Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

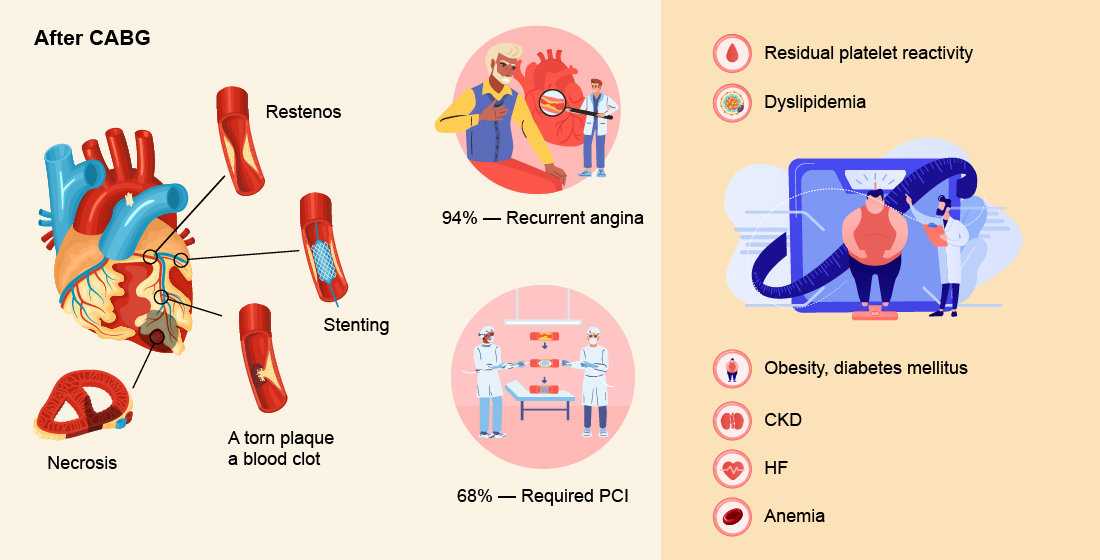

1. Introduction

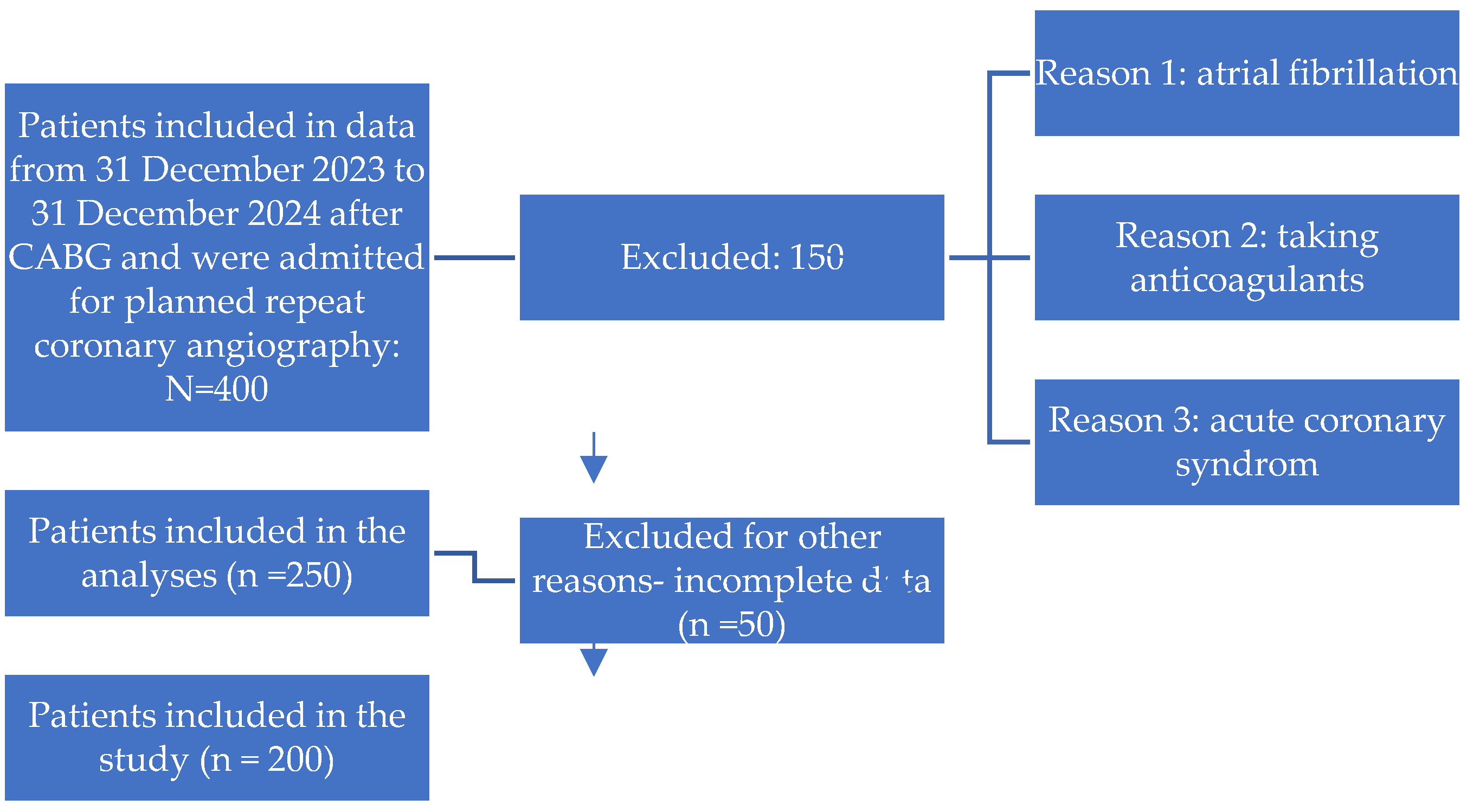

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

Patient Population

Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

Residual Platelet Reactivity Assessment

Clinical and Laboratory Data Collection

Ethical Considerations

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Comorbidities and Medical History

