Introduction

Bovine milk protein consists of two major fractions: whey (~20%) and micellar casein (~80%). Both protein fractions are among the highest-quality sources of dietary protein based on indexes of protein quality (Wolfe, 2015; Phillips, 2016; Gorissen et al., 2018; Deglaire et al., 2009; Mathai et al., 2017) yet distinct plasma amino acid (AA) profiles are observed following consumption. Specifically, ingestion of whey protein (WP) results in rapid and substantial increases in postprandial plasma essential amino acids (EAA) including leucine (LEU) - thus being characterised as a rapidly digested protein (Boirie et al., 1997). In contrast, micellar casein coagulates and precipitates in the low pH environment of the stomach following ingestion (Mahé et al., 1996). This results in casein exhibiting a slower, protracted aminoacidaemia (Boirie et al., 1997). Previous research has highlighted muscle protein synthesis (MPS) responses to be superior following WP consumption (Tang et al., 2009; Burd et al., 2012) or with no differences between other ‘high-quality’ (e.g., casein) protein sources (Tipton et al., 2004; Reitelseder et al., 2011; Dideriksen et al., 2011). Such apparent conflicting results may be influenced by adjuvant exercise in the protocol, feeding strategy (i.e., pulse/bolus), or the timing of skeletal muscle (SKM) biopsies for the quantification of MPS.

β-lactoglobulin (BLG) is a protein found within WP and accounts for 45 –57% of bovine whey proteins (Tulipano et al., 2011; Mose et al., 2021; Farrell et al., 2004). BLG is a protein source naturally abundant in EAA, especially LEU, such that the LEU content of BLG exceeds the constituent LEU content of WP by ~50% (~15% vs. ~10%) (Mose et al., 2021). Crucially, LEU is the most potent EAA for stimulating MPS (Smith et al., 1992; Wilkinson et al., 2013) and a key nutrient regulator of translation initiation enacting the postprandial acceleration of MPS (Anthony et al., 2000b). Subsequently, there has been increasing interest in the role of LEU in enhancing SKM anabolism, and ultimately increasing and/or maintaining SKM mass, especially in the context of ageing, exercise, and inactivity (Kumar et al., 2009; Ely et al., 2023). Exemplifying this, previous studies have highlighted a positive role for adjuvant LEU for the regulation of MPS (e.g., Katsanos et al., 2006; Churchward-Venne et al., 2012; Churchward-Venne et al., 2014; Bukhari et al., 2015; Wilkinson et al., 2018); however others have demonstrated no beneficial effect of additive LEU in a mixed EAA/protein solution (Koopman et al., 2008; De Andrade et al., 2020) or following free LEU supplementation aiming to enhance lean mass (Verhoeven et al., 2009; Aguiar et al., 2017) in a more chronic setting. Despite this, peak plasma LEU concentrations and postprandial rates of MPS have been correlated in cohorts of young (Cuthbertson et al 2005; Witard et al., 2014) and older men (Pennings et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2015), which to our knowledge, is undetermined in women.

Although BLG, specifically, has a high LEU content - a “ceiling effect” may exist regarding LEU availability and stimulation of MPS, as evidenced by a plateau in the dose-response of MPS to ingested WP in young healthy men (Cuthbertson et al., 2005; Witard et al., 2014). Research efforts have, therefore, been focused on investigating low-protein doses that contain higher amounts of LEU, aiming to maximise MPS in individuals who e.g., are unable to consume the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of protein in order to preserve lean muscle mass, for various reasons. Subsequently, previous research has highlighted that suboptimal doses of protein or EAA mixes enriched with LEU can enhance MPS and provide a similar anabolic response to larger doses (e.g., 40 g) of WP in both younger (Churchward-Venne et al., 2012; Churchward-Venne et al., 2014) and older individuals (Kumar et al., 2009; Bukhari et al., 2015; Wilkinson et al., 2018). As the impact of BLG, compared to other protein sources, has not been determined we investigated the efficacy of moderate-dose (~10g protein) BLG supplementation, compared to an isonitrogenous whey protein isolate (WPI, ~10g protein) on muscle anabolism (MPS), in rested and [unilateral] exercised conditions, in young healthy men.

Methodology

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the University of Nottingham Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (reference number: FMHS 207-0221), registered at clinicaltrials.gov (registration number: NCT05701202) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Participant Characteristics and Screening

Ten young male participants (26±2 years; 179±2 cm; 81±3 kg) were recruited via word of mouth, social media adverts on the research group pages and adverts in the local community. After receiving a detailed information sheet outlining the research study, interested participants attended a screening session to assess their eligibility. This session included a previous medical history discussion, measures of height, weight and blood pressure, and an electrocardiogram. Participant eligibility was confirmed by a clinician after assessing all screening results against pre-determined exclusion criteria (BMI <18 or >35 kg/m2, active cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or respiratory disease, any metabolic disease or malignancy, clotting dysfunction, a history of, or current neurological or musculoskeletal conditions, lactose intolerance). Finally, a unilateral knee extension 1-RM assessment was conducted at this session to measure strength of the dominant leg (Leisure Lines LTD, Jan 2000, Iso Lever) for determination ofacute resistance exercise (RE) intensity on the assessment days.

