1. Introduction

The current Lithuanian territory was a kind of a crossroad during the ages [

1] and experienced many perturbations starting from the arrival of the first hunter-gatherers after the last glacial period. It witnessed many sociodemographic processes that are reflected in the contemporary population. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is important not only in cellular organismal functions and all four disease groups [

2], forensic science [

3], but also as evidence for maternal ancestry and population history [

4]. Population migration before and after the last glacial maximum, both to and from refuges in Central, Southwestern, and Southern Europe, has influenced the current European gene pool [

5]. Population mtDNA studies have expanded from Hypervariable Region I (HVRI) and/or II (HVRII) to the determination of the entire mtDNA sequence [

4] in the analysis of population genetic structure and its similarities (or differences) to other populations [

4,

6]. Tracing mtDNA variation change across time and space can help in recreating some of the migration, admixture, and/or social practices. There were previous attempts to characterise the contemporary Lithuanian population using mtDNA markers. Kasperavičiūtė D. and others [

7] examined the mtDNA HVRI region of 180 individuals from the Lithuanian population. There were 76 variable regions and 95 different haplotypes defined. The genetic diversity and average pairwise differences identified were close to the estimates for other European populations, while the Lithuanian population itself was found to be homogeneous, close to Slavic (Russia, Poland) populations, and aligned between the Finno-Ugric populations of Northern Europe (Estonia, Finland) and the Indo-European populations of Western Europe. The most common haplogroups characteristic of European populations accounted for 97% of the Lithuanian population studied [

7]. Based on the distribution of mtDNA haplogroups, Kushniarevich A. and others showed that the Lithuanian population falls in the same cluster as the Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, and Belarusian populations, whereas Estonian, Czech, Slovak, and Balkan populations remain distant from the Eastern European population group [

8]. Uktverytė I., in her doctoral thesis, analysed 267 complete sequences of mtDNA from the modern-day Lithuanian population and confirmed previously shown Lithuanian population clustering between Slavs and Middle/Near East populations [

9]. The interpopulation genetic difference between West and East ethnolinguistic groups of the Lithuanian population was found and explained by the distribution of the two main (H and U) and the other (A, HV, I, J, K, M, N, T, V, W) phylogenetic lineages. The phylogenetic lineage U was suggested to be dominant in the first inhabitants of the modern-day territory of Lithuania and then replaced by newcomers who carried the phylogenetic lineage H [

9].

Compared to the systematic modern-day Lithuanian population mtDNA studies, ancient material analyses from the territory of modern-day Lithuania were sparse. Initial findings [

10] on the study of mtDNA of four Stone Age individuals from the territory of modern-day Lithuania confirm previous suggestions about the first people in the territory of Lithuania having haplogroup U lineage: the study found one individual representing U4 and three individuals U5 haplotypes [

11,

12,

13]. The limited number of analysed individuals is indicative of the rarity and poor preservation state of the Stone Age materials from the territory of modern-day Lithuania. Due to cremation practices in the region, the preservation of material suitable for genetic analysis is no better in the Bronze Age. Thus, we reinitiated further mtDNA study on 132 Iron Age (IA) samples to fill the knowledge gap regarding the structure and spatial-temporal variation of maternal ancestry in modern-day Lithuania. We compared the diversity and variation of mtDNA haplogroups in the IA (represented as Roman, Migration, and Viking periods) and the modern-day samples, at the same time contributing with previously unpublished 279 mtDNA complete sequences for the modern-day Lithuanian population, as well as mtDNA HVRI genotypes of 36 loci of 101 IA individuals from the territory of modern-day Lithuania. Our analysis showed a variation in the diversity of haplogroups over time (with the presence of the most exotic L4b2, B2m, and B4 haplotypes in the IA and a wide spectrum of regional-like haplogroups in the modern-day Lithuanian population), with a stable prevalence of H and U as major haplogroups through the IA and modern times in the territory of modern-day Lithuania.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Iron Age Sample Group

A total of 132 individuals from the IA were sampled for the study. The selection of individuals was determined by the state of preservation and their potential to provide a balanced representation of both region and period. At least two teeth from each individual were selected for research. The chosen teeth showed minimal to no dental wear and did not have any carious lesions that could potentially impact the results. Therefore, the preference was for all teeth available with minimal damage.

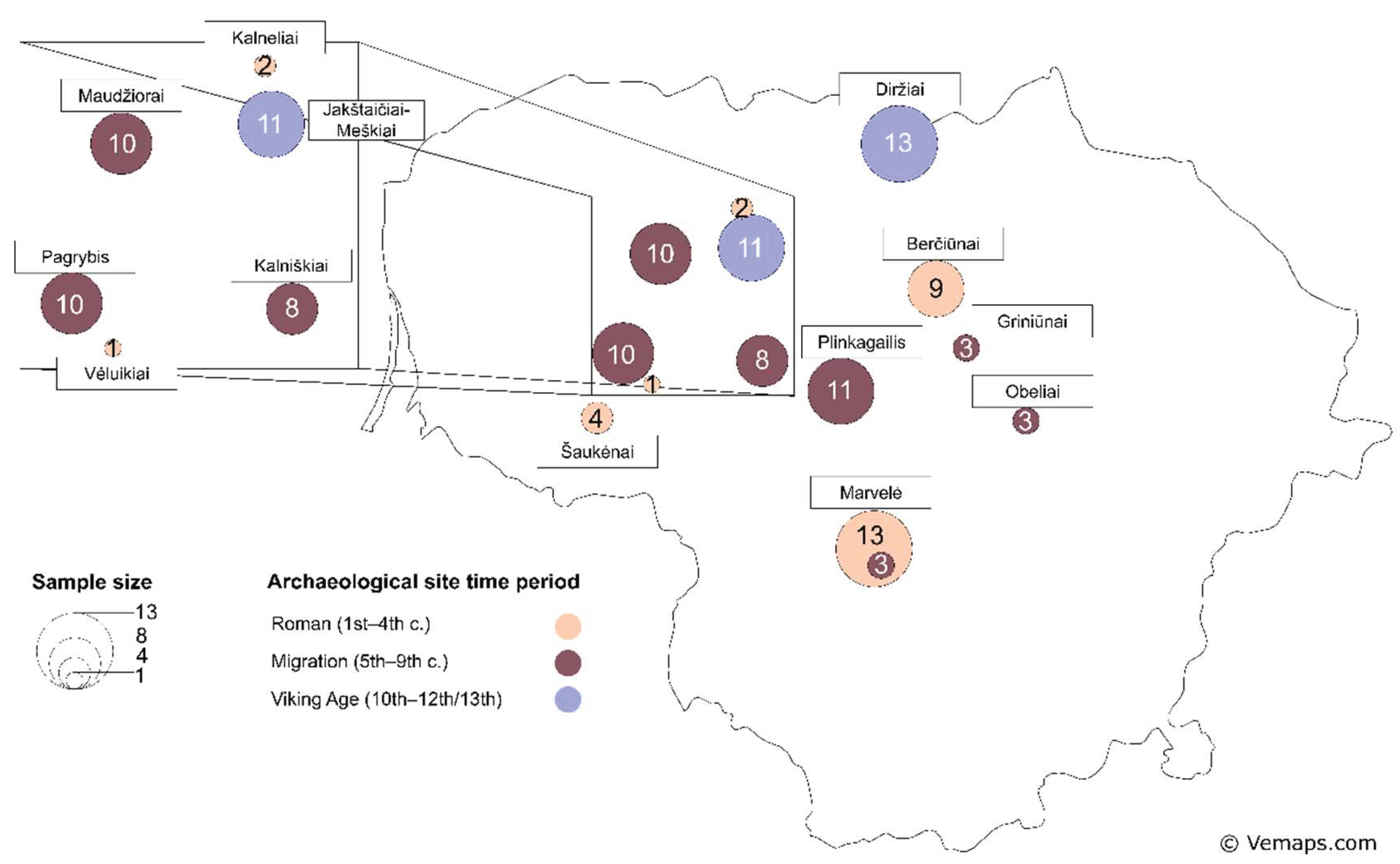

The selected individuals originate from the present-day Lithuania’s western, central, and northern regions and represent different chronological phases (

Figure 1). Although the southern and eastern regions are not included in this study, the spatial and temporal coverage of the sampled material can broadly represent this research. The three key historical phases – the Roman, Migration, and Viking Ages – were selected as each contributing distinctive ways to developing social organization, technological innovation, and cultural exchange processes whose impact remains evident in today’s European history. Considering some differences in these three time periods, especially burial traditions and social stratification, the individuals selected for this study did not stand out in the archaeological general context.

The sex and age at death of the individuals were determined using standard methods outlined by Buikstra and Ubelaker (1994) [

14]. Sex was assessed based on the morphology of the skull and pelvis. For non-adults, age was evaluated based on dental and overall skeletal development, while for adults, the primary method used was the examination of the pubic symphysis, when available [

15,

16]. Other skeletal indicators for aging included the changes of the sternal end of the ribs, the auricular surface of the pelvic bone, general degenerative changes in the skeleton, including the closure of skull sutures, and dental wear [

17,

18,

19]. The individuals were grouped into three age categories: young adults (18–34 years), middle adults (35–49 years), and older adults (≥50 years). Some overlaps between age groups and age categories were noted, i.e., individuals who fell within the 30–39 years age range were interpreted as “middle adult”, for skeletal maturity was already reached [

20] (

Table S1 in

Supplementary Materials).

mtDNA was extracted and genotyped according to the protocols described previously in Witas et al. [

21].

