1. Introduction

The pervasive spread of technologies has been accompanied by their persistent miniaturisation in order to configure smaller and less invasive devices. Human Augmentation [

1] is defined as the approach that embraces different technical fields and methodological approaches and uses technologies to enhance human productivity or capacity or that add to the human body or mind.

The research presents the technological evolution that has favoured the design and dissemination of increasingly intelligent and connected devices in industrial contexts, such as smart wearable devices, aimed at increasing operator safety within industrial contexts, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR) devices, capable of modifying and simulating production contexts. In addition, the introduction of innovative interaction models integrated with artificial intelligence systems, Big Data and 5G networks, have fostered connections, dissemination and monitoring of environments. In this scenario, wearable and interactive technologies are the perfect synthesis of the physical and digital worlds integration to enable the augmentation of human capabilities and skills.

These technologies are able to act as an extension of the user through non-invasive and user-friendly gimmicks that allow the user to interact with other intelligent systems and receive augmented information from the hybrid physical-virtual world [

2]. New tools of interaction are configured, devices that can merge with the user's body and require the designer to design solutions that lose their physicality in favour of digital gimmicks that increase the prosthetics integration of technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

The research proposes an analysis of key human-machine interaction technologies, starting with a critical-analytical review of case studies of selected state-of-the-art systems, devices and solutions, with a view to enhancing user capabilities in industry.