Biochemical and Hematological Parameters

Platelet Reactivity

Echocardiographic Findings

Coronary Angiographic Findings

Medical Therapy

Symptoms and Outcomes

Summary of Key Findings

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Angiographic Findings

Platelet Reactivity and Clinical Outcomes

Medical Therapy

Summary of Findings

DISCUSSION

LIMITATIONS

CONCLUSIONS

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | Acute coronary syndrome |

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CA | Circumflex artery |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| CHD | Coronary heart disease |

| CHF | Congestive heart failure |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular diseases |

| DB | Diagonal branch |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| EDD | End-diastolic dimension |

| EDV | End-diastolic volume |

| EF | Election fravtion |

| ESD | End-systolic dimension |

| ESV | End-systolic volume |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| HRPR | High residual platelet reactivity |

| IA | Intermediate artery |

| IHD | Ischemic heart disease |

| IVS | Intraventricular septum |

| LA | Left atrium |

| LAD | Left anterior descending |

| LCA | Left coronary artery |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LV | Left ventricular |

| LVPW | Left ventricular posterior wall |

| МАСЕ | Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events |

| OMB | Obtuse marginal branch |

| PIVB | Posterior interventricular branch |

| RCA | Right coronary artery |

| RPR | Residual platelet reactivity |

| RV | Right ventricular |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| sPAP | Systolic pulmonary artery pressure |

| SV | Stroke volume |

| TG | Tryglicerides |

| MV | Mitral Valve |

| TV | Tricuspid Valve |

| AV | Aortic Valve |

| AH | Arterial Hypertension |

| TSH | thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| USD BCA | Ultrasound of Brachiocephalic Arteries |

References

- Mangiacapra, F., De Bruyne, B., Muller, O., Trana, C., Ntalianis, A., Bartunek, J., Heyndrickx, G., Di Sciascio, G., Wijns, W., & Barbato, E. (2010). High residual platelet reactivity after clopidogrel: extent of coronary atherosclerosis and periprocedural myocardial infarction in patients with stable angina undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions, 3(1), 35–40. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Gong, B., Wang, W., Xu, K., Wang, K., & Song, G. (2024). Association between haemoglobin, albumin, lymphocytes, and platelets and mortality in patients with heart failure. ESC heart failure, 11(2), 1051–1060. [CrossRef]

- Franchi, F., Rollini, F., & Angiolillo, D. J. (2015). Defining the link between chronic kidney disease, high platelet reactivity, and clinical outcomes in clopidogrel-treated patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. Cardiovascular interventions, 8(6), e002760. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R., Kirtane, A. J., Liu, Y., Crowley, A., Witzenbichler, B., Rinaldi, M. J., Metzger, D. C., Weisz, G., Stuckey, T. D., Brodie, B. R., Mehran, R., Ben-Yehuda, O., & Stone, G. W. (2019). Impact of Smoking on Platelet Reactivity and Clinical Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Findings From the ADAPT-DES Study. Circulation. Cardiovascular interventions, 12(11), e007982. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Ashraf, M. Z., & Podrez, E. A. (2010). Scavenger receptor BI modulates platelet reactivity and thrombosis in dyslipidemia. Blood, 116(11), 1932–1941. [CrossRef]

- Chirumamilla, A. P., Maehara, A., Mintz, G. S., Mehran, R., Kanwal, S., Weisz, G., Hassanin, A., Hakim, D., Guo, N., Baber, U., Pyo, R., Moses, J. W., Fahy, M., Kovacic, J. C., & Dangas, G. D. (2012). High platelet reactivity on clopidogrel therapy correlates with increased coronary atherosclerosis and calcification: a volumetric intravascular ultrasound study. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging, 5(5), 540–549. [CrossRef]

- Toma, C., Zahr, F., Moguilanski, D., Grate, S., Semaan, R. W., Lemieux, N., Lee, J. S., Cortese-Hassett, A., Mulukutla, S., Rao, S. V., & Marroquin, O. C. (2012). Impact of anemia on platelet response to clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary stenting. The American journal of cardiology, 109(8), 1148–1153. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Chen, Y., Liu, Y., Yu, L., Zheng, J., & Sun, Y. (2021). Impact of renal function on residual platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with clopidogrel. Clinical cardiology, 44(6), 789–796. [CrossRef]

