Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

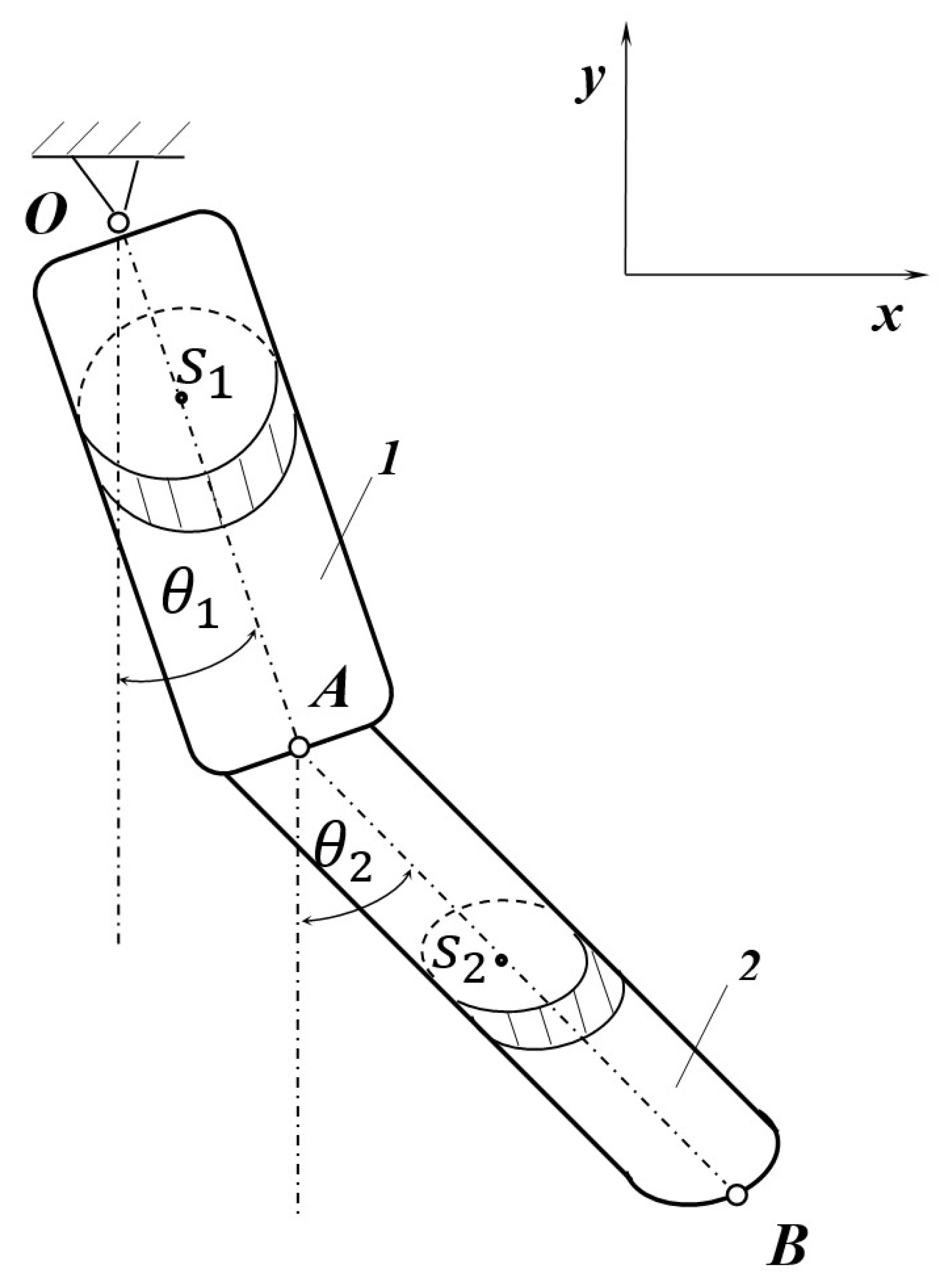

2. The Model

