1. Introduction

In a recent

workplace trend that defies traditional labels, employees are showing up—but

not fully engaging. They complete their core duties but avoid going “above and

beyond.” This phenomenon, now widely referred to as quiet quitting, has emerged

as a nuanced and controversial expression of disengagement in the post-pandemic

workplace. Unlike actual turnover, quiet quitting reflects a behavioral

withdrawal without physical exit, raising complex questions about its origins,

implications, and solutions.

While many

popular accounts frame quiet quitting as a generational attitude shift or a

conscious reprioritization of work–life boundaries (De Smet et al. 2022), such

portrayals often obscure structural causes rooted in HRM system design.

Specifically, they neglect the extent to which perceived unfairness, poor

managerial practices, and organizational neglect might be driving employee

disengagement. The prevailing focus on individual agency risks overlooking a

critical point: could quiet quitting be less about employees “not trying” and

more about systems “not working”?

The academic

conversation surrounding workplace disengagement has long centered on

constructs such as burnout (Maslach and Jackson 1981), intrinsic motivation

(Deci and Ryan 2000), and work engagement (Schaufeli et al. 2002). In this

tradition, disengagement is typically interpreted as a psychological withdrawal

caused by factors like emotional exhaustion, low autonomy, or misaligned goals

(Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Ryan and Deci 2017). Quiet quitting fits this model

but also raises newer, context-driven concerns.

On the systems

side, human resource management (HRM) theory suggests that misalignment between

employee expectations and organizational practices can erode trust and

discretionary effort (Lepak and Snell 2002). Studies on organizational justice

have consistently shown that employees who perceive injustice—procedural,

distributive, or interpersonal—are more likely to exhibit counterproductive or

withdrawal behaviors (Colquitt 2001; Cropanzano et al. 2007). Similarly, the

effectiveness of HRM systems—especially when practices are perceived as

inconsistent, symbolic, or irrelevant—has a significant impact on employee

commitment and motivation (Wright and Nishii 2013).

Surprisingly,

however, few studies to date have empirically tested whether quiet quitting

stems more from individual-level motivational decline or organizational-level

HRM system failure. Existing studies often rely on anecdotal evidence or

limited conceptual perspectives, leaving a gap in understanding the relative

weight of psychological vs structural predictors of this behavior.

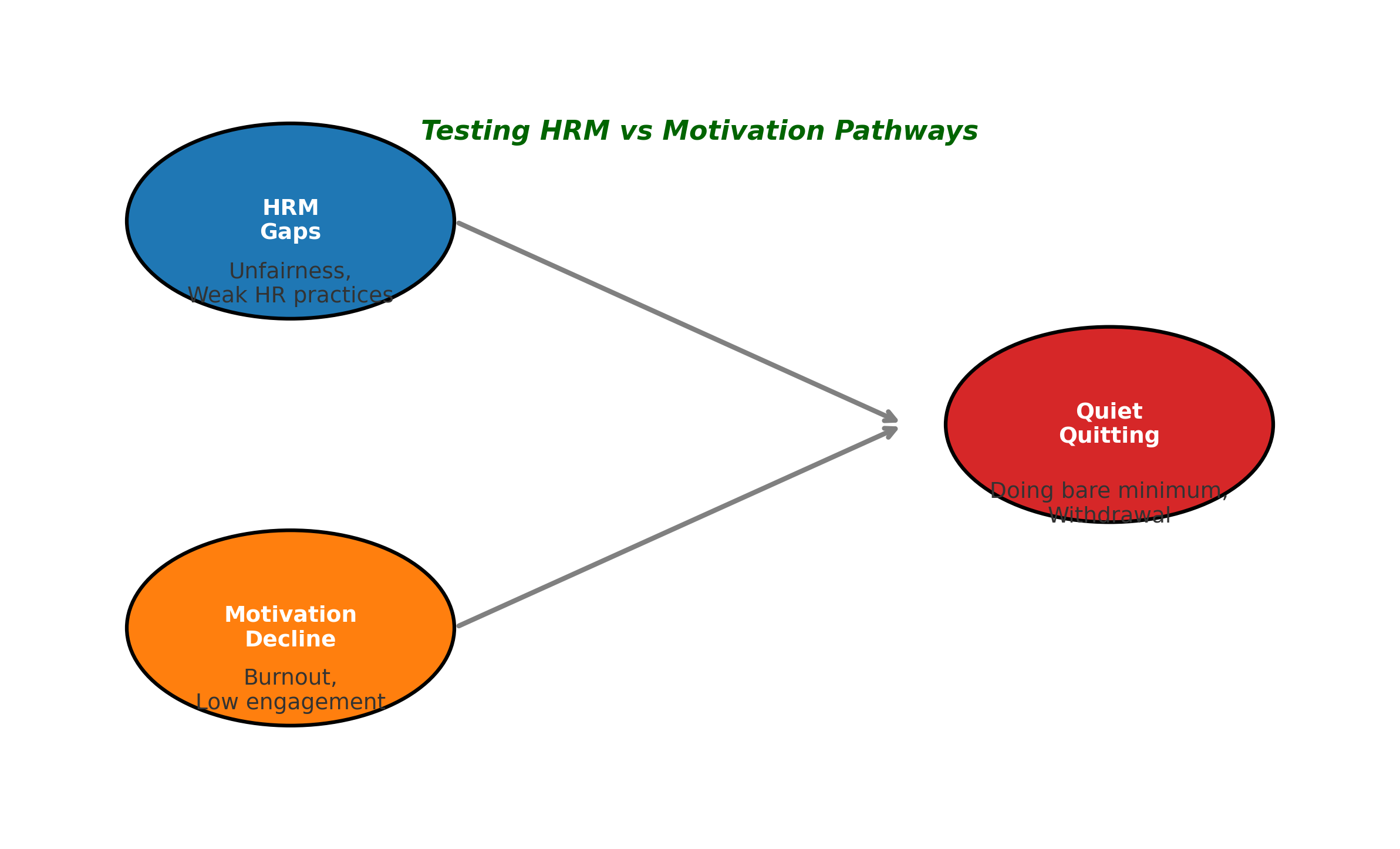

This study

addresses that gap by asking a straightforward yet underexplored question:Is

quiet quitting better explained by HRM system gaps or by motivational decline?

To answer this, we integrate two theoretical pathways into a dual-path model:

Systemic HRM Gaps, captured through measures of organizational justice (Colquitt 2001) and HRM system effectiveness (based on employee perceptions of relevance and coherence).

Motivational Decline, operationalized through validated constructs of intrinsic motivation (Deci and Ryan 2000), burnout (Maslach et al. 2001), and job demands (Karasek 1979; Demerouti et al. 2001).

Specifically,

we develop and empirically test a conceptual model proposing that quiet

quitting is best understood as a symptom of both systemic HRM gaps and

individual motivational decline. Guided by this framework, we propose three

specific hypotheses: H1—that HRM system gaps positively predict quiet quitting;

H2—that intrinsic motivation negatively predicts quiet quitting; and H3—that

burnout mediates the relationship between HRM gaps and quiet quitting.

To empirically

test this model, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of 600 employees across

education, healthcare, technology, and other sectors in Lebanon. Using

validated instruments, we measured perceptions of HRM system gaps, motivational

decline indicators, and quiet quitting tendencies. Structural equation modeling

(SEM) was then applied to test the strength and significance of both conceptual

pathways.

This study

contributes to the evolving literature on disengagement, HRM effectiveness, and

post-pandemic work behavior in three key ways:

It empirically distinguishes between system-level and individual-level causes of quiet quitting.