2.2. Modern-Day Lithuanian Sample Group

The modern-day Lithuanian sample group consisted of 279 unrelated individuals’ samples throughout Lithuania. Individuals reported at least three generations of Lithuanian descent. Thus, we address this modern-day sample group as the group of the general Lithuanian population.

Venous blood samples (and DNA extracts) were collected in 1994–1995 and during the LITGEN project (VP1-3.1-ŠMM-07-K-01-013) in 2011–2013.

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood using either a phenol–chloroform extraction method or an automated nucleic acid purification protocol following manufacturers’ guidelines (Freedom EVO® Nucleic Acid Purification Workstation, PROMEGA kit “MagneSil® Genomic, Large Volume System”). The quality and quantity of purified genomic DNA were evaluated spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop® ND-1000 Spectrophotometer).

Multiplex sequencing on the Illumina GAII platform after in-solution capture enrichment was used to obtain complete mtDNA genome sequences with an average of 352-fold coverage depth (at the Department of Evolutionary Genetics, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig, Germany)).

To perform the analysis of this sample group, ethical approval from the Vilnius Regional Research Ethics Committee was obtained (No. 158200-05-329-79, date: 2011-05-03).

The dataset of complete mtDNA sequences from the modern-day Lithuanian population is deposited in the NCBI SRA database, accession number... Accession numbers will be provided during review upon acceptance of the publication.

2.3. MtDNA Data Analysis Methods

This study used 36 loci in the mtDNA HVRI (within the range of 16126–16320). MtDNA HVRI positions were aligned relative to the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS) (NC_012920) [

22] (

Table S2 in

Supplementary Materials).

For the modern-day Lithuanian sample group, complete mtDNA sequences were generated with the nf-core/eager pipeline (v2.5.2) [

23]. FASTQ files were pre-processed by removing adapters and bases with quality lower than 20 and reads shorter than 30 bp using AdapterRemoval (v2.3.2). DNA sequences were aligned to rCRS using the BWA-MEM algorithm (v0.7.17-r1188). Duplicated sequences were removed using DeDup (v0.12.8). The variants were called using GATK UnifiedGenotyper (v3.5-0-g36282e4), and consensus FASTA sequences were generated via VCF2Genome (v0.91). The complete sequences were used to assign haplotypes. For further phylogenetic and population genetic analyses, modern-day Lithuanian mtDNA data were reduced to the aforementioned 36 loci in HVRI for adequate comparison with the IA mtDNA data.

2.3.1. Haplotype Classification

Haplotypes were assigned using HaploGrep 2 with the PhyloTree v17 Forensic Update 1.0 [

24]. MtDNA HVRI 36 loci and complete mtDNA sequences were used for haplotype classification of ancient and modern-day Lithuanian samples, respectively. Haplogroups of IA samples are provided in

Tables S2 and S3 and haplotypes of modern-day samples in

Table S4 in

Supplementary Materials.

2.3.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (v4.4.2) [

25]. A

p-value less than 0.05 indicates a statistically significant result.

Haplogroup distribution pie charts were created using the R package ggplot2 (v3.5.1). Fisher’s exact test with 10,000 replicates from the R package stats (v4.4.2) was used to compare haplogroup distribution spatially and temporally.

2.3.3. Phylogenetic and Population Genetic Analyses

The temporal change of Lithuanian population mtDNA diversity across the three IA periods and modern times in Lithuania was further explored through phylogenetic and genetic variation analysis.

Median-joining networks [

26] were performed and visualized using PopART (v1.7) with default parameters [

27].

For genetic differentiation, we estimated pairwise Fixation index (F

ST) [

28] (bootstrap 1,000, 95% CI) using the StAMPP R package (v1.6.3).

For further population differentiation analyses, pairwise Hamming distances between samples were calculated using the ape R package (v5.8.1). Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) was used to assess inter- and intra-population genetic diversity [

29]. AMOVA with 10,000 permutations was performed using the pegas R package (v1.3). Classical Multidimensional-scaling (MDS) [

30] based on pairwise differences was constructed using R packages stats and ggplot2.

A comparative analysis with other European populations was performed by assembling a dataset from publicly available data [

31,

32], the NCBI database [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], and the 1000 Genomes Project [

41]. The used data and the references are described in

Table 1. The acquired data were reduced to the aforementioned 36 loci in HVRI for adequate comparison with the IA mtDNA data. The comparative dataset was used for F

ST and MDS analyses.

3. Results

After data quality control, 101 out of 132 sampled IA individuals from archaeological sites in the territory of modern-day Lithuania were used.

3.1. Haplogroup Distribution

The 101 mtDNA samples from IA from the territory of modern-day Lithuania (the range of 16126–16320 relative to rCRS) were classified into 34 haplotypes and 9 haplogroups using Haplogrep 2 [

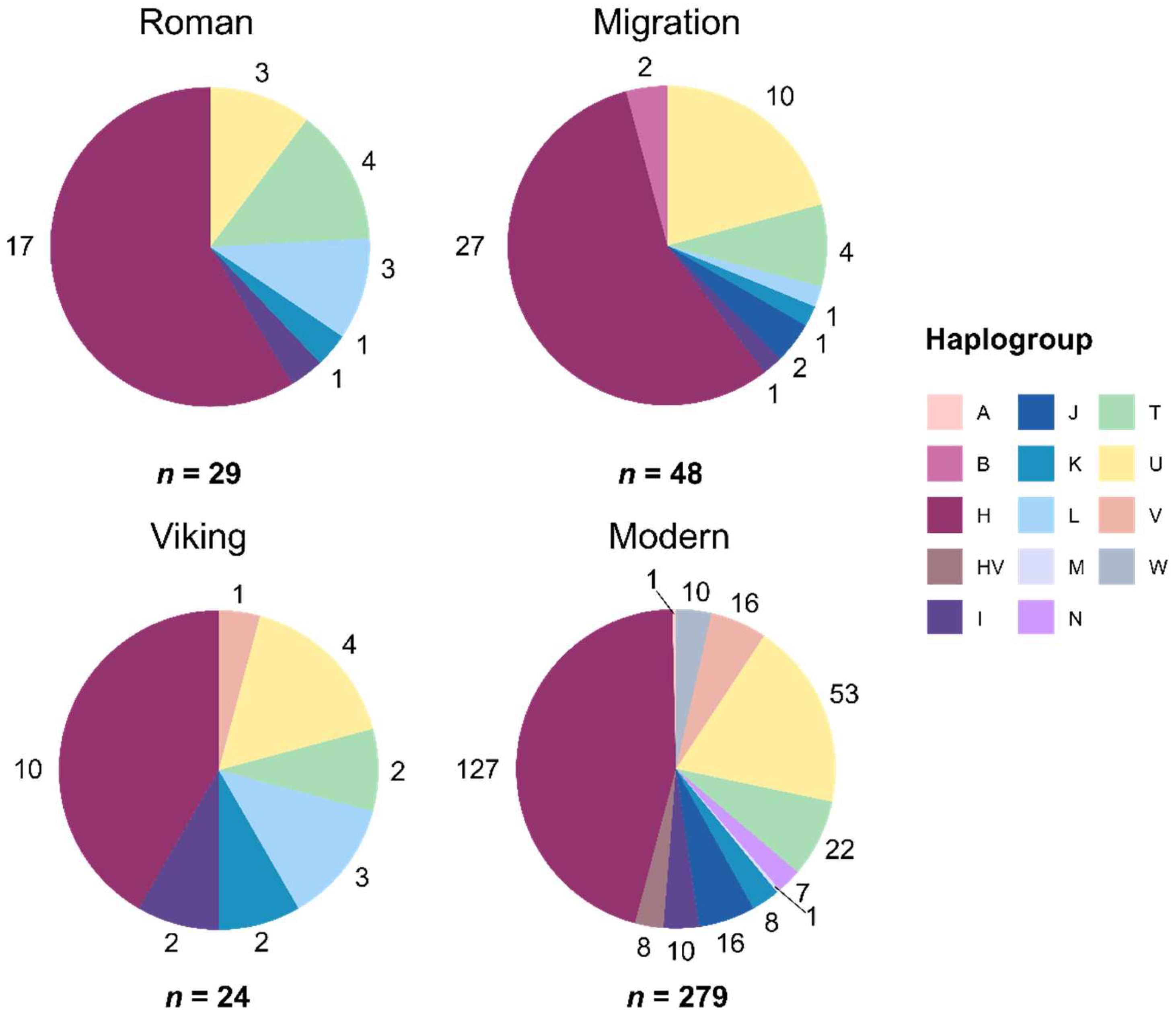

24]. For the modern-day Lithuanian population, the complete mitogenome data from 279 samples were classified into 142 haplotypes and 12 haplogroup phylogenetic lineages. Haplogroup H was the most frequent in the three IA periods – Roman (59%), Migration (56%), and Viking (42%) – and in the modern-day Lithuanian population (46%) (

Figure 2). Haplogroup U is the second most frequent in the Migration, Viking, and modern-day Lithuanian groups (17–21%). In the Roman period sample group, haplogroup T was the second most frequent (14%). Differences in 14 haplogroup frequencies between all four time periods were significant (Fisher’s exact test with 10,000 replicates,

p = 0.01).

We compared the haplotype distribution of the most diverse haplogroups H and U among the IA and modern-day groups. Haplogroup H had the greatest variety of haplotypes (15 in the IA group, 41 in the modern-day Lithuanian group; 54 overall, including overlapping haplotypes). Haplogroup U was the second most diverse (6 haplotypes in the IA group, 27 in the modern-day Lithuanian group; 31 overall including overlapping haplotypes).

