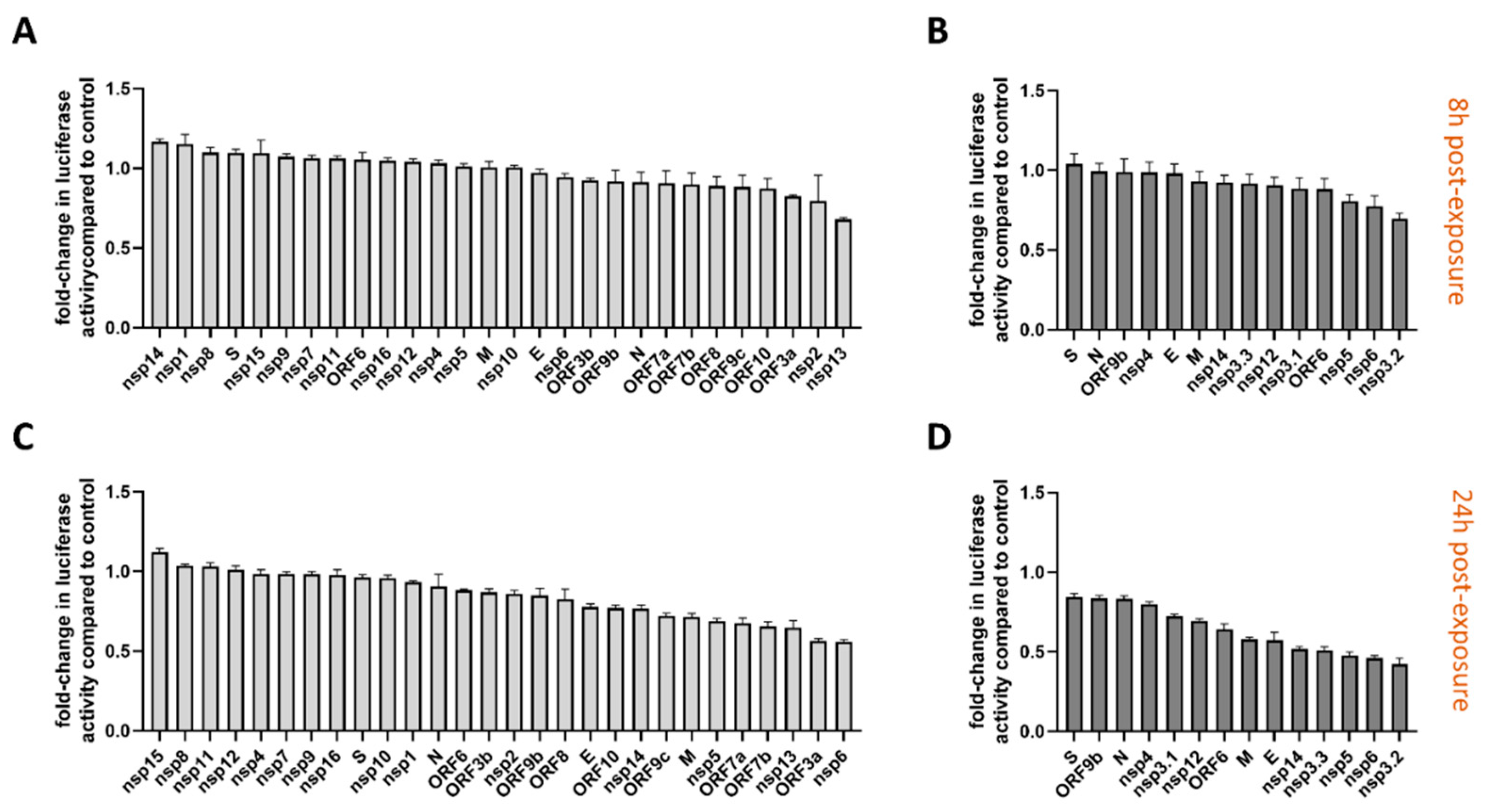

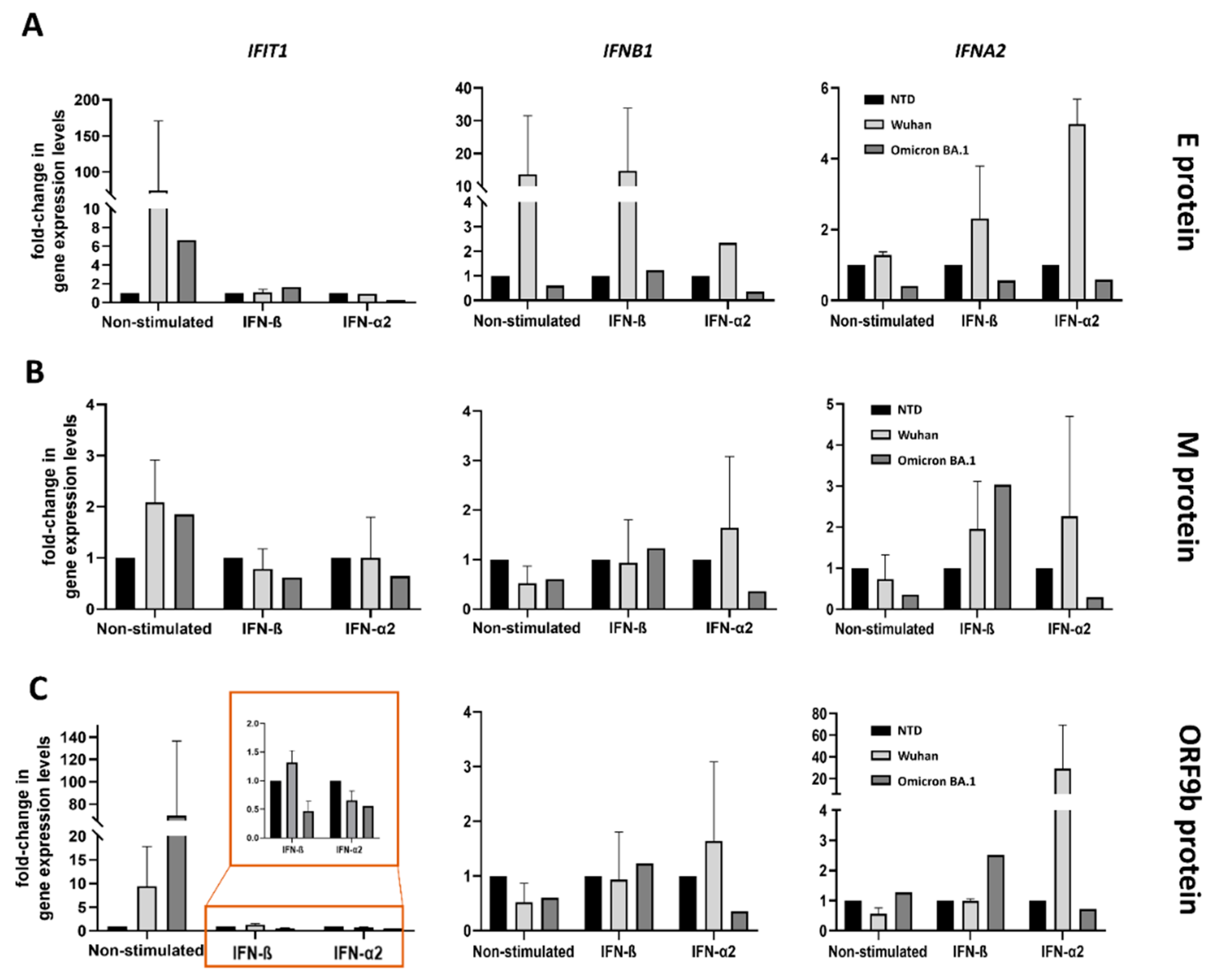

3.3. Model to Study Vascular Impact: Immune Response in Endothelial Cells

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IFN | Interferon |

| SARS-CoV | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus |

| PRRs | Pattern recognition receptors |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| RIG-I | Retinoic acid-inducible gene I |

| MAVS | Mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding kinase 1 |

| IRF | Interferon regulatory factors |

| EC | Endothelial cells |

| RTC | Replication-transcription complex |

| RLRs | RIG-I-like receptors |

| HUVEC | Human EC from umbilical vein |

| ISG | Interferon stimulated gene |

References

- Kirtipal N, Bharadwaj S, Kang SG. 2020. From SARS to SARS-CoV-2, insights on structure, pathogenicity and immunity aspects of pandemic human coronaviruses. Infect Genet Evol. 85:104502.