It validates a dual-path explanatory model, bridging micro-level psychology with macro-level HRM practices.

It offers actionable implications for HR professionals seeking to improve employee retention and engagement not through surveillance or pressure, but through systemic reform and motivation-sensitive policies.

The remainder

of the paper is structured as follows:

Section

2

reviews relevant literature and

builds the dual-path conceptual model.

Section

3

presents the methodology,

including sample, measures, and analysis strategy.

Section 4

details the results.

Section 5

discusses the findings in relation to theory and

practice. Finally,

Section 6

concludes with limitations and future research

directions.

2. Related Work

Understanding

quiet quitting as a workplace phenomenon requires drawing on literature about

human resource management (HRM) systems, employee engagement, and employee

withdrawal. This section reviews how robust HRM systems drive engagement, how

burnout can erode motivation, and how quiet quitting has been conceptualized in

recent debates. It highlights two potential pathways to quiet quitting: one

stemming from gaps or failures in the HRM system, and another from individual

motivational decline.

2.1. HRM Systems and Employee Engagement

Extensive

research indicates that well-designed HRM practices and systems can foster

higher employee engagement and commitment. Employee engagement refers to a

state in which individuals are fully absorbed in and enthusiastic about their

work, investing extra effort and energy (Kahn 1990). High-involvement or

high-performance HRM practices (e.g., training, participation, recognition)

signal support and value for employees, which in turn drives them to engage

more deeply in their roles. For example, one study found that when employees

perceived stronger HR practices in their organization, they reported higher

engagement levels and were more likely to display organizational citizenship

behaviors (Alfes et al. 2013). Such practices create an environment of trust

and reciprocity consistent with social exchange theory—employees reciprocate

supportive HRM by going above and beyond their formal duties. Recent conceptual

work on

“caring” HRM

underscores that when employees feel genuinely

cared for through fair and family-friendly policies, their engagement is

bolstered (Saks 2022). This caring-oriented approach reflects a shift in HRM

thinking toward employee well-being as a precursor to commitment and

discretionary effort.

A critical

aspect of HRM effectiveness is the HRM system strength – i.e., how consistently

and clearly HR policies are communicated and implemented across an

organization. In a strong HRM system, employees receive unambiguous signals

that help align their behaviors with organizational goals (Bowen and Ostroff

2004). By contrast, gaps or inconsistencies in the HRM system – for instance,

when promised practices are not actually delivered – can undermine engagement.

If an organization claims to reward excellence but fails to do so in practice,

employees may become cynical or withdraw their extra effort. Indeed, when

employees perceive that the organization has broken its promises or failed to

meet its obligations (a psychological contract breach), they often respond by

reducing their contributions and commitment (Robinson and Rousseau 1994; Zhao

et al. 2007). A meta-analysis by Zhao et al. (2007) confirmed that

psychological contract breaches are significantly associated with lower job

satisfaction, trust, and organizational citizenship behavior. This aligns with

the notion that HRM system gaps – discrepancies between espoused HR

policies and employees’ actual experiences – erode the foundation of

engagement. Over time, repeated disappointments in HRM practices (e.g., unfair

promotions, poor communication, lack of growth opportunities) can prompt

employees to pull back effort and involvement as a form of self-protection or

silent protest.

On the positive

side, effective HRM practices not only prevent disengagement but actively

promote engagement. Studies have shown that

high-performance

work systems

that invest in

employees’ skills, empowerment, and rewards tend to increase employees’

affective commitment and involvement in their work. Engaged employees willingly

undertake extra-role activities and “go the extra mile” beyond their formal job

requirements (Kehoe and Wright 2013). In short, a robust HRM system sets the

stage for engagement by aligning organizational support with employee

expectations. Conversely, a weak or misaligned HRM system – one characterized

by low support, inconsistency, or perceived injustice – can trigger

disengagement. A recent meta-analytic review provides evidence that strong

perceived workplace support is linked to lower incidence of quiet quitting,

whereas perceptions of injustice and workplace conflict increase the likelihood

of quiet quitting (Geng et al. 2025). This underscores the powerful role of

organizational context: employees are less inclined to mentally “check out”

when they feel supported and treated fairly, but are more likely to withdraw

effort when HRM practices or leadership behaviors send negative signals.

2.2. Burnout and Motivational Decline

While HRM

factors shape the work climate, an individual’s level of motivation and

well-being is another critical piece of the quiet quitting puzzle. Workplace

burnout, in particular, has been widely studied as a driver of reduced

motivation and withdrawal behaviors. Burnout is defined as a chronic state of

physical and emotional exhaustion coupled with cynicism and a reduced sense of

efficacy (Maslach et al. 2001). It often results from prolonged job stressors –

high workload, role conflict, lack of control or recognition – and leads to

what might be termed a motivational decline. As employees burn out, their

intrinsic enthusiasm and energy for the job wane, often precipitating a form of

disengagement. Maslach and Leiter (2001) have described burnout and engagement

as opposite ends of a continuum: as burnout increases, an employee’s engagement

typically plummets. Burned-out employees frequently display symptoms such as

depersonalization (distancing themselves from work or clients) and minimal

effort investment, which mirror the behaviors observed in quiet quitting.

The process by

which burnout translates to reduced effort can be understood through conservation

of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989). When employees experience resource

depletion (energy, resilience, optimism), they naturally strive to conserve

what remains by withdrawing from non-essential tasks. In practice, this may

mean doing only what is necessary to get through the workday while avoiding any

additional initiatives – essentially the behavioral essence of quiet quitting.

Empirical evidence supports this link: for instance, a recent study in the

hospitality sector found that employees facing high role conflicts and

stressful work demands suffered lower well-being and higher burnout, which in

turn led to quiet quitting behaviors (Prentice et al. 2024). In that study,

burnout acted as a mediator between work stress (role conflicts) and quiet

quitting, indicating that excessive demands drained employees’ motivation and

pushed them toward minimal engagement as a coping mechanism. When work

conditions continually tax employees without adequate support or reward,

motivational decline is a predictable outcome.

Another

important concept is the “neglect” response in reaction to job dissatisfaction.

Classic models of responses to dissatisfaction (e.g., the

Exit-Voice-Loyalty-Neglect framework) propose that some employees respond to

adverse conditions by passively allowing their performance to deteriorate

(neglect) rather than actively voicing concerns or quitting outright. Burnout

can precipitate this neglectful stance – employees simply have no energy or

optimism left to invest in improving the situation, so they emotionally check

out. The emerging quiet quitting behavior aligns closely with this neglect

mode, wherein the employee remains in the organization but mentally withdraws.

Indeed, a meta-review of quiet quitting antecedents across industries found

that burnout and stress were consistently positively correlated with quiet

quitting, while indicators of positive motivation (job satisfaction,

organizational commitment) were negatively correlated (Geng et al. 2025). In

practical terms, as employees become exhausted and disillusioned, their

willingness to expend extra effort or engage proactively diminishes.

It is worth

noting that reducing one’s effort can sometimes be a form of self-preservation

rather than sheer counter productivity. Some scholars argue that setting

stricter boundaries at work – essentially not over-extending oneself – can be a

healthy adaptive response to burnout. For example, a study of school teachers

after the COVID-19 pandemic found that teachers who curtailed extra-role

activities (a behavior akin to quiet quitting) actually experienced lower

burnout, as it prevented them from overwork (Tsemach and Barth 2023). In that

context,

quiet quitting behavior

(not taking on additional responsibilities

beyond the job description) was interpreted as a “positive” trend that helped

reduce burnout among teachers who had been overextending themselves.

