Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Manufacturing Outsourcing and Contract Manufacturing

2.2. Manufacturing Frameworks

2.3. The Gap in CM Literature

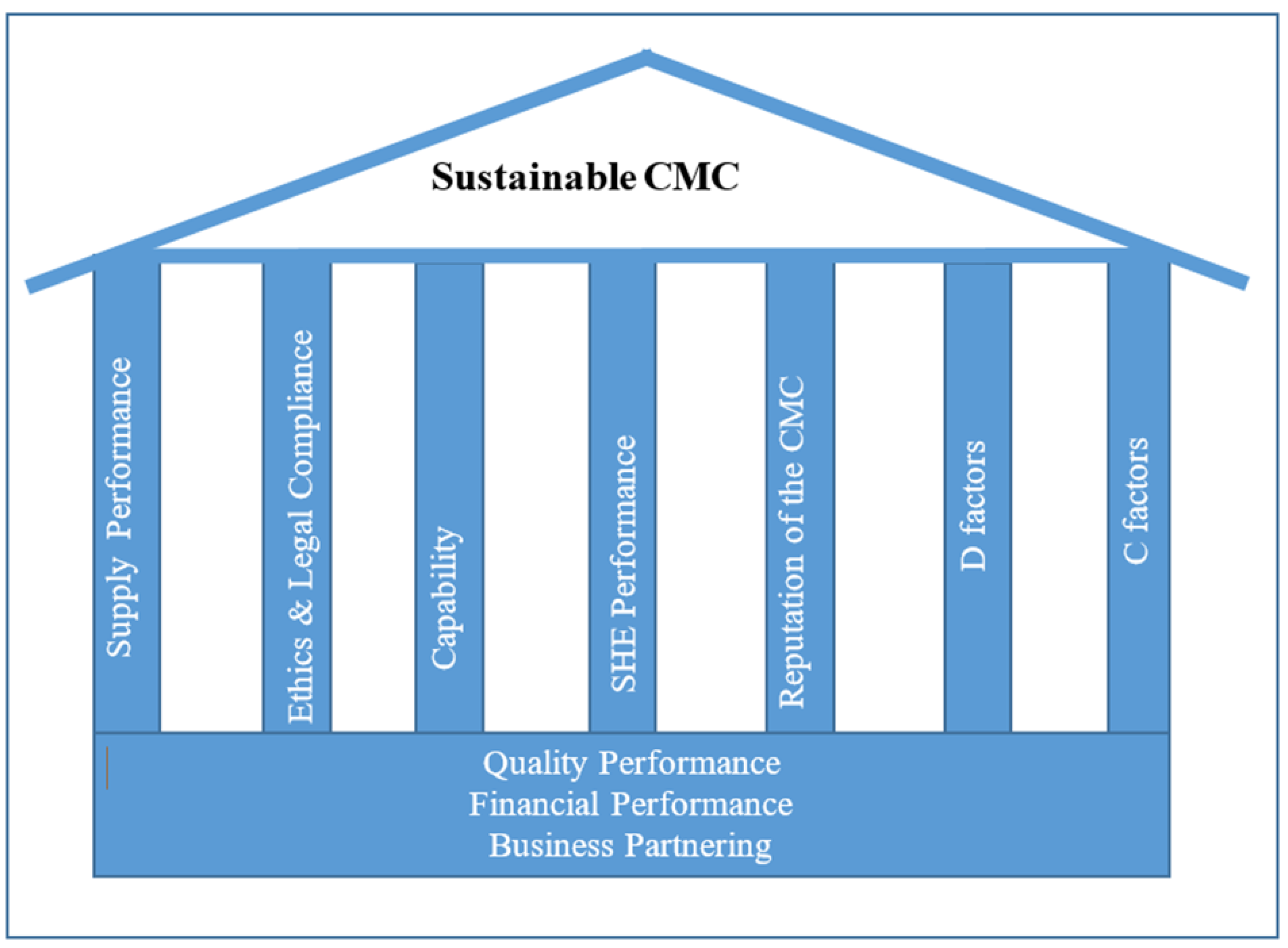

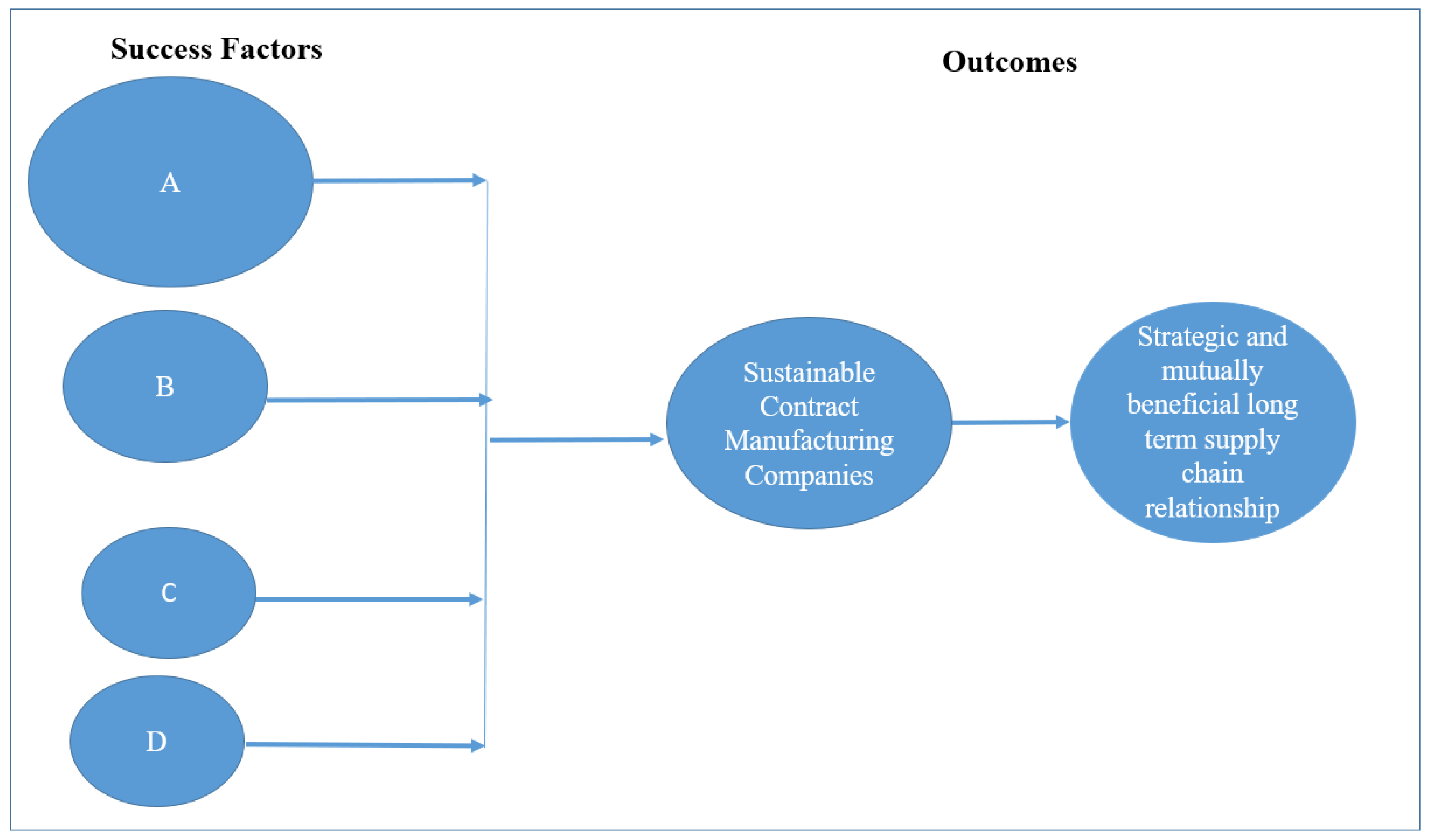

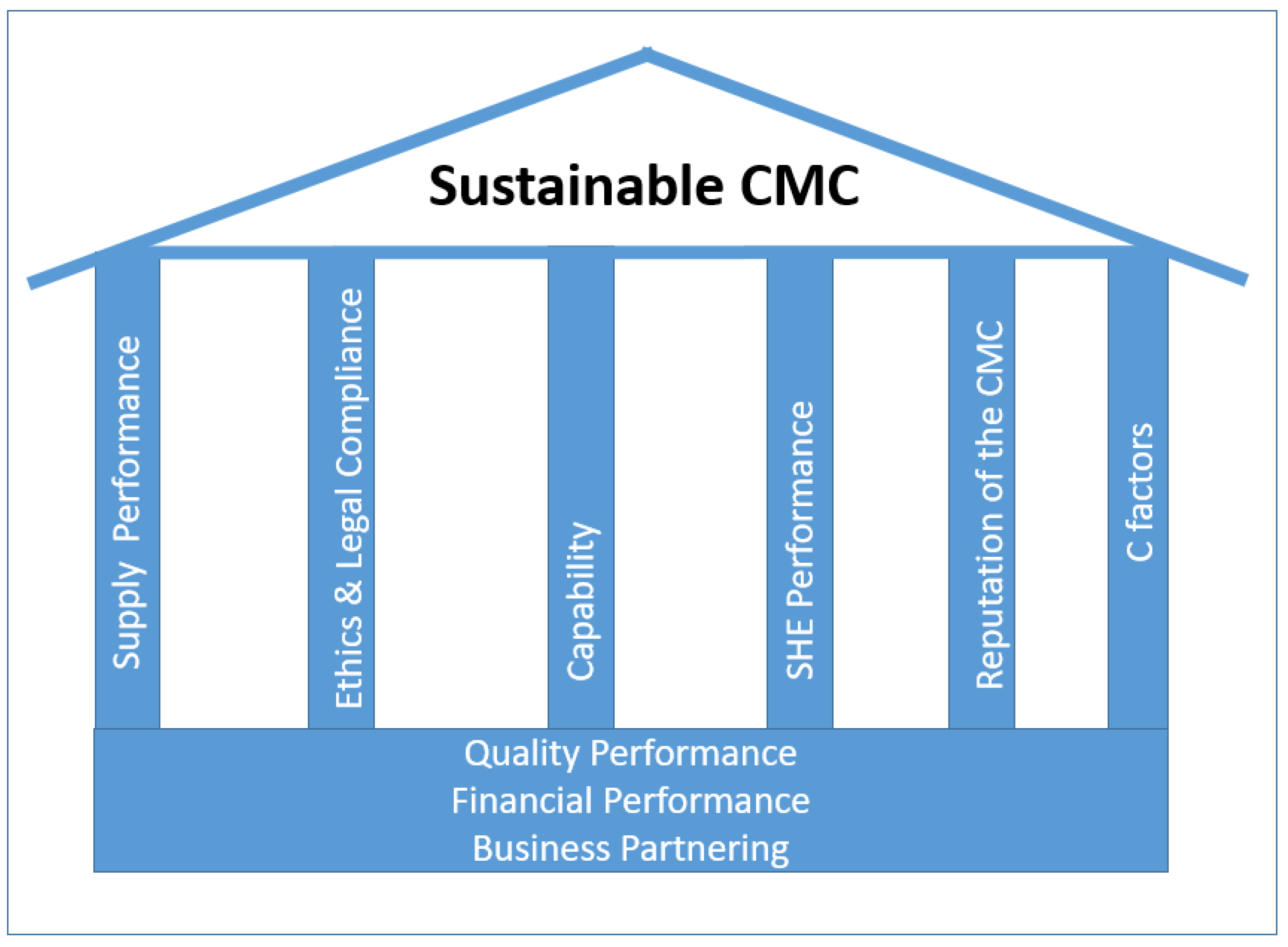

3. Overview of the SCMC-MM

- Quality Performance