- Dracoulakis, M. D. A., Gurbel, P., Cattaneo, M., Martins, H. S., Nicolau, J. C., & Kalil Filho, R. (2019). High Residual Platelet Reactivity during Aspirin Therapy in Patients with Non-St Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome: Comparison Between Initial and Late Phases. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia, 113(3), 357–363. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., Eichelberger, B., Kopp, C. W., Panzer, S., & Gremmel, T. (2021). Residual platelet reactivity in low-dose aspirin-treated patients with class 1 obesity. Vascular pharmacology, 136, 106819. [CrossRef]

- Hertfelder, H. J., Bös, M., Weber, D., Winkler, K., Hanfland, P., & Preusse, C. J. (2005). Perioperative monitoring of primary and secondary hemostasis in coronary artery bypass grafting. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis, 31(4), 426–440. [CrossRef]

- Jiabing Wang, Xingliang Shi, Liuqing Chen, Ting Li, Chenttao Wu, and Mingwu Hu. Platelet Reactivity with MACE in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients Post-PCI under Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: A Meta-Analysis. British Journal of Hospital Medicine 2024 85:10, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Nurmukhammad, F.N., Zhangelova, Sh.B., Кapsultanova, D.A., Musagaliyeva, A.T., Danyarova, L.B., Rustamova, F.E,, Sugraliyev, A.B., Ospanova, G.E. Non-statin therapy in patients with elevated LDL-C and high platelet reactivity: a narrative review. Med J Malaysia. 2025 Mar;80(2):258-265. PMID: 40145170.

- Snoep, J. D., Roest, M., Barendrecht, A. D., De Groot, P. G., Rosendaal, F. R., & Van Der Bom, J. G. (2010). High platelet reactivity is associated with myocardial infarction in premenopausal women: a population-based case-control study. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH, 8(5), 906–913. [CrossRef]

- Franchi, F., Rollini, F., & Angiolillo, D. J. (2015). Defining the link between chronic kidney disease, high platelet reactivity, and clinical outcomes in clopidogrel-treated patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. Cardiovascular interventions, 8(6), e002760. [CrossRef]

- François Mach, Konstantinos C Koskinas, Jeanine E Roeters van Lennep, Lale Tokgözoğlu, Lina Badimon, Colin Baigent, Marianne Benn, Christoph J Binder, Alberico L Catapano, Guy G De Backer, Victoria Delgado, Natalia Fabin, Brian A Ference, Ian M Graham, Ulf Landmesser, Ulrich Laufs, Borislava Mihaylova, Børge Grønne Nordestgaard, Dimitrios J Richter, Marc S Sabatine, ESC/EAS Scientific Document Group , 2025 Focused Update of the 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Developed by the task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS), European Heart Journal, 2025; ehaf190. [CrossRef]

