Submitted:

27 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

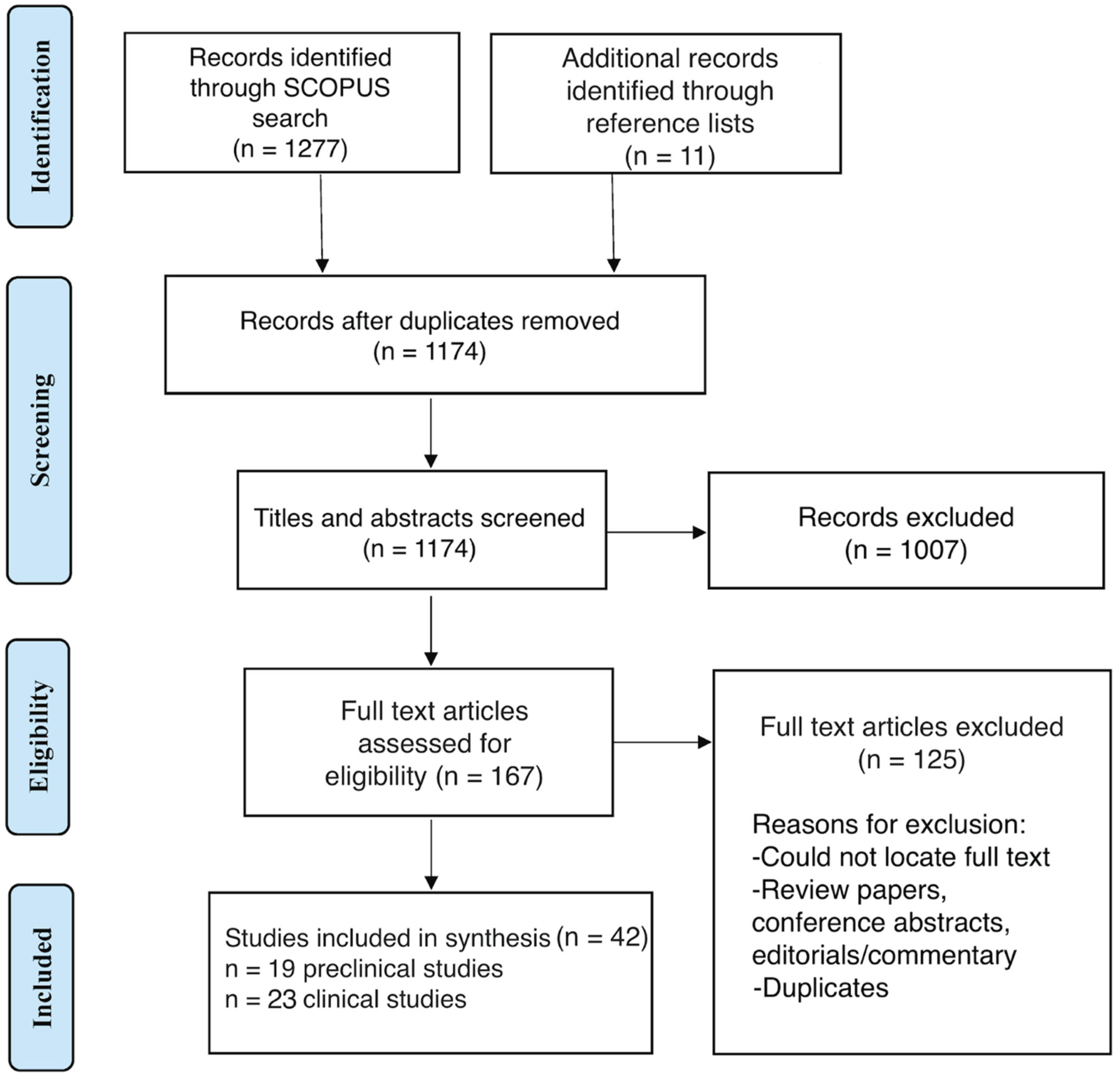

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Screening Process

3. Results

3.1. Preclinical Studies

3.1.1. Lithium Augmentation of the Rapid Antidepressant Effect of Ketamine

3.1.2. Studies Related to Ketamine as a Preclinical Model of Mania/Psychosis

3.2. Clinical Studies

3.2.1. Rapid Antidepressant Efficacy in Mood Disorders (Clinical Outcomes)

3.2.2. Symptom Subtypes and Clinical Predictors of Response

3.2.3. Adjunctive Treatments to Sustain Ketamine’s Effects

3.2.4. Neuroimaging and Neurophysiological Mechanisms

3.2.5. Peripheral Biomarkers and Molecular Pathways

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yatham L, Kennedy S, Parikh S, Schaffer A, Bond D, Frey B, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2018;20, 97–170. [CrossRef]

- Grof P. Sixty Years of Lithium Responders. Neuropsychobiology. 2010 May 7;62, 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Garnham J, Munro A, Slaney C, MacDougall M, Passmore M, Duffy A, et al. Prophylactic treatment response in bipolar disorder: Results of a naturalistic observation study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;104(1–3):185–90. [CrossRef]

- Nunes A, Ardau R, Berghöfer A, Bocchetta A, Chillotti C, Deiana V, et al. Prediction of lithium response using clinical data. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2020;141, 131–41. [CrossRef]

- Scott K, Khayachi A, Alda M, Nunes A. Prediction of Treatment Outcome in Bipolar Disorder: When Can We Expect Clinical Relevance? Biological Psychiatry. 2025 Aug 15;98, 285–92. [CrossRef]

- Nunes A, Stone W, Ardau R, Berghöfer A, Bocchetta A, Chillotti C, et al. Exemplar scoring identifies genetically separable phenotypes of lithium responsive bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2021 June;11, 36. [CrossRef]

- Gershon S, Chengappa K, Malhi G. Lithium specificity in bipolar illness: A classic agent for the classic disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2009;11(SUPPL. 2):34–44. [CrossRef]

