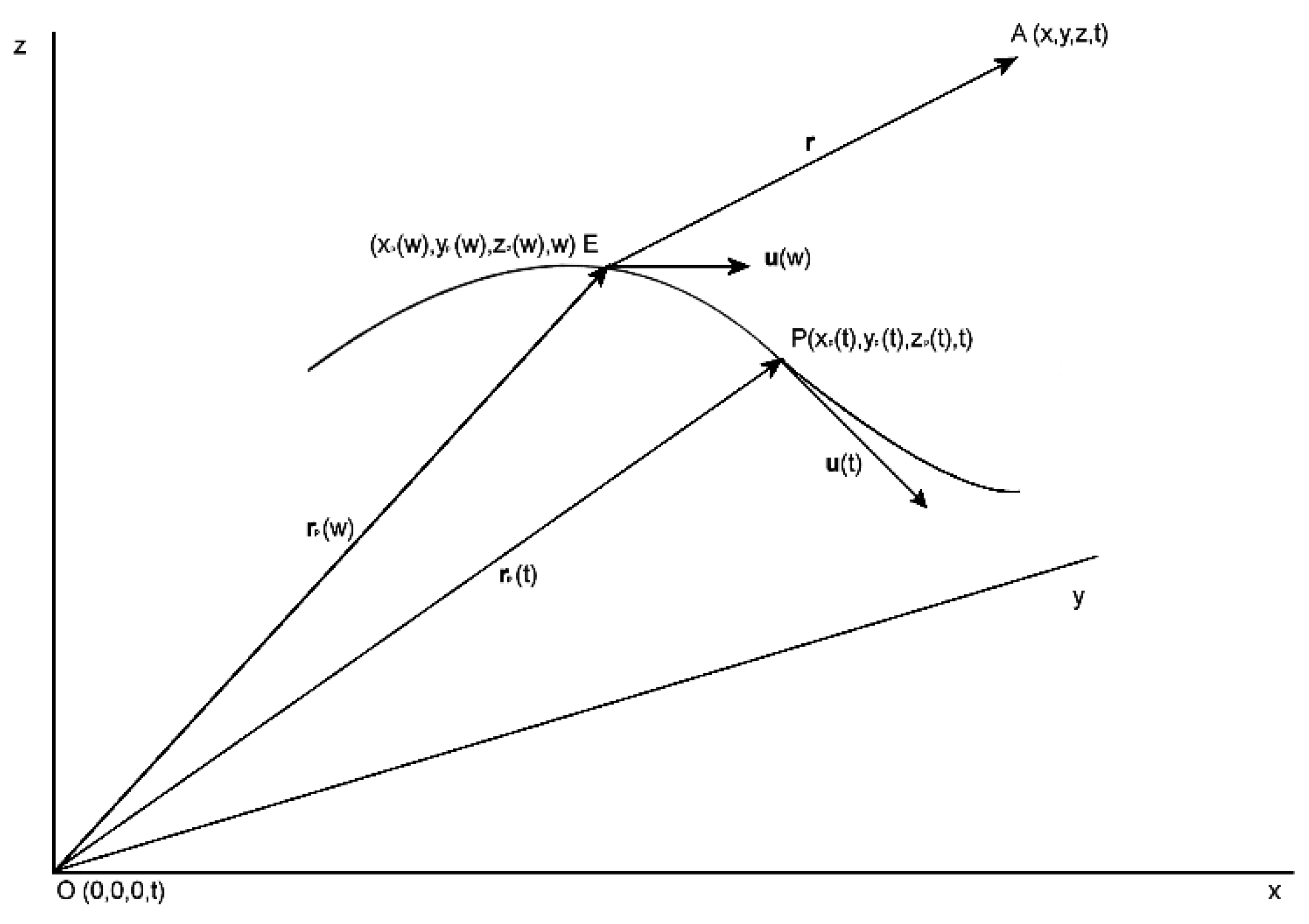

In this chapter, we explore the cosmological implications of the self-variation principle. According to the theory, the rest mass and electric charge of a particle (more generally, its self-varying charge) appear smaller in cosmological-scale observations than their corresponding values measured in the laboratory on Earth. This has significant consequences for all physical phenomena in distant astronomical objects that depend on these fundamental quantities. These effects are imprinted in observational cosmological data. One prominent manifestation is the redshift of distant astronomical sources.

Many fundamental quantities in astrophysics depend on redshift. As a function of redshift, we compute: the electron mass (and more generally, the masses of fundamental particles), the ionization energy and the degree of ionization of atoms, the Thomson and Klein–Nishina scattering coefficients, the position–momentum uncertainty and the Bohr radius, as well as the energy released in nuclear reactions and hydrogen fusion.

One of the more striking implications is that, due to the self-variation of rest mass, gravity does not have cosmological-scale consequences: it is neither responsible for the expansion nor for any potential collapse of the universe. Gravitational effects are instead confined to smaller-scale structures, such as galaxies and clusters.

By contrast, the origin and evolution of the universe as described by the Self-Variation Theory shows remarkable agreement with cosmological observations, offering a coherent and natural explanation for phenomena that remain puzzling under the standard model.

5.2. The Redshift of the Distant Astronomical Objects

The fine structure constant is defined as

, (5.14)

where is the electric charge of the electron. From Equation (5.11) if the charge of electron we obtain,

. (5.15)

The energy of the electron in the atom is

where

is the rest mass and

is the electric charge of the electron,

is the atomic number and

is Coulomb’s constant [

75,

82]. The wavelength

inversely proportional to the photon energy

,

[

74]. Therefore, the wave length

of the linear spectrum is inversely proportional to the factor

. If we denote by

the wavelength of a photon emitted by an atom “now” on Earth, in the laboratory and by

the same wavelength of the same atom received “now” on Earth from the far-distant astronomical object, the following relation holds,

and from Equations (5.8) and (5.11) if

the charge and

the rest mass of electron we obtain,

. (5.16)

From Equation (5.16) we have for the redshift ,

of the astronomical object that

. (5.17)

From Equations (5.15) and (5.17) we get,

. (5.18)

The increase of rest mass to over time is given by Equation (2.31). Considering that the electric charge of the electron contributes a small percentage to its total rest mass, we conclude that in Equations (2.31) and (2.33) is,

. If we assume that in the same particle the constant

is the same for rest mass and electric charge, then then we conclude that the charge

of the electron increases at a much lower rate, compared to the rate of increase of its rest mass

. This conclusion is confirmed by the cosmological data [

52,

73]. Considering that the electric charge of the electron increases at a much slower rate than its rest mass, from Equation (5.18) we get,

and equivalently we obtain,

. (5.19)

For small distances , from Equation (5.19) we get,

and comparing this Equation with Hubble’s law

[

50] we get,

, (5.20)

where is the Hubble constant for the linear spectrum of atoms. If the measurements we make depend on the ΄΄heavy΄΄ particles, such as the proton and neutron, Equation (5.20) becomes,

. (5.21)

The Self-Variation Theory predicts the measurement of at least two values of the Hubble constant [

67,

69]. On the cosmological scale, the self-variation of the electron and the heavy particles correspond to different values of Hubble’s constant.

Taking into account that , and , from Equation (5.20) we get,

From Equation (5.10) we get,

and taking into account that

we obtain,

. (5.22)

From this inequality and considering the possible values of redshift we conclude that,

. (5.23)

The limit (5.23) implies that we can go far back into the past, giving increasingly large values of redshift . The Self-Variation Theory Equations on the cosmological scale are compatible with extremely large values of redshift.

From Equation (5.20) we get,

and with Equation (5.9) we get,

and with Equation (5.20) we get,

. (5.24)

From this Equation and limit (5.23) we conclude that Hubble’s constant increases slightly with time. Considering that , the rate of change of Hubble’s constant is equal to its square, . In the context of Self-Variation Theory the Hubble constant is a variable parameter which increases over time, at an extremely slow rate. The same slight increase with time is also predicted for the redshift, for a specific distant astronomical object, which is at a distance . From Equations (5.19) and (5.9) we get,

. (5.25)

From Equation (5.19) we get,

. (5.26)

This Equation gives the distance of a distant astronomical object as a function of redshift . To measure cosmological-scale distances through the redshift requires the measurement of the constant and the parameter . Today we precisely measure the value of the Hubble constant . We also know the possible values of the parameter , as given by the limit (5.23) . Thus we can calculate the possible values of the constant from Equation (5.20).

5.10. A Comparison of the Cosmological Predictions of Self-Variation Theory Versus the Standard Cosmological Model, Based on the Cosmological Data

In this Section we compare the predictions of the Standard Cosmological Model and the Self-Variation Cosmological Model, based the fourteen main cosmological data. The interpretation of physical reality, the physical world, is based on the available Theories of Physics. This also applies to the cosmological data. We could say that the Standard Cosmological Model is based on twentieth century Theories of physics. However, this is not accurate. Theories of the twentieth century, by themselves, do not justify the cosmological facts. Their justification requires a series of additional assumptions which do not follow from the Theory but have been introduced into the Standard Cosmological Model in order to bring it into agreement with the cosmological data. The Dark Matter hypothesis was made to make twentieth-century theories of gravity compatible with observational data on large structures of matter, galaxies and galaxy clusters. Despite decades of effort, and the large quantity required to play the role attributed to it, so far no Dark Matter particles have been observed. The inflation hypothesis is not self-consistent and the length of time it is assumed to have lasted is arbitrary. The Dark Energy hypothesis was made under the weight of observational data. Measurements of cosmological-scale distances via Type Ia supernovae were made to confirm the slowing rate of expansion of the universe, as predicted by twentieth-century theories of gravity. The measurements gave the opposite results. Dark Energy was a still needed addition to the theoretical background of the Standard Cosmological Model. The observed flatness of the universe and the two measured values of Hubble’s constant are completely incompatible with the Standard Cosmological Model.

The Self-Variation Theory reasons cosmological data as a consequence of the self-variation of fundamental particles. The cosmological facts result from the combination of the three principles of the Theory and no additional hypothesis is required. Equations (5.27), (5.36), (5.38), (5.33), (5.40), (5.42) and (5.28) give seven astrophysical parameters as a function of redshift . These parameters are the mass of the electron and in general the mass of the fundamental particles, the ionization energy and the degree of ionization of the atoms, the Thomson and Klein-Nishina scattering coefficients, the position-momentum uncertainty and the Bohr radius , and the energy produced in nuclear reactions and hydrogen fusion,

These equations predict the observed cosmological data, with the sole exception of the variation of the fine-structure constant, which is specifically addressed by Equation (5.11). The implications of the redshift-dependence of the astrophysical parameters are found to be in complete agreement with all currently available cosmological observations. This agreement is by no means self-evident. In principle, a parameter—or a combination of parameters—varying with redshift could lead to discrepancies with the data. In such a case, the validity of the Self-Variation Theory would be called into question.

It is important to emphasize that the Self-Variation Theory, being axiomatically constructed, does not permit the introduction of ad hoc assumptions external to its foundational framework in order to reconcile its predictions with observations. Apart from the three core principles on which it is based, the theory introduces no further hypotheses to achieve consistency with cosmological data. All resulting conclusions arise strictly from the mathematical consequences of these foundational principles.

In what follows, we present a detailed comparison between the predictions of the two models, with respect to each of the fourteen principal cosmological observables.

5.10.1. Origin of the Universe

The justification for the redshift also determines the predictions of a Cosmological Model for the origin and evolution of the universe. The different justification of the redshift by the Standard Cosmological Model (expansion of the universe, macroscopic cause) and by the Self-Variation Theory (self-variation of material particles, microscopic cause) lead to completely different predictions about the origin and evolution of the universe.

Going back in time, in the distant past the Standard Cosmological Model predicts the Big Bang as the beginning of the universe. The same prediction is made by the related Cosmological Models which justify the red shift through the expansion of the universe. The Self-Variation Theory predicts as the beginning of the universe a completely different state, the Vacuum State. In the distant past, the early universe differed little or not at all from the vacuum.

In summary, the justification given by each Model for the origin of the universe is as follows.

Standard Cosmological Model; Big Bang.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model; Vacuum State.

5.10.2. Redshift

The phenomenon of cosmological redshift has played a pivotal role in shaping our understanding of the universe. Beginning in 1912, Vesto Slipher was the first to observe that most spiral galaxies exhibit redshifted spectra—an observation that would later underpin fundamental cosmological theories [

70]. Edwin Hubble, studying redshift with Milton Humason, established a correlation between a galaxy’s redshift and its distance from Earth—a relationship that laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the Standard Cosmological Model [

50].

However, Hubble himself remained cautious in interpreting the physical significance of redshift. In a 1931 letter to Willem de Sitter, Hubble wrote:

“Mr. Humason and I are both deeply sensible of your gracious appreciation of the papers on velocities and distances of nebulae. We use the term ‘apparent’ velocities to emphasize the empirical features of the correlation. The interpretation, we feel, should be left to you and the very few others who are competent to discuss the matter with authority.”

This cautious tone was not a passing sentiment. As Allan Sandage later emphasized, Hubble maintained a degree of skepticism about the expanding-universe interpretation until the end of his life:

“…To the very end of his writings, he maintained this position, favouring (or at the very least keeping open) the model where no true expansion exists, and therefore that the redshift represents a hitherto unrecognized principle of nature.”

This “unrecognized principle” alluded to by Hubble may find a theoretical framework in the Self-Variation Theory (SVT). According to SVT, the redshift observed in distant astronomical objects could stem from a microscopic cause—namely, the gradual self-variation of the electron’s rest mass over cosmological time.

Traditional interpretations, embedded in the framework of General Relativity and Big Bang cosmology, attribute redshift to the expansion of spacetime itself [

1,

55,

71]. Yet, the electromagnetic spectrum of atoms—particularly the hydrogen atom—is determined by fundamental constants: the electron’s rest mass and electric charge, the electric permittivity of free space, the speed of light in a vacuum, and Planck’s constant. A systematic variation in one or more of these constants, particularly the rest mass of the electron, could also produce the observed spectral shifts, even in a non-expanding (static) universe.

Despite the knowledge of these dependencies [

75,

82], the possibility that redshift arises from a time-evolving electron mass—or any microscopic variation in physical constants—was not seriously pursued during the 20

th century. The dominant narrative has focused almost exclusively on macroscopic explanations, sidelining potentially viable microscopic mechanisms.

SVT challenges this orthodoxy by proposing that redshift may not be evidence of spatial expansion, but rather a signature of temporal evolution in fundamental particle properties. In this light, the redshift becomes a record of physical change over time, imprinted in the spectra of distant objects.

If the predictions of SVT hold, they may provide the theoretical foundation for the “unrecognized principle” that Hubble suspected. This reinterpretation not only revisits the original ambiguity in Hubble’s stance but also opens a new line of inquiry into the nature of cosmic evolution—one that does not necessitate the expansion of the universe, but instead posits a dynamic microphysical substrate.

Summary of Redshift Interpretation in Competing Cosmological Models:

The interpretation of cosmological redshift differs fundamentally between the Standard Cosmological Model and the Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

Standard Cosmological Model:

Redshift is interpreted as a direct consequence of the expansion of the universe. As space itself stretches over time, the wavelengths of photons traveling through it are elongated, resulting in the observed redshift of light from distant galaxies.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM):

Redshift is attributed to the self-variation of the electron’s rest mass over cosmological time. In this framework, the electron had a significantly lower rest mass in the distant past (corresponding to higher redshift values), which led to lower atomic transition energies. Consequently, the light emitted by atoms in the early universe appears redshifted when observed today, not because of spatial expansion, but due to intrinsic microscopic evolution in fundamental constants.

5.10.3. Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation

The Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation (CMBR) refers to a faint, nearly isotropic background radiation that fills all of space and reaches Earth uniformly from every direction. It has been firmly established that this radiation does not originate from stars, galaxies, or other discrete astronomical objects. Its spectral energy distribution peaks in the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum, and its accidental discovery by Penzias and Wilson in 1964 [

54,

65] played a pivotal role in confirming and popularizing the Standard Cosmological Model (SCM).

In the context of the SCM, the CMBR is interpreted as a remnant of the Big Bang—the “afterglow” of the primordial fireball. The early universe is thought to have existed as a hot, dense plasma primarily composed of ionized hydrogen. Due to high energy and ionization, Thomson scattering dominated photon interactions, making the universe opaque to radiation. As the universe expanded and cooled, it reached a critical temperature (~3000 K) where protons and electrons could recombine to form neutral hydrogen atoms. This phase, known as the recombination period, occurred roughly 379,000 years after the Big Bang. After recombination, photons could propagate freely without scattering—this is referred to as photon decoupling. These freely streaming photons are now observed as the CMBR, redshifted to an effective blackbody temperature of ~2.73 K.

Moreover, the polarization of the CMBR—an observed and well-measured feature—arises naturally in the SCM due to Thomson scattering in an ionized medium prior to recombination. The consistency of this prediction with observations has contributed significantly to the model’s credibility.

However, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM) offers a fundamentally different interpretation rooted in evolving microphysical parameters. According to the SVCM, many fundamental physical constants, including the rest mass and electric charge of the electron, vary over cosmological time. These time-varying parameters influence scattering processes and the opacity of the universe in its early phases.

In this framework, the Thomson and Klein-Nishina scattering coefficients attain extremely large values in the very early universe (as shown in Equations 5.33, 5.35, and the limit in 5.23). These coefficients are heavily dependent on the electron’s rest mass, which is predicted by the theory to approach zero as we move back in time toward the initial Vacuum State. Consequently, the free electron density and the strength of interaction between photons and free electrons would have been sufficient to render the universe highly opaque in its initial phase. This leads naturally to blackbody radiation conditions—essentially predicting the CMBR as an emergent property of the high-opacity, ionized state of the early universe.

Furthermore, the initial ionization of the universe—as deduced from Equations 5.36 and 5.38—also implies that the CMBR should exhibit polarization, aligning with empirical observations. The SVCM, therefore, does not require a singular explosive event (i.e., a Big Bang) to account for the CMBR. Instead, it derives it as a natural consequence of the dynamics of self-varying physical parameters within an evolving universe.

The SVCM formalism allows astrophysical parameters to be expressed as functions of redshift, a quantity that is empirically measurable with high precision. This enables the accurate reconstruction of the universe’s thermodynamic and electromagnetic conditions across its history. Given the precision of the SVCM’s predictive framework, its explanation of the CMBR is presented not as a speculative alternative but as a theoretically grounded and calculable consequence of the model.

Summary: Justification of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation in Competing Models

Standard Cosmological Model:

The CMBR is interpreted as a relic radiation from the Big Bang, produced during the recombination period and observed today after redshift cooling to ~2.73 K. Its polarization is attributed to Thomson scattering in the early ionized universe.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

The CMBR arises from the extremely high values of the Thomson and Klein-Nishina scattering coefficients in the very early universe, caused by the near-zero electron rest mass in the initial Vacuum State. The resulting high opacity and ionization naturally yield blackbody radiation and its observed polarization, without invoking a primordial explosion.

5.10.4. Increased Luminosity Distances of Type Ia Supernovae

On cosmological scales, the distances of astronomical objects can be estimated via redshift, provided that the exact value of the Hubble constant is known. However, the determination of distances to distant astronomical sources is a considerably more complex issue. The first challenge arises from the very definition of “distance,” as this concept differs in flat versus curved geometries. Observational data indicate that the large-scale structure of the universe is flat; thus, Euclidean geometry can be employed to define the distance of a distant source based on its redshift.

This distance — corresponding to the location of the object at the moment it emitted the electromagnetic radiation currently observed on Earth — is embedded within Hubble’s law. To verify the validity of Hubble’s law, however, one must also be able to determine cosmic distances through independent methods.

Astronomical distances can be measured through a hierarchy of techniques, depending on the scale. At small scales, geometric (trigonometric) methods such as triangulation are employed. For greater distances, astronomers utilize so-called standard candles — celestial objects whose intrinsic luminosity can be inferred from observable properties, such as the periodicity of their brightness. Cepheid variables and other pulsating stars serve as classic examples. In addition, Type Ia supernovae — whose light curves follow a characteristic temporal profile — are used as powerful standard candles. These supernovae exhibit rapid increases in luminosity and emit vast amounts of energy, rendering them visible even in extremely distant galaxies. As such, they are essential tools for constructing the cosmic distance ladder.

One of the most widely used distance measures in cosmology is the luminosity distance, denoted D. It is derived from the observed flux received on Earth, given the known intrinsic luminosity of the source. Since energy spreads spherically, the received flux is inversely proportional to the square of the distance. Importantly, D differs from the geometric (or comoving) distance r, because the total energy emitted may not correspond exactly to theoretical assumptions. If the intrinsic luminosity is lower than expected, D will be overestimated; conversely, if it is higher, D will be underestimated.

The light curves of Type Ia supern”vae ’llow precise determination of their absolute magnitudes, enabling distance estimations across cosmological scales. In the late 1990s, two independent teams — led by Adam Riess [

68] and Saul Perlmutter [

66] — used Type Ia supernovae to perform long-distance measurements aimed at confirming the deceleration of cosmic expansion. According to the Standard Cosmological Model (SCM), the gravitational influence of matter-energy content should cause a gradual slowing of the expansion rate. Surprisingly, the observational results contradicted these expectations. The measured luminosity distances of Type Ia supernovae were significantly larger than those predicted by the SCM. Two hypotheses emerged to account for this discrepancy:

The characteristic light curve of Type Ia supernovae may differ in distant galaxies compared to those in the Milky Way.

The universe is undergoing accelerated expansion.

The first hypothesis is inconsistent with the principles of 20th-century physics and is therefore discarded. The second hypothesis, however, implies the existence of an unknown form of energy that permeates space and drives repulsive gravitational effects. This led to the introduction of dark energy, a term coined to represent the agent responsible for the observed acceleration.

Dark energy is incorporated into Einstein’s field equations via the cosmological constant Lambda Λ, initially introduced by Einstein to model a static universe. The currently prevailing cosmological model, known as the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM) model, adopts this framework. While other cosmological models have been proposed — some similar, others radically different — all share the dark energy hypothesis as a central feature. Despite intense speculation, the origin, nature, and distribution of dark energy remain largely unknown.

According to the Self-Variation Theory, seven astrophysical parameters are redshift-dependent (see Equations (5.27), (5.28), (5.33), (5.36), (5.38), (5.40), and (5.42)). Among these are the rest masses of fundamental particles, such as the electron and hydrogen atom. These parameters influence every stage in the evolution of a Type Ia supernova — from the progenitor binary system to the supernova explosion itself. Consequently, physical characteristics such as the Chandrasekhar limit, light curve profiles, and energy output may differ across cosmic time.

