1. Introduction

The house fly

Musca domestica L. is one of the most widespread pests of humans and livestock worldwide. It breeds in decomposing manure and other organic substrates and thrives in animal production systems. House flies are notorious nuisance pests, reducing animal welfare and productivity through stress and irritation, and they are also recognized mechanical vectors of a wide range of pathogens affecting both animals and humans [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Their close association with livestock farming systems makes them particularly problematic in poultry, swine, dairy, and beef facilities [

5]. In the United States alone, the annual economic costs attributed to house flies in livestock operations have been estimated to exceed USD 1 billion, considering veterinary treatments, reduced production efficiency, increased use of insecticides, and complaints from neighboring communities [

5,

6]. Other synanthropic flies, such as the stable fly

Stomoxys calcitrans (L.), also contribute to economic losses in livestock [

7], but in most production systems the house fly is by far the dominant pest. Its rapid reproductive cycle, capacity to disperse, and role in pathogen transmission make it one of the most challenging insect pests to manage sustainably.

Chemical insecticides remain the most common approach to house fly control, but resistance to nearly all major insecticide classes is now widespread [

8,

9]. Beyond resistance, repeated insecticide use can disrupt ecological balance by reducing non-target beneficial arthropods, such as dung beetles, and poses risks to farm workers exposed during application [

10]. Moreover, large-scale evaluations by the French national health institute INSERM have documented associations between chronic pesticide exposure and adverse human health outcomes, including neurotoxicity, endocrine disruption, and increased cancer risk [

11,

12]. These drawbacks reinforce the urgent need for sustainable alternatives.

Biological control has long been considered a promising solution for pest management. Already in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the use of natural enemies was expanding rapidly in crop protection, with well-known successes such as

Phytoseiulus persimilis Athias-Henriot against spider mites [

13,

14,

15]. Applications in animal health are also well documented, including the management of filth flies [

7,

16], the poultry red mite

Dermanyssus gallinae, and even ectoparasites of companion animals such as the snake mite

Ophionyssus natricis, where

Cheyletus eruditus has proven effective [

17].

More recently, international institutions have highlighted the strategic importance of biocontrol. In November 2024, the International Biocontrol Manufacturers Association (IBMA) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) signed a Letter of Intent to accelerate the uptake of biological control tools worldwide and transition toward more sustainable agrifood systems, underscoring the growing recognition of biocontrol as a cornerstone of future pest management [

18].

In animal production systems, the USDA workshop on the Status of Biological Control of Filth Flies [

16] highlighted that significant reductions in house fly populations could be achieved when the right parasitoid species were used in combination with good manure management.

Since then, parasitoid wasps in the family Pteromalidae have become the most widely studied and applied natural enemies of house flies. Species such as

Spalangia cameroni Perkins and

Muscidifurax raptorellus Kogan & Legner attack the pupal stage of the fly and have demonstrated efficacy in poultry and cattle systems [

7,

19]. However, their performance is sometimes inconsistent, reflecting challenges of species selection, release timing, and matching parasitoid biology to fly development.

Predatory mites of the family Macrochelidae provide a complementary form of control by targeting earlier life stages of flies.

Macrocheles muscaedomesticae (Scopoli) is a cosmopolitan predator of fly eggs and first-instar larvae, commonly found in livestock manure [

20,

21]. By attacking flies in their immature stage, predatory mites can reduce the number of hosts available to parasitoids and exert early pressure on fly population growth. Recent field studies further support this integrated approach: González et al. [

22] demonstrated that combining parasitoids with the predatory mite

Macrocheles robustulus significantly reduced stable fly populations, highlighting the potential of predator–parasitoid combinations in filth fly management.

The idea of combining natural enemies to achieve stronger fly suppression has been suggested for decades. Ho [

23], in his work on the mass production of

M. muscaedomesticae, emphasized that predators and parasitoids could be complementary because they act on different developmental stages of the fly. Later reviews also pointed to this potential [18, 24, 25], but to date no published study has experimentally tested the combined release of predatory mites and parasitoids against the house fly.

The objective of this study was to evaluate, under controlled laboratory conditions highly favorable to fly development, the combined impact of predatory mites and parasitoids on house fly emergence. We hypothesized that dual releases of M. muscaedomesticae with S. cameroni and M. raptorellus would provide greater suppression of house fly populations than either natural enemy alone. This represents the first experimental test of the long-standing idea that predation and parasitism can be integrated to improve the biological control of house flies.

