1. Introduction

The standard derivation of Special Relativity takes the experimentally verified constancy of light speed—established through electromagnetic theory and optical experiments—and postulates the absence of any propagation medium [

1]. However, the mathematical structure of relativity can be derived from an alternative foundation: the physical nature of space as a propagation medium and matter as excitations of this medium.

This paper synthesizes two complete geometric demonstrations from previous work [

2] that derive relativistic kinematics from first principles. We first demonstrate how the Michelson-Morley experiment’s null result imposes a necessary geometric constraint on any measuring apparatus moving through the medium. We then derive from the wave nature of matter the physical mechanism—helical light trajectories—that naturally satisfies this constraint and leads to time dilation. Using the original diagrams and step-by-step geometric arguments, we show that relativistic effects arise as physical necessities rather than mathematical postulates.

Context and Broader Framework. This work constitutes a fundamental piece of a broader theoretical paradigm developed in a series of publications [

3,

4,

5]. This paradigm reinterprets spacetime as a dynamic, vibratory medium whose excitations give rise to particles, forces, and the laws of physics themselves. Within this framework, we have previously shown that the properties of this medium naturally lead to modified gravitational dynamics at galactic scales and provide explanations for particle physics phenomena.

The present article returns to the foundation of this entire edifice: the kinematics of objects moving within this medium. By deriving relativistic effects from the wave nature of matter, we provide the microphysical mechanism that underpins the deformation of spacetime relationships. This derivation is not only consistent with the broader paradigm but serves as its necessary cornerstone.

Relation to Established Research. Our approach shares the general insight of

analogue gravity [

6,

7]—that physical media can generate relativistic behavior—but with a crucial distinction: where analogue gravity constructs formal analogies, our paradigm posits that spacetime geometry is intrinsically the geometry of a fundamental medium. We derive special relativity directly from the wave mechanics of confined excitations, providing not an analogy but a causal microphysical mechanism.

Experimental Testability. Beyond providing physical mechanisms for relativistic effects, our approach offers a crucial experimental signature: precise measurements of time dilation could distinguish between different deformation patterns, potentially revealing transverse contraction () that would challenge standard relativity’s assumption of purely longitudinal contraction. This transforms the Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction from an ad hoc postulate into an empirically resolvable question.

Operational Equivalence and Philosophical Distinction. It is crucial to emphasize that our derivation maintains full operational equivalence with special relativity for all practical purposes. Since we can only measure relative velocities between material objects, not absolute motion through a hypothetical medium, both frameworks yield identical experimental predictions. The distinction is ontological rather than operational: where Einstein’s theory describes how measurements depend on relative motion, our framework provides a physical mechanism explaining why they so depend. This work should therefore be understood not as challenging the practical utility of special relativity, but as offering a physical foundation for its mathematical structure.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Medium-Based Paradigm

We assume space constitutes a physical medium supporting local constant wave propagation at speed c. Matter consists of confined wave structures within this medium. The key insight is understanding how standing waves, which appear stationary in a particle’s rest frame, manifest as moving structures in the medium frame.

A standing wave in a moving particle results from the superposition of constituent waves propagating in opposite directions relative to the particle. When viewed from the medium frame, the constant-magnitude velocity vectors c of these waves are tilted, decomposing into components: one for maintaining the standing wave structure and another for the particle’s translation at velocity v through the medium.

From the particle’s perspective, it appears at rest relative to the medium because the internal wave interference creates stationary patterns. However, from the medium’s perspective, these constituent waves drift with velocity v in the direction of motion while maintaining their fundamental propagation speed c.

This dual perspective resolves the apparent paradox: what appears as a pure standing wave in the particle’s frame manifests as a helical light trajectory in the medium frame. The helical path emerges because each point of the wave structure must simultaneously execute internal oscillations (maintaining the standing wave pattern) while translating through the medium at velocity v.

This conception fundamentally affects how matter behaves when in motion relative to the medium. The geometry of these helical trajectories, and the interference conditions of the constituent waves, necessarily change with velocity, leading to the relativistic effects derived in the following sections.

Internal Adaptation Mechanism

Crucially, this helical configuration emerges naturally from the standing wave structure itself. Within the moving particle, each constituent wave experiences the other as Doppler-shifted, with propagation directions modified by their relative motion. These reciprocal Doppler shifts force a mutual reorientation of wave vectors, tilting them forward and increasing the helical pitch with velocity. This self-consistent adjustment is the microscopic mechanism ensuring that the internal clock of the particle (the standing wave frequency) automatically synchronizes with its deformed spatial geometry, leading to the relativistic kinematics described in this paper.

