3.1. Characterization Results of Support

The structure, morphology and texture of the support and catalysts were assessed through low-angle XRD, SEM, TEM and physisorption measurements, respectively.

Table 1 presents their physico-chemical properties.

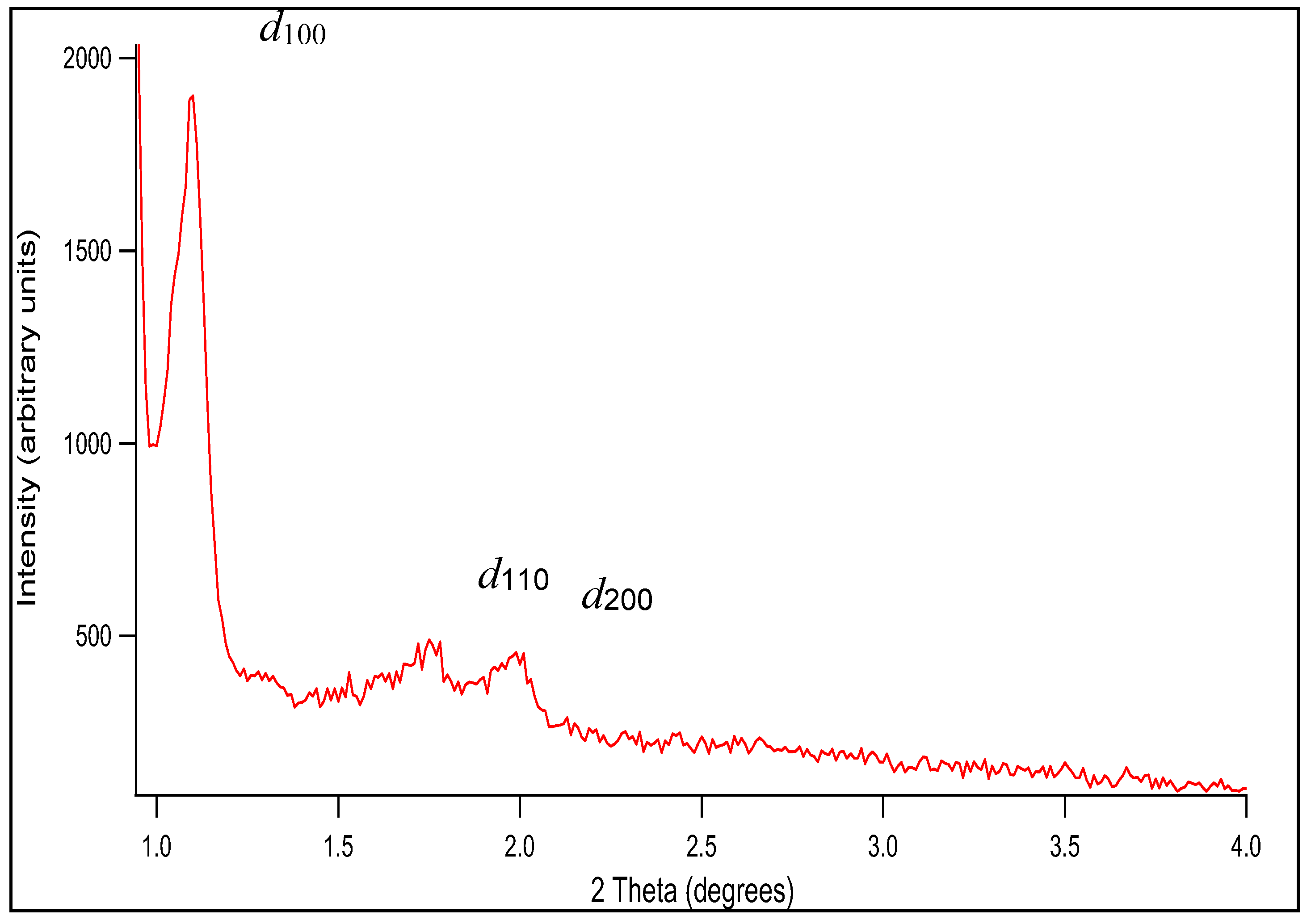

Figure 1 shows the low angle powder XRD patterns of SBA-15. Three XRD peaks are observed at 2

θ ~1 – 4º, which can be indexed as (100), (110), and (200) reflections of a well-ordered 2D hexagonal (

p6mm) mesostructure possessing long-range order, with a quite large unit cell [

24,

25], namely

a = 9.7 nm. (The unit cell parameter

a is calculated from

a = 2d100/√3, where the

d-spacing values are calculated by

nλ = 2

d100 sin

θ.) The obtained hexagonal mesostructured was expected as the volume fraction of the block copolymer, i.e.,

ΦP123 (%), in the mesostructured composite was in the range of 38-52% for H

2O-P123 and 40-55% for SiO

2-P123. Lamelar, hexagonal or cubic mesophases can be obtained by controlling the

ΦP123 fraction [

27]

. However, it should be noted that SBA-15 cannot be regarded as an ideal hexagonal lattice of pores imbedded in a uniform matrix, as the structure of the silica walls is more complex. This can be easily assessed by calculating the

dS/V number, where

d is pore diameter,

S is specific surface area and

V is pore volume. For a material possessing an ideal hexagonal geometry this number should be equal to 4 [

28,

29]. By using the structural parameters displayed in

Table 1, the value of 4.3 is obtained for the prepared SBA-5 sample, which is rather close to the theoretical value.

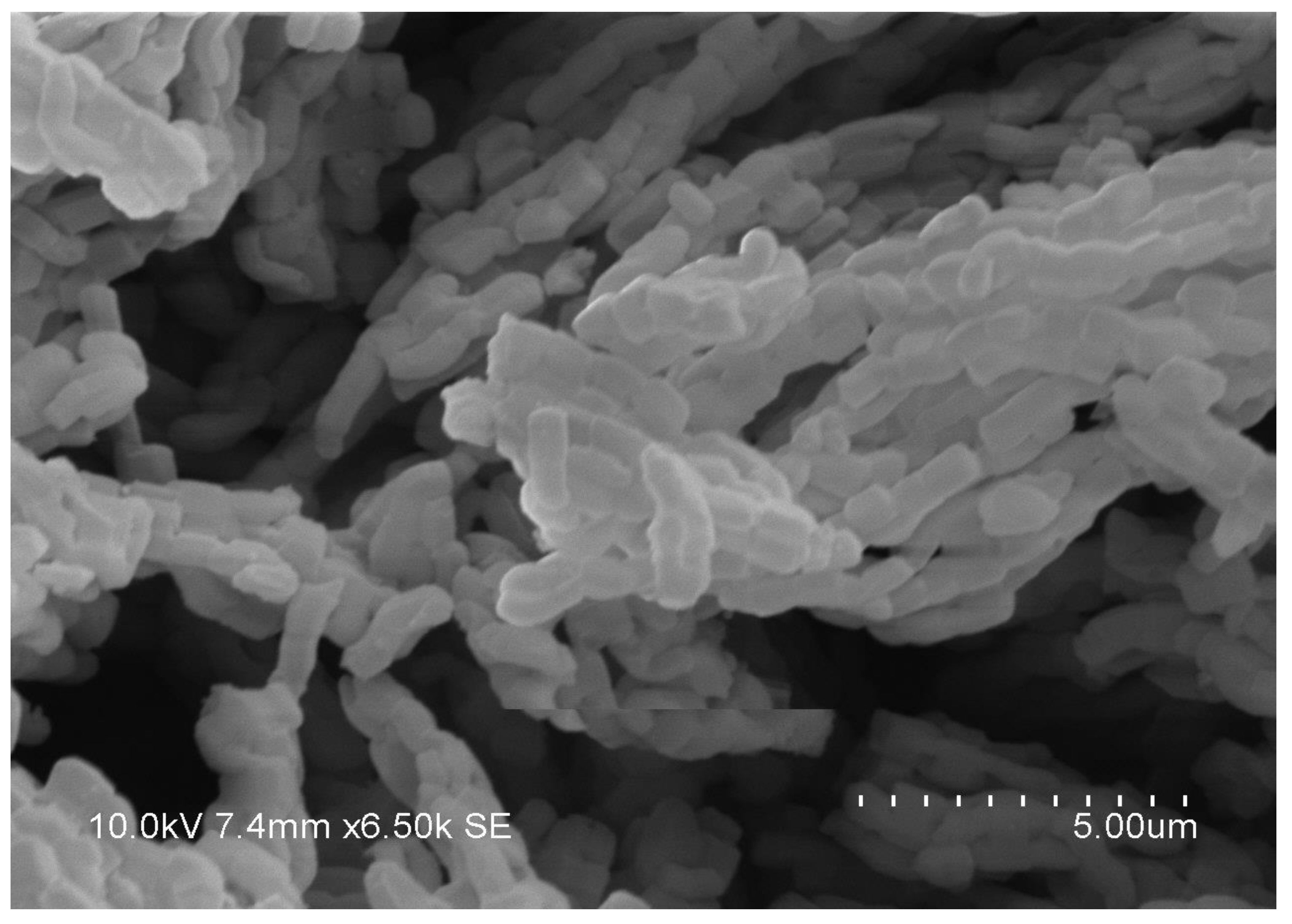

SEM image reveals that the calcined SBA-15 sample consists of many fiber (rope)-like domains (

Figure 2). Each fiber seems to be formed by end-to-end aggregations of apparently wheat grain shaped SBA-15 particles (primary particles) of 0.5-1.0 μm in length and 0.5 μm in width. As such the surface energy of the hydrophilic ends due to hydroxyl groups is reduced and their growth is encouraged in the 001 plane.

