1. Introduction

Polycythemia vera (PV), a chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN), is characterized by the

JAK2 gene mutation, leading to abnormal thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, splenomegaly, and erythrocytosis [

1,

2]. The annual incidence of PV is estimated at 0.84 per 100,000 globally and 0.4–2.8 per 100,000 in the European Union [

3,

4]. The median age of patients at PV diagnosis is reportedly 61 years, including 10% of patients aged <40 years, with an equal male-to-female ratio [

5]. Patients may present with erythromelalgia, pruritus, abdominal discomfort, or transient visual disturbances. The median survival for patients with PV is approximately 15 years, with younger patients potentially experiencing survival beyond 35 years [

5]. Notably, patients managed at a specialist center have median overall survival of 27 years, more than double that of general PV population (13 years) [

6]. However, the natural history of these patients may be interrupted due to an increased risk of various complications. The 20-year risk of progression among patients with PV is 26% for thrombotic events, 16% for fibrotic events, and 4% for leukemic events [

5]. These medical complications adversely affect patients’ quality of life (QoL). Impairment in QoL among patients with PV is reported to be most pronounced among patients with newly diagnosed MPNs [

7]. Reducing PV-related symptoms and decreasing the risk of complications, mainly thrombosis, are the primary treatment goals in the context of PV [

8]. All patients need phlebotomy (target hematocrit <45%) and once- or twice-daily aspirin (in the absence of contraindications). High-risk patients (aged >60 years or with history of thrombosis) are treated with cytoreductive therapy, including hydroxyurea (first-line drug of choice) and pegylated interferon-α, followed by busulfan and ruxolitinib as second-line treatments. Systemic anticoagulation is suggested for patients with a history of venous thrombosis [

5].

PV has been designated a rare hematologic disease with a significant patient burden [

9]. Patient empowerment, and therefore the inclusion of the patient voice, is becoming more and more valued in the context of managing and researching rare diseases [

10,

11]. Patient perspectives are important in defining treatment benefits and assessing clinically meaningful changes [

12]. Many patients with rare diseases are often themselves experts about their condition, and thus, uniquely positioned to contribute to rare disease management and the designing/execution of rare disease research [

13,

14]. The patient voice can also contribute to developing a patient journey map (PJM), which captures evidence of patients’ emotional, psychological, and physical interactions with the entire care system. This helps identify patient pain points and opportunities for improvement in patient-centered care [

15]. The patient voice in PV remains largely unknown despite the value of patient perspectives. The current study aimed to fill this gap in the literature on PV by understanding the patient journey from the clinical, physical, professional, emotional, and practical perspectives in Portugal. The study also assessed disease awareness among patients and identified unmet needs. Insights from patient interactions with the PV care system may provide opportunities for improvement, such as enhancing patients’ QoL and providing better patient care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This study was conducted considering a mixed methods approach with distinct phases, in sequence: a qualitative phase followed by a quantitative phase. The qualitative phase involved in-depth interviews (n = 5) and a focus group discussion (n = 3) with patients with PV through collaboration with the Portuguese Association Against Leukemia (APCL), allowing for open questions to be posed and explored during the interviews and focus group. The mixed methods approach enables the quantification of outcomes through the quantitative component, while concurrently facilitating an in-depth exploration of underlying mechanisms and contextual factors via the qualitative component. Information for the qualitative phase was collected from 27 July–3 August 2023. The quantitative phase comprised computer-assisted web interviews (CAWIs), during which patients completed questionnaires. The quantitative phase planned to involve 30 patients with PV, but the data of 20 patients were collected between January and September 2024. Eligible patients for both phases were those aged ≥18 years, living in Portugal, which had been diagnosed with PV, and were undergoing PV treatment. There was no overlap of patients between phases.

2.2. Interview Discussion Script and Questionnaire

For the qualitative phase, following a thorough literature review, a discussion script was developed by IQVIA, an independent specialized agency, and validated by Novartis. The discussion scripts were designed to be completed by the patients within 120 minutes for the focus group and 60 minutes for the in-depth interview (Supplementary material). No identifiable patient data were collected, thereby ensuring confidentiality.

The questionnaire used for the quantitative phase had a total of 27 questions across three sections: the patient journey with PV, impact of the disease on patients’ QoL, and knowledge and sources of information about the disease. The questionnaire was designed to be completed by the patients in approximately 10 minutes (Supplementary material).

2.3. Study Measures

The primary objective of the study was to understand patient perspectives on living with PV.

The qualitative phase was mainly focused on creating a PJM that mapped the patients’ trajectory from symptom onset through diagnosis and treatment while also understanding the patients’ knowledge and feelings throughout. The quantitative phase was majorly focused on identifying the impact of PV on the patients’ lives, patient awareness about PV, and unmet needs. The patient journey from symptoms through follow-up included symptoms leading to the first consultation, first symptoms and time since diagnosis, interval between the first symptoms and diagnosis, medical follow-up by specialty, frequency of doctor visits, treatment options, patient satisfaction with the current treatment, and frequency of doctor visits among those undergoing phlebotomy. Treatment satisfaction and the impact of PV on patients’ lives were rated on a scale from 1 (not satisfied/very small impact) to 10 (totally satisfied/very high impact), and the scores were averaged over the available responses without imputing missing values.

The impact of PV on the patients’ lives was measured from the professional/social, emotional, and personal/physical perspectives. The physical perspective included patient experiences associated with the signs and symptoms of the disease and their impact on day-to-day tasks, habits, and routines. Emotional perspectives included the impact of the disease on feelings and emotions throughout the patient journey. The social perspective included the impact on their social interactions. The professional perspective included the impact on professional life, viz. changes in employment situation or the functions the patients performed.

Patient knowledge about PV included knowledge at diagnosis and at the time of the study, information sources at the time of diagnosis, discussion about therapeutic options with hematologists, information-seeking behavior, timing of information need (at diagnosis, beginning of treatment or follow-up), awareness of patient support groups, and awareness of APCL.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Qualitative interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interview transcripts were directly content analyzed. Extracted data were subjected to multiple validation steps to confirm accuracy, completeness, robustness, and reliability. For the quantitative data, the responses collected in the online questionnaires were collated by the research team at IQVIA using the Qualtrics XM online survey software (Qualtrics, UT, USA). Data were exported in Microsoft Excel, and the descriptive analysis was performed using SPSS software. Results from both phases were analyzed separately, but finally interpreted together.

3. Results

Data from five patients who participated in in-depth interviews and three patients who participated in the focus group discussion were obtained to create a PJM. The data of 20 patients who participated in the CAWI were analyzed during the quantitative phase; these patients had an equal gender distribution (male: 10 [50%]; female: 10 [50%]) and were mostly from Lisbon (n=9, 45%). The majority were aged ≥56 years (n=15, 75%) and predominantly had a higher level of education (n=9, 45%), with most being retired (n=13, 65%).

