1. Introduction

The study of commuting maps, defined via the usual commutator

, originated with results on automorphisms and derivations. Divinsky proved non-identity commuting automorphisms on rings imply commutativity [

1]. Posner showed centralizing derivations on prime rings are zero [

2]. Brešar characterized commuting maps on prime rings as

, with

in the extended centroid and

mapping to the center [

3,

4,

5]. These extended to semiprime rings and von Neumann algebras [

6]. Further work covered triangular algebras [

7], generalized matrix algebras [

8], and incidence algebras [

9].

Engel-type conditions, like

n-commuting maps where

, were studied in prime and semiprime rings [

10,

11]. Beidar et al. explored functional identities tied to commuting maps [

12,

13,

14].

In superalgebras, supercommuting maps link to Lie superderivations, super biderivations, and Jordan superhomomorphisms [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Recent studies connect to alternative rings and Toeplitz operators [

20,

21]. Ghahramani and Zadeh examined Lie superderivations on unital algebras with idempotents [

22]. Luo and Chen studied supercommuting maps in similar contexts [

23].

Generalizing to superalgebras is important because they model graded structures in physics (e.g., supersymmetry) and quantum mechanics, extending classical algebras to include fermionic and bosonic parts. This allows unified treatment of even and odd elements, relevant in Lie theory and representation theory [

24].

A unital algebra

A with nontrivial idempotent

e (

) has Peirce decomposition

, forming a generalized matrix algebra. The superstructure sets

and

, yielding superderivation results [

22]. For superalgebra basics, see Kac [

24].

Incidence algebras

over locally finite preordered sets

consist of functions

with

if

, under convolution

. Introduced by Ward for arithmetic functions [

25], developed by Rota and Stanley for combinatorics [

26]. Maps on

, like automorphisms and derivations, are well-studied [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. For fundamentals, see Spiegel and O’Donnell [

33].

This paper extends commuting map theory to supercommuting maps on incidence superalgebras. Compared to Brešar [

4] (prime rings), Xiao and Wei [

8] (generalized matrix algebras), and Jia and Xiao [

9] (incidence algebras), our novelty lies in incorporating superstructures, proving all supercommuting maps are proper under a cycle condition on the Hasse diagram. This aligns with superalgebra studies [

22,

23] and generalizes Jia’s results [

9].

2. Preliminaries

Throughout this paper, let R denote a commutative ring with unity that is 2-torsion free and -torsion free. An associative algebra A over R is said to be a superalgebra if it admits a direct sum decomposition into R-submodules such that for . The submodule is called the even part, and is the odd part. Elements in are homogeneous, and the degree of a homogeneous element is denoted by , where if .

For homogeneous elements

, the supercommutator is defined as

This extends linearly to all elements in

A. Note that if either

a or

b is even, then

, the usual commutator. If both are odd, then

, the anticommutator.

The supercenter of

A, denoted

, is the set

It decomposes as

, where

. The usual center

satisfies

.

A linear map

is called supercommuting if

Such a map is proper if it can be expressed as

where

with

, and

is

R-linear. If

for all

x, then

is supercentral. For a unital

A with nontrivial idempotent

e, set

. The Peirce decomposition is

with multiplication rules:

,

, etc., and zero otherwise for incompatible products [

8]. The superstructure is

,

[

22].

Condition (1.1) from [

34] ensures nontriviality: for

, if

then

; similarly for elements in

. Examples include triangular algebras, matrix algebras, and prime algebras with idempotents [

34].

Supercommuting maps satisfy

. Proper forms are

with constraints as above [

17,

19]. Improper maps exist in certain cases, but our main result shows properness under graph-theoretic conditions.

We now introduce standard notations for the incidence algebra

. The unity element

of

is given by

for

, where

is the Kronecker delta. For

with

, let

be defined by

if

, and

otherwise. Then

by the definition of convolution. [

33]. The center

and diagonal subalgebra

play key roles [

33].

