3.1. Magnetic Field Shaping

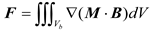

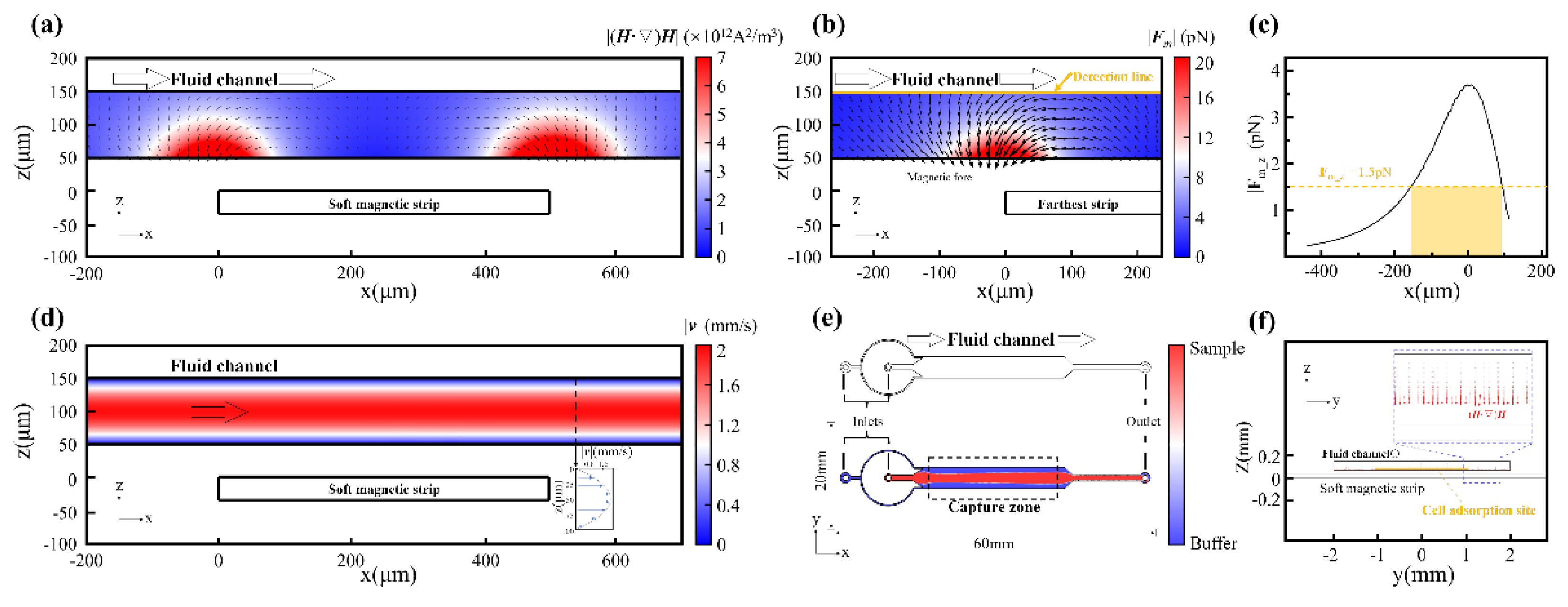

When a soft magnetic element is strategically positioned within an external magnetic field, it becomes magnetized and dramatically distorts the field lines in its immediate vicinity. This magnetization phenomenon results in a pronounced intensification of the magnetic flux density near the material's boundaries, as elegantly visualized in

Figure 1a, where field lines become focused and compressed near the strip edges. In our comprehensive simulations and experimental investigations, we employed 1J85 Nickel-Iron soft magnetic alloy as the magnetic field sculpting module, characterized by an initial permeability of 80,000 and a maximum permeability of 200,000. On a macroscopic level, this behavior effectively channels magnetic flux through the soft magnetic domains, producing magnetic field convergence and establishing localized regions of sharply elevated magnetic field gradients, often surpassing 2,000 T/m at a distance of 50 μm (

Figure 1b). We define this phenomenon as magnetic field sculpting, a cornerstone principle underlying the MagSculptor platform. Through meticulous engineering of the geometry and spatial arrangement of soft magnetic strips, the magnetic field topology within the microchannel can be precisely orchestrated and tailored to specific applications.

