Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Literature search strategy and selection criteria of articles

3. Results

- TAG oil studies (fish oil, re-esterified fish oil, blended fish oil, sardine/anchovy oil, algal oil, n=6 studies). The variability, expressed as CV for the AUC or iAUC, for EPA, DHA or EPA+DHA in plasma TAG or PL ranged from 38% to 102%, with 7 of 10 data points exceeding 50%. These studies involved from 7 to 27 subjects over periods from 8h to 72h and used doses which ranged from 415mg up to 1700mg of EPA+DHA [12,14,15,16,17,29].

- PL-rich oil studies (krill oil, PL-enhanced fish oil, polar-rich algal oil, n=6 studies). The variability, expressed as CV for the AUC or iAUC, for EPA, DHA or EPA+DHA in plasma TAG or PL ranged from 28% to 76%, with 5 of 9 data points exceeding a CV of 50%. These studies involved from 10 to 24 subjects over periods from 10h to 72h and used doses which ranged from 206mg up to 1700mg of EPA+DHA [12,15,18,19].

- FFA studies (Epanova, OM3-CA, unspecified, n=3 studies). The variability, expressed as CV for the AUC or iAUC, for EPA, DHA or EPA+DHA in plasma ranged from 34% to 53%, with 3 of 5 data points equal to or exceeding a CV of 50%. These studies involved from 14 to 26 subjects over 24h and used doses which ranged from 3264mg up to 4000mg of EPA+DHA [20,21,22].

- Monoacylglycerol (MAG) studies (2-MAG, 1(3)-MAG, MAG unspecified, n=3 studies). The variability, expressed as CV for the AUC, for EPA, DHA or EPA+DHA in plasma ranged from 19% to 93%, with 2 of 4 data points equal to or exceeding a CV of 50%. These studies involved from 7 to 24 subjects over 24h and used doses which ranged from 1247mg up to 3000mg of EPA+DHA [17,21,23].

- Ethyl ester of LC omega-3 studies (Omacor, KD Pharma or unspecified sources, n=9 studies). The variability, expressed as CV for the AUC or iAUC, for EPA, DHA or EPA+DHA in plasma or plasma PL ranged from 32% to 154%, with 9 of 12 data points exceeding a CV of 50%. These studies involved from 10 to 40 subjects over 24h to 72h and used doses which ranged from 680mg up to 3360mg of EPA+DHA [15,20,21,23,24,25,26,27,28].

- Wax ester study (Calanus finmarchicus oil, n=1). The variability, expressed as CV for the iAUC, for EPA+DHA in plasma was 42%. This study involved 18 subjects over 72h and used a dose of 416mg of EPA+DHA. Wax esters are considered mostly undigestible due to the poor efficacy of the carboxylester lipase and the poor solubility of the wax esters. However, this study showed that the bioavailability of the wax esters was similar to that of the comparative EE group [27].

- Ethyl esters with enhanced emulsification properties (n=4 studies). The variability, expressed as CV for the AUC or iAUC, for EPA, DHA or EPA+DHA in plasma or whole blood ranged from 31% to 137%, with 4 of 6 data points exceeding a CV of 50%. These studies involved from 12 to 40 subjects over 24h to 72h and used doses which ranged from 374mg up to 1680mg of EPA+DHA. The data revealed that the enhanced emulsification properties significantly improved the bioavailability of the EE compared with standard EE, as judged by the AUC, but variability was still evident [24,25,26,29].

- Whole food studies (TAG) (herring, oils, foods with fish oil, novel foods, n=4 studies). The variability, expressed as CV for the iAUC for EPA, DHA or EPA+DHA in ranged from 21 to 138%, with 7 of 10 data points exceeding a CV of 50%. The studies involved from 17 to 27 subjects over 6h to 24h and used doses which ranged from 415mg up to 3200mg of EPA+DHA. These studies demonstrated that the food matrix did not alter the highly variable postprandial plasma LC omega-3 responses to whole food containing TAG-rich in LC omega-3 [14,30,31,32].

