1. Introduction

Sports-related concussion (SRC) and repetitive head impacts (RHI) are continuing to be a concern across many sports worldwide, particularly combat and contact sports. Risks of long-term outcomes such as cognitive impairments and neurodegenerative disease have been described in the mainstream media as an “existential threat” to sports [

1,

2].

In limited or no-contact sport, however, the rates of SRC are lower. Still, the risk of injury is still apparent and has prompted many organisations to adopt or update their concussion policies and procedures for all levels of sport participation [

3,

4]. Cycling fits into this category, with Swart et al [

5] suggesting that SRC accounts for between 1.3% and 9.1% of all cycling-specific injuries (lower than the football codes). However exact numbers are difficult to determine as, like many other sports, SRC is underreported, or not reported by cyclists [

6]. Reasons for this are varied, and include lack of knowledge/awareness [

6,

7], sex [

8,

9], a cultural belief that concussion are “not serious” [

6] with team-mate peer pressures to downplay concussion by encouraging hiding of, or ignoring any concussion type symptoms [

10].

On a more positive note, cycling is addressing the issues of SRC with the publication of cycling-specific concussion assessment. For example, the Harrogate consensus agreement [

5], roadside concussion assessment for cycling [

11], and the emergence of concussion and brain trauma research across cycling sub-disciplines [

12,

13].

Research to date has focused mostly on the incidence of SRC. However, little is known on the longitudinal aspects of repetitive concussion in cycling. While anecdotal accounts of long-term cognitive impairments [

14] and concerns regarding neurodegenerative disease [

15] have been reported in competitive track cycling and BMX respectively, to date there has been no systematic study of longitudinal outcomes following concussion in cyclists.

Previous studies investigating longitudinal effects of repeated concussions across contact and combat sports have examined pathophysiology of the corticospinal pathways [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Indeed, it has been argued that changes in the motor pathways are typically a sign of clinical manifestation of repetitive chronic brain injuries in athletes [

21].

A non-invasive technique that can sensitively measure cortical inhibitory and excitatory mechanisms of the corticospinal pathway is single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Used in clinical and experimental neurology [

22,

23,

24], TMS employs a high-current pulse produced through a coil of wire to create a brief magnetic field that, at an appropriate intensity, depolarises underlying neural tissue generating a motor evoked potential (MEP) which can be measured using surface electromyography (sEMG). The MEP waveform following single pulse TMS reflects the integrity of the corticospinal tract, with the amplitude of the waveform providing an index of the strength of the descending volleys at the time of stimulation [

25]. Following the MEP, a transient suppression of activity, known as the cortical silent period (cSP) is also observed. The cSP duration length reflects intracortical inhibitory processes mediated by γ-aminobutryic acid type B (GABA

B) receptors [

26]. Paired pulse TMS is also widely utilised to investigate intracortical inhibitory pathways within the primary motor cortex. When a subthreshold conditioning stimulus precedes a suprathreshold test stimulus between 1-5 ms, the MEP amplitude is reduced, reflecting short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI), mediated by γ-aminobutryic acid type A (GABA

A) receptor activity [

22]. Conversely, long-interval intracortical inhibition (LICI) results when two suprathreshold stimuli are presented at an interstimulus interval between 50 and 200 ms. The suppression of the test stimulus reflects γ-aminobutryic acid type B (GABA

B) receptor activity. However while cSP and LICI reflect GABA

B receptor activity, cSP and LICI reflect different neural populations and circuit dynamics [

27].

Complimenting TMS, sensorimotor testing aims to non-invasively assess central nervous system function through tactile sensory perception. Through delivering precise vibrotactile stimuli to the fingertips (specifically digits D2 and D3) testing can evaluate cortical processing mechanisms based upon stimuli frequency, duration, timing and amplitude [

28]. Previous studies using sensorimotor assessment has supported TMS findings in slowed reaction time and slowed responses rates across various cognitive-motor testing in athletes with a history of concussions compared to age-matched controls [

17].

Rabadi and Jordan’s hypothesis have subsequently been confirmed in studies using TMS in contact and combat athletes [

16,

19,

29,

30,

31]. However, TMS studies investigating concussion have not yet been undertaken in cyclists. With increased concerns on not only high rates of traumatic injury, but also risks of repetitive non-concussive brain trauma particularly in off-road [

12,

13] and alternative cycling events (e.g. freestyle BMX), studies into longitudinal outcomes following concussion is required.

The present study evaluated in a cycling mixed cohort, with and without persistent symptoms, sensorimotor performance and neurophysiological excitability and inhibition. It was hypothesised that cyclists with persistent symptoms would report a history of greater number of repeated concussions, poorer sensorimotor test performance, and greater motor system inhibition.

2. Materials and Methods

This study utilised a between-groups design, with participants visiting the laboratory for a single visit. Twenty-five cyclists (21 males, 4 females) with a history of concussions, and 20 age-matched controls (17 males, 3 females) participated in testing. Controls had no history of concussions or participation in contact sports, an absence of self-reported cognitive or behavioural concerns, nor diagnosed neurological impairments or psychiatric disorders.

Table 1 outlines all participants’ demographics and concussion history. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols (HEC18005, see full statement at end of this manuscript) conforming to the guidelines set out by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cyclists were recruited via word of mouth throughout various cycling communities. Participants were from a range of disciplines including road (n=7), mountain biking (MTB, n=11) and bicycle motocross (BMX, n=7). BMX riders included both racing and freestyle BMX. Based on self-assessment symptom reporting (

Table 2), the cycling group was divided into those who expressed concerns regarding their cognitive health because of their history of repetitive concussions (symptomatic’: n=15), and those who acknowledged they had a history of concussion from cycling but did not express any ongoing concerns (‘asymptomatic’: n=10). Other than concussion history, cycling participants had no neurological or psychiatric diagnoses.

Prior to testing, participants completed pre-screening for suitability to TMS, the fatigue and related symptom survey [

32], sensorimotor processing via vibrotactile stimulation [

28], and TMS. Vibrotactile stimulation and TMS were conducted in a counterbalanced order to reduce potential stimulation serial effects [

18].