As redshift increases, these differences become more pronounced. Therefore, Type Ia supernovae cannot be universally treated as standard candles across all redshifts. Accurate determination of their luminosity distances on cosmological scales requires accounting for the redshift-dependence of fundamental parameters. The Self-Variation Theory provides the necessary framework and equations to perform such corrections.

Summary: Interpretation of the Increased Luminosity Distances of Type Ia Supernovae

Standard Cosmological Model:

The increased luminosity distances are explained by accelerated cosmic expansion, necessitating the introduction of Dark Energy as a repulsive force to align theoretical predictions with observations.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

The observed increase in luminosity distances is a direct consequence of the redshift-dependent variation of fundamental physical constants, which alter the behavior and brightness of Type Ia supernovae over time. As a result, Type Ia supernovae cannot serve as universal standard candles without accounting for this variation. The SVCM provides the equations required to model these effects accurately.

5.10.5. Flatness of the Universe

Observational data from the cosmic microwave background and large-scale structure surveys strongly support the conclusion that, on cosmological scales, spacetime is flat. According to General Relativity, the curvature of spacetime is determined by its energy content [

1]. A spatially flat universe corresponds to a critical energy density, characterized by a density parameter Ω=1. If Ω>1, the universe is closed and positively curved; if Ω<1, the universe is open and negatively curved.

In the context of the Standard Cosmological Model (SCM), this flatness is not an intrinsic prediction but a fine-tuned requirement. Mathematical analysis reveals that for the universe to remain flat over cosmic time, the initial value of Ω must have been extraordinarily close to 1 in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang—so close that even a deviation of one part in would lead to significant curvature today. This situation, often referred to as the flatness problem, suggests that the observed flatness of the universe is highly improbable under standard assumptions.

Furthermore, by the late 1970s, improved estimates of matter density revealed a significant discrepancy: inserting the observed energy density into the Einstein field equations would predict a universe that should have rapidly recollapsed shortly after the Big Bang. To reconcile these contradictions, physicists introduced the inflation hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, during the first

to

seconds of the universe’s existence, space underwent an exponential expansion. This inflationary phase would stretch out any initial curvature and drive Ω towards 1, thereby explaining the current flatness of the universe, preventing gravitational collapse, and addressing other cosmological puzzles—namely the horizon problem and the monopole problem [

106].

However, the inflation hypothesis, while widely adopted, is not without significant theoretical issues. It introduces a degree of arbitrariness, especially regarding the initiation and cessation of inflation. Two central questions remain unresolved:

Why did inflation last exactly long enough to offset gravitational collapse—but no longer?

How did inflation begin and end with such precision?

Attempts to answer these questions often involve speculative quantum field theories or exotic scalar fields (e.g., the inflaton), yet none have been conclusively validated by observational evidence. Additionally, recent high-precision cosmological data increasingly challenge some predictions of simple inflationary models [

107,

108]. After nearly five decades of development, inflation remains an ad hoc solution to fundamental structural issues in the SCM. Nonetheless, within the framework of twentieth-century physics, inflation was considered unavoidable to ensure internal consistency.

In contrast, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM) offers a fundamentally different and arguably more natural explanation for the universe’s flatness.

Starting from the Vacuum State and invoking energy-momentum conservation, the SVCM predicts that the total energy content of the universe tends to zero—globally—at all stages of cosmic evolution. This includes not only rest energy and kinetic energy, but also negative potential energy from gravitational and other fundamental interactions. When these components are fully accounted for, particularly across all distance scales, the net energy within any cosmological domain approaches zero.

A central feature of the Self-Variation Theory is that the rest masses of particles are not constant, but vary over time as functions of cosmological parameters such as redshift. This self-variation of rest mass contributes a dynamically evolving negative energy background, which balances the positive energy of matter and radiation.

Consequently, the universe—across all phases of its evolution—is characterized by a zero total energy condition. This balance necessitates that the universe be spatially flat. Therefore, in the context of SVCM, the flatness of the universe is not a coincidence requiring fine-tuning or inflation, but a natural and inevitable outcome of the theory’s foundational principles.

Summary: Interpretation of the Universe’s Flatness in Competing Models

Standard Cosmological Model:

The flatness of the universe is not naturally predicted and is instead explained by the inflation hypothesis, which posits a brief period of exponential expansion to force the density parameter Ω towards 1. This hypothesis, however, introduces unresolved theoretical issues and remains speculative.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

The flatness of the universe is a direct consequence of the zero-total-energy condition resulting from the self-variation of rest mass and associated negative potential energy. Thus, flatness is intrinsic to the model and requires no additional hypotheses.

5.10.6. Nucleosynthesis of the Chemical Elements

Immediately following the Big Bang, the universe is theorized to have existed in an extremely hot and dense state, with temperatures exceeding 10 billion Kelvin. In this early phase, matter and radiation were in thermodynamic equilibrium, forming a primordial plasma composed of fundamental particles such as quarks, leptons, and gauge bosons. As the universe expanded, it also cooled, transitioning through critical thermodynamic thresholds that enabled the formation of increasingly complex particles.

In the framework of the Standard Cosmological Model, the cooling rate of the universe is directly linked to its expansion rate, governed by the equations of General Relativity and thermodynamics. At approximately 1 second after the Big Bang, the temperature had decreased to around 10¹⁰ K, allowing the formation of stable protons, neutrons, electrons, and neutrinos. As cooling continued to 10⁹–10⁸ K, conditions became favorable for Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN)—the fusion of light nuclei from the primordial soup of subatomic particles.

This nucleosynthesis phase, which lasted for only a few minutes, produced primarily helium-4, along with smaller amounts of deuterium, helium-3, and lithium-7. Detailed mathematical models based on twentieth-century particle physics and nuclear reaction rates have successfully predicted the relative abundances of these light elements. These predictions are in remarkable agreement with observational data, such as spectroscopic measurements of ancient gas clouds and cosmic microwave background anisotropies [

109,

110]. Thus, within the Standard Model, nucleosynthesis is a well-established and successful theoretical outcome, contingent on an assumed relation between temperature evolution and cosmic expansion.

In contrast, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model approaches the formation of particles and nuclei from a different foundational perspective. Beginning from a Vacuum State, the model posits that complex particles emerge due to the progressive intensification of fundamental interactions—a consequence of the self-variation of rest mass and other fundamental quantities over space and time.

As explored in Chapter 3, the SVCM introduces additional structural insight into the electromagnetic interaction. Notably, the theory allows for a spatial distribution of electric charge and current in the surrounding spacetime of a point particle, derived from the density expressions given in Equation (3.47). This leads to the interpretation that elementary particles may not be purely localized but have extended electromagnetic properties as a result of self-variation. In Chapter 4, the theory introduces eight distinct interactions that derive from rest mass. These interactions are characterized by the critical feature of being neither purely attractive nor purely repulsive, which enables the stable formation of bound systems—possibly including atomic nuclei.

In the SVCM, the emergence of fundamental and composite particles, including nuclei, is not merely a consequence of thermodynamic conditions, but results from a deeper dynamical process driven by rest mass variation. While the full mathematical development of nucleosynthesis in this context requires an investigation into the unified treatment of interactions described in Chapters 3, 4, and 6, the model implies that the synthesis of elements may follow alternative mechanisms, perhaps not strictly reliant on a specific temperature-expansion relation.

At present, this investigation is ongoing and not yet fully included in the published framework of the theory. Nevertheless, the SVCM provides the mathematical groundwork for a potentially novel explanation of elemental synthesis, rooted in the self-variation of physical constants and the emergence of interactions as a function of redshift and spacetime evolution.

Summary: Interpretation of Nucleosynthesis in Competing Models

Standard Cosmological Model:

Predicts the synthesis of light elements based on the established principles of nuclear physics and thermodynamics. These predictions are consistent with observed abundances, provided a specific relationship between the universe’s expansion rate and its cooling rate is assumed.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

Suggests that the formation of fundamental and composite particles, including atomic nuclei, arises from self-variation-driven interactions—particularly those involving the rest mass of particles. While a full predictive framework for nucleosynthesis is not yet published, the theory lays the mathematical and conceptual foundations for an alternative explanation, pending further investigation.

5.10.7. Ionization of Atoms in the Early Universe

In the aftermath of the Big Bang, the universe was in a state of extremely high temperature and density. Under such conditions, matter existed in the form of a fully ionized plasma—a mixture of free protons, electrons, and other elementary particles in thermal equilibrium with radiation. This ionized phase, characterized by frequent photon scattering via Thomson scattering, rendered the universe opaque to electromagnetic radiation. This period lasted approximately 380,000 years, during which photons could not travel freely through space.

As the universe expanded, it cooled, eventually reaching a temperature at which electrons and protons could recombine to form neutral hydrogen atoms. This epoch is known as recombination. The formation of neutral hydrogen dramatically reduced the universe’s opacity, allowing photons to decouple from matter and propagate freely—giving rise to the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation. This marked the transition to the so-called “dark ages” of the universe, a period with no visible light sources until the formation of the first stars and galaxies.

Subsequently, ultraviolet radiation emitted by the first generations of stars began to reionize the intergalactic hydrogen. This reionization epoch reestablished the ionized state of hydrogen throughout the intergalactic medium, where it remains fully ionized today. Observational data, including measurements of CMB polarization and the Lyman-alpha forest in quasar spectra, align well with this timeline of recombination and reionization, validating the predictions of the Standard Cosmological Model.

In contrast, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM) approaches the ionization history of the universe from a fundamentally different theoretical foundation. In this framework, the redshift observed in astronomical spectra is interpreted not as a result of cosmic expansion, but as a direct consequence of the variation in the ionization energy of atoms over cosmological time.

Specifically, SVCM posits that the ionization energy of atoms is a function of redshift—i.e., it decreases as one looks further back in time (to higher redshift values). According to Equations (5.36) and (5.38), in the early universe, the ionization energy tends asymptotically toward zero. Consequently, atomic systems—such as hydrogen—could not yet form, and the universe remained ionized due to the inability of protons and electrons to bind into stable atoms.

The formation of hydrogen in this context depends critically on the Bohr radius, which itself is redshift-dependent. As shown in Equations (5.42), (5.43) and the limit (5.23), the hydrogen atom becomes stable only when the Bohr radius decreases below a certain threshold, allowing electrostatic attraction to dominate over quantum uncertainty. This dependency introduces a quantum-dynamical condition for recombination, rooted in the self-variation of rest mass and electric charge, rather than purely thermal considerations.

Moreover, in the SVCM, the extremely large values of the Thomson and Klein-Nishina scattering coefficients in the early universe (see Equation (5.35) and limit (5.23)) render it highly opaque, consistent with the observed polarization of the CMB—produced via electron scattering in an ionized medium.

After the formation of stars and galaxies, ionization of intergalactic hydrogen once again becomes dominated by ultraviolet radiation from stellar sources, similar to the mechanism described by the Standard Model. However, the initial ionization state and the mechanism of recombination are governed by entirely different principles in the SVCM.

Summary: Interpretation of Ionization in the Early Universe

Standard Cosmological Model:

Ionization of the early universe is a consequence of high thermal energy immediately following the Big Bang. Recombination occurs as the universe expands and cools, allowing neutral atoms to form. Subsequent reionization is driven by stellar ultraviolet radiation.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

Ionization is due to the self-variation of atomic properties with redshift. In the early universe, the ionization energy tends to zero, preventing atom formation. The emergence of neutral hydrogen is governed by the Bohr radius reaching a critical value. Later reionization again occurs via stellar UV radiation.

5.10.8. Distribution of Matter on the Cosmological Scale

Modern astronomical observations—enabled by increasingly sophisticated instrumentation and observational techniques—have extended our reach into the deep past of the universe, probing epochs very close to what the Standard Cosmological Model (SCM) identifies as the Big Bang. These observations are now testing the limits of the SCM’s predictive framework, particularly in terms of the timeline of structure formation.

Three notable observational findings have raised critical questions about the SCM’s assumptions:

An oversized black hole discovered at 690 million years after the Big Bang ([

45]) possesses a mass so large that standard formation and accretion models within the SCM cannot account for its growth in the available time.

A pair of mature galaxies have been observed at 800 million years post-Big Bang ([

46]), exhibiting levels of structural organization, stellar mass, and chemical enrichment that require more time than the model permits.

The detection of a 21 cm hydrogen absorption line ([

62]) just 180 million years after the Big Bang implies that stars were already forming and producing a UV background at a remarkably early epoch—again earlier than the SCM would anticipate based on known rates of star formation.

Collectively, these observations present a substantial challenge to the temporal framework of the Standard Cosmological Model. Within its context, the rate of expansion and cooling from the Big Bang imposes a strict timeline on the emergence of gravitationally bound structures. Yet, the observed existence of complex systems—such as black holes, galaxies, and star-forming regions—so soon after the Big Bang indicates that either the structures formed faster than allowed by the model, or that the timeline itself may be flawed.

To reconcile these discrepancies, the SCM must invoke non-standard processes—such as exotic forms of dark matter, enhanced primordial density fluctuations, or hyper-efficient accretion mechanisms—all of which remain speculative and lack direct empirical support.

In contrast, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM) offers a framework that naturally accommodates these observations. The SVCM begins from a Vacuum State, and the evolution of the universe proceeds through the self-variation of fundamental physical parameters over time and redshift. Importantly, this theory does not require a singular origin such as the Big Bang and does not impose a compressed early timeline for structure formation.

In the SVCM framework:

The rest masses of elementary particles, the Bohr radius, the ionization energy, and various interaction coefficients evolve with redshift, leading to different dynamical conditions for gravitational collapse, radiation, and matter organization at different epochs.

The universe experiences a prolonged phase of structure formation, allowing ample time for complex systems—such as supermassive black holes and galaxies—to form gradually, consistent with observational evidence.

The absence of a singularity or ultra-compressed initial state means there is no constraint equivalent to the “time since the Big Bang”, thus removing the paradox posed by early massive structures.

Thus, rather than struggling to compress cosmic evolution into an insufficient temporal window, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model reframes the cosmological timeline, making room for the early appearance of massive and organized matter structures as a natural consequence of its foundational equations.

Summary: Interpretation of Early Structure Formation

Standard Cosmological Model:

Observations of large-scale structures forming within the first billion years are inconsistent with the model’s timeline. The formation of black holes, galaxies, and stellar populations occurs too early to be explained without speculative mechanisms.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

These observations are fully consistent with a longer, non-singular timeline of evolution. The gradual self-organization of matter from the Vacuum State allows for the early emergence of structure without theoretical strain.

5.10.9. Variation of the Fine Structure Constant

The fine structure constant (α) is one of the most fundamental constants in physics. Dimensionless and universal, it governs the strength of the electromagnetic interaction and appears in a wide range of quantum electrodynamics (QED) calculations, beginning with its original introduction in the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom ([

75]). Its accepted value under laboratory conditions is approximately 1/137.

In the Standard Cosmological Model (SCM) and more broadly in 20th-century physical theories, α is treated as immutable, based on the assumption that the constants on which it depends—such as the elementary charge, Planck’s constant, and the speed of light—are invariant in both space and time. As a consequence, electromagnetic processes are expected to behave identically at all locations in the universe and at all epochs in its history.

However, recent observational studies—such as spectral line comparisons in quasar absorption systems—have suggested possible slight variations in α over cosmological distances and timescales. These hints, though not conclusive, have achieved a statistical confidence level of about 3.9σ, which falls short of the standard 5σ threshold for experimental discovery but nonetheless warrants serious theoretical attention [

52,

73].

In an attempt to account for this within the Standard Model framework, some theorists have proposed that a time-varying speed of light I could explain the variation of α. However, this approach raises deep theoretical problems:

A varying c directly contradicts Special Relativity, which has been experimentally confirmed to extraordinary precision in numerous contexts, from particle accelerators to atomic clocks on satellites. Rejecting Special Relativity implies a need to revise Maxwell’s equations, which form the bedrock of classical electromagnetism. The implications would cascade across all of physics—from quantum mechanics to general relativity, and even to basic electrodynamic interactions observed in laboratories.

Despite the speculative appeal of solving the horizon problem or other cosmological puzzles via a varying c, there is no comprehensive theoretical framework that consistently incorporates a time-varying speed of light while remaining compatible with the established body of physical laws.

In contrast, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM) provides a natural and internally consistent mechanism for the variation of the fine structure constant. Within the SVCM:

The electromagnetic field arises as a consequence of the self-variation of the electric charge, and hence the fine structure constant (α), which is proportional to the square of the electron charge, varies as a function of redshift and position (refer to Equation (5.14)).

The variation of α is therefore not an anomaly, but rather a direct and expected result of the theory, deeply tied to its foundational equations (e.g., Equation (5.11)).

This variation does not require altering the speed of light, nor does it contradict Special Relativity or Maxwellian electrodynamics, since the theory is constructed with self-variation as a core principle from the outset.

Thus, the SVCM incorporates the possible spatial and temporal variation of α as a natural phenomenon, emerging from its broader treatment of how fundamental constants evolve in spacetime. This makes it more compatible with the tentative observational indications, and avoids the theoretical disruption associated with modifying c.

Summary: Interpretation of the Fine Structure Constant Variation

Standard Cosmological Model:

A variation of α is not predicted. Attempts to incorporate such a variation—by introducing a time-dependent speed of light—challenge core physical theories (Special Relativity, Maxwell’s laws), and lack a comprehensive theoretical foundation.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

The variation of α is a direct consequence of the self-variation of the electron’s charge and related fundamental constants. Observational evidence of α’s variation, even if not yet conclusive, is entirely compatible with the theoretical expectations of the SVCM.

5.10.10. The Horizon Problem

One of the most significant conceptual challenges for the Standard Cosmological Model (SCM) is the so-called horizon problem. This issue arises from observations of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation (CMBR)—a relic of the early universe that displays a remarkable degree of isotropy, with temperature fluctuations no larger than 1 part in 100,000 across the sky.

According to the Theory of General Relativity, in a universe originating from a Big Bang singularity and expanding over time, the observable universe is divided into causally disconnected regions—areas that, due to the finite speed of light and the finite age of the universe, could not have exchanged information or energy. These non-overlapping causal spheres imply that there is no mechanism within classical General Relativity to explain how such regions came to be at the same temperature or physical state. Yet, observations reveal that the CMBR is strikingly uniform, even across vast angular separations.

This contradiction was first formally articulated by Wolfgang Rindler in 1956 ([

109]) and is now a cornerstone concern in modern cosmology. In the SCM, the inflationary hypothesis is invoked as a resolution: a brief period of exponential expansion in the very early universe is posited to have stretched a once-causally connected patch of space to scales far larger than the current horizon, thereby ensuring homogeneity. However, as discussed previously, inflation introduces significant theoretical uncertainties:

It relies on a hypothetical scalar field (the inflaton) for which no empirical evidence exists.

It involves fine-tuning problems, including the exact timing of inflation and its termination.

It leads to difficulties in reconciling with recent observations and lacks predictive specificity in some formulations.

The Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM) offers a qualitatively different resolution to the horizon problem, grounded in its fundamental assumptions about the nature of matter and spacetime at high redshift.

Within the framework of SVCM:

The uncertainty in a particle’s position in spacetime increases with redshift. Specifically, as the universe approaches the initial Vacuum State, the uncertainty becomes infinitely large (refer to Equations (5.40)–(5.43) and limit (5.23)).

This implies that, in the distant past, every particle had a non-zero probability of being located anywhere in spacetime, effectively erasing the concept of spatial separation or causality as understood in classical terms.

In such a framework, the entire universe is inherently connected at early times—not through superluminal inflationary expansion, but through the quantum-statistical properties of matter and space.

Thus, in the SVCM, the homogeneity of the CMBR is not a problem to be solved, but rather a natural prediction of the theory’s foundational equations. Unlike the SCM, which introduces an ad hoc inflationary phase, the SVCM integrates the solution into its core structure via self-variation of physical parameters, including position uncertainty and redshift-dependent particle properties.

Summary: Interpretation of the Horizon Problem

Standard Cosmological Model:

The horizon problem arises due to non-overlapping causal regions implied by the Big Bang and finite light travel time. It is addressed through the inflation hypothesis, which postulates a rapid early expansion phase to explain the observed isotropy. However, inflation remains speculative, with significant theoretical and empirical challenges.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

The model predicts that the uncertainty in the position of particles tends to infinity near the initial Vacuum State. This leads to a natural and intrinsic spatial connectivity at early times, thereby resolving the horizon problem without invoking inflation.

5.10.11. The Larger Than Expected Velocities of Astronomical Objects at The Outskirts of Large Structures of Universe’s Matter

A major and long-standing observational inconsistency in astrophysics arises from the rotational dynamics of galaxies and the motion of galaxies within galaxy clusters. This discrepancy was first identified by Fritz Zwicky in 1937 during his study of the Coma Cluster ([

44]). Zwicky observed that the measured velocities of galaxies within the cluster were significantly higher than could be explained by the visible mass (i.e., the mass inferred from luminous matter such as stars and gas). He concluded that an invisible form of mass, which he termed “Dunkle Materie” (Dark Matter), must be present to generate the additional gravitational force required to keep the galaxies gravitationally bound.

Subsequent observations—particularly the flat rotation curves of spiral galaxies, in which the orbital velocity of stars remains nearly constant far beyond the visible edge of the galaxy—have further strengthened the case for dark matter. According to Newtonian and relativistic dynamics, one would expect the velocity to decrease with distance from the galactic center in the absence of additional unseen mass. However, observations show that these velocities remain unexpectedly high and flat.

In the context of the Standard Cosmological Model, this discrepancy is resolved by postulating the existence of dark matter halos enveloping galaxies and clusters. These halos are composed of non-luminous, non-baryonic matter that interacts gravitationally but does not emit, absorb, or reflect light, making it undetectable by traditional observational methods. The dark matter hypothesis is a cornerstone of the ΛCDM model, which asserts that roughly 27% of the universe’s energy-matter content is dark matter. Yet, despite decades of observational support and indirect evidence (e.g., gravitational lensing, cosmic structure formation, cosmic microwave background anisotropies), dark matter has never been directly detected.