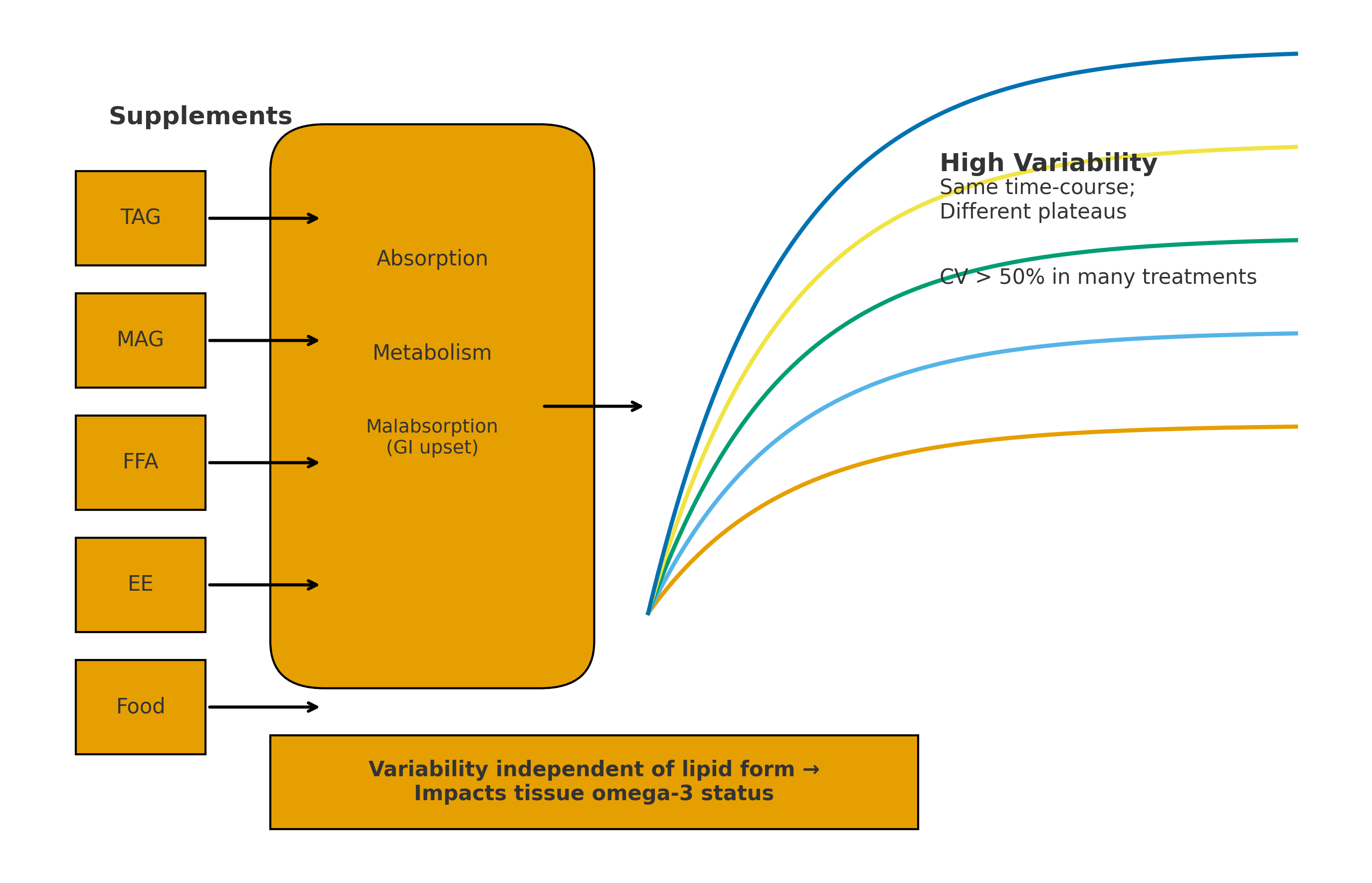

- In summary, the variability in the plasma or blood LC omega-3 levels of the 21 postprandial studies revealed that there was significant variability in the data independent of the type of lipid supplement. More than 64% of the treatments had a CV in excess of 50% for the AUC or iAUC for plasma EPA, plasma DHA, whole blood EPA+DHA or plasma EPA+DHA (Table 1).

4. Discussion

- Lipases and carboxylesterases. LC omega-3 lipid supplements requiring enzymatic digestion (TAG, PL, ethyl esters and wax esters) all showed substantial variability (72% of treatments had CV>50%). This implies/indicates that within these studies there were individuals with either high, medium or low plasma accretion of LC omega-3. This suggests variability in the lipid digesting enzymes and/or the micelle formation which facilitate the enzymatic processes. To partially address the issue of micelle formation, it was shown that the ethyl ester preparations with enhanced micelle formation properties led to significantly higher plasma LC omega-3 accretion than ethyl esters, however despite this, the enhanced preparations still showed high CV values (31-115%). Thus, factors other than micelle formation are likely playing a role in the observed variability. In the case of those individuals with putatively low plasma LC omega-3 accretion, some of the undigested LC omega-3 oils will lead to malabsorption of the oils meaning the undigested lipids will pass into the large bowel and be subject to faecal excretion.

- Lipid digestion products (FFA and MAG). These lipid products also showed considerable variability in their accretion into plasma (67% of treatments had CV>50%). Again, there will be individuals with either high, medium or low plasma accretion of LC omega-3 and in the latter case the malabsorption will mean some of these unabsorbed products (FFA & MAG) will pass into the large bowel and be excreted.

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LC omega-3 | Long chain omega-3 |

| TAG | Triacylglycerol |

| PL | Phospholipids |

| FFA | Free fatty acids |

| MAG | Monoacylglycerol |

| EE | Ethyl esters |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| iAUC | Incremental Area Under the Curve |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| RBC | Red Blood Cell |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| DPA | Docoapentaenoic Acid |

Appendix A

| Supplement type |

Dose & subject details |

Study details |

Postprandial CV for the AUC/iAUC |

Comments | Reference |

| TAG oils | |||||

| TAG (fish oil) | 1700 mg EPA+DHA, n=15 (8F, 7M) healthy adults from northern Finland. | 72-h study, with breakfast (29g fat), standardised lunch, dinner and supper. |

CV for iAUC Plasma PL EPA+DHA 59.2±22.2 (SD), CV= 38% Plasma TAG EPA+DHA 35.0±26.5 (SD) CV= 76% (iAUC % x h). |