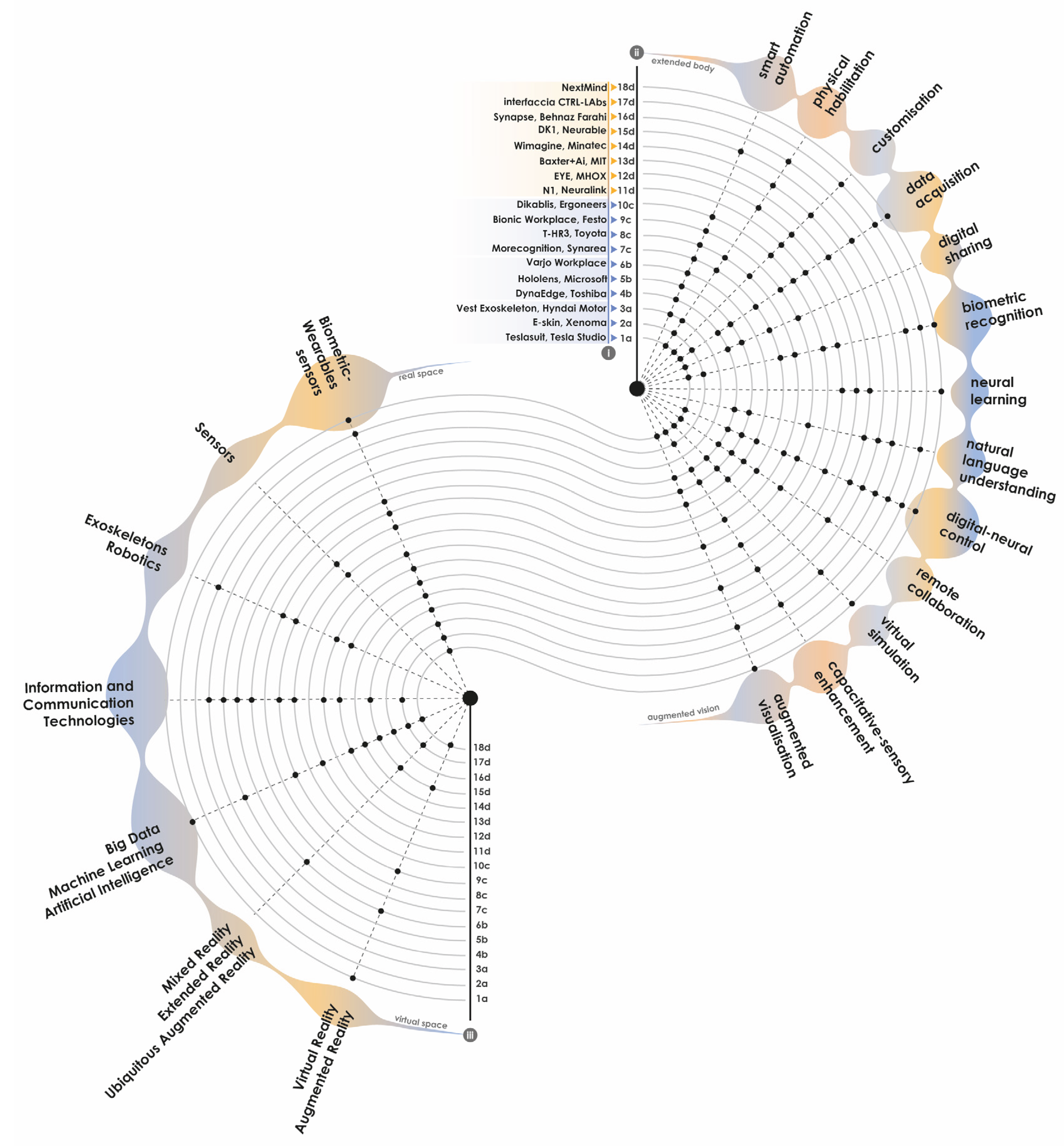

In particular, the reconnaissance performed presents the classification of 18 case studies, proceeding to the analysis of the main digital interactive technologies with (i) physical-directed and cognitive-neural control - starting with the identification of (a) smart clothing; (b) augmented visualisation systems; solutions. For (c) the ‘extension’ of the body; and (d) cognitive control devices - identifying the interaction modes for the augmentation of (ii) physical skills and capabilities and (iii) augmented vision, between (iii) real and virtual space.

3. Multidimensional Interfaces for Physical and Cognitive Perception

ICT-integrated interfaces provide multi-dimensional modes of interaction that can be tactile-visual, speech-aural or mixed systems.

Tools such as biometric, facial and gesture recognition enable biometric tracking and measurements for human-machine interaction; text, image and video recognition enable data interpretation and the creation of associations that can extend analytical tasks and foster new advanced applications for interaction and vision [

3].

Interactive devices equipped with input peripherals allow for text input, either through commonly used tools such as keyboards or through expedients such as voice recognition or optical scanning systems, barcode and QR code or RFID radio scanning systems.

In advanced contexts, instruments for detecting biometric and/or physiological parameters are also used, such as systems for capturing heart rate, respiratory rate or instruments for ECG detection and other related psycho-physiological factors; instruments for analysing blood oxygenation, electromyography or electroencephalography systems and brain-computer interfaces [

4]. Output devices, on the other hand, engage the sensory channels via displays for the visualisation of 2D and 3D images and text or via the reproduction of sounds, which can either have a natural language content or act as sound feedback to support visual communication, reducing visual sensory overload and conveying user attention [

5]. The haptic and tactile restitution of devices integrated by vibrotactile actuators, on the other hand, enable feedback generated by simulating tactile sensations. The Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) characterised the technological paradigm shift associated with the most significant revolutions in modern economic history as telecommunication systems - computers and audio-video technologies - that enable the storage and exchange of information [

6].

Today, ICT associated with emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, support the formation of work processes that are transformed into complex, dynamic and adaptable systems. Such technologies promote the conversion of work activities, transforming repetitive, tiring and dangerous tasks into robot tasks.

In fact, developments in the field of artificial intelligence impose a radical transformation of work, automate and improve processes making them more efficient, enable new forms of collaboration between humans and machines to configure safe working environments [

7]. Such a space is defined by Daugherty & James Wilson [

3] as the “ghost space” of human-machine collaboration where humans serve, for example, to develop, train and manage various intelligent applications while machines help humans to overcome their limitations by providing capabilities such as the ability to process and analyse massive amounts of data in real time, augmenting human capabilities.

Advances in technology have led to the configuration of numerous implants that can be classified as human augmentation devices. Human Augmentation concerns the extension and augmentation of the senses, i.e. the integration and implementation of multisensory information presented to the user through senses. Augmented action is achieved by mapping human actions in virtual, real or remote environments. Augmented human cognition is achieved by sensing the user's cognitive state with tools capable of interpreting and adapting according to the user's current needs or predictive expectations.

Figure 1 shows the schematisation and classification carried out on case studies identified in industry, subdivided into (i) physical-directed and cognitive-neural control systems; the right-hand side shows the main functions starting with the interaction modes for skill enhancement and (ii) physical capabilities and augmented vision; the left-hand side shows the main technologies, starting with the development of (iii) real and virtual space.

4. Results and Discussion

Recent technological developments include wearable computers, exoskeletons and new interfaces integrated with gesture technology, brain-computer interfaces allowing control via brain waves, haptic technology and voice recognition software [

8]. The following survey, divided into four sections, shows the identified case studies by analysing the main features, functionalities and technologies: from (a) smart clothes to (b) augmented visualisation and (c) body ‘extension’ systems, to (d) cognitive control devices. The review highlights the different solutions proposed in different applications and particulary in the industrial sector, for increasing user skills and the proposed technological trend.