- Supply Performance

- Financial Performance

- Operational Capability

- Business Partnering

- SHE Performance

- Reputation

- Ethical and Legal Compliance

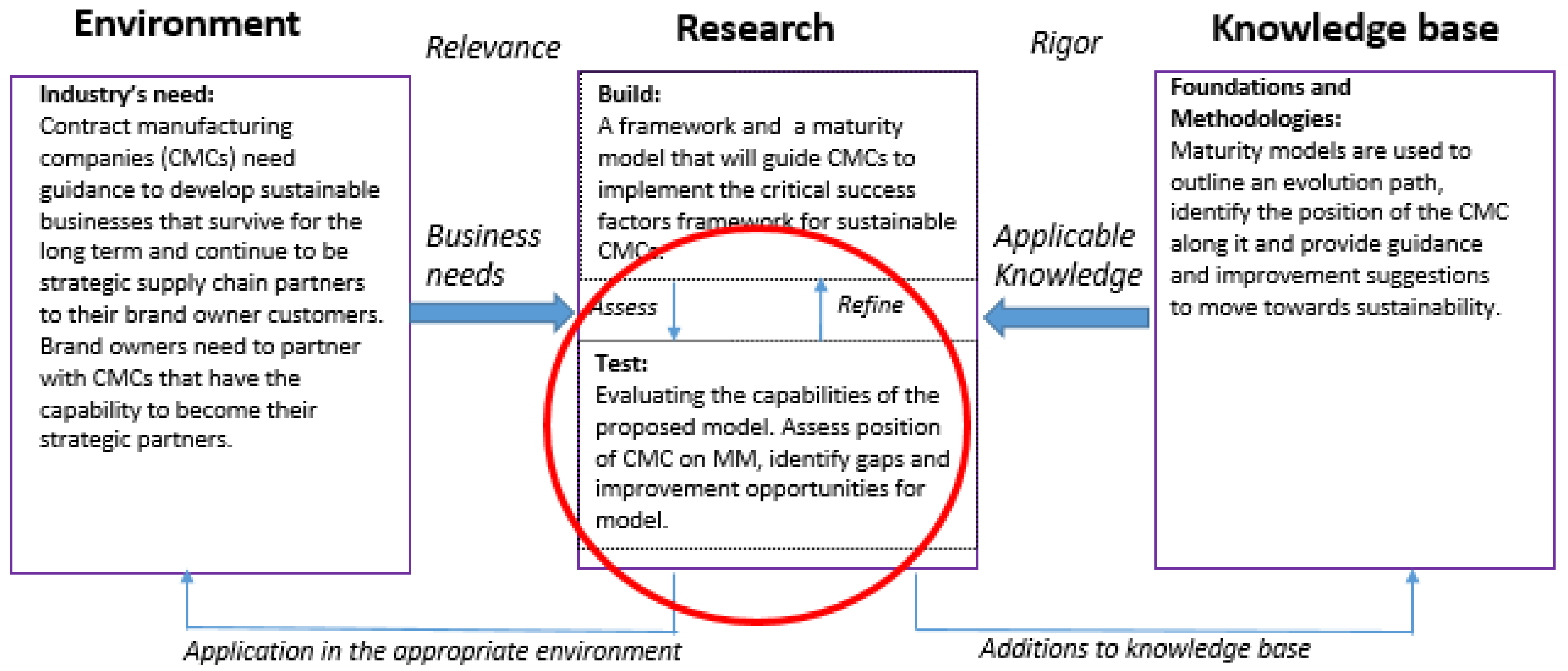

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Approach

4.2. Case Study Design

4.3. Data Collection Methods

- Structured sustainability assessments using the SCMC-MM checklist [6].

- Daily and weekly observations on the factory floor.

- Semi-structured interviews with team leaders, supervisors, and management.

- Review of company documentation (quality reports, supplier logs, production data).

- Performance tracking via radar charts and operational metrics.