Nine adverse events: 1 after fish oil, 5 after krill meal and 3 after the fish oil (note double entries for fish oil which might be an error). Most events were classified as mild, and included loose stools. | Kohler et al. 2015 (12) |

| Re-esterified fish oil, (rTAG) | 1680mg EPA+DHA, n= 12 (M) healthy adult from Germany. | 72-h study, capsules with breakfast (30.1g fat). Standardised meals consumed throughout study. |

CV for AUC Plasma PL EPA+DHA, 59.8±36.8 (SD), CV= 62%. (AUC - % x h). |

Adverse events not mentioned | Schuchardt et al. 2011 (15) |

|

TAG (blended fish oil) |

452 mg EPA+DHA, n=20 (10F, 10M) healthy young adults from the UK. | 8-h study with breakfast (49.5g fat). |

CV for iAUC F: Plasma TAG EPA+DHA 63.1±1.8 (SEM) (SD 48.2), CV= 76% M: Plasma TAG EPA+DHA 84.4±7.4 (SEM) (SD 31.7), CV= 38% F: Plasma PC EPA+DHA 159.9±25.1 (SEM) (SD 112.2), CV= 70% M: Plasma PC EPA+DHA 167.7±30.3 (SEM) (SD 135.4) CV= 81% (iAUC umol/L x h). |

No reported adverse effects were reported during trial | West et al. 2019 (16) |

| TAG (fish oil) | 4.5g fish oil (19.8% EPA, 7.9% DHA, 1247mg EPA+DHA), n=7 healthy subjects from the UK. | 24-h study, no breakfast. |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA 25.3±11.2 (SD), CV= 44% (no units provided for AUC) |

Did not report any adverse effects | Wakil et al. 2010 (17) |

| PL-rich oils | |||||

| PL-rich (Krill oil) | 1700 mg EPA+DHA as krill oil, n=15 (8F, 7M) healthy adults from northern Finland. | 72-h study, with breakfast (29g fat), standardised lunch, dinner and supper |

CV for iAUC Plasma PL EPA+DHA 89.1±33.4 (SD), CV= 38% Plasma TAG EPA+DHA 24.5±17.6 (SD), CV= 76% (iAUC % x h). |

Adverse events mild. One subject reported increased defecation. | Kohler et al. 2015 (12) |

|

PL-rich (Krill oil) |

1680mg EPA+DHA, n= 12 M healthy. from Germany. | A 72-h study, capsules with breakfast (30.1g fat). Standardised meals consumed throughout study. |

CV for AUC Plasma PL EPA+DHA 80.0±34.7 (SD), CV= 43% (AUC % x h). |

KO had high FFA levels containing EPA and DHA (22%, 19% of total content, respectively). Adverse events not mentioned | Schuchardt et al. 2011 (15) |

| PL-rich (Krill oil) | 206mg EPA+DHA, n=24 (14F, 10M), healthy subjects from USA (48% non-Hispanic/Other, 52% Hispanic/Latino). | A 24-h study, no breakfast just water. Low fat lunch/dinner |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA+DHA 448±248 (SD) CV = 55% (iAUC nmol/ml x hr) |

One adverse event - upper resp tract inf. – judged to be unrelated to treatment. | Guarneiri et al. 2023 (18) |

| PL-enhanced Fish oil | 337mg EPA+DHA, n=24 (14F, 10M), healthy subjects from USA (48% non-Hispanic/Other, 52% Hispanic/Latino).. | A 24-h study, no breakfast just water. Low fat lunch/dinner |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA+DHA 440±286 (SD) – CV = 65% (iAUC nmol/ml x hr) |

One adverse event - upper resp tract inf. – judged to be unrelated to treatment. | Guarneiri et al. 2023 (18) |

| PL-rich (Krill oil) | 1.02g EPA, 0.54g DHA, n=10 (10M), healthy subjects from Germany. | A 10-hr study, 55g breakfast |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA 137±39 (SD), CV= 28% Plasma DHA 70±39 (SD), CV= 56% (iAUC ug/ml/hr) |

Adverse events not mentioned | Kagan et al. 2013 (19) |

| Polar rich algal oil (incl. glycolipids & PC) | 1.5g EPA, n=10 (M), healthy subjects from Germany. | A 10-hr study, 55g breakfast |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA 277±135 (SD), CV= 49% Plasma DHA 65±45 (SD) CV= 69% (iAUC ug/ml/hr) |

Adverse events not mentioned | Kagan et al. 2013 (19) |

| FFA | |||||

| FFA (Epanova) | 4 x 1g cap of each type. FFA contained 0.55g EPA, 0.22g DHA/g. Dose = 2200mg EPA, 880 mg DHA, n=26 healthy subjects from USA (3 non-Hispanic/Other, 23 Hispanic/Latino). |

24-h study, low fat breakfast (<10%en fat). The study was conducted at the end of 2-week trial taking 4g FFA/day. |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA + DHA geom mean 19.1, CV= 34% (iAUC nmol x hr/ml) |

Adverse events not mentioned. | Offman et al. 2013 (20) |

|

FFA (OM3-FFA) |

1748mg EPA + 1516mg DHA as FFA, n=24, (15F/9M) normal healthy adults (but finished with n=21-23/group) from Switzerland. | A 24-h study. No breakfast but fat-free lunch & dinner. |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA 1496±734 (SD), CV= 49% Plasma DHA 1356±676 (SD), CV= 50% (AUC nmol-h/ml). |

