1. Introduction

Palliative care (PC), as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), is a holistic approach aimed at improving the quality of life for patients and their families facing life-threatening illnesses. It addresses physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions to provide comprehensive care. PC is ideally provided by a multidisciplinary team, including physicians, nurses, social workers, and spiritual care providers. It can be delivered in various settings, such as private homes, hospices, or PC units in hospitals (Sobanski et al., 2020; WHO, 2016, 2020).

PC, as defined by the WHO, represents the gold standard for end-of-life care. A significant body of research has focused on translating it into practice (e.g., see De Roo et al., 2013; Henson et al., 2020 for reviews). A key issue is the proper assessment and management of symptoms experienced by patients. Common symptoms, regardless of the underlying disease, include physical manifestations like pain and dyspnea, as well as psychological manifestations such as depression and anxiety (Almeida et al., 2022; Schipper et al., 2024; WHO, 2016). Assessing and treating those symptoms in the end-of-life stage improves the quality of life for both patients and families (Kehl et al., 2006; Teno et al., 2004), and in some cases, even prolongs survival (Irwin et al., 2013).

Studies conducted in Europe among terminally ill patients in hospital and nursing home settings have found that pain is the most frequently reported symptom (Høgsnes et al., 2016) and is routinely assessed using standard methods (Bijnsdorp et al., 2023). Similarly, pain is the most documented symptom by healthcare professionals in specialized PC settings (Sjöberg et al., 2021). One explanation is that pain management is relatively straightforward, with opioids being the first-line treatment (Schipper et al., 2024). Dyspnea, characterized by breathing discomfort, shortness of breath, or suffocation, may arise from both the disease itself and treatment-related causes (Crombeen & Lilly, 2020; Sobanski et al., 2020). Although classified as a physical symptom, physiological measures such as respiratory rate show only a weak correlation with the subjective experience of dyspnea (McKenzie et al., 2020). Psychological factors, particularly anxiety, are strongly associated with increased dyspnea severity, highlighting its multidimensional nature (Parshall et al., 2012). Effective management of dyspnea, therefore, requires both pharmacological approaches (e.g., opioids, bronchodilators) and non-pharmacological interventions such as breathing and relaxation exercises, handheld fans, oxygen therapy, or positioning techniques (De Roo et al., 2013; Henson et al., 2020; Seven & Sert, 2023).

Psychological symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, frequently occur in terminally ill patients (Austin et al., 2011; Gontijo Garcia et al., 2023). They can be driven by disease progression, symptom burden and the loss of functional capacity (Bužgová et al., 2015; He et al., 2022). Psychological distress can also stem from the awareness of impending death and loss of hope (Mystakidou et al., 2009). Pharmacological treatments alone have shown limited efficacy, as indicated in a Cochrane review protocol (Schipper et al., 2024). Addressing psychological symptoms requires a combination of pharmacological and psychosocial approaches (Grassi et al., 2014). Non-pharmacological interventions include providing emotional support through active listening, validation, and acknowledgment of a patient’s full range of emotions, which plays a crucial role at the end of life (Gontijo Garcia et al., 2023; Perusinghe et al., 2021; Seven & Sert, 2023).

Psychological symptoms are often underestimated in PC (Bijnsdorp, 2023; Sjöberg et al., 2021). Professionals may also avoid addressing distress due to their own existential fears (Temelli & Cerit, 2021). However, a qualitative study in Sweden found that some PC providers viewed active listening and existential conversations as essential to care, beyond responding to physical needs (Sundström et al., 2019). Evidence on the effectiveness of PC in reducing psychological distress is mixed. A meta-analysis reported some improvements in depressive mood (Kavalieratos et al., 2016), while a more recent review found inconsistent results across studies (Nowels et al., 2023).

Most existing studies adopts a symptom-focused approach, offering clinical guidelines for treating specific symptoms such as dyspnea (Senderovich & Yendamuri, 2019; Crombeen & Lilly, 2020) and psychological distress (Schipper et al., 2024; Perusinghe et al., 2021). However, few have examined the effectiveness of PC in managing these symptoms and its broader impact on perceived care quality. Regarding pain, an intervention study conducted in Japan found that the quality of PC was not dependent on pain management, suggesting that high-quality care is shaped by multiple dimensions beyond pain relief (Maeda et al., 2016). The original concept of “total pain” introduced by Cicely Saunders, the founder of the modern hospice movement, encompassed the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of the dying (Clark, 1999). However, over time, this holistic approach has been medicalized, with an increasing emphasis on controlling physical pain, while its broader psychosocial and existential dimensions received less attention (Ågren et al., 2023).

Addressing dyspnea and psychological distress through PC and its impact on quality of care was examined in an intervention study conducted in Turkey (Seven & Sert, 2023). It found that patients experienced improvements in dyspnea and anxiety, along with a higher quality of life, underscoring the benefits of PC in managing these symptoms. Similarly, a qualitative study from the Netherlands explored the needs of terminally ill hospice inpatients with advanced cancer regarding anxiety management (Zweers et al., 2019). The findings emphasized the importance of open communication with staff, a sense of safety, and respect for individual coping strategies—factors extending beyond medical management and reflecting the holistic approach at the core of PC.

Despite their valuable contributions, previous studies have not examined the effectiveness of PC in addressing a range of physical and psychological symptoms. Moreover, their narrow geographic focus limits generalizing their findings. The present study does not rely on experiments but on the ex-post assessment of various aspects of the last months of life of a sample of 9,237 patients who died between 2006 and 2022 in twenty countries. It aims to assess the effectiveness of PC in managing pain, dyspnea, and psychological distress, as reflected in perceived quality of care , using unique data from the Survey on Health Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Jürges et al. (2019) provided a first exploration of the same data on the link between PC and the rating of care, but they did not combine PC reception with the types of symptoms. Besides, adding two more waves of the SHARE survey, we extend the investigation to assess the potential changes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our rapid survey of the literature on PC leads us to conclude that pain is more straightforward to manage than dyspnea or psychological distress. Therefore, we hypothesize that the interactions between PC reception and experiencing only pain will not significantly impact the rating of end-of-life care. By contrast we hypothesize that the interaction between PC reception and experiencing dyspnea or psychological distress will significantly impact the rating of care. The COVID-19 pandemic period introduced new challenges to care delivery, as policy measures, including the use of personal protective equipment, such as masks, and physical distancing, were implemented (Lourenço et al., 2024). They may have hindered communication between caregivers and patients, affecting the ability to provide warm, empathetic, high-quality care. Moreover, the limited available treatments, particularly on respiratory symptoms in the early stages of the pandemic, may have influenced the delivery of PC. Due to those unique challenges, we expect that PC provision was disrupted during the pandemic.

Our main results are in line with our hypothesis: before the COVID-19 pandemic receiving PC increases the ex-post rating of end-of-life care when the patient suffered from dyspnea or anxiety, not in case of experiencing only pain. During the pandemic, PC was less or even no more effective, pointing to disruptions in care delivery.

The next section 2 describes the data and method.

Section 3 presents the main results, section 4 provides some robustness checks and sketches some differences between European regions, and section 5 concludes.

2. Data and Method

2.1. Data

We use the so called “end-of-life” interviews of the Survey on Health Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). SHARE is a multidisciplinary longitudinal survey covering 27 European countries and Israel. A representative sample of individuals aged 50 and older are interviewed every two years (Börsch-Supan et al., 2013; Bergman et al., 2019). After the death of a respondent an “end-of-life” interview is conducted, where a proxy reports, either face to face or by telephone, on various aspects of the respondent’s final year of life. Since Wave 7 (2017), PC questions were added. SHARE uses the WHO definition of PC (see below), and focuses on three common symptoms: pain, dyspnea, and experiencing anxiety or sadness. Such data are unique as they involve interviews across multiple countries with individuals who had known the deceased (85% are family members). The data also allow to examine whether the assessment of care quality and its links to PC changed during the pandemic.

We use the regular waves 7 (2017), 8 (2019-2020) and 9 (2021-22), and the two extra surveys of June-August 2020 and June-July 2021 (conducted by telephone during the COVID-19 pandemic, see Bergman et al. (2024)). The original dataset contained 12,472 deceased individuals who passed away between 2006 and 2022. Two samples were defined: the first includes those who died before the pandemic (before March 2020), the second those who died during the pandemic (March 2020 to October 2022). Dropping 7 countries where the sample sizes were below 50 observations of deaths after February 2020, we get 6,641 pre-pandemic and 2,596 pandemic deceased in 20 countries.

2.2. Method

Our method relies on examining how the interactions between the reception of PC and the three symptoms (pain, dyspnea, and psychological distress) were associated with the overall ex-post rating of the quality of care, both before COVID-19 and during the pandemic.

The dependent variable is the rating of the

quality of care. In wave 7 it was assessed using a 5-point scale question:

“Overall, how would you rate the care the deceased received in [his/her] last month? (Read out) Excellent, Very good, Good, Fair, Poor”. An apparently small modification was introduced in subsequent waves: three words were added

“Overall, how would you rate the care the deceased received by the staff in [his/her] last month?”. Actually, only Belgian Wallonia and Lithuania modified their translation by adding the words “by the staff”. But more importantly, the question was no more asked in case the proxy had formerly stated that “There was no staff (paid professional) who took care”.