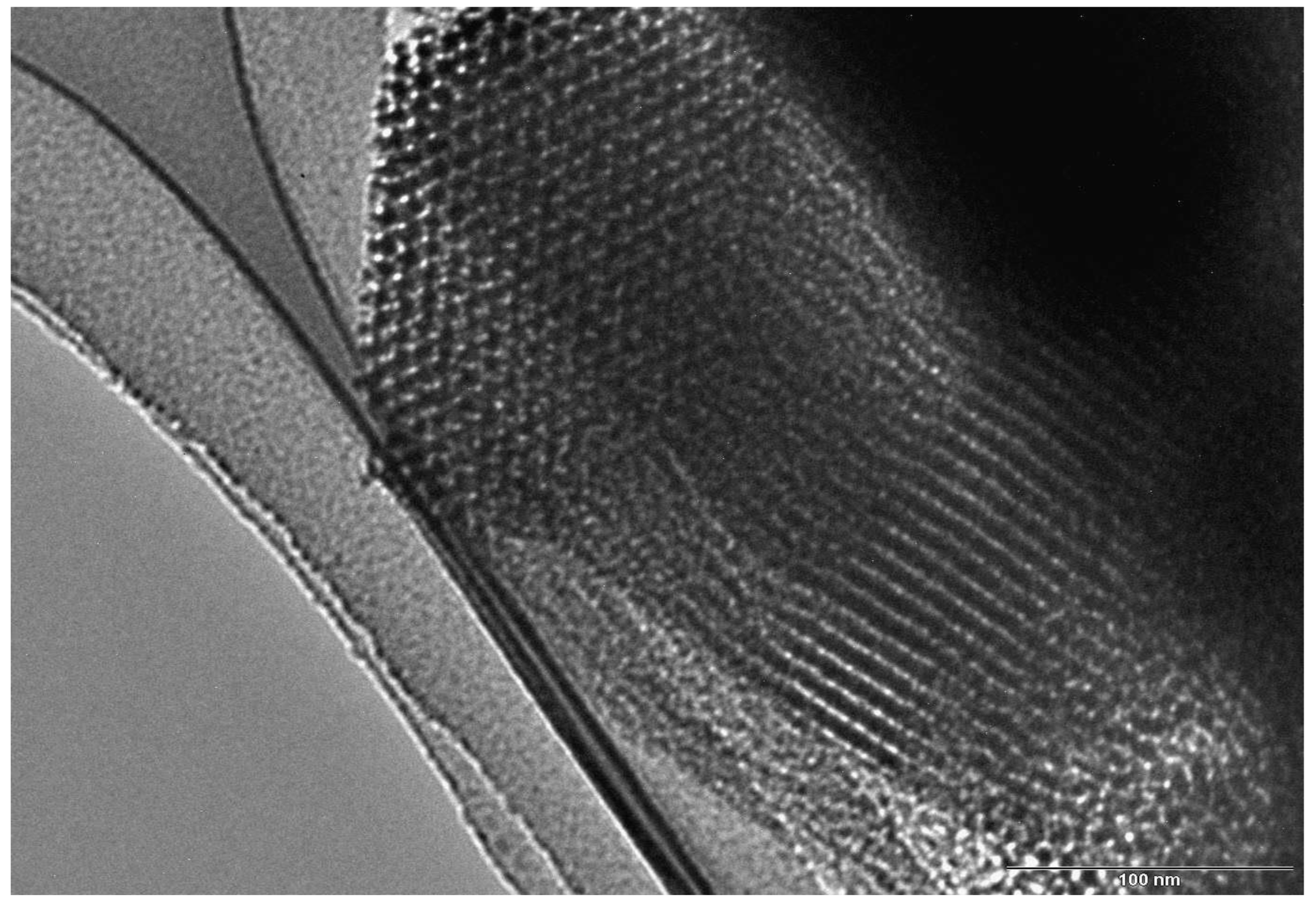

TEM measurements confirm the highly well-ordered hexagonal network of rather straight cylindrical mesopores. As seen in

Figure 3, SBA-15 shows a 2D hexagonal packed array of pores with long 1D channels (p6mm plane group) [

30]. The channels are interconnected by small micropores. Thus, SBA-15 exhibits mainly mesoporous structure and possesses a small amount of micropores. The mesopore diameter estimated from TEM micrographs is between 6.3 and 6.5 nm; the distance between mesopores (interplanar distance),

d100, is estimated to be ~ 8.5 nm, in good agreement with that determined from the XRD data, using Bragg’s law.

