Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

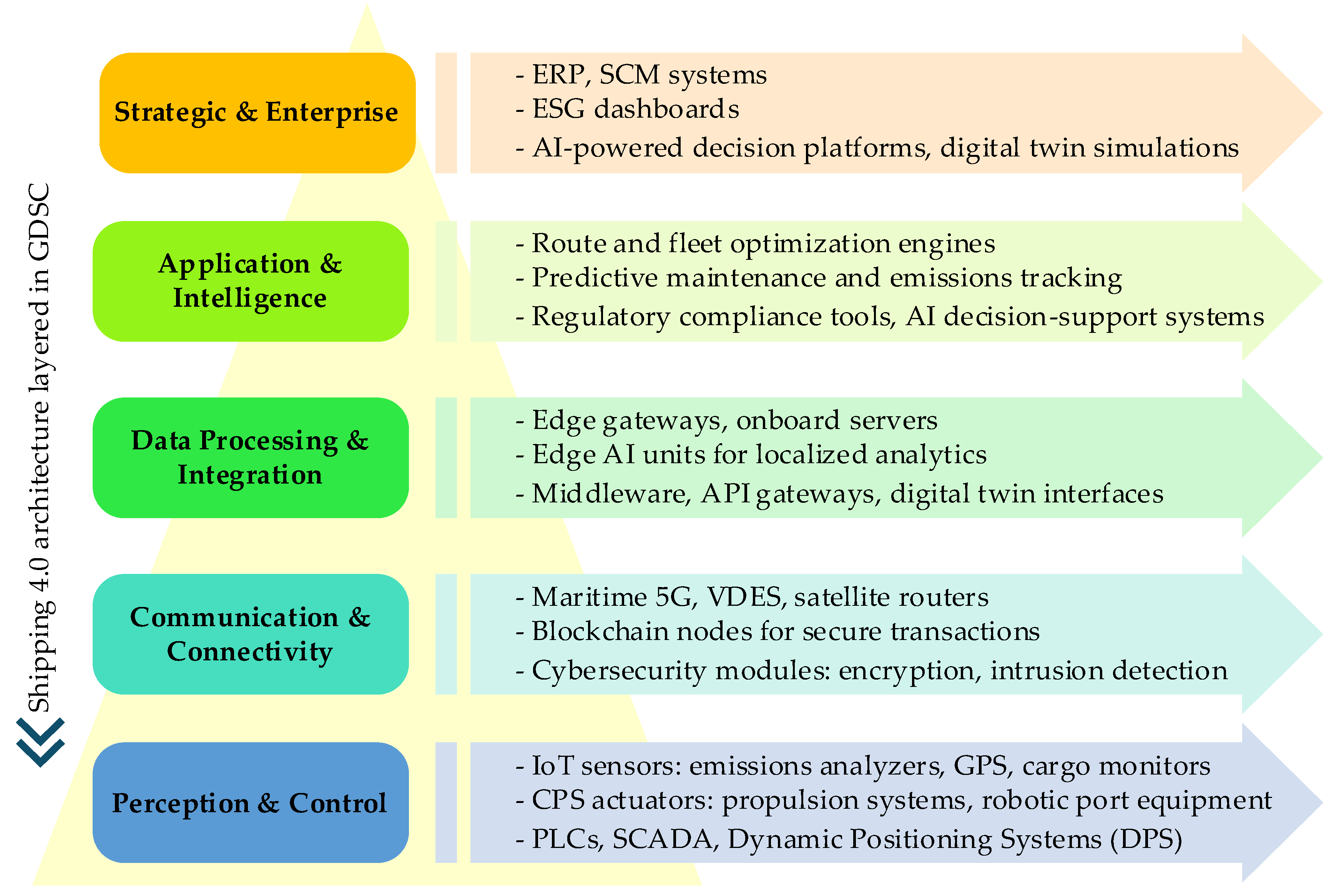

- Proposing a five-layer Industry 4.0 architecture tailored to GDSCs.

- Developing a conceptual-comparative framework contrasting traditional navigation and monitoring systems with Industry 4.0-enabled systems across 14 performance dimensions.

- Introducing a human operational readiness model to support the transition from manual operations to data-driven supervisory roles; and

- Presenting a phased implementation roadmap that aligns technology deployment with workforce adaptation.