Similar to conventional permanent magnets, the field-shaping efficacy of soft magnetic elements diminishes progressively with distance. Both magnetic flux density (|

B|) and its gradient (|∇·

B|) exhibit rapid attenuation as one moves away from the magnetic source (

Figure 1c). While the magnetic flux density gradient can reach an impressive 18,000 T/m at a distance of 10 μm from the soft magnetic strip, the imperative to ensure manufacturing stability and process reliability between the flow channel and soft magnetic materials necessitates the adoption of a 50 μm spacing in this study, corresponding to a magnetic flux density gradient of 2,000 T/m. In the sophisticated realm of magnetic particle manipulation, the induced dipole moments experience translational forces within gradient fields, the magnitude and directionality of which are intricate functions of both field strength and spatial gradient. Consequently, achieving precise control over magnetic forces within the microchannel environment demands rigorous field shaping protocols, establishing a critical design constraint that fundamentally governs the MagSculptor system architecture.

3.2. Microfluidic Design and Magnetic Field Coupling

In conventional magnetic cell sorting workflows, bead-labelled cells become magnetically responsive through antibody-mediated attachment of superparamagnetic Dynabeads, with the degree of labelling correlating quantitatively with the expression level of target surface proteins [

31]. For subtypes with low biomarker expression, the magnetic response is inherently weak; thus, local amplification of magnetic forces within the microchannel is essential to achieve differential sorting.

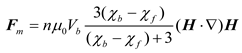

To address this, we designed an array of soft magnetic strips that are magnetized by a side-mounted, tunable electromagnet (

Figure 1d). The spatial gradient between each strip and the external magnetic source results in a non-uniform magnetic landscape along the channel axis, where each strip locally generates a distinct magnetic force well (

Figure 1e). When integrated with the microfluidic flow environment, this magnetic architecture enables the stepwise deflection and capture of magnetically labelled cells based on bead load, functioning akin to a graded hurdle race: cells with higher magnetic content are captured earlier, while lightly labelled or unlabeled cells transit further downstream.

Within a planar Cartesian coordinate system, the primary cell transit direction was designated as the x-axis, with 27 parallel strips spanning x ∈ [0,27] mm. We adjusted the electromagnet current to achieve a magnetization intensity of 1.44 T (approximating the magnetic performance of N52 permanent magnets), positioning the strongest soft magnetic strip at 18 mm from the electromagnet as the starting point (with the magnet surface located at x = 45 mm). In the vertical dimension, the electromagnet central axis was aligned coplanarly with the soft magnetic strip array. Finite element simulations confirm that the field amplification effect of the soft magnetic strips reaches desired efficacy within 50 μm above the strip surface, corresponding precisely to the vertical center of the microchannel (

Figure 1f). In this critical region, sharp magnetic flux peaks emerge near strip boundaries, forming localized high-gradient capture zones. These gradients are indispensable for achieving subtype resolution among cells differing by only a few magnetic beads—a capability that distinguishes this approach from conventional magnetic separation techniques.

The effectiveness of this design is further validated through comprehensive spatial mapping of the magnetic flux density and gradient profiles under operational field strengths (

Figure 1g). From x = 27 mm to x = 0 mm, the background magnetic field, which would otherwise decay gradually from 35 mT to 9 mT, undergoes dramatic field sculpting that introduces significant oscillations, creating localized magnetic flux density peaks with corresponding boundary-localized high gradients. This engineered magnetic architecture facilitates enhanced magnetization and capture of magnetic beads through precisely controlled field topology. We designated this device "MagSculptor" to emphasize its core functionality: the precise "sculpting" of magnetic fields through engineered soft magnetic strip arrays—a paradigm that transforms conventional uniform field approaches into spatially sophisticated magnetic landscapes.

During magnetic field modulation, the adsorption force experienced by magnetic beads is jointly determined by both magnetic flux density and its gradient. Therefore, in channel design, the boundary regions of each enhancement peak should serve as the primary adsorption sites for cellular capture.

