1. Introduction

Chronic insomnia disorder (CID), identified based on established diagnostic criteria, is estimated to impact approximately 5% to 15% of adults [

1,

2,

3]. Despite its high prevalence, the precise pathogenic mechanisms underlying this disorder remain partially understood [

4]. A key conceptual model for the pathogenesis of CID is the hyperarousal hypothesis, which is based on the observed persistent state of physiological, cognitive, and emotional hyperactivation in CID patients [

4,

5,

6]. The model posits that individuals with chronic insomnia exhibit a heightened arousal, which is not limited to the nighttime but extends throughout the wake state, implicating dysregulation of neural circuits responsible for sleep-wake control and emotional regulation [

7]. However, while this conceptual model is clinically informative, it does not provide an insight into the precise neural correlates, underlying CID. Structural imaging studies show numerous and inconsistent alterations across various regions of the grey matter in the central nervous system, failing to adequately identify the neural structures, involved in the pathogenesis of CID [

8,

9].

Resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) is much more informative in identifying the neurobiological underpinnings of CID, as it reflects the quiescent, involuntary nature of sleep initiation [

10]. It also reveals the interaction (functional and effective connectivity) within and between the various brain networks, processing internal and external information at rest and therefore potentially involved in the pathogenesis of the hyperarousal state in CID [

4]. Functional connectivity (FC) studies in CID patients illustrate changes in the default mode network (DMN), executive control network (ECN) and salience network (SN), which are involved in self-referential processing, internal mentation, emotional plasticity, and goal-directed attention [

11,

12]. Findings include altered DMN coherence, reduced connectivity between prefrontal and limbic regions, and disrupted SN engagement during task and resting states in CID patients compared to healthy controls (HC) [

13,

14]. Moreover, disruptions in ECN are a common finding among patients with impaired sleep. Reduced FC in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and other ECN-regions has been linked to impaired cognitive control and increased vulnerability to emotional dysregulation among patients with cognitive impairment and insomnia symptoms [

15]. In addition, reduced dynamic FC between major nodes of the anterior SN and ECN is observed in insomniacs, attributing to the impaired SN dynamics, which fails to modulate the enhanced top-down cognitive control [

16,

17,

18].

However, while FC provides an insight into which regions are co-active, little is known about the causal connectivity changes that may underlie these disturbances and contribute to the persistent hyperarousal state in CID. Effective connectivity (EC) describes the influence of one brain region over another, incorporating temporal and causal effects of the regions in a neural circuit [

19]. Currently, only one study has explored the EC between the main brain networks in patients with CID. Li et. all report aberrant EC between right anterior insula (AIR), a key hub in the SN, and precuneus (major region of the DMN [

20]. These alterations are related to the cognitive impairment, altered working-memory and decision making, which are characteristic traits of CID patients, but do not provide insight into the observed hypervigilant state of CID.

Based on the findings in the available literature we wanted to explore the EC in patients with CID compared to healthy individuals. We hypothesized that EC between hubs of the DMN, ECN and SN is disrupted in individuals with chronic insomnia, impairing the SN's ability to modulate and “switch” between DMN and ECN, as the neurofunctional substrate of the hyperarousal state in CID.

The aim of this study is to analyse the EC between key regions of the DMN, ECN, and SN in CID patients using Dynamic Casual Modelling as potential elements of the pathophysiological complex of chronic insomnia in line with the hyperarousal theory.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective, cross-sectional study was performed at the Medical University of Plovdiv, Bulgaria and approved by the ethics committee of the university (grant number: НО-11/2021 (Р8540/2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Thirty-one CID patients (mean age 33,8 ± 9,1; nine males), complying with the diagnostic criteria of the “International classification of sleep disorders, III-rd. edition, TR” (ICSD-III TR) were recruited for this study, as well as 24 age- and sex-matched HC (mean age 29,5; ± 7; nine males).