3. The Equations of Motion

4. Biomechanical Data

5. Numerical Results

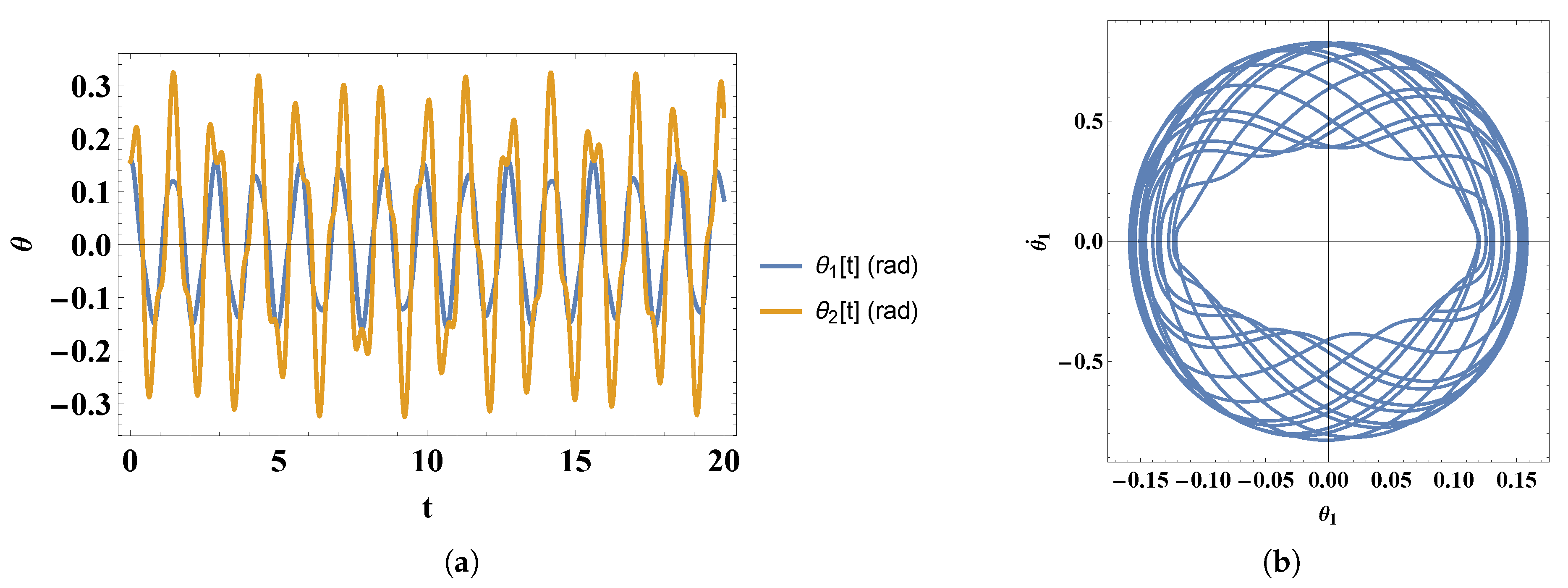

- 1)

