Introduction

Migraine, a persistent neurological condition, affects about one billion individuals globally and ranks as the second greatest cause of disability across all age demographics, with a greater prevalence among women. Migraines often co-occur with other conditions, such as insomnia, which can both trigger and exacerbate migraine attacks. Quality sleep can alleviate migraine episodes. Nonetheless, the neurobiological mechanisms connecting insomnia to migraines are largely unexplored [

1].

The resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) approach has become extensively utilized in the study of migraine and insomnia. Previous studies indicate that the cerebellum contributes critically to pain processing and analgesic pathways in migraines [

2,

3], participates in the pain matrix network [

4,

5,

6], and serves as a candidate imaging biomarker for chronicity risk [

7]. Accumulating evidence indicates that the bilateral posterior cerebellar lobes play an essential part in the migraine pathophysiological mechanisms [

9]. Notably, as important regions of the posterior cerebellum, the cerebellum Crus (Crus) have been established as primary inhibitory elements in nociceptive processing [

10]. The cerebellum is also closely associated with insomnia. Particularly, the bilateral Crus I and

II located in the posterior lobe participate in arousal modulation and sensory prediction through thalamic coupling [

8,

9,

10]. Previous studies implicate the posterior cerebellum, particularly the crus, in the pathogenesis linking migraine and insomnia, suggesting it may represent a shared pathological pathway in individuals with both conditions. However, to date, no relevant neuroimaging evidence has been established.

This study employed amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF) to detect local variations in brain functional activity, followed by seed-based functional connectivity (FC) analyses using bilateral cerebellar Crus I and II as seeds to examine differences in intrinsic FC networks among migraine subtypes. We aimed to characterize alterations in cerebellar functional properties in migraineurs with or without insomnia in order to examine their correlation with sleep disturbances.

Methods

Participants

This study recruited fifty-eight patients diagnosed with migraine without aura (MwoA) from the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. The sample was made up of twenty-four migraine with insomnia (MwI), thirty-four migraine with no insomnia (MwoI), and thirty-one healthy controls (HCs) patients. Right-handed individuals of Chinese Han descent underwent neuropsychological assessments and rs-fMRI scans.

The diagnostic criteria for MwoA are derived from the International Classification of Headache Disorders, Third Edition (ICHD-3). Insomnia was identified using the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition (ICSD-3). A PSQI score exceeding 7 indicates symptoms of insomnia. The MwoI group meets the diagnostic criteria for MwoA, while the MwI group requires concurrent diagnoses of MwoA and insomnia. Diagnoses of MwoA were established by two senior attending neurologists in accordance with the ICHD-3. Patients with discrepant assessments were excluded.

