Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Protocol

2.3. CHAMPS Measures

2.4. Statistical Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Multivariate & Univariate Logistic Regressions

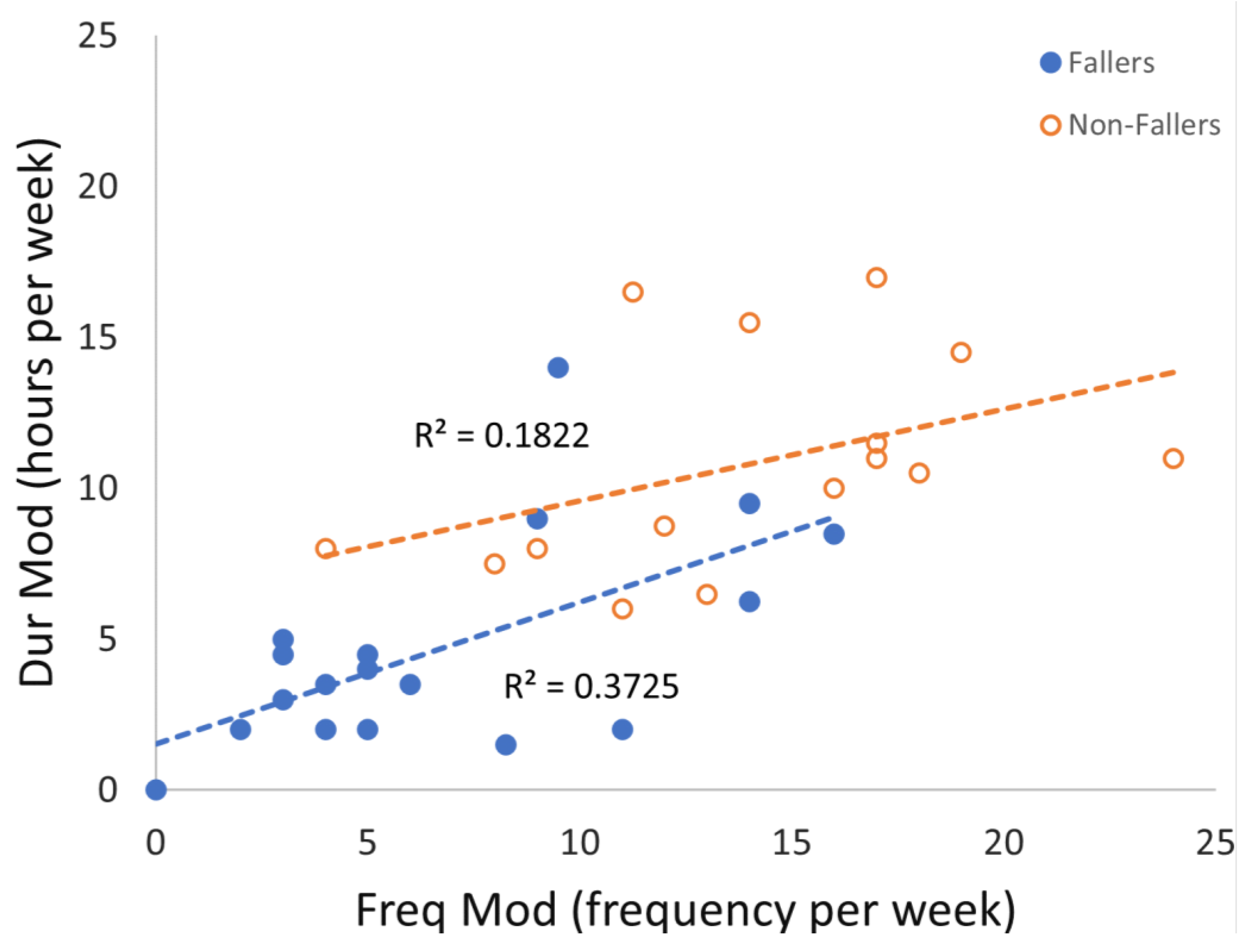

3.2. Correlations Between Frequency and Duration of Moderate and Greater Physical Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACSM | American College of Sports Medicine |