The inclusion criteria were a) Age between 18 and 65 years; b) Diagnosis of CID, according to the ICSD-III TR criteria (for the patients’ group). The following exclusion criteria were applied to both groups: a) Another sleep disorder, such as moderate or severe sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, impaired circadian rhythmicity etc.; b) Psychiatric disorder; c) Intake of psychoactive medications; d) Counterindications for MRI scan; e) Shift-work; f) Severe somatic diseases, significantly worsening sleep quality and quantity; g) Neurologic diseases. All participants met these criteria and were included in the study.

Sleep and emotion questionnaires: All participants filled out the following scales, assessing insomnia symptoms, sleep quality and depressive traits: Insomnia severity index (ISI), Beck depression inventory (BDI) and Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS).

Polysomnography. All subjects were assessed by clinical interview and underwent unattended, single-night, home-based polysomnography (PSG) using NOX A1 PSG systems, to rule out a concomitant sleep disorder. The results were manually scored by two certified somnologists (K.T. and A.D.) based on version 2.3 of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria. The main parameters include reported sleep onset latency (SOL), total sleep time (TST), time in bed (TIB), sleep efficiency (SE), sleep stages (N1, N2, N3 and REM) in minutes and percentage, total wake time, wake after sleep onset (WASO), and REM-latency.

MRI scanning and Data Analysis. The scanning of the participants was performed on a 3-T MRI system (GE Discovery 750w) and included a high resolution structural scan (Sag 3D T1 FSPGR, slice thickness 1 mm, matrix 256 × 256, TR (relaxation time)—7.2 ms, TE (echo time)—2.3, flip angle 12°,), and a functional scan 2D Echo Planar Imaging (EPI), slice thickness 3 mm, 36 slices, matrix 64 × 64, TR—2,000 ms, TE—30 ms, flip angle 90°, 192 volumes. Before the EPI sequence subjects were instructed to remain as still as possible with eyes closed and not to think of anything in particular.

Data analysis was conducted using SPM12 (Statistical Parametric Mapping;

http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) implemented in MATLAB R2020b (Windows version). During the preprocessing stage of the functional images, standard procedures were applied: realignment, co-registration with structural scans, spatial normalization to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template, and smoothing using a Gaussian kernel with a full width at half maximum of 6 mm.

Resting-state data were analyzed at the first level using a general linear model (GLM) applied to the time series. Regions of interest (ROIs), defined as 6-mm radius spheres, were selected a priori based on their known involvement in the SN, DMN and ECN. ). The combined signal of dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) is represented as the common medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). This combined ROI merges and averages the signals from both areas for subsequent analysis, which allows for a broader representation of the MPFC in our study. The MNI coordinates of these ROIs are listed in

Table 1.

Subsequently, spectral dynamic causal modeling (spDCM) was applied to the chosen ROIs. A fully connected models was implemented, whereby each region was assumed to influence all others. Unlike stochastic DCM, spectral DCM estimates EC based on the cross-spectral density of neuronal state fluctuations rather than from raw time series data. The individual spDCM models were jointly estimated using the parametric empirical Bayes (PEB) approach available in SPM12. Finally, the resulting A-matrix parameters—representing the EC strengths—were extracted and used for further statistical analyses in SPSS.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analysis of all demographic and clinical data, as well as connectivity strengths and PSG-data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows. Normality of distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Demographic characteristics, questionnaire results, and sleep parameters, were compared using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, or chi-square tests. Correlations were performed using Pearson’s correlation method. One sample t test against zero was used to identify the statistically significant connections within each group. Mann–Whitney U test was applied to search for differences between groups. To account for multiple comparisons, the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction was applied across the significant within-group tests (m = 5). All five connections remained significant at an adjusted α of 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

No significant differences were observed between patients and HC in age, sex and education level. CID patients scored higher on the ISI and BDI. As expected, CID patients did not show higher levels of sleepiness compared to HC, despite the reported sleep complaints. The CID group demonstrated lower levels of self-reported sleep quality and had significantly higher WASO and total time in bed, compared to the HC group. PSG data showed higher N2 stage and lower N3 stage in minutes and as percentage of total sleep time, compared to good sleepers. Demographic and clinical data are presented in

Table 2.