4.1. The Multidimensional and Multimodal Dimension of Human-Machine Interaction

Ensuring that the user-operator can easily interact with the complex and connected system that surrounds him or her is tantamount to increasing skills and capabilities in the performance of tasks and amplifying and optimising the modes of communication that interpose with the system. This entails achieving multidimensional and multimodal interaction, capable of supporting the user in the management and control of systems and increasing the user's sensory perceptions and involvement.

The possibilities offered by Wearable Technologies (Wireless Sensing), fully integrated in the new production paradigms of Industry 5.0, will be operational tools for collecting and using huge amounts of data, supporting the management of maintenance, control and supervision activities of the most complex plants and introducing new diagnostic methods at the service of safety operations.

Sophisticated interaction tools will be able to transfer constant input to the user, capable of changing and updating in real time. New wearable devices designed for virtual, augmented and mixed reality will allow immersion in three-dimensional models with which the user establishes an hybrid interaction that conforms to the real one, facilitating the acquisition of information [

9].

The integration of Ubiquitous Computing, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, Extended Reality, Internet of Things and Robotics technologies in the industrial environment introduces the 5.0 dimension with the design of intelligent environments as a scenario of interaction between humans and advanced computational systems.

In Industry 4.0, all the components involved in the production process are provided in a virtual image, i.e. networked as cloud databases - thanks to Information Technology (IT) - that is able to give information about real-world components and status.

The system characterised by components in the physical world, which has a virtual image and is interconnected with other parts of the process is called a Cyber-Physical System (CPS). CPS systems interact with humans via expedients such as senses and/or through the use of new control systems; these include the movement of eyeballs or control via electromagnetic brain signals. Cyber-physical systems are transforming the process of human-machine communication, proposing new interactive modes of advanced enjoyment. Devices such as Virtual Wearables capable of integrating with the user and interacting with them through immaterial and natural interfaces that do not require a controller, but which, thanks to the skilful use of Leap Motion, motion detection and Augmented and Virtual Reality technologies, generate new modes of human-machine interaction.

New levels of safety are achieved to the benefit of maintenance operations, facilitated by the rapid, real-time display of machine status, facilitating remote collaboration and enabling specialists to consult or guide local technicians without space-time constraints. The automotive sector was one of the first to adopt automation technologies such as Machine Vision - or Computer Vision - to perform automatic inspections and analyses based on imaging, process control and robot guidance [

10]. This technology supports the monitoring of the automotive production process through imaging systems including hyperspectral imaging, infrared, line scanning, and 3D surface imaging and X-ray imaging. Cameras and sensors are used in conjunction with interfaces to record or capture images, whereby images of the surface of the automotive component to be inspected are captured and subsequently analysed and processed by specialised software.

This makes it possible to exchange large amounts of data and interact in real time thanks to new generations of sensors - MEMS. The human mind, however, is unable to process such a mass of data and it is therefore necessary to extract useful information from it by means of artificial intelligence systems, developed using tools such as Machine Learning. Recent technological advancements have included the development of products such as HoloLens, augmented reality viewers and wearables designed to be useful at different points in industry's life, as well as experiments in the design of smart clothing, made to integrate with the user like a second, sensoryised, intelligent skin. Such garments will be able to communicate our inner states through intelligent systems that transform the interaction experience.

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), garments were presented that thanks to small chips inside become multifunctional, regulate body temperature, register movements, recognise people, and light up at night. This is not just about trends, but about the possibilities of making humans more efficient through the use of interactive tools. Anouk Wipprecht designs micro-controlled garments with a skilful and sophisticated interdisciplinary mix of robotics, biomimicry, machine learning combined with animatronic technology to give autonomy of movement realised with advanced 3D printing techniques.

A notable project in this context was presented as part of the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) 2018 by Tesla Studios and concerns a (1a) Haptic Suit capable of transferring haptic sensations over the entire body, simulating sensations such as pain, pressure, temperature and strain. Such a smart suit, composed of sensors and featuring VR and AR technologies simulates actions, facilitating the training and education phase of the user through the movement tracking system and the ability to return sensory feedback to the body through electrostimulation.

Japanese smart clothing start-up Xenoma presented a range of smart clothing solutions at CES 2020. The motion-capture, camera-less, (2a) E-skin [

11] garments developed by Xenoma Inc. consist of 14 strain sensors placed on the shirt that monitor the user's body movements such as bending, stretching and twisting of joints to track cardiovascular conditions.