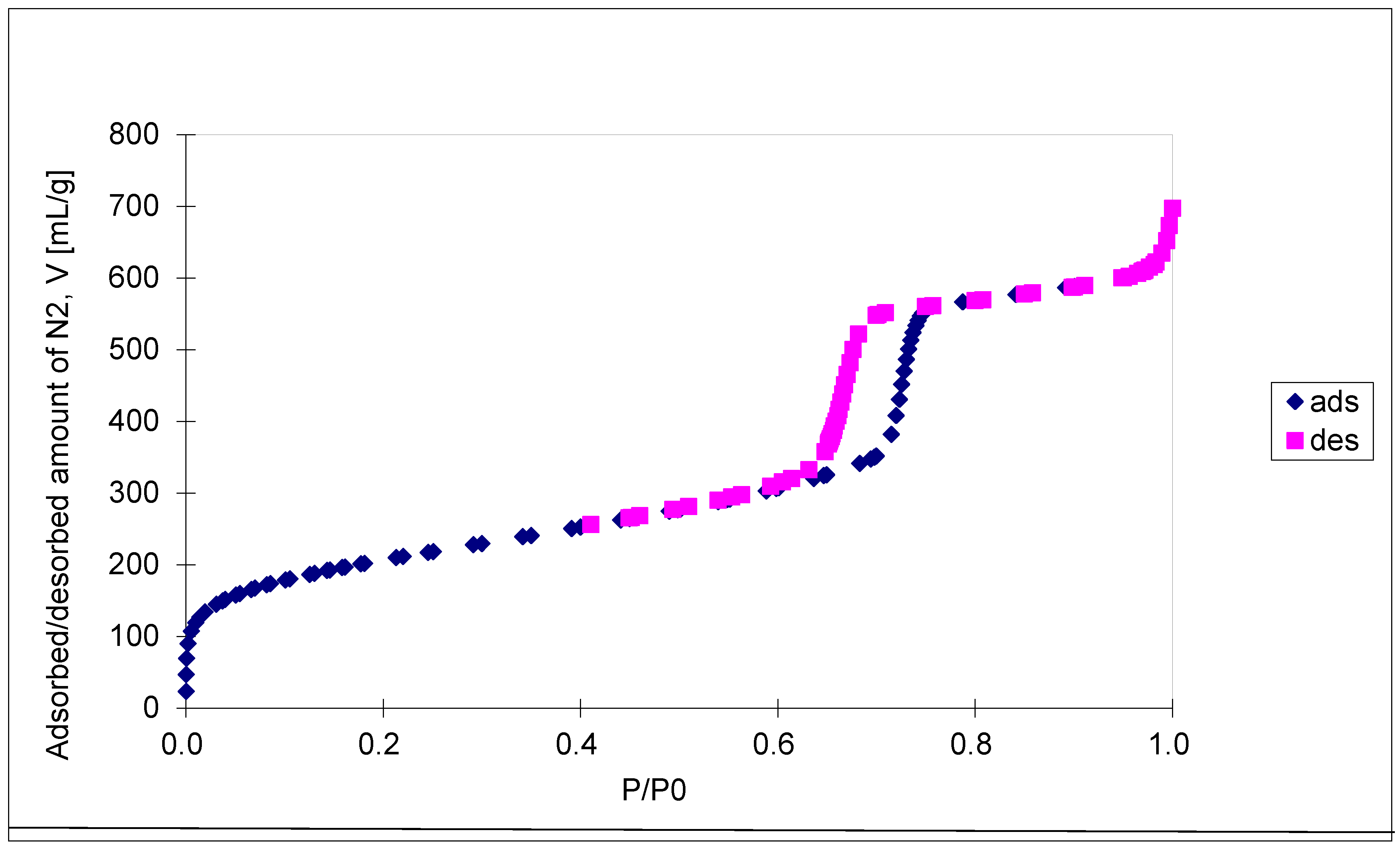

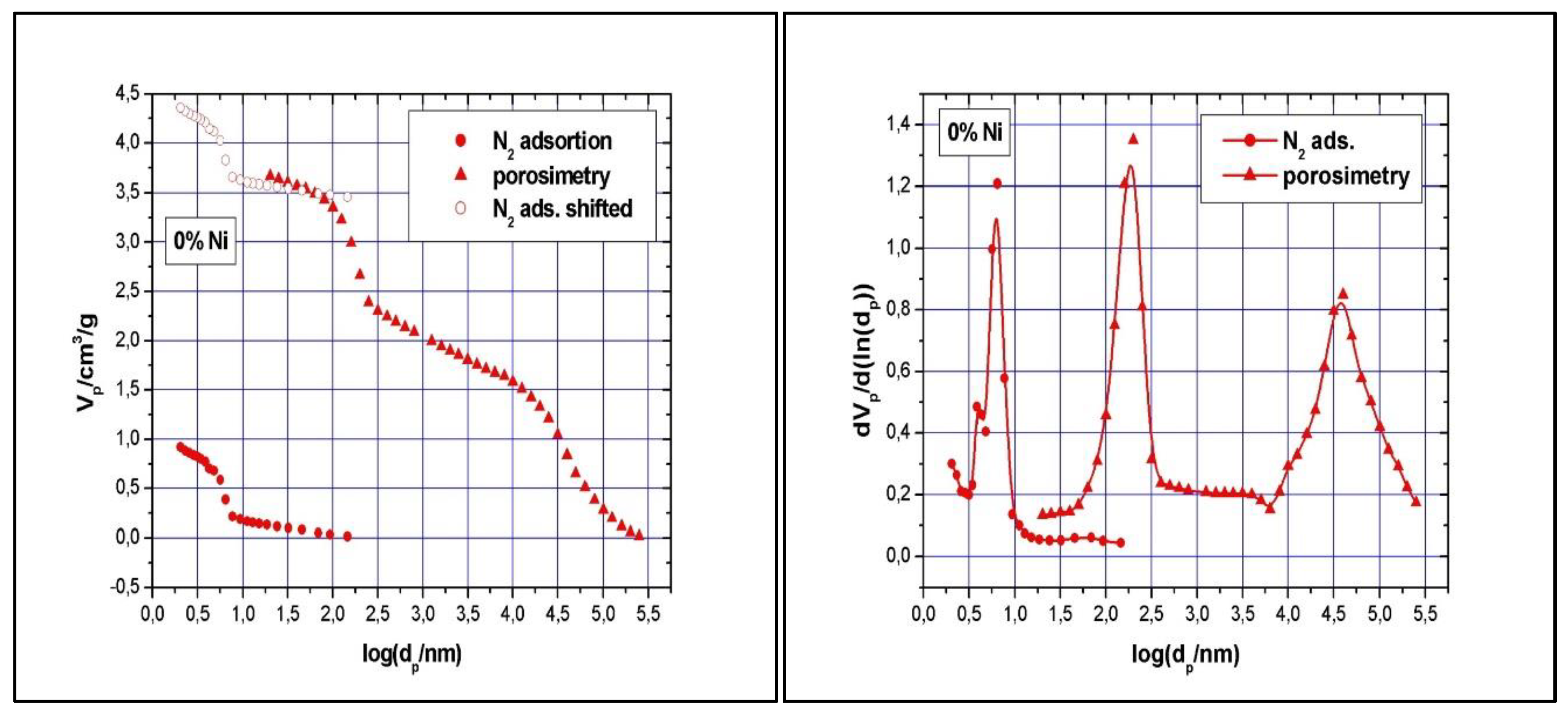

The N

2 isotherms are of type IV with an H1 hysteresis loop, according to IUPAC classification, and present a steep capillary condensation step at medium relative pressure (P/P

0 ~ 0.6), characteristic of high-quality open, nearly cylindrical large-pore SBA-15 mesoporous silica (see

Figure 4). Three distinct regions can be discerned in the isotherm for SBA-15 sample: (1) monolayer–multilayer adsorption of nitrogen on the pore walls at low pressures, (2) a sudden steep increase of the adsorbed nitrogen at intermediate pressures due to the capillary condensation, and (3) multilayer adsorption on the external surface of the particles. The broad hysteresis loop of SBA-15 sample is caused by the presence of long mesopores connected by smaller micropores, thus hampering the filling and emptying of the accessible volume. The sharpness of the capillary condensation steps indicates uniformity of pore channels and their narrow pore size distribution. Indeed, the pore size distribution, defined as the pore volume increments per unit logarithm of pore diameter versus the logarithm of the corresponding pore diameters, was narrow although the SBA-15 sample shows, besides the main pores of 6.5 nm diameter, pore volume of 0.94 cm

3/g, and BET surface area of 720 m

2/g, the presence of smaller pores of about 3.9 nm diameters as well. The fact that there is some N

2 adsorption at very low relative pressure evidences the presence of micropores. Along with the N

2 adsorption measurements, mercury intrusion porosimetry measurements were performed, which evidenced the presence of intra- and inter-particles macropores, with relative narrow pore size distribution as well (in the range of 50 – 300 nm and 10 – 175 μm, respectively).

Figure 5A shows the cumulative specific adsorbed and intrusion volumes plotted versus the logarithm of the pore diameter while

Figure 5B presents the pore size distribution.

Using the XRD and BET measurements’ results, the thickness of the pore walls was calculated as 3.2 nm (thickness = a – pore diameter). With these rather thick pore walls, the prepared SBA-15 sample is expected to have good mechanical and thermal resistance during the impregnation and calcination of the catalyst samples and, as such, the well-ordered structure to be preserved.

3.2. Characterization Results of Catalysts

The well-ordered hexagonal structure was maintained by multi-step impregnation of nickel acetate into SBA-15 (results not shown). All samples displayed the three reflections: (100), (110) and (200), characteristic of the hexagonal array of mesochannels, although slightly shifted towards higher 2θ values as compared with the bare sample. The higher the loading, the higher the shift, and the higher the unit cell contraction. A possible interpretation of this result could be that some of the nickel was impregnated on the surface and not inside the silica framework. If this is the case, the volume of the pores for the catalyst’s samples should decrease as the loading is increased.

TEM/EDX revealed that the NiO wt% was 4.98 for the sample prepared through two impregnation cycles, while for the one with five impregnation cycles, the NiO wt% was 10.60. Therefore, the two samples were labelled as 5 % Ni and 11% Ni, respectively.

From the wide-angle XRD results over the two samples (not shown here), no peaks corresponding to crystalline nickel oxide can be identified, indicating either the samples were amorphous or, if crystalline, the nickel oxide clusters were very small (less than 3 nm) and beyond the detection limit.

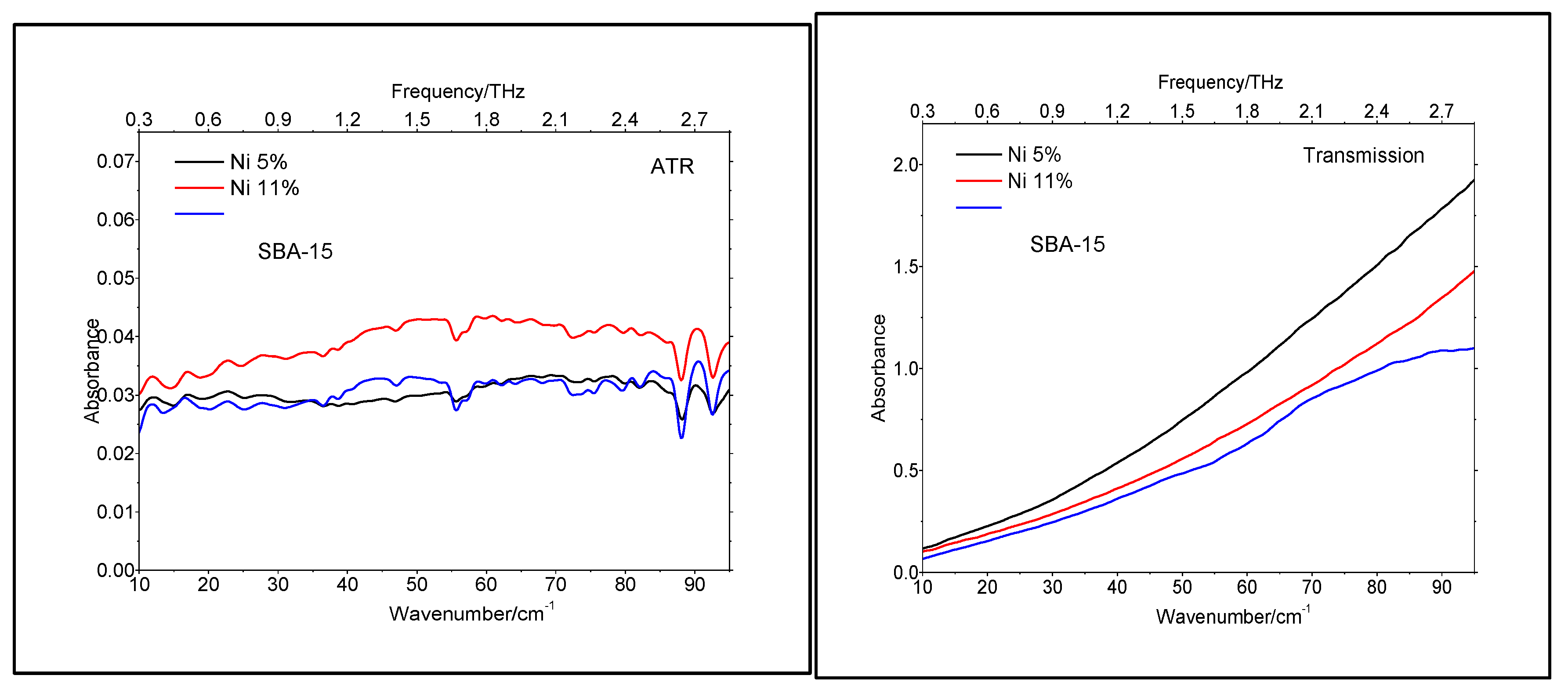

The lack of crystallinity was also supported by the TeraHertz spectroscopy, performed both in ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) and Transmission modes, as shown in

Figure 6. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first time that TeraHertz spectroscopy has been applied to catalysts characterization.