3.1. PJM: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Follow-Up

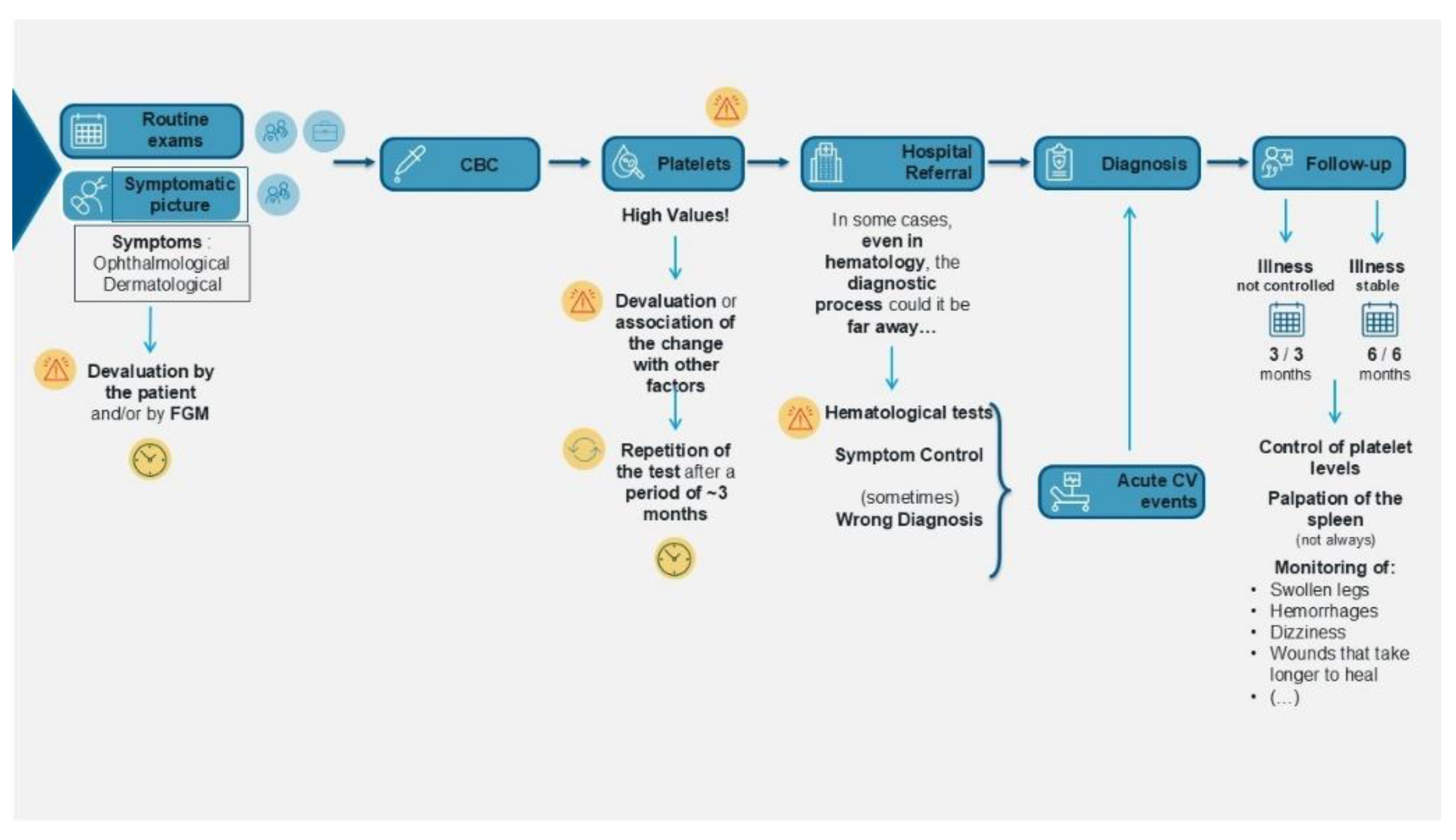

The PJM provided a chronological overview of the patients’ pre-diagnosis signs and symptoms, factors leading to their initial visit decision, the diagnostic process, treatment, and follow-up (

Figure 1).

Patient quotes collated during PJM creation are shown in Supplementary

Table 1.