To accurately characterize the forces acting on bead-labelled cells within the MagSculptor system, we performed finite element simulations coupling the magnetic and hydrodynamic fields. In a gradient magnetic field, superparamagnetic particles are first magnetized and then subjected to a net translational force, described as proportional to the field-dependent quantity (

H·∇)

H as shown in Equation (2). This scalar-vector product in

Figure 2a captures the spatial variation of the magnetic field and reflects the relative force landscape experienced by a particle of fixed magnetic susceptibility.

Within individual flow channels, under identical magnetic field conditions, we systematically performed independent sequential runs of four different cell lines for gradient capture and elution procedures (n=3 for each condition). This experimental design enabled comprehensive characterization while preserving in situ photographic scanning profiles for spatial analysis, and simultaneously retained fractionated cell populations for subsequent quantitative statistical analysis and validation studies.

3.3. Magneto-Hydrodynamic Simulation and Cell Capture Dynamics

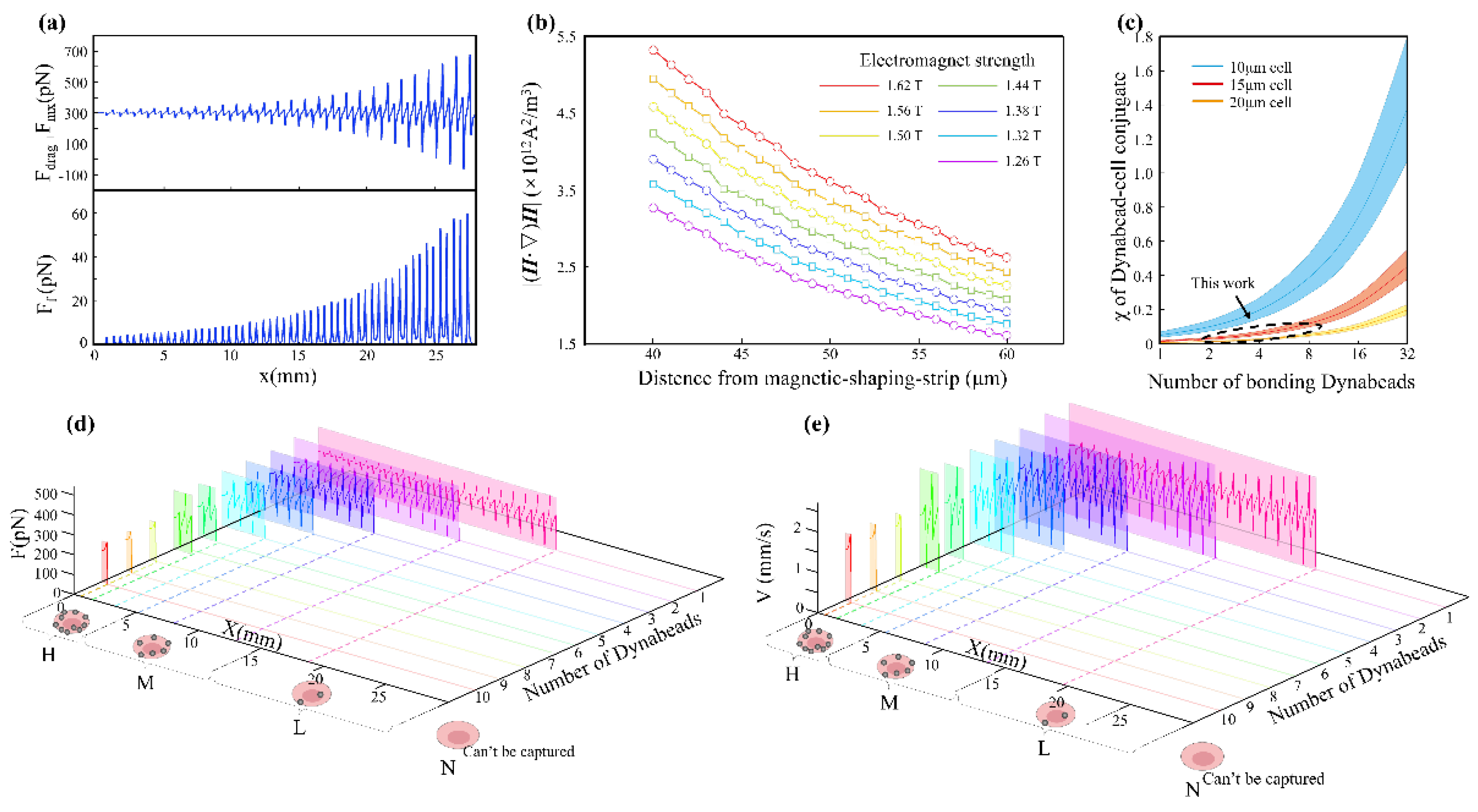

Heatmap visualizations of (H·∇)H reveal that each soft magnetic strip generates a pair of localized force maxima near its lateral edges, aligning with the high-gradient zones predicted by analytical modelling. In this framework, the vertical component of the magnetic force is particularly critical, as it draws magnetically labelled cells downward toward the strip surface, enabling effective capture. The strength of this vertical force component varies with both bead load and local field topology, and thus governs the onset of physical interaction between cells and the substrate.

To assess the capture reliability under worst-case conditions, we modelled the trajectory of a 20 µm-diameter cell conjugated with a single 2.8 µm magnetic bead as shown in

Figure 2b. Even along the minimal-force detection line, identified as the least favorable streamline in the magnetic force field, simulations showed that the cell is consistently deflected toward the bottom of the channel before reaching the capture threshold.

Figure 2c observation confirms that even weakly labelled cells are physically drawn toward capture sites under realistic flow and field conditions.

We further evaluated the hydrodynamic behavior of the flow field within the microchannel. Simulations confirmed the establishment of a laminar Poiseuille flow profile, with parabolic velocity distribution along the channel height and uniform axial flow along its length (

Figure 2d). To suppress boundary-induced velocity variability and ensure that cells remain within the optimal capture zone, sheath flows were introduced, hydrodynamically focusing all cells into the central 50 µm zone above the strip array (

Figure 2e,f).