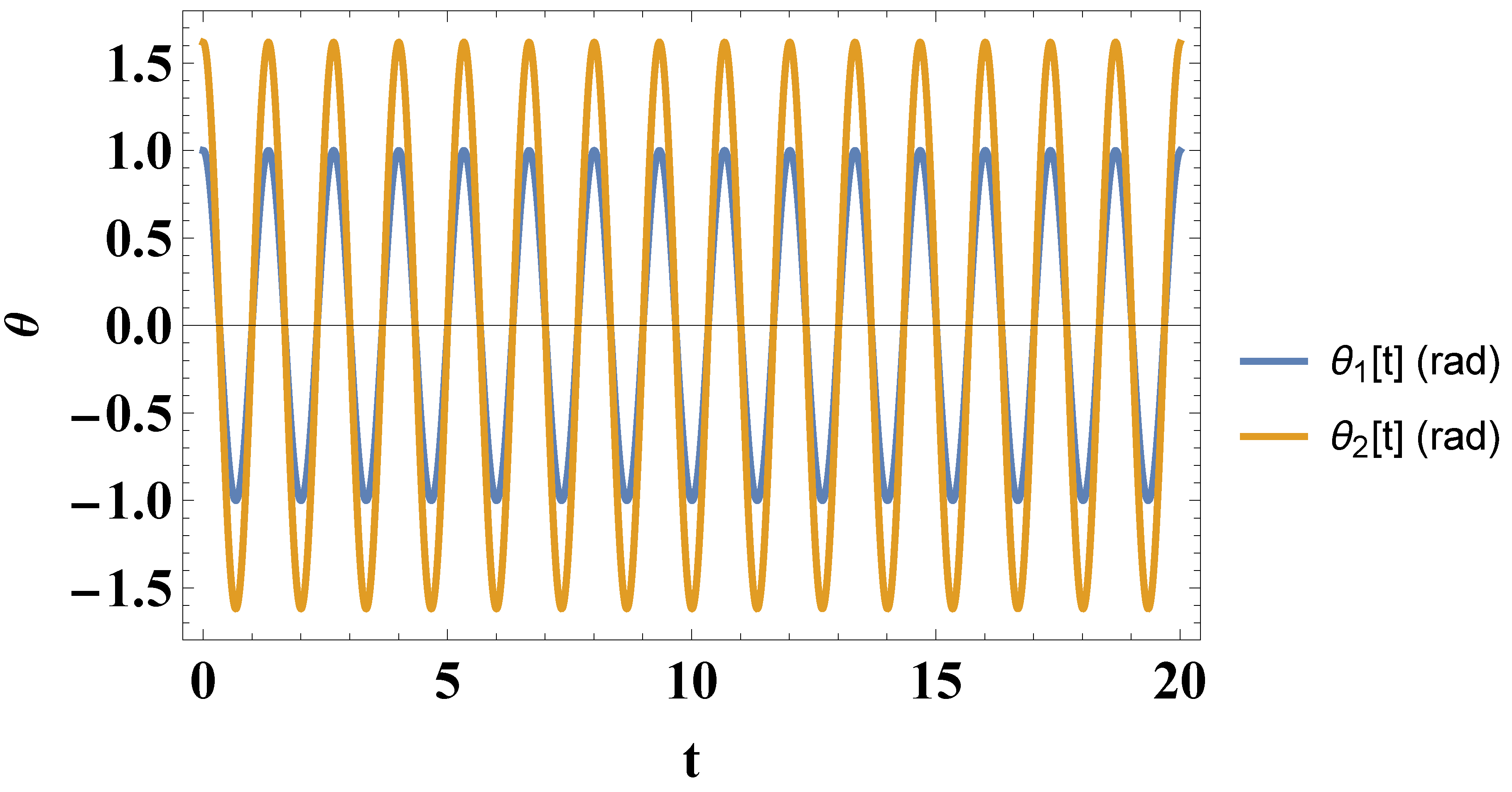

- For small initial angles and speeds we obtain the following solutions for and :