2. Materials and Methods

All experiments were conducted at the Entomology Laboratory of BESTICO France (Nantes, France) between January and September 2025.

Origin and Rearing of Arthropods

House fly (Musca domestica): A laboratory colony of M. domestica was maintained at 27.1 ± 1.0 °C, 65 ± 3.3% RH, under a 12:12 h (L:D) photoperiod. Adults were kept in rearing cages (BugDorm-2400 Insect Tent, 96 × 26 cm) and provided with water and a dry diet consisting of powdered milk and granulated sugar. Oviposition was stimulated using egg traps consisting of a black cloth impregnated with fish sauce (Nuoc Mam) and covered with a perforated black pot. Traps were left in the cages for 24 h, and collected eggs were transferred onto a house fly larval diet composed of 1 part ground soybean, 1 part sow feed, 1.8 parts wheat bran, and 2.7 parts water to complete the cycle. This routine is observed to maintain the colony at the lab.

Predatory mite (

Macrocheles muscaedomesticae): Individuals of

M. muscaedomesticae originated from a goat farm localized near the insectarium in Montbert, Nantes, France. Lab colonies were maintained with a method adapted from Ho [

23]. It consisted of using plastic containers (Sunware, 35 cm diameter × 12 cm height) to culture the mite. The plastic container was filled with wet vermiculite and mite were fed daily with a mixture of house fly eggs and larvae. The stock colony was reset every 2 weeks to maintain good quality and sanitation. Colonies were maintained at 26–28 °C, 70–90% RH, in darkness.

Parasitoids (Spalangia cameroni and Muscidifurax raptorellus): Adults of S. cameroni and M. raptorellus were obtained directly from the commercial product BIOWASP at Bestico, France consisting in infested pupae of these parasitoid species. For the experiment need, the infested pupae were left for emergence in the lab and adult parasitoids were fed with house fly pupae prior to being used in experiments. In average parasitoids used in the experiment were 2 to 3 days old. Random collection of adult wasps prior to experimentation was managed with a mouth vacuum.

Experimental Setup

Experiments were conducted in circular plastic boxes (Sunware, 35 cm diameter × 12 cm height) with six ventilation holes drilled on the cap (5 cm diameter) covered with a fine net (0.5 mm). This set up has been designed to allow air circulation in the box, avoid fungi development and prevent too fast desiccation of the house fly diet during experimentation.

All boxes receiving the four different experimental treatments were filled with 600 grams of the house fly larval diet described above as well as eventually 1000 house fly eggs within the method describe below: predatory mites, parasitoids or both. Each treatment was replicated 35 times. Boxes were then maintained in the insectary at 25 ± 1.0 °C, 65 ± 3.3% RH, and a 12:12 h (L:D) photoperiod throughout the experimental time of 15 days. Experiments began with the transfer of house fly eggs into the diet and ended 15 days after. In preliminary experiments we have shown that in such abiotic conditions house flies developed and hatched as adults in less than 15 days. At the end of the experiment the boxes were transferred to a freezer prior to counting adult house fly. Number of adult house flies between treatment was then compared.