- Barnes CO, Jette CA, Abernathy ME, Dam K-MA, Esswein SR, Gristick HB, Malyutin AG, Sharaf NG, Huey-Tubman KE, Lee YE, Robbiani DF, Nussenzweig MC, West AP, Bjorkman PJ. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody structures inform therapeutic strategies. Nature 588:682–687.

- Cao Y, Su B, Guo X, Sun W, Deng Y, Bao L, Zhu Q, Zhang X, Zheng Y, Geng C, Chai X, He R, Li X, Lv Q, Zhu H, Deng W, Xu Y, Wang Y, Qiao L, Tan Y, Song L, Wang G, Du X, Gao N, Liu J, Xiao J, Su X, Du Z, Feng Y, Qin C, Qin C, Jin R, Xie XS. 2020. Potent Neutralizing Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 Identified by High-Throughput Single-Cell Sequencing of Convalescent Patients’ B Cells. Cell 182:73-84.

- Klasse P, Moore JP. 2020. Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and their potential for therapeutic passive immunization. Elife. 9:e57877.

- Del Sole F, Farcomeni A, Loffredo L, Carnevale R, Menichelli D, Vicario T, Pignatelli P, Pastori D. 2020. Features of severe COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 50(10):e13378.

- Rossouw TM, Anderson R, Manga P, Feldman C. 2022. Emerging Role of Platelet-Endothelium Interactions in the Pathogenesis of Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection-Associated Myocardial Injury. Front Immunol. 13:776861.

- Sievers BL, Cheng MTK, Csiba K, Meng B, Gupta RK. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 and innate immunity: the good, the bad, and the “goldilocks.” Cell Mol Immunol 21:171–183.

- Onomoto K, Onoguchi K, Yoneyama M. 2021. Regulation of RIG-I-like receptor-mediated signaling: interaction between host and viral factors. Cell Mol Immunol 18:539–555.

- Alfaro E, Díaz-García E, García-Tovar S, Galera R, Casitas R, Torres-Vargas M, López-Fernández C, Añón JM, García-Río F, Cubillos-Zapata C. 2024. Endothelial dysfunction and persistent inflammation in severe post-COVID-19 patients: implications for gas exchange. BMC Med. 22(1):242.

- Ackermann M, Kamp JC, Werlein C, Walsh CL, Stark H, Prade V, Surabattula R, Wagner WL, Disney C, Bodey AJ, Illig T, Leeming DJ, Karsdal MA, Tzankov A, Boor P, Kühnel MP, Länger FP, Verleden SE, Kvasnicka HM, Kreipe HH, Haverich A, Black SM, Walch A, Tafforeau P, Lee PD, Hoeper MM, Welte T, Seeliger B, David S, Schuppan D, Mentzer SJ, Jonigk DD. 2022. The fatal trajectory of pulmonary COVID-19 is driven by lobular ischemia and fibrotic remodelling. EBioMedicine 85:104296.

- Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, Mehra MR, Schuepbach RA, Ruschitzka F, Moch H. 2020. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. The Lancet. 395(10234):1417-1418.

- Becker RC, Tantry US, Khan M, Gurbel PA. 2024. The COVID-19 thrombus: distinguishing pathological, mechanistic, and phenotypic features and management. J Thromb Thrombolysis 58:15–49.

- Bai B, Yang Y, Wang Q, Li M, Tian C, Liu Y, Aung LHH, Li P, Yu T, Chu X. 2020. NLRP3 inflammasome in endothelial dysfunction. Cell Death Dis 11:776.

- Birnhuber A, Fließer E, Gorkiewicz G, Zacharias M, Seeliger B, David S, Welte T, Schmidt J, Olschewski H, Wygrecka M, Kwapiszewska G. 2021. Between inflammation and thrombosis: Endothelial cells in COVID-19. European Respiratory Journal. 58(3):2100377.

- Guney C, Akar F. 2021. Epithelial and Endothelial Expressions of ACE2: SARS-CoV-2 Entry Routes. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 24:84-93.

- Lei Y, Zhang J, Schiavon CR, He M, Chen L, Shen H, Zhang Y, Yin Q, Cho Y, Andrade L, Shadel GS, Hepokoski M, Lei T, Wang H, Zhang J, Yuan JX-J, Malhotra A, Manor U, Wang S, Yuan Z-Y, Shyy JY-J. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Impairs Endothelial Function via Downregulation of ACE 2. Circ Res 128:1323–1326.

- Perico L, Morigi M, Pezzotta A, Locatelli M, Imberti B, Corna D, Cerullo D, Benigni A, Remuzzi G. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces lung endothelial cell dysfunction and thrombo-inflammation depending on the C3a/C3a receptor signalling. Sci Rep 13:11392.

- Kang S, Tanaka T, Inoue H, Ono C, Hashimoto S, Kioi Y, Matsumoto H, Matsuura H, Matsubara T, Shimizu K, Ogura H, Matsuura Y, Kishimoto T. 2020. IL-6 trans-signaling induces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 from vascular endothelial cells in cytokine release syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117:22351–22356.

- Kang S, Kishimoto T. 2021. Interplay between interleukin-6 signaling and the vascular endothelium in cytokine storms. Exp Mol Med 53:1116–1123.

- Puhlmann M, Weinreich DM, Farma JM, Carroll NM, Turner EM, Alexander HR. 2005. Interleukin-1β induced vascular permeability is dependent on induction of endothelial Tissue Factor (TF) activity. J Transl Med 3:37.

- Kandhaya-Pillai R, Yang X, Tchkonia T, Martin GM, Kirkland JL, Oshima J. 2022. TNF-α/IFN-γ synergy amplifies senescence-associated inflammation and SARS-CoV-2 receptor expression via hyper-activated JAK/STAT1. Aging Cell 21(6):e13646.

- Valencia I, Lumpuy-Castillo J, Magalhaes G, Sánchez-Ferrer CF, Lorenzo Ó, Peiró C. 2024. Mechanisms of endothelial activation, hypercoagulation and thrombosis in COVID-19: a link with diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 23:75.

- Won T, Wood MK, Hughes DM, Talor M V., Ma Z, Schneider J, Skinner JT, Asady B, Goerlich E, Halushka MK, Hays AG, Kim D-H, Parikh CR, Rosenberg AZ, Coppens I, Johns RA, Gilotra NA, Hooper JE, Pekosz A, Čiháková D. 2022. Endothelial thrombomodulin downregulation caused by hypoxia contributes to severe infiltration and coagulopathy in COVID-19 patient lungs. EBioMedicine 75:103812.

- Jin Y, Ji W, Yang H, Chen S, Zhang W, Duan G. 2020. Endothelial activation and dysfunction in COVID-19: from basic mechanisms to potential therapeutic approaches. Signal Transduct Target Ther 5:293.