1 This filtering happened for around a fifth of the deceased. However, among them, between 4% (in wave 9) and 8% (in wave 8) had got palliative care. We address this issue in more details below.

Due to the small number of observations in the “poor” category of the rating of care (less than 5% in both subsamples), the “poor” and “fair” categories were combined. This created a variable ranging from 1 (poor-fair) to 4 (excellent), rating the overall quality of care.

The main independent variables are the following:

(a) PC reception is defined based on the proxy’s report on PC reception in the last four weeks of life. The proxy was asked: “In the last four weeks of [his/her] life, did the deceased have any hospice or palliative care? By hospice care, we mean palliative care for terminally ill or seriously ill patients, delivered at home or in an institution. According to the WHO definition, palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual”. Receiving PC was also based on responses regarding the location of death in a hospice, a PC unit, or an inpatient hospice unit within a hospital or institution.

(b) The three symptoms were assessed regarding the deceased’s last month of life: pain, whether the deceased had pain or took medication for pain; dyspnea, whether the deceased had trouble breathing; and psychological distress, whether the deceased had any feelings of anxiety or sadness. To be more precise, we combine the symptoms, as they often appear simultaneously (see e.g., Delgado-Guay et al., 2009), leading to 8 variables ranging from no symptoms (17% of all deaths) to all three symptoms (21%), the next most frequent combinations being “pain and anxiety” (15%) and “pain only” (14%).

The survey offers a large choice of control variables. Socio-demographic characteristics include age when deceased, gender, marital status (married at time of death), education level (primary, secondary, higher education) and area of living (city, town, village), with an additional category for missing values. We also control for the year of death and the relationship with the proxy (spouse, child - including grandchild and child-in-law -, family member, or non-family member), which, together with marital status, may influence both care and the rating of care. Place of death is categorized as home, hospital, nursing or residential home or elsewhere. Mode of interview includes face-to-face or telephone interview. Cause of death is also important as it might influence the need for PC: cancer, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), respiratory diseases, diseases of the digestive system, severe infections, accidents, COVID-19, diseases of the nervous system (including mental and behavioural disorders, decrepitude, dotage or senility), other causes, or unknown cause. All models include Country dummies: Austria (AU), Germany (DE), Sweden (SE), Spain (ES), Italy (IT), France (FR), Denmark (DK), Greece (GR) Switzerland (CH), Belgium (BE), Israel (IS), Czech Republic (CZ), Poland (PL), Hungary (HU), Portugal (PT), Slovenia (SL), Estonia (EE), Croatia (CR), Lithuania (LT), and Romania (RP). Since the definition of hospice as a place of death, and its translation in each local language was clarified after wave 7, we include a wave dummy as an additional control and include the place of death only in our robustness checks.

First, descriptive statistics are presented, for the participants who died before and during the pandemic. Multivariate analyses are then conducted using linear probability models to examine the direct effects of the combination of the three symptoms and PC reception on the rating of quality of care, before and during the pandemic (ordered logistic regressions give the same results). Then, additional interaction terms were included to analyze the link of the association between each symptom combination and PC reception to the quality of care. We also conduct some robustness checks and separate analysis by region.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

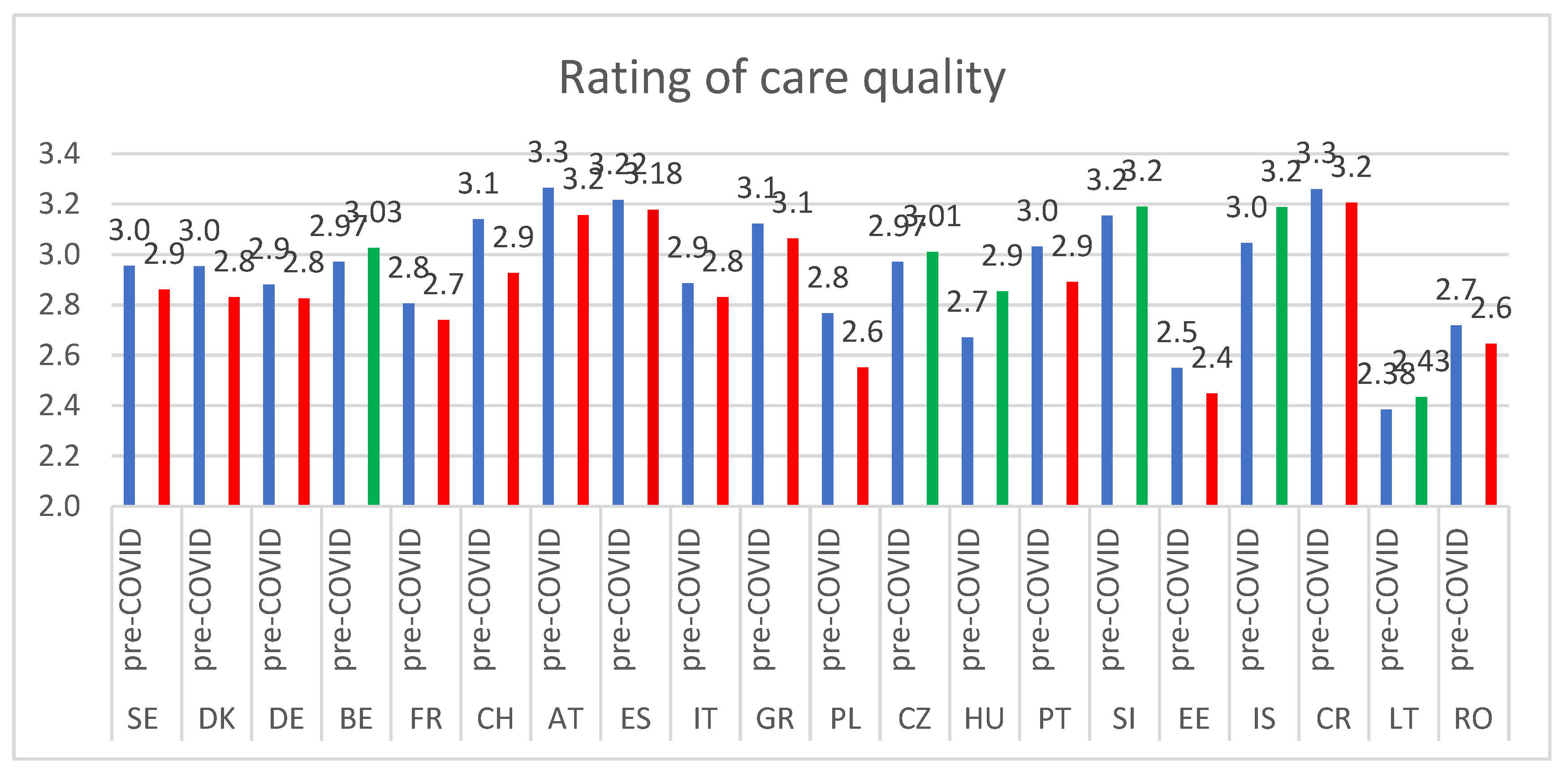

Table 1 and

Table 2 compare the subsamples before and during the pandemic. We comment only on significant differences (computing 95% confidence intervals). The assessed quality of end-of-life care was slightly lower during the pandemic (2.88 over a maximum of 4) compared to the pre-pandemic period (2.95). It was less likely to have been rated excellent (30% versus 34%). Dyspnea, whether felt alone or in combination with pain and anxiety, was reported more frequently during the pandemic (51.8% vs. 46.2%), as could be expected from known common serious COVID-19 symptoms.

With COVID-19 there was an overall increase in the occurrence of any symptoms (+ 1.6 ppt), especially of the combination of pain and dyspnea which went from 12.2 to 14.8% (+2.6 ppt, + 21%), while experimenting only pain diminished (from 14.3 to 12.3%, -2ppt, -14%) (

Table 2).