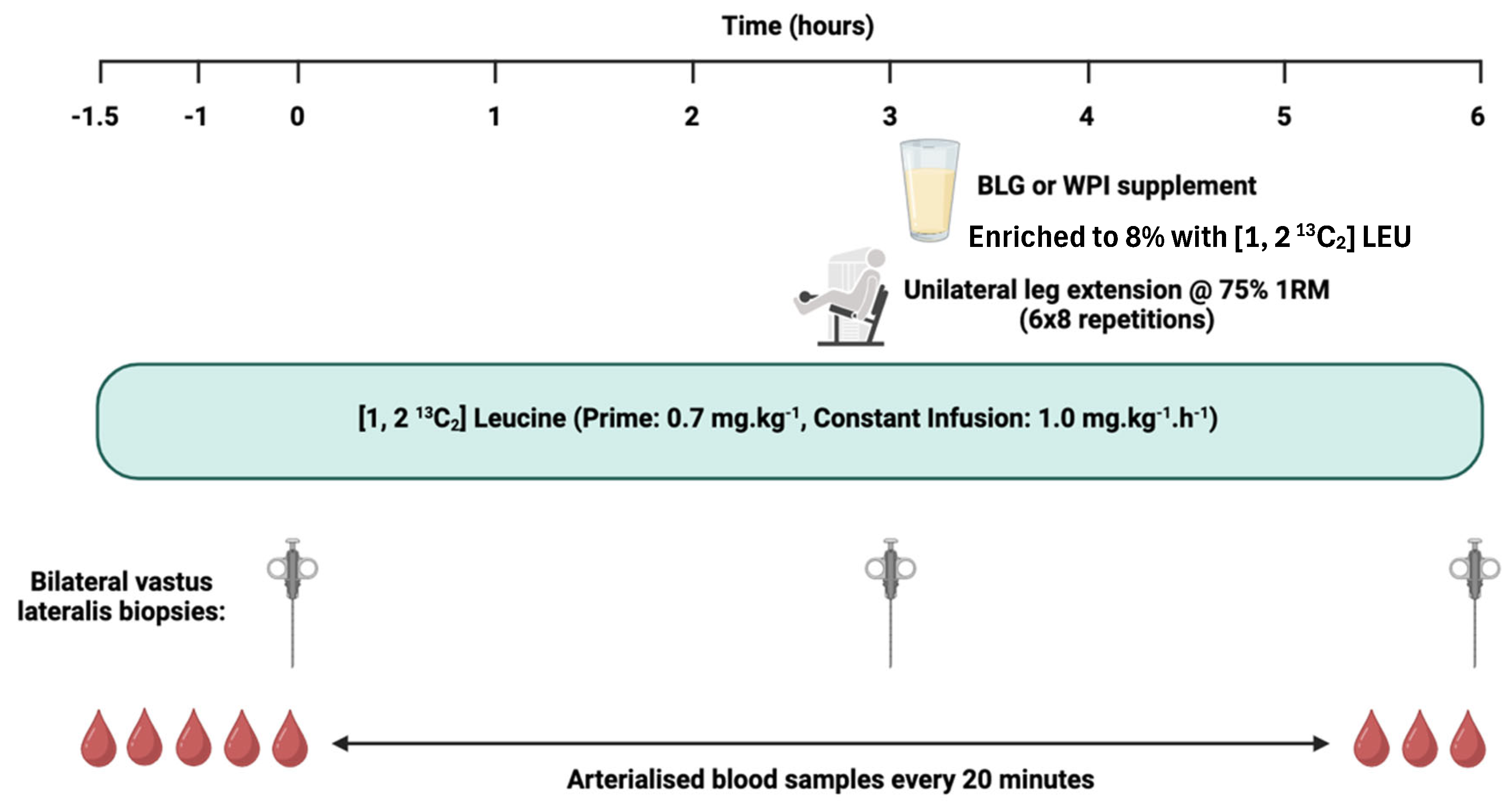

Experimental protocol

Participants were randomly assigned to consume BLG or WPI (~10 g protein) on their first assessment day, with the other supplement consumed on their second. Each visit was separated by a washout period of 21 to 42 days, although almost all participants completed their second visit within 4 weeks. Prior to completion of their first assessment visit, participants were asked to complete a four-day diet diary recording all food and drink consumed. Nutritics Food Management Software (

https://www.nutritics.com/en/) was used to determine dietary protein intake. Participants were requested not to alter their habitual dietary intake for the duration of the study.

On each assessment day, participants reported to the laboratory at 0800 hours, having undergone an overnight fast (≥ 10 hours, water

ad libitum) and refrained from intense exercise for at least 72 hours. Initially, two venous cannulae were inserted, one into the antecubital fossa for [1,2

13C

2] LEU stable isotope tracer infusion (99 Atoms % of [1, 2

13C

2 LEU], Cambridge Isotopes Limited, Cambridge, MA, USA), and one was placed retrograde into a contralateral dorsal vein of the opposite hand for blood sampling. This hand was placed in a heated box at ~55°C to create an arteriovenous shunt of blood by vasodilation of veins in the fingers, allowing arterialised-venous blood sampling (Abumrad et al., 1981). Blood samples were collected at baseline and every 20 minutes thereafter, until conclusion of the assessment visit. Plasma samples were collected for the quantification of AA and insulin, and α-ketoisocaproate (α-KIC) enrichment. Following baseline blood samples, a primed, continuous infusion (0.7 mg.kg

-1, 1.0 mg.kg

-1.h

-1) of [1, 2

13C

2] LEU tracer was initiated and continued for the duration of the assessment visit over 7.5 hours . At timepoints 0 (i.e., following 1.5 hours of tracer infusion), 3 and 6 hours, after induction of local anaesthetic (~5 mL 1% lignocaine), bilateral skeletal muscle (SKM) biopsies were collected from the

vastus lateralis muscle (~100–200 mg of tissue) under sterile conditions using a standard conchotome technique. The muscle tissue was washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline to remove excess blood, dissected free of visible fat and connective tissue, then snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80

C until further analysis. SKM biopsies at timepoints 0 and 3 hours allowed for postabsorptive MPS to be quantified, whereas biopsies at 3 and 6 hours allowed for quantification of postprandial MPS in the fed, rested state (FED) and the fed, exercised (FED-EX) state. Approximately 20 minutes before the second set of biopsies (i.e., at 3 hours), participants performed a bout of unilateral RE (leg extension; 6 sets of 8 repetitions at 75% 1RM with a 2-minute inter-set rest period, on the dominant leg (Iso Lever, Leisure Lines LTD)). Immediately after the second set of biopsies, participants ingested the protein feed that they were randomly assigned (

Figure 1). Each protein supplement was dissolved in ~250 mL water and consumed as a bolus. To minimise perturbations in plasma isotopic enrichment, beverages were enriched to 8% with [1, 2

13C

2] LEU tracer. The AA composition of the protein supplements is outlined in

Table 1.

Sample Analysis

Plasma Insulin

Plasma insulin concentrations were measured on high-sensitivity human insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assays (Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

Plasma EAA Concentrations and α-KIC Enrichment

For plasma AA analyses, samples were prepared as previously described (Wilkinson et al., 2018). Briefly, 10 µL of a mix of stable isotopically labelled internal standards were added to 100 µL of plasma, treated with urease and then deproteinised with 0.5 mL ice-cold ethanol at -20C for 20 minutes. Following centrifugation (17,000 g for 5 minutes at 4C), the supernatant was decanted and evaporated under nitrogen to dryness. The quinoxalinol KIC derivative was then formed by addition of o-phenylenediamine solution in HCl and extracted with 2 mL of ethyl acetate. Both solvent (containing quinoxalinol KIC) and aqueous (containing AA) layers were evaporated to dryness and derivatised to their t-butyldimethylsilyl (tBDMS) esters. AA concentrations were quantified against a standard curve of known concentrations alongside α-KIC enrichment using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS; Trace 1300 - ISQ, Thermo Scientific, Hemel Hempstead, UK).