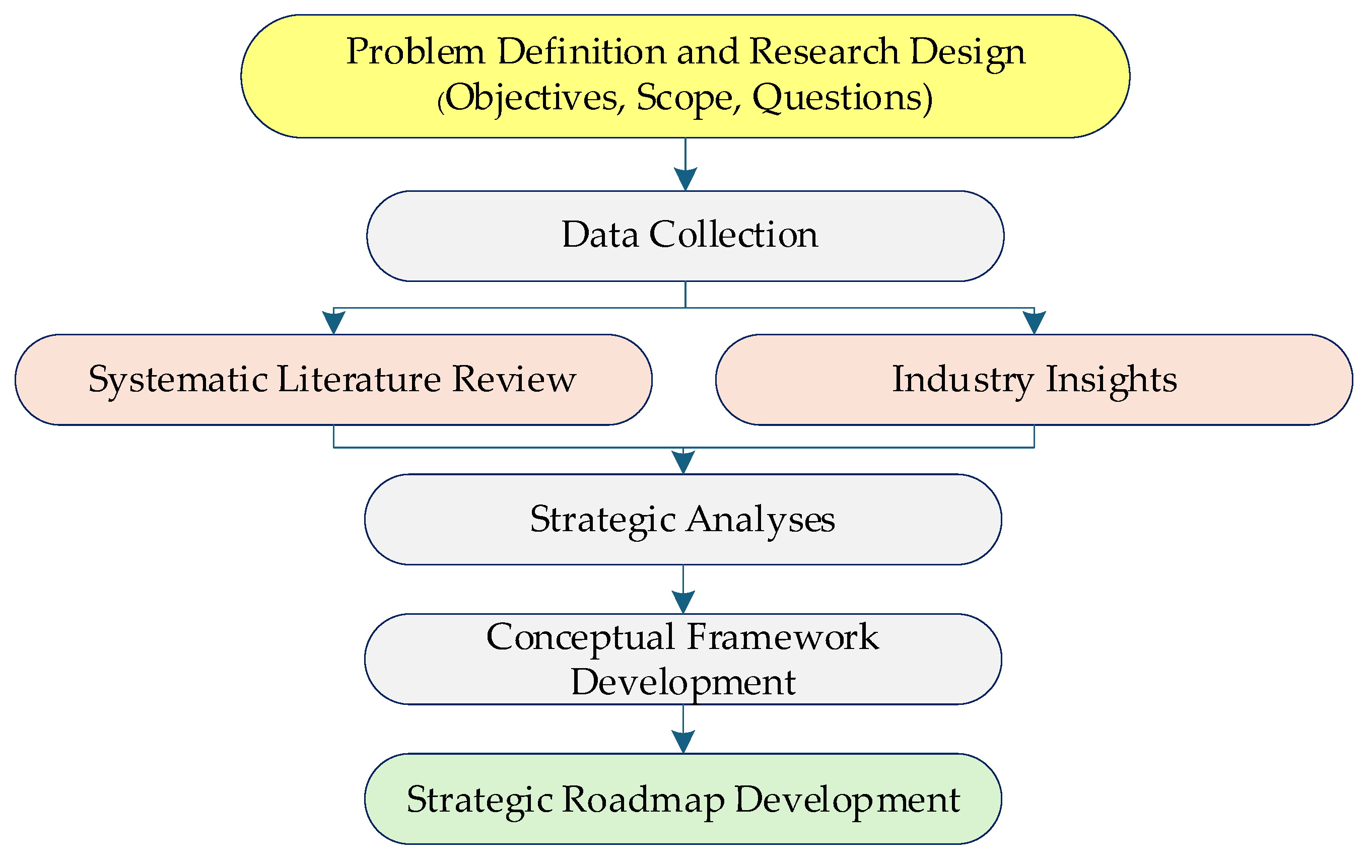

Methodology

2. Industry 4.0 Framework for GDSCs

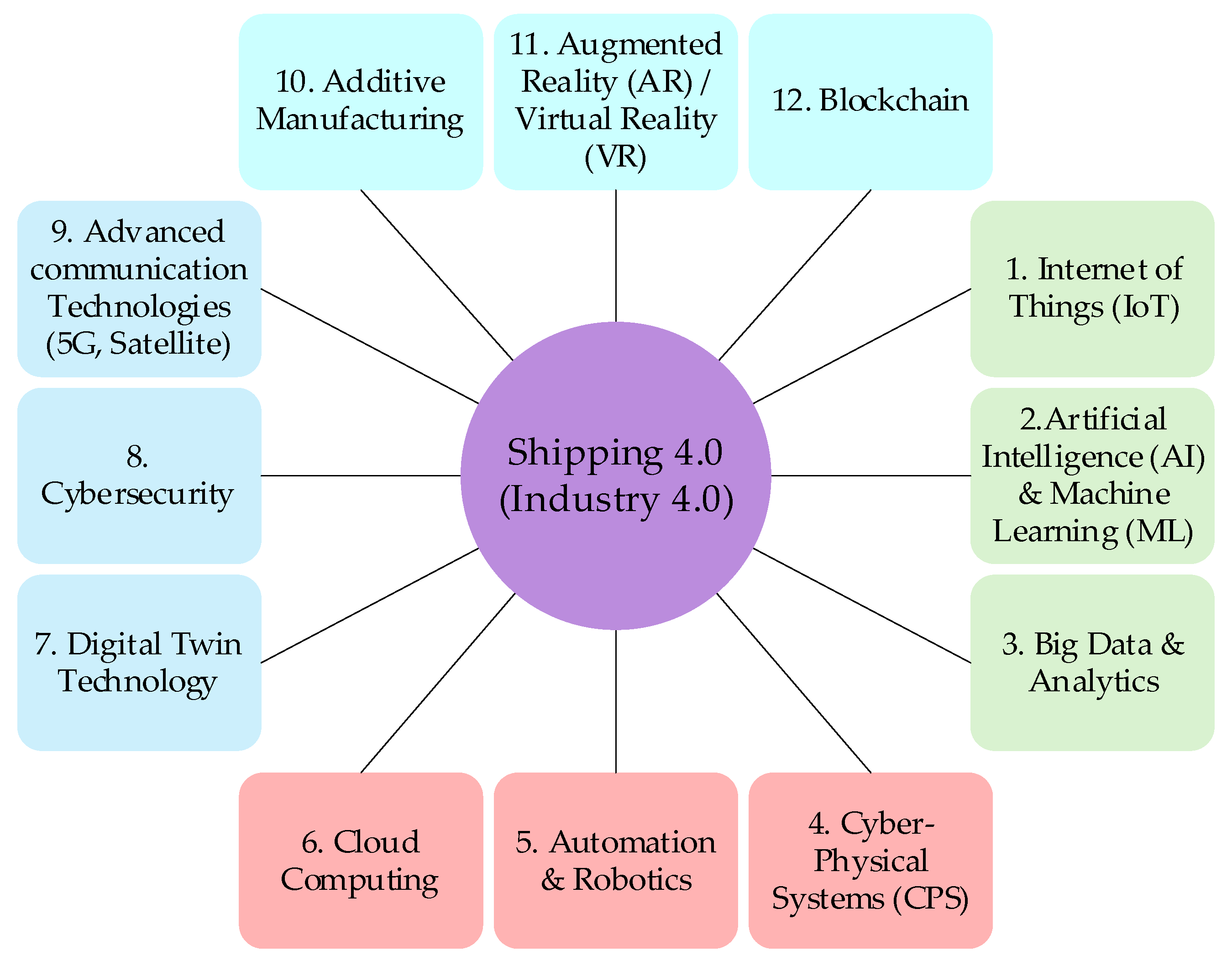

2.1. Shipping 4.0 Components and Applications

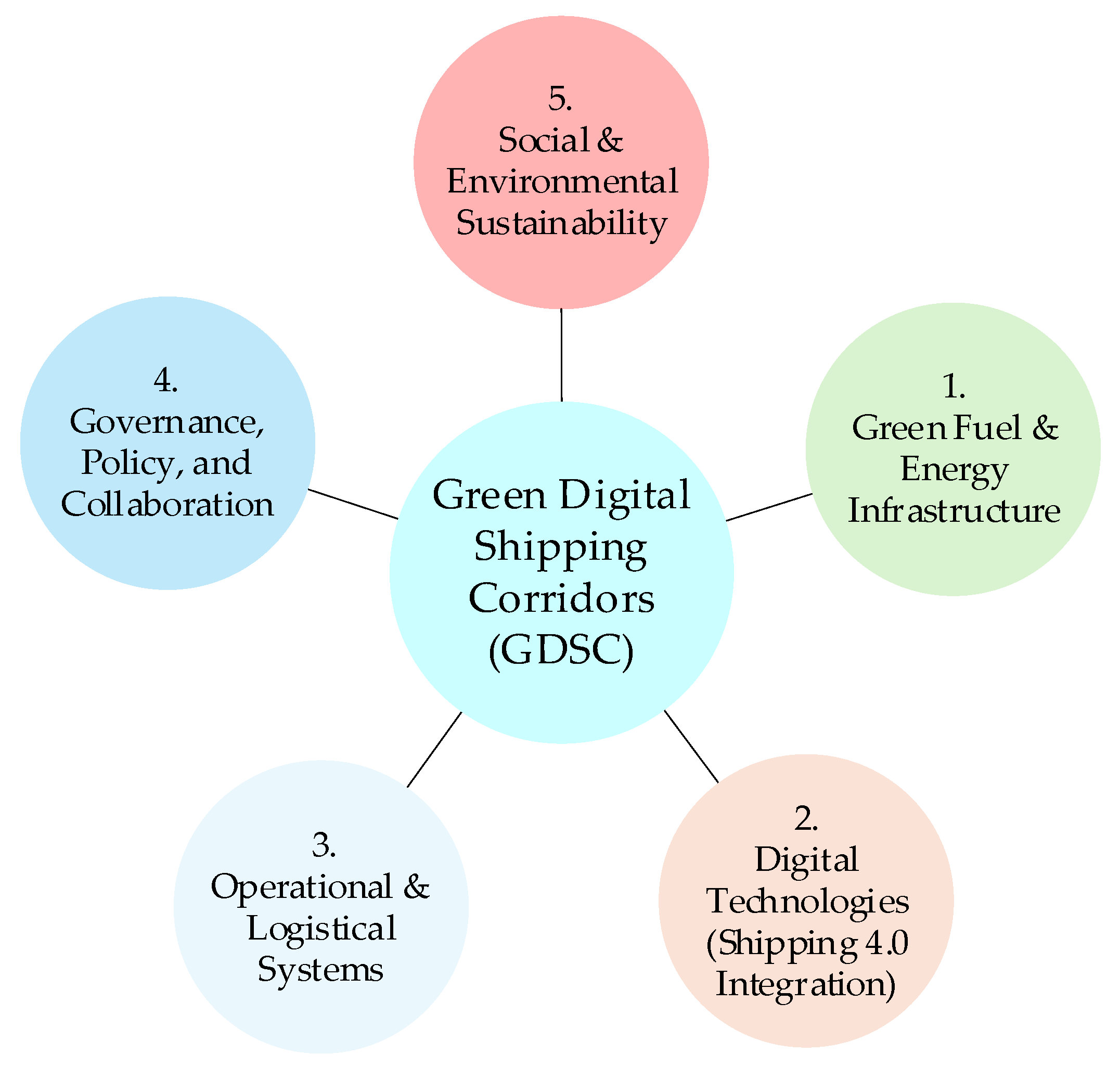

2.2. Green Digital Shipping Corridors (GDSC)

2.3. Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs Industry 4.0 Systems

- Automation and optimization through AI and CPS,

- Digital supervisory roles for crew members,

- Modular scalability and software-driven adaptability,

- Advanced communication via 5G, satellite, and blockchain,

- Integrated cybersecurity and automated compliance protocols.

2.4. Shipping 4.0 Architecture in GDSC

2.4.1. Perception & Control Layer (IoT, CPS)

2.4.2. Communication & Connectivity Layer (IoT, CPS, Edge)

2.4.3. Data Processing & Integration Layer (Edge AI, CPS, Cloud)

2.4.4. Application & Intelligence Layer (Edge AI, Cloud)

2.4.5. Strategic & Enterprise Layer (Cloud)

3. Human Factor’s Operational Readiness

3.1. Necessity and Context

- Digital literacy for navigation of complex systems and robust cybersecurity awareness,

- AI supervision skills to understand machine learning limitations and decision-making boundaries, and

- Cognitive resilience to sustain performance under operational stress.

3.2. Innovative Perspective

- Bridging Traditional and Future Skills – Each competency maintains a link to its STCW origin while extending into AI-enabled, digitalized workflows.

- Human–Technology Synergy – Competencies are defined to position the human operator as a strategic decision-maker in human-in-the-loop (HITL) systems, ensuring oversight for AI recommendations and ethical considerations.

- Integrated Safety and Cybersecurity Readiness – The framework embeds multi-layered assurance measures, including HITL protocols for safety-critical actions, escalation pathways for low-confidence AI outputs, zero-trust cybersecurity architectures, penetration testing, and explainable AI outputs for transparency.

- Sustainability and Green Competence – Environmental stewardship is integrated into technical and operational competencies, aligning with decarbonization targets and green digital shipping corridor initiatives.

3.3. Human-Machine Interface (HMI) and Operational Design Considerations

- Adaptive HMI designs that adjust to operator skill levels and situational contexts,

- Multimodal feedback systems (visual, auditory, haptic) to enhance situational awareness, and

- Unified decision dashboards integrating AI predictions with real-time sensor inputs, ensuring transparency and rapid escalation options for human intervention.

3.4. Continuous Improvement and Adaptation

- Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) to refine AI performance using operational inputs,

- Combined automated and human evaluation protocols to assess both objective metrics and contextual decision quality, and

- Adaptive regulatory alignment to ensure that safety and performance standards evolve alongside technological capabilities.

3.5. Research Contribution

- Establishing a taxonomy of Shipping 4.0 competencies that is internationally aligned and operationally actionable.

- Offering a training and assessment blueprint that bridges human factors research with AI, HMI design, and maritime safety science.

- Providing a foundation for Key Performance Indicator (KPI)-linked evaluation models, enabling empirical study of competency impacts on operational efficiency, safety performance, and environmental compliance.