Furthermore, we incorporated dynamic mechanical interactions into the simulation to evaluate the interplay of magnetic forces, hydrodynamic drag, and substrate friction. Time-dependent Eulerian analysis showed that while magnetic and frictional forces remain stable across spatial positions, drag force varies as a function of both velocity and z-position. This highlights the necessity of optimizing flow confinement to minimize vertical variability.

To deepen our understanding of cell sorting dynamics within MagSculptor, we performed parametric analyses of both magnetic field conditions and cell–bead interactions. Our experimental design incorporated a microchannel with a width of 4 mm, height of 100 μm, and a total sorting zone length of 27 mm. The horizontal and vertical components of the magnetic force, derived from the spatial gradient of the field, were analyzed separately to elucidate their respective roles in capture dynamics (

Figure 3a).

The vertical component determines the contact stability between a bead-labelled cell and the substrate. Once a sufficient downward magnetic force is exerted, frictional interaction dominates and regulates axial migration. The coefficient of dynamic friction in aqueous environments, assumed between 0.05–0.15, is sufficient to ensure that captured cells are gradually slowed and immobilized near the strip surface. In contrast, the horizontal force component exhibits oscillatory behavior across the strip boundary, which can induce micro-accelerations or decelerations of partially captured cells.

To enable robust system calibration, we systematically varied the strength of the electromagnet and recorded corresponding field profiles at defined channel heights. Simulation results indicate that increasing the magnetic field compensates for larger vertical distances between the soft magnetic strips and the microchannel (

Figure 3b). This tunability allows for precise alignment between magnetic peaks and the capture zone, even in the presence of fabrication-induced channel height deviations. When cells and their bonded magnetic beads are considered as integrated entities, the magnetic characteristics of these conjugates vary with magnetic bead content. Comparatively, larger cell volumes result in reduced magnetic errors caused by cellular volume variations. From a statistical perspective, cancer cells possess larger average dimensions than normal cells, potentially yielding superior results in gradient capture chips.

Multiple studies have reported significant variations in cell size measurements for identical cell types; however, MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and A549 cells consistently demonstrate dimensions within the 15 ± 3 μm range [

32,

33,

34], while Caco-2 cells exhibit larger sizes with broader size distributions [

35,

36,

37]. Although Caco-2 cells present substantial size variability around 20 μm, for these larger cells, the influence of magnetic bead content on the magnetic properties of the cell-bead conjugate becomes attenuated (

Figure 3c). This phenomenon serendipitously enables predictable trajectory modeling for Caco-2 cells despite their heterogeneous size distribution. Kinematic simulations must encompass the full spectrum of cell sizes ranging from 15 μm to 20 μm to ensure comprehensive predictive accuracy.