3.2. Connectivity Strengths

The analysis, conducted as outlined above, revealed multiple significant connections (different from zero) among the ROIs within each group. The connections demonstrating statistically significant differences between the groups were five in total. Of them 3 were present (different from zero) only in the CID group (

Table 3), while the other 2 were seen only in HC (absent in patients) (

Table 4).

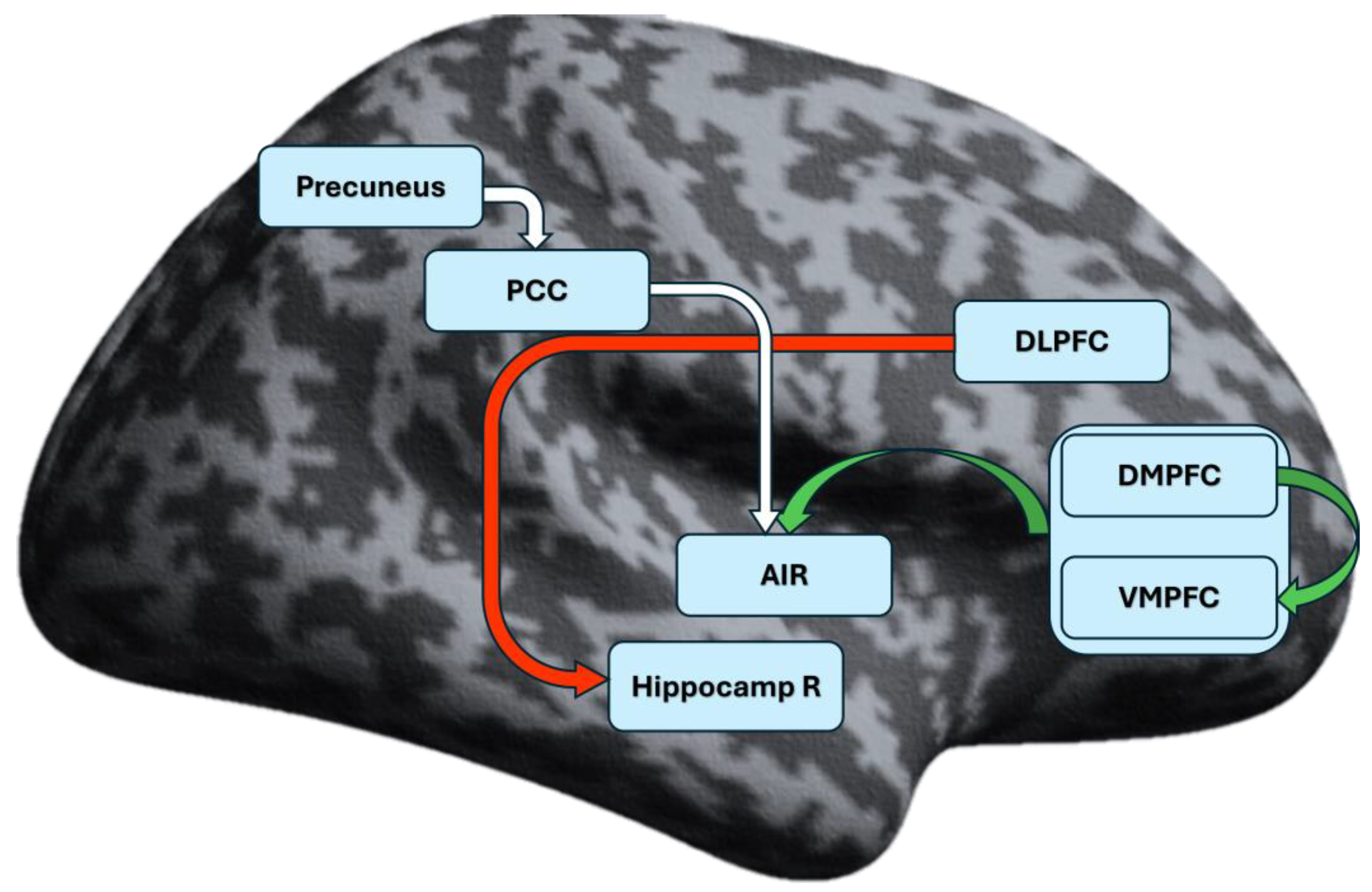

The aberrant connections in the CID group involved mainly the prefrontal cortex and right hippocampus (Hippocamp R). Connection lacking in the patient group (present only in HC) engaged the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), precuneus and AIR (

Figure 1).

