Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction:

- 1.

- Initially started at a daily dose of 5-10 mg tablets; if necessary, can be titrated upward with increments of 5 mg/day at intervals of more than a week to reach the maintenance dose of 20mg daily but not more.

- 2.

- Based on oral dose, recommended (IM) doses are as follows:

- A.

- Daily oral dose of 10mg: is equivalent to 210 mg IM dose every 2 weeks, or 405 mg IM every 4 weeks (for 1st 8 weeks), so 150 mg every 2 weeks or 300 mg every 4 weeks.

- B.

- Daily oral dose of 15 mg: is equivalent to 300 mg IM dose (for the 1st 8 weeks) every 2 weeks, then 210mg IM (every 2 weeks) or 405 mg IM (every 4 weeks).

- C.

- Daily oral dose of 20 mg: is equivalent to 300 mg IM (every 2 weeks), for the 1st 8 weeks, if titration is optimal against therapeutic effects, the maintenance dose is 300mg IM (every 2 weeks). The data regarding OLZ doses dedicated to schizophrenia mentioned above is obtained from [5].

- Eating disorders, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, delusional parasitosis, and post-traumatic stress. The use of OLZ in these disorders has not been evaluated rigorously enough.

- This agent has been used for Tourette syndrome and stuttering [7].

- Attention-deficient hyperactivity, aggressiveness, and repetitive behavior of autism [8].

- Insomnia, the effect is comparable to quetiapine and lurasidone [9]. In some cases, the sedation caused by OLZ impairs the ability of individuals to wake up at a steady, consistent time every day. Long-term studies of the safety of OLZ to treat insomnia are still to be done.

- As an antiemetic in individuals after receiving anticancer agents because of the high risk of vomiting [10]. As one can see, these off-label uses of the agent are an advantage for this drug, although nobody knows exactly how this agent cures all these different morbidities.

Discussion:

| Antipsychotic agent | Weight gain risk |

|---|---|

| Haloperidol | Low |

| Ziprasidone | Low |

| Lurasidone | Low |

| Aripiprazole | Low |

| Amisulpride | Low |

| Asenapine | Low |

| Paliperidone | Medium |

| Risperidone | Medium |

| Quetiapine | Medium |

| Chlorpromazine | Medium/high |

| Clozapine | High |

| Olanzapine | High |

| SN | Type of drug | Examples | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Anti-diabetic drugs | |||

| Insulin (hormone) | Circulating insulin is an anabolic hormone. In type 2 diabetes, the induced weight gain is due to a reduction in the signaling of satiety to the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. |

[92, 105 & 106]. | ||

| Sulfonylurea agents, such as glyburide, glipizide, and glimepiride | These increase endogenous insulin levels. | 105 & 108]. | ||

| Thiazolidinediones, such as pioglitazone & rosiglitazone | They induce weight gain due to fluid retention, the promotion of lipid storage, and adipogenesis through the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). | [91, 97 & 112]. | ||

| 2. | Antihypertensive drugs | |||

|

Beta-blockers, such as propranolol and atenolol. |

These affect body weight through two main mechanisms: 1) reductions in total energy expenditure through lowering of the basal metabolic rate and thermogenic response to meals, and 2) inhibition of lipolysis in response to adrenergic stimulation. Moreover, these agents can promote fatigue and reductions in patient activity. | [99, 104 & 111]. | ||

| Calcium channel blockers, such as Flunarizine | Body weight gain is linked to its blocking effects on calcium channels and dopamine receptors. | [101 & 109]. | ||