- Lim EHT, van Amstel RBE, de Boer VV, van Vught LA, de Bruin S, Brouwer MC, Vlaar APJ, van de Beek D. 2023. Complement activation in COVID-19 and targeted therapeutic options: A scoping review. Blood Rev 57:100995.

- Conway EM, Pryzdial ELG. 2020. Is the COVID-19 thrombotic catastrophe complement-connected? Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 18:2812–2822.

- Laha S, Chakraborty J, Das S, Manna SK, Biswas S, Chatterjee R. 2020. Characterizations of SARS-CoV-2 mutational profile, spike protein stability and viral transmission. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 85:104445.

- Watanabe Y, Allen JD, Wrapp D, McLellan JS, Crispin M. 2020. Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Science 369:330–333.

- Gong Y, Qin S, Dai L, Tian Z. 2021. The glycosylation in SARS-CoV-2 and its receptor ACE2. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6(1):396.

- Harvey WT, Carabelli AM, Jackson B, Gupta RK, Thomson EC, Harrison EM, Ludden C, Reeve R, Rambaut A, Peacock SJ, Robertson DL. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol. 19(7):409-424.

- Montezano AC, Camargo LL, Mary S, Neves KB, Rios FJ, Stein R, Lopes RA, Beattie W, Thomson J, Herder V, Szemiel AM, McFarlane S, Palmarini M, Touyz RM. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces endothelial inflammation via ACE2 independently of viral replication. Sci Rep 13(1):14086.

- Urata R, Ikeda K, Yamazaki E, Ueno D, Katayama A, Shin-Ya M, Ohgitani E, Mazda O, Matoba S. 2022. Senescent endothelial cells are predisposed to SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent endothelial dysfunction. Sci Rep 12(1):11855.

- Li F, Li J, Wang PH, Yang N, Huang J, Ou J, Xu T, Zhao X, Liu T, Huang X, Wang Q, Li M, Yang L, Lin Y, Cai Y, Chen H, Zhang Q. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 spike promotes inflammation and apoptosis through autophagy by ROS-suppressed PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1867(12):166260.

- Scheim DE, Vottero P, Santin AD, Hirsh AG. 2023. Sialylated Glycan Bindings from SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein to Blood and Endothelial Cells Govern the Severe Morbidities of COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci. 24(23):17039.

- Savellini GG, Anichini G, Gandolfo C, Cusi MG. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 n protein targets TRIM25-mediated RIG-I activation to suppress innate immunity. Viruses 13(8):1439.

- Oh SJ, Shin OS. 2021. Sars-cov-2 nucleocapsid protein targets rig-i-like receptor pathways to inhibit the induction of interferon response. Cells 10:1–13.

- Wang W, Chen J, Yu X, Lan HY. 2022. Signaling mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid protein in viral infection, cell death and inflammation. Int J Biol Sci. 18(12):4704-4713.

- Zhao Y, Sui L, Wu P, Wang W, Wang Z, Yu Y, Hou Z, Tan G, Liu Q, Wang G. 2021. A dual-role of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein in regulating innate immune response. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6(1):331.

- Xia H, Cao Z, Xie X, Zhang X, Chen JYC, Wang H, Menachery VD, Rajsbaum R, Shi PY. 2020. Evasion of Type I Interferon by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep 33(1):108234.

- Huang C, Yin Y, Pan P, Huang Y, Chen S, Chen J, Wang J, Xu G, Tao X, Xiao X, Li J, Yang J, Jin Z, Li B, Tong Z, Du W, Liu L, Liu Z. 2023. The Interaction between SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and UBC9 Inhibits MAVS Ubiquitination by Enhancing Its SUMOylation. Viruses 15(12):2304.

- Guo X, Yang S, Cai Z, Zhu S, Wang H, Liu Q, Zhang Z, Feng J, Chen X, Li Y, Deng J, Liu J, Li J, Tan X, Fu Z, Xu K, Zhou L, Chen Y. 2025. SARS-CoV-2 specific adaptations in N protein inhibit NF-κB activation and alter pathogenesis. Journal of Cell Biology 224(1):e202404131.

- Carlson CR, Asfaha JB, Ghent CM, Howard CJ, Hartooni N, Safari M, Frankel AD, Morgan DO. 2020. Phosphoregulation of Phase Separation by the SARS-CoV-2 N Protein Suggests a Biophysical Basis for its Dual Functions. Mol Cell 80:1092-1103.e4.

- Fu YZ, Wang SY, Zheng ZQ, Yi Huang, Li WW, Xu ZS, Wang YY. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 membrane glycoprotein M antagonizes the MAVS-mediated innate antiviral response. Cell Mol Immunol 18:613–620.

- Lopandić Z, Protić-Rosić I, Todorović A, Glamočlija S, Gnjatović M, Ćujic D, Gavrović-Jankulović M. 2021. IgM and IgG Immunoreactivity of SARS-CoV-2 Recombinant M Protein. Int J Mol Sci 22(9):4951.

- Liu J, Wu S, Zhang Y, Wang C, Liu S, Wan J, Yang L. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 viral genes Nsp6, Nsp8, and M compromise cellular ATP levels to impair survival and function of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res Ther 14(1):249.

- Cao Y, Yang R, Lee I, Zhang W, Sun J, Wang W, Meng X. 2021. Characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 E Protein: Sequence, Structure, Viroporin, and Inhibitors. Protein Sci. 30(6):1114-1130.

- Xia B, Shen X, He Y, Pan X, Liu FL, Wang Y, Yang F, Fang S, Wu Y, Duan Z, Zuo X, Xie Z, Jiang X, Xu L, Chi H, Li S, Meng Q, Zhou H, Zhou Y, Cheng X, Xin X, Jin L, Zhang HL, Yu DD, Li MH, Feng XL, Chen J, Jiang H, Xiao G, Zheng YT, Zhang LK, Shen J, Li J, Gao Z. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein causes acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)-like pathological damages and constitutes an antiviral target. Cell Res 31:847–860.

- Planès R, Bert JB, Tairi S, Benmohamed L, Bahraoui E. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Envelope (E) Protein Binds and Activates TLR2 Pathway: A Novel Molecular Target for COVID-19 Interventions. Viruses 14(5):999.

- Geanes ES, McLennan R, Pierce SH, Menden HL, Paul O, Sampath V, Bradley T. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein regulates innate immune tolerance. iScience 27(6):109975.

- Zheng M, Karki R, Williams EP, Yang D, Fitzpatrick E, Vogel P, Jonsson CB, Kanneganti TD. 2021. TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol 22:829–838.

- Lu H, Liu Z, Deng X, Chen S, Zhou R, Zhao R, Parandaman R, Thind A, Henley J, Tian L, Yu J, Comai L, Feng P, Yuan W. 2023. Potent NKT cell ligands overcome SARS-CoV-2 immune evasion to mitigate viral pathogenesis in mouse models. PLoS Pathog 19(3):e1011240.

- Bhat S, Rishi P, Chadha VD. 2022. Understanding the epigenetic mechanisms in SARS CoV-2 infection and potential therapeutic approaches. Virus Res. 318:198853.

- Schubert K, Karousis ED, Jomaa A, Scaiola A, Echeverria B, Gurzeler LA, Leibundgut M, Thiel V, Mühlemann O, Ban N. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp1 binds the ribosomal mRNA channel to inhibit translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 27:959–966.

- Frolov I, Agback T, Palchevska O, Dominguez F, Lomzov A, Agback P, Frolova EI. 2023. All Domains of SARS-CoV-2 nsp1 Determine Translational Shutoff and Cytotoxicity of the Protein. J Virol 97(3):e0186522.

- Zhang K, Miorin L, Makio T, Dehghan I, Gao S, Xie Y, Zhong H, Esparza M, Kehrer T, Kumar A, Hobman TC, Ptak C, Gao B, Minna JD, Chen Z, García-Sastre A, Ren Y, Wozniak RW, Fontoura BMA. 2021. Nsp1 protein of SARS-CoV-2 disrupts the mRNA export machinery to inhibit host gene expression. Sci Adv. 7(6):eabe7386.

- Fisher T, Gluck A, Narayanan K, Kuroda M, Nachshon A, Hsu JC, Halfmann PJ, Yahalom-Ronen Y, Tamir H, Finkel Y, Schwartz M, Weiss S, Tseng CTK, Israely T, Paran N, Kawaoka Y, Makino S, Stern-Ginossar N. 2022. Parsing the role of NSP1 in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Rep 39(11):110954.

- Lokugamage KG, Narayanan K, Huang C, Makino S. 2012. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Protein nsp1 Is a Novel Eukaryotic Translation Inhibitor That Represses Multiple Steps of Translation Initiation. J Virol 86:13598–13608.

- Vazquez C, Swanson SE, Negatu SG, Dittmar M, Miller J, Ramage HR, Cherry S, Jurado KA. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins NSP1 and NSP13 inhibit interferon activation through distinct mechanisms. PLoS One 16(6):e0253089.

- Lui WY, Ong CP, Cheung PHH, Ye ZW, Chan CP, To KKW, Yuen KS, Jin DY. 2024. Nsp1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 replication through calcineurin-NFAT signaling. mBio 15(4):e0039224.

- Lee MJ, Leong MW, Rustagi A, Beck A, Zeng L, Holmes S, Qi LS, Blish CA. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 escapes direct NK cell killing through Nsp1-mediated downregulation of ligands for NKG2D. Cell Rep 41(13):111892.

- Xu Z, Choi J-H, Dai DL, Luo J, Ladak RJ, Li Q, Wang Y, Zhang C, Wiebe S, Liu ACH, Ran X, Yang J, Naeli P, Garzia A, Zhou L, Mahmood N, Deng Q, Elaish M, Lin R, Mahal LK, Hobman TC, Pelletier J, Alain T, Vidal SM, Duchaine T, Mazhab-Jafari MT, Mao X, Jafarnejad SM, Sonenberg N. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 impairs interferon production via NSP2-induced repression of mRNA translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 119(32):e2204539119.

- Zou L, Moch C, Graille M, Chapat C. 2022. The SARS-CoV-2 protein NSP2 impairs the silencing capacity of the human 4EHP-GIGYF2 complex. iScience 25(7):104646.

- Lacasse É, Gudimard L, Dubuc I, Gravel A, Allaeys I, Boilard É, Flamand L. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp2 Contributes to Inflammation by Activating NF-κB. Viruses 15(2):334.

- Khan MT, Zeb MT, Ahsan H, Ahmed A, Ali A, Akhtar K, Malik SI, Cui Z, Ali S, Khan AS, Ahmad M, Wei DQ, Irfan M. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and Nsp3 binding: an in silico study. Arch Microbiol 203:59–66.

- Fu Z, Huang B, Tang J, Liu S, Liu M, Ye Y, Liu Z, Xiong Y, Zhu W, Cao D, Li J, Niu X, Zhou H, Zhao YJ, Zhang G, Huang H. 2021. The complex structure of GRL0617 and SARS-CoV-2 PLpro reveals a hot spot for antiviral drug discovery. Nat Commun 12(1):488.

- Clemente V, D’arcy P, Bazzaro M. 2020. Deubiquitinating enzymes in coronaviruses and possible therapeutic opportunities for COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci. 21(10):3492.

- Russo LC, Tomasin R, Matos IA, Manucci AC, Sowa ST, Dale K, Caldecott KW, Lehtiö L, Schechtman D, Meotti FC, Bruni-Cardoso A, Hoch NC. 2021. The SARS-CoV-2 Nsp3 macrodomain reverses PARP9/DTX3L-dependent ADP-ribosylation induced by interferon signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry 297(3):101041.

- Garvanska DH, Alvarado RE, Mundt FO, Lindqvist R, Duel JK, Coscia F, Nilsson E, Lokugamage K, Johnson BA, Plante JA, Morris DR, Vu MN, Estes LK, McLeland AM, Walker J, Crocquet-Valdes PA, Mendez BL, Plante KS, Walker DH, Weisser MB, Överby AK, Mann M, Menachery VD, Nilsson J. 2024. The NSP3 protein of SARS-CoV-2 binds fragile X mental retardation proteins to disrupt UBAP2L interactions. EMBO Rep 25:902–926.

- Lavigne M, Helynck O, Rigolet P, Boudria-Souilah R, Nowakowski M, Baron B, Brülé S, Hoos S, Raynal B, Guittat L, Beauvineau C, Petres S, Granzhan A, Guillon J, Pratviel G, Teulade-Fichou MP, England P, Mergny JL, Munier-Lehmann H. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp3 unique domain SUD interacts with guanine quadruplexes and G4-ligands inhibit this interaction. Nucleic Acids Res 49:7695–7712.

- Faizan MI, Chaudhuri R, Sagar S, Albogami S, Chaudhary N, Azmi I, Akhtar A, Ali SM, Kumar R, Iqbal J, Joshi MC, Kharya G, Seth P, Roy SS, Ahmad T. 2022. NSP4 and ORF9b of SARS-CoV-2 Induce Pro-Inflammatory Mitochondrial DNA Release in Inner Membrane-Derived Vesicles. Cells 11(19):2969.

- Zimmermann L, Zhao X, Makroczyova J, Wachsmuth-Melm M, Prasad V, Hensel Z, Bartenschlager R, Chlanda P. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 nsp3 and nsp4 are minimal constituents of a pore spanning replication organelle. Nat Commun 14(1):7894.

- Li W, Qiao J, You Q, Zong S, Peng Q, Liu Y, Hu S, Liu W, Li S, Shu X, Sun B. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp5 Activates NF-κB Pathway by Upregulating SUMOylation of MAVS. Front Immunol 12:750969.

- Liu Y, Qin C, Rao Y, Ngo C, Feng JJ, Zhao J, Zhang S, Wang T-Y, Carriere E, Savas AC, Zarinfar M, Rice S, Yang H, Yuan W, Camarero JA, Yu J, Chen XS, Zhang C, Feng P. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp5 Demonstrates Two Distinct Mechanisms Targeting RIG-I and MAVS To Evade the Innate Immune Response. mBio. 12(5):e0233521.

- Zheng Y, Deng J, Han L, Zhuang MW, Xu Y, Zhang J, Nan ML, Xiao Y, Zhan P, Liu X, Gao C, Wang PH. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 NSP5 and N protein counteract the RIG-I signaling pathway by suppressing the formation of stress granules. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7(1):22.

- Shemesh M, Aktepe TE, Deerain JM, McAuley JL, Audsley MD, David CT, Purcell DFJ, Urin V, Hartmann R, Moseley GW, Mackenzie JM, Schreiber G, Harari D. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 suppresses IFNβ production mediated by NSP1, 5, 6, 15, ORF6 and ORF7b but does not suppress the effects of added interferon. PLoS Pathog 17(8):e1009800.

- Chen J, Li Z, Guo J, Xu S, Zhou J, Chen Q, Tong X, Wang D, Peng G, Fang L, Xiao S. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 nsp5 Exhibits Stronger Catalytic Activity and Interferon Antagonism than Its SARS-CoV Ortholog. J Virol 96(8):e0003722.

- Lu JL, Zhou XL. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 main protease Nsp5 cleaves and inactivates human tRNA methyltransferase TRMT1. J Mol Cell Biol. 15(4):mjad024.

- Ju X, Wang Z, Wang P, Ren W, Yu Y, Yu Y, Yuan B, Song J, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Xu C, Tian B, Shi Y, Zhang R, Ding Q. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 main protease cleaves MAGED2 to antagonize host antiviral defense. mBio 14:e0137323.

- Naik NG, Lee S-C, Veronese BHS, Ma Z, Toth Z. 2022. Interaction of HDAC2 with SARS-CoV-2 NSP5 and IRF3 Is Not Required for NSP5-Mediated Inhibition of Type I Interferon Signaling Pathway. Microbiol Spectr 10(5):e0232222.

- Taefehshokr N, Lac A, Vrieze AM, Dickson BH, Guo PN, Jung C, Blythe EN, Fink C, Aktar A, Dikeakos JD, Dekaban GA, Heit B. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 NSP5 antagonizes MHC II expression by subverting histone deacetylase 2. J Cell Sci 137(10):jcs262172.

- Bhat S, Rishi P, Chadha VD. 2022. Understanding the epigenetic mechanisms in SARS CoV-2 infection and potential therapeutic approaches. Virus Res. 318:198853.

- Li Y, Yu Q, Huang R, Chen H, Ren H, Ma L, He Y, Li W. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 SUD2 and Nsp5 Conspire to Boost Apoptosis of Respiratory Epithelial Cells via an Augmented Interaction with the G-Quadruplex of BclII. mBio 14(2):e0335922.

- Zhang C, Jiang Q, Liu Z, Li N, Hao Z, Song G, Li D, Chen M, Lin L, Liu Y, Li X, Shang C, Li Y. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 reduces autophagosome size and affects viral replication via sigma-1 receptor. J Virol 98(11):e0075424.

- Jiao P, Fan W, Ma X, Lin R, Zhao Y, Li Y, Zhang H, Jia X, Bi Y, Feng X, Li M, Liu W, Zhang K, Sun L. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein 6 triggers endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced autophagy to degrade STING1. Autophagy 19:3113–3131.

- Benvenuto D, Angeletti S, Giovanetti M, Bianchi M, Pascarella S, Cauda R, Ciccozzi M, Cassone A. 2020. Evolutionary analysis of SARS-CoV-2: how mutation of Non-Structural Protein 6 (NSP6) could affect viral autophagy. Journal of Infection 81:e24–e27.

- Nishitsuji H, Iwahori S, Ohmori M, Shimotohno K, Murata T. 2022. Ubiquitination of SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 and ORF7a Facilitates NF-κB Activation. mBio 13(4):e0097122.

- Bills CJ, Xia H, Chen JYC, Yeung J, Kalveram BK, Walker D, Xie X, Shi PY. 2023. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 variant nsp6 enhance type-I interferon antagonism. Emerg Microbes Infect 12(1):2209208.

- Sun X, Liu Y, Huang Z, Xu W, Hu W, Yi L, Liu Z, Chan H, Zeng J, Liu X, Chen H, Yu J, Chan FKL, Ng SC, Wong SH, Wang MH, Gin T, Joynt GM, Hui DSC, Zou X, Shu Y, Cheng CHK, Fang S, Luo H, Lu J, Chan MTV, Zhang L, Wu WKK. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 non-structural protein 6 triggers NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis by targeting ATP6AP1. Cell Death Differ 29:1240–1254.

- Zhu J yi, Wang G, Huang X, Lee H, Lee JG, Yang P, van de Leemput J, Huang W, Kane MA, Yang P, Han Z. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp6 damages Drosophila heart and mouse cardiomyocytes through MGA/MAX complex-mediated increased glycolysis. Commun Biol 5(1):1039.

- Deng J, Zheng Y, Zheng SN, Nan ML, Han L, Zhang J, Jin Y, Pan JA, Gao C, Wang PH. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 NSP7 inhibits type I and III IFN production by targeting the RIG-I/MDA5, TRIF, and STING signaling pathways. J Med Virol 95(3):e28561.

- Ghelichkhani F, Gonzalez FA, Kapitonova MA, Rozovsky S. 2023. Selenoprotein S Interacts with the Replication and Transcription Complex of SARS-CoV-2 by Binding nsp7. J Mol Biol 435(8):168008.

- Miah SMS, Lelias S, Gutierrez AH, McAllister M, Boyle CM, Moise L, De Groot AS. 2023. A SARS-CoV-2 NSP7 homolog of a Treg epitope suppresses CD4+ and CD8+ T cell memory responses. Front Immunol 14:1290688.

- Guo J, Li WL, Huang M, Qiao J, Wan P, Yao Y, Ye L, Ding Y, Wang J, Peng Q, Liu W, Xia Y, Shu X, Sun B. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp7 plays a role in cognitive dysfunction by impairing synaptic plasticity. Front Neurosci 18:1490099.

- Yang Z, Zhang X, Wang F, Wang P, Kuang E, Li X. 2020. Suppression of MDA5-mediated antiviral immune responses by NSP8 of SARS-CoV-2 Emerg Microbes Infect. 81:e24.

- Zhang X, Yang Z, Pan T, Sun Q, Chen Q, Wang PH, Li X, Kuang E. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp8 suppresses MDA5 antiviral immune responses by impairing TRIM4-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination. PLoS Pathog 19(11):e1011792.

- Liu J, Wu S, Zhang Y, Wang C, Liu S, Wan J, Yang L. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 viral genes Nsp6, Nsp8, and M compromise cellular ATP levels to impair survival and function of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res Ther 14(1):249.

- Zong S, Wu Y, Li W, You Q, Peng Q, Wang C, Wan P, Bai T, Ma Y, Sun B, Qiao J. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp8 induces mitophagy by damaging mitochondria. Virol Sin 38:520–530.

- Makiyama K, Hazawa M, Kobayashi A, Lim K, Voon DC, Wong RW. 2022. NSP9 of SARS-CoV-2 attenuates nuclear transport by hampering nucleoporin 62 dynamics and functions in host cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 586:137–142.

- Zhang Y, Xin B, Liu Y, Jiang W, Han W, Deng J, Wang P, Hong X, Yan D. 2023. SARS-COV-2 protein NSP9 promotes cytokine production by targeting TBK1. Front Immunol 14:1211816.

- Lundrigan E, Toudic C, Pennock E, Pezacki JP. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 Protein Nsp9 Is Involved in Viral Evasion through Interactions with Innate Immune Pathways. ACS Omega 9:26428–26438.

- Benoni R, Krafcikova P, Baranowski MR, Kowalska J, Boura E, Cahová H. 2021. Substrate specificity of sars-cov-2 nsp10-nsp16 methyltransferase. Viruses 13(9):1722.

- Wang H, Rizvi SR, Dong D, Lou J, Wang Q, Sopipong W, Su Y, Najar F, Agarwal PK, Kozielski F, Haider S. 2023. Emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 NSP10 highlight strong functional conservation of its binding to two non-structural proteins, NSP14 and NSP16. Elife 12:RP87884.

- Yang L, Zeng XT, Luo RH, Ren SX, Liang LL, Huang QX, Tang Y, Fan H, Ren HY, Zhang WJ, Zheng YT, Cheng W. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 NSP12 utilizes various host splicing factors for replication and splicing regulation. J Med Virol. 96(1):e29396.

- Wang W, Zhou Z, Xiao X, Tian Z, Dong X, Wang C, Li L, Ren L, Lei X, Xiang Z, Wang J. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 nsp12 attenuates type I interferon production by inhibiting IRF3 nuclear translocation. Cell Mol Immunol 18:945–953.

- Vazquez C, Swanson SE, Negatu SG, Dittmar M, Miller J, Ramage HR, Cherry S, Jurado KA. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins NSP1 and NSP13 inhibit interferon activation through distinct mechanisms. PLoS One 16(6):e0253089.

- Yuen CK, Lam JY, Wong WM, Mak LF, Wang X, Chu H, Cai JP, Jin DY, To KKW, Chan JFW, Yuen KY, Kok KH. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 nsp13, nsp14, nsp15 and orf6 function as potent interferon antagonists. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:1418–1428.

- Feng K, Zhang HJ, Min YQ, Zhou M, Deng F, Wang HL, Li PQ, Ning YJ. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 interacts with host IRF3, blocking antiviral immune responses. J Med Virol 95(6):e28881.

- Fung SY, Siu KL, Lin H, Chan CP, Yeung ML, Jin DY. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase suppresses interferon signaling by perturbing JAK1 phosphorylation of STAT1. Cell Biosci 12(1):36.

- Li TW, Kenney AD, Park JG, Fiches GN, Liu H, Zhou D, Biswas A, Zhao W, Que J, Santoso N, Martinez-Sobrido L, Yount JS, Zhu J. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp14 protein associates with IMPDH2 and activates NF-κB signaling. Front Immunol 13:1007089.

- Zaffagni M, Harris JM, Patop IL, Reddy Pamudurti N, Nguyen S, Kadener S. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp14 mediates the effects of viral infection on the host cell Elife. 11:e71945.

- Tofaute MJ, Weller B, Graß C, Halder H, Dohai B, Falter-Braun P, Krappmann D. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 MTase activity is critical for inducing canonical NF-κB activation. Biosci Rep 44(1):BSR20231418.

- Moeller NH, Passow KT, Harki DA, Aihara H. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 nsp14 Exoribonuclease Removes the Natural Antiviral 3′-Deoxy-3′,4′-didehydro-cytidine Nucleotide from RNA. Viruses 14(8):1790.

- Walter M, Chen IP, Vallejo-Gracia A, Kim I-J, Bielska O, Lam VL, Hayashi JM, Cruz A, Shah S, Soveg FW, Gross JD, Krogan NJ, Jerome KR, Schilling B, Ott M, Verdin E. 2022. SIRT5 is a proviral factor that interacts with SARS-CoV-2 Nsp14 protein. PLoS Pathog 18:e1010811.

- Zhang D, Ji L, Chen X, He Y, Sun Y, Ji L, Zhang T, Shen Q, Wang X, Wang Y, Yang S, Zhang W, Zhou C. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp15 suppresses type I interferon production by inhibiting IRF3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. iScience 26(9):107705.

- Otter CJ, Bracci N, Parenti NA, Ye C, Asthana A, Blomqvist EK, Tan LH, Pfannenstiel JJ, Jackson N, Fehr AR, Silverman RH, Burke JM, Cohen NA, Martinez-Sobrido L, Weiss SR. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 nsp15 endoribonuclease antagonizes dsRNA-induced antiviral signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 121(15):e2320194121.

- Wang X, Zhu B. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 nsp15 preferentially degrades AU-rich dsRNA via its dsRNA nickase activity. Nucleic Acids Res 52:5257–5272.

- Vithani N, Ward MD, Zimmerman MI, Novak B, Borowsky JH, Singh S, Bowman GR. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp16 activation mechanism and a cryptic pocket with pan-coronavirus antiviral potential. Biophys J 120:2880–2889.

- Russ A, Wittmann S, Tsukamoto Y, Herrmann A, Deutschmann J, Lagisquet J, Ensser A, Kato H, Gramberg T. 2022. Nsp16 shields SARS–CoV -2 from efficient MDA5 sensing and IFIT1 -mediated restriction . EMBO Rep. 23(12):e55648.

- Xu H, Akinyemi IA, Chitre SA, Loeb JC, Lednicky JA, McIntosh MT, Bhaduri-McIntosh S. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 viroporin encoded by ORF3a triggers the NLRP3 inflammatory pathway. Virology 568:13–22.

- Nie Y, Mou L, Long Q, Deng D, Hu R, Cheng J, Wu J. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a positively regulates NF-κB activity by enhancing IKKβ-NEMO interaction. Virus Res 328:199086.

- Arshad N, Laurent-Rolle M, Ahmed WS, Hsu JCC, Mitchell SM, Pawlak J, Sengupta D, Biswas KH, Cresswell P. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins ORF7a and ORF3a use distinct mechanisms to down-regulate MHC-I surface expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 120(1):e2208525120.

- Ren Y, Shu T, Wu D, Mu J, Wang C, Huang M, Han Y, Zhang XY, Zhou W, Qiu Y, Zhou X. 2020. The ORF3a protein of SARS-CoV-2 induces apoptosis in cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 17(8):881-883.

- Stewart H, Palmulli R, Johansen KH, McGovern N, Shehata OM, Carnell GW, Jackson HK, Lee JS, Brown JC, Burgoyne T, Heeney JL, Okkenhaug K, Firth AE, Peden AA, Edgar JR. 2023. Tetherin antagonism by SARS-CoV -2 ORF3a and spike protein enhances virus release . EMBO Rep 24(12):e57224.

- Chen D, Zheng Q, Sun L, Ji M, Li Y, Deng H, Zhang H. 2021. ORF3a of SARS-CoV-2 promotes lysosomal exocytosis-mediated viral egress. Dev Cell 56:3250-3263.e5.

- Miao G, Zhao H, Li Y, Ji M, Chen Y, Shi Y, Bi Y, Wang P, Zhang H. 2021. ORF3a of the COVID-19 virus SARS-CoV-2 blocks HOPS complex-mediated assembly of the SNARE complex required for autolysosome formation. Dev Cell 56:427-442.e5.

- Zhang Y, Sun H, Pei R, Mao B, Zhao Z, Li H, Lin Y, Lu K. 2021. The SARS-CoV-2 protein ORF3a inhibits fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. Cell Discov 7(1):31.

- Walia K, Sharma A, Paul S, Chouhan P, Kumar G, Ringe R, Sharma M, Tuli A. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 virulence factor ORF3a blocks lysosome function by modulating TBC1D5-dependent Rab7 GTPase cycle. Nat Commun. 15(1):2053.

- Suleman M, Said A, Khan H, Rehman SU, Alshammari A, Crovella S, Yassine HM. 2024. Mutational analysis of SARS-CoV-2 ORF6-KPNA2 binding interface and identification of potent small molecule inhibitors to recuse the host immune system. Front Immunol 14:1266776.

- Addetia A, Lieberman NAP, Phung Q, Hsiang T-Y, Xie H, Roychoudhury P, Shrestha L, Loprieno MA, Huang M-L, Gale M, Jerome KR, Greninger AL. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 ORF6 Disrupts Bidirectional Nucleocytoplasmic Transport through Interactions with Rae1 and Nup98. mBio. 12(2):e00065-21.

- Miorin L, Kehrer T, Teresa Sanchez-Aparicio M, Zhang K, Cohen P, Patel RS, Cupic A, Makio T, Mei M, Moreno E, Danziger O, White KM, Rathnasinghe R, Uccellini M, Gao S, Aydillo T, Mena I, Yin X, Martin-Sancho L, Krogan NJ, Chanda SK, Schotsaert M, Wozniak RW, Ren Y, Rosenberg BR, A Fontoura BM, García-Sastre A. SARS-CoV-2 Orf6 hijacks Nup98 to block STAT nuclear import and antagonize interferon signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 117(45):28344-28354.