The risk of injury increases significantly when workers perform actions by assuming inappropriate postures, such as frequent twisting and bending or performing repetitive movements. To reduce strain and improve the performance of activities that can cause injury, either in the short or long term, the Hyundai Motor Company developed a wearable (3a) Vest Exoskeleton (VEX) in 2019. The battery-free VEX exoskeleton improves productivity and reduces fatigue for industrial workers by mimicking the movement of human joints to increase load support and mobility.

4.2. The Hybrid Space of Interaction Technologies

Designing interaction by improving the process of accessing content and enhancing the modalities of use enables the exploitation of information potential, the best use of interfaces and the transmission of content to users with the support of devices to explore virtual environments by optimising the relationships between “real space” and “virtual space”. Designed spaces and processes are “experienced” and “acted out” in three-dimensional contexts and spaces to move, share memory and imagine through “actuators” and “simulators”. An example of this trend is the increasing use of “natural user interfaces”, devices that provide interaction with the virtual environment based on body movements, touch, gestures and voice commands [

9].

Technologies such as VR and AR have been adopted by manufacturing companies and integrated not only in the production phases but also to improve digital training and prototyping.

The possibility of “simulate” the behaviour of objects based on digital models before producing them in the real world is widespread: objects, simulated vehicles will return huge amounts of data that can perform “predictive” maintenance and provide feedback to improve design [

12].

Smart Glassaidation's (4b) DynaEdge DE-100 [

13], are glasses in which augmented reality technology, display and camera are integrated and where human perception is enhanced by the ability to receive necessary information in real time and simultaneously transmit their activity to other remotely connected operators who will be able to provide assistance and training thanks to the instantaneous transmission of data on the device.

HoloLens offers mixed reality experience by providing the reliability, security and scalability of Microsoft's cloud and artificial intelligence services. With this device, it is possible to view multiple holograms at the same time through the ergonomic field of view as it is equipped with the self-adjusting system that allows users to change activities or exit mixed reality by simply lifting the visor.

With the (5b) Dynamics 365 Hololens [

14] system you can touch, grasp and move the holograms that will respond similarly to real objects; by integrating Wi-Fi, intelligent microphones and natural language voice processing, voice commands work even in noisy industrial environments.

With remote function systems and hands-free video calls, you can share what you see in real time with remote experts.

Integrating state-of-the-art interfaces increases efficiency levels, operators benefit from receiving physical feedback from haptic technologies, wearable devices or tools such as AR glasses [

15] that enable hands-free working and ensure greater concentration on the task at hand. The use of virtual, augmented or mixed reality allows full or partial immersion of the user, adding information to the scene in which they are placed.

Technologies such as virtual reality enable constant communication between individuals located in different space-time contexts. In such environments, the user perceives the presence of other users, and the perception of the environment is mediated by automatic and controlled mental processes.

To support the hybrid world, new concepts of “reality” have been defined over the years. Extended Reality (XR) refers to immersive technologies - such as augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) and mixed reality (MR) from real and virtual environments to technology-generated human-machine interactions and wearables that amplify reality by merging virtual and

real spaces and creating a fully immersive experience [

16].

With augmented reality, thanks to the use of AR glasses or screens, tablets and smartphones, it is possible to access information and virtual objects that are superimposed on the real world, enriched with digital details. Augmented reality allows for a cognitive connection between the subject, who is not isolated from the real world, and the context with which he or she can interact, thus promoting a shared experience.

In contrast, with virtual reality, users wear VR visors, or displays integrated by tools such as data gloves, and are immersed in a simulated digital environment and removed from reality that is artificially replaced. Mixed reality [

17], represents simulation technologies, including augmented reality and augmented virtuality, capable of creating a continuum between the real and virtual worlds. In this mixed reality - or hybrid reality - digital and real-world objects coexist and can interact with each other in real time.

For this condition, the user needs tools with superior processing power, such as MR headsets. Virtual reality technology allows the real world to be enriched with different computer-simulated environments or objects and represents an entirely computer-generated world that the user perceives as such and can interact with in real time. Augmented reality enriches the real world with computer-generated information, while mixed reality describes the entire continuum between the real and virtual worlds [

18]. Ubiquitous Augmented Reality (UAR) is a human-computer interaction technology, born from the convergence of augmented reality and ubiquitous computing. With this technology, visualisations can implement the real world with digital information [

19].

The (6b) Varjo Workspace [

20], by Varjo Tech HQ, is the first dimensional interface that allows users to go beyond physical monitors and work in a space where 2D applications merge with 3D experiences.

