Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

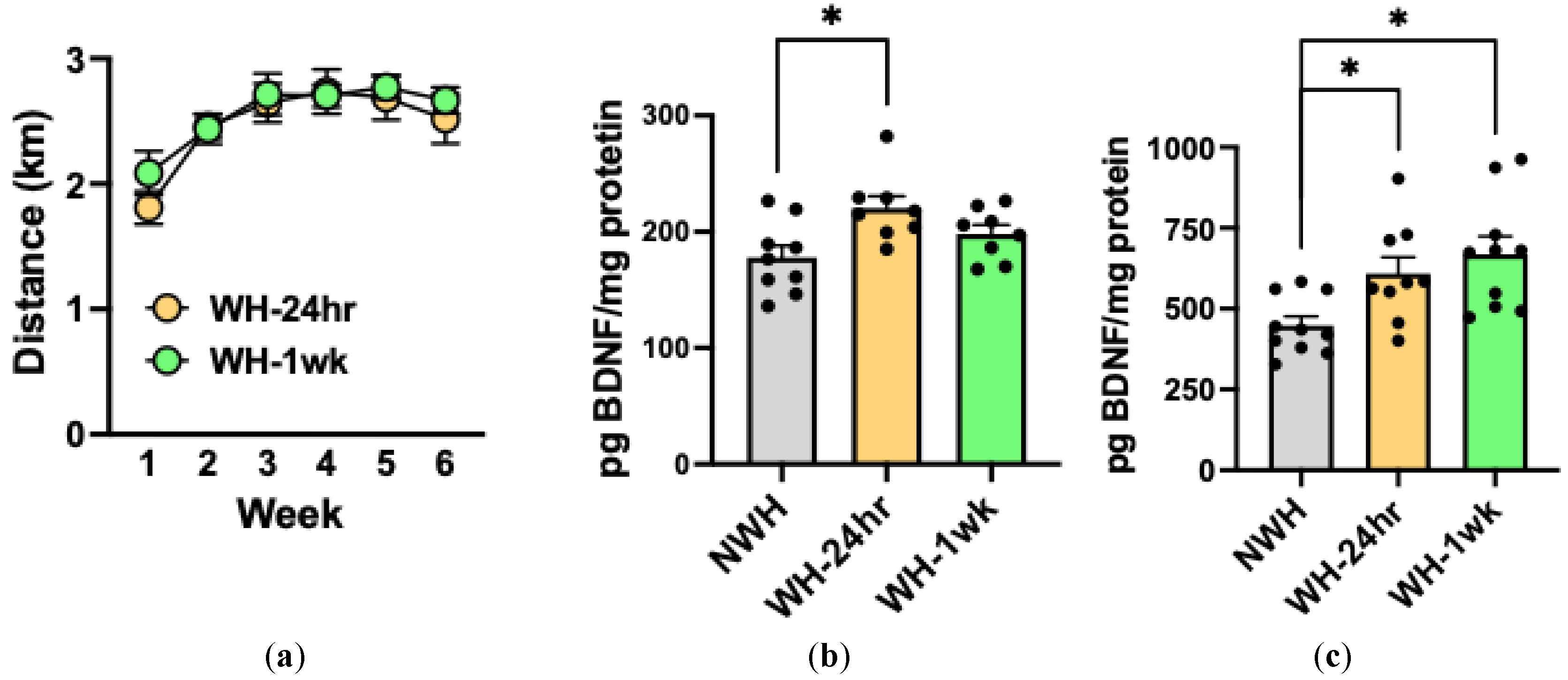

2.1. Limited Daily Access to Wheel-Running Increases BDNF Protein Expression in Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Dentate Gyrus