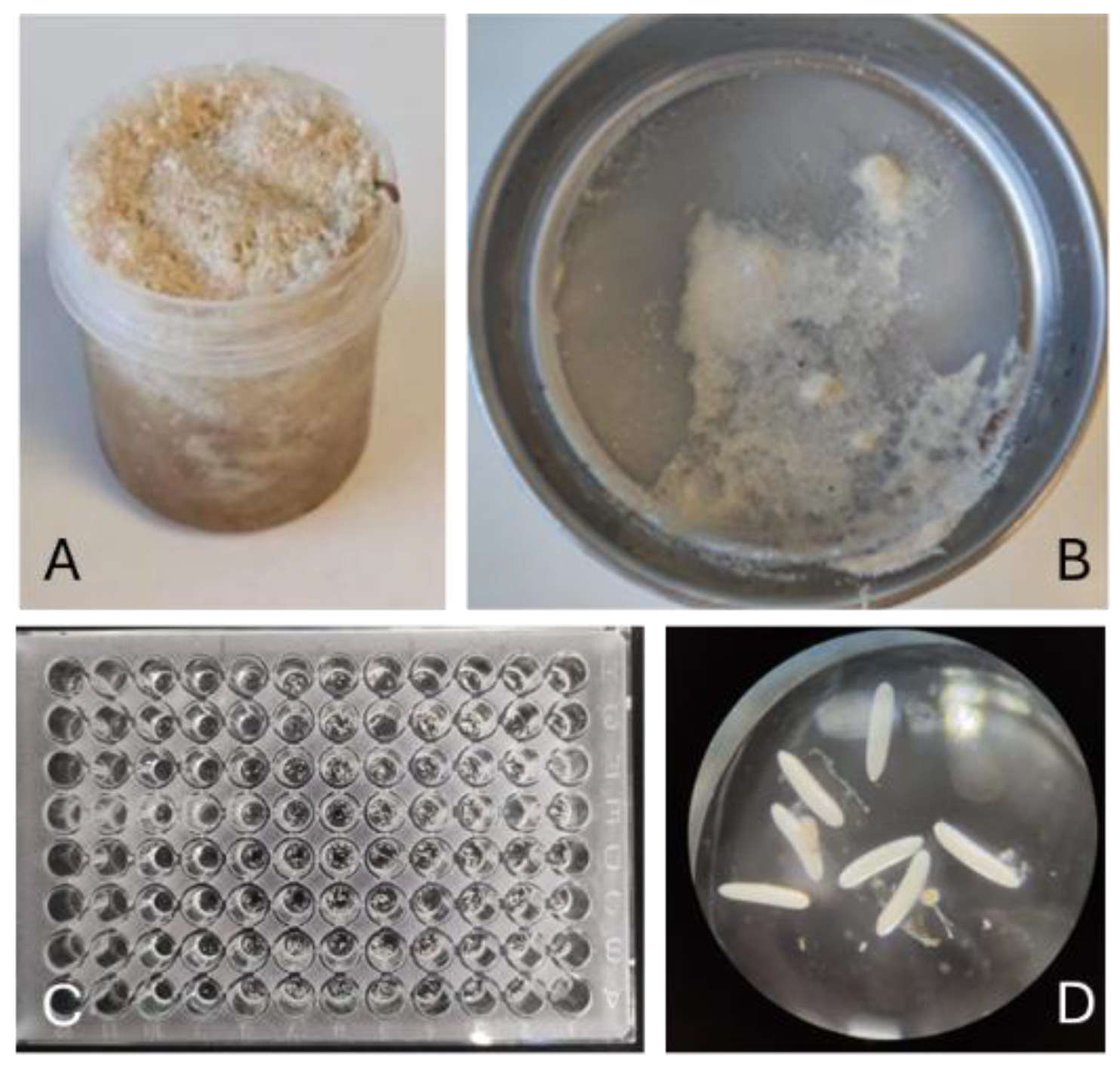

For each replication, 1,000

Musca domestica eggs (≈ 4 hours old) were collected from oviposition traps exposed in fly cages. Eggs were rinsed and sieved through a fine mesh (0.125 mm), suspended in water, and transferred into wells of a cell culture plate to facilitate counting under a stereomicroscope. Exactly 1,000 eggs were counted and transferred with pipet onto the larval substrate in each experimental box. See

Figure 1 Egg counting procedure.

Experimental Treatments

Four treatments were evaluated and replicated 35 times:

(C): Control – 1,000 fly eggs without natural enemies.

