Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

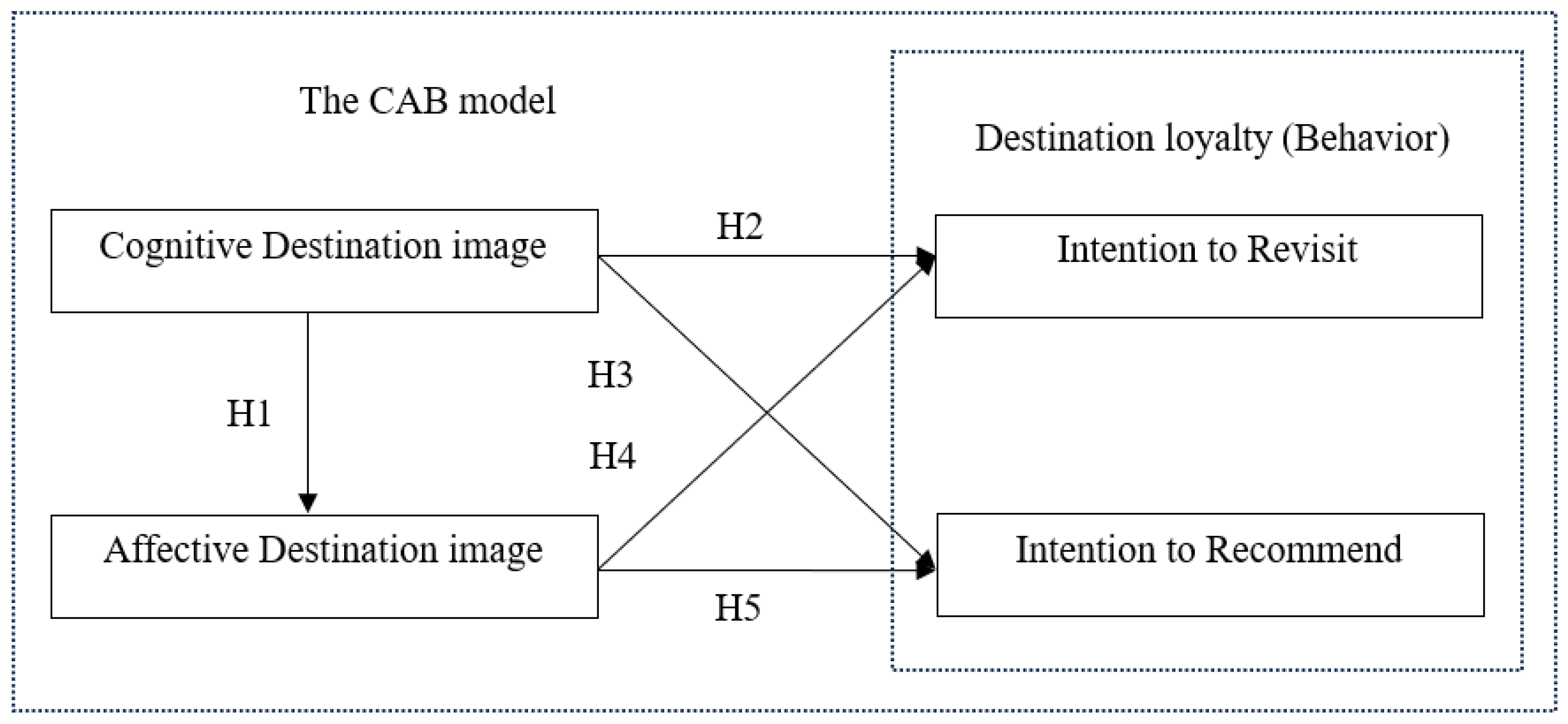

2.1. The CAB Model

2.2. Destination Image

2.3. Destination Loyalty

2.4. Revisit Intention

2.5. Intention to Recommend (WOM)

3. Methodology

3.1. Instrument Development

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. The PLS-SEM Model Assessment