The terminal state of cells within the microchannel involves stationary positioning at specific locations, with forces determined by fluid drag, magnetic forces, and friction. The resultant force components along the direction of motion at various positions within the fluid can be represented as line diagrams (

Figure 3d), with positions where horizontal net force equals zero indicating stable stationary cell positions. Capture trajectories for cells with nominal 20 μm dimensions were also modeled computationally, specifically accommodating larger cells such as Caco-2 (Figure S1a). The ultimate objective of mechanical analysis is to dynamically describe the motion behavior of various cell subtypes within the MagSculptor. We integrated spatial flow field and magnetic field parameters, combined with inlet and outlet boundary conditions of the channel, and employed the forward Euler method to complete time-stepping calculations (dt=1E-5 s) with state variable updates, ultimately obtaining the motion processes of various cell subtypes within the channel. We selected velocity-displacement variation data for different cell types to generate plots (

Figure 3e). When cells reach magnetic capture potential barriers, they experience velocity changes under the influence of magnetic and frictional forces, leading to increased velocity differences between cells and fluid, with alternating acceleration and deceleration creating oscillatory velocity effects that intensify with progressively stronger barriers, resulting in increasingly larger amplitudes until velocity reaches zero, marking the cell capture position.

For Caco-2 cells, which possess characteristically larger average volumes, we employed 20 μm diameter parameters to simulate the anticipated sorting dynamics for this cellular population. Given that the increased cellular volume effectively dilutes the magnetic influence of individual beads, these larger cells consistently demonstrate capture sites with a pronounced lag of 2-3 strip positions relative to their smaller counterparts (Figure S1b). This size-dependent capture behavior reflects the fundamental relationship between cellular volume and magnetic susceptibility, where larger cells require proportionally higher magnetic bead densities to achieve equivalent capture efficiency within the engineered magnetic gradient landscape.

By correlating magnetic bead conjugation levels with capture positions, cell subtype grouping can be achieved, with phenotypic classification from high to low designated as H (High), M (Medium), L (Low), and uncaptured N (Negative) groups. Dynamic capture positions correspond closely to static equilibrium positions but exhibit slight discrepancies; specifically, dynamic capture position analysis accounts for cellular motion inertia, resulting in predictable positional lag. However, analysis reveals that the inertial influence on capture positions does not extend across the entire strip, thereby preserving predictive accuracy.

From simulation results, the combined magnetic–hydrodynamic field structure in MagSculptor ensures robust separation performance with subpopulation-level resolution. We can theoretically predict the expected capture locations for cell-bead conjugates of varying sizes and different magnetic bead loadings, providing invaluable theoretical guidance and design support for experimental implementation and optimization strategies.