| 3. | Drugs acting on CNS | |||

|

Antipsychotics |

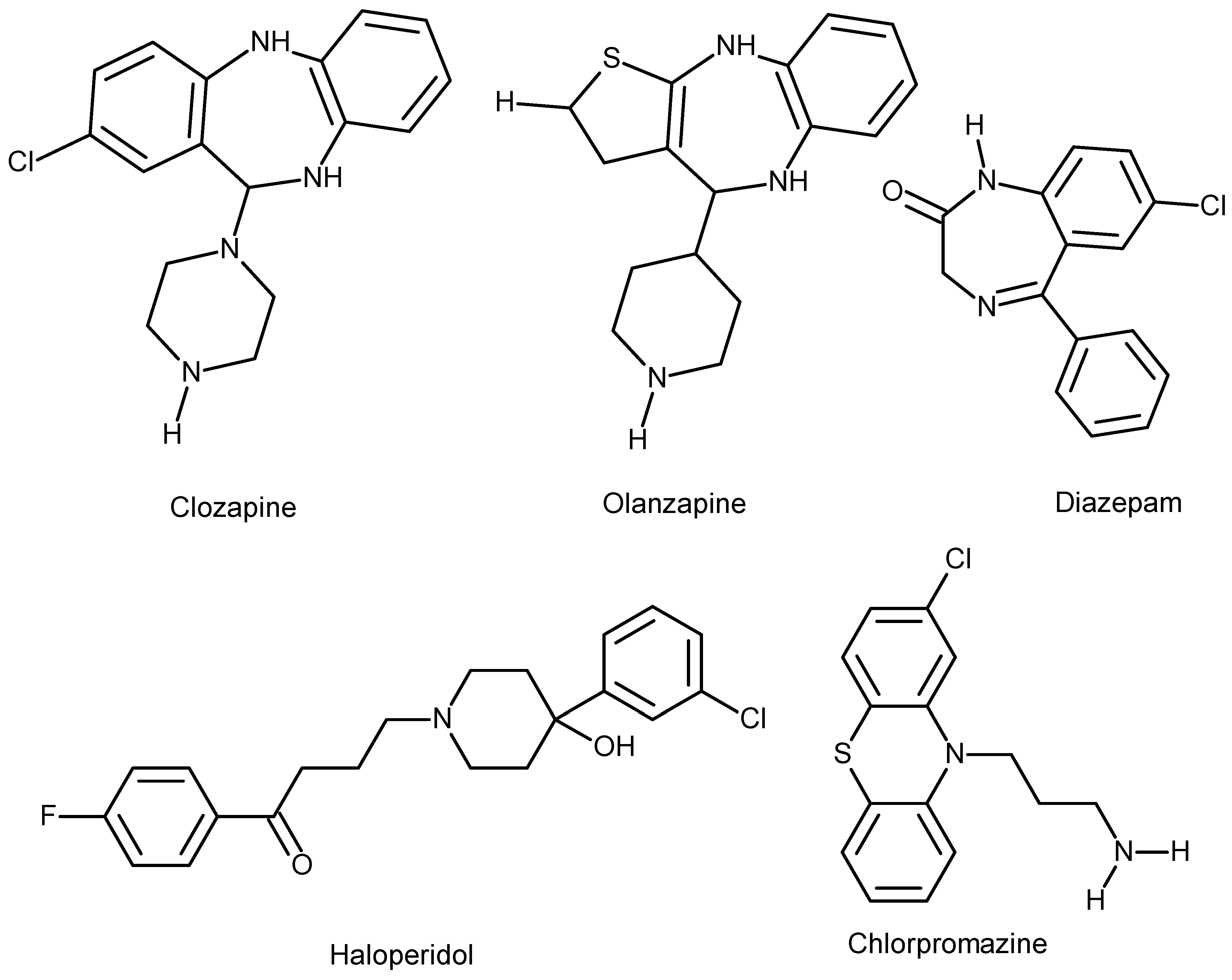

Olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine, quetiapine, risperidone, and paliperidone. | [42]. | ||

|

Anticonvulsants, such as: Valproate, carbamazepine, pregabalin and gabapentin |

Valproate causes weight gain through: 1) Central mechanism: via interactions with appetite-regulating neuropeptides and cytokines within the hypothalamus, as well as effects on energy expenditure 2) Peripheral actions: perturbation of glucose and lipid metabolism that contribute to weight-independent worsening of insulin resistance and risk for type 2 diabetes. |