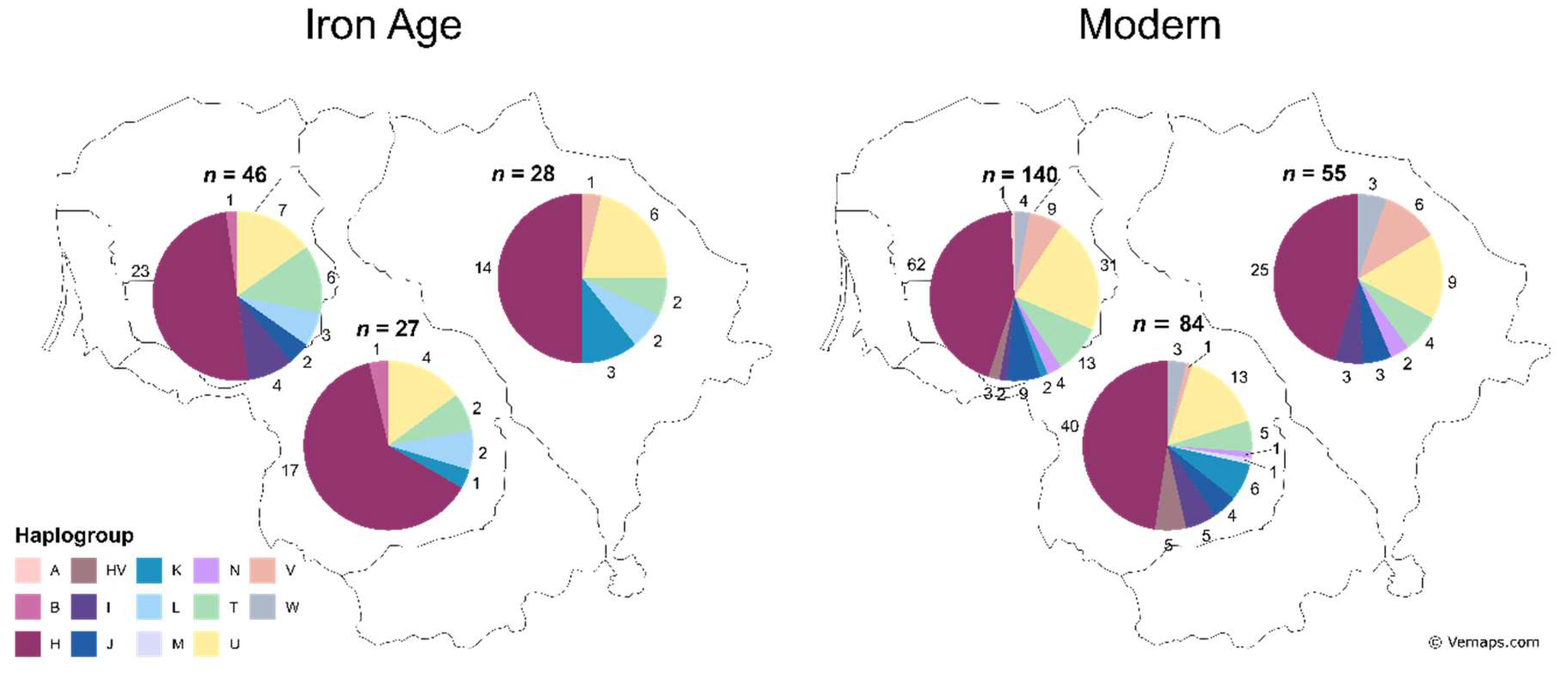

To check the temporal mtDNA haplogroup variation association with space, we divided the IA period and modern-day Lithuanian population samples by their geographic location into Western (Žemaitija), Central (Western and Southern Aukštaitija), and Eastern (Eastern Aukštaitija) regions. IA samples from the Western region had the highest diversity of haplogroups overall (7 vs. 6) and haplogroups I and J were absent in the Central and Eastern parts. The Central region had the highest frequency of haplogroup H (63% vs. 50%). The Eastern region had the highest frequency of haplogroup U (21% vs. 15%) (

Figure 3). Modern-day samples from the Western and Central regions had the highest diversity of haplogroups overall (11 vs. 8). Fisher’s exact test (10,000 replicates) revealed no significant difference between haplogroup distributions between geographic regions in IA or modern-day Lithuanian population samples (

p > 0.05).

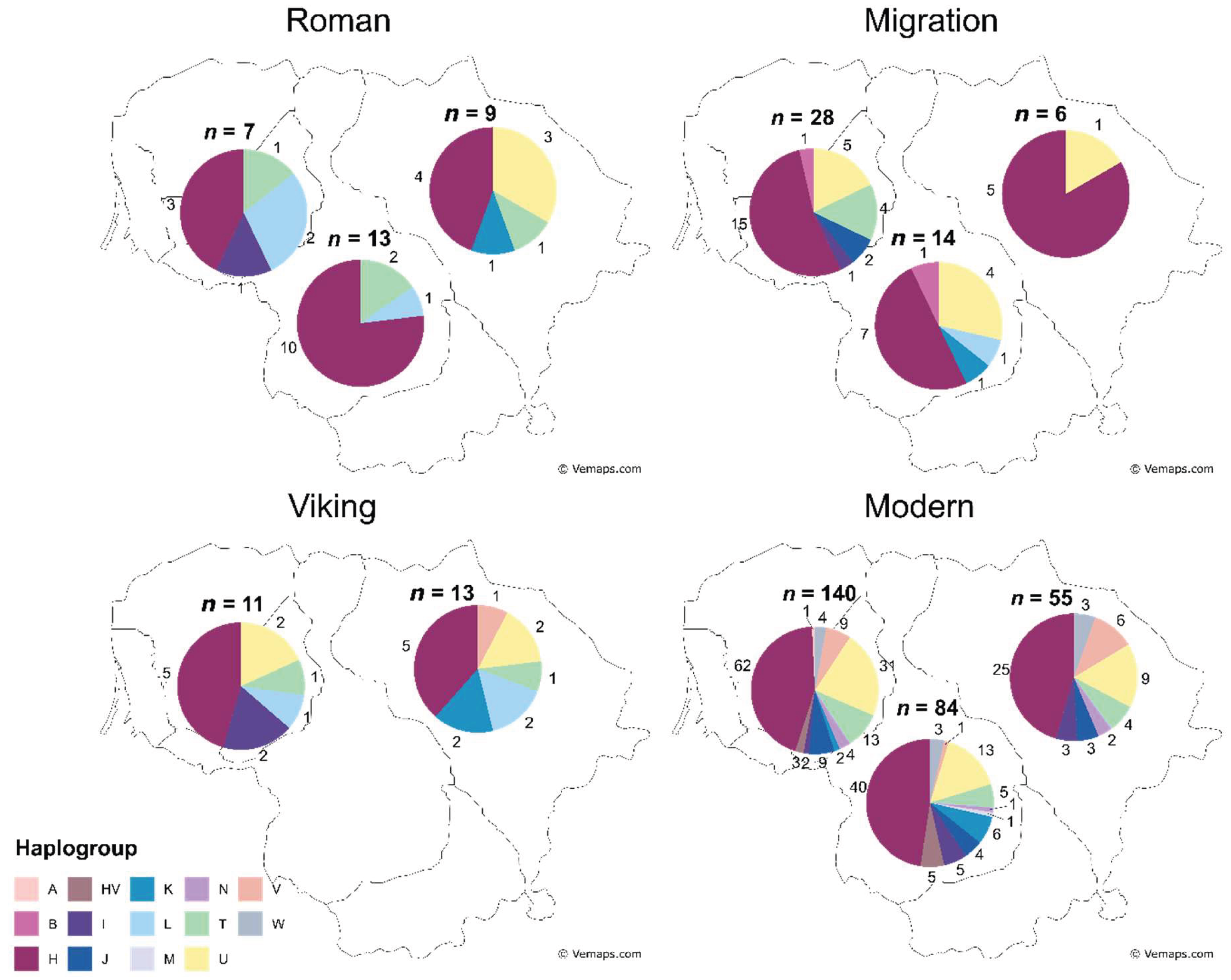

To examine the exact period during which haplogroup diversity increased, we looked at haplogroup frequency change in Western, Central, and Eastern Lithuania across three IA periods (

Figure 4). Fisher’s exact test (10,000 replicates) revealed no significant differences in haplogroup distributions across geographic regions during the Roman, Migration, or Viking periods (

p > 0.05).