1

Physical Meaning of in the Wave Paradigm

Within our framework, Einstein’s equation acquires a profound physical interpretation: the mass-energy of a particle represents the total deformation energy—both near-field and far-field—that the particle’s wave structure imposes upon the spatial medium.

For a moving particle, the total energy decomposes as:

This explains both the velocity-dependent mass increase and the nature of kinetic energy: it is the increase in total deformation energy as the wave structure becomes more distorted. The increasing difficulty of acceleration at high velocities reflects the growing energy investment needed to further deform the wave pattern against the medium’s restorative forces.

At , the energy diverges because complete conversion to pure translation requires infinite deformation energy—the standing wave structure must completely "unwind" into radiation. Thus, expresses the continuum from rest (minimal deformation) to light-speed motion (complete dissolution of the wave structure).

Connection to Observable Effects

This internal adaptation mechanism provides a fundamental explanation for well-known relativistic visual phenomena. The forward tilting of the internal wave vectors, required to maintain standing wave stability, directly corresponds to the

relativistic aberration observed when moving at high velocities [

8,

9]. This aberration, which causes the apparent compression of the visual field into a forward-directed tunnel, is thus not merely an optical illusion but a direct consequence of how wave-based matter must reconfigure its internal geometry to persist in motion relative to the medium. Similarly, the Doppler boosting effect (the amplification of forward-directed radiation) finds a natural explanation in the increased energy density of the forward-tilted wave fronts. Our medium-based approach therefore unifies the kinematic formulas of relativity with their dramatic visual manifestations under a single physical principle.

2.2. The Measuring Process

All measurements of space and time are ultimately made using material instruments - rulers composed of atoms, clocks based on atomic processes. Crucially, these instruments are themselves made of fundamental particles, and according to our paradigm, these particles are wave structures confined within the medium.

Therefore, what we measure as "space" and "time" intervals are not measurements of abstract coordinates but readings from physical devices whose very operation depends on their motion state relative to the medium. The rulers that measure length and the clocks that measure time are themselves physical objects whose internal wave structure deforms when in motion through the medium.

This creates a fundamental self-consistency: the speed of light is fundamentally constant in the medium frame because it is determined by the medium’s properties. However, this constant speed appears also constant relative to a moving observer because their measuring devices (rulers and clocks) are physically deformed by their motion through the medium in precisely the compensating manner described by Equation (

1), making the medium undetectable through local experiments [

10].

3. Part I: Complete Geometric Derivation from Michelson-Morley

The Michelson-Morley experiment’s null result provides the crucial constraint on medium-based theories. Appendix A presents the complete geometric derivation using the original diagram and analysis.

3.1. The General Deformation Condition

As derived in Appendix A from the Michelson-Morley null result [

11], the experimental data requires that moving apparatuses deform according to:

where

and

are the deformations for dimensions parallel and perpendicular to motion.

The Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction (, ) represents only one particular solution satisfying this constraint. However, the Michelson-Morley experiment alone cannot distinguish between this specific case and other possible deformation patterns that satisfy the same ratio.

Crucial Distinction: In Einstein’s special relativity, length contraction is not a postulate but a derived consequence of the relativity of simultaneity applied to moving reference frames. The Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction, by contrast, was proposed as an ad hoc postulate to explain the Michelson-Morley result within a stationary ether framework. Our approach differs from both: we derive the general deformation constraint from experimental necessity, while leaving the specific deformation factors to be determined by the physical principles of wave-based matter.