This perspective suggests that motivational decline is sometimes a consequence

of unsustainable effort, and that a conscious reduction in extra work can

stabilize one’s well-being. Thus, while burnout generally leads to

disengagement as a dysfunctional outcome, a controlled dial-back of effort may

serve as a coping mechanism to avoid full-blown burnout.

In summary,

existing literature establishes a clear link between declining employee

well-being (especially burnout) and withdrawal of work effort. Burnout

represents an involuntary depletion of motivation that often manifests in

behaviors analogous to quiet quitting: less initiative, minimal involvement,

and cynicism toward one’s job (Maslach et al. 2001). When the work environment

continually drains employees and offers little recuperation, motivational

decline can set in, prompting employees to do only what is necessary to get by.

Such withdrawal can be seen as the individual-level path to quiet quitting,

distinct from (but often interacting with) the organizational-level influences

discussed earlier.

2.3. Quiet Quitting: Debates and Dual Pathways

The term “quiet

quitting” gained popular prominence in 2022, referring to employees who deliberately

limit their work effort to the bare minimum required, offering no voluntary

extra contributions. Although the label is new, scholars have noted that the

core behavior is not entirely unprecedented (Atalay and Dağıstan 2024). In

essence, quiet quitting reflects a form of on-the-job withdrawal – employees

remain in their position but psychologically disengage, adhering

strictly to their formal role requirements and not a jot more. Harris (2025)

defines quiet quitting as workers “intentionally opting to adhere to contracted

duties/hours while avoiding taking on additional responsibilities.” This

conscious decision to withhold extra effort is what differentiates quiet

quitting from mere poor performance or lassitude. It is often described as a

voluntary and active adjustment of work engagement, rather than outright

laziness or incompetence (Harris 2025).

A key debate

surrounding quiet quitting is whether to view it primarily as a

symptom of organizational issues

or as an

individual

coping strategy

. One viewpoint,

common in early media portrayals, is that quiet quitting is a form of employee

malaise or moral hazard – a problematic trend where disengaged employees coast

along, harming organizational performance. From this perspective, quiet quitting

is unequivocally negative for organizations, as it entails the loss of

discretionary effort that can be crucial for innovation, customer service, and

overall productivity. For example, in the hospitality industry, commentators

have warned that quiet quitting by frontline staff (doing the strict minimum

for guests) can undermine service quality and customer satisfaction

(Liu-Lastres et al. 2023). Such concerns echo traditional organizational

behavior findings that employee discretionary effort is linked to important

outcomes, and its absence – a silent withdrawal – can have detrimental effects.

Indeed, early analyses have treated quiet quitting as a threat that managers

must combat through better engagement strategies, lest overall performance

suffer (Liu-Lastres et al. 2023).

However,

another viewpoint frames quiet quitting in a more sympathetic light: as a

rational response by employees to either unsatisfactory work conditions or to

preserve work–life balance. Hamouche et al. (2023) observe that quiet quitting

closely resembles classic collective actions like “work-to-rule” or the ethos

of “acting your wage,” suggesting it can be understood as a form of protest or

boundary-setting. In their critical review, Hamouche et al. (2023) connect

quiet quitting to concepts such as employee cynicism and employee silence,

indicating that it often arises when employees feel voiceless, unappreciated,

or treated unjustly. An employee who perceives repeated unfairness or breach of

the psychological contract may “quit quietly” as a way to restore a sense of

fairness – effectively recalibrating their inputs to match what they feel the

organization has given them. This aligns with equity theory: if an employee

feels under-rewarded for their effort, reducing that effort is an attempt to

rebalance the equation. Recent empirical work supports this logic: for

instance, a meta-analysis found that employees’ perceptions of injustice and

unresolved workplace conflicts significantly increased quiet quitting behaviors

(Geng et al. 2025). In other words, one pathway to quiet quitting is through

HRM system gaps and negative workplace experiences that erode employees’

organizational commitment. When good performers see poor leadership, arbitrary

decisions, or lack of growth opportunities, they may not necessarily resign

immediately – instead, they disengage internally and contribute only what they

must. This can be viewed as a subtler form of exit, minus the physical

quitting.

The alternative

pathway to quiet quitting is the individual burnout route discussed earlier – a

more inadvertent slide into disengagement due to motivational decline. Harris

(2025) makes an important distinction: unlike burnout, which is an

involuntary

state of exhaustion and detachment, quiet quitting (in its pure form) is

often a

conscious choice

to recalibrate one’s work boundaries.

Nevertheless, the two phenomena can converge. A burned-out employee might

decide

to stop going above and beyond as a means to cope, thereby

consciously

enacting quiet quitting. Thus, the dual-path model is not necessarily

either/or; in practice, quiet quitting can result from a combination of

external drivers (HRM failings) and internal drivers (burnout or

loss of motivation). An integrative study of quiet quitting among Greek

employees illustrated this interplay: it identified breaches of the

psychological contract and cycles of emotional exhaustion as jointly giving

rise to quiet quitting behaviors (Georgiadou et al. 2025). In that context,

unmet expectations (an HRM issue) initiated disengagement, and emotional

exhaustion (an individual issue) perpetuated it, creating a cycle of

withdrawal.

The quiet

quitting debate also touches on outcomes for employees themselves. While

organizations clearly lose out on discretionary effort, employees engaging in

quiet quitting may experience short-term relief or preservation of well-being.

By intentionally limiting their workload to what is contractually required,

employees protect their personal time and energy, potentially staving off

further burnout. Tsemach and Barth’s (2023) findings exemplify this: teachers

under intense pressure who pulled back on extra duties reported lower burnout,

implying that a degree of quiet quitting functioned as

a burnout prevention mechanism

. On the other hand, there could be longer-term

career costs for quiet quitters, such as stalled development or fewer

advancement opportunities, since they are no longer signalling initiative or

“going the extra mile.” The literature has yet to conclusively document these

individual consequences, but it is a logical extrapolation of organizational

behavior theories that reduced effort and involvement might negatively affect

performance evaluations or promotion prospects.

In summary,

emerging research portrays quiet quitting as a multifaceted construct with dual

pathways. One path begins with the organization: inconsistent HRM systems, poor

leadership, and unfair practices breed cynicism and disengagement, leading

employees to withdraw effort as a form of silent protest or adjustment. The

other path begins with the individual: prolonged stress and burnout deplete an

employee’s capacity and willingness to engage, leading to a voluntary scaling

back of effort to preserve remaining resources. Both paths result in a similar

outcome – employees fulfilling their basic job duties but abstaining from any

voluntary extra-role performance. Scholars increasingly view quiet quitting not

as a monolithic behavior but as a spectrum of disengagement with varied

antecedents and even varied outcomes (Harris 2025). Rather than a purely “bad

employee” phenomenon, quiet quitting is better understood as a

symptom

of deeper issues: it may indicate unaddressed organizational problems (like HRM

system failures or contract breaches) and/or signal an individual’s coping

response to excessive strain or diminished motivation.

Recognizing

these dual origins is crucial for both researchers and practitioners. For

researchers, it suggests that models of quiet quitting should integrate both

organizational-level factors (e.g., HRM practices, culture, justice

perceptions) and individual-level factors (e.g., burnout, work values) to fully

explain why employees choose this form of withdrawal. Recent work is indeed

moving in this direction – for example, meta-analytic evidence shows both lack

of support (organizational factor) and high stress (individual factor)

independently contributing to quiet quitting (Geng et al. 2025). For

practitioners, the dual-path perspective implies that interventions must be

two-pronged: HRM reforms to fix system gaps and re-engage employees, and

well-being initiatives to address burnout and rekindle employees’ intrinsic

motivation. If quiet quitting is a symptom, then improving the HRM environment

(clear communication, fairness, recognition) and supporting employees’ mental

health and growth are the remedies to consider, rather than simply chastising

employees for not “going above and beyond.”