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

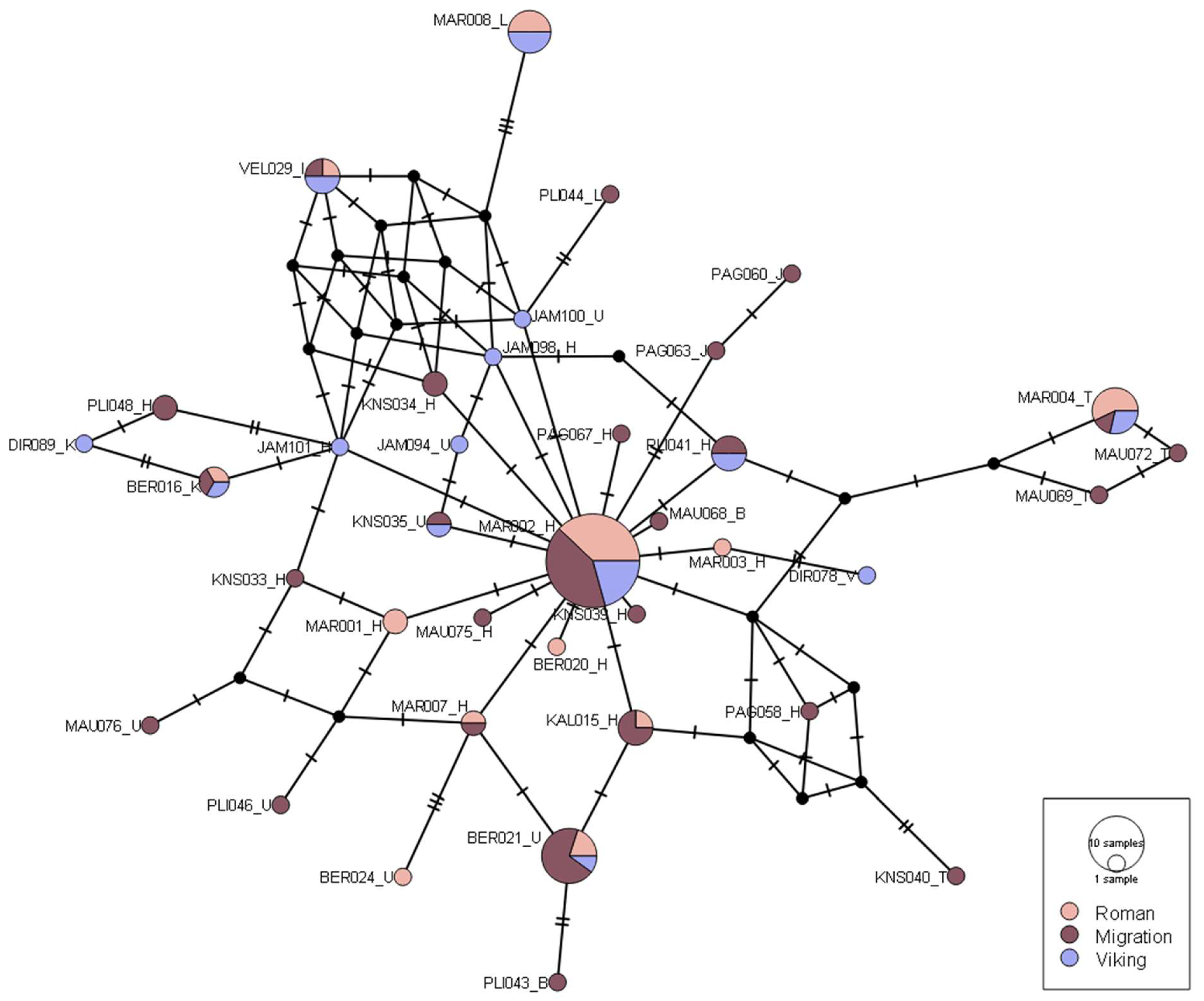

Phylogenetic analysis of IA mtDNA was carried out to examine variation distribution among samples and across the Roman, Migration, and Viking periods (

Figure 5). Most of the IA samples are identical and classified as H haplogroup (H2a2a1) (

Table S2 in

Supplementary Materials). Haplotype network displays higher mtDNA diversity among the Migration and Viking period samples. The divergence of the haplotypes of samples from the Roman and Viking periods suggests a change in mtDNA variation in the IA. The Viking period samples tend to deviate from the Roman or Migration periods. The Migration period haplotype visualization in both star-like, square, and crisscrossing shapes implies higher mtDNA diversity (

Figure S3 in

Supplementary Materials).

3.3. Population Genetic Analysis

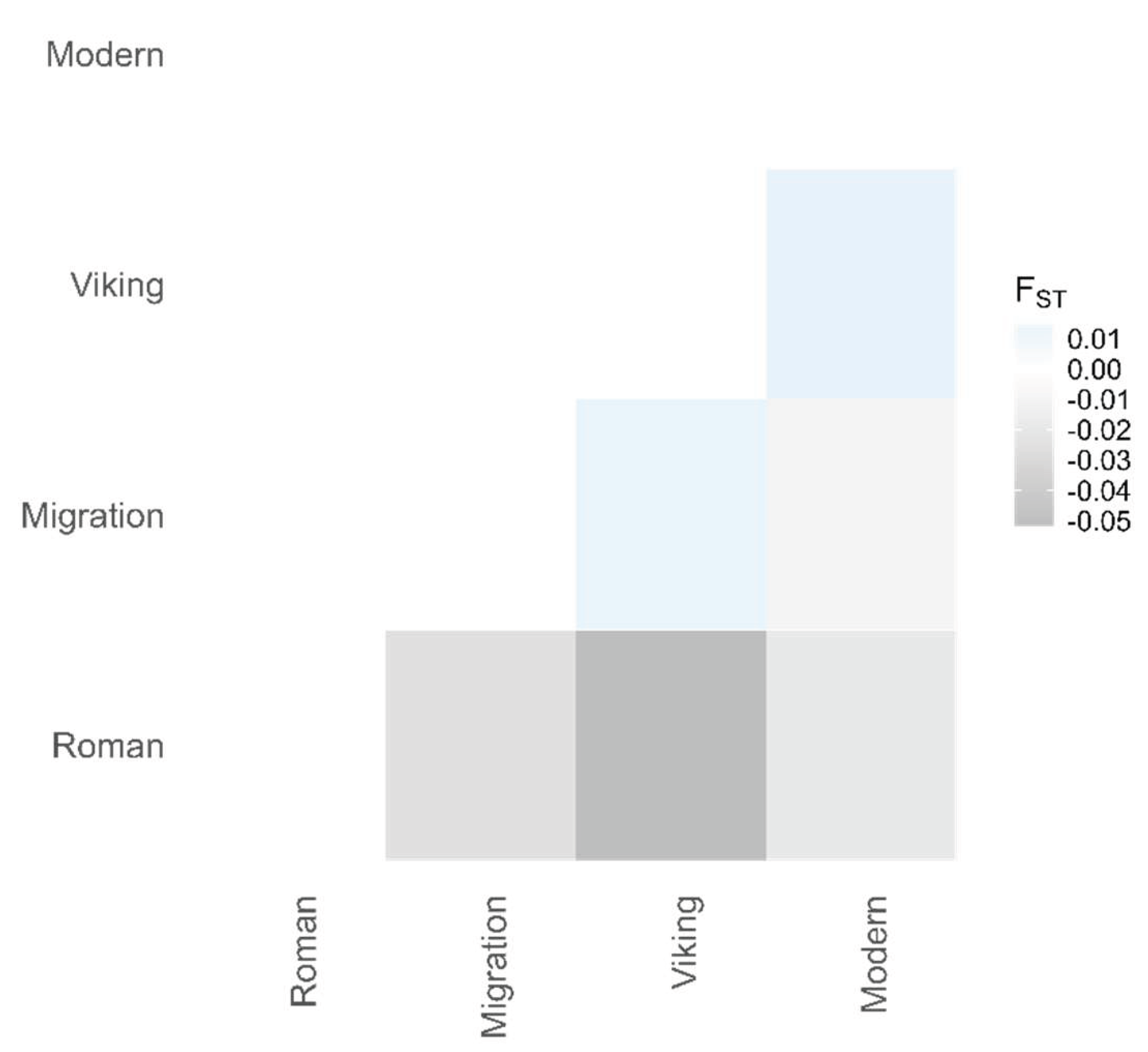

The pairwise F

ST between the Roman, Migration, Viking, and Modern-day Lithuanian population groups revealed no significant differentiation in between different time periods (

p > 0.05 between all pairs). We observed low genetic differentiation between the Migration and Viking sample groups (F

ST = 0.016) and between the Viking and Modern Lithuanian populations (F

ST = 0.015) and no genetic differentiation between the Roman group and the other groups, as well as between the Migration group and the modern-day Lithuanian population (F

ST < 0) (

Figure 6). Similarly, low differentiation was detected by including the modern European population data, with F

ST values remaining below 0.1 (

Table S7 in

Supplementary Materials). However, the 36 loci were able to differentiate an outgroup African population (Yoruba, Nigeria) from European populations, including the Lithuanian IA, with F

ST values ranging from 0.26 (Roman group) to 0.36 (Bosnia and Herzegovina), and the differences were statistically significant (

p < 0.05 for all populations).

For the following genetic analyses, we calculated hamming/pairwise distances using 36 loci from the HVRI region of mtDNA (range 16126–1320).

We carried out AMOVA to assess the genetic variation proportion (

Table 2). Most of the genetic variation is determined within populations (96–99%). There were statistically significant differences found between Iron Age groups and Iron Age groups vs modern-day Lithuanian population (

p < 0.05).