Varjo's goal is to establish a revolution in immersive computing, through the XR-1 Developer Edition photorealistic mixed reality headset and Varjo Workspace, complemented by Virtual reality (VR)/ Extended Reality (XR) hardware, software and user interfaces that break free from the constraints of the physical world. Varjo allows existing 3D creation tools to be brought into an immersive photorealistic 3D environment with customisable virtual monitors. This offers a new perspective by reducing the friction of VR visualisation that becomes part of the normal design process. It’s possible to modify a 3D model using existing CAD and visualisation tools; to move 3D models and visualise them in real time via virtual content projected into the real world. Interactive Simulation, Volvo, Flight Safety and CAE are already introducing a paradigm shift in the simulation and training space, combining the real and virtual in completely new ways. Varjo XR-1 headsets are already being used in simulators, car development sites and training facilities.

4.3. Technologies as an Extension of the Body

New tools and human-machine interaction models that change the user-operator experience were analysed, to manage and govern processes dynamically and flexibly, optimising work operations through an amplified and advanced interactive language.

The process of industrial virtualisation has led to an increase in the use of everyday devices projected into industrial contexts.

In fact, Samsung has initiated a digitisation process within the factories, integrating connected devices such as smartwatches, smartphones or tablets, capable of accompanying the operator in his activities. These devices allow the user to send alerts to managers, when necessary, display information needed to carry out work, inform them on activities carried out and monitor production progress, increasing efficiency and improving data flows.

In 2017, the company synArea Consultans srl, IIT and Morecognition srl developed (7c) More Device, a wearable sensor on different body districts that allows information to be recorded and transmitted via wireless communication. Through this modular and integrated system, it is possible to manage 3D Learning Units on different operating systems and devices such as PCs, tablets, smartphones and immersive viewers. With the use of the device, the operator, that is immersed in a Virtual Factory, receives the information in real time and is able to interact with each machine, computer and robot with a simple arm movement [

21].

The Toyota Motor Corporation's (8c) T-HR3 [

22] is developed to explore how technology supports the mobility of humans. This system represents an evolution of previous generations of humanoid robots and is aimed at testing the positioning of joints and pre-programmed movements. The new platform offers functionalities that can assist the user in different environments, guaranteeing complete freedom of movement. The robot is, in fact, equipped with joints capable of replicating the movements performed by the user. The integrated Self-interference Prevention technology ensures maximum correspondence between the movements of the operator and the robot. The motors, gearboxes and torque sensors mounted on the T-HR3 and the Master Maneuvering System are connected to the users' joints and communicate movements directly to the 29 parts that make up the robot's body and to the 16 control systems of the Master Maneuvering System to ensure synchronised movements.

The model presented by the company Festo, proposes a new working environment of human-robot collaboration, where connection and safety guarantee new ways of working. The workstation (9c) BionicWorkplace [

23] by Festo S.p.A. is ergonomically designed and all elements, right down to the lighting, can be configured, customised and adapted to suit the user. In the centre of the worker's field of vision is a large projection screen that provides the worker with all relevant information, dynamically displaying content according to the task at hand. Around the projection screen are mounted sensors and camera systems that constantly record the positions of the worker, components and tools. In this way, the user can interact directly with the BionicCobot and control it using movement, touch or voice command. The system recognises workers and their movements through their special work clothes. Thanks to the introduction of intelligent learning workplaces and the use of multifunctional tools, collaboration between man and machine will be even more intuitive, simple and efficient in the future.

Dating back to the 1800s, the first clinical studies of the mechanisms of human vision through the observation of eye movements - recording pupil contraction and dilation - known as eye-tracking technology. This technology uses the process of measuring the fixation point of the eye or the motion of the eye relative to the head to measure eye position and movement. Through these non-invasive tests, the effectiveness and efficiency of the interface design can be assessed, making interactive devices suitable for human cognitive characteristics. In fact, it is possible to trace the user experience with millimetre precision and thus assess the characterising elements of the interactive system such as usability and the emotional dimension [

24].

Ergoneers GmbH, a spin-off from the Faculty of Ergonomics at the Technical University of Munich, thanks to its studies in the application areas of transport, from automotive to market research, usability and biomechanics for development, produces and distributes measurement and analysis systems for behavioural research and optimisation of human-machine interaction. The (10c) Dikablis glasses [

25] developed by Ergoneers GmbH combine binocular eye detection with high measurement accuracy and standardised calculation of parameters for synchronous measurement of gaze data from various subjects in real time. The ergonomic configuration ensures wearability and minimises visual obscuration, designed to fit different head sizes and to be combined with prescription glasses.