[94 & 110]. | ||

|

Mood stabilizers: lithium |

The possible mechanisms include: 1) direct effect on hypothalamic centers that control appetite, increased thirst, and increased intake of high-calorie drinks, changes in food preference, 2) its influence on thyroid function with increased incidence of hypothyroidism. | [95 & 100]. | ||

| Sulpiride | It blocks 1) D2 dopamine receptors in the lateral hypothalamus are involved in satiety. 2) It also blocks the pituitary D2 receptors involved in the inhibition of prolactin secretion, which results in hyperprolactinemia, creating a condition similar to a functional ovariectomy, which in turn induces hyperphagia and weight gain. |

[93, 105 & 108]. | ||

| Antidepressants | TCA: Amitriptyline and Nortriptyline |

1) Block different classes of histamine receptors. 2) Interfere with the reuptake of serotonin, which controls appetite, and increases craving for carbohydrate-rich food. 3) They cause hypoglycemia by increasing circulating blood insulin, inducing insulin resistance. |

[103 & 107]. | |

|

Serotonin agents: 1) SSRIs such as citalopram, fluoxetine, and sertraline. 2) SNRIs: such as venlafaxine and duloxetine |

Indeed, these are associated with a slight weight loss to start with, but, with prolonged therapy, many of these agents have been shown to cause weight gain in individuals who use them for treatment. | [102 & 107]. | ||

| 4. | Endocrine agents | |||

| Glucocorticoids: | these may induce an increase in food intake and dietary preference for high-calorie, high-fat (comfort foods) through changes in the activity of AMP-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus. | [83 & 98]. |

Conclusion

Funding

Abbreviations

References

- Kessler, R.C., et al., Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2005. 62(6): p. 593-602. [CrossRef]

- Brunton, L.; Chabner, B.; Knollmann, B. Goodman and Gillman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th Ed. 2010. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN: 978-0-07-16244-8.

- Oruch R. Psychosis and Antipsychotics: A Short Résumé. Austin J Pharmacol Ther. 2014; 2 (7).3.

- Mann SK; Marawah R. Chlorpromazine. 2022 May 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. PMID: 31971720.

- https://reference.medscape.com/drug/zyprexa-relprevv-olanzapine-342979.

- Attia, E., et al., Olanzapine Versus Placebo in Adult Outpatients With Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Psychiatry, 2019. 176(6): p. 449-456. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, R.J., C. Bassel, and P. Sandor, Olanzapine in the treatment of aggression and tics in children with Tourette's syndrome--a pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol, 2004. 14(2): p. 255-66. [CrossRef]

- Tural Hesapcioglu, S., et al., Olanzapine, risperidone, and aripiprazole use in children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2020. 72: p. 101520. [CrossRef]

- Khaledi-Paveh B, Maazinezhad S, Rezaie L, Khazaie H. Treatment of chronic insomnia with atypical antipsychotics: results from a follow-up study. Sleep Sci. 2021 Jan-Mar;14(1):27-32. PMID: 34104334; PMCID: PMC8157779.

- Saudemont, G., et al., The use of olanzapine as an antiemetic in palliative medicine: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Palliat Care, 2020. 19(1): p. 56. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y., H.L. Chen, and L.P. Feng, Maternal obesity and the risk of neural tube defects in offspring: A meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract, 2017. 11(2): p. 188-197. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S. and R.K. Chadda, Teratogenicity with olanzapine. Indian J Psychol Med, 2014. 36(1): p. 91-3. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.A., et al., Maternal obesity and risk of neural tube defects: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2008. 198(6): p. 611-9.

- Uguz F. A New Safety Scoring System for the Use of Psychotropic Drugs During Lactation. Am J Ther. 2021 Jan-Feb 01;28(1):e118-e126. PMID: 30601177. [CrossRef]

- Caution with olanzapine use in dementia. Aust Prescr. 2021 Apr;44(2):40. Epub 2021 Apr 1. PMID: 33911330; PMCID: PMC8075751. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, E.Y., et al., Effect of atypical antipsychotics on body weight in geriatric psychiatric inpatients. SAGE Open Med, 2017. 5: p. 2050312117708711. [CrossRef]

- McCormack, P.L., Olanzapine: in adolescents with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder. CNS Drugs, 2010. 24(5): p. 443-52.

