Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

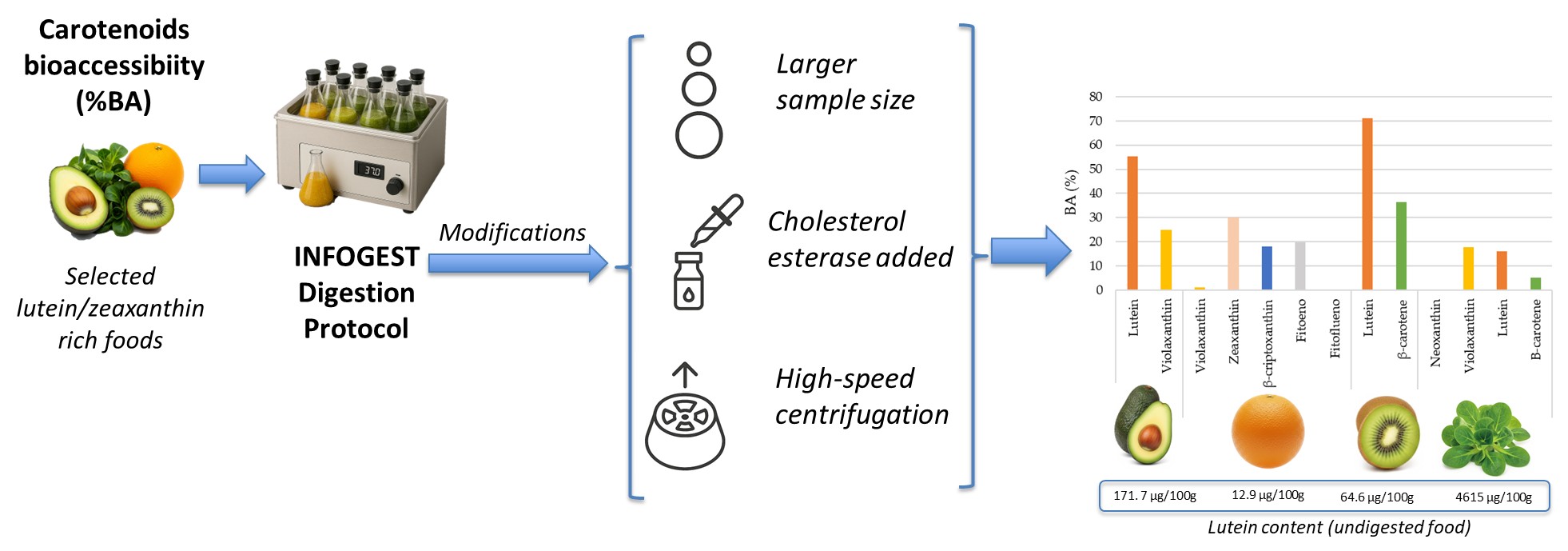

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Samples

2.3. Extraction, Saponification and HPLC Analysis of Carotenoids

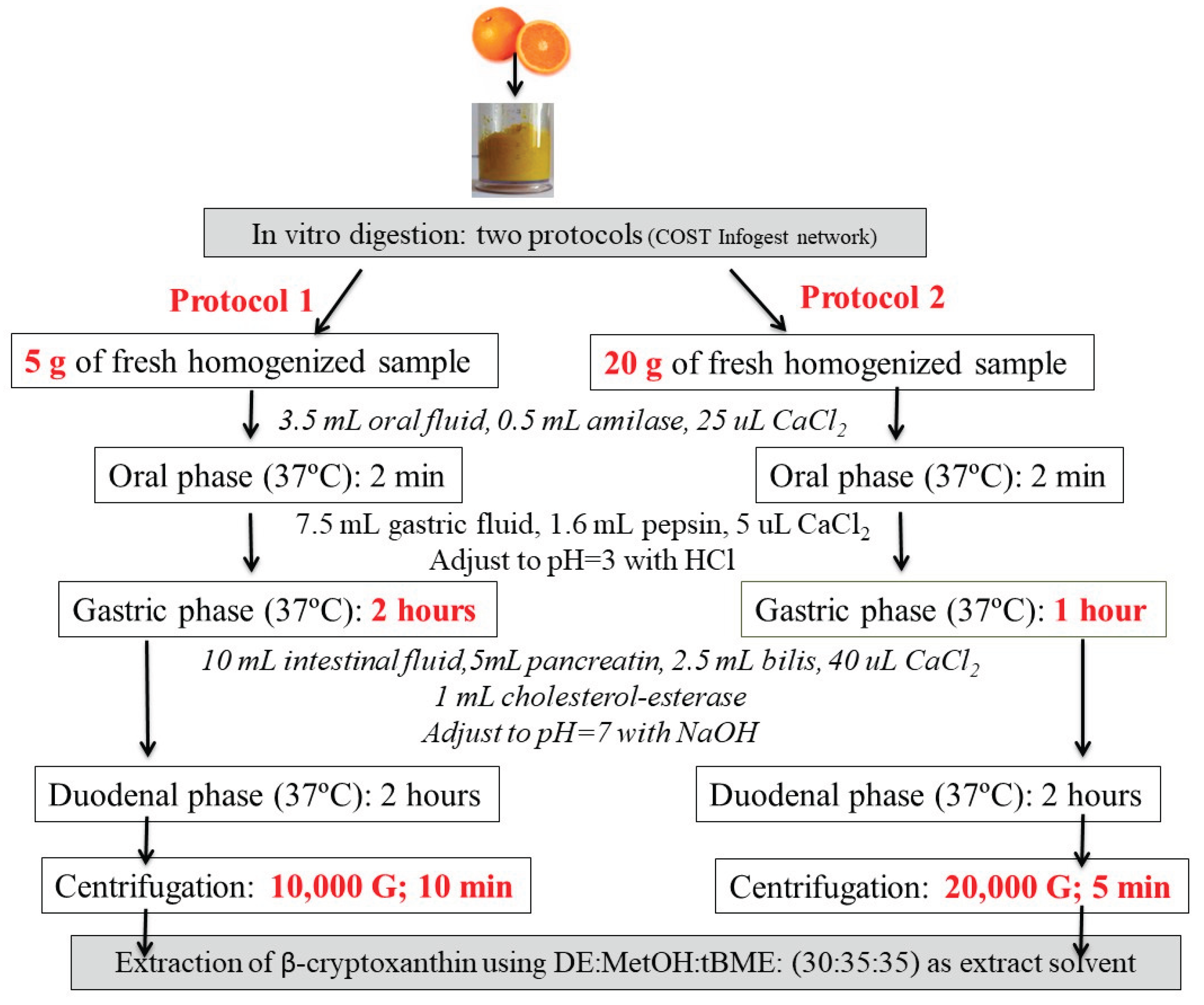

2.4. Selection of Digestion Protocol and the Extraction Method for Carotenoids from Digested Foods

- Protocol 1: 5 g homogenized sample was mixed with reagents specified by INFOGEST [8] plus cholesterol esterase (3,077 U/mL). The phases lasted 2 minutes (oral), 2 hours (gastric), and 2 hours (duodenal phase). After digestion, centrifugation was performed at 10,000 G for 10 minutes, which were the conditions we followed in previous studies [12].

- Protocol 2: Similar to Protocol 1, but a 20 g sample was used and, and, as a result, the enzyme concentration was also quadrupled (aimed to achieve higher absorbance values and reduce analytical determination errors). Furthermore, the gastric phase was shortened to 1 hour, and centrifugation was performed at 20,000 G for 5 minutes (to transfer carotenoids from the duodenal digesta to the aqueous-micellar phase). The centrifugation conditions were selected in based on different assays previously conducted on kiwis (Actinidia deliciosa) that were extracted, digested following protocol 1 and centrifuged at the last step following different conditions: 5,000 G, 20 min; 10,000 G, 5 min; 10,000 G, 10 min; 10,000 G, 20 min and 20,000 G, 5 min. Centrifugation assays conducted on kiwis (Actinidia deliciosa) showed the following BA percentages: 8.9% (5,000 G, 20 min), 10% (10,000 G, 5 min), 6.4% (10,000 G, 10 min), 5.1% (10,000 G, 20 min), and 16.6% (20,000 G, 5 min).