Myofibrillar Fractional Synthetic Rate

Myofibrillar proteins were isolated, hydrolysed, and derivatised using our standard techniques (Wilkinson et al., 2013, 2018). Briefly, 20–30 mg of muscle biopsy tissue was homogenized in ice-cold homogenization buffer (50 mM TriseHCL (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaF, 10 mM ß-glycerophosphate disodium salt, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM activated Na3VO4 [all Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK]) and a complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, West Sussex, UK) at 10 µL.µg-1 of tissue. Following centrifugation at 13,000 g for 15 minutes at 4C, the resulting insoluble pellet was washed three times with homogenization buffer to remove excess free AA and solubilised in 0.3 M NaOH to aid separation of the soluble myofibrillar fraction from the insoluble collagen fraction by subsequent centrifugation. The soluble myofibrillar fraction was then precipitated using 1 M PCA, pelleted by centrifugation and washed twice with 70% ethanol. The protein-bound AA become released by acid hydrolysis using 1 mL 0.1 M HCL and 1 mL of Dowex ion-exchange resin (50W-X8-200) overnight at 110C. The free AA were purified, derivatised and the fractional synthetic rate (FSR) of the myofibrillar proteins was calculated using the precursor-product equation below:

FSR (%/h) = × 100

where Em is the change in enrichment of bound [1,2 13C2] LEU in two sequential biopsies, t is the time interval between two biopsies in hours, and EP is the plasma α- KIC enrichment (a surrogate precursor of the LEU intramuscular pool).

Statistical Analysis

Data was checked for normal distribution using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Myofibrillar FSR (i.e., MPS) and plasma insulin concentrations were analysed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA (supplement × time) with multiple comparisons analysis using Sidak’s correction. Plasma AA concentrations were analysed via mixed-effects analysis (supplement × time) with multiple comparisons analysis using Sidak’s correction. Integrated area under the curve above baseline (iAUC) analysis was determined for plasma EAA, BCAA and LEU concentrations and analysed via Student’s paired t-test. All analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). The alpha level of significance was set at P< 0.05. Data is presented as mean±SEM unless stated otherwise.

Results

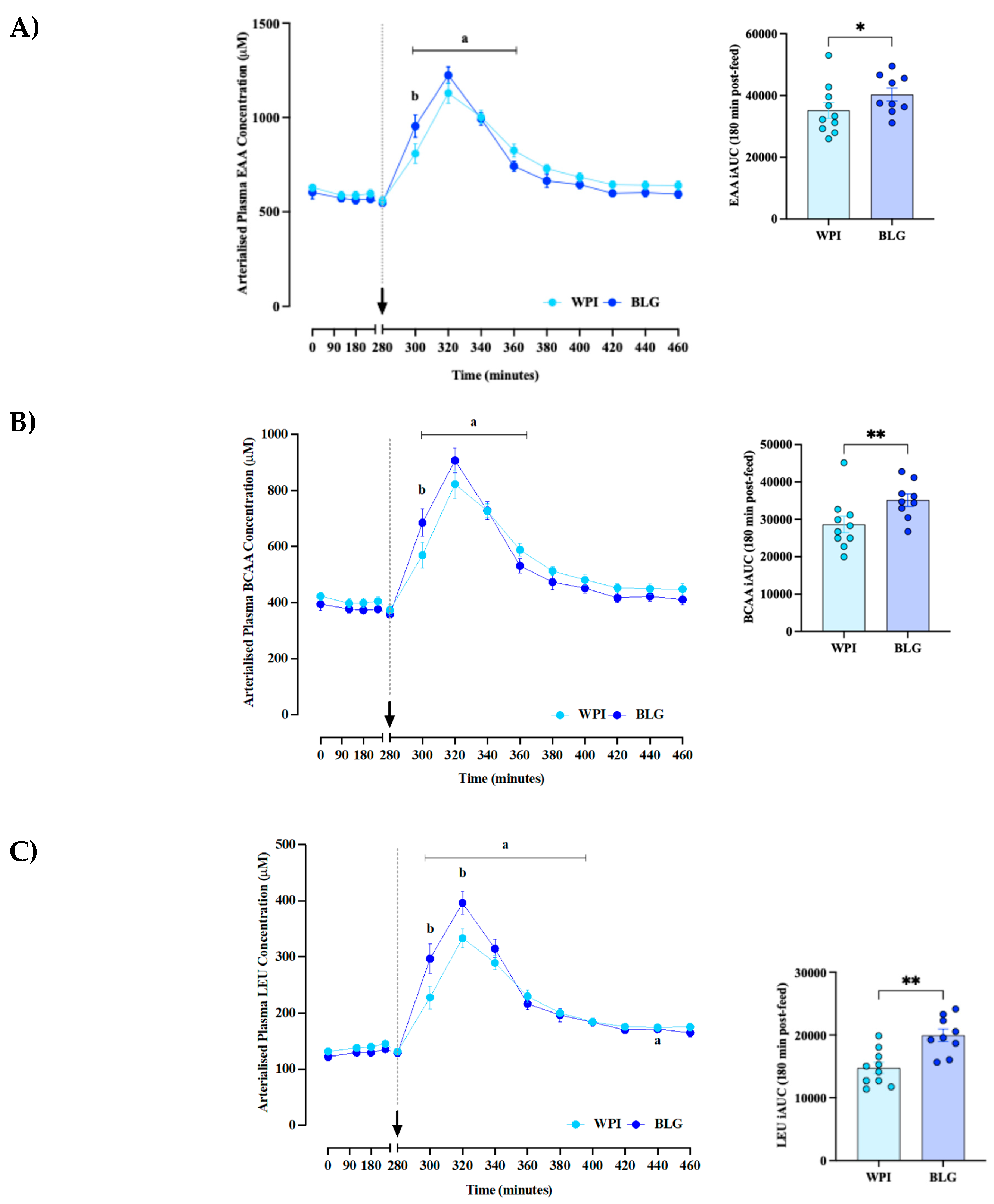

Plasma Leucine, BCAA and EAA Concentrations

Arterialised plasma LEU (main time effect:

P<0.0001; time × supplement effect:

P<0.0001;

Figure 2A) and BCAA (main time effect:

P<0.0001; time × supplement effect:

P=0.002;

Figure 2B) concentrations increased rapidly in both WPI and BLG conditions, peaking at ~40 minutes following feeding, before returning to baseline at 100–120 minutes post-feed. With BLG, plasma and BCAA concentrations rose significantly more than the WPI in the first 40 minutes post-feed, with peak leucinaemia also being greater (396±20 μM vs 334±17 μM;

P =0.0009). In terms of AUC analyses, Leu AUC was significantly different between the WPI and BLG groups (14762 ± 2785 uM.min vs 19954 ± 2970 uM.min, p = 0.0072). Similarly BCAA AUC was significantly different between WPI and BLG groups (28654 ± 6970 μM.min vs 35132 ± 4962 μM.min, p = 0.0014). EAA AUC was also significantly different between WPI and BLG groups (35210 ± 8142 μM.min vs 40321 ± 6275 μM.min, p = 0.023) with BLG just showing superior aminoacidaemia across the spectrum of EAA clusters.

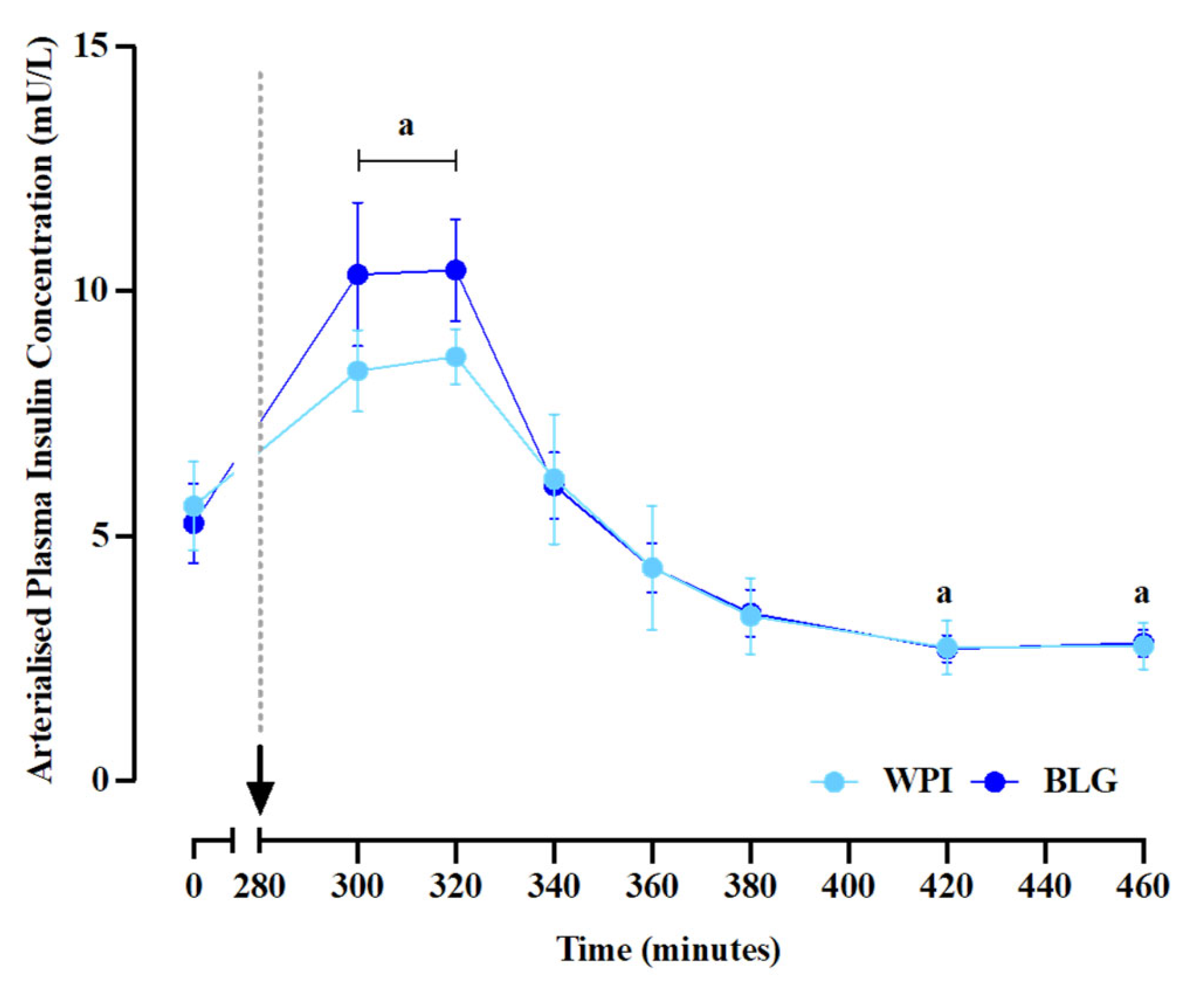

Plasma insulin Concentrations

Plasma insulin concentrations (main time effect:

P<0.0001;

Figure 2C) increased above postabsorptive levels, peaking at 8.7±1.8 mU/L and 10.4±1.0 mU/L for WPI and BLG conditions, respectively. For WPI, plasma insulin concentrations became lower than baseline values at 140 and 180 minutes following feeding (both

P=0.02). No differences in plasma insulin concentrations were observed between supplements at any time point or for iAUC. The arrow and dotted line indicate the consumption of protein supplements.