4.2.1. Measurement Model Assessment and Measurement of Invariance

| Relationship between constructs | VIF |

|---|---|

| Cognitive image -> Affective image | 1.000 |

| Cognitive image -> Intention to revisit | 1.367 |

| Cognitive image -> Intention to recommend | 1.367 |

| Affective image -> Intention to revisit | 1.367 |

| Affective image -> Intention to recommend | 1.367 |

| Constructs or associated items | Loadings | Cronbach’s alpha | CR | AVE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-time | Repeat | First-time | Repeat | First-time | Repeat | First-time | Repeat | |

| CO | 0.767 | 0.81 | 0.769 | 0812 | 0.683 | 0.725 | ||

| CO 2 | 0.858 | 0.851 | ||||||

| CO 1 | 0.844 | 0.855 | ||||||

| CO 3 | 0.774 | 0.848 | ||||||

| AF | 0.827 | 0.846 | 0.832 | 0.853 | 0.594 | 0.618 | ||

| AF2 | 0.836 | 0.819 | ||||||

| AF5 | 0.824 | 0.771 | ||||||

| AF1 | 0.748 | 0.814 | ||||||

| AF3 | 0.751 | 0.776 | ||||||

| AF4 | 0.684 | 0.749 | ||||||

| IV | 0.9 | 0.857 | 0.937 | 0.861 | 0.772 | 0.703 | ||

| IV1 | 0.873 | 0.747 | ||||||

| IV2 | 0.945 | 0.902 | ||||||

| IV3 | 0.938 | 0.882 | ||||||

| IV4 | 0.743 | 0.814 | ||||||

| IR | 0.922 | 0.926 | 0.922 | 0.928 | 0.812 | 0.82 | ||

| IR1 | 0.892 | 0.865 | ||||||

| IR2 | 0.939 | 0.931 | ||||||

| IR3 | 0.925 | 0.935 | ||||||

| IR4 | 0.846 | 0.889 | ||||||

4.2.2. Structural Model and MGA Assessment

5. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Implications

- Tailored marketing strategies should be developed to address first-time and repeat travellers’ unique perceptions and inspirations;

- Plans to endorse new attractions and inspire repeat visits should be created;

- Undated information should be provided to improve first-time travellers’ experiences and encourage their revisit intention;

- Loyalty programs or incentives should be developed to enhance repeat travellers’ emotional links to the destination.

5.3. Limitations of Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aburumman, A., Abou-Shouk, M., Zouair, N., & Abdel-Jalil, M. (2023). The effect of health-perceived risks on domestic travel intention: The moderating role of destination image. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14673584231172376. [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M., & Eshaghi, M. S. (2020a). Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 81, 104154. [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M., & Eshaghi, M. S. (2020b). Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 81, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A., & Han, H. (2019). Role of halal-friendly destination performances, value, satisfaction, and trust in generating destination image and loyalty. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 13, 51–60. [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. W. (1999). U.S. International Pleasure Travelers’ Images of Four Mediterranean Destinations: A Comparison of Visitors and Nonvisitors. Journal of Travel Research, 38(2), 144–152. [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A. E. (2020). Sampling Methods. 36(2), 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M. A. M. (2022). Factors affecting future travel intentions: Awareness, image, past visitation and risk perception. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(3), 761–778. [CrossRef]

- Casali, G. L., Liu, Y., Presenza, A., & Moyle, C.-L. (2021). How does familiarity shape destination image and loyalty for visitors and residents? Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27(2), 151–167. [CrossRef]

- Cham, T.-H., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., & Memon, M. A. (2022). Will destination image drive the intention to revisit and recommend? Empirical evidence from golf tourism. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 23(2), 385–409. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. (2022). Can smart tourism technology enhance destination image? The case of the 2018 Taichung World Flora Exposition. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 13(4), 590–607. [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.-H., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Ramayah, T., & Ting, H. (2018). Convergent validity assessment of formatively measured constructs in PLS-SEM: On using single-item versus multi-item measures in redundancy analyses. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(11), 3192–3210. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N. (Chris), Dwyer, L., & Firth, T. (2018). Residents’ place attachment and word-of-mouth behaviours: A tale of two cities. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-F., & Law, R. (2016). A Review of Research on Electronic Word-of-Mouth in Hospitality and Tourism Management. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 17(4), 347–372. [CrossRef]

- Cubillas-Para, C., Cegarra-Navarro, J. G., & Tomaseti-Solano, E. (2023). Linking unlearning with the intention to recommend through destination image. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 9(2), 394–410. [CrossRef]

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. [CrossRef]

- Deng, X., & Yu, Z. (2023). A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of the Effect of Chatbot Technology Use in Sustainable Education. Sustainability, 15(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S., & Ring, A. (2014). Tourism marketing research: Past, present and future. Annals of Tourism Research, 47, 31–47. [CrossRef]

- Erawan, T. (2020). India’s destination image and loyalty perception in Thailand. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6(3), 565–582. [CrossRef]

- F. Hair Jr, J., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & G. Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., & Timothy, D. J. (2021). Social media constraints and destination images: The potential of barrier-free internet access for foreign tourists in an internet-restricted destination. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100771. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., & Pesonen, J. A. (2022). The role of online travel reviews in evolving tourists’ perceived destination image. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 22(4–5), 372–392. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. L., King, K. W., & Ramirez, A. (2016). Brands, Friends, & Viral Advertising: A Social Exchange Perspective on the Ad Referral Processes. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 36(1), 31–45. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195–204.