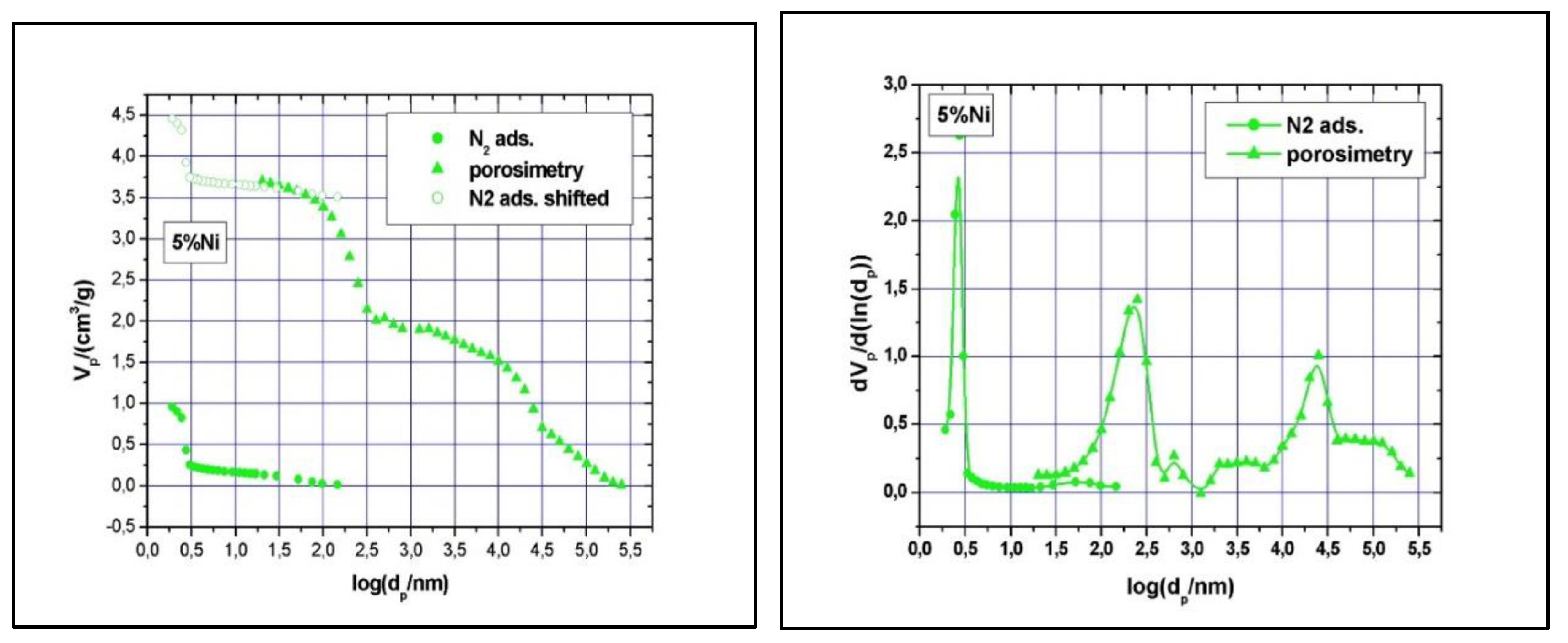

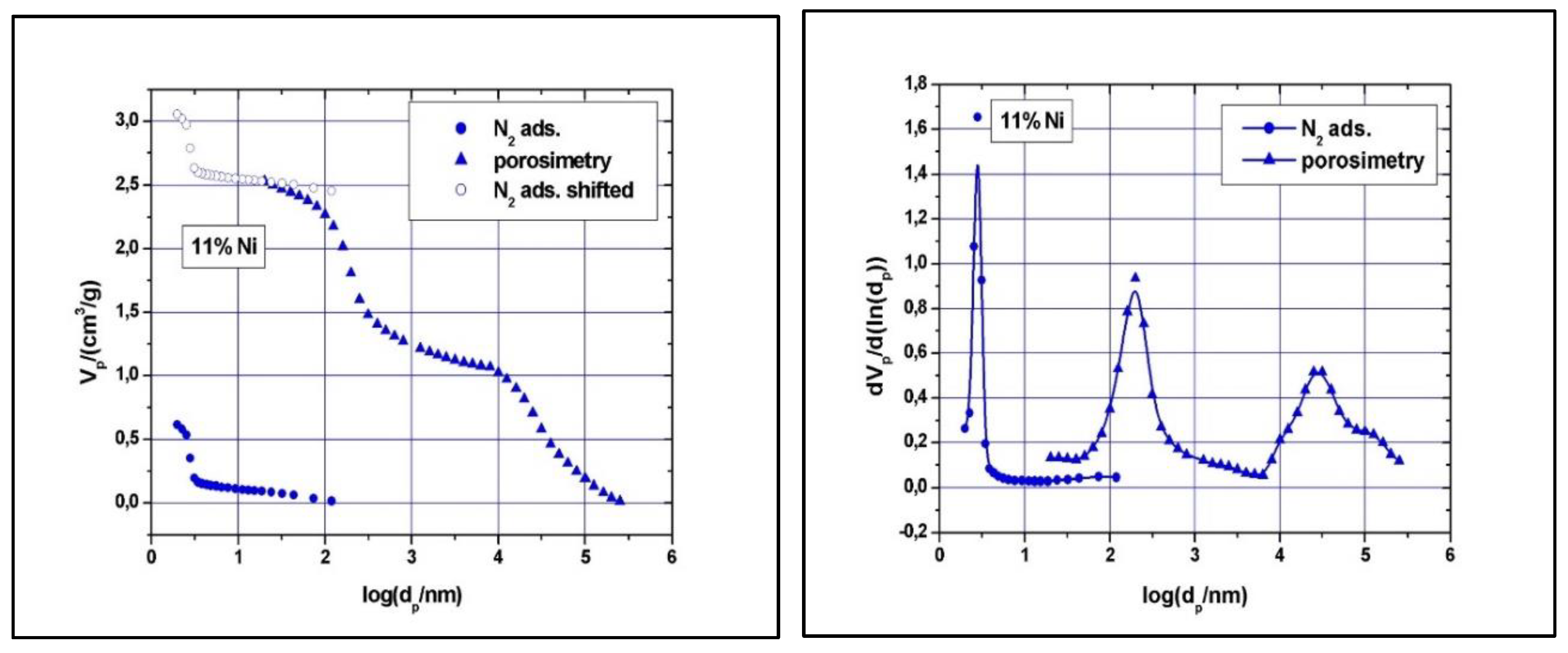

Clear type IV with H1 hysteresis loop nitrogen physisorption curves, similar to the one of SBA-15, were observed (results not shown). Although narrow pore size distributions were detected (see

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), the main mesopore size decreased to about 2.6 nm, while the mesopores volume decreased to about 0.74 cm

3/g as the Ni loading was increased at 11 wt %. The measured BET surface area was 547 m

2/g for the 5% Ni sample and 506 m

2/g for the 11% Ni one (

Table 1). The significant reduction in specific surface area, pore volume and size with increasing Ni loading implies some local blockage of the pore channel induced by depositing Ni species at the pore entrance or at the wall’s surface and/or partial structural degradation, which can take place under higher Ni loading. The structural degradation can be assessed by calculating the

dS/V number and compare the value with the one obtained for SBA-15 above. For the 5% Ni sample, this number is 2.3, while for the 11% Ni sample is 1.8, clearly indicating that the structure suffered some degree of degradation if compare with SBA-15, for which the

dS/V number is 4.3. If the impregnation led to the inclusion of nickel species in the wall by isomorphous substitution of silicon (Si

4+ ion radius, 0.41 Å, Ni

2+ ion radius, 0.69 Å), instead of unit cell contraction, an expansion would be observed. As the Hg-intrusion results show (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), there is a slight decrease in the macropores’ diameter as well, especially for those in the region of 50 – 300 nm, and a broader size distribution, especially for macropores with diameter in the 10 – 175 μm region. These changes are caused, in our opinion, by the deposition of nickel within the intra-particle voids as well.