In conclusion,

the related literature points to quiet quitting as an emergent construct rooted

in longstanding concepts of engagement, withdrawal, and burnout. HRM system

strength and fairness set the tone for whether employees are inclined to engage

or quietly disengage. At the same time, individual motivational states heavily

influence their propensity to contribute beyond the basics. Quiet quitting sits

at the intersection of these domains – it is where suboptimal organizational

context meets depleted personal motivation. Future research is encouraged to

build on this dual-path model, exploring how HRM interventions and burnout

prevention efforts might jointly reduce the incidence of quiet quitting. The

debate over quiet quitting, far from just a trendy topic, opens up important

conversations about sustainable work engagement and the evolving

employee–employer social contract in the post-pandemic era.

2.4. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses.

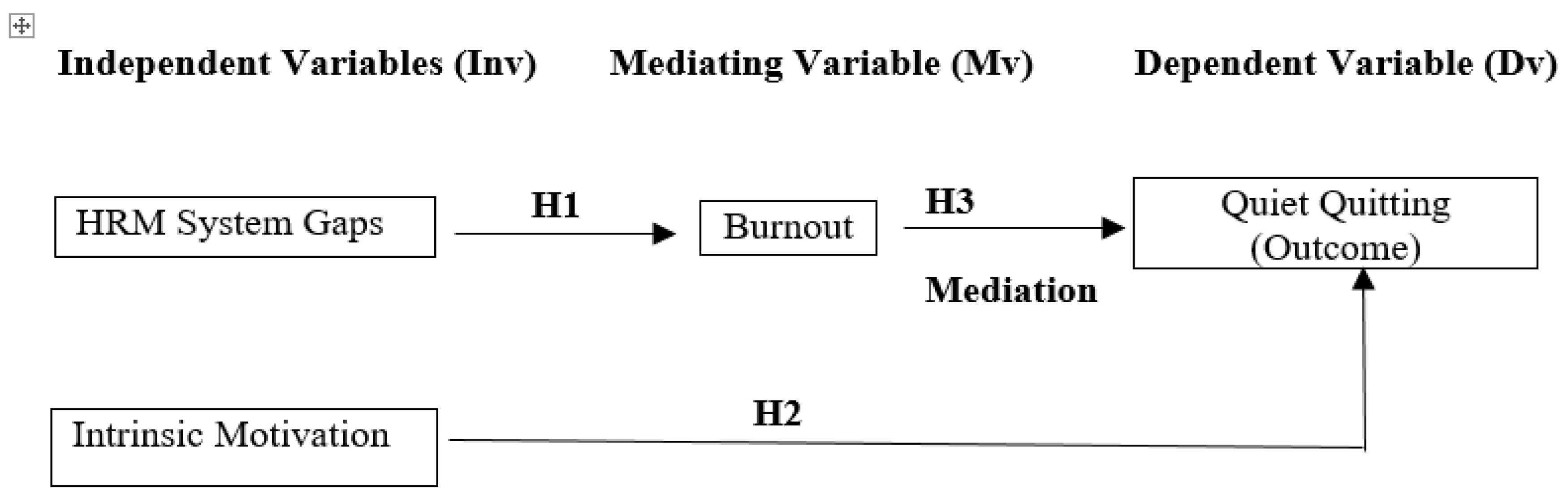

Drawing upon

the theoretical premises established in the related literature, the conceptual

framework underpinning this study integrates both organizational and

individual-level antecedents to explain the phenomenon of quiet quitting. As

illustrated in

Figure 1

below, the model hypothesizes that quiet

quitting behavior—defined as a reduction in discretionary effort and

psychological engagement at work—is driven by two primary pathways: systemic

deficiencies within the HRM environment and motivational decline at the

employee level.

On the

organizational side, HRM system gaps are theorized to have a direct, positive

influence on quiet quitting. These gaps encapsulate employees’ perceptions of

unfair treatment, lack of recognition, insufficient voice, or weak

organizational support structures. When such perceptions accumulate, they are

likely to foster a sense of disengagement, prompting employees to retreat from

proactive work behaviors.

At the

individual level, intrinsic motivation is proposed as a counterforce to quiet

quitting. Employees with higher intrinsic motivation—those who derive internal

satisfaction from their tasks—are expected to be less susceptible to

disengagement, even in the face of structural limitations. Hence, a negative

relationship is anticipated between intrinsic motivation and quiet quitting.

Burnout serves

a dual role within the model. Conceptualized as an intermediary psychological

state marked by emotional exhaustion and reduced personal efficacy, burnout is

positioned as a mediating variable. It is hypothesized that HRM system gaps

exert an indirect effect on quiet quitting by fostering conditions that lead to

burnout, which in turn prompts employees to withdraw. This mediated pathway

enriches the model’s explanatory power by linking structural organizational

failures to psychological outcomes that directly precipitate disengagement.

From this

framework emerge the study’s central hypotheses. H1 posits a positive

direct association between HRM system gaps and quiet quitting. H2

proposes a negative direct association between intrinsic motivation and quiet

quitting. H3 postulates that burnout mediates the relationship between

HRM system gaps and quiet quitting. Together, these hypotheses operationalize

the dual-path explanation tested in this study, offering a holistic

understanding of quiet quitting as a function of both systemic HRM issues and

individual psychological states.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

We tested our

hypotheses using a cross-sectional survey of employees from various industries.

A total of 600 working professionals participated. The sample was drawn

primarily from Lebanon. The respondents averaged 37.1 years of age (SD = 10.2)

and had about 13.5 years of work experience. Women represented 59% of the

sample. Most participants were employed full-time (72%), with others on

part-time, or fixed-term contracts. To reach a broad range of respondents, we

distributed an online questionnaire via professional networks and social media.

Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Before proceeding, respondents

provided informed consent and confirmed they were currently employed adults. We

implemented procedural safeguards to reduce common method bias, such as

assuring anonymity and psychologically separating predictor and criterion

sections of the survey (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Data collection occurred over a

Six-week period. After removing incomplete entries, we retained all 600 valid

responses for analysis. Given the self-report, single-timepoint design, we

conducted a Harman single-factor test; no single factor accounted for the

majority of variance, suggesting that common method variance was not a severe

concern (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

3.2. Measures

All constructs

were measured with established or theory-driven scales.

Table 1

summarizes each construct, the scale items, and internal consistency

reliability (Cronbach’s α) for our sample. Unless noted otherwise, respondents

rated all items on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 =

strongly agree).

Quiet

Quitting.

We conceptualized

quiet

quitting as the voluntary reduction of work effort to the minimum required,

reflecting a withdrawal of discretionary effort. Because no widely validated

measure existed at the time of our study (cf. Galanis et al. 2023), we

developed five items to capture this behavior, informed by definitions in the

emerging literature (Mahand and Caldwell 2023; Agarwal et al. 2024). These

items assessed the extent to which individuals limit their work involvement to

only what is formally expected (e.g., “I do only what is required and nothing

more at work”). Higher scores indicate greater quiet quitting behavior (i.e.,

lower extra-role effort). As shown in

Table 1

, the quiet quitting scale

exhibited good reliability in our sample (α = 0.84).

Intrinsic

Work Motivation.