4.4. Evaluation and Refinement Process

5. Case Study Application

5.1. Selected Company

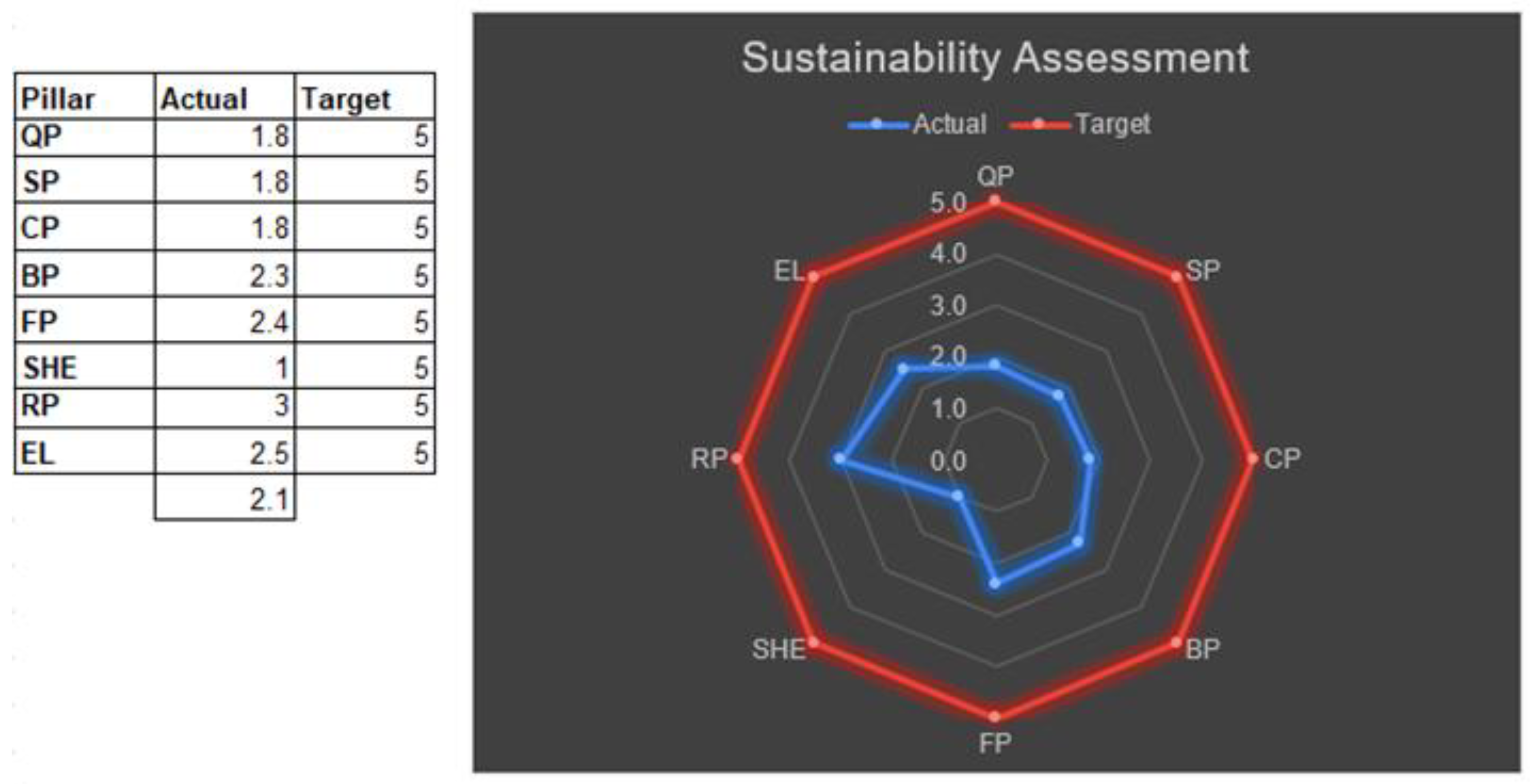

5.2. Initial Assessment

- The CMC’s overall assessed core was 2.1, meaning they were at sustainability level 2, Foundation building.

- Four pillars were below level 2 of the transformation level. These are SHE, Quality Performance, Supply Performance and Capability.

- SHE, with a score of 1, had the lowest score driven by the absence of systems to manage occupational safety and health as well as by a complete lack of focus on environmental compliance and resource efficiency, such as waste management, energy consumption monitoring, or water usage policies..

- The Quality Performance score of 1.8 was impacted largely by poor housekeeping, an ineffective and incomplete quality management system, plant layout that was not conducive to quality and food safety compliance, low level of quality and food safety skills and the lack of compliance to good manufacturing practices (GMP).

- Supply performance also scored 1.8 and this was impacted by a record of late deliveries, not having a supply and operations management system in place to track and manage supply performance and not having a continuous improvement structure.

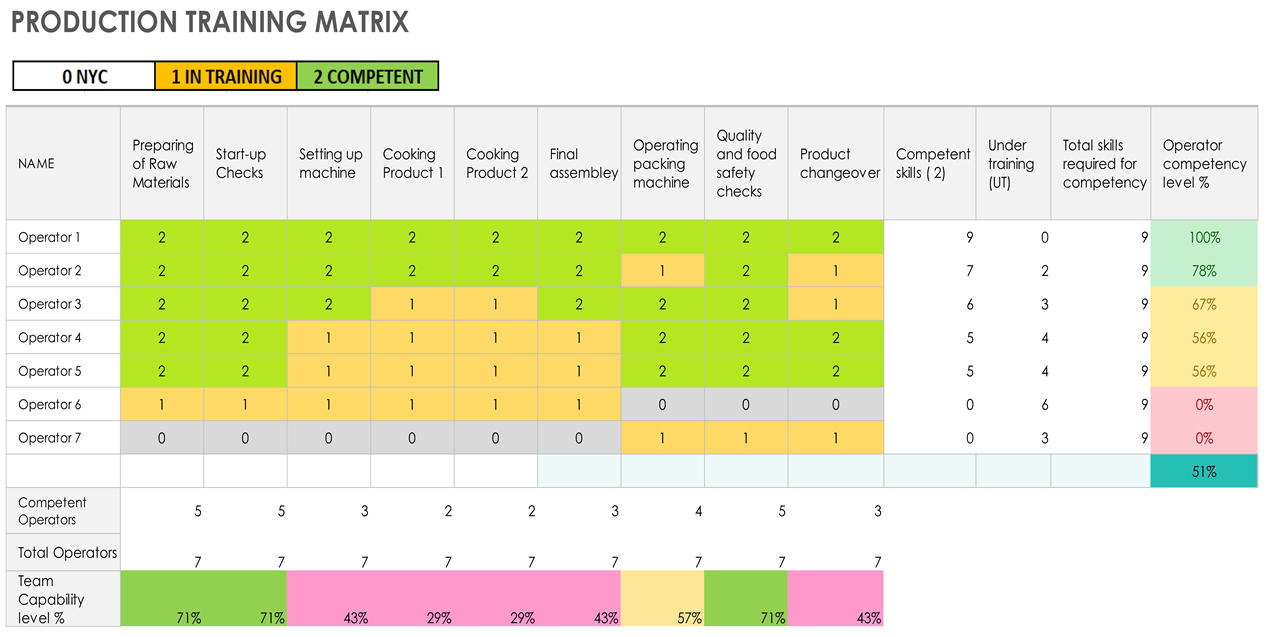

- Capability scored 1.8. The experience levels of management and key roles in Quality and Production scored 3. The lower scores were the absence of a plant performance monitoring system, no documented maintenance management system, poor skills at operational level and limited problem solving skills.

- Three pillars, Ethics and Legal Compliance, Financial Performance and Business Partnering were at level 2.

- Ethics and Legal Compliance scored 2.5. There is no documented ethics management system or policy, which scored 1. However, they have no record of legal or ethics noncompliance, which gave a score of 4.

- Financial performance scored 2.2, mainly impacted by the fact that there was no cost saving program in place, there was no annual budget drawn up and the CMC struggled with cashflow challenges.

- Business Partnering scored 2.3. The CMC has good relations with customers and key suppliers. They, however, did not have service level agreements (SLAs) in place and no performance monitoring and reviews systems in place. There are also no joint problem solving processes implemented and no evidence of technology transfers and technical support from brand owners.

- Reputation was on level 3, the highest score. They have had major quality incidents leading to product recalls, which has impacted on their reputation. They do have a good reputation for supplying good tasting food, maintaining confidentiality, communicating regularly with key customers and suppliers, and donating food for charity purposes.