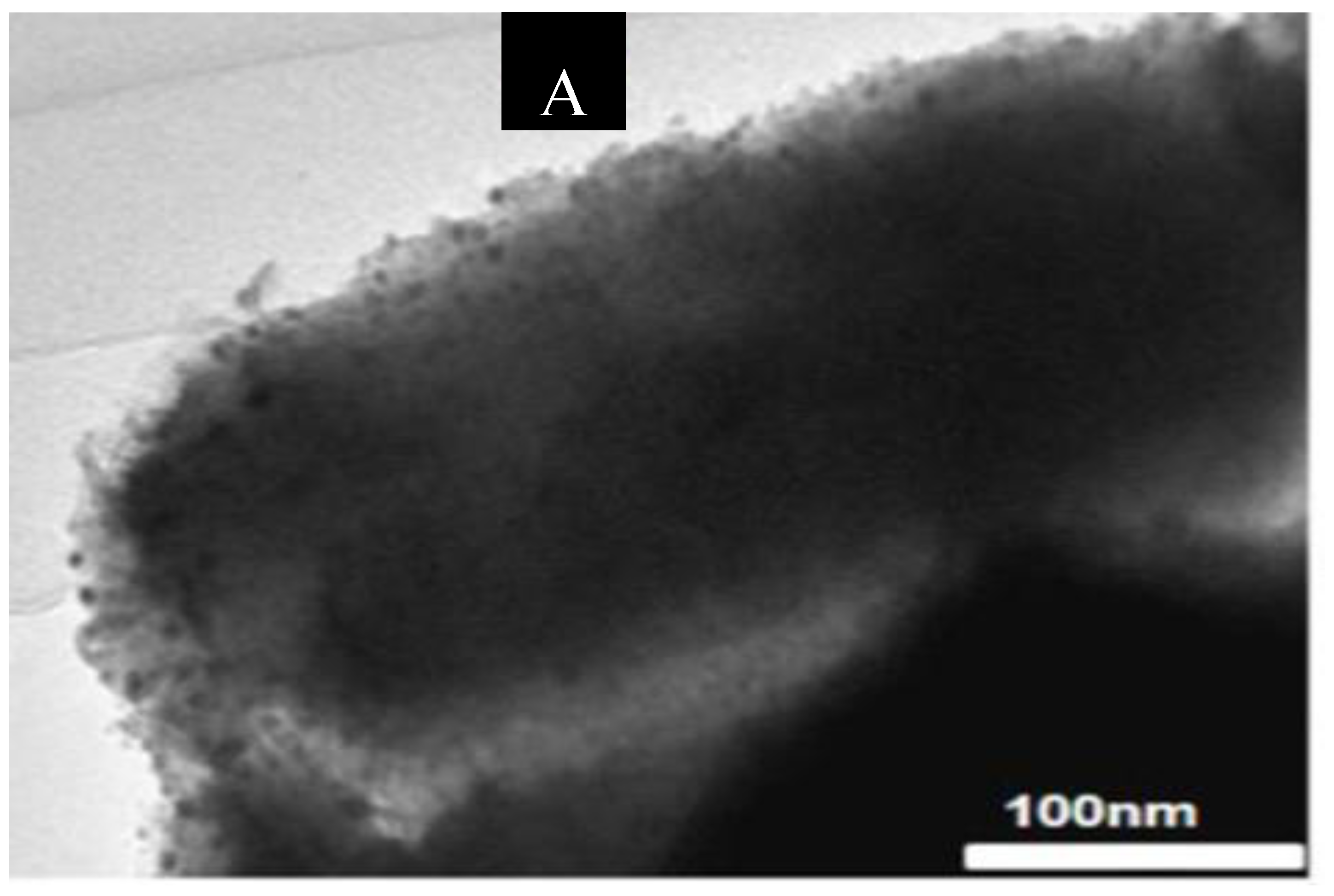

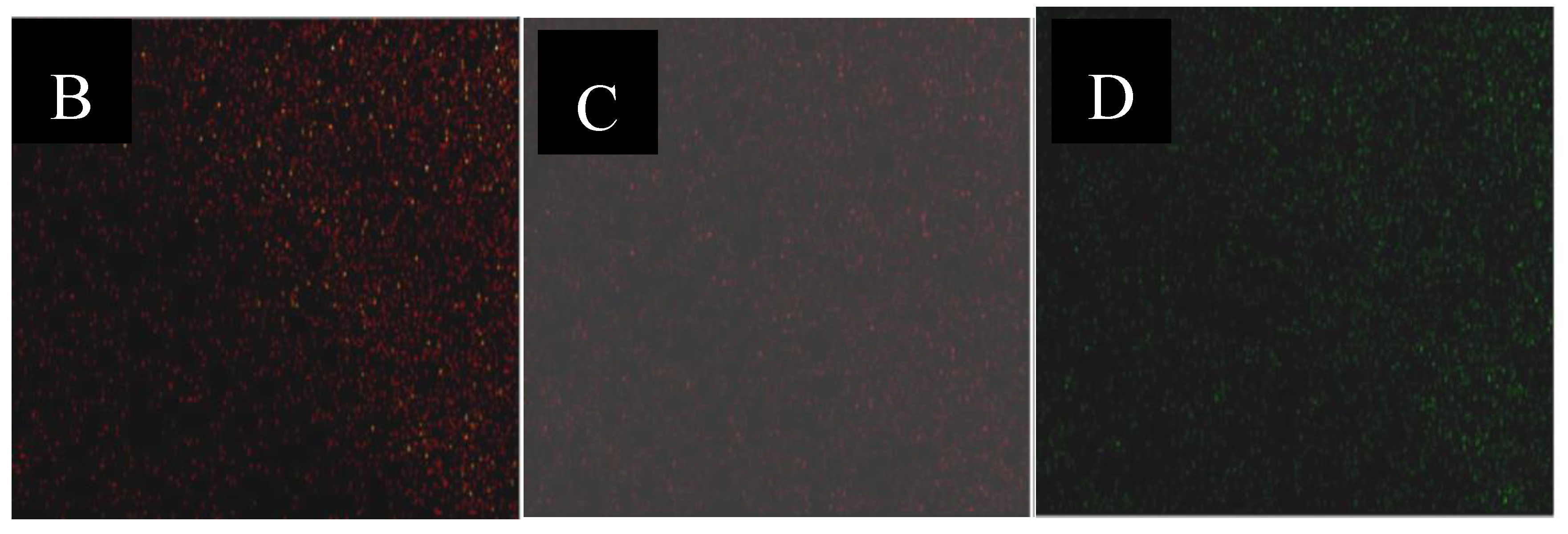

TEM measurements over the two Ni samples (

Figure 9) confirmed that the highly ordered mesoporous structure was maintained after the impregnation process and that the nickel species were uniformly distributed over the support, as XRD results have already revealed.

Figure 9 shows the TEM micrograph of a selected area on the sample 5% Ni (A) and the chemical mapping of the same area (B, C, D). The TEM micrograph reveals that most of the nickel is located inside the pores. However, small amount of nickel is present on the external surface. This means that the Ni oxide particles are larger than the diameter of the SBA-15 mesopore. TEM images for the 11% Ni sample were similar (not shown).

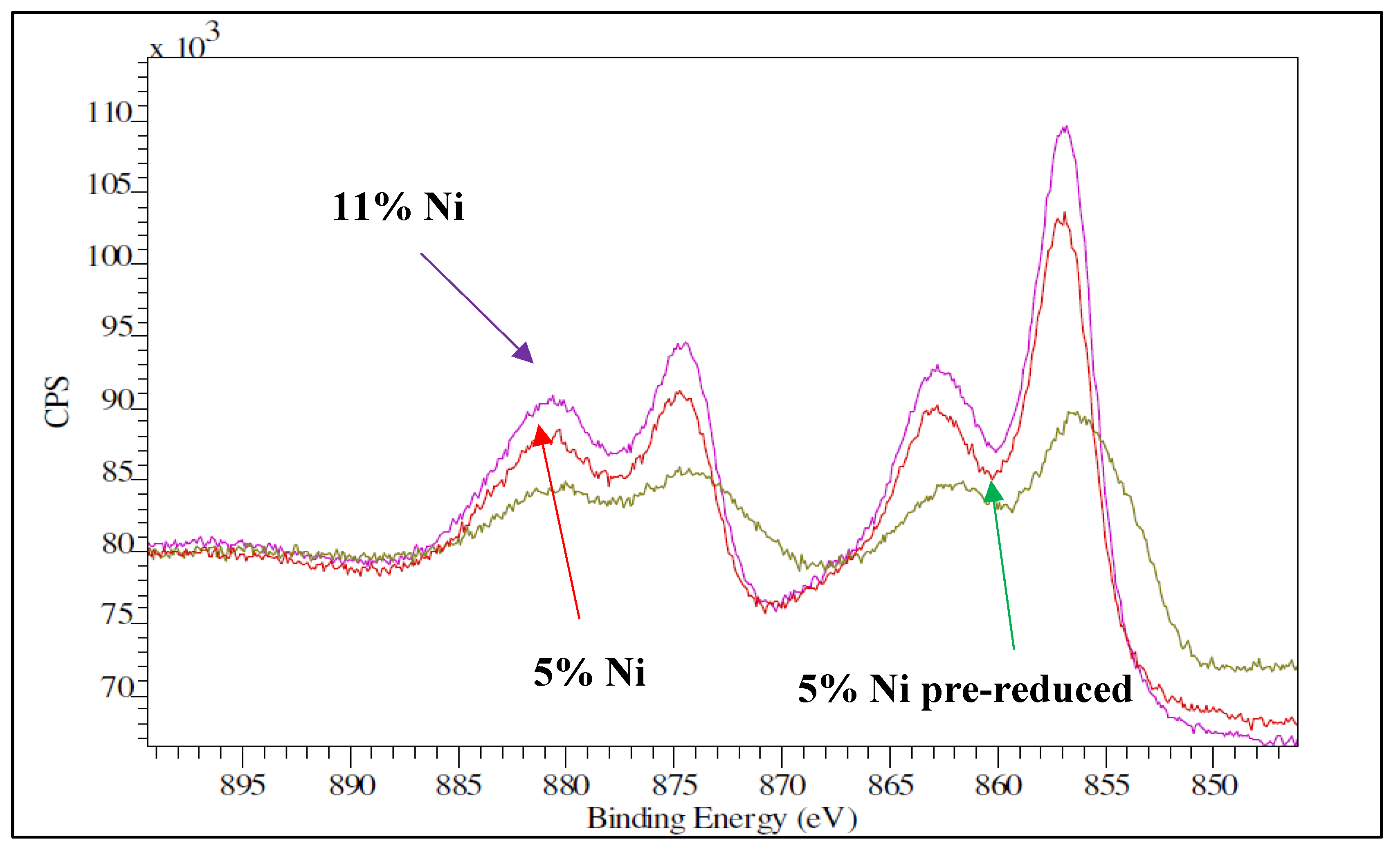

To further confirm the good dispersion of nickel oxide over the SBA-15 support, XPS measurements were performed for the two catalyst’s samples. Because of the high porosity of SBA-15, depth with XPS is in the order of 5-10 nanometers (equivalent to 2-4 cylindrical pores).

Figure 10 shows the XPS spectra for the Ni 2p region of the two as-synthetized samples along with the spectra of the 5% Ni pre-reduced one. The main Ni peaks in the fresh samples are the Ni 2p

3/2 peak at 856.1 eV, and the Ni 2p

1/2 at 874.5 eV, as well as their corresponding shake-up resonances at 863.1 and 880.2 eV. These peaks are assigned to oxidized nickel in a disperse phase [

31]. From the XPS analysis, the atomic Ni/Si surface ratio was 0.13 for the 5% Ni sample and 0.17 for the 11% Ni one. From the EDX analysis, the atomic Ni/Si bulk ratio was 0.06 and 0.08, respectively. These results confirmed again the well dispersion of nickel species for both loadings, as the Ni/Si (surface) to Ni/Si (bulk) ratio is higher than 1. What is more, the XPS data obtained over the pre-reduced samples confirmed that the dispersion was not significantly altered by reduction; the Ni/Si ratio was 0.09 for the 5% Ni sample and 0.13 for the 11 % Ni one.