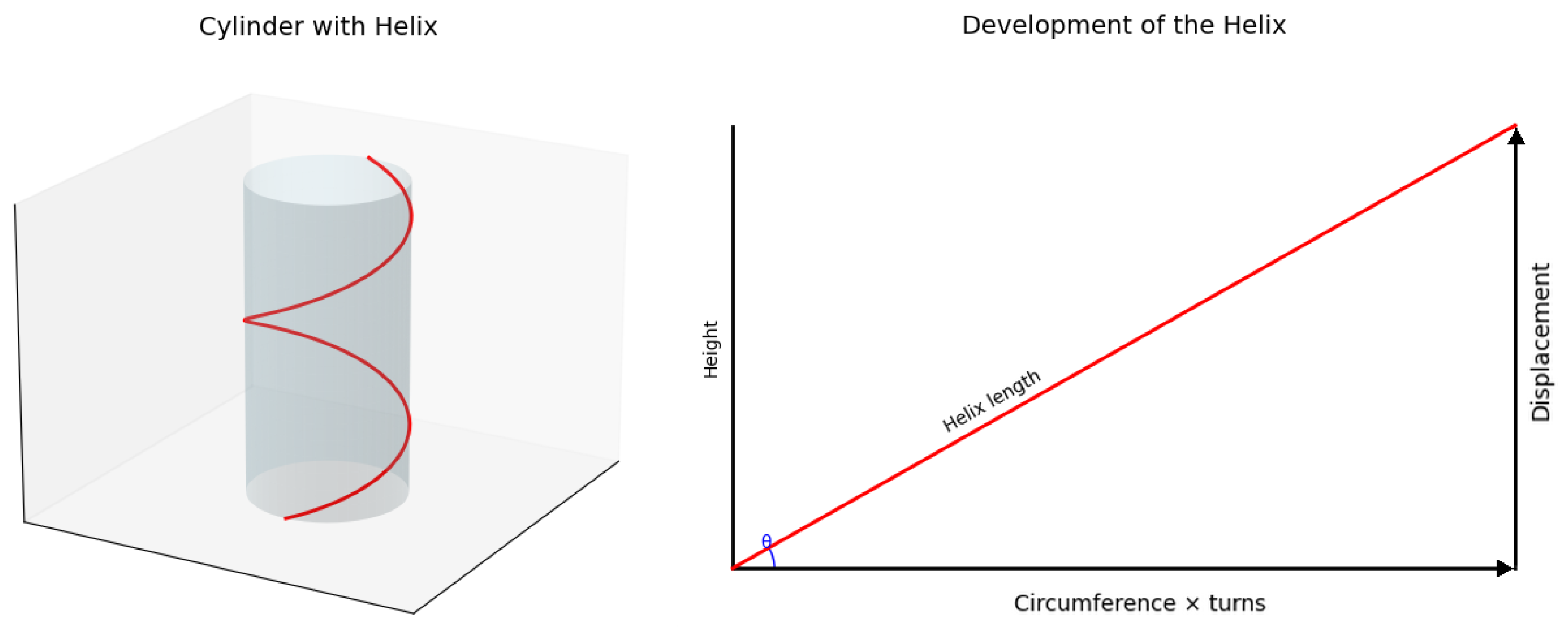

4. Part II: Physical Derivation of Time Dilation from Wave Geometry

If matter consists of confined light-like trajectories, then time dilation emerges naturally from the geometry of these trajectories when in motion. Appendix B provides the complete derivation using the helical path analysis.

4.1. Time Dilation from Helical Light Trajectories

As shown in Appendix B, when a particle moves through the medium, its internal light-like trajectory becomes helical. The development of this helix reveals a right triangle from which time dilation follows geometrically. It is important to note that the standard derivation presented here implicitly assumes no transverse contraction (

), corresponding to the Lorentz-FitzGerald hypothesis. The resulting formula:

thus represents the specific case where deformation occurs only longitudinally. As developed in the generalized framework of Appendix B, different deformation patterns would yield modified time dilation expressions, providing an experimental signature to distinguish between possible medium-matter interaction models.

4.2. Length Contraction as a Corollary

The combination of time dilation effects and the Michelson-Morley deformation constraint necessarily induces length variations in measuring apparatuses constructed from wave-based matter, ensuring consistent measurement outcomes across different states of motion.

4.3. The Physical Mechanism of Length Contraction

Length contraction emerges naturally from the wave nature of matter when we consider how confined light trajectories deform under motion relative to the medium.

Consider a fundamental particle as a standing wave structure where light-like oscillations execute closed loops. When at rest in the medium, these loops are perfectly symmetrical - the wave completes cycles without net translation. The particle’s spatial extension is determined by the interference conditions of these standing waves.

When the particle moves with velocity v relative to the medium, a portion of each oscillation cycle must be devoted to pure translation. The confined light trajectory becomes helical rather than purely oscillatory. This has two crucial consequences:

Time Dilation: The internal oscillation frequency decreases because part of the light’s path length is used for translation rather than completing loops (as derived in Appendix B).

Wave Deformation: The standing wave pattern that defines the particle’s spatial extension becomes anisotropic. Along the direction of motion, the wave interference conditions change because the effective wavelength is modified by the motion component.

Now consider a measuring rod composed of such wave-based particles bound together. The equilibrium distance between particles is determined by the interplay of binding forces (themselves wave-mediated) and the particles’ internal wave structures. When all constituent particles have their internal oscillations slowed and their wave patterns deformed in the direction of motion, the rod’s natural length must adjust accordingly.