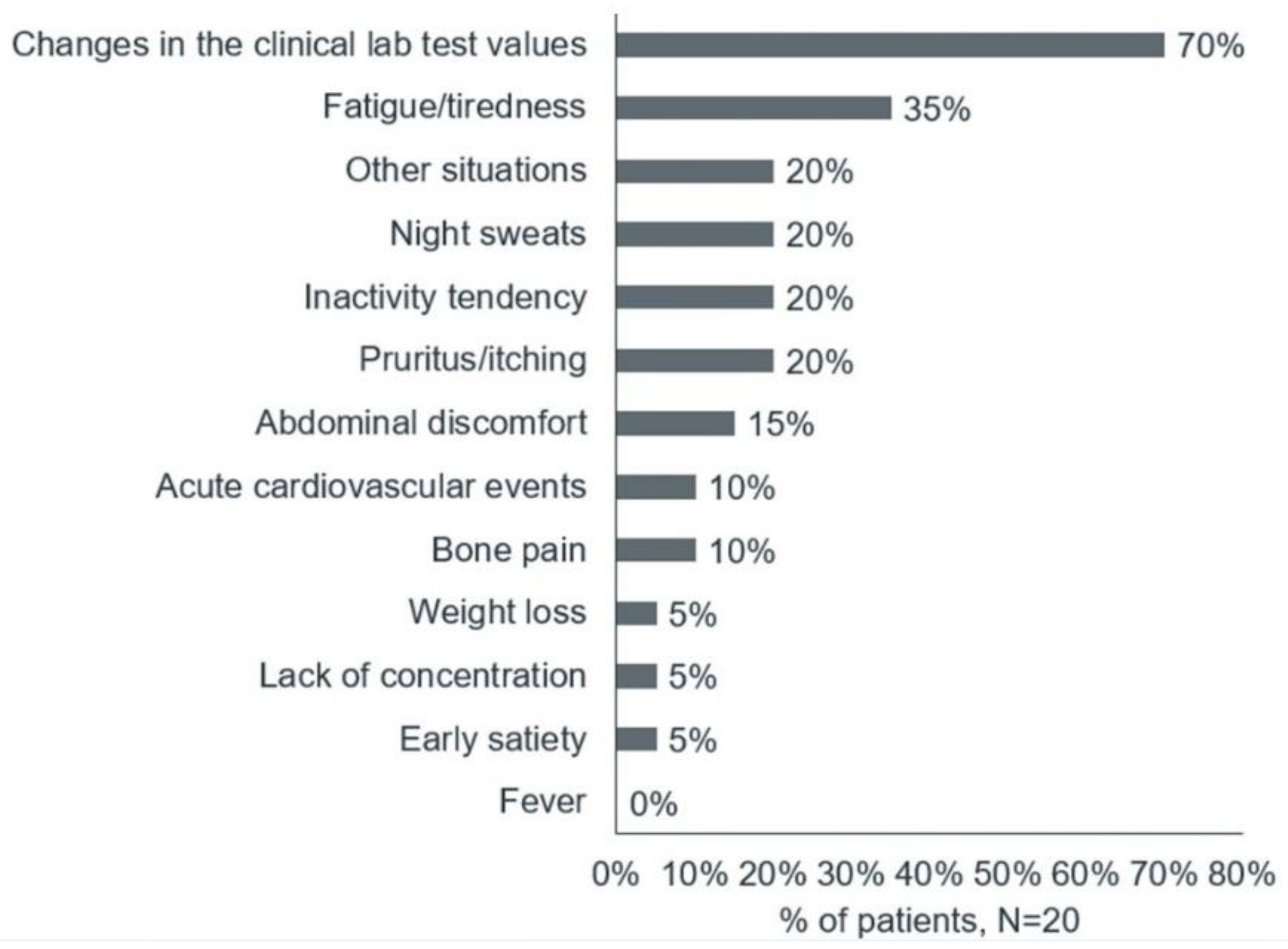

The main reasons for the first medical consultations were changes in clinical lab test values, followed by fatigue/tiredness, night sweats, itching, and abdominal discomfort (

Figure 2).

Because of these nonspecific symptoms, patients with PV who participated in the survey often mistakenly attributed their symptoms to other factors. Upon receiving their diagnosis, the patients expressed fear and concern about the future. The patients suggested that nonspecific symptoms and a lack of adequate knowledge among health care providers led to delayed diagnoses, with the diagnosis sometimes occurring only after an acute cardiovascular event. Reflecting qualitative patient experience, quantitative phase results showed that 12 (60%) patients were diagnosed within 5 months of the first symptoms, another 2 (10%) received diagnosis between 6 and 11 months, 3 (15%) between 1 and 2 years, and the remaining 3 (15%) patients were diagnosed between 3 and 4 years.

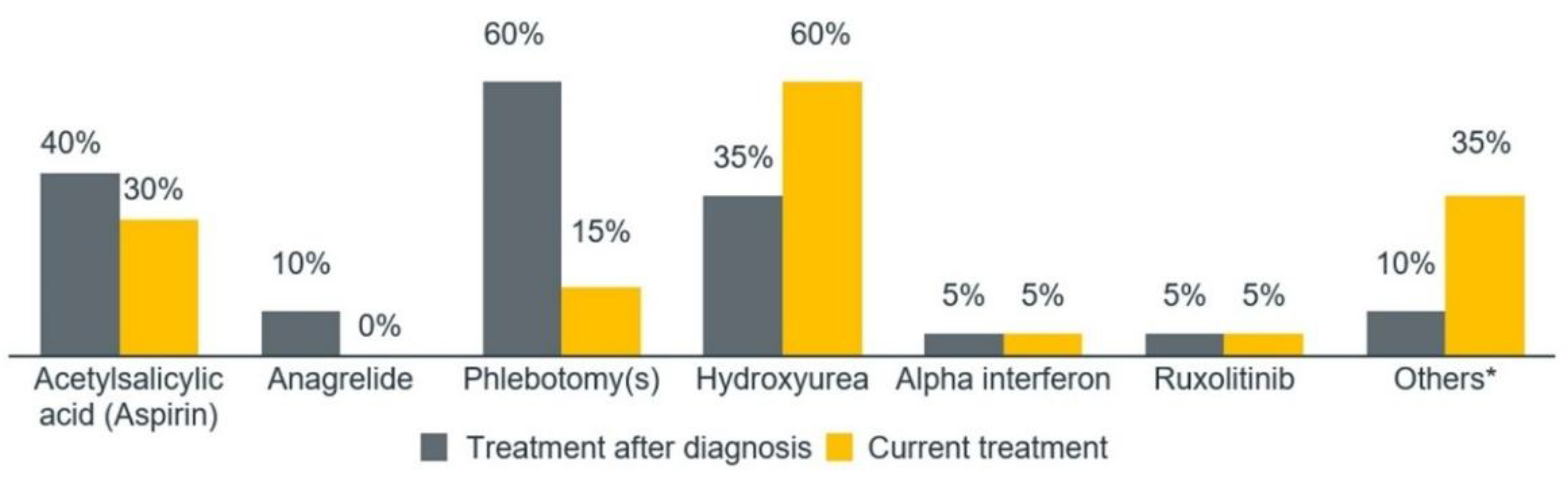

Due to the late diagnosis, the patients felt that they were not treated adequately, as the delay in referral from general practitioners and internal medicine specialists to hematologists impacted their care. The patients stated that PV treatment addresses only symptoms, not the disease itself, and they did not understand what was happening to them. The patients reported experiencing pain during phlebotomies, particularly when multiple phlebotomies were required for reports. Most patients stated that it was not easy to adapt to hydroxyurea; some reported side effects such as delay in healing of varicose ulcers, constipation, diarrhea, indisposition, and alopecia. This patient experience is crucial, as the quantitative phase showed that the most common treatment after diagnosis was phlebotomy (n=12, 60%), while the most common treatment at the time of the study was hydroxyurea (n=12, 60%) (

Figure 3).