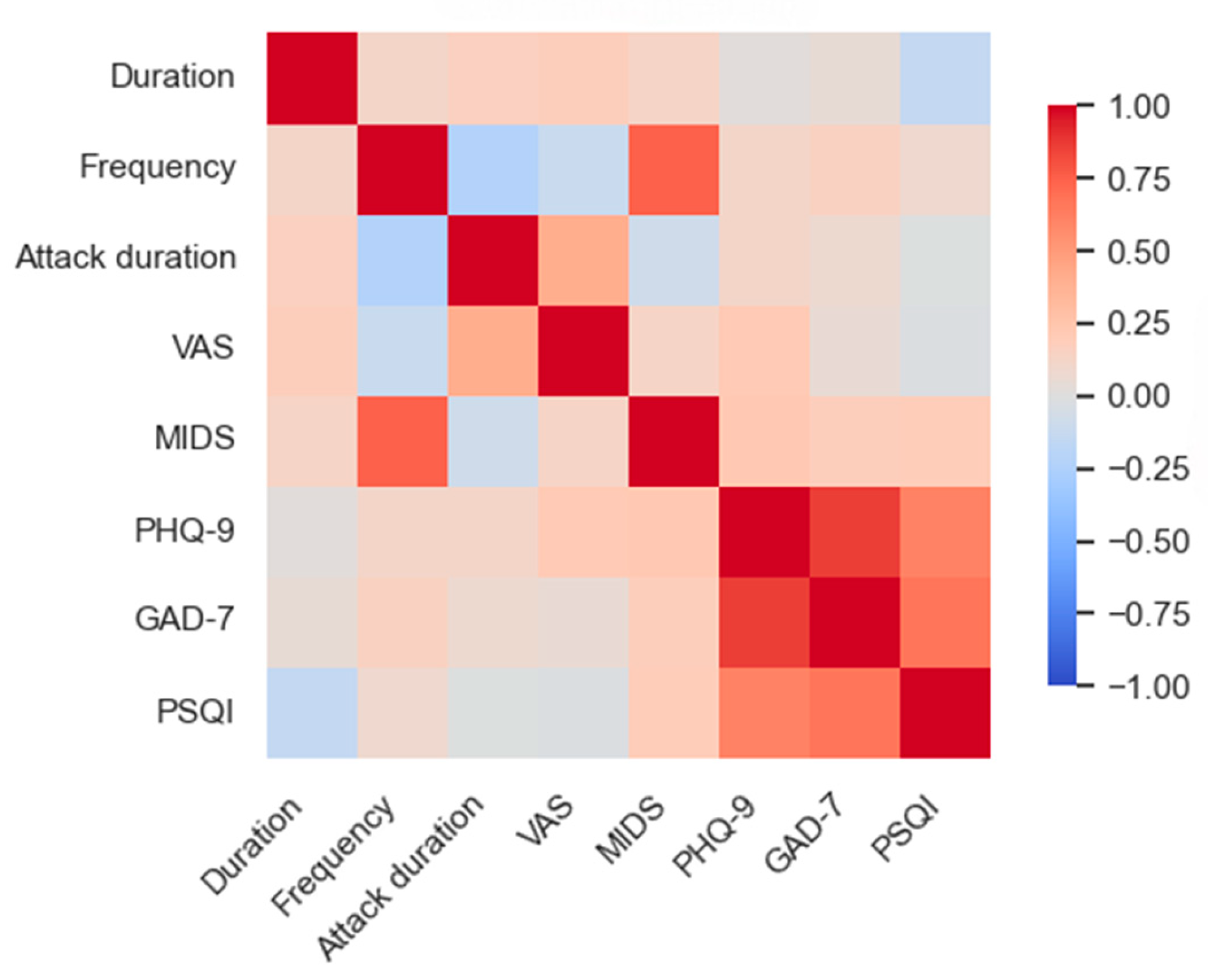

Participants underwent neuropsychological assessments (the PHQ-9, PSQI, and GAD-7 scales) before imaging. In addition to these, migraine patients reported the frequency of their headaches (days/month) over the previous three months, the severity of their headaches on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), the duration of their headaches, and their level of disability using the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS).

Exclusion criteria were (1) history of smoking, alcohol consumption, and coffee drinking. (2) History of neurological and psychiatric disorders other than migraine (3) Use of sedatives or anxiolytic/antidepressant medications within the past week, or prophylactic migraine medication within the past three months. (4) Contraindications to MRI. For HCs, participants were required to have good sleep quality and stable mood, with exclusion criteria identical to those for the MwI and MwoI groups.

Imaging Data

The MRI scans were conducted with a Siemens Verio 3.0-Tesla machine with a 64-channel head coil from Siemens Corporation, Erlangen, Germany. T1-weighted volumes of high resolution were acquired via a gradient-echo sequence with a TR/TE value of 2200/2.46 ms, an 8-degree flip angle, a 230 × 230 mm field of view, a 256 × 256 acquisition matrix, and a 0.9 mm slice thickness without an interslice gap. Each volume comprised 208 contiguous slices and was acquired with a single excitation. Resting-state BOLD data were acquired over 8.17 minutes using echo-planning scans with a TR/TE value of 2000/30 ms, an 80-degree flip angle, a 96×96 acquisition matrix, and a 2 mm slice thickness without interslice gaps. A total of 84 interleaved slices were captured using simultaneous multislice imaging with a multiband factor of 3, resulting in 240 volumes per run. During the exam, participants were instructed to close their eyes, remain awake, and utilize foam earplugs to alleviate discomfort caused by noise.