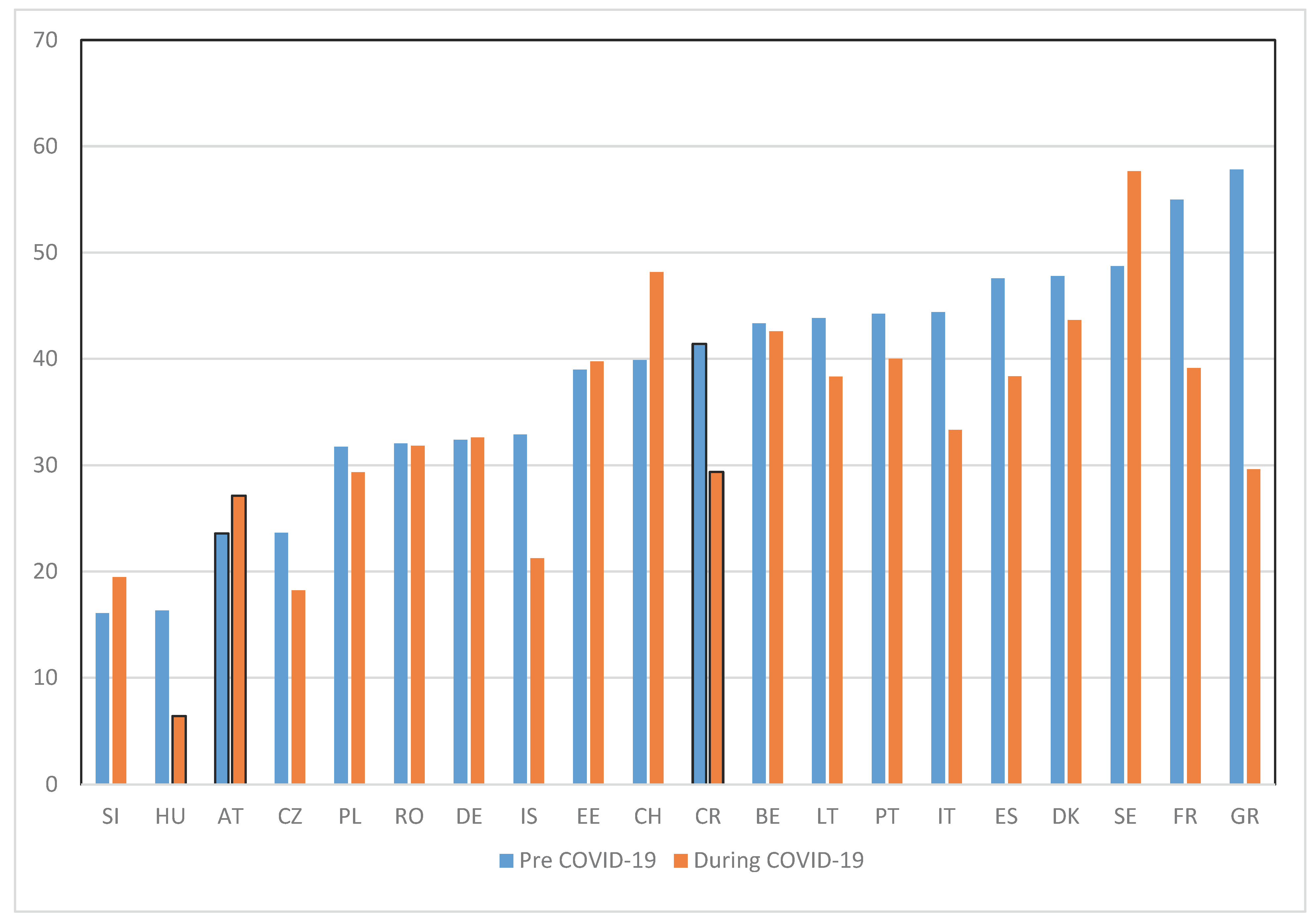

PC reception was more common before the pandemic (37.9%) than during it (32.3%), a 15% decline. Indeed an additional question on not having got PC when needed shows an increase in 15% of this rate for deaths during the pandemic (from 3.5% to 4.1%).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study variables.

| |

Died pre-COVID-19 |

Died during COVID-19 |

| |

Mean / Proportion |

Std. Err. |

Mean /Proportion |

Std. Err. |

| Rating of the quality of care |

2.95 |

0.01 |

2.88 |

0.02 |

| Age |

80.40 |

0.12 |

81.44 |

0.18 |

| Female |

47.7% |

0.6% |

45.2% |

1.0% |

| Married |

52.8% |

0.6% |

51.6% |

1.0% |

| Proxy relationship |

|

|

|

|

| Spouse |

40.7% |

0.6% |

39.4% |

1.0% |

| Child |

37.6% |

0.6% |

39.0% |

1.0% |

| Relative |

6.8% |

0.3% |

6.9% |

0.5% |

| Non-relative |

15.0% |

0.4% |

14.8% |

0.7% |

| Telephone interview |

29.1% |

0.6% |

50.3% |

1.0% |

| Place of death |

|

|

|

|

| At home |

30.3% |

0.6% |

26.5% |

0.9% |

| In hospital |

50.7% |

0.6% |

52.9% |

0.1% |

| In a nursing home |

14.5% |

0.4% |

16.1% |

0.7% |

| In transit |

0.5% |

0.1% |

0.6% |

0.2% |

| Other place |

0.9% |

0.1% |

0.7% |

0.2% |

| In a hospice |

3.3% |

0.2% |

3.1% |

0.3% |

| Cause of death |

|

|

|

|

| Cancer |

26.9% |

0.5% |

21.3% |

0.8% |

| Cardiovascular disease |

38.8% |

0.6% |

31.9% |

0.9% |

| Respiratory diseases |

6.1% |

0.3% |

4.3% |

0.4% |

| Digestive system |

2.6% |

0.2% |

2.4% |

0.3% |

| Severe infections |

6.3% |

0.3% |

5.2% |

0.4% |

| Accident |

0.6% |

0.1% |

1.2% |

0.2% |

| Other cause |

5.1% |

0.3% |

5.3% |

0.4% |

| Cause unknown |

2.7% |

0.2% |

2.0% |

0.3% |

| Nervous system 2

|

11.0% |

0.4% |

10.9% |

0.6% |

| COVID-19 |

- |

- |

15.5% |

0.7% |

| Received palliative care |

37.9% |

0.6% |

32.3% |

0.9% |

| Level of education |

|

|

|

|

| Low |

57.0 |

|

53.4 |

|

| Middle |

30.7 |

|

31.9 |

|

| High |

12.2 |

|

13.9 |

|

| Missing |

0.1 |

|

0.8 |

|

| Area of residence |

|

|

|

|

| Big city or outskirts |

25.8 |

|

22.1 |

|

| Town |

40.7 |

|

41.0 |

|

| Village or rural |

32.1 |

|

35.5 |

|

| Missing |

1.4 |

|

1.4 |

|

| Year of death |

|

|

|

|

| 2006–2015 |

18.4 |

|

- |

|

| 2016 |

23.8 |

|

- |

|

| 2017 |

18.9 |

|

- |

|

| 2018 |

17.4 |

|

- |

|

| 2019 |

18.4 |

|

- |

|

| 2020 |

3.1 |

|

36.4 |

|

| 2021 |

0 |

|

51.4 |

|

| 2022 |

0 |

|

12.2 |

|

| Wave of interview |

|

|

|

|

| 7 (2017) |

49.6 |

|

- |

|

| 8 (2019–20) |

41.0 |

|

4.0 |

|

| 8ca 9ca (2020 & 2021) |

1.0 |

|

28.2 |

|

| 9 (2021–22) |

8.4 |

|

67.8 |

|

| Country distribution |

|

|

|

|

| SE |

5.4 |

|

5.3 |

|

| DK |

4.4 |

|

2.7 |

|

| DE |

3.6 |

|

3.5 |

|

| BE |

6.1 |

|

6.0 |

|

| FR |

4.6 |

|

2.7 |

|

| CH |

2.7 |

|

2.1 |

|

| AT |

4.8 |

|

5.4 |

|

| ES |

8.7 |

|

5.6 |

|

| IT |

6.6 |

|

7.7 |

|

| GR |

6.6 |

|

4.8 |

|

| PL |

4.4 |

|

8.7 |

|

| CZ |

8.0 |

|

7.4 |

|

| HU |

6.0 |

|

4.2 |

|

| PT |

2.4 |

|

2.1 |

|

| SI |

6.3 |

|

7.3 |

|

| EE |

10.2 |

|

10.0 |

|

| IS |

3.3 |

|

3.1 |

|

| CR |

3.4 |

|

4.9 |

|

| LT |

1.1 |

|

2.3 |

|

| RO |

1.6 |

|

4.2 |

|

| Number of observations |

6,641 |

|

2,596 |

|

Table 2.

Frequency of the symptoms combination, Palliative Care reception (PC) and rating of care, pre-COVID-19 and during the pandemic.

Table 2.