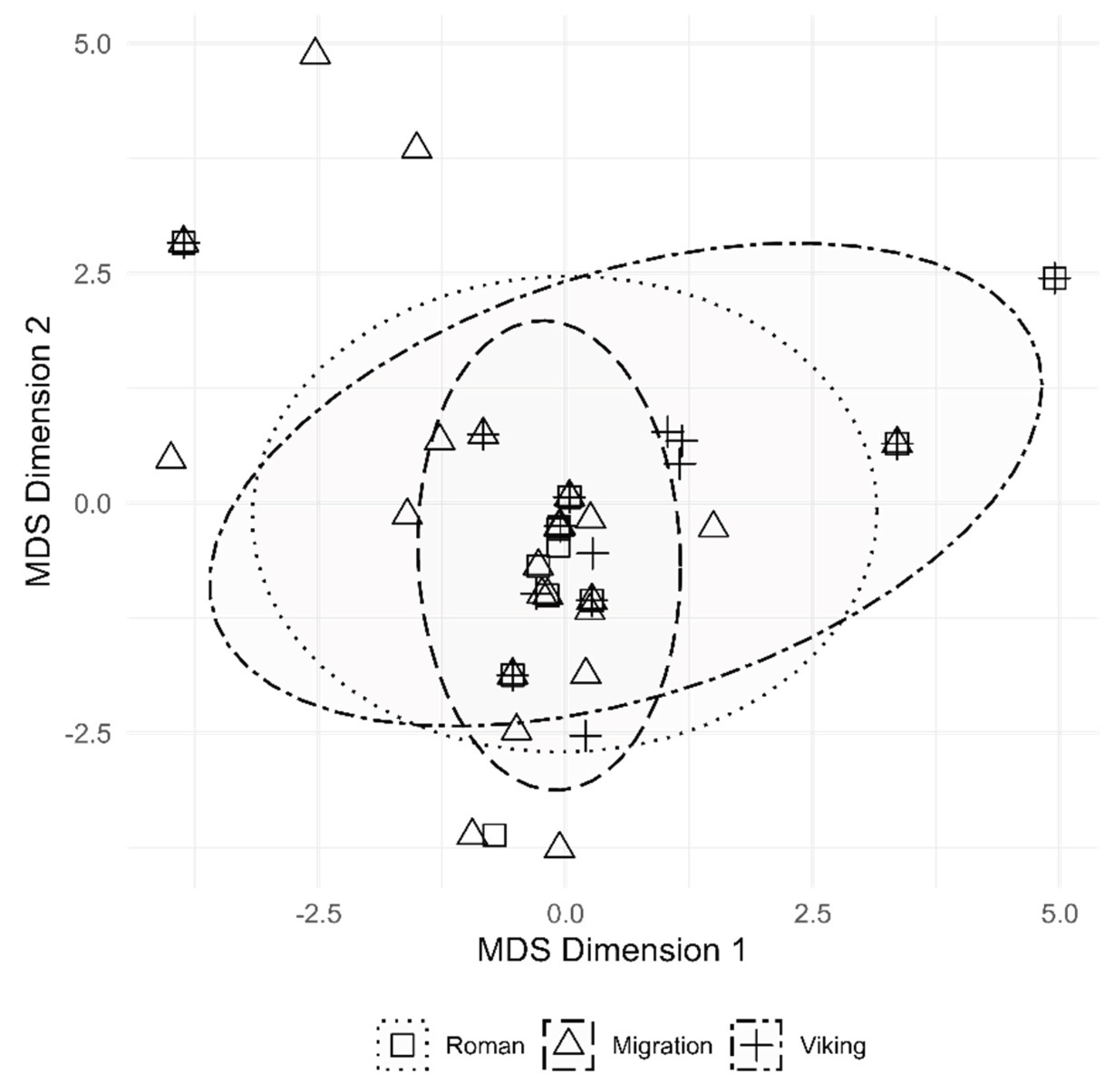

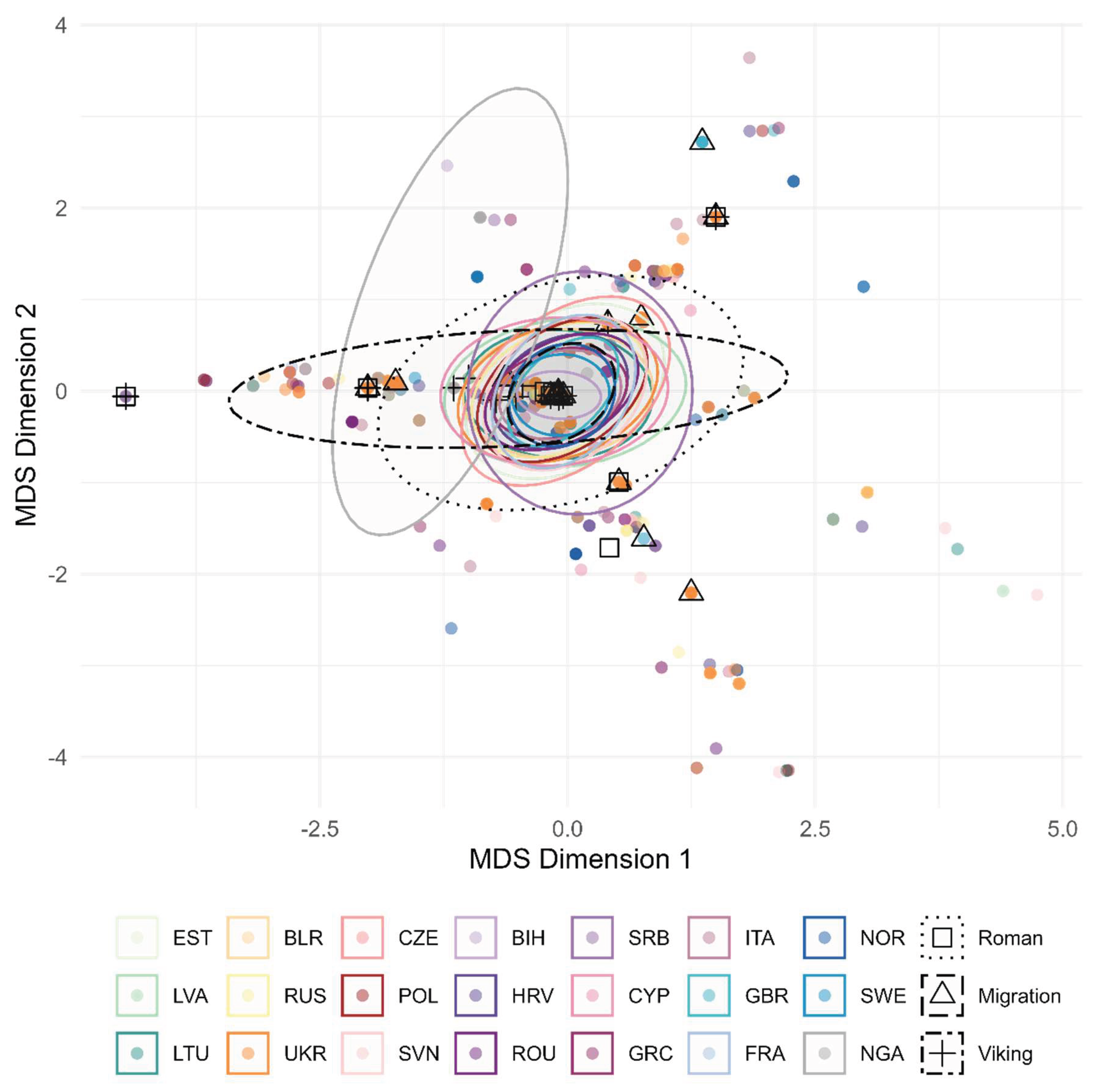

We implemented MDS to discern mtDNA nucleotide diversity in the Lithuanian region populations during the IA. We generated MDS with 95% confidence ellipses to visualize the dispersion of the data in each group (

Figure 7). Data points outside the confidence intervals are the samples classified into haplogroups L, T, B, and haplotype U5a1.

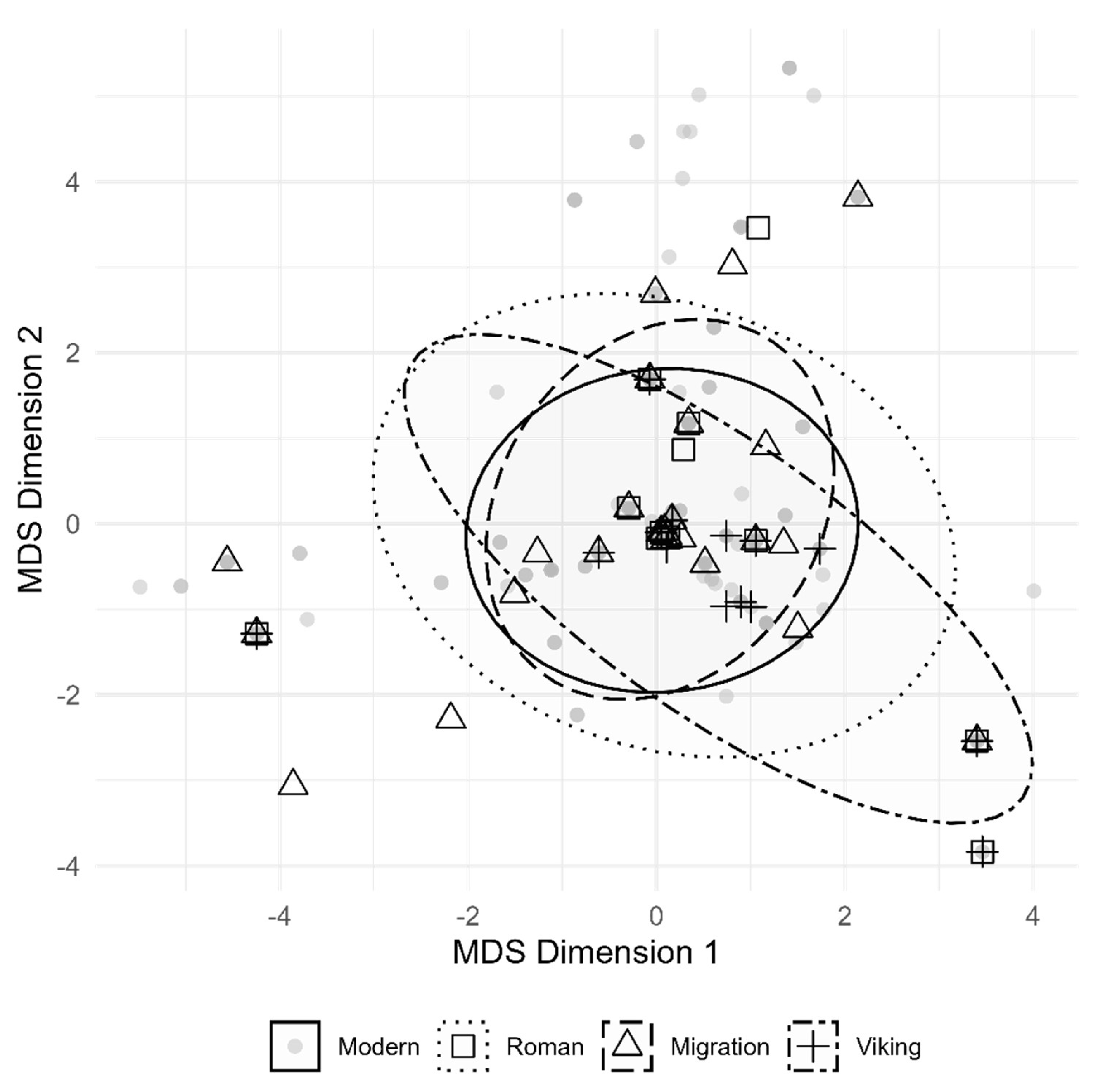

The inclusion of modern-day Lithuanian population group reveals mtDNA loci diversity similarity to the Migration group (

Figure 8). The overlap of confidence ellipses and sample projection along the first dimension implies comparable mtDNA diversity patterns during the Migration period and today. Multiple outliers in the modern-day Lithuanian population indicate higher mtDNA diversity introduced into the Lithuanian population through the maternal lineage since the IA.