- Jeong, C., & Holland, S. (2012). Destination Image Saturation. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 29(6), 501–519. [CrossRef]

- Kani, Y., Aziz, Y. A., Sambasivan, M., & Bojei, J. (2017). Antecedents and outcomes of destination image of Malaysia. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 32, 89–98. [CrossRef]

- Kanwel, S., Lingqiang, Z., Asif, M., Hwang, J., Hussain, A., & Jameel, A. (2019). The Influence of Destination Image on Tourist Loyalty and Intention to Visit: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability, 11(22), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H., Wang, Y., & Song, H. (2021). Understanding the causes of negative tourism experiences. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(3), 304–320. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S., Thapa, B., & Kim, H. (2017). International Tourists’ Perceived Sustainability of Jeju Island, South Korea. Sustainability, 10(2), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G. (2012). Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance-Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580. [CrossRef]

- Krause, R. M., Fatemi, S. M., Nguyen Long, L. A., Arnold, G., & Hofmeyer, S. L. (2023). What is the Future of Survey-Based Data Collection for Local Government Research? Trends, Strategies, and Recommendations. Urban Affairs Review, 10780874231175837.

- Lam, J. M. S., Makhbul, Z. K. M., Aziz, N. A., & Ahmat, M. A. H. (2024). Incorporating multidimensional images into cultural heritage destination: Does it help to explain and analyse better? Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 14(4), 563–580. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. W., & Xue, K. (2020). A model of destination loyalty: Integrating destination image and sustainable tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(4), 393–408. [CrossRef]

- Lentz, M., Berezan, O., & Raab, C. (2022). Uncovering the relationship between revenue management and hotel loyalty programs. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 21(3), 306–320. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Lv, X., & Scott, M. (2023). Understanding the dynamics of destination loyalty: A longitudinal investigation into the drivers of revisit intentions. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(2), 323–340. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Liu, Y., Dai, S., & Chen, M. (2022). A review of tourism and hospitality studies on behavioural economics. Tourism Economics, 28(3), 843–859. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X., & Xue, J. (2021). Mediating effect of destination image on the relationship between risk perception of smog and revisit intention: A case of Chengdu. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(9), 1024–1037. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. K., Wu, W. Y., Truong, G. N. T., Binh, P. N. M., & Van Vu, V. (2021). A model of destination consumption, attitude, religious involvement, satisfaction, and revisit intention. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27(3), 330–345. [CrossRef]

- Lifshitz, H. (2020). The Triple CAB Model: Enhancing Cognition, Affect, and Behavior in Adults with Intellectual Disability. In H. Lifshitz (Ed.), Growth and Development in Adulthood among Persons with Intellectual Disability: New Frontiers in Theory, Research, and Intervention (pp. 53–82). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-W., & Tsao, H.-C. (2023). Exploring First-Time and Repeat Volunteer Scuba Divers’ Environmentally Responsible Behaviors Based on the C-A-B Model. Sustainability, 15(14), 11425. [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S. W., Goldsmith, R. E., & Pan, B. (2008). Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tourism Management, 29(3), 458–468. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Li, J., & Fu, Y. (2016). Antecedents of Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions: The Role and Influence of Tourists’ Perceived Freedom of Choice, Destination Image, and Satisfaction. Tourism Analysis, 21(6), 577–588. [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S. M. C., Stylos, N., & Bellou, V. (2021). Destination atmospheric cues as key influencers of tourists’ word-of-mouth communication: Tourist visitation at two Mediterranean capital cities. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(1), 85–108. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L., Jiao, M., & Weng, L. (2023). Influence of First-Time Visitors’ Perceptions of Destination Image on Perceived Value and Destination Loyalty: A Case Study of Grand Canal Forest Park, Beijing. Forests, 14(3), 504. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Li, F. (Sam), & Shang, Y. (2022). Tourist scams, moral emotions and behaviors: Impacts on moral emotions, dissatisfaction, revisit intention and negative word of mouth. Tourism Review, 77(5), 1299–1321. [CrossRef]