| Without re-stenting |

With re-stenting |

p-value | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=59 | N=136 | |||

| Age | 66.0 [61.5;73.0] | 71.0 [65.8;75.0] | 0.016 | 195 |

| Gender: | 0.431 | 195 | ||

| female | 13 (22.0%) | 39 (28.7%) | ||

| male | 46 (78.0%) | 97 (71.3%) | ||

| Smoking: | 0.001 | 195 | ||

| No | 27 (45.8%) | 97 (71.3%) | ||

| Yes | 32 (54.2%) | 39 (28.7%) | ||

| Alcohol: | 0.164 | 195 | ||

| No | 56 (94.9%) | 134 (98.5%) | ||

| Yes | 3 (5.08%) | 2 (1.47%) | ||

| Weight | 79.0 [70.0;86.5] | 78.5 [70.0;85.8] | 0.903 | 195 |

| Height | 170 [164;174] | 168 [162;173] | 0.438 | 195 |

| BMI | 27.3 [24.9;29.4] | 27.6 [25.0;30.2] | 0.411 | 195 |

| Heredity: | 0.874 | 195 | ||

| No | 37 (62.7%) | 82 (60.3%) | ||

| Yes | 22 (37.3%) | 54 (39.7%) | ||

| Dyspnea: | 0.776 | 194 | ||

| No | 5 (8.47%) | 10 (7.41%) | ||

| Yes | 54 (91.5%) | 125 (92.6%) | ||

| Edema: | 0.190 | 195 | ||

| No | 55 (93.2%) | 116 (85.3%) | ||

| Yes | 4 (6.78%) | 20 (14.7%) | ||

| Pain: | 0.726 | 195 | ||

| No | 2 (3.39%) | 7 (5.15%) | ||

| Yes | 57 (96.6%) ? | 129 (94.9%) | ||

| Weakness: | 0.104 | 195 | ||

| No | 0 (0.00%) | 7 (5.15%) | ||

| Yes | 59 (100%) | 129 (94.9%) | ||

| Heartbeat: | 0.451 | 195 | ||

| No | 53 (89.8%) | 115 (84.6%) | ||

| Yes | 6 (10.2%) | 21 (15.4%) | ||

| Short of breath: | 0.961 | 195 | ||

| No | 43 (72.9%) | 97 (71.3%) | ||

| Yes | 16 (27.1%) | 39 (28.7%) | ||

| SBP | 120 [110;130] | 130 [120;140] | 0.041 | 195 |

| DBP | 80.0 [70.0;80.0] | 80.0 [70.0;80.0] | 0.201 | 195 |

| History of myocardial infarction: | 0.145 | 195 | ||

| No | 33 (55.9%) | 59 (43.4%) | ||

| Yes | 26 (44.1%) | 77 (56.6%) | ||

| АH: | 0.133 | 195 | ||

| No | 5 (8.47%) | 4 (2.94%) | ||

| Yes | 54 (91.5%) | 132 (97.1%) | ||

| DM type 2: | 0.603 | 195 | ||

| No | 42 (71.2%) | 90 (66.2%) | ||

| Yes | 17 (28.8%) | 46 (33.8%) | ||

| History of Stroke: | 0.400 | 195 | ||

| No | 56 (94.9%) | 123 (90.4%) | ||

| Yes | 3 (5.08%) | 13 (9.56%) | ||

| CKD: | 0.068 | 195 | ||

| No | 39 (66.1%) | 69 (50.7%) | ||

| Yes | 20 (33.9%) | 67 (49.3%) | ||

| Stenting: | 0.712 | 195 | ||

| No | 47 (79.7%) | 113 (83.1%) | ||

| Yes | 12 (20.3%) | 23 (16.9%) | ||

| CABG: | 0.003 | 195 | ||

| No | 10 (16.9%) | 5 (3.68%) | ||

| Yes | 49 (83.1%) | 131 (96.3%) | ||

| IHD, duration | 3.00 [1.00;6.50] | 2.50 [1.00;10.0] | 0.364 | 195 |

| Hemoglobin | 142 [132;154] | 145 [135;155] | 0.542 | 195 |

| СRP | 2.00 [1.24;3.56] | 2.45 [1.03;4.22] | 0.487 | 195 |

| Glucose | 5.54 [5.12;6.30] | 5.80 [5.16;6.93] | 0.293 | 195 |

| HbA1c | 6.01 [5.30;6.70] | 6.05 [5.40;7.33] | 0.403 | 195 |

| Creatinine | 80.4 [70.6;90.2] | 79.0 [70.8;92.2] | 0.952 | 195 |

| GFR | 88.0 [75.8;96.0] | 81.0 [69.8;94.2] | 0.279 | 195 |

| Potassium | 4.40 [4.20;4.60] | 4.30 [4.10;4.60] | 0.590 | 195 |

| Sodium | 142 [140;144] | 142 [141;144] | 0.268 | 195 |

| ALT | 19.0 [14.1;28.5] | 18.1 [12.9;25.7] | 0.453 | 195 |

| AST | 17.3 [13.8;25.9] | 17.9 [14.9;23.1] | 0.977 | 195 |

| TC | 4.24 [3.41;5.25] | 4.50 [3.70;5.22] | 0.419 | 195 |

| LDL | 2.58 [2.00;3.17] | 2.42 [2.00;3.20] | 0.569 | 195 |

| HDL | 1.00 [0.99;1.00] | 1.00 [0.96;1.03] | 0.809 | 195 |

| ТG | 1.50 [1.00;1.98] | 1.29 [1.00;1.75] | 0.083 | 195 |

| Troponin I | 20.0 [13.4;95.4] | 14.3 [10.3;32.8] | 0.002 | 195 |

| TSH | 2.00 [1.47;2.90] | 2.00 [1.39;3.15] | 0.773 | 195 |

| Thyroxine | 14.1 [12.0;16.0] | 14.0 [11.6;16.2] | 0.945 | 193 |

| PTI | 94.9 [80.3;103] | 95.8 [77.5;105] | 0.627 | 195 |

| INR | 1.07 [1.04;1.17] | 1.04 [0.99;1.14] | 0.039 | 195 |

| APTT | 31.1 [28.8;36.5] | 31.6 [28.7;35.7] | 0.737 | 195 |

| EDV | 162 [129;206] | 136 [113;179] | 0.038 | 195 |

| ESV | 80.0 [45.5;116] | 61.5 [45.8;95.2] | 0.222 | 195 |

| SV | 78.0 [69.5;87.5] | 77.5 [59.8;92.2] | 0.466 | 195 |

| sPAP | 32.0 [23.0;44.0] | 35.0 [24.5;42.0] | 0.917 | 194 |

| EF | 47.0 [41.5;59.0] | 52.0 [44.0;59.2] | 0.235 | 195 |

| LA | 3.80 [3.60;4.55] | 3.90 [3.50;4.40] | 0.638 | 195 |

| EDD | 5.70 [5.20;6.30] | 5.30 [4.97;6.00] | 0.081 | 195 |

| ESD | 4.20 [3.35;4.90] | 3.80 [3.30;4.60] | 0.240 | 195 |

| LVPW | 1.05 [0.90;1.20] | 1.10 [1.00;1.20] | 0.030 | 195 |

| IVS | 1.10 [0.95;1.27] | 1.10 [1.00;1.30] | 0.924 | 195 |

| МV: | 0.858 | 195 | ||

| No | 4 (6.78%) | 13 (9.56%) | ||

| 1 degree. | 36 (61.0%) | 75 (55.1%) | ||

| 2 degree. | 13 (22.0%) | 36 (26.5%) | ||

| 3 degree. | 6 (10.2%) | 11 (8.09%) | ||

| 4 degree. | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.74%) | ||

| ТV: | 0.437 | 195 | ||

| No | 9 (15.3%) | 22 (16.2%) | ||

| 1 degree. | 32 (54.2%) | 67 (49.3%) | ||

| 2 degree. | 16 (27.1%) | 46 (33.8%) | ||

| 3 degree. | 2 (3.39%) | 1 (0.74%) | ||

| AV: | 0.309 | 195 | ||

| No | 30 (50.8%) | 71 (52.2%) | ||

| 1 degree. | 22 (37.3%) | 49 (36.0%) | ||

| 2 degree. | 5 (8.47%) | 15 (11.0%) | ||

| 3 degree. | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.74%) | ||

| Stenosis | 2 (3.39%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| RV | 3.00 [2.80;3.40] | 3.10 [2.90;3.40] | 0.566 | 195 |