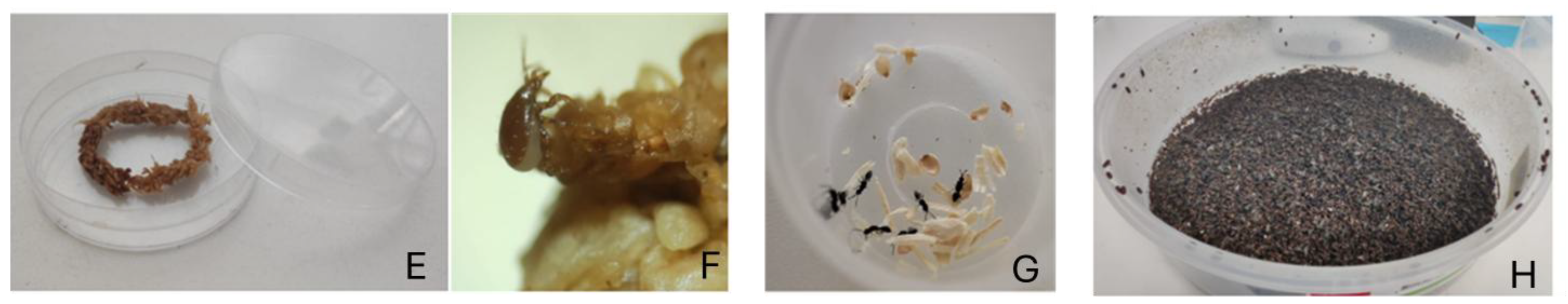

(P): Parasitoids – 1,000 fly eggs + 21 adults (

S. cameroni and

M. raptorellus) were introduced 4 days after house fly egg transfer. Two to four days old parasitoids were randomly collected (sex not distinguished), kept at 18 °C during 24hours in small containers (see C in

Figure 2) with water and honey, and released into experimental boxes.

(PM): Predatory mites – 1,000 fly eggs + 24 adult

M. muscaedomesticae were introduced at day 0. Mites were transferred 24 h prior to the experiment into 60 ml plastic vials (24 individuals per vial) and maintained at 18 °C without food until use (see A, B in

Figure 2).

(PMP): Predatory mites + parasitoids – 1,000 fly eggs + 24 adult M. muscaedomesticae introduced at day 0, and 21 parasitoids were introduced at day 4.

Adult emergence counts: Fifteen days after egg deposition, boxes were placed at –20 °C for 5 h to kill all insects. The number of adult flies emerging from each box was then counted under a binocular. See H in

Figure 2.

Statistical analysis: the abundance of emerged flies in each treatment was compared using a Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with Holm correction for multiple comparisons. No data transformation was applied. Analyses were performed in R v.4.2.2 (2022-10-31 ucrt), with significance set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