Trying to comprehend even better the excellent dispersion of the nickel species over the support, we also looked at the influence of the impregnation and drying conditions on the metal distribution. It is generally understood that it is possible to control the structure, shape and metal content when preparing heterogeneous catalysts by dry and wet impregnation. There are four main categories of metal profiles obtained by impregnation of the active phase into supports: uniform, egg-yolk, egg-shell and egg-white. The choice of optimal metal profile in the support is determined by the required activity and selectivity, and by other characteristics of the chemical reactions (kinetics, mass transfer) [

32].

For the dry reforming of methane application, we were interested on a uniform metal profile, as this profile proved to confer high activity and thermal stability of the catalyst. The ratio of the bulk solvent volume to the support volume has a significant effect on the metal distribution during the impregnation process, and this effect is more pronounced for wet impregnation than for dry support impregnation. But at the same time, this effect can be controlled and optimized, by controlling the volume of the solvent. Therefore, the wet impregnation method was used in this study. Preliminary experiments concluded that using a bulk solvent volume: support volume ratio of 10-15:1 would result on a uniform metal profile. Consequently, a 13:1 ratio was used for this study. The precursor plays an important role as well on the active phase dispersion. We choose nickel acetate as precursor because it was found that acetate has a stronger interaction with the support

The concentration profile of the impregnated compound also depends on the mass transfer conditions within the support’s pores during impregnation and drying. With this in mind our choice for the SBA-15 as support was obvious. Using an optimised method, SBA-15 with high internal surface area and high thermal stability was prepared, as described below. Vacuum drying was chosen to avoid the collapse of the well-ordered mesoporous structure. In the case of mesoporous SBA-15, the impregnation solution should be easily sucked up by the mesoporous channels and generally fill the pores quickly, due to the capillary pressure [

33]. However, as we expected that the SBA-15 support could lose some of its hydrophilicity by calcination, resulting in relatively low hydroxyl density, causing the incomplete wetting and thus, leading to inhomogeneous filling of pores during impregnation, the calcined SBA-15 sample was rehydrated in boiling water for 2 h.

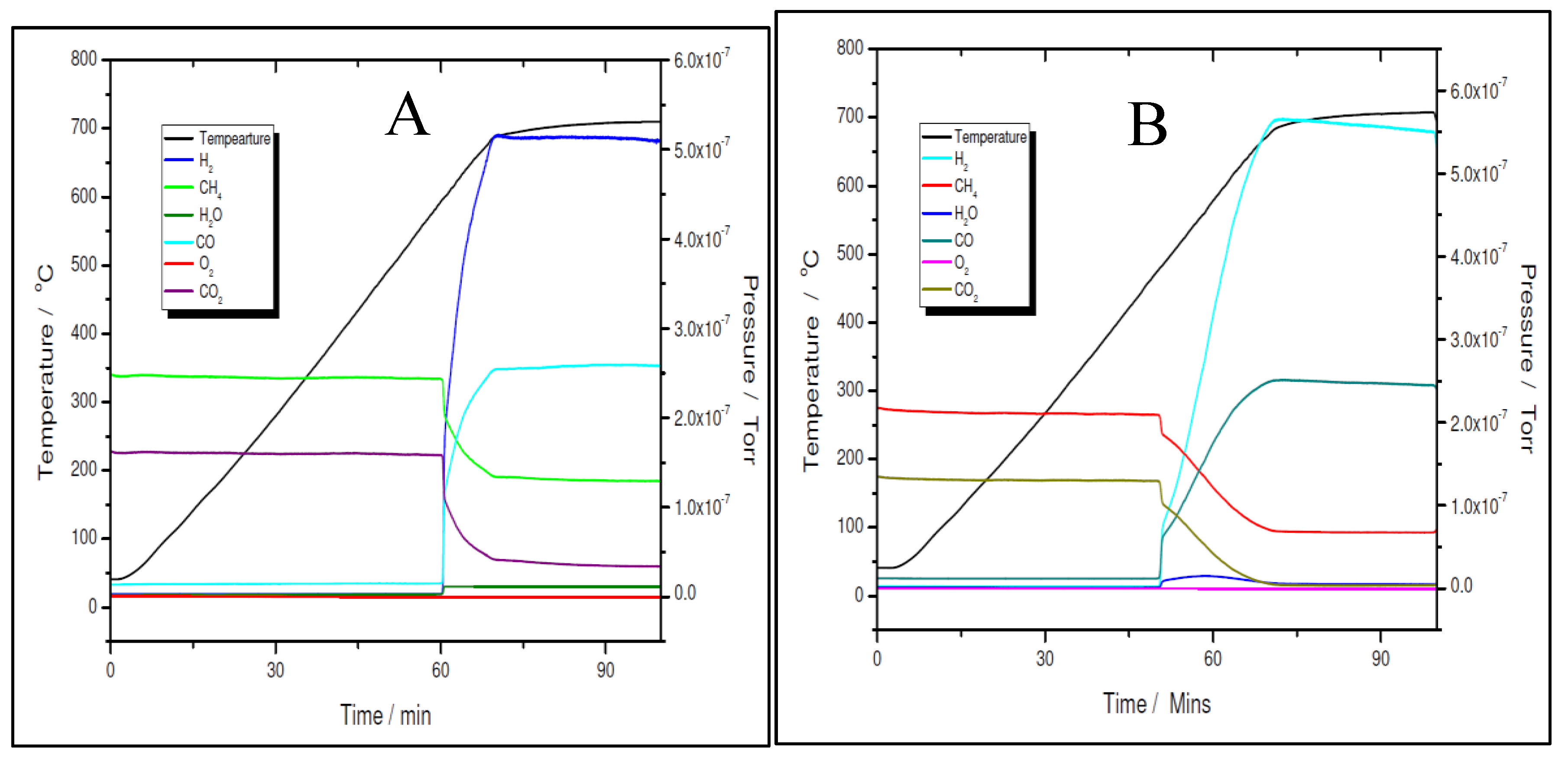

The activity and selectivity towards the dry reforming of methane reaction of the two nickel samples was tested via temperature programmed reaction (TPRx), with CH

4:CO

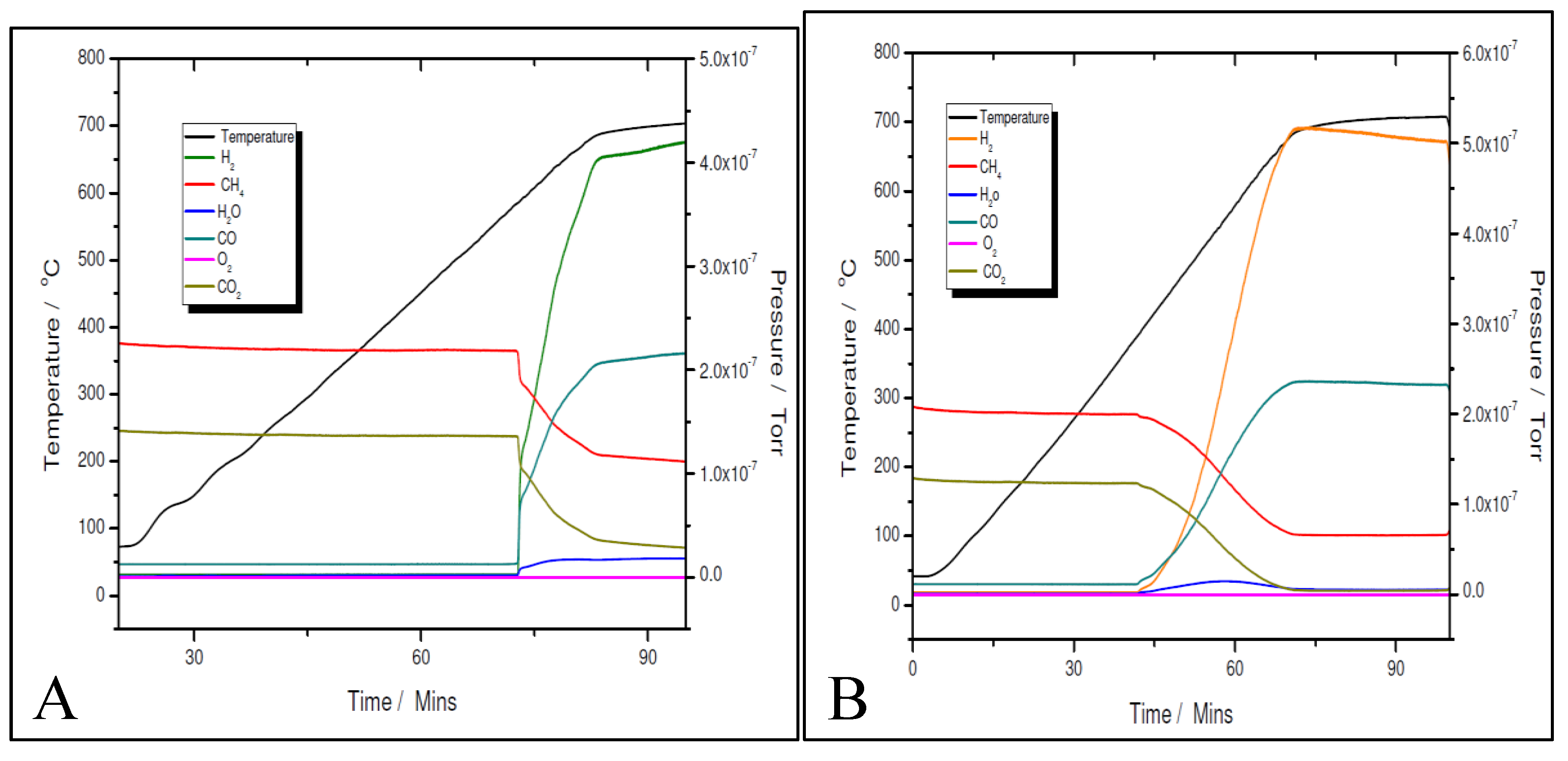

2 = 1.5:1 mixtures. As shown in

Figure 11 A and B for the 5% Ni sample and

Figure 12 A and B for the 11% Ni one, both fresh (as-synthesised) and pre-reduced catalyst’s samples proved to be very active.