There were 22 adverse events (mild) reported by 11 subjects including nausea, diarrhea, headache. | Cuenoud et al. 2020 (21) |

| FFA (OM3-CA) probably EPANOVA | 4g EPA+DHA as FFA, n=14 (7F/7M), healthy Chinese subjects. | A 24-h study; supplements consumed with low fat (<10%) breakfast. |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA 975.6±517.3 (SD), CV= 53% Plasma DHA 273.6±144 (SD), CV= 53% (iAUC h x ug/mL) |

In a continuation of the postprandial study, subjects were provided supplement for 14 days, and 6/14 subjects reported at least one mild adverse event (diarrhea). | Jing et al. 2020 (22) |

| MAG | |||||

|

MAG (Maxsimil 3020) |

3000 mg EPA+DHA (1800 mg EPA, 1200mg DHA), n=20 (10F, 10M), healthy subjects from Canada | A 24h study, with breakfast 20% fat |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA+DHA 89.6±17.0 (SD), CV= 19%. (AUC mg/dl x h) |

Did not mention of adverse events. Does not mention positional distribution of MAG. | Chevalier and Plourde 2021 (23) |

|

MAG Enzymatically produced oil followed by distillation, with EPA main FA. |

4.5g MAG oil (19.8% EPA, 7.9% DHA; 1247mg EPA+DHA), n=7 healthy subjects from the UK. | A 24hr study, no breakfast |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA 13.4±12.5 (SD), CV= 93%. (no units provided) |

Did not report any adverse effects | Wakil et al. 2010 (17) |

|

1(3)-MAG |

1655mg EPA + 1275mg DHA, n=24, (15F/9M) normal healthy adults (but finished with n=21-23/group ) from Switzerland. | A 24-h study. No breakfast but fat-free lunch & dinner. |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA 1486±626 (SD), CV= 42% Plasma DHA 1206±600 (SD), CV= 50% (AUC nmol-h/ml). |

There were 22 adverse events (mild) reported by 11 subjects including nausea, diarrhea, headache. | Cuenoud et al. 2020 (21) |

| Ethyl esters (EE) | |||||

| Ethyl esters (Lovanza) | 1860mg EPA, 1500mg DHA. n=26/arm (10F, 16M), healthy subjects from USA (4 non-Hispanic/Other, 22 Hispanic/Latino). | A 24-h study, low fat breakfast (<10%en fat) postprandial study treatment conducted at the end of 2-weeks trial. |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA + DHA 3.32, CV= 76%. (iAUC nmol x hr/ml) |

Adverse events not mentioned | Offman et al. 2013 (20) |

|

Ethyl esters (fish oil origin) |

680mg EPA+DHA, n=30 (20F,10M) from Australia. | A 24hr study, with breakfast (2g fat) |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA+DHA 150.2±40.5 (SEM) (221 SD), CV = 147%. (units not supplied) |

Adverse events not mentioned | Bremmell et al. 2020 (24) |

|

Ethyl esters (GmbH) |

1680mg EPA+DHA, n= 12 healthy M . from Germany. | A 72-h study, capsules with breakfast (30.1g fat). Standardised meals consumed throughout study. |

CV for AUC Plasma PL EPA+DHA: 47.5±38.4 (SD), CV= 81% (AUC % x h). |

Adverse events not mentioned. | Schuchardt et al. 2011 (15) |

|

Ethyl esters (Omacor) |

Ethyl esters 3080mg (1700mg EPA, 1380mg DHA), n=24, F15/M9 normal healthy adults (but finished with n=21-23/group) from Switzerland. | A 24-h postprandial study. No breakfast but fat-free lunch & dinner. |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA: 163±252 (SD), CV= 154% Plasma DHA: 562±695 (SD), CV= 124% (AUC nmol-h/ml). |

There were 22 adverse events (mild) reported by 11 subjects including nausea, diarrhea, headache. | Cuenoud et al. 2020 (21 |

|

Ethyl esters (Omacor) |

1000mg ethyl esters omega-3, n=12 (M) healthy adults from Republic of Korea. | A 72-h study, breakfast, 15-20% fat 20 min before single dose of capsules with 200mL water. |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA 914±464 (SD), CV= 41% Plasma DHA 404±216, CV= 53% (AUC ug/ml x h). |

No adverse events were reported | Kang et al., 2023 (25) |

|

Ethyl esters |

3360mg EPA+DHA, n=40 (20F/20M) healthy adults from Switzerland and the UK. | A 48-h study, no breakfast, capsules consumed with water, but low-fat lunch (<15g) and standard meals thereafter. |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA+DHA 46.96±31.05 (SD), CV= 66%. (iAUC ug x h/mL/g). |

No adverse events were reported. | Qin et al., 2017 (26) |

|

Ethyl esters (Lovaza) |

840mg EPA+DHA as EE, n= 18(9F, 9M) from USA. | A 72-h study, breakfast with 23g fat |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA+DHA 764±93 (SEM) (395 SD), CV= 52%. (iAUC ug x h/mL) |

No significant changes in GI symptoms over study period | Cook et al. 2016 (27) |

|

Ethyl esters (no brand mentioned) |

3g EPA+DHA 1800 mg EPA, 1200mg DHA, n=20 (10F, 10M), healthy subjects from Canada. | A 24h study, with breakfast 20% fat |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA+DHA 38.4±12.4 (SD), CV = 32%. (AUC mg/dl x h) |