3.3. Correlation Between Connectivity Strengths, Questionnaires and PSG Parameters

Pearson correlation analysis was performed, and the results are presented in

Table 5. Significant negative association between DLPFC to Hippocamp R connectivity and ISI scores (r = –.51, p < .001) was identified. We also found significant negative correlations between this connectivity and BDI scores (r = –.27, p < .05), total wake time (r = –.32, p < .05), and WASO (r = –.30, p < .05). ISI scores were positively correlated with BDI (r = .70, p < .001), total wake time (r = .49, p < .01), SOL (r = .30, p < .05), and WASO (r = .45, p < .001).

4. Discussion

The major findings of this study indicate that there are distinct alterations in the reciprocal connectivity patterns among hubs from the DMN, SN, and ECN in patients with insomnia as compared to healthy individuals. We observed statistically significant altered EC between the patients and HC group in five connections, namely from DMPFC to VMPFC (excitatory), from MPFC to AIR (excitatory), from PCC to AIR (excitatory), from Precuneus to PCC (excitatory), and from DLPFC to Hippocamp R (inhibitory). Moreover, the coupling values for the DMPFC - VMPFC, MPFC - AIR, and DLPFC - HippocampR connections significantly differed from zero only in the patients’ group, whereas the PCC - AIR and Precuneus - PCC connections were significantly different from zero in the HC group (lacking in the patients’ group).

The MPFC has been proven to be a pivotal structure for the pathophysiology of insomnia. Reduction in the regional homogeneity (ReHo) values in MPFC coupled with increased ReHo in the cuneus has been observed in patients with chronic insomnia with and without cognitive impairment as opposed to HC [

21]. Furthermore, several studies have demonstrated statistically significant improvement of sleep quality after low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the DLPFC which also resulted in alteration of the serum BDNF and GABA levels and of the tissue GABA+/Cr concentration [

22,

23]. Considering the primary functions of the MPFC related to emotion-processing, motor control, and decision making we may speculate that the observed excitation of the AIR leads to hyper-stimulated salience which prevents the individual from falling asleep and maintaining the sleep state [

24,

25,

26]. The increased excitatory bias may also result in disruption of the integrative insular function thus leading to disorganization of the “switching” between the DMN and ECN, and the resulting failure to inhibit wakefulness, which is in concordance with the hypothesized hyperarousal.

Another finding, supporting the aforementioned impaired “switching” mechanism, is the observed excitatory PCC – AIR connection in HC, which is not observed in the CID group. Impaired connectivity between those key nodes of both networks is reported in a study, exploring FC in patients with impaired cognitive control, highlighting the role of SN in reducing DMN’s activity at rest [

27]. The authors found that the connectivity strength is increased in their HC group, which is in concordance with our data, and elucidates on the importance of these interactions, as it pertains to the attentional detection of salient stimuli and reducing DMN activity, when attention is externally focused. Nonetheless, Chen et al. reported overactivation of the insular region in insomniacs [

28]. Potential explanation for the observed difference could be found in the methodology of their study, as their testing is performed when the CID patients are instructed to fall asleep during the scan, a fact that implies active engagement of the otherwise passive process of sleep initiation. The latter phenomenon, corresponding to the attention-intention-effort hypothesis of insomnia, could be the cause of and not the consequence from the overactivated insula [

29,

30]. However, it should be noted that the actual role of the SN is more intricate and that there is marked complexity of the possible mechanisms, altering the regulation between the brain networks.