We projected the analysed mtDNA loci of other modern-day European populations on the MDS plot for further study of the mtDNA diversity of the IA population group from the modern-day territory of Lithuania (

Figure 9). The Migration period mtDNA diversity followed a similar pattern to modern-day European population mtDNA diversity, whereas the Roman and Viking period mtDNA diversity overlapped. Moreover, the Viking group MDS projection exhibits higher genetic diversity than the other Lithuanian IA groups or modern-day European populations.

4. Discussion

Modern-day Lithuanian population’s mtDNA was extensively studied using different techniques and methods. However, ancient material mtDNA studies from modern-day Lithuanian territory were fragmented, and started with the oldest material from the Stone Age [

11]. It was shown that the major mtDNA haplogroup lineage was U (Spiginas4, Kretuonas1, 2, and 3). But another study complemented with the Stone and Bronze Age individual mtDNA data from the territory of modern-day Lithuania by showing the H haplogroup presence, in addition to K, I, W, and T [

12]. Our results show dominance of the H haplogroup during the IA, with the highest frequency in the Roman period (59%) and 46% in modern-day Lithuania (Fisher’s exact test with 10,000 replicates,

p > 0.05). This aligns with the results of previous findings of recent admixture of Western Hunter-Gatherers and Eastern Hunter-Gatherers with the haplogroup H presence before arrival of the Neolithic farmers [

12]. Our study suggests that in the territory of the present-day Lithuania, the H haplogroup influx could have appeared during the Late Bronze Age and the Early IA.

Haplogroup phylogenetic lineage U is the second most common in all groups, except for the Roman period, with the highest frequency in the Migration period (21%). In the Roman period, haplogroup U was found to be the third most common (11%) after the T haplogroup being the second most common in the Roman period (14%). Haplogroup T is the third most common in the Migration group and modern-day Lithuanian population, and it is the fourth most common in the Viking period (8%). Haplogroup L was the third most common haplogroup in the Roman (10%) and Viking (13%) periods, and its frequency was found to be lower in the Migration period (2%). Most of the individuals with the L haplogroup phylogenetic lineage belong to the non-African L3 haplogroup; meanwhile the L4b2 haplotype was assigned for the PLI044 individual from Plinkaigalis (Central Lithuania), dated to the Migration period (5th–6th c. CE). The haplotype L4b2 is old and of African origin [

42]. The presence of haplogroup L in the territory of modern-day Lithuania in our IA samples is a unique finding, as it was not reported, to our knowledge, contemporaneously elsewhere in the Baltic region. Interestingly, in the samples dated to the Migration period, we observed another two haplotypes, B4 and B2m, which are not ordinary to the region analysed and indicate Asian ancestry [

43]. Despite atypical haplogroups L4 and B, the burial customs of these individuals were not exceptional rather analogous to those of other individuals from the same archaeological sites. The unexpected findings of haplogroups L and B could be showing a random movement of people during the Migration period through the territory of modern-day Lithuania.

K and I haplogroup distribution were similar in frequency and remained stable from the IA till today (2–3%), except for the increase during the Viking period (8%). J haplogroup, found only in the Migration period (4%) over the IA group and at moderate frequency (6%) in the modern-day Lithuanian population. Similarly, the V haplogroup was found only in the Viking period (4%) and in the modern-day Lithuanian population (6%). Haplogroups A (0.4%), HV (3%), N (3%), and W (4%) are at low frequencies in the modern-day Lithuanians and are unidentified in the IA samples.

The mtDNA haplogroup distribution pattern in different regions of the modern-day Lithuania reveals a consistent increase in diversity since the Migration period (except for the Eastern region, regarding a small sample size), showing constant admixture over time. Since the IA, the mtDNA structure of the population in the territory of the modern-day Lithuania marginally changed, as indicated by 3.7% of genetic variation between the Roman, Migration, and Viking periods (p = 0.04).

Dimension reduction into two dimensions revealed no sample clustering, indicating continuity of mtDNA diversity in the IA Lithuania. Nevertheless, MDS reveals a slightly distinct distribution of the Migration period samples. In contrast to the Roman and Viking groups, the Migration group’s mtDNA loci variation is explained by the second dimension. Tighter confidence ellipses representing the Migration group are possibly attributed to the larger sample size (48 vs. 24 and 29). MDS revealed that the Roman, Migration, and Viking periods’ mtDNA diversity in the territory of modern-day Lithuania followed a similar pattern to today’s European population mtDNA diversity, which corresponds with other studies [

44,

45].

Despite the universal problem regarding the sparse (and in a way accidental/opportunistic/random) ancient samples representation of the periods and populations [

46,

47], there might be some other limitations regarding this study. First of all, the determination of the H2a2a1 haplotype might be affected by rCRS reference bias. We performed haplotype assignment based on the 36 loci within the HVRI (16126–16320), and we cannot exclude the possibility that genotyping of additional loci would allow for a more precise haplotype assignment. However, the HVRI (as well as HVRII) is hypervariable and contains more variation than other parts of the mtDNA and is suitable for recent genetic variation structure analysis.

Also, the Viking period sample group does not include samples representing the central Lithuanian territory, which might have affected the result of the haplogroup diversity and distribution of the period.

To obtain finer-scale genetic data for further analysis, considering new technologies and possibilities, additionally, we plan to perform next-generation sequencing to retrieve as much data as possible from the same amount of the sample. Moreover, we plan to continue studying temporal genetic structure change in the Lithuanian region by expanding the sample size and including further time periods.

Overall, it seems that looking at the variation of mitogenomes over time, genetic structure in the individuals of the territory of modern-day Lithuania experienced some random fluctuations and gained more diversity but remained stable with the dominance of haplogroups of H and U phylogenetic maternal lineages, which falls into the context of the European landscape.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Haplogroup distribution of the Iron Age and modern-day Lithuanian samples. Figure S2: Haplotype network of the Roman period samples. Figure S3: Haplotype network of the Migration period samples. Figure S4: Haplotype network of the Viking period samples. Table S1: Information and archaeological context of the Iron Age individuals. Table S2: The Iron Age individual mtDNA HVR1 positions relative to the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS). Table S3: Haplogrep 2 report of mtDNA data from Iron Age Lithuanian samples. Table S4: Haplogrep 2 report of mtDNA data from modern Lithuanian samples. Table S5: Temporal distribution of the Iron Age and Modern Lithuanian sample mtDNA haplogroup frequencies. Table S6: Temporal and spatial distribution of the Iron Age and Modern Lithuanian sample mtDNA haplogroup frequencies. Table S7: FST distances between the Iron Age and Modern Lithuanian and Modern European sample groups. Table S8: Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) with 10,000 permutations between the Iron Age and Modern Lithuanian groups. Table S9: Data and sources used in this study.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, I.D.; methodology, I.D., I.Kr., I. Ka., and H.W.; formal analysis, I.D. and I.Kr.; investigation, H.W., I.Ka., and I.Kr.; resources, H.W., I.Ka., V.K.; data curation, J.K., R.J., I.Ka, V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D., I.Kr, and J.K.; writing—review and editing, I.D., I.Kr., J.K., I.Ka, V.K. and R.J.; visualization, I.Kr.; supervision, V.K. and R.J.; project administration, I.Ka, V.K. and R.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

In addition to the supplementary material (including the dataset of the Iron Age individuals from modern-day Lithuania mtDNA HVRI genotypes of 36 loci), here we provide a new complete mtDNA sequences dataset of 279 individuals from the modern-day Lithuanian population.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to the dr. Mark Stoneking group members at the Department of Evolutionary Genetics, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig, Germany) for providing infrastructure and guidance during the sequencing of mtDNA of modern Lithuanian population.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BIH |

Modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| BLR |

Modern-day Belarus |

| CYP |

Modern-day Cyprus |

| CZE |

Modern-day Czech |

| EST |

Modern-day Estonia |

| FRA |

Modern-day France |

| FST

|

Fixation index |

| GBR |

Modern-day England |

| GRC |

Modern-day Greece |

| HRV |

Modern-day Croatia |

| HVRI |

Hypervariable Region I of mtDNA |

| HVRII |

Hypervariable Region II of mtDNA |

| IA |

Iron Age |

| ITA |

Modern-day Italy |

| LTU |

Modern-day Lithuania |

| LVA |

Modern-day Latvia |

| MDS |

Multi-dimensional scaling |

| mtDNA |

Mitochondrial DNA |

| NGA |

Modern-day Nigeria |

| NOR |

Modern-day Norway |

| POL |

Modern-day Poland |

| rCRS |

Cambridge Reference Sequence |

| ROU |

Modern-day Romania |

| RUS |

Modern-day Russia |

| SRB |

Modern-day Serbia |

| SVN |

Modern-day Slovenia |

| SWE |

Modern-day Sweden |

| UKR |

Modern-day Ukraine |

References

- Kudirka, J. The Lithuanians: An Ethnic Portrait; Lithuanian Folk Culture Center, 1991;