Frequency of the symptoms combination, Palliative Care reception (PC) and rating of care, pre-COVID-19 and during the pandemic.

| |

Pre-COVID-19 deaths |

During COVID-19 deaths |

% change pre– vs during COVID-19 |

| |

Symptoms (%) |

PC (%) |

Rating |

Symptoms (%) |

PC (%) |

Rating |

Δ Symptoms |

Δ PC reception |

Δ rating |

| Symptoms combination |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(4)-(1)/(1) |

(5)-(2)/(2) |

(6)-(3)/(3) |

| No symptoms |

17.0 |

17.6 |

3.14 |

15.4 |

16.5 |

3.02 |

-10% |

-6% |

-3.7% |

| Anxiety |

7.6 |

26.5 |

2.90 |

6.7 |

20.6 |

2.74 |

-11% |

-22% |

-5.5% |

| Dyspnea |

8.0 |

28.7 |

3.04 |

8.8 |

21.9 |

2.99 |

+9% |

-23% |

-1.5% |

| Anxiety & dyspnea |

5.4 |

29.1 |

2.90 |

5.7 |

29.1 |

2.74 |

+6% |

0% |

-5.5% |

| Pain |

14.3 |

41.1 |

3.02 |

12.3 |

35.4 |

3.01 |

-14% |

-14% |

-0.5% |

| Pain & anxiety |

14.9 |

50.6 |

2.85 |

14.8 |

41.9 |

2.80 |

-1% |

-17% |

-1.7% |

| Pain & dyspnea |

12.2 |

44.3 |

3.02 |

14.8 |

36.2 |

3.00 |

+21% |

-18% |

-0.6% |

| All 3 symptoms |

20.5 |

49.7 |

2.76 |

21.5 |

41.3 |

2.73 |

+5% |

-17% |

-1.2% |

| Total |

100 |

37.9 |

2.95 |

100 |

32.3 |

2.88 |

- |

-15% |

-2.2% |

Regarding background variables, women were slightly less represented in the pandemic subsample (45.2% vs. 47.7%). The mean age at death was higher during the pandemic (81.4 years vs. 80.4 years). Non-COVID causes of death were reported at reduced frequencies during the pandemic, especially cancers and cardiovascular diseases, due to the significant share of deaths attributed to COVID-19 (15.5%). Home deaths were more common before (30.3%) than during the pandemic (26.5%), when hospital deaths became more frequent (52.9% vs. 50.7%). The type of proxy was relatively similar across periods, but more surveys were conducted by phone rather than face-to-face when the death had happened during the pandemic (

Table 1).

3.2. Econometric specifications

We now turn to the econometric specifications analyzing the perceived quality of care. Two models are estimated: one controls additively for PC reception and symptoms, the other interacts the two control variables. All models are run separately, before and during the pandemic.

Both before and during the pandemic, the quality of care is rated higher if the deceased was older (dying may seem more “natural”), died of cancer, of a heart attack or stroke, of a disease of the nervous system rather than from an infection or a respiratory disease (or from COVID-19 during the pandemic); if he died in a village or a rural area rather than in a big city or a town, had a higher education level (it might be linked to better unobserved care), or if the proxy respondent was a family member (who may be more likely to have had a positive influence on the quality of care, or be more reluctant to confess of poor quality) (see Appendix 1

Table A11 and

Table A12 for the full specification).

Table 3 extracts the main result of the focus of our study, the association of the assessment of quality of care with PC reception and with the seven combinations of the three symptoms. Before the pandemic, PC reception was significantly associated with a higher quality of care (+0.04, p < 0.01, a 1.54% increase on the mean level). The symptoms were linked to lower rating care (-0.34 when pain was combined with anxiety, p<0.01, -11.5%; -0.25 when pain was combined with dyspnea, p<0.10, -6.4%; and the largest effect, -0.40 when all three symptom were present together, p<0.01, -13.6%) (

Table 3, col.1). During the pandemic, PC reception became not significantly associated with a higher quality of care (+0.05). Moreover, only a combination of symptoms including psychological distress remained negatively associated with quality of care (-0.21 to -0.26, p < 0.01, -7.2 to -8.9%) (

Table 3, col.3).

The models with interactions of the types of symptoms combination with PC reception provide interesting insights (having felt no symptoms is the reference category). Before COVID-19, PC was efficient in relieving dyspnea or psychological distress, either when felt alone or in combination with pain. The negative effect of dyspnea, when felt alone, was fully erased, and so were the effect of dyspnea when combined with anxiety. However, the relief from having a combination of pain and dyspnea provided by PC was only partial (significant at the 90% confidence level). The relief when having all three symptoms was significant, if not total. When the person only felt pain (in 14.3% of the cases), PC provided no significant extra benefit (

Table 3, col. 2). During COVID-19, PC did not prove efficient, except when pain and psychological distress were combined (p=0.10) (

Table 3, col. 3). See Appendix 1

Table A12 for the full specifications.

We also ran the same four models with a simplified version of the symptoms variables, as a first robustness check. We no longer combine the three symptoms but introduce each separately (

Table 4). The results are very similar: PC was efficient before the pandemic in fully relieving dyspnea, in reducing the negative effect of psychological difficulties, and had no efficiency in case of pain. PC had no significant effect during the pandemic.

Table 3.

Linear probability models of the rating of the quality of care (without and with added interactions with each combination of symptoms)a.

Table 3.

Linear probability models of the rating of the quality of care (without and with added interactions with each combination of symptoms)a.

| |

Died pre-COVID-19 |

Died during COVID-19 |

| |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

| |

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

| PC reception |

0.04* |

0.03 |

-0.14* |

0.07 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

-0.07 |

0.12 |

| Anxiety |

-0.23*** |

0.05 |

-0.27*** |

0.06 |

-0.25*** |

0.09 |

-0.27*** |

0.097 |

| Dyspnea |

-0.11** |

0.05 |

-0.17*** |

0.06 |

-0.004 |

0.07 |

-0.022 |

0.081 |

| Anxiety & dyspnea |

-0.25*** |

0.06 |

-0.33*** |

0.07 |

-0.23** |

0.09 |

-0.22** |

0.100 |

| Pain |

-0.17*** |

0.04 |

-0.17*** |

0.05 |

-0.07 |

0.07 |

-0.102 |

0.079 |

| Pain & anxiety |

-0.34*** |

0.04 |

-0.38*** |

0.05 |

-0.21*** |

0.07 |

-0.30*** |

0.077 |

| Pain & dyspnea |

-0.19*** |

0.04 |

-0.21*** |

0.05 |

-0.04 |

0.07 |

-0.049 |

0.074 |

| All 3 symptoms |

-0.40*** |

0.04 |

-0.47*** |

0.05 |

-0.26*** |

0.06 |

-0.25*** |

0.073 |

| PC when anxiety |

|

|

0.23** |

0.11 |

|

|

0.10 |

0.22 |

| PC when dyspnea |

|

|

0.26** |

0.11 |

|

|

0.12 |

0.19 |

| PC when anxiety & dyspnea |

|

|

0.37*** |

0.13 |

|

|

0.03 |

0.22 |

| PC when pain |

|

|

0.11 |

0.09 |

|

|

0.16 |

0.16 |

| PC when pain & anxiety |

|

|

0.21** |

0.09 |

|

|

0.30* |

0.16 |

| PC when pain & dyspnea |

|

|

0.17* |

0.09 |

|

|

0.10 |

0.16 |

| PC when all 3 symptoms |

|

|

0.26*** |

0.08 |

|

|

0.05 |

0.15 |

| Nb obs. |

6,641 |

|

6,641 |

|

2,596 |

|

2,596 |

|

| R2 |

0.098 |

|

0.100 |

|

0.117 |

|

0.119 |

|

We conducted some other robustness checks, varying the control variables: adding the place of death control that we did not include because hospice as a place of death entered the definition of PC reception (

Table A21, Appendix 2), leaving aside the wave control (

Table A22, Appendix 2), removing Romania and Lithuania who entered the survey only in wave 7, hence could not report deaths before wave 8 (

Table A23, Appendix 2). The results were robust to those changes.

Table 4.

Linear probability models of the rating of quality of care (without and with added interactions with each of the three symptoms) a.

Table 4.

Linear probability models of the rating of quality of care (without and with added interactions with each of the three symptoms) a.

| |

Died pre-COVID-19 |

Died during COVID-19 |

| |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

| PC reception |

0.04* |

0.03 |

-0.05 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.09 |

| Pain |

-0.13*** |

0.03 |

-0.12*** |

0.03 |

-0.03 |

0.04 |

-0.05 |

0.05 |

| Dyspnea |

-0.05** |

0.02 |

-0.09** |

0.03 |

-0.01 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

| Anxiety or sadness |

-0.19*** |

0.02 |

-0.23*** |

0.03 |

-0.20*** |

0.04 |

-0.22*** |

0.04 |

| PC when pain |

|

|

-0.01 |

0.05 |

|

|

0.09 |

0.09 |

| PC when dyspnea |

|

|

0.10** |

0.05 |

|

|

-0.11 |

0.08 |

| PC when anxiety or sadness |

|

|

0.11** |

0.05 |

|

|

0.04 |

0.08 |

| Nb obs. |

6,641 |

|

6,641 |

|

2,596 |

|

2,596 |

|

| R2 |

0.098 |

|

0.099 |

|

0.115 |

|

0.116 |

|

Due to the change of questionnaire routine after wave 7 we also conducted two more robustness checks, running the models separately for wave 7 (where the question on the rating of care was asked for all deceased) and for pre-pandemic deaths in the subsequent waves where it was asked only when some paid care was provided in the last month of life (see above, footnote 3). The models run on wave 7 yield similar results as those we got above in

Table 3, pre-pandemic deaths (see Appendix 3,

Table A31). When running them on the subsamples of waves 8 to 9 for pre-pandemic deaths the results are much less significant, even if they go in the same direction: PC was efficient when anxiety and dyspnea or when pain and dyspnea were felt (Appendix 3,

Table A32). The filtering of the question left aside some deceased who benefited from PC but were not asked the filtered question because “no paid staff was used in the last month of life”.