4.4. Mind and Body Connection Systems

According to De Fusco [

26], a more advanced technology corresponds to a smaller device form. New interaction technologies, such as cognitive interaction systems, are an example of technology advancing in favour of a rapid dematerialisation that will allow a real

physiological intrusion of technology into the living being [

27]. The brain-machine interface originated as a tool for capturing human thoughts, emotions and other emotional states. Today, this information allows the user to control, with little mental effort, machines that respond and adapt to needs [

28]. BMI becomes a tool for direct communication between human cognitive thinking and digital devices that surround it.

In recent decades, research in areas such as neuroscience has enabled scientists to understand the ways in which individuals make decisions much more precisely [

29].

Technology will be increasingly integrated into everyday life, but the perception of it is bound to shrink to the point where the physical presence of the device is completely absent. In fact, there are many techniques for measuring brain signals, and these can be classified into invasive, semi-invasive and non-invasive techniques [

30].

In 2019, Elon Musk and technology startup Neuralink unveiled plans for implants that connect the human brain with computer interfaces using artificial intelligence. This implant detects and records electrical signals in the brain and transmits this information to the outside of the body - potential to create a scalable high-bandwidth brain-machine interface (BMI) system, meaning it connects the brain to an external device to form a brain-machine interface. This would allow users with disabilities to control devices such as phones or computers. The implant may be useful as a means of enhancing the brain, enabling a human-artificial intelligence (AI) symbiosis, leading to what Musk calls ‘superhuman intelligence’. The (11d) N1 [

31] sensor by Neuralink Corp. - implanted inside the skull - has tiny wires smaller in diameter than a human hair and can intercept neural activity.

Recent developments in biohacking and 3D bioprinting will enable the printing of organic and functional body components in the near future, enabling humans to replace damaged districts or increase their bodily potential

MHOXdesign's EYE (Enhance your eye) (12d) prototype [

32] is based on the idea of extending the sense of sight by integrating the functions of the eye with others currently managed by different parts of the body or external devices. The EYE HEAL device is able to replace standard eye functions for those with visual impairment due to disease and/or trauma. EYE ENHANCE enhances visual capabilities by up to 15/10, thanks to its hyper-retina and by ingesting special pills it is possible to activate visual signal filters. The device allows visual experience to be recorded and shared and is supported by wi-fi communication for connection with external devices.

In the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory in 2018, the humanoid robot (13d) Baxter was tested with the control system through human thought. Baxter, a humanoid robot designed by Rethink Robotics, is connected to the user via electrodes placed on the user's head and arms. The aim is for the machine to adapt to human communication, and not vice versa. In addition to detecting brain signals, the system can distinguish signal variations that may occur when a human perceives that he has made a mistake.

The system involves the monitoring of the user whose task is to supervise the robot's work. When the person realises that the robot is making a mistake, the signal produced by his brain interrupts the robot's action. The human then produces a hand gesture that indicates to the robot the correct operation, this step takes advantage of the monitoring of muscle activity.

Thanks to the use of Brain Computer Interface (BCI) technology, it was possible to configure an exoskeleton that, with an implant that records cortical signals, offers people with motor disabilities the possibility of using their lower limbs. The (14d) WIMAGINE medical device, developed at the MINATEC [

33] research centre, is a minimally invasive device that can be implanted in the skull thanks to a series of electrodes placed in contact with the dura mater. The system records signals from the motor cortex and decodes them to guide the movements of the exoskeleton.

The (15d) DK1 device [

34] designed in 2019 by Neurable Inc. consists of brain sensors that detect electrical brain signals using non-invasive electroencephalography (EEG) techniques and provides software tools to interpret those signals for use in various applications such as virtual reality. The software uses machine learning to measure and classify EEG signals in real time. The NeuroSelect SDK controls VR, AR and XR environments and enables natural and intuitive user interactions by translating control signals from the brain into human intent. The software provides tools to measure the effectiveness of VR simulation training for industrial and military applications.

Behnaz Farahi's (16d) Synapse helmet [

35] is a 3D-printed multi-material wearable device that moves and changes shape in response to brain activity. The project seeks to explore the direct control of movement with neural commands in order to effectively control the environment that becomes an extension of the body. The movement of the helmet, integrated with Neurosky's EEG chip and Mindflex headphones, is controlled by electroencephalography of the brain.