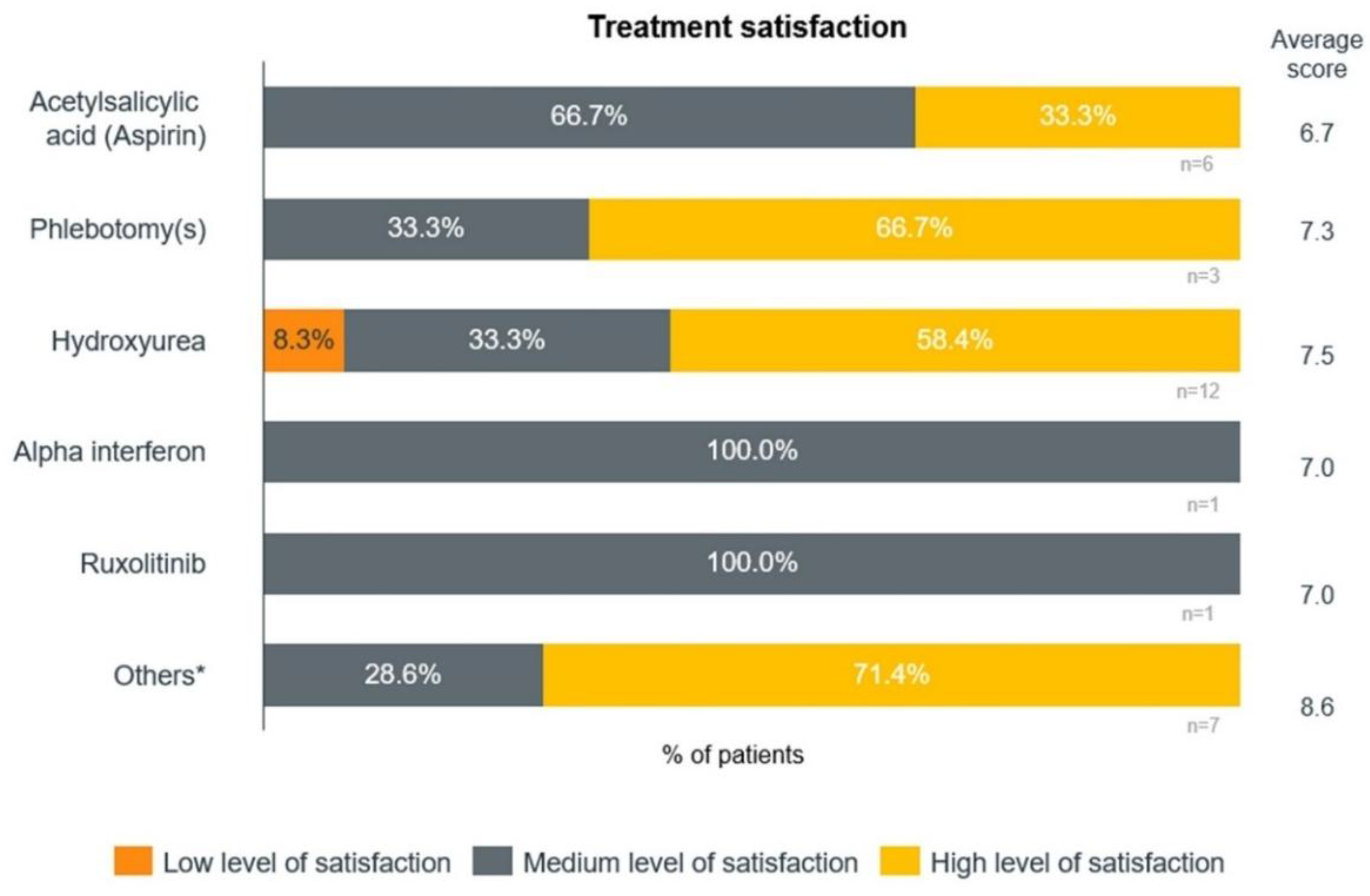

The patients also referenced other treatments, such as anagrelide, aspirin, intravenous iron, and warfarin. The average level of overall satisfaction was 7.6 out of 10. Among different treatments, the highest satisfaction levels were reported for patients receiving other treatments and hydroxyurea (

Figure 4).

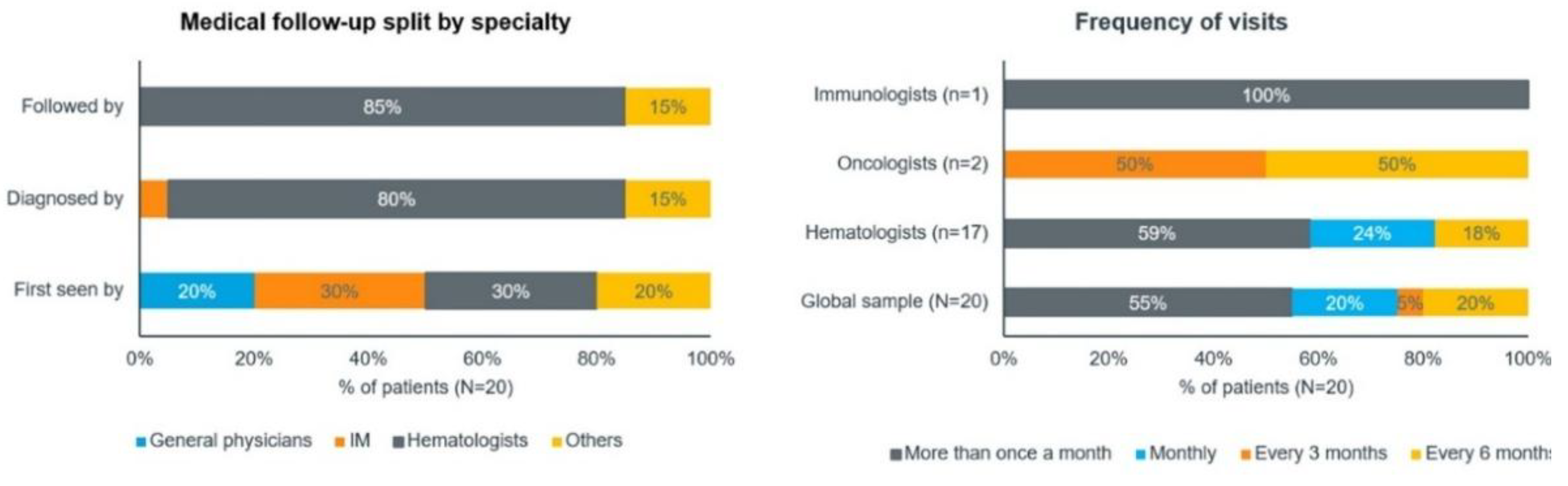

As revealed by the patients, they were monitored by hematologists, with the frequency of follow-up being related to disease control. In line with the qualitative phase, approximately 6 (30%) patients in the quantitative phase initially consulted internal medicine specialists and another 6 (30%) patients consulted hematologists. Overall, about 16 (80%) patients were diagnosed and 17 (85%) were followed by hematologists (

Figure 5).

In the quantitative phase, most patients (n=11, 55%) visited their doctor more than once a month. This trend was similar for hematologist and immunohematologist visits, but oncologist visits were less frequent, with follow-ups every 3–6 months. A total of 2 out of 3 (67%) patients treated with phlebotomies visited the hospital once a year, while the rest visited the doctor more than once a month.