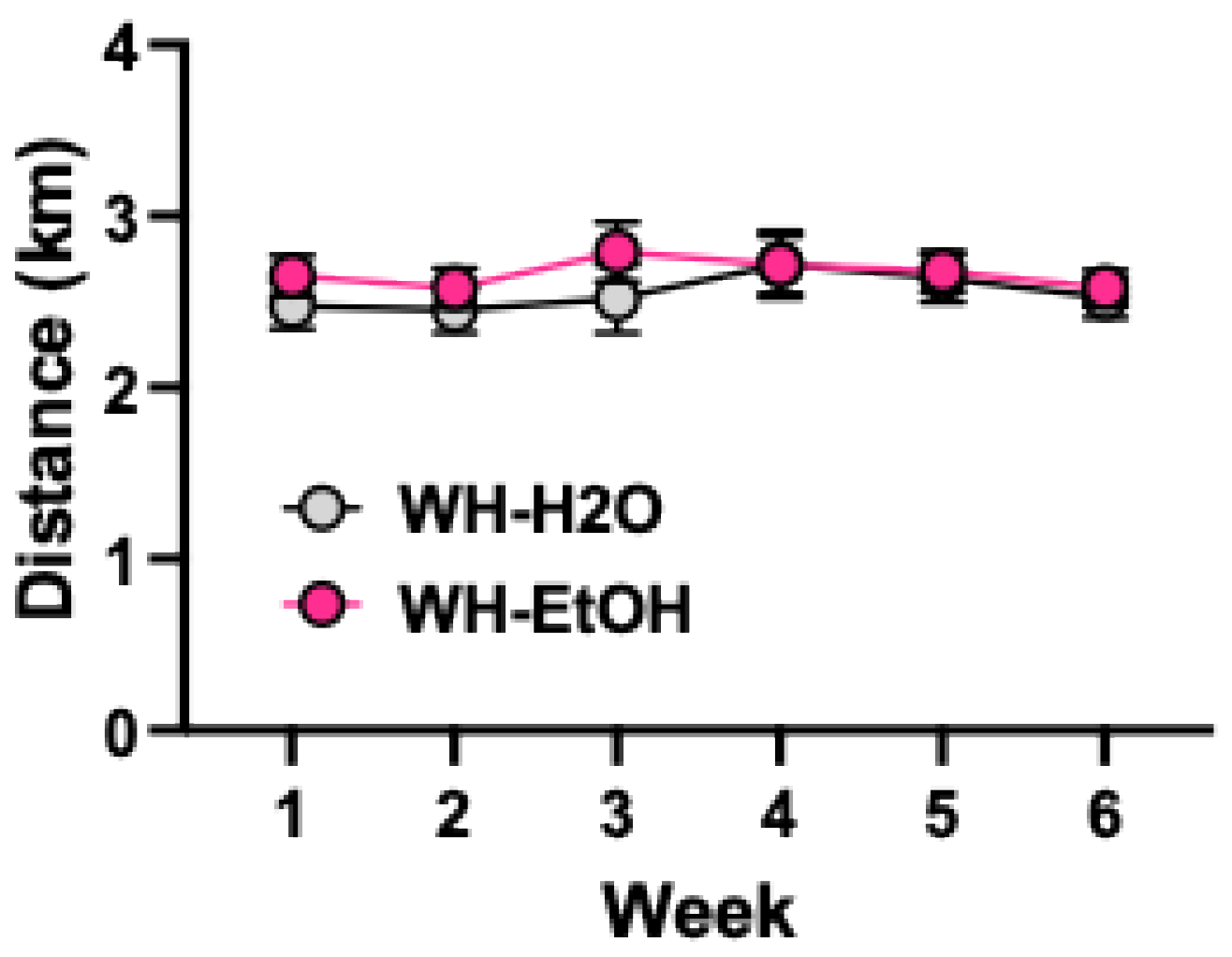

2.2. Effects of Alcohol Drinking on Wheel-Running and Bdnf mRNA Levels in mPFC