The Hasse diagram

has edges for covering relations

(i.e.,

with no

z such that

). Connected components decompose

as a product [

33].

Our contribution extends commuting map theory to supercommuting maps on incidence superalgebras. Assuming every two directed edges in each connected component of the Hasse diagram lie in a cycle, we prove all supercommuting maps on

are proper. This generalizes results on commuting maps of incidence algebras [

9] and aligns with structural studies in associative superalgebras [

22,

23].

Table 1.

Summary of Notations

Table 1.

Summary of Notations

| Notation |

Description |

| R |

Commutative ring with unity, 2-torsion free, -torsion free |

| X |

Locally finite pre-ordered set |

|

Incidence algebra over X and R

|

|

Even and odd parts of superalgebra |

|

Supercommutator:

|

|

Supercenter of A

|

|

Supercommuting map:

|

|

Basis element of

|

|

Unity element of

|

|

Complete Hasse diagram |

| ≈ |

Equivalence on directed edges |

3. The Connected Case

R is a 2-torsion free commutative ring with unity, and

X is a locally finite pre-ordered set, with the complete Hasse diagram

such that any two directed edges in each connected component are contained in one cycle. The incidence algebra

is endowed with a superalgebra structure via a nontrivial idempotent

e, where

is the even part (degree 0) and

is the odd part (degree 1) [

22]. In this section, we study supercommuting maps on

when

X is connected. A map

is supercommuting if

for all

, where

for homogeneous

, extended linearly [

18].

Lemma 1. Let A be an R-algebra with a superalgebra structure , and let θ be a supercommuting map on A. Let satisfy for some integer , where b is an idempotent. Then .

Proof. Case 1. First assume

a is homogeneous, with parity

. Since

is supercommuting, we have

so

Multiplying (

1) on the right by another

a and applying the same identity repeatedly, we obtain by induction

Now compute

But by

,

Since

(mod 2), the exponent in the supercommutator

Hence by simplification, we conclude

By assumption,

is idempotent. The above calculation shows

Case 2. If

a is not homogeneous, write

with

. Expand

as a sum of monomials in

. Each monomial is homogeneous, and the calculation above shows that

supercommutes with each such homogeneous monomial. By linearity, the same holds for their sum. Thus

for general

a, i.e.

. □

Corollary 1. Let A be an R-algebra with a superalgebra structure, and let θ be a supercommuting map on A. If is an idempotent, then .

Proof. Since e is idempotent (), apply Lemma 1 with , , and . Thus, . □

The set

forms an

R-linear basis of

when

X is finite. For

and

, we write

or

for short. Let

be a supercommuting map. We denote

with the convention

if

.

Lemma 2.

The supercommuting map θ satisfies

Proof. Assume

. Since

is idempotent and even (

), by Corollary 1,

. Which yields

Thus,

implies

for

. Left-multiplying by

This gives

if

or

. For

, consider the idempotent

. By Corollary 1,

, so

Multiplying by

on the left and

on the right

Combining,

.

For

, verify that

is idempotent

since

,

,

. By Corollary 1,

, so

Since

(as

or

), which gives

For

,

is idempotent, giving

Multiplying appropriately, we get

if

,

if

, and

if

. Thus

□

Lemma 3. Let X be a connected, locally finite pre-ordered set, and let be a supercommuting map on the incidence algebra , where R is a 2-torsion free commutative ring with unity, and is endowed with a superalgebra structure [22]. Then the coefficients in the expansion are subject to the following relations:

- (R1)

, if ;

- (R2)

, if ;

- (R3)

, if and ;

- (R4)

, for all ;

- (R5)

, if .

Proof. From Lemma 2, we have

Consider the supercommutator relation

for

and any

, derived from the idempotent

(as in Lemma 2). It follows that

Since

(

), and

may have even and odd components, we write

, where

and

. Thus

Now,

Similarly, for

, since

:

Equating, we get

This implies

For : , so .

For : , so .

For : .

Thus, for , set in the first case: , proving (R1). For , set , in the second case: , proving (R2). For , , the third case gives , proving (R3).