Did not mention of adverse events. | Chevalier and Plourde 2021 (23) |

| EPA and DHA ethyl esters (KD Pharma) | 2024mg EPA, 1921 mg DHA (oil form), n=10 (M) healthy subjects from Germany. | A 72-h cross-over study, with breakfast (36.6g fat) |

CV for iAUC EPA: Plasma EPA 2461±279 (SEM), 882 SD, CV= 36% DHA: Plasma DHA 1021±170 (SEM), 538 SD, CV= 53% (iAUC ug/ml) |

No adverse effects were reported. | Smieta et al. 2025 (28) |

| Wax ester | |||||

| Wax ester (Calanus finmarchicus oil) |

4g oil containing 260mg EPA and 156 mg DHA, n= 18(9F, 9M) from USA. | A 72-h study, breakfast with 23g fat |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA+DHA 931±92 (SEM) (391 SD), CV= 42%. (iAUC ug x h/mL) |

No significant changes in GI symptoms over study period | Cook et al. 2016 (27) |

| EE with enhanced emulsification properties | |||||

| Self-emulsifying drug delivery system, Aquacelle ethyl esters | 680mg EPA+DHA Aquacelle EE n=30 (18F, 12M), healthy subjects from Australia. | A 24-hr study, with breakfast (2g fat) |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA+DHA 460.3±69.8 (SEM) (381 SD), CV = 83% (units not supplied) |

Adverse events not mentioned | Bremmell et al. 2020 (24) |

| Ethyl esters of omega-3 with enhanced solubility | 580mg novel liquid microcrystalline nanoparticle ethyl esters of omega-3, n=12 (M) healthy adults from Republic of Korea. | A 72-h study, breakfast, 15-20% fat 20 min before single dose of capsules with 200mL water. |

CV for AUC Plasma EPA 929±285 (SD), CV= 31% Plasma DHA 541±287, CV= 53% (AUC ug/ml x h). |

No adverse events were reported. | Kang et al., 2023 (25 |

|

Ethyl esters with self microemulsifying delivery system (SMEDS) containing ethyl esters |

1680mg EPA+DHA, n=40 (20F/20M) healthy adults from Switzerland and the UK. | A 48-h study, no breakfast, capsules consumed with water, but low-fat lunch (<15g) and standard meals thereafter. |

CV for iAUC Plasma EPA+DHA 358±141 (SD), CV= 39% (iAUC ug x h/mL/g). |

No adverse events were reported |

Qin et al., 2017 (26 |

| TAG either enteric coated or as microencapsulated emulsified form (LipoMicel, LMF) | Single meal, cross-over study. The standard and enteric-coated capsules contained 600mg omega-3 (400mg EPA + 200mg DHA); the microencapsulated form contained 374mg omega-3 (200mg EPA; 133 mg DHA; 41 mg DPA)., n=12 healthy adults (gender not specified) from Canada. | A 24-h study with breakfast (bagel, cream cheese, jam); lunch and dinner provided (no details) | CV for iAUC Blood total LC omega-3 Standard capsule 1498.9±443 (SEM), 1534 SD, CV=102% Enteric-coated capsule 2057.2±813.7 (SEM), 2819 SD, CV= 137% Microencapsulated capsule 16150±5454 (SEM), 18892 SD, CV= 117%. (iAUC ng/mL x h) |

No side effects were reported during the study. | Ibi et al. 2024 (29) |

| Whole Foods | |||||

| Whole food (herring) rich in omega-3 TAG | Single meal, cross-over study. The meals contained 3.2g omega-3 (baked herring) and 2.7g omega-3, (pickled herring). n=17 (M) overweight subjects from Sweden. | A 7-h study, meal of baked or pickled herring (29g fat, EPA+DHA 22% in baked herring and 18% in pickled herring). |

Baked herring -CV for iAUC Plasma EPA 108.3± 14.5 (SEM) (59.8 SD), CV= 56% Plasma DHA 120.0± 20.0 (SEM) (82.5 SD), CV= 68% Pickled herring – CV for iAUC Plasma EPA 93.9±10.8 (SEM) (44.5 SD), CV= 48% Plasma DHA 101.1±13.3 (SEM) (54.8 SD), CV= 54% (iAUC mg/L x h). |

Did not report side effects. | Svelander et al., 2015 (30) |

| Butter or sunflower oil supplemented with fish oil TAG | Single meal, cross-over study. The meals contain 1.9g omega-3 plus either 38g butter or 32g sunflower oil. n=26 (18F, 8M) from Australia. | A 6-h study, meal of mashed potato plus butter or sunflower oil plus omega-3 (1.8g EPA+DHA). |

Butter + omega-3 - CV for iAUC Plasma total omega-3 161.55±34.2 (SD), CV= 21% Sunflower oil + omega-3 - CV for iAUC Plasma total omega-3 164.89±42.02 (SD), CV= 26% (no units provided) |

Did not report adverse events. | Dias et al. 2015 (31) |

| Standard meal or standard meal enriched with fish oil | Single meal, cross-over study. The standard meal contained 0.4g EPA+DHA, and enriched meal contained 2.3g EPA+DHA (1.2g EPA, 1.1g DHA), n=20 (10F, 10M) from UK. | A 6-h study, meals were a liquid emulsion together with toast and jam/marmalade (55-56g fat). |