2.1. Symptom Assessment

Symptoms were recorded on the Post Concussion Symptom Scale (PCSS) from the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool Version 5 (SCAT5) as number of self-reported symptoms (maximum 22 symptoms) and severity of each identified symptom (maximum 132 points) [

33].

2.2. Cognitive and Motor Testing

Cognitive and motor testing were completed using elements of the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool V5 [

33]. Immediate memory was assessed using the 10-word recall involving three repeat trials and was scored as the total correct responses from three trials of 10 words (maximum score 30). Delayed memory was conducted approximately 15 minutes after the immediate testing when the participant had undertaken concentration and motor testing tasks. Participants were asked to recall how many of the words they were given.

Concentration was measured using the digit backwards assessment and reverse months of the year. Participants were given a set of numbers, from three digits to a maximum of six digits, and instructed to respond the opposite order presented to them. For this study scoring for concentration involved both trials for each level of difficulty, thereby scores were out of a maximum of eight, rather than four. Participants were then asked to recall the months of the year in reverse order. Maximum score for concentration was nine (eight for digit backwards plus one for reverse months).

Motor testing involved the tandem gait, where participants were instructed to walk on a 10m marked straight line with one foot in front of the other, with heel and toe touching of each foot, as quickly as possible without making any errors. Two attempts were provided with the fastest time without error recorded.

Balance was measured with single leg and tandem leg stance (Romberg test). Following familiarisation with eyes open, both tests were completed with eyes closed and assessed by the number of errors (i.e. using other leg to stop falling over) in each 30s trial.

2.3. Sensorimotor Testing

Employing previously published protocols in concussion participants [

18,

30], sensorimotor assessment was completed via a portable vibrotactile stimulation device (Cortical Metrics, USA). The device, similar appearance to a standard computer mouse, contains two cylindrical probes (5 mm diameter) positioned at the top and towards the front of the device. These probes, driven by the computer via a USB cable, provided a light vibration stimulus, at frequencies between 25–50 Hz sensed by the participant’s index (D2) and middle (D3) digits of their non-dominant hand [

10].

The testing battery consisted of five distinct tasks: 1) simple reaction time, completed at the beginning and end of the battery to ascertain any fatigue from the challenge of the tasks; 2) choice reaction time by choosing which digit, D2 or D3, felt the stimulus pulse; 3) amplitude discrimination from deciding which digit, D2 or D3, felt a greater intensity during trial of separate sequential vibration of the digits, followed by trial of simultaneous vibration of the digits; 4) temporal order judgment by determining of the two stimulus pulses which digit, D2 or D3, felt the first stimulus pulse; and 5) duration discrimination where participants needed to decide which vibration stimuli presented simultaneously lasted for a longer time. For full detailed protocols the reader is referred to Holden et al [

34] and Tommerdahl et al [

28].

2.4. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and Surface Electromyography

Using well established methods [

26,

35,

36], single- and paired-pulse TMS were applied over the area of the contralateral primary motor cortex (M1) targeting the participant’s first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscle. For electromyography (EMG) surface electrodes (ADInstruments, Australia) with an inter-electrode distance of 2cm were placed over the FDI of the participant’s dominant hand following the recommendations of the surface electromyography for non-invasive assessment of muscles (SENIAM) project [

37]. Signals were amplified (×1,000), filtered (10–1,000 Hz), and sampled at 2 kHz, recording 500 ms responses (100 ms pre-stimulus, 400 ms post-stimulus; PowerLab 4/35, ADInstruments, Australia). All TMS procedures were undertaken with the TMS checklist for methodological quality [

38].

A MagVenture R30 stimulator (MagVenture, Denmark) with a C-B60 butterfly coil (outer dimension 75 mm) was used to generate MEPs. During TMS testing, participants wore a fitted cap (EasyCap, Germany), marked with sites at 1-cm spacing in a latitude-longitude configuration to ensure correct coil location. The cap was positioned with reference to the nasion-inion and interaural surface anatomical landmarks [

39]. Prior to data collection participant’s ‘optimal site’ was identified, where the largest MEP was observed. The optimal site was then used throughout the TMS protocols.

2.4.1. Single Pulse TMS

Motor threshold (MT) is the identified as the lowest stimulation to observe a MEP of at least 50µV with the muscle at rest, or 200µV during muscle contraction [

40]. Active motor threshold (aMT) was identified during a controlled, low-level voluntary contraction (10 ±3% maximal voluntary contraction, MVC, taken prior to TMS) of the FDI muscle. Stimulator output was increased in 5% steps, starting from 15% of the stimulator output, then 1% of stimulator output to determine exact aMT, while the participant held the isometric contraction until discernible MEPs were observed [

41,

42].

Once aMT was identified, 20 stimuli (four sets of five stimuli) were delivered at 130%, 150% and 170% of aMT. To avoid stimulus anticipation, stimuli were spaced 4-8 s apart with 30-s rest between each set to reduce muscle fatigue.

Corticospinal latency was measured from the TMS stimulus artefact on the EMG to the onset of the MEP waveform. MEP waveform amplitude was calculated from measuring the peak-to-trough difference on the EMG. Duration of the cSP was measured from the initial onset of the MEP waveform to the return of uninterrupted EMG [

26]

To address between-participant variability of the MEP [

22], ratios were calculated by the duration of the cSP with the amplitude of the MEP [

43,

44]. The cSP:MEP ratio reflects the balance between inhibitory and excitatory mechanisms observed in the MEP waveform. SRC cohorts using cSP:MEP ratios have been previously published [

30,

45,

46].

2.4.2. Paired-Pulse TMS

Paired-pulse MEPs for SICI was measured with the FDI at a slight contraction of 5% MVC with a conditioning stimulus of 80% aMT and a test stimulus of 130% at an interstimulus interval of 3 ms [

16,

18,

35,

47]. Fifteen stimuli (in three sets of five) were delivered at random intervals between 8–10 s, with a 30 s interval after each set of five. SICI was expressed as a ratio of the paired-pulse MEP amplitude to the MEP amplitude measured at 130% AMT [

16,

18,

35,

48]. LICI was measured at an interstimulus interval of 100 ms with suprathreshold conditioning and test stimuli at 130% of aMT [

16,

18,

47], and also expressed as a ratio of the conditioning stimulus and test stimulus [

16,

18,

29,

47].