4. Strategic Analysis

4.1. Dynamic Operating Analysis

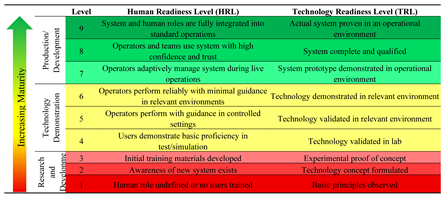

4.2. Upgraded TRL–HRL Analysis

| Shipping 4.0 Layer | Technology (TRL) | Human (HRL) | Trust & Explainability | Cognitive Load | Human-AI Integration Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception & Control | TRL 8–9: Mature IoT/CPS | HRL 5–6: Operational proficiency | Moderate (sensor fusion is interpretable) | Medium (multiple alert systems) | Suitable for deployment with monitoring |

| Communication & Connectivity | TRL 7–8: VDES, 5G, blockchain | HRL 3–4: Limited training in protocols | Low to Medium (blockchain is abstract) | Medium | Needs simulation and comms drills |

| Data Processing & Integration | TRL 6–7: Edge AI, middleware | HRL 2–3: Early familiarity | Low (AI decisions are opaque) | High | Not ready; needs transparency tools and training |

| Application & Intelligence | TRL 5–6: Predictive routing, emissions AI | HRL 2–3: Basic dashboard use | Low (black-box AI) | High | High risk; phased rollout with strong oversight |

| Strategic & Enterprise Layer | TRL 4–5: Digital twin planning, ESG dashboards | HRL 1–2: Minimal exposure | Very Low | Variable | Focus on training planners and officers |

5. Implementation Roadmap for GDSCs’ Human Factor

5.1. Implementation Phases

5.2. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

- Framework Function – A structured alignment of competencies to measurable outcomes, enabling comparative analysis across operators, vessels, and organizational units.

- Measurement Package – A standardized scoring and benchmarking system that integrates objective data streams (e.g., system logs, operational performance metrics) and subjective assessments (e.g., peer review, expert evaluation).

- Competency–KPI Alignment – Each KPI directly maps to a defined competency domain in the competency table.

- Mixed-Method Measurement – Integration of quantitative metrics (time-to-decision, system error rate, environmental compliance percentage) with qualitative indicators (leadership adaptability, decision justification quality).

- Benchmark-Driven Scoring – All KPIs are measured against established industry benchmarks (e.g., IMO guidelines, company safety standards, STCW requirements).

- Context-Aware Normalization – KPI results are adjusted for operational context variables such as voyage type, weather severity, and crew experience.

- Continuous Feedback Integration – The evaluation feeds into a reinforcement loop that updates training priorities and AI system design.

- Critical Failure: Does not meet minimum safety or operational standards

- Below Standard: Significant gaps; requires corrective action before phase transition

- Meets Minimum Standard: Acceptable performance; can progress with close monitoring

- Exceeds Standard: Demonstrates strong performance with minor refinements needed

- Best-in-Class: Optimal performance; serves as a benchmark for fleet-wide scaling

6. Conclusions and Future Work

6.1. Key Findings on Technology-Human Alignment

6.2. Strategic Implications

6.3. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability Statement

References

- Aiello, G.; Giallanza, A.; Mascarella, G. Towards shipping 4.0. A preliminary gap analysis. Procedia Manufacturing 2020, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alternative Fuels Data Center: Hydrogen Basics. (n.d.). Www.Afdc.Energy.Gov. Retrieved December 14, 2019, from http://www.afdc.energy.gov/fuels/hydrogen_basics.html.