For (R5), if , from (R2): , and from (R1): . By (R3), , so .

For (R4), consider

and

with

,

. The element

is idempotent for

. By Lemma 1,

, so

We find , giving . Similarly, for , we get for . For , consider , which satisfies . This yields . For , gives . From , we get . Combining, for all . Since X is connected, for any , there exists a sequence where covers or is covered by . Applying recursively yields , proving (R4). □

Definition 1. For any two directed edges , define if and only if there is a cycle containing both and . The relation ≈ is an equivalence relation on D.

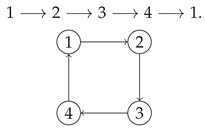

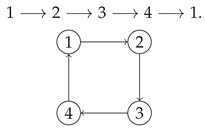

Example 1. Let with partial order relations (or arrows) , , and . The corresponding Hasse diagram is the Dynkin diagram of type , and the associated complete Hasse diagram is depicted in Figure 1.

Thus, , since the directed edges and are contained in the cycle , with , , , .

Proposition 1. Let R be a 2-torsion free commutative ring with unity, and let X be a finite, connected pre-ordered set. Let be endowed with a superalgebra structure via a nontrivial idempotent e [22]. Then every supercommuting map , satisfying for all , is proper if and only if any two directed edges in the complete Hasse diagram are contained in one cycle.

Proof. Assume any two directed edges in

are contained in one cycle, i.e., the equivalence relation ≈ has a single equivalence class. By Lemma 2, for a supercommuting map

, we have:

From Lemma 3, the coefficients satisfy:

- (R1)

, if ;

- (R2)

, if ;

- (R3)

, if , ;

- (R4)

, for all ;

- (R5)

, if .

By (R4),

for all

, so:

Since

(the unity element, with

), we have

, as

for all

f. By (R5),

for all

, since all edges

are in the same equivalence class under ≈. For

, set

. By (R1) and (R2), for any

or

, we adjust coefficients to align with the supercenter.

Define

, where

if

. Then

where

, and

since

for fixed

. Thus,

is proper.

Conversely, if some edges

and

are not in the same cycle, the equivalence classes under ≈ split

D. By [

9], a commuting map may be improper in such cases, and similarly, a supercommuting map may fail to be proper due to inconsistent

across equivalence classes, violating (R5) uniformity.

The proof extends [

9] to the superalgebra context, using the supercenter

[

18]. □

Example 2.

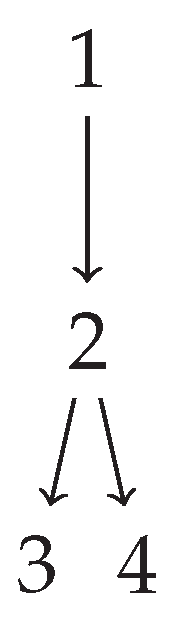

Let with relations , , , and . The Hasse diagram of X is a 4-cycle (a square):

In this case, any two directed edges are contained in a cycle. For instance, via the cycle , and via the same cycle. Thus, the condition of Proposition 1 is satisfied.

4. Supercommuting Maps on Incidence Algebras

Since R be a commutative ring with unity that is 2-torsion free and -torsion free for some positive integer n, and be a locally finite pre-ordered set, possibly infinite, with the incidence algebra endowed with a superalgebra structure via a nontrivial idempotent e, where is the even part (degree 0) and is the odd part (degree 1). The supercommutator is defined as for homogeneous elements , extended linearly. A map is supercommuting if for all .

Definition 2.

Let and . The restriction of f to is defined by

Let be the R-subspace of generated by the elements with . Thus, consists of functions that are nonzero only at a finite number of pairs . The map , defined by , is an algebra homomorphism for any .

Definition 3.

content...For a multilinear map , we define its trace

(or diagonal evaluation) by

Lemma 4.