| LV aneurysm: | 0.990 | 195 | ||

| No | 50 (84.7%) | 117 (86.0%) | ||

| Yes | 9 (15.3%) | 19 (14.0%) | ||

| Heart Rate | 75.0 [66.0;82.0] | 71.5 [65.0;83.2] | 0.496 | 195 |

| USD of BCA: | 1.000 | 195 | ||

| No | 24 (40.7%) | 56 (41.2%) | ||

| Yes | 35 (59.3%) | 80 (58.8%) | ||

| RCA, degree: | 0.117 | 195 | ||

| minor | 44 (74.6%) | 84 (61.8%) | ||

| significant | 15 (25.4%) | 52 (38.2%) | ||

| LAD, degree: | 0.002 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 43 (72.9%) | 64 (47.1%) | ||

| Significant | 16 (27.1%) | 72 (52.9%) | ||

| LCA, degree: | 0.235 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 55 (93.2%) | 117 (86.0%) | ||

| Significant | 4 (6.78%) | 19 (14.0%) | ||

| CА, degree: | 0.002 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 51 (86.4%) | 85 (62.5%) | ||

| significant | 8 (13.6%) | 51 (37.5%) | ||

| DB, degree: | 0.001 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 54 (91.5%) | 94 (69.1%) | ||

| significant | 5 (8.47%) | 42 (30.9%) | ||

| PIVB, degree: | 0.006 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 58 (98.3%) | 113 (83.1%) | ||

| Significant | 1 (1.69%) | 23 (16.9%) | ||

| IА, degree: | 0.369 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 56 (94.9%) | 133 (97.8%) | ||

| significant | 3 (5.08%) | 3 (2.21%) | ||

| OMB, degree: | 0.002 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 56 (94.9%) | 102 (75.0%) | ||

| Significant | 3 (5.08%) | 34 (25.0%) | ||

| Number of shunts | 2.00 [2.00;3.00] | 3.00 [2.00;3.00] | <0.001 | 195 |

| Number of affected vessels | 3.00 [2.00;3.00] | 4.00 [3.75;5.00] | <0.001 | 195 |

| Statins: Yes | 59 (100%) | 136 (100%) | . | 195 |

| Ezetimibe: | <0.001 | 195 | ||

| No | 59 (100%) | 89 (65.4%) | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.00%) | 47 (34.6%) | ||

| Angina after CABG: | <0.001 | 195 | ||

| No | 7 (11.9%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Yes | 52 (88.1%) | 136 (100%) | ||

| Mortality after CABG: | 1.000 | 195 | ||

| No | 58 (98.3%) | 132 (97.1%) | ||

| Yes | 1 (1.69%) | 4 (2.94%) | ||

| Stenting after CABG: | <0.001 | 195 | ||

| No | 59 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.00%) | 136 (100%) | ||

| PRU | 145 [140;155] | 230 [200;274] | <0.001 | 195 |

| Dyslipidemia: | 1.000 | 195 | ||

| No | 2 (3.39%) | 4 (2.94%) | ||

| Yes | 57 (96.6%) | 132 (97.1%) | ||

| Anemia: | 0.941 | 195 | ||

| No | 52 (88.1%) | 122 (89.7%) | ||

| Yes | 7 (11.9%) | 14 (10.3%) | ||

| CKD: | 0.977 | 195 | ||

| No | 53 (89.8%) | 124 (91.2%) | ||

| Yes | 6 (10.2%) | 12 (8.82%) | ||

| Obesity: | 0.406 | 195 | ||

| No | 17 (28.8%) | 30 (22.1%) | ||

| Yes | 42 (71.2%) | 106 (77.9%) | ||

| RPR: | <0.001 | 195 | ||

| Therapeutic window | 59 (100%) | 46 (33.8%) | ||

| HRPR | 0 (0.00%) | 90 (66.2%) |

| Therapeutic window | HRPR | p-value | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=105 | N=90 | |||