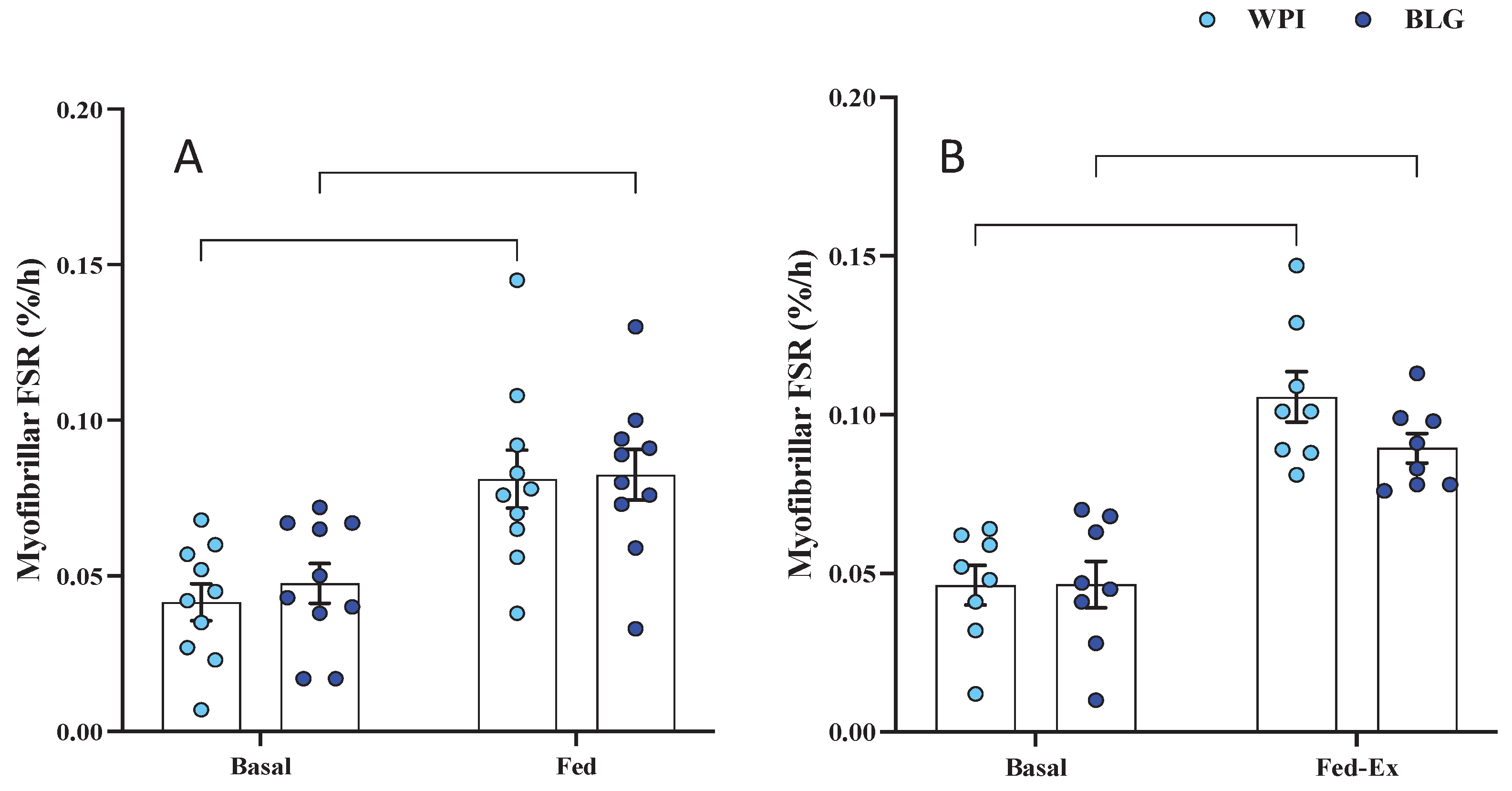

Muscle Protein Synthesis

Baseline rates of myofibrillar FSR (i.e., MPS) did not differ between legs (i.e., fasted vs. fasted-ex leg) or across conditions (i.e., fasted/fasted-ex legs for WPI vs. BLG groups). FED MPS rates increased (main time effect:

P < 0.0001;

Figure 3A) in response to both WPI (0.042±0.006 %/h vs. 0.081±0.009 %/h;

P=0.0006) and BLG (0.048±0.006 %/h vs. 0.083±0.008 %/h;

P=0.0019) , with no difference in response between supplements. Likewise, FED-EX MPS rates (

n=8; main time effect:

P<0.0001;

Figure 3B) increased following both WPI (0.046±0.006 %/h vs. 0.106±0.008 %/h;

P<0.0001) and BLG (0.047±0.007 %/h vs. 0.090±0.005 %/h;

P=0.0008), with no difference between supplements.

Figure 3.

Plasma insulin concentrations. Data are presented as mean±SEM. a: significant difference vs. basal (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

Plasma insulin concentrations. Data are presented as mean±SEM. a: significant difference vs. basal (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

The effects of whey protein isolate (WPI) and β-lactoglobulin (BLG) on skeletal muscle myofibrillar fractional synthetic rate in response to feeding (FED; A) and feeding-plus-acute resistance exercise (FED-EX (n = 8); B). Data presented as mean (bars)±SEM, with individual data points overlaid. **: P< 0.01; ***: P<0.001; ****: P<0.0001.

Figure 4.

The effects of whey protein isolate (WPI) and β-lactoglobulin (BLG) on skeletal muscle myofibrillar fractional synthetic rate in response to feeding (FED; A) and feeding-plus-acute resistance exercise (FED-EX (n = 8); B). Data presented as mean (bars)±SEM, with individual data points overlaid. **: P< 0.01; ***: P<0.001; ****: P<0.0001.

Discussion

The use of LEU-enriched EAA/WP has gained traction over recent years as an alternative means to maximise MPS at lower, suboptimal protein doses (Kumar et al., 2009; Wilkinson et al., 2013; Bukhari et al., 2015; Atherton et al., 2017). Such research studies often involved the addition of free-LEU to existing WP and/or EAA mixtures, rather than adopting a strategy of natural enrichment. As such, we compared the effects of a novel WP isolate with a naturally superior LEU content, BLG; to an isonitrogenous WPI at a ‘suboptimal’ dose of protein (10g), on the effects of muscle anabolism in FED and FED-EX states in young healthy males.

Regarding plasma observations, we noted EAA, BCAA and LEU concentrations to significantly increase following feeding of both BLG and WPI. In both supplements, we observed peak plasma EAA, BCAA and LEU concentrations to occur at ~40 minutes following feeding. BLG notably achieved greater peak and AUC leucinemia, with EAA, BCAA and LEU concentrations also exhibiting a greater rise over the first 20 minutes post-feed. This mirrors results observed in previous research studies with supplements containing greater LEU content (e.g., Churchward-Venne et al., 2012; Bukhari et al., 2015; Wilkinson et al., 2018) and in previous studies investigating BLG (Mose et al., 2021; Smedegaard et al., 2021 to be added to REF). BLG and WPI also both elicited a predictable insulinotropic response to feeding, with similar increases in plasma insulin following feeding, in agreement with a similar study wherein larger protein supplements (25g BLG or WPI) were given (Smedegaard et al., 2021).