If we group countries by large regions, it appears that, before the pandemic, in the two Nordic countries (Sweden and Denmark), PC was efficient in anxiety relief, whereas in the Central European countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland) PC was most efficient for dyspnea. During the pandemic, PC became inefficient in most regions. Regarding dyspnea, a negative association, was even observed in quality-of-care rating for patients experiencing dyspnea who received PC during COVID-19 in the Northern and Mediterranean countries. Relief from anxiety was still efficient in Central Europe. Further details on cross-country variations in PC reception and its effectiveness in symptom management can be found in the Appendix A4.

4. Discussion

Our study investigated whether PC reception is beneficial in terms of ex post perceived quality of care for individuals experiencing three symptoms, pain, dyspnea, and anxiety or sadness and any combination of them. Our first hypothesis, that PC reception plays a limited additional role in relieving pain when it was the only symptom (which happens in 14% of the cases in our sample), was supported by SHARE data, showing its lack of effectiveness for individuals experiencing only pain and to a lesser extent, in some specifications, its lower efficiency for those experiencing both pain and dyspnea, or the three symptoms together. Our findings raise two interpretations. The first is that pain is managed through pharmacological care, with no clear added benefit from PC. This is in line with a study among Japanese cancer patients (Tagami et al., 2024). A second interpretation is that PC has yet to develop effective strategies for managing complex pain at the end of life. This is in line with a German study, which found that pain relief among cancer terminally ill patients remains insufficient and should include not only medication, but also psychological and behavioral support (Ramm et al., 2025). This interpretation aligns with the idea that end-of-life pain is more than physical, as described by “total pain” (Clark, 1999; Ågren et al. 2023). If PC does not fully address these multidimensional aspects of pain, its impact on perceived care quality in case of pain only may remain limited.

Our second hypothesis, that PC is more likely to play a role in cases of dyspnea and psychological distress (anxiety or sadness), as both require a comprehensive approach incorporating pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, was confirmed by the SHARE data and aligns with previous studies (Seven & Sert, 2023; Zweers et al., 2019). However, disparities in access to care, integration across healthcare levels, and resource availability continue to impact equitable PC delivery. These gaps also vary between countries (Axelsson, 2022; Payne et al., 2022). If we group counties by region, it appears that before the pandemic in the two Nordic countries (Sweden and Denmark) PC was efficient in anxiety relief, whereas in the central European countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland) PC was more efficient for dyspnea. The sample sizes do not allow a precise exploration of those differences.

As for the potential benefits of PC during the COVID-19 pandemic, we find a deterioration: PC was no longer significantly associated with an improved quality of care. Additionally, none of the symptoms benefited from PC reception, except when pain and psychological distress were felt together. These results align with reports of disruptions in PC provision during the pandemic with reduced access to PC services and staff shortages. Additionally, family presence was significantly restricted. Family involvement is recognized as a core component of PC, providing reassurance and emotional support, as we may indirectly spot with our finding of a higher rating of care by family members. Moreover, physical distancing and the use of masks limited human connection (Chapman et al., 2020). A pre-COVID study (Sundström et al., 2019) highlights the importance of physical contact in providing comfort and reducing feelings of abandonment.

Regarding dyspnea, a negative association, though not in all our specifications, was even observed in quality-of-care ratings for patients experiencing dyspnea who received PC during COVID-19 in some regions. Our sample size is too small to further explore the interrelationship between COVID-19, PC reception, respiratory conditions, and perceived quality of care. Has PC provision recovered post-pandemic, or has it improved with lessons learned? Future waves of SHARE will be valuable in addressing this issue.

A final note on the change in questionnaire routine after wave 7: it may partly blur the comparison of the effect of PC before and after COVID-19, even if our robustness checks lead to conclude that our results remained valid. Future changes in the end-of-life questionnaire should be weighed against the risk of destroying time comparability.

In conclusion, the study suggests that PC is efficient and beneficial for managing dyspnea and psychological distress at the end of life, both of which require a multidimensional approach. However, the COVID-19 period was linked to severe disruptions in PC efficiency.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments:This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 including the SHARE-COVID-19 Surveys (DOIs:10.6103/SHARE.w1.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w2.900, , 10.6103/SHARE.w4.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w6.900,10.6103/SHARE.w7.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w8.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w8ca.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w9.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w9ca900 ) see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details.

The SHARE data collection has been funded by the European Commission, DG RTD through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812), FP7 (SHARE-PREP: GA N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: GA N°227822, SHARE M4: GA N°261982, DASISH: GA N°283646) and Horizon 2020 (SHARE-DEV3: GA N°676536, SHARE-COHESION: GA N°870628, SERISS: GA N°654221, SSHOC: GA N°823782, SHARE-COVID19: GA N°101015924) and by DG Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion through VS 2015/0195, VS 2016/0135, VS 2018/0285, VS 2019/0332, VS 2020/0313, SHARE-EUCOV: GA N°101052589 and EUCOVII: GA N°101102412. Additional funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01UW1301, 01UW1801, 01UW2202), the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, BSR12-04, R01_AG052527-02, R01_AG056329-02, R01_AG063944, HHSN271201300071C, RAG052527A) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-eric.eu).

More precisely this paper uses Waves 1–2 and 4–9:

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 1. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w1.900

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 2. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w2.900

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 4. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w4.900

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 5. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w5.900

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 6. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w6.900

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 7. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w7.900

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 8. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w8.900

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 8. COVID-19 Survey 1. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w8ca.900

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 9. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w9.900

SHARE-ERIC (2024). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 9. COVID-19 Survey 2. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w9ca.900

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1

Table A11.

Linear probability models of the rating of the quality of care with added interactions with each combination of symptoms: Pre-pandemic.

Table A11.

Linear probability models of the rating of the quality of care with added interactions with each combination of symptoms: Pre-pandemic.

| |

Died pre-COVID-19 |

Died pre-COVID-19 |

| |

(1) |

(2) |

| |

Coef. |

Std. Err. |

P>|t| |

Coef. |

Std. Err. |

P>|t| |

| Age |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.000 |

0.005 |

0.001 |

0.000 |

| Female |

0.04 |

0.02 |

0.145 |

0.036 |

0.025 |

0.144 |

| Married |

0.07 |

0.03 |

0.024 |

0.069 |

0.031 |

0.028 |

| Proxy relationship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non relative |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Spouse |

0.22 |

0.04 |

0.000 |

0.227 |

0.041 |

0.000 |

| Child |

0.16 |

0.03 |

0.000 |

0.161 |

0.035 |

0.000 |

| Relative |

0.13 |

0.05 |

0.011 |

0.133 |

0.051 |

0.010 |

| Telephone interview |

0.07 |

0.03 |

0.010 |

0.076 |

0.028 |

0.008 |

| Cause of death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cancer |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Cardiovascular disease |

-0.08 |

0.03 |

0.014 |

-0.077 |

0.031 |

0.015 |

| Respiratory diseases |

-0.14 |

0.05 |

0.009 |

-0.139 |

0.054 |

0.009 |

| Digestive system |

-0.32 |

0.08 |

0.000 |

-0.326 |

0.082 |

0.000 |

| Severe infections |

-0.33 |

0.05 |

0.000 |

-0.328 |

0.054 |

0.000 |

| Accident |

-0.23 |

0.16 |

0.150 |

-0.231 |

0.157 |

0.143 |

| Nervous system |

-0.04 |

0.04 |

0.413 |

-0.033 |

0.044 |

0.453 |

| COVID-19 |

- |

|

|

- |

|

|

| Other causes |

-0.19 |

0.06 |

0.001 |

-0.190 |

0.057 |

0.001 |

| Unknown |

-0.27 |

0.08 |

0.001 |

-0.270 |

0.080 |

0.001 |

| Level of education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Low |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Middle |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.497 |

0.022 |

0.028 |

0.428 |

| High |

0.10 |

0.04 |

0.011 |

0.096 |

0.038 |

0.011 |

| Missing |

-0.62 |

0.43 |

0.146 |

-0.627 |

0.431 |

0.145 |

| Area of residence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Big city or suburbs |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Town |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.205 |

0.035 |

0.029 |

0.225 |

| Rural or village |

0.11 |

0.03 |

0.001 |

0.110 |

0.032 |

0.001 |

| Missing |

0.18 |

0.11 |

0.093 |

0.176 |

0.105 |

0.094 |

| Year of death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2006–2015 |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| 2016 |

-0.01 |

0.04 |

0.748 |

-0.009 |

0.036 |

0.810 |

| 2017 |

0.06 |

0.04 |

0.110 |

0.067 |

0.039 |

0.088 |

| 2018 |

0.07 |

0.05 |

0.185 |

0.073 |

0.052 |

0.163 |

| 2019 |

0.09 |

0.05 |

0.092 |

0.094 |

0.052 |

0.074 |

| 2020 |

0.04 |

0.08 |

0.641 |

0.037 |

0.080 |

0.643 |

| Wave of interview |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 (2017) |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| 8 (2019–20) |

-0.17 |

0.04 |

0.000 |

-0.174 |

0.041 |

0.000 |

| 8ca 9ca (2020 & 2021) |

-0.120 |

0.119 |

0.316 |

-0.120 |

0.119 |

0.312 |

| 9 (2021–22) |

-0.21 |

0.05 |

0.000 |

-0.206 |

0.054 |

0.000 |

| Country distribution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SE |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| DK |