| Age | 69.0 [62.0;74.0] | 70.5 [65.2;75.0] | 0.147 | 195 |

| Gender: | 0.871 | 195 | ||

| female | 29 (27.6%) | 23 (25.6%) | ||

| male | 76 (72.4%) | 67 (74.4%) | ||

| Smoking: | 0.030 | 195 | ||

| No | 59 (56.2%) | 65 (72.2%) | ||

| Yes | 46 (43.8%) | 25 (27.8%) | ||

| Alcohol: | 1.000 | 195 | ||

| No | 102 (97.1%) | 88 (97.8%) | ||

| Yes | 3 (2.86%) | 2 (2.22%) | ||

| Weight | 78.0 [69.0;85.0] | 80.0 [70.2;88.0] | 0.199 | 195 |

| Height | 168 [163;174] | 170 [162;173] | 0.838 | 195 |

| BMI | 27.2 [25.0;29.4] | 28.1 [25.9;30.6] | 0.096 | 195 |

| Heredity: | 0.475 | 195 | ||

| No | 67 (63.8%) | 52 (57.8%) | ||

| Yes | 38 (36.2%) | 38 (42.2%) | ||

| Dyspnea: | 0.739 | 194 | ||

| No | 7 (6.67%) | 8 (8.99%) | ||

| Yes | 98 (93.3%) | 81 (91.0%) | ||

| Edema: | 0.801 | 195 | ||

| No | 91 (86.7%) | 80 (88.9%) | ||

| Yes | 14 (13.3%) | 10 (11.1%) | ||

| Pain: | 0.510 | 195 | ||

| No | 6 (5.71%) | 3 (3.33%) | ||

| Yes | 99 (94.3%) | 87 (96.7%) | ||

| Weakness: | 0.252 | 195 | ||

| No | 2 (1.90%) | 5 (5.56%) | ||

| Yes | 103 (98.1%) | 85 (94.4%) | ||

| Heartbeat: | 1.000 | 195 | ||

| No | 90 (85.7%) | 78 (86.7%) | ||

| Yes | 15 (14.3%) | 12 (13.3%) | ||

| Short of breath: | 0.778 | 195 | ||

| No | 74 (70.5%) | 66 (73.3%) | ||

| Yes | 31 (29.5%) | 24 (26.7%) | ||

| SBP | 120 [115;130] | 130 [120;140] | 0.031 | 195 |

| DBP | 80.0 [70.0;80.0] | 80.0 [70.0;80.0] | 0.320 | 195 |

| History of myocardial infarction: | 0.394 | 195 | ||

| No | 53 (50.5%) | 39 (43.3%) | ||

| Yes | 52 (49.5%) | 51 (56.7%) | ||

| АH: | 0.510 | 195 | ||

| No | 6 (5.71%) | 3 (3.33%) | ||

| Yes | 99 (94.3%) | 87 (96.7%) | ||

| DM type 2: | 0.293 | 195 | ||

| No | 75 (71.4%) | 57 (63.3%) | ||

| Yes | 30 (28.6%) | 33 (36.7%) | ||

| History of Stroke: | 0.031 | 195 | ||

| No | 101 (96.2%) | 78 (86.7%) | ||

| Yes | 4 (3.81%) | 12 (13.3%) | ||

| CKD: | 0.697 | 195 | ||

| No | 60 (57.1%) | 48 (53.3%) | ||

| Yes | 45 (42.9%) | 42 (46.7%) | ||

| Stenting: | 0.897 | 195 | ||

| No | 87 (82.9%) | 73 (81.1%) | ||

| Yes | 18 (17.1%) | 17 (18.9%) | ||

| CABG: | 0.065 | 195 | ||

| No | 12 (11.4%) | 3 (3.33%) | ||

| Yes | 93 (88.6%) | 87 (96.7%) | ||

| IHD, duration | 2.00 [1.00;8.00] | 3.00 [1.00;9.75] | 0.888 | 195 |

| Hemoglobin | 142 [132;154] | 150 [136;156] | 0.053 | 195 |

| СRP | 2.36 [1.27;4.10] | 2.29 [1.02;4.13] | 0.853 | 195 |

| Glucose | 5.54 [5.00;6.20] | 5.90 [5.23;7.10] | 0.022 | 195 |

| HbA1c | 6.01 [5.38;6.70] | 6.06 [5.52;7.83] | 0.282 | 195 |

| Creatinine | 80.0 [71.0;91.8] | 79.0 [70.3;92.7] | 0.890 | 195 |

| GFR | 87.0 [74.0;96.0] | 81.0 [70.0;92.5] | 0.361 | 195 |

| Potassium | 4.30 [4.10;4.50] | 4.35 [4.10;4.60] | 0.267 | 195 |

| Sodium | 142 [141;144] | 142 [140;144] | 0.931 | 195 |

| ALT | 18.0 [12.0;27.5] | 19.0 [14.0;26.4] | 0.473 | 195 |

| AST | 17.6 [13.8;25.8] | 17.7 [15.0;22.7] | 0.934 | 195 |

| TC | 4.30 [3.67;5.27] | 4.50 [3.63;5.20] | 0.571 | 195 |

| LDL | 2.43 [2.00;3.10] | 2.64 [2.00;3.39] | 0.546 | 195 |

| HDL | 1.00 [0.98;1.01] | 1.00 [0.96;1.04] | 0.684 | 195 |

| ТG | 1.37 [1.00;1.80] | 1.38 [1.00;1.79] | 0.981 | 195 |

| Troponin I | 15.0 [11.0;58.7] | 15.0 [11.0;40.0] | 0.635 | 195 |

| TSH | 2.00 [1.60;3.00] | 1.96 [1.25;3.18] | 0.517 | 195 |

| Thyroxine | 13.9 [11.5;16.2] | 14.7 [12.3;16.3] | 0.335 | 193 |

| PTI | 94.5 [80.0;103] | 96.3 [78.5;106] | 0.209 | 195 |

| INR | 1.06 [1.01;1.16] | 1.04 [1.00;1.15] | 0.189 | 195 |

| APTT | 31.4 [29.0;35.9] | 31.4 [28.6;36.0] | 0.524 | 195 |

| EDV | 157 [119;194] | 131 [113;174] | 0.053 | 195 |