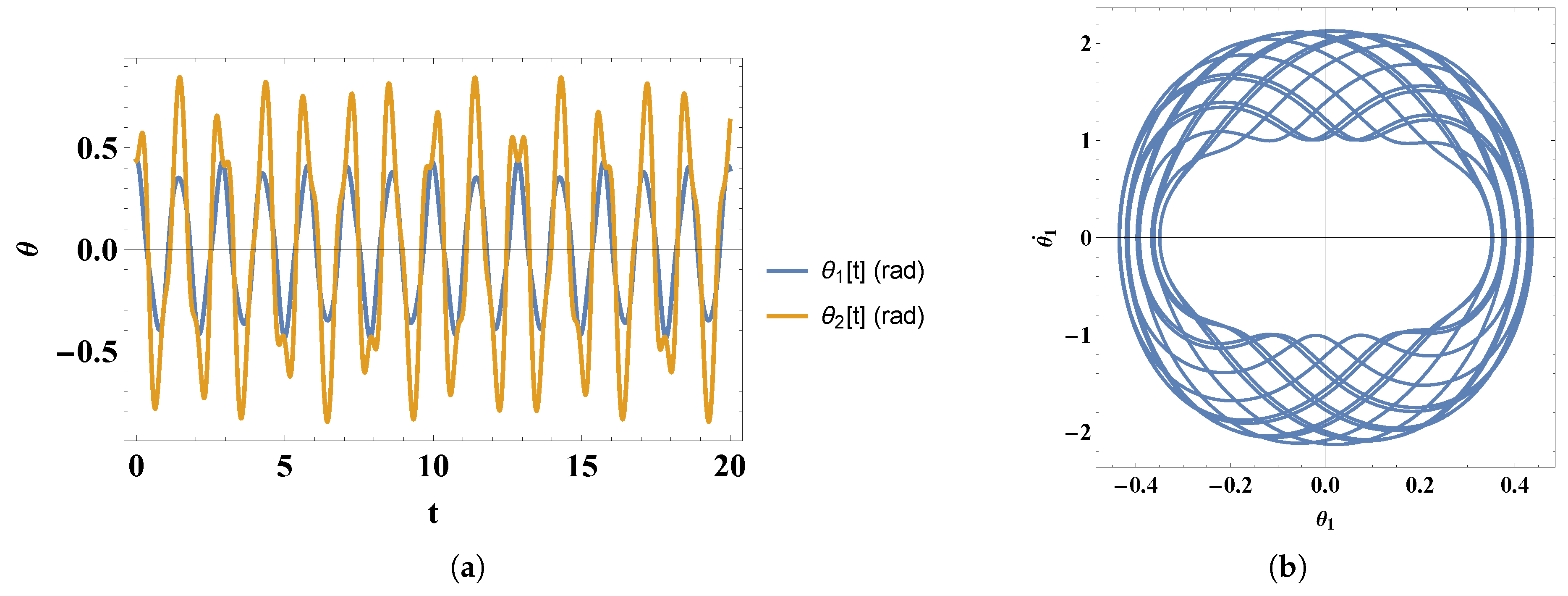

- 2)

- For intermediate initial angles and speeds we obtain the following solutions for and :

6. Small Angles Approximation

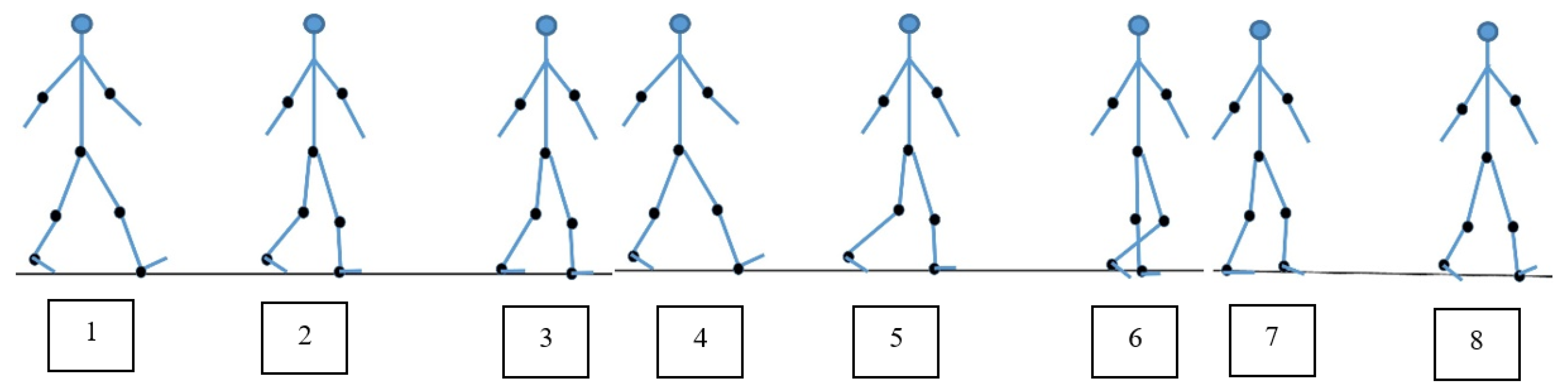

7. Comparison of Our Model Results to Real Walking

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ott, E. Chaos in dynamical systems; Cambridge university press, 2002.

- Rose, J.; Gamble, J.G. Human walking. Philadelphia 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Hu, B. Bifurcations and transitions to chaos in an inverted pendulum. Phys. Rev. E 1998, 58, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSerio, R. Chaotic pendulum: The complete attractor. Am. J. of Phys. 2003, 71, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayfeh, A.H.; Mook, D.T. Nonlinear oscillations; John Wiley & Sons, 2024.

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ardema, M.D. Analytical dynamics: theory and applications; Springer Science & Business Media, 2005.

- Guckenheimer, J.; Holmes, P. Nonlinear oscillations, dynamical systems, and bifurcations of vector fields; Vol. 42, Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- Baker, G.L.; Blackburn, J.A. The pendulum: a case study in physics; OUP Oxford, 2008.