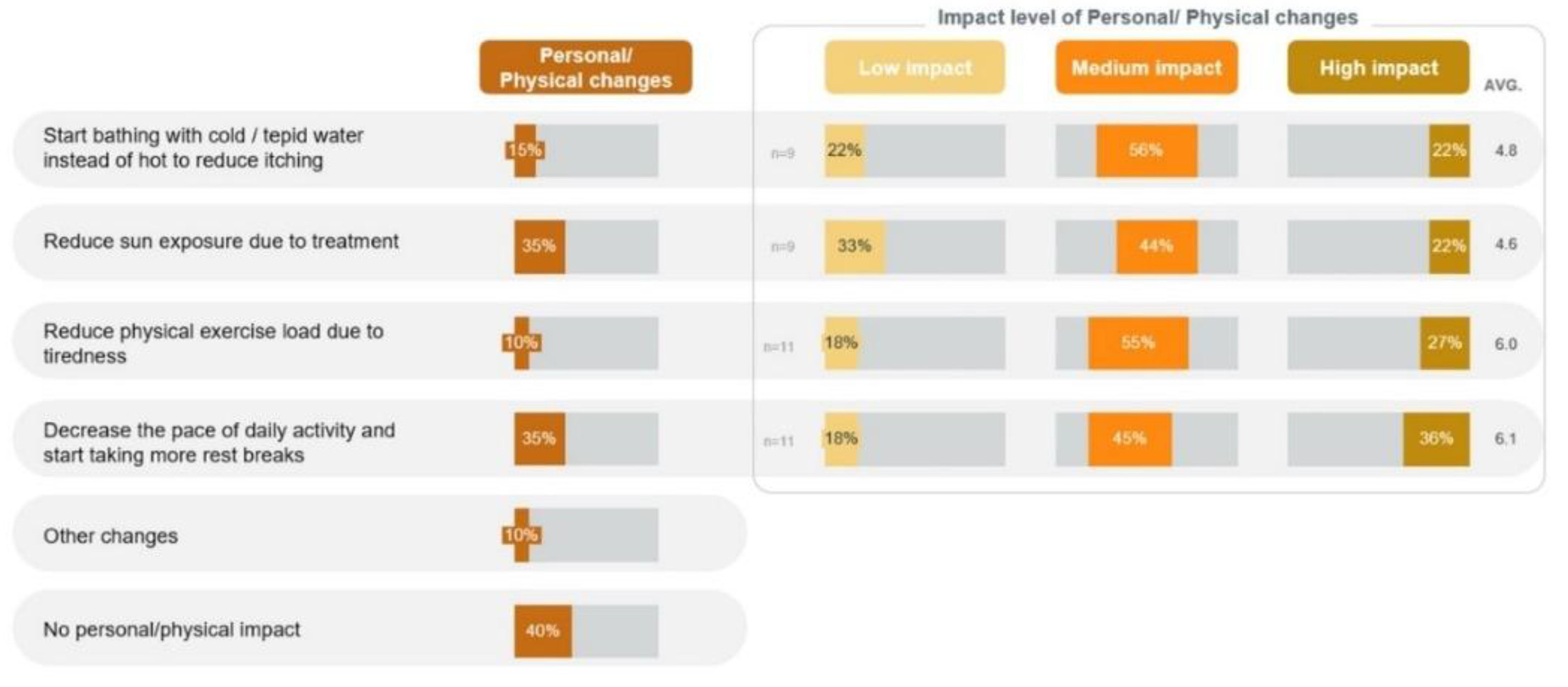

3.2. Impact on QoL

Due to nonspecific symptoms, although 8 (40%) patients reported no significant physical or personal impact, other patients experienced notable effects in the quantitative phase. These included a decrease in the pace of daily activities and taking more rest breaks (n=7, 35%), reducing sun exposure (n=7, 35%), and bathing with cold or tepid water instead of hot to reduce itching (n=3, 15%) (

Figure 6).

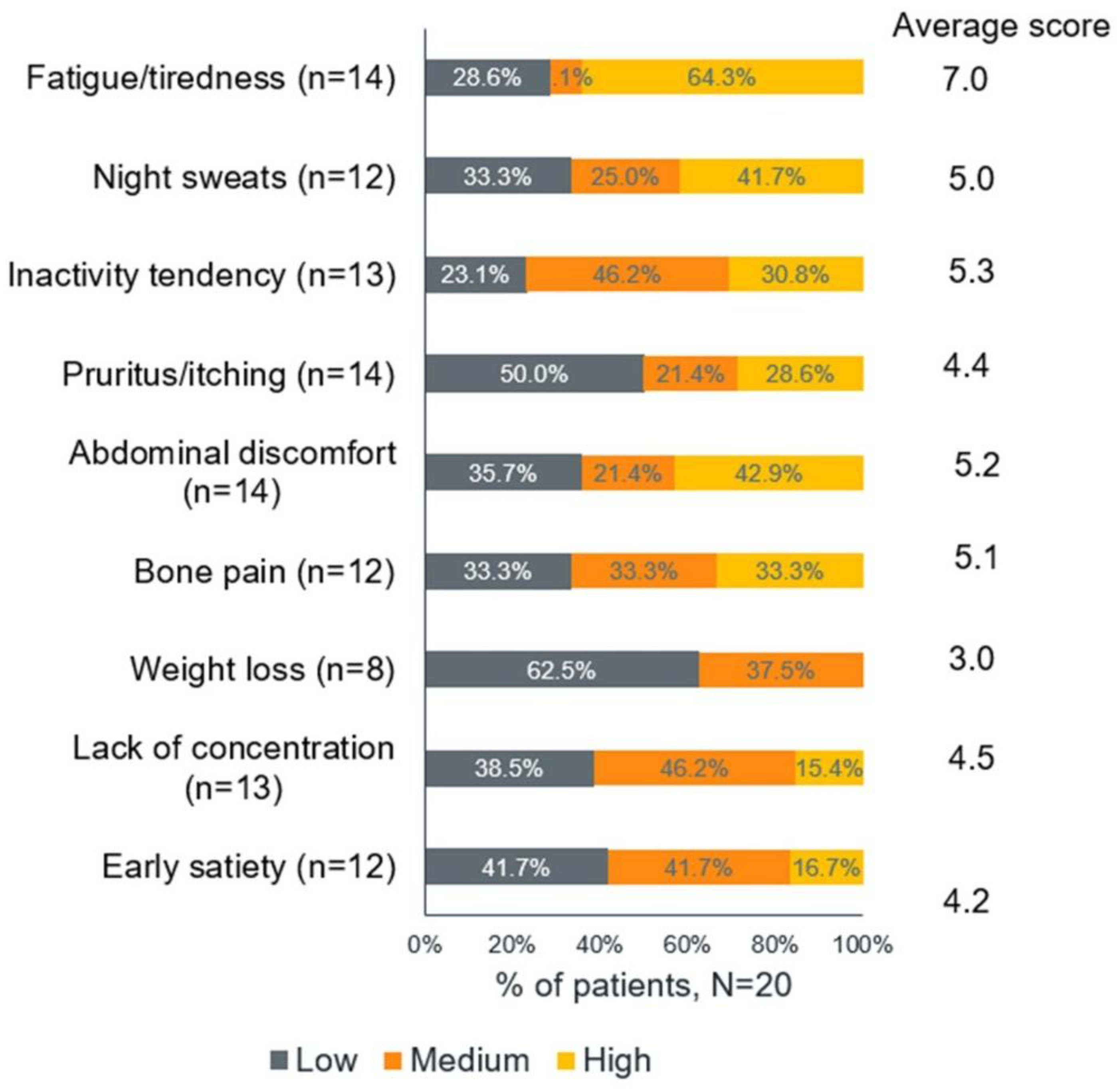

Among those who adopted these strategies, 4 out of 11 (36%) who slowed their pace, 2 out of 9 (22%) who reduced sun exposure, and 2 out of 9 (22%) who changed their bathing habits reported that these changes had a high impact on their lives. Among the symptoms, fatigue and tiredness (64.3%) had the highest impact on the patients' lives (

Figure 7).