Standard meal CV for iAUC Plasma TG EPA 0.5±0.1 (SEM), 0.45 SD, CV= 89% Plasma TG DHA -0.5±0.2 (SEM), 0.9 SD, CV= 180% Enriched meal CV for iAUC Plasma TG EPA 3.2±0.4 (SEM), 1.79 SD, CV= 56% Plasma TG DHA 1.3±0.4 (SEM), 1.79 SD, CV= 138% (units not mentioned) |

Did not report adverse events. |

Burdge et al. 2007 (32) |

| Soup or rice crackers with encapsulated algal DHA (HighDHA) or capsules of DHA (HighDHA) | Single breakfast, cross-over study. Each treatment contained 400mg DHA and 14-15mg EPA, n=27 (M) from Australia and Singapore. | A 24-h cross-over study, all treatments included standard breakfast (7.3g fat) and low-fat snacks, lunch and dinner. |

CV for iAUC Soup: Plasma DHA 8069±5500(SD), CV= 68% Rice Crackers : Plasma DHA 7367±5599 (SD), CV= 76% DHA capsule: Plasma DHA 9864±8603 (SD), CV= 87%. (iAUC ug/ml x hr) |

No adverse events were reported during the study | Stonehouse et al. 2022 (14) |

References

- Enkhmaa B, Ozturk Z, Anuurad E, Berglund L. Postprandial lipoproteins and cardiovascular disease risk in diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2010 Feb;10(1):61-9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0088-4. PMID: 20425069; PMCID: PMC2821507.

- Bansal S, Buring JE, Rifai N, Mora S, Sacks FM, Ridker PM. Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. JAMA. 2007 Jul 18;298(3):309-16. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.309. PMID: 17635891.

- Kolovou GD, Mikhailidis DP, Kovar J, Lairon D, Nordestgaard BG, Ooi TC, Perez-Martinez P, Bilianou H, Anagnostopoulou K, Panotopoulos G. Assessment and clinical relevance of non-fasting and postprandial triglycerides: an expert panel statement. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2011 May;9(3):258-70. doi: 10.2174/157016111795495549. PMID: 21314632.

- Newman JW, Krishnan S, Borkowski K, Adams SH, Stephensen CB, Keim NL. Assessing Insulin Sensitivity and Postprandial Triglyceridemic Response Phenotypes With a Mixed Macronutrient Tolerance Test. Front Nutr. 2022 May 11;9:877696. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.877696. PMID: 35634390; PMCID: PMC9131925.

- Berry SE, Valdes AM, Drew DA, Asnicar F, Mazidi M, Wolf J, Capdevila J, Hadjigeorgiou G, Davies R, Al Khatib H, Bonnett C, Ganesh S, Bakker E, Hart D, Mangino M, Merino J, Linenberg I, Wyatt P, Ordovas JM, Gardner CD, Delahanty LM, Chan AT, Segata N, Franks PW, Spector TD. Human postprandial responses to food and potential for precision nutrition. Nat Med. 2020 Jun;26(6):964-973. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0934-0. Epub 2020 Jun 11. Erratum in: Nat Med. 2020 Nov;26(11):1802. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1130-y. PMID: 32528151; PMCID: PMC8265154.

- de Groot RHM, Emmett R, Meyer BJ. Non-dietary factors associated with n-3 long-chain PUFA levels in humans - a systematic literature review. Br J Nutr. 2019 Apr;121(7):793-808. doi: 10.1017/S0007114519000138. Epub 2019 Jan 28. PMID: 30688181; PMCID: PMC6521789.

- Alijani S, Hahn A, Harris WS, Schuchardt JP. Bioavailability of EPA and DHA in humans - A comprehensive review. Prog Lipid Res. 2024 Dec 28:101318. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2024.101318. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39736417.

- Sparkes C, Sinclair AJ, Gibson RA, Else PL, Meyer BJ. High Variability in Erythrocyte, Plasma and Whole Blood EPA and DHA Levels in Response to Supplementation. Nutrients. 2020 Apr 8;12(4):1017. doi: 10.3390/nu12041017. PMID: 32276315; PMCID: PMC7231102.

- Von Schacky C. Omega-3 fatty acids vs. cardiac disease--the contribution of the omega-3 index. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2010 Feb 25;56(1):93-101. PMID: 20196973.

- Köhler A, Bittner D, Löw A, von Schacky C. Effects of a convenience drink fortified with n-3 fatty acids on the n-3 index. Br J Nutr. 2010 Sep;104(5):729-36. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510001054. Epub 2010 Apr 27. PMID: 20420756.

- Ly R, MacIntyre BC, Philips SM, McGlory C, Mutch DM, Britz-McKibbin P. Lipidomic studies reveal two specific circulating phosphatidylcholines as surrogate biomarkers of the omega-3 index. J Lipid Res. 2023 Nov;64(11):100445. doi: 10.1016/j.jlr.2023.100445. Epub 2023 Sep 18. PMID: 37730162; PMCID: PMC10622695.

- Köhler A, Sarkkinen E, Tapola N, Niskanen T, Bruheim I. Bioavailability of fatty acids from krill oil, krill meal and fish oil in healthy subjects--a randomized, single-dose, cross-over trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2015 Mar 15;14:19. doi: 10.1186/s12944-015-0015-4. PMID: 25884846; PMCID: PMC4374210.