| ESV | 72.0 [44.0;108] | 60.0 [46.0;91.2] | 0.256 | 195 |

| SV | 78.0 [65.0;91.0] | 77.0 [59.0;90.0] | 0.268 | 195 |

| sPAP | 34.0 [23.8;44.0] | 35.0 [20.8;40.8] | 0.624 | 194 |

| EF | 49.0 [41.0;60.0] | 51.7 [45.0;58.9] | 0.459 | 195 |

| LA | 3.80 [3.50;4.40] | 3.80 [3.60;4.40] | 0.907 | 195 |

| EDD | 5.60 [5.10;6.20] | 5.20 [4.90;5.90] | 0.043 | 195 |

| ESD | 4.00 [3.30;4.80] | 3.74 [3.40;4.38] | 0.394 | 195 |

| LVPW | 1.10 [0.90;1.20] | 1.10 [1.00;1.20] | 0.087 | 195 |

| IVS | 1.10 [1.00;1.30] | 1.10 [0.90;1.30] | 0.366 | 195 |

| МV: | 0.291 | 195 | ||

| No | 7 (6.67%) | 10 (11.1%) | ||

| 1 degree. | 62 (59.0%) | 49 (54.4%) | ||

| 2 degree. | 24 (22.9%) | 25 (27.8%) | ||

| 3 degree. | 12 (11.4%) | 5 (5.56%) | ||

| 4 degree. | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (1.11%) | ||

| ТV: | 0.717 | 195 | ||

| No | 14 (13.3%) | 17 (18.9%) | ||

| 1 degree. | 55 (52.4%) | 44 (48.9%) | ||

| 2 degree. | 34 (32.4%) | 28 (31.1%) | ||

| 3 degree. | 2 (1.90%) | 1 (1.11%) | ||

| AV: | 0.070 | 195 | ||

| No | 51 (48.6%) | 50 (55.6%) | ||

| 1 degree. | 44 (41.9%) | 27 (30.0%) | ||

| 2 degree. | 7 (6.67%) | 13 (14.4%) | ||

| 3 degree. | 1 (0.95%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Stenosis | 2 (1.90%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| RV | 3.00 [2.90;3.40] | 3.10 [2.90;3.30] | 0.893 | 195 |

| LV aneurysm: | 0.862 | 195 | ||

| No | 89 (84.8%) | 78 (86.7%) | ||

| Yes | 16 (15.2%) | 12 (13.3%) | ||

| Heart Rate | 74.0 [66.0;83.0] | 70.5 [65.0;82.0] | 0.483 | 195 |

| USD of BCA: | 0.196 | 195 | ||

| No | 48 (45.7%) | 32 (35.6%) | ||

| Yes | 57 (54.3%) | 58 (64.4%) | ||

| RCA, degree: | 0.022 | 195 | ||

| minor | 77 (73.3%) | 51 (56.7%) | ||

| significant | 28 (26.7%) | 39 (43.3%) | ||

| LAD, degree: | 0.002 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 69 (65.7%) | 38 (42.2%) | ||

| Significant | 36 (34.3%) | 52 (57.8%) | ||

| LCA, degree: | 0.694 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 94 (89.5%) | 78 (86.7%) | ||

| Significant | 11 (10.5%) | 12 (13.3%) | ||

| CА, degree: | 0.001 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 84 (80.0%) | 52 (57.8%) | ||

| significant | 21 (20.0%) | 38 (42.2%) | ||

| DB, degree: | 0.003 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 89 (84.8%) | 59 (65.6%) | ||

| significant | 16 (15.2%) | 31 (34.4%) | ||

| PIVB, degree: | 0.001 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 100 (95.2%) | 71 (78.9%) | ||

| Significant | 5 (4.76%) | 19 (21.1%) | ||

| IА, degree: | 0.688 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 101 (96.2%) | 88 (97.8%) | ||

| significant | 4 (3.81%) | 2 (2.22%) | ||

| OMB, degree: | <0.001 | 195 | ||

| Minor | 98 (93.3%) | 60 (66.7%) | ||

| Significant | 7 (6.67%) | 30 (33.3%) | ||

| Number of shunts | 2.00 [2.00;3.00] | 3.00 [2.00;4.00] | 0.001 | 195 |

| Number of affected vessels | 3.00 [2.00;3.00] | 4.00 [4.00;5.00] | <0.001 | 195 |

| Statins: Yes | 105 (100%) | 90 (100%) | . | 195 |

| Ezetimibe: | <0.001 | 195 | ||

| No | 101 (96.2%) | 47 (52.2%) | ||

| Yes | 4 (3.81%) | 43 (47.8%) | ||

| Angina after CABG: | 0.016 | 195 | ||

| No | 7 (6.67%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Yes | 98 (93.3%) | 90 (100%) | ||

| Mortality after CABG: | 0.183 | 195 | ||

| No | 104 (99.0%) | 86 (95.6%) | ||

| Yes | 1 (0.95%) | 4 (4.44%) | ||

| Stenting after CABG: | <0.001 | 195 | ||

| No | 59 (56.2%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Yes | 46 (43.8%) |