- Avgeridis, L.; Lentzos, K.; Skoutas, D.; Emiris, I.Z. (2023). Time Series Analysis for Digital Twins in Green Shipping. SNAME 8th International Symposium on Ship Operations, Management and Economics, SOME 2023. [CrossRef]

- Balador, A.; Kouba, A.; Cassioli, D.; Foukalas, F.; Severino, R.; Stepanova, D.; Agosta, G.; Xie, J.; Pomante, L.; Mongelli, M. Wireless communication technologies for safe cooperative cyber physical systems. Sensors 2018, 18, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum-Talmor, P.; Kitada, M. Industry 4.0 in shipping: Implications to seafarers’ skills and training. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 2022, 13, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengue, A.A.; Alavi-Borazjani, S.A.; Chkoniya, V.; Cacho, J.L.; Fiore, M. Prioritizing Criteria for Establishing a Green Shipping Corridor Between the Ports of Sines and Luanda Using Fuzzy AHP. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borromeo, G.A. Shaping the Future of Seafaring in an Age of Safer, Smarter, and Greener Shipping. Maritime Digitalization and Decarbonization 2024, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, S.; Pike, T.; Bailey, M.M. A proposed framework for artificial intelligence safety and technology readiness assessments for national security applications. OSF Preprints 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Dumitrescu, R.; Falkowski, T.; Papamichail, G.; Zota, N.-R. Enhancing SME resilience through artificial intelligence and strategic foresight: A framework for sustainable competitiveness. Technology in Society 2025, 81, 102835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyhun, G.Ç. Recent developments of artificial intelligence in business logistics: A maritime industry case. Digital Business Strategies in Blockchain Ecosystems: Transformational Design and Future of Global Business 2019, 343–353.

- Diaz, S.; Al Hammadi, N.; Seif El Nasr, A.; Villasuso, F.; Prakash, S.; Baobaid, O.; Gracias, D.; Mills, R. (2023). Green Corridor: A Feasible Option for the UAE Decarbonization Pathway, Opportunities & Challenges. Society of Petroleum Engineers - ADIPEC, ADIP 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dolatabadi, S.H.; Masodzadeh, P.G.; Ishaq, H.; Crawford, C. Green shipping corridors: An overview of Pacific Northwest region and key ports. Ocean & Coastal Management 2025, 269, 107745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlik, I.; Miller, T.; Cembrowska-Lech, D.; Krzemińska, A.; Złoczowska, E.; Nowak, A. Navigating the sea of data: a comprehensive review on data analysis in maritime IoT applications. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial Team. (2024, December 23). WMU launches training program on alternative shipping fuels. SAFETY4SEA. https://safety4sea.com/wmu-launches-training-program-on-alternative-shipping-fuels/.

- Editors, M. Feasibility of Green Shipping Corridors. Sustainability 2023, 16, 9563. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/21/9563.

- Editors, S. (2023a). Green Shipping Corridors: Opportunities and Challenges. Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-39936-7_31.

- Editors, S. (2023b). Supportive Policies for Green Shipping Corridors. Sustainability Science, 16, 300. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-39936-7_31.

- Emad, G.R. Study of the Effectiveness of Trainings for Port Logistics Workers in Improving the Safety Level of Ports (Case study: Chabahar Port, Iran). Journal of Maritime Research 2015, 12, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Emad, G.R. (2020). Shipping 4.0 disruption and its impending impact on maritime education. In Disrupting Business as Usual in Engineering Education, 31st Annual Conference of the Australasian Association for Engineering Education (AAEE 2020): (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 202–207). Engineers Australia.

- Emad, G.R.; Enshaei, H.; Ghosh, S. Identifying seafarer training needs for operating future autonomous ships: a systematic literature review. Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs 2022, 14, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emad, G.R.; Khabir, M.; Shahbakhsh, M. (2020a). Shipping 4.0 and training seafarers for the future autonomous and unmanned ships. Proceedings of the 21th Marine Industries Conference (MIC2019), Qeshm Island, Iran, 1–2.

- Emad, G.R.; Khabir, M.; Shahbakhsh, M. (2020b). The Role of Maritime Logistics in Sustaining the Future of Global Energy: The Case of Hydrogen. 21st Marine Industry Conference.

- Emad, G.R.; Oxford, I. Rethinking maritime education and training. Proceedings of the 16th International Maritime Lecturers Association Conference 2008, 91–98.

- Emad, G.R.; Shahbakhsh, M. (2022a). Digitalization Transformation and its Challenges in Shipping Operation: The case of seafarer’s cognitive human factor. Human Factors in Transportation, 60. [CrossRef]

- Emad, G.R.; Shahbakhsh, M. (2022b). Digitalization Transformation and its Challenges in Shipping Operation: The case of seafarer’s cognitive human factor. Human Factors in Transportation, 60. [CrossRef]

- Emad, G.R.; Shahbakhsh, M.; Cahoon, S. (2024). Seafarers’ Challenges in the Transition Period to Autonomous Shipping: Shipping Industry’s Perspective.

- Emad, G.R.; Shahbakhsh, M.; Khabir, M. (2025). Artificial Intelligence and its Transformative Impact in Shaping the Maritime Industry. In D. Rajesh & B. Svilicic (Eds.), International Association of Maritime Universities Conference. International Association of Maritime Universities (IAMU).

- Eom, J.O.; Yoon, J.H.; Yeon, J.H.; Kim, S.W. Port Digital Twin Development for Decarbonization: A Case Study Using the Pusan Newport International Terminal. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, A.B.; Mohammed, S.L.; Khan, I.; Sadiq, A.S.; Alkazemi, B.; Pillai, P.; Choi, B.J. Industry 4.0: Architecture and equipment revolution. Comput. Mater. Continua 2021, 66, 1175–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yang, Z. Analysing seafarer competencies in a dynamic human-machine system. Ocean & Coastal Management 2023, 240, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrero-Molina, M.-I.; Vásquez-Suárez, Y.-A.; Valdés-Mosquera, D.-M. Smart, green, and sustainable: unveiling technological trajectories in maritime port operations. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 47713–47723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güner, A. (2022). General AI vs. Narrow AI: 2022 Guide.

- Han, S.; Wang, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, Y. Towards the Human–Machine Interaction: Strategies, Design, and Human Reliability Assessment of Crews’ Response to Daily Cargo Ship Navigation Tasks. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, H.A.H.; See, J.E.; Savage-Knepshield, P.A. Human readiness levels and Human Views as tools for user-centered design. Systems Engineering 2024, 27, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heering, D. (2025). Rethinking Seafarer Training for the Digital Age. In Maritime Cybersecurity (pp. 29–53). Springer.

- Helmann, A.; Deschamps, F.; Loures, E. de F. R. Reference architectures for industry 4.0: Literature review. Transdisciplinary Engineering for Complex Socio-Technical Systems–Real-Life Applications 2020, 171–180.

- IMO. (2020a). Further consideration of concrete proposals to improve the operational energy efficiency of existing ships, with a view to developing draft amendments to chapter 4 of MARPOL annex vi and associated guidelines, as appropriate (ISWG-GHG 7/2/6). https://www.ics-shipping.org/docs/default-source/Submissions/IMO/proposal-for-a-goal-based-operational-measure.pdf?sfvrsn=2.

- IMO. (2020b). GHG Emissions. http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/PollutionPrevention/AirPollution/Pages/GHG-Emissions.aspx.

- IMO, S. (2020c). Fourth greenhouse gas study 2020. International Maritime Organization London, UK.