To gauge

employees’ internal motivation for their job, we used six items assessing intrinsic

work motivation. These items were adapted from prior research on intrinsic

motivation at work (Deci and Ryan 2000; Grant 2008) and tapped the enjoyment,

interest, and meaningfulness derived from the job (e.g., “I enjoy the work I

do”). A high score reflects a strong inherent interest in and personal reward

from one’s work. Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.92, indicating excellent

reliability.

Emotional

Exhaustion.

We measured burnout

symptoms in the form of emotional exhaustion using five items from the

Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach and Jackson 1981). These items capture

feelings of being emotionally overextended and depleted by one’s work (e.g., “I

feel emotionally drained from my work”). Participants indicating agreement on

these items signified higher burnout or fatigue. The emotional exhaustion scale

was reliable in this study (α = 0.89).

Workload.

Perceived workload and job demands were

measured with four items adapted from the Job Content Questionnaire (Karasek

1979). The items assess quantitative workload and time pressure (e.g., “I have

to work very fast” and “I experience time pressure at work”). Higher scores

represent greater work demands. The workload index showed acceptable internal

consistency (α = 0.80).

Organizational

Justice.

We included measures of

perceived organizational justice to capture potential gaps in fair

treatment as an aspect of the HRM system. Following Colquitt’s (2001) justice

dimensions, we assessed four facets: distributive justice (fairness of

outcomes, 2 items, α = 0.76), procedural justice (fairness of processes,

2 items, α = 0.65), interpersonal justice (respectful treatment by supervisors,

2 items, α = 0.91), and informational justice (adequacy of explanations and

transparency, 2 items, α = 0.85). Example items include “My work rewards

reflect the effort I put in” (distributive) and “Communications from my manager

are honest and transparent” (informational). Although each justice subscale had

only two items (yielding relatively lower α for procedural justice), together

these measures provide a broad indication of the fairness climate. We used

these justice indicators as part of the assessment of HRM system functioning,

with higher scores denoting higher perceived fairness.

HRM System

Gap.

To directly examine

employees’ perceptions of gaps in the human resource management system, we

developed three items focusing on the responsiveness and consistency of HR

practices. This HRM system gap scale was informed by the concept of HR

system strength (Bowen and Ostroff 2004) and the idea that misalignment between

formal HR policies and actual practice can undermine employee commitment. The

items ask whether the HR department is responsive to employee needs and

supports growth, and explicitly whether “there is a gap between the HR policies

and how they are actually implemented.” The first two items were reverse-coded

so that higher scores consistently indicate a weaker HRM system (i.e.,

greater HRM implementation gap or shortfall). Employees who perceive poor HR

responsiveness and a policy–practice gap score higher on this scale. In our

data, the three-item HRM gap measure achieved α = 0.82, suggesting good

reliability.

3.3. Analytical Strategy

We employed structural equation modeling (SEM) to test whether quiet

quitting is better explained by HRM system factors or by individual

motivational decline. As a preliminary step, we conducted confirmatory factor

analysis (CFA) to assess the distinctness and construct validity of our key

measures. The integrated dual-path model achieved a good fit to the data (χ²/df

= 2.48, CFI = 0.943, RMSEA = 0.059), indicating that the SEM results are

within acceptable thresholds for model fit, supporting the scales’ discriminant

validity. We then computed descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations to

explore preliminary associations among variables.

To formally test our hypotheses, we employed hierarchical multiple

regression analyses. Quiet quitting served as the dependent variable.

Specifically, regression analyses were utilized to evaluate H1, testing whether

HRM system gaps positively predict quiet quitting, and H2, examining the

negative predictive relationship of intrinsic motivation on quiet quitting. SEM

was specifically used to test H3, examining burnout as a mediator between HRM

system gaps and quiet quitting, and to evaluate the overall dual-path

conceptual model. In Step 1 of the regression, we entered control variables

(respondent age, gender, and work experience) to account for any baseline

effects. In Step 2, we entered the HRM-related predictors – specifically, the

HRM system gap scale and the four justice dimensions – to assess the variance

in quiet quitting explained by perceived HRM system shortcomings. In Step 3, we

entered the individual motivation-related predictors – intrinsic motivation and

emotional exhaustion – to examine the added explanatory power of employees’

motivational states. This ordering allowed us to compare the contributions of

HRM system gaps versus motivational decline in predicting quiet quitting. We

inspected the change in explained variance (ΔR²) from Step 2 to Step 3, as well

as the significance and standardized coefficients of all predictors in the

final model. Multicollinearity checks indicated no serious issues (all VIFs

< 2.0). Finally, we probed the relative importance of the two sets of

factors: a significant increase in R² with the motivational variables, coupled

with strong effects for intrinsic motivation or exhaustion, would suggest that

quiet quitting is more symptomatic of motivational decline. Conversely, if HRM

system gap indicators remain the stronger predictors, it would imply quiet

quitting is better explained as a response to organizational HRM deficiencies.

All significance tests were two-tailed with a 0.05 alpha level. We used SPSS 28

and AMOS 24 software for the statistical analyses. The results of these

analyses are reported in the next section.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Counter to expectations, not all presumed antecedents showed strong

relationships with quiet quitting.

Table 2

reports the

means, standard deviations, and reliability coefficients for all constructs.

Notably, respondents on average reported low perceived fairness in rewards and

procedures (M = 2.47, SD = 0.98) despite relatively high supervisor respect (M

= 4.06, SD = 0.84), indicating that while interpersonal treatment by

supervisors was generally positive, there were broader system-level fairness

concerns. Likewise, the mean perceived gap between HR policies and practice was

above the scale midpoint (M = 3.51, SD = 1.00), hinting at inconsistencies in

HRM system implementation. All multi-item scales demonstrated good internal

consistency (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.80), with especially high reliability for Quiet

Quitting (α = 0.91) and Intrinsic Motivation (α = 0.92), as shown in

Table 2

. These metrics suggest the constructs were measured

with acceptable reliability. In contrast, quiet quitting was significantly

associated with several attitudinal and perception variables in the expected

directions, whereas workload was virtually uncorrelated with quiet quitting

behavior (r = –0.03, n.s.;

Table 3

), suggesting that heavy job

demands alone do not translate into withdrawal.

Bivariate correlations among key variables are presented in . Quiet quitting was strongly negatively correlated with intrinsic motivation (r = –0.50***), indicating that employees who reported lower personal motivation and enjoyment in their work were far more likely to engage in quiet quitting behaviors. Quiet quitting was also positively correlated with burnout (r = 0.43***), consistent with the view that emotional exhaustion and frustration relate to higher withdrawal. In line with the HRM perspective, quiet quitting showed moderate negative correlations with perceived voice (r = –0.31***), supervisor respect (r = –0.27***), managerial communication transparency (r = –0.29***), and HR support (r = –0.26***), all p < 0.001. Thus, employees who felt they lacked a voice in decision processes, received poorer treatment or communication from management, or had less supportive HR practices tended to only meet minimum job requirements. Quiet quitting was positively correlated with the perceived HR policy-practice gap as well (r = 0.20***), suggesting that greater inconsistency between stated HR policies and actual practice coincided with higher withdrawal behavior. On the other hand, as noted above, workload (job demands) had no significant correlation with quiet quitting (r = –0.03, n.s.), an intriguing null finding indicating that objective work pressure by itself was not associated with doing the bare minimum. It is worth noting that many of the HRM system variables were inter-correlated: for example, fairness was strongly positively correlated with HR support (r = 0.60***) and negatively with the HR policy-practice gap (r = –0.51***), reflecting an overall pattern of interrelated positive work climate perceptions. Such multicollinearity necessitated a multivariate approach to determine their unique contributions, as described next.