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Data was screened for normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests and found to be normally distributed (

W=0.949 – 0.981;

p>0.05). A one-way ANOVA was utilised to test differences between groups for cognitive and motor testing elements of the SCAT5, sensorimotor, and TMS. Where ANOVA detected significance, post-hoc comparisons using Tukey adjustments were employed. Exceptions to this were analysis of number of concussions, time since last concussion, and symptom reporting which were compared between the cycling participants using unpaired t-test. Where appropriate, Cohen’s

d effect sizes were employed with 0.2 (small), 0.5 (moderate), and 0.8 (large) used to describe the magnitude of effects [

49]. Alpha was set at 0.05. Data are presented as mean (±SD).

3. Results

All participants completed testing with no adverse effects. No differences were observed in age or the time since the last concussion experienced (

Table 1). However, cyclists with ongoing symptoms reported a greater number of concussions (

p= 0.041,

d= 0.962;

Table 1). Cyclists expressing ongoing concerns scored significantly higher on the fatigue and related symptom scale (

p<0.001), number of symptoms (

p<0.001), and severity of symptoms (

p<0.001;

Table 2).

3.1. Cognitive and Motor Assessment

One-way ANOVA for cognitive testing showed no differences in immediate (F

(2,42)=2.684,

p=0.081), or delayed memory recall (F

(2,42)=2.803,

p=0.073;

Table 3). However, concentration revealed a significant difference (F

(2,42)=6.151,

p=0.005) with post-hoc testing showing symptomatic cyclists performing worse in concentration (digit backwards) than control participants (

p=0.005;

d=1.087).

Motor tests (

Table 4) revealed significant differences between groups for tandem gait walk time (F

(2,42)=14.65,

p<0.001) and for number of errors tandem leg stand (F

(2,42)=4.33,

p=0.020). Post-hoc testing for tandem gait walk time showed symptomatic riders were slower than both asymptomatic (

p<0.001,

d=2.258) and control groups (

p<0.001,

d=1.610). Tandem leg stance showed symptomatic cyclists had greater errors than both asymptomatic (

p=0.043,

d=0.862) and control groups (

p=0.041,

d=1.012). Conversely, no differences were found between groups for number of errors with single leg balance (F

(2,42)=1.296,

p=0.288).

3.2. Sensorimotor Testing

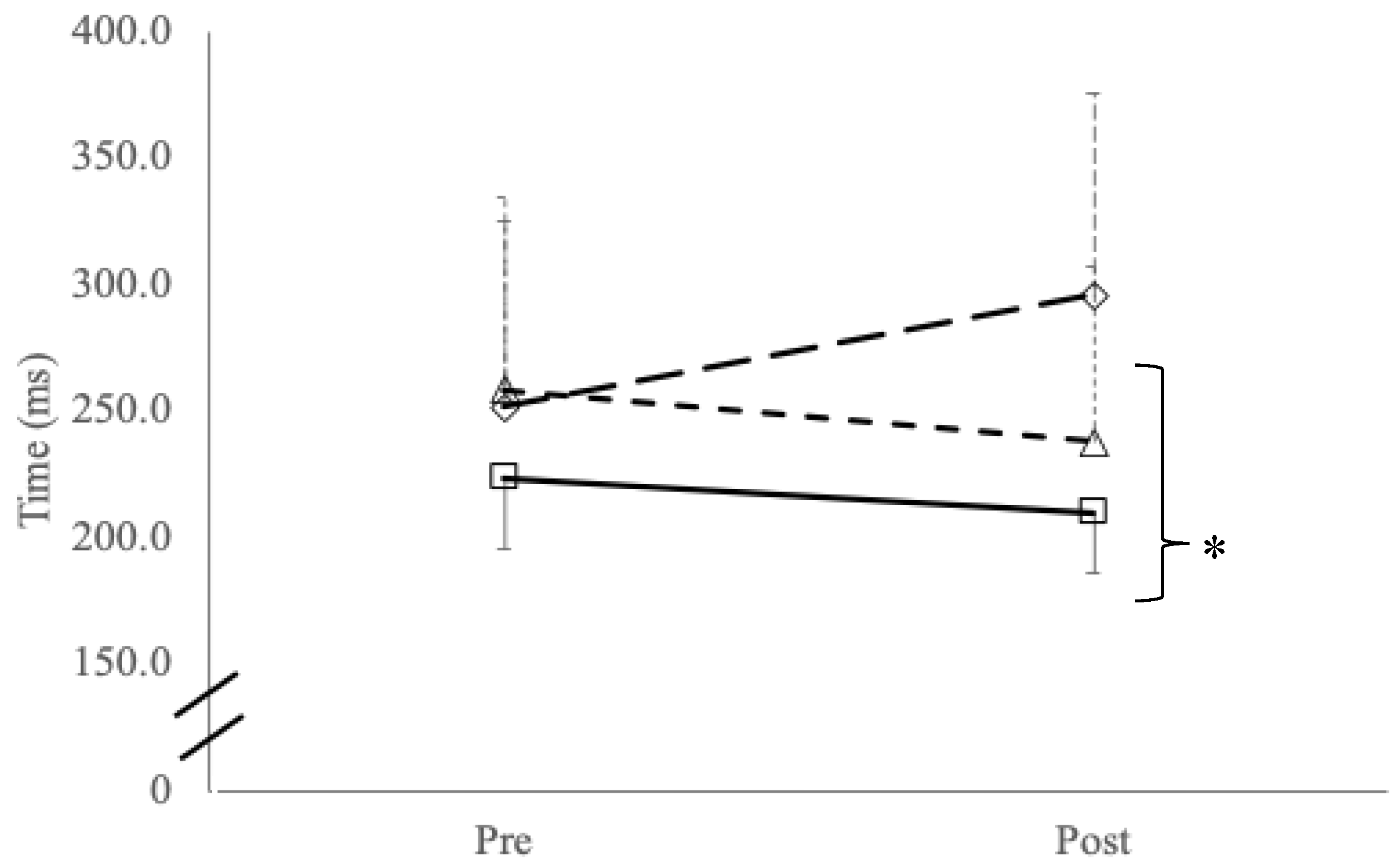

Repeated simple reaction time testing reported a significant group x time interaction effect (F

(2,42)=20.1,

p<0.001) and main effects for group (F

(2,42)=20.1,

p=0.005) with post-hoc testing showing significant slowing in reaction time between symptomatic cyclists compared to control participants (

p=0.001;

Figure 1). No interaction effects were found with reaction time variability (

p=0.359) or main effects for time (

p=0.465) or between groups (

p=0.465).