2.5. Digestion of Foods

3. Results

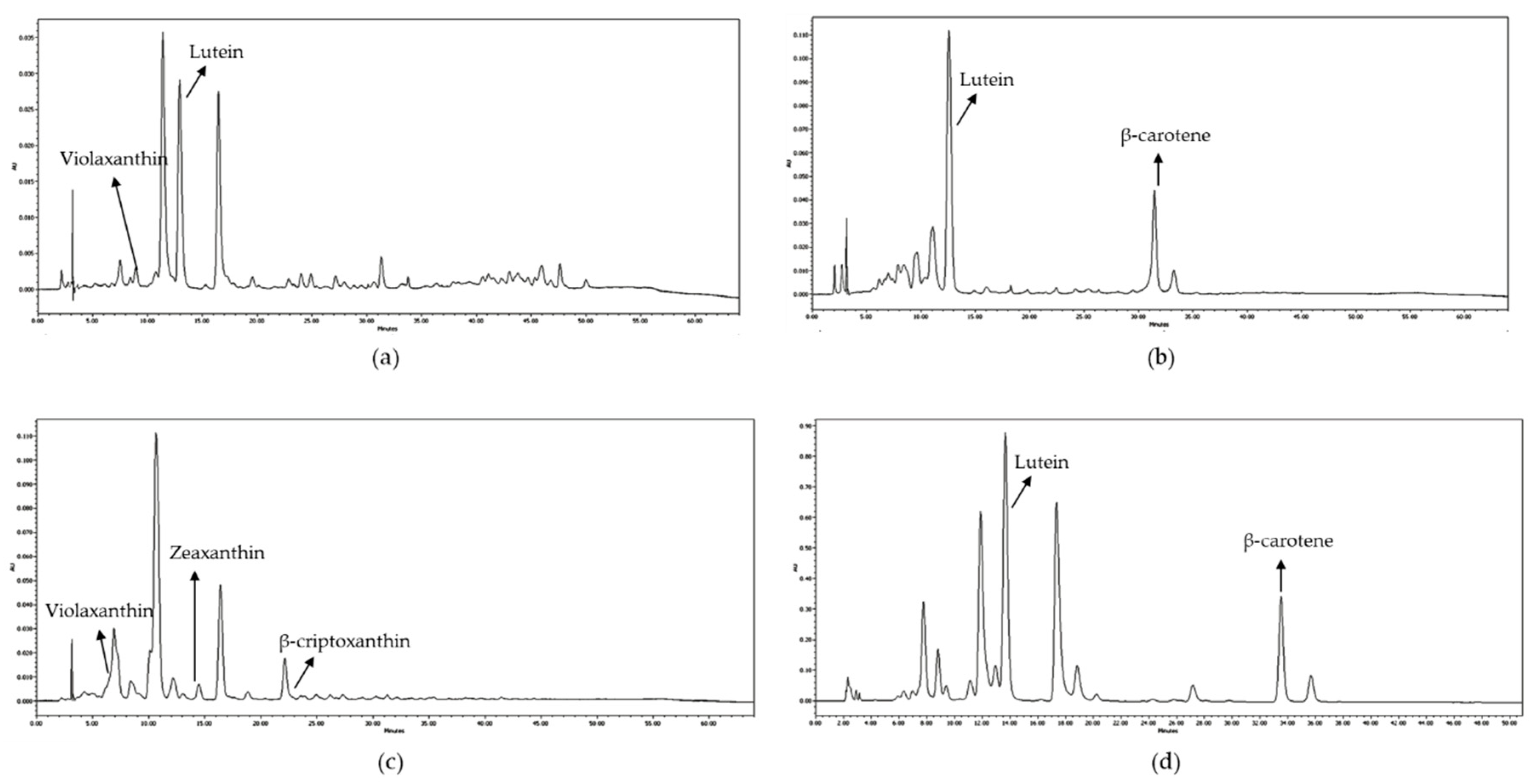

3.1. Carotenoids Content in Fruits and Vegetables

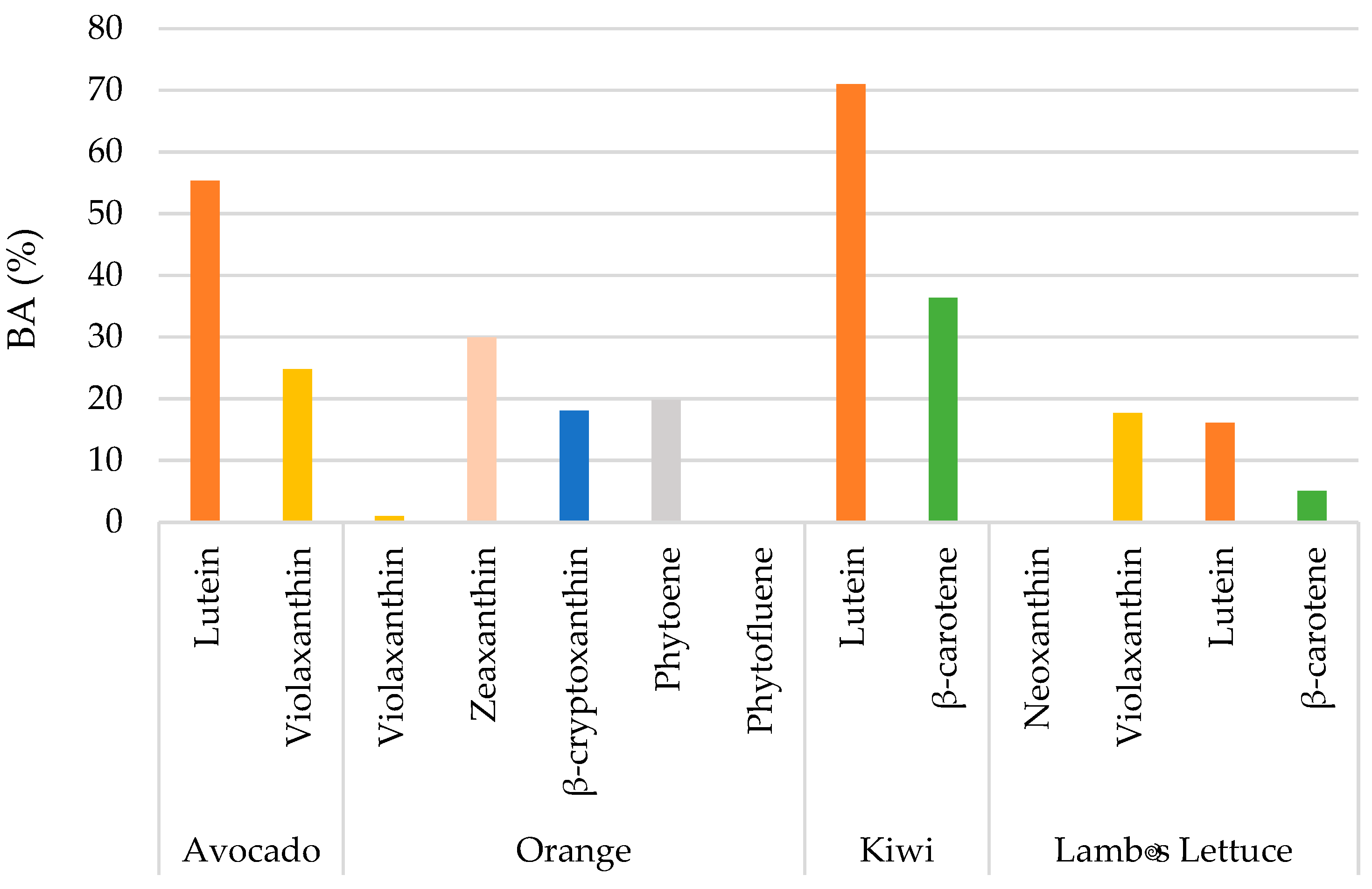

3.2. Stability and BA of Carotenoids After the Digestion Process

4. Discussion

4.1. Selection of Digestion Protocol and the Extraction Method for Carotenoids from Digested Foods

4.2. Stability of Carotenoids During Digestion

4.3. Carotenoids BA

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| O | Oral phase |

| G | Gastric phase |

| D | Duodenal phase |

| BA | Bioaccessibility |

References

- Rodríguez-Concepción, M.; Ávalos, F.; Bonet, M.L.; Boronat, A.; Gómez-Gómez, L.; Hornero-Méndez, D.; Limón, C.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Palou, A.; et al. A global perspective on carotenoids: metabolism, biotechnology, and benefits for nutrition and health. Prog. Lipid Res. 2018, 70, 62–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Agrón, E.; Domalpally, A.; Keenan, T.D.L.; Vitale, S.; Weber, C.; Smith, D.C.; Christen, W.; AREDS2 Research Group. Long-term Outcomes of Adding Lutein/Zeaxanthin and ω-3 Fatty Acids to the AREDS Supplements on Age-Related Macular Degeneration Progression: AREDS2 Report 28. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022, 140, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, V.; Lietz, G.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Phelan, D.; Reboul, E.; Bánati, D.; Borel, P.; Corte-Real, J.; de Lera, A.R.; Desmarchelier, C.; et al. From carotenoid intake to carotenoid blood and tissue concentrations—Implications for dietary intake recommendations. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 544–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Granado-Lorencio, F.; Castro-Feito, J.; Herrero-Barbudo, C.; Blanco-Navarro, I.; Estévez-Santiago, R. Bioavailability of lutein from marigold flowers (free vs ester forms): A randomised cross-over study to assess serum response and visual contrast threshold in adults. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, A.A.O.; Mercadante, A.Z. A guide for the evaluation of in vitro bioaccessibility of carotenoids. Methods Enzymol. 2022, 674, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corte-Real, J.; Iddir, M.; Soukoulis, C.; Richling, E.; Hoffmann, L.; Bohn, T. Effect of divalent minerals on the bioaccessibility of pure carotenoids and on physical properties of gastro-intestinal fluids. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iddir, M.; Porras Yaruro, J.F.; Larondelle, Y.; Bohn, T. Gastric lipase can significantly increase lipolysis and carotenoid bioaccessibility from plant food matrices in the harmonized INFOGEST static in vitro digestion model. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 9043–9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food—an international consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado-Lorencio, F.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Herrero-Barbudo, C.; Blanco-Navarro, I.; Pérez-Sacristán, B.; Blázquez-García, S. In vitro bioaccessibility of carotenoids and tocopherols from fruits and vegetables. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.; Beltrán-de-Miguel, B.; Sánchez-Prieto, M.; Estévez-Santiago, R. Changes in Lutein Status Markers (Serum and Faecal Concentrations, Macular Pigment) in Response to a Lutein-Rich Fruit or Vegetable (Three Pieces/Day) Dietary Intervention in Normolipemic Subjects. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Rosso, V.V.; Mercadante, A.Z. Identification and quantification of carotenoids, by HPLC-PDA-MS/MS, from Amazonian fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 5062–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Santiago, R.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Fernández-Jalao, I. Bioaccessibility of provitamin A carotenoids from fruits: application of a standardised static in vitro digestion method. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 1354–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado, F.; Olmedilla, B.; Gil-Martinez, E.; Blanco, I. A Fast, Reliable and Low-cost Saponification Protocol for Analysis of Carotenoids in Vegetables. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2001, 14, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Granado-Lorencio, F.; Blanco-Navarro, I. Carotenoids, retinol and tocopherols in blood: Comparability between serum and plasma (Li-heparin) values. Clin. Biochem. 2005, 38, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Santiago, R.; Beltrán-de-Miguel, B.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B. Assessment of dietary lutein, zeaxanthin and lycopene intakes and sources in the Spanish Survey of Dietary Intake (2009-2010). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 67, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.G.; Borge, G.I.A.; Kljak, K.; Mandić, A.I.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Pintea, A.M.; Ravasco, F.; Šaponjac, V.T.; Sereikaitė, J.; et al. European database of carotenoid levels in foods. Factors affecting carotenoid content. Foods 2021, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Lee, R.P.; Gao, K.; Byrns, R.; Heber, D. California Hass avocado: profiling of carotenoids, tocopherol, fatty acid, and fat content during maturation and from different growing areas. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10408–10413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, N.A.; Spagnuolo, P.; Kraft, J.; Bauer, E. Nutritional Composition of Hass Avocado Pulp. Foods 2023, 12, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, O.B.; Wong, M.; McGhie, T.K.; Vather, R.; Wang, Y.; Requejo-Jackman, C.; Ramankutty, P.; Woolf, A.B. Pigments in avocado tissue and oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 10151–10158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Lee, R.P.; Gao, K.; Byrns, R.; Heber, D. California Hass avocado: Profiling of carotenoids, tocopherol, fatty acid, and fat content during maturation and from different growing areas. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10408–10413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.G.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Hornero-Méndez, D.; Mercadante, A.Z.; Osorio, C.; Vargas-Murga, L.