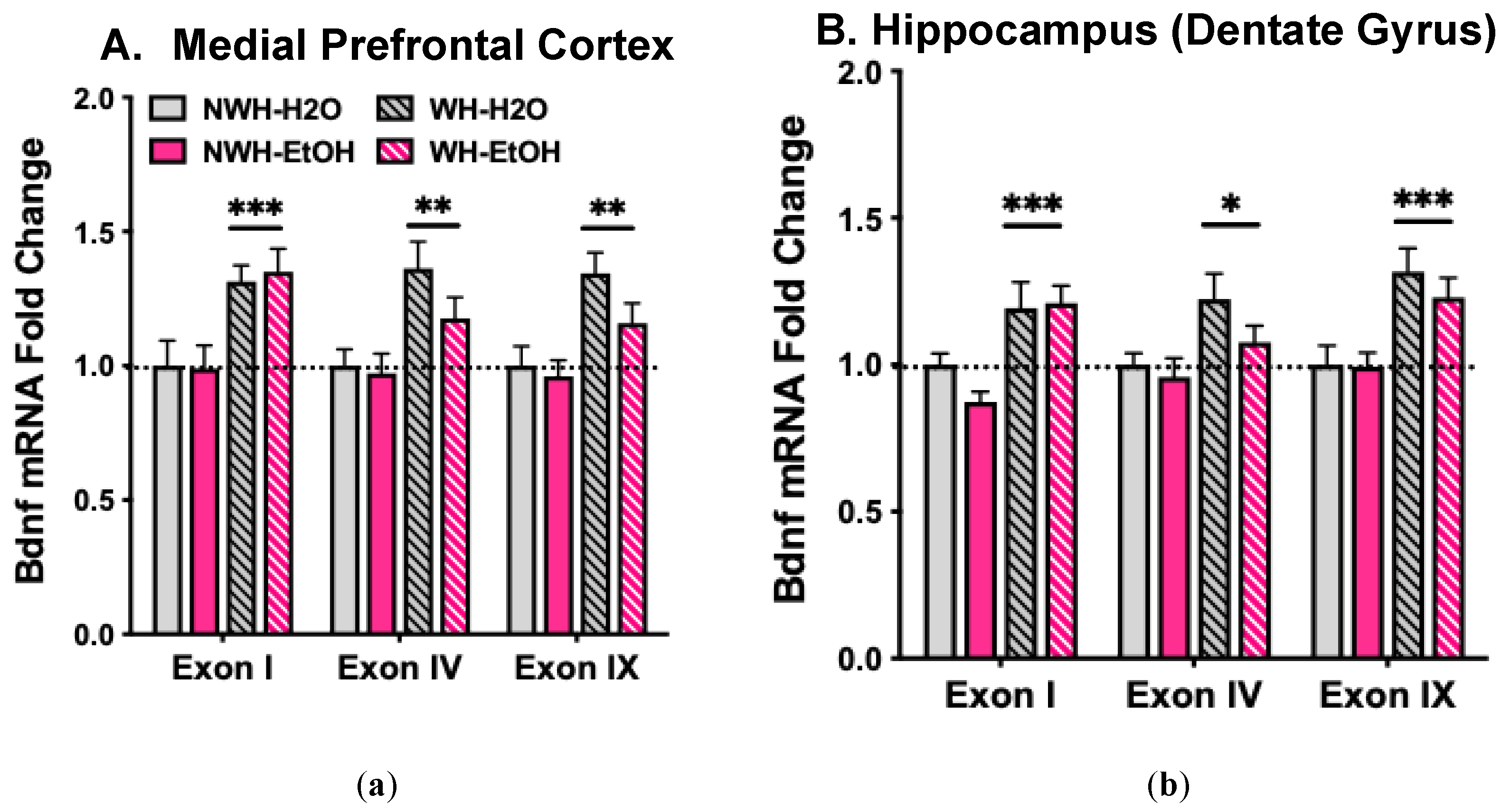

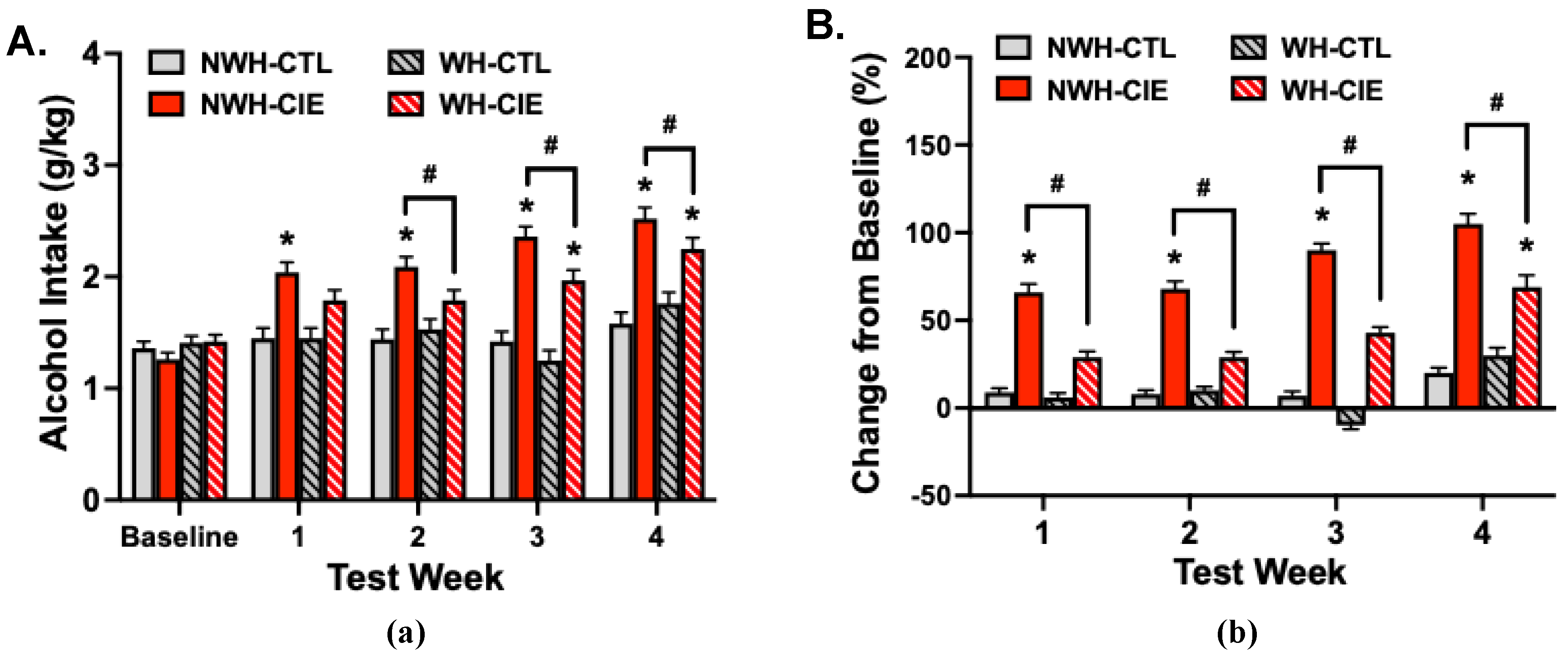

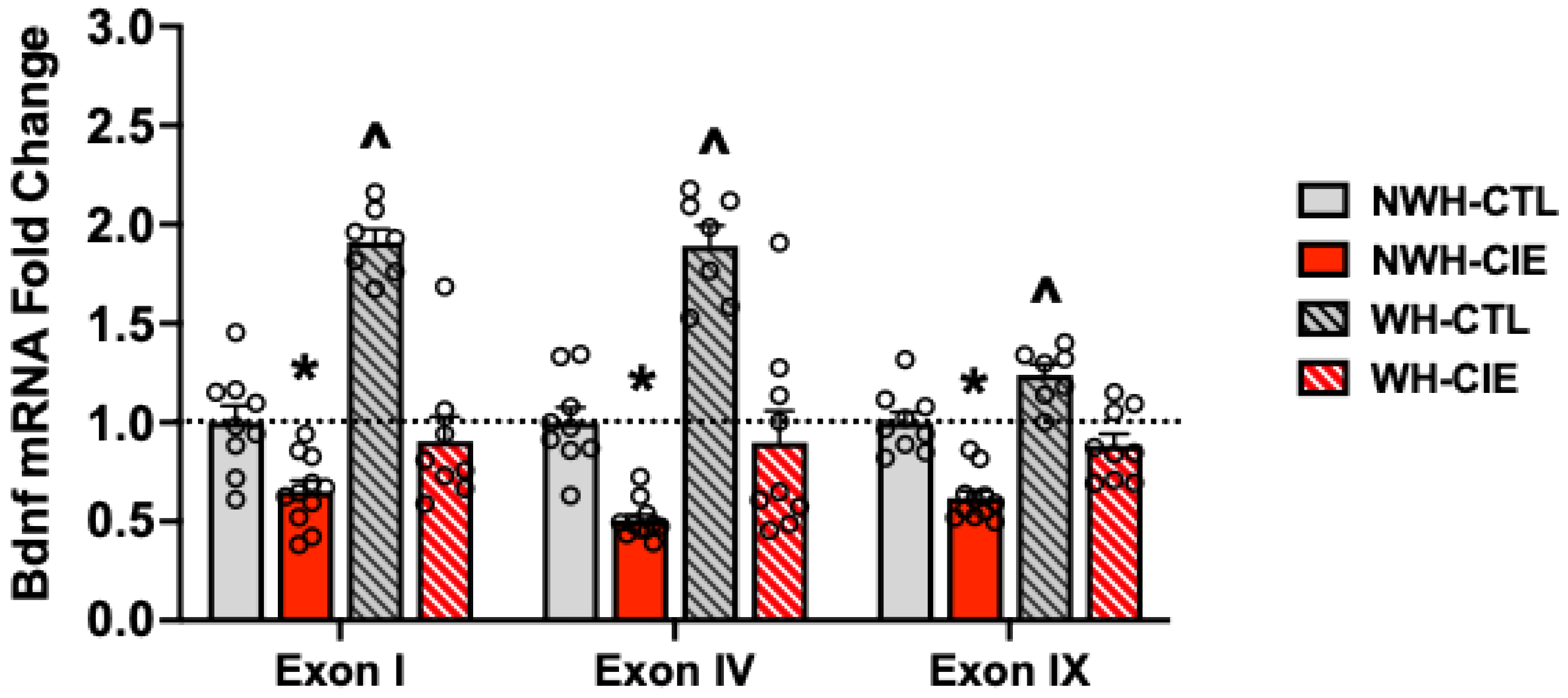

2.3. Wheel-Running Reverses Chronic Alcohol-Induced Deficits in mPFC Bdnf mRNA Expression and Attenuates Escalated Alcohol Drinking