90 (100%) !!! |

||

| PRU | 170 [141;200] | 255 [230;280] | <0.001 | 195 |

| Dyslipidemia: | 0.688 | 195 | ||

| No | 4 (3.81%) | 2 (2.22%) | ||

| Yes | 101 (96.2%) | 88 (97.8%) | ||

| Anemia: | 0.310 | 195 | ||

| No | 91 (86.7%) | 83 (92.2%) | ||

| Yes | 14 (13.3%) | 7 (7.78%) | ||

| CKD: | 0.689 | 195 | ||

| No | 94 (89.5%) | 83 (92.2%) | ||

| Yes | 11 (10.5%) | 7 (7.78%) | ||

| Obesity: | 0.462 | 195 | ||

| No | 28 (26.7%) | 19 (21.1%) | ||

| Yes | 77 (73.3%) | 71 (78.9%) | ||

| RPR: | <0.001 | 195 | ||

| Therapeutic window | 105 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| HRPR | 0 (0.00%) | 90 (100%) |

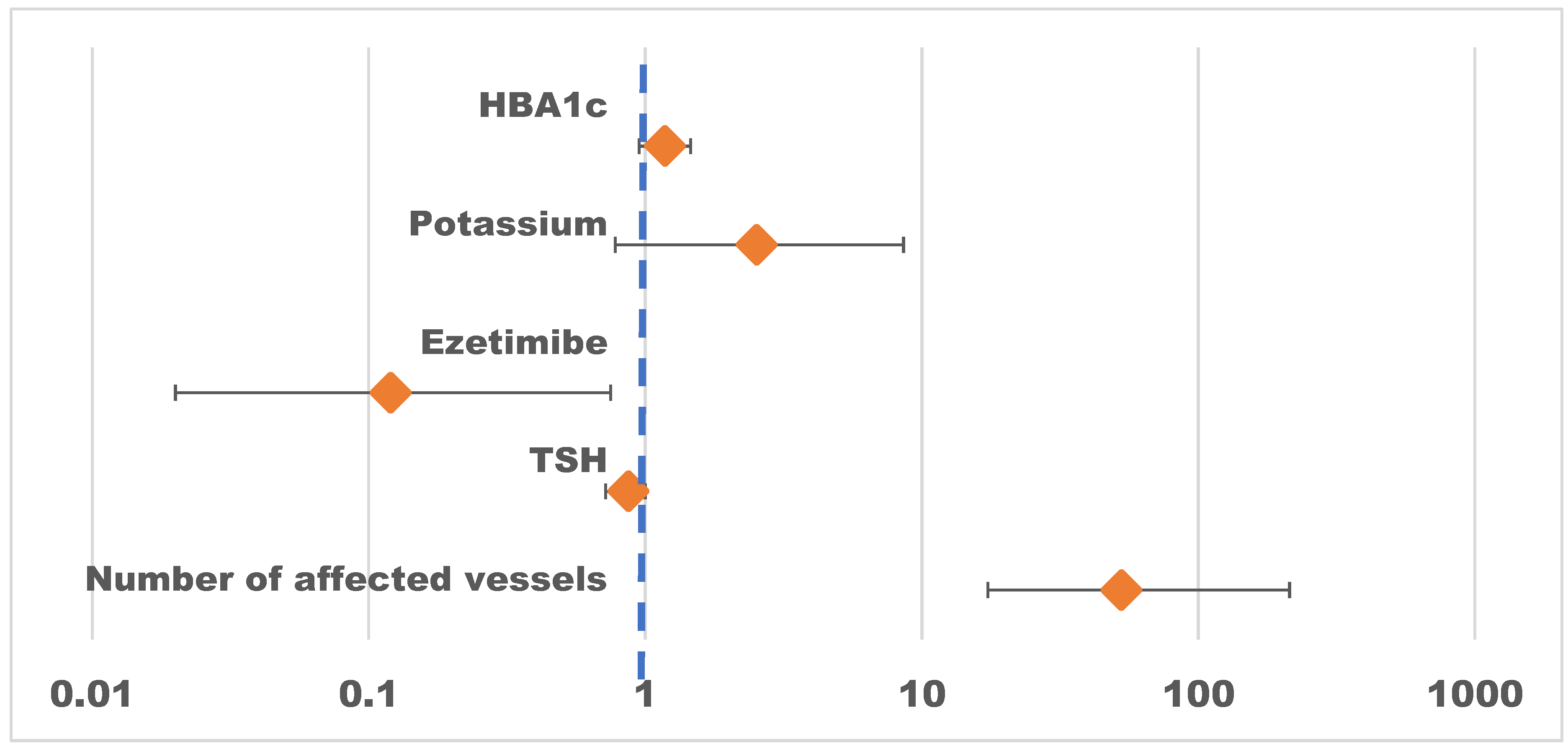

| HRPR | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Odds Ratios | CI | p |

| Number of affected vessels | 52.67 | 17.33 – 213.77 | <0.001 |

| ТSH | 0.87 | 0.72 – 1.00 | 0.116 |

| Ezetimibe: Yes | 0.12 | 0.02 – 0.75 | 0.023 |

| Potassium | 2.53 | 0.78 – 8.59 | 0.127 |

| Hb A 1 c | 1.18 | 0.95 – 1.46 | 0.138 |

| Observations | 195 | ||

| R2 Tjur | 0.681 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).