Introduction

A major challenge in origins-of-life research is explaining how primitive compartments could support the molecular traffic needed for growth and replication (Budin & Szostak, 2010; Chen & Szostak, 2004). Fatty-acid vesicles, commonly seen as plausible protocell membranes, form easily in water, yet they are well known for being nearly impermeable to nucleotides, peptides, and divalent ions (Deamer, 1985; Adamala & Szostak, 2013). Without a mechanism for exchange, such vesicles risk becoming chemically isolated; they protect fragile replicators but, at the same time, deprive them of the necessary substrates.

Several workarounds have been proposed, including transient permeability changes during pH or temperature cycling, or confinement within mineral pores; however, each faces limitations. Fluctuations are often too brief or non-specific (Monnard & Deamer, 2002), while mineral compartments lack bilayer membranes altogether (Russell & Martin, 2004). This leaves a critical gap; how could vesicles themselves acquire the ability to exchange solutes in a sustained, chemically plausible manner?

One underexplored possibility is that short abiotically produced peptides acted as primitive leakage agents. Modern biology demonstrates that antimicrobial peptides destabilize bilayers and, in some cases, assemble into transient channels (Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Bechinger, 1997; Wimley, 2010). Even trace amounts of analogous peptides on the early Earth could have significantly increased vesicle permeability. Laboratory syntheses, meteoritic analyses, and stochastic simulations consistently show that short peptides were accessible prebiotically, enriched in glycine, alanine, and valine (Shimoyama et al., 1979; Burton et al., 2012; Huber & Wächtershäuser, 1998; Forsythe et al., 2015). This biased inventory disfavors stable α-helices but strongly promotes β-sheet and turn structures, which in modern systems are prone to amyloid-like aggregation and leaky pore formation (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011).

Taken together, the convergence of fatty-acid vesicles, glycine-rich peptide synthesis, and β-sheet aggregation suggests a coherent framework; β-structured oligomers represent the most chemically plausible candidates for introducing permeability into protocells. In this paper, the plausibility of such peptide-mediated leakage as an early solution to the transport problem is evaluated.

This manuscript is structured as a Hypothesis Article, rather than a review or report of new experimental data. Prior studies have highlighted the permeability challenge in fatty acid vesicles (Chen & Szostak, 2004; Adamala & Szostak, 2013) and evaluated transient mechanisms such as pH cycling, mineral pores, or α-helical peptide analogues (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Budin & Szostak, 2011; Blackmond, 2019). However, few works have systematically examined β-strand oligomers as prebiotic pore-formers. The novelty of this contribution lies in linking the biased amino acid inventories documented in meteorites and laboratory syntheses (rich in glycine, alanine, and valine) with the structural plausibility of β-strand aggregation and in supporting this connection through stochastic peptide simulations. In doing so, this work advances the idea that irregular β-sheet assemblies represent not only a chemically feasible outcome of prebiotic chemistry but also a functional bridge toward the first transport-competent protocells.

Early Earth Membrane Candidates

A fundamental prerequisite for the origin of life is the formation of compartments that could enclose and concentrate chemical reactions (Deamer, 1997; Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978). Several structural models have been proposed as plausible protocell membranes under prebiotic conditions, each with distinct strengths and limitations (Deamer & Pashley, 1989; Dworkin et al., 2001). The simplest assemblies are hydrophobic droplets of long-chain hydrocarbons. While such droplets spontaneously form spherical aggregates in aqueous environments, they lack true bilayer organization. Their boundaries consist only of hydrophobic cores with polar groups facing outward, providing little stability. Consequently, droplets readily coalesce and fail to support selective permeability. They are therefore considered poor candidates for functional protocell membranes (Deamer, 1997). Single-chain amphiphiles, such as short fatty acids, can self-assemble into micelles, small spherical aggregates stabilized by the packing of hydrophobic tails inward and polar heads outward. These structures display moderate stability only within narrow pH and ionic ranges (Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978). However, their small internal volume and monolayer boundaries limit their ability to encapsulate and sustain complex chemistries. Longer-chain fatty acids and related amphiphiles can form bilayer vesicles, encapsulating aqueous compartments in a manner analogous to modern cell membranes. These vesicles represent the most compelling model for early protocells, as they are relatively stable, capable of self-repair, and can undergo growth and division cycles (Budin & Szostak, 2011; Mansy & Szostak, 2008). Their bilayer structure provides the potential for regulated transport, making them prime candidates for investigating peptide-induced permeability.

Beyond lipid-based compartments, prebiotic environments likely produced coacervates; droplets formed through phase separation of charged polymers such as peptides, nucleic acids, or polysaccharides. Coacervates lack lipid bilayers and instead rely on semipermeable polymer-rich interfaces. Although they do not form true pores, peptides and other small molecules can partition at the phase boundary, altering permeability (Oparin, 1938; Keating, 2012). These structures demonstrate an alternative route to compartmentalization, albeit without bilayer-spanning pores.

Hydrothermal vent systems naturally produce porous mineral structures (e.g., FeS/FeS

2 chimneys). Such geological compartments can concentrate molecules and facilitate catalysis, but they do not provide lipid-like membranes. Instead, their rigid walls may have served as early scaffolds for chemical evolution, with peptides adsorbing to surfaces rather than inserting into bilayers (Russell & Martin, 2004). While valuable as geochemical reactors, mineral pores are not directly equivalent to biological membranes. These protocell models are compared in

Table 1.

Among these candidates, fatty acid vesicles (liposomes) stand out as the most plausible analogue to modern membranes, offering both compartmentalization and dynamic boundaries. While droplets, micelles, coacervates, and mineral pores illustrate alternative pathways to confinement, only bilayer vesicles provide the structural framework in which peptide-mediated pore formation becomes mechanistically relevant.

Peptides as Potential Pore-Formers in Early Earth Protocells

The plausibility of peptide-mediated pores depends first on whether short peptides could have existed in sufficient abundance on the prebiotic Earth. Multiple independent lines of evidence now confirm that simple peptides and peptide-like oligomers were indeed present, arising from both endogenous geochemical processes and extraterrestrial delivery.

Analyses of carbonaceous chondrites have revealed dipeptides and tripeptides, as well as amino acid derivatives capable of condensing into oligomers. Shimoyama et al. (1979) first reported glycylglycine in the Murchison meteorite, and later work extended these findings to other short glycine- and alanine-containing dipeptides (Martins et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2012). The amino acid distributions in these meteorites are dominated by glycine, alanine, valine, and aspartate, consistent with prebiotic synthesis experiments and strongly biased toward residues compatible with β-sheet formation. These results demonstrate that extraterrestrial delivery could have provided a continuous source of short peptide chains alongside free amino acids (Cronin & Pizzarello, 1983; Glavin et al., 2020).

Abiotic peptide synthesis under hydrothermal conditions has been demonstrated through carbonyl sulfide–mediated condensation (Huber & Wächtershäuser, 1998). These reactions generate short oligomers of glycine, alanine, and valine under simulated vent conditions, reaching chain lengths of 6–10 residues. Iron–sulfur minerals common in vent chimneys also catalyze peptide bond formation and stabilize products. Such oligomers are particularly well suited to β-sheet assembly, given their alternating polar/nonpolar character.

Laboratory simulations of drying in hot spring pools show that repeated dehydration/rehydration cycles drive peptide bond formation from amino acid mixtures (Rajamani et al., 2008; Forsythe et al., 2015). These experiments yield a range of short oligomers, typically 8–12 residues in length, with glycine, alanine, and aspartate dominating the products. Importantly, these lengths overlap with the requirements for β-sheet strands capable of oligomerization, suggesting that natural wet–dry cycles could have continuously generated pore-forming candidates.

Fox and Harada (1958) demonstrated that heating dry mixtures of amino acids to 170–200 °C produces “proteinoids,” irregular polymers often 10–40 residues long, enriched in aspartate, glutamate, alanine, and valine. Some of these aggregates spontaneously form microspheres with semi-permeable boundaries (Fox & Dose, 1977). While not sequence-specific, these polymers further demonstrate the ease with which short peptide-like chains could form in prebiotic settings.

Together, these findings confirm that short peptides were not only theoretically possible but actually present in multiple plausible environments; extraterrestrial delivery, hydrothermal vents, hot spring cycles, and thermal polymerization. Their typical composition; rich in glycine, alanine, valine, and aspartate maps directly onto the requirements for β-sheet oligomerization. This chemical reality strengthens the hypothesis that β-sheet peptides could have aggregated into primitive pore-formers within fatty acid vesicles, thereby enabling the permeability necessary for protocell function.

The ability of peptides to modulate protocell membranes depends strongly on their secondary structure. In modern biology, peptide-mediated pores fall broadly into two categories; α-helical pores and β-sheet pores, with less common roles for disordered coils and β-hairpin motifs. Each structure imposes distinct sequence requirements, modes of assembly, and pore-forming mechanisms. By surveying these structural options, both in modern analogues and in prebiotic plausibility, we can evaluate which pathways were most likely to provide primitive transport in protocells.

α-Helical Peptides

In modern biology, α-helical amphipathic peptides represent the most common and well-studied pore-formers. They fold into helical structures where hydrophobic residues cluster on one side of the helix and polar/charged residues segregate on the opposite side. When such helices insert into lipid bilayers, the hydrophobic face aligns with the lipid tails while the hydrophilic face can line aqueous channels. Multiple helices can then oligomerize into stable pores through several canonical models (Shai, 1999; Huang et al., 2004; Wimley, 2010).