Only one patient experienced an acute cardiovascular event, which included a heart attack and stroke. The patients’ daily routines also changed reported by 36% of patients, but they did not perceive these changes as significantly impactful.

On an emotional front in the quantitative phase, the patients stated that the fear and anxiety they experienced upon diagnosis evolved over time with their experience of achieving control of their disease and their attitude to focus on day-to-day activities rather than having anxiety. Experience of fear/anxiety about the future was the most common emotional change (n=14, 70%), with 9 out of 17 (47%) patients reporting that it had high impact on their lives (

Figure 8).

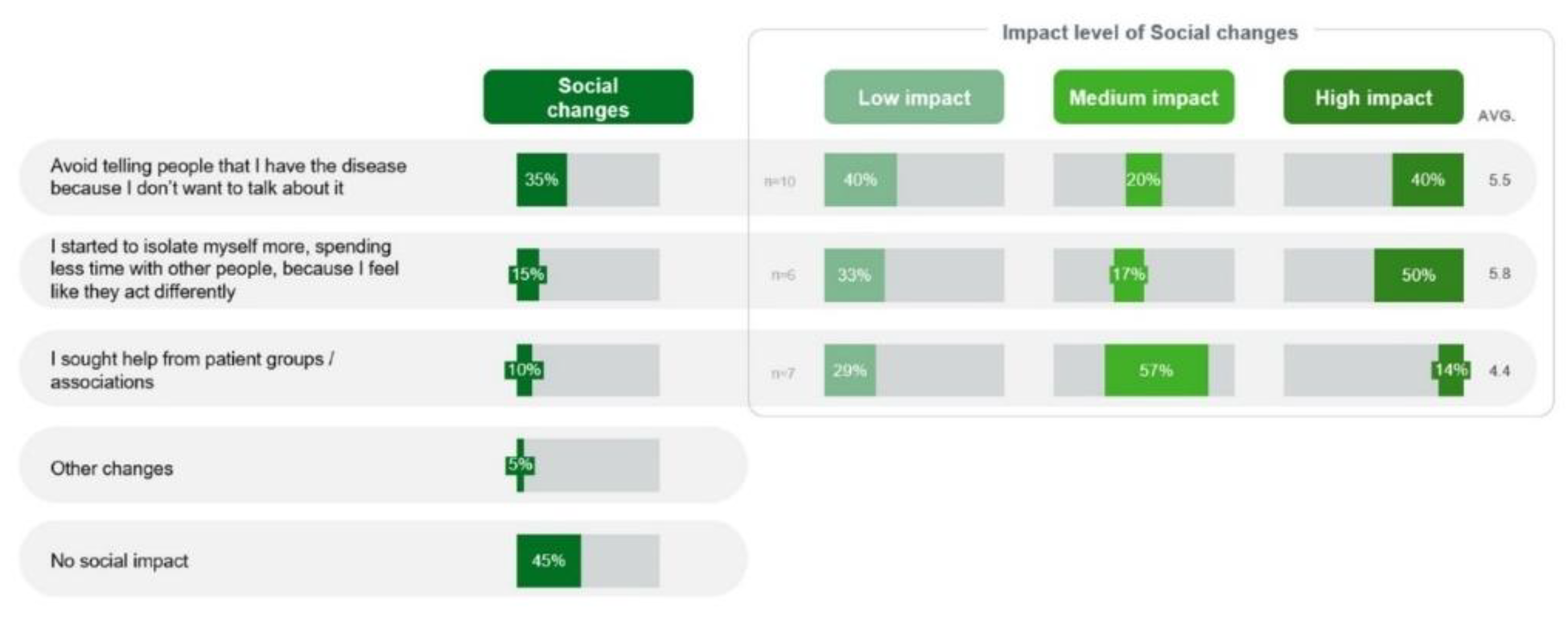

Socially, isolation was a major impact mainly because of difficulties due to the disease or stigma of fragility in the quantitative phase. Total 3 (15%) patients experienced isolation, and 3 out of 6 (50%) patients reported that it had a high impact on their lives. Avoiding discussion about their disease because they did not want to talk about it was reported by 7 (35%) patients, and 4 out of 10 (40%) such patients considered this social change to have a high impact (

Figure 9).

Professionally, the patients indicated no increase in absenteeism, but experienced the need to adjust or change their role or function in the quantitative phase. Discontinuation of work or early retirement was experienced by 4 (20%) patients, which had a high impact on the professional lives of 4 out of 5 (80%) such patients (

Figure 10).

Patient quotes detailing the impact on QoL are outlined in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Impact on quality of life of patients with polycythemia vera—supporting quotes.

Table 1.

Impact on quality of life of patients with polycythemia vera—supporting quotes.

| Type of impact |

Supporting quotes |

| Physical |

“The only impediment is that I back hurts. (…) I don't itch anymore. At first it was very itchy, it was horrible. Taking a shower I cried.”

“I don't feel anything related to the disease. By chance now I have been here with a little pain, which I don't know if it is related to the disease or not, behind the scenes, on the back.”

"No, I don't have (manifestation of symptoms). In addition to migraines and tiredness, no.”

“He was a very dynamics, now I am much less, because with the age I went losing dynamism.”

“When the question of blush, I stopped showering with hot water, I went to cold, but the truth is that it didn't get much better. I had to do an antihistamine and has remained calm until today.” |

| Emotional |

“Very fear. Quiet, quite. The doctor was a very important pillar, I always reassured, always made sure I focused.”

“Not scared, I was left more thoughtful.”

“I felt alone in this whole process.”

“He explained that it was in blood, for me to stay rested what it wasn't cancer, (...) I was quite worried, but then I saw friendly people mine have cancer and leave in the meantime, and I'm still here.”

“When I talked about PV, they asked me ' Poli what?' and I was even more scared, because if the Doctors themselves didn't know what it was, how could I know?”

“The big problem with Polycythemia Vera is that it confused with leukemia and another type of cancer.”