5.3. Recommendations for Improvement of Level

5.4. Key Actions Taken from Recommendations

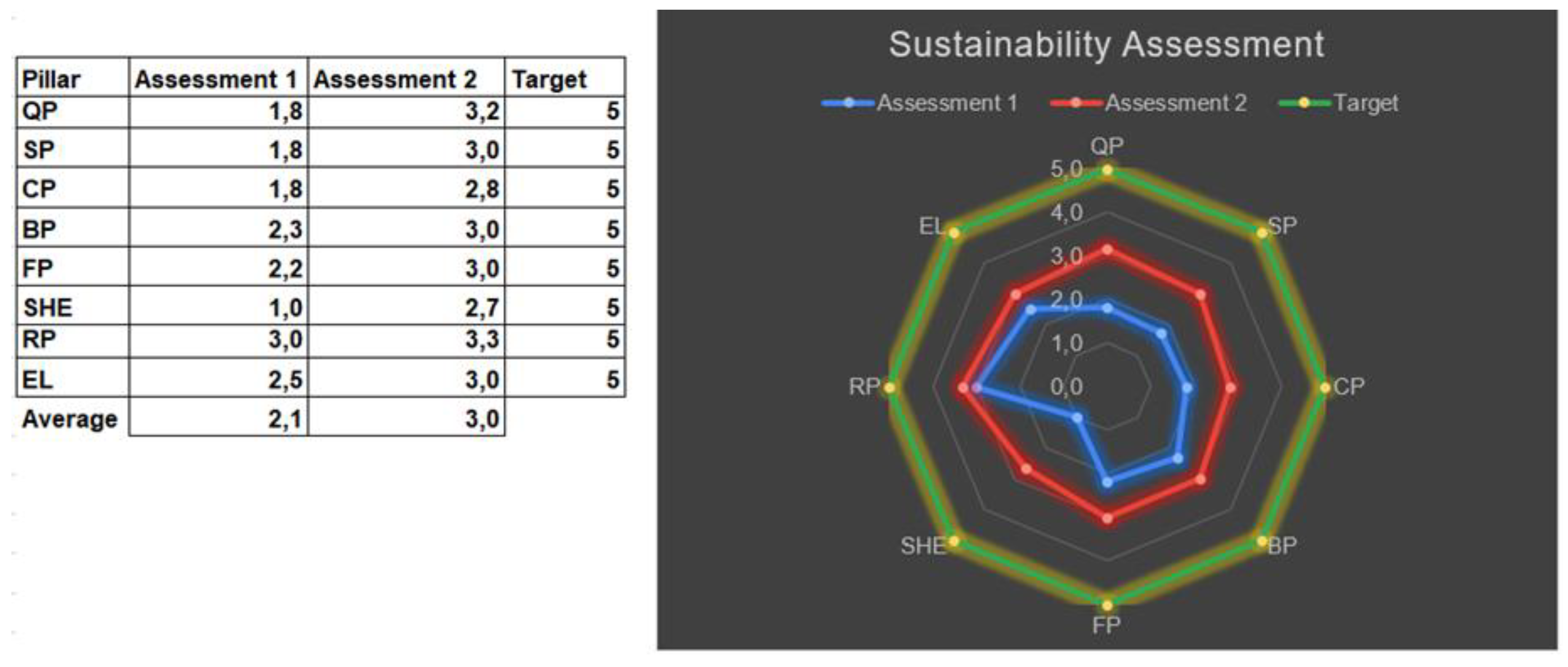

5.5. Second Assessment

- The CMC transformed to sustainability level 3.

- The biggest improvements were noted in the pillars of Quality performance, Supply performance, Financial performance, SHE and Business partnering.

- While the CMC had lost a big contract from a leading brand owner they were able to bring on board three national brand owners as customers primarily because of their capability, quality and food safety management system and pricing.

- They have developed a SHE management system that is documented and visible, with tracking of incidents in place.

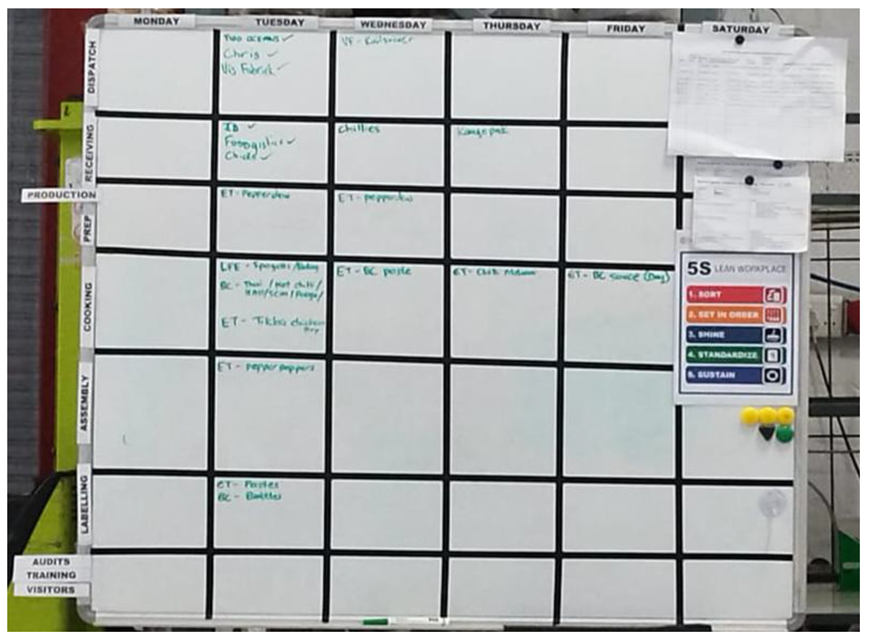

- They improved supply performance through the development of an operations and supply management system based on integrated supply scheduling. This made it easier for them to commit to supply only when it was possible to do so.