The deformation constraint from Michelson-Morley (Equation

1) tells us the specific ratio required:

. Thus, length deformation is not an arbitrary postulate but a physical necessity: matter—and therefore measuring instruments—physically deforms when in motion through the supporting medium, while light propagates independently through this same medium at constant speed

c.

Another way to visualize contraction is to understand its relationship with kinetic energy. The energy of a wave increases as its wavelength decreases. Thus, as kinetic energy (relative to the medium) increases, the wavelength of the particle’s constituent waves must decrease. Longitudinal contraction results directly from translation, while transverse contraction arises from the three-dimensional interconnections between the constituent waves.

5. Synthesis: Emergence of a Generalized Relativistic Kinematics

The preceding derivations establish a complete medium-based framework that leads to a generalized relativistic kinematics. Crucially, our approach reveals that the Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction postulate is not only unnecessary but physically incorrect within our paradigm.

The Michelson-Morley experiment provides the fundamental constraint (Equation

1):

This relationship is an experimental necessity, but it does not specify individual values for

and

.

5.1. Physical Mechanism of Relativistic Effects

In our paradigm, proper time dilation can be understood from the helical trajectory of internal waves as matter moves through the spatial medium. However, the physical origin of length contraction is more subtle and requires consideration of the IN/OUT wave mechanism described in our foundational work [

12].

Fundamental particles are not localized within restricted volumes but consist of constituent waves that radiate OUT waves progressively reflected back, forming standing (or pseudo-standing) wave patterns. When a particle moves through the medium, this motion induces a Doppler effect: standing waves in the forward direction have shorter wavelengths than those in the rear direction.

The internal waves are energetically coupled to the standing waves they generate, with each serving as the energy source for the other in a reciprocal relationship. As velocity increases, the shortening of internal waves necessarily implies a reduction in particle size. At the atomic level, this reasoning applies to the entire system of nucleus and electrons, where we should consider the atom as a whole rather than individual particles.

The kinetic energy gained by motion through the medium manifests as increased deformation energy of the wave structure. Since wave energy increases as wavelength decreases, higher kinetic energy requires shorter wavelengths for the particle’s constituent waves, directly leading to spatial contraction.

5.2. Generalized Deformation Framework

The time dilation formula (Equation

2),

, remains valid as it derives purely from the helical path geometry. However, the coordinate transformations that emerge differ from Lorentz transformations, describing instead the relationship between the medium frame and frames using generalized deformed measuring apparatus.

This leads to a more fundamental kinematics where the principle of relativity originates not from Lorentz covariance, but from the consistent deformation of all wave-based measuring devices according to the medium-matter interaction laws.

6. Discussion: Integration into a Unified Paradigm

Our derivation represents a fundamental departure from both Einstein’s relativity and Lorentz’s ether theory, offering a third path grounded in wave-mechanical principles.

6.1. Comparison with Existing Paradigms

6.2. Fundamental Difference from Einstein’s Derivation

While Einstein’s approach derives length contraction from the relativity of simultaneity and the constancy of light speed, our medium-based derivation yields the general constraint from Michelson-Morley. The specific case of pure longitudinal contraction () emerges in Einstein’s theory as a consequence of spatial isotropy in inertial frames, whereas in Lorentz’s theory it was an independent postulate.

This represents a crucial conceptual shift: rather than imposing postulates or deriving from symmetry principles, we obtain the deformation constraint from experimental necessity and then determine the specific deformations ( and ) from the physical principles of energy distribution in confined wave systems. In our model, the specific deformation pattern is not postulated but emerges from the wave-mechanical nature of matter.

This distinction makes our theory empirically testable: any measured transverse deformation would support our model over standard relativity. Moreover, precise measurements of time dilation could independently determine the deformation factors, providing a second experimental avenue for verification. This represents a crucial experimental signature that could distinguish between the frameworks, as standard relativity strictly requires by definition and predicts a unique, fixed relationship between velocity and time dilation.

6.3. Connection to General Relativity and Broader Implications

The natural question arising from our medium-based approach concerns its compatibility with General Relativity (GR). We propose that the curvature of spacetime in GR can be understood as an emergent description of the graded elasticity and density variations of the fundamental medium. This viewpoint is supported by several independent research programs:

Analogue Gravity: Demonstrates that Einstein-like equations emerge in various physical media [

6,

7]

Thermodynamic Approaches: Derive GR from thermodynamic principles applied to spacetime horizons [

13]

Emergent Gravity Frameworks: Suggest that spacetime geometry may not be fundamental but emergent [

14]

Our derivation of special relativity provides the

local, kinematical foundation for such an emergent GR framework. The broader implications of this paradigm for unresolved issues in cosmology and particle physics are explored in our related publications [

4,

5], where we show how the medium properties naturally lead to modified gravitational dynamics and explanations for particle generations.