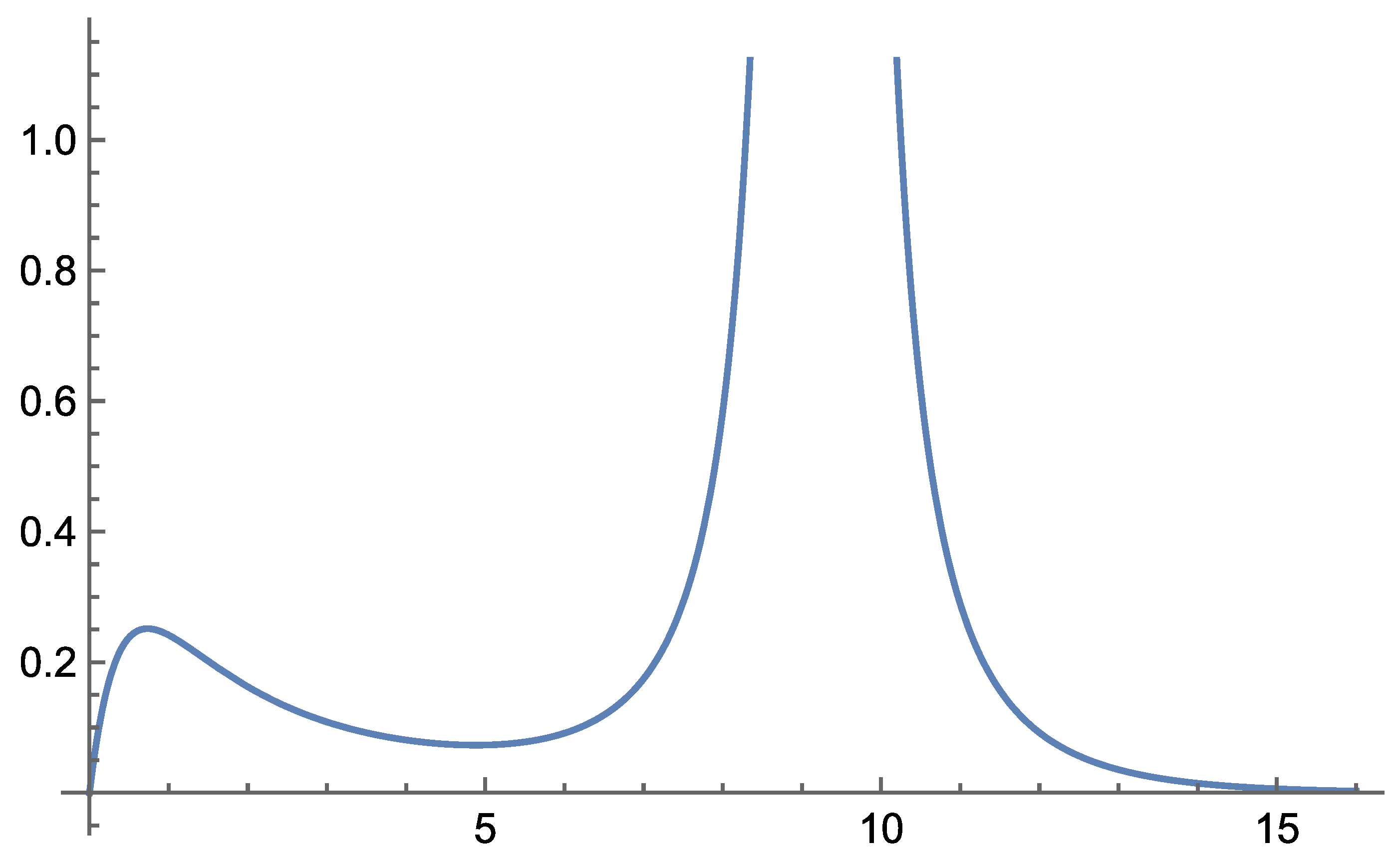

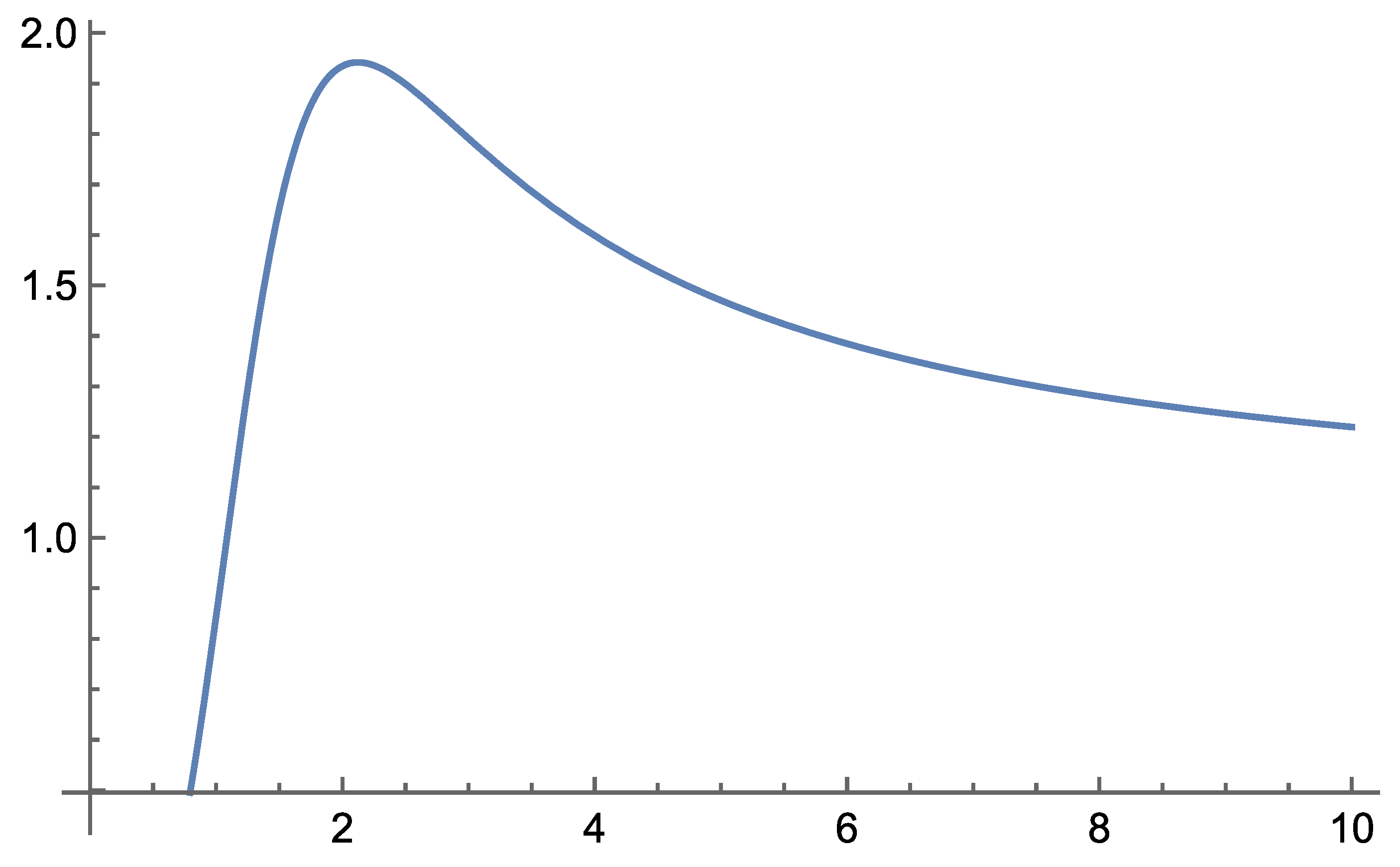

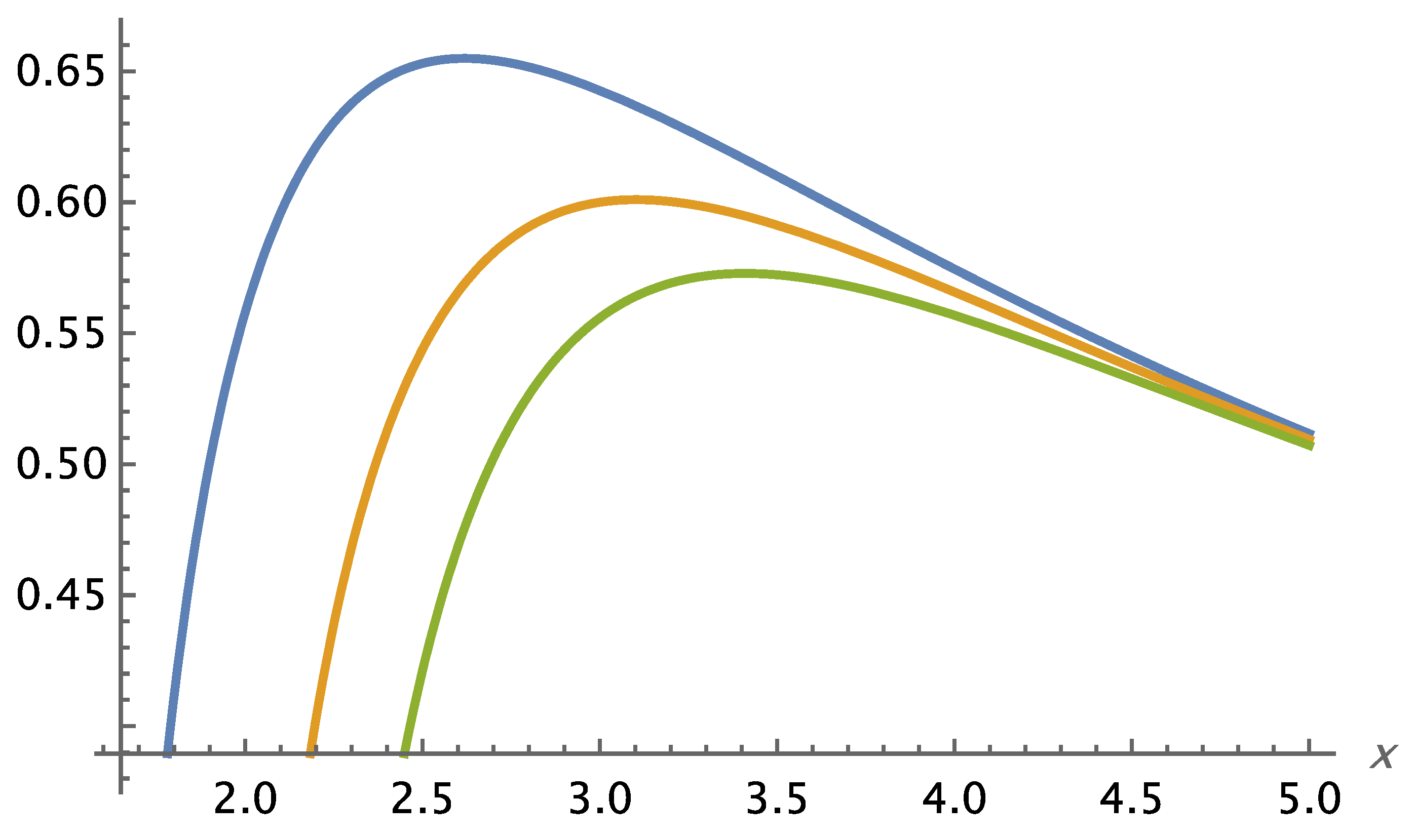

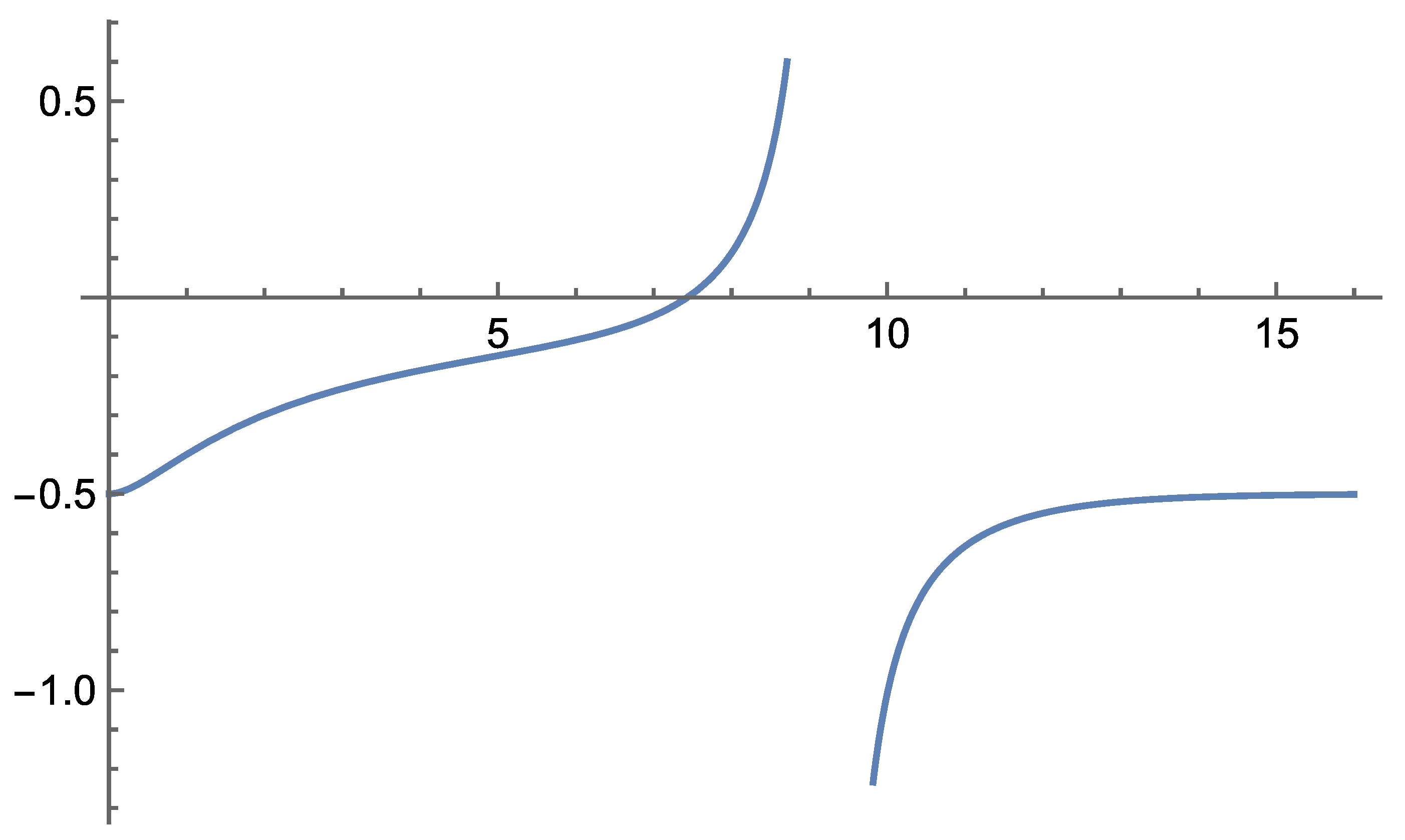

The Self-Variation Cosmological Model offers an alternative explanation to the dark matter hypothesis by directly modifying the gravitational field equations derived from its theoretical framework. In particular, Chapter 4 of the theory provides a derivation of gravitational dynamics, accounting for the observed high orbital velocities of stars and galaxies without invoking unseen matter.

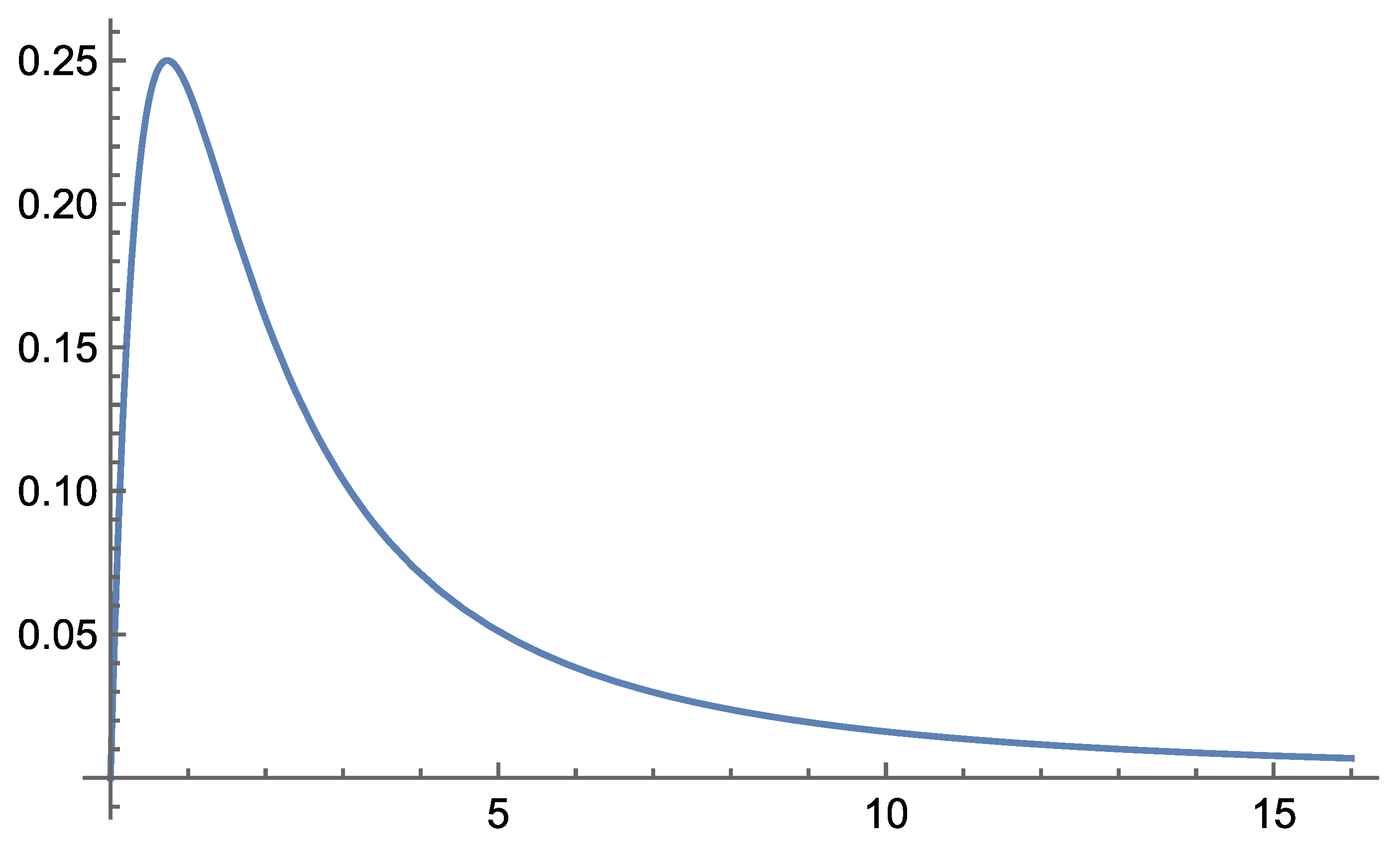

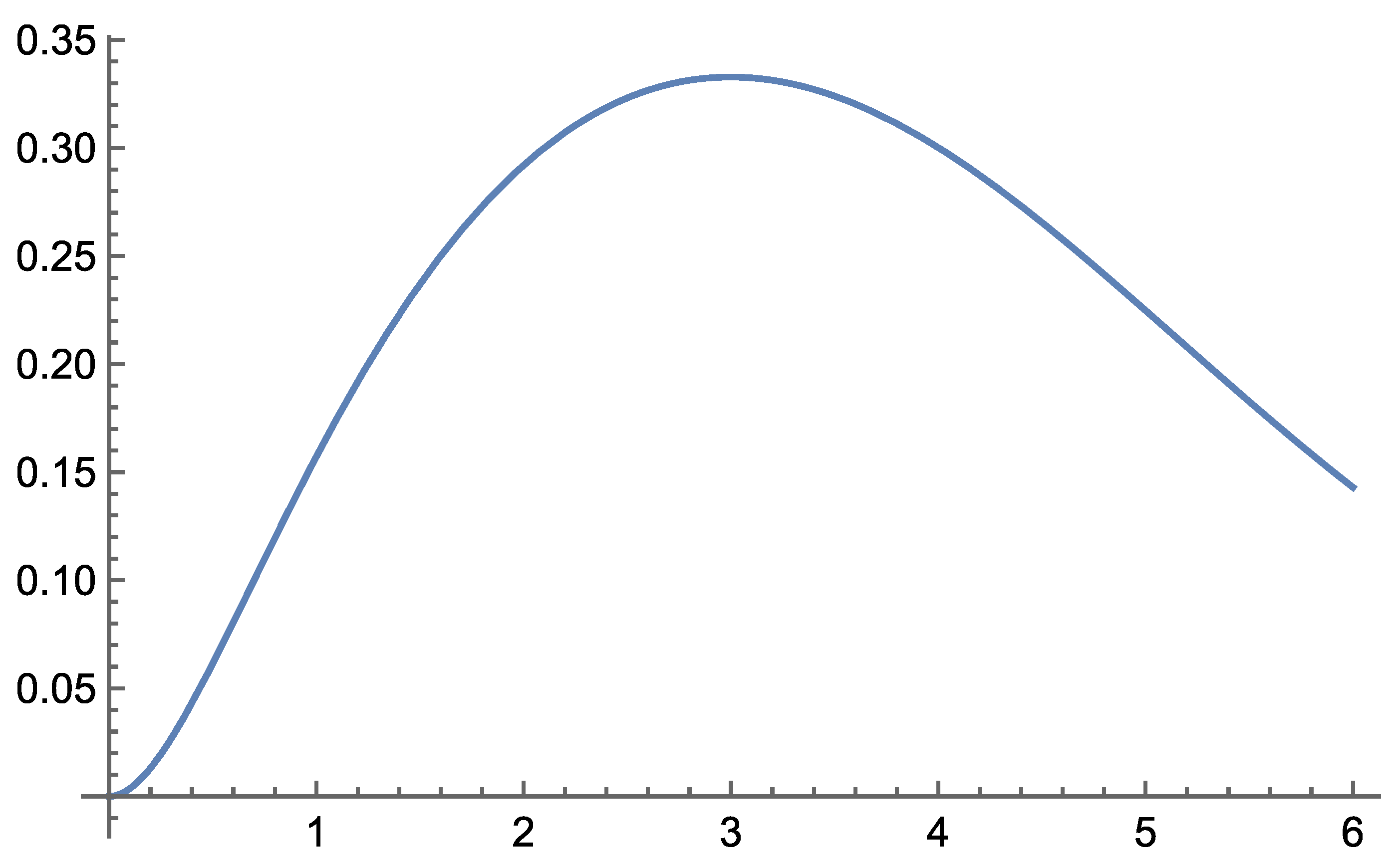

Specifically, the SVCM introduces self-variation in physical parameters (such as mass and charge) as functions of spacetime coordinates or cosmological scale factors (e.g., redshift). These variations influence gravitational behavior on galactic and larger scales. The resulting predictions, illustrated in Figures 4.23, 4.24, and 4.25, are empirically consistent with the observed rotation curves of a wide range of galaxies. This approach not only preserves the visibility-based mass estimates but also provides a natural theoretical foundation for the observed deviations in rotational dynamics—one that is intrinsic to the theory, rather than added post hoc as in the case of dark matter.