- Maghrifani, D., Liu, F., & Sneddon, J. (2022). Understanding Potential and Repeat Visitors’ Travel Intentions: The Roles of Travel Motivations, Destination Image, and Visitor Image Congruity. Journal of Travel Research, 61(5), 1121–1137. [CrossRef]

- Manley, S. C., Hair, J. F., Williams, R. I., & McDowell, W. C. (2021). Essential new PLS-SEM analysis methods for your entrepreneurship analytical toolbox. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(4), 1805–1825. [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A., Ayadi, K., Lee, S. (Ally), Chiang, L., & Tang, L. (Rebecca). (2017). Exploring the roles of self-concept and future memory at consumer events: The application of an extended Mehrabian–Russell model. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(4), 531–543. [CrossRef]

- Munanura, I. E., Parada, J. A., & Kline, J. D. (2024). A cognitive appraisal theory perspective of residents’ support for tourism. Journal of Ecotourism, 23(3), 308–327. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, H., Omar, B., & Mukhiar, S. N. S. (2020). Measuring destination competitiveness: An importance-performance analysis (IPA) of six top island destinations in South East Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(3), 223–243. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T. T., & Duong, T. D. H. (2024a). The role of nostalgic emotion in shaping destination image and behavioral intentions – An empirical study. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T. T., & Duong, T. D. H. (2024b). The role of nostalgic emotion in shaping destination image and behavioral intentions – An empirical study. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 8(2), 735–752. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R., Ramkissoon, H., & Gursoy, D. (2013). Use of Structural Equation Modeling in Tourism Research: Past, Present, and Future. Journal of Travel Research, 52(6), 759–771. [CrossRef]

- Palau-Saumell, R., Forgas-Coll, S., Amaya-Molinar, C. M., & Sánchez-García, J. (2016). Examining how country image influences destination image in a behavioral intentions model: The cases of Lloret De Mar (Spain) and Cancun (Mexico). Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(7), 949–965. [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Muskat, B., & Del Chiappa, G. (2017). Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 41–54. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y., Zhou, Q., Guo, Y., & Yang, H. (2025). Differences in Destination Attachment Representations of First-Time and Repeat Tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 64(2), 360–377. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, K. M., Mewada, B. G., Kaur, S., & Qureshi, M. R. N. M. (2023). Assessing Lean 4.0 for Industry 4.0 Readiness Using PLS-SEM towards Sustainable Manufacturing Supply Chain. Sustainability, 15(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Chee, S. Y., & Ari Ragavan, N. (2023a). Tourists’ perceptions of the sustainability of destination, satisfaction, and revisit intention. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Chee, S. Y., & Ari Ragavan, N. (2023b). Tourists’ perceptions of the sustainability of destination, satisfaction, and revisit intention. Tourism Recreation Research, 0(0), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Rather, R. A., Hollebeek, L. D., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2022). First-Time versus Repeat Tourism Customer Engagement, Experience, and Value Cocreation: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Travel Research, 61(3), 549–564. [CrossRef]

- Ren, J., Su, K., Zhou, Y., Hou, Y., & Wen, Y. (2022). Why Return? Birdwatching Tourists’ Revisit Intentions Based on Structural Equation Modelling. Sustainability, 14(21), 14632. [CrossRef]

- Šagovnović, I., & Kovačić, S. (2021). Influence of tourists’ sociodemographic characteristics on their perception of destination personality and emotional experience of a city break destination. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(1), 200–223. [CrossRef]

- Schofield, P., Coromina, L., Camprubi, R., & Kim, S. (2020). An analysis of first-time and repeat-visitor destination images through the prism of the three-factor theory of consumer satisfaction. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Serra-Cantallops, A., Ramón Cardona, J., & Salvi, F. (2020). Antecedents of positive eWOM in hotels. Exploring the relative role of satisfaction, quality and positive emotional experiences. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(11), 3457–3477. [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. (2022). Exploring resident–tourist interaction and its impact on tourists’ destination image. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 186–201. [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D., Woosnam, K. M., Ivkov, M., & Kim, S. S. (2020). Destination loyalty explained through place attachment, destination familiarity and destination image. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(5), 604–616. [CrossRef]