First Data Processing

Using the rs-fMRI Data Analysis Toolkit Enhanced Version 1.28 (RESTplus 1.28) and the twelfth version of the Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12), imaging data were processed. Data preprocessing includes discarding the initial 10 volumes, correcting motion, normalizing to MNI space using DARTEL, applying linear detrending to eliminate confounding covariates (global signals, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and six head motion parameters), filtering in the 0.01–0.08 Hz range, and spatial Gaussian smoothing (FWHM = 6 mm). Subjects exhibiting head movement exceeding 2 millimeters or 2 degrees in any direction were excluded.

The Computation of ALFF

The Fourier transform algorithm is applied to compute the power spectrum’s square root, named the Amplitude of Low Frequency Fluctuation (ALFF), for each voxel within the 0.01–0.08 Hz range. Each voxel's ALFF gets normalized through dividing it by the mean ALFF of the entire brain, producing a normalized ALFF map. For statistical comparison, each subject's ALFF map is converted to z-scores by centering on the whole-brain mean and scaling with the voxel-level whole-brain standard deviation.

FC Analysis from Seeds

After completing ALFF and ReHo analyses, we designated the bilateral Crus I and Crus II of the cerebellum as areas of interest (ROIs). These were independently identified and obtained from the Automated Anatomical Labeling Atlas 3 to produce corresponding binary masks. These masks were subsequently intersected with the whole-brain gray matter mask to confine the analysis to gray matter regions and exclude non-gray matter voxels. The resulting intersection mask ultimately served as the ROIs for subsequent FC analysis. The average time course of the ROI was correlated with that of the remaining brain voxels, followed by correlation analysis. The correlation coefficients were standardized with Fisher's Z transformation.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed utilizing SPSS version 27.0, with a significance level established at p < 0.05. A one-way ANOVA assessed continuous demographic and neuropsychological variables across three groups. Chi-square tests evaluated categorical variables, controlling for age, gender, and education. Partial correlation analysis examined the relationships between headache characteristics and neuropsychological indicators within the migraine group. At the level of individual voxels, ANOVA was conducted in SPM12 to compare ALFF and FC values, with subsequent pairwise post-hoc tests employed to determine differences among each group pair. The analyses took into account gender, age, years of education, and scores related to anxiety and depression for adjustment. Statistical significance was assessed using a voxelwise threshold of p < 0.001, complemented by cluster-level family-wise error (FWE) correction at FWEp < 0.05. Moreover, analyses of partial correlation were carried out to investigate the links between brain dysfunction and clinical traits in migraineurs while adjusting for gender, age, and education (p<0.05). The extraction of signals from atypical brain regions was conducted using the RESTplus V1.28 toolbox. This tool calculates the mean signal within each FWE-corrected cluster and performs a Fisher Z-transformation.