Several distinct mechanisms have been described for α-helical peptide pore formation in membranes. In the barrel-stave model, amphipathic helices insert perpendicularly into the bilayer and align side by side, creating a cylindrical channel whose lumen is lined by the peptide backbones (Shai, 1999; He et al., 1996). The toroidal pore model, exemplified by magainins, involves peptides inducing curvature of the lipid bilayer so that the resulting pore is lined partly by peptide helices and partly by lipid headgroups (Ludtke et al., 1996; Huang et al., 2004). In contrast, the carpet model does not generate well-defined channels; instead, peptides accumulate on the membrane surface in a carpet-like fashion, destabilizing the bilayer until local disintegration occurs, producing transient leakage rather than stable pores. These mechanisms demonstrate that α-helical peptides can generate both transient and stable pores, directly altering membrane permeability (Wimley, 2010; Yeaman & Yount, 2003).

From experimental studies of antimicrobial peptides and toxins, α-helical pore-formers share common sequence features (Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Bechinger, 1997; Wimley, 2010). For α-helical peptides, several sequence features are consistently associated with pore-forming activity. Effective helices are typically between 15 and 30 amino acids in length, sufficient to span the hydrophobic core of fatty acid or phospholipid bilayers. They display moderate hydrophobicity, with approximately 40–60% of residues being hydrophobic, most often alanine, valine, leucine, or isoleucine. Crucially, they must also be amphipathic, arranging hydrophobic and polar side chains in a repeating pattern every three to four residues, which produces a hydrophobic moment of at least 0.35 (Eisenberg et al., 1982). A net positive charge of +2 to +6, usually provided by lysine and arginine residues, promotes electrostatic binding to negatively charged membrane headgroups. Finally, pore-forming helices require an appropriate balance of rigidity and flexibility; rigid hydrophobic stretches provide stability within the bilayer, while the inclusion of more flexible residues prevents uncontrolled aggregation and allows efficient membrane insertion.

Several well-characterized antimicrobial and toxic peptides exemplify how α-helices function as efficient pore-formers in modern biology. Magainin-2, a frog skin AMP of approximately 23 residues with a net charge of +3 and a hydrophobic moment of 0.45, forms toroidal pores in bacterial membranes (Zasloff, 1987). Melittin, the 26-residue principal component of bee venom, carries a net charge of +6 and a hydrophobic moment of 0.40, acting as a potent lytic peptide that destabilizes membranes. Alamethicin, a 20-residue fungal peptide with a neutral charge and hydrophobic moment of 0.42, provides the classic example of a barrel-stave pore, whose stability is enhanced by membrane voltage (He et al., 1996). Modern membrane-active peptide qualities are displayed in

Table 2.

Despite their dominance in extant biology, α-helical pores are unlikely to have been the earliest solution to membrane transport on the prebiotic Earth. Prebiotic syntheses such as Miller–Urey experiments, meteorite analyses, and hydrothermal chemistry consistently produced amino acid inventories dominated by glycine, alanine, valine, and aspartate (Burton et al., 2012; Martins et al., 2008), whereas helix-promoting residues such as leucine, isoleucine, and lysine were comparatively rare. The abundance of glycine further worked against helix formation, as its high conformational flexibility destabilizes the hydrogen-bonded helical backbone (Wimley, 2010). In modern antimicrobial helices, electrostatic binding to negatively charged membranes depends on lysine and arginine, yet such cationic residues were scarce in early inventories; although ornithine-like analogs or polyamines may have provided some substitution, they would have been less effective (Schlesinger & Miller, 1983). Finally, most abiotically produced peptides were only 6–12 residues in length (Huber & Wächtershäuser, 1998; Rajamani et al., 2008), generally too short to span bilayers and form stable transmembrane helices. Together, these constraints suggest that while α-helices dominate pore formation today, their emergence under prebiotic conditions was unlikely without prior enrichment of helix-stabilizing amino acids and elongation mechanisms. Thus, while α-helices provide a powerful model for pore formation in modern biology, their structural and sequence requirements make them less plausible as the earliest prebiotic pores. They may have emerged later, once biosynthetic pathways expanded the amino acid repertoire.

β-Sheet Peptides

β-sheets consist of peptide strands aligned side-by-side, stabilized by hydrogen bonds between backbone groups. When amphipathic, β-sheets display alternating hydrophobic and polar side chains, producing one hydrophobic face (lipid-facing) and one hydrophilic face (pore-lining). Several β-strands can oligomerize into higher-order structures capable of pore formation (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002; Sengupta et al., 2014). β-sheet peptides are also capable of forming membrane pores through several distinct mechanisms. In the β-barrel model, multiple β-strands assemble into a cylindrical structure in which hydrophobic residues face outward to interact with lipid tails, while polar residues line the aqueous pore lumen, a motif characteristic of porins and many protein toxins. Alternatively, amyloid-like oligomers of short β-sheets can insert irregularly into membranes, generating leaky ion-conducting channels that resemble those implicated in amyloid-associated cytotoxicity. A third example is provided by defensins, small cysteine-stabilized β-sheet peptides that assemble into pores in microbial membranes as part of innate immune defense. Collectively, these models demonstrate that β-structured peptides, though less orderly than α-helical channels, are fully capable of producing functional membrane pores. These mechanisms demonstrate that β-sheet pores, though often less ordered than α-helical ones, can still produce ion-conducting channels.

Experimental and simulation studies indicate that β-sheet peptides have distinct requirements for pore formation compared with α-helices (Bechinger, 1997; Soto, 2003; Jang et al., 2011). Individual β-strands are typically shorter, with effective pore-formers ranging from 8 to 16 residues in length. Their amphipathicity arises from an alternating pattern of hydrophobic and polar residues every two positions, producing one hydrophobic face directed toward the lipid tails and one polar face oriented toward the aqueous pore interior. Successful insertion into membranes requires that the outward-facing surface be enriched in residues such as alanine, valine, leucine, or isoleucine to ensure hydrophobic anchoring. A mild net positive charge, generally between +1 and +3, facilitates initial binding to negatively charged fatty acid membranes, though this feature is less critical than in α-helical systems. Crucially, β-sheet pores rely on oligomerization; single strands are insufficient, and functional channels arise only when multiple β-strands assemble into β-barrels or amyloid-like bundles.

Several well-studied systems illustrate how β-sheet peptides can form membrane pores in modern biology. Amyloid β (Aβ) assembles into β-sheet oligomers that insert into membranes and act as calcium-permeable channels, a mechanism implicated in Alzheimer’s disease pathology (Arispe et al., 1993). Human defensins, small β-sheet peptides stabilized by disulfide bonds, disrupt bacterial membranes through pore formation as part of the innate immune system (Ganz, 2003). In addition, Congo red–binding amyloids provide experimental models of β-sheet assemblies that generate ion-conducting pores in lipid bilayers (Jang et al., 2011). Together, these examples confirm that β-structured peptides, like their α-helical counterparts, are fully capable of producing functional membrane pores.

Unlike α-helical motifs, β-sheet structures are closely aligned with the constraints of prebiotic chemistry. The amino acid inventories generated in meteorites and prebiotic synthesis experiments were dominated by glycine, alanine, and valine; residues that readily support β-sheet formation (Glavin et al., 2020; Martins et al., 2008). The abundance of glycine, which destabilizes α-helices, instead promotes turns and facilitates the tight packing of β-strands, further biasing early peptides toward sheet-like conformations. Length requirements also favor this outcome; oligomers of only 8–12 residues, commonly produced in wet–dry cycling and observed in meteoritic extracts, are already sufficient to form β-sheet strands. Environmental conditions on the early Earth, including wet–dry cycling in hot springs, high salt concentrations in hydrothermal systems, and the concentrating effects of eutectic ice phases, would have further encouraged peptide aggregation and oligomerization. Taken together, these factors strongly suggest that β-sheet peptides represent a plausible class of prebiotic pore-formers, producing irregular but functional channels within fatty acid vesicles. The structural and functional features of α-helical and β-sheet peptide pores are compared in

Table 3.

Other Motifs

In addition to α-helices and β-sheets, several other peptide conformations may have interacted with primitive membranes, though their pore-forming potential appears limited. Random coils, composed of unordered and flexible chains, rarely form organized transmembrane structures. Instead, some coil-rich peptides act through a carpet-like mechanism in which they adsorb to the membrane surface and disrupt bilayer integrity in a nonspecific manner, producing transient leakage rather than stable channels (Wimley, 2010). In a prebiotic context, such disordered peptides could have increased vesicle permeability but are unlikely to have yielded defined pores.

Another possible motif is the β-hairpin, consisting of two antiparallel β-strands joined by a short turn. While individual hairpins are not sufficient to form pores, they can oligomerize into β-barrels and thereby serve as nucleation motifs for more complex pore structures (Fernandez-Lopez et al., 2001). Such assemblies may have acted as evolutionary stepping-stones toward stable β-barrel pores.

Less relevant to early Earth are polyproline helices and rare helical conformations such as 310 and π-helices. These structures are rigid or unstable, typically requiring residues such as proline, which was scarce in prebiotic inventories (Burton et al., 2012; Schlesinger & Miller, 1983). Consequently, their capacity to form pores is negligible, and their contribution to early membrane transport is likely to have been minimal (Bechinger, 1997; Wimley, 2010).