- Stylos, N., Vassiliadis, C. A., Bellou, V., & Andronikidis, A. (2016). Destination images, holistic images and personal normative beliefs: Predictors of intention to revisit a destination. Tourism Management, 53, 40–60. [CrossRef]

- Tabaeeian, R. A., Yazdi, A., Mokhtari, N., & Khoshfetrat, A. (2023). Host-tourist interaction, revisit intention and memorable tourism experience through relationship quality and perceived service quality in ecotourism. Journal of Ecotourism, 22(3), 406–429. [CrossRef]

- Troiville, J., Moisescu, O. I., & Radomir, L. (2025). Using necessary condition analysis to complement multigroup analysis in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 82, 104018. [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, I. (2021). The relationship between IT affordance, flow experience, trust, and social commerce intention: An exploration using the SOR paradigm. Technology in Society, 65, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO]. (2024). Tourism Statistics Database. https://www.unwto.org/tourism-statistics/tourism-statistics-database.

- Wang, X., Qin, X., & Zhou, Y. (2020). A comparative study of relative roles and sequences of cognitive and affective attitudes on tourists’ pro-environmental behavioral intention. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(5), 727–746. [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R. A. (1987). Product/Consumption-Based Affective Responses and Postpurchase Processes. Journal of Marketing Research, 24, 258–270.

- Woosnam, K. M., Stylidis, D., & Ivkov, M. (2020). Explaining conative destination image through cognitive and affective destination image and emotional solidarity with residents. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(6), 917–935. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., He, Z., King, C., & Mattila, A. S. (2021). In darkness we seek light: The impact of focal and general lighting designs on customers’ approach intentions toward restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T., Ma, Y., & Kim, K. (2021). Telecom churn prediction system based on ensemble learning using feature grouping. Applied Sciences, 11(11), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N., Verma, S., & Chikhalkar, R. D. (2022). eWOM, destination preference and consumer involvement–a stimulus-organism-response (SOR) lens. Tourism Review, 77(4), 1135–1152. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B., & Katsumata, S. (2023). Sightseeing spot satisfaction of inbound tourists: Comparative analysis of first-time visitors and repeat visitors in Japan. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 9(1), 111–127. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., & Walsh, J. (2020). Tourist Experience, Tourist Motivation and Destination Loyalty for Historic and Cultural Tourists. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 28(4). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Wang, Y., & Ariffin, S. K. (2024). Keep scrolling: An investigation of short video users’ continuous watching behavior. Information & Management, 61(6), 104014. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Li, J., Liu, C.-H., Shen, Y., & Li, G. (2021). The effect of novelty on travel intention: The mediating effect of brand equity and travel motivation. Management Decision, 59(6), 1271–1290. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., & Yu, H. (2022). Exploring how tourist engagement affects destination loyalty: The intermediary role of value and satisfaction. Sustainability, 14(3), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Ng, S. I., & Deng, W. (2024). Why I revisit a historic town in Chengdu? Roles of cognitive image, affective image and memorable tourism experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 36(11), 2869–2888. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., & Li, L. (2023). The Influence of Decision-Making Logic on Employees’ Innovative Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Positive Error Orientation and the Moderating Role of Environmental Dynamics. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 2297–2313. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y., & Yu, Q. (2022). Sense of safety toward tourism destinations: A social constructivist perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 24, 100708. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-time travellers | Repeat travellers | First-time travellers | Repeat travellers | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 101 | 123 | 54.59 | 59.42 |

| Female | 84 | 84 | 45.41 | 40.58 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 76 | 79 | 41.08 | 38.16 |

| Married | 87 | 107 | 47.03 | 51.69 |

| Other | 22 | 21 | 11.89 | 10.14 |

| Age (Years) | ||||

| 19–25 | 48 | 29 | 25.95 | 1401 |

| 26–32 | 58 | 45 | 31.35 | 21.74 |

| 33–39 | 41 | 39 | 22.16 | 18.84 |

| 40–49 | 27 | 53 | 14.59 | 25.60 |

| ≥ 50 | 11 | 41 | 5.95 | 19.81 |

| Education Level | ||||

| High school or secondary | 43 | 46 | 23.24 | 22.22 |

| Vocational college | 10 | 20 | 5.41 | 9.66 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 76 | 72 | 41.08 | 34.78 |