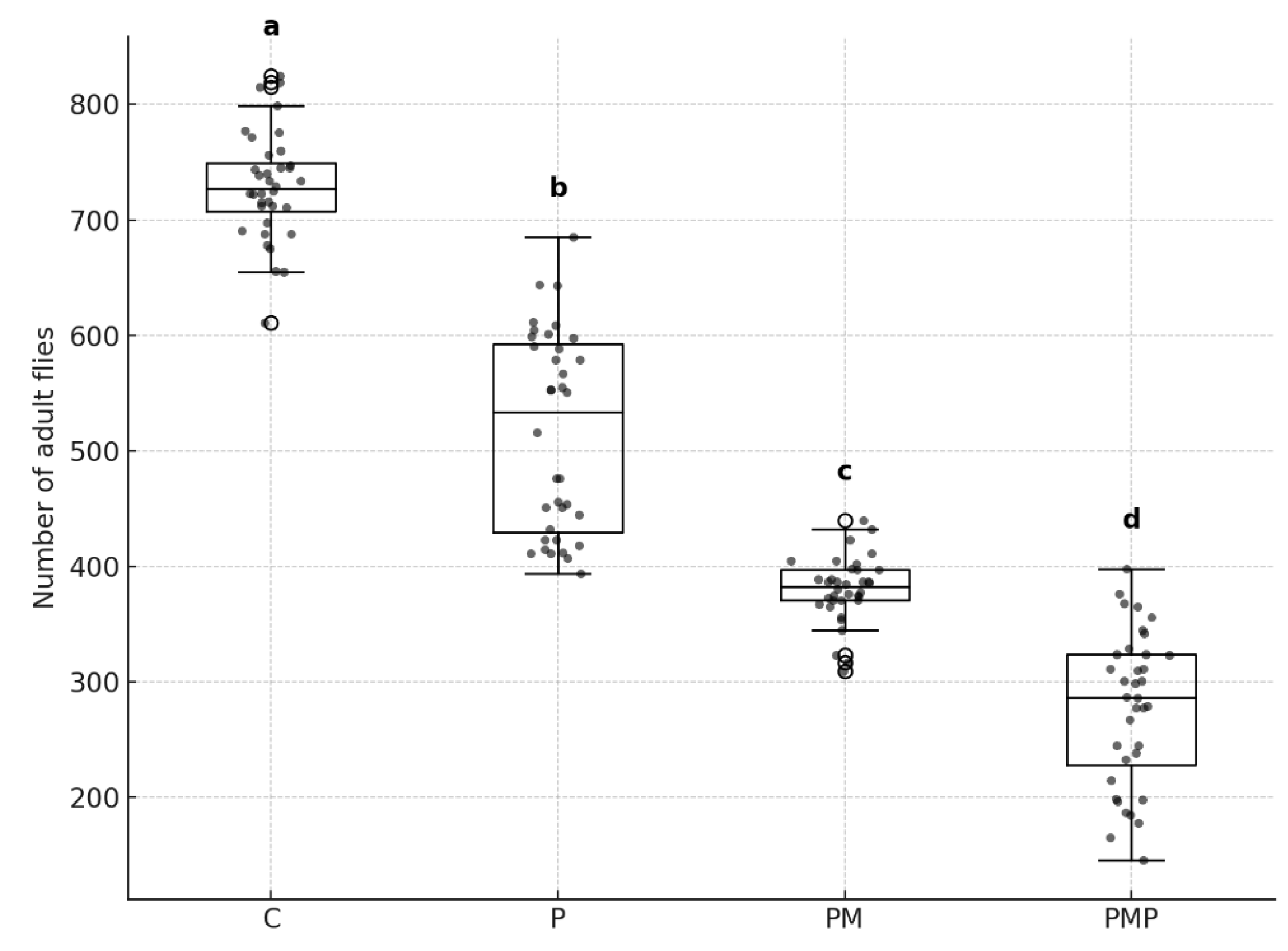

In experimental conditions, the control treatment showed very good house fly development, with an average of 720 adults emerging from 1,000 eggs (≈72% survival) (

Figure 3). These values are substantially higher than those typically observed under field or semi-field conditions. For instance, Azevedo et al. [

24] reported an average of only ≈250 adults per 1,000 eggs when larvae developed in hydrated manure placed on soil, whereas natural field populations are usually much lower due to environmental constraints. Similarly, Geden et al. [

5] noted that egg-to-adult survival under optimized laboratory rearing conditions often approaches 70–90%, considerably higher than in natural habitats. Such differences confirm that artificial diets and controlled conditions are more favorable to fly development than natural substrates.

A Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a highly significant treatment effect on the number of emerged flies (H = 128.8, p < 0.0001). Post hoc comparisons (Dunn’s test with Holm correction) indicated that all treatments differed significantly from one another (p < 0.001 in all cases). Among the natural enemy treatments, predatory mites alone resulted in stronger suppression of fly emergence than parasitoids alone, and the combined release of predatory mites and parasitoids produced the lowest number of adult flies, with averages of 380, 516, and 277 adults respectively (

Figure 3).

Fly suppression ranked as follows: predatory mite + parasitoids > predatory mites alone > parasitoids alone > control. These patterns indicate that the combined release of predatory mites and parasitoids resulted in the strongest reduction of house fly emergence, outperforming either beneficial species when used alone. Even under conditions highly favorable to house fly development, the dual-enemy treatment consistently achieved the lowest emergence rates.

4. Discussion

For practical reasons, we employed a standardized artificial substrate to rear flies rather than animal manure. We consider that this choice had limited impact on the relative parasitism and predation rates of the natural enemies tested, and therefore the results can reasonably be extrapolated to livestock facilities. Moreover, because our experimental conditions favored fly development, the relative efficacy of combined releases may be even greater under farm conditions, where environmental constraints naturally limit fly population growth.

In the present experiment, house fly emergence was considerably higher than typically observed under farm conditions. For example, Corrêa et al. (in [

20]) reported average densities of approximately 24

M. domestica pupae per m² in poultry and cattle facilities, whereas our artificial setup produced substantially higher numbers. As previously noted, colonies established directly from field material generally develop more slowly, produce heavier pupae, and show greater heterogeneity than long-maintained laboratory colonies [

5], which may partly explain the elevated fly productivity observed under our conditions. Together, these factors indicate that the experimental system used here represents a stringent test of the suppressive capacity of natural enemies.

Predatory mites are key natural regulators of house fly populations in animal facilities. Three families of mites—Macrochelidae, Uropodidae, and Parasitidae—are known to feed on fly eggs and larvae [

26,

27]. Among them,

Macrocheles muscaedomesticae is the most widespread and specialized predator, capable of consuming up to 20 fly eggs per day [

21]. Reductions in fly numbers in cattle and poultry manure have been documented under semi-field conditions with this species [

28], and literature reviews have emphasized its importance for natural suppression of

M. domestica [

29,

30]. Despite this,

M. muscaedomesticae has not been mass-produced or marketed as a biocontrol agent. Instead, the closely related but more generalist species,

M. robustulus is the only macrochelid mite currently available commercially, primarily for use in horticultural systems. Its biology, phoretic dispersal, and close association with fly habitats nevertheless make

M. muscaedomesticae a particularly promising candidate for future development [

23].