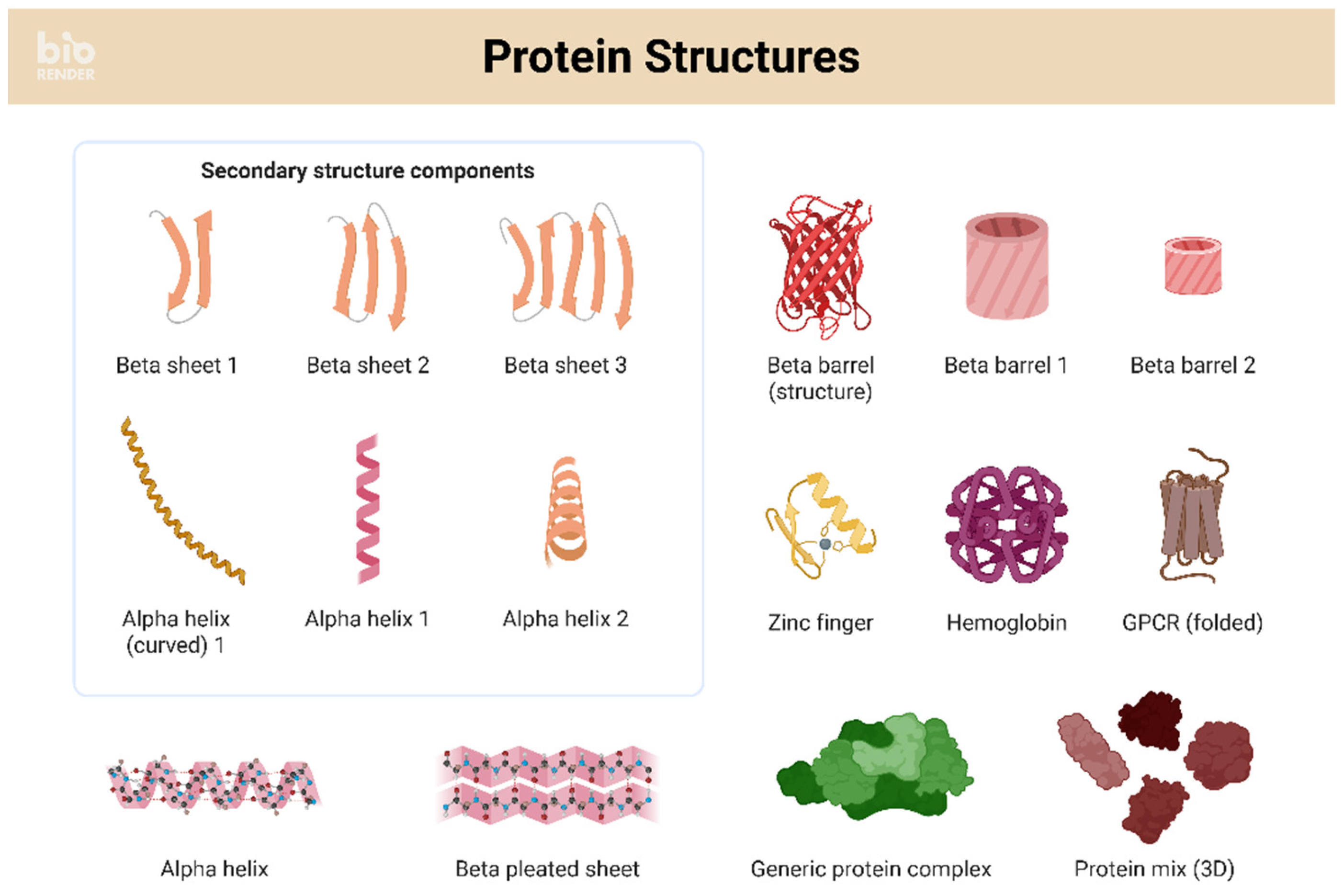

In summary, different secondary structures present contrasting prospects for peptide-mediated pore formation in protocells. α-helical peptides are highly efficient pore-formers in modern biology, but their emergence under prebiotic conditions was constrained by amino acid availability, sequence length, and the destabilizing effect of glycine. β-sheet peptides, though generally less ordered and efficient, are far more consistent with prebiotic chemistry; short oligomers rich in glycine, alanine, and valine could readily assemble into leaky but functional pores capable of increasing membrane permeability. Other structural motifs, such as random coils and β-hairpins, may have contributed indirectly by destabilizing bilayers or nucleating more complex β-barrel assemblies, but are unlikely to have functioned as independent pore-formers. Taken together, this comparative analysis suggests that β-sheet oligomers represent the most plausible candidates for resolving the permeability barrier in fatty acid vesicles during the earliest stages of protocell evolution (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Mansy & Szostak, 2008). Different protein structures have been demonstrated in

Figure 1.

Interaction of Peptides with Early Membrane Candidates and Promoting Environments

The pore-forming potential of peptides depends not only on their intrinsic secondary structure but also on the type of protocell membrane and the geochemical conditions of the early Earth. Here, it is evaluated how different peptide conformations would interact with each major membrane candidate and how specific environments could favor or hinder these processes.

The ability of peptides to alter protocell permeability depends fundamentally on the structural nature of the compartment boundary. Different candidate membrane models proposed for the early Earth present very different opportunities and limitations for peptide insertion.

Hydrophobic droplets composed of long-chain hydrocarbons or fatty acids represent one of the simplest compartment models. However, because such droplets lack a bilayer structure, they do not provide the hydrophobic core and polar interface required for transmembrane peptide assembly (Deamer & Pashley, 1989; Deamer, 1997). At most, amphipathic peptides might adsorb weakly to the droplet surface, with hydrophobic residues buried in the hydrocarbon phase and polar residues facing the aqueous environment. This interaction could slightly influence surface tension but would not generate defined aqueous channels. As a result, oil droplets remained essentially impermeable and cannot be considered realistic hosts for peptide-mediated pores.

Micelles, which form from single-chain amphiphiles such as short fatty acids, provide a more membrane-like interface but suffer from extreme curvature and small size. Their monolayer geometry does not allow peptides to insert and span cooperatively, and their limited internal volume further reduces functional relevance (Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). While peptides may perturb the micelle surface or transiently insert into shallow regions of the aggregate, the geometry precludes the assembly of stable multi-peptide pores. Consequently, micelles could not have supported organized transport channels and are unlikely to have played a central role in peptide-based permeability.

Among prebiotic compartments, fatty acid bilayer vesicles stand out as the most compelling analogues of modern membranes. Their bilayer architecture provides a hydrophobic core, 2–3 nm in thickness, sufficient to accommodate transmembrane peptides (Budin & Szostak, 2011). In this context, amphipathic α-helices of 15–25 residues could, in principle, insert perpendicularly and span the bilayer, forming barrel-stave or toroidal pores if sequences were sufficiently enriched in helix-promoting residues. β-sheet peptides, typically 8–16 residues in length, could also oligomerize into β-barrels or amyloid-like assemblies that puncture the bilayer and create leaky but functional channels (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002). Experimental studies of fatty acid vesicles have demonstrated that peptides can indeed modulate permeability, with leakage assays confirming that short amphipathic sequences can destabilize bilayers and allow the passage of ions and small molecules (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Mansy et al., 2008). Vesicles, therefore, represent the most favorable protocell model for peptide-mediated pore formation, both structurally and experimentally.

Coacervate droplets, formed through the liquid–liquid phase separation of charged polymers such as peptides, RNA, or polysaccharides, lack a lipid bilayer altogether. Instead, they present a semi-permeable polymer-rich interface that allows solutes to partition in or out according to electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. In such systems, peptides cannot form classical transmembrane pores. However, their presence could alter permeability indirectly by modulating charge density or creating localized “gates” through polymer–peptide interactions (Oparin, 1938; Keating, 2012). Thus, while coacervates may have offered compartmentalization, they did not provide the structural framework for bilayer-spanning pores, and their permeability mechanisms differ fundamentally from those of vesicular membranes.

At alkaline hydrothermal vents, porous mineral structures composed of iron sulfides and other precipitates could have confined prebiotic chemistries. These compartments, however, consist of rigid solid walls and cannot host membrane insertion events. Peptides might have adsorbed to mineral surfaces, perhaps creating selective adsorption/desorption pathways for ions or nucleotides, but they could not form aqueous pores analogous to those in lipid bilayers (Russell & Martin, 2004). Mineral compartments are therefore relevant as catalytic and concentrating environments but not as systems in which peptide pore formation could have played a direct role.

Taken together, these comparisons highlight that while multiple forms of protocell candidates may have coexisted on the early Earth, only fatty acid bilayer vesicles possessed the structural properties necessary to host peptide-mediated pores. Other models, such as droplets, micelles, coacervates, and mineral pores, may have facilitated compartmentalization or catalysis but could not support bilayer-spanning peptide channels. This conclusion reinforces the centrality of vesicles as the key protocell model for evaluating the role of prebiotic peptides in overcoming the membrane transport barrier (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Mansy & Szostak, 2008). The feasibility of peptide-mediated pore formation across different protocell membrane candidates and the β-sheet peptide pore formation across different protocell membrane candidates is summarized in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

Environmental Influences on Pore Formation

The structural potential of peptides to form pores in primitive membranes was strongly conditioned by the diverse environments of the early Earth. Each setting imposed unique physicochemical constraints on peptide stability, membrane integrity, and the likelihood of oligomerization.