Discussion

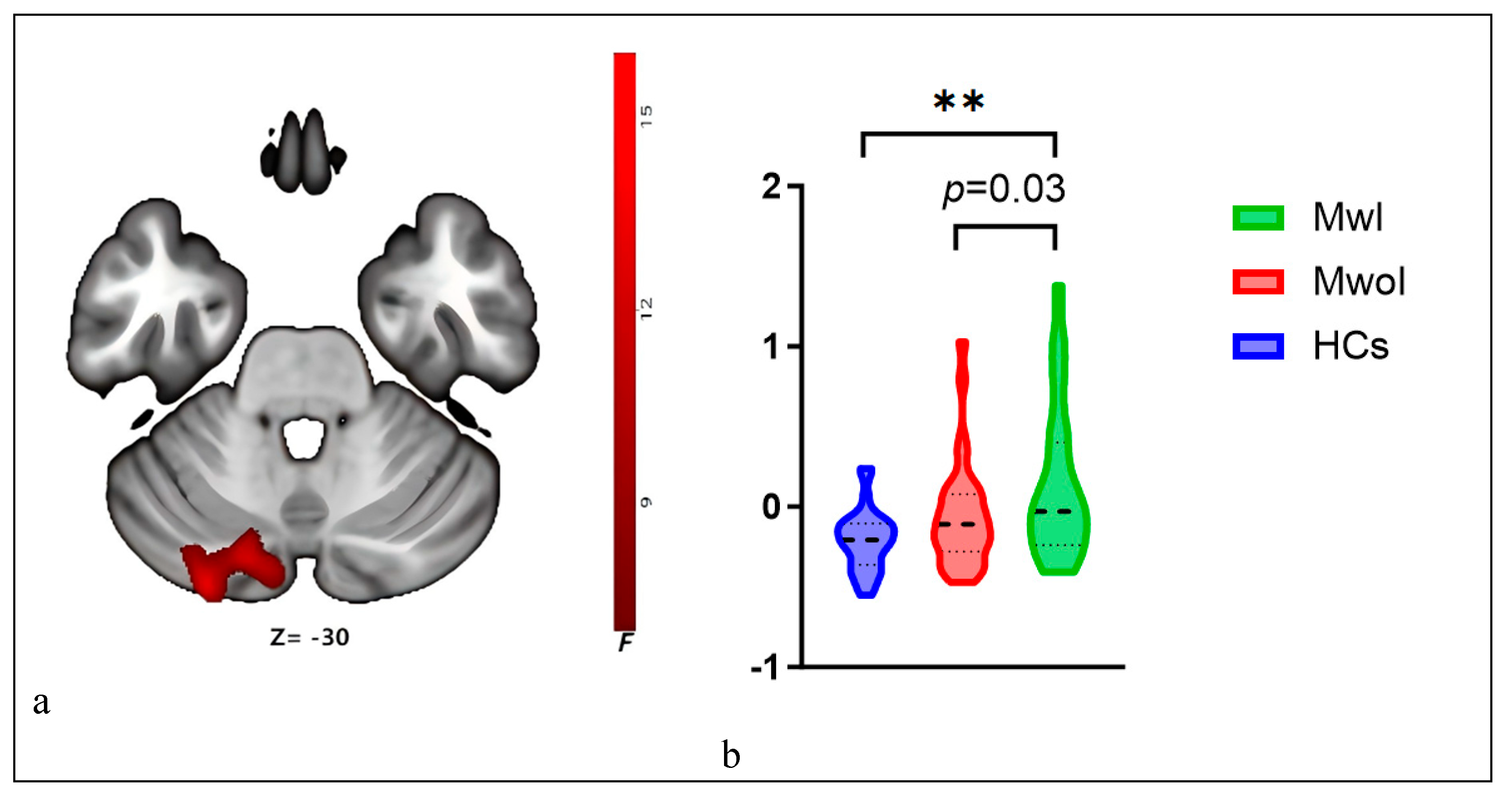

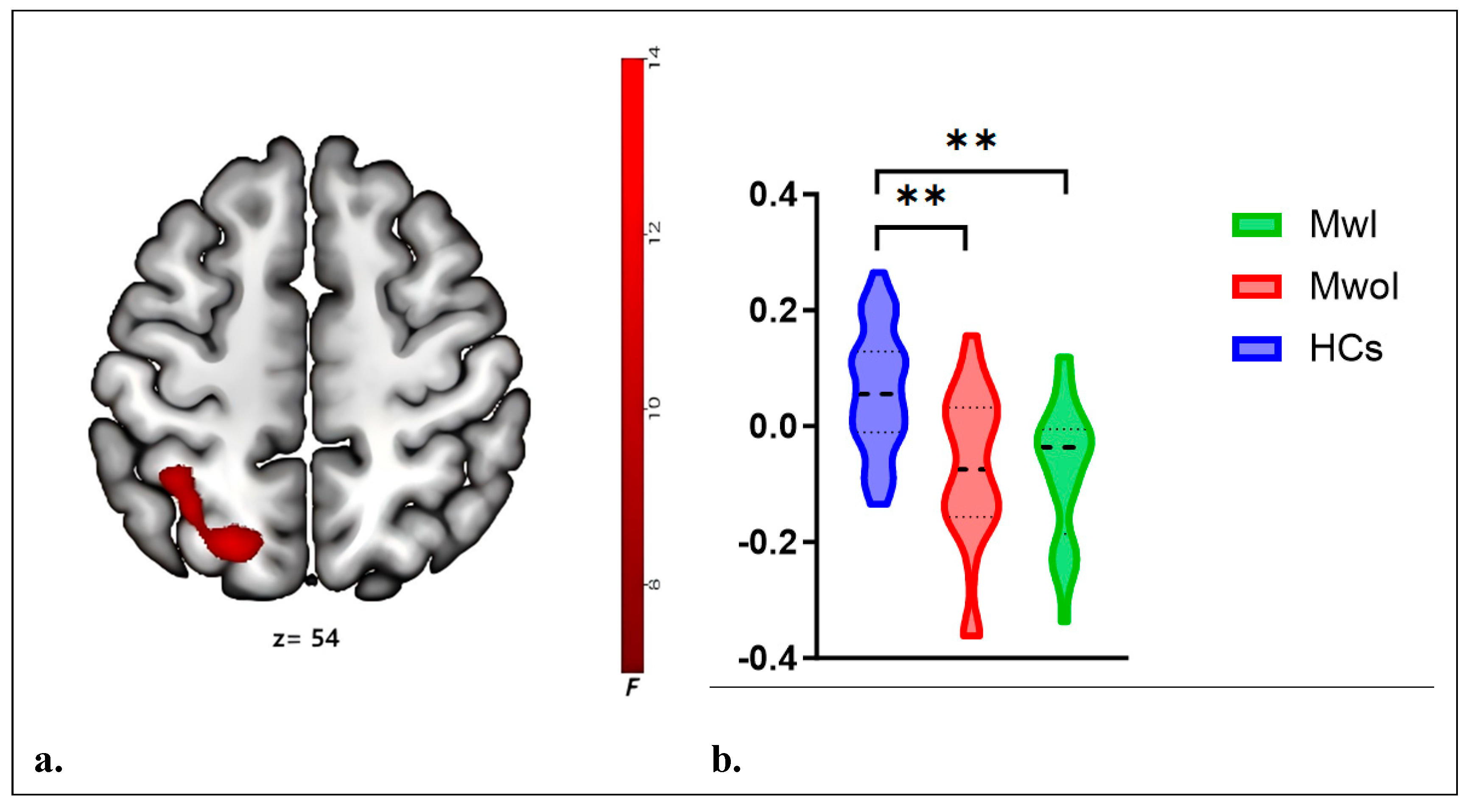

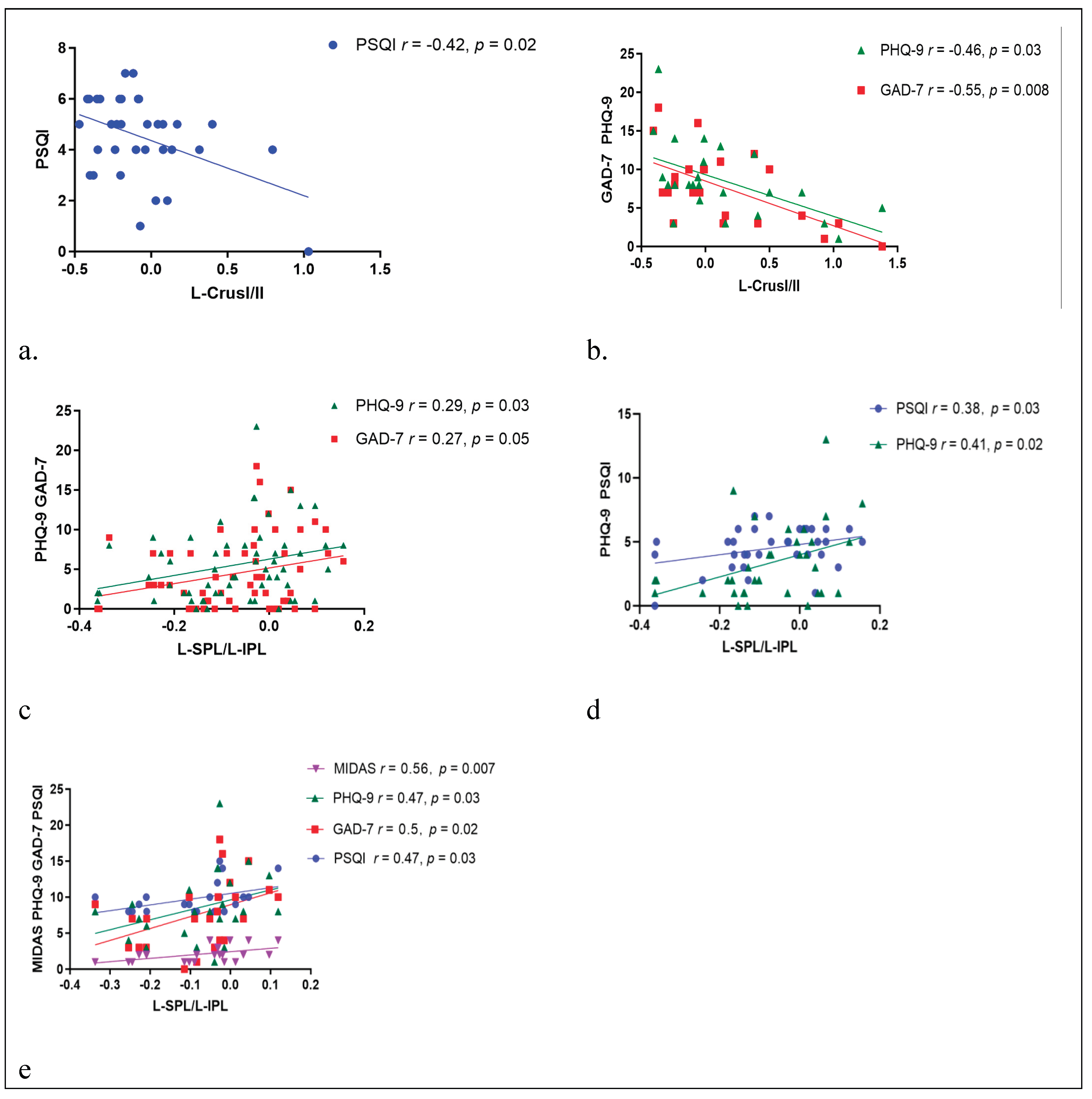

This study investigated the FC network characteristics in individuals with MwI and MwoI. Both groups exhibited elevated ALFF values in the cerebellar network (left Crus I and II) compared to HCs, with a more significant increase noted in the MwI group. Additionally, changes in the right Crus I FC network were primarily noted within specific functional networks: the dorsal attention network (DAN), such as the left SPL, and the default mode network (DMN), such as the left IPL. Compared to the HCs group, both the MwI and MwoI groups had diminished FC strength with the left SPL and IPL. Elevated ALFF values in the left Crus I and II are associated with milder neuropsychological and sleep disturbances in migraine patients. Conversely, alterations in the right Crus I FC network reveal that increased FC values in the L-SPL and L-IPL correlate with more severe neuropsychological and sleep disturbances, as well as heightened migraine-related disability.