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling Results

We next tested three nested structural models to compare the explanatory power of motivation-based predictors versus HRM system predictors of quiet quitting. All models were specified with Quiet Quitting as the criterion (dependent variable).

Model 1 included only the two motivation-related constructs – intrinsic motivation and burnout – as predictors.

Model 2 included only the HRM system-related constructs (perceived fairness, voice, supervisor respect, manager communication, HR support, and HR policy-practice gap) as simultaneous predictors.

Model 3 was the integrated model combining both sets of predictors. summarizes the standardized path coefficients (β) and explained variance (R²) for each model, and

Figure 2 depicts the final path diagram.

Model 1 (Motivation-Only): This model provided a substantial explanation of quiet quitting behavior, with R² = 0.28, meaning about 28% of the variance in quiet quitting was accounted for by employees’ motivation levels. Both predictors in Model 1 were statistically significant. Intrinsic motivation had a strong negative effect on quiet quitting (β = –0.38, p < .001), indicating that employees who found their work meaningful and energizing were much less likely to limit their efforts to the bare minimum. Conversely, burnout showed a significant positive effect (β = +0.20, p < .001), consistent with the expectation that exhausted or emotionally drained employees are more prone to withdraw effort. These results support the “motivational decline” explanation: lower work motivation and higher burnout are associated with increased quiet quitting.

Model 2 (HRM System-Only): In contrast, the model containing only HRM system factors explained a more modest portion of variance (R² = 0.14). Moreover, most HR-related predictors did not individually contribute significantly when considered together. The sole exception was employee voice, which emerged as a significant negative predictor (β = –0.19, p < .001) of quiet quitting. This indicates that employees who feel they have a say in decision-making are less likely to disengage and restrict their contributions. However, perceived fairness (β = +0.08, n.s.), supervisor respect (β = –0.09, n.s.), manager communication (β = –0.09, n.s.), HR support (β = –0.09, n.s.), and the HR policy-practice gap (β = +0.08, n.s.) all showed no significant unique effects in this model – their small observed coefficients did not reach significance (). It appears that these facets of the HRM system, while correlated with quiet quitting in isolation (), overlap in influence and thus none (aside from voice) stood out as a clear independent predictor when tested simultaneously. This finding was somewhat surprising, as it suggests that formal justice and HR support factors were weaker determinants of quiet quitting than expected when controlling for each other.

Model 3 (Integrated Model): Incorporating both sets of predictors, the integrated Model 3 accounted for approximately 30% of the variance in quiet quitting (R² = 0.30), representing an improvement over Model 2 (ΔR² = +0.16) and a slight increase over Model 1 (ΔR² = +0.02). Consistent with the bivariate results, intrinsic motivation remained a strong negative predictor of quiet quitting in the combined model (β = –0.34, p < .001), and burnout remained a significant positive predictor (β = +0.19, p < .001). Thus, even after accounting for HRM-related perceptions, employees’ motivational states continued to play a dominant role in explaining quiet quitting. Among the HRM factors, employee voice continued to show a significant unique effect (β = –0.12, p < .01) in Model 3, reinforcing the importance of participative decision-making climate in mitigating withdrawal behavior. In contrast, most other HRM system variables did not exhibit significant direct effects on quiet quitting when motivational factors were simultaneously considered. Notably, the HR policy-practice gap – the focal “HRM system gap” variable – had a non-significant path in the integrated model (β = +0.05, p = .27), indicating that once employees’ motivation and burnout levels (and other perceptions) were taken into account, the direct association between perceived HR inconsistency and quiet quitting was negligible.

One unexpected result in Model 3 was that the perceived fairness path coefficient, which was negative in simple correlations, became significantly positive (β = +0.14, p < .01) when controlling for the other predictors. In other words, when holding motivation and other factors constant, higher fairness perceptions were associated with slightly more quiet quitting. This suppression effect is likely statistical in nature, arising because fairness was moderately correlated with intrinsic motivation and (inversely with) burnout (). When those motivational variables are controlled, the residual impact of fairness on quiet quitting appears in the opposite direction, though its magnitude is relatively small. Importantly, supervisor respect, manager communication, and HR support paths all remained non-significant in the combined model (βs between –0.01 and –0.04, n.s.), suggesting that, after accounting for employee voice and motivation/burnout, these aspects of the work environment did not uniquely predict whether employees engaged in quiet quitting. In sum, the integrated model results indicate that quiet quitting is more directly driven by employees’ dwindling motivation (low engagement and high burnout) than by perceived gaps in the HRM system, although a lack of voice in the organization does independently contribute to higher quiet quitting tendencies.

Table 4.

Standardized path coefficients (β) and explained variance for structural models predicting Quiet

Quitting (N = 600). Model 1 includes motivation-based predictors only; Model 2 includes +HRM system-based

predictors only; Model 3 is the fully integrated model.

Table 4.

Standardized path coefficients (β) and explained variance for structural models predicting Quiet

Quitting (N = 600). Model 1 includes motivation-based predictors only; Model 2 includes +HRM system-based

predictors only; Model 3 is the fully integrated model.

| Predictor |

Model 1 β |

Model 2 β |

Model 3 β |

| Intrinsic Motivation |

–0.38*** |

— |

–0.34*** |

| Burnout |

+0.20*** |

— |

+0.19*** |

| Fairness |

— |

+0.08 |

+0.14** |

| Voice |

— |

–0.19*** |

–0.12** |

| Supervisor Respect |

— |

–0.09 |

–0.01 |

| Manager Communication |

— |

–0.09 |

–0.04 |

| HR Support |

— |

–0.09 |

–0.04 |

| HR Policy-Practice Gap |

— |

+0.08 |

+0.05 |

| R² (Quiet Quitting) |

0.28 |

0.14 |

0.30 |

5. Discussion

This study set out to test whether the emerging phenomenon of quiet quitting is better explained by a decline in individual motivation or by gaps in the organizational HRM system. In other words, the central question was: Is quiet quitting primarily a result of employees losing motivation (e.g., burnout/disengagement), or does it stem from shortcomings in how the organization manages and rewards its people? Our findings indicate that quiet quitting is more strongly driven by motivational decline at the individual level than by HRM system gaps. The model focusing on personal factors (e.g., reduced engagement, burnout) provided a better fit and higher explanatory power for quiet quitting behavior, whereas the HRM-related factors, while contributory, were comparatively weaker. In practical terms, Hypothesis 1 (H1), which posited that quiet quitting would be driven by deficiencies in the HRM system (such as lack of support or rewards), received only partial support, Hypothesis 2 (H2) which posited that quiet quitting would be associated with declining employee motivation and engagement, was supported. Thus, in answer to our central question, the evidence suggests that quiet quitting aligns more with an employee’s waning motivation (and related psychological states) than with any single failure of HR policies, though the two are not entirely independent. Notably, the individual-pathway model outperformed the organizational-pathway model, underscoring that the roots of quiet quitting often lie within the employee’s own experience and mindset.