- Tural Hesapcioglu, S., et al., Frequency and Correlates of Acute Dystonic Reactions After Antipsychotic Initiation in 441 Children and Adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol, 2020. 30(6): p. 366-375. [CrossRef]

- Lexi-Comp Inc. (2010). Lexi-Comp Drug Information Handbook (19th North American ed.). Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp Inc. ISBN 978-1-59195-278-7.

- Leong, I., Neuropsychiatric disorders: Side effects of olanzapine worsened by metabolic dysfunction. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2018. 14(3): p. 129.

- Schwenger, E., J. Dumontet, and M.H. Ensom, Does olanzapine warrant clinical pharmacokinetic monitoring in schizophrenia? Clin Pharmacokinet, 2011. 50(7): p. 415-28. [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan Oruch, Ian F Pryme, Anders Lund. The Ideal Antipsychotic: Hybrid between Typical Haloperidol And the Atypical Clozapine Antipsychotic. Journal of Bioanalysis & Biomedicine, 2015, 07, ⟨10.4172/1948-593x.1000134⟩. ⟨hal-04023320⟩.

- Chen, J., et al., Molecular Mechanisms of Antipsychotic Drug-Induced Diabetes. Front Neurosci, 2017. 11: p. 643. [CrossRef]

- Alevizos, B., C. Papageorgiou, and G.N. Christodoulou, Obsessive-compulsive symptoms with olanzapine. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 2004. 7(3): p. 375-7.

- Kulkarni, G., J.C. Narayanaswamy, and S.B. Math, Olanzapine induced de-novo obsessive compulsive disorder in a patient with schizophrenia. Indian J Pharmacol, 2012. 44(5): p. 649-50. [CrossRef]

- Lykouras, L., et al., Olanzapine and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 2000. 10(5): p. 385-7.

- Luedecke, D., et al., Post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome in patients treated with olanzapine pamoate: mechanism, incidence, and management. CNS Drugs, 2015. 29(1): p. 41-6. [CrossRef]

- Kontaxakis, V.P., et al., Olanzapine-associated neuroleptic malignant syndrome: Is there an overlap with the serotonin syndrome? Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 2003. 2(1): p. 10. [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, M.A., et al., A Method for Tapering Antipsychotic Treatment That May Minimize the Risk of Relapse. Schizophr Bull, 2021. 47(4): p. 1116-1129. [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, J.T., et al., Olanzapine. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile. Clin Pharmacokinet, 1999. 37(3): p. 177-93.

- Diazepam/olanzapine/valproate semisodium interaction. Reactions Weekly, 2012. 1384(1): p. 23-23.

- Rao, M.L., et al., [Olanzapine: pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic drug monitoring]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr, 2001. 69(11): p. 510-7.

- O'Malley, G.F., et al., Olanzapine overdose mimicking opioid intoxication. Ann Emerg Med, 1999. 34(2): p. 279-81. [CrossRef]

- Michie, P.T., et al., The neurobiology of MMN and implications for schizophrenia. Biol Psychol, 2016. 116: p. 90-7. [CrossRef]

- Dayabandara, M., et al., Antipsychotic-associated weight gain: management strategies and impact on treatment adherence. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2017. 13: p. 2231-2241. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S., M. Bhargava, and S. Gautam, Weight gain with olanzapine: Drug, gender, or age? Indian J Psychiatry, 2006. 48(1): p. 39-42. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shachar, D., Mitochondrial multifaceted dysfunction in schizophrenia; complex I as a possible pathological target. Schizophr Res, 2017. 187: p. 3-10. [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, J.C., et al., Association of prescription H1 antihistamine use with obesity: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2010. 18(12): p. 2398-400. [CrossRef]

- Speyer, H., et al., Reversibility of Antipsychotic-Induced Weight Gain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2021. 12: p. 577919. [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, K., K. Yamamuro, and T. Kishimoto, Reversal of olanzapine-induced weight gain in a patient with schizophrenia by switching to asenapine: a case report. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2017. 13: p. 2837-2840. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., et al., Increased Appetite Plays a Key Role in Olanzapine-Induced Weight Gain in First-Episode Schizophrenia Patients. Front Pharmacol, 2020. 11: p. 739. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, P. "Antipsychotic medication and weight gain". March 31, 2017. https://bap.org.uk/articles/antipsychotic-medication-and-weight-gain/.