6.4. Testable Predictions and Falsifiability

The key distinction from standard relativity lies in the physical mechanism: rather than being mathematical postulates, relativistic effects emerge from the necessary deformation of confined wave structures. This makes our theory empirically testable through several specific predictions:

Transverse Contraction Signature: Any measured transverse contraction () in high-precision length measurements of moving objects would definitively support our model over standard relativity. We predict that ultra-precise interferometric measurements might reveal a small but non-zero transverse deformation scaling with .

Time Dilation as Deformation Probe: Precision measurements of time dilation in fast-moving systems (atomic clocks on spacecraft, particle accelerators) could determine the actual deformation factors. A deviation from the standard formula would indicate , providing an independent test of the deformation pattern.

Medium Effects in Analog Systems: Our approach predicts that analog systems (Bose-Einstein condensates, optical media) should exhibit similar deformation patterns when effective "matter waves" move through flowing media, providing experimental avenues for verification in controlled laboratory settings.

Anisotropy Signatures: In scenarios where the medium might exhibit slight anisotropy (due to large-scale cosmic flows or gravitational gradients), our framework predicts measurable directional dependence in relativistic effects, unlike standard relativity.

The falsifiability of our theory represents a significant advantage over conventional interpretations: clear experimental signatures could distinguish it from standard relativity, while null results would constrain possible medium-based models without invalidating the overall framework. Crucially, our approach offers multiple independent experimental pathways for verification, enhancing its testability and scientific robustness.

6.5. Experimental Pathway to Absolute Motion Detection

A remarkable implication of our theoretical framework is that it offers a potential pathway to measure absolute motion relative to the medium through precision dimensional metrology. Unlike historical ether-drift experiments that measured light travel times, our approach focuses on direct measurement of dimensional deformation ratios.

If experimental techniques were developed to directly measure the ratio

from different inertial frames with known relative velocity

, one could solve the equation:

where the left-hand side is experimentally measured and

is the known relative velocity between frames. Measurement of this ratio would uniquely determine

, the absolute velocity relative to the medium.

This approach fundamentally differs from Michelson-Morley type experiments in several key aspects:

It measures dimensional ratios rather than light interference patterns

It requires knowledge of relative velocity between frames, which is experimentally accessible

It exploits the precise mathematical constraint derived from Michelson-Morley rather than attempting to detect first-order ether drift effects

Modern nanometrology techniques could potentially achieve the required precision for such measurements

While technically demanding, this pathway remains consistent with the operational equivalence principle: absolute velocity relative to the medium would be determined through relative measurements between inertial frames, maintaining the fundamental insight that only relative motions are directly measurable.

6.6. From Postulates to Experimental Predictions

The most significant advancement of our medium-based approach is its capacity to transform special relativity’s foundational postulates into experimentally testable predictions.

Specifically, the Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction ceases to be a postulate and becomes an empirical question: do moving objects exhibit pure longitudinal contraction () or a more general deformation pattern? High-precision time dilation experiments—using atomic clocks on spacecraft, particle accelerators, or satellite systems—could resolve this question definitively. A measured deviation from the standard time dilation formula would indicate , while confirmation would establish the Lorentz postulate as an empirical fact rather than an assumption.

This represents a fundamental shift in the epistemological status of special relativity, moving from a theory based on postulates to one derived from physical principles with experimentally verifiable microfoundations.

6.7. Practical Utility and Foundational Interpretation

A crucial aspect of our framework is its relationship to the established formalism of special relativity. While we derive relativistic kinematics from different foundational assumptions, we emphasize several key points:

Operational Equivalence: For all practical experimental purposes, our framework is indistinguishable from special relativity. Since we can only measure relative velocities between material objects, not absolute motion through the medium, both theories make identical predictions for measurable quantities.

Practical Primacy of Relativity: Special relativity remains the most efficient and powerful framework for calculating physical phenomena in moving systems. Our approach does not seek to replace its mathematical formalism but to provide a physical interpretation of its foundations.

Foundational Contribution: Where our framework offers novel insight is in explaining why the principles of relativity hold. Einstein’s derivation effectively rests on one core ontological commitment: the rejection of any propagation medium. We challenge this foundational assumption by demonstrating that the same relativistic kinematics arises naturally from a medium-based framework where matter consists of confined wave structures.