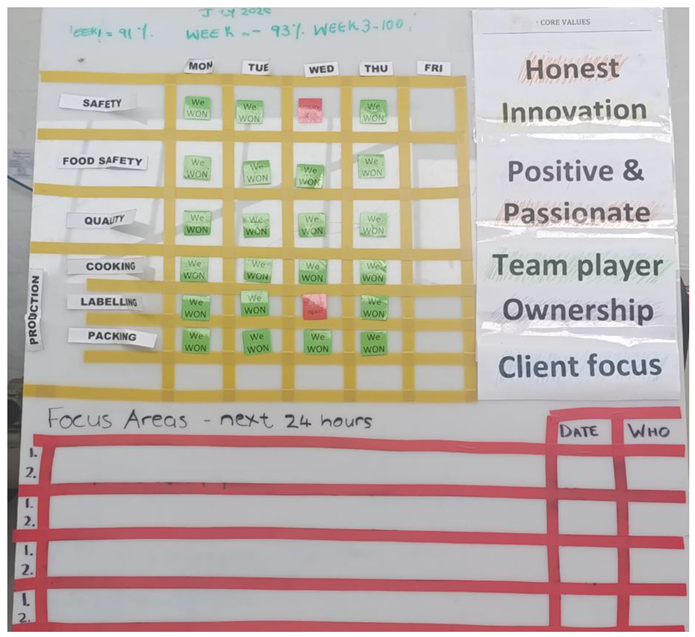

- The culture at the factory has shifted from one of disgruntlement and unhappiness to one of positivity and willingness to contribute, even when they had to work fewer hours after losing a key contract.

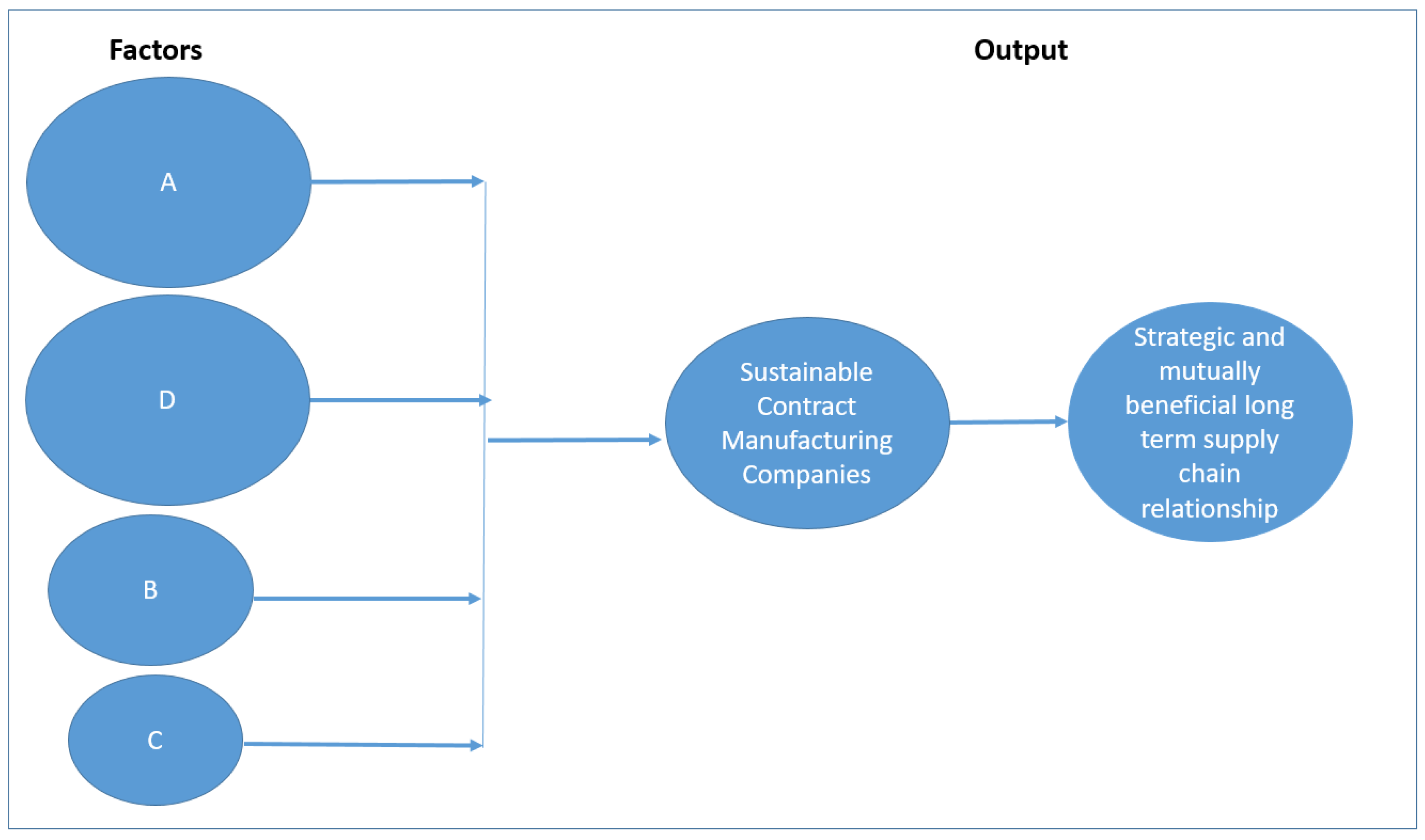

5.6. Additional (D) factors emerging from the demonstrations

- Business development and marketing of capacity and capabilities so that the loss of one customer or product line does not result in business closure.

- Manufacturing own brands to utilize the capacity and not rely on brand owners only. This is most applicable where the CMC has a narrow customer base and excess capacity.

- Business partnering must be actively practiced not only with the brand owners but suppliers, service providers, regulatory authorities and other key stakeholders, including landlords.

- The CMC collaborated with two other manufacturing companies, who are potentially competitors, capable of making similar products to define a working structure to approach big brand owners for big orders of common products. This is also called industrial clustering. Industrial clusters refer to groups of interconnected businesses and institutions that collaborate to enhance competitiveness and efficiency [46]. These clusters facilitate resource-sharing, innovation, and cost reductions, particularly benefiting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with limited resources.

- Extending the industrial cluster approach to reduce costs by sharing service providers, resources, equipment and professional services with companies making similar products or in the same geographical area. The CMC shared maintenance and transport service providers with other businesses in the same area to assess professional services at affordable costs.

- Daily scheduling and monitoring of all tasks on a weekly basis in an integrated schedule was critical for monitoring and controlling deliveries and improving supply performance.