Our results confirm that the combination of predatory mites and parasitoid wasps provides stronger suppression of house flies than either group alone. This outcome likely reflects both stage specificity and differences in developmental cycles: mites target eggs and early larvae with a generation time of approximately 4 days, while pupal parasitoids such as Spalangia cameroni and Muscidifurax raptorellus attack pupae and require 14–28 days for development.

When released together, these complementary agents can provide immediate as well as sustained control, provided releases are repeated regularly.

The choice of predator species is also critical. While González et al. [

22] demonstrated that the combination of parasitoids with

M. robustulus reduced

Stomoxys calcitrans populations under field conditions, this mite is considered a generalist. Bamière et al. [

31] recently confirmed its broader feeding preferences, including significant consumption of nematodes. In contrast,

M. muscaedomesticae shows a marked association with filth flies, with both stronger phoretic behavior and greater preference for fly eggs, making it a more specialized and potentially more effective control agent for

M. domestica.

Future studies should extend these findings to other species of synanthropic flies, such as the stable fly

S. calcitrans, and should test the combined release of natural enemies in commercial livestock facilities, following the approach of Skovgård [

7]. Field trials would provide essential validation of the laboratory results and help establish practical protocols for augmentative release.

Finally, field observations by the authors indicate that M. muscaedomesticae readily establishes in poultry and dairy farms following augmentative releases, and individuals can be easily recovered from manure samples. This persistence suggests that the predator not only survives but may contribute to long-term suppression of fly populations under farm conditions. Together with pupal parasitoids, it represents a promising component of integrated pest management programs for house flies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and G.D.; methodology, D.M., G.D. and N.M.; validation, D.M., G.D. and N.M.; formal analysis, D.M., G.D. and N.M.; investigation, N.M. and D.M.; resources, D.M.; data curation D.M., G.D. and N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.; writing—review and editing, D.M. and G.D.; project administration, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article. Additional information can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chavasse, D.C.; Shier, R.P.; Murphy, O.A.; Huttly, S.R.A.; Cousens, S.N. Impact of fly control on childhood diarrhea in The Gambia: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. The Lancet 1999, 353, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasa, M.; Makino, S.; Asakura, H.; Kobori, H.; Morimoto, Y. Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from houseflies captured in a cattle farm and their role in the contamination of cattle. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1999, 65, 3677–3682. [Google Scholar]

- Pospischil, R.; Hanke, S. Fly control in pig stables – New strategies. In Proceedings of the 13th Congress of the International Pig Veterinary Society, Bangkok, Thailand, 26–30 June 1994; p. 452. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G.D.; Skoda, S.R. Rural flies and their control. In Pest Management in the USA; Thomas, G.D. & Skoda, S.R., Ed.; Entomological Society of America: Lanham, MD, 1993; pp. 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Geden, C.J.; Nayduch, D.; Scott, J.G.; Burgess, E.R.; Gerry, A.C.; Kaufman, P.E.; Thomson, J.; Pickens, V.; Machtinger, E.T. House fly (Musca domestica L.): Biology, pest status, current management prospects, and research needs. Journal of Integrated Pest Management 2021, 39, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, G.L.; Sloderbeck, P.E.; Nechols, J.R. Biological Fly Control for Kansas Feedlots. MF-2223, 1998, Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service, Manhattan, Kansas.

- Skovgård, H. Sustained releases of the pupal parasitoid Spalangia cameroni (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) for control of house flies, Musca domestica, and stable flies, Stomoxys calcitrans (Diptera: Muscidae), on dairy farms in Denmark. Biological Control 2004, 30, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiding, J. Review of the resistance status of house flies worldwide. Pesticide Science 1999, 55, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.A.; Petersen, J.J.; Morgan, P.B.; Wamsley, J.K. Resistance of house flies to insecticides in Nebraska. Journal of Economic Entomology 1987, 80, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Agrican. Programme de surveillance prospective, AGRICAN. Available at: https://www.cancer-environnement.fr/ (accessed 15 Sept 2025), 2017.