Table 5.

Sensorimotor testing data between groups. Data reported in mean (± SD).

Table 5.

Sensorimotor testing data between groups. Data reported in mean (± SD).

| |

Choice RT+

(ms) |

Choice RT error

(% correct) |

Sequential amplitude

discrimination (μm) |

Simultaneous amplitude

discrimination (μm) |

Temporal order

judgement (ms) |

Duration

Discrimination

(ms) |

| Symptomatic (n=15; 12m, 3f) |

467.0 (±118.8) |

94.0 (±5.5) |

49.2 (±37.3) |

80.5 (±46.4) |

42.11 (±25.2) |

65.3 (±38.5) |

| Asymptomatic (n=10; 9m, 1f) |

448.3 (±84.7) |

90.0 (±5.8) |

37.4 (±29.2) |

54.5 (±23.3) |

25.9 (±15.4) |

64.2 (±46.3) |

| Controls (n=20; 17m; 3f) |

423.3 (±82.1) |

93.0 (±4.8) |

43.5 (±33.5) |

55.0 (±34.5) |

25.8 (±11.3) |

53.5 (±20.1) |

3.2. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Table 6 shows data from TMS. No differences were observed between groups for aMT (F

(2,42)=0.25,

p=0.776) or corticospinal latency (F

(2,42)=1.90,

p=0.182). While no differences between groups was found in cSP:MEP ratio at 130%aMT (F

(2,42)=1.29,

p=0.285), significant differences were found at 150%aMT (F

(2,42)=4.29,

p=0.020) and 170%aMT (F

(2,42)=3.62,

p=0.035). Post hoc testing at 150%aMT showed differences between symptomatic and control groups (

p=0.018;

d=1.265). Similarly, differences at 170%aMT were found between symptomatic and controls (

p=0.046;

d=1.040).

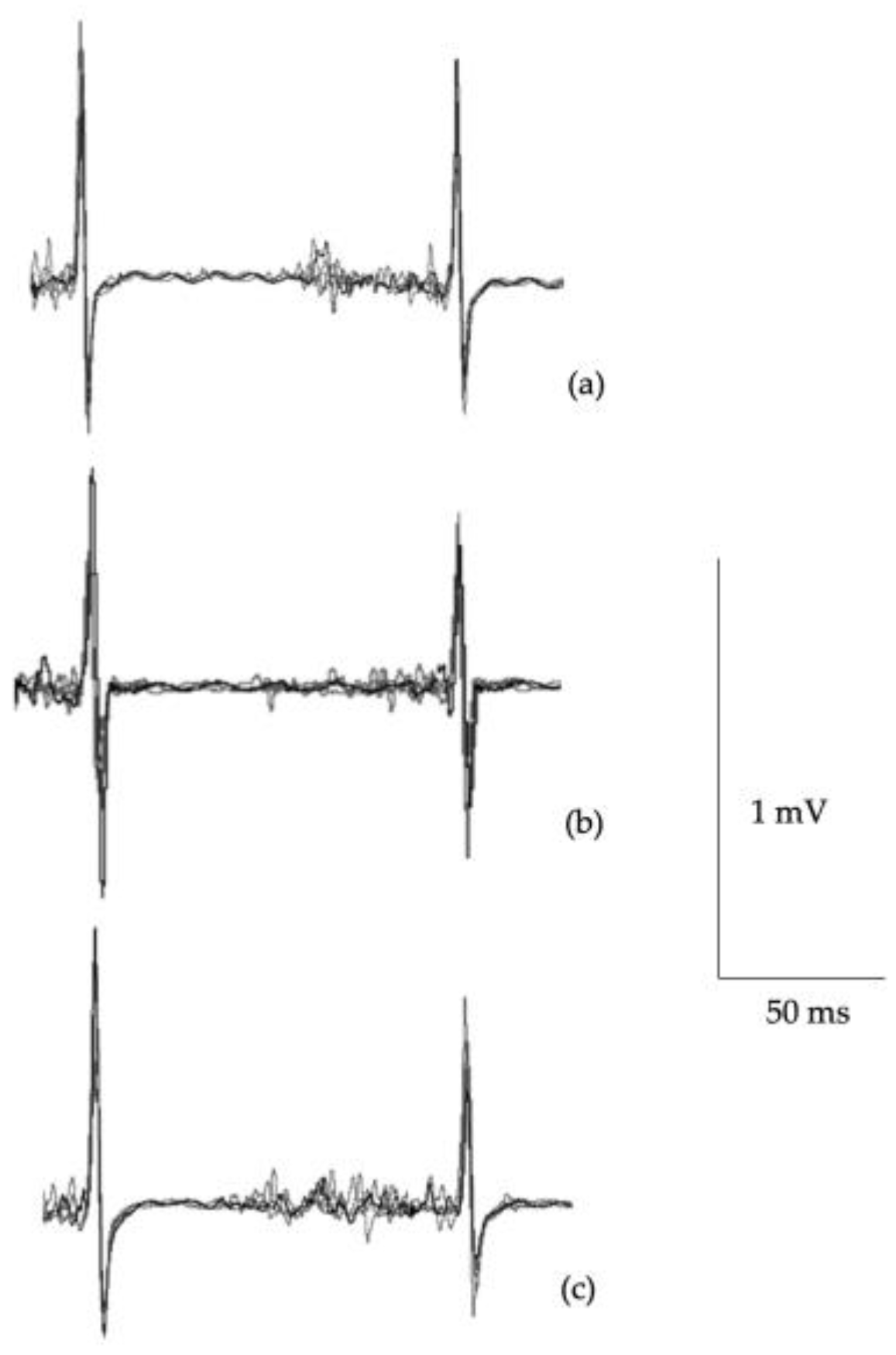

Figure 2 illustrates single pulse MEP waveforms illustrating differences in cortical inhibition.