- Hui TP, Kandola A, Shen L, Lewis G, Osborn DPJ, Geddes JR, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019 Aug;140, 94–115. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y, Maihofer AX, Stapp E, Ritchey M, Alliey-Rodriguez N, Anand A, et al. Clinical predictors of non-response to lithium treatment in the Pharmacogenomics of Bipolar Disorder (PGBD) study. Bipolar Disorders. 2021;23, 821–31. [CrossRef]

- Calkin CV, Ruzickova M, Uher R, Hajek T, Slaney CM, Garnham JS, et al. Insulin resistance and outcome in bipolardisorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2015 Jan;206, 52–7.

- Fancy F, Haikazian S, Johnson DE, Chen-Li DCJ, Levinta A, Husain MI, et al. Ketamine for bipolar depression: an updated systematic review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2023 Sept 26;13:20451253231202723. [CrossRef]

- Kraus C, Rabl U, Vanicek T, Carlberg L, Popovic A, Spies M, et al. Administration of ketamine for unipolar and bipolar depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2017 Jan 2;21, 2–12. [CrossRef]

- Lam RW. Onset, time course and trajectories of improvement with antidepressants. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012 Jan 1;22:S492–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Zhou Y, Zheng W, Liu W, Zhan Y, Li H, et al. Association between depression subtypes and response to repeated-dose intravenous ketamine. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2019;140, 446–57. [CrossRef]

- Ionescu DF, Luckenbaugh DA, Niciu MJ, Richards EM, Zarate CA. A single infusion of ketamine improves depression scores in patients with anxious bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2015 June;17, 438–43. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre RS, Lipsitz O, Rodrigues NB, Lee Y, Cha DS, Vinberg M, et al. The effectiveness of ketamine on anxiety, irritability, and agitation: Implications for treating mixed features in adults with major depressive or bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2020;22, 831–40. [CrossRef]