However, for both loadings, the pre-reduced samples were more active than the fresh ones. As for example, for the 5% Ni loading, the pre-reduced sample starts to produce H2 and CO at 480 ºC, while the fresh one must exceed 600 ºC to start to convert the reactants. While for the pre-reduced sample almost complete CO2 conversion was obtained around 680 ºC, for the fresh one, only 75% CO2 conversion was obtained at this temperature. A slightly improved catalytic activity was observed for both 11% loading samples. The fresh 11% Ni sample starts to convert the reactants around 580 ºC, while for the pre-reduced sample, the reaction was initiated at temperature as low as 380 ºC with complete CO2 conversion at the same temperature as that for the 5% Ni pre-reduced sample, i.e., 680 ºC. The CO2 conversion over the fresh sample at 680 ºC was the same as for the fresh 5% Ni sample. Therefore, the only difference in activity between the two catalysts was in terms of their initial activity. The 11% Ni pre-reduced sample was slightly more active as it starts to convert the reactants at 380 ºC, about 100 ºC less than the 5% Ni pre-reduced one. Obviously, by increasing the Ni loading, the number of active sites increased, which explains the earlier start of the reaction over the 11% Ni pre-reduced sample. However, as the maximum performance was obtained at the same temperature for both pre-reduced samples, one can conclude that the active species/sites were the same for both loadings.

A more careful analysis of the TPRx data (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) revealed that while CH

4 and CO

2 are not adsorbed on the fresh catalysts at temperatures lower than the starting reaction temperatures, for the pre-reduced samples, some adsorption (about 5 mol% of both, CH

4 and CO

2) is noticed as the samples are heated up.

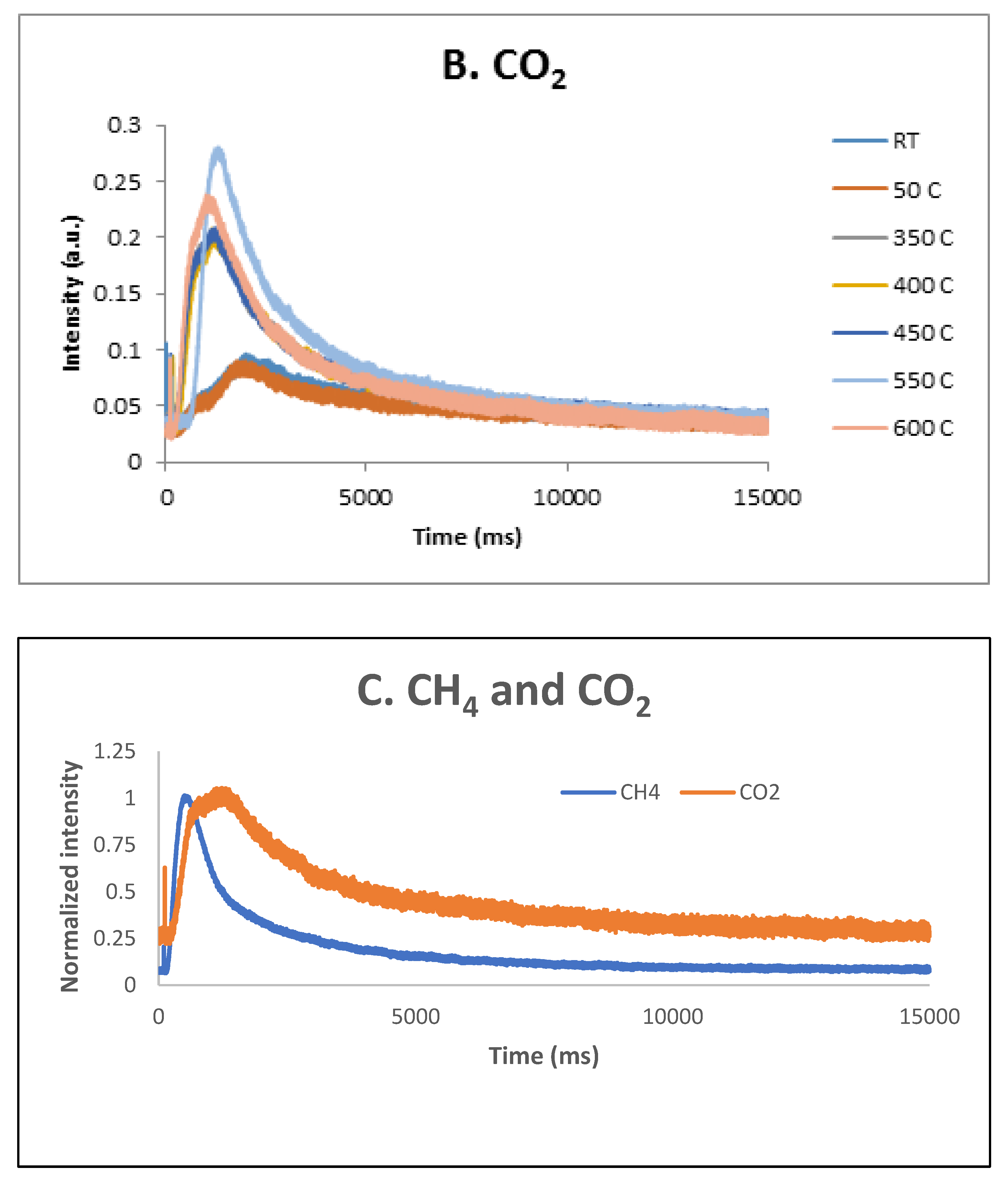

These results were confirmed by the TAP measurements as well. As previously reported [

34], over the fresh 5% Ni sample, both CH

4 and CO

2 were only weakly and reversible adsorbed at temperatures lower than 600 ºC. Additional TAP measurements were performed over the pre-reduced 5% Ni sample while single pulses of a CH

4:CO

2 = 1.5:1 mixture were sent over the catalyst, at temperatures varying between room temperature and 600 ºC. The results are presented in

Figure 13 A, B and C, respectively. It seems that CO

2 is physically adsorbed at low temperatures and slightly chemisorbed at high temperatures, while CH

4 is only slightly chemisorbed at high temperatures. At 600 °C, a broader peak CO

2 response was observed suggesting that the CO

2 interaction with catalysts was stronger than the CH

4 one.

As the TPRx data revealed, both catalyst’s samples are very active. The well dispersion of the nickel species over the support was, in our opinion, responsible for their very high activity. To the best of our knowledge, no Ni-based catalysts with almost complete CO

2 conversion at temperatures lower than 800 ºC were reported so far. Although Ni/SBA-15 catalysts have been already reported [

29,

35], their catalytic activity towards DRM reaction was much lower than that of the samples of this study. As for example, the CO

2 conversion at 700 ºC was between 68% and 75%, as the Ni loading was increased from 2.5% to 20%. For a 5% Ni/SBA-15 catalyst, prepared by wet impregnation method (same as the one used in this study) but using nickel nitrate as Ni precursor, the reported CO

2 conversion at 700 °C is 65% [

36]. It is clear evidenced the effect of the Ni precursor. And, as mentioned above, the nature of the precursor is one of the factors responsible for the Ni dispersion. To understand why and how the Ni dispersion is affected by the nature of the precursor, we took a deeper look at the drying process during catalyst’s preparation.

In accordance with literature data [

33], the physical picture of drying can be described as follows: as drying proceeds, the solution of the precursor with low surface tension could diffuse deeply at first and be transported toward the internal surface of the mesoporous channels via capillary forces; towards the end of drying, the enhanced viscosity could lead to a strong interaction with the internal surface of the support and inhibit the redistribution of the impregnation solution during drying, thus favouring a uniform distribution of the active component in the mesoporous channels. In contrast, the solution of the precursor with higher surface tension has a weak interaction with the support, and the concentrated solvent sucked up by the mesoporous pores could be back diffused by higher surface tension and migrate toward the external surface of the mesoporous channels, resulting in a concentration build-up on the external rim of the support. As a consequence, inhomogeneous distributions of the precursor appeared. Knowing that the surface tension of acetic acid is lower than that of nitric acid, i.e., 0.028 N/m compared to 0.04115 N/m at 20 °C [

37,

38] our choice of nickel acetate tetrahydrate as Ni precursor was obvious and homogeneous impregnation was obtained as expected.