- Shokolenko, I.; Alexeyev, M. Mitochondrial DNA: Consensuses and Controversies. DNA 2022, 2, 131–148. [CrossRef]

- Syndercombe Court, D. Mitochondrial DNA in Forensic Use. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences 2021, 5, 415–426. [CrossRef]

- Kivisild, T. Maternal Ancestry and Population History from Whole Mitochondrial Genomes. Invest Genet 2015, 6, 3. [CrossRef]

- Pala, M.; Olivieri, A.; Achilli, A.; Accetturo, M.; Metspalu, E.; Reidla, M.; Tamm, E.; Karmin, M.; Reisberg, T.; Kashani, B.H.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA Signals of Late Glacial Recolonization of Europe from Near Eastern Refugia. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2012, 90, 915–924. [CrossRef]

- Schönberg, A.; Theunert, C.; Li, M.; Stoneking, M.; Nasidze, I. High-Throughput Sequencing of Complete Human mtDNA Genomes from the Caucasus and West Asia: High Diversity and Demographic Inferences. Eur J Hum Genet 2011, 19, 988–994. [CrossRef]

- Kasperavičiūtė, D.; Kučinskas, V.; Stoneking, M. Y Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Lithuanians. Annals of Human Genetics 2004, 68, 438–452. [CrossRef]

- Kushniarevich, A.; Sivitskaya, L.; Danilenko, N.; Novogrodskii, T.; Tsybovsky, I.; Kiseleva, A.; Kotova, S.; Chaubey, G.; Metspalu, E.; Sahakyan, H.; et al. Uniparental Genetic Heritage of Belarusians: Encounter of Rare Middle Eastern Matrilineages with a Central European Mitochondrial DNA Pool. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66499. [CrossRef]

- Uktverytė, I. LIETUVOS ETNOLINGVISTINIŲ GRUPIŲ GENETINĖS STRUKTŪROS ANALIZĖ REMIANTIS INFORMATYVIAIS GENOMO ŽYMENIMIS, 2014.

- Bramanti, B.; Thomas, M.G.; Haak, W.; Unterlaender, M.; Jores, P.; Tambets, K.; Antanaitis-Jacobs, I.; Haidle, M.N.; Jankauskas, R.; Kind, C.-J.; et al. Genetic Discontinuity Between Local Hunter-Gatherers and Central Europe’s First Farmers. Science 2009, 326, 137–140. [CrossRef]

- Jankauskas, R. Ancient Mitochondrial DNA from Stone Age Lithuania and the Possible Origins of the First Inhabitants. At the Origins of the Culture of the Balts 2011, 32–36.

- Mittnik, A.; Wang, C.-C.; Pfrengle, S.; Daubaras, M.; Zariņa, G.; Hallgren, F.; Allmäe, R.; Khartanovich, V.; Moiseyev, V.; Tõrv, M.; et al. The Genetic Prehistory of the Baltic Sea Region. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 442. [CrossRef]

- Posth, C.; Yu, H.; Ghalichi, A.; Rougier, H.; Crevecoeur, I.; Huang, Y.; Ringbauer, H.; Rohrlach, A.B.; Nägele, K.; Villalba-Mouco, V.; et al. Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic to Neolithic European Hunter-Gatherers. Nature 2023, 615, 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Buikstra, J.E.; Ubelaker, D.H. Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 44 1994.

- Schaefer, M.; Scheuer, L.; Black, S.M. Juvenile Osteology: A Laboratory and Field Manual; Elsevier/Academic Press: Amsterdam ; Burlington, MA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-12-374635-1.

- Brooks, S.; Suchey, J.M. Skeletal Age Determination Based on the Os Pubis: A Comparison of the Acsádi-Nemeskéri and Suchey-Brooks Methods. Hum. Evol. 1990, 5, 227–238. [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, C.O.; Meindl, R.S.; Pryzbeck, T.R.; Mensforth, R.P. Chronological Metamorphosis of the Auricular Surface of the Ilium: A New Method for the Determination of Adult Skeletal Age at Death. American J Phys Anthropol 1985, 68, 15–28. [CrossRef]

- Meindl, R.S.; Lovejoy, C.O. Ectocranial Suture Closure: A Revised Method for the Determination of Skeletal Age at Death Based on the Lateral-anterior Sutures. American J Phys Anthropol 1985, 68, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- White, T.D.; Folkens, P.A. Human Osteology; 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, 2000;

- Buckberry, J. The (Mis)Use of Adult Age Estimates in Osteology. Annals of Human Biology 2015, 42, 323–331. [CrossRef]

- Witas, H.W.; Płoszaj, T.; Jędrychowska-Dańska, K.; Witas, P.J.; Masłowska, A.; Jerszyńska, B.; Kozłowski, T.; Osipowicz, G. Hunting for the LCT-13910*T Allele between the Middle Neolithic and the Middle Ages Suggests Its Absence in Dairying LBK People Entering the Kuyavia Region in the 8th Millennium BP. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0122384. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.M.; Kubacka, I.; Chinnery, P.F.; Lightowlers, R.N.; Turnbull, D.M.; Howell, N. Reanalysis and Revision of the Cambridge Reference Sequence for Human Mitochondrial DNA. Nat Genet 1999, 23, 147–147. [CrossRef]

- Fellows Yates, J.A.; Lamnidis, T.C.; Borry, M.; Andrades Valtueña, A.; Fagernäs, Z.; Clayton, S.; Garcia, M.U.; Neukamm, J.; Peltzer, A. Reproducible, Portable, and Efficient Ancient Genome Reconstruction with Nf-Core/Eager. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10947. [CrossRef]

- Weissensteiner, H.; Pacher, D.; Kloss-Brandstätter, A.; Forer, L.; Specht, G.; Bandelt, H.-J.; Kronenberg, F.; Salas, A.; Schönherr, S. HaploGrep 2: Mitochondrial Haplogroup Classification in the Era of High-Throughput Sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, W58–W63. [CrossRef]

-

R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2024.

- Bandelt, H.J.; Forster, P.; Röhl, A. Median-Joining Networks for Inferring Intraspecific Phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1999, 16, 37–48. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. Popart: Full-Feature Software for Haplotype Network Construction. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S.; Cockerham, C.C. Estimating F-Statistics for the Analysis of Population Structure. Evolution 1984, 38, 1358. [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Smouse, P.E.; Quattro, J.M. Analysis of Molecular Variance Inferred from Metric Distances among DNA Haplotypes: Application to Human Mitochondrial DNA Restriction Data. Genetics 1992, 131, 479–491. [CrossRef]

- Gower, J.C. Some Distance Properties of Latent Root and Vector Methods Used in Multivariate Analysis. Biometrika 1966, 53, 325–338. [CrossRef]

- Lappalainen, T.; Laitinen, V.; Salmela, E.; Andersen, P.; Huoponen, K.; Savontaus, M.-L.; Lahermo, P. Migration Waves to the Baltic Sea Region. Annals of Human Genetics 2008, 72, 337–348. [CrossRef]

- Šarac, J.; Šarić, T.; Auguštin, D.H.; Jeran, N.; Kovačević, L.; Cvjetan, S.; Lewis, A.P.; Metspalu, E.; Reidla, M.; Novokmet, N.; et al. Maternal Genetic Heritage of Southeastern Europe Reveals a New Croatian Isolate and a Novel, Local Sub-Branching in the X2 Haplogroup. Annals of Human Genetics 2014, 78, 178–194. [CrossRef]

- Kushniarevich, A.; Utevska, O.; Chuhryaeva, M.; Agdzhoyan, A.; Dibirova, K.; Uktveryte, I.; Möls, M.; Mulahasanovic, L.; Pshenichnov, A.; Frolova, S.; et al. Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0135820. [CrossRef]

- Pshenichnov, A.; Balanovsky, O.; Utevska, O.; Metspalu, E.; Zaporozhchenko, V.; Agdzhoyan, A.; Churnosov, M.; Atramentova, L.; Balanovska, E. Genetic Affinities of Ukrainians from the Maternal Perspective. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2013, 152, 543–550. [CrossRef]

- Helgason, A.; Hickey, E.; Goodacre, S.; Bosnes, V.; Stefánsson, K.; Ward, R.; Sykes, B. mtDNA and the Islands of the North Atlantic: Estimating the Proportions of Norse and Gaelic Ancestry. Am J Hum Genet 2001, 68, 723–737.