Let be a supercommuting map on the incidence algebra , where R is -torsion free for some positive integer n. For any and , we have

Proof. Define the map

by

where the polynomial

in noncommutative variables

is defined inductively by

for

. Since

is supercommuting, we have

. Consider the

n-fold supercommutator

where the supercommutator is applied

n times. The trace of

satisfies

Linearizing

, we obtain

where

is the symmetric group on

. Set

and

, where

is the basis element with

and zero elsewhere, and

(since

). Substituting into (

4), we get

Now replace

f with

, where

. Since

is an algebra homomorphism, we apply the same substitution

The second terms in (

5) and (

6) are identical, as they depend only on

and

. Subtracting (

6) from (

5), we obtain

Since

R is

-torsion free, we have

Evaluate at

. For any

, compute the supercommutator with

Since

,

unless

, so

. Iteratively, for

and higher iterates

yield zero at

. Similarly, for the restricted function

However, we need the value of

. Recompute

Instead, use Lemma 2.9 adapted to the superalgebra context. For any

,

Consider

. For

, we need

Apply

to both sides of (

7)

Since

is an algebra homomorphism and

, we evaluate at

because higher supercommutators vanish due to

’s idempotence and degree 0. Similarly

From (

7), since

R is

-torsion free

This completes the proof. □

Theorem 1. Let be a supercommuting map on the incidence algebra , where R is 2-torsion free and -torsion free, and any two directed edges in the complete Hasse diagram are contained in one cycle. Then θ is proper.

Proof. Assume without loss of generality, as the case corresponds to the supercommuting condition . Restrict to , the subalgebra of functions nonzero at finitely many pairs , and denote the restriction by . Since is supercommuting, for all , we have .

By the superalgebra analogue of [

9], adapted to

, if

satisfies

(with

n supercommutators), then

, which is already satisfied since

is supercommuting. By the superalgebra version of [

9] [Theorem 2.5], since

inherits the superalgebra structure and the cycle condition holds,

is proper. Thus, there exists

and an

R-linear map

such that

Since

X is connected and the Hasse diagram satisfies the cycle condition, the supercenter

consists of diagonal functions constant on connected components, and for a connected

X,

(analogous to [

33]). Thus, we may take

.

Define

by

We need to show that

is central-valued, i.e.,

for all

. For

, we have

since

. For any

and

, by Lemma 4, we have

Thus,

since

, and elements in the supercenter are diagonal (i.e., zero off the diagonal). Hence,

for all

, so

is diagonal

Next, we prove that

for all

, ensuring

. Since

X is connected, it suffices to show

for

. Consider the map

where

,

, and

. Since

is supercommuting,

. Linearizing

, we get

Replace

with

, since

and

supercommutes with

f. Set

,

, and

. Then

since terms with

involve

, which is diagonal. This simplifies to

as

appears once with

permutations. Since

R is

-torsion free, we have

We find

Since

is diagonal and even (

), and

, we get

Higher supercommutators with

(even), yield

Thus,

Since

X is connected,

for some

, so

Hence,

, and

is proper. The cycle condition ensures consistency of coefficients, as in [

9]. □

Example 3.

Let , which is -torsion free for all , and let with the natural order . The incidence algebra has -basis

where denotes the characteristic function of .

Choose the idempotent . Then the induced -grading is

Define by

That is, is obtained by doubling f and then adding a diagonal function whose entries are all equal to the trace .

Claim. θ is a supercommuting map and hence proper.

Proof. For

write

where . Since is diagonal with constant diagonal entries, we have . As clearly supercommutes with f, and central elements also supercommute, it follows that

Thus θ is supercommuting. By Theorem 1, θ is proper, with and μ central-valued. □

5. The General Case

In this section, we study supercommuting maps on the incidence algebra

in the general case, i.e., without assuming connectedness of

X. Let

R be a commutative ring with unity that is

-torsion free, and let

be endowed with a superalgebra structure via a nontrivial idempotent

e, with even part

and odd part

. The supercommutator is defined as

for homogeneous elements

, extended linearly. For a positive integer

n, we define the super-

n-center of an

R-algebra

A as follows:

where

, and

for

. Clearly,

, the supercenter of

A.