The SVCM thus anticipates that a more detailed simulation of its gravitational field equations, tailored to specific galactic mass distributions, would bring it into even closer agreement with observational data across all scales.

Summary: Interpretation of Galaxy Rotation and the Missing Mass Problem

Standard Cosmological Model:

The observed high orbital velocities of stars in galaxies and galaxies in clusters are incompatible with the mass inferred from visible matter. The model introduces the hypothesis of dark matter—a form of non-baryonic, invisible matter—to account for the additional gravitational effects. Despite its utility and consistency with large-scale observations, dark matter has not been directly observed, and its fundamental nature remains unknown.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

The observed discrepancies are predicted directly from gravitational equations derived from the self-variation of physical constants. This leads to natural explanations of galaxy rotation curves and cluster dynamics without invoking additional, unseen forms of matter. Empirical plots derived from the theory match observed data and suggest that full simulations would further validate the model.

5.10.12. Absence of Magnetic Monopoles in the Universe

One of the persistent puzzles in cosmology and high-energy physics is the non-detection of magnetic monopoles—hypothetical particles that carry isolated magnetic charge. These entities are predicted by Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) and are considered natural consequences of certain symmetry-breaking processes thought to occur during the early moments of the universe, particularly near the GUT scale shortly after the Big Bang.

Standard Cosmological Model (SCM)

According to the SCM and the theoretical framework of GUTs, the early universe experienced conditions that would have favored the production of magnetic monopoles in abundance. If these conditions held, an extremely high density of monopoles would have emerged—possibly with one monopole per horizon volume at the time of their formation. Given the current size and age of the universe, such a density would imply that monopoles should be readily observable today, scattered across space.

However, no magnetic monopoles have ever been observed, despite decades of targeted searches using highly sensitive instruments. Initial experiments reported ambiguous or inconclusive results, but no statistically significant detection has been confirmed ([

106]).

This stark discrepancy between theoretical prediction and observational reality constitutes a serious problem for the SCM and related GUTs. To address it, the inflationary hypothesis was introduced. Inflation postulates a brief period of exponential expansion shortly after the Big Bang, which would have diluted the density of magnetic monopoles by many orders of magnitude. As a result, the present-day density of monopoles could be so low that their non-detection is plausible. However, this solution is not derived directly from the core principles of the SCM—it is an auxiliary hypothesis invoked to reconcile theory with observation.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM)

In contrast, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model does not require such an auxiliary hypothesis. Within its theoretical framework, the non-existence of magnetic monopoles is a natural consequence of the fundamental equations.

The SVCM maintains the compatibility of Maxwell’s equations with self-variation (refer to

Appendix B). The model preserves the symmetry of Maxwell’s equations without the introduction of magnetic charge, and more importantly, it postulates that no phase or condition in the early universe—as described by the self-variation framework—would favor the creation of monopoles.

In particular, Equation (5.11), which governs the self-variation of physical parameters, leaves the fundamental structure of the electromagnetic interaction unchanged in such a way that monopoles are neither required nor permitted. The smooth mathematical approach to the vacuum state in the SVCM allows the theory to remain consistent at all cosmological epochs, without invoking hypothetical particles or exotic processes.

Thus, the absence of magnetic monopoles is not a problem that needs to be solved within the Self-Variation framework—it is an expected and consistent feature of the theory.

Summary: Interpretation of the Absence of Magnetic Monopoles

Standard Cosmological Model:

The absence of magnetic monopoles presents a critical challenge to the Standard Cosmological Model, requiring the adoption of the inflation hypothesis as a retrofitted solution. While inflation addresses multiple issues (flatness, horizon, monopoles), it introduces additional theoretical complexities and open questions.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model:

By contrast, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model offers a framework in which the non-existence of magnetic monopoles is a natural and direct result of the theory’s internal structure. This positions the SVCM as potentially more economical and predictively coherent, at least with respect to this particular cosmological problem.

5.10.13. Olbers Paradox

Olbers’ Paradox—named after the 19th-century astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers—asks a deceptively simple question: Why is the night sky dark? In an infinite, static, and eternal universe uniformly filled with stars, every line of sight should eventually terminate at a star. This would mean the sky ought to be blazing with light, comparable to the surface of the Sun. Yet, this is not what we observe. The paradox, therefore, challenges any cosmological model to reconcile observational darkness with theoretical expectations about the universe’s structure and content.

Standard Cosmological Model (SCM)

In the context of the Standard Cosmological Model, Olbers’ paradox is resolved primarily through the framework of the expanding universe:

Finite Age of the Universe: The universe is not eternal—it has a beginning (the Big Bang), estimated to have occurred about 13.8 billion years ago. Thus, there has only been a finite amount of time for starlight to travel to Earth. Beyond a certain distance, light has not yet reached us.

Redshift and Photon Energy: As the universe expands, the wavelengths of photons emitted by distant stars are stretched—this is the cosmological redshift. The energy of each photon is reduced by a factor of 1/1+z where z is the redshift. This reduces the apparent brightness and total energy flux received from distant sources.

Result: Even though the universe contains a vast number of stars, the finite age, combined with redshift-induced energy loss, means that the cumulative brightness of the sky is limited. Hence, the night sky appears dark.

Thus, in the SCM, Olbers’ paradox is resolved by invoking the dynamic expansion of space, which redshifts and dilutes incoming radiation.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM)

The Self-Variation Cosmological Model offers a conceptually different interpretation, though it arrives at a similar observational conclusion:

Same Redshift-Energy Relationship: Like the SCM, the SVCM agrees that the energy of photons arriving from distant stars is reduced by the same redshift factor, 1/1+z.

Different Cause of Redshift: However, in the SVCM, redshift is not due to the expansion of space, but instead arises from the self-variation of fundamental physical constants—in particular, the rest mass of the electron. According to Equation (5.36), this variation alters atomic structure and photon energy in such a way that the observed redshift is a consequence of internal particle dynamics, not cosmic expansion.

Application to Olbers’ Paradox: This framework leads to the same quantitative effect: a decrease in the energy and intensity of incoming light from distant sources, rendering the sky dark. Importantly, the SVCM emphasizes that this result holds whether the universe is finite or infinite, as the key factor is not spatial geometry or cosmic history, but the evolving nature of particle properties.

Summary: Interpretation of Olbers’ Paradox

Both cosmological models arrive at a shared observational conclusion: the night sky is dark because the energy of incoming light is diminished over cosmic distances. However, they differ radically in the underlying physics:

The Standard Model grounds its explanation in spacetime dynamics and the finite age of the cosmos.

The Self-Variation Model attributes the phenomenon to a time-dependent change in particle properties, particularly those affecting atomic transitions and photon emission.

The ability of both models to explain Olbers’ Paradox through the same mathematical factor, yet from entirely different premises, highlights the deep conceptual divergence between them and invites further empirical testing to adjudicate between these frameworks.

5.10.14. The Two Measured Values of Hubble’s Constant

One of the most significant and persistent challenges in modern cosmology is the Hubble tension: the disagreement between local measurements of the Hubble constant (based on nearby supernovae and Cepheid variables) and early-universe measurements (based on Cosmic Microwave Background, CMB, data under the assumptions of the Standard Cosmological Model).

Standard Cosmological Model (SCM)

In the SCM framework, redshift is interpreted as the result of cosmic expansion, with representing the current rate of that expansion.

Two Precise but Discordant Measurements:

Local measurements (e.g. SH0ES collaboration):

≈73±1 km/s/Mpc (4.4σ tension)

CMB-based measurements (e.g. Planck mission):

≈67.4±0.5 km/s/Mpc (8σ tension)

Incompatibility:

If the cosmic redshift is exclusively due to space expansion, and the SCM is correct, then both methods should converge to the same , once measurement uncertainties are accounted for. The increasing precision of both methods exacerbates, rather than resolves, the discrepancy.

Implications:

Questions arise regarding new physics beyond the ΛCDM model (dark energy, dark matter).

Numerous hypotheses have been proposed: early dark energy, varying neutrino masses, modified gravity—but none universally accepted. The divergence in age estimates of the universe depending on which

value is used is also problematic:

=67.4: ~13.8 billion years

=73: ~12.8 billion years

Thus, the Hubble tension presents a serious challenge to the internal consistency of the SCM.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM)

The SVCM offers a fundamentally different interpretation of redshift—not as the result of expansion, but as a consequence of self-variation in fundamental constants, particularly the rest mass of particles.

Redshift from Varying Electron Mass:

In this model, Equation (5.36) shows that redshift arises from a distance-dependent (or equivalently, time-dependent) decrease in electron rest mass and possibly other material properties.

Interpreting the Hubble Tension:

Different measurement techniques rely on different physical processes that are affected differently by self-variation (e.g. electron mass vs. baryon mass evolution). Thus, different methods yield different apparent values of , not because of conflicting observations, but because the underlying theoretical assumption (constant mass) is invalid. The apparent discrepancy in is predicted, not problematic, within the SVCM.

Measurement Reconciliation:

The SVCM posits that only by correcting for the self-variation of particle properties can all cosmological measurements yield consistent values. In this view, the Hubble constant is not a universal constant, but an apparent, model-dependent observational parameter.

Summary: Interpretation of the Hubble Tension

The Hubble tension highlights deep cracks in our current understanding of cosmological dynamics. In the SCM, it remains a critical open issue, triggering speculation about unknown physics. The Self-Variation Cosmological Model, on the other hand, treats this tension not as a flaw, but as evidence supporting a paradigm shift—a shift where the constants of nature evolve over cosmological time, and redshift is reinterpreted accordingly.

The question remains whether futur” hig’-precision cosmological surveys and laboratory tests of varying constants will validate the predictions of the SVCM, or instead demand even deeper revisions to our cosmic model.

5.11. Beyond the 13.8 Billion Year Limit

The question of the origin of the universe and the physical validity of extrapolating known laws to the earliest epochs remains central to cosmology. Two fundamentally distinct frameworks—the Standard Cosmological Model (SCM) and the Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM)—propose diverging accounts of the early universe, based on different interpretations of redshift and the evolution of physical parameters.

Standard Cosmological Model (SCM)

The SCM interprets cosmological redshift as a consequence of the metric expansion of space, originating from an initial singularity—the Big Bang—which occurred approximately 13.8 billion years ago, based on the smallest accepted value of the Hubble constant .

Theoretical Breakdown at the Big Bang:

The Big Bang is not a point in space, but a boundary in time at which the density, temperature, and curvature of spacetime become infinite.

General Relativity (GR) fails at this point. The Big Bang is a singularity—a breakdown of the very laws the model depends on.

This singularity is not a “limit” case of GR but represents a region outside the theory’s domain of validity.

Problems Rooted in the Big Bang Singularity:

The horizon problem: How causally disconnected regions of space show the same CMB temperature.

The flatness problem: Why the universe appears spatially flat despite initial condition sensitivity.

The magnetic monopole problem: Predictions of monopoles that are not observed.

The Hubble tension: Conflicting values for , incompatible with a simple Big Bang history.

Ad Hoc Solutions:

These issues led to the introduction of cosmic inflation, a brief period of rapid exponential expansion, intended to smooth out inhomogeneities and resolve the aforementioned problems.

However, inflation introduces its own set of questions (e.g., fine-tuning, initial conditions), and its physical mechanism remains speculative.

Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM)

In contrast, the SVCM avoids invoking a singular origin of the universe. Instead, it posits a smooth emergence of structure from a fundamental Vacuum State, characterized by extreme uncertainty in position and vanishing rest mass of particles. Redshift is attributed not to cosmic expansion, but to the self-variation of physical quantities, such as the electron rest mass and fine structure constant.

No Singularity—No Big Bang:

There is no point in the past where physics breaks down.

All cosmological parameters (mass, charge, Bohr radius, ionization energy) vary continuously with redshift, allowing for smooth extrapolation to earlier times.

The redshift variable z can take arbitrarily large values, meaning the universe may be much older and larger than SCM predicts.

Beginning from the Vacuum State:

At high redshift (z→ ∞), the universe approaches a Vacuum State with zero rest mass and infinite uncertainty of particle positions (from Equations (5.41), (5.43), and limit (5.23)).

This implies that all points in the early universe were causally connected, eliminating the horizon problem without inflation.

The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) is predicted from the same equations as a natural outcome of self-variation dynamics (Equation (5.35)).

Evolutionary Implications:

In the very early universe, from the limit (5.34) we have

and from the limit (5.23) we have

The transition to the past happens ‘smoothly’ and continuously through the laws of physics, through the Equations given by the Self-Variation Theory on the cosmological scale. From Equations (5.44) and limit (5.23),

and from Equation (5.46),

the Vacuum State is predicted as the beginning of the universe. Therefore, on a cosmological scale the universe is predicted to be flat. From Equation (5.35),

the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation is predicted. From Equation (5.36) and limit (5.34) we get,

This Equation predicts that the early universe went through a phase of ionization of atoms. From Equations (5.41),

it follows that at the beginning of the universe all its points communicated with each other. The horizon problem does not exist in the Self-Variation Cosmological Model.

The Self-Variation Theory Equations on the cosmological scale predict that the universe may be much older and much larger in size than the Standard Cosmological Model predicts. None of the Equations of the Theory puts any restriction, any limit, on the values that the redshift can take. Going back in time, while the Standard Cosmological Model converges at one point, at the Big Bang, the Self-Variation Cosmological Model diverges, predicting an early universe of large dimensions. We saw the consequences of this fundamental difference of the two Models in the comparison of their predictions, in the previous

Section 5.10. Now, a possible maximum value of the redshift affects the range of possible values of the parameter

. Assuming that the redshift takes a maximum value

, from inequality (5.22) we get

Therefore, the larger the value of , the smaller the range of possible values of the parameter . In the context of the Self-Variation Cosmological Model, the value of the parameter is the one related to the age of the universe. We remind that this parameter increases slightly over time, according to Equation (5.9). Thus, as the parameter increases tending to , and for small redshift values the curve as given by Equation (5.26) tends to become straight,

and with Equation (5.20) we have,

. (5.47)

This straight line is recorded in the cosmological data as early as Hubble’s empirical/observational law and corresponds to a long age of the universe. Going back in time, the straight line observed today is transformed into a curve. This transformation takes place until the ever-increasing Bohr radius and decreasing ionization energy do not allow the creation of the hydrogen atom. From Equation (5.20) we get

and substituting into Equation (5.26) we get

. (5.48)

Taking the values and , from Equation (5.47) we get,

( ) (5.49)

and from Equation (5.48) we get,

( ) (5.50)

In these Equations the distance is measured in . From inequality (5.22) we get,

. (5.51)