- CMCs must boldly take their position as partners in the supply chain and have the courage to stand up to brand owners and walk away from business that is not working for them or not sustainable. The CMC informed a brand owner they could not continue supplying a product line which was no longer profitable to them and was costing them money to supply. The brand owner eventually agreed to the CMC’s proposed price.

- First impressions matter to visitors and potential customers. The appearance of the facility, the welcome they get, the induction given to them, the practices they observe, and the information displayed on boards had an impact on securing business.

- The CMCs must create an organisational culture of ownership, where they focus all their employees on continuously finding ways to improve their productivity and to cut costs. This must be one of their key leadership competencies.

- CMCs must focus everyone in the company and key stakeholders on continuously keeping the customer satisfied and identifying opportunities to reduce costs.

- Leadership style is critical. In the CMC at the start of the assessment the leadership style being displayed was more autocratic, it was only the leader’s voice that was heard. Production delays due to the team waiting for direction from the leader or waiting for the leader to buy materials were common. A culture of fear was evident. This was different during the second assessment where the culture was more open, with people freely making suggestions to management. This resonated well with the findings of [47] in their study on transformational leadership for SMEs, which described transformational leaders as leadership that prioritises open communication, empathy, and support, creating an environment where employees feel valued and empowered to contribute their best efforts. It is characterized by the ability to articulate a compelling vision, inspire trust and encourage employees to exceed their usual performance levels, fostering a culture of problem solving and continuous improvement [47,48,49,50]. We therefore recommend that to achieve sustainable success the leaders of CMCs must be adopt a transformational leadership style. This is included as a critical success factor.

5.7. Proposed Final CMC Framework

6. Summary

6.1. System-Level Improvements

6.2. Operational and Strategic Outcomes

6.3. Framework Refinement and New Success Factors

6.4. Practical Applicability and Scalability

6.5. Theoretical and Practitioner Contributions

- Managers of CMCs to assess their current sustainability level, identify improvement opportunities from the pillars and factors that are at lower levels and determine actions for improvement and moving up the levels towards level 5.

- Brand owners as part of selecting the best CMC as their supply partner. They can use the assessment sheet to compare potential partners and select the one with the factors critical to the brand owners and on a higher level on the sustainability level.

- Brand owners as part of supporting their existing CMC partner to improve their supply performance and sustainability.

- Consultants assisting CMCs to improve their systems and practices towards sustainability. The assessment checklist will identify current gaps and opportunities for improvement and will enable the generation and implementation of improvement plans

6.6. Implications for Sustainability

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Authors:

Appendix A1 – Housekeeping and GMP Violations BEFORE

Appendix A2: Housekeeping and GMP Compliance AFTER

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Deng, S.; Xu, J. Manufacturing and procurement outsourcing strategies of competing original equipment manufacturers. Eur J Oper Res. 2022, 308, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Phan, T. Optimal manufacturing outsourcing decision based on the degree of manufacturing process standardization. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications (ICIEA); 2018. p. 49–53.

- Shanmugan, M.; Shaharudin, M.S.; Ganesan, Y.; Fernando, Y. Manufacturing outsourcing to achieve organizational performance through manufacturing integrity capabilities. In: FGIC 2nd Conference on Governance and Integrity; 2019. KnE Soc Sci. p. 858–871.

- Mahove, T.T.; Matope, S. A critical success factors framework for sustainable contract manufacturing in the consumer products supply chain in South Africa: A review. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management; 2021 Aug 2–5; Rome, Italy. p. 206–1217.

- Mahove, T.T.; Matope, S. Experts’ consensus on critical success factors contract manufacturing. In: Proceedings of the 5th African International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management; 2024 Apr 23–25; Johannesburg, South Africa. p. 1164–1176.

- Mahove, T.T.; Matope, S. Development of a conceptual framework and management guide for sustainable contract manufacturing companies in South Africa. S Afr J Ind Eng. 2025; [manuscript under review]. [Google Scholar]

- Plambeck, E.L.; Taylor, T.A. Sell the plant? The impact of contract manufacturing on innovation, capacity, and profitability. Manag Sci. 2005, 51, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, H. The more the better? Optimal degree of supply-chain cooperation between competitors. J Oper Res Soc. 2015, 66, 2092–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, H. Manufacturing operations outsourcing through an artificial team process algorithm. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2016, 31, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgun, C. Restless contracts [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://curgun.scholar.princeton.edu.

- Szalkai, Z.; Magyar, M. Strategy from the perspective of contract manufacturers. IMP J. 2017, 11, 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, B.; Singh, A. Contract manufacturing: the boon for developing economies. Int J Innov Technol Explor Eng. 2019, 8, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrunada, B.; Vázquez, X.H. When your contract manufacturer becomes your competitor. Health Aff. 2006, 84, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu, S.G. Private label brands vs national brands: new battle fronts and future competition. Cogent Bus Manag. 2024, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.M.; Veiga, F.C.; Pinto, A.S. Should private-label supply manufacturers invest in digital strategies? A study on Portuguese manufacturers. J Strateg Mark. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Yang, W.; Wu, J. Private label management: a literature review. J Bus Res. 2021, 125, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D.; Nguyen, D. No plant, no problem? Factoryless manufacturing, economic measurement and national manufacturing policies. Rev Int Polit Econ. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M. Factoryless goods producers in Japan. Jpn World Econ. 2016, 40, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y. Factoryless manufacturers and international trade in the age of global value chains. RePEc Working Paper. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Goriwondo, W.M.; Madzivire, A.B. Framework towards successful implementation of world class manufacturing principles: a multiple case study of the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) in Zimbabwe. Zimb J Sci Technol. 2015, 10, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Kodali, R. Development of a framework for manufacturing excellence. Meas Bus Excell. 2008, 12, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, L.E. The 12 Principles of Manufacturing Excellence: A Leader’s Guide to Achieving and Sustaining Excellence. Hoboken (NJ): CRC Press;