These findings offer important insights into the nature of quiet quitting and how it connects to existing theories. Quiet quitting can be understood as a form of employee withdrawal that is distinct from outright quitting; rather than resigning, employees withdraw effort. The fact that the individual motivation pathway dominated in our results is consistent with viewing quiet quitting as a coping mechanism for employees facing resource depletion. Recent work by Agarwal et al. (2024) describes quiet quitting as a “strategy for minimizing resource depletion,” wherein an employee “deliberately curtails their effort or makes no additional investment in their job”. In line with this, our participants who exhibited signs of burnout or cynicism were more likely to engage in quiet quitting, suggesting they pull back effort to protect their well-being. This supports the idea that quiet quitting is often a conscious boundary-setting behavior: employees do the bare minimum as a way to avoid further stress and exhaustion (Serenko 2024). This behavior reflects a ‘working to rule’ strategy and exemplifies ‘calibrated contributing’—a psychological contract response where employees rationally limit effort to avoid the personal costs of exceeding expectations amid uncertain. Our results reinforce this interpretation: quiet quitters in our sample were essentially disengaged employees preserving their energy, rather than malingerers. In fact, quiet quitting may help some workers avoid burnout in the short term, even if it means foregoing extra-role performance (Agarwal et al. 2024) This nuance is important because it challenges simplistic narratives that quiet quitters are merely “lazy” or lack work ethic; instead, many appear to be exhausted or disillusioned employees whose motivation has faltered.

On the other hand, we also considered the role of the organizational environment – the HRM system factors – in fostering quiet quitting. Prior commentary has speculated that quiet quitting is symptomatic of poor management practices or unmet expectations at work. For example, a human capital management analysis by Serenko (2023) found that employees often quiet quit due to “poor extrinsic motivation, burnout and grudges against their managers or organizations.” In our study, factors such as perceived unfairness, lack of growth opportunities, or weak supervisor support (analogous to HRM system gaps) did show an effect on quiet quitting intentions, but indirectly. The weaker influence of these factors in our model suggests that organizational shortcomings tend to trigger quiet quitting mainly when they undermine an employee’s personal motivation, hence, Hypothesis 3 (H3) which posited that burnout mediates the relationship between HRM gaps and quiet quitting is also supported. In other words, an inadequate HRM practice (for instance, not recognizing extra effort or a toxic boss) by itself may not immediately lead to quiet quitting unless it translates into the employee feeling demotivated, unvalued, or burned out. This interpretation bridges the two perspectives: the individual and organizational drivers of quiet quitting are interlinked. Our evidence indicates that quiet quitting is not simply a top-down failure of HRM nor purely a worker’s personal choice in a vacuum, but rather a phenomenon arising when external workplace issues erode internal motivation. This finding contributes to the theoretical conversation by highlighting the mediating role of employee motivation in the quiet quitting equation. It extends earlier research by empirically demonstrating that the quiet quitting trend, popularized in media as a reaction against hustle culture, in fact sits at the crossroads of motivation theory and HRM practice. We show that quiet quitting is deeply intertwined with concepts of work engagement, burnout, and psychological contracts. By doing so, our work refines the current understanding: quiet quitting represents a form of employee disengagement that is rooted in psychological self-preservation (consistent with conservation of resources theory) even as it may be triggered by organizational factors. This new evidence adds nuance to discussions of post-pandemic workforce behavior, suggesting that interventions to reduce quiet quitting must address how employees feel about their work, not just the policies on paper.

From a broader perspective, our study underlines why quiet quitting deserves attention in both research and practice. Employee disengagement is not a new problem, but quiet quitting has emerged as a stark reminder that a significant portion of the workforce may be emotionally checking out. Recent Gallup data alarmingly showed that at least 50% of the U.S. workforce could be categorized as “quiet quitters,” with employee engagement in 2022 dropping to its lowest level in a decade (Gallup, 2022). Such statistics highlight a widespread issue with potentially serious implications for productivity, innovation, and workplace morale across industries. By investigating quiet quitting through the dual lenses of individual motivation and HRM systems, our study contributes to the bigger picture of understanding workforce engagement in the modern era. It also resonates with the generational and societal shifts observed in the wake of COVID-19 – for instance, younger employees (Gen Z) are placing greater value on work-life balance and are quicker to disengage when work conditions feel unsustainable (Aggarwal et al. 2020). Therefore, our findings connect to a larger narrative: the pandemic and subsequent “Great Resignation” have catalyzed employees to re-evaluate their relationship with work. Quiet quitting can be seen as part of this Great Renegotiation of the employee-employer relationship, where workers assert new boundaries and priorities. Our research extends current knowledge by providing empirical evidence that personal well-being factors (like burnout) carry more weight in this renegotiation than previously confirmed. In doing so, we offer a new framework for thinking about quiet quitting – not as an aberration or solely a consequence of poor management, but as a signal of deeper misalignment between employees’ psychological needs and their work environment.

Implications for practice and policy: This study offers actionable guidance for organizations and policymakers seeking to address quiet quitting. If the phenomenon stems from motivational decline, the remedy lies in restoring employee engagement and well-being. Rather than treating quiet quitting as defiance, it should be seen as a signal—symptomatic of burnout, disengagement, or feeling undervalued.

We propose a multi-pronged strategy:

Prioritize well-being and prevent burnout: Wellness initiatives and manageable workloads help sustain energy and reduce withdrawal behaviors (Serenko 2024).

Reward extra effort fairly: Recognizing above-and-beyond contributions—via bonuses, praise, or advancement—reduces the incentive to disengage. Unrewarded effort leads employees to do only what’s required (Serenko 2024).

Foster meaningful work and growth: Purposeful roles and development opportunities enhance motivation and reduce quiet quitting tendencies (Agarwal et al. 2024).

Strengthen manager–employee relationships: Fair treatment and respectful communication build trust and voluntary effort. Interactional justice and safe feedback channels are key.

Normalize work-life balance: Encouraging boundaries and rest can boost engagement. Rather than viewing quiet quitters as disloyal, organizations should promote sustainable productivity.

These interventions target both individual and systemic drivers of disengagement. Ultimately, the goal is to cultivate “quiet thriving”—where employees contribute willingly, not out of obligation but genuine motivation. Managers should avoid punitive responses and instead treat quiet quitting as diagnostic feedback. Addressing root causes can elevate morale and performance.

Limitations and future research: While this study advances understanding of quiet quitting, several limitations warrant further exploration. First, the cross-sectional design restricts causal inference; longitudinal research could reveal how motivational decline or HRM improvements shape quiet quitting over time. Second, the construct itself remains emergent and variably defined—from minimal citizenship behavior to strict adherence to job roles. Future studies should refine its measurement, potentially using the Quiet Quitting Scale for consistency.

Our comparison of individual versus organizational factors did not fully explore their interaction. For instance, supportive HRM practices may buffer the effects of motivational decline (e.g., a caring manager might prevent disengagement). Investigating such moderating or mediating pathways—like psychological meaningfulness or availability—could deepen insight.

Demographic and cultural variations also merit attention. Younger versus older workers may quiet quit for different reasons, and manifestations may differ across industries or cultures. Early evidence suggests distinct patterns in collectivist societies and under varying economic conditions.

Finally, the long-term consequences of quiet quitting remain unclear. While it may offer short-term relief, sustained disengagement could erode innovation and citizenship behavior. Future research should assess interventions to re-engage quiet quitters and evaluate their effectiveness.

In conclusion, our findings suggest quiet quitting stems more from motivational erosion than HRM system flaws. This framing urges organizations to address both psychological states and management practices. By tackling root causes, leaders can foster a more engaged, resilient workforce and transform quiet quitting from a crisis into a catalyst for meaningful change.