- Maurer, I.C., P. Schippel, and H.P. Volz, Lithium-induced enhancement of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in human brain tissue. Bipolar Disord, 2009. 11(5): p. 515-22. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G. and S.K. Kulkarni, Studies on modulation of feeding behavior by atypical antipsychotics in female mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2002. 26(2): p. 277-85. [CrossRef]

- Zai, C.C., et al., Association study of GABAA alpha2 receptor subunit gene variants in antipsychotic-associated weight gain. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 2015. 35(1): p. 7-12. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zoairy, R., et al., Serotonin improves glucose metabolism by Serotonylation of the small GTPase Rab4 in L6 skeletal muscle cells. Diabetol Metab Syndr, 2017. 9: p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.E., et al., Inhibition of mouse brown adipocyte differentiation by second-generation antipsychotics. Exp Mol Med, 2012. 44(9): p. 545-53. [CrossRef]

- Sertie, A.L., et al., Effects of antipsychotics with different weight gain liabilities on human in vitro models of adipose tissue differentiation and metabolism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2011. 35(8): p. 1884-90. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., E. Kutscher, and G.E. Davies, Berberine inhibits SREBP-1-related clozapine and risperidone induced adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Phytother Res, 2010. 24(12): p. 1831-8.

- Engl, J., et al., Olanzapine impairs glycogen synthesis and insulin signaling in L6 skeletal muscle cells. Mol Psychiatry, 2005. 10(12): p. 1089-96. [CrossRef]

- Chintoh, A.F., et al., Insulin resistance following continuous, chronic olanzapine treatment: an animal model. Schizophr Res, 2008. 104(1-3): p. 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Albaugh, V.L., et al., Olanzapine promotes fat accumulation in male rats by decreasing physical activity, repartitioning energy and increasing adipose tissue lipogenesis while impairing lipolysis. Mol Psychiatry, 2011. 16(5): p. 569-81. [CrossRef]

- Houseknecht, K.L., et al., Acute effects of atypical antipsychotics on whole-body insulin resistance in rats: implications for adverse metabolic effects. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2007. 32(2): p. 289-97. [CrossRef]

- Kowalchuk, C., et al., In male rats, the ability of central insulin to suppress glucose production is impaired by olanzapine, whereas glucose uptake is left intact. J Psychiatry Neurosci, 2017. 42(6): p. 424-431. [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M., et al., Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Psychiatry, 2009. 24(6): p. 412-24. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.J., et al., BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol, 2016. 30(8): p. 717-48. [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, J.P., et al., Efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison. Am J Psychiatry, 2007. 164(7): p. 1050-60.

- Paik, J., Olanzapine/Samidorphan: First Approval. Drugs, 2021. 81(12): p. 1431-1436. [CrossRef]

- de Silva, V.A., et al., Metformin in prevention and treatment of antipsychotic induced weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 2016. 16(1): p. 341.

- Martins, P.J., M. Haas, and S. Obici, Central nervous system delivery of the antipsychotic olanzapine induces hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes, 2010. 59(10): p. 2418-25. [CrossRef]

- Yang, N., et al., Insulin Resistance-Related Proteins Are Overexpressed in Patients and Rats Treated With Olanzapine and Are Reverted by Pueraria in the Rat Model. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 2019. 39(3): p. 214-219. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L., et al., Insulin resistance induced by olanzapine and other second-generation antipsychotics in Chinese patients with schizophrenia: a comparative review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 2019. 75(12): p. 1621-1629.