3.4. Subtype Isolation of Cells

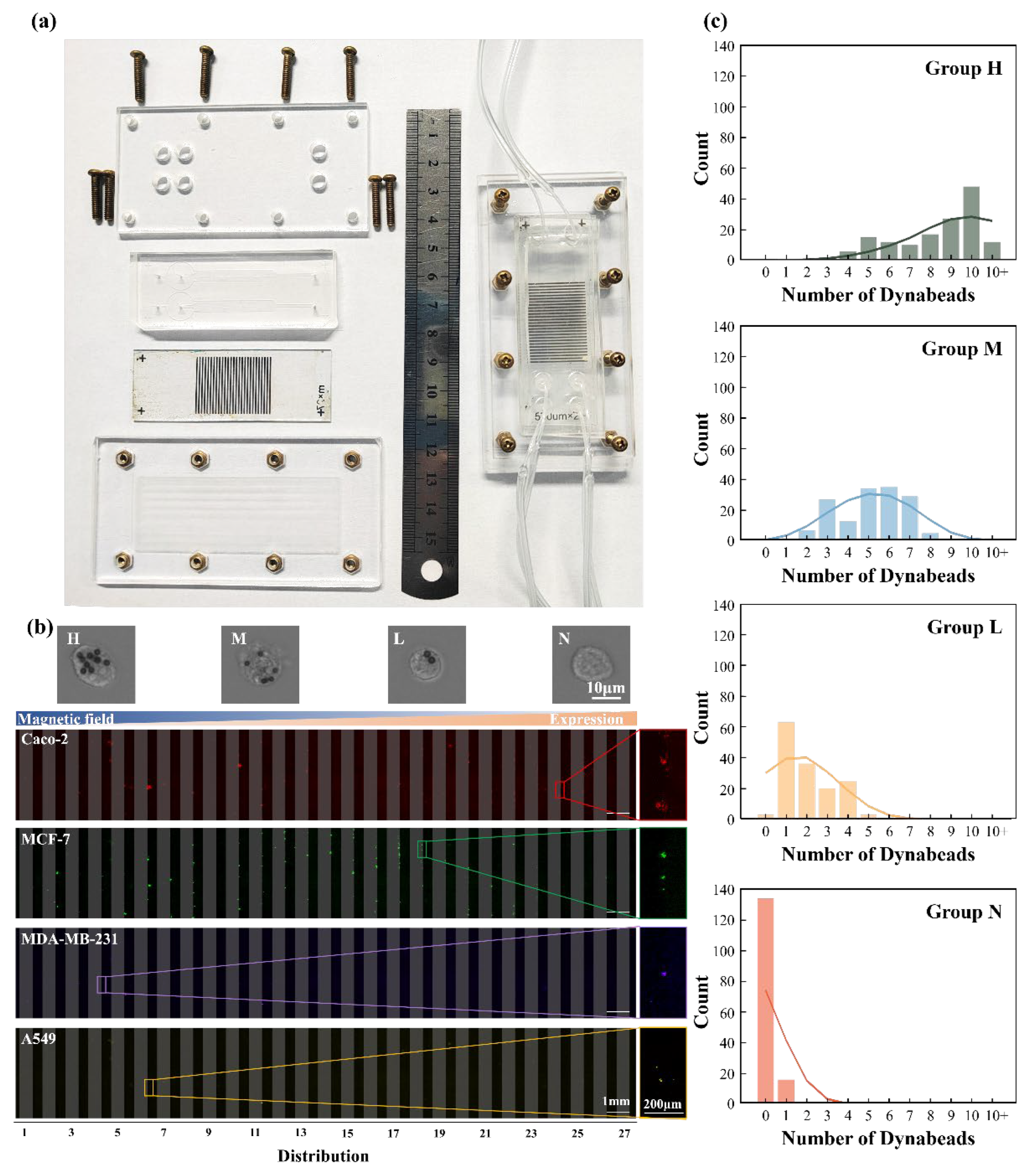

To physically realize the MagSculptor platform, we constructed a modular device composed of three primary components: (i) an etched glass substrate patterned with an array of amorphous soft magnetic strips, (ii) a multilayer polycarbonate-based microchannel bonded atop the magnetic array, and (iii) top and bottom acrylic support plates for compression sealing. The device was assembled using a bolt-and-nut fixture system to ensure robust structural alignment and leak-free fluidic operation (

Figure 4a). We incorporated two identical parallel channels to demonstrate the high-efficiency operational capabilities of the parallel flow architecture.

To evaluate the functional performance of the system, we performed subtype separation experiments using four commonly studied epithelial cancer cell lines: Caco-2, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and A549, with a total cell population of approximately 1,000 cells per experimental run. During the separation process, magnetically labeled cells were differentiated based on their bead loading and displayed in capture profiles, ultimately being sorted into H, M, and L groups, while uncaptured cells were collected in the N group. The surface-bound magnetic bead numbers transitioned from approximately 10 beads per cell in the H group to zero beads in the N group (

Figure 4b). Magnetic microbeads functionalized with anti-EpCAM antibodies were incubated with each cell type, enabling selective labelling via antigen–antibody recognition. The labelled cells were then introduced into the MagSculptor system under continuous flow conditions, each exhibiting distinct levels of EpCAM membrane expression. The subtype distribution results revealed statistically significant differences in EpCAM expression levels among the cell lines, which aligned with established understanding of these cellular phenotypes. Caco-2 cells demonstrated the highest phenotypic expression, followed sequentially by MCF-7 cells, MDA-MB-231 cells, and A549 cells, which exhibited the lowest expression levels (Figure S2) [

38,

39,

40].