0.01 |

0.08 |

0.908 |

0.009 |

0.082 |

0.914 |

| DE |

-0.01 |

0.08 |

0.865 |

-0.012 |

0.082 |

0.882 |

| BE |

0.05 |

0.07 |

0.466 |

0.053 |

0.072 |

0.461 |

| FR |

-0.12 |

0.08 |

0.141 |

-0.120 |

0.079 |

0.127 |

| CH |

0.18 |

0.09 |

0.040 |

0.174 |

0.086 |

0.042 |

| AT |

0.39 |

0.07 |

0.000 |

0.390 |

0.072 |

0.000 |

| ES |

0.31 |

0.07 |

0.000 |

0.315 |

0.067 |

0.000 |

| IT |

-0.03 |

0.07 |

0.637 |

-0.036 |

0.073 |

0.622 |

| GR |

0.21 |

0.07 |

0.002 |

0.202 |

0.067 |

0.003 |

| PL |

-0.11 |

0.08 |

0.174 |

-0.103 |

0.079 |

0.193 |

| CZ |

0.10 |

0.07 |

0.163 |

0.098 |

0.068 |

0.151 |

| HU |

-0.18 |

0.08 |

0.017 |

-0.179 |

0.077 |

0.021 |

| PT |

0.17 |

0.10 |

0.072 |

0.169 |

0.097 |

0.083 |

| SI |

0.24 |

0.07 |

0.001 |

0.239 |

0.074 |

0.001 |

| EE |

-0.39 |

0.07 |

0.000 |

-0.383 |

0.068 |

0.000 |

| IS |

0.15 |

0.08 |

0.066 |

0.151 |

0.084 |

0.073 |

| CR |

0.40 |

0.08 |

0.000 |

0.405 |

0.080 |

0.000 |

| LT |

-0.40 |

0.13 |

0.001 |

-0.398 |

0.125 |

0.001 |

| RO |

-0.06 |

0.11 |

0.575 |

-0.060 |

0.111 |

0.588 |

| PC |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.084 |

-0.145 |

0.065 |

0.027 |

| Symptom profile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No symptoms |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Anxiety |

-0.23 |

0.05 |

0.000 |

-0.274 |

0.058 |

0.000 |

| Dyspnea |

-0.11 |

0.05 |

0.020 |

-0.166 |

0.056 |

0.003 |

| Anxiety & dyspnea |

-0.25 |

0.06 |

0.000 |

-0.332 |

0.066 |

0.000 |

| Pain |

-0.17 |

0.04 |

0.000 |

-0.171 |

0.048 |

0.000 |

| Pain & anxiety |

-0.34 |

0.04 |

0.000 |

-0.381 |

0.054 |

0.000 |

| Pain & dyspnea |

-0.19 |

0.04 |

0.000 |

-0.214 |

0.052 |

0.000 |

| All 3 symptoms |

-0.40 |

0.04 |

0.000 |

-0.467 |

0.048 |

0.000 |

| PC and … |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Anxiety |

|

|

|

0.230 |

0.110 |

0.037 |

| Dyspnea |

|

|

|

0.264 |

0.107 |

0.013 |

| Anxiety & dyspnea |

|

|

|

0.371 |

0.127 |

0.003 |

| Pain |

|

|

|

0.111 |

0.088 |

0.208 |

| Pain & anxiety |

|

|

|

0.207 |

0.088 |

0.019 |

| Pain & dyspnea |

|

|

|

0.170 |

0.090 |

0.060 |

| All 3 symptoms |

|

|

|

0.257 |

0.083 |

0.002 |

| constant |

2.53 |

0.14 |

0.000 |

2.548 |

0.138 |

0.000 |

| Nb obs. |

6,641 |

|

|

6,641 |

|

|

| R-squared |

0.098 |

|

|

0.100 |

|

|

Table A12.

Linear probability models of the rating of the quality of care with added interactions with each combination of symptoms: During the pandemic.

Table A12.

Linear probability models of the rating of the quality of care with added interactions with each combination of symptoms: During the pandemic.

| |

Died during COVID-19 |

Died during COVID-19 |

| |

(1) |

(2) |

| |

Coef. |

Std. Err. |

P>|t| |

Coef. |

Std. Err. |

P>|t| |

| Age |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.025 |

0.005 |

0.002 |

0.021 |

| Female |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.269 |

0.043 |

0.040 |

0.279 |

| Married |

-0.02 |

0.05 |

0.720 |

-0.014 |

0.052 |

0.780 |

| Proxy relationship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non relative |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Spouse |

0.23 |

0.07 |

0.001 |

0.232 |

0.068 |

0.001 |

| Child |

0.09 |

0.05 |

0.097 |

0.088 |

0.054 |

0.102 |

| Relative |

0.23 |

0.08 |

0.003 |

0.232 |

0.078 |

0.003 |

| Telephone interview |

0.00 |

0.05 |

0.942 |

-0.004 |

0.055 |

0.938 |

| Cause of death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cancer |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Cardiovascular disease |

-0.02 |

0.05 |

0.771 |

-0.007 |

0.054 |

0.894 |

| Respiratory diseases |

-0.21 |

0.10 |

0.034 |

-0.207 |

0.099 |

0.037 |

| Digestive system |

-0.05 |

0.10 |

0.638 |

-0.041 |

0.104 |

0.694 |

| Severe infections |

-0.28 |

0.09 |

0.002 |

-0.278 |

0.091 |

0.002 |

| Accident |

-0.08 |

0.20 |

0.702 |

-0.063 |

0.202 |

0.753 |

| Nervous system |

-0.03 |

0.08 |

0.733 |

-0.012 |

0.076 |

0.872 |

| COVID-19 |

-0.29 |

0.07 |

0.000 |

-0.285 |

0.067 |

0.000 |

| Other causes |

-0.14 |

0.09 |

0.115 |

-0.132 |

0.088 |

0.132 |

| Unknown |

-0.26 |

0.12 |

0.025 |

-0.253 |

0.116 |

0.029 |

| Level of education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Low |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Middle |

0.08 |

0.04 |

0.084 |

0.078 |

0.045 |

0.078 |

| High |

0.19 |

0.06 |

0.001 |

0.186 |

0.056 |

0.001 |

| Missing |

-0.09 |

0.26 |

0.720 |

-0.108 |

0.257 |

0.676 |

| Area of residence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Big city or suburbs |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Town |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.278 |

0.056 |

0.050 |

0.262 |

| Rural or village |

0.10 |

0.05 |

0.051 |

0.105 |

0.053 |

0.049 |

| Missing |

0.12 |

0.17 |

0.477 |

0.118 |

0.171 |

0.490 |

| Year of death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2020 |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| 2021 |

-0.02 |

0.04 |

0.567 |

-0.024 |

0.041 |

0.563 |

| 2022 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.615 |

0.030 |

0.062 |

0.629 |

| Wave of interview |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8 (2019–20) |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| 8ca 9ca (2020 & 2021) |

0.04 |

0.10 |

0.711 |

0.032 |

0.100 |

0.754 |

| 9 (2021–22) |

-0.06 |

0.11 |

0.565 |

-0.067 |

0.107 |

0.535 |

| Country distribution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SE |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| DK |

-0.12 |

0.15 |

0.446 |

-0.105 |

0.154 |

0.494 |

| DE |

-0.13 |

0.13 |

0.310 |

-0.128 |

0.132 |

0.331 |

| BE |

0.11 |

0.12 |

0.374 |

0.118 |

0.120 |

0.325 |

| FR |

-0.20 |

0.15 |

0.167 |

-0.198 |

0.146 |

0.174 |

| CH |

-0.03 |

0.15 |

0.828 |

-0.025 |

0.154 |

0.873 |

| AT |

0.25 |

0.11 |

0.028 |

0.259 |

0.114 |

0.024 |

| ES |

0.31 |

0.12 |

0.008 |

0.315 |

0.117 |

0.007 |

| IT |

-0.03 |

0.12 |

0.766 |

-0.029 |

0.116 |

0.802 |

| GR |

0.28 |

0.12 |

0.015 |

0.297 |

0.117 |

0.011 |

| PL |

-0.31 |

0.12 |

0.007 |

-0.285 |

0.116 |

0.014 |

| CZ |

0.14 |

0.11 |

0.212 |

0.151 |

0.112 |

0.177 |

| HU |

0.08 |

0.13 |

0.524 |

0.086 |

0.132 |

0.515 |

| PT |

0.08 |

0.17 |

0.626 |

0.097 |

0.173 |

0.574 |

| SI |

0.25 |

0.12 |

0.030 |

0.265 |

0.118 |

0.025 |

| EE |

-0.48 |

0.11 |

0.000 |

-0.463 |

0.110 |

0.000 |

| IS |

0.27 |

0.13 |

0.045 |

0.282 |

0.135 |

0.036 |

| CR |

0.33 |

0.13 |

0.008 |

0.356 |

0.127 |

0.005 |

| LT |

-0.45 |

0.17 |

0.007 |

-0.423 |

0.166 |

0.011 |

| RO |

-0.21 |

0.13 |

0.110 |

-0.196 |

0.131 |

0.136 |

| PC |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.272 |

-0.071 |

0.125 |

0.572 |

| Symptom profile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No symptoms |