- Cocoş, R.; Schipor, S.; Hervella, M.; Cianga, P.; Popescu, R.; Bănescu, C.; Constantinescu, M.; Martinescu, A.; Raicu, F. Genetic Affinities among the Historical Provinces of Romania and Central Europe as Revealed by an mtDNA Analysis. BMC Genetics 2017, 18, 20. [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska-Nowak, A.; Safranow, K.; Adamczyk, J.G.; Sołtyszewski, I.; Cięszczyk, P.; Tońska, K.; Żekanowski, C.; Borzemska, B. Mitochondrial Genome Variation in Polish Elite Athletes. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12992. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, J.; Saunier, J.; Strouss, K.; Paintner, C.; Diegoli, T.; Sturk, K.; Kovatsi, L.; Brandstätter, A.; Cariolou, M.A.; Parson, W.; et al. Mitochondrial Control Region Sequences from Northern Greece and Greek Cypriots. Int J Legal Med 2008, 122, 87–89. [CrossRef]

- Modi, A.; Lancioni, H.; Cardinali, I.; Capodiferro, M.R.; Rambaldi Migliore, N.; Hussein, A.; Strobl, C.; Bodner, M.; Schnaller, L.; Xavier, C.; et al. The Mitogenome Portrait of Umbria in Central Italy as Depicted by Contemporary Inhabitants and Pre-Roman Remains. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 10700. [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Chan, J.; Connor, R.; Feldgarden, M.; Fine, A.M.; Funk, K.; Hoffman, J.; et al. Database Resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 53, D20–D29. [CrossRef]

- Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.R.; Altshuler, D.M.; Durbin, R.M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Bentley, D.R.; Chakravarti, A.; Clark, A.G.; Donnelly, P.; Eichler, E.E.; et al. A Global Reference for Human Genetic Variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [CrossRef]

- Tishkoff, S.A.; Gonder, M.K.; Henn, B.M.; Mortensen, H.; Knight, A.; Gignoux, C.; Fernandopulle, N.; Lema, G.; Nyambo, T.B.; Ramakrishnan, U.; et al. History of Click-Speaking Populations of Africa Inferred from mtDNA and Y Chromosome Genetic Variation. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2007, 24, 2180–2195. [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.R.; Sturk-Andreaggi, K.; Ring, J.D.; Huber, N.; Bodner, M.; Crawford, M.H.; Parson, W.; Marshall, C. Resolving Mitochondrial Haplogroups B2 and B4 with Next-Generation Mitogenome Sequencing to Distinguish Native American from Asian Haplotypes. Forensic Science International: Genetics 2019, 43, 102143. [CrossRef]

- Vidrová, V.; Tesařová, M.; Trefilová, E.; Honzík, T.; Magner, M.; Zeman, J. Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups in the Czech Population Compared to Other European Countries. Human Biology 2008, 80, 669–674. [CrossRef]

- Loogväli, E.-L.; Roostalu, U.; Malyarchuk, B.A.; Derenko, M.V.; Kivisild, T.; Metspalu, E.; Tambets, K.; Reidla, M.; Tolk, H.-V.; Parik, J.; et al. Disuniting Uniformity: A Pied Cladistic Canvas of mtDNA Haplogroup H in Eurasia. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2004, 21, 2012–2021. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, L.; Allaby, R.; Skoglund, P.; Der Sarkissian, C.; Stockhammer, P.W.; Ávila-Arcos, M.C.; Fu, Q.; Krause, J.; Willerslev, E.; Stone, A.C.; et al. Ancient DNA Analysis. Nat Rev Methods Primers 2021, 1, 14. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.P.; Huber, C.D. The Genomic Footprints of Migration: How Ancient DNA Reveals Our History of Mobility. Genome Biol 2025, 26, 206. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Map with the Iron Age (IA) sample sites from the territory of modern-day Lithuania, sample group sizes, and archaeological dating. Circle sizes denote sample group size and circle colours denote the IA time periods.

Figure 1.

Map with the Iron Age (IA) sample sites from the territory of modern-day Lithuania, sample group sizes, and archaeological dating. Circle sizes denote sample group size and circle colours denote the IA time periods.

Figure 2.

Diversity and distribution of determined mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups in the IA and modern-day Lithuanian populations. IA samples were divided into the Roman, Migration, and Viking groups based on archaeological dating. Numbers around the pie charts represent haplogroup counts, n – sample group size.

Figure 2.

Diversity and distribution of determined mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups in the IA and modern-day Lithuanian populations. IA samples were divided into the Roman, Migration, and Viking groups based on archaeological dating. Numbers around the pie charts represent haplogroup counts, n – sample group size.

Figure 3.

Diversity and distribution of determined mtDNA haplogroups during the IA and modern-day in the Western, Central, and Eastern regions of Lithuania. Numbers around the pie charts represent haplogroup counts, n – sample group size.

Figure 3.

Diversity and distribution of determined mtDNA haplogroups during the IA and modern-day in the Western, Central, and Eastern regions of Lithuania. Numbers around the pie charts represent haplogroup counts, n – sample group size.

Figure 4.

Diversity and distribution of determined mtDNA haplogroups across the Western, Central, and Eastern regions of Lithuania during the Roman, Migration, Viking (Iron Age) periods, and modern-day. Numbers around the pie charts represent haplogroup counts, n – sample group size.

Figure 4.

Diversity and distribution of determined mtDNA haplogroups across the Western, Central, and Eastern regions of Lithuania during the Roman, Migration, Viking (Iron Age) periods, and modern-day. Numbers around the pie charts represent haplogroup counts, n – sample group size.

Figure 5.

Median-joining haplotype network of mtDNA Hypervariable Region I (HVRI) region loci (range 16126–1320) generated using PopART (v1.7). Circle sizes denote number of samples assigned to each haplotype. Colours denote IA time periods. Black strikes represent number of nucleotide differences between samples.

Figure 5.

Median-joining haplotype network of mtDNA Hypervariable Region I (HVRI) region loci (range 16126–1320) generated using PopART (v1.7). Circle sizes denote number of samples assigned to each haplotype. Colours denote IA time periods. Black strikes represent number of nucleotide differences between samples.

Figure 6.

Fixation index (FST) values for pairwise-comparison between the IA groups and modern-day Lithuanian population.

Figure 6.

Fixation index (FST) values for pairwise-comparison between the IA groups and modern-day Lithuanian population.

Figure 7.

Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) of hamming distances between the IA samples from Lithuania. Hamming distances calculated using the 36 loci from the HVRI region of mtDNA (range 16126–1320).

Figure 7.

Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) of hamming distances between the IA samples from Lithuania. Hamming distances calculated using the 36 loci from the HVRI region of mtDNA (range 16126–1320).

Figure 8.

MDS of hamming distances between the IA and modern-day samples from Lithuania. Hamming distances calculated using the 36 loci from the HVRI region of mtDNA (range 16126–1320).

Figure 8.

MDS of hamming distances between the IA and modern-day samples from Lithuania. Hamming distances calculated using the 36 loci from the HVRI region of mtDNA (range 16126–1320).

Figure 9.

MDS of hamming distances between the IA and modern-day Lithuanian population samples from other European populations and Nigeria. Hamming distances calculated using the 36 loci from the HVRI region of mtDNA (range 16126–1320).

Figure 9.

MDS of hamming distances between the IA and modern-day Lithuanian population samples from other European populations and Nigeria. Hamming distances calculated using the 36 loci from the HVRI region of mtDNA (range 16126–1320).

Table 1.

Abbreviations and sources of the data used in this study. n – sample size.

Table 1.

Abbreviations and sources of the data used in this study. n – sample size.

| Abbreviation |

Country |

n |

Reference |

| Roman |

Lithuania |

29 |

This study |

| Migration |

Lithuania |

48 |

| Viking |

Lithuania |

24 |

| LTU |

Lithuania |

279 |

| LVA |

Latvia |

114 |

Lappalainen et al. 2008 [31] |

| EST |

Estonia |

117 |

| SWE |

Sweden |

307 |

| UKR |

Ukraine |

566 |

Pshenichnov et al. 2013 [34] |

| CZE |

Czech |

94 |

Kushniarevich et al. 2015 [33] |

| BLR |

Belarus |

260 |

| RUS |

Russia |

518 |

| GBR |

England |

142 |

Helgason et al. 2001 [35] |

| NOR |

Norway |

323 |

| ROU |

Romania |

433 |

Cocoş et al. 2017 [36] |

| POL |

Poland |

196 |

Piotrowska-Nowak et al. 2023 [37] |

| HRV |

Croatia |

488 |

Šarač et al. 2014 [32] |

| BIH |

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

369 |

| SVN |

Slovenia |

97 |

| SRB |

Serbia |

81 |

| GRC |

Greece |

319 |

Irwin et al. 2008 [38] |

| CYP |

Cyprus |

91 |

| ITA |

Italy |

191 |

Modi et al. 2020 [39] |

| ITA |

Italy |

50 |

1000 Genomes Project (Auton et al. 2015) [41] |

| FRA |

France |

53 |

| NGA |

Nigeria |

25 |

Table 2.

Comparison of Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) results between a) the IA samples separated into the three periods based on archaeological dating, b) the IA samples as one group the modern group, and c) the IA samples separated into the three periods with modern group. Statistical significance p-value < 0.05.

Table 2.

Comparison of Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) results between a) the IA samples separated into the three periods based on archaeological dating, b) the IA samples as one group the modern group, and c) the IA samples separated into the three periods with modern group. Statistical significance p-value < 0.05.

| Sources of variation |

Estimated

variance (σ2)

|

Proportion of total variance |

Phi-statistic |

p-value

|

| a) Roman, Migration, and Viking groups |

| Between groups |

0.290 |

3.7% |

0.037 |

0.039 |

| Within groups |

7.612 |

96.3% |

|

|

| Total |

7.902 |

100% |

|

|

| b) IA and modern-day Lithuanian population |

| Between groups |

0.049 |

0.7% |

0.007 |

0.102 |

| Within groups |

7.147 |

99.3% |

|

|

| Total |

7.196 |

100% |

|

|

| c) Roman, Migration, Viking groups and modern-day Lithuanian population |

| Between groups |

0.163 |

2.2% |

0.022 |

0.015 |

| Within groups |

7.095 |

97.8% |

|

|

| Total |

7.258 |

100% |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).