Experimental Distinction: The key potential distinction lies in scenarios where absolute motion effects might become detectable through precision measurements of deformation patterns, particularly regarding transverse contraction (). Such measurements could, in principle, distinguish between the frameworks.

This dual perspective—maintaining the practical utility of relativity while offering a deeper physical interpretation—parallels the relationship between thermodynamics and statistical mechanics. Just as statistical mechanics provides microscopic explanations for thermodynamic principles without invalidating their practical utility, our framework aims to provide microscopic explanations for relativistic principles while preserving their operational validity.

7. Kinetic Energy Considerations

We have deduced that for the Michelson-Morley experiment to yield null results within our paradigm, longitudinal arm contraction must occur, while transverse arm dilation is forbidden (the transverse arm must either contract or remain undeformed).

It is reasonable to hypothesize that kinetic energy corresponds to the sum and intensity of spatial deformations experienced by the waves constituting a particle. The greater the deformation, the higher the kinetic energy would be.

A thought experiment can help address this question. Within the strict framework of Special Relativity, certain questions remain unanswerable. For example:

Consider a positron and an electron separated by a distance D. If we accelerate the positron to high velocity toward the electron, it gains kinetic energy. During the annihilation of and , the resulting radiation includes both the rest mass energies and the kinetic energy accumulated by . One might conclude that the positron contributed more to the final radiation than the electron.

However, if we had accelerated the electron instead of the positron, we would then attribute the greater contribution to the electron. Consequently, the assumption that all measurement reference frames are equivalent leads to a paradox: depending on the observer’s frame, kinetic energy is assigned differently to each particle. Yet, the energy content of a particle cannot logically depend on the observer.

In contrast, if we attribute kinetic energy to particle deformation relative to the medium, the paradox disappears: we can precisely determine each particle’s contribution to the final radiation.

8. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that relativistic kinematics can be rigorously derived from a medium-based foundation where matter consists of confined wave structures. The complete geometric proofs establish:

Experimental Foundation: Michelson-Morley’s null result necessitates a deformation constraint for objects moving through the medium.

Physical Mechanism: Time dilation emerges geometrically from helical light trajectories in moving wave-based particles.

Generalized Deformation Framework: Contrary to Lorentz’s specific postulate, our approach allows for a broader class of deformation patterns where both longitudinal and transverse dimensions may deform according to energy redistribution principles in confined wave systems, wherein kinetic energy emerges naturally as the energetic cost of maintaining these deformed wave configurations.

Relativity as Consistent Measurement: The apparent validity of special relativity in experiments results from consistent deformation of all wave-based measuring apparatus.

Transforming Postulates into Experimental Predictions.

The most significant advancement of our framework is its capacity to transform the question of length deformation from a theoretical postulate into an experimentally testable prediction. While Michelson-Morley experiment establishes the deformation ratio , precise measurements could determine whether real matter exhibits the specific deformation pattern ().

If experimental measurements confirm , this would validate the specific deformation pattern derived by Einstein’s relativity, while our framework provides the physical mechanism. Conversely, if measurements reveal , our generalized framework naturally accommodates this while maintaining consistency with Michelson-Morley.

For all experimental purposes involving relative motion between material objects, special relativity remains the indispensable computational framework.

8.1. The Fundamental Postulate Revisited

Einstein’s derivation of special relativity begins with a profound ontological postulate: that light requires no medium for its propagation, and that the laws of electrodynamics are valid in all inertial frames without reference to any underlying substance. This postulate of medium independence represents a radical departure from classical physics and establishes the constancy of light speed as a fundamental principle rather than a property of a material medium.

Our derivation challenges this foundational assumption by demonstrating that the complete mathematical structure of relativistic kinematics can be equally derived from the opposite postulate: that space constitutes a physical medium whose properties determine the constant speed c, and that matter consists of confined excitations of this medium.

The significance of this result is profound: it shows that the experimental evidence typically cited in support of special relativity—particularly the Michelson-Morley null result and the constancy of light speed—does not logically compel Einstein’s postulate of medium independence. The same empirical facts are equally consistent with a medium-based ontology, provided one accounts for the necessary deformation of material structures moving through this medium.

This transforms the status of Einstein’s first postulate from an empirical necessity to an ontological choice. Both frameworks—medium-independent relativity and our medium-based approach—reproduce the same kinematic predictions at the level of measurement, but they offer radically different answers to the question: what is the physical nature of space?

Appendix A. Complete Geometric Derivation of Michelson-Morley Constraint

This appendix presents the complete derivation of the deformation constraint using the original geometric analysis from Furne Gouveia [

2].