In terms of MPS, BLG, at a dose deemed suboptimal for maximal muscle anabolism (Cuthbertson et al; 2005; Witard et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2015), significantly increased rates of MPS in both the FED and FED-EX states, with no group differences being observed. Previous research demonstrated that ~10g EAA in non-exercised conditions (Cuthbertson et al., 2005), or ~8.6g EAA in exercised conditions (Moore et al., 2009), was sufficient to stimulate MPS robustly and maximally in healthy young participants. In the current study, both BLG and WPI had lower quantities of EAA than thought optimal (5.6g vs. 4.7g EAA, respectively), yet robust stimulation of MPS was still achieved. We also note the LEU content of BLG (~1.57 g) and WPI (~1.02 g) were quite different, however MPS was indistinguishable between BLG and WPI (at least in young males where anabolic resistance is less likely). Although, BLG contained ~50% more Leu, the difference in bioavailable Leu was not as large, perhaps reflecting splanchnic utilisation, which minimized any potential dose effect of increased Leu. Similar to these findings, previous studies have demonstrated that a protein dose of 6.3g WP (~0.75g LEU) robustly stimulated fed state MPS over 3h in young individuals, comparable to 25g of Whey (Churchward-Venne et al., 2012). Furthermore, in a study by Katsanos et al., young individuals showed a similar MPS response when consuming 6.7 g EAA containing either 26% LEU (1.7g) or 41% LEU (2.8g) (Katsanos et al., 2006). Therefore, we contend that in healthy young men, the LEU content provided by ~10g of either BLG (1.57g) or WPI (1.02g) appears to be sufficient to robustly stimulate MPS similarly when adequate amounts of the other EAA are provided. Notably, other EAA than LEU also stimulate MPS which previous classical studies demonstrated when giving flooding dose of either valine, phenylalanine or threonine individually, to humans (Smith et al., 1998).

With research utilising LEU-enriched protein supplementation at lower than optimal doses, questions have arisen as to whether a true dose-response to protein feeding exists if maximal MPS stimulation can be achieved by other means i.e., LEU-enriched EAA. Indeed, even though suboptimal protein doses with enriched LEU have elicited comparable MPS responses compared to larger doses of protein, this is often only in the early phase (~90-120 min) of MPS stimulation – particularly in the absence of exercise (Churchward-Venne et al., 2012; Bukhari et al., 2015; Wilkinson et al., 2018). In some circumstances, larger doses of WP or LEU supplementation have been evidenced to sustain the increase in or lead to greater stimulation in MPS in young men over longer assessment periods (i.e., ~4–5 hours) and where exercise is a variable to nutrition alone (Churchward-Venne et al., 2014; Wilkinson et al., 2018). Further work utilising a dose of protein per kg body weight or lean body mass is required to fully elucidate the existence of an MPS dose response to protein or LEU intake. In sum, there is good evidence of a dose-response of MPS to protein, EAA/LEU ingestion (Cuthbertson et al., 2005; Witard et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2012; Glynn et al., 2010), and that there is a maximal response to providing an additional AA substrate of around 20g WP, 10g EAA, or 3g LEU in young males; despite stimulation being prolonged by prior exercise (Atherton et al., 2017).

In conclusion a suboptimal 10g dose of BLG in young individuals leads to significant increases in plasma EAA, BCAA, and insulin concentrations with greater plasma leucinaemia achieved compared to WPI, in addition to significant stimulation of MPS in the FED and FED-EX states. Future research should assess the impact of BLG on leucine kinetics and muscle anabolism in females – the lack of inclusion being an accepted limitation of this initial work. Also in older adults and/or frail, clinical populations who may benefit from the superior LEU content due to their anabolic resistance to protein nutrition, reduced ability to utilise large amounts of protein and amino acids, and the satiating effect of protein impacting upon their macronutrient intake.

Funding

This work was funded through a Medical Research Council (MRC) industrial CASE (iCASE) studentship funded ny the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) in partnership with PhD stipend uplift (to IAE) and project research funding being received from Arla Foods Ingredients. The MRC-Versus Arthritis Centre for Musculoskeletal Ageing Research awarded to the Universities of Nottingham and Birmingham (grant no. MR/P021220/1) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK, Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre also supported associated infrastructure.

Conflicts of Interest

This study was funded by Arla Food Ingredients (AFI) with whom MSL is an employee. BEP and PJA declare honoraria and research funding from Abbott Nutrition (BEP) and honoraria, consultancy, and research funding from AFI, Abbott Nutrition and Fresenius-Kabi (PJA).

Abbreviations

1RM, 1 repetition maximum; AA, amino acids; BLG, β-lactoglobulin; EAA, essential amino acids; FED, feeding-only; FED-EX, feeding-plus-exercise; FSR, fractional synthetic rate; GIP, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide; iAUC, integrated area under the curve above baseline; LEU, leucine; MPB, muscle protein breakdown; MPS, muscle protein synthesis; NEAA, non-essential amino acids; RDA, recommended daily allowance; RE, resistance exercise; SKM, skeletal muscle; WP, whey protein; WPI, whey protein isolate.

References

- ABDULLA, H. , SMITH, K., ATHERTON, P. J. & IDRIS, I. Role of insulin in the regulation of human skeletal muscle protein synthesis and breakdown: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia, 2016, 59, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- ABUMRAD, N. N. , RABIN, D., DIAMOND, M.P. AND LACY, W.W. Use of a heated superficial hand vein as an alternative site for the measurement of amino acid concentrations and for the study of glucose and alanine kinetics in man. Metabolism, 1981, 30, 936–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AGUIAR, A. F. , GRALA, A. P., DA SILVA, R. A., SOARES-CALDEIRA, L. F., PACAGNELLI, F. L., RIBEIRO, A. S., DA SILVA, D. K., DE ANDRADE, W. B. & BALVEDI, M. C. W. Free leucine supplementation during an 8-week resistance training program does not increase muscle mass and strength in untrained young adult subjects. Amino Acids, 2017, 49, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- ANTHONY, J. C. , YOSHIZAWA, F., ANTHONY, T. G., VARY, T. C., JEFFERSON, L. S. & KIMBALL, S. R. Leucine stimulates translation initiation in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats via a rapamycin-sensitive pathway. J Nutr, 2000, 130, 2413–2419. [Google Scholar]