Of particular note is the previously reported right lateralization of the AIR’s ability to modulate and act as a switch mechanism, which is a phenomenon observed in our study as well [

20]. This function involves detecting salient internal and/or external stimuli and initiating a shift from self-referential (DMN) to goal-directed (ECN) processing [

31]. Our data aligns with the results of Li et al, suggesting aberrant salience processing, supporting the idea of impaired modulation between internally oriented to externally directed cognitive processing [

32]. In contrast to these results, Long et al. report altered insular FC after sleep deprivation, particularly in young adults, suggesting that the impaired signalization between the control networks is a consequence of impaired sleep and not a causative factor [

33]. On one hand, these discrepancies may be attributed to the methodological differences (temporal vs causative correlations), while on the other hand the observed by Long et al alterations may reflect short-term compensations, compared to the long-term changes observed in insomniacs, indicating dysfunctional top-down regulation.

Additionally, the excitatory Precuneus – PCC connection, present only in HC, could be responsible for the maintenance of functional integrity within the DMN, and we could speculate that its absence in the CID group reflects poor internal regulation and increased mind-wondering or rumination in patients. Our hypothesis is based on the previously reported data, suggesting that decreased FC between key nodes of the DMN is in the basis of CID and contributes to the inability to disengage from internal thoughts, which may underlie the hyperarousal state [

34,

35,

36].

Furthermore, it should be noted that changes in the grey matter volume and connectivity patterns of the prefrontal cortex and insula have been observed not only in CID but also in major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders [

37,

38]. These conditions frequently co-occur whit CID, which may indicate the existence of overlapping underlying pathogenetic mechanisms, especially pertaining to the impaired emotion regulation and cognitive dysfunction[

3]. Moreover, dysconnectivity of the insular cortex has been suggested as a possible underlying factor for ruminations which are seen in both major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders and can be considered as a potential cause of sleep disturbances [

39].

The DLPFC, a major hub of the ECN, has been associated with working-memory capacity, attention regulation and inhibitory self-control [

40,

41]. Previous study, assessing brain activations via functional near-infrared spectroscopy, has shown that prefrontal cortex FC is impaired in patients with short-term insomnia disorder, with the connectivity strength being significantly correlated with the severity of the sleep disorder [

42]. Additionally, targeting the DLPFC with transcranial magnetic stimulation has shown clinical improvement in CID patients, which persisted after the treatment course [

23]. Our findings, concerning the inhibitory connection between DLPFC and HippocampR, could provide further insight into the importance of those regions in CID. We speculate that this could lead to impaired emotional regulation and consolidation of episodic memory. Both phenomena are common in insomniacs, potentially leading to fragmented sleep and thought ruminations [

43,

44,

45]. Likewise, an overly activated DLPFC may trigger excessive top-down control, reflecting the cognitive hyperarousal state [

46]. On the other hand, this hypothesis is not consistent with previous findings, describing reduced metabolism and activity of the prefrontal cortex in insomnia patients at rest, which underscores the complexity of this hypothesis, suggesting that additional factors may also account for the hyperarousal in CID [

47].

Additionally, the DLPFC to Hippocamp R connection in our study shows significant negative correlation with the ISI and BDI scores, indicating that the stronger the inhibition is, the higher the severity of insomnia and altered emotion regulation are. Similar findings are reported by authors, exploring insomnia severity in relation to the level of prefrontal activation[