Lemma 5.

Let be the family of connected components of a locally finite pre-ordered set X, and let be the incidence algebra over a commutative ring R that is -torsion free, endowed with a superalgebra structure. Let θ be a supercommuting map on , i.e., for all . Then, for each , there exists a unique supercommuting map on and a unique map such that the restriction of θ on satisfies:

Proof. Since

X is a locally finite pre-ordered set, its connected components

partition

X, and the incidence algebra decomposes as

, where each

is a subalgebra with the induced superalgebra structure. For each

, let

be the canonical projection onto

, and let

be the canonical projection onto the complementary subalgebra. Define

Clearly,

, and this decomposition is unique since

and

project onto complementary subspaces.

For any

, since

is supercommuting, we have

Write

, where

and

. Since

, we have

for any

with

, as

only if

. Thus

since

. Hence

This shows that

is a supercommuting map on

.

Next, we show that

. Define the map

by

where

,

, and

for

. Since

is supercommuting,

. For

n-fold supercommuting, we assume

. Linearizing this condition gives

Let

and

for some

. Then

Since

,

, and

, we have

. We find

because

, so

. The second term involves

, but we focus on the first term

Since

R is

-torsion free, we get

Thus,

, as

has support only in

. This completes the proof. □

Proposition 2. Let be a family of -torsion free R-algebras, each endowed with a superalgebra structure. If for all , then every n-supercommuting map on , satisfying for all , is proper if and only if every n-supercommuting map on is proper for all .

Proof. Let be an n-supercommuting map on , i.e., for all . By the superalgebra analogue of Lemma 5, for each , the restriction , where is an n-supercommuting map, and is an R-linear map.

Sufficiency: Assume every

n-supercommuting map on

is proper for all

. Then, for each

, there exist

and an

R-linear map

such that

for all

. Define the

R-linear map

by

where

with

. Define

for all

. We need to show that

. Since

is

n-supercommuting, we have the linearized condition

where

and

. Set

and

for some

. This gives

Compute

,

Since

, we have

For

, evaluate

Since

and

, for

, we have

because

has no component in

. Thus

Now,

Since

, we have

because

. Thus,

Hence,

Since

R is

-torsion free and

for all

, we have

Thus,

. However, since

and

, we must have

. Therefore

This implies

Since

and

, we can define

, where

. Thus:

where

and

is

R-linear. Hence,

is proper.

Necessity: Suppose there exists some

such that not every

n-supercommuting map on

is proper. Then there exists an

n-supercommuting map

that is improper. Construct a map

by

where

for the given

i, and for

,

is a proper

n-supercommuting map, say

for some

. For

, compute

since

for

. Since each

is

n-supercommuting,

, so

is

n-supercommuting. However,

is improper, so

cannot be proper, as its restriction to

is

. This completes the proof. □

Theorem 2. Let R be a commutative ring with unity that is 2-torsion free and -torsion free for some positive integer n. Let X be a locally finite pre-ordered set with connected components , and let be the incidence algebra endowed with a superalgebra structure via a nontrivial idempotent e. If any two directed edges in each connected component of the complete Hasse diagram are contained in one cycle, then every supercommuting map is proper.

Proof. Since X is a locally finite pre-ordered set, its incidence algebra decomposes as , where each is a subalgebra with the induced superalgebra structure via e. By Lemma 5, for a supercommuting map on , the restriction to is , where is supercommuting, and .

Since each

satisfies the cycle condition (any two directed edges are in one cycle), by Theorem 1, every supercommuting map

on

is proper. Thus, there exist

and an

R-linear map

such that

Since

R is

-torsion free, Lemma 5 implies

. For incidence algebras, the super-

n-center

coincides with supercenter

, as elements in

must supercommute with all basis elements

up to the

n-th supercommutator, which forces them to be diagonal and constant on connected components, as shown in [

33].