Appendix A.1. Experimental Setup and Light Path Analysis

Consider the interferometer moving with velocity

v relative to the medium. Let

be the proper length of each arm when at rest in the medium (

). When moving, the arms deform to lengths:

where

and

are absolute deformations that depend on the velocity

v relative to the medium. These factors describe how the physical length of the arms changes due to motion through the medium. The goal of our derivation is to find the relationship between

and

imposed by the Michelson-Morley null result.

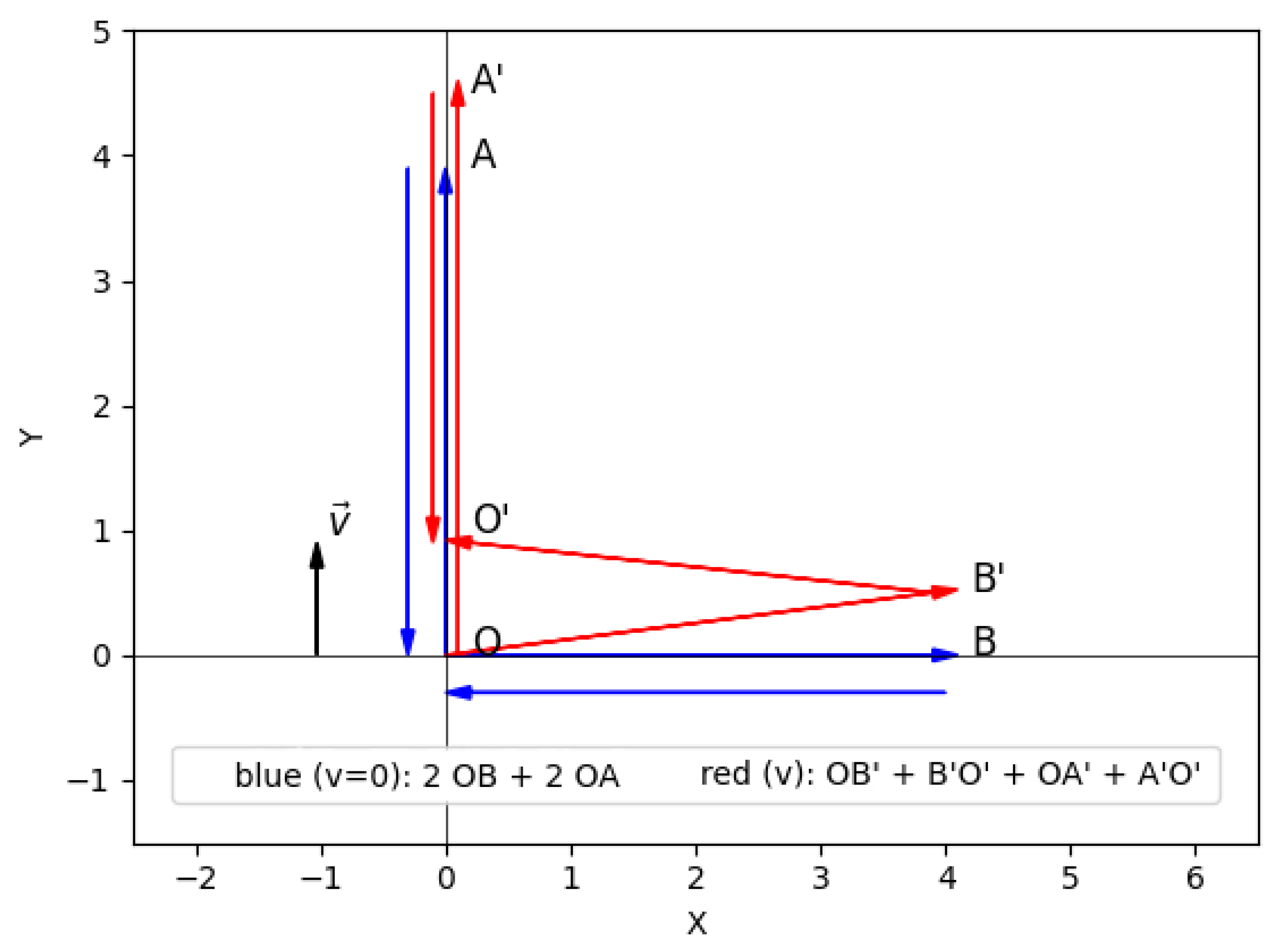

Figure A1.

Light paths in the Michelson interferometer: blue arrows show paths when stationary in the medium, red arrows show paths when moving with velocity v relative to the medium.