Among migraine patients, PSQI is positively correlated with both GAD-7 and PHQ-9, the attack duration

is positively correlated with VAS, and MIDAS is positively correlated with headache frequency. Migraine patients frequently experience comorbid neuropsychological disorders and insomnia, which can trigger the exacerbation of their symptoms [

11]. Therefore, em

otional management and sleep improvement are particularly important for individuals with migraines.

Traditionally linked to motor control, the cerebellum is now recognized as integral to migraine-related pain transmission and analgesic pathways. Migraine sufferers show heightened local FC density in the cerebellum, inversely related to pain intensity.

Temporal dynamic irregularities in the cerebellum (mostly in bilateral Crus) among migraine sufferers are uncovered by Dynamic fALFF. These irregularities are linked to the clinical severity, indicating that the cerebellum serves as a crucial modulation hub in the migraine network [

5].

The connection strength between the hypothalamus and the cerebellum (primarily in bilateral Crus) can serve as a candidate imaging biomarker for migraine severity and chronicity risk [

7].

Fu's study has demonstrated abnormal cerebral perfusion in migraine patients, primarily involving the bilateral Crus, which correlates with clinical indicators (migraine attack frequency, disease duration, and disability severity) [

12]

. The activity in the Crus is heightened under pain stimulation and exhibits cognitive and emotional features

, which are related to

pain encoding [

13]

. The cerebellum predominantly exerts an inhibitory effect on nociception. The activation of the Crus is more pronounced in migraine patients compared to control subjects, serving to sustain its inhibitory function [

14]

. The aforementioned studies all support the notion that the cerebellum, particularly the Crus region, possesses a pain regulation mechanism in migraines.