- INSERM Pesticides : Effets sur la santé. Expertise collective. Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Paris. 2013.

- INSERM Pesticides et santé : Nouvelles données. Expertise collective. Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Paris. 2021.

- van Lenteren, J.C. The state of commercial augmentative biological control: plenty of natural enemies, but a frustrating lack of uptake. BioControl 2012, 57, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolckmans, K.; van Houten, Y. Mite management in greenhouse crops. IOBC/WPRS Bulletin 2006, 29, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- IBMA IBMA Annual Report 2015. International Biocontrol Manufacturers’ Association. Available at: https://www.ibma-global.org/ (accessed 15 Sept 2025).

- Patterson, R.S. (ed.). Status of Biological Control of Filth Flies: Proceedings of a Workshop, 4–5 February 1981, University of Florida, Gainesville. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Science and Education Administration, Southern Region, New Orleans, Louisiana. 1981.

- Schilliger, L.H.; Morel, D.; Bonwitt, J.H.; Marquis, O. Cheyletus eruditus (TAURRUSt): an effective candidate for the biological control of the snake mite (Ophionyssus natricis). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 2013, 44, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBMA; FAO IBMA and FAO sign Letter of Intent. International Biocontrol Manufacturers Association. Available at: https://ibma-global.org/latest-news/ibma-and-fao-sign-letter-of-intent (accessed 15 Sept 2025). 2024.

- Taylor, D.B. Area-wide management of stable flies. In (eds), Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management: Development and Field Application, 2nd ed.; Hendrichs, J., Pereira, R., Vreysen, M.J.B., Eds.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, 2021; pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, L.H.; Ferreira, M.P.; Castilho, R.C.; Cançado, P.H.D.; de Moraes, G.J. Potential of Macrocheles species (Acari: Mesostigmata: Macrochelidae) as control agents of harmful flies (Diptera) and biology of Macrocheles embersoni Azevedo, Castilho and Berto on Stomoxys calcitrans (L.) and Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae). Biological Control 2018, 123, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geden, C.J.; Axtell, R.C. Predation by Carcinops pumilio (Coleoptera: Histeridae) and Macrocheles muscaedomesticae (Acarina: Macrochelidae) on the house fly (Musca domestica): Functional response, effects of temperature, and availability of alternative prey. Environmental Entomology 1988, 17, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.A.; Duvallet, G.; Morel, D.; de Blas, I.; Barrio, E.; Ruiz-Arrondo, I. An integrated pest management strategy approach for the management of the stable fly Stomoxys calcitrans (Diptera: Muscidae). Insects 2024, 15, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.-C. Mass production of the predaceous mite, Macrocheles muscaedomesticae (Scopoli) (Acarina: Macrochelidae), and its potential use as a biological control agent of house fly, Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae). PhD dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, L.H.; Borges, V.; Mesquita Filho, W.; Castilho, R.C.; de Moraes, G.J. Semi-field evaluation of the predation of Macrocheles embersoni and Macrocheles muscaedomesticae (Acari: Mesostigmata: Macrochelidae) on the house fly and the stable fly (Diptera: Muscidae). Pest Management Science 2022, 78, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Xu, J.; Qu, X.; Zhou, X. Potential of predatory mites in biological control of filth flies: a review. Insects 2018, 9, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, R.C. The ecology and role of predaceous mites in poultry manure in North Carolina. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 1961, 54, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, R.C. Ecology of predaceous mites (Acarina: Mesostigmata) in poultry manure in North Carolina. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 1963, 56, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, R.C. Fly management in poultry production: cultural, biological, and chemical. Poultry Science 1986, 65, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, R.C. The role of mesostigmatid mites in the biological control of filth flies associated with poultry manure. Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress of Acarology, 1969, pp. 401–416.

- Geden, C.J. Entomopathogenic nematodes for control of house flies (Musca domestica) and stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans) (Diptera: Muscidae): a review of laboratory and field studies. Biocontrol Science and Technology 1990, 1, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamière, A.; Petermann, J.; Morel, D.; Jacquiet, P.; Grisez, C. The mite Macrocheles robustulus (Mesostigmata: Macrochelidae): a new promising natural enemy of Haemonchus contortus (Strongylida: Trichostrongylidae). Parasites & Vectors 2025, 18, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).