Figure A1.

Light paths in the Michelson interferometer: blue arrows show paths when stationary in the medium, red arrows show paths when moving with velocity v relative to the medium.

Appendix A.2. Transverse Arm Analysis Using Figure A1

Distance traveled by light in the medium:

Travel time:

Let us consider the travel durations between the points:

Appendix A.3. Longitudinal Arm Analysis Using Figure A1

For the longitudinal arm (parallel to motion), the light path in the medium frame is:

Forward trip (from O to A’):

Return trip (from A’ to O’):

Appendix A.4. Null Result Condition

The experimental null result requires equal round-trip times:

This completes the derivation of Equation (

1).

Table A1.

Complete analysis of light paths in the Michelson-Morley experiment (medium frame).

Table A1.

Complete analysis of light paths in the Michelson-Morley experiment (medium frame).

| Parameter |

Longitudinal Arm |

Transverse Arm |

| Arm length in medium frame |

|

|

| Round-trip time |

|

|

| Null result condition |

|

| Lorentz-FitzGerald special case |

|

Equation (

A1) indicates that

because

and can represent either dilation or contraction depending on their sign. Several scenarios must be considered.

Imaginary numerical examples satisfying this inequality:

The first case corresponds to a logical possibility because a moving particle contains more (kinetic) energy and more energetic waves have shorter wavelengths.

The second case corresponds to the Lorentz postulate.

The last two cases do not have correspondence in our paradigm because there is no reason for transverse dilation.

Appendix B. Generalized Derivation of Time Dilation from Helical Paths with Deformation Factors

Appendix B.1. Particle as Confined Light Trajectory with Deformation

Consider a fundamental particle as a confined light-like trajectory. When at rest, the trajectory forms closed loops of proper radius . When moving with velocity v relative to the medium, the particle deforms according to the factors and .

The helical trajectory now has the following:

Appendix B.2. Generalized Helical Path Analysis

Developing the deformed helix gives a right triangle with:

Hypotenuse: total light path

Vertical leg: internal loop path

Horizontal leg: translation path

Applying Pythagoras’ theorem:

The function

accounts for how the deformation affects the internal path length. For

and

, we recover the standard result:

The proper time of a moving particle slows down relative to a particle at rest with respect to the medium.

Figure A2.

Helical light trajectory with deformation factors and its development.

Figure A2.

Helical light trajectory with deformation factors and its development.

Appendix B.3. Experimental Testability

This generalized formulation reveals that precise measurements of time dilation could determine the actual deformation factors. The standard relativistic formula corresponds to the specific case , but our framework allows for experimental verification of whether transverse contraction occurs. Any deviation from the predicted time dilation would indicate , providing a crucial test distinguishing our medium-based approach from standard relativity.

References

- Einstein, A. Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper. Annalen der Physik 1905, 17, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G. A Generalized Contraction Framework for the Michelson-Morley Null Result in a Medium-Based Theory. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G. The Vibrational Fabric of Spacetime: A Model for the Emergence of Mass, Inertia, and Quantum Non-Locality. Preprints 2025a. [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G. The Role of Energy Density Diffusion in Galactic Dynamics and Cosmic Expansion: A Unified Theory for MOND and Dark Energy. Preprints 2025b. [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G. The Multiverse as the Source of Anisotropy: Explaining Three Fermion Generations and Early Galaxies. Preprints 2025c. [CrossRef]

- Barcelo, C.; Liberati, S.; Visser, M. Analogue gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity, 2005; 8, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Volovik, G. E. The Universe in a helium droplet; Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf, V. F. The Visual Appearance of Rapidly Moving Objects. Physics Today 1960, 13, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, U. First-person visualizations of the special and general theory of relativity. European Journal of Physics 2002, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentz, H. A. Electromagnetic phenomena in a system moving with any velocity smaller than that of light. Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences 1904, 6, 809. [Google Scholar]

- Michelson, A. A.; Morley, E. W. On the Relative Motion of the Earth and the Luminiferous Ether. American Journal of Science 1887, 34, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G. The IN/OUT Wave Mechanism: A Non-Local Foundation for Quantum Behavior and the Double-Slit Experiment. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Physical Review Letters 1995, 75, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilczek, F. Getting its from bits. Nature 2004, 427, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

This can be visualized by considering two swimmers in a moving river, trying to maintain a fixed distance from each other. Each must adjust their swimming angle relative to the water’s flow to compensate for the current and maintain their relative position. Similarly, the constituent waves adjust their "swimming" direction in the medium to preserve the interference pattern that defines the particle. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).