The transformative neural interface project proposed by CTRL Labs intersects research and challenges between computational neuroscience, statistics, machine learning, biophysics, hardware and human-computer interaction. CTRL labs are building the first non-invasive interface [

36] that connects the human nervous system and computers to configure a new Extended Reality. The interface is able to decode the electrical activity of motor neurons as they are activated and feed these signals into a machine learning network to virtualise the actions performed. The virtual image displayed on the computer varies with the potential actions performed by the nerves in the arm without moving them; if there are physical limitations, (17d) CTRL will act with virtual and remote control based on brain power. (18d) NextMind [

37] from Snap Inc., unveiled at CES 2020, is the world's first brain sensing device that enables simultaneous control of augmented reality or virtual reality viewers. The device sits on the back of the head and attaches to any AR/VR device, allowing interaction with virtual environments directly with brain control. NextMind has a control system that captures neurophysiological signals and transforms them into data to create real-time neuro-control capabilities. The device incorporates artificial intelligence-based technologies that decode the user's intention and translate neural signals into digital commands, transmitted via Bluetooth technology. NextMind is made of a conductive elastomeric polymer to achieve dry electrodes capable of measuring high-quality brain signals without compromising user comfort.

Despite the rapid development of brain-machine interaction interfaces, the problems of Human-Factor/Ergonomics as usability, interface design, performance modelling and individual differences remain, but have not yet been adequately addressed [

38].

5. Conclusions

Developments in the field of artificial intelligence have led to the transformation of work activities, automating and improving processes by making them more efficient, enabling new forms of collaboration between humans and machines.

The evolution of industrial contexts has favoured the design and deployment of smart and connected devices, including, smart wearable devices, aimed at increasing operator safety within industrial contexts, virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) devices, capable of modifying and simulating production contexts.

The survey shows the case studies identified, schematised and classified into (i) physical-directed and cognitive-neural control systems: (a) smart clothing; (b) augmented visualisation systems; (c) the ‘extension’ of the body; and (d) cognitive control devices. It highlights different solutions, particularly in the industrial sector, starting with the interaction modalities for the enhancement of (ii) physical skills and augmented vision and in relation to the technological evolution between (iii) real and virtual space.

The real frontier of integration between the real and the virtual will consist in breaking down the barrier with physical reality and with the ambition to recover the sensory and bodily dimension as well.

Thanks to nanotechnologies and bionics, it will be possible to define new abilities for the

augmented man through a process that will digitise man through artificial visions, exoskeletons, perceptive augmentation and monitoring of physiological parameters [

39,

40]. This human-machine, body and technology hybridisation defines – through the human-centred approach – new design paradigms for defining safe and interconnected working environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G. and E.L.; methodology, S.C. and M.B.; validation, S.C., V.F.M.M. and M.B..; writing—original draft preparation and results, G.G.; writing—introduction, second paragraph and conclusion, G.G., E.L., S.C., V.F.M.M. and M.B.; writing— third paragraph G.G. and E.L.; writing— fourth paragraph G.G.; supervision, S.C. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Next Generation EU PRIN 2022 - PNRR project title “Neural Wearable Device for Augmented Interconnection in Manufacturing Safety” - MUR: P2022RPYR3 – CUP B53D23027190001 – Missione 4 “Istruzione e ricerca” Componente 2 “Dalla ricerca all’impresa” – investimento 1.1 Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale del Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Alicea, B. An integrative introduction to human augmentation science. arXiv preprint 2018 arXiv:1804.10521.

- Raisamo, R.; Rakkolainen, I.; Majaranta, P.; Salminen, K.; Rantala, J.; Farooq, A. Human augmentation: Past, present and future. International. Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 2019, 131, 131–143.

- Daugherty, P. R.; James Wilson. H. Human + Machine: Reimagining Work in the Age of AI. Harvard Business Review Press 2018.

- Gedam, S., & Paul, S. A Review on Mental Stress Detection Using Wearable Sensors and Machine Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 84045–84066.

- De Fazio, R., Mastronardi, V., Petruzzi, M., De Vittorio, M., & Visconti, P. Human-Machine Interaction through Advanced Haptic Sensors: A Piezoelectric Sensory Glove with Edge Machine Learning for Gesture and Object Recognition. Future Internet 2022, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi15010014.

- Gibson, J. J. The senses considered as perceptual systems 1966.

- Breque, M., De Nul, L., & Petridis, A. (2021). Industry 5.0: towards a sustainable, human-centric and resilient European industry. European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation.

- Su, H., Qi, W., Chen, J., Yang, C., Sandoval, J., & Laribi, M. A. Recent advancements in multimodal human-robot interaction. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2023, 17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbot.2023.1084000.

- Capece, S.; Giugliano, G. Communication and interaction models for the cultural heritage, in Ciro Picci√≤li, Luigi Campanella (a cura) di Diagnosis for the Conservation and Valorization of Cultural Heritage. Naples, Italy 13-14 december 2018. pp. 215–226, ISBN: 9788895609423.