48,

49]. These results emphasize the contribution of DLPFC to the mechanisms, responsible for regulation and maintenance of normal sleep.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore EC across chronic insomnia patients and HC, utilizing Dynamic Causal Modeling analysis. While the present study provides valuable insights into the altered connectivity patterns, which elucidate the potential neurologic mechanisms underlying the hyperarousal model for insomnia, there are some limitations, which warrant consideration. First, the sample size is relatively small, which may limit the interpretability of the results and the extrapolation of data. Second, potential confounding factors, such as duration of the insomnia symptoms or variability of the sleep quality for the period during which the patients underwent scanning were not exclusively controlled. Furthermore, this is a cross-sectional study, therefore we cannot directly identify causal relations or temporal progression of connectivity patterns. Future research should address those limitations by increasing sample size, controlling for possible confounding factors and enhancing translational relevance.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study shed light on the potential neurologic substrates of the hyperarousal model of CID. Our results indicate that EC among the DMN, ECN, and SN is altered in individuals with CID. In particular, disruptions within the DMN and between the DMN, SN and ECN reflect an impaired ability to appropriately shift between internally and externally directed cognitive states—an imbalance potentially underlying the hyperarousal state of CID.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G. and K.T..; methodology, R.P.; software, R.P and S.K..; validation, K.T. and S.K..; formal analysis, T.G..; investigation, T.G, R.P, A.D. and K.T.; resources, T.G. and K.A..; data curation, T.G. and A.T-R.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G..; writing—review and editing, R.P. A.T-R., K.A., K.T, and S.K.; visualization, T.G. and R.P.; supervision, K.T..; project administration, T.G. and K.T..; funding acquisition, K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Medical University of Plovdiv, Bulgaria, grant number: НО-11/2021 (Р8540/2021); grant name: “Epigenetic and neurofunctional profile of insomnia phenotypes“.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Plovdiv, protocol code 3/20.05.2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHI |

Apnea-hypopnea index |

| AIR |

Right anterior insula |

| BDI |

Beck depression inventory |

| CID |

Chronic insomnia disorder |

| DCM |

Dynamic casual modeling |

| DLPFC |

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| DMN |

Default mode network |

| DMPFC |

Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex |

| EC |

Effective connectivity |

| ECN |

Executive control network |

| EPI |

Echo Planar Imaging |

| ESS |

Epworth sleepiness scale |

| FC |

Functional connectivity |

| HC |

Healthy controls |

| Hippocamp R |

Right hippocamps |

| ICSD-III TR |

International classification of sleep disorders, third edition. Text revision |

| ISI |

Insomnia severity index |

| MNI |

Montreal Neurological Institute |

| MPFC |

Medial prefrontal cortex |

| N1 |

Stage 1 Non-REM Sleep |

| N2 |

Stage 2 Non-REM Sleep |

| N3 |

Stage 3 Non-REM Sleep |

| ODI |

Oxygen desaturation index |

| PCC |

Posterior cingulate cortex |

| PLMS |

Periodic limb movement syndrome |

| PSG |

Polysomnography |

| REM |

Rapid eye movement sleep |

| ROI |

Region of interest |

| Rs-fMRI |

Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| SE |

Sleep efficiency |

| SN |

Salience network |

| SOL |

Sleep onset latency |

| SPM |

Statistical Parametric Mapping |

| TE |

Echo time |

| TIB |

Time in bed |

| TR |

Relaxation time |

| WASO |

Wake after sleep onset |

References

- Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev 2002;6:97–111. [CrossRef]

- Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders. Chest 2014;146:1387–94.

- Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W. Prevalence, Course, and Comorbidity of Insomnia and Depression in Young Adults. Sleep 2008;31:473–80. [CrossRef]

- Dressle RJ, Riemann D. Hyperarousal in insomnia disorder: Current evidence and potential mechanisms. J Sleep Res 2023;32. [CrossRef]

- Perlis M, Gehrman P, Pigeon WR, Findley J, Drummond S. Neurobiologic Mechanisms in Chronic Insomnia. Sleep Med Clin 2009;4:549–58. [CrossRef]

- Gehrman P, Sengupta A, Harders E, Ubeydullah E, Pack AI, Weljie A. Altered diurnal states in insomnia reflect peripheral hyperarousal and metabolic desynchrony: A preliminary study. Sleep 2018;41. [CrossRef]

- Hertenstein E, Nissen C, Riemann D, Feige B, Baglioni C, Spiegelhalder K. The exploratory power of sleep effort, dysfunctional beliefs and arousal for insomnia severity and polysomnography-determined sleep. J Sleep Res 2015;24:399–406. [CrossRef]

- Li G, Zhang X, Zhang J, Wang E, Zhang H, Li Y. Magnetic resonance study on the brain structure and resting-state brain functional connectivity in primary insomnia patients. Medicine (United States) 2018;97. [CrossRef]

- Riemann D, Voderholzer U, Spiegelhalder K, Hornyak M, Buysse DJ, Nissen C, et al. Chronic Insomnia and MRI-Measured Hippocampal Volumes: A Pilot Study. Sleep 2007;30:955–8. [CrossRef]

- Marques DR, Gomes AA, Caetano G, Castelo-Branco M. Insomnia disorder and brain’s default-mode network. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2018;18:1–4.