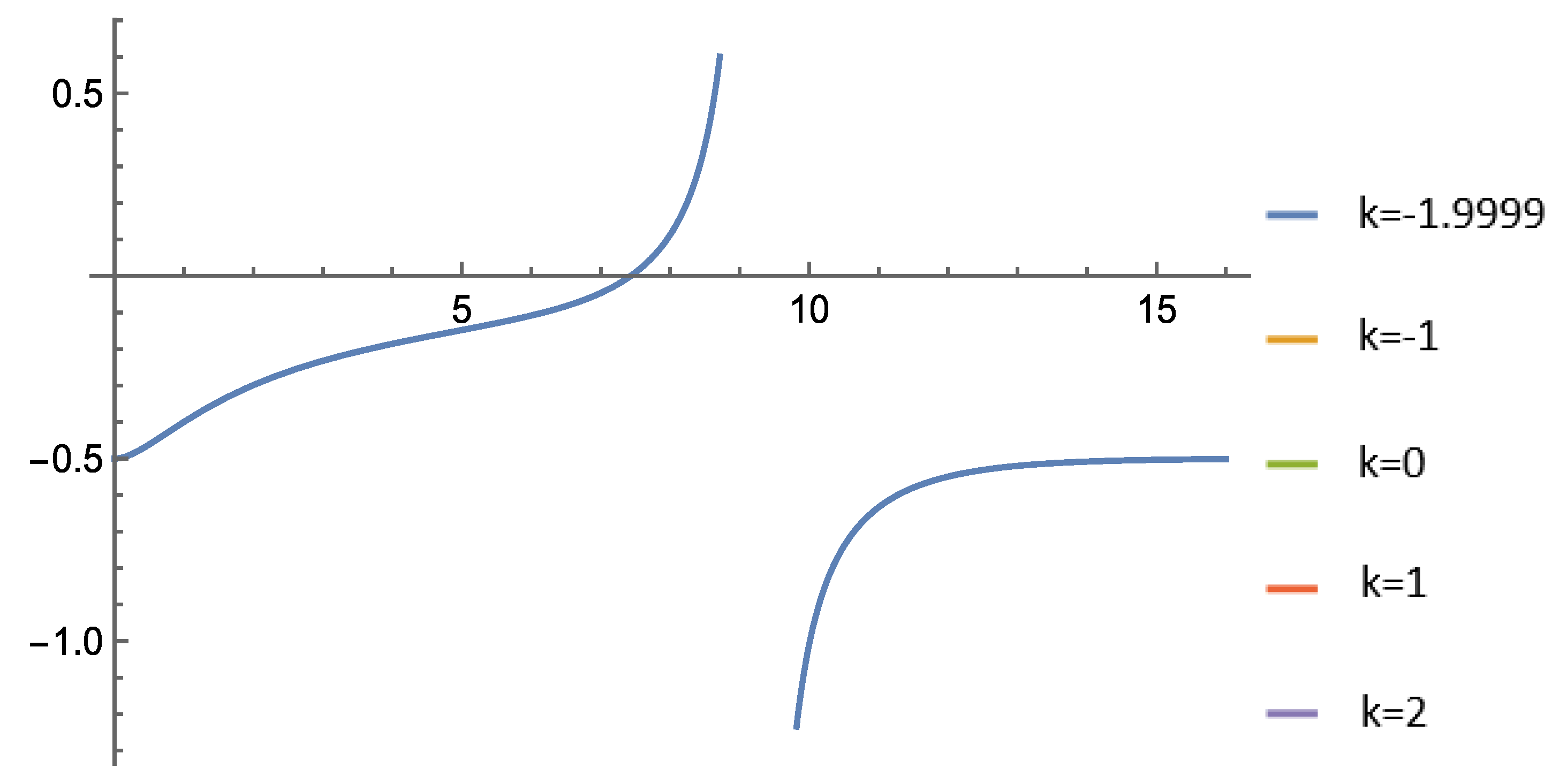

If , from Equation (5.50) we get,

and from inequality (5.51) we get

. If

, from Equation (5.50) we get,

and from inequality (5.51) we get

. If

, from Equation (5.50) we get,

and from inequality (5.51) we get

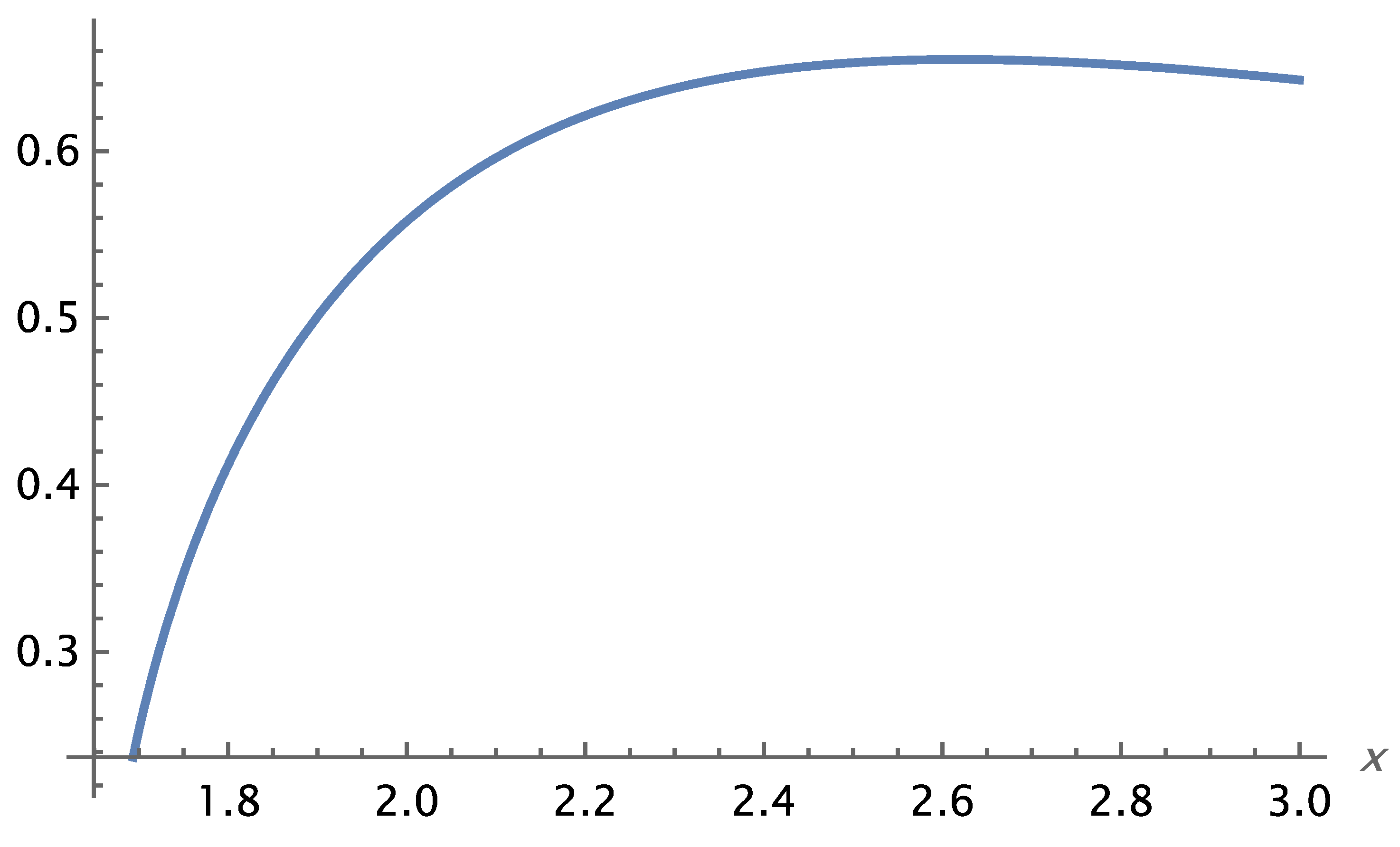

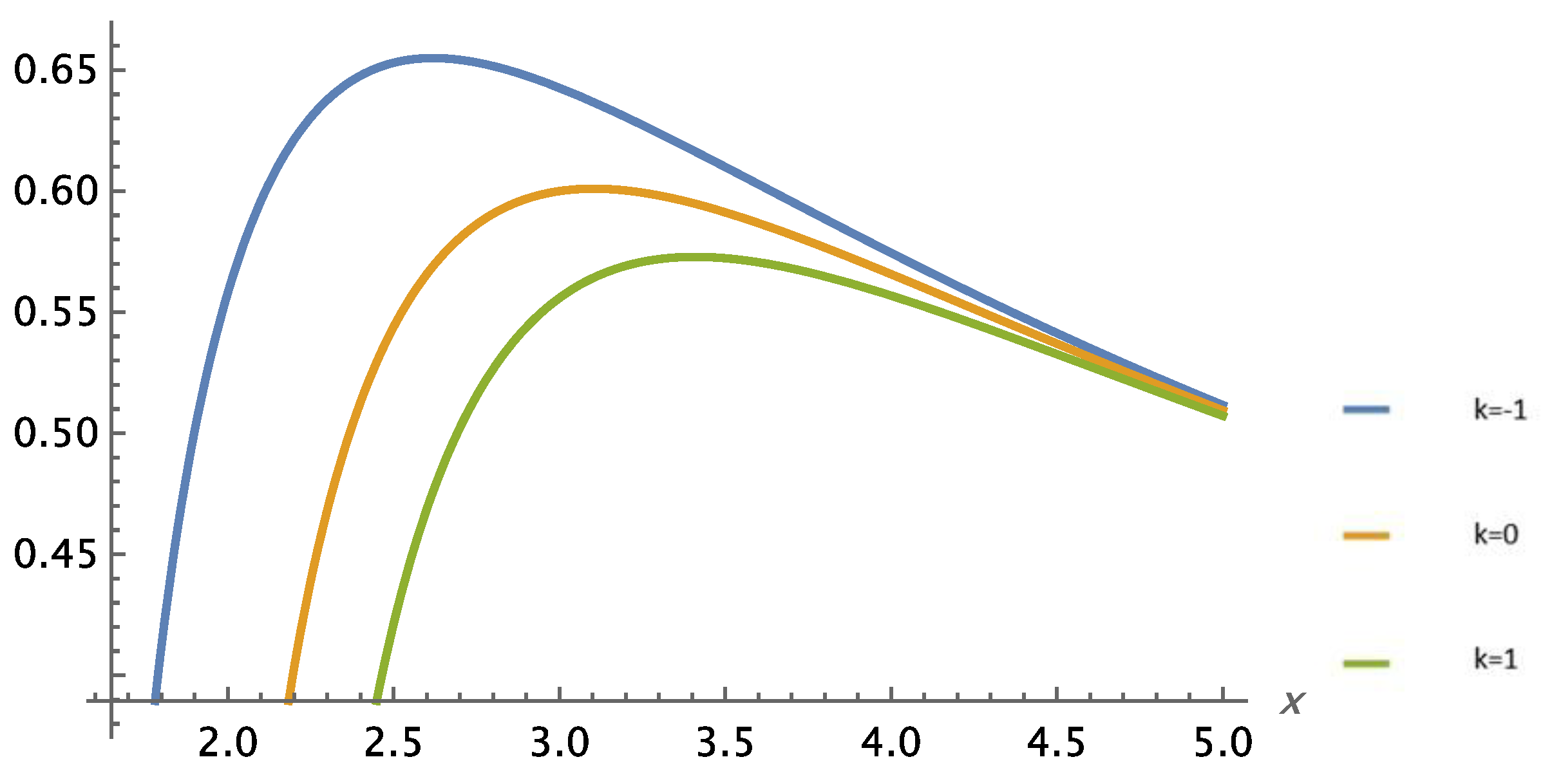

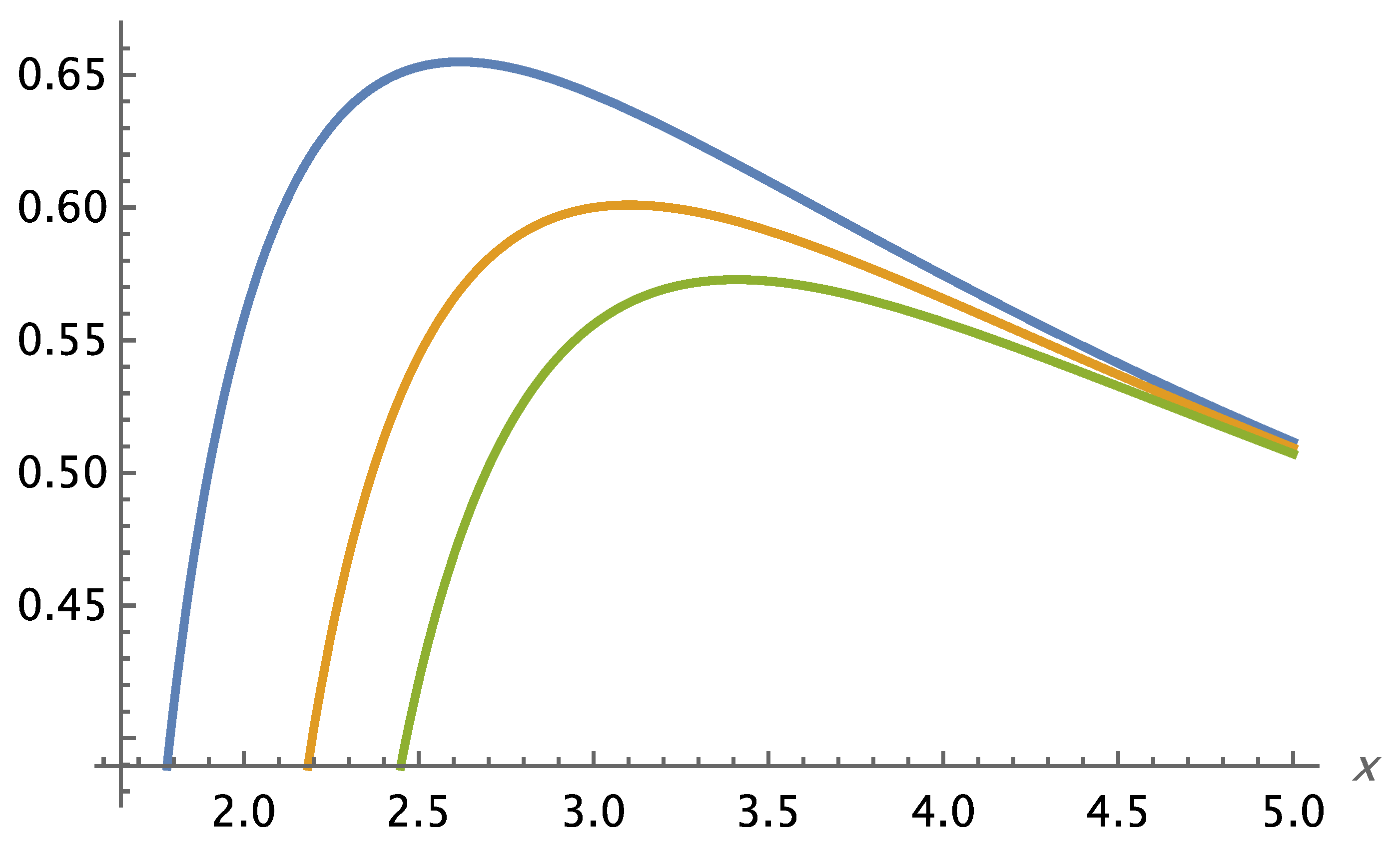