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Comprehensive database of carotenoid contents in ibero-american foods. A valuable tool in the context of functional foods and the establishment of recommended intakes of bioactives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 5055–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, M.J.; Cilla, A.; Barberá, R.; Zacarías, L. Carotenoid bioaccessibility in pulp and fresh juice from carotenoid-rich sweet oranges and mandarins. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacarías-García, J.; Cronje, P.J.; Diretto, G.; Zacarías, L.; Rodrigo, M.J. A comprehensive analysis of carotenoids metabolism in two red-fleshed mutants of Navel and Valencia sweet oranges (Citrus sinensis). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1034204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Evoli, L.; Moscatello, S.; Lucarini, M.; Aguzzi, A.; Gabrielli, P.; Proietti, S.; Battistelli, A.; Famiani, F.; Böhm, V.; Lombardi-Boccia, G. Nutritional traits and antioxidant capacity of kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa Planch., cv. Hayward) grown in Italy. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2015, 37, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. , Deng, Z., Lu, J., Liu, H., & Chen, F. Effects of High-Temperature Frying of Spinach Leaves in Sunflower Oil on Carotenoids, Chlorophylls, and Tocopherol Composition. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, A.; Andjelkovic, M.; Socaciu, C.; Bobis, O.; Neacsu, M.; Verhé, R.; Van Camp. Total and individual carotenoids and phenolic acids content in fresh, refrigerated and processed spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). Food Chem. 2008, 108, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, F.C.; Mercadante, A.Z. Impact of in vitro digestion phases on the stability and bioaccessibility of carotenoids and their esters in mandarin pulps. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 3951–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, D.B.; Mariutti, L.R.; Mercadante, A.Z. An in vitro digestion method adapted for carotenoids and carotenoid esters: moving forward towards standardization. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 4992–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado-Lorencio, F.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Herrero-Barbudo, C.; Pérez-Sacristán, B.; Blanco-Navarro, I.; Blázquez-García, S. Comparative in vitro bioaccessibility of carotenoids from relevant contributors to carotenoid intake. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10887–10892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, F.C.; Mercadante, A.Z. In vitro bioaccessibility of carotenoids from fruits and vegetables: A review. Food Res. Int. 2016, 88, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Reboul, E.; Borel, P. Digestion and Absorption of Carotenoids: The Physiologically Relevant Micellar Fraction. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2011, 7, 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Hu, T.; Hu, H.; Xiong, S.; Shi, K.; Zhang, N.; Mu, Q.; Xu, G.; Zhang, P.; Pan, S. Comparative evaluation on the bioaccessibility of citrus fruit carotenoids in vitro based on different intake patterns. Foods 2022, 11, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Failla, M.L.; Huo, T.; Thakkar, S.K. In vitro screening of relative bioaccessibility of carotenoids from foods. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17 (Suppl. 1), 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Granado, F.; Olmedilla, B.; Herrero, C.; Pérez-Sacristán, B.; Blanco, I.; Blázquez, S. Bioavailability of carotenoids and tocopherols from broccoli: in vivo and in vitro assessment. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2006, 231, 1733–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimode, S.; Miyata, K.; Araki, M.; Shindo, K. Antioxidant activities of the antheraxanthin-related carotenoids, antheraxanthin, 9-cis-antheraxanthin, and mutatoxanthins. Oleo Sci. 2018, 67, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboul, E.; Margier, M.; Desmarchelier, C.; Halimi, C.; Nowicki, M.; Borel, P.; Mapelli-Brahm, P. Comparison of the bioavailability and intestinal absorption sites of phytoene, phytofluene, lycopene and β-carotene. Food Chem. 2019, 297, 125232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Corte-Real, J.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Bohn, T. Bioaccessibility of phytoene and phytofluene is superior to other carotenoids from selected fruit and vegetable juices. Food Chem. 2017, 229, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.; Estévez-Santiago, R.; Sánchez-Prieto, M.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B. Status and dietary intake of phytoene and phytofluene in Spanish adults and the effect of a four-week dietary intervention. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.P.; Ansell, J.; Drummond, L.N. The nutritional and health attributes of kiwifruit: a review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2659–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courraud, J.; Berger, J.; Cristol, J.P.; Avallone, S. Stability and bioaccessibility of different forms of carotenoids and vitamin A during in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, G.T.; Bailey, A.L.; Faulks, R.M.; Parker, M.L.; Wickham, M.S.J.; Fillery-Travis, A. Solubilization of carotenoids from carrot juice and spinach in lipid phases: I. Modeling the gastric lumen. Lipids 2003, 38, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, A.; Terasaki, M.; Nagao, A. An epoxide-furanoid rearrangement of spinach neoxanthin occurs in the gastrointestinal tract of mice and in vitro: formation and cytostatic activity of neochrome stereoisomers. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2237–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asai, A.; Yonekura, L.; Nagao, A. Low bioavailability of dietary epoxyxanthophylls in humans. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.B.; Chitchumroonchokchai, C.; Mariutti, L.R.B.; Mercadante, A.Z.; Failla, M.L. Comparison of two static in vitro digestion methods for screening the bioaccessibility of carotenoids in fruits, vegetables, and animal products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 11220–11228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, O.; Ryan, L.; O’Brien, N. Xanthophyll carotenoids are more bioaccessible from fruits than dark green vegetables. Nutr. Res. 2007, 27, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, D.J.; Alsherbiny, M.A.; Perera, S.; Low, M.; Basu, A.; Devi, O.A.; Barooah, M.S.; Li, C.G.; Papoutsis, K. The Odyssey of Bioactive Compounds in Avocado (Persea americana) and Their Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Paz, B.; Yahia, E.M.; Ornelas-Paz, J.J.; Victoria-Campos, C.I.; Perez-Martinez, J.D.; Reyes-Hernandez, J. Bioaccessibility of fat-soluble bioactive compounds (FSBC) from avocado fruit as affected by ripening and FSBC composition in the food matrix. Food Res. Int. 2021, 139, 109960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, N.; Ampomah-Dwamena, C.; Voogd, C.; Allan, A.C. Comparative transcriptomic and plastid development analysis sheds light on the differential carotenoid accumulation in kiwifruit flesh. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1213086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Paz, B.; Ornelas-Paz, J.J.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Rios-Velasco, C.; Ibarra-Junquera, V.; Yahia, E.M.; Gardea-Béjar, A.A. Effects of pectin on lipid digestion and possible implications for carotenoid bioavailability during pre-absorptive stages: A review. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, M.J.; Cilla, A.; Barberá, R.; Zacarías, L. Food carotenoid bioaccessibility in pulp and fresh juice from carotenoid-rich sweet oranges and mandarins. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, M.; Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. Carotenoid Composition of Hydroponic Leafy Vegetables. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2603–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärtner, C.; Stahl, W.; Sies, H. Lycopene is more bioavailable from tomato paste than from fresh tomatoes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 66, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Ordóñez, T.; Carle, R.; Schweiggert, R. Bioaccessibility of carotenoids from plant and animal foods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 3220–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Granado-Lorencio, F.; De Ancos, B.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Blanco, I.; Herrero-Barbudo, C.; Elez, P.; Plaza, L.; Cano, M.P. Greater bioavailability of xanthophylls compared to carotenes from orange juice (high-pressure processed, pulsed electric field treated, low-temperature pasteurised, and freshly squeezed) in a crossover study in healthy individuals. Food Chem. 2022; 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riso, P.; Brusamolino, A.; Ciappellano, S.; Porrini, M. Comparison of lutein bioavailability from vegetables and supplement. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2003, 73, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Undigested food | O | O+G | O+G+D | Mixed micelles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avocado | |||||