- Iqbal, A.B.; Tariq, F.; Sumra, I.A.; Rasheed, K. The Digital Evolution of the Maritime Industry: Unleashing the Power of IoT and Cloud Computing. Journal of Computing & Biomedical Informatics 2025, 9.

- Jokioinen, E. (2016). Remote and Autonomous Ship-The next steps. https://www.rolls-royce.com/~/media/Files/R/Rolls-Royce/documents/customers/marine/ship-intel/aawa-whitepaper-210616.pdf.

- Joshva, J.; Diaz, S.; Kumar, S.; Suboyin, A.; AlHammadi, N.; Baobaid, O.; Villasuso, F.; Konig, M.; Binamro, A.; Saputelli, L. (2024). Navigating the Future of Maritime Operations: The AI Compass for Ship Management. ADIPEC. [CrossRef]

- Kavallieratos, G.; Diamantopoulou, V.; Katsikas, S.K. Shipping 4.0: Security requirements for the cyber-enabled ship. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2020, 16, 6617–6625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavallieratos, G.; Katsikas, S.; Gkioulos, V. Modelling shipping 4.0: A reference architecture for the cyber-enabled ship. Asian Conference on Intelligent Information and Database Systems 2020, 202–217. [Google Scholar]

- Khabir, M.; Emad, G.R.; Shahbakhsh, M. Toward future green shipping: resilience and sustainability indicators. Proceedings of the 10th Asian Logistics Round Table Conference (ALRT) 2020, 391–417. [Google Scholar]

- Khabir, M.; Emad, G.R.; Shahbakhsh, M.; Dulebenets, M.A. A Strategic Pathway to Green Digital Shipping. Logistics 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Yasmin, M.; Khan, M.H.H. Alternative Fuels – Prospects for the Shipping Industry. TransNav, the International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation 2021, 15, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.; Yasmin, M.; Khan, M.H.H. Alternative Fuels – Prospects for the Shipping Industry. TransNav, the International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation 2021, 15, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

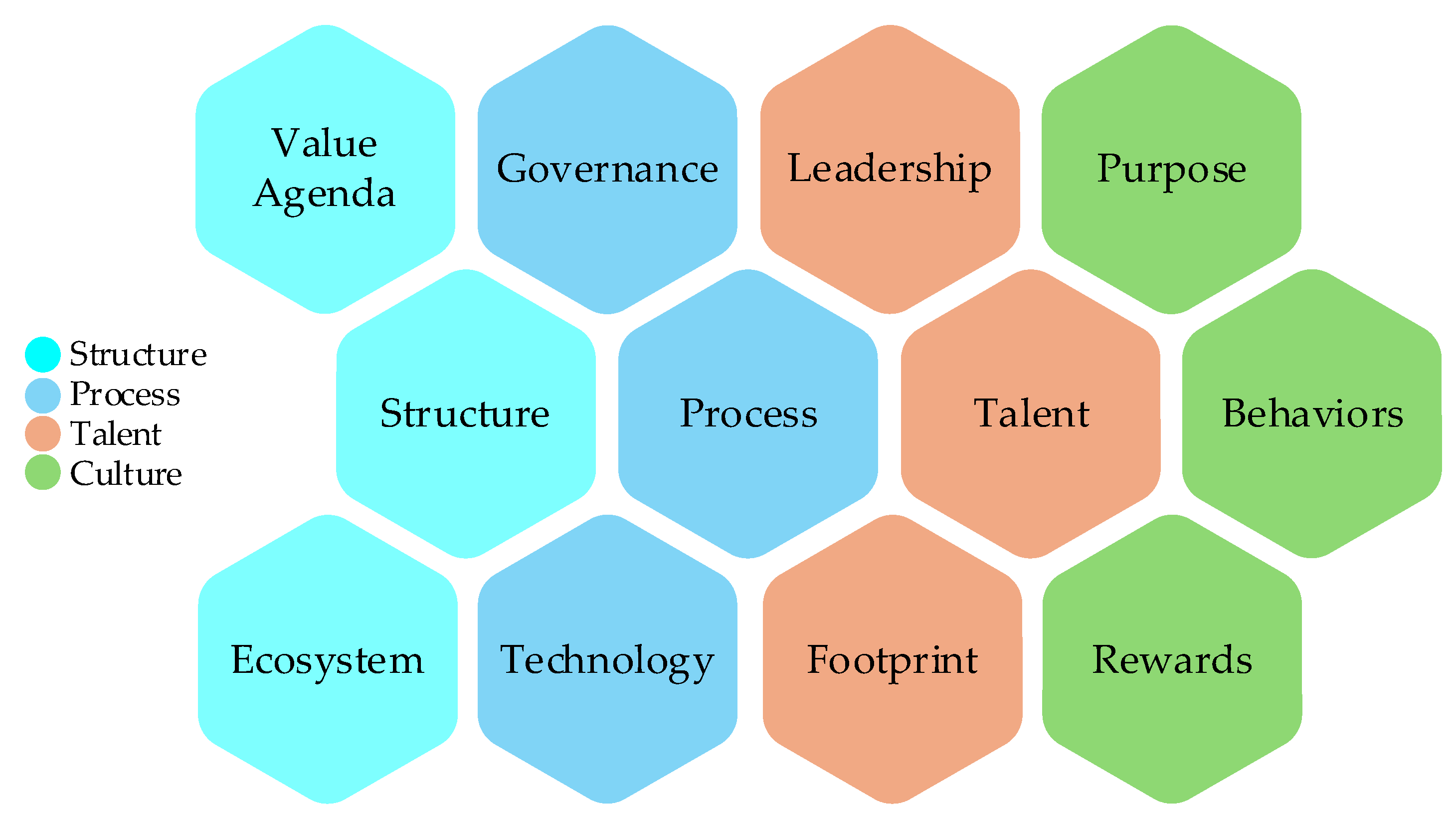

- Krivkovich, A.; Di Lodovico, A.; Weddle, B.; Maor, D.; Mahadevan, D.; Steele, R. (2025). A new operating model for a new world.

- Lee, J.; Sim, M.; Kim, Y.; Lim, H.; Lee, C. Strategizing Artificial Intelligence Transformation in Smart Ports: Lessons from Busan’s Resilient AI Governance Model. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2025, 13, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchenko, D.; Georgiievskyi, І.; Bielikova, M. (2023). Challenges and Developments in the Public Administration of Autonomous Shipping.

- Malau, A.G.; Purnama, C.; Simanjuntak, M.B. Developing Competency-Based Maritime Education for the Digital Age. Journal of Maritime Research 2025, 22, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Martelli, M.; Virdis, A.; Gotta, A.; Cassarà, P.; Di Summa, M. An outlook on the future marine traffic management system for autonomous ships. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 157316–157328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEPC; R (2023). 2023 IMO strategy on reduction of GHG emissions from SHIPS.

- Nakagawa, E.Y.; Antonino, P.O.; Schnicke, F.; Capilla, R.; Kuhn, T.; Liggesmeyer, P. Industry 4.0 reference architectures: State of the art and future trends. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2021, 156, 107241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.C.; Emad, G.R.; Fei, J. Theorizing seafarers’ participation and learning in an evolving maritime workplace: an activity theory perspective. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs 2023, 22, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasaruddin, M.M.; Emad, G.R. (2019). Preparing Maritime Professionals for their Future Roles in a Digitalized Era: Bridging the blockchain skills gap in maritime education and training. 87–97.