- Flock MR, Skulas-Ray AC, Harris WS, Etherton TD, Fleming JA, Kris-Etherton PM. Determinants of erythrocyte omega-3 fatty acid content in response to fish oil supplementation: a dose-response randomized controlled trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013 Nov 19;2(6):e000513. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000513. PMID: 24252845; PMCID: PMC3886744.

- Stonehouse W, Klingner B, Tso R, Teo PS, Terefe NS, Forde CG. Bioequivalence of long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from foods enriched with a novel vegetable-based omega-3 delivery system compared to gel capsules: a randomized controlled cross-over acute trial. Eur J Nutr. 2022 Jun;61(4):2129-2141. doi: 10.1007/s00394-021-02795-7. Epub 2022 Jan 18. PMID: 35041046; PMCID: PMC9106597.

- Schuchardt JP, Schneider I, Meyer H, Neubronner J, von Schacky C, Hahn A. Incorporation of EPA and DHA into plasma phospholipids in response to different omega-3 fatty acid formulations--a comparative bioavailability study of fish oil vs. krill oil. Lipids Health Dis. 2011 Aug 22;10:145. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-145. PMID: 21854650; PMCID: PMC3168413.

- West AL, Miles EA, Lillycrop KA, Han L, Sayanova O, Napier JA, Calder PC, Burdge GC. Postprandial incorporation of EPA and DHA from transgenic Camelina sativa oil into blood lipids is equivalent to that from fish oil in healthy humans. Br J Nutr. 2019 Jun;121(11):1235-1246. doi: 10.1017/S0007114519000825. Epub 2019 Apr 12. PMID: 30975228; PMCID: PMC6658215.

- Wakil A, Mir M, Mellor DD, Mellor SF, Atkin SL. The bioavailability of eicosapentaenoic acid from reconstituted triglyceride fish oil is higher than that obtained from the triglyceride and monoglyceride forms. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19(4):499-505. PMID: 21147710.

- Guarneiri LL, Wilcox ML, Maki KC. Comparison of the effects of a phospholipid-enhanced fish oil versus krill oil product on plasma levels of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids after acute administration: A randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Nutrition. 2023 Oct;114:112090. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2023.112090. Epub 2023 May 29. PMID: 37413768.

- Kagan ML, West AL, Zante C, Calder PC. Acute appearance of fatty acids in human plasma--a comparative study between polar-lipid rich oil from the microalgae Nannochloropsis oculata and krill oil in healthy young males. Lipids Health Dis. 2013 Jul 15;12:102. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-12-102. PMID: 23855409; PMCID: PMC3718725.

- Offman E, Marenco T, Ferber S, Johnson J, Kling D, Curcio D, Davidson M. Steady-state bioavailability of prescription omega-3 on a low-fat diet is significantly improved with a free fatty acid formulation compared with an ethyl ester formulation: the ECLIPSE II study. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:563-73. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S50464. Epub 2013 Oct 1. PMID: 24124374; PMCID: PMC3794864.

- Cuenoud B, Rochat I, Gosoniu ML, Dupuis L, Berk E, Jaudszus A, Mainz JG, Hafen G, Beaumont M, Cruz-Hernandez C. Monoacylglycerol Form of Omega-3s Improves Its Bioavailability in Humans Compared to Other Forms. Nutrients. 2020 Apr 7;12(4):1014. doi: 10.3390/nu12041014. PMID: 32272659; PMCID: PMC7230359.

- Jing S, Zhang Z, Chen X, Miao R, Nilsson C, Lin Y. Pharmacokinetics of Single and Multiple Doses of Omega-3 Carboxylic Acids in Healthy Chinese Subjects: A Phase I, Open-Label Study. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2020 Nov;9(8):985-994. doi: 10.1002/cpdd.800. Epub 2020 Jun 21. PMID: 32567203.

- Chevalier L, Plourde M. Comparison of pharmacokinetics of omega-3 fatty acid supplements in monoacylglycerol or ethyl ester in humans: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021 Apr;75(4):680-688. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-00767-4. Epub 2020 Oct 3. PMID: 33011737; PMCID: PMC8035073.

- Bremmell KE, Briskey D, Meola TR, Mallard A, Prestidge CA, Rao A. A self-emulsifying Omega-3 ethyl ester formulation (AquaCelle) significantly improves eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid bioavailability in healthy adults. Eur J Nutr. 2020 Sep;59(6):2729-2737. doi: 10.1007/s00394-019-02118-x. Epub 2019 Oct 21. PMID: 31637467.

- Kang KM, Jeon SW, De A, Hong TS, Park YJ. A Randomized, Open-Label, Single-Dose, Crossover Study of the Comparative Bioavailability of EPA and DHA in a Novel Liquid Crystalline Nanoparticle-Based Formulation of ω-3 Acid Ethyl Ester Versus Omacor® Soft Capsule among Healthy Adults. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Dec 6;24(24):17201. doi: 10.3390/ijms242417201. PMID: 38139029; PMCID: PMC10743492.

- Qin Y, Nyheim H, Haram EM, Moritz JM, Hustvedt SO. A novel self-micro-emulsifying delivery system (SMEDS) formulation significantly improves the fasting absorption of EPA and DHA from a single dose of an omega-3 ethyl ester concentrate. Lipids Health Dis. 2017 Oct 16;16(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s12944-017-0589-0. PMID: 29037249; PMCID: PMC5644165.