- ATHERTON, P. J. , ETHERIDGE, T., WATT, P. W., WILKINSON, D., SELBY, A., RANKIN, D., SMITH, K. & RENNIE, M. J. Muscle full effect after oral protein: time-dependent concordance and discordance between human muscle protein synthesis and mTORC1 signaling. Am J Clin Nutr, 2010, 92, 1080–8. [Google Scholar]

- ATHERTON, P. J. , KUMAR, V., SELBY, A. L., RANKIN, D., HILDEBRANDT, W., PHILLIPS, B. E., WILLIAMS, J. P., HISCOCK, N. & SMITH, K. Enriching a protein drink with leucine augments muscle protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young and older men. Clin Nutr 2017, 36, 888–895. [Google Scholar]

- BOIRIE, Y. , DANGIN, M., GACHON, P., VASSON, M-P., MAUBOIS, J-L. & BEAUFRERE, B. Slow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USE 1997, 94, 14930–14935. [Google Scholar]

- BUKHARI, S. S. , PHILLIPS, B. E., WILKINSON, D. J., LIMB, M. C., RANKIN, D., MITCHELL, W. K., KOBAYASHI, H., GREENHAFF, P. L., SMITH, K. & ATHERTON, P. J. Intake of low-dose leucine-rich essential amino acids stimulates muscle anabolism equivalently to bolus whey protein in older women at rest and after exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2015, 308, E1056–65. [Google Scholar]

- BURD, N. A. , YANG, Y., MOORE, D. R., TANG, J. E., TARNOPOLSKY, M. A. & PHILLIPS, S. M. Greater stimulation of myofibrillar protein synthesis with ingestion of whey protein isolate v. micellar casein at rest and after resistance exercise in elderly men. Br J Nutr 2012, 108, 958–62. [Google Scholar]

- CHURCHWARD-VENNE, T. A. , BREEN, L., DI DONATO, D. M., HECTOR, A. J., MITCHELL, C. J., MOORE, D. R., STELLINGWERFF, T., BREUILLE, D., OFFORD, E. A., BAKER, S. K. & PHILLIPS, S. M. Leucine supplementation of a low-protein mixed macronutrient beverage enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis in young men: a double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2014, 99, 276–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- CHURCHWARD-VENNE, T. A. , BURD, N. A., MITCHELL, C. J., WEST, D. W., PHILP, A., MARCOTTE, G. R., BAKER, S. K., BAAR, K. & PHILLIPS, S. M. Supplementation of a suboptimal protein dose with leucine or essential amino acids: effects on myofibrillar protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in men. J Physiol 2012, 590, 2751–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- CUTHBERTSON, D. , SMITH, K., BABRAJ, J., LEESE, G., WADDELL, T., ATHERTON, P., WACKERHAGE, H., TAYLOR, P. M. & RENNIE, M. J. Anabolic signaling deficits underlie amino acid resistance of wasting, aging muscle. FASEB J 2005, 19, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DE ANDRADE, I. T. , GUALANO, B., HEVIA-LARRAIN, V., NEVES-JUNIOR, J., CAJUEIRO, M., JARDIM, F., GOMES, R. L., ARTIOLI, G. G., PHILLIPS, S. M., CAMPOS-FERRAZ, P. & ROSCHEL, H. Leucine Supplementation Has No Further Effect on Training-induced Muscle Adaptations. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2020, 52, 1809–1814. [Google Scholar]

- DEGLAIRE, A. , BOS, C., TOME, D. & MOUGHAN, P. J. Ileal digestibility of dietary protein in the growing pig and adult human. Br J Nutr 2009, 102, 1752–9. [Google Scholar]

- DIDERIKSEN, K. J. , REITELSEDER, S., PETERSEN, S. G., HJORT, M., HELMARK, I. C., KJAER, M. & HOLM, L. Stimulation of muscle protein synthesis by whey and caseinate ingestion after resistance exercise in elderly individuals. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011, 21, e372–83. [Google Scholar]

- DRUMMOND, M. J. , FRY, C. S., GLYNN, E. L., DREYER, H. C., DHANANI, S., TIMMERMAN, K. L., VOLPI, E. & RASMUSSEN, B. B. Rapamycin administration in humans blocks the contraction-induced increase in skeletal muscle protein synthesis. J Physiol 2009, 587, 1535–46. [Google Scholar]

- ELY, I. A. , PHILLIPS, B. E., SMITH, K., WILKINSON, D. J., PIASECKI, M., BREEN, L., LARSEN, M. S. & ATHERTON, P. J. A focus on leucine in the nutritional regulation of human skeletal muscle metabolism in ageing, exercise and unloading states. Clin Nutr 2023, 42, 1849–1865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- FARRELL, H. M. J. , JIMENEZ-FLORES, R., BLECK, G.T., BROWN, E.M., BUTLER, J.E., CREAMER, L.K., HICKES, C.L., HOLLAR, C.M., NG-KWAI-HANG, K.F. AND SWAISGOOD, H.E. Nomenclature of the proteins of Cows’ milk - Sixth revision. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 1641–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GLYNN, E. L. , FRY, C. S., DRUMMOND, M. J., TIMMERMAN, K. L., DHANANI, S., VOLPI, E. & RASMUSSEN, B. B. Excess leucine intake enhances muscle anabolic signaling but not net protein anabolism in young men and women. J Nutr 2010, 140, 1970–6. [Google Scholar]

- KATSANOS, C. S. , KOBAYASHI, H., SHEFFIELD-MOORE, M., AARSLAND, A. & WOLFE, R. R. A high proportion of leucine is required for optimal stimulation of the rate of muscle protein synthesis by essential amino acids in the elderly. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2006, 291, E381–7. [Google Scholar]

- KOOPMAN, R. , VERDIJK, L. B., BEELEN, M., GORSELINK, M., KRUSEMAN, A. N., WAGENMAKERS, A. J., KUIPERS, H. & VAN LOON, L. J. Co-ingestion of leucine with protein does not further augment post-exercise muscle protein synthesis rates in elderly men. Br J Nutr 2008, 99, 571–80. [Google Scholar]

- KUMAR V, ATHERTON P, SMITH K, RENNIE MJ. Human muscle protein synthesis and breakdown during and after exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009 Jun;106(6):2026-39.