- Rajapakse, R.; Emad, G.R. A Review of Technology, Infrastructure and Human Competence of Maritime Stakeholders on the Path Towards Autonomous Short Sea Shipping. 20th International Association of Maritime Universities Annual General Assembly 2019, 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Rodseth, O.; Burmeister, H.-C. (2015). Report D10. 2: New ship design for autonomous vessels. Maritime Unmanned Navigation through Intelligence in Networks (MUNIN).

- Rub, A. The Role of Artificially Intelligent ERP Systems in Automating Business Processes, Enhancing Decision-Making, and Transparency and Compliance within Organizations: A Case Study for Private Sector Companies. Journal of Business and Management Research 2025, 4, 1102–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, G.; Russi-Vigoya, M.N. (2021). Technology Readiness Level (TRL) as the foundation of Human Readiness Level (HRL). Sage Journals: Ergonomics in Design: The Quarterly of Human Factors Applications.

- Shahbakhsh, M.; Emad, G.R.; Cahoon, S. Industrial revolutions and transition of the maritime industry: The case of Seafarer’s role in autonomous shipping. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics 2022, 38, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotvik, D.A.; Endresen, Ø.; Eide, M.; Skåre, O.G.; Hustad, H. (2022). Insight on green shipping corridors From policy ambitions to realization. Nordic Roadmap Publication, 3-A/1/2022.

- Song, Z.Y.; Chhetri, P.; Ye, G.; Lee, P.T.W. (2023). Green maritime logistics coalition by green shipping corridors: a new paradigm for the decarbonisation of the maritime industry. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications. [CrossRef]

- Spaniol, M.J.; Rowland, N.J. AI-assisted scenario generation for strategic planning. Futures & Foresight Science 2023, 5, e148. [Google Scholar]

- Theotokatos, G.; Dantas, J.L.D.; Polychronidi, G.; Rentifi, G.; Colella, M.M. (2023a). Autonomous shipping—an analysis of the maritime stakeholder perspectives. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs, 22, 5–35.

- Theotokatos, G.; Dantas, J.L.D.; Polychronidi, G.; Rentifi, G.; Colella, M.M. (2023b). Autonomous shipping—an analysis of the maritime stakeholder perspectives. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs, 22, 5–35.

- Varelas, T.; Kaklis, D.; Varlamis, I.; Flori, A. (2023). Improving Voyage Efficiency in the Shipping 4.0 Decarbonization Era.

- Wang, X. (2025). Research on the Change of Enterprise Strategy Management Mode Empowered by Artificial Intelligence.

- Yang, T.; Cui, Z.; Alshehri, A.H.; Wang, M.; Gao, K.; Yu, K. Distributed maritime transport communication system with reliability and safety based on blockchain and edge computing. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 24, 2296–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-U.; Lee, C.-H.; Ahn, Y.-J. Developing a Competency-Based Transition Education Framework for Marine Superintendents: A DACUM-Integrated Approach in the Context of Eco-Digital Maritime Transformation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Feng, C. Evolutionary game model for decarbonization of shipping under green shipping corridor. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies 2024, 19, 2502–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Navigation & Monitoring Systems | |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Shipping 4.0 (Industry 4.0) | |

|

Definition & Architecture |

Standalone shipboard systems (radar, GPS, AIS) for individual vessels, limited integration or intelligence. | Incorporating IoT, CPS, Digital Twins, Edge AI, and Cloud platforms, corridor-wide awareness, optimization. |

|

System Integration |

Fragmented subsystems requiring manual coordination by crew. | Integrated ship, port, and corridor systems visa digital twins; interoperability all systems. |

|

Data Flow & Processing |

Linear and manual data transfer; raw sensor data interpreted by crew. | Real-time, bi-directional data with edge and cloud analytics. |

|

Automation Level |

Low automation, manual navigation, and monitoring dominate. | High automation via AI, CPS, and autonomous decision support; |

|

Decision-Making & Operator Role |

Human-centric decision-making based on experience and limited real-time. | Human-on-the-loop models: AI-assisted decision-making, with operators’ supervisory |

|

System Feedback & Learning |

Static systems; performance relies on manual updates and retrofits. | Self-learning ML systems are improving performance continuously. |

|

Fault Detection & Prediction |

Reactive fault identification; failures detected after occurrence. | Predictive maintenance via IoT and AI anomaly detection. |

|

Situational Awareness |

Crew synthesizes radar, visual, and manual data for awareness. | Multi-sensor fusion and digital twins for holistic awareness. |

|

Crew–System Interface (HMI) |

Disjointed interfaces, high cognitive load | Unified, adaptive HMIs reducing complexity. |

| Role of the Crew | Manual operators of all functions | Digital supervisors focusing on exceptions and strategy. |

|

Scalability & Adaptability |

Hardware-bound, costly upgrades. | Modular, software-driven, corridor-wide scalability. |

|

Communication Infrastructure |

Onboard communication; shore interaction through manual reporting. | Maritime 5G, satellite, and blockchain for secure low-latency exchange. |

| Cybersecurity | Limited exposure but outdated protections. | Integrated real-time cybersecurity with encryption and anomaly response. |

|

Regulatory & Compliance |

Manual reporting, inspection-based compliance. | Automated compliance via IoT, digital twins, and AI forecasting. |

| Competency Domain | Shipping 4.0 Human-Factor Competency | Relevant STCW Table / Regulation | Traditional Competency |

Shipping 4.0 Expanded Competency | Industry 4.0 Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical & Digital | Automation Systems Operation | A-II/1 (Navigation), A-III/1 (Engineering) | Use of radar, ECDIS, GNSS, and bridge equipment | Automation systems operation; AI-assisted navigation; IoT sensor integration; remote vessel control | Manage autonomous navigation & control systems |

| HMI Proficiency | A-II/1, A-V/2 | Engine monitoring, equipment maintenance | Predictive maintenance via data analytics; integration of smart engine systems; alternative fuel handling | Operate multi-modal displays & integrated systems | |

| AI & Data Analytics | A-II/1 (Use of radar/ECDIS), A-III/1 | Team coordination in emergencies | Human–machine coordination under automation; remote crisis management; AI-driven decision support | Apply predictive analytics for safety & efficiency | |

| IoT & Sensor Integration | A-II/1, A-III/1 | LNG safety procedures | Multi-fuel safety (LNG, ammonia, hydrogen); automation-based fuel monitoring | Monitor & validate sensor data in connected ships | |

| Cybersecurity Awareness | A-II/1, STCW Manila Amendments Sec. B-VIII/2 | Schedule compliance, rest hours | Cybersecurity resilience; digital diagnostics; predictive analytics maintenance scheduling | Protect critical maritime IT/OT systems | |

| Digital Navigation Tools | A-II/1 | Effective communication and task allocation | Cross-disciplinary comms between crew, automation, and shore; multicultural digital teamwork | Operate ECDIS, ARPA, GNSS, radar safely | |

| Remote Operations Control | A-II/1, A-V/2 | Chart-based route planning | Dynamic route optimization using AI, big data, and real-time environmental inputs | Control MASS from shore facilities | |

| Cognitive & Situational Awareness | Situational Awareness (SA) | A-II/1, A-V/2 | Waste & emission control | Energy efficiency management (SEEMP); decarbonization strategies; IoT-based environmental monitoring | Maintain real-time vessel/environment awareness |