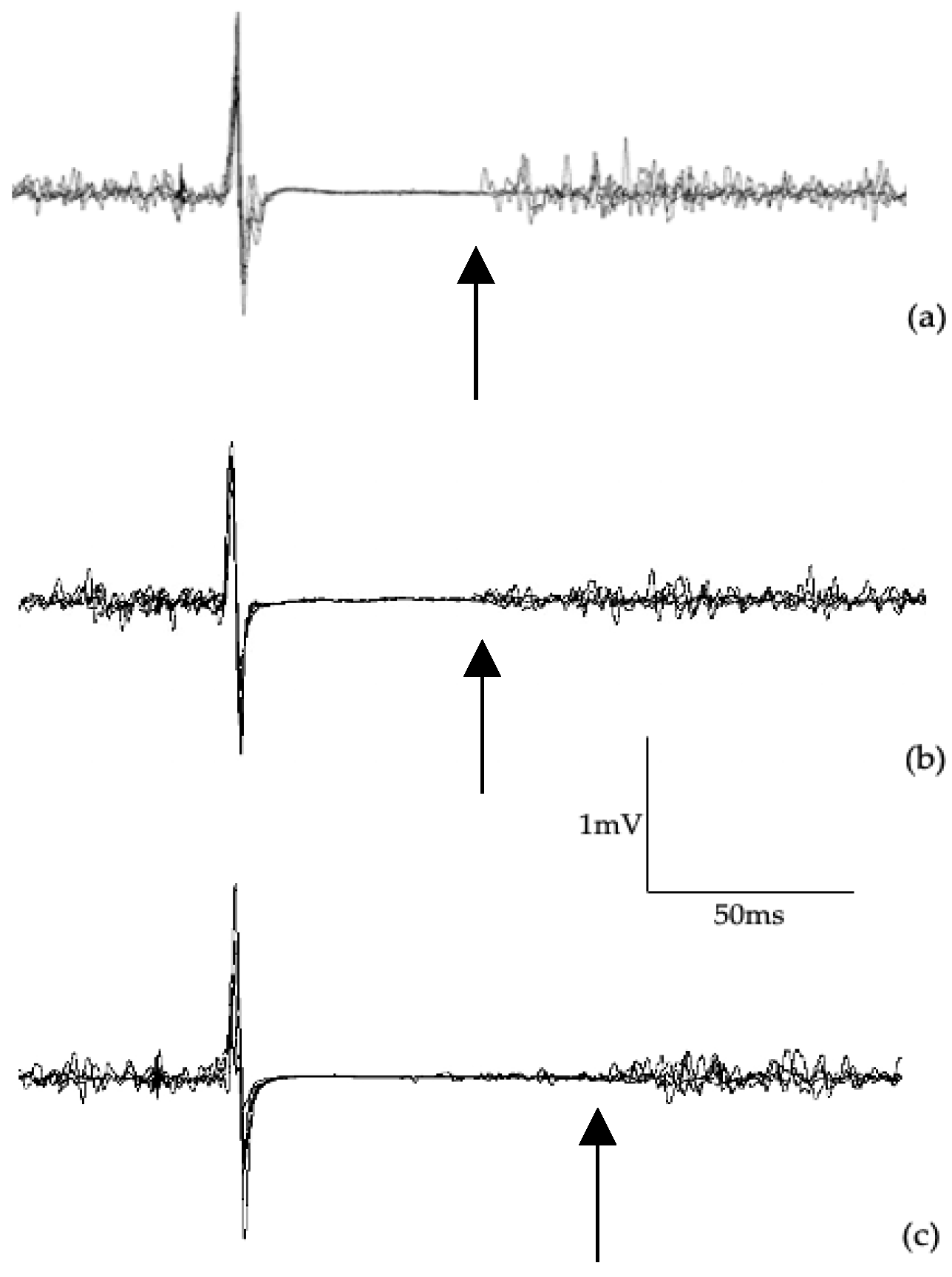

SICI ratio (

Table 6,

Figure 3) showed significant differences between groups (F

2,42=9.39,

p=0.001) with post hoc testing revealing significant differences between symptomatic versus asymptomatic (

p=0.001;

d=1.319) and control groups (

p=0.013;

d=2.742). Although large effects were observed between the symptomatic and asymptomatic groups (

d=0.89), and controls (

d=0.85), no significant differences were found with LICI ratio (F

2,42=2.41,

p=0.112).