Following separation, cell positions within the microchannel were visualized using fluorescence microscopy, with each cell line labelled using a distinct fluorescent dye for identification. A pseudo-color mapping scheme was employed to distinguish the four populations, allowing precise positional analysis of cells relative to the magnetic strip array. The progressive magnetic gradient from strip 1 to strip 27 effectively partitioned cells based on their bead load, with strongly labelled cells retained in earlier regions and weakly labelled cells appearing near the outlet.

By partitioning the populations into H, M, and L groups based on strips 1-9, 10-18, and 19-27 respectively, we achieved distribution patterns corresponding to the expected magnetic bead conjugation levels of 10-6, 5-3, and 1-2 beads per cell as predicted in

Figure 3e. Even unlabeled cells were successfully collected in the negative collection group (N group), with the four sorted populations accounting for 96.4 ± 1.1% (n=3) of the initial cell input. This slight reduction in collection efficiency was attributed to unavoidable cellular aggregation and mortality issues that inherently limit separation operational recovery rates.

Due to antigen site occupancy following magnetic bead conjugation, subsequent flow cytometric validation presented technical challenges. To characterize separation efficacy, we performed quantitative analysis of bead occupancy on each sorted subpopulation: H, M, L, and N, by imaging captured cells and systematically counting bead numbers on their surfaces. We randomly selected 150 cells from each group and analyzed the magnetic bead content within these cellular populations. Statistical comparisons confirmed significant differences in bead load between subtypes (

Figure 4c). Macroscopic statistical patterns demonstrated progressively decreasing magnetic bead conjugation from H to N groups; however, due to cellular size variations affecting hydrodynamic drag forces and consequently influencing cellular distribution, experimental capture results exhibited significantly broader bead content distribution ranges compared to simulation predictions. This discrepancy represents a potential area for future optimization in related research endeavors.

Furthermore, we conducted parallel experiments targeting low-phenotype cell subtype sorting to benchmark against flow cytometry performance. Results demonstrated that for high EpCAM-expressing MCF-7 cells, flow cytometry, which employs fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) technology, could effectively identify significant differences between positive cells and negative control groups. However, for MDA-MB-231 cells with lower EpCAM phenotypic expression, the intrinsic cellular autofluorescence exhibited excessive similarity to fluorescent antibody-labeled cell populations, making positive-negative discrimination challenging and rendering effective cell sorting nearly impossible (Figure S3). In contrast, our magnetic separation approach for identical batches of MDA-MB-231 cells not only distinguished between negative and positive control groups but also achieved further subpopulation separation within positive cohorts. In reproducibility experiments, we observed cell viability rates (n=3) exceeding 95% across all groups (Figure S4). Notably, no statistically significant difference in cell viability was observed between pre-sorted and post-sorted groups (p > 0.05), suggesting that the sorting process did not adversely affect cell viability—thereby providing enhanced potential for downstream biological research applications.

To evaluate the clinical detection potential of MagSculptor under complex backgrounds, we prepared four independent 4 mL aliquots of whole blood, each spiked with approximately 100, 1,000, 10,000, or 100,000 MDA-MB-231 cells. All samples were incubated with anti-EpCAM magnetic beads at a concentration of 1.2–1.4 × 106 beads/mL for 30 min at room temperature. Given the viscosity differences between whole blood and cell culture medium, as well as the influence of high-density erythrocytes on hydrodynamic drag forces, we ultimately maintained sample throughput at 2,500 μL/h with buffer flow at 800 μL/h, successfully achieving subtype gradient capture of cancer cells from whole blood (Figure S5). Since the spiked MDA-MB-231 cells were not entirely positive, negative cells that failed to conjugate with magnetic beads remained within the whole blood matrix. According to capture enumeration results, approximately 22.4-35.6% (n=4) of the MDA-MB-231 cells spiked into whole blood demonstrated EpCAM positivity. Captured cells in the separation profiles existed as individual entities, and even under low-concentration conditions (<25 cells/mL), single-cell-scale capture and observation were achievable within whole blood samples. More comprehensive clinical validation and applications surrounding this platform warrant further investigation and development.