Alkaline vent systems, such as those represented by the Lost City hydrothermal field, are characterized by high pH (typically 9–11), elevated ionic strength, and porous mineral scaffolds composed of iron-sulfur precipitates. These conditions present both challenges and opportunities for protocell formation. Fatty acid vesicles are known to destabilize in high-salt environments due to charge shielding and fatty acid precipitation; however, mixtures containing alcohols, glycerol monoesters, or isoprenoid derivatives display greater stability under such conditions (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Mansy & Szostak, 2008). High ionic strength also promotes peptide aggregation, which may encourage β-sheet oligomerization into amyloid-like pores (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002). By contrast, α-helices would be less favored in such glycine-rich peptide pools, particularly given the destabilizing effect of divalent cations on helix formation (Wimley, 2010). Thus, alkaline vents likely offered a moderately favorable environment for β-sheet pore assembly, though their compatibility with protocell stability remains debated. While alkaline hydrothermal vents offer catalytic scaffolds and sustained energy flux (Russell & Martin, 2004), the high ionic strength destabilizes pure fatty acid vesicles (Monnard & Deamer, 2002). Mixed amphiphiles (Mansy & Szostak, 2008) or mineral adsorption could mitigate this, but such compartments may have supported peptide synthesis more than peptide pore activity. Thus, vents may have acted as “cradles of chemistry” rather than hosts of permeability.

Freshwater hydrothermal pools undergoing periodic dehydration and rehydration cycles have been proposed as especially conducive to prebiotic polymerization (Rajamani et al., 2008; Forsythe et al., 2015). During the drying phase, amino acids and short peptides are concentrated, driving condensation reactions that extend peptide chains. Simultaneously, dehydration favors β-sheet formation, as removal of bulk water enhances inter-strand hydrogen bonding and sheet packing. Upon rehydration, fatty acid vesicles reassemble, encapsulating both peptides and nucleotides. This cyclic process provides a dual advantage; it generates short oligomers in the β-sheet length range (8–12 residues) and promotes their physical incorporation into membranes. Consequently, freshwater hot springs represent one of the most favorable environments for prebiotic β-sheet pore formation, coupling peptide synthesis, structural assembly, and membrane encapsulation in a single setting (Rajamani et al., 2008; Forsythe et al., 2015).

Shallow marine environments with regular tidal cycling provide another plausible context for early protocells. Ionic strength in these settings is moderate to high, which destabilizes pure fatty acid membranes but can be mitigated by stabilizers such as glycerol monoesters, alcohols, or small organic anions like citrate (Apel et al., 2002; Mansy et al., 2008). Once stabilized, these vesicles could, in principle, support peptide insertion. Both α-helices and β-sheets may have been viable in tidal pools, although α-helical pores would have required longer chains enriched in leucine, isoleucine, and cationic residues; amino acids known to be rare in prebiotic syntheses. In contrast, β-sheet oligomers, enriched in glycine, alanine, and valine, would have been more chemically accessible. Thus, tidal pools represent an intermediate scenario, offering moderate favorability for pore formation by either structural class, but with a bias toward β-sheet feasibility given the early amino acid repertoire.

Frozen environments, including subglacial lakes and ice-covered ponds, produce eutectic brines in which solutes are concentrated into liquid channels between ice crystals. These conditions slow hydrolysis and protect fragile molecules from degradation, extending the lifetime of peptides and nucleotides (Kanavarioti et al., 2001). Concentration effects also favor aggregation, making β-sheet oligomerization particularly likely. Although low temperatures reduce membrane fluidity, fatty acid vesicles remain stable at subzero conditions and can incorporate solutes during freeze–thaw cycles (Trinks et al., 2005; Deamer, 1997). This environment, therefore, provides a moderate degree of plausibility for peptide-mediated pores, with β-sheets favored over α-helices due to chain length and sequence considerations.

Porous mineral structures formed at hydrothermal vents, composed largely of iron sulfides (FeS, FeS2), have been proposed as natural reactors for prebiotic chemistry (Russell & Martin, 2004). These systems provide catalytic surfaces, steep pH gradients, and redox disequilibria that could drive early metabolic reactions. However, they lack bilayer membranes altogether and therefore do not support the classical mechanism of peptide insertion and pore formation. Peptides may adsorb to mineral surfaces, modulating ion transport across mineral barriers or creating selective adsorption/desorption pathways, but they would not form aqueous transmembrane channels. As such, mineral compartments are relevant to prebiotic catalysis but not to the problem of bilayer permeability in protocells.

Taken together, these environmental analyses highlight that freshwater hot springs with wet–dry cycling were the most favorable setting for β-sheet pore formation, coupling peptide synthesis, aggregation, and vesicle assembly. Ice eutectic brines also offered protective and concentrating environments for β-sheet oligomers, while alkaline vents and tidal pools provided conditional support, with varying degrees of membrane stability challenges. Mineral compartments, while important as catalytic scaffolds, do not contribute directly to peptide-mediated pore formation (Deamer, 1997; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). Environmental influences on the feasibility of peptide pore formation in protocells are explained in

Table 6.

The comparative analysis of environments highlights that only a subset of early Earth settings offered favorable conditions for peptide-mediated pore formation. Among these, freshwater hot springs with wet–dry cycling and alkaline hydrothermal systems stabilized by mixed amphiphiles stand out as the most compelling. Hot-spring cycles provide a natural coupling between synthesis and function; drying phases concentrate amino acids and nucleotides, driving peptide condensation and promoting β-sheet packing, while rehydration phases allow fatty acid vesicles to reassemble and incorporate the newly formed oligomers (Rajamani et al., 2008; Forsythe et al., 2015; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). This setting, therefore, couples polymerization, aggregation, and membrane encapsulation in a single geochemical cycle. Alkaline vent systems, though more chemically extreme, can stabilize vesicles if mixed amphiphiles are present and simultaneously promote peptide aggregation through high ionic strength. In both cases, the chemical environment is well suited to support the assembly of β-sheet oligomers within vesicle membranes (Apel et al., 2002; Mansy & Szostak, 2008; Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002).

By contrast, other settings appear less favorable. Mineral compartments and fatty acid droplets provided physical confinement but lacked bilayer membranes and therefore could not host transmembrane peptide pores (Deamer & Pashley, 1989; Deamer, 1997; Russell & Martin, 2004). Micelles were too small and highly curved to accommodate multi-peptide assemblies (Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978; Monnard & Deamer, 2002), while coacervates relied on polymer-rich boundaries that permitted solute partitioning but not true channel formation. Although these alternative models demonstrate the diversity of potential prebiotic compartments, their structural features limit their relevance for peptide-mediated transport.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that the environments most favorable for the origin of peptide pores were those that not only facilitated peptide synthesis and aggregation but also supported the bilayer vesicles required for pore activity. This dual requirement, polymer formation and membrane integrity, was best met in freshwater hot-spring pools and alkaline hydrothermal systems, making them prime candidates for the earliest emergence of peptide-mediated transport (Deamer, 1997; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). The feasibility of α-helical and β-sheet peptide pores across different protocell models is explained in

Table 7.

Taken together, the convergence of freshwater hot-spring environments, fatty acid vesicles, and β-sheet peptide oligomers provides a scenario for resolving the early permeability problem. Wet–dry cycling in hot springs not only concentrated amino acids and drove their condensation into short oligomers (Rajamani et al., 2008; Forsythe et al., 2015) but also promoted β-sheet packing and aggregation (Forsythe et al., 2015; Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002). Upon rehydration, fatty acid vesicles re-formed, encapsulating both peptides and nucleotides (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Mansy et al., 2008). Within this setting, β-sheet pores, though irregular and leaky, would have been sufficient to permit the influx of ions and nucleotides, thereby enabling protocells to sustain rudimentary replication cycles (Adamala & Szostak, 2013; Mansy et al., 2008). In this way, hot-spring vesicles stabilized by β-sheet pores offer a coherent pathway toward the encapsulation and maintenance of replicators, bridging the gap between simple chemical compartments and the first life-like systems (Deamer, 1997).

Simulation Data and Methodology

One relevant dataset for evaluating the plausibility of prebiotic peptide structures comes from the work of Stefano Piotto and colleagues, who developed a stochastic simulation platform (“Genesys”) to model the spontaneous polymerization of amino acids under early Earth–like conditions. Their simulation approach restricted the amino acid pool to six species plausibly available in the prebiotic inventory (Gly, Ala, Val, Asp, Glu, and Ser), with concentrations based on meteorite data and synthesis energetics (Shimoyama et al., 1979; Martins et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2012). The program iteratively generated peptides through random ligation and fragmentation cycles, with sequence similarity used as a proxy for catalytic reinforcement. Over thousands of generations, this method yielded a population of short glycine-rich peptides that could cluster into autocatalytic sets, showing periodic fluctuations in abundance, a primitive form of “dynamic memory” in the system. The supplementary dataset includes dozens of representative sequences obtained from these runs. They are typically short oligomers (10–40 residues), heavily biased toward glycine with smaller contributions from alanine and valine. Such sequences lack the charged and bulky residues needed for stable amphipathic α-helices, but their composition is consistent with β-strand formation and aggregation. From this set, it is possible to extract individual candidates for further structural prediction, to assess whether any display features compatible with membrane interaction.