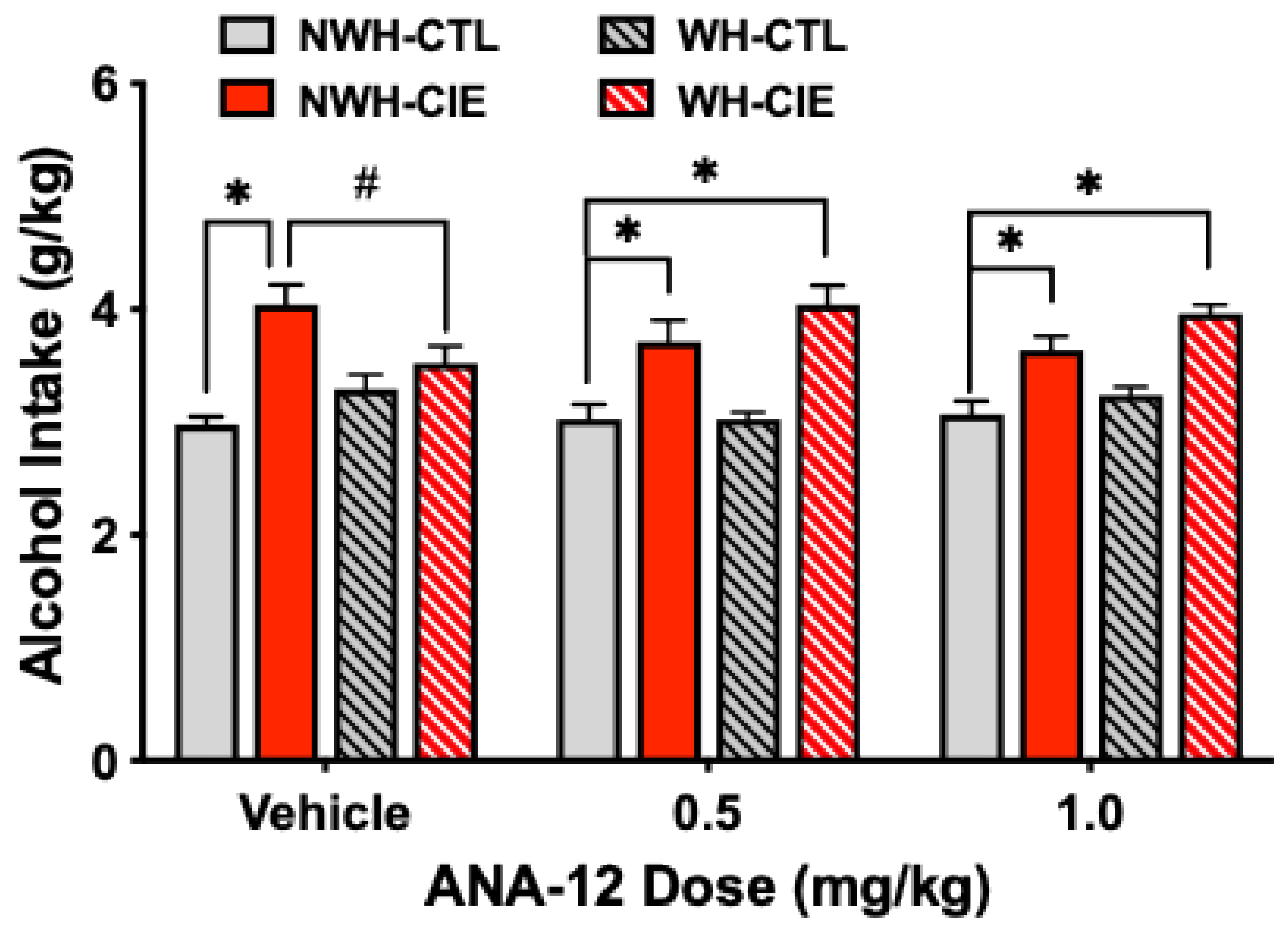

2.4. TrkB Receptor Antagonism Blocks the Ability of Exercise to Attenuate CIE-Induced Escalated Drinking

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

4.2. Exercise: Scheduled Wheel-Running

4.3. Home Cage Limited Access Alcohol Drinking

4.4. Chronic Intermittent Ethanol (CIE) Exposure

4.5. Brain Tissue Collection

4.7. ELISA Assay

4.8. ANA-12 Preparation

4.9. Data Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kerr, W.C. , et al., Longitudinal assessment of drinking changes during the pandemic: The 2021 COVID-19 follow-up study to the 2019 to 2020 National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2022. 46(6): p. 1050-1061. [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F., P. Powell, and A. White, Addiction as a Coping Response: Hyperkatifeia, Deaths of Despair, and COVID-19. Am J Psychiatry, 2020. 177(11): p. 1031-1037.

- White, A.M. , et al., Alcohol-Related Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA, 2022. 327(17): p. 1704-1706.

- Kranzler, H.R. and M. Soyka, Diagnosis and Pharmacotherapy of Alcohol Use Disorder: A Review. JAMA, 2018. 320(8): p. 815-824.

- Rehm, J. , et al., Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet, 2009. 373(9682): p. 2223-33.

- Sacks, J.J. , et al., 2010 National and State Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Am J Prev Med, 2015. 49(5): p. e73-e79.

- Koob, G.F. , Alcohol Use Disorder Treatment: Problems and Solutions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 2024. 64: p. 255-275.

- Litten, R.Z. , et al., Five Priority Areas for Improving Medications Development for Alcohol Use Disorder and Promoting Their Routine Use in Clinical Practice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2020. 44(1): p. 23-35.

- Ray, L.A., R. Green, and E. Grodin, Neurobiological Models of Alcohol Use Disorder in Humans. Am J Psychiatry, 2021. 178(6): p. 483-484.