ref |

|

|

ref |

|

|

| Anxiety |

-0.25 |

0.09 |

0.004 |

-0.269 |

0.097 |

0.006 |

| Dyspnea |

-0.004 |

0.07 |

0.953 |

-0.022 |

0.081 |

0.783 |

| Anxiety & dyspnea |

-0.23 |

0.09 |

0.013 |

-0.219 |

0.100 |

0.028 |

| Pain |

-0.07 |

0.07 |

0.300 |

-0.102 |

0.079 |

0.194 |

| Pain & anxiety |

-0.21 |

0.07 |

0.002 |

-0.302 |

0.077 |

0.000 |

| Pain & dyspnea |

-0.04 |

0.07 |

0.557 |

-0.049 |

0.074 |

0.511 |

| All 3 symptoms |

-0.26 |

0.06 |

0.000 |

-0.248 |

0.073 |

0.001 |

| PC and … |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Anxiety |

|

|

|

0.105 |

0.220 |

0.633 |

| Dyspnea |

|

|

|

0.119 |

0.186 |

0.520 |

| Anxiety & dyspnea |

|

|

|

0.034 |

0.225 |

0.879 |

| Pain |

|

|

|

0.156 |

0.163 |

0.341 |

| Pain & anxiety |

|

|

|

0.300 |

0.156 |

0.054 |

| Pain & dyspnea |

|

|

|

0.100 |

0.158 |

0.527 |

| All 3 symptoms |

|

|

|

0.053 |

0.148 |

0.720 |

| constant |

2.46 |

0.26 |

0.000 |

2.451 |

0.261 |

0.000 |

| Nb obs. |

2,596 |

|

|

2,596 |

|

|

| R-squared |

0.117 |

|

|

0.119 |

|

|

Appendix 2. Robustness checks

The robustness checks confirm the results. We only present them for the more simple models where the three symptoms, pain, dyspnea and anxiety are not combined.

Table A21.

Linear probability models of the rating of quality of care with place of death as added control a.

Table A21.

Linear probability models of the rating of quality of care with place of death as added control a.

| |

Pre-pandemic deaths |

Deaths during the pandemic |

| |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

| PC reception |

0.07*** |

0.03 |

-0.006 |

0.05 |

0.06µ |

0.04 |

0.05 |

0.09 |

| Pain |

-0.13*** |

0.03 |

-0.11*** |

0.03 |

-0.03 |

0.04 |

-0.05 |

0.05 |

| Dyspnea |

-0.05* |

0.02 |

-0.08** |

0.03 |

-0.006 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

| Anxiety or sadness |

-0.18*** |

0.02 |

-0.22*** |

0.03 |

-0.20*** |

0.04 |

-0.22*** |

0.05 |

| PC when pain |

|

|

-0.03 |

0.05 |

|

|

0.08 |

0.09 |

| PC when dyspnea |

|

|

0.09** |

0.05 |

|

|

-0.12 µ |

0.08 |

| PC when anxiety or sadness |

|

|

0.11** |

0.05 |

|

|

0.04 |

0.08 |

| Nb obs. |

6,641 |

|

6,641 |

|

2,596 |

|

2,596 |

|

| R2 |

0.108 |

|

0.110 |

|

0.120 |

|

0.121 |

|

Table A22.

Linear probability models of the rating of quality of care with no wave control a.

Table A22.

Linear probability models of the rating of quality of care with no wave control a.

| |

Pre-pandemic deaths |

Deaths during the pandemic |

| |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

| PC reception |

0.04* |

0.03 |

-0.005 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.09 |

| Pain |

-0.13*** |

0.03 |

-0.12*** |

0.03 |

-0.03 |

0.04 |

-0.05 |

0.05 |

| Dyspnea |

-0.05** |

0.02 |

-0.09** |

0.03 |

-0.01 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

| Anxiety or sadness |

-0.18*** |

0.02 |

-0.23*** |

0.03 |

-0.20*** |

0.04 |

-0.22*** |

0.04 |

| PC when pain |

|

|

-0.01 |

0.05 |

|

|

0.10 |

0.09 |

| PC when dyspnea |

|

|

0.10** |

0.05 |

|

|

-0.11 |

0.08 |

| PC when anxiety or sadness |

|

|

0.11** |

0.05 |

|

|

0.05 |

0.08 |

| Nb obs. |

6,641 |

|

6,641 |

|

2,596 |

|

2,596 |

|

| R2 |

0.095 |

|

0.097 |

|

0.114 |

|

0.120 |

|

Table A23.

Linear probability models of the rating of quality of leaving aside Lithuania and Romaniaa.

Table A23.

Linear probability models of the rating of quality of leaving aside Lithuania and Romaniaa.

| |

Pre-pandemic deaths |

Deaths during the pandemic |

| |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

Coeff |

S.E. |

| PC reception |

0.03 |

0.03 |

-0.05 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.04 |

0.05 |

0.09 |

| Pain |

-0.14*** |

0.03 |

-0.12*** |

0.03 |

-0.04 |

0.04 |

-0.06 |

0.05 |

| Dyspnea |

-0.05** |

0.02 |

-0.09** |

0.03 |

-0.01 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

| Anxiety or sadness |

-0.19*** |

0.02 |

-0.23*** |

0.03 |

-0.19*** |

0.04 |

-0.20*** |

0.05 |

| PC when pain |

|

|

-0.02 |

0.05 |

|

|

0.06 |

0.09 |

| PC when dyspnea |

|

|

0.10** |

0.05 |

|

|

-0.13* |

0.08 |

| PC when anxiety or sadness |

|

|

0.11** |

0.05 |

|

|

0.02 |

0.08 |

| Nb obs. |

6,465 |

|

6,465 |

|

2,426 |

|

2,426 |

|

| R2 |

0.095 |

|

0.096 |

|

0.113 |

|

0.115 |

|

Appendix 3. The problem of the change in questionnaire design after wave 7

After wave 7 an additional response item 5 (There was no staff (paid professional) who took care) was added to the question XT765 on the staff ‘s attitude.

XT765_staff (STAFF CARING AND RESPECTFULL)

During [his/ her] last month of life, how often overall was the staff who took care of [him/ her] kind, caring, and respectful? By staff, we mean all professional staff who are paid (by someone) for their services. This includes doctors, nurses, social workers, chaplains, nursing assistants, therapists, and other personnel.

Read out.

More importantly, the question at the center of our study on the rating of care was not asked when there was no paid staff who took care, and the wording of the question “Overall, how would you rate the care the deceased received in [his/ her] last month of life?” was modified accordingly, adding the three words “by the staff” in the generic questionnaire in English:

IF (XT765_staff non equal to 5)

XT766_ratecare (RATE CARE)

Overall, how would you rate the care the deceased received by the staff in [his/ her] last month of life?

Read out...

Excellent.

Very good.

Good.

Fair.

Poor

It should be noted that most countries did not add the three words “by the staff” after wave 7. They kept the former wording (Overall, how would you rate the care received by the deceased during the last month of his/her life?). Only Belgium Wallonia complied. In German speaking Switzerland they translated as “Overall, how would you rate the care and support [he/she] received during the last month of [his/her] life?”.

Hence after wave 7, the question on the rating of care was no more asked in all cases but was skipped for those who said that “no staff (paid professional) took care”. The idea was probably that if no paid professional care was received, the rating was not possible. This intuition did not prove meaningful: for between 4 and 8 percent of the deceased for whom the proxy answered the deceased was not taken care of by any staff, palliative care was nevertheless received (see

Table A31). Hence the necessity as a robustness check not only by controlling for wave as we did in the main paper, but by running the pre-pandemic deaths models separately for wave 7 and for the posterior waves.

The rating of care observed in wave 7 when the question was asked for all deceased clearly confirmed our main pre-pandemic results: PC was effective in fully compensating for the negative effect of anxiety and dyspnea, whether felt separately of simultaneously, and partially compensating their effect when felt in association with pain. PC was not effective when only pain was felt (

Table A32, bold characters). When the question was asked after wave 7 for pre-pandemic deaths, the sigh of the effects were still positive in cases of anxiety or dyspnea but less significant. It was again non-significant for pain, except when felt with dyspnea (

Table A33).

Table A31.

Reception of PC and answer to “whether the staff was caring and respectful in the last month of life” by wave.

Table A31.