Among the ~80 peptide sequences generated in Piotto’s Genesys simulations, secondary structure prediction with JPred4 identified approximately 22 with β-strand annotations. These sequences were typically glycine-rich with interspersed alanine and valine residues, producing alternating hydrophobic and polar patterns compatible with sheet-like conformations. The remainder of the dataset was predicted as largely disordered, random coils. This distribution underscores a natural chemical bias; while most abiotically generated peptides would have been inert, a minority displayed β-strand potential consistent with aggregation and membrane interaction.

To evaluate whether a prebiotic β-strand peptide could plausibly act as a primitive pore or leaky channel, several structural and environmental features must be considered. The first requirement is strand length. For a peptide segment to disturb or span a fatty-acid bilayer of roughly 2–3 nm thickness (Monnard & Deamer, 2002), a contiguous β-strand region of at least 8 residues is necessary, with 8–12 residues being optimal. This range corresponds well to what is observed in β-barrel porins of modern bacteria, where each strand is typically 10 residues long (Schulz, 2002), and in designed β-strand pore-forming peptides (Rausch et al., 2007).

A second key feature is composition. Effective strands require a balance of small hydrophobic residues, particularly alanine, valine, and leucine, with glycine assisting close packing, amounting to at least 40% of the segment. Too few hydrophobes, and the peptide will not partition into the bilayer; too many, and it risks precipitating or forming insoluble aggregates. Studies of protegrins and other β-sheet antimicrobial peptides illustrate how this balance underpins membrane activity (Tam et al., 2000).

Third, the sequence must display amphipathic patterning characteristic of β-strands; an alternating hydrophobic–polar periodicity of two residues. This arrangement produces one face of the strand oriented toward the lipid tails and another facing the pore lumen or aqueous interface, an essential feature seen both in natural β-barrels and in synthetic pore-forming designs. A hydrophobic moment μH ≳ 0.30–0.35 on a helical wheel; for β-strands, an alternating hydropathy pattern (periodicity = 2) that yields one lipid-facing and one water-facing side (Jang et al., 2011).

Charge also plays a supporting role. Modern pore-forming peptides are often cationic, but for early fatty-acid membranes, which carry negatively charged headgroups, even a net charge of +1 to +2 would have been sufficient to promote binding (Zasloff, 2002). Given that lysine and arginine were scarce prebiotically, alternative cationic moieties such as ornithine-like residues or polyamines could have provided the necessary interactions (Schlesinger & Miller, 1983).

Equally critical is oligomerization propensity. Individual β-strands rarely form pores alone; they must assemble into oligomers or barrel-like structures. Moderate β-aggregation tendency, aided by glycine-rich turns, can drive such assemblies without immediately collapsing into inert fibrils. Amyloidogenic peptides demonstrate how even short oligomers can puncture bilayers and cause graded leakage (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Rausch et al., 2007).

Finally, environmental compatibility must be considered. Prebiotic membranes were not phospholipid bilayers but fatty-acid vesicles, stable only within specific pH and ionic ranges. Experimental work has shown that peptide insertion and leakage activity are strongly influenced by these conditions; for example, β-strand conformations are promoted during drying–rehydration cycles and when peptides interact with fatty-acid vesicles under mildly alkaline pH (Rajamani et al., 2008). These settings favor peptide aggregation and pore-like behavior, even when the sequences would appear too weak under modern cellular conditions.

Taken together, the minimal triad for plausibility is a strand of 8–12 residues, a clear alternating hydrophobic–polar pattern with sufficient hydrophobic content, and a demonstrated ability to oligomerize under relevant environmental conditions. Supplementary features such as a slight positive charge and environmental stability further increase the likelihood of function. While no single criterion guarantees pore formation, candidates meeting these combined standards can reasonably be considered capable of producing at least leaky defects in fatty-acid membranes, thereby overcoming the permeability barrier of protocells.

However, it is important to emphasize that these criteria largely reflect what is known from modern protein pores and antimicrobial peptides, which evolved under very different constraints. Fatty acid vesicles, the most plausible protocell membranes, are thinner, more fragile, and more permeable than phospholipid bilayers, meaning that even shorter β-strand segments could have perturbed them sufficiently to create transient leaks. Laboratory studies confirm that relatively small peptides and even amorphous aggregates can destabilize fatty acid vesicles, allowing ion and nucleotide passage without the need for well-formed channels (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Mansy et al., 2008). Similarly, amyloid-like assemblies built from short repeats demonstrate that oligomers smaller than canonical β-barrels can still puncture membranes and cause leakage (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that although prebiotic peptides may not have met the exact structural requirements of modern pore-formers, their aggregation, and amphipathic tendencies could nonetheless have produced destabilizing or leaky defects in fatty acid membranes, functionally relieving the permeability barrier under early Earth conditions. Based on these criteria, the set of 22 β-strand–annotated sequences obtained from the JPred4 analysis was screened. The majority displayed only short or fragmented β-strand segments, insufficient to meet the minimal requirement for membrane-spanning strands.

Among the JPred4 set, four sequences contained contiguous β-strands of five residues, the longest observed in the dataset. To refine further, their physicochemical properties were compared using ProtParam, focusing on amphipathicity, charge, and hydrophobic balance. To prioritize, two sequences were selected, each containing a five–residue β-run and promising amphipathicity. These candidates (1 and 2) were then subjected to further physicochemical evaluation to assess their potential for membrane interaction under prebiotic conditions.

1: GGGVGGGGGGAVVAGAGGGA

2: AGAGVGGGGGGAGVGVGAGVGGVEGGGAGGGAAGGGAAGVGGGGGGEAGGGG

Physicochemical screen (ProtParam) for “1” (GGGVGGGGGGAVVAGAGGGA, 20 aa), the peptide is short (20 aa), uncharged at pH 7 (net 0, pI ≈ 5.52), and hydrophobic by GRAVY (+0.73), with 65% Gly, 20% Ala, and 15% Val. The aliphatic index (63.5) is moderate, while the instability index (48.1) flags limited folded stability (expected for short, glycine-rich peptides). Taken together, the neutral net charge suits binding to negatively charged fatty-acid membranes without requiring Lys/Arg; the high GRAVY and A/V content support partitioning into the bilayer; and the heavy glycine bias suggests flexibility that favors β-aggregation/oligomerization over stable, ordered barrels. These features are consistent with transient leakage/destabilization, rather than a well-defined pore. (Gasteiger et al., 2005; Eisenberg et al., 1982; Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010.)

Physicochemical screen (ProtParam) for “2”, this peptide is longer (52 aa) with a net charge of −2 (pI ≈ 3.8), very glycine-rich (65%), and a moderate fraction of Ala/Val (≈31%). Its GRAVY score is +0.44, indicating moderate hydrophobicity, while the aliphatic index is lower (52.7) than 1’s, 63.5. Unlike 1, “2” is classified as stable (instability index = 37.9), though the excess glycine suggests conformational flexibility and a tendency toward disordered or β-aggregate states. The small negative charge could weaken interactions with fatty-acid vesicles compared to neutral peptides, but not necessarily exclude insertion, since fatty-acid membranes are fragile and tolerate destabilization by acidic peptides (Mansy & Deamer, 2002). Overall, 2 has the advantage of length and stability, but its glycine bias and negative charge make it less optimal than 1 as a pore-forming candidate. It is better interpreted as a membrane destabilizer/aggregator rather than a plausible proto-pore. (Gasteiger et al., 2005; Eisenberg et al., 1982; Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010.)

After screening Piotto’s peptide library, designing a minimal sequence guided by the structural logic outlined above was attempted, alternating hydrophobic and polar residues to promote β-strand amphipathicity, a length close to the minimal bilayer-spanning requirement, and reliance only on amino acids plausibly abundant on the early Earth (Gly, Ala, Val, Asp, Ser). The resulting 10-residue candidate (VGVSDGVAVA) alternates Val/Ala (hydrophobic) with Gly/Ser/Asp (polar/charged), producing a clear amphipathic pattern. Secondary structure prediction with JPred suggested β-strand conformations within the sequence, while ProtParam analysis showed several favorable physicochemical features: 40% Val and 20% Ala contribute strong hydrophobicity (GRAVY +1.53), while Gly (20%) provides flexibility for aggregation. The sequence is nearly neutral (pI 3.8, net charge -1), which would not exclude insertion into fragile fatty-acid membranes known to tolerate acidic peptides (Mansy & Deamer, 2002). Its aliphatic index (136) and very low instability index (0.5) indicate both high thermal stability and a tendency to persist under variable conditions. Taken together, these features suggest that this designed peptide, though short, could plausibly form β-strand aggregates that destabilize or transiently perforate prebiotic membranes, highlighting how simple amphipathic patterns within an early amino acid inventory might have provided primitive transport functions (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011; Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Rajamani et al., 2008; Wimley, 2010). Physicochemical properties of the analyzed prebiotic peptides are displayed in

Table 8.