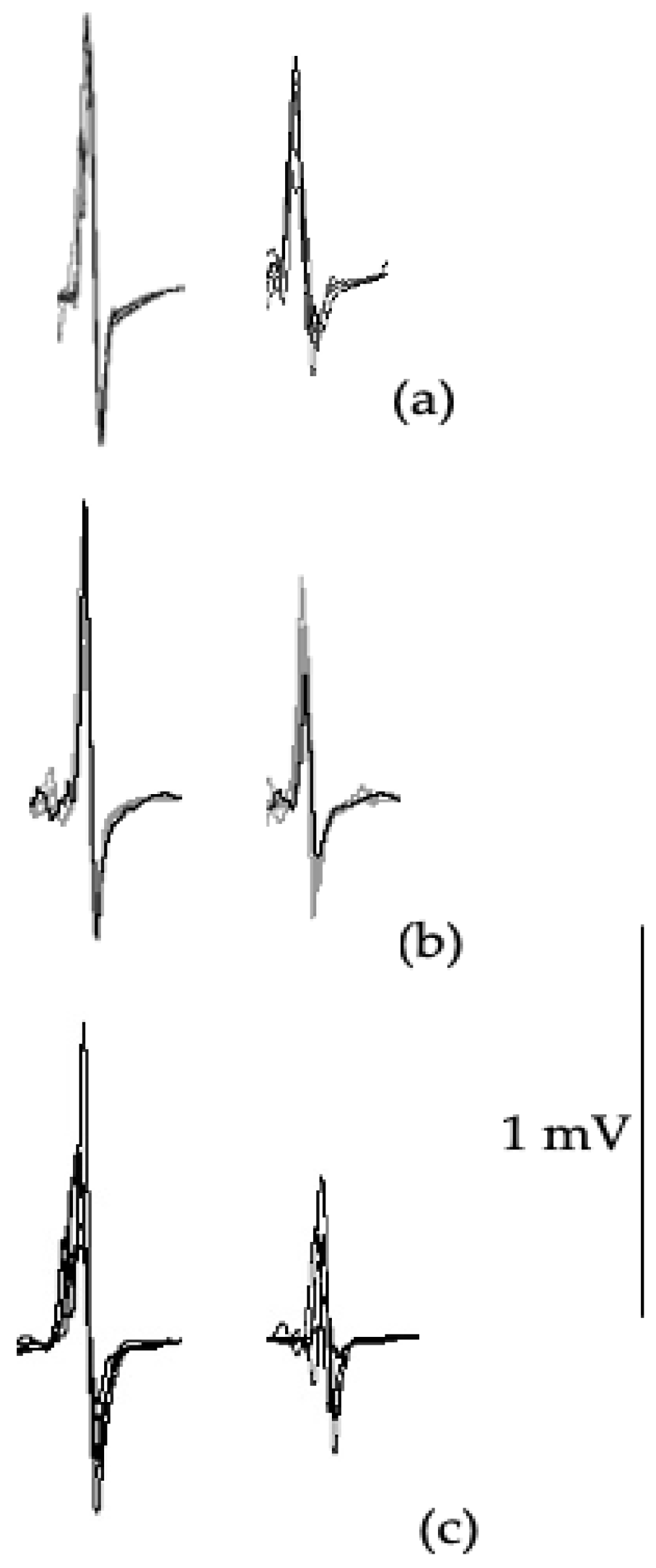

Figure 4.

Example of LICI waveforms at 100 ms interstimulus interval paired pulse from a control participant (a), an asymptomatic cyclist (b), and a symptomatic cyclist (c). LICI test waveform amplitude (second waveform) is compared to the control waveform amplitude (first waveform) and expressed as a ratio.

Figure 4.

Example of LICI waveforms at 100 ms interstimulus interval paired pulse from a control participant (a), an asymptomatic cyclist (b), and a symptomatic cyclist (c). LICI test waveform amplitude (second waveform) is compared to the control waveform amplitude (first waveform) and expressed as a ratio.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to quantify the excitability of the corticomotor pathways to understand cyclists with self-reported persistent issues compared to those who had reported no ongoing issues and age-matched controls. Results from this study suggest that multiple SRCs results in chronic motor control dysfunction with TMS data support from intracortical inhibitory system abnormalities. Specifically, cyclists with persistent symptoms showed: 1) greater number of concussions and higher self-reported F&RSS scores; 2) poorer concentration, slowed reaction times and timing judgement; 3) increased errors in motor tasks including tandem gait and tandem leg stance balance; and 4) increased cortical inhibition from TMS.

While these findings have been previously reported in contact sport athletes [

19,

20,

30], to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first reported data in cyclists. It should be noted however, that while “symptomatic” cyclists showed notably poorer outcomes than “asymptomatic” cyclists and controls, overall these results, with the exception of 10-word recall, were not outside of previously published clinical reference limits in multi-sport athlete studies [

50,

51].

Conversely, sensorimotor testing showed meaningfully slowed reaction times and timing judgement impairments. While the differences in reaction time have been reported across athlete groups [

17,

45], the finding of temporal order judgement is interesting as Tommerdahl and colleagues have shown this measure reflects frontal-striatal cortex processing with reportedly poorer sequencing and coordination associated with poorer performance on this metric [

28,

52]. Further, cortical inhibition was seen as pointedly prolonged cortical silent period and decreased SICI suggesting that the cortical pathways remain affected and may explain impaired reaction times, timing performance, and tandem gait and balance performance. While LICI was not meaningfully different in the “symptomatic” group, the large effect size does support LICI differences reported in previous studies [

18,

30,

47]. Taken together, these findings suggest that a history of concussions induce ongoing alterations of intracortical inhibition mediated by GABA

A and GABA

B receptor activity [

18,

19,

20].

Taken together, these results suggest that ongoing increased cortical inhibition and cognitive-motor performance decrements that cyclists could be at risk of further injury. Indeed, the group with reported ongoing concerns (“symptomatic”) showed they have a greater history of concussion injuries. However, given the scope of the study, there was no data taken on overall injury history in the cyclists. Despite this limitation, there is strong evidence from multiple systematic reviews that show increased risk of concussions and musculoskeletal injuries in athletes with a history of multiple concussions [

53,

54,

55,

56], with research suggesting residual disturbance of cortical potentials in neuronal networks involved affecting postural movements and reducing the threshold for further brain re/injury [

31].

Limitations of this study include self-assessment reporting by the cyclists. While self-reporting does come with concerns generally [

20], the aim here was to use a validated instrument for comparative purposes rather than quantifying their current situation. Of note, cyclists are well known for down-playing their symptoms and also will not seek or even ignore medical advice to continue riding [

6]. However, future research should aim to quantify cyclist’s medical histories including non-concussive injuries that may impact on self-report. A further limitation is that many of the symptomatic group were continuing to ride and may have affected the results. As discussed, many cyclists, particularly those who take greater risks with BMX jumping and MTB, do not heed medical advice and continue where they may be experiencing sub-concussive events [

12,

13]. However, we aimed to best control the cycling participants by excluding those who had a concussion within six months prior to testing. The study is also limited in that general musculoskeletal injury history was not able to be taken and could influence tandem gait and balance scores [

57,

58]. However, similar to concussion history, as part of the screening process individuals were not eligible for participation if they had a musculoskeletal injury within the previous six months.