From the proof of Proposition 2, since

, we have

for all

, because

. Thus

For any

, define

Since

for

, we have

Since

, we have

, and

is

R-linear. Thus,

is proper, completing the proof. □

Example 4.

Let and equip X with the pre-order generated by the directed m-cycle

The transitive closure of these relations gives for every pair , so every pair of vertices is comparable (in both directions). Hence

is the full matrix algebra (identify f with the matrix ).

Choose the nontrivial idempotent (the matrix unit). The induced superalgebra grading is

The (super-)center of is the scalar matrices,

Now apply Theorem 2. The cycle condition (any two directed edges lie in one cycle) is obviously satisfied here (the single cycle contains all edges). Therefore every supercommuting map is proper: there exist and an R-linear map such thatRemark.

conversely, not every map of the form is automatically supercommuting (extra graded constraints may further restrict ). The theorem asserts: if θ does

supercommute, then it must be of the above form.

Example 5.

Let where forms a directed 3-cycle and forms a directed 4-cycle. As in Example 4, taking the transitive closure on each makes every pair inside comparable. Hence,

Denote

The superalgebra structure is induced by the same fixed nontrivial idempotent e, which splits each block according to the matrix decomposition.

Let be a supercommuting map. By Lemma 5, we may write, for ,

where is supercommuting and

takes values in the super-n-center of the other component. In our matrix-algebra components, we have (scalar matrices for each block). Hence, each is a scalar matrix in the other block.

We now show that . Fix i and take and arbitrary. Linearizing the n-fold supercommuting identity (as in the proof of Proposition 2) yields a relation whose first summand equals

Because R is -torsion free, this implies

However, is a scalar matrix sitting in the other

summand (), so it has zero support on . Therefore, the only possibility consistent with the identity and with disjoint supports is that is the zero scalar. Hence, for both .

Consequently,

(no cross terms), and by Theorem 1, each is proper on its block. Putting this together, we obtain

where and are R-linear. Equivalently, for any ,

Thus, θ is proper on . This verifies Theorem 2 in this concrete two-component situation.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we have advanced the theory of commuting maps on incidence algebras [

9] by introducing and characterizing supercommuting maps in the context of superalgebra structures, as developed by Ghahramani and Heidari Zadeh [

22]. Our primary result demonstrates that, under the graph-theoretic condition that any two directed edges in each connected component of the complete Hasse diagram

lie within a single cycle, every supercommuting map on the incidence algebra

, where

R is a 2-torsion free and

-torsion free commutative ring with unity is proper. This extends classical results on commuting maps in prime rings, triangular algebras, and generalized matrix algebras [

4,

7,

8] to the superalgebra setting, utilizing the Peirce decomposition induced by a nontrivial idempotent to separate even and odd components.

The proofs hinge on foundational lemmas that delineate the form of supercommuting maps on basis elements (Lemmas 2 and 3) and their behavior under restrictions to connected components (Lemma 5). The culminating theorems (Theorems 1 and 2) offer a precise description: such maps take the form , with in the supercenter and an R-linear map into .

Looking ahead, several avenues merit exploration. One could investigate supercommuting maps on broader classes of algebraic structures, including generalized matrix algebras or triangular algebras equipped with supergradings, or delve into functional identities and multilinear maps within superalgebras [

6]. Furthermore, weakening the cycle condition, examining cases where improper supercommuting maps arise, or extending the framework to infinite pre-ordered sets without local finiteness could uncover novel phenomena and classifications.

To guide new researchers, we propose the following specific open problems:

Characterize improper supercommuting maps on incidence algebras when the cycle condition is violated. For instance, construct explicit examples of improper maps on posets where the Hasse diagram has multiple equivalence classes under the relation ≈ from Definition 1.

Extend the results to incidence algebras over non-commutative rings R or rings that are not -torsion free. What adjustments are needed to the proper form in such cases?

Investigate higher-order supercommuting maps, where the condition is for . Can analogs of Theorems 1 and 2 be established, and what role does the super-k-center play?