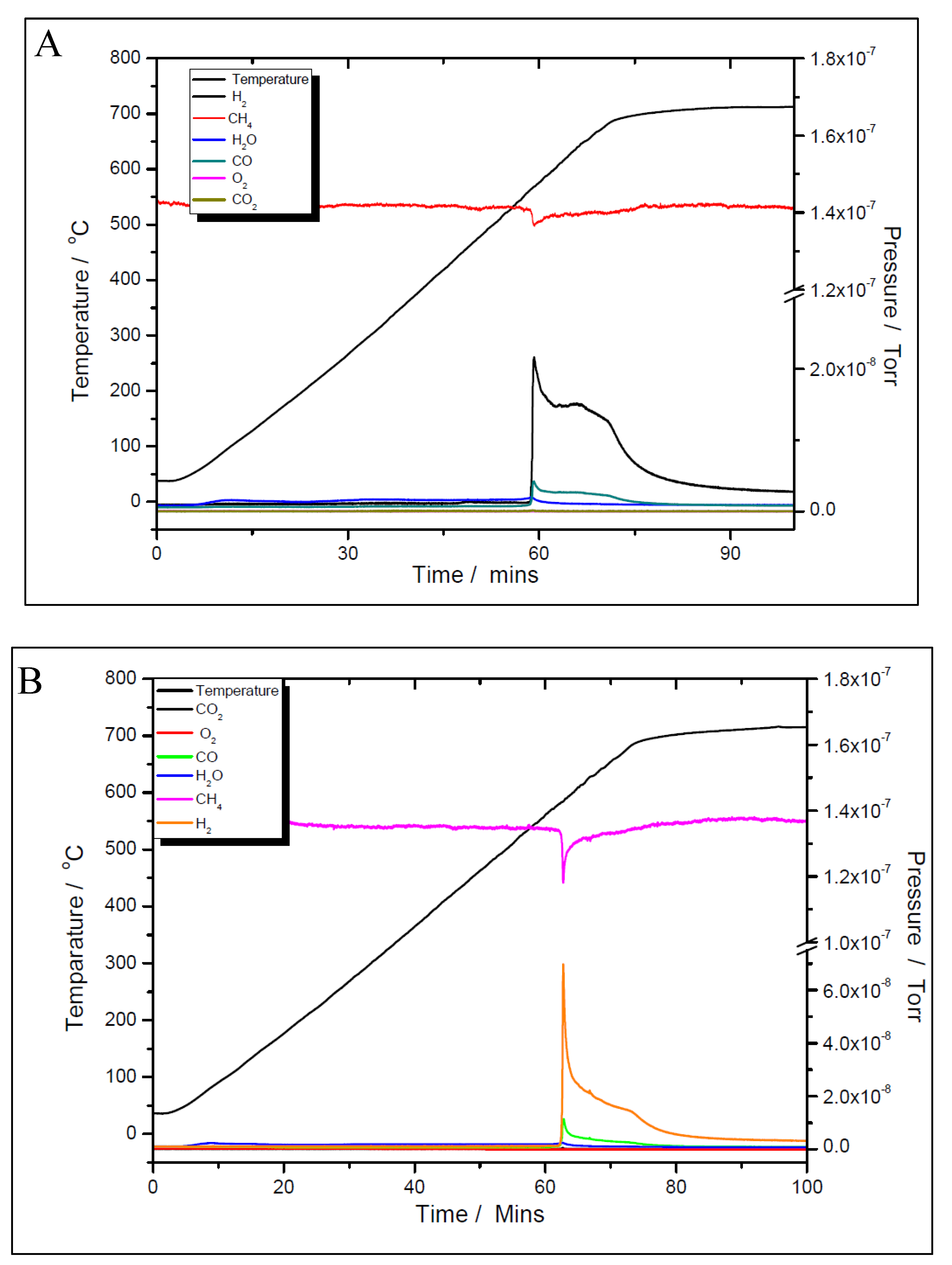

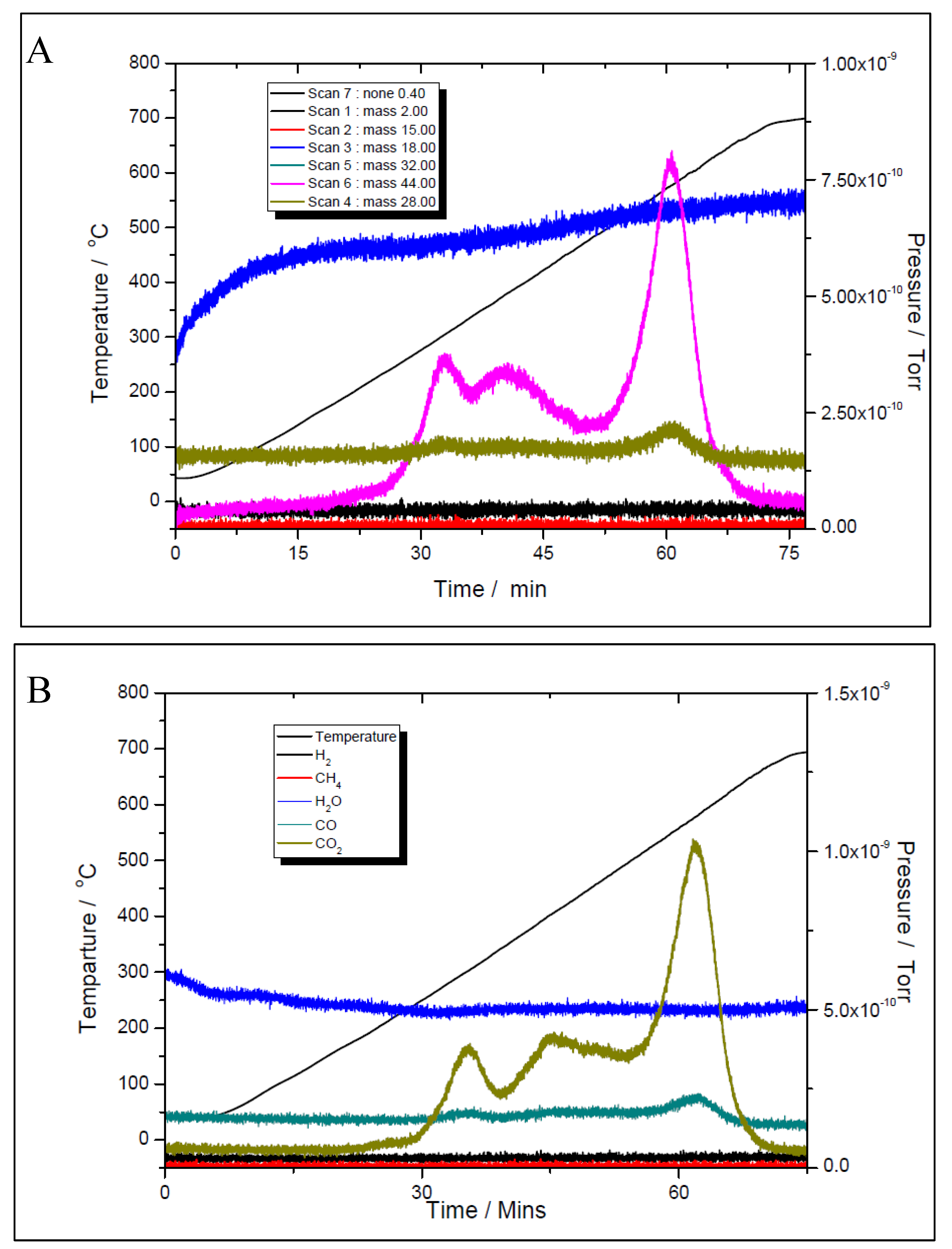

Although the prepared catalyst’s samples proved to be very active at low temperatures, there was another challenge to address. As seen in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, the amount of hydrogen produced was almost double than the amount of carbon dioxide. This means that besides the main reaction, the catalysts favoured the methane decomposition as well, which, unfortunately might have led to the carbon deposition over the surface, and in time, to the deactivation of catalyst (not seen in the above figures). On the other hand, small amounts of water were noticed as well. This can be ascribed to the simultaneous occurrence of the reverse water-gas shift reaction. To support these assumptions, temperature programmed CH

4 decomposition (reduction) (

Figure 14A and

Figure 15A) followed by temperature programmed oxidation (TPO) (Figures 14B and 15B) measurements were also performed on both fresh samples. For both samples, the methane activation reaches its maximum at 580 ºC. The TPO measurements showed that for both samples, three CO

2 peaks are present, meaning that three carbon species were formed during methane decomposition. Along with carbon dioxide some carbon monoxide was formed and almost constant, though higher for the 5% Ni sample, amount of water was also released. The formation of CO indicates that the carbon species, formed by the dissociation of CH

4, react rapidly with oxygen species from the catalyst. This is another evidence that the presence of carbonaceous species will not contribute to the catalyst’s deactivation.

The three surface carbon species, labelled as C

α, C

β and C

γ, respectively, showed various mobility, thermal stability, and reactivity [

36]. The peaks’ temperatures were the same for both Ni loadings, i.e., 280, 400 and 580 °C, respectively. The distribution and features of these carbonaceous species sensitively depend on the nature of the transition metals and the conditions of methane adsorption. These carbonaceous species can be described as: completely dehydrogenated carbidic C

α type, partially dehydrogenated CH

x (1 ≤ x ≤3) species, namely C

β type, and carbidic clusters Cγ type (formed by the agglomeration and conversion of C

α and C

β species under certain conditions). Their reactivity was assessed by performing TPSR with hydrogen [

35]. Similar results with those obtained from TPO measurements of this study were obtained. A fraction of the surface carbon species, which might be assigned to carbidic C

α (~188 °C), were mainly hydrogenated to methane at temperatures even below 227 °C. This showed that carbidic C

α species are rather active and thermally unstable on the nickel surface. The carbidic C

α species were suggested to be responsible for CO formation. A significant number of surface carbon species were hydrogenated to methane below 327 °C and were assigned to partially dehydrogenated C

β species. Most of the surface carbon was hydrogenated above 527 °C and was attributed to carbidic clusters Cγ [

39].

As all those three carbonaceous species were rather active, being converted to carbon dioxide at temperatures lower than the starting temperature of CO

2 reforming, one can assume that they will not contribute to the catalyst deactivation. To support this statement, post-reaction temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO) experiments were carried out by exposing the spent catalysts to 5% oxygen in helium flow in order to determine the amount of carbon formed during the DRM reaction, run for 200 min at 600 °C. No CO

2 peaks were observed for either of the samples. In addition, in this TPO experiment, there was no signal for water which was in line with previous work [

40]. What is more, a transient study on the dry reforming of methane showed that when both reactants are fed contemporaneously the presence of CH

X species promotes the CO

2 activation that is responsible for the reforming reaction [

41]. Our understanding is that the uniform distribution of the metal component throughout the oxide support with high surface area helped to reduce coking by physically separating carbon species formed on the nickel surface. That is, carbon species must be formed if the main reaction is to proceed, but prevention of polymerization by separating the carbon species should reduce coking while leaving the main reaction unaffected [

42].