In conclusion, this novel study in cyclists shows that repetitive sports concussions induced persistent balance changes, along with slowed reaction times, timing judgements and increased cortical inhibition. Using non-invasive techniques such as sensorimotor testing and TMS provides insights into central nervous system information processing mechanisms that can assist the clinical assessment for cyclists across different sub-disciplines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.P; methodology, A.J.P; data analysis, A.J.P; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.P and D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, nor any support for the work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of La Trobe University (HEC18005). A.J.P is no longer affiliated with La Trobe University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from an authorised institution.

Conflicts of Interest

A.J.P. is currently a nonexecutive director of the Concussion Legacy Foundation Australia and is an Associate Editor of JFMK. He has previously received partial research funding from the Sports Health Check Charity (Australia), the Australian Football League, the Impact Technologies Inc., and the Samsung Corporation and is remunerated for expert advice to medico-legal practices. D.K. declare no competing interests.

References

- Steinberg, L. "Concussion epidemic is existential threat to football." Forbes, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/leighsteinberg/2017/11/18/concussion-epidemic-is-existential-threat-to-football/. 25 February 2025.

- Mark, D. "Rugby league's existential crisis as concussion threatens the game's physicality." ABC Australia, 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-05/rugby-leagues-existential-crisis-concussion/100192676. 25 February 2025.

- Patricios, J.S.; Schneider, K.J.; Dvorak, J.; Ahmed, O.H.; Blauwet, C.; Cantu, R.C.; A Davis, G.; Echemendia, R.J.; Makdissi, M.; McNamee, M.; et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport–Amsterdam, October 2022. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uk concussion guidelines for non-elite (grassroots) sport. 2023. London, United Kingdom.

- Swart, J.; Bigard, X.; Fladischer, T.; Palfreeman, R.; Riepenhof, H.; Jones, N.; Heron, N. Harrogate consensus agreement: Cycling-specific sport-related concussion. Sports Med. Heal. Sci. 2021, 3, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwicke, J.; Hurst, H. Concussion knowledge and attitudes amongst competitive cyclists. J. Sci. Cycl. 2020, 9, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Johnson, N.A.; Saluja, S.S.; Correa, J.A.; Delaney, J.S. Do Mountain Bikers Know When They Have Had a Concussion and, Do They Know to Stop Riding? Am. J. Ther. 2019, 31, e414–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, A.J.; Young, J.A.; Parrington, L.; Aimers, N. Do as I say: contradicting beliefs and attitudes towards sports concussion in Australia. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 35, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The times are they a-changing? Evolving attitudes in Australian exercise science students’ attitudes towards sports concussion. J. Sport Exerc. Sci. 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Baron, D. A., C. L. Reardon and S. H. Baron. Clinical sports psychiatry: An international perspective. Oxford, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

- Heron, N.; Elliott, J.; Jones, N.; Loosemore, M.; Kemp, S. Sports-related concussion (SRC) in road cycling: the RoadsIde heaD Injury assEssment (RIDE) for elite road cycling. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 54, 127–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H.T.; Atkins, S.; Dickinson, B.D. The magnitude of translational and rotational head accelerations experienced by riders during downhill mountain biking. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H.T.; Rylands, L.; Atkins, S.; Enright, K.; Roberts, S.J. Profiling of translational and rotational head accelerations in youth BMX with and without neck brace. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, N. "Australia's first female olympic cyclist julie speight donating brain for medical research." ABC News, 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-16/cyclist-julie-speight-donating-brain-to-science-cte-research/13252276. 25 February 2025.

- Roenigk, A. "Doctors say late bmx legend dave mirra had cte." ESPN, 2016. https://www.espn.com/action/story/_/id/15614274/bmx-legend-dave-mirra-diagnosed-cte. 25 Februrary 2025.

- Pearce, A.J.; Hoy, K.; Rogers, M.A.; Corp, D.T.; Maller, J.J.; Drury, H.G.; Fitzgerald, P.B. The Long-Term Effects of Sports Concussion on Retired Australian Football Players: A Study Using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.J.; King, D.; Kidgell, D.J.; Frazer, A.K.; Tommerdahl, M.; Suter, C.M. Assessment of Somatosensory and Motor Processing Time in Retired Athletes with a History of Repeated Head Trauma. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.J.; Tommerdahl, M.; King, D.A. Neurophysiological abnormalities in individuals with persistent post-concussion symptoms. Neuroscience 2019, 408, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beaumont, L.; Lassonde, M.; Leclerc, S.; Théoret, H. LONG-TERM AND CUMULATIVE EFFECTS OF SPORTS CONCUSSION ON MOTOR CORTEX INHIBITION. Neurosurgery 2007, 61, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beaumont, L.; Mongeon, D.; Tremblay, S.; Messier, J.; Prince, F.; Leclerc, S.; Lassonde, M.; Théoret, H. Persistent Motor System Abnormalities in Formerly Concussed Athletes. J. Athl. Train. 2011, 46, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadi, M.H.; Jordan, B.D. The Cumulative Effect of Repetitive Concussion in Sports. Am. J. Ther. 2001, 11, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Pascual-Leone, A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in neurology. Lancet Neurol. 2003, 2, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.J.; Fried, P.J.; Pascual-Leone, A.

- Rossi, S.; Hallett, M.; Rossini, P.M.; Pascual-Leone, A. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2009, 120, 2008–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A. J. and J. J. Maller. "Applications of meps." In A closer look at motor-evoked potentials. S. Jaberzadeh. 6. New York: Nova Science, 2019, 93-136.