| Lutein | 171.67 | 143.19 | 53.46 | 164.52 | 94.96 |

| Violaxanthin | 128.8 | 41.31 | n.d. | n.d. | 31.94 |

| Orange | |||||

| Violaxanthin | 51.03 | 44.82 | 19.33 | 9.43 | 0.52 |

| Zeaxanthin | 12.85 | 15.98 | 16.1 | 10.85 | 3.85 |

| β-cryptoxanthin | 73.39 | 54.32 | 53.89 | 36.95 | 13.23 |

| Phytoene | 7.33 | 1.94 | 1.85 | 2.16 | 1.45 |

| Phytofluene | Tr | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Kiwi | |||||

| Lutein | 64.55 | 51.85 | 50.56 | 47.58 | 45.84 |

| β-carotene | 35.5 | 35.41 | 30.42 | 22.52 | 12.92 |

| Lamb´s lettuce | |||||

| Neoxanthin | 940.31 | 315.87 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Violaxanthin | 1535.81 | 302.05 | n.d. | 307.93 | 271.19 |

| Lutein | 4615.03 | 1247.42 | 557.02 | 626.74 | 743.82 |

| β-carotene | 2156.42 | 697.5 | 682.08 | 347.97 | 109.54 |

| Recovery (%) | Loss (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | O+G | O+G+D | O | O+G | O+G+D | |

| Avocado | ||||||

| Lutein | 83.41 | 31.14 | 95.84 | 53.46 | 164.52 | 94.96 |

| Violaxanthin | 32.07 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 31.94 |

| Orange | ||||||

| Violaxanthin | 87.83 | 37.88 | 18.48 | 12.17 | 62.12 | 81.52 |

| Zeaxanthin | 124.36 | 125.29 | 84.44 | -24.36 | -25.29 | 15.56 |

| β-cryptoxanthin | 74.02 | 73.43 | 50.35 | 25.98 | 26.57 | 49.65 |

| Phytoene | 26.47 | 25.24 | 29.47 | 73.53 | 74.76 | 70.53 |

| Phytofluene | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Kiwi | ||||||

| Lutein | 80.33 | 78.33 | 73.71 | 19.67 | 21.67 | 26.29 |

| β-carotene | 99.75 | 85.69 | 63.44 | 0.25 | 14.31 | 36.56 |

| Lamb´s lettuce | ||||||

| Neoxanthin | 33.59 | n.d. | n.d. | 66.41 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Violaxanthin | 19.67 | n.d. | 20.05 | 80.33 | n.d. | 79.95 |

| Lutein | 27.03 | 12.07 | 13.58 | 72.97 | 87.93 | 86.42 |

| β-carotene | 32.35 | 31.63 | 16.14 | 67.65 | 68.37 | 83.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).