- MAHÉ, S. , ROOS, N., BENAMOUZIG, R., DAVIN, L., LUENGO, C., GAGNON, L., GAUSSERGÈS, N., RAUTUREAU, J. AND TOMÉ, D. Gastrojejunal kinetics and the digestion of [15N]beta-lactoglobulin and casein in humans: the influence of the nature and quantity of the protein. Am J Clin Nutr 1996, 63, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MATHAI, J. K. , LIU, Y. & STEIN, H. H. Values for digestible indispensable amino acid scores (DIAAS) for some dairy and plant proteins may better describe protein quality than values calculated using the concept for protein digestibility-corrected amino acid scores (PDCAAS). Br J Nutr 2017, 117, 490–499. [Google Scholar]

- MOORE, D. R. , CHURCHWARD-VENNE, T. A., WITARD, O., BREEN, L., BURD, N. A., TIPTON, K. D. & PHILLIPS, S. M. Protein ingestion to stimulate myofibrillar protein synthesis requires greater relative protein intakes in healthy older versus younger men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015, 70, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- MOORE, D. R. , ROBINSON, M. J., FRY, J. L., TANG, J. E., GLOVER, E. I., WILKINSON, S. B., PRIOR, T., TARNOPOLSKY, M. A. & PHILLIPS, S. M. Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. Am J Clin Nutr 2009, 89, 161–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- MOSE, M. , MOLLER, N., JESSEN, N., MIKKELSEN, U. R., CHRISTENSEN, B., RAKVAAG, E., HARTMANN, B., HOLST, J. J., JORGENSEN, J. O. L. & RITTIG, N. beta-Lactoglobulin Is Insulinotropic Compared with Casein and Whey Protein Ingestion during Catabolic Conditions in Men in a Double-Blinded Randomized Crossover Trial. J Nutr 2021, 151, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar]

- PENNINGS, B. , BOIRIE, Y., SENDEN, J. M., GIJSEN, A. P., KUIPERS, H. & VAN LOON, L. J. Whey protein stimulates postprandial muscle protein accretion more effectively than do casein and casein hydrolysate in older men. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 93, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- REITELSEDER, S. , AGERGAARD, J., DOESSING, S., HELMARK, I. C., LUND, P., KRISTENSEN, N. B., FRYSTYK, J., FLYVBJERG, A., SCHJERLING, P., VAN HALL, G., KJAER, M. & HOLM, L. Whey and casein labeled with L-[1-13C]leucine and muscle protein synthesis: effect of resistance exercise and protein ingestion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2011, 300, E231–42. [Google Scholar]

- SMITH K, BARUA JM, WATT PW, SCRIMGEOUR CM, RENNIE MJ. Flooding with L-[1-13C]leucine stimulates human muscle protein incorporation of continuously infused L-[1-13C]valine. Am J Physiol. 1992 Mar;262(3 Pt 1):E372-6.

- SMITH, K. , REYNOLDS, N., DOWNIE, S., PATEL, A. & RENNIE, M.J. Effects of flooding amino acids on incorporation of labeled amino acids into human muscle protein. Am J Physiol 1998, 275, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- TANG, J. E. , MOORE, D. R., KUJBIDA, G. W., TARNOPOLSKY, M. A. & PHILLIPS, S. M. Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in young men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009, 107, 987–92. [Google Scholar]

- TIPTON, K. D. , ELLIOTT, T. A., CREE, M. G., WOLF, S. E., SANFORD, A. P. & WOLFE, R. R. Ingestion of casein and whey proteins result in muscle anabolism after resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004, 36, 2073–81. [Google Scholar]

- TULIPANO, G. , SIBILIA, V., CAROLI, A. M. & COCCHI, D. Whey proteins as source of dipeptidyl dipeptidase IV (dipeptidyl peptidase-4) inhibitors. Peptides 2011, 32, 835–8. [Google Scholar]

- VERHOEVEN, S. , VANSCHOONBEEK, K., VERDIJK, L. B., KOOPMAN, R., WODZIG, W. K., DENDALE, P. & VAN LOON, L. J. Long-term leucine supplementation does not increase muscle mass or strength in healthy elderly men. Am J Clin Nutr 2009, 89, 1468–75. [Google Scholar]

- WELINDER, C. & EKBLAD, L. Coomassie staining as loading control in Western blot analysis. J Proteome Res 2011, 10, 1416–9. [Google Scholar]

- WILKINSON, D. J. , BUKHARI, S. S. I., PHILLIPS, B. E., LIMB, M. C., CEGIELSKI, J., BROOK, M. S., RANKIN, D., MITCHELL, W. K., KOBAYASHI, H., WILLIAMS, J. P., LUND, J., GREENHAFF, P. L., SMITH, K. & ATHERTON, P. J. Effects of leucine-enriched essential amino acid and whey protein bolus dosing upon skeletal muscle protein synthesis at rest and after exercise in older women. Clin Nutr 2018, 37, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar]

- WILKINSON, D. J. , HOSSAIN, T., HILL, D. S., PHILLIPS, B. E., CROSSLAND, H., WILLIAMS, J., LOUGHNA, P., CHURCHWARD-VENNE, T. A., BREEN, L., PHILLIPS, S. M., ETHERIDGE, T., RATHMACHER, J. A., SMITH, K., SZEWCZYK, N. J. & ATHERTON, P. J. Effects of leucine and its metabolite beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate on human skeletal muscle protein metabolism. J Physiol 2013, 591, 2911–23. [Google Scholar]

- WITARD, O. C. , JACKMAN, S. R., BREEN, L., SMITH, K., SELBY, A. & TIPTON, K. D. Myofibrillar muscle protein synthesis rates subsequent to a meal in response to increasing doses of whey protein at rest and after resistance exercise. Am J Clin Nutr 2014, 99, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WOLFE, R. R. Update on protein intake: importance of milk proteins for health status of the elderly. Nutr Rev 2015, 73 Suppl 1, 41–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WOLFSON, R. L. , CHANTRANUPONG, L., SAXTON, R. A., SHEN, K., SCARIA, S. M., CANTOR, J. R. & SABATINI, D. M. Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science 2016, 351, 43–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- XU, Z. R. , TAN, Z. J., ZHANG, Q., GUI, Q. F. & YANG, Y. M. The effectiveness of leucine on muscle protein synthesis, lean body mass and leg lean mass accretion in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 2015, 113, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- YANG, Y. , BREEN, L., BURD, N. A., HECTOR, A. J., CHURCHWARD-VENNE, T. A., JOSSE, A. R., TARNOPOLSKY, M. A. & PHILLIPS, S. M. Resistance exercise enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis with graded intakes of whey protein in older men. Br J Nutr 2012, 108, 1780–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).