- Rong C, Park C, Rosenblat JD, Subramaniapillai M, Zuckerman H, Fus D, et al. Predictors of Response to Ketamine in Treatment Resistant Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Apr 17;15, 771. [CrossRef]

- Hui T, Kandola A, Shen L, Lewis G, Osborn D, Geddes J, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2019;140, 94–115. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre RS, Lipsitz O, Rodrigues NB, Lee Y, Cha DS, Vinberg M, et al. The effectiveness of ketamine on anxiety, irritability, and agitation: Implications for treating mixed features in adults with major depressive or bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2020;22, 831–40. [CrossRef]

- Chiu CT, Scheuing L, Liu G, Liao HM, Linares GR, Lin D, et al. The Mood Stabilizer Lithium Potentiates the Antidepressant-Like Effects and Ameliorates Oxidative Stress Induced by Acute Ketamine in a Mouse Model of Stress. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015 Apr 1;18, pyu102. [CrossRef]

- Liu RJ, Fuchikami M, Dwyer JM, Lepack AE, Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. GSK-3 Inhibition Potentiates the Synaptogenic and Antidepressant-Like Effects of Subthreshold Doses of Ketamine. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013 Oct;38, 2268–77. [CrossRef]

- do Vale EM, Xavier CC, Nogueira BG, Campos BC, de Aquino PEA, da Costa RO, et al. Antinociceptive and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Ketamine and the Relationship to Its Antidepressant Action and GSK3 Inhibition. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2016;119, 562–73. [CrossRef]

- Price JB, Yates CG, Morath BA, Van De Wakker SK, Yates NJ, Butters K, et al. Lithium augmentation of ketamine increases insulin signaling and antidepressant-like active stress coping in a rodent model of treatment-resistant depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2021 Nov 25;11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Maltbie E, Gopinath K, Urushino N, Kempf D, Howell L. Ketamine-induced brain activation in awake female nonhuman primates: a translational functional imaging model. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016 Mar;233, 961–72. [CrossRef]

- Stepan J, Hladky F, Uribe A, Holsboer F, Schmidt MV, Eder M. High-Speed imaging reveals opposing effects of chronic stress and antidepressants on neuronal activity propagation through the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit. Front Neural Circuits. 2015 Nov 6;9:70. [CrossRef]

- Debom G, Gazal M, Soares MSP, do Couto CAT, Mattos B, Lencina C, et al. Preventive effects of blueberry extract on behavioral and biochemical dysfunctions in rats submitted to a model of manic behavior induced by ketamine. Brain Research Bulletin. 2016 Oct 1;127:260–9. [CrossRef]

- Spohr L, Soares MSP, Oliveira PS, da Silveira de Mattos B, Bona NP, Pedra NS, et al. Combined actions of blueberry extract and lithium on neurochemical changes observed in an experimental model of mania: exploiting possible synergistic effects. Metab Brain Dis. 2019 Apr;34, 605–19. [CrossRef]

- Chaves VC, Soares MSP, Spohr L, Teixeira F, Vieira A, Constantino LS, et al. Blackberry extract improves behavioral and neurochemical dysfunctions in a ketamine-induced rat model of mania. Neuroscience Letters. 2020 Jan 1;714:134566. [CrossRef]

- Gazal M, Valente MR, Acosta BA, Kaufmann FN, Braganhol E, Lencina CL, et al. Neuroprotective and antioxidant effects of curcumin in a ketamine-induced model of mania in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2014 Feb 5;724:132–9. [CrossRef]

- Gazal M, Kaufmann FN, Acosta BA, Oliveira PS, Valente MR, Ortmann CF, et al. Preventive Effect of Cecropia pachystachya Against Ketamine-Induced Manic Behavior and Oxidative Stress in Rats. Neurochem Res. 2015 July 1;40, 1421–30. [CrossRef]