The cerebellum is involved in sleep regulation by modulating monoaminergic neurotransmission and is closely connected to the sleep-wake cycle. Among individuals with chronic insomnia, the FC between the ascending arousal network and cerebellar networks, as well as the internal connections within the cerebellar networks, is enhanced [

15,

16]. Cerebellar lobules, mostly located in the posterior lobe (especially in Crus, VI, VIIb, and VIII) or the vermis, participate in arousal regulation and sensory prediction through coupling with the thalamus [

8]. Cerebellar gray matter volume, especially in the posterior lobe, changes gradually as insomnia severity increases. Increased gray matter in the right Crus II may represent a compensatory mechanism [

9]. The bilateral Crus exhibits significant alterations in FC with the frontoparietal network following sleep deprivation [

10]

. The bilateral cerebellar Crus serves as a crucial network node for motor interventions aimed at improving sleep [

17]

.

Our study found heightened local brain activity in the left Crus among migraine patients, with ALFF values negatively correlating with anxiety, depression, and sleep disorder scale scores. This data supports the modulatory role of the cerebellum, specifically Crus, in migraineurs experiencing insomnia. However, this regulatory mechanism is impaired. Abnormal functional activity in the left Crus is a key pathological mechanism shared by migraine patients with insomnia, highlighting the cerebellar crus as a crucial focus in brain functional studies of migraine.

The SPL is a core component of the dorsal attention network, participating in spatial attention, sensory-motor integration, switching between internal and external attention, and the pointing and maintenance of working memory. It serves top-down control functions, and in migraine patients, abnormal brain activity is observed in the SPL during the processing of negative emotions [

18]. The IPL's posterior region, overlapping with the default mode network, acts as an aspect in attention reorientation, context updating, and semantic and emotional processing. Within the DMN, the IPL integrates intense headache signals into the insula's pain processing and interoceptive network during migraines, aiming to mitigate pain perception via cognitive strategies. The SPL and IPL participate in pain perception and pain processing, and the weakening of their functional connections may reflect abnormalities in pain perception and attention in migraine patients [

19]

. Insufficient top-down inhibition of the SPL/IPL leads to difficulty in falling asleep at night and easy awakening [

20]. Insomnia causes structural alterations in the SPL/IPL, impairing functions such as sensorimotor coordination, spatial cognition, attention, working memory, and emotional regulation in the parietal lobe [

21]. The cerebellum can regulate the function of the DMN by way of its associations with the prefrontal and parietal cortex, indirectly affecting the overall function and integrity of the DMN. If the cerebellum's function or structure is impaired, it may not be able to regulate or coordinate the activity of the DMN effectively, thereby exacerbating the abnormal pain processing and stress response of the DMN in migraines [

3,

19].

Our study identifies diminished FC with the left parietal lobe in individuals suffering migraines compared to the HCs, and the FC strength correlates positively with sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, and disability in migraine sufferers. These findings indicate that the FC network between the cerebellar Crus and the DMN and DAN is imbalanced and reorganized in individuals with comorbid migraine and insomnia, and that the top-down regulation mechanism of migraines is compromised. The altered FC with the left parietal lobe may serve as a biomarker for individuals suffering from both migraine and insomnia.

Even though the present research offers neuroimaging proof of regional cerebellar functional irregularities and modified cerebellar FC in those with co-occurring migraine and insomnia, it has a few limitations. The cross-sectional design of this investigation complicates the establishment of a causal link among migraine, changes in FC networks, and local cerebellar dysfunction. In the future, additional longitudinal investigations will be required to verify this. Secondly, the limited sample size led to the absence of some relevant capabilities. Research in the future ought to concentrate on increasing the number of samples. Thirdly, the evaluation of the sleep scale is subjective, and this may lead to grouping bias. In future research, objective methods for measuring insomnia, like polysomnography, ought to be utilized. Finally, the group suffering from migraines was not differentiated further based on subtype or the period of onset. Subsequent analyses ought to take these elements into account.