| Master’s degree | 43 | 44 | 23.24 | 21.26 |

| Doctorate or PhD | 7 | 14 | 3.78 | 6.76 |

| Other | 6 | 11 | 3.24 | 5.31 |

| Income per month (USD) | ||||

| < 500 | 36 | 25 | 19.46 | 12.08 |

| 500 - 1000 | 56 | 38 | 30.27 | 18.36 |

| 1001 - 2000 | 29 | 58 | 15.68 | 28.02 |

| 2001 - 3000 | 30 | 43 | 16.22 | 20.77 |

| > 3000 | 34 | 43 | 18.38 | 20.77 |

| Constructs or associated items | First-time travellers | Repeat travellers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value | SD | Mean value | SD | ||

| Cognitive image (CO), I guess Thailand… | |||||

| CO1 | has a variety of outdoor activities | 4.28 | 0.762 | 4.21 | 0.726 |

| CO2 | has pleasant weather | 4.07 | 0.973 | 4.08 | 0.929 |

| CO3 | has plentiful cultural and historical sites | 4.02 | 0.824 | 4.14 | 0.756 |

| Affective image (AF), Thailand is… | |||||

| AF1 | a pleasant place | 4.44 | 0.597 | 4.38 | 0.670 |

| AF2 | a stimulating place | 4.05 | 0.812 | 4.02 | 0.812 |

| AF3 | an interesting place | 4.58 | 0.537 | 4.43 | 0.670 |

| AF4 | a comfortable place | 4.25 | 0.628 | 4.16 | 0.710 |

| AF5 | a exciting place | 4.29 | 0.765 | 4.06 | 0.825 |

| Intention to revisit (IV), In the future, | |||||

| IV1 | I intent to visit/revisit Thailand | 4.38 | 0.697 | 4.29 | 0.833 |

| IV2 | I will likely visit/revisit Thailand | 4.35 | 0.659 | 4.29 | 0.727 |

| IV3 | I am interested in visiting/revisiting Thailand | 4.39 | 0.659 | 4.35 | 0.735 |

| IV4 | Thailand will still be my choice travel destination | 4.19 | 0.795 | 4.19 | 0.865 |

| Intention to recommend (IR), In the future, | |||||

| IR1 | I am likely to recommend Thailand to those who want advice on travel | 4.45 | 0.589 | 4.37 | 0.731 |

| IR2 | I will willingly recommend visiting Thailand to others | 4.48 | 0.581 | 4.41 | 0.683 |

| IR3 | I will willingly encourage friends and family to visit Thailand | 4.46 | 0.571 | 4.35 | 0.747 |

| IR4 | I will willingly say positive things about Thailand | 4.48 | 0.553 | 4.41 | 0.690 |

| Hypothesis | Total | Multigroup hypothesis (H6) | First-time travellers | Repeat travellers | Path coefficient difference | Parametric test |

Welch-Satterthwaite test p-values |

Permutation test p-values |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path coefficient | t-values | Path coefficient | t-values | Path coefficient | t-values | |||||||

| H1 | CO -˃AF | 0.531*** | 12.828 | COF -˃ AFF ≠ COR -˃ AFR | 0.520*** | 8.726 | 0.557*** | 10.097 | -0.037 | 0.648 | 0.649 | 0.656 |

| H2 | CO -˃ IV | 0.021 | 0.426 | COF -˃ IVF ≠ COR -˃ IVR | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.035 | 0.539 | -0.038 | 0.697 | 0.696 | 0.654 |

| H3 | CO -˃ IR | 0.200*** | 4.306 | COF -˃ IRF ≠ COR -˃ IRR | 0.165** | 2.578 | 0.230*** | 3.593 | -0.067 | 0.462 | 0.461 | 0.487 |

| H4 | AF -˃ IV | 0.547*** | 10.543 | AFF -˃ IVF ≠ AFR -˃ IVR | 0.523*** | 7.727 | 0.569*** | 7.845 | -0.050 | 0.611 | 0.609 | 0.653 |

| H5 | AF -˃ IR | 0.479*** | 8.589 | AFF -˃ IR F≠ AFR -˃ IRR | 0.548*** | 7.925 | 0.424*** | 5.263 | 0.121 | 0.260 | 0.255 | 0.307 |

| Dependent variable | R2 | R2 | R2 | |||||||||

| AF | 28.00% | 26.80% | 30.80% | |||||||||

| IV | 31.10% | 26.80% | 34.90% | |||||||||

| IR | 37.00% | 41.90% | 34.30% | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).