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| BW | Body Weight |

| CHAMP | Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors |

| Dur | Duration |

| Dur Low | Duration Low |

| Dur Mod | Duration Moderate/High |

| Freq | Frequency |

| Freq Low | Frequency Low |

| Freq Mod | Frequency Moderate/High |

| Kcal | Estimated Caloric Expenditure |

| Kcal Low | Estimated Caloric Expenditure of Low |

| Kcal Mod | Estimated Caloric Expenditure of Moderate/High |

| MET | Metabolic Equivalent |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental Status Examination |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| U.S. | United States |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

References

- Roudsari BS, Ebel BE, Corso PS, Molinari NAM, Koepsell TD. The acute medical care costs of fall-related injuries among the U.S. older adults. Injury. 2005, 36, 1316–22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stel VS, Smit JH, Pluijm SMF, Lips P. Consequences of falling in older men and women and risk factors for health service use and functional decline. Age Ageing. 2004, 33, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Seniors’ Falls in Canada. Ottawa, ON: CA 2014.

- Elam C, Aagaard P, Slinde F, Svantesson U, Hulthén L, Magnusson PS, et al. The effects of ageing on functional capacity and stretch-shortening cycle muscle power. J Phys Ther Sci. 2021, 33, 250–60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira A, Nossa P, Mota-Pinto A. Assessing functional capacity and factors determining functional decline in the elderly: A cross-sectional study. Revista Científica da Ordem dos Médicos [revista en Internet] 2019 [acceso 2 de febrero de 2021]; 32, 654-660. [Internet]. 2019; Available from: https://www.actamedicaportuguesa.com/revista/index.php/amp/article/view/11974/5773.

- Wickramarachchi B, Torabi MR, Perera B. Effects of Physical Activity on Physical Fitness and Functional Ability in Older Adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2023;9.

- Boss GR, Seegmiller JE. Age-related physiological changes and their clinical significance. West J Med. 1981, 135, 434–40.

- Warburton, D. E.R. Nicol, C W BSS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence [Internet]. Can Med Assoc J [Internet]. 2006 Mar 14;174, 801–9. Available from: http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/doi/10.1503/cmaj.051351.

- Bindawas SM, Vennu V. Longitudinal effects of physical inactivity and obesity on gait speed in older adults with frequent knee pain: Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015, 12, 1849–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrington C, Michaleff ZA, Fairhall N, Paul SS, Tiedemann A, Whitney J, et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017, 51, 1749–57.

- Paterson DH, Warburton DER. Physical activity and functional limitations in older adults: A systematic review related to Canada’s Physical Activity Guidelines. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7.

- Rubenstein, LZ. Falls in older people: Epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing. 2006, 35(SUPPL.2):37–41.

- Arnold CM, Sran MM, Harrison EL. Exercise for Fall Risk Reduction in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Physiother Canada. 2008, 60, 358–72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang DXM, Yao J, Zirek Y, Reijnierse EM, Maier AB. Muscle mass, strength, and physical performance predicting activities of daily living: a meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020, 11, 3–25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carande-Kulis V, Stevens JA, Florence CS, Beattie BL, Arias I. A cost-benefit analysis of three older adult fall prevention interventions [Internet]. J Safety Res [Internet]. Elsevier B.V.; 2015;52:65–70. [CrossRef]

- Robertson MC, Campbell AJ, Gardner MM, Devlin N. Preventing injuries in older people by preventing falls: A meta-analysis of individual-level data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002, 50, 905–11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrington C, Fairhall N, Kwok W, Wallbank G, Tiedemann A, Michaleff ZA, et al. Evidence on physical activity and falls prevention for people aged 65+ years: systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour [Internet]. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act [Internet]. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity; 2020 Dec 26;17, 144. Available from: https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-020-01041-3.

- Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson L, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community [Internet]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2012 Sep 12;2021(6). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD007146.

- Sun M, Min L, Xu N, Huang L, Li X. The effect of exercise intervention on reducing the fall risk in older adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(23).

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 SUPPL.).

- Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: Outcomes for interventions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1126–41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushman BA. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans [Internet]. ACSMs Health Fit J [Internet]. 2019 May;23, 5–9. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00135124-201905000-00004.

- Cao J, Zhang S. Multiple comparison procedures. Jama. 2014, 312, 543–4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis E, Straker L, Hamer M, Gebel K. The 2018 physical activity guidelines for Americans: What’s new? Implications for clinicians and the public. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019, 49, 487–90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines [Internet]. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 2022 [cited 2023 Nov 20] p. 1–2. Available from: https://csepguidelines.ca/guidelines/adults-65/.