- Goulden N, Khusnulina A, Davis NJ, Bracewell RM, Bokde AL, McNulty JP, et al. The salience network is responsible for switching between the default mode network and the central executive network: Replication from DCM. Neuroimage 2014;99:180–90. [CrossRef]

- Yu S, Guo B, Shen Z, Wang Z, Kui Y, Hu Y, et al. The imbalanced anterior and posterior default mode network in the primary insomnia. J Psychiatr Res 2018;103:97–103. [CrossRef]

- Kim YB, Kim N, Lee JJ, Cho SE, Na KS, Kang SG. Brain reactivity using fMRI to insomnia stimuli in insomnia patients with discrepancy between subjective and objective sleep. Sci Rep 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Wang K, Liu JH, Wang YP. Altered Default Mode and Sensorimotor Network Connectivity With Striatal Subregions in Primary Insomnia: A Resting-State Multi-Band fMRI Study. Front Neurosci 2018;12. [CrossRef]

- Elberse JD, Saberi A, Ahmadi R, Changizi M, Bi H, Hoffstaedter F, et al. The interplay between insomnia symptoms and Alzheimer’s disease across three main brain networks. Sleep 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wei Y, Leerssen J, Wassing R, Stoffers D, Perrier J, Van Someren EJW. Reduced dynamic functional connectivity between salience and executive brain networks in insomnia disorder. J Sleep Res 2020;29. [CrossRef]

- Baglioni C, Spiegelhalder K, Regen W, Feige B, Nissen C, Lombardo C, et al. Insomnia disorder is associated with increased amygdala reactivity to insomnia-related stimuli. Sleep 2014;37:1907–17. [CrossRef]

- Dong X, Qin H, Wu T, Hu H, Liao K, Cheng F, et al. Rest but busy: Aberrant resting-state functional connectivity of triple network model in insomnia. Brain Behav 2018;8. [CrossRef]

- Stephan KE, Friston KJ. Analyzing effective connectivity with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci 2010;1:446–59. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Dong M, Yin Y, Hua K, Fu S, Jiang G. Aberrant effective connectivity of the right anterior insula in primary insomnia. Front Neurol 2018;9. [CrossRef]

- Pang R, Guo R, Wu X, Hu F, Liu M, Zhang L, et al. Altered regional homogeneity in chronic insomnia disorder with or without cognitive impairment. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2018;39:742–7. [CrossRef]

- Feng J, Zhang Q, Zhang C, Wen Z, Zhou X. The Effect of sequential bilateral low-frequency rTMS over dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on serum level of BDNF and GABA in patients with primary insomnia. Brain Behav 2019;9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Huang X, Wang C, Liang K. Alteration of gamma-aminobutyric acid in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of individuals with chronic insomnia: a combined transcranial magnetic stimulation-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Sleep Med 2022;92:34–40. [CrossRef]

- Bechara A, Tranel D, Damasio H. Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions. vol. 123. 2000.

- Narayanan NS, Laubach M. Top-Down Control of Motor Cortex Ensembles by Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex. Neuron 2006;52:921–31. [CrossRef]

- Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, Raichle ME. Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: Relation to a default mode of brain function. n.d.