- Recart VM, Spohr L, Soares MSP, de Mattos B da S, Bona NP, Pedra NS, et al. Gallic acid protects cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and striatum against oxidative damage and cholinergic dysfunction in an experimental model of manic-like behavior: Comparison with lithium effects. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2021;81, 167–78. [CrossRef]

- Arslan FC, Tiryaki A, Yıldırım M, Özkorumak E, Alver A, Altun İK, et al. The effects of edaravone in ketamine-induced model of mania in rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars). 2016;76, 192–8. [CrossRef]

- Gao TH, Ni RJ, Liu S, Tian Y, Wei J, Zhao L, et al. Chronic lithium exposure attenuates ketamine-induced mania-like behavior and c-Fos expression in the forebrain of mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2021 Mar 1;202:173108. [CrossRef]

- Ni RJ, Gao TH, Wang YY, Tian Y, Wei JX, Zhao LS, et al. Chronic lithium treatment ameliorates ketamine-induced mania-like behavior via the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. Zoological Research. 2022;43, 989–1004. [CrossRef]

- Brody SA, Geyer MA, Large CH. Lamotrigine prevents ketamine but not amphetamine-induced deficits in prepulse inhibition in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2003 Sept 1;169, 240–6. [CrossRef]

- Rame M, Caudal D, Schenker E, Svenningsson P, Spedding M, Jay TM, et al. Clozapine counteracts a ketamine-induced depression of hippocampal-prefrontal neuroplasticity and alters signaling pathway phosphorylation. PLOS ONE. 2017 May 4;12, e0177036. [CrossRef]

- Bowman C, Richter U, Jones CR, Agerskov C, Herrik KF. Activity-State Dependent Reversal of Ketamine-Induced Resting State EEG Effects by Clozapine and Naltrexone in the Freely Moving Rat. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Jan 27;13:737295. [CrossRef]

- Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, Sudheimer K, Pannu J, Pankow H, et al. Attenuation of Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine by Opioid Receptor Antagonism. AJP. 2018 Dec;175, 1205–15. [CrossRef]

- Diazgranados N, Ibrahim L, Brutsche NE, Newberg A, Kronstein P, Khalife S, et al. A Randomized Add-on Trial of an N-methyl-d-aspartate Antagonist in Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Aug;67, 793–802. [CrossRef]

- Zarate CA, Brutsche NE, Ibrahim L, Franco-Chaves J, Diazgranados N, Cravchik A, et al. Replication of Ketamine’s Antidepressant Efficacy in Bipolar Depression: A Randomized Controlled Add-On Trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2012 June 1;71, 939–46. [CrossRef]

- Xu AJ, Niciu MJ, Lundin NB, Luckenbaugh DA, Ionescu DF, Richards EM, et al. Lithium and Valproate Levels Do Not Correlate with Ketamine’s Antidepressant Efficacy in Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression. Neural Plasticity. 2015 June 7;2015:e858251. [CrossRef]

- Rybakowski JK, Permoda-Osip A, Bartkowska-Sniatkowska A. Ketamine augmentation rapidly improves depression scores in inpatients with treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2017 June;21, 99–103. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien B, Lijffijt M, Lee J, Kim YS, Wells A, Murphy N, et al. Distinct trajectories of antidepressant response to intravenous ketamine. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021 May 1;286:320–9. [CrossRef]

- Serretti A, Lattuada E, Franchini L, Smeraldi E. Melancholic features and response to lithium prophylaxis in mood disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2000;11, 73–9. [CrossRef]

- Ionescu DF, Luckenbaugh DA, Niciu MJ, Richards EM, Zarate Jr CA. A single infusion of ketamine improves depression scores in patients with anxious bipolar depression. Bipolar Disorders. 2015;17, 438–43.