| Information Processing | A-II/1 | Manual inspection & fault fixing | Cybersecurity resilience; digital diagnostics; predictive analytics maintenance scheduling | Filter & prioritize key data under automation | |

| Workload Management | A-II/1, A-V/2 | Manual cargo planning | Automated cargo monitoring systems; integration with digital twins for loading plans | Balance mental load in semi- and fully-autonomous ops | |

| Adaptability | A-II/1, A-V/2 | Leading crew operations | Change management for tech adoption; strategic thinking for autonomous operations integration | Adjust to mode changes & automation states | |

| Decision-Making & Problem-Solving | Risk-Based Decision-Making | A-II/1, A-V/2 | Risk identification, drills | Data-driven risk modelling; simulation-based training for MASS and smart port interfaces | Apply risk models in operational choices |

| Problem Diagnosis & Resolution | A-II/1, A-III/1 | Manual inspection & fault fixing | Cybersecurity resilience; digital diagnostics; predictive analytics maintenance scheduling | Identify & fix technical/operational faults | |

| Crisis Management | A-V/2 (Crisis Mgmt) | Team coordination in emergencies | Human–machine coordination under automation; remote crisis management; AI-driven decision support | Act under emergencies with automation factors | |

| Ethical & Legal Judgment | A-II/1, A-V/2 | Risk identification, drills | Data-driven risk modelling; simulation-based training for MASS and smart port interfaces | Apply IMO/flag law in automation contexts | |

| Communication & Collaboration | Cross-Disciplinary Communication | A-II/1 | Effective communication and task allocation | Cross-disciplinary comms between crew, automation, and shore; multicultural digital teamwork | Coordinate with tech, operations, and shore teams |

| Multicultural Communication | A-II/1, B-VIII/2 | Multicultural communication | Integrated comms platforms; human–AI dialogue systems; real-time multi-language translation tools | Overcome cultural & language barriers | |

| Human–Machine Coordination | A-II/1 | Team coordination in emergencies | Human–machine coordination under automation; remote crisis management; AI-driven decision support | Manage control handovers between humans & systems | |

| Teamwork & Leadership | A-V/2, A-II/1 | Leading crew operations | Change management for tech adoption; strategic thinking for autonomous operations integration | Lead mixed human-autonomy crews | |

| Leadership & Change | Strategic Thinking | A-V/2 | Leading crew operations | Change management for tech adoption; strategic thinking for autonomous operations integration | Align tech adoption with operational goals |

| Change Management | A-V/2 | Leading crew operations | Change management for tech adoption; strategic thinking for autonomous operations integration | Guide teams through digital transitions | |

| Continuous Learning Culture | B-VIII/2 (Guidance) | Multicultural communication | Encourage upskilling for evolving tech | Encourage upskilling for evolving tech | |

| Safety, Sustainability & Green | Environmental Awareness | A-II/1, A-V/2 | Waste & emission control | Energy efficiency management (SEEMP); decarbonization strategies; IoT-based environmental monitoring | Apply MARPOL, SEEMP, BWM standards |

| Alternative Fuel Handling | A-III/1, A-V/3 | LNG safety procedures | Multi-fuel safety (LNG, ammonia, hydrogen); automation-based fuel monitoring | Safe handling of LNG, ammonia, hydrogen, etc. | |

| Energy Efficiency Operations | A-II/1, A-III/1 | Energy efficiency management (SEEMP) | Energy efficiency management (SEEMP); decarbonization strategies; IoT-based environmental monitoring | Operate for low emissions & fuel efficiency | |

| Resilience & Safety Culture | A-V/2 | Schedule compliance, rest hours | Promote proactive, just safety culture | Promote proactive, just safety culture | |

| Psychological & Human-Centric | Resilience & Stress Management | A-V/2 | Schedule compliance, rest hours | Maintain performance under high cognitive load | Maintain performance under high cognitive load |

| Emotional Intelligence | A-V/2 | Multicultural communication | Manage relationships in diverse crews | Manage relationships in diverse crews | |

| Ergonomics Awareness | B-VIII/2 | Schedule compliance, rest hours | Use systems to reduce fatigue & errors | Use systems to reduce fatigue & errors |

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Trust Calibration | Measures operator confidence in AI decisions and their ability to override them. |

| Explainability Readiness | Assesses whether AI system outputs are transparent and interpretable by humans. |

| Cognitive Load Compatibility | Evaluates the mental effort required to operate or supervise digital systems. |

| Multi-Agent Coordination | Assesses crew’s readiness to coordinate with other humans, AI agents, and systems. |

| Ethical Oversight Capability | Measures user awareness and action in ethically ambiguous automation scenarios. |

| KPI Category | Indicator | Criteria or Measurement | Benchmark | Scoring Scale | Phase | Criticality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological Reliability |

AI core functionality accuracy |

% of successful task executions in controlled environments | ≥ 95% accuracy in pilot tests | 1 = <80%; 2 = 80–89%; 3 = 90–94%; 4 = 95–97%; 5 = ≥98% |

Phase 1 | High |

| Model Drift | Change in model performance over time (precision/recall degradation %) | < 2% drift per quarter | 1 = >10%; 2 = 6–10%; 3 = 3–5%; 4 = 1–2%; 5 = <1% |

Phase 5 (Continuous) |

High | |

| Multi-Agent coordination |

Latency and accuracy of AI-to-AI and AI-to-human communication | Latency < 1 sec; ≥ 90% correct coordination |

1 = <70%; 2 = 70–79%; 3 = 80–89%; 4 = 90–94%; 5 = ≥95% |

Phase 2 & 5 | High | |

| Human Readiness |

Crew familiarity with AI interfaces | % of crew demonstrating baseline proficiency in simulator assessments | ≥ 85% crew proficiency | 1 = <60%; 2 = 60–74%; 3 = 75–84%; 4 = 85–94%; 5 = ≥95% |

Phase 1 | High |

| Cognitive load reduction | NASA-TLX or equivalent workload index | ≥ 20% reduction from baseline | 1 = <5%; 2 = 5–9%; 3 = 10–14%; 4 = 15–19%; 5 = ≥20% |

Phase 5 (Continuous) |

Medium | |

| Situational awareness | Performance in scenario-based assessments (e.g., recognition of anomalies) | ≥ 90% correct anomaly identification | 1 = <70%; 2 = 70–79%; 3 = 80–89%; 4 = 90–94%;5 = ≥95% |

Phase 3 | High | |

| Workflow Integration |

Decision-making Hierarchy adherence |

% of operations following defined human-AI decision protocols | ≥ 95% adherence | 1 = <70%; 2 = 70–79%; 3 = 80–89%; 4 = 90–94%; 5 = ≥95% |

Phase 2 | High |

| Override protocol effectiveness | Response time and accuracy during emergency override drills | < 10 sec response; ≥ 95% correct overrides |

1 = >30 sec/<70%;2 = 20–30 sec/70–79%; 3 = 15–19 sec/80–89%; 4 = 10–14 sec/90–94%; 5 = <10 sec/≥95% | Phase 2 | High | |

| Competency Development |

Training progression rate | % of crew achieving advanced AI oversight certification within timeframe | ≥ 80% certified within 12 months | 1 = <50%; 2 = 50–64%; 3 = 65–79%; 4 = 80–89%; 5 = ≥90% |

Phase 3 | High |

| Ethical decision-making | Score on validated ethical decision-making tests in AI-supported scenarios | ≥ 90% compliance with ethical guidelines |