- Paranitharan, K.P.; Thangevelu, R.B. An integrated model for achieving sustainability in the manufacturing industry – an empirical study. Int J Bus Excell. 2019, 16, 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusev, S.J.; Salonitis, K. Operational Excellence Assessment Framework for Manufacturing Companies. Procedia CIRP. 2016, 55, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.; Luthra, S.; Huisingh, D.; Mangla, S.K.; Narkhede, B.E.; Liu, Y. Development of a lean manufacturing framework to enhance its adoption within manufacturing companies in developing economies. J Clean Prod. 2020, 245, 118726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.N.; Ganguly, S.K. Critical success factors for manufacturing industries in India: A case study analysis. Int J Appl Eng Res. 2019, 18, 1898–1905. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.S.; Chang, T.C.; Lin, Y.T. Developing an outsourcing partner selection model for process with two-sided specification using capability index and manufacturing time performance index. Int J Reliab Qual Saf Eng. 2019, 26, 1950015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfving, M.; Säfsten, K.; Winroth, M. Manufacturing strategy frameworks suitable for SMEs. J Manuf Technol Manag. 2014, 25, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.C. Evaluating the role and integration of contract manufacturing strategy in supply chain management: an empirical study. Int J Manuf Technol Manag. 2010, 19, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandják, T.; Szalkai, Z.; Hlédik, E.; Neumann-Bódi, E.; Magyar, M.; Simon, J. The knowledge interconnection process: evidence from contract manufacturing relationships. J Bus Ind Mark. 2021, 36, 1570–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, A.A.; Gray, J.V.; Noh, I.J.; Mahoney, J.T. A review of production and operations management research on outsourcing in supply chains: implications for the theory of the firm. Prod Oper Manag. 2018, 27, 1177–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, E.; Proença, J.F.; Proença, T.; de Castro, L.M. The supplier’s side of outsourcing: taking over activities and blurring organizational boundaries. Ind Mark Manag. 2014, 43, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, D.; Jenster, P. Outsourcing: the supplier viewpoint. Strateg Change. 2003, 12, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.C.; Martinho, J.L. An Industry 4.0 maturity model proposal. J Manuf Technol Manag. 2019, 31, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansali, O.; Elrhanimi, S.; El Abbadi, L. Supply chain maturity models - a comparative review. LogForum. 2022, 18, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahove, T.T.; Matope, S. An empirical study to identify the critical success factors for sustainable contract manufacturing in the consumer products supply chain in South Africa. S Afr J Ind Eng. 2024, 35, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peffers, K.; Tuunanen, T.; Rothenberger, M.A.; Chatterjee, S. A design science research methodology for information systems research. J Manag Inf Syst. 2007, 24, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A.R.; Chatterjee, S. Design research in information systems: theory and practice. New York (NY): Springer;

- Coetzee, R. Towards designing an artefact evaluation strategy for human factors engineering: a lean implementation model case study. S Afr J Ind Eng. 2019, 30, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herselman, M.; Botha, A. Applying design science research as a methodology in postgraduate studies: a South African perspective. In: Proceedings of the Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists. (SAICSIT ’20); 2020 Sep 14–16; Cape Town, South Africa. p. 251–258, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mdletshe, S.; Motshweneng, O.S.; Oliveira, M.; Twala, B. Design science research application in medical radiation science education: A case study on the evaluation of a developed artifact. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2023, 54, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venable, J.; Pries-Heje, J.; Baskerville, R. FEDS: A Framework for Evaluation in Design Science Research. Eur J Inf Syst. 2016, 25, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.; De Oliveira, E.; Carraro, C.; Entelman, F. FSSC 22000 certification: study of implementation in a Brazilian agroindustrial cooperative located in the Southwest region of the State of Sao Paulo. IOSR J Bus Manag. 2022, 22, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Tineo, R.; Rodríguez-León, A.; Solano-Gaviño, J.C. FSSC 22000 scheme as an effective strategy for producing safe and quality food. Agroind Sci. 2024, 14, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamula, V.S.; Kuzlyakina, Y.A. Features of the FSSC 22000 certification scheme when implemented in the meat industry. Meat Ind J. 2021, 1, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Clusters and the New Economics of Competition. Harv Bus Rev. 1998, 76, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdul-Azeez, O.; Ihechere, A.O.; Idemudia, C. Transformational leadership in SMEs: Driving innovation, employee engagement, and business success. World J Adv Res Rev. 2024, 22, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burawat, P. The relationships among transformational leadership, sustainable leadership, lean manufacturing and sustainability performance in Thai SMEs manufacturing industry. Int J Qual Reliab Manag. 2019, 36, 1014–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.S.; Kee, D.M.H. The core competence of successful owner-managed SMEs. Manag Decis. 2018, 56, 252–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, H.M.; Srivastava, A.K. CEO Transformational Leadership, Supply Chain Agility and Firm Performance: A TISM Modeling among SMEs. Glob J Flex Syst Manag. 2022, 24, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Level descriptor | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Starting out | No or very few success factors are in place, no implementation plans. |

| 2 | Foundation building | Some success factors under implementation or in place. Performance on key KPIs below target. |

| 3 | On solid ground | Majority success factors are in place. Performances on some but not all key KPIs on target. |

| 4 | Towards sustainability | Majority success factors are in place. Performances on all key KPIs on target. |

| 5 | Sustainable CMC | All success factors are in place. Performance on key KPIs is on target and improvements are demonstrated. |

| Pillar | Observed gaps | Recommendations for transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Performance |

|

|

| Financial Performance |

|

|

| Capability |

|

|

| Business Partnering |

|

|

| Supply Performance |

|

|

| Reputation |

|

|

| SHE Performance |

|

|

| Ethics and Legal Compliance |

|

|

| Actions taken | Observed results |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| D Factor | Pillar |

|---|---|

| Improve Product and/ or customer base diversification | Capability |

| Partner with businesses in strategic industrial clusters | Business Partnering |

| Sit on the table with brand owners as equal supply chain partners | Business Partnering |

| Keep inventory costs to a bare minimum without disrupting production. | Financial Performance |

| Engage regulators for their support | Business Partnering |

| Focus everyone in the team on customer satisfaction and cost saving | Capability |

| Design and implement integrated scheduling and manage it through management and team routines | Capability |

| Transformational leadership | Capability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).