Explore applications of supercommuting maps to combinatorial structures, such as poset cohomology or Möbius inversion in superalgebras. For example, how do supercommuting automorphisms affect the Möbius function in incidence algebras with supergrading?

Study supercommuting maps on variants of incidence algebras, such as reduced incidence algebras or those arising from categories. Does the cycle condition generalize to categorical Hasse diagrams?

References

- Divinsky, N. On commuting automorphisms of rings. Trans. Roy. Soc. Canada. Sect. 1955, 3, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, E.C. Derivations in prime rings. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1957, 8, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brešar, M. Centralizing mappings on von Neumann algebras. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1991, 111, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brešar, M. Centralizing mappings and derivations in prime rings. J. Algebra 1993, 156, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brešar, M. Commuting traces of biadditive mappings, commutativity-preserving mappings and Lie mappings. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1993, 335, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brešar, M. Commuting maps: a survey. Taiwanese J. Math. 2004, 8, 361–397. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, W.S. Commuting maps of triangular algebras. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 2001, 63, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wei, F. Commuting mappings of generalized matrix algebras. Linear Algebra Appl. 2010, 433(11–12), 2178–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Xiao, Z. Commuting maps on certain incidence algebras. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 2020, 46, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukman, J. Commuting and centralizing mappings in prime rings. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1990, 109, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brešar, M. On generalized biderivations and related maps. J. Algebra 1995, 172, 764–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beidar, K.I.; Brešar, M. Extended Jacobson density theorem for rings with derivations and automorphisms. Isr. J. Math. 2001, 122, 317–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beidar, K.I.; Brešar, M.; Chebotar, M.A. Jordan superhomomorphisms. Commun. Algebra 2003, 31, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beidar, K.I.; Chen, T.S.; Fong, Y.; Ke, W.F. On graded polynomial identities with an antiautomorphism. J. Algebra 2002, 256, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Dai, X. Super-biderivations of Lie superalgebras. Linear Multilinear Algebra 2017, 65, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Sun, J. Super-biderivations and linear super-commuting maps on the super-BMS3 algebra. São Paulo J. Math. Sci. 2019, 13, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Wang, Y. Supercentralizing maps in prime superalgebras. Commun. Algebra 2009, 37, 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. On skew-supercommuting maps in superalgebras. Bull. Aust. Math. Soc. 2008, 78, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Supercentralizing automorphisms on prime superalgebras. Taiwanese J. Math. 2009, 13, 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.L.M.; Kaygorodov, I. Commuting maps on alternative rings. Ricerche Mat. 2022, 71, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q. Commuting Toeplitz operators and H-Toeplitz operators on Bergman space. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 2530–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, H.; Heidari Zadeh, L. Lie superderivations on unital algebras with idempotents. Commun. Algebra 2024, 52, 4853–4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, Y. Supercommuting maps on unital algebras with idempotents. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 24636–24653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kac, V.G. Lie superalgebras. Adv. Math. 1977, 26, 8–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M. Arithmetic functions on rings. Ann. Math. 1937, 38, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, R.P. Enumerative Combinatorics, Volume 1, 2nd ed.; Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baclawski, K. Automorphisms and derivations of incidence algebras. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1972, 36, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, E. Automorphisms of incidence algebras. Commun. Algebra 1993, 21, 2973–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppinen, M. Automorphisms and higher derivations of incidence algebras. J. Algebra 1995, 174, 698–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddeeque, M.A.; Alam, M.S.; Bhat, R.A. (ζ1, ζ2)-derivations of incidence algebras. Asian-Eur. J. Math. 2025, 18, 2550079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddeeque, M.A.; Bhat, R.A.; Alam, M.S. Characterization of mixed triple derivations on incidence algebras. Filomat 2025, 39, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Khrypchenko, M. Lie derivations of incidence algebras. Linear Algebra Appl. 2017, 513, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, E.; O’Donnell, C.J. Incidence Algebras; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Benkovič, D. Lie triple derivations of unital algebras with idempotents. Linear Multilinear Algebra 2015, 63, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).