- Wilson, S.; Lockwood, R.; Thickbroom, G.; Mastaglia, F. The muscle silent period following transcranial magnetic cortical stimulation. J. Neurol. Sci. 1993, 114, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonnell, M.N.; Orekhov, Y.; Ziemann, U. The role of GABAB receptors in intracortical inhibition in the human motor cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 2006, 173, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommerdahl, M.; Dennis, R.G.; Francisco, E.M.; Holden, J.K.; Nguyen, R.; Favorov, O.V. Neurosensory Assessments of Concussion. Mil. Med. 2016, 181, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, A.J.; Rist, B.; Fraser, C.L.; Cohen, A.; Maller, J.J. Neurophysiological and cognitive impairment following repeated sports concussion injuries in retired professional rugby league players. Brain Inj. 2018, 32, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.J.; Kidgell, D.J.; Tommerdahl, M.A.; Frazer, A.K.; Rist, B.; Mobbs, R.; Batchelor, J.; Buckland, M.E. Chronic Neurophysiological Effects of Repeated Head Trauma in Retired Australian Male Sport Athletes. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobounov, S.; Sebastianelli, W.; Moss, R. Alteration of posture-related cortical potentials in mild traumatic brain injury. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 383, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, B.; Berglund, P.; Rönnbäck, L. Mental fatigue and impaired information processing after mild and moderate traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2009, 23, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echemendia, R.J.; Meeuwisse, W.; McCrory, P.; Davis, G.A.; Putukian, M.; Leddy, J.; Makdissi, M.; Sullivan, S.J.; Broglio, S.P.; Raftery, M.; et al. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition (SCAT5). Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 848–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, J.K.; Nguyen, R.H.; Francisco, E.M.; Zhang, Z.; Dennis, R.G.; Tommerdahl, M. A novel device for the study of somatosensory information processing. J. Neurosci. Methods 2012, 204, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.J.; Hoy, K.; Rogers, M.A.; Corp, D.T.; Davies, C.B.; Maller, J.J.; Fitzgerald, P.B. Acute motor, neurocognitive and neurophysiological change following concussion injury in Australian amateur football. A prospective multimodal investigation. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.; Thickbroom, G.; Mastaglia, F. Transcranial magnetic stimulation mapping of the motor cortex in normal subjects. J. Neurol. Sci. 1993, 118, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H. J., B. Freriks, R. Merletti, D. Stegeman, J. Blok, G. Rau, C. Disselhorst-Klug and G. Hägg. European recommendations for surface electromyography. Enschede: Roessingh Research and Development The Netherlands, 1999.

- Chipchase, L.; Schabrun, S.; Cohen, L.; Hodges, P.; Ridding, M.; Rothwell, J.; Taylor, J.; Ziemann, U. A checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation to study the motor system: An international consensus study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 1698–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, A.J.; Thickbroom, G.W.; Byrnes, M.L.; Mastaglia, F.L. Functional reorganisation of the corticomotor projection to the hand in skilled racquet players. Exp. Brain Res. 2000, 130, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbrink, F. "The mep in clinical neurodiagnosis." In The oxford handbook of transcranial stimulation. E. M. Wasserman, C. M. Epstein, U. Ziemann, V. Walsh, T. Paus and S. H. Lisanby. 19. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, 237-83.

- Wilson, S.; Thickbroom, G.; Mastaglia, F. Comparison of the magnetically mapped corticomotor representation of a muscle at rest and during low-level voluntary contraction. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Mot. Control. 1995, 97, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Virgilio, T.G.; Hunter, A.; Wilson, L.; Stewart, W.; Goodall, S.; Howatson, G.; Donaldson, D.I.; Ietswaart, M. Evidence for Acute Electrophysiological and Cognitive Changes Following Routine Soccer Heading. EBioMedicine 2016, 13, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škarabot, J.; Mesquita, R.N.O.; Brownstein, C.G.; Ansdell, P. Myths and Methodologies: How loud is the story told by the transcranial magnetic stimulation-evoked silent period? Exp. Physiol. 2019, 104, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, M.; Rothwell, J. The cortical silent period: intrinsic variability and relation to the waveform of the transcranial magnetic stimulation pulse. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2004, 115, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, A.J.; Kidgell, D.J.; Frazer, A.K.; King, D.A.; Buckland, M.E.; Tommerdahl, M. Corticomotor correlates of somatosensory reaction time and variability in individuals with post concussion symptoms. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 2019, 37, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.J.; Kidgell, D.J.; Frazer, A.K.; Rist, B.; Tallent, J. Evidence of altered corticomotor inhibition in older adults with a history of repetitive neurotrauma. A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 453, 120777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.J.; Tallent, J.; Frazer, A.K.; Rist, B.; Kidgell, D.J. The Effect of Playing Career on Chronic Neurophysiologic Changes in Retired Male Football Players: An Exploratory Study Using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinley, M.; Hoffman, R.L.; Russ, D.W.; Thomas, J.S.; Clark, B.C. Older adults exhibit more intracortical inhibition and less intracortical facilitation than young adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1988.

- Petit, K.M. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool-5 (SCAT5): Baseline Assessments in NCAA Division I Collegiate Student-Athletes. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 13, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, R.; Falvey, E.; Fuller, G.W.; Hislop, M.D.; Patricios, J.; Raftery, M. Sport Concussion Assessment Tool: baseline and clinical reference limits for concussion diagnosis and management in elite Rugby Union. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.; Hume, P.; Tommerdahl, M. Use of the brain-gauge somatosensory assessment for monitoring recovery from concussion: A case study. J Physiother Res 2018, 2, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Reneker, J.C.; Babl, R.; Flowers, M.M. History of concussion and risk of subsequent injury in athletes and service members: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pr. 2019, 42, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, A.L.; Nagai, T.; Webster, K.E.; Hewett, T.E. Musculoskeletal Injury Risk After Sport-Related Concussion: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Sports Med. 2018, 47, 1754–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, A.L.; Shirley, M.B.; Schilaty, N.D.; Larson, D.R.; Hewett, T.E. Effect of a Concussion on Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk in a General Population. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.H.; Kotlier, J.L.; Fathi, A.; Castonguay, J.; Thompson, A.A.; Bolia, I.K.; Petrigliano, F.A.; Liu, J.N.; Weber, A.E.; Gamradt, S.C. NCAA football players are at higher risk of upper extremity injury after first-time concussion. Physician Sportsmed. 2024, 52, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.L.; Duenkel, N.; Dunlop, R.; Russell, G. Evaluation of Single-Leg Standing Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery and Rehabilitation. Phys. Ther. 1994, 74, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock-Saxton, J. E. Sensory changes associated with severe ankle sprain. Scan J Rehab Med 1995, 27, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).