Implications

The amino acid repertoire available on the early Earth was far from balanced. Meteorite analyses and prebiotic syntheses consistently reveal a dominance of glycine, alanine, valine, and aspartate (Shimoyama et al., 1979; Martins et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2012). This compositional bias had strong structural consequences. Glycine, with its minimal side chain, destabilizes α-helices by introducing flexibility that disrupts backbone hydrogen bonding (Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010), In contrast, it readily supports turns and the tight packing of β-strands. Alanine and valine further reinforce sheet-like structures through alternating polar and non-polar side chains that favor amphipathic β-sheet assembly (Eisenberg et al., 1982). The outcome is a natural skew toward β-structured oligomers rather than helical conformations.

This structural reality reframes the interpretation of simulation data such as Piotto’s peptide pools. The predominance of extended or β-structured conformations in these models is not a failure to produce “modern-like” amphipathic helices, but instead a realistic reflection of the chemical environment of the early Earth. The peptide landscape was not neutral but biased, and this bias favored the formation of aggregates capable of oligomerization and membrane perturbation.

Even when sequences are explicitly designed from plausible prebiotic residues to maximize amphipathicity, as in the case of the 10-residue candidate evaluated here, the outcome points toward leaky β-aggregates rather than stable, protein-like channels. This convergence between simulated libraries and rational design strengthens the case that destabilization was the earliest viable route to permeability.

Fatty acid vesicles, the most compelling protocell candidates, face a fundamental transport barrier. Their bilayers permit the diffusion of small uncharged solutes but exclude nucleotides, oligonucleotides, and divalent ions essential for replication and catalysis. This creates a paradox; compartments protect fragile replicators but also isolate them from their substrates (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Mansy et al., 2008; Adamala & Szostak, 2013).

Within this context, β-sheet oligomers provide a chemically and structurally plausible route to permeability. Though unlikely to form regular, gated pores, their tendency to aggregate and disrupt membranes could have introduced transient leakiness. Such leakage would have been beneficial, not detrimental, at life’s origins. By allowing non-selective influx of nucleotides, ions, and small peptides, β-structured aggregates could have increased the probability that protocells encapsulated both replicators and their building blocks, enabling primitive cycles of replication and metabolism (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011).

The leaky, irregular character of β-sheet oligomers may have represented the first step toward membrane transport. Their lack of selectivity, which would be detrimental in modern cells, was advantageous in prebiotic contexts where maximizing access to scarce resources outweighed the need for control. Over evolutionary time, as biosynthetic capabilities expanded and more helix-promoting residues became available, α-helical amphipathic peptides could emerge. Their efficiency, stability, and capacity for regulated transport would gradually supplant the β-sheet mechanism.

This suggests a plausible trajectory; from β-sheet–driven leakage in the earliest vesicles to α-helical, protein-like pores in more advanced protocells (Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Brogden, 2005; Wimley, 2010). Such a pathway highlights how structural biases in prebiotic chemistry could have shaped not only the emergence of permeability but also the broader transition from stochastic molecular assemblies to genetically encoded functions.

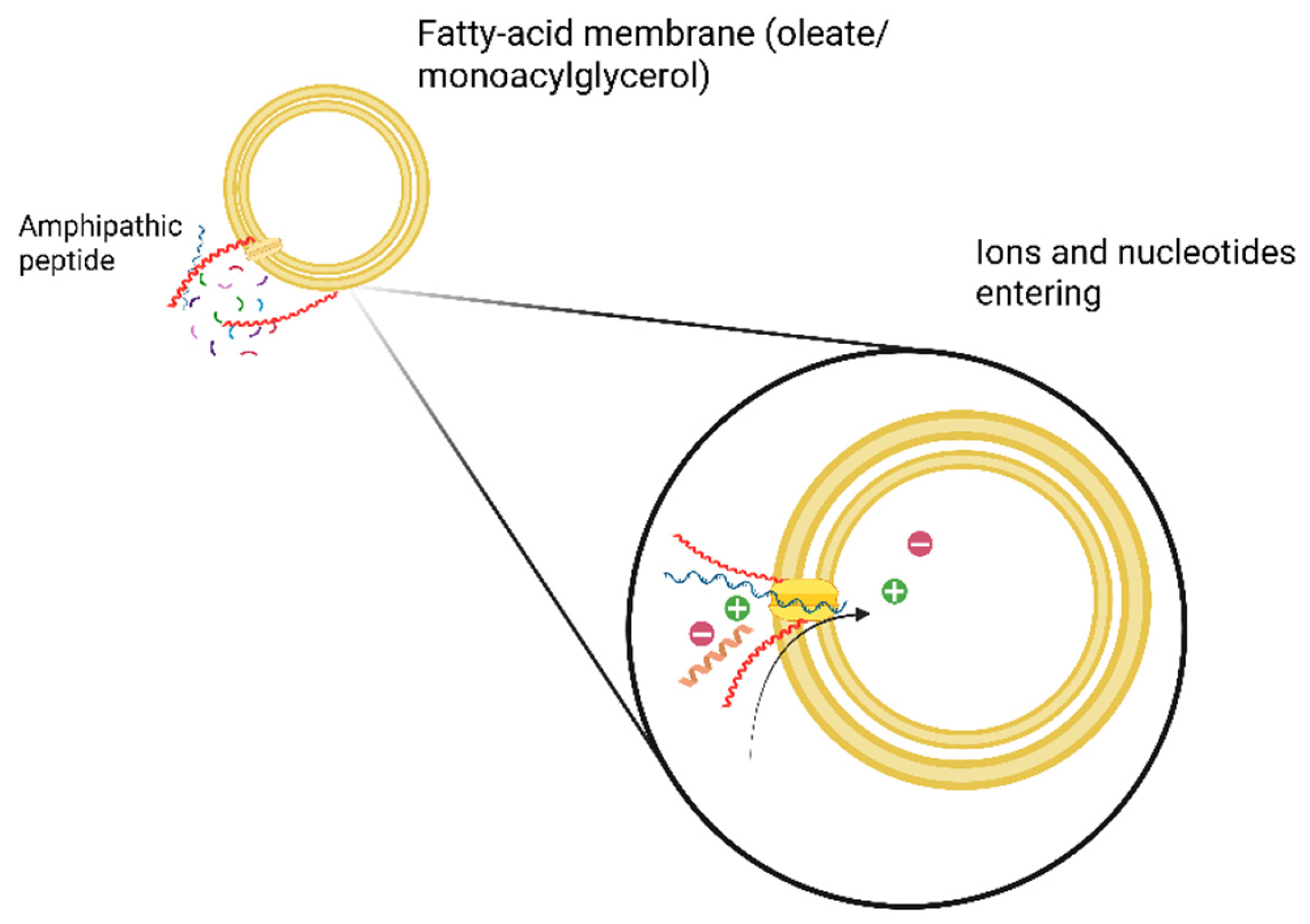

If β-sheet pores were the earliest agents of permeability, their later displacement by α-helical channels requires explanation. As amino acid inventories expanded (Martins et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2012), helix-promoting residues (Leu, Lys, Arg) became more available. α-helices offer tighter gating, higher selectivity, and reduced toxicity compared to leaky β-oligomers (Bechinger, 1997; Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010). This suggests a plausible evolutionary handoff; β-sheets as primitive, leaky conduits, α-helices as efficient, regulated channels. The amphipathic peptide insertion into fatty-acid vesicles increases permeability as conceptually visualized in

Figure 2.

From an evolutionary perspective, even non-selective, leaky pores could have conferred a decisive advantage to primitive protocells. Fatty acid vesicles without permeability agents risked chemical isolation, limiting access to nucleotides, ions, and metabolites required for replication and catalysis (Deamer, 1997; Adamala & Szostak, 2013). In contrast, vesicles incorporating β-sheet oligomers would have allowed continuous exchange with their environment, sustaining internal chemistry despite the absence of active transport. Such leaky channels could also have promoted resource sharing and horizontal exchange between compartments, accelerating the spread of beneficial chemistries (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Mansy & Szostak, 2008). While modern biology relies on selective transport, in early evolution the capacity for non-specific permeability may itself have represented a selectable trait, enabling protocells with peptide-mediated leakage to outcompete sealed counterparts and persist in fluctuating prebiotic environments (Budin & Szostak, 2011).

Conclusions

The problem of permeability has long been recognized as a challenge for protocell models. Fatty acid vesicles can encapsulate and protect replicators, but without a means of molecular exchange, they risk chemical isolation (Monnard & Deamer, 2002; Mansy et al., 2008; Adamala & Szostak, 2013). This review/speculation has examined the possibility that short, abiotically produced peptides contributed to solving this problem through their interactions with primitive membranes.

Modern analogs demonstrate that simple peptides can destabilize bilayers and form pores (Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010), yet the structural requirements of α-helices make them unlikely candidates under prebiotic conditions. The amino acid distributions most consistent with meteorites and laboratory syntheses, dominated by glycine, alanine, and valine, naturally favor β-sheet conformations and oligomerization (Shimoyama et al., 1979; Martins et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2012). While these assemblies are unlikely to have formed regular, gated pores, their ability to induce leakiness and destabilization offers a plausible route to permeability in fatty acid vesicles (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011).

The comparative evaluation of simulation-derived sequences and a rationally designed β-strand candidate underscores this point; while all fall short of the strict criteria for modern pore formers, their amphipathic balance and aggregation propensity can be sufficient to destabilize fatty-acid vesicles. This indicates that peptide-mediated leakage was both chemically plausible and functionally advantageous at life’s beginnings.