- Aedh, A.I., et al., A Glimpse into Milestones of Insulin Resistance and an Updated Review of Its Management. Nutrients, 2023. 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Kato, T., Neurobiological basis of bipolar disorder: Mitochondrial dysfunction hypothesis and beyond. Schizophr Res, 2017. 187: p. 62-66. [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, A., et al., Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: pathways, mechanisms and implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2015. 48: p. 10-21. [CrossRef]

- Scaglia, F., The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in psychiatric disease. Dev Disabil Res Rev, 2010. 16(2): p. 136-43. [CrossRef]

- Tobe, E.H., Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2013. 9: p. 567-73. [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, A., et al., Metabolic Syndrome and Antipsychotics: The Role of Mitochondrial Fission/Fusion Imbalance. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2018. 9: p. 144. [CrossRef]

- Geddes, J., Generating evidence to inform policy and practice: the example of the second generation "atypical" antipsychotics. Schizophr Bull, 2003. 29(1): p. 105-14. [CrossRef]

- Monasterio, E. and D. Gleeson, Pharmaceutical industry behaviour and the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement. N Z Med J, 2014. 127(1389): p. 6-12.

- Clay, H.B., S. Sillivan, and C. Konradi, Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci, 2011. 29(3): p. 311-24. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shachar, D. and D. Laifenfeld, Mitochondria, synaptic plasticity, and schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol, 2004. 59: p. 273-96.

- Iwata, K., Mitochondrial Involvement in Mental Disorders; Energy Metabolism, Genetic, and Environmental Factors, in Pre-Clinical Models: Techniques and Protocols, P.C. Guest, Editor. 2019, Springer New York: New York, NY. p. 41-48.

- Manji, H.K., et al., The underlying neurobiology of bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry, 2003. 2(3): p. 136-46.

- Ross, C.A., et al., Neurobiology of schizophrenia. Neuron, 2006. 52(1): p. 139-53.

- Scaini, G., et al., Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder: Evidence, pathophysiology and translational implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2016. 68: p. 694-713. [CrossRef]

- Robicsek, O., et al., Isolated Mitochondria Transfer Improves Neuronal Differentiation of Schizophrenia-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Rescues Deficits in a Rat Model of the Disorder. Schizophr Bull, 2018. 44(2): p. 432-442. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. and H.K. Manji, The extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway: an emerging promising target for mood stabilizers. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 2006. 19(3): p. 313-23. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, H., et al., Lithium prevents cell apoptosis through autophagy induction. Bratisl Lek Listy, 2018. 119(4): p. 234-239. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S., et al., Lithium induces autophagy by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. J Cell Biol, 2005. 170(7): p. 1101-11. [CrossRef]

- Scaini, G., et al., Second generation antipsychotic-induced mitochondrial alterations: Implications for increased risk of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 2018. 28(3): p. 369-380. [CrossRef]

- Vucicevic, L., et al., Autophagy inhibition uncovers the neurotoxic action of the antipsychotic drug olanzapine. Autophagy, 2014. 10(12): p. 2362-78. [CrossRef]

- Singh, O.P., et al., A comparative study of oxidative stress and interrelationship of important antioxidants in haloperidol and olanzapine treated patients suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry, 2008. 50(3): p. 171-6. [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan Oruch., et al. “Quetiapine: An Objective Evaluation of Pharmacology, Clinical Uses and Intoxication”. EC Pharmacology and Toxicology 8.4 (2020): 01-26.

- Bar-Yosef, T., et al., Mitochondrial function parameters as a tool for tailored drug treatment of an individual with psychosis: a proof of concept study. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 12258. [CrossRef]

- Chouinard, G., et al., Antipsychotic-Induced Dopamine Supersensitivity Psychosis: Pharmacology, Criteria, and Therapy. Psychother Psychosom, 2017. 86(4): p. 189-219. [CrossRef]

- Seeman, P., All roads to schizophrenia lead to dopamine supersensitivity and elevated dopamine D2(high) receptors. CNS Neurosci Ther, 2011. 17(2): p. 118-32. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L., et al., Antipsychotic Withdrawal Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry, 2020. 11: p. 569912. [CrossRef]

- Dilsaver, S.C. and N.E. Alessi, Antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms: phenomenology and pathophysiology. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 1988. 77(3): p. 241-6. [CrossRef]

- Lacoursiere, R.B., H.E. Spohn, and K. Thompson, Medical effects of abrupt neuroleptic withdrawal. Compr Psychiatry, 1976. 17(2): p. 285-94. [CrossRef]