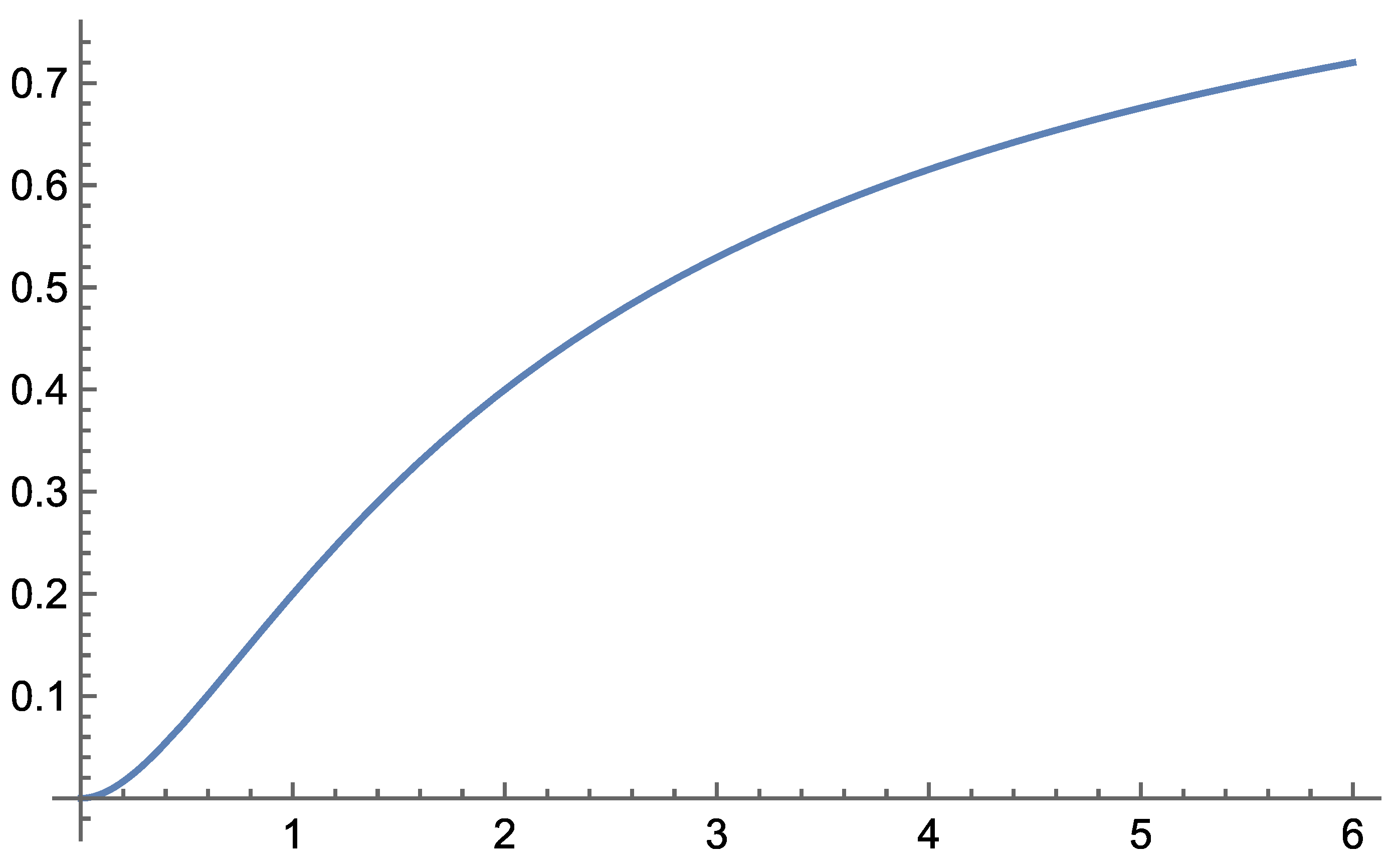

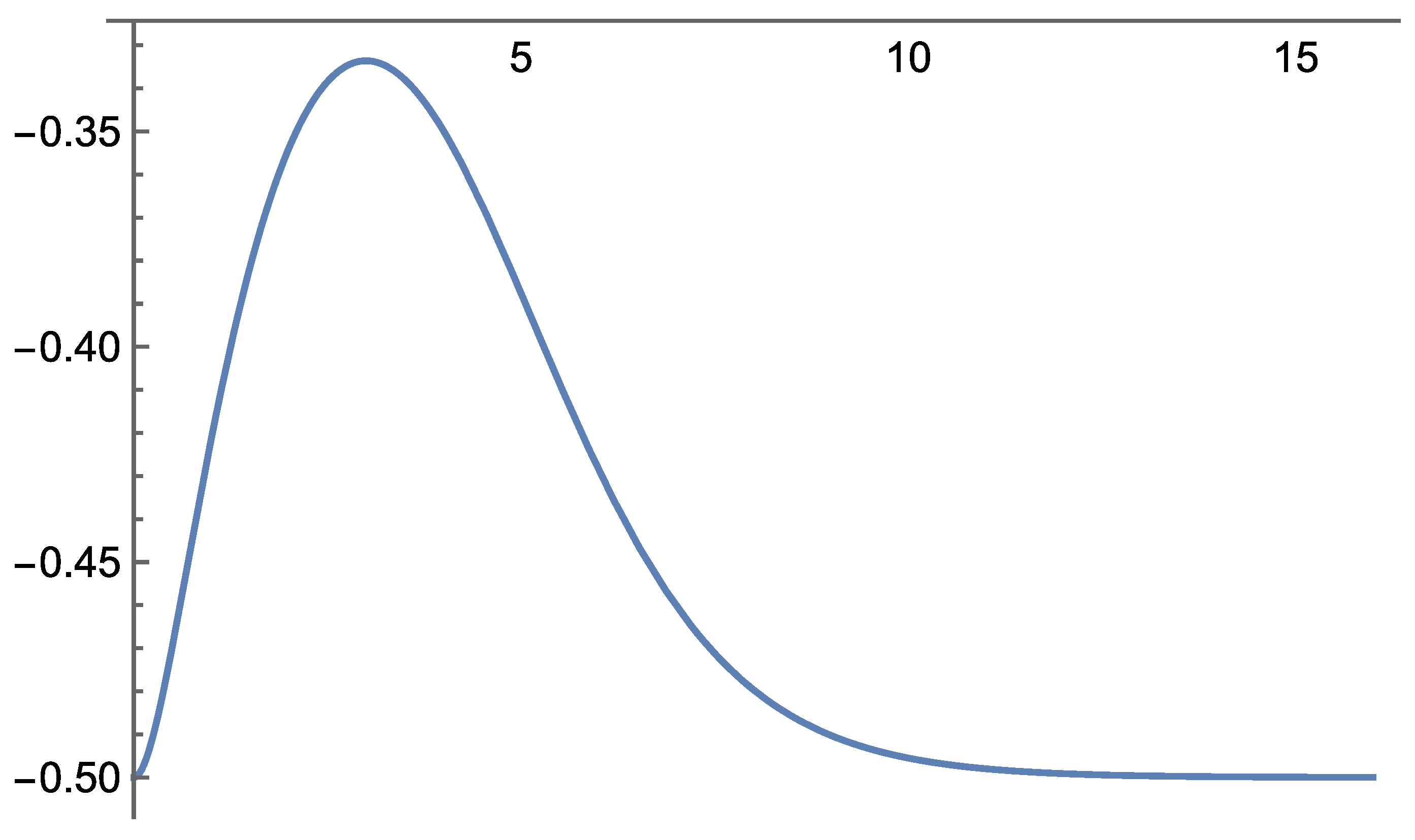

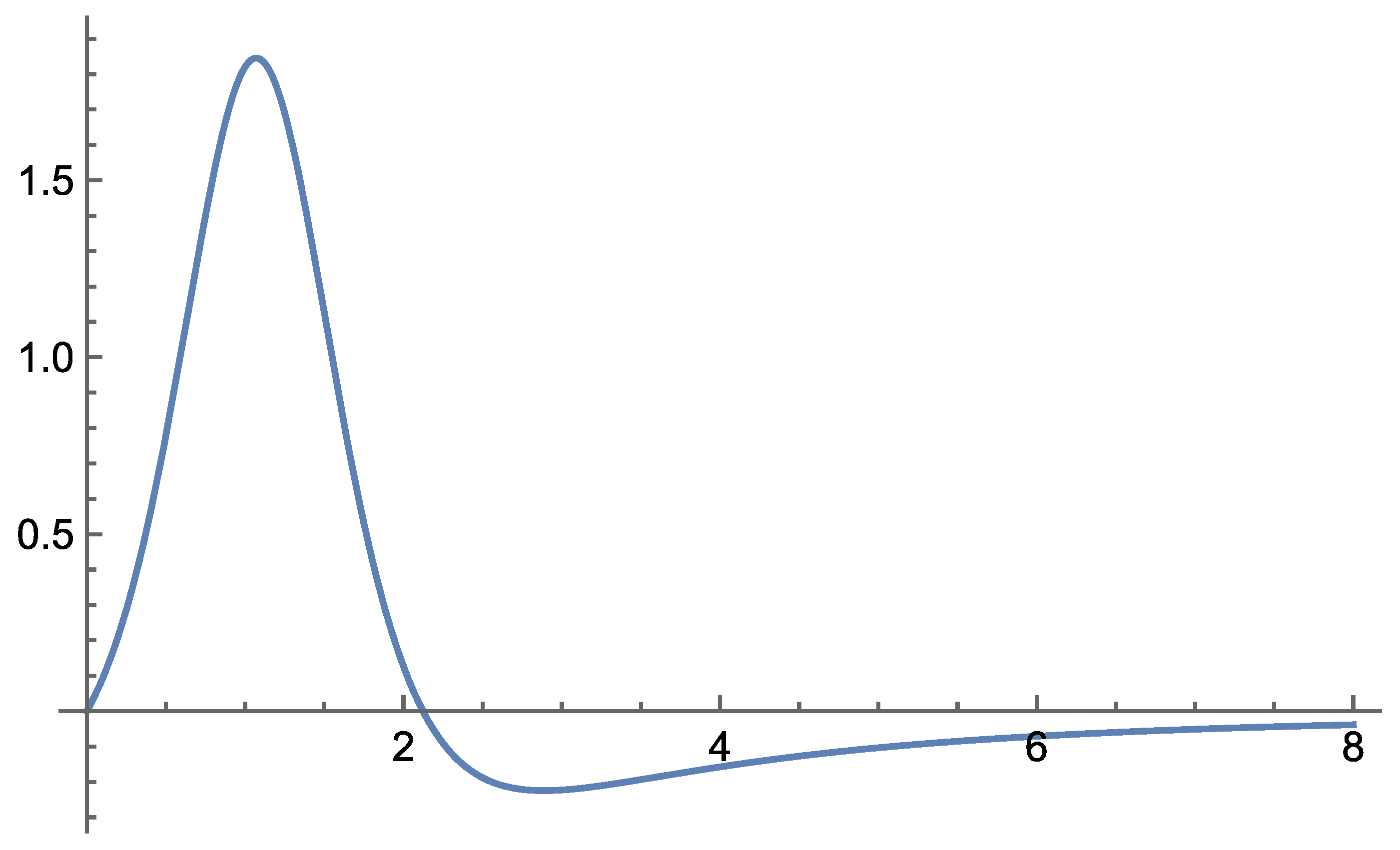

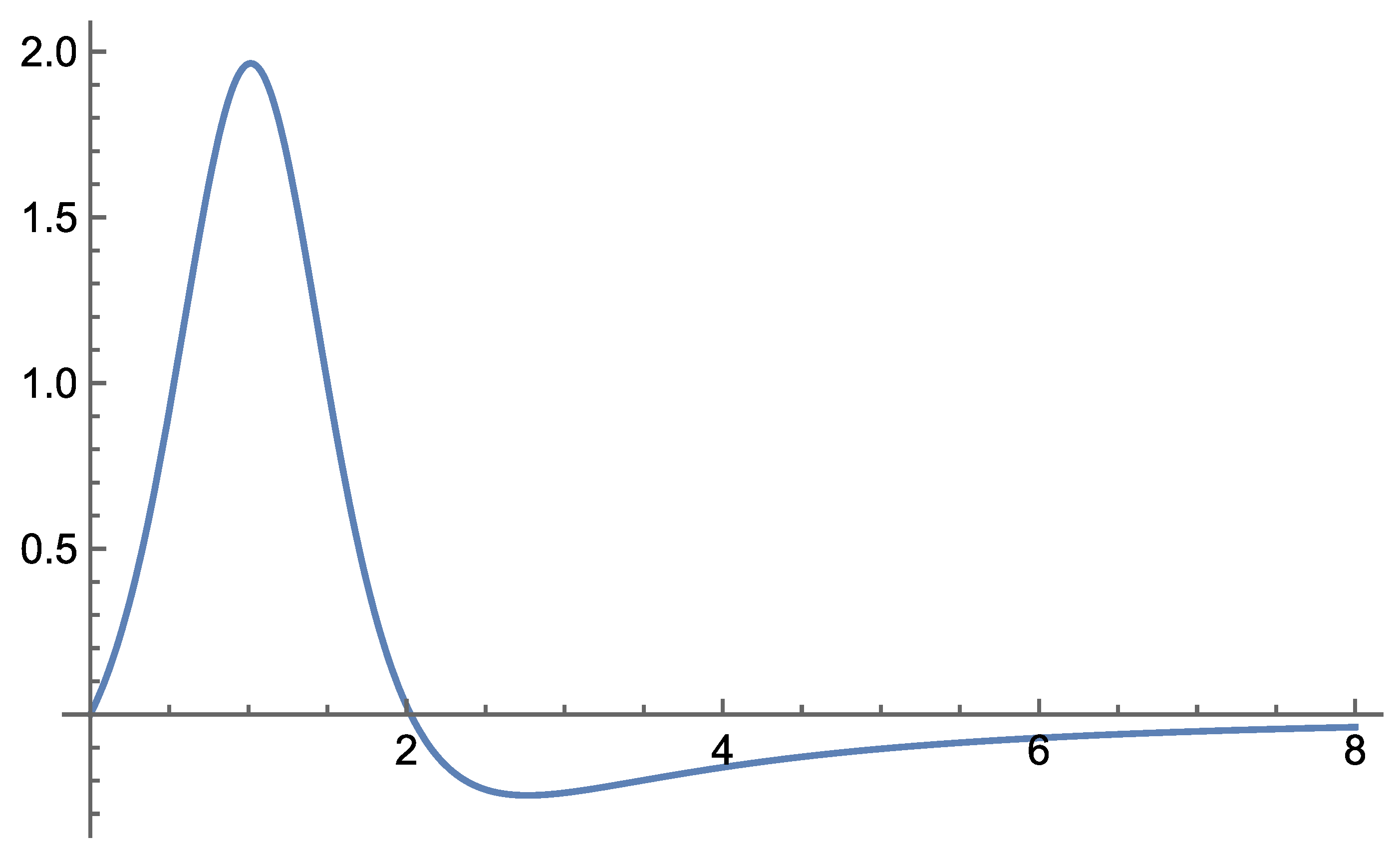

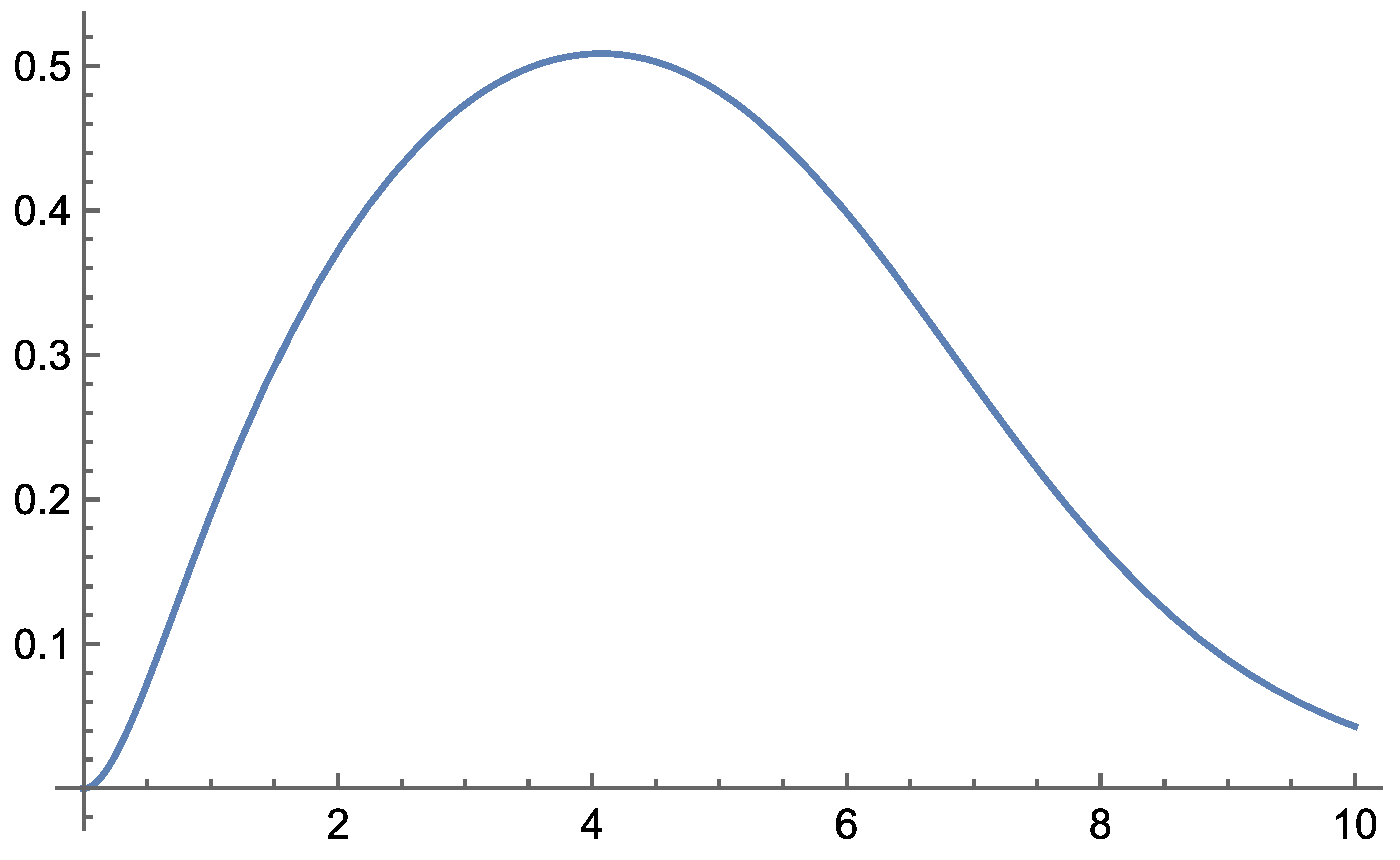

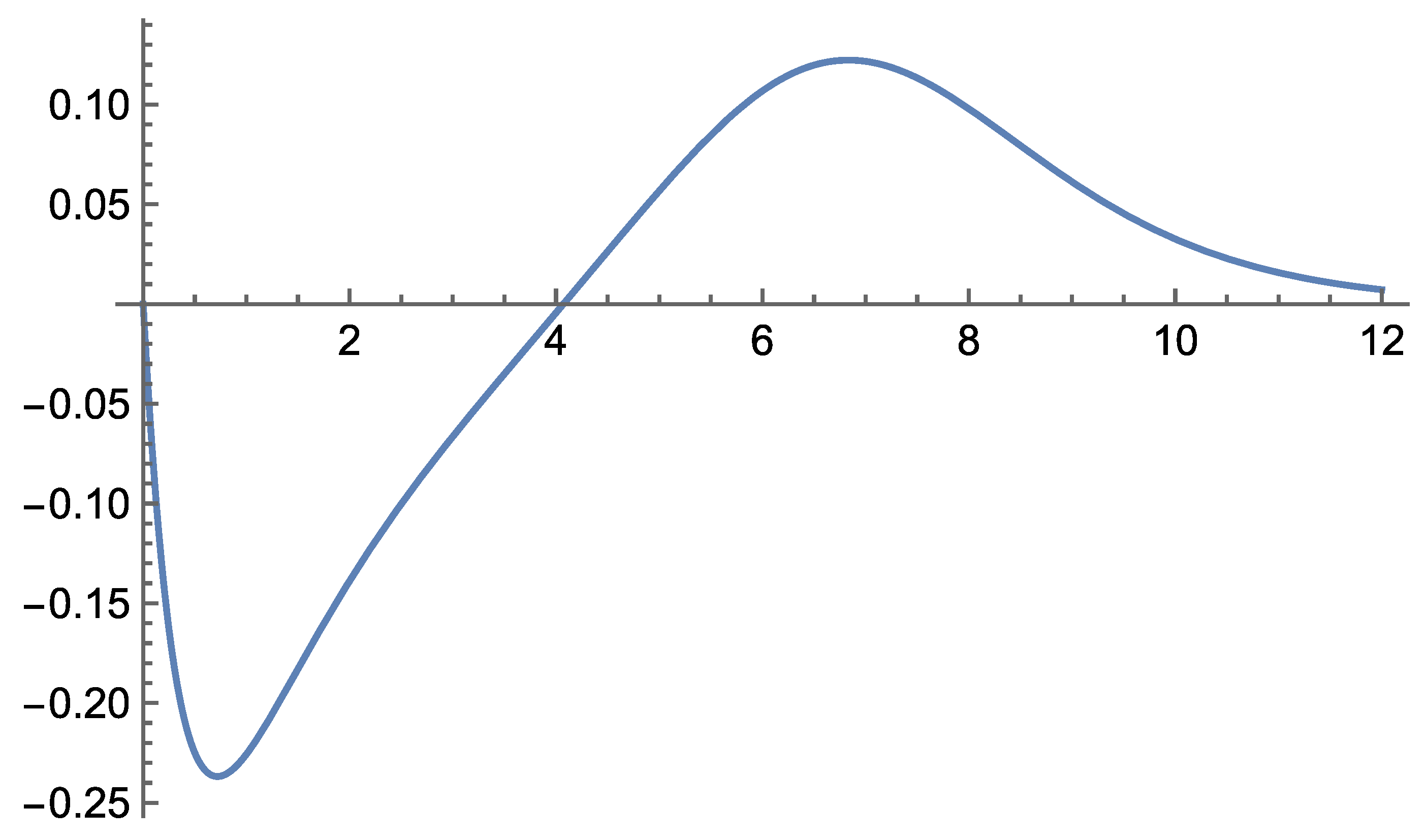

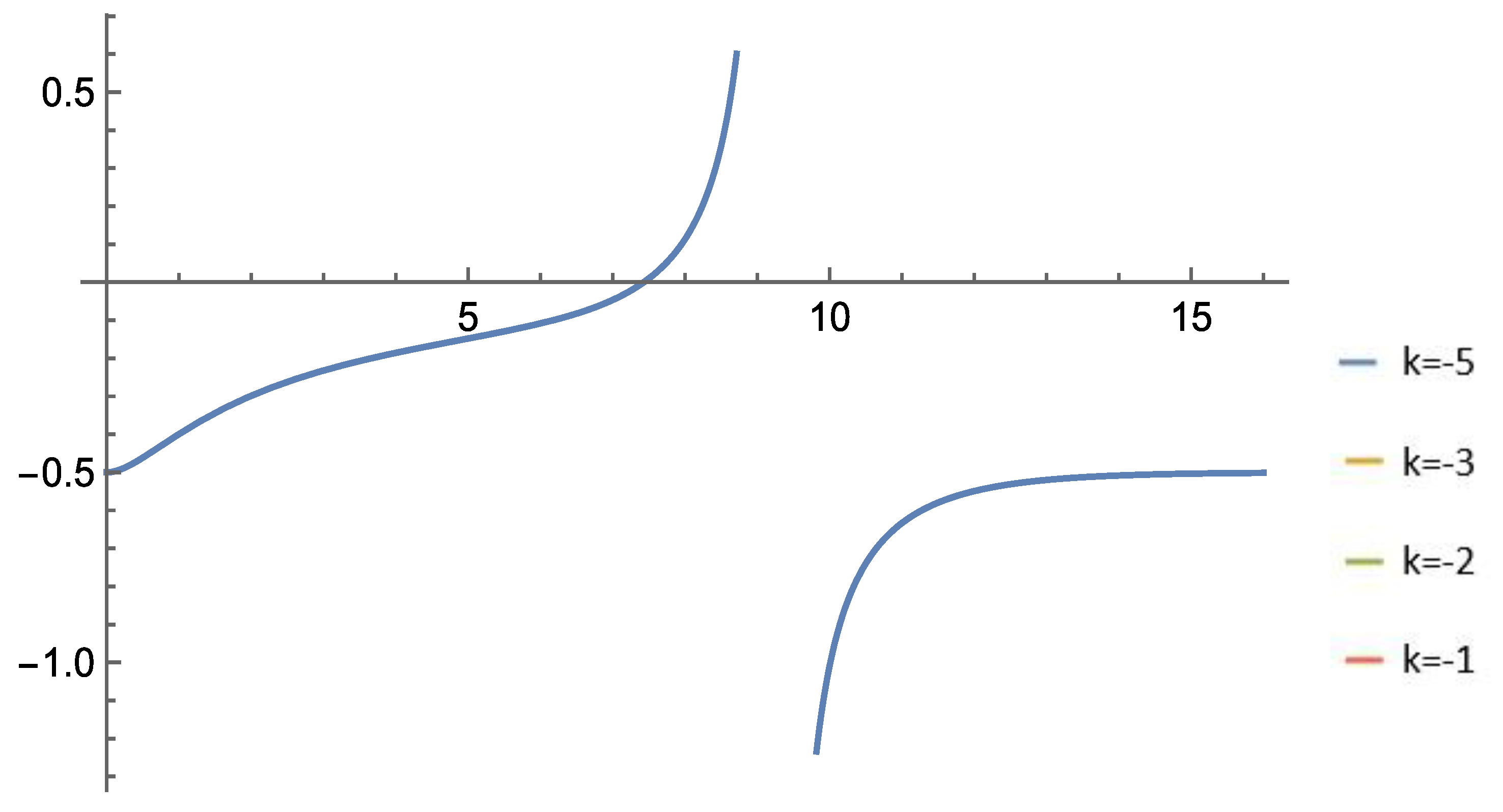

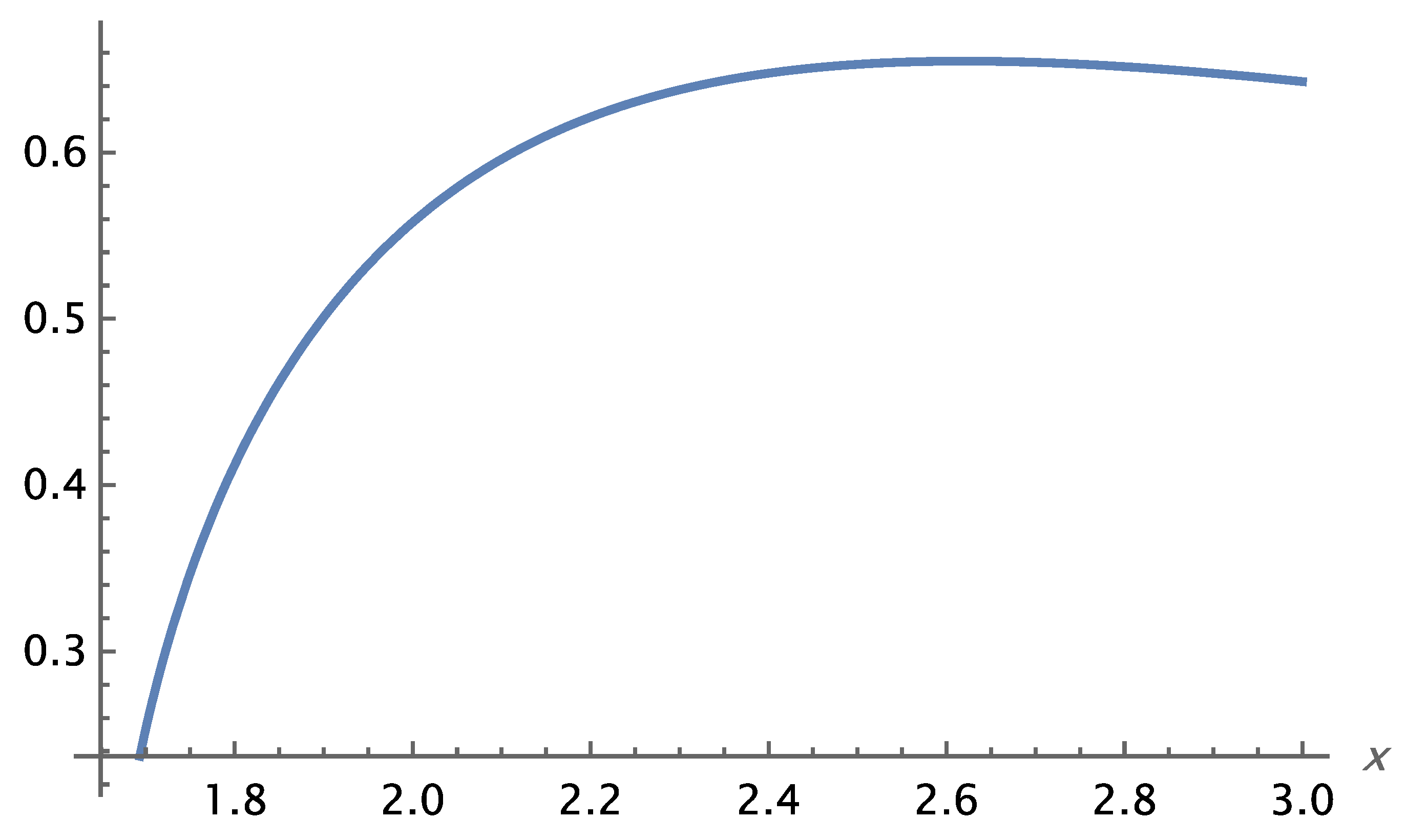

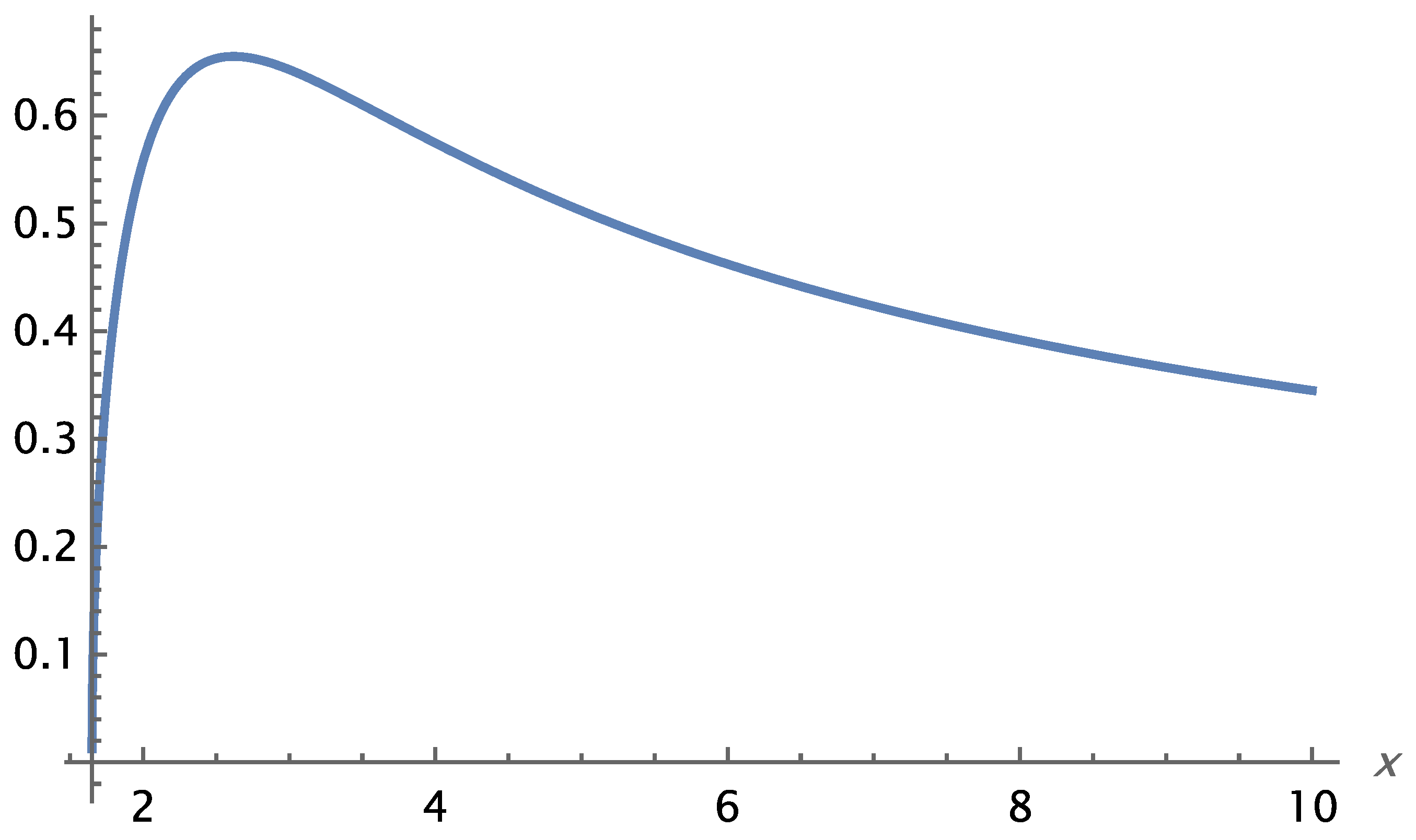

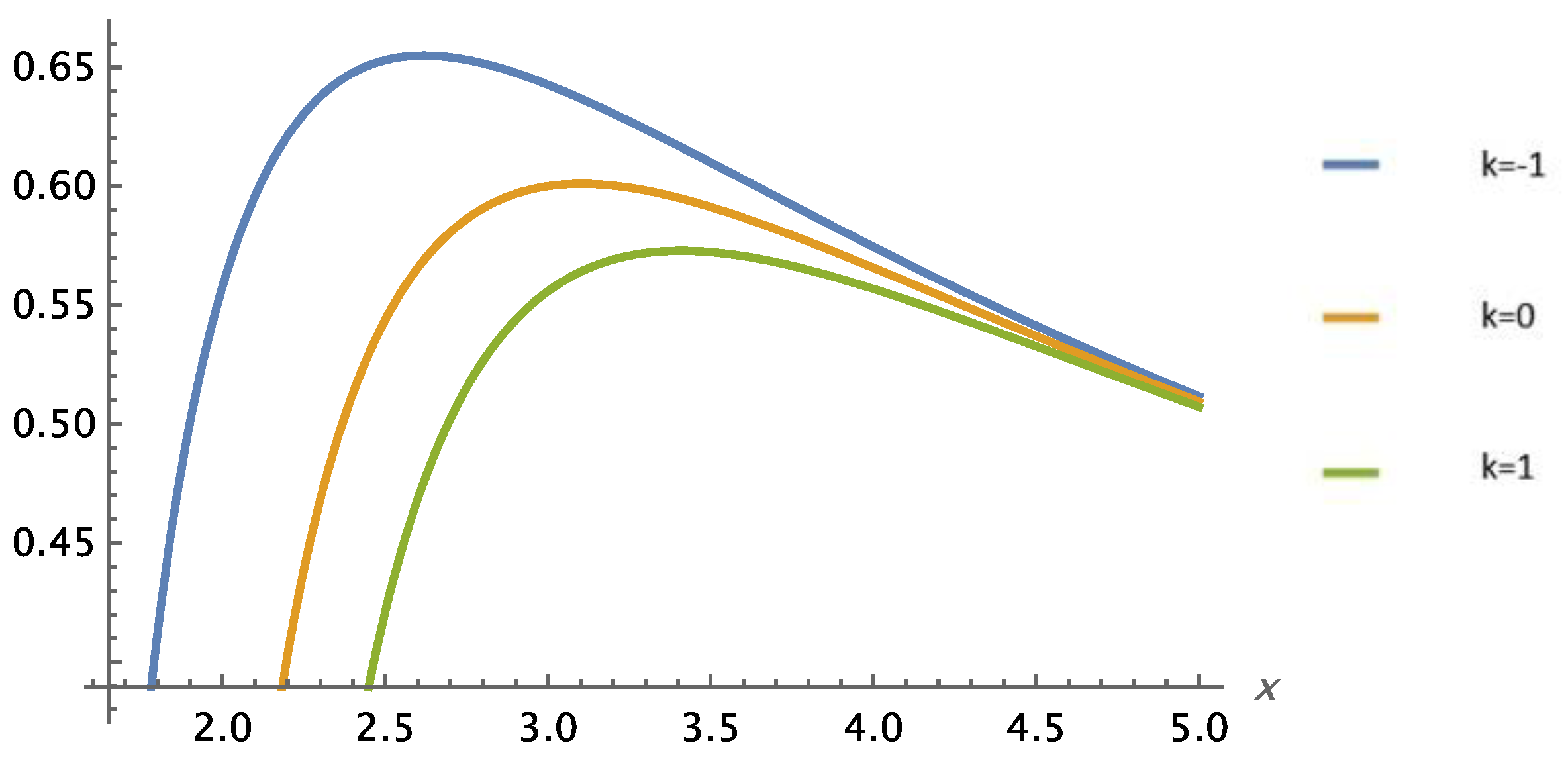