In this light, peptide–membrane interactions may have provided a modest but decisive functional advantage, allowing protocells to import nucleotides, ions, and small metabolites in a non-selective manner (Adamala & Szostak, 2013). Such leakiness would have increased the probability that encapsulated replicators could sustain rudimentary cycles of replication and catalysis. Over evolutionary time, as amino acid inventories expanded and biosynthetic pathways diversified, α-helical amphipathic pores could emerge as more efficient and controllable transporters, eventually dominating in modern biology (Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010).

The problem of protocell permeability remains central to understanding life’s emergence. Fatty acid vesicles, though chemically plausible and experimentally tractable, would have risked isolation without a mechanism for solute exchange. This paper has argued that short, glycine/alanine/valine-rich β-sheet oligomers represent a chemically realistic solution, irregular aggregates capable of introducing leaky, non-selective permeability into primitive membranes. The key research question that follows is: Did β-sheet peptides provide the first functional permeability in protocells? Answering this requires moving beyond simulation and speculation into experimental validation. A logical roadmap for testing this hypothesis can be outlined. First, short glycine-, alanine-, and valine-rich oligomers should be synthesized to mirror the amino acid distributions documented in meteorites and laboratory prebiotic chemistry experiments. These peptides can then be reconstituted into fatty acid vesicles under geochemically relevant conditions, including dehydration–rehydration cycles in hot-spring analogs, eutectic freezing environments, or alkaline vent chemistries. Vesicle permeability could be assessed through leakage assays, for example, by monitoring the release of encapsulated fluorescent dyes or the uptake of nucleotides across the membrane. To evaluate structural bias, β-sheet–enriched sequences should be directly compared with α-helical peptide benchmarks, allowing a test of whether early amino acid inventories favored sheet-based leakage mechanisms. By explicitly linking chemical composition to structural outcomes and testable experimental predictions, this framework renders the permeability problem experimentally tractable. If validated, it would strengthen the view that peptide–membrane interactions were not a late biological innovation but an early and decisive step in bridging the transition from abiotic compartments to the first living systems.

It is important to recognize that the arguments presented here remain largely inferential. The case for β-strand peptides as permeability agents rests on indirect evidence drawn from modern antimicrobial peptides, amyloid aggregates, and stochastic simulations, which may not fully capture the chemical realities of the prebiotic Earth. Extrapolations from present-day systems must therefore be treated with caution, as the sequence biases, environmental conditions, and structural outcomes could have differed substantially in early settings. Ultimately, this hypothesis requires direct experimental testing; specifically, the synthesis of prebiotically plausible peptides under cycling conditions and quantitative leakage assays in fatty acid vesicles, before firm conclusions can be drawn about their role in protocell evolution.

If validated experimentally, the β-sheet pore hypothesis would resolve a long-standing objection to fatty acid protocells: their isolation from solute exchange. It would also provide a mechanism for the uptake of nucleotides, ions, and small metabolites critical to both RNA-world and metabolism-first scenarios (Adamala & Szostak, 2013; Russell & Martin, 2004).

Figure 1.

Protein Structures Schematic panel illustrating common secondary and tertiary motifs, including β-sheets, α-helices, β-barrels, zinc finger domains, hemoglobin, G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR), and higher-order protein complexes. These structures represent the fundamental folds from which modern channel- and pore-forming proteins evolved. In the context of protocell membranes, α-helical amphipathic peptides can insert into bilayers to form pores (Bechinger, 1997; Wimley, 2010; Yeaman & Yount, 2003), while β-sheet oligomers and barrels provide alternative pathways for membrane disruption or selective transport (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011). Such motifs serve as conceptual references for hypothesizing prebiotic peptide assemblies and their functional analogues in primitive membranes. Created in BioRender. Sems, A. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/ww5lmkl.

Figure 1.

Protein Structures Schematic panel illustrating common secondary and tertiary motifs, including β-sheets, α-helices, β-barrels, zinc finger domains, hemoglobin, G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR), and higher-order protein complexes. These structures represent the fundamental folds from which modern channel- and pore-forming proteins evolved. In the context of protocell membranes, α-helical amphipathic peptides can insert into bilayers to form pores (Bechinger, 1997; Wimley, 2010; Yeaman & Yount, 2003), while β-sheet oligomers and barrels provide alternative pathways for membrane disruption or selective transport (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011). Such motifs serve as conceptual references for hypothesizing prebiotic peptide assemblies and their functional analogues in primitive membranes. Created in BioRender. Sems, A. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/ww5lmkl.

Figure 2.

Amphipathic peptide insertion into fatty-acid vesicles increases permeability to ions and nucleotides. Schematic model of an oleate/monoacylglycerol fatty-acid vesicle showing insertion of short amphipathic peptides into the bilayer. The disruption creates transient pores that enable ions and nucleotides to cross the membrane. Such mechanisms address the classical permeability problem of protocells, where fatty acid membranes protect encapsulated replicators but restrict molecular exchange. Experimental studies support that simple peptides can destabilize bilayers and induce leakage (Bechinger, 1997; Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010), and that fatty acid vesicles provide a plausible prebiotic environment for such interactions (Deamer & Pashley, 1989; Mansy & Szostak, 2008; Adamala & Szostak, 2013). Created in BioRender. Sems, A. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/erog0rp.

Figure 2.

Amphipathic peptide insertion into fatty-acid vesicles increases permeability to ions and nucleotides. Schematic model of an oleate/monoacylglycerol fatty-acid vesicle showing insertion of short amphipathic peptides into the bilayer. The disruption creates transient pores that enable ions and nucleotides to cross the membrane. Such mechanisms address the classical permeability problem of protocells, where fatty acid membranes protect encapsulated replicators but restrict molecular exchange. Experimental studies support that simple peptides can destabilize bilayers and induce leakage (Bechinger, 1997; Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010), and that fatty acid vesicles provide a plausible prebiotic environment for such interactions (Deamer & Pashley, 1989; Mansy & Szostak, 2008; Adamala & Szostak, 2013). Created in BioRender. Sems, A. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/erog0rp.

Table 1.

Comparison of major protocell models. Fatty acid droplets lack bilayers and are unstable (Deamer, 1997; Deamer & Pashley, 1989). Micelles form monolayer spheres but are size- and salt-limited (Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). Fatty acid vesicles/liposomes resemble modern membranes, with stability, repair, and division (Budin & Szostak, 2011; Mansy & Szostak, 2008; Adamala & Szostak, 2013). Coacervates, first proposed by Oparin (1938), provide semi-permeable compartments (Keating, 2012). Mineral compartments from alkaline hydrothermal vents offer stable but non-membranous boundaries (Russell & Martin, 2004).

Table 1.

Comparison of major protocell models. Fatty acid droplets lack bilayers and are unstable (Deamer, 1997; Deamer & Pashley, 1989). Micelles form monolayer spheres but are size- and salt-limited (Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). Fatty acid vesicles/liposomes resemble modern membranes, with stability, repair, and division (Budin & Szostak, 2011; Mansy & Szostak, 2008; Adamala & Szostak, 2013). Coacervates, first proposed by Oparin (1938), provide semi-permeable compartments (Keating, 2012). Mineral compartments from alkaline hydrothermal vents offer stable but non-membranous boundaries (Russell & Martin, 2004).

| Candidate |

Basic Structure |

Boundary Feature |

Stability |

Similarity to Modern Cells |

| Fatty acid droplets/oil droplets |

Hydrophobic hydrocarbons; spherical droplets in water |

No true membrane; polar ends at surface |

Low; unstable, coalesce easily |

Very low; no bilayer |

| Micelles |

Single-chain amphiphiles; monolayer spheres |

Monolayer boundary, small capacity |

Moderate; stable only at certain pH/salt |

Low; not bilayer |

| Vesicles/Liposomes |

Double-chain amphiphiles; bilayers |

True bilayer enclosing water core |

Relatively high; self-repair, division |

High; closest analogue |

| Coacervates |

Phase-separated droplets of charged polymers |

Semi-permeable polymer boundary |

Variable; depends on composition |

Medium; compartmentalization without lipids |

| Mineral compartments |

Porous FeS/FeS2 or mineral matrices |

Solid mineral walls, no bilayer |

High; geologically stable |

Medium; confinement without membranes |

Table 2.

Modern membrane-active peptide benchmarks. Representative antimicrobial and lytic peptides from extant organisms are included here as reference standards for pore-forming activity. Their physicochemical parameters (length, net charge, average hydrophobicity ⟨H⟩, and hydrophobic moment µH) define the range typically required for efficient bilayer disruption (Eisenberg, Weiss & Terwilliger, 1982; Huang, Chen & Lee, 2004; Wimley, 2010). Magainin-2 exemplifies a toroidal pore-former from amphibians (Zasloff, 1987; Bechinger, 1997), alamethicin, a barrel-stave peptide from fungi (Martin & Williams, 1975; He et al., 1996; Tieleman, Berendsen & Sansom, 2001), and melittin, a potent lytic peptide from bee venom (Habermann, 1972; Terwilliger & Eisenberg, 1982). These benchmarks provide a basis for comparison with prebiotic peptide candidates described in subsequent sections.

Table 2.