- Witkiewitz, K., R. Z. Litten, and L. Leggio, Advances in the science and treatment of alcohol use disorder. Sci Adv, 2019. 5(9): p. eaax4043.

- Melendez, R.I. , et al., Brain region-specific gene expression changes after chronic intermittent ethanol exposure and early withdrawal in C57BL/6J mice. Addict Biol, 2012. 17(2): p. 351-64. [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, L.F. , Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2006. 361(1473): p. 1545-64.

- Ron, D. and A. Berger, Targeting the intracellular signaling "STOP" and "GO" pathways for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2018. 235(6): p. 1727-1743.

- Nubukpo, P. , et al., Determinants of Blood Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Blood Levels in Patients with Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2017. 41(7): p. 1280-1287.

- Heberlein, A. , et al., BDNF and GDNF serum levels in alcohol-dependent patients during withdrawal. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2010. 34(6): p. 1060-4.

- Xu, K. , et al., Nucleotide sequence variation within the human tyrosine kinase B neurotrophin receptor gene: association with antisocial alcohol dependence. Pharmacogenomics J, 2007. 7(6): p. 368-79.

- Wojnar, M. , et al., Association between Val66Met brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene polymorphism and post-treatment relapse in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2009. 33(4): p. 693-702.

- Matsushita, S. , et al., Association study of brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene polymorphism and alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2004. 28(11): p. 1609-12.

- Warnault, V. , et al., The BDNF Valine 68 to Methionine Polymorphism Increases Compulsive Alcohol Drinking in Mice That Is Reversed by Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase B Activation. Biol Psychiatry, 2016. 79(6): p. 463-73.