6. Conclusions

This study set out to determine whether quiet quitting is best understood as a symptom of gaps in an organization’s HRM system or as a consequence of individual motivational decline. We revisited the research question by examining if shortcomings in HRM practices and support, versus waning employee motivation, better explain why employees disengage and restrict their effort. The results from testing Hypotheses 1 through 3 provide a clear answer. Consistent with expectations, we found that perceived HRM system gaps have some association with quiet quitting, and motivational decline (e.g., reduced enthusiasm and burnout) also shows a significant positive link with quiet quitting. In our model, both factors contributed to explaining the variance in quiet quitting behavior. The significant effects observed for H1 and H2 indicate that employees are more likely to “work to rule” and withhold extra effort when they perceive deficiencies in the organizational environment or when their personal drive and energy have deteriorated. Meanwhile, support for H3 confirmed that the interplay between HRM gaps and burnout is crucial: the influence of HRM system gaps on quiet quitting was largely channeled through declines in motivation. In other words, poor HRM practices erode employees’ motivation, which in turn prompts the withdrawal behavior captured by quiet quitting. Taken together, these findings suggest that our integrated model successfully addressed the research problem by showing that quiet quitting can be explained as a joint outcome of organizational shortcomings and diminishing employee motivation.

Our findings align well with theoretical expectations and recent research. The evidence that HRM system gaps (such as lack of support, unfair treatment, or unfulfilled expectations) drive quiet quitting is in line with studies emphasizing how managerial and organizational failures lead employees to scale back their engagement (Mahand and Caldwell 2023). This supports the view of quiet quitting as an employee response to unsatisfactory work conditions, akin to a reaction to psychological contract breaches or perceived injustice. Likewise, the strong relationship observed between motivational decline and quiet quitting is consistent with prior findings that burnout, stress, and lost enthusiasm prompt employees to withdraw discretionary effort (Geng et al. 2025). In fact, our results reinforce the notion that quiet quitting represents a form of self-protection or resource conservation when employees feel overextended or underappreciated (Hamouche et al. 2023). In sum, the pattern of results met our expectations: employees disengage quietly not simply out of laziness or generational attitude, but as an understandable consequence of unmet needs in their work environment and a deterioration of their inner drive. These outcomes confirm the central premise of our research question and affirm that the proposed model has effectively captured the underlying drivers of quiet quitting.

Despite mentioned limitations, our study offers valuable contributions to HRM theory and practice. Theoretically, it advances the understanding of quiet quitting by framing it as more than an isolated employee choice – instead, as a phenomenon deeply rooted in the employee–organization relationship. By empirically demonstrating that weak HRM systems (for example, inconsistent support or recognition) can erode employee motivation and lead to minimal engagement, we extend existing HRM and organizational behavior literature on employee withdrawal. The results integrate perspectives from motivational theory and HRM systems theory, showing that both extrinsic workplace factors and intrinsic motivational states jointly determine discretionary work behavior. This integration contributes a more holistic explanation of quiet quitting, bridging micro (individual motivation) and macro (organizational system) levels of analysis. From a practical standpoint, our findings send a clear message to HR professionals and managers: preventing quiet quitting requires closing the gaps in HRM systems as much as rekindling employees’ motivation. Organizations should invest in fair and supportive management practices – ensuring that employees feel heard, valued, and fairly rewarded – as these measures can foster the workplace support that discourages disengagement. At the same time, employers need to monitor and maintain employee well-being, addressing signs of burnout or cynicism before they translate into withdrawal. In line with emerging guidance in the HR field, our evidence suggests that re-engaging quiet quitters is not about chastising individual employees, but about fixing organizational inconsistencies and reenergizing the workforce (Serenko 2024). By highlighting the dual importance of organizational context and personal motivation, this study contributes a nuanced perspective that can help HRM practitioners design more effective interventions. Ultimately, recognizing quiet quitting as a symptom – and not merely a cause – of deeper issues enables both scholars and practitioners to focus on the root causes of disengagement, thereby improving employee experience and organizational performance in the long run.

References

- Alfes, K.; Shantz, A. D.; Truss, C.; Soane, E. C. The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement and employee behavior: A moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2013, 24, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, M.; Dağıstan, U. Quiet quitting: A new wine in an old bottle? Personnel Review 2024, 53(4), 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Kaur, P.; Budhwar, P. Silencing quiet quitting: Crafting a symphony of high-performance work systems and psychological conditions. Human Resource Management 2024, 64(3), 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A; et al. Gen Z entering the workforce: Restructuring HR policies and practices for fostering the task performance and organizational commitment. J. Public Affairs 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D. E.; Ostroff, C. Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review 2004, 29(2), 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands–Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2007, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J. A. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86(3), 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cropanzano, R.; Bowen, D. E.; Gilliland, S. W. The management of organizational justice. Academy of Management Perspectives 2007, 21(4), 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L.; Ryan, R. M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 2000, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, A.; Dowling, B.; Hancock, B.; Schaninger, B.; Sneader, K. The great attrition is making hiring harder. Are you searching the right talent pools? McKinsey Quarterly. 2022. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-great-attrition-is-making-hiring-harder.

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A. B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, A.; Vezyridis, P.; Glaveli, N. You Pretend to Pay Me; I Pretend to Work: A Multi-Level Exploration of Quiet Quitting in the Greek Context. Human Resource Management 2025, 64(4), 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. The quiet quitting scale: Development and initial validation. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10(4), 828–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.; Geng, X.; Geng, S. Identifying key antecedents of quiet quitting among nurses: A cross--profession meta--analytic review. In Journal of Advanced Nursing; Advance online publication, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M. Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology 2008, 93(1), 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. State of the Global Workplace: 2022 Report; Washington, DC; Gallup Press, 2022; Available online: https://lts-resource-page.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/2022-engagement.pdf.

- Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist 1989, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouche, S.; Koritos, C.; Papastathopoulos, A. Quiet quitting: Relationship with other concepts and implications for tourism and hospitality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2023, 35(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L. C. Commitment and quiet quitting: A qualitative longitudinal study. Human Resource Management 2025, 64(2), 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W. A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal 1990, 33(4), 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R. R.; Wright, P. M. The impact of high--performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Management 39 2013, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R. A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly 1979, 24(2), 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepak, D. P.; Snell, S. A. Examining the human resource architecture: The relationships among human capital, employment, and human resource configurations. Journal of Management 2002, 28(4), 517–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Lastres, B.; Karatepe, O. M.; Okumus, F. Combating quiet quitting: Implications for future research and practices for talent management. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 35 2023, e–publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W. B.; Leiter, M. P. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology 52 2001, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. E. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior 1981, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahand, T.; Caldwell, C. Quiet quitting – Causes and opportunities. Business and Management Research 2023, 12(1), 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M.; MacKenzie, S. B.; Lee, J. Y.; Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 2003, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness; Guilford Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S. L.; Rousseau, D. M. Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behavior 1994, 15(3), 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A. M. Caring human resource management and employee engagement. Human Resource Management Review 2022, 32(3), 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A. B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenko, A. Quiet quitting as a boundary-setting behavior: Implications for exhaustion and engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2024, 45(2), 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenko, A. The human capital management perspective on quiet quitting: Recommendations for employees, managers, and national policymakers. Journal of Knowledge Management 2023, 28(1), 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsemach, S.; Barth, A. Authentic leadership as a predictor of organizational citizenship behaviour and teachers’ burnout: What’s “quiet quitting” got to do with it? Educational Management Administration & Leadership. Advance online publication 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P. M.; Nishii, L. H. Strategic HRM and organizational behavior: Integrating multiple levels of analysis. In The Oxford handbook of organizational climate and culture; 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wayne, S. J.; Glibkowski, B. C.; Bravo, J. The impact of psychological contract breach on work-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology 2007, 60(3), 647–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).