Modern membrane-active peptide benchmarks. Representative antimicrobial and lytic peptides from extant organisms are included here as reference standards for pore-forming activity. Their physicochemical parameters (length, net charge, average hydrophobicity ⟨H⟩, and hydrophobic moment µH) define the range typically required for efficient bilayer disruption (Eisenberg, Weiss & Terwilliger, 1982; Huang, Chen & Lee, 2004; Wimley, 2010). Magainin-2 exemplifies a toroidal pore-former from amphibians (Zasloff, 1987; Bechinger, 1997), alamethicin, a barrel-stave peptide from fungi (Martin & Williams, 1975; He et al., 1996; Tieleman, Berendsen & Sansom, 2001), and melittin, a potent lytic peptide from bee venom (Habermann, 1972; Terwilliger & Eisenberg, 1982). These benchmarks provide a basis for comparison with prebiotic peptide candidates described in subsequent sections.

| Peptide |

Length (aa) |

Net Charge (z) |

Hydrophobicity <H> |

Hydrophobic Moment µH |

Activity |

| Magainin-2 (frog AMP) |

23 |

+3 |

0.37 |

0.45 |

Potent pore-former |

| Alamethicin (fungal) |

20 |

0 |

0.41 |

0.42 |

Barrel-stave pores |

| Melittin (bee venom) |

26 |

+6 |

0.47 |

0.40 |

Strong lytic peptide |

Table 3.

Comparison of structural and functional features of α-helical versus β-sheet peptide pores. α-helical pores, typically 15–25 residues long, rely on amphipathic helices with cationic residues and continuous hydrophobic faces (Bechinger, 1997; Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010). By contrast, β-sheet pores are formed by shorter (8–16 aa) strands with alternating hydrophobic/hydrophilic residues that oligomerize into barrels or aggregates (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011). From a prebiotic perspective, α-helical pores were less likely, as glycine destabilizes helix formation, whereas the abundant prebiotic amino acids glycine, alanine, and valine naturally favored β-sheet assemblies (Blackmond, 2019; Martins et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2012). Thus, while helices dominate modern biology, β-sheets represent a more plausible primitive pore architecture under early Earth conditions.

Table 3.

Comparison of structural and functional features of α-helical versus β-sheet peptide pores. α-helical pores, typically 15–25 residues long, rely on amphipathic helices with cationic residues and continuous hydrophobic faces (Bechinger, 1997; Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Wimley, 2010). By contrast, β-sheet pores are formed by shorter (8–16 aa) strands with alternating hydrophobic/hydrophilic residues that oligomerize into barrels or aggregates (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011). From a prebiotic perspective, α-helical pores were less likely, as glycine destabilizes helix formation, whereas the abundant prebiotic amino acids glycine, alanine, and valine naturally favored β-sheet assemblies (Blackmond, 2019; Martins et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2012). Thus, while helices dominate modern biology, β-sheets represent a more plausible primitive pore architecture under early Earth conditions.

| Feature |

α-helix pores |

β-sheet pores |

| Typical length |

15–25 aa (span bilayer) |

8–16 aa per strand |

| Structure |

Amphipathic helix inserts individually |

Multiple strands aggregate into a barrel/oligomer |

| Hydrophobicity |

Continuous hydrophobic face |

Alternating hydrophobic/hydrophilic residues |

| Charge |

Usually, cationic |

Moderately cationic; less strict |

| Prebiotic plausibility |

Less likely (Gly destabilizes helices) |

More likely (Gly/Ala/Val favored sheets) |

Table 4.

Feasibility of peptide-mediated pore formation across different protocell membrane candidates. The likelihood of peptide-mediated pore activity varies across protocell models. Fatty acid/oil droplets lack bilayers and are unstable (Deamer, 1997; Deamer & Pashley, 1989). Micelles are too small and curved for stable peptide assemblies (Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). Fatty acid vesicles represent the most plausible model, with leakage assays and peptide–bilayer studies supporting pore formation (Budin & Szostak, 2011; Mansy & Szostak, 2008; Adamala & Szostak, 2013; Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Bechinger, 1997; Wimley, 2010). Coacervates lack lipid bilayers but may undergo permeability changes through peptide–polyelectrolyte interactions (Oparin, 1938; Keating, 2012). Mineral compartments, proposed in alkaline vent models, provide confinement and catalytic scaffolds but cannot host peptide bilayer pores (Russell & Martin, 2004).

Table 4.

Feasibility of peptide-mediated pore formation across different protocell membrane candidates. The likelihood of peptide-mediated pore activity varies across protocell models. Fatty acid/oil droplets lack bilayers and are unstable (Deamer, 1997; Deamer & Pashley, 1989). Micelles are too small and curved for stable peptide assemblies (Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). Fatty acid vesicles represent the most plausible model, with leakage assays and peptide–bilayer studies supporting pore formation (Budin & Szostak, 2011; Mansy & Szostak, 2008; Adamala & Szostak, 2013; Yeaman & Yount, 2003; Bechinger, 1997; Wimley, 2010). Coacervates lack lipid bilayers but may undergo permeability changes through peptide–polyelectrolyte interactions (Oparin, 1938; Keating, 2012). Mineral compartments, proposed in alkaline vent models, provide confinement and catalytic scaffolds but cannot host peptide bilayer pores (Russell & Martin, 2004).

| Membrane Candidate |

Pore Feasibility |

Requirements |

Key Considerations |

| Fatty acid/oil droplets |

Very low |

No stable bilayer; peptides cannot insert |

Only surface adsorption is possible |

| Micelles |

Very low |

Too small, high curvature; hydrophobic mismatch |

Surface disturbance only; no true pore |

| Vesicles/Liposomes (fatty acid bilayers) |

High |

~15–25 aa amphipathic α-helix; cationic residues; moderate hydrophobicity |

Best candidate; experimental poration shown |

| Coacervates |

Low–Medium |

No bilayer; pore concept irrelevant |

Permeability may change via peptide–polymer binding |

| Mineral compartments |

Indirect |

Solid mineral walls, no lipid bilayer |

Peptide–mineral complexes may enable selective pathways |

Table 5.

Feasibility of β-sheet peptide pore formation across different protocell membrane candidates. Fatty acid bilayers are the most favorable environment for β-sheet oligomers to insert and line a primitive pore with hydrophobic–hydrophilic segregation. Droplets and micelles lack bilayers and are unsuitable (Deamer, 1997; Deamer & Pashley, 1989; Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). Coacervates may experience peptide-induced permeability changes without true pore structures (Oparin, 1938; Keating, 2012). Mineral compartments lack bilayers, though surface adsorption may influence transport (Russell & Martin, 2004). Experimental and theoretical studies show β-sheet oligomers can form disruptive or channel-like assemblies in bilayers (Bechinger, 1997; Wimley, 2010; Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011).

Table 5.

Feasibility of β-sheet peptide pore formation across different protocell membrane candidates. Fatty acid bilayers are the most favorable environment for β-sheet oligomers to insert and line a primitive pore with hydrophobic–hydrophilic segregation. Droplets and micelles lack bilayers and are unsuitable (Deamer, 1997; Deamer & Pashley, 1989; Hargreaves & Deamer, 1978; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). Coacervates may experience peptide-induced permeability changes without true pore structures (Oparin, 1938; Keating, 2012). Mineral compartments lack bilayers, though surface adsorption may influence transport (Russell & Martin, 2004). Experimental and theoretical studies show β-sheet oligomers can form disruptive or channel-like assemblies in bilayers (Bechinger, 1997; Wimley, 2010; Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2011).

| Membrane Candidate |

β-sheet pore feasibility |

Mechanism & Requirements |

| Fatty acid droplets/oil droplets |

Very low |

No bilayer; peptides only adsorb at the surface |

| Micelles |

Very low |

Too small/curved; oligomers cannot assemble stably |

| Vesicles/Liposomes (fatty acid bilayers) |

High |

Best candidate; requires amphipathic β-strands, oligomerization; hydrophobic residues face tails, hydrophilic residues line the channel |

| Coacervates |

Low–medium |

No bilayer; β-sheet aggregates may create “leaky spots” in the polymer matrix |

| Mineral compartments |

Irrelevant |

Solid walls; peptides may adsorb, but cannot form channels |

Table 6.

Environmental influences on the feasibility of peptide pore formation in protocells. Prebiotic environments strongly influenced protocell stability and peptide assembly. Freshwater hot springs with wet–dry cycles promoted condensation and vesicle incorporation, favoring β-sheet oligomerization (Rajamani et al., 2008; Forsythe et al., 2015; Monnard & Deamer, 2002). Ice eutectic brines concentrated solutes and stabilized fragile polymers, enhancing β-sheet aggregation (Kanavarioti et al., 2001; Trinks et al., 2005; Deamer, 1997). Alkaline hydrothermal vents and tidal pools offered conditional opportunities depending on amphiphile mixtures, ionic strength, and stabilizers such as glycerol monoesters or chelators (Russell & Martin, 2004; Mansy & Szostak, 2008; Apel et al., 2002; Burton et al., 2012; Martins et al., 2008). Mineral compartments lacked bilayers and could not host classical peptide pores, though peptide–mineral interactions may have gated transport (Russell & Martin, 2004). Modern studies confirm β-sheet oligomers’ tendency to form disruptive aggregates under these conditions (Bucciantini et al., 2002; Lashuel et al., 2002).

Table 6.