1 = <60%; 2 = 60–74%; 3 = 75–84%; 4 = 85–89%; 5 = ≥90% |

Phase 3 | Medium | |

| Regulatory Compliance |

Certification attainment | % of AI components meeting classification society standards | 100% certification | 1 = <70%; 2 = 70–84%; 3 = 85–94%; 4 = 95–99%; 5 = 100% |

Phase 4 (Parallel) |

High |

| Audit trail completeness | % of AI decision logs traceable and verifiable | ≥ 95% completeness | 1 = <70%; 2 = 70–79%; 3 = 80–89%; 4 = 90–94%; 5 = ≥95% |

Phase 4 & 5 | High | |

| Operational Refinement |

Near-miss reporting rate | % of near-miss events reported and analyzed | ≥ 90% reporting rate | 1 = <50%; 2 = 50–69%; 3 = 70–79%; 4 = 80–89%; 5 = ≥90% |

Phase 5 (Continuous) |

Medium |

| Decision accuracy | % of correct human-AI decisions in real-world operations | ≥ 98% decision accuracy | 1 = <80%; 2 = 80–89%; 3 = 90–94%; 4 = 95–97%; 5 = ≥98% |

Phase 5 (Continuous) |

High | |

| Efficiency gains | % improvement in fuel use, routing, or other operational KPIs | ≥ 10% improvement from baseline | 1 = <3%; 2 = 3–5%; 3 = 6–7%; 4 = 8–9%; 5 = ≥10% |

Phase 5 (Continuous) |

Medium |

| KPI Category | Indicator | Criteria / Measurement | Benchmark | Scoring Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical & Digital | Automation Systems Operation | Evaluate the ability to configure, monitor, and operate autonomous navigation and propulsion systems, including initiating safe overrides during system faults. | ≥98% correct operations, ≤1% error rate | 1=<80%, 2=80–89%, 3=90–94%, 4=95–97%, 5=≥98% |

| HMI Proficiency | Measure operator’s response time and accuracy when interpreting system alerts, adjusting parameters, and acknowledging alarms on bridge consoles. | ≤5s response, ≥95% accuracy | 1=>10s/<80%, 2=8–10s/80–89%, 3=6–7s/90–94%, 4=5s/95–97%, 5=≤4s/≥98% | |

| AI & Data Analytics | Assess ability to interpret AI-generated predictive maintenance reports, identify anomalies, and recommend corrective actions with supporting data. | ≥95% correct diagnostics | Same 1–5 scale as above | |

| IoT & Sensor Integration | Evaluate skill in validating sensor readings, cross-checking data sources, and ensuring real-time integration with ship control systems. | ≥97% accuracy | Same scale | |

| Cybersecurity Awareness | Measure speed and accuracy in detecting, reporting, and responding to simulated cyber threats, phishing attempts, or malware alerts. | 100% detection in simulation | 1=<70%, 2=70–79%, 3=80–89%, 4=90–94%, 5=≥95% | |

| Digital Navigation Tools | Assess competence in operating ECDIS, GNSS, ARPA, and radar safely under various voyage conditions, including in degraded mode scenarios. | 100% compliance with SOP | Same scale | |

| Remote Operations Control | Measure ability to remotely control propulsion and steering functions with minimal latency, ensuring operational continuity during automation transitions. | ≤2s latency, ≥98% success | Same scale | |

| Cognitive & Situational Awareness | Situational Awareness | Assess capability to detect, interpret, and predict changes in environmental and vessel conditions while multitasking under pressure. | ≥95% detection in drills | Same scale |

| Information Processing | Evaluate ability to filter, prioritize, and integrate high volumes of data from multiple systems into actionable decisions within strict time limits. | ≥95% correct outputs in 1 min | Same scale | |

| Workload Management | Measure effectiveness in prioritizing operational tasks, allocating crew resources, and meeting voyage deadlines without overloading personnel. | ≥95% tasks on time | Same scale | |

| Adaptability | Assess speed and accuracy in shifting from manual to autonomous operations and vice versa while maintaining safety standards. | ≤30 sec transition | 1=>90s, 2=60–89s, 3=45–59s, 4=31–44s, 5=≤30s | |

| Decision-Making & Problem-Solving | Risk-Based Decision-Making | Evaluate ability to identify hazards, assess risk levels, and select optimal mitigation strategies under realistic operational scenarios. | ≤2 min, ≥95% accuracy | Same scale |

| Problem Diagnosis & Resolution | Measure diagnostic accuracy and time taken to isolate faults in shipboard systems and implement corrective measures. | ≤10 min | 1=>30 min, 2=21–30 min, 3=15–20 min, 4=11–14 min, 5=≤10 min | |

| Crisis Management | Assess ability to execute crisis protocols, coordinate emergency teams, and maintain situational control during high-pressure simulations. | 100% adherence | Same scale | |

| Ethical & Legal Judgment | Evaluate awareness and application of IMO, SOLAS, and flag state legal frameworks in operational decision-making. | 100% compliance | Same scale | |

| Communication & Collaboration | Cross-Disciplinary Communication | Assess clarity, conciseness, and timeliness in communicating with engineering, navigation, shore control, and automation teams. | 0 incidents/month | 1=≥4 incidents, 2=3, 3=2, 4=1, 5=0 |

| Multicultural Communication | Measure ability to adapt communication style to diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds while ensuring operational clarity. | 0 incidents/month | Same scale | |

| Human–Machine Coordination | Evaluate effectiveness in handovers between human and automated control systems, ensuring no operational gaps or conflicts. | ≤3s delay, no error | Same scale | |

| Teamwork & Leadership | Measure ability to foster collaboration, resolve conflicts, and align team performance with voyage objectives. | ≥95% target met | Same scale | |

| Leadership & Change | Strategic Thinking | Evaluate ability to formulate, articulate, and defend long-term strategies for technology adoption and operational improvement. | ≥95% KPI success in trials | Same scale |

| Change Management | Assess ability to gain stakeholder buy-in, train personnel, and maintain productivity during technology or process transitions. | ≥90% adoption in 3 months | Same scale | |

| Continuous Learning Culture | Measure the extent to which individuals promote training participation, knowledge sharing, and skill renewal among the crew. | ≥95% completion | Same scale | |

| Safety, Sustainability & Green | Environmental Awareness | Evaluate ability to identify, monitor, and reduce environmental risks in line with SEEMP, BWM, and MARPOL guidelines. | 100% audit compliance | Same scale |

| Alternative Fuel Handling | Assess skill in safe storage, transfer, and use of alternative fuels such as LNG, ammonia, and hydrogen. | 100% safe execution | Same scale | |

| Energy Efficiency Operations | Measure ability to apply operational adjustments to optimize fuel usage and reduce emissions without compromising safety. | ≥10% improvement | 1=<4%, 2=4–6%, 3=7–8%, 4=9%, 5=≥10% | |

| Psychological & Human-Centric | Resilience & Stress Management | Evaluate consistency of decision-making, concentration, and accuracy under sustained mental or physical stress conditions. | ≥95% normal performance | Same scale |

| Emotional Intelligence | Measure ability to perceive, interpret, and respond constructively to the emotions of team members in high-pressure situations. | ≥4.5/5 score | 1=<3, 2=3–3.4, 3=3.5–3.9, 4=4–4.4, 5=≥4.5 | |

| Ergonomics Awareness | Assess compliance with ergonomic best practices to reduce fatigue and prevent injury during routine and emergency tasks. | ≥95% compliance | Same scale |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).