“So, if I feel good and if I’m not too bad, perfect. Ball forward and at this point it’s not a concern.” |

| Social and professional |

“(…) but I see that people felt sorry (…) and that made me take refuge at home a lot. So, it’s a snowball, the more I’m alone, the more reserved I am at home, the more I want to be.”

"I am renovated put medical advice. (…) When I had big stress phases, for professional issues, all my values changed substantially.”

“I still I haven't changed my habits in my life.”

“I haven’t changed anything. except my professional life. I'm calm. (…) I take things differently.”

"(…) I was in a job I liked, I felt fulfilled completely in the job I was in and I had to change section.”

“No, it was just this time during the pandemic. (…) But otherwise, given this situation, I haven’t been out of work once again. Even when I took this paper to the Social Security Medical Board, they said that I could work with what I had there and I did.” |

| Practical |

“You have to take certain precautions that you didn't have. I can't be exposed to the sun because of Hydroxyurea. You have to have be more careful with bruises, just in the simple fact that brush your teeth. Right food care also. You have to be more careful.”

“Every day I take a walk, instead of going through a deserted area I try to go through the city center, I get distracted, I see people, I talk, I don't remember, I don't feel so tired, if I have to stop I will stop, if you have to go to coffee I'm going to the cafe...”

“I stopped going to the pool. I had a swimming pool at home and didn't use it. did hiking, at least once a week, I stopped doing, because I'm not walking straight. At first it was tiredness, but now it is lack of balance. And because last year I fell in the street and broke my wrist, now I'm very scared.”

“What moved me the most It was a year and a half ago when I started to feel, same in professional terms, tiredness mental, I started to feel like I wasn't being myself, I started to want to deceive myself and use stratagems of schedule meetings, for example, always in the morning (...) I felt much more tired and no ability to think quickly and with some white …” |

3.3. Patient Awareness and Unmet Needs

The patients did not always access all the information about PV at diagnosis, but learning occurred over time. This was reflected in the quantitative results, with most (n=18, 90%) of the patients having low disease knowledge before diagnosis (

Table 2).

The patients stated that they used the internet for initial personal research, but trust in the hematologist quickly replaced it. During the quantitative phase, most patients (n=19, 95%) relied on their hematologist as the main source of information about the disease, while 13 (65%) patients also used the internet. Most patients (n=15, 75%) sought more information about their disease, with an equal need felt at the time of diagnosis, treatment initiation, and during follow-up (

Table 2). The sources of information used at diagnosis and for clarifying questions were similar, with reduced use of the internet and social media. The patients seemed to adopt a selective approach to information about the disease, showing no interest in learning more. The patients appeared to understand the correlation between the disease and an increased cardiovascular risk. Most patients (n=18, 90%) reported being unaware of any patient support groups, but when specifically asked about APCL, 13 (65%) patients stated that they were aware of them.

To feel emotionally safe, patients with PV tended to adopt an approach that did not focus on anticipating the future. In the quantitative phase, the lack of information to better understand diagnosis/disease progression was the main unmet need (n=16, 80%), which also correlated with only 8 (40%) patients reporting a high level of understanding at the time of the study (

Table 2). Patient quotes regarding patient awareness and future expectations are outlined in Supplementary

Table 2.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to capture the patient voice in the context of PV in Portugal. The qualitative phase provided insights into the challenges patients face in managing their disease, which informed the design of the quantitative phase to identify the need for supportive approaches. The key findings of the study were that PV had a substantial influence on many areas of the patients' lives and that they encountered delays in diagnosis, which they believed might affect their prognosis. The results highlight an unmet need for support programs for health care professionals to facilitate an early diagnosis and for education programs for patients to improve their QoL.

Despite the availability of the 2016 World Health Organization diagnostic criteria, diagnosing PV is challenging because of its broad, heterogeneous, and nonspecific initial symptoms such as fatigue, night sweating, problems with concentration, and itching [

6]. Since a complete blood count is not commonly recommended in routine screening by primary care guidelines, PV is frequently diagnosed incidentally during blood tests for other conditions [

6]. As a result, many asymptomatic patients or those with minimal symptoms remain undiagnosed, delaying diagnosis [

6]. For example, in the current study, 70% of the patients had their first medical consultation due to changes in clinical lab test values, and the time from the first symptoms to the diagnosis ranged from one to four years for 30% of the patients, underscoring this delay. Additionally, some patients are diagnosed with PV during follow-up lab tests conducted for a thrombotic event; one patient (5%) in the current study reported such an incident. In a large observational study involving 1545 patients from Italy, Austria, and the US, 16% of patients had thrombosis before or at the time of presentation [

16]. Delayed diagnosis adversely impacts the future prognosis of patients, resulting in suboptimal treatment and an increased risk of thrombotic complications [

17]. According to these results and the literature, training programs are necessary to increase general practitioners' and internal medicine specialists' awareness of PV, facilitating early diagnosis and timely referral to hematologists.

The patients in the current study indicated that PV significantly impacted various aspects of their lives, including the emotional, professional, social, and physical domains. An online survey among 1788 patients with MPNs reported that fatigue is a common symptom of PV negatively affecting normal daily activities (69%), aspirations (65%), travel (61%), long-term planning (58%), and vacation planning (57%) [

18]. In the current study, fatigue was the most frequent symptom, experienced by 35% of the patients, with approximately 64% reporting a high impact on their lives. PV also has a remarkable impact on patients’ work life, leading many patients to opt for early retirement or a job change. In a previous online survey involving 592 patients with MPNs, about 51% of participants reported a change in their employment status, including leaving their job (30%), taking medical disability leave (25%), and reducing work hours (22%) [

19]. Similarly, 35% of the patients in the current study reported quitting their job, taking early retirement, or changing their job role due to PV. Patients with PV also experience anxiety and social isolation, as reported by most patients in the current study (anxiety: 70%, social isolation: 35%). These findings emphasize a need for developing programs for psychological support to help patients cope with the social burden associated with PV. Patient awareness campaigns are necessary to help patients better adjust to life with this disease. Raising awareness about patient support groups could be one option; only about 10% of the patients in the current study were aware of such groups. There are rare disease patient advocacy groups that provide educational resources for patients and their families, offering good support and a sense of community, proving the adage, “alone we are rare, together we are strong’’[

20].