Reception of PC and answer to “whether the staff was caring and respectful in the last month of life” by wave.

| PC |

Refusal |

Don’t know |

Always |

Usually |

Sometimes |

Never |

No staff (paid professional) |

Total |

| wave 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

5 |

61 |

1,450 |

325 |

78 |

114 |

|

2,033 |

| % |

83 |

84 |

61 |

57 |

64 |

86 |

|

62 |

| 1 |

1 |

12 |

942 |

245 |

43 |

19 |

|

1,262 |

| % |

17 |

16 |

39 |

43 |

36 |

14 |

|

38 |

| Total |

6 |

73 |

2,392 |

570 |

121 |

133 |

|

3,295 |

| % |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

100 |

| wave 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

1 |

21 |

1,171 |

384 |

96 |

53 |

624 |

2,350 |

| % |

100 |

81 |

60 |

61 |

62 |

80 |

92 |

67 |

| 1 |

0 |

5 |

786 |

242 |

58 |

13 |

54 |

1,158 |

| % |

0 |

19 |

40 |

39 |

38 |

20 |

8 |

33 |

| Total |

1 |

26 |

1,957 |

626 |

154 |

66 |

678 |

3,508 |

| |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| wave 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

1 |

42 |

1,035 |

362 |

94 |

53 |

593 |

2,180 |

| % |

100 |

72 |

67 |

70 |

69 |

90 |

96 |

74 |

| 1 |

0 |

16 |

509 |

156 |

43 |

6 |

26 |

756 |

| % |

0 |

28 |

33 |

30 |

31 |

10 |

4 |

26 |

| Total |

1 |

58 |

1,544 |

518 |

137 |

59 |

619 |

2,936 |

| % |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| waves 8ca-9ca |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

1 |

11 |

382 |

101 |

31 |

9 |

236 |

771 |

| % |

100 |

73 |

68 |

64 |

62 |

75 |

93 |

74 |

| 1 |

0 |

4 |

177 |

57 |

19 |

3 |

18 |

278 |

| % |

0 |

27 |

32 |

36 |

38 |

25 |

7 |

27 |

| Total |

1 |

15 |

559 |

158 |

50 |

12 |

254 |

1,049 |

| % |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Table A32.

Linear probability models of the rating of the quality of care with added interactions with each combination of symptoms: Wave 7 (Pre-pandemic).

Table A32.

Linear probability models of the rating of the quality of care with added interactions with each combination of symptoms: Wave 7 (Pre-pandemic).

| |

Coef. |

Robust Std. Err. |

t |

P>|t| |

Coef. |

Robust Std. Err. |

t |

P>|t| |

| Age |

0.007 |

0.002 |

3.78 |

0.000 |

0.007 |

0.002 |

3.86 |

0.000 |

| Female |

0.039 |

0.035 |

1.11 |

0.268 |

0.039 |

0.035 |

1.11 |

0.267 |

| Married |

0.130 |

0.045 |

2.87 |

0.004 |

0.125 |

0.045 |

2.75 |

0.006 |

| Year death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2016 |

-0.019 |

0.038 |

-0.51 |

0.613 |

-0.014 |

0.038 |

-0.37 |

0.712 |

| 2017 |

0.098 |

0.044 |

2.2 |

0.028 |

0.104 |

0.045 |

2.33 |

0.020 |

| 2018 |

-0.119 |

0.309 |

-0.38 |

0.700 |

-0.111 |

0.309 |

-0.36 |

0.720 |

| Cause |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cardio VD |

-0.134 |

0.044 |

-3.04 |

0.002 |

-0.133 |

0.044 |

-3.01 |

0.003 |

| Respiratory |

-0.130 |

0.078 |

-1.68 |

0.093 |

-0.133 |

0.078 |

-1.7 |

0.089 |

| Digestive |

-0.283 |

0.115 |

-2.47 |

0.014 |

-0.287 |

0.116 |

-2.48 |

0.013 |

| Infection |

-0.345 |

0.078 |

-4.4 |

0.000 |

-0.347 |

0.079 |

-4.4 |

0.000 |

| Accident |

0.196 |

0.241 |

0.81 |

0.416 |

0.210 |

0.239 |

0.88 |

0.378 |

| Nervous |

-0.102 |

0.063 |

-1.62 |

0.104 |

-0.095 |

0.063 |

-1.52 |

0.128 |

| Other |

-0.226 |

0.087 |

-2.6 |

0.009 |

-0.226 |

0.088 |

-2.59 |

0.010 |

| Unknown |

-0.212 |

0.113 |

-1.88 |

0.061 |

-0.208 |

0.113 |

-1.84 |

0.066 |

| Proxy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Spouse |

0.230 |

0.057 |

4.07 |

0.000 |

0.238 |

0.056 |

4.21 |

0.000 |

| Child |

0.179 |

0.048 |

3.73 |

0.000 |

0.179 |

0.048 |

3.74 |

0.000 |

| Relative |

0.091 |

0.071 |

1.28 |

0.199 |

0.096 |

0.071 |

1.35 |

0.177 |

| Telephone |

0.031 |

0.048 |

0.65 |

0.517 |

0.032 |

0.048 |

0.68 |

0.498 |

| Countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SE |

ref |

|

|

|

ref |

|

|

|

| DK |

-0.020 |

0.126 |

-0.16 |

0.873 |

-0.025 |

0.127 |

-0.19 |

0.846 |

| DE |

-0.021 |

0.129 |

-0.16 |

0.869 |

-0.020 |

0.129 |

-0.15 |

0.879 |

| BE |

0.002 |

0.116 |

0.02 |

0.988 |

-0.002 |

0.115 |

-0.02 |

0.983 |

| FR |

-0.064 |

0.119 |

-0.54 |

0.590 |

-0.074 |

0.119 |

-0.62 |

0.534 |

| CH |

0.166 |

0.134 |

1.24 |

0.217 |

0.157 |

0.134 |

1.17 |

0.242 |

| AT |

0.389 |

0.109 |

3.55 |

0.000 |

0.380 |

0.110 |

3.46 |

0.001 |

| ES |

0.262 |

0.104 |

2.53 |

0.012 |

0.263 |

0.104 |

2.53 |

0.012 |

| IT |

-0.012 |

0.114 |

-0.11 |

0.914 |

-0.012 |

0.115 |

-0.1 |

0.920 |

| GR |

0.229 |

0.105 |

2.19 |

0.029 |

0.220 |

0.105 |

2.1 |

0.036 |

| PL |

-0.061 |

0.135 |

-0.45 |

0.650 |

-0.049 |

0.136 |

-0.36 |

0.720 |

| CZ |

0.140 |

0.109 |

1.28 |

0.200 |

0.137 |

0.109 |

1.25 |

0.210 |

| HU |

-0.243 |

0.116 |

-2.11 |

0.035 |

-0.234 |

0.115 |

-2.03 |

0.043 |

| PT |

0.107 |

0.155 |

0.69 |

0.489 |

0.098 |

0.156 |

0.63 |

0.531 |

| SI |

0.196 |

0.122 |

1.6 |

0.109 |

0.184 |

0.122 |

1.51 |

0.131 |

| EE |

-0.244 |

0.108 |

-2.26 |

0.024 |

-0.241 |

0.108 |

-2.24 |

0.025 |

| IS |

0.193 |

0.130 |

1.48 |

0.140 |

0.174 |

0.131 |

1.33 |

0.184 |

| CR |

0.258 |

0.132 |

1.95 |

0.051 |

0.257 |

0.133 |

1.94 |

0.053 |

| Area of living |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Town |

0.048 |

0.041 |

1.17 |

0.240 |

0.047 |

0.041 |

1.15 |

0.250 |

| Village |

0.083 |

0.045 |

1.84 |

0.066 |

0.084 |

0.045 |

1.87 |

0.062 |

| Unknown |

0.260 |

0.139 |

1.87 |

0.061 |

0.260 |

0.136 |

1.91 |

0.057 |

| Education level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Middle |

-0.009 |

0.040 |

-0.22 |

0.826 |

-0.003 |

0.040 |

-0.07 |

0.941 |

| High |

0.142 |

0.055 |

2.6 |

0.009 |

0.144 |

0.055 |

2.62 |

0.009 |

| Unknown |

-0.575 |

0.563 |

-1.02 |

0.307 |

-0.626 |

0.574 |

-1.09 |

0.275 |

| PC |

-0.024 |

0.037 |

-0.64 |

0.520 |

-0.269 |

0.098 |

-2.75 |

0.006 |

| Symptoms profile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No symptoms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Anxiety |

-0.274 |

0.069 |

-4 |

0.000 |

-0.343 |

0.080 |

-4.29 |

0.000 |

| Dyspnea |

-0.100 |

0.069 |

-1.45 |

0.146 |

-0.168 |

0.082 |

-2.05 |

0.040 |

| Anxiety & dyspnea |

-0.262 |

0.080 |

-3.26 |

0.001 |

-0.375 |

0.091 |

-4.11 |

0.000 |

| Pain |

-0.173 |

0.056 |

-3.08 |

0.002 |

-0.159 |

0.065 |

-2.44 |

0.015 |

| Pain & anxiety |

-0.338 |

0.059 |

-5.7 |

0.000 |

-0.379 |

0.076 |

-4.98 |

0.000 |

| Pain & dyspnea |

-0.187 |

0.059 |

-3.19 |

0.001 |

-0.196 |

0.073 |

-2.69 |

0.007 |

| All 3 symptoms |

-0.430 |

0.056 |

-7.74 |

0.000 |

-0.552 |

0.070 |

-7.84 |

0.000 |

| PC and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|