- Peters EM, Halpape K, Cheveldae I, Jacobson P, Wanson A. Predictors of response to intranasal ketamine in patients hospitalized for treatment-resistant depression. Personalized Medicine in Psychiatry. 2024 Mar 1;43–44:100119. [CrossRef]

- Etain B, Lajnef M, Brichant-Petitjean C, Geoffroy PA, Henry C, Gard S, et al. Childhood trauma and mixed episodes are associated with poor response to lithium in bipolar disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017 Apr;135, 319–27. [CrossRef]

- Cascino G, D’Agostino G, Monteleone AM, Marciello F, Caivano V, Monteleone P, et al. Childhood maltreatment and clinical response to mood stabilizers in patients with bipolar disorder. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 2021;36, e2783. [CrossRef]

- Pennybaker SJ, Niciu MJ, Luckenbaugh DA, Zarate CA. Symptomatology and Predictors of Antidepressant Efficacy in Extended Responders to a Single Ketamine Infusion. J Affect Disord. 2017 Jan 15;208:560–6. [CrossRef]

- Keith KM, Geller J, Froehlich A, Arfken C, Oxley M, Mischel N. Vital Sign Changes During Intravenous Ketamine Infusions for Depression: An Exploratory Study of Prognostic Indications. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022 May;42, 254–9.

- Lundin NB, Niciu MJ, Luckenbaugh DA, Ionescu DF, Richards EM, Voort JLV, et al. Baseline Vitamin B12 and Folate Levels Do Not Predict Improvement in Depression After a Single Infusion of Ketamine. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2014 July;47, 141–4. [CrossRef]

- Permoda-Osip A, Skibińska M, Bartkowska-Sniatkowska A, Kliwicki S, Chłopocka-Woźniak M, Rybakowski JK. [Factors connected with efficacy of single ketamine infusion in bipolar depression]. Psychiatr Pol. 2014 Feb;48, 35–47. [CrossRef]

- Costi S, Soleimani L, Glasgow A, Brallier J, Spivack J, Schwartz J, et al. Lithium continuation therapy following ketamine in patients with treatment resistant unipolar depression: a randomized controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019 Sept;44, 1812–9. [CrossRef]

- Amiaz R, Saporta R, Noy A, Berkenstadt H, Weiser M. Can Quetiapine Prolong the Antidepressant Effect of Ketamine?: A 5-Year Follow-up Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021 Nov;41, 673–5.

- Nugent AC, Diazgranados N, Carlson PJ, Ibrahim L, Luckenbaugh DA, Brutsche N, et al. Neural correlates of rapid antidepressant response to ketamine in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2014;16, 119–28. [CrossRef]

- Chen MH, Chang WC, Lin WC, Tu PC, Li CT, Bai YM, et al. Functional Dysconnectivity of Frontal Cortex to Striatum Predicts Ketamine Infusion Response in Treatment-Resistant Depression. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020 Dec 1;23, 791–8. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Wang C, Lan X, Li W, Zhang F, Hu Z, et al. Functional connectivity of the amygdala subregions and the antidepressant effects of repeated ketamine infusions in major depressive disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2024 Apr 4;67, e33. [CrossRef]

- Cao Z, Lin CT, Ding W, Chen MH, Li CT, Su TP. Identifying Ketamine Responses in Treatment-Resistant Depression Using a Wearable Forehead EEG. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2019 June;66, 1668–79. [CrossRef]

- Berner K, Oz N, Kaya A, Acharjee A, Berner J. mTORC1 activation in presumed classical monocytes: observed correlation with human size variation and neuropsychiatric disease. Aging. 2024;16, 11134–50. [CrossRef]

- McGrory CL, Ryan KM, Gallagher B, McLoughlin DM. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020m 273:380–3.

- Guo S, Arai K, Stins MF, Chuang DM, Lo EH. Lithium Upregulates Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Brain Endothelial Cells and Astrocytes. Stroke. 2009 Feb;40, 652–5. [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor A, Ramamoorthy A, Silva dos Santos M, Lorenzo MP, Laje G, Zarate Jr C, et al. A pilot study of plasma metabolomic patterns from patients treated with ketamine for bipolar depression: evidence for a response-related difference in mitochondrial networks. British Journal of Pharmacology 2014;171, 2230–42.