- Stragier, E. , et al., Ethanol-induced epigenetic regulations at the Bdnf gene in C57BL/6J mice. Mol Psychiatry, 2015. 20(3): p. 405-12.

- Briones, T.L. and J. Woods, Chronic binge-like alcohol consumption in adolescence causes depression-like symptoms possibly mediated by the effects of BDNF on neurogenesis. Neuroscience, 2013. 254: p. 324-34.

- Jeanblanc, J. , et al., Endogenous BDNF in the dorsolateral striatum gates alcohol drinking. J Neurosci, 2009. 29(43): p. 13494-502.

- Jeanblanc, J. , et al., BDNF-mediated regulation of ethanol consumption requires the activation of the MAP kinase pathway and protein synthesis. Eur J Neurosci, 2013. 37(4): p. 607-12.

- Pandey, S.C. , et al., Central and medial amygdaloid brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling plays a critical role in alcohol-drinking and anxiety-like behaviors. J Neurosci, 2006. 26(32): p. 8320-31.

- Darcq, E. , et al., The Neurotrophic Factor Receptor p75 in the Rat Dorsolateral Striatum Drives Excessive Alcohol Drinking. J Neurosci, 2016. 36(39): p. 10116-27.

- Tapocik, J.D. , et al., microRNA-206 in rat medial prefrontal cortex regulates BDNF expression and alcohol drinking. J Neurosci, 2014. 34(13): p. 4581-8.

- Solomon, M.G. , et al., Brain Regional and Temporal Changes in BDNF mRNA and microRNA-206 Expression in Mice Exposed to Repeated Cycles of Chronic Intermittent Ethanol and Forced Swim Stress. Neuroscience, 2019. 406: p. 617-625.

- Haun, H.L. , et al., Increasing Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) in medial prefrontal cortex selectively reduces excessive drinking in ethanol dependent mice. Neuropharmacology, 2018. 140: p. 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Palasz, E. , et al., BDNF as a Promising Therapeutic Agent in Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(3).

- Lynch, W.J. , et al., Exercise as a novel treatment for drug addiction: a neurobiological and stage-dependent hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2013. 37(8): p. 1622-44.

- Smith, M.A. and W.J. Lynch, Exercise as a potential treatment for drug abuse: evidence from preclinical studies. Front Psychiatry, 2011. 2: p. 82.

- Centanni, S.W. , et al., The impact of intermittent exercise on mouse ethanol drinking and abstinence-associated affective behavior and physiology. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2022. 46(1): p. 114-128.

- Darlington, T.M. , et al., Mesolimbic transcriptional response to hedonic substitution of voluntary exercise and voluntary ethanol consumption. Behav Brain Res, 2014. 259: p. 313-20.

- Darlington, T.M. , et al., Voluntary wheel running reduces voluntary consumption of ethanol in mice: identification of candidate genes through striatal gene expression profiling. Genes Brain Behav, 2016. 15(5): p. 474-90.

- Ehringer, M.A., N. R. Hoft, and M. Zunhammer, Reduced alcohol consumption in mice with access to a running wheel. Alcohol, 2009. 43(6): p. 443-52.

- Gallego, X. , et al., Voluntary exercise decreases ethanol preference and consumption in C57BL/6 adolescent mice: sex differences and hippocampal BDNF expression. Physiol Behav, 2015. 138: p. 28-36.

- Grigsby, K. , et al., Voluntary wheel-running reduces harmful drinking in a genetic risk model for drinking to intoxication. Alcohol, 2025. 128: p. 35-42.

- Ozburn, A.R., R. A. Harris, and Y.A. Blednov, Wheel running, voluntary ethanol consumption, and hedonic substitution. Alcohol, 2008. 42(5): p. 417-24.

- Werme, M. , et al., Running increases ethanol preference. Behav Brain Res, 2002. 133(2): p. 301-8.

- Booher, W.C. J. Reyes Martinez, and M.A. Ehringer, Behavioral and neuronal interactions between exercise and alcohol: Sex and genetic differences. Genes Brain Behav, 2020. 19(3): p. e12632. [CrossRef]

- Leasure, J.L. , et al., Exercise and Alcohol Consumption: What We Know, What We Need to Know, and Why it is Important. Front Psychiatry, 2015. 6: p. 156.