- Dutra, M.S.; de Pina Filho, A.C.; Romano, V.F. Modeling of a bipedal locomotor using coupled nonlinear oscillators of Van der Pol. Biological Cybernetics 2003, 88, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, S.G.; Vassilev, V.M.; Zaharieva, D.T. Analysis of swing oscillatory motion. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Bulgarian Section of SIAM. Springer; 2018; pp. 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, S.; Zaharieva, D. Dynamical behaviour of a compound elastic pendulum. In Proceedings of the MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, Vol. 145; 2018; p. 01003. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, V.I. Geometrical methods in the theory of ordinary differential equations; Vol. 250, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Baines, P.G. Lorenz, EN 1963: Deterministic nonperiodic flow. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 20, 130–41.1. Progress in Physical Geography 2008, 32, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic nonperiodic flow 1. In Universality in Chaos, 2nd edition; Routledge, 2017; pp. 367–378.

- Penner, A.R. The physics of golf. Reports on progress in physics 2002, 66, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinbrot, T.; Grebogi, C.; Wisdom, J.; Yorke, J.A. Chaos in a double pendulum. American Journal of Physics 1992, 60, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levien, R.; Tan, S. Double pendulum: An experiment in chaos. American Journal of Physics 1993, 61, 1038–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komuro, M. Double pendulum and chaos. Journal of the Robotics Society of Japan 1997, 15, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, G.S.; Toshev, Y.E. Estimation of male and female body segment parameters of the Bulgarian population using a 16-segmental mathematical model. Journal of biomechanics 2007, 40, 3700–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolova, G.; Kotev, V.; Dantchev, D.; Tsveov, M. Study of mass-inertial characteristics of female human body by walking. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing LLC, Vol. 2239; 2020; p. 020032. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova, G.; Dantchev, D.; Tsveov, M. Age changes of mass-inertial parameters of the female body by walking. Vibroengineering Procedia 2023, 50, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, G.F.; Smith, P.A.; et al. Human motion analysis: current applications and future directions. (No Title) 1996.

- Braune, W.; Fischer, O. The human gait; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Winter, D.A. Biomechanics and motor control of human movement; John wiley & sons, 2009.

- Asbeck, A.T.; De Rossi, S.M.; Galiana, I.; Ding, Y.; Walsh, C.J. Stronger, smarter, softer: next-generation wearable robots. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 2014, 21, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, I.P. Physics of the human body; Springer, 2007.

- Herman, I.P. Physics of the human body; Springer, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Majed, L.; Ibrahim, R.; Lock, M.J.; Jabbour, G. Walking around the preferred speed: examination of metabolic, perceptual, spatiotemporal and stability parameters. Frontiers in physiology 2024, 15, 1357172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saibene, F.; Minetti, A.E. Biomechanical and physiological aspects of legged locomotion in humans. European journal of applied physiology 2003, 88, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J. Chaos from simplicity: an introduction to the double pendulum 2008.

- Buczek, F.L.; Cooney, K.M.; Walker, M.R.; Rainbow, M.J.; Concha, M.C.; Sanders, J.O. Performance of an inverted pendulum model directly applied to normal human gait. Clinical Biomechanics 2006, 21, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colobert, B.; Crétual, A.; Allard, P.; Delamarche, P. Force-plate based computation of ankle and hip strategies from double-inverted pendulum model. Clinical biomechanics 2006, 21, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, S.; Owen, J.S.; Hussein, M.F. Experimental identification of the lateral human–structure interaction mechanism and assessment of the inverted-pendulum biomechanical model. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2014, 333, 5865–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, A.D. The six determinants of gait and the inverted pendulum analogy: A dynamic walking perspective. Human movement science 2007, 26, 617–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, D. Introduction to classical mechanics: with problems and solutions; Cambridge University Press, 2008.

| Segment | Length ] | Mass [kg] | Centre of mass from the proximal end of the segment [ ] | Moments of inertia [] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thigh | 51.0 | 11.0 | 21.1 |

= 6321.42 =1564.0 =1564.0 = 307.7 |

| Shank | 37.2 | 3.3 | 16.6 |

= 1124.3 = 231.9 =231.9 = 34.0 |

| Gait phases of the human gait cycle | Initial contact | Loading response | Mid stance | Terminal stance | Pre Swing | Initial Swing | Mid Swing | Terminal Swing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip | ||||||||

| Knee | ||||||||

| Ankle joint |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).