- Słupski J, Cubała WJ, Górska N, Słupska A, Gałuszko-Węgielnik M. Copper Concentrations in Ketamine Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Brain Sciences. 2020 Dec;10(12):971. [CrossRef]

- Duman RS, Li N, Liu RJ, Duric V, Aghajanian G. Signaling Pathways Underlying the Rapid Antidepressant Actions of Ketamine. Neuropharmacology. 2012 Jan;62(1):35–41. [CrossRef]

- Zanos P, Gould TD. Intracellular signaling pathways involved in (S)- and (R)-ketamine antidepressant actions. Biol Psychiatry. 2018 Jan 1;83(1):2–4. [CrossRef]

- Quiroz JA, Gould TD, Manji HK. Molecular effects of lithium. Mol Interv. 2004 Oct;4(5):259–72.

- Wilkinson ST, Katz RB, Toprak M, Webler R, Ostroff RB, Sanacora G. Acute and Longer-Term Outcomes Using Ketamine as a Clinical Treatment at the Yale Psychiatric Hospital. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018 July 24;79(4):10099.

- Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, Geddes JR. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013 June 27;346:f3646. [CrossRef]

- Grof P, Duffy A, Cavazzoni P, Grof E, Garnham J, MacDougall M, et al. Is response to prophylactic lithium a familial trait? J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 Oct;63(10):942–7. [CrossRef]

- Manchia M, Adli M, Akula N, Ardau R, Aubry JM, Backlund L, et al. Assessment of Response to Lithium Maintenance Treatment in Bipolar Disorder: A Consortium on Lithium Genetics (ConLiGen) Report. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65636. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre RS, Rosenblat JD, Nemeroff CB, Sanacora G, Murrough JW, Berk M, et al. Synthesizing the Evidence for Ketamine and Esketamine in Treatment-Resistant Depression: An International Expert Opinion on the Available Evidence and Implementation. Am J Psychiatry. 2021 May 1;178(5):383–99. [CrossRef]

- Rybakowski JK, Suwalska A. Excellent lithium responders have normal cognitive functions and plasma BDNF levels. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010 June 1;13(5):617–22. [CrossRef]

- Khayachi A, Ase A, Liao C, Kamesh A, Kuhlmann N, Schorova L, et al. Chronic lithium treatment alters the excitatory/ inhibitory balance of synaptic networks and reduces mGluR5–PKC signalling in mouse cortical neurons. JPN. 2021 May 1;46(3):E402–14. [CrossRef]

- Khayachi A, Abuzgaya M, Liu Y, Jiao C, Dejgaard K, Schorova L, et al. Akt and AMPK activators rescue hyperexcitability in neurons from patients with bipolar disorder. EBioMedicine. 2024 June;104:105161. [CrossRef]

- Stern S, Santos R, Marchetto M, Mendes A, Rouleau G, Biesmans S, et al. Neurons derived from patients with bipolar disorder divide into intrinsically different sub-populations of neurons, predicting the patients’ responsiveness to lithium. Molecular Psychiatry. 2018;23(6):1453–65. [CrossRef]

- Stern S, Sarkar A, Galor D, Stern T, Mei A, Stern Y, et al. A Physiological Instability Displayed in Hippocampal Neurons Derived From Lithium-Nonresponsive Bipolar Disorder Patients. Biological Psychiatry. 2020 July;88(2):150–8. [CrossRef]

- Stern S, Sarkar A, Stern T, Mei A, Mendes APD, Stern Y, et al. Mechanisms Underlying the Hyperexcitability of CA3 and Dentate Gyrus Hippocampal Neurons Derived From Patients With Bipolar Disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2020 July;88(2):139–49. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).