- Lynch, W.J. , et al., Exercise as a Sex-Specific Treatment for Substance Use Disorder. Curr Addict Rep, 2017. 4(4): p. 467-481.

- Manthou, E. , et al., Role of exercise in the treatment of alcohol use disorders. Biomed Rep, 2016. 4(5): p. 535-545.

- Terry-McElrath, Y.M. and P.M. O'Malley, Substance use and exercise participation among young adults: parallel trajectories in a national cohort-sequential study. Addiction, 2011. 106(10): p. 1855-65; discussion 1866-7.

- Brown, R.A. , et al., A preliminary, randomized trial of aerobic exercise for alcohol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat, 2014. 47(1): p. 1-9.

- Penedo, F.J. and J.R. Dahn, Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 2005. 18(2): p. 189-93.

- Greenwood, B.N. , et al., Exercise-induced stress resistance is independent of exercise controllability and the medial prefrontal cortex. Eur J Neurosci, 2013. 37(3): p. 469-78.

- Linke, S.E. , et al., The Go-VAR (Veterans Active Recovery): An Adjunctive, Exercise-Based Intervention for Veterans Recovering from Substance Use Disorders. J Psychoactive Drugs, 2019. 51(1): p. 68-77.

- Cotman, C.W., N. C. Berchtold, and L.A. Christie, Exercise builds brain health: key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends Neurosci, 2007. 30(9): p. 464-72.

- Phillips, C. , Physical Activity Modulates Common Neuroplasticity Substrates in Major Depressive and Bipolar Disorder. Neural Plast, 2017. 2017: p. 7014146.

- Franklin, K.B.J. and G. Paxinos, The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, Third Edition. 3rd ed. 2008, San Diego: Academic Press.

- Berchtold, N.C. , et al., Exercise primes a molecular memory for brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein induction in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience, 2005. 133(3): p. 853-61.

- Liu, P.Z. and R. Nusslock, Exercise-Mediated Neurogenesis in the Hippocampus via BDNF. Front Neurosci, 2018. 12: p. 52.

- Sleiman, S.F. , et al., Exercise promotes the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the action of the ketone body beta-hydroxybutyrate. Elife, 2016. 5. [CrossRef]

- Aid, T. , et al., Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J Neurosci Res, 2007. 85(3): p. 525-35.

- You, H. and B. Lu, Diverse Functions of Multiple Bdnf Transcripts Driven by Distinct Bdnf Promoters. Biomolecules, 2023. 13(4).

- Somkuwar, S.S. , et al., Wheel running reduces ethanol seeking by increasing neuronal activation and reducing oligodendroglial/neuroinflammatory factors in the medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Behav Immun, 2016. 58: p. 357-368.

- Islas-Preciado, D. , et al., Sex and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism matter for exercise-induced increase in neurogenesis and cognition in middle-aged mice. Horm Behav, 2023. 148: p. 105297.

- Camarini, R. , et al., Environmental enrichment and complementary clinical interventions as therapeutic approaches for alcohol use disorder in animal models and humans. Int Rev Neurobiol, 2024. 178: p. 323-354.

- Costa, G.A. , et al., Environmental Enrichment Increased Bdnf Transcripts in the Prefrontal Cortex: Implications for an Epigenetically Controlled Mechanism. Neuroscience, 2023. 526: p. 277-289.

- Piza-Palma, C. , et al., Oral self-administration of EtOH: sex-dependent modulation by running wheel access in C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2014. 38(9): p. 2387-95.

- Becker, H.C. and M.F. Lopez, Increased ethanol drinking after repeated chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal experience in C57BL/6 mice. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 2004. 28(12): p. 1829-1838.

- Becker, H.C. and M.F. Lopez, Animal Models of Excessive Alcohol Consumption in Rodents. Curr Top Behav Neurosci, 2024.

- Griffin, W.C. , 3rd, M.F. Lopez, and H.C. Becker, Intensity and duration of chronic ethanol exposure is critical for subsequent escalation of voluntary ethanol drinking in mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 2009. 33(11): p. 1893-1900.

- Griffin, W.C. , 3rd, et al., Repeated cycles of chronic intermittent ethanol exposure in mice increases voluntary ethanol drinking and ethanol concentrations in the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology, 2009. 201(4): p. 569-580.

- Livak, K.J. and T.D. Schmittgen, Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods, 2001. 25(4): p. 402-8. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).