Introduction

The integration of large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, into clinical informatics has opened promising avenues in medical documentation, decision support, and research. LLMs have shown capabilities in automating administrative tasks, summarizing patient information, and enhancing clinician workflows and patient communication [

1,

2]. However, their application in dermatology, particularly in parsing unstructured clinical narratives to extract treatment histories, remains underexplored.

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated skin disease affecting approximately 3% of the global population. Its management involves individualized, often complex regimens, including topical therapies, systemic medications, biologics, phototherapy, and procedural interventions [

2,

3]. Given the disease’s unpredictable course, risk of progression to psoriatic arthritis, and variability in treatment response, tracking longitudinal treatment history is both clinically essential and operationally challenging. While this information is often documented in electronic medical records (EMRs), it typically resides in free-text form, which lacks standardization and is challenging to analyze retrospectively [

3,

4].

Recent advances in natural language processing (NLP) have enabled AI-powered tools to enhance electronic medical records (EMR) abstraction, with studies showing improved disease identification when narrative text is analyzed alongside structured codes, outperforming code-only algorithms in diseases like psoriatic arthritis and inflammatory dermatoses [

3,

5]. In dermatology, tools like ChatGPT have demonstrated potential in patient education, clinical summarization, and simulation of board exam scenarios [

1,

6]. Specifically in psoriasis, ChatGPT-4 has been used to identify affected body areas and comorbidities from clinical narratives [

7], with some success in comparing treatment options and supporting patient engagement, although diagnostic limitations remain [

2,

5]. In rheumatology, NLP-based classification of psoriatic arthritis has outperformed rule-based models, further supporting the feasibility of LLMs in treatment-related tasks [

3].

Despite these advances, the capacity of LLMs, particularly ChatGPT, to extract and structure detailed treatment histories from unstructured EMRs in psoriasis remains underinvestigated. Clinical documentation often includes variable terminology, abbreviations, spelling inconsistencies, and linguistic ambiguity. Moreover, distinguishing between treatments for psoriasis and those for comorbidities adds further complexity [

8,

9]. Phrases involving negation or uncertainty (e.g., “the patient was not treated with methotrexate”) must also be interpreted correctly to avoid false positives [

10,

11].

LLMs like GPT-4 have shown promise in overcoming similar challenges in other domains. For example, they have demonstrated high recall in extracting findings from radiology reports (99.3%), supporting the feasibility of automating data extraction tasks[

12]. They have also been effective in de-identifying clinical notes and generating synthetic data, thereby improving administrative workflows and data quality [

9,

13]. In oncology, ChatGPT-4 has been used to identify cancer phenotypes from EHR text, further supporting its value in extracting clinical information from unstructured narratives[

14]. Moreover, ChatGPT-4 has achieved diagnostic accuracy levels comparable to physicians when identifying final diagnoses from differential lists (footnote 1).

These findings suggest a strong potential for LLMs to support automated extraction of structured treatment data from complex, unstructured text, which is a critical need in dermatology, where documentation practices are exceptionally heterogeneous.

In this exploratory study, we evaluate the general-purpose language model ChatGPT-4o’s ability to extract treatment information from unstructured EMRs of patients with psoriasis. By comparing its outputs to gold-standard annotations from expert dermatologists, we assess its accuracy and explore its potential utility in dermatology workflows. This work contributes to the growing body of literature supