Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Significance of the Study

- highlighting the positive effects of AI-driven technology incorporation into this space, to the extent it aids vendor partnerships, supply chain management, and increases the sustainability of the industry, to meet the government’s environmental targets and stipulations;

- bringing awareness into the negative aspects of AI to avoid its pitfalls;

- drawing interrelationship between AI, the CE, sustainability, the IE2W industry and green innovation;

- assessing GoI and state support for AI in the IE2W industry and their impact;

- aligning the IE2W industry and its operations with the added incorporation of AI to enhance the circular economy;

- laying the foundation for research on differing variables like AI-driven technology, human aspect, investment, operations, vis-à-vis IE2W performance;

- creating awareness on IE2W opportunities for AI applications and to find solutions for supply chain challenges therein;

- academia collaboration for R&D on AI-absorption in IEV/ IE2W industry to promote sustainability;

- and, to help watchers of not only IE2W industry but also other industries at large to overcome a range of challenges pertaining to supply chain management, vendor partnerships, innovations, consumer experience, waste management, pollution control, profitability, competitiveness, flexibility, quality etc through suitable application of AI-driven technology, tools and systems.

3. Sources and Classification of Literature

| Type of material | Numbers |

| Journal Article | 415 |

| Report | 44 |

| Book | 25 |

| Conference Paper | 16 |

| Web Page | 12 |

| Newspaper Article | 7 |

| Chapter | 5 |

| Symposium | 5 |

| Magazine Article | 4 |

| Newspaper | 2 |

| Working Paper | 1 |

| Research Paper | 1 |

| Thesis | 1 |

| Grand Total | 538 |

| Year | Material count | Percentage oftotal |

| 2025 | 98 | 18.22 |

| 2024 | 75 | 13.94 |

| 2023 | 79 | 14.68 |

| 2022 | 81 | 15.06 |

| 2021 | 56 | 10.41 |

| 2020 | 40 | 7.43 |

| 2019 | 23 | 4.28 |

| 2018 | 19 | 3.53 |

| 2017 | 14 | 2.60 |

| 2016 & prior | 53 | 9.85 |

| Total | 538 | 100 |

| Subject | Book | Chapter | Conference Paper | Journal Article | Magazine Article | Newspaper | Newspaper Article | Report | Research Paper | Symposium | Thesis | Web Page | Working Paper | Grand Total |

| Adoption, Barriers, Purchase Behaviour & Indian Market | 5 | 49 | 3 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 77 | |||||||

| AI, Blockchain, Industry/Logistics 5.0/4.0 | 3 | 1 | 39 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 55 | ||||||

| Battery Supply Chain | 2 | 1 | 30 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 44 | |||||||

| Bibliometric Analysis | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Charging infrastructure | 2 | 6 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||||

| Circular Economy | 1 | 25 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 37 | |||||||

| Consumer Satisfaction: EVs | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Environment & Sustainability in EVs | 2 | 1 | 2 | 27 | 4 | 1 | 37 | |||||||

| EV Tech & Future Trends | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||

| Geopolitics, Rare minerals | 19 | 3 | 1 | 23 | ||||||||||

| Govt Policy & Economics | 1 | 33 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 38 | ||||||||

| Green Energy | 1 | 21 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 27 | ||||||||

| Green Manufacturing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 9 | |||||||||

| Green SCM | 1 | 1 | 15 | 17 | ||||||||||

| Industry-Academia | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Innovation | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Misc/ Management/ Marketing | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||

| MSME | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Outsourcing in Auto Industry | 9 | 9 | ||||||||||||

| Profitability & Competitiveness | 1 | 17 | 18 | |||||||||||

| Quality in EVs | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Research Methodology | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||

| SCM | 1 | 10 | 11 | |||||||||||

| Skill Development and Training | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Social Aspects of Sustainability | 17 | 17 | ||||||||||||

| SSCM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 36 | 39 | |||||||||

| Top Management | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Vendor Management & Supplier Collaborations | 2 | 38 | 1 | 41 | ||||||||||

| VMI | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Waste Management & Pollution Control | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Grand Total | 25 | 5 | 16 | 415 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 44 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 538 |

4. The IE2W Industry and Sustainability

4.1. How Green Are EVs?

- Raw materials/ minerals used in batteries, like lithium, are dependent on the mining industry which has a negative impact on the environment. The inherent significant geopolitical dynamics also bear mention [31,32,33,34,35]. Boateng & Klopp (2024) explore the transition to EVs with respect to its impact on the mineral supply chain, while Cheng et al. (2024) focus on the emergent problems due to the concentration of rare earths and minerals in selected countries.

- India's LIB storage requirement estimated at 600 GWh from 2021 to 2030 (only 128 GWh recyclable by 2030; only 58-59 GWh from EV; total 349,000 tonnes).

- NITI Aayog (2024) estimates for LIB waste vary from approx. 2 lakh tonnes to 2 million metric tons by 2030, also projecting annual battery retirement of 3-16 GWh from EVs by 2030 [64].

- Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) (2022) projects that approx. 72-81 GWh of waste batteries (447-517000 tons), would be recycled from 2022 to 2030. By 2030, EV batteries will overtake consumer electronics as source of waste [65].

- Other industry reports estimate India's LIB waste from 12,000 (2020) to almost 50,000 metric tons (2025), projecting increase of battery waste 6x by 2040 and 10x by 2050 [66].

4.3. Vendor Management Issues

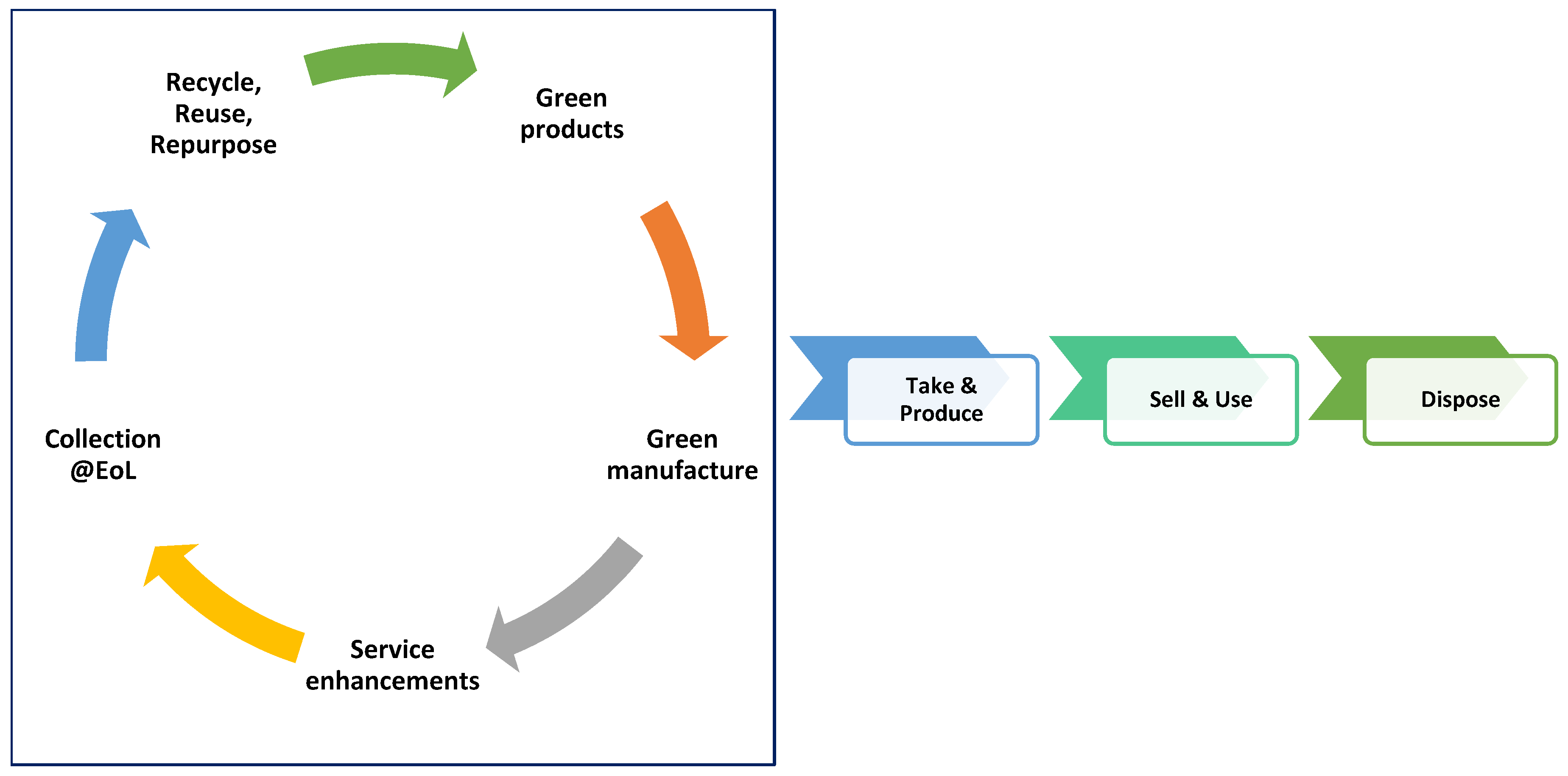

5. The Circular Economy in IE2W

5.1. The Circular Economy (CE)

5.2. Green SCM & Green Manufacturing

5.3. Green Practices of IE2W Companies

5.3.1. Ather Energy

5.3.2. Ola Electric

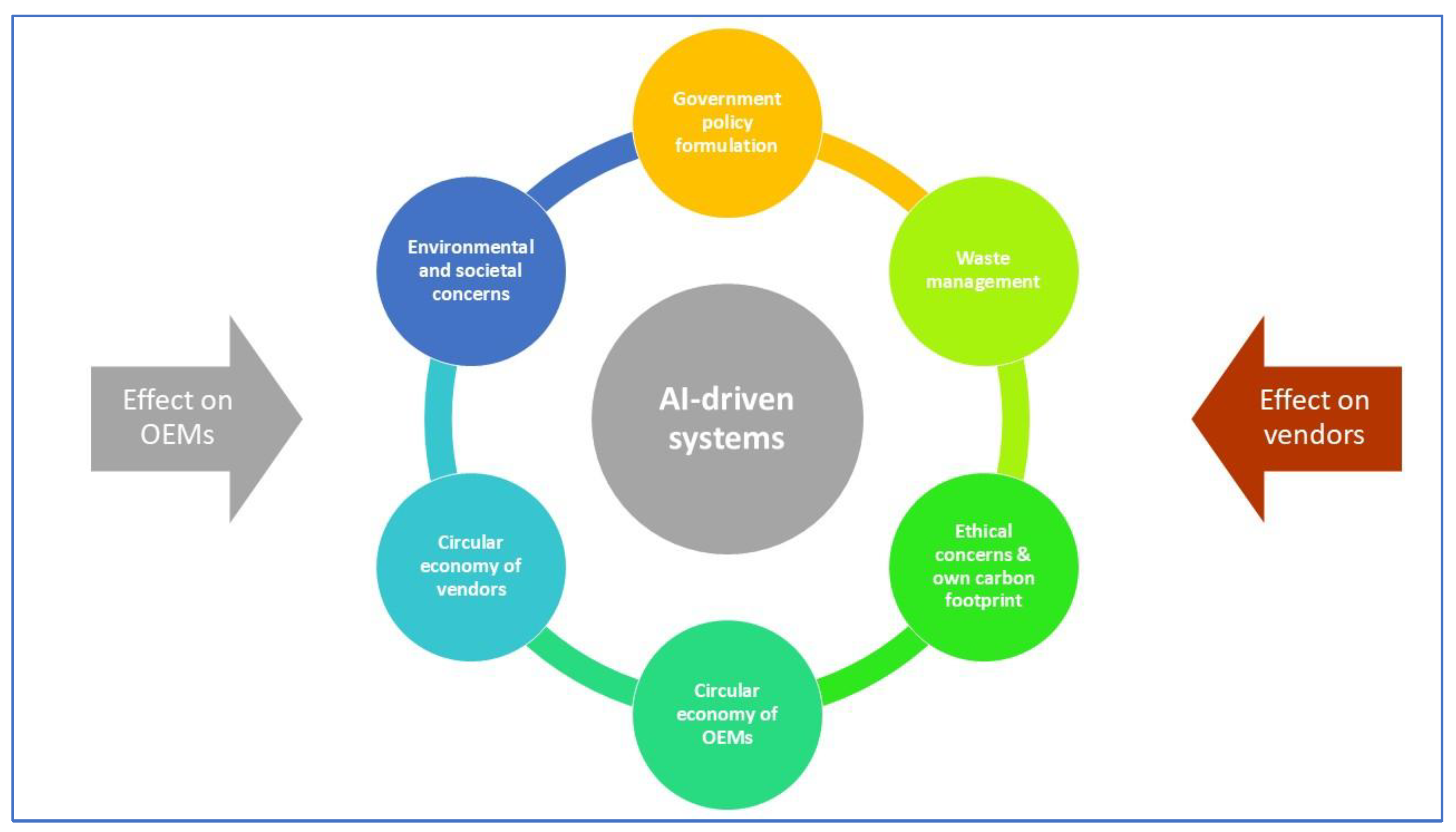

5.4. Interrelationship Between AI and CE/ Sustainability in IE2W Industry

5.5. Role of Government Policies and Regulations

6. AI in the CE of the IE2W industry

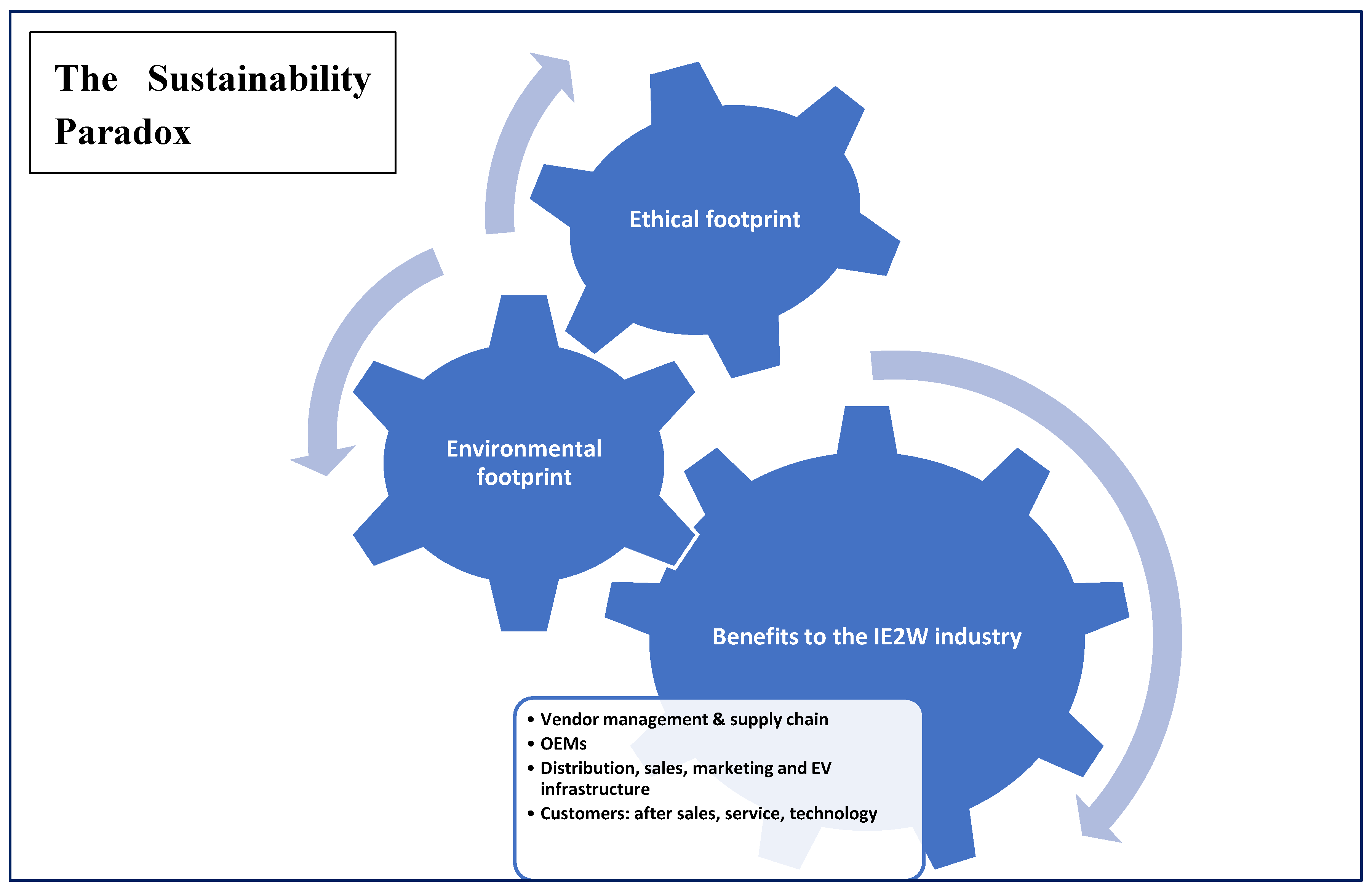

6.1. The Sustainability Paradox: Addressing Environmental and Ethical Footprints of AI

6.1.1. The Environmental Cost of AI

6.1.2. Ethical and Societal Concerns

| AI Risk/ Challenge | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

| Environmental Cost | More carbon emissions, strain on water resources, fossil fuel-based electricity for data centres [142]. | Use of renewable energy sources to power data centres and development of more energy-efficient AI models [142]. |

| Algorithmic Bias | Discriminatory outcomes in financial services, fleet management, and other applications, reinforcing societal biases [143]. | Development of fair LLMs; robust data ethics frameworks and human oversight [143]. |

| Data Privacy & Cybersecurity | Data breaches, unauthorized access, and misuse of personal data collected from vehicles and charging networks [143]. | Implement privacy-by-design principles, strong cybersecurity risk assessment frameworks, and strict regulatory compliance [143]. |

6.2. AI in the EV/IE2W Industry

6.2.1. General Applications

- Supply chain optimization: AI offers solutions to address sustainability bottlenecks in the Indian EV/IE2W industry, creating a more efficient, resilient, and circular value chain. AI-powered supply chain solutions enable manufacturers to forecast parts demand, track inventory, and identify risks, thereby empowering smooth procurement and logistics. Resultantly, there would be lower emissions, reduced waste, and improved lifecycle management for key EV components, enhancing the sustainability of the value chain [154]. The aspects of vendor partnerships like vendor managed inventory (VMI) are also streamlined through AI [155,156].

- Battery management and smart charging: AI-powered battery management systems (BMS) [157,158] offers real-time energy prediction, adaptive charging, and degradation tracking, improving battery life, lowering waste, and reducing total energy consumed by IE2Ws. This can enhance safety and overall performance [158]. Some OEMs and infrastructure providers like Tata Power and Sun Mobility have integrated AI towards battery swapping, smart charging, and lifecycle assessment, improving operational and environmental performance [159]. These will be replicated by the IE2W industry. AI-driven BMSs analyse real-time data from various sensors embedded within the battery pack, including temperature, voltage, and current [160], allowing prediction of the battery's State of Health (SoH) and State of Charge (SoC) with > 95% accuracy [158] and facilitates self-diagnosing maintenance, pre-empting failure [160]. Startups like E-Vega Mobility Labs in India have a portable, AI-powered "EV Doctor" to diagnose battery health in 15 minutes (which earlier took days) [139]. According to McKinsey report, AI-driven systems can extend battery life by up to 30% and decrease maintenance costs by up to 25%, thereby reducing total cost of ownership, premature replacements and waste [160]. Further, AI algorithms optimize energy consumption by analysing driving habits and external environment, enabling efficient power allocation and regenerative braking. Battery-as-a-service (BAAS) is also gaining popularity for the customer as it offers cheaper cost and stress-free ownership [161]. Industry 5.0 concepts, incorporating AI, can also be applied to remanufacturing LIBs to render it more environmentally acceptable [108].

- AI-enabled recycling: EoL batteries pose a significant environmental and economic challenge. The CE model, promoting "5Rs"—Reduce, Reuse, Repurpose, Remanufacture, and Recycle—is critical for risk mitigation [162], which can be helped by AI to manage the transition. "Retired" EV batteries retain 70-80% of their residual capacity, which can be repurposed for large-scale energy storage systems for homes/ businesses [143]. AI health-assessment of these batteries ensures that only components with sufficient functionality are reused, thereby boosting productivity in the "second life" for these batteries [143,163,164]. There have been rapid advances in the use of AI in battery recycling [165], and it is considered that robotics and AI would lead the future of EV recycling [166]. AI is also expected to disrupt the battery supply chain and lifecycle [167]. For batteries that cannot be repurposed, AI-powered automated resource recovery, through advanced multi-sensor technology and X-ray imaging, identifies and classifies each type of battery with >98% accuracy [162], rendering raw material recovery much easier, making it possible for India to meet up to 80% of its domestic lithium and cobalt needs by 2030 (savings of approx. $2 billion a year on imports) and increasing strategic and geopolitical resilience [163].

- Predictive maintenance and manufacturing: IE2W OEMs—especially giants like Ola Electric—deploy AI for predictive maintenance analytics, early defect detection in manufacturing, and supply chain optimization. AI-driven production lines improve yields, lower energy consumption, and minimize waste through digital twins and robotics, supporting the industry’s zero-defect and zero-waste sustainability goals [163].

- Grid integration and demand management: AI optimizes demand management, aligning charging with renewable energy generation, and leverages vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technologies, preventing grid overloads and promoting the use of green energy by automatically shifting charging to off-peak hours ([154].

- Sustainable mobility and user experience: AI-driven route planning apps, over-the-air (OTA) updates, adaptive driver assistance (ADAS), and real-time system diagnostics reduce energy use, boost safety, and improve user experience. Indian cities are already witnessing deployments of AI-enabled public and private EV fleets that adapt to regional grid conditions and mobility patterns to maximize sustainability [168].

- AI for sustainability: AI has been used to optimize supply chain sustainability, by leveraging publicly available Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) data to optimize resource allocation and make a prediction of the carbon emission levels [154].

| AI Application | Mechanism | Sustainability Impact |

| AI-driven BMS | Predictive analytics, ML, NNs, and RL for battery health (SOH) and charge (SOC) predictions. | Extends battery life by up to 30% and reduces maintenance costs by up to 25%, minimizing waste [160]. |

| Battery Repurposing | Data-driven assessment of residual capacity (70-80%) in end-of-life batteries. | Enables second-life applications for grid storage, preventing waste and creating value [143]. |

| Automated Recycling | AI-enabled sorting lines using multi-sensor technology and X-ray imaging for high-purity material classification. | Critical for meeting up to 80% of India's lithium and cobalt needs from recycling by 2030, saving billions in import costs [163]. |

| Fleet & Route Optimization | AI-powered route planning and fleet coordination, especially in urban logistics [169]. | Reduces delivery time by 15-20% and energy consumption by 10-25%, leading to up to a 40% decrease in emissions for last-mile logistics. |

| Smart Charging | Analysis of historical charging patterns, energy consumption, and driver behaviour. | Optimizes charging station locations and manages charging loads to support grid stability and reduce waiting times [170]. |

- Revolutionizing fleet management and urban mobility: The commercial sector is a key driver for EV proliferation and hence a natural fit for AI-powered solutions. For example, Amazon India is surpassing their goal of 10,000 EVs in India a year ahead of schedule [171], thus leveraging AI to optimize operations and reduce carbon footprint [171]. Predictive maintenance allows vehicles to self-diagnose potential issues before they occur, eliminating reliance on periodic manual inspections [172], thus minimizing downtime, maximizing fleet utilization, and ensuring operational efficiency. Indian companies like Bounce Infinity are already deploying these solutions to manage their fleets more effectively [172]. AI is also useful for route optimization and fleet coordination in urban last-mile logistics, with the ability to analyze vast data to dynamically plan routes, reducing delivery time by 15-20%, with a 10-25% gain in energy efficiency, and about 40% reduced emissions [173]. All of these, enhance profitability of firms and contribute to India's climate objectives, while reducing urban pollution and congestion [173]. The success of corporate-led electrification is a significant market dynamic which influences adoption of EVs perhaps more than the government [171] and this will benefit the IE2W industry too in terms of logistics cost savings and efficiencies, apart from being a paradigm worth emulating.

- AI in performance of the IEV/ IE2W industry: AI would have an impact on each parameter which may be used to measure the performance of the IEV/ IE2W industry like profitability [174,175,176], productivity [177], innovation [178], quality [179], flexibility [180,181] and consumer satisfaction [182,183,184,185].

6.2.2. AI in Regulatory and Policy Framing by Government

- Data-driven policy formulation: AI enables policymakers to analyze large-scale, real-time data on material flows, resource use, and environmental impacts, leading to greater accuracy in modelling and data-supported decisions for circular policy development through predictive analytics and scenario simulations [186].

- Adaptive and dynamic regulations: AI can create adaptable regulations that can auto-modify on fresh inputs or situational changes, which make government policies responsive rather than static. This is useful in dynamic domains like materials innovation, waste management, and reverse logistics [187].

- Effective monitoring, compliance, and transparency: Empowers real-time monitoring of supply chains, resource consumption, waste handling etc to assure circularity compliances. This aids transparency while rendering the policies more effective and targeted [188].

- Cross-sectoral collaboration: AI promotes synergy between government, industry, and academia for CE initiatives, by identifying and overcoming systemic inefficiencies. This helps government to scale up pilot projects, digital infrastructure, and skill development programs [186].

- Incentivizing circularity in industry: AI-designed policies can accommodate promotion of economic incentives that encourage investment in circular business models and sustainable technologies [191].

6.2.3. Policies Effective for AI-Driven Circular Economies

- Economic and financial incentives: The economic and financial incentives could be in the form of subsidies and grants to firms to adopt AI-enabled waste management, recycling, and resource efficiency solutions, to help them reduce costs and de-risk innovation [192]. Tax reductions can also be offered to firms who show tangible circularity achievements, through AI-powered resource tracking and predictive maintenance.

- Regulatory frameworks and standards: Data sharing can be mandated with privacy protection of course, enabling government, through AI, to optimize resource flows and enhance traceability [193]. The government could also mandate circularity-related product design standards requiring AI in eco-design, recyclability, and lifecycle optimization [194].

- Digital and physical infrastructure, capacity building and cross-sector collaboration: Public investments in digital infrastructure—like IoT and AI systems—allow for real-time monitoring and automation of materials, products, and energy flow [195,196]. The government can also fund AI applications in waste management, urban mining, and closed-loop supply chains to encourage industry to go in for wider adoption [197]. Integration of AI and CE concepts in curricula and skill development programs enhances availability of local talent and motivates long-term adoption. Government can facilitate multi-stakeholder partnerships and innovation clusters, uniting universities, companies, and startups to co-develop AI-based circular solutions [198].

- Consumer engagement and transparency: Making it mandatory for products and components to be digitally tracked through AI and blockchain, will keep consumers well-informed as a partner in the mutual need for circularity and recyclability [193]. Gamified incentives from government boosts circular behaviour at scale [199].

6.2.4. Policies for AI and Circularity: Snapshots from Other Countries

- European Union: EU's CE Action Plan (CEAP 2020) establishes legal requirements for sustainable product design, right to repair, and digital product passports, with policies promoting AI-enabled resource tracking and eco-design. Netherlands aim for full circularity by 2050, actively investing in AI tools for waste monitoring and materials optimization [98]. Germany’s supports AI innovation hubs that help SMEs adopt digital and AI-driven resource efficiency tools, and funds university-led “Green AI” research that develops resource-efficient AI for circular production [201].

- China: China’s CE Promotion Law (CEPL) carries out AI-based monitoring for resource-use audits, sharing of resources, product life extension measures, and eco-industrial development, supported by tax cuts [194].

- Japan: “Sound Material-Cycle Society” prioritizes AI-powered recycling systems and consumer digital engagement. Over 20% of industrial input comes from recycling, with full government support for holistic circularity, traceability, and automation [194].

- India: India has the National Strategy for AI and CE roadmaps, offering financial incentives for AI adoption in recycling, e-waste management, and resource traceability, alongside policies for cloud computing and IoT-based data solutions in supply chains [193]. Examples include support for startups using AI to optimize supply chain transparency (e.g., ReshaMandi) and investment in public digital infrastructure to enable scalable CE solutions [198].

- Africa (Selected Cases): South Africa supports AI-enabled circular startups, especially in urban mining and plastics recycling, through direct funding, innovation clusters, and knowledge transfer partnerships, but faces challenges of inadequate data infrastructure and skill [202].

- Brazil: Brazil incentivizes producer cooperatives and circular innovations using AI as part of broader waste-to-energy and recycling policy measures.

6.2.5. AI in Waste Management:

- Waste sorting: AI-driven systems considerably improve sorting (plastics, metals, and other materials) accuracy for recyclables, and help to reduce contamination and boost recycling rates vis-à-vis manual sorting [208].

- Smart waste collection: AI in conjunction with IoT sensors predict saturation levels of waste bins and optimize collection routines, thereby reducing fuel consumption, operating costs, and emissions [209].

- Waste data analytics: AI collates and analyses waste generation data to facilitate planning and decision-making in policy, through real-time dashboards with municipal authorities and companies. This also helps to measure performance, and identify recycling loopholes [206].

- Consumer engagement: AI-powered mobile apps encourage sustainable behaviour by informing citizens about waste segregation, collection timings, and incentivizing recycling participation, thereby boosting CE principles at grassroots levels [208]. Countries like India and Kenya tackle growing electronic waste [210] and deploy mobile-first platforms linking households with informal waste collectors for more efficient recycling and reuse [211].

6.2.6. Challenges and Opportunities in Waste Management

- Infrastructure and technical challenges: The inadequacy of extensive IoT networks, sensor technologies, and effective data collection systems necessitated for AI to function effectively in waste management [212]. The availability of waste data is also sporadic and inaccurate which impairs prediction in waste patterns and route-optimisation [206]. The complexity associated with the integration of AI with legacy systems and informal network, is also an issue [209].

- Financial and resource constraints: AI hardware, software, and implementation is expensive for municipalities or waste companies and need hand-holding from the government or other sources [208]. Add to this, the skill gap through the shortage of AI-trained and data science understanding personnel with exposure to waste management [211].

- Social and institutional barriers: Informal waste management agencies are inseparable part of waste collection in developing countries, and their integration into AI-driven systems can be a challenge [206]. Lack of awareness of AI’s benefits in decision-makers and society at large can adversely affect investment and adoption [208]. There is also the issue of having insufficient regulatory frameworks for data governance, privacy, and AI ethics [209].

- Environmental and operational: Uneven waste generation patterns in terms of waste types, volumes, and disposal practices across geographies, complicate AI efficiency [213]. In developing economies, due to financial and institutional shortcomings, the maintenance and adaptation of AI systems may be impacted affecting long-term sustainability [206].

7. Challenges, Opportunities and Recommendations

7.1. Challenges

- Data quality and availability: IEV/ IE2W supply chains and recycling networks as yet do not have access to accurate, comprehensive, and real-time data, which is mandated for the training of AI models. They also lack the desired digital infrastructure and standardization across data sources [214].

- Hunger for resources and negative environmental impact: Large-scale AI models require significant computational power, necessitating high energy consumption and heavy reliance on rare earth metals, thereby negating sustainability gains [191]. There is also presently inadequate infrastructure for systematic collection, storage, transportation, and recycling of EoLEVB, and this process is dominated by the informal sector, which is another issue.

- Linear model bias: Many existing AI solutions may suffer biases arising from the legacy training data which has been obtained from linear (take-make-waste) models. This may prejudice circular production, procurement, and supply chain practices unless the AI systems are retrained appropriately [191].

- Ethical, privacy, and security concerns: AI leads to increased collection and use of supply chain and product usage data which obviously raises privacy, security, and ethical concerns. There is hence a need for robust governance systems for data security as well as to foster consumer trust [141].

- Skill and knowledge gaps: There is lack of training on skills for recycling and CE throughout the battery value chain, from recovery to transportation to testing, recycling, and refurbishment. There is also low consumer awareness on battery environmental and safety risks, leads to improper disposal. There is a shortage of professionals with cross-disciplinary knowledge in AI, CE principles, and EV technology, precluding organization exploitation of AI and implementation of AI-driven circular solutions holistically [216].

- Financial and regulatory barriers: Prohibitive capital costs for recycling plants (between Rs 220-370 crores) adds to the lower penetration and willingness to invest. 18% GST on retired batteries, disincentivizes recycling. Further, there are logistical & data gaps. High capital outlay for AI infrastructure and systems cause problems for smaller firms which are quite prevalent in the IE2W industry [216].

- Complexity of the EV value chain: The complexities involved in IEV/ IE2W parts and multiple vendors imply need for utmost coordination, efficient reverse logistics, and comprehensive adoption of circular practices—by OEMs and all other stakeholders in the value chain [217]. These challenges highlight the need for orientation of AI towards circularity, robust cross-sector collaboration, and supportive governmental frameworks to accrue maximum benefits of AI within the IEV/ IE2W CE models [214].

7.2. Opportunities

- reducing imports LIB (now at 100%);

- recycling to reduce imports of rare earths and minerals to boost geopolitical resilienc. (recent discovery of lithium reserves in India further offers long-term promise for domestic supply) [218];

- battery recycling (market estimated at $ 95 billion annually by 2040) to recover 50-95% [219], to boost profitability, economic viability and job creation (total LIB recycling market in India by 2030 is estimated at $ 11 billion);

- address environmental concerns and lower carbon emissions by up to 90%;

- exploitation of AI and other technological advances and green innovation;

- and, collaborative efforts on CE between lawmakers, automakers, vendors, battery manufacturers, recyclers, and academia.

7.3. Recommendations for Government/ Academia

- Local R&D and human capital: Policymakers should align their efforts with initiatives like "AI for India 2030" and the NITI Aayog report's recommendations [160], by incentivizing investments in local R&D for both EV technology and ethical AI. This would reduce dependency on imported technology and help the country become a global innovation leader.

- Bridge the skill gap: Universities and industry must come together to create tailor-made curricula focused on the synergies of the IEV/ IE2W and AI technologies, moving beyond traditional automotive engineering [221]. These programs can produce world-class specialists in BMS, embedded electronics, and data analytics [174].

- Robust regulatory frameworks: To promote AI transparency, mitigate algorithmic bias, and ensure data privacy within the EV ecosystem [139,140]. Other regulatory and policy initiatives through refining of BWMR implementation, standardizing the battery design, implementing a battery tracking system, addressing disincentives, and facilitating second-use of batteries.

- Infrastructure through Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): Government can accelerate growth of infrastructure through PPPs, in the EV field by significantly increasing the number of charging stations, and by aligning energy policy with EV adoption by using renewable energy sources for grid power [169]. Government also has a role to play in infrastructure and technology investments along with the industry. India continues to face barriers such as infrastructure bottlenecks, policy fragmentation, and cost pressures in localizing advanced AI solutions [215]. Coordinated PPP investment in AI R&D, government incentives for digital infrastructure, and targeted training (e.g., through NITI Aayog, IITs) can help overcome these hurdles and revolutionise sustainable scaling [215,222].

- Foster public awareness: Improving public awareness and participation through cross-sectoral alignment between policymakers, IE2W industry, vendors, academia, and local bodies, will highlight EV benefits and build support for the transition [113], apart from understanding the importance of correct battery disposal. This will also address potential resistance from established industries to ensure that societal transition is as smooth as the technological one.

- Ethical AI deployment: To build consumer confidence, government must regulate to ensure that companies implement robust data ethics frameworks and privacy-by-design principles [139].

7.4. Recommendations for the IE2W Industry

- Invest in a CE: It is important for IE2W industries to incentivize R&D and training, factoring AI into their core business strategy, from product design to supply chain management. This includes in-house capabilities for battery health diagnostics and investing in automated recycling technologies. By integrating these processes, manufacturers can reduce their reliance on imports of critical minerals and create profitable avenues from second-life applications and material recovery [143]. IE2W industry should establish an efficient reverse logistics system [53,223], standardized battery labelling, and effective battery tracking.

- Public awareness: IE2W industry can launch awareness campaigns to address public concerns on AI ethical deployment in the products and services, their technological advances and benefits, to remove misconceptions and biases to build support for the transition [113].

- Embrace ethical AI deployment: To build consumer confidence, companies must implement robust data ethics frameworks and privacy-by-design principles to promote transparency in AI deployment [139].

- Prioritize a fleet-first adoption model: Industry leaders should recognize the power of corporate-led fleet electrification as a key accelerator of market growth apart from AI-driven advancements in boosting sustainability in the IE2W industry and strengthening the supply chain, like Amazon [171]. This approach is economically driven and can provide a proof of concept for wider adoption, by the IE2W industry.

8. Gaps in Literature

- need for study specific to the application of AI to the CE of the IEV/ IE2W sector rather than generic to the automobile sector or industry;

- need to study specific effects of AI on environmental aspects of IEV/ IE2W industry to include waste management, pollution control, environmental impact of OEMs and actual environmental impact of their products;

- need for study specific to examining existing government policy framing mechanism, impact of AI in this, especially for policy pertaining to the IEV/ IE2W industry;

- need to research impact of AI on job creation or loss of jobs in the IEV/ IE2W industry;

- need to research impact of AI on R&D to the extent it meets the requirement of decreased dependence on lithium, a basic raw material for batteries, impacting the overall logistics and supply chain;

- need to research differences in the AI applications in the automobile ICE industries vis-à-vis IEV/ IE2W industry;

- need to research differences between AI applications in the vendor partnerships and supply chain management in automobile ICE industries vis-à-vis IEV/ IE2W industry;

- need to study specific effects of AI on the parameters of profit, innovation, flexibility, quality control, and consumer delight in the IEV/ IE2W industry;

- need for India-specific study on application of AI to the IE2W industry to study not only the benefits but also the pitfalls of AI and how and by whom these could be countered;

- need for study on the AI impacts on vendor partnerships and sustainable supply chain for the IEV/ IE2W sector;

- and, the need to focus investigation to a particular type of industry for consistency in results, which here, is the IE2W industry.

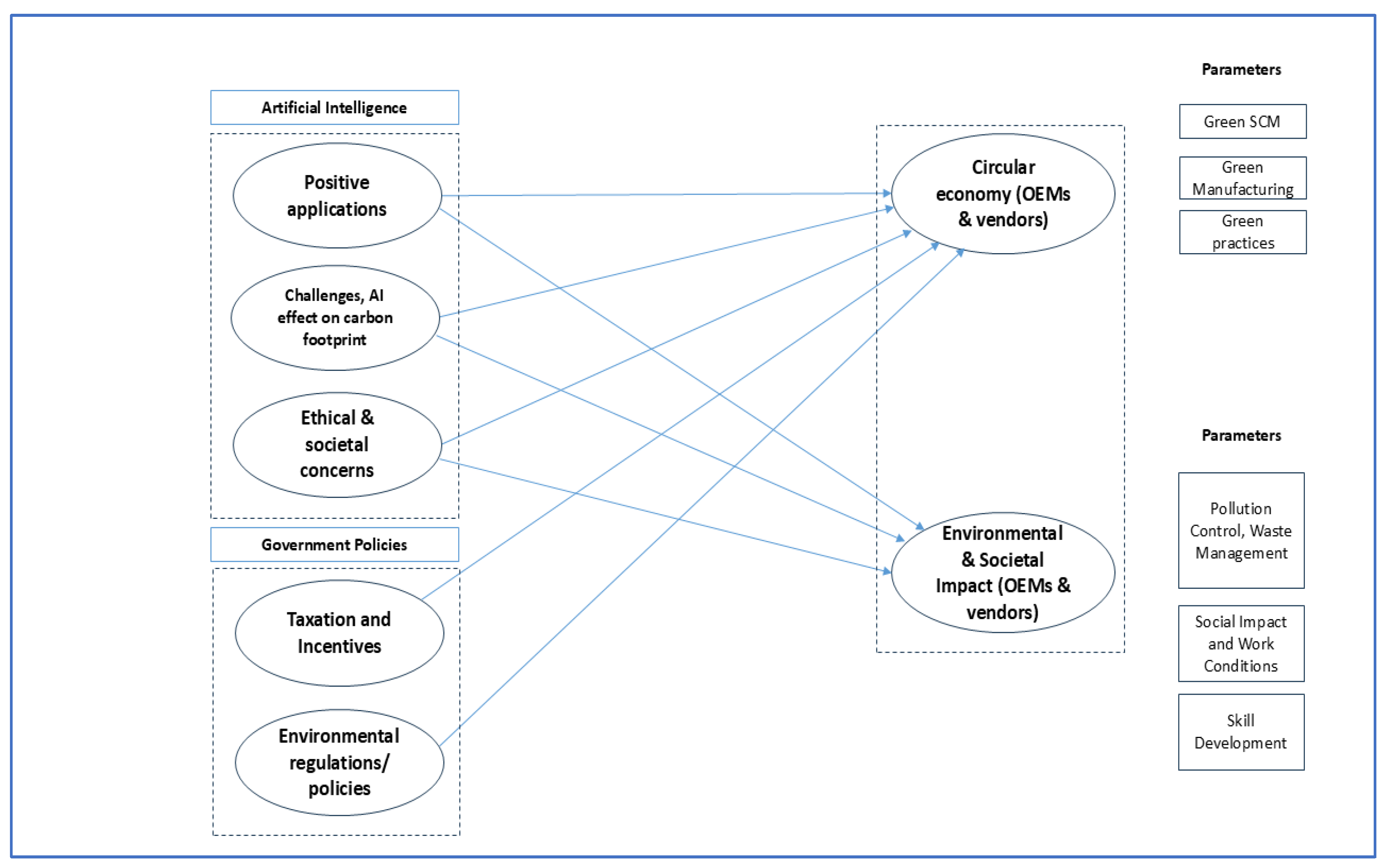

9. A Conceptual Framework

10. Scope for Research and Potential

10.1. Limitations of Study

10.2. Discussions

10.2.1. Theoretical

- AI enables the CE: AI facilitates product design which empowers circularity, ensures resource optimization, and facilitates decision-making using predictive analytics and tools [224].

- Sustainability in manufacturing: Deployment of AI in EV/ E2W manufacturing cuts waste, reduces carbon footprints, and advances life of products through predictive maintenance, efficient use of energy, and streamlining the supply chain [199].

- Frameworks across disciplines: When a conceptual model is devised, which combines green and sustainable manufacturing, digitalization, and circular supply chains, it demonstrates the synergy between business, technology, policy, and societal factors, which further boosts the transition towards sustainability [225].

- Data-driven innovation: AI encompasses data collation, real-time monitoring, and simulation of environmental as well as economic impact to ensure a dynamically improving circularity for the business model [226].

- Acting upon circular strategies: This can be done by managers by leveraging AI tools to ensure circularity in the supply chain through the planned recovery, reallocation, refurbishment, sale, and disassembling of EV components, in a smooth manner [231].

- Resource optimisation and waste reduction: AI-driven solutions can be used to optimize material flow, facilitate sorting through visual recognition, and ensure effective energy management towards sustainability in resource use [232].

- Supply chain collaboration and transparency: AI facilitates real-time data sharing, stakeholders’ collaboration, and adaptive decision-making across multiple circular levels including recycling agencies, logisticians, repair and maintenance services and the OEMs [152].

- Strategic sustainability initiatives: Managers can employ AI analytics to simulate situations, forecast market developments, predict demand, and adapt circularity in their business models to enhance the profitability and competitiveness while simultaneously meeting the obligations of government regulations and environmental norms [233].

- Ethical considerations: Effective managers will not ignore the sensitivities of data security, interoperability, skill gaps, and ethical design even as they fully exploit all that AI is capable of in the quest for sustainability [199].

11. Summary

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2W | Two-wheelers |

| 3W | Three-wheelers |

| 4W | Four-wheelers/ cars |

| 5Rs | Reduce, reuse, repurpose, remanufacture, and recycle |

| ADAS | Adaptive driver assistance system |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BMS | Battery management system |

| BWMR | Battery waste management rules |

| CAGR | Compounded annual growth rate |

| CDP | Carbon disclosure project |

| CE | Circular economy |

| CEPL | China’s CE promotion law |

| CII | Confederation of Indian Industry |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| DPIIT | Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade |

| E2W | Electric two-wheelers |

| EoL | End-of-Life |

| EPR | Extended producer liability |

| EoLEVB | End-of-Life EV Batteries |

| EU | European Union |

| EV | Electric vehicles |

| FAME | Faster adoption and manufacture of hybrid and electric vehicles scheme |

| GPUs | Graphics processing units |

| GSCM | Green supply chain management |

| GST | Goods and Services Tax |

| ICE | Internal combustion engines |

| IEV | Indian Electric Vehicles (industry) |

| IE2W | Indian EV two-wheelers |

| IIT | Indian Institute of Technology |

| IoT | Internet of things |

| IR5.0 | 5th industrial revolution |

| KTPA | Kilotons per annum |

| LIB | Lithium-ion battery |

| LLM | Language learning model (in AI) |

| MoU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| MSME | Medium, small & micro enterprises |

| OEM | Original equipment manufacturer |

| OTA | Over-the-air (as in updates given to EVs) |

| PPP | Public-private partnerships |

| PLI | Productivity linked incentive (scheme) |

| R&D | Research & development |

| SoC | State of charge |

| SoH | State of health |

| SSCM | Sustainable supply chain management |

| US | United States |

| V2G | vehicle-to-grid technologies |

| VMI | Vendor managed inventory |

References

- India two Wheelers Go Electric-Setting Stage for the E-Revolution. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 751–756. [CrossRef]

- Cornet, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Why the automotive future is electric,” Sep. 2021.

- P. C. Pandey, “India Imports 82% of Its Oil Needs and Aims to Reach 67% By 2022,” Climate Scorecard.

- British Petroleum, “Statistical Review of World Energy,” 2020.

- S. Sharma, “India’s oil import dependency on course to hit fresh full-year high in FY25 amid growing demand, stagnant domestic production,” The Hindu, Chennai, Mar. 22, 2025.

- R. R. Kala, “India’s crude oil import dependence rises to record 90%,” Business Line, Chennai, , 2025. 21 May.

- Dua, R.; Almutairi, S.; Bansal, P. Emerging energy economics and policy research priorities for enabling the electric vehicle sector. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 1836–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAB, “FAME II,” National Mission for Electric Mobility. Accessed: Feb. 11, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://fame2.heavyindustries.gov.in/content/english/1_1_AboutUs.

- R. Dhawan, S. R. Dhawan, S. Gupta, R. Hensley, N. Huddar, B. Iyer, and R. Mangaleswaran, “The future of mobility in India: Challenges & opportunities for the auto component industry,” Sep. 2017.

- Khurana, A.; Kumar, V.V.R.; Sidhpuria, M. A Study on the Adoption of Electric Vehicles in India: The Mediating Role of Attitude. Vision: J. Bus. Perspect. 2019, 24, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor Intelligence, “India Electric Vehicle Market - focusing on market growth, industry analysis, size, and forecast up to 2030,” Jan. 2025.

- M. S. Khande, A. S. M. S. Khande, A. S. Patil, G. C. Andhale, and R. S. Shirsat, “Design and Development of Electric Scooter,” International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET), vol. 7, no. 5, 20. 20 May.

- C. Jacob, “India is learning to love electric vehicles — but they’re not cars,” cnbc.com.

- Dhaked, D.K.; Birla, D. Microgrid Designing for Electrical Two-Wheeler Charging Station Supported by Solar PV and Fuel Cell. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 14, 2517–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Norikun, “The Importance of Government Policy in Influencing the Increase in Purchasing Interest Electric Vehicles,” International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation, vol. 6, no. 2, Mar. 2025.

- Hales, D.N.; Yun, G.; Kale, D. The Efficacy of India's Electric Vehicle Market: Can FAME Deliver Results? Mark. Glob. Dev. Rev. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Malhotra, G. Is India Ready for e-Mobility? An Exploratory Study to Understand e-Vehicles Purchase Intention. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2019, 09, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, U.; Kumar, A.; Chakrabarti, D. Barriers in implementation of electric vehicles in India. Int. J. Electr. Hybrid Veh. 2019, 11, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Broom, “6 of the world’s 10 most polluted cities are in India,” World Economic Forum.

- ANI, “India tops Japan to become world’s 3rd largest auto market,” Fortune India, Jan. 09, 2023.

- SIAM, “SIAM Annual Report 2023-24,” New Delhi, 2024.

- Paladugula, A.L.; Kholod, N.; Chaturvedi, V.; Ghosh, P.P.; Pal, S.; Clarke, L.; Evans, M.; Kyle, P.; Koti, P.N.; Parikh, K.; et al. A multi-model assessment of energy and emissions for India's transportation sector through 2050. Energy Policy 2018, 116, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Kockelman, K.M.; Schievelbein, W.; Schauer-West, S. Indian vehicle ownership and travel behavior: A case study of Bengaluru, Delhi and Kolkata. Res. Transp. Econ. 2018, 71, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpure, A.S.; Gurjar, B. Development and evaluation of Vehicular Air Pollution Inventory model. Atmospheric Environ. 2012, 59, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, L. Powell, and V. K. Tomar, “Road emission control: Electrifying personal mobility in India,” Observer Research Foundation, Oct. 2021.

- Dhairiyasamy, R.; Gabiriel, D. Sustainable mobility in India: advancing domestic production in the electric vehicle sector. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Dou, X. Application of sustainable supply chain finance in end-of-life electric vehicle battery management: a literature review. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022, 34, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, D.; Sangwan, P.; Dahiya, N. Economic Analysis of Lithium Ion Battery Recycling in India. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2022, 124, 3263–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaeifar, M.A.; Ghadimi, P.; Raugei, M.; Wu, Y.; Heidrich, O. Challenges and recent developments in supply and value chains of electric vehicle batteries: A sustainability perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M.; Sohrabi, M.; Rezaei, H.; Sorooshian, S.; Mina, H. A sustainable circular supply chain network design model for electric vehicle battery production using internet of things and big data. Expert Syst. 2023, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, M. A Perspective on the Battery Value Chain and the Future of Battery Electric Vehicles. Batter. Energy 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.D.; Rupp, J.A.; Brungard, E. Lithium in the Green Energy Transition: The Quest for Both Sustainability and Security. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, R. Mining our green future. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, B.E.; Toghill, K.E.; Tapia-Ruiz, N. A Perspective on the Sustainability of Cathode Materials used in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn and, E. Lipton, “The Lithium Gold Rush: Inside the Race to Power Electric Vehicles,” The New York Times, , 2021. 06 May.

- Boateng, F.G.; Klopp, J.M. The electric vehicle transition: A blessing or a curse for improving extractive industries and mineral supply chains? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.L.; Fuchs, E.R.H.; Karplus, V.J.; Michalek, J.J. Electric vehicle battery chemistry affects supply chain disruption vulnerabilities. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, W.-P.; Gerbaulet, C. Power system impacts of electric vehicles in Germany: Charging with coal or renewables? Appl. Energy 2015, 156, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, T.; Papageorgiou, D.J.; Harper, M.R.; Rajagopalan, S.; Rudnick, I.; Botterud, A. From coal to variable renewables: Impact of flexible electric vehicle charging on the future Indian electricity sector. Energy 2022, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Haitao, “Implementation of a Green Economy: Coal Industry, Electric Vehicles, and Tourism in Indonesia,” Dinasti International Journal of Economics, Finance & Accounting, no. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Gautam, S.; Malik, P.; Kumar, S.; Krishnan, C. A multi-phase qualitative study on consumers’ barriers and drivers of electric vehicle use in India: Policy implications. Energy Policy 2024, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dr. M. Jagtap and Dr. S. Alvi, “Deciphering Customer Purchase Priorities: Insights from Two-Wheeler Dealer Managers In Pune,” International Journal of Research in Management & Social Science, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 67–75, Apr. 2023.

- Digalwar, A.K.; Saraswat, S.; Rastogi, A.; Thomas, R.G. A comprehensive framework for analysis and evaluation of factors responsible for sustainable growth of electric vehicles in India. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatasatish, R.; Dhanamjayulu, C. Reinforcement learning based energy management systems and hydrogen refuelling stations for fuel cell electric vehicles: An overview. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 27646–27670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOI, “Can battery recycling solve EV industry’s growing e-waste problem?,” Times of India, New Delhi, , 2025. 30 May.

- Asokan, V.A.; Teah, H.Y.; Kawazu, E.; Hotta, Y. Ambitious EV policy expedites the e-waste and socio-environmental impacts in India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shankar and S. Rachakonda, “Investing in the waste and circularity sector in India - E-Waste and Lithium-ion Battery Recycling Guide,” 2024.

- Lee, J.; Choe, H.; Yoon, H.-Y. Past trends and future directions for circular economy in electric vehicle waste battery reuse and recycling: A bibliometric analysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2025, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopha, B.M.; Purnamasari, D.M.; Ma’mun, S. Barriers and Enablers of Circular Economy Implementation for Electric-Vehicle Batteries: From Systematic Literature Review to Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, J.; Domenech, T.; Bleischwitz, R.; Melin, H.E.; Heidrich, O. Circular economy strategies for electric vehicle batteries reduce reliance on raw materials. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 4, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatise, O.; Wu, R.; Deb, A.; Gonzalez, J.O. Second life potential of electric vehicle power electronics for more circular economies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroozi, M.A.; Gramifar, M.; Hazratifar, B.; Keshvari, M.M.; Razavian, S.B. Optimization of Lithium-Ion Battery Circular Economy in Electric Vehicles in Sustainable Supply Chain. Batter. Energy 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamerew, Y.A.; Brissaud, D. Modelling reverse supply chain through system dynamics for realizing the transition towards the circular economy: A case study on electric vehicle batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Jha, “Lithium Ion Battery Recycling in India - Need to build local refining capabilities to curb black mass export,” EV Reporter, Nov. 08, 2023. Accessed: Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.teriin.

- M. Gupta, “Building India’s Battery Circular Economy: Strategies For Sustainable Recycling And Second-Life Solutions – Report,” E-Mobility Plus, Jul. 2025, Accessed: Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://emobilityplus. 2025.

- U. Gupta, “Tata Chemicals launches Li-ion battery recycling operations,” PV Magazine, Sep. 02, 2019.

- TeamET, “Attero to set up lithium-ion battery recycling plant in Telangana,” The Economic Times, Nov. 03, 2022.

- Soman, K. Ganesan, and H. Kaur, “India’s Electric Vehicle Transition,” 2019.

- U. Gupta, “BatX Energies raises $1.6 million to expand battery recycling,” PV Magazine, Jun. 2022.

- CPCB, “Battery Waste Management Rules,” Central Pollution Control Board. Accessed: Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://cpcb.nic.

- J. Fleischmann, M. J. Fleischmann, M. Hanicke, and E. H, “Battery 2030: Resilient, sustainable, and circular,” McKinsey & Company. Accessed: Aug. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mckinsey. 2030. [Google Scholar]

- CEEW, “Lithium-ion battery waste recycling,” Jan. 2025.

- Gattu, A. Agrawal, and R. Bagdia, “Advanced Chemistry Cell Battery Reuse and Recycling Market in India,” New Delhi, 22. 20 May.

- Lico, “How EV Battery Recycling Will Shape Sustainable Mobility in India,” Licomat. Accessed: Aug. 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://licomat.

- CII, “Around 72 - 81 GWh of waste batteries (~447 – 517 thousand tons) would reach recycling firms from 2022 to 2030,” Aug. 2023. Accessed: Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.cii.in/PressreleasesDetail.aspx?

- P. Singh, “Advancing Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling in India Through Technological Innovations Economic Feasibility and Policy-Driven Sustainability,” International Journal of Innovative Research in Electrical, Electronics, Instrumentation and Control Engineering, vol. 13, no. 2, Feb. 2025.

- A. Jamwal, A. Patidar, R. Agrawal, M. Sharma, and V. K. Manupati, “Analysis of Barriers in Sustainable Supply Chain Management for Indian Automobile Industries,” in Recent Advances in Industrial Production, ICEM 2020., R. Agrawal, J. K. Jain, V. S. Yadav, V. K. Manupati, and L. Varela, Eds., Singapore: Springer, 2022, pp. 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Aruleswaran, A.; Muraliraj, J.; Zailani, S. Lean six sigma and sustainable supply chain management: a case study in electric vehicle parts manufacturing. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Haleem, A. Hurdles in Implementing Sustainable Supply Chain Management: An Analysis of Indian Automobile Sector. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 189, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuchogu, M.C.; Sanyaolu, T.O.; Adeleke, A.G. Exploring sustainable and efficient supply chains innovative models for electric vehicle parts distribution. Glob. J. Res. Sci. Technol. 2024, 2, 078–085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Obiuto Nwankwo and E. A. Etukudoh, “Exploring Sustainable and Efficient Supply Chains Innovative Models for Electric Vehicle Parts Distribution,” International Journal of Advanced Multidisciplinary Research and Studies, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 238–243, 2024.

- Mathivathanan, D.; Kannan, D.; Haq, A.N. Sustainable supply chain management practices in Indian automotive industry: A multi-stakeholder view. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathivathanan, D.; Agarwal, V.; Mathiyazhagan, K.; Saikouk, T.; Appolloni, A. Modeling the pressures for sustainability adoption in the Indian automotive context. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bangwal, D. An assessment of sustainable supply chain initiatives in Indian automobile industry using PPS method. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 9703–9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, P.; Thakkar, J. Sustainable supply chain practices: an empirical investigation on Indian automobile industry. Prod. Plan. Control 2016, 27, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, H.; Mukherjee, A.; Gunasekaran, A.; Singh, R.K. Sustainable supply chain management of automotive sector in context to the circular economy: A strategic framework. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 3635–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niri, A.J.; Poelzer, G.A.; Zhang, S.E.; Rosenkranz, J.; Pettersson, M.; Ghorbani, Y. Sustainability challenges throughout the electric vehicle battery value chain. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kolasani, “Revitalizing Mobility: Understanding the Supply Chain Challenges, Opportunities, strategies, and Resilience in the EV and Automotive Revolution,” International Journal of Creative Research in Computer Technology and Design, vol. 6, no. 6, 2024.

- Lehtimäki, H.; Karhu, M.; Kotilainen, J.M.; Sairinen, R.; Jokilaakso, A.; Lassi, U.; Huttunen-Saarivirta, E. Sustainability of the use of critical raw materials in electric vehicle batteries: A transdisciplinary review. Environ. Challenges 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernova, O.A.; Liu, L.; Wang, X. Role of digitalization of logistics outsourcing in sustainable development of automotive industry in China. R-Economy 2023, 9, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, E.; Bui, Q. “.; Adelakun, O. Outsourcing for Sustainable Performance: Insights from Two Studies on Achieving Innovation through Information Technology and Business Process Outsourcing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Ciarapica, F.E.; De Sanctis, I. Lean practices implementation and their relationships with operational responsiveness and company performance: an Italian study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 55, 769–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciravegna, L.; Romano, P.; Pilkington, A. Outsourcing practices in automotive supply networks: an exploratory study of full service vehicle suppliers. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 2478–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacity, M.; Willcocks, L. Outsourcing Business and I.T. Services: the Evidence of Success, Robust Practices and Contractual Challenges. Leg. Inf. Manag. 2012, 12, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIvor, R. How the transaction cost and resource-based theories of the firm inform outsourcing evaluation. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 27, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, S.; Stern, S. How Does Outsourcing Affect Performance Dynamics? Evidence from the Automobile Industry. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1963–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Lopes, P.; Rosário, F.S. Sustainability and the Circular Economy Business Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Clifton, N.; Faqdani, H.; Li, S.; Walpole, G. Implementing circular economy principles: evidence from multiple cases. Prod. Plan. Control. 2024, 36, 1774–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Stahel, The Performance Economy, 2nd ed. Springer, 2010.

- J. M. Benyus, Innovation Inspired by Nature. Harper Perennial, 2002.

- K. E. Boulding, “The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth,” in Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy, 1st ed., Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2011.

- G. Pauli, The Blue Economy 3.0: The Marriage of Science, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Creates a New Business Model That Transforms Society. Xlibris Corporation, 2017.

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyani, D.; Hariyani, P.; Mishra, S.; Sharma, M.K. Leveraging digital technologies for advancing circular economy practices and enhancing life cycle analysis: A systematic literature review. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Hope, “How countries are striving to build their circular economy,” Sustainability Magazine.

- Hwang, B.; Puntha, P.; Jitanugoon, S. AI-Driven Circular Transformation: Unlocking Sustainable Startup Success Through Co-Creation Dynamics in Circular Economy Ecosystems. Sustain. Dev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobanaa, M.; Prathiviraj, R.; Prathaban, M.; Kiran, G.S.; Selvin, J. Closing the Loop: Circular economy solutions for long-term environmental health. Evol. Earth 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. W. A. de Moor, “Circular Strategies and Resource Preservation in the Solar Photovoltaics (PV) Industry in the Netherlands,” Utrecht University, Utrecht, 2025.

- Yamini, E.; Khazaei, H.; Soltani, M.; Alfraidi, W.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L. Emerging technologies in renewable energy: Risk analysis and major investment strategies. Sustain. Futur. 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matosović, M.D.; Cerović, L. Drivers of sustainability: Economic vs. Environmental priorities in SDG performance. Sustain. Futur. 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Jiandong, W.; Saleem, H. The impact of renewable energy transition, green growth, green trade and green innovation on environmental quality: Evidence from top 10 green future countries. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Ekins, T. Domenech Aparisi, P. Drummond, N. Hughes, L. Lotti, and R. Bleischwitz, “The Circular Economy: What, Why, How and Where,” UCL Discovery, 2020.

- M. M. C. Fritz, “Sustainable Supply Chain Management,” in Responsible Consumption and Production, Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, W. L. Filho, Ed., Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019, 2019, pp. 1–14. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71062-4_21-1.

- Balakrishnan, A.; Suresh, J. Green supply chain management in Indian automotive sector. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2018, 29, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheorey, P.; Gandhi, A. Antecedents of green consumer behaviour: a study of consumers in a developing country like India. Int. J. Public Sect. Perform. Manag. 2019, 5, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehurst, G.; Afonso, C.; Gonçalves, H.M. Re-examining green purchase behaviour and the green consumer profile: new evidences. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Srai, J.S.; Evans, S. Environmental management: the role of supply chain capabilities in the auto sector. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2016, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedam, V.V.; Raut, R.D.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S.; Narkhede, B.E.; Grebinevych, O. Sustainable manufacturing and green human resources: Critical success factors in the automotive sector. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 30, 1296–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezen, B.; Çankaya, S.Y. Effects of Green Manufacturing and Eco-innovation on Sustainability Performance. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Garg, D.; Haleem, A. Empirical Analysis of Green Supply Chain Management Practices in Indian Automobile Industry. J. Inst. Eng. (India): Ser. C 2014, 95, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Naim, A. Muniasamy, A. Clementking, and R. Rajkumar, “Relevance of Green Manufacturing and IoT in Industrial Transformation and Marketing Management,” 2022, pp. 395–419. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-96429-0_19.

- Das, P.K.; Bhat, M.Y. Global electric vehicle adoption: implementation and policy implications for India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 40612–40622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Kumar, R.R.; Chakraborty, A.; Mateen, A.; Narayanamurthy, G. Design and selection of government policies for electric vehicles adoption: A global perspective. Transp. Res. Part E: Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.; Tong, S. Green Supply Chain Management Practices of Firms with Competitive Strategic Alliances—A Study of the Automobile Industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Mandal, M.C.; Ray, A. Strategic sourcing model for green supply chain management: an insight into automobile manufacturing units in India. Benchmarking: Int. J. 2021, 29, 3097–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Vijayvargy, L. Selection of Green Supplier in Automotive Industry: An Expert Choice Methodology.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 012036.

- Li, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, T.; Liu, L.; Yuan, J. The impact of internal and external green supply chain management activities on performance improvement: evidence from the automobile industry. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, G.M.; Carrillo, E.P.M.; Castro, S.Y.P. Green supply chain management and firm performance in the automotive industry. 34. [CrossRef]

- Jin, B. Research on performance evaluation of green supply chain of automobile enterprises under the background of carbon peak and carbon neutralization. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A.; Mogale, D.; Bourlakis, M.; Maiyar, L.M.; Moradlou, H. Link between Industry 4.0 and green supply chain management: Evidence from the automotive industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islamic Azad University; Einizadeh, A. ; Kasraei, A. Proposing a Model of Green Supply Chain Management Based on New Product Development (NPD) in Auto Industry. J. Econ. Manag. Res. 2022, 10, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlot, N.; Bagri, G.; Gulati, B.; Bhatia, L.; Barat, S.; Das, S. Analysis of barriers to implement green supply chain management practices in Indian automotive industries with the help of ISM model. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023, 82, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PTI, “DPIIT signs pact with Ather Energy to strengthen EV manufacturing,” The Economic Times, Jul. 29, 2025. Accessed: Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/renewables/dpiit-signs-pact-with-ather-energy-to-strengthen-ev-manufacturing/articleshow/122967195.cms?

- B. Seth, “Ather Energy Share Price Gains as Company Signs MoU to Boost EV Ecosystem,” Samco Trading App. Accessed: Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.samco.

- M. Toll, “This carbon-negative massive megafactory will produce an EV every 2 seconds,” Electrek. Accessed: Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://electrek. 2021.

- TeamET, “Ola Electric doubles down on rare earth-free motors to sidestep China curbs,” The Economic Times, Jul. 14, 2025. Accessed: Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/startups/ola-electric-doubles-down-on-rare-earth-free-motors-to-sidestep-china-curbs/articleshow/122432305.cms?

- V. Srinivasan, “Ola’s Future Factory to be Carbon Negative,” Sustainability Next, no. 83, Mar. 2021.

- P. Kumar, M. P. Kumar, M. Sahoo, A. Meshram, and L. Mudholkar, “Battery circularity in India: Policy, regulations, and implementation strategies,” in WRI India, Jul. 2024.

- Mekky, M.F.; Collins, A.R. The Impact of state policies on electric vehicle adoption -A panel data analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Datta, “BharatGAIN Report - Urgent Policy Reforms Needed for India EV Battery Recycling by 2030,” New Delhi, Oct. 2024. Accessed: Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.business-standard.com/content/press-releases-ani/bharatgain-report-urgent-policy-reforms-needed-for-india-ev-battery-recycling-by-2030-124101600964_1.

- Sanz-Torró, V.; Calafat-Marzal, C.; Guaita-Martinez, J.; Vega, V. Assessment of European countries’ national circular economy policies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 373, 123835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Ji, M.; Huang, X. An empirical study on the impact of tax incentives on the development of new energy vehicles: Case of China. Energy Policy 2024, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Shi, L. The role of government fiscal incentives in green technological innovation: A nonlinear analytical framework. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2025, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B. Financial subsidies, tax incentives, and new energy vehicle enterprises’ innovation efficiency: Evidence from Chinese listed enterprises. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0293117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.V. Financial Incentives for Promotion of Electric Vehicles in India- An Analysis Using the Environmental Policy Framework. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2022, 21, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Khalil, A.G.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Sayed, E.T.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Radwan, A.; Rezk, H.; Olabi, A. Electric vehicle impact on energy industry, policy, technical barriers, and power systems. Int. J. Thermofluids 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NitiAayog, “India Climate & Energy Dashboard,” Vasudha Foundation.

- Zewe, “Explained: Generative AI’s environmental impact,” MIT News, Jan. 17, 2025.

- Bahangulu, J.K.; Owusu-Berko, L. Algorithmic bias, data ethics, and governance: Ensuring fairness, transparency and compliance in AI-powered business analytics applications. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 25, 1746–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, I.A.; Adesokan-Imran, T.O.; Tiwo, O.J.; Metibemu, O.C.; Olutimehin, A.T.; Olaniyi, O.O. Addressing Bias and Data Privacy Concerns in AI-Driven Credit Scoring Systems Through Cybersecurity Risk Assessment. Asian J. Res. Comput. Sci. 2025, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.; Zhang, J.; Bariach, B.; Cowls, J.; Gilburt, B.; Juneja, P.; Tsamados, A.; Ziosi, M.; Taddeo, M.; Floridi, L. Artificial intelligence in support of the circular economy: ethical considerations and a path forward. AI Soc. 2022, 39, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF, “AI for India 2030: A blueprint for inclusive growth and global leadership,” World Economic Forum.

- Palaniswamy, S.; S, S.D.R.; Saravanan, M.; Anand, M. Social, Economic and Environmental Impact ofElectric Vehicles in India. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2022, 25, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanmardi, E.; Hoque, M.; Tauheed, A.; Umar, M. Evaluating the Factors Affecting Electric Vehicles Adoption Considering the Sustainable Development Level. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, M.; Kumar, L.; Zulkifli, S.A.; Jamil, A. Aspects of artificial intelligence in future electric vehicle technology for sustainable environmental impact. Environ. Challenges 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Kapoor, “The impact of AI on enhancing EV performance and efficiency,” The Statesman, Kolkata, Nov. 06, 2024.

- Golovianko, M.; Terziyan, V.; Branytskyi, V.; Malyk, D. Industry 4.0 vs. Industry 5.0: Co-existence, Transition, or a Hybrid. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A.; Dasig, J.D.D. Artificial Intelligence and Communication Techniques in Industry 5.0; Taylor & Francis: London, United Kingdom, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- S. George and A. S. H. George, “Industrial Revolution 5.0: The Transformation of the Modern Manufacturing Process to Enable Man and Machine to Work Hand in Hand,” Journal of Seybold Report, vol. 15, no. 9, pp. 214–234, 2020.

- Narkhede, G.B.; Pasi, B.N.; Rajhans, N.; Kulkarni, A. Industry 5.0 and sustainable manufacturing: a systematic literature review. Benchmarking: Int. J. 2024, 32, 608–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocasale, V.; Bruni, M.E.; Perboli, G. Technological insights on blockchain adoption: the electric vehicle supply chain use case. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2025, 28, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.R.; Lohmer, J.; Rohla, M.; Angelis, J. Unleashing the circular economy in the electric vehicle battery supply chain: A case study on data sharing and blockchain potential. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Lu and G. Serafeim, “How AI will accelerate the circular economy,” Harvard Business Review, Jun. 12, 2023.

- Rangarajan, R.; Murugan, T.K.; Govindaraj, L.; Venkataraman, V.; Shankar, K. AI driven automation for enhancing sustainability efforts in CDP report analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.v.D.; van Jaarsveld, W. Vendor-managed inventory in practice: understanding and mitigating the impact of supplier heterogeneity. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 60, 6087–6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juned, M.; Farooquie, J.A. VMI adoption in automotive industries: two different perspectives. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2022, 43, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodkumar, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Singha, N.S. Vinodkumar; Singha, N.S. Battery Management System Health Monitoring Using Artificial Intelligence. 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Emerging Innovations in Engineering and Technology (ICSEIET). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 31–35.

- H. P. Bhupathi and S. Chinta, “Battery Health Monitoring With AI: Creating Predictive Models to Assess Battery Performance and Longevity,” ESP Journal of Engineering & Technology Advancements, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 103–112, Nov. 2024.

- Sudhapriya, K.; Jaisiva, S. Implementation of artificial intelligence techniques in electric vehicles for battery management system. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2025, 20, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Sankar, S. N. Sankar, S. Vasudevan, and S. Mitra, “Promoting Clean Energy Usage Through Accelerated Localization of E-Mobility Value Chain,” New Delhi, 22. 20 May.

- S. Ibrahim and F. Abbasi, “Consumer Perception of Battery-as-a-Service ( BaaS): Implications for Electric Vehicle Adoption,”. Master Thesis, in Business Administration, Linkoping University, Linkoping, 2025.

- R. Kaushal, “India’s emerging role in EV battery recycling: Creating a circular economy,” PV Magazine India, Jul. 2025.

- Cavus, M.; Dissanayake, D.; Bell, M. Next Generation of Electric Vehicles: AI-Driven Approaches for Predictive Maintenance and Battery Management. Energies 2025, 18, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prenner, S.; Part, F.; Jung-Waclik, S.; Bordes, A.; Leonhardt, R.; Jandric, A.; Schmidt, A.; Huber-Humer, M. Barriers and framework conditions for the market entry of second-life lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.A.; Cook, C.A.D.; Palacios, J.; Seo, H.; Ramirez, C.E.T.; Wu, J.; Menezes, P.L. Recent Advancements in Artificial Intelligence in Battery Recycling. Batteries 2024, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Guerra, “Robotics and AI Lead the Future of EV Recycling,” BatteryTechOnline.

- D. Parr, “AI Is Well Set to Disrupt the Battery Supply Chain and Life Cycle,” IDTechEx.

- H. Roopalatha, “World EV Day 2025: Steering India towards a Sustainable Tomorrow,” CEO Insights. Accessed: Sep. 14, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ceoinsightsindia.com/business-inside/world-ev-day-2025-steering-india-towards-a-sustainable-tomorrow-nwid-21672.

- Ferreira, J.C.; Esperança, M. Enhancing Sustainable Last-Mile Delivery: The Impact of Electric Vehicles and AI Optimization on Urban Logistics. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangar, S.S.; Abazari, S.R.; Rabbani, M. A region-based model for optimizing charging station location problem of electric vehicles considering disruption - A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Williment, “Amazon India Surpasses 10,000 EVs in Sustainability Drive,” The Sustainability Magazine, Sep. 10, 2025.

- Min, H.; Fang, Y.; Wu, X.; Lei, X.; Chen, S.; Teixeira, R.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, X.; Xu, Z. A fault diagnosis framework for autonomous vehicles with sensor self-diagnosis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossary, M. Enhancing Urban Electric Vehicle (EV) Fleet Management Efficiency in Smart Cities: A Predictive Hybrid Deep Learning Framework. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 3678–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Prakash, C.; Shakir, M.; Alwetaishi, M.; Dhairiyasamy, R.; Rajendran, P.; Lee, I.E. Enhancing competitiveness in India’s electric vehicle industry: impact of advanced manufacturing technologies and workforce development. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, M.; Baldo, N.C. Profitability and Market Competitiveness of the Electric Vehicles Geely Auto. Int. J. Glob. Econ. Manag. 2025, 7, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Talukder, B. Supply Chain Performance and Profitability in Indian Automobile Industry: Evidence of Segmental Difference. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 24, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Islam, T.; Islam, K.S.; Hossain, A. Closing The Productivity Gap In Electric Vehicle Manufacturing: Challenges And Solutions. Innov. Eng. J. 2024, 1, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Czarnitzki, R. D. Czarnitzki, R. Lepers, and M. Pellens, “Adoption of Circular Economy Innovations: The Role of Artificial Intelligence,” 2025. [CrossRef]

- Feng, D. Research on Quality Inspection and Monitoring of Electric Vehicles under Green Energy Vision. MATEC Web Conf. 2024, 399, 00012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Savitskie, K.; Mahto, R.V.; Kumar, S.; Khanin, D. Strategic flexibility in small firms. J. Strat. Mark. 2022, 31, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirra, S.; Raut, R.D.; Kumar, D. Barriers to sustainable supply chain flexibility during sales promotions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 59, 6975–6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B, S.K.; Mohan, S.T. A Study on Customer Satisfaction Towards Electronic Cars in Kerala. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 3818–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh and A., K. Dey, “Electrifying Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach in the Indian Four-Wheeler Electric Vehicle Industry,” Srusti Management Review, vol. XVII, no. 1, pp. 24–37, Jun. 2024.

- Academic Society of Global Business Administration; Cheng, S. ; Lee, C.W. The Effect of Electric Vehicle Product Quality on Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty : Focusing on the Chinese Market. Acad. Soc. Glob. Bus. Adm. 2023, 20, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.; Singh, R. An assessment of customers’ satisfaction for emerging technologies in passenger cars using Kano model. Vilakshan - XIMB J. Manag. 2020, 18, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmani, A.; Dj, M. IMPACT OF AI ON SUSTAINABLE CIRCULAR ECONOMY: HARNESSING ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE. EPRA Int. J. Res. Dev. (IJRD) 2025, 10, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munonye, W.C.; Ajonye, G.O.; Ahonsi, S.O.; Munonye, D.I.; Akinloye, O.A.; Chigozie, I.O. Governing circular intelligence: How AI-driven policy tools can accelerate the circular economy transition. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Pandey, “Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Electric Vehicle Ecosystems: Challenges, Opportunities, and Models for Accelerated Adoption,” International Journal of Engineering Applied Science and Management, vol. 5, no. 12, Dec. 2024.

- Nindwani, “How Can the Environmental and Social Impacts of the EV Supply Chain, Particularly in Relation to the Sourcing of Critical Raw Materials, Be Assessed and Addressed through Responsible Sourcing Practices and International Cooperation?,” IOSR Journal of Business and Management, vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 24–38, Oct. 2024.

- Wirba, A.V. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of Government in promoting CSR. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 15, 7428–7454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Moloney and K. Raad, “The disruptive and transformative role of AI in the circular economy transition,” Ramboll, Mar. 2025.

- Medaglia, R.; Rukanova, B.; Zhang, Z. Digital government and the circular economy transition: An analytical framework and a research agenda. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Ansari, P. H. Ansari, P. Shukla, and M. Anees, “AI-Enabled Circular Economy Strategies: Transforming Start-Up Ecosystems for Sustainable Business and Technological Progress,” International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, vol. 7, no. 4, Aug. 2025.

- Raut, S.; Hossain, N.U.I.; Kouhizadeh, M.; Fazio, S.A. Application of artificial intelligence in circular economy: A critical analysis of the current research. Sustain. Futur. 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlet, E. Ma, and C. Pandya, “Artificial Intelligence and the Circular Economy,” 2019.

- Weißhuhn, S.; Hoberg, K. Designing smart replenishment systems: Internet-of-Things technology for vendor-managed inventory at end consumers. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 295, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Sherman, “Roadmap to Digital Circular Economy in India,” International Council for Circular Economy.

- S. P. Sarma, S. G. S. P. Sarma, S. G. Bhalla, and M. Kumar, “India’s Tryst with a Circular Economy,” Apr. 2023.

- G. Johansson and O. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Daniel, “Circular Economy 2.0: How Artificial Intelligence is Transforming Sustainability in Water Use,” Journal of Research and Development, vol. 12, no. 2, Jun. 2024.

- EEA, “Circular economy country profile 2024 – Germany,” 2024.

- S. Ahmed, “Artificial intelligence and the circular economy in Africa: Key considerations for a just transition,” Research ICT Africa.

- Roy, “National Strategy for AI,” 2018.

- Olawade, D.B.; Fapohunda, O.; Wada, O.Z.; Usman, S.O.; Ige, A.O.; Ajisafe, O.; Oladapo, B.I. Smart waste management: A paradigm shift enabled by artificial intelligence. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andeobu, L.; Wibowo, S.; Grandhi, S. Artificial intelligence applications for sustainable solid waste management practices in Australia: A systematic review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 834, 155389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singagerda, F.S.; Dewi, D.A.; Trisnawati, S.; Septarina, L.; Dhika, M.R. Towards a Circular Economy: Integration of AI in Waste Management for Sustainable Urban Growth. J. Lifestyle SDGs Rev. 2024, 5, e02642–e02642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Yu, J.; Chen, Z.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Ihara, I.; Hamza, E.H.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Artificial intelligence for waste management in smart cities: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1959–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Mulè, “Revolutionizing waste management: the role of AI in building sustainable practices,” AI for Good.

- R. M, “The Influence of AI on Sustainable Waste Management,” Infolks.

- Gahlot, N.S.; Nautiyal, O.P. AI-driven solutions for sustainable E-Waste Management: Reducing Environmental Impact on Natural Ecosystems. Indian J. For. 2024, 47, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DMR, “Digital Circular Economy Market By Offering,” Dec. 2023.

- Dao, S.V.; Le, T.M.; Tran, H.M.; Pham, H.V.; Vu, M.T.; Chu, T. Integrating artificial intelligence for sustainable waste management: Insights from machine learning and deep learning. Watershed Ecol. Environ. 2025, 7, 353–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]