- Javaid, M., Haleem, A., Singh, R. P., Rab, S., & Suman, R. Exploring impact and features of machine vision for progressive industry 4.0 culture. Sensors International 2021, 3, 100132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2021.100132.

- E-Skin HEALTHCARE. (n.d.). Xenoma Inc. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://xenoma.com/en/eskin/.

- Beltrametti, L., Guarnacci, N., Intini, N., & La Forgia, C. La fabbrica connessa. La manifattura italiana (attra) verso Industria 4.0. goWare & Edizioni Guerini e Associati 2017.

- DYNAEDGE: DynaEdge (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://us.dynabook.com/.

- HOLOLENS: Microsoft HoloLens (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.microsoft.com/it-it/hololens.

- Kim, H., Kwon, Y., Lim, H., Kim, J., Kim, Y., & Yeo, W. Recent advances in wearable sensors and integrated functional devices for virtual and augmented reality applications. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 31. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202005692.

- Sridhar, G. S. Introduction to XR, VR, AR, and MR. G. S. Sridhar Editor 2018.

- Milgram, P.; Takemura,H.; Utsumi, A.; Kishino, F. Augmented reality: a class of displays on the reality- virtuality continuum, presented at Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies. SPIE. IEEE NCC., 1994. Boston, MA, USA.

- Flaspöler, E., Hauke, A., Pappachan, P., & Reinert, D. Literature Review The Human-Machine Interface As An Emerging Risk. 2006 Eu-Osha-European Agency for Safety and Health at Work.

- Sandor, C., & Klinker, G. Lessons Learned in Designing Ubiquitous Augmented Reality User Interfaces, in Haller, M. (Ed.) Emerging technologies of augmented reality: Interfaces and design. Igi Global.

- VARJO: Varjo Technologies. Retrieved November 13 2024, 2024, from https://varjo.com/.

- Favetto, A., Ariano, P., Celadon, N., Coppo, G., Ferrero, G., Paleari, M., Zambon, D., Tecnologie touchless per la Fabbrica 4.0, 2018. https://www.affidabilita.eu/RepositoryimmaginiEventi/AetCms/file/rassegna_stampa/AssemblaggioEmeccatronica_gen2018.pdf.

- T-HR3: Toyota unveils third generation humanoid robot T-HR3. (n.d.). Toyota Motor Corporation. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://global.toyota/en/detail/19666346.

- Bionic Workplace. (n.d.). Festo. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://www.festo.com/it/it/.

- Biondi, E., Rognoli, V., & Levi, M. (2009). Le neuroscienze per il design: la dimensione emotiva del progetto. Franco Angeli.

- DIKABLIS: Dikablis (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://ergoneers.com/.

- De Fusco, R. (2007). Made in Italy. Storia del design italiano. Gius. Laterza & Figli.

- Forino, I. (2007). Il design percepibile, in R. De Fusco (a cura di) "Storia del Design", Gius. Laterza & Figli.

- Jebari, K. Brain machine interface and human enhancement-an ethical review. Neuroethics 2013, 6, 617–625.

- Harari, Y. N., & Piani, M. (2018). 21 lezioni per il XXI secolo. Bompiani.

- Prapas, G.; Angelidis, P.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Bibi, S.; Tsipouras, M.G. Connecting the Brain with Augmented Reality: A Systematic Review of BCI-AR Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9855. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14219855.

- N1. (n.d.). Neuralink. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://neuralink.com/.

- EYE: MHOX EYE. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from http://mhoxdesign.com/eye-en.html.

- Minatec: MINATEC. (n.d.). MINATEC. Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.minatec.org/en/.

- DK1: Neurable (n.d.) Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.neurable.com/.

- SYNAPSE: Synapse, Behnaz Farahi. Retrieved November 13 2015, 2024, from https://behnazfarahi.com/synapse/.

- CTRL Labs: CTRL-LAbs (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from http://ctrl-labs.com/.

- NEXTMIND: NextMind. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://ar.snap.com/welcome-nextmind.

- Nam, C. S., Moore, M., Choi, I., & Li, Y. Designing Better, Cost-Effective Brain-Computer Interfaces. Ergonomics in Design the Quarterly of Human Factors Applications 2015, 23, 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1064804615572625.

- ORIZZONTE - LA TECNOLOGIA, A. Granelli. 2016.

- Romero, D., Stahre, J., Wuest, T., Noran, O., Bernus, P., Fast-Berglund, √Ö., & Gorecky, D. (2016, October). Towards an operator 4.0 typology: a human-centric perspective on the fourth industrial revolution technologies. In proceedings of the international conference on computers and industrial engineering (CIE46), Tianjin, China (pp. 29–31).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).