- Cook CM, Larsen TS, Derrig LD, Kelly KM, Tande KS. Wax Ester Rich Oil From The Marine Crustacean, Calanus finmarchicus, is a Bioavailable Source of EPA and DHA for Human Consumption. Lipids. 2016 Oct;51(10):1137-1144. doi: 10.1007/s11745-016-4189-y. Epub 2016 Sep 7. PMID: 27604086.

- Schmieta HM, Greupner T, Schneider I, Wrobel S, Christa V, Kutzner L, Hahn A, Harris WS, Schebb NH, Schuchardt JP. Plasma levels of EPA and DHA after ingestion of a single dose of EPA and DHA ethyl esters. Lipids. 2025 Jan;60(1):15-23. doi: 10.1002/lipd.12417. Epub 2024 Sep 19. PMID: 39299684; PMCID: PMC11717491.

- Ibi A, Chang C, Kuo YC, Zhang Y, Du M, Roh YS, Gahler R, Hardy M, Solnier J. Evaluation of the Metabolite Profile of Fish Oil Omega-3 Fatty Acids (n-3 FAs) in Micellar and Enteric-Coated Forms-A Randomized, Cross-Over Human Study. Metabolites. 2024 May 7;14(5):265. doi: 10.3390/metabo14050265. PMID: 38786742; PMCID: PMC11123365.

- Svelander C, Gabrielsson BG, Almgren A, Gottfries J, Olsson J, Undeland I, Sandberg AS. Postprandial lipid and insulin responses among healthy, overweight men to mixed meals served with baked herring, pickled herring or baked, minced beef. Eur J Nutr. 2015 Sep;54(6):945-58. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0771-3. Epub 2014 Nov 22. PMID: 25416681.

- Dias CB, Phang M, Wood LG, Garg ML. Postprandial lipid responses do not differ following consumption of butter or vegetable oil when consumed with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lipids. 2015 Apr;50(4):339-47. doi: 10.1007/s11745-015-4003-2. Epub 2015 Mar 10. PMID: 25753895.

- Burdge GC, Sala-Vila A, West AL, Robson HJ, Le Fevre LW, Powell J, Calder PC. The effect of altering the 20:5n-3 and 22:6n-3 content of a meal on the postprandial incorporation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids into plasma triacylglycerol and non-esterified fatty acids in humans. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2007 Jul;77(1):59-65. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.06.003. Epub 2007 Aug 10. PMID: 17693069.

- Shi Y, Burn P. Lipid metabolic enzymes: emerging drug targets for the treatment of obesity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004 Aug;3(8):695-710. doi: 10.1038/nrd1469. PMID: 15286736.

- Wang TY, Liu M, Portincasa P, Wang DQ. New insights into the molecular mechanism of intestinal fatty acid absorption. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013 Nov;43(11):1203-23. doi: 10.1111/eci.12161. Epub 2013 Sep 18. PMID: 24102389; PMCID: PMC3996833.

- O’Connor GT, Malenka DJ, Olmstead EM, Johnson PS, Hennekens CH. A meta-analysis of randomized trials of fish oil in prevention of restenosis following coronary angioplasty. Am J Prev Med. 1992 May-Jun;8(3):186-92. PMID: 1385968.

- Belluzzi A, Brignola C, Campieri M, Camporesi EP, Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Belloli C, De Simone G, Boschi S, Miglioli M, et al. Effects of new fish oil derivative on fatty acid phospholipid-membrane pattern in a group of Crohn’s disease patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1994 Dec;39(12):2589-94. doi: 10.1007/BF02087694. PMID: 7995183.

- Costantini L, Molinari R, Farinon B, Merendino N. Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on the Gut Microbiota. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Dec 7;18(12):2645. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122645. PMID: 29215589; PMCID: PMC5751248.

- Rundblad A, Sandoval V, Holven KB, Ordovás JM, Ulven SM. Omega-3 fatty acids and individual variability in plasma triglyceride response: A mini-review. Redox Biol. 2023 Jul;63:102730. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102730. Epub 2023 May 3. PMID: 37150150; PMCID: PMC10184047.

- Ma Y, Fu Y, Tian Y, Gou W, Miao Z, Yang M, Ordovás JM, Zheng JS. Individual Postprandial Glycemic Responses to Diet in n-of-1 Trials: Westlake N-of-1 Trials for Macronutrient Intake (WE-MACNUTR). J Nutr. 2021 Oct 1;151(10):3158-3167. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab227. PMID: 34255080; PMCID: PMC8485912.

|

Omega-3 lipid supplement |

Number of treatments1 |

Variability in AUC (iAUC) expressed as coefficient of variation (CV)2 |

| TAG | 6 | 38-102%, with 7/10 data points3 >50% |

| PL or polar lipid | 6 | 28-76%, with 5/9 data points >50% |

| FFA | 3 | 34-53%, with 3/5 data points >50% |

| MAG | 3 | 19-93%, with 2/4 data points >50% |

| Ethyl esters (EE) | 9 | 32-154%, with 9/12 data points >50% |

| Wax esters | 1 | 0/1 data points >50% |

| EE with enhanced emulsification |

4 | 31-137%, with 4/6 data points >50% |

| Whole foods | 4 | 21-138%, with 7/10 data points > 50% |

| Total | 36 | 19-154%, with 37/57 data points >50% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).