- Kehrer T, Cupic A, Ye C, Yildiz S, Bouhaddou M, Crossland NA, Barrall EA, Cohen P, Tseng A, Çağatay T, Rathnasinghe R, Flores D, Jangra S, Alam F, Mena I, Aslam S, Saqi A, Rutkowska M, Ummadi MR, Pisanelli G, Richardson RB, Veit EC, Fabius JM, Soucheray M, Polacco BJ, Ak B, Marin A, Evans MJ, Swaney DL, Gonzalez-Reiche AS, Sordillo EM, van Bakel H, Simon V, Zuliani-Alvarez L, Fontoura BMA, Rosenberg BR, Krogan NJ, Martinez-Sobrido L, García-Sastre A, Miorin L. 2023. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 ORF6 and its variant polymorphisms on host responses and viral pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 31:1668-1684.e12.

- Hall R, Guedan A, Yap MW, Young GR, Harvey R, Stoye JP, Bishop KN. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 ORF6 disrupts innate immune signalling by inhibiting cellular mRNA export. PLoS Pathog 18(8):e1010349.

- Miyamoto Y, Itoh Y, Suzuki T, Tanaka T, Sakai Y, Koido M, Hata C, Wang CX, Otani M, Moriishi K, Tachibana T, Kamatani Y, Yoneda Y, Okamoto T, Oka M. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 ORF6 disrupts nucleocytoplasmic trafficking to advance viral replication. Commun Biol 5(1):483.

- Khatun O, Sharma M, Narayan R, Tripathi S. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 ORF6 protein targets TRIM25 for proteasomal degradation to diminish K63-linked RIG-I ubiquitination and type-I interferon induction. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 80(12):364.

- López-Ayllón BD, de Lucas-Rius A, Mendoza-García L, García-García T, Fernández-Rodríguez R, Suárez-Cárdenas JM, Santos FM, Corrales F, Redondo N, Pedrucci F, Zaldívar-López S, Jiménez-Marín Á, Garrido JJ, Montoya M. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins involvement in inflammatory and profibrotic processes through IL11 signaling. Front Immunol 14:1220306.

- Cao Z, Xia H, Rajsbaum R, Xia X, Wang H, Shi PY. 2021. Ubiquitination of SARS-CoV-2 ORF7a promotes antagonism of interferon response. Cell Mol Immunol. 18(3):746-748.

- Liu Z, Fu Y, Huang Y, Zeng F, Rao J, Xiao X, Sun X, Jin H, Li J, Yang J, Du W, Liu L. 2022. Ubiquitination of SARS-CoV-2 ORF7a Prevents Cell Death Induced by Recruiting BclXL To Activate ER Stress. Microbiol Spectr 10(6):e0150922.

- Hou P, Wang X, Wang H, Wang T, Yu Z, Xu C, Zhao Y, Wang W, Zhao Y, Chu F, Chang H, Zhu H, Lu J, Zhang F, Liang X, Li X, Wang S, Gao Y, He H. 2023. The ORF7a protein of SARS-CoV-2 initiates autophagy and limits autophagosome-lysosome fusion via degradation of SNAP29 to promote virus replication. Autophagy 19:551–569.

- Timilsina U, Umthong S, Ivey EB, Waxman B, Stavrou S. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 ORF7a potently inhibits the antiviral effect of the host factor SERINC5. Nat Commun 13(1):2935.

- Yang R, Zhao Q, Rao J, Zeng F, Yuan S, Ji M, Sun X, Li J, Yang J, Cui J, Jin Z, Liu L, Liu Z. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Accessory Protein ORF7b Mediates Tumor Necrosis Factor-α-Induced Apoptosis in Cells. Front Microbiol 12:654709.

- García-García T, Fernández-Rodríguez R, Redondo N, de Lucas-Rius A, Zaldívar-López S, López-Ayllón BD, Suárez-Cárdenas JM, Jiménez-Marín Á, Montoya M, Garrido JJ. 2022. Impairment of antiviral immune response and disruption of cellular functions by SARS-CoV-2 ORF7a and ORF7b. iScience 25(11):105444.

- Xiao X, Fu Y, You W, Huang C, Zeng F, Gu X, Sun X, Li J, Zhang Q, Du W, Cheng G, Liu Z, Liu L. 2024. Inhibition of the RLR signaling pathway by SARS-CoV-2 ORF7b is mediated by MAVS and abrogated by ORF7b-homologous interfering peptide. J Virol 98(5):e0157323.

- Zhang Y, Chen Y, Li Y, Huang F, Luo B, Yuan Y, Xia B, Ma X, Yang T, Yu F, Liu J, Liu B, Song Z, Chen J, Yan S, Wu L, Pan T, Zhang X, Li R, Huang W, He X, Xiao F, Zhang J, Zhang H. The ORF8 protein of SARS-CoV-2 mediates immune evasion through down-regulating MHC-Ι. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 118(23):e2024202118.

- Beaudoin-Bussières G, Arduini A, Bourassa C, Medjahed H, Gendron-Lepage G, Richard J, Pan Q, Wang Z, Liang C, Finzi A. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Accessory Protein ORF8 Decreases Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity. Viruses 14(6):1237.

- Móvio MI, Almeida GWC de, Martines I das GL, Barros de Lima G, Sasaki SD, Kihara AH, Poole E, Nevels M, Carlan da Silva MC. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 as a Modulator of Cytokine Induction: Evidence and Search for Molecular Mechanisms. Viruses. 16(1):161.

- Kumar J, Dhyani S, Kumar P, Sharma NR, Ganguly S. 2023. SARS-CoV-2–encoded ORF8 protein possesses complement inhibitory properties. J Biol Chem. 299(3):102930.

- Arduini A, Laprise F, Liang C. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 ORF8: A Rapidly Evolving Immune and Viral Modulator in COVID-19. Viruses. 15(4):871.

- Gao X, Zhu K, Qin B, Olieric V, Wang M, Cui S. 2021. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Orf9b in complex with human TOM70 suggests unusual virus-host interactions. Nat Commun 12(1):2843.

- Wu J, Shi Y, Pan X, Wu S, Hou R, Zhang Y, Zhong T, Tang H, Du W, Wang L, Wo J, Mu J, Qiu Y, Yang K, Zhang LK, Ye BC, Qi N. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 ORF9b inhibits RIG-I-MAVS antiviral signaling by interrupting K63-linked ubiquitination of NEMO. Cell Rep 34(7):108761.

- Han L, Zhuang MW, Deng J, Zheng Y, Zhang J, Nan ML, Zhang XJ, Gao C, Wang PH. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 ORF9b antagonizes type I and III interferons by targeting multiple components of the RIG-I/MDA-5–MAVS, TLR3–TRIF, and cGAS–STING signaling pathways. J Med Virol 93:5376–5389.

- Zhang P, Liu Y, Li C, Stine LD, Wang PH, Turnbull MW, Wu H, Liu Q. 2023. Ectopic expression of SARS-CoV-2 S and ORF-9B proteins alters metabolic profiles and impairs contractile function in cardiomyocytes. Front Cell Dev Biol 11:1110271.

- Homma D, Limlingan SJM, Saito T, Ando K. 2024. SARS-CoV-2-derived protein Orf9b enhances MARK2 activity via interaction with the autoinhibitory KA1 domain. FEBS Lett 598(19):2385-2393.

- Sarvari J, Jalili S, Mohammad S, Hashemi A. 2024. SARS-COV-2 ORF9b Dysregulate Fibrinogen and Albumin Genes in a Liver Cell Line. Rep Biochem Mol Biol. 13(1):51-58.