This study is limited by a small sample size, and therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution. However, this study is the first to document patient-reported experiences of PV within the Portuguese population.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the study provided insights into the experiences of patients with PV and helped identify unmet needs. The patients reported delays in diagnosis and referral to hematologists, emphasizing a strong need for physician education to facilitate early diagnosis and optimal treatment. The patients also reported fatigue, changes in daily routine, pain with phlebotomy, social isolation, and work life changes. Patient awareness or educations programs, in collaboration with patient associations, are essential to improve QoL by ensuring accurate and accessible information about the disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, File S1. Supplementary material_questionnaire, File S2. Supplementary material_discussion guide, and File S3. Supplementary Tables.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. Francesca Pierdomenico: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualization, project management, funding. Inês Costa: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualization, project management, funding. Nilza Gonçalves: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualization, project management, funding. João Malhadeiro: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualization, project management, funding. Daniel Brás: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualization, project management, funding. Ana Bagulho Lopes: Methodology, study implementation, data collection and analysis. Hugo Pedrosa: Methodology, study implementation, data collection and analysis, writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, project management. Lara Cunha: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing. Manuel Abecasis: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Novartis, Portugal.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Before the initiation of the interview, the participants were informed that this study was being conducted in accordance with the codes of conduct of the APIFARMA (Portuguese Association of the Pharmaceutical Industry), BHBIA (British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association), EphMRA (European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association), and APODEMO (Associação Portuguesa Empresas De Estudos Mercado e Opinião), as well as applicable standards regarding privacy and protection of personal data. The patients provided their explicit consent to participate before the initiation of the interview. The quantitative questionnaire also had an initial statement where the patients provided their consent.s.

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary Content is sent in attachment/supplementary material has been sent within this submission.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Leena Patel (PhD), Rosario Vivek Magimaidas (PhD), and Shlok Kumar (MA) of IQVIA, funded by the study sponsors.

Conflicts of Interest

IC, NG, JM and DB are employees of Novartis. ABL and HC are employees of IQVIA. FP, LC and MA don’t not have any competing interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Form |

| PV |

Polycythemia vera |

| MPN |

Myeloproliferative neoplasm |

| QoL |

Quality of life |

| PJM |

Patient journey map |

| APCL |

Portuguese Association Against Leukemia |

| CAWI |

Computer-assisted web interviews |

References

- Grunwald, M.R.; Burke, J.M.; Kuter, D.J.; Gerds, A.T.; Stein, B.; Walshauser, M.A.; Parasuraman, S.; Colucci, P.; Paranagama, D.; Savona, M.R. Symptom burden and blood counts in patients with polycythemia vera in the United States: an analysis from the REVEAL study. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia 2019, 19, 579–584. e571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmento, M.; Duarte, M.; Ponte, S.; Sanchez, J.; Roriz, D.; Fernandes, L.; Silva, M.J.M.; Pacheco, J.; Ferreira, G.; Freitas, J. Real-World Clinical Characterisation of Polycythaemia Vera Patients from a Prospective Registry in Portugal: Is Resistance to Hydroxyurea a Reality? Hematology Reports 2023, 15, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titmarsh, G.J.; Duncombe, A.S.; McMullin, M.F.; O'Rorke, M.; Mesa, R.; De Vocht, F.; Horan, S.; Fritschi, L.; Clarke, M.; Anderson, L.A. How common are myeloproliferative neoplasms? A systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of hematology 2014, 89, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulard, O.; Mehta, J.; Fryzek, J.; Olivares, R.; Iqbal, U.; Mesa, R.A. Epidemiology of myelofibrosis, essential thrombocythemia, and polycythemia vera in the E uropean U nion. European journal of haematology 2014, 92, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tefferi, A.; Barbui, T. Polycythemia vera: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. American journal of hematology 2023, 98, 1465–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuykendall, A.T.; Fine, J.T.; Kremyanskaya, M. Contemporary Challenges in Polycythemia Vera Management from the Perspective of Patients and Physicians. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelsson, J.; Andréasson, B.; Samuelsson, J.; Hultcrantz, M.; Ejerblad, E.; Johansson, B.; Emanuel, R.; Mesa, R.; Johansson, P. Patients with polycythemia vera have worst impairment of quality of life among patients with newly diagnosed myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia & lymphoma 2013, 54, 2226–2230. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, M.; Mascarenhas, J. What are the future prospects for polycythemia vera pharmacotherapies for patients with hydroxyurea resistance? Expert Opinion Pharmacotherapy 2024, 25, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orphanet. Knowledge on rare diseases and orphan drugs. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/en/disease/detail/729?name=polycythemia&mode=name (accessed on 05 June 2025).

- McQueen, R.B.; Mendola, N.D.; Jakab, I.; Bennett, J.; Nair, K.V.; Németh, B.; Inotai, A.; Kaló, Z. Framework for patient experience value elements in rare disease: A case study demonstrating the applicability of combined qualitative and quantitative methods. PharmacoEconomics-Open 2023, 7, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCray, A.T.; LeBlanc, K.; Network, U.D. Focus: Rare Disease: Patients as Partners in Rare Disease Diagnosis and Research. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 2021, 94, 687. [Google Scholar]

- Deal, L.S.; Goldsmith, J.C.; Martin, S.; Barbier, A.J.; Roberds, S.L.; Schubert, D.H. Patient voice in rare disease drug development and endpoints. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 2017, 51, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, E.; Dayal, A.; Li, R. Redefining Rare Disease Care in the Digital Age: Insights and Key Takeaways from a Digital Health Symposium Focused on Empowering Rare Disease Communities. Biomedicine hub 2024, 9, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolz-Johnson, M.; Kenny, T.; Le Cam, Y.; Hernando, I. Our greatest untapped resource: our patients. Journal of Community Genetics 2021, 12, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, S.; Runacres, F.; Poon, P. Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care. BMC health services research 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi, A.; Rumi, E.; Finazzi, G.; Gisslinger, H.; Vannucchi, A.; Rodeghiero, F.; Randi, M.L.; Vaidya, R.; Cazzola, M.; Rambaldi, A. Survival and prognosis among 1545 patients with contemporary polycythemia vera: an international study. Leukemia 2013, 27, 1874–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiman, N.S.H.; Nasir, N.M.; Miptah, H.N.; Saidon, N.; Monir, M.A. Challenges in Diagnosing Polycythemia Vera in Primary Care: A 55-Year-Old Malaysian Woman with Atypical Presentation. The American Journal of Case Reports 2024, 25, e944202-944201. [Google Scholar]

- Scherber, R.M.; Kosiorek, H.E.; Senyak, Z.; Dueck, A.C.; Clark, M.M.; Boxer, M.A.; Geyer, H.L.; McCallister, A.; Cotter, M.; Van Husen, B. Comprehensively understanding fatigue in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cancer 2016, 122, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Parasuraman, S.; Paranagama, D.; Bai, A.; Naim, A.; Dubinski, D.; Mesa, R. Impact of Myeloproliferative neoplasms on patients’ employment status and work productivity in the United States: results from the living with MPNs survey. BMC cancer 2018, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, A.M.; O’Boyle, M.; VanNoy, G.E.; Dies, K.A. Emerging roles and opportunities for rare disease patient advocacy groups. Therapeutic Advances in Rare Disease 2023, 4, 26330040231164425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).