- Aleman-Gonzalez-Duhart, D., et al., Current Advances in the Biochemical and Physiological Aspects of the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus with Thiazolidinediones. PPAR Res, 2016. 2016: p. 7614270. [CrossRef]

- Allison, D.B., et al., Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry, 1999. 156(11): p. 1686-96. [CrossRef]

- Banini, B.A. and A.J. Sanyal, Current and future pharmacologic treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2017. 33(3): p. 134-141. [CrossRef]

- Belcastro, V., et al., Metabolic and endocrine effects of valproic acid chronic treatment. Epilepsy Res, 2013. 107(1-2): p. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. and T. Silverstone, Lithium and weight gain. Int Clin Psychopharmacol, 1990. 5(3): p. 217-25. [CrossRef]

- Christ-Crain, M., et al., AMP-activated protein kinase mediates glucocorticoid-induced metabolic changes: a novel mechanism in Cushing's syndrome. FASEB J, 2008. 22(6): p. 1672-83. [CrossRef]

- Cignarelli, A., F. Giorgino, and R. Vettor, Pharmacologic agents for type 2 diabetes therapy and regulation of adipogenesis. Arch Physiol Biochem, 2013. 119(4): p. 139-50. [CrossRef]

- Harfstrand, A., et al., Regional differences in glucocorticoid receptor immunoreactivity among neuropeptide Y immunoreactive neurons of the rat brain. Acta Physiol Scand, 1989. 135(1): p. 3-9. [CrossRef]

- Koch, G., I.W. Franz, and F.W. Lohmann, Effects of short-term and long-term treatment with cardio-selective and non-selective beta-receptor blockade on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and on plasma catecholamines at rest and during exercise. Clin Sci (Lond), 1981. 61 Suppl 7: p. 433s-435s. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, C. and H. Rampes, Lithium: a review of its metabolic adverse effects. J Psychopharmacol, 2006. 20(3): p. 347-55. [CrossRef]

- Manconi, F.M., et al., Behavioural And Biochemical Effects Of Flunarizine On The Dopaminergic System In Rodents. Cephalalgia, 1987. 7(6_suppl): p. 420-421. [CrossRef]

- Masand, P.S. and S. Gupta, Long-term side effects of newer-generation antidepressants: SSRIS, venlafaxine, nefazodone, bupropion, and mirtazapine. Ann Clin Psychiatry, 2002. 14(3): p. 175-82. [CrossRef]

- Nakra, B.R., et al., Amitriptyline and weight gain: a biochemical and endocrinological study. Curr Med Res Opin, 1977. 4(8): p. 602-6. [CrossRef]

- Newsom, S.A., et al., Short-term sympathoadrenal inhibition augments the thermogenic response to beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation. J Endocrinol, 2010. 206(3): p. 307-15. [CrossRef]

- Russell-Jones, D. and R. Khan, Insulin-associated weight gain in diabetes--causes, effects and coping strategies. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2007. 9(6): p. 799-812.

- Seeman, P., et al., Antipsychotic drug doses and neuroleptic/dopamine receptors. Nature, 1976. 261(5562): p. 717-9. [CrossRef]

- Serretti, A. and L. Mandelli, Antidepressants and body weight: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry, 2010. 71(10): p. 1259-72.

- Van Gaal, L. and A. Scheen, Weight management in type 2 diabetes: current and emerging approaches to treatment. Diabetes Care, 2015. 38(6): p. 1161-72.

- Vecsei, L., et al., Drug safety and tolerability in prophylactic migraine treatment. Expert Opin Drug Saf, 2015. 14(5): p. 667-81. [CrossRef]

- Verrotti, A., et al., Weight gain following treatment with valproic acid: pathogenetic mechanisms and clinical implications. Obes Rev, 2011. 12(5): p. e32-43. [CrossRef]

- Welle, S., R.G. Schwartz, and M. Statt, Reduced metabolic rate during beta-adrenergic blockade in humans. Metabolism, 1991. 40(6): p. 619-22. [CrossRef]

- Wilding, J., Thiazolidinediones, insulin resistance and obesity: Finding a balance. Int J Clin Pract, 2006. 60(10): p. 1272-80. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).