- Li X, Hou P, Ma W, Wang X, Wang H, Yu Z, Chang H, Wang T, Jin S, Wang X, Wang W, Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Xu C, Ma X, Gao Y, He H. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 suppresses the antiviral innate immune response by degrading MAVS through mitophagy. Cell Mol Immunol 19:67–78.

- Han L, Zheng Y, Deng J, Nan ML, Xiao Y, Zhuang MW, Zhang J, Wang W, Gao C, Wang PH. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 antagonizes STING-dependent interferon activation and autophagy. J Med Virol 94:5174–5188.

- Schubert K, Karousis ED, Jomaa A, Scaiola A, Echeverria B, Gurzeler LA, Leibundgut M, Thiel V, Mühlemann O, Ban N. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp1 binds the ribosomal mRNA channel to inhibit translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 27:959–966.

- Korneeva N, Khalil MI, Ghosh I, Fan R, Arnold T, De Benedetti A. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 viral protein Nsp2 stimulates translation under normal and hypoxic conditions. Virol J 20(1):55.

- Thorne LG, Bouhaddou M, Reuschl AK, Zuliani-Alvarez L, Polacco B, Pelin A, Batra J, Whelan MVX, Hosmillo M, Fossati A, Ragazzini R, Jungreis I, Ummadi M, Rojc A, Turner J, Bischof ML, Obernier K, Braberg H, Soucheray M, Richards A, Chen KH, Harjai B, Memon D, Hiatt J, Rosales R, McGovern BL, Jahun A, Fabius JM, White K, Goodfellow IG, Takeuchi Y, Bonfanti P, Shokat K, Jura N, Verba K, Noursadeghi M, Beltrao P, Kellis M, Swaney DL, García-Sastre A, Jolly C, Towers GJ, Krogan NJ. 2022. Evolution of enhanced innate immune evasion by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 602:487–495.

- Takata MA, Gonçalves-Carneiro D, Zang TM, Soll SJ, York A, Blanco-Melo D, Bieniasz PD. 2017. CG dinucleotide suppression enables antiviral defence targeting non-self RNA. Nature 550:124–127.

- Malone B, Urakova N, Snijder EJ, Campbell EA. 2022. Structures and functions of coronavirus replication–transcription complexes and their relevance for SARS-CoV-2 drug design. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23:21–39.

- Hagelauer E, Lotke R, Kmiec D, Hu D, Hohner M, Stopper S, Nchioua R, Kirchhoff F, Sauter D, Schindler M. 2023. Tetherin Restricts SARS-CoV-2 despite the Presence of Multiple Viral Antagonists. Viruses 15:2364.

- Bills C, Xie X, Shi PY. 2023. The multiple roles of nsp6 in the molecular pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. Antiviral Res. 213:105590.

- Krachmarova E, Petkov P, Lilkova E, Ilieva N, Rangelov M, Todorova N, Malinova K, Hristova R, Nacheva G, Gospodinov A, Litov L. 2023. Insights into the SARS-CoV-2 ORF6 Mechanism of Action. Int J Mol Sci 24(14):11589.

- Zheng M, Karki R, Williams EP, Yang D, Fitzpatrick E, Vogel P, Jonsson CB, Kanneganti TD. 2021. TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol 22:829–838.

- Yu H, Yang L, Han Z, Zhou X, Zhang Z, Sun T, Zheng F, Yang J, Guan F, Xie J, Liu C. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein enhances the level of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. J Med Virol 95(12):e29270.

- Kohyama M, Suzuki T, Nakai W, Ono C, Matsuoka S, Iwatani K, Liu Y, Sakai Y, Nakagawa A, Tomii K, Ohmura K, Okada M, Matsuura Y, Ohshima S, Maeda Y, Okamoto T, Arase H. SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 is a viral cytokine regulating immune responses. Int Immunol. 35(1):43-52.

- Fajgenbaum DC, June CH. 2020. Cytokine Storm. New England Journal of Medicine 383:2255–2273.

- Lee MJ, Leong MW, Rustagi A, Beck A, Zeng L, Holmes S, Qi LS, Blish CA. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 escapes direct NK cell killing through Nsp1-mediated downregulation of ligands for NKG2D. Cell Rep 41(13):111892.

- Freda CT, Yin W, Ghebrehiwet B, Rubenstein DA. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Structural Proteins Exposure Alter Thrombotic and Inflammatory Responses in Human Endothelial Cells. Cell Mol Bioeng 15:43–53.

- Lei X, Dong X, Ma R, Wang W, Xiao X, Tian Z, Wang C, Wang Y, Li L, Ren L, Guo F, Zhao Z, Zhou Z, Xiang Z, Wang J. 2020. Activation and evasion of type I interferon responses by SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun 11(1):3810.

- Jeong H. 2023. Ion channels activity of SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein through calcium influx assay using large unilamellar vesicles. Biophys J 122:372a.

- Bugatti A, Filippini F, Bardelli M, Zani A, Chiodelli P, Messali S, Caruso A, Caccuri F. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Infects Human ACE2-Negative Endothelial Cells through an αvβ3 Integrin-Mediated Endocytosis Even in the Presence of Vaccine-Elicited Neutralizing Antibodies. Viruses 14:705.

- Schimmel L, Chew KY, Stocks CJ, Yordanov TE, Essebier P, Kulasinghe A, Monkman J, dos Santos Miggiolaro AFR, Cooper C, de Noronha L, Schroder K, Lagendijk AK, Labzin LI, Short KR, Gordon EJ. 2021. Endothelial cells are not productively infected by SARS-CoV-2. Clin Transl Immunology 10(10):e1350.

- Jiang H wei, Zhang H nan, Meng Q feng, Xie J, Li Y, Chen H, Zheng Y xiao, Wang X ning, Qi H, Zhang J, Wang PH, Han ZG, Tao S ce. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 Orf9b suppresses type I interferon responses by targeting TOM70. Cell Mol Immunol. 17(9):998-1000.

- Gao W, Wang L, Ju X, Zhao S, Li Z, Su M, Xu J, Wang P, Ding Q, Lv G, Zhang W. 2022. The Deubiquitinase USP29 Promotes SARS-CoV-2 Virulence by Preventing Proteasome Degradation of ORF9b. mBio 13(3):e0130022.

- Lenhard S, Gerlich S, Khan A, Rödl S, Bökenkamp JE, Peker E, Zarges C, Faust J, Storchova Z, Räschle M, Riemer J, Herrmann JM. 2023. The Orf9b protein of SARS-CoV-2 modulates mitochondrial protein biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 222(10):e202303002.

- Hirschenberger M, Hayn M, Laliberté A, Koepke L, Kirchhoff F, Sparrer KMJ. 2021. Luciferase reporter assays to monitor interferon signaling modulation by SARS-CoV-2 proteins. STAR Protoc 2(4):100781.

- Baudin B, Bruneel A, Bosselut N, Vaubourdolle M. 2007. A protocol for isolation and culture of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Nat Protoc 2:481–485.

- Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M, Xu J, Obernier K, White KM, O’Meara MJ, Rezelj V V., Guo JZ, Swaney DL, et al.. 2020. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 583:459–468.

- Bouhaddou M, Memon D, Meyer B, White KM, Rezelj V V., Correa Marrero M, Polacco BJ, Melnyk JE, Ulferts S, Kaake RM, et al.. 2020. The Global Phosphorylation Landscape of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cell 182:685-712.e19.

- Vermeire J, Naessens E, Vanderstraeten H, Landi A, Iannucci V, van Nuffel A, Taghon T, Pizzato M, Verhasselt B. 2012. Quantification of Reverse Transcriptase Activity by Real-Time PCR as a Fast and Accurate Method for Titration of HIV, Lenti- and Retroviral Vectors. PLoS One. 7(12):e50859.

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).