- 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical activity guidelines advisory committee scientific report. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC.

- Yang, YJ. An Overview of Current Physical Activity Recommendations in Primary Care. Korean J Fam Med. 2019, 40, 135–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour [Internet]. Geneva. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128.

- Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans [Internet]. JAMA [Internet]. 2018 Nov 20;320, 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30418471.

- Scherr J, Wolfarth B, Christle JW, Pressler A, Wagenpfeil S, Halle M. Associations between Borg’s rating of perceived exertion and physiological measures of exercise intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013, 113, 147–55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerterp, KR. Assessment of physical activity: A critical appraisal. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009, 105, 823–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahabir S, Baer DJ, Giffen C, Clevidence BA, Campbell WS, Taylor PR, et al. Comparison of energy expenditure estimates from 4 physical activity questionnaires with doubly labeled water estimates in postmenopausal women [Internet]. Am J Clin Nutr [Internet]. American Society for Nutrition.; 2006;84, 230–6. [CrossRef]

- Melanson EL, Freedson PS, Blair S. Physical Activity Assessment: A Review of Methods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1996, 36, 385–96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschuler A, Picchi T, Nelson M, Rogers JD, Hart J, Sternfeld B. Physical activity questionnaire comprehension: Lessons from cognitive interviews. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 336–43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Fallers | Non-fallers | Sig |

| (n = 18) | (n = 15) | (p) | |

| Age (years) | 75.9 (3.3) | 75.1 (3.5) | 0.632 |

| Height (cm) | 166.6 (8.8) | 169.5 (8.5) | 0.840 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.4 (18.0) | 77.5 (11.7) | 0.101 |

| MMSE | 28.8 (1.1) | 28.5 (1.3) | 0.244 |

| Variable | Fallers | Non-fallers | Sig |

| (N = 18) | (N = 15) | (p) | |

| Dur Low | 7.6 (5.0) | 6.7 (3.2) | 0.745 |

| Dur Mod | 5.0 (4.3) | 10.8 (3.6) | <0.001* |

| Freq Low | 11.1 (6.6) | 13.3 (6.9) | 0.269 |

| Freq Mod | 7.3 (5.4) | 14.0 (5.0) | 0.002* |

| Kcal Low | 1266.8 (599) | 1296.4 (722) | 1.000 |

| Kcal Mod | 1463 (1289) | 3624.2 (1470) | <0.001* |

| Model | Variables | B | SE | Wald | df | Sig | Exp(B) | 95% CI | |

| 95. | Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Dur | Dur Mod | -0.366 | 0.131 | 7.799 | 1 | 0.005* | 0.693 | 0.536 | 0.897 |

| Dur Low | 0.046 | 0.131 | 0.123 | 1 | 0.725 | 1.047 | 0.810 | 1.353 | |

| Constant | 2.620 | 1.389 | 3.555 | 1 | 0.059 | 13.730 | |||

| Freq | Freq Mod | -0.247 | 0.088 | 7.889 | 1 | 0.005* | 0.781 | 0.657 | 0.928 |

| Freq Low | -0.083 | 0.068 | 1.481 | 1 | 0.224 | 0.921 | 0.806 | 1.052 | |

| Constant | 3.790 | 1.470 | 6.650 | 1 | 0.010 | 44.272 | |||

| Kcal | Kcal Mod | -0.001 | 0.000 | 8.614 | 1 | 0.003* | 0.999 | 0.998 | 1.000 |

| Kcal Low | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.202 | 1 | 0.653 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.002 | |

| Constant | 2.420 | 1.208 | 4.011 | 1 | 0.045 | 11.250 | |||

| Model | B | SE | Wald | df | Sig | Exp(B) | 95% CI | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Dur Low | 0.056 | 0.092 | 0.378 | 1 | 0.539 | 1.058 | 0.884 | 1.266 |

| Dur Mod | -0.366 | 0.130 | 7.956 | 1 | 0.005* | 0.693 | 0.537 | 0.894 |

| Freq Low | -0.052 | 0.055 | 0.899 | 1 | 0.343 | 0.950 | 0.853 | 1.057 |

| Freq Mod | -0.231 | 0.082 | 7.882 | 1 | 0.005* | 0.794 | 0.676 | 0.933 |

| Kcal Low | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.966 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.001 |

| Kcal Mod | -0.001 | 0.000 | 8.977 | 1 | 0.003* | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).