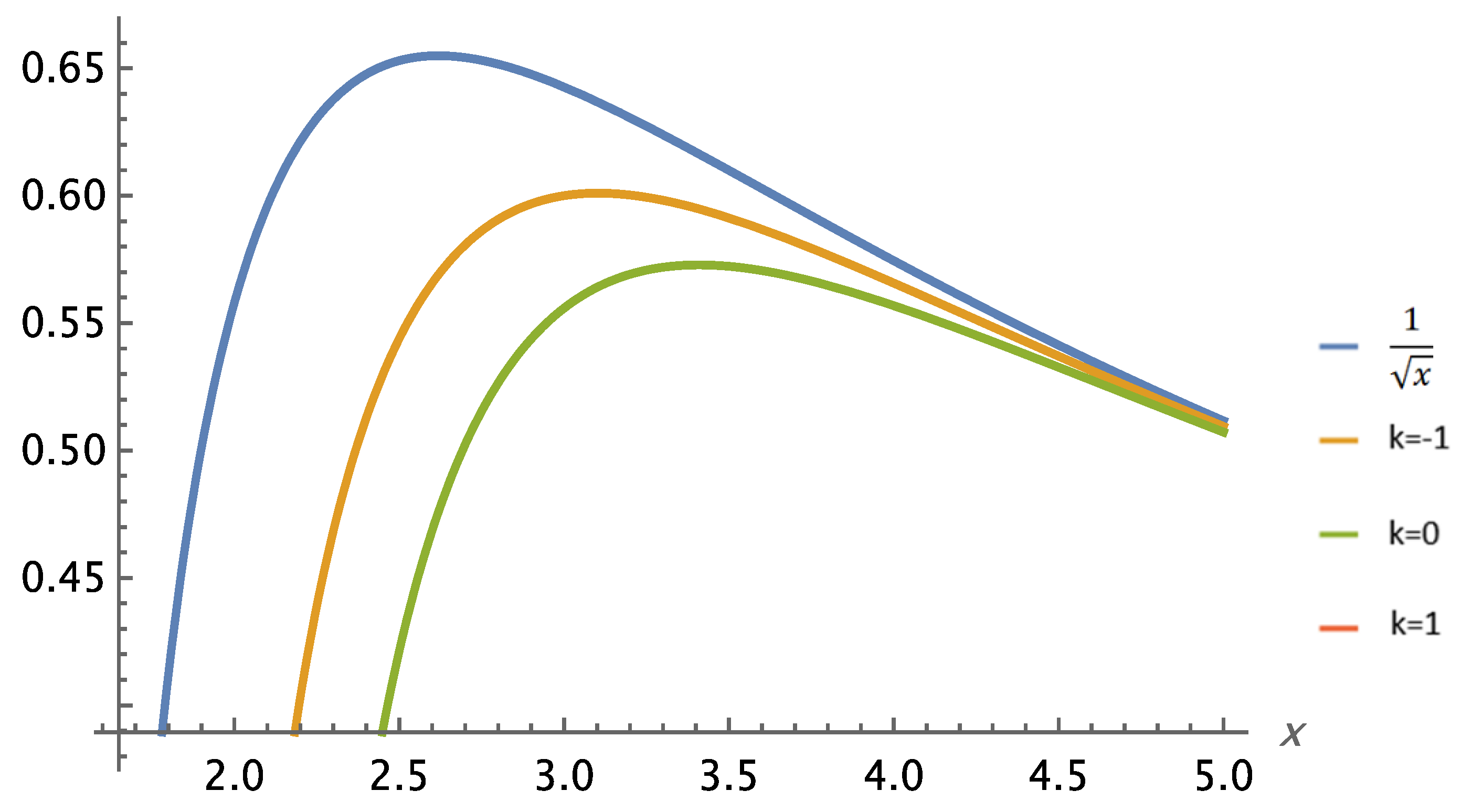

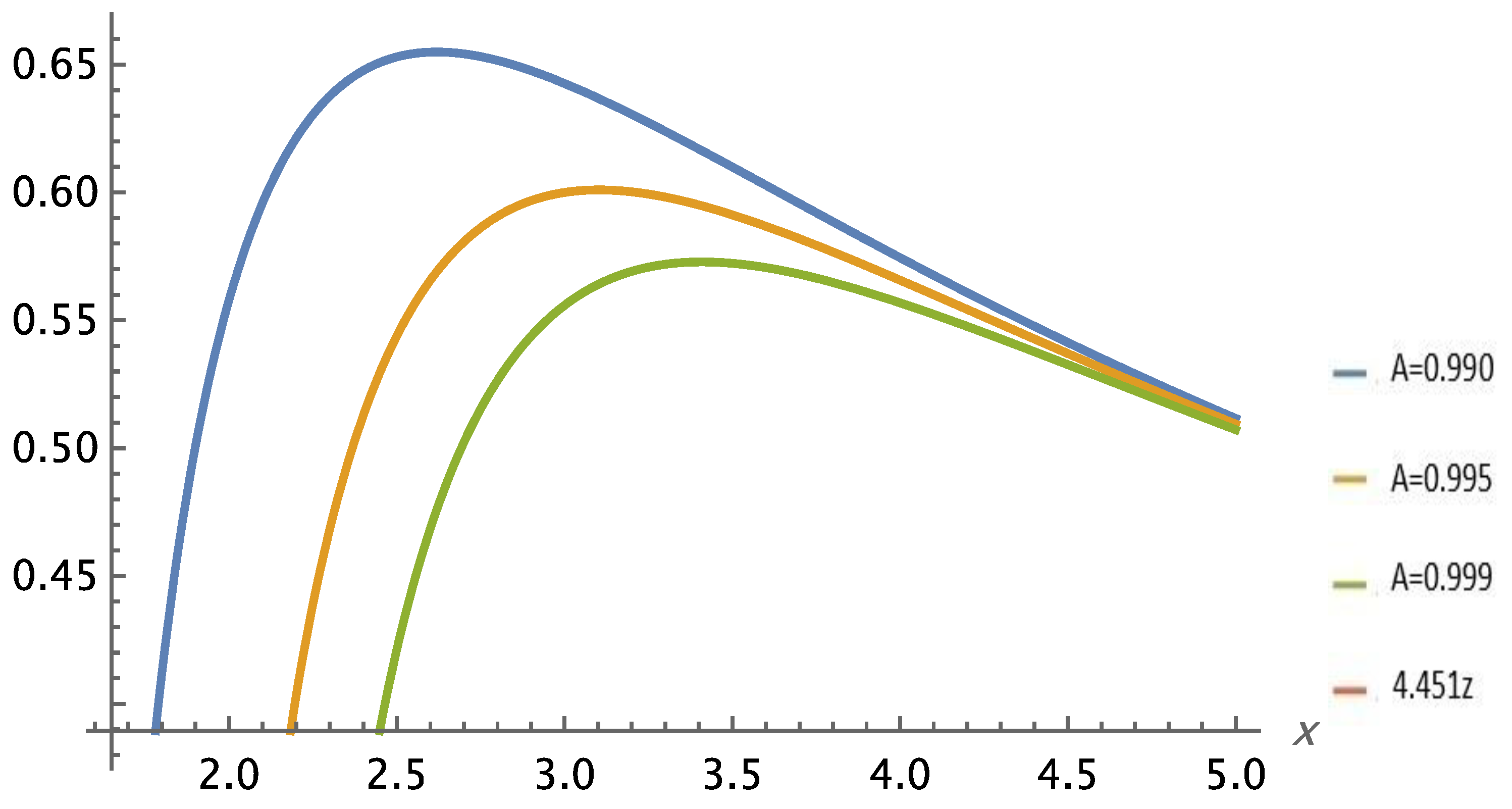

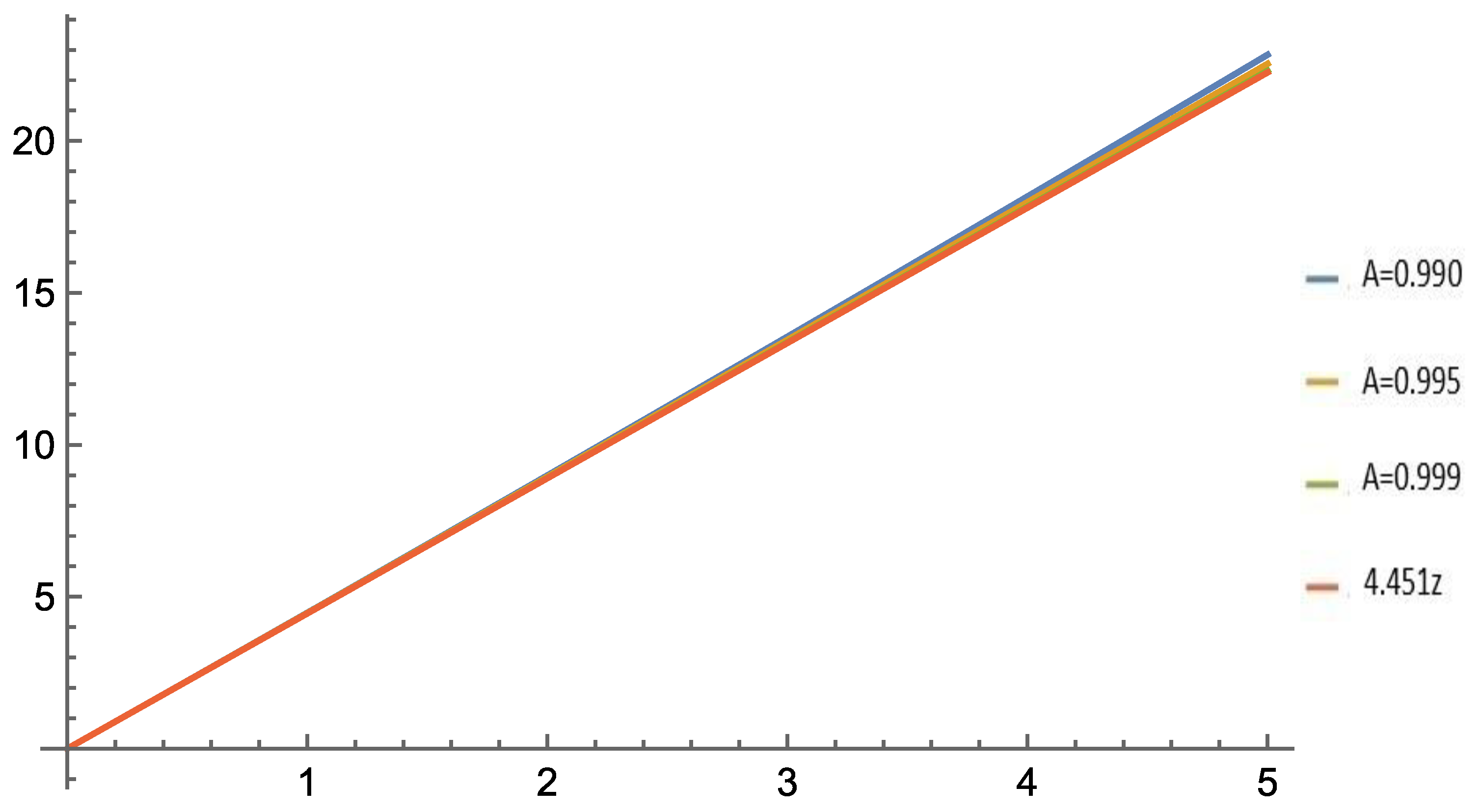

. In Figure 5.1 we have the graph of the function (5.48) if

,

,

and of Hubble’s empirical/observational law (5.49) for the value

of the homonymous constant, from

to

. For this value of the redshift, Equation (5.50) is applied for all three values of parameter