- Jilka SR, Scott G, Ham T, Pickering A, Bonnelle V, Braga RM, et al. Damage to the salience network and interactions with the default mode network. Journal of Neuroscience 2014;34:10798–807. [CrossRef]

- Chen MC, Chang C, Glover GH, Gotlib IH. Increased insula coactivation with salience networks in insomnia. Biol Psychol 2014;97:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Espie CA. Revisiting the Psychobiological Inhibition Model: a conceptual framework for understanding and treating insomnia using cognitive and behavioural therapeutics (CBTx). J Sleep Res 2023;32. [CrossRef]

- Espie CA, Broomfield NM, MacMahon KMA, Macphee LM, Taylor LM. The attention-intention-effort pathway in the development of psychophysiologic insomnia: A theoretical review. Sleep Med Rev 2006;10:215–45. [CrossRef]

- Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. 2008.

- Li C, Dong M, Yin Y, Hua K, Fu S, Jiang G. Aberrant effective connectivity of the right anterior insula in primary insomnia. Front Neurol 2018;9:317.

- Long Z, Cheng F. Age effect on functional connectivity changes of right anterior insula after partial sleep deprivation. Neuroreport 2019;30:1246–50. [CrossRef]

- Xia G, Hu Y, Chai F, Wang Y, Liu X. Abnormalities of the Default Mode Network Functional Connectivity in Patients with Insomnia Disorder. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2022;2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Ye Y, Li S, Jiang G. Altered functional connectivity of anterior cingulate cortex in chronic insomnia: A resting-state fMRI study. Sleep Med 2023;102:46–51. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Chen R, Guan M, Wang E, Qian T, Zhao C, et al. Disrupted brain network topology in chronic insomnia disorder: A resting-state fMRI study. Neuroimage Clin 2018;18:178–85. [CrossRef]

- Bagherzadeh-Azbari S, Khazaie H, Zarei M, Spiegelhalder K, Walter M, Leerssen J, et al. Neuroimaging insights into the link between depression and Insomnia: A systematic review. J Affect Disord 2019;258:133–43. [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Li B, Wang S, Chen C, Liu Z, Ji Y, et al. The brain in chronic insomnia and anxiety disorder: a combined structural and functional fMRI study. Front Psychiatry 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Edwards LS, Ganesan S, Tay J, Elliott ES, Misaki M, White EJ, et al. Increased Insular Functional Connectivity During Repetitive Negative Thinking in Major Depression and Healthy Volunteers 2024. [CrossRef]

- Barbey AK, Koenigs M, Grafman J. Dorsolateral prefrontal contributions to human working memory. Cortex 2013;49:1195–205. [CrossRef]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. vol. 51. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Wu P, Wang C, Wei M, Li Y, Xue Y, Li X, et al. Prefrontal cortex functional connectivity changes during verbal fluency test in adults with short-term insomnia disorder: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. Front Neurosci 2023;17. [CrossRef]

- Boon ME, van Hooff MLM, Vink JM, Geurts SAE. The effect of fragmented sleep on emotion regulation ability and usage. Cogn Emot 2023;37:1132–43. [CrossRef]

- Carney CE, Harris AL, Falco A, Edinger JD. The relation between insomnia symptoms, mood and rumination about insomnia symptoms. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2013;9:567–75. [CrossRef]

- Jansson-Fröjmark M, Norell-Clarke A, Linton SJ. The role of emotion dysregulation in insomnia: Longitudinal findings from a large community sample. Br J Health Psychol 2016;21:93–113. [CrossRef]

- Patel M, Teferi M, Gura H, Casalvera A, Lynch KG, Nitchie F, et al. Interleaved TMS/fMRI shows that threat decreases dlPFC-mediated top-down regulation of emotion processing. NPP—Digital Psychiatry and Neuroscience 2024;2. [CrossRef]

- Nofzinger EA, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Price JC, Miewald JM, David Kupfer BJ. Functional Neuroimaging Evidence for Hyperarousal in Insomnia. vol. 161. 2004.

- Yang S, Kong X, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Li X, Ge YJ. The impact of insomnia on prefrontal activation during a verbal fluency task in patients with major depressive disorder: A preliminary fNIRS study. Sleep Med 2025;125:114–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Su L, Da H, Ji B, Xiao Q, Shi H. The role of dorsolateral and orbitofrontal cortex in depressed with insomniacs population: a large-scale fNIRS study. Current Psychology 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).