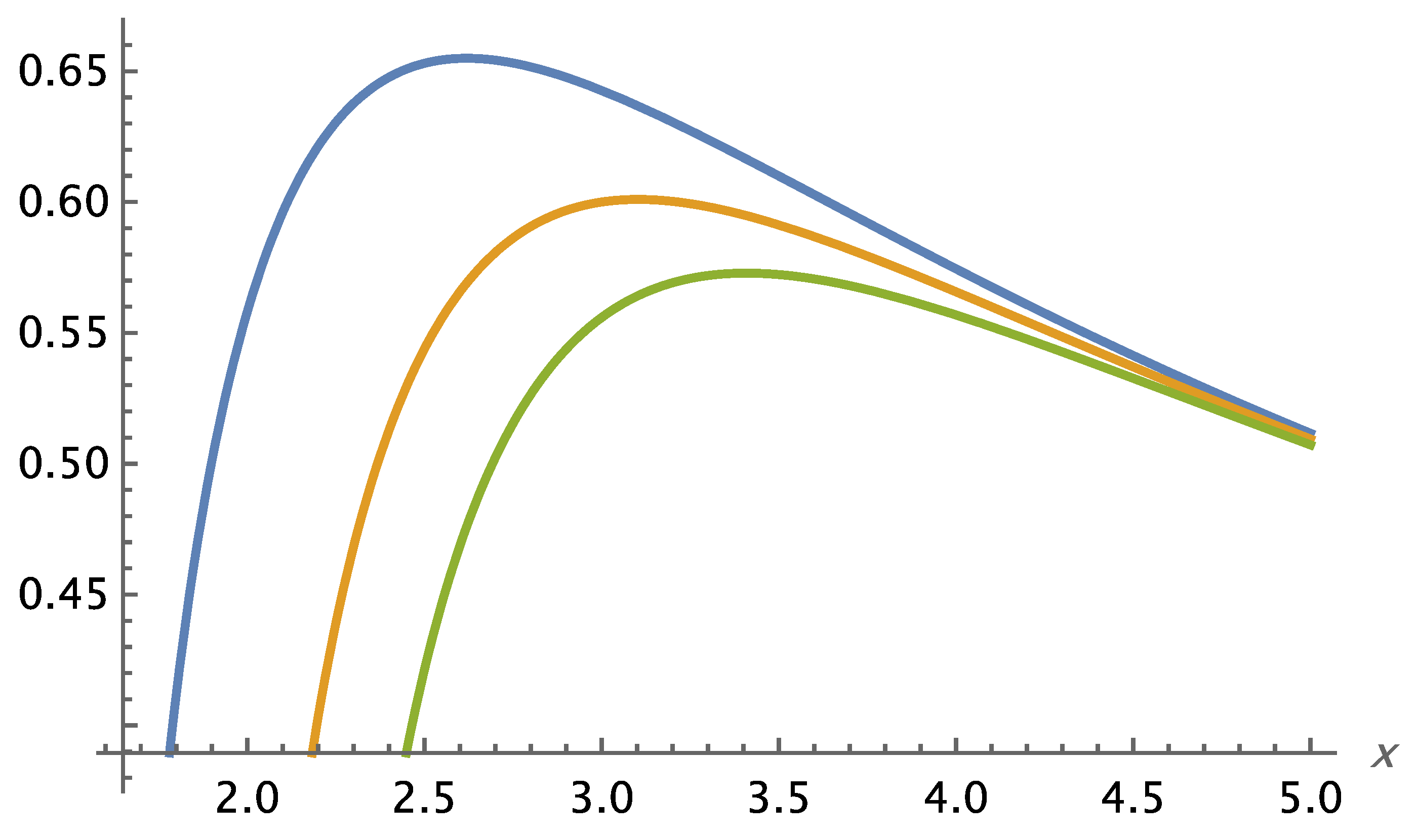

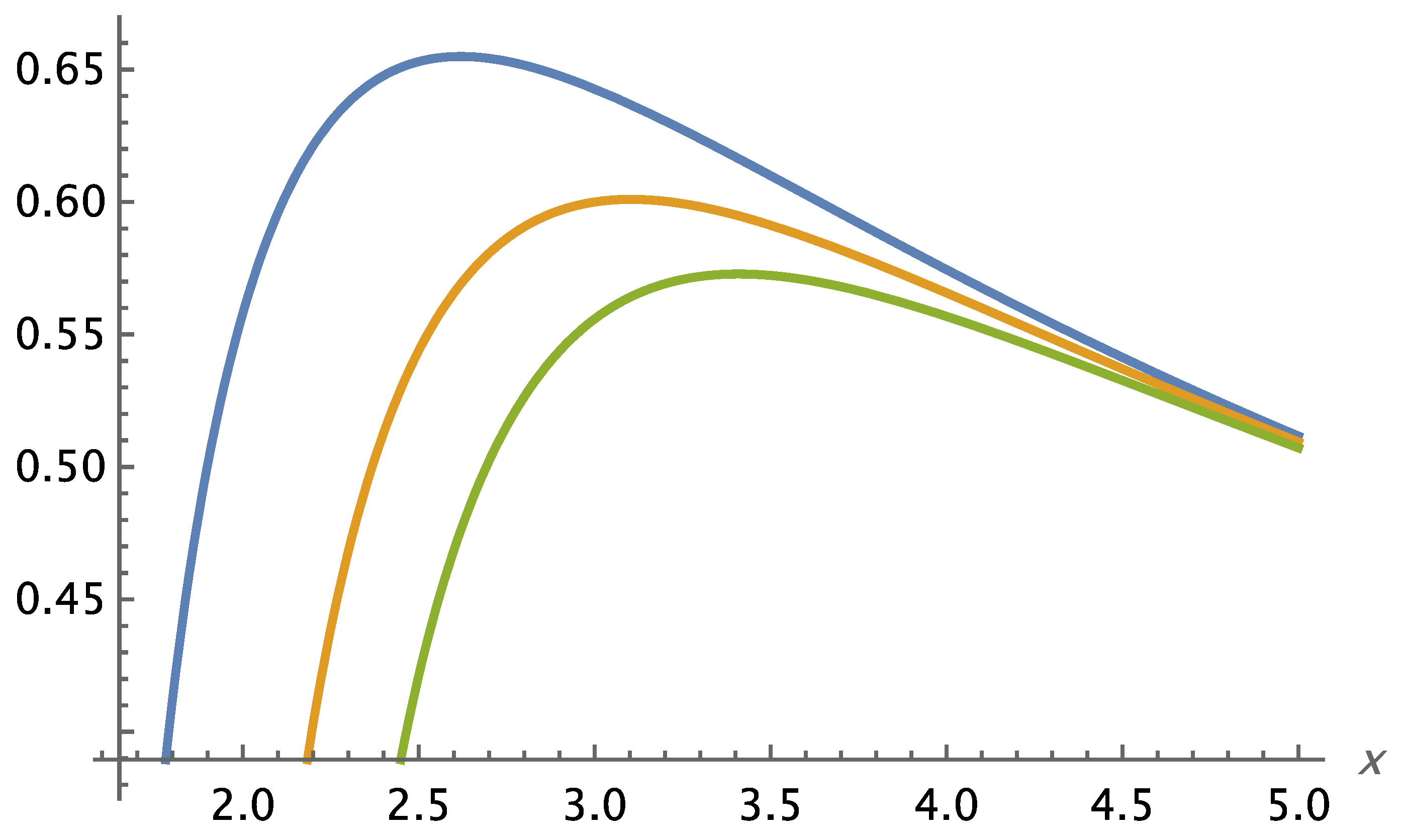

that we have chosen,

. From Equations (5.36) and (5.42) we have

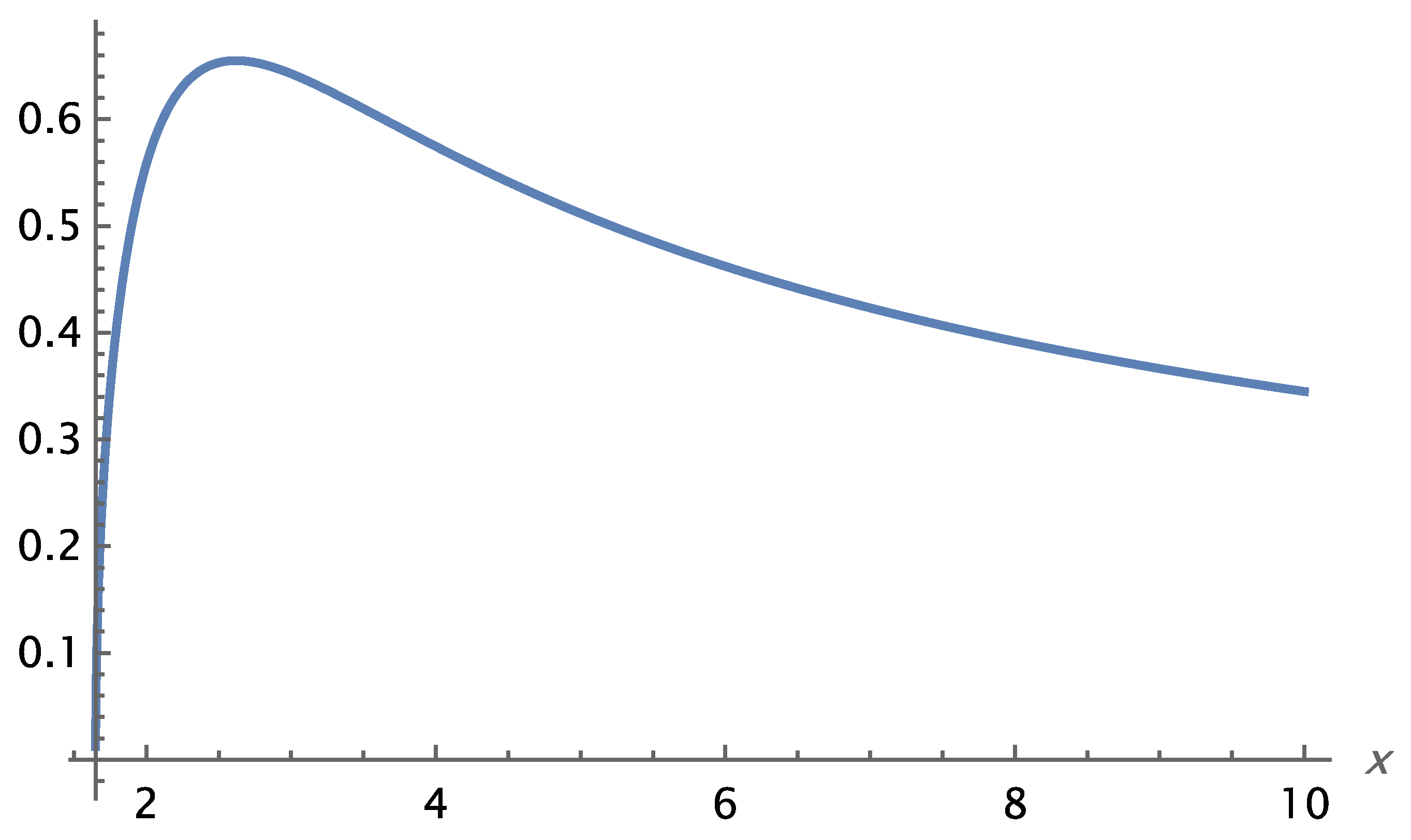

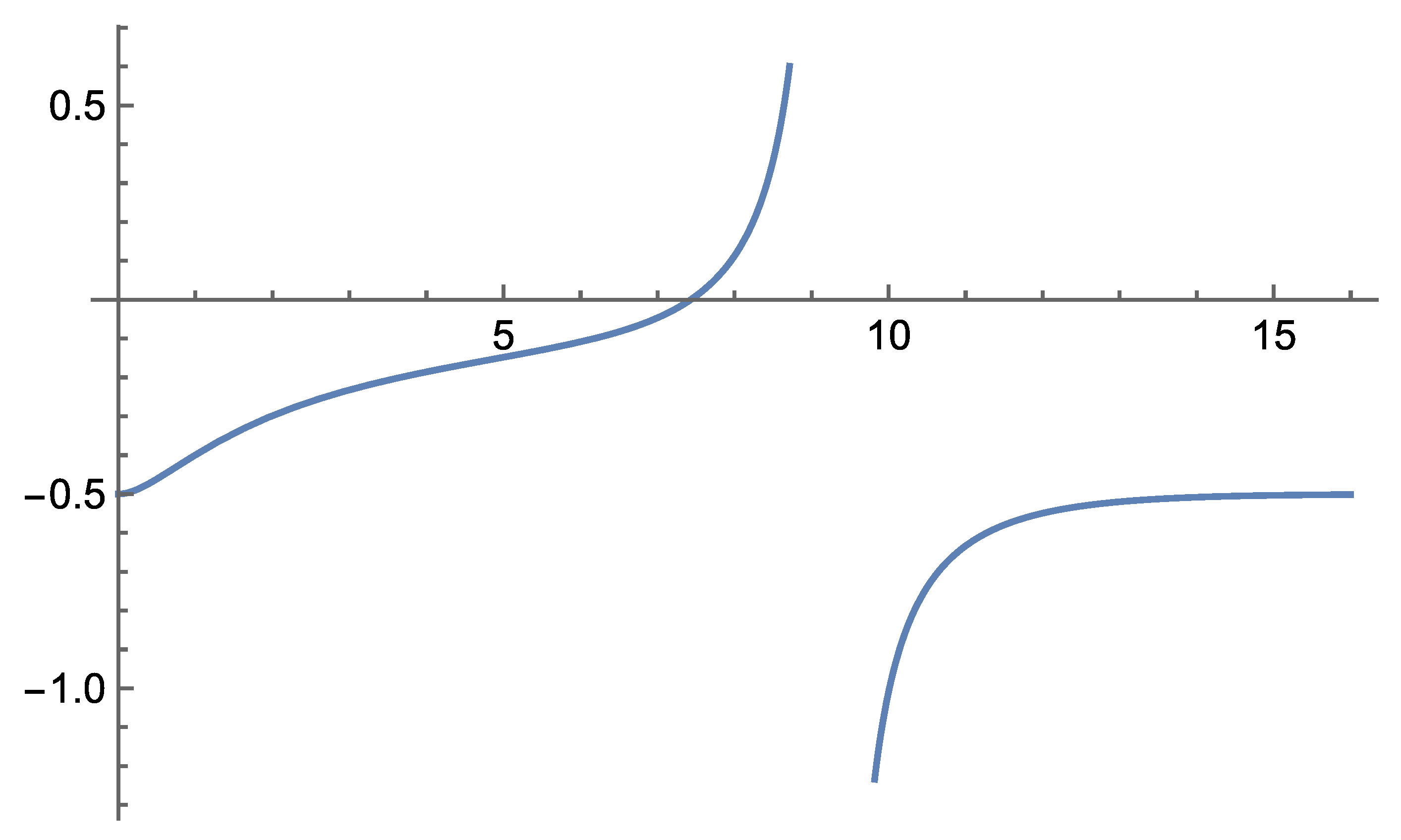

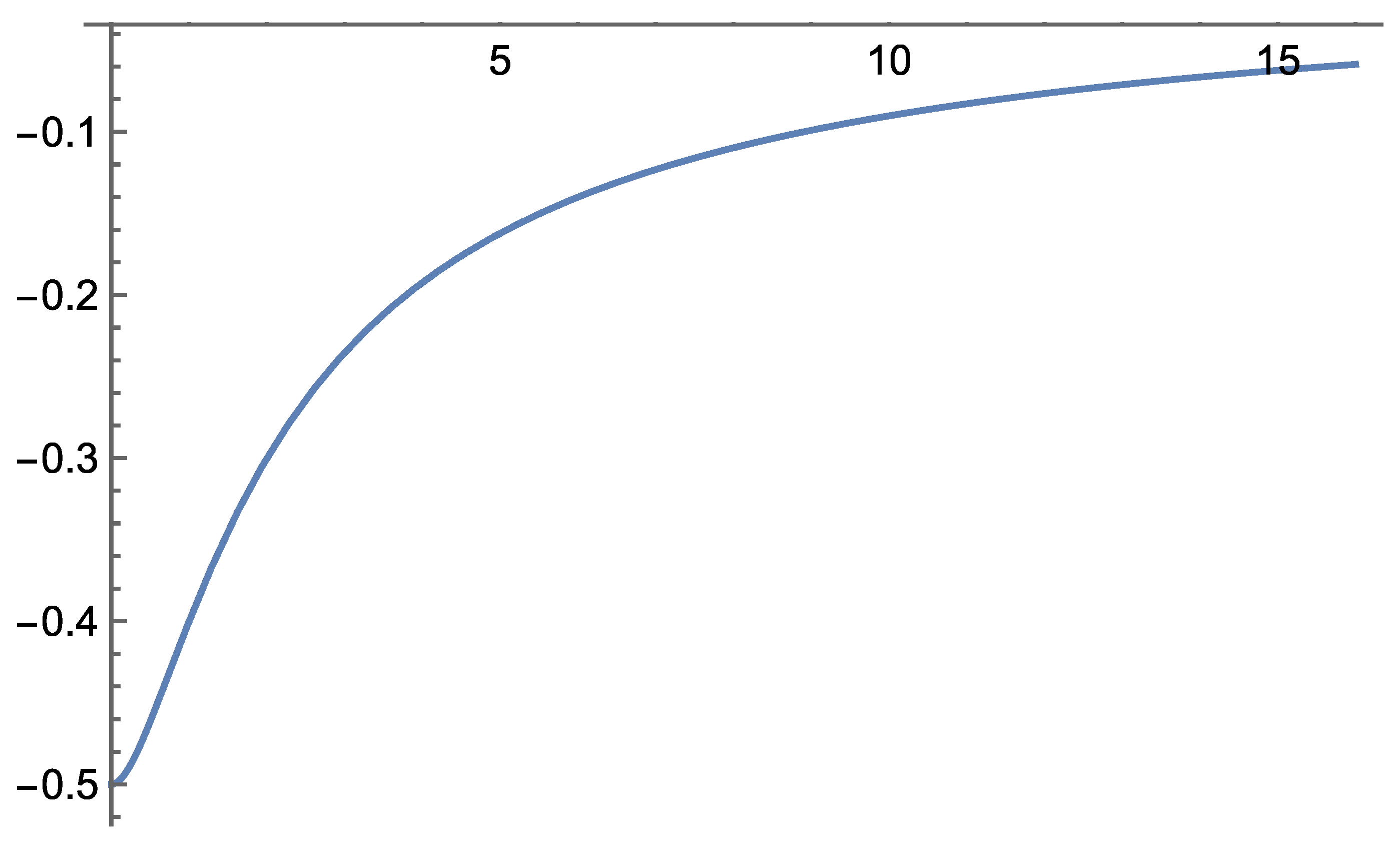

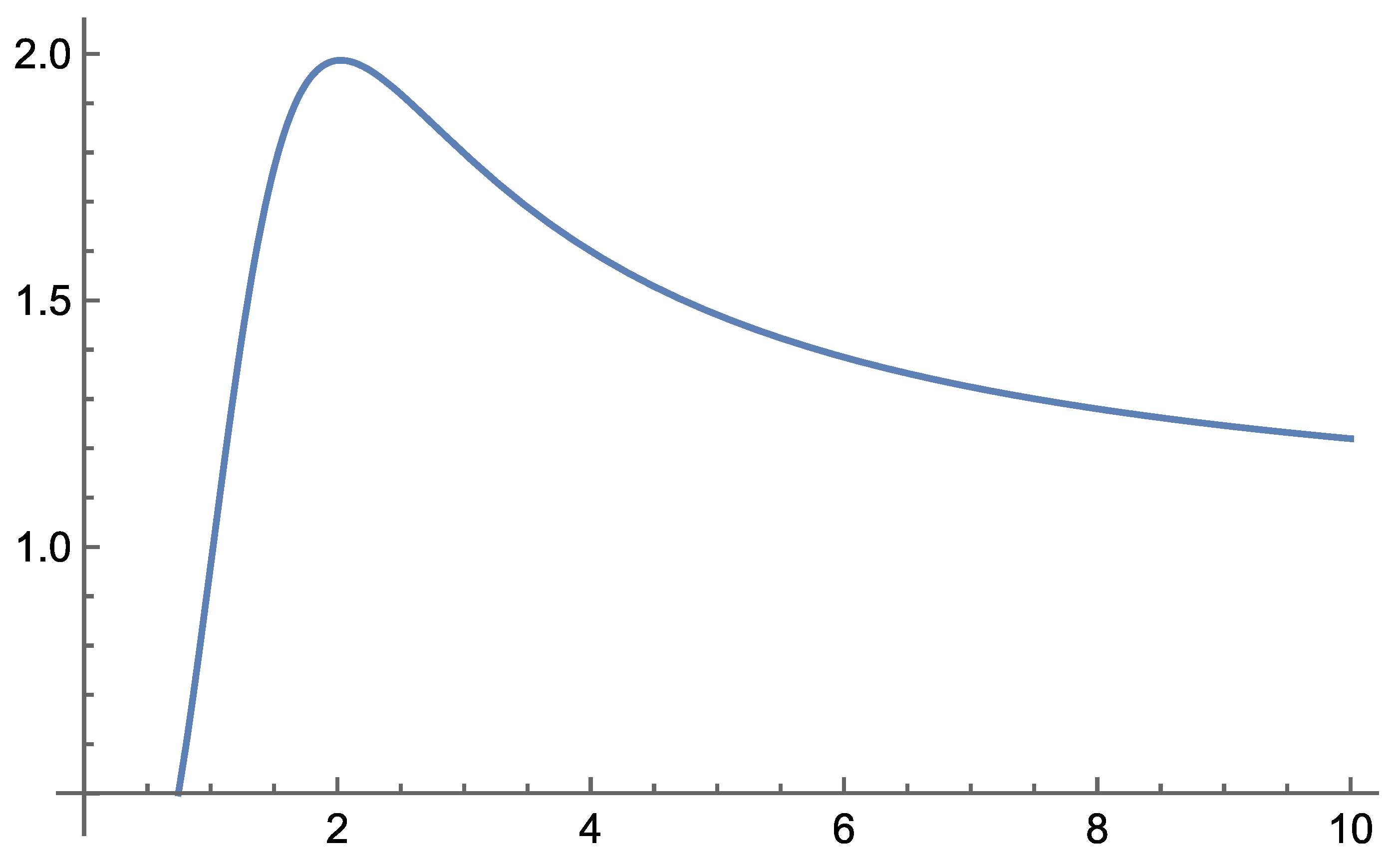

respectively. We assume that for these values of ionization energy and Bohr radius, the prevailing conditions allow the formation of the chemical elements. In Figure 5.1 we can see that as the value of increases, Equation (5.50) tends to Hubble’s empirical/observational law (5.49). Also, Equation (5.50) gives greater distances than Equation (5.49),

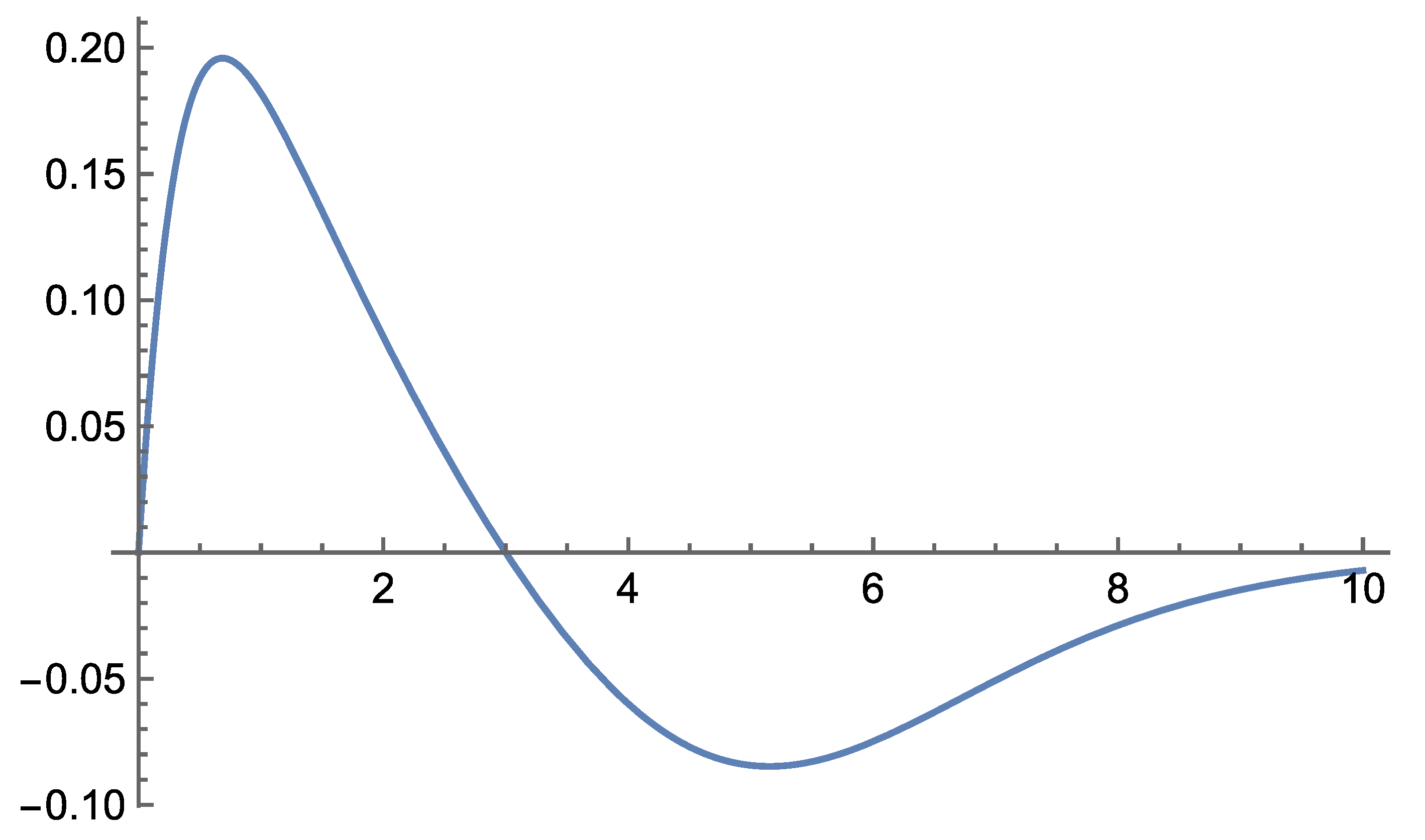

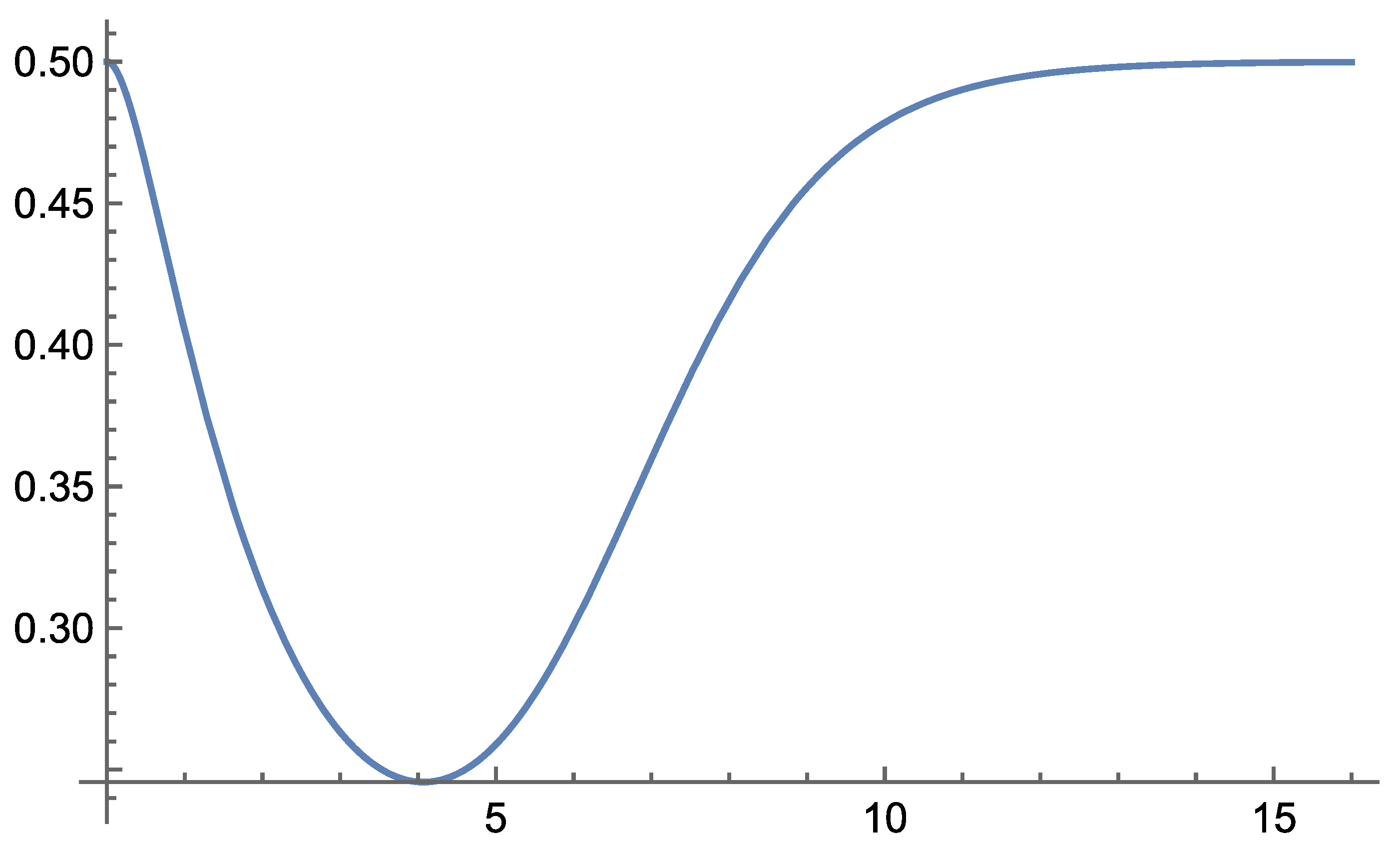

As shown in Figure 5.2, for small values of redshift, the three graphs of Equation (5.50) almost coincide with the straight line (5.49). Measuring the parameters and in Equation (5.26) requires measurements at large values of the redshift. Such measurements can also show the consequences of Equations (5.33), (5.42) and (5.33). Above a value of redshift, the chemical elements have not been created, so there is no linear spectrum of electromagnetic radiation, while the uncertainty of the electron position takes on very large values in an opaque universe. The implications of these Equations are documented in the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, the first observation from the Vacuum State.

As the available observing instruments evolve, the measurements are getting closer and closer to the Vacuum State. The Self-Variation Theory gives the parameters of astrophysics as a function of redshift. Hence, we have the theoretical background to make targeted measurements at all cosmological-scale distances. However, there are measurements that require knowledge of the distance of an astronomical object. In the recent past, in the regions of the universe from which we obtain a linear electromagnetic spectrum, the distance on a cosmological scale is given by Equation (5.26). A necessary condition for the use of this Equation is the measurement of the value of the constant and of the parameter .

Figure 5.1.

The predicted distance of distant astronomical objects as a function of redshift depends on the value of the parameter . Source: Figure by author.

Figure 5.1.

The predicted distance of distant astronomical objects as a function of redshift depends on the value of the parameter . Source: Figure by author.

Figure 5.2.

The prediction of the distance of astronomical objects, in , for small values of redshift. Source: Figure by author.

Figure 5.2.

The prediction of the distance of astronomical objects, in , for small values of redshift. Source: Figure by author.

The Self-Variation Cosmological Model (SVCM) presents a fundamentally different approach to understanding the universe compared to the Standard Cosmological Model (SCM). While the SCM relies on the assumption of fixed physical constants and explains redshift through the expansion of space, the SVCM attributes redshift to the variation of particle properties—most notably the electron mass and charge—over cosmological time and distance.

This foundational shift allows the Self-Variation Theory to provide natural explanations for several longstanding issues in cosmology, such as:

The horizon problem, without invoking inflation;

The absence of magnetic monopoles, as a consequence of Maxwell's laws remaining valid under self-variation;

The flatness and uniformity of the universe;

The missing dark matter, by reproducing galactic rotation curves through its own gravitational equations;

The variation in the fine structure constant, as a direct prediction rather than an anomaly;

The Hubble tension, as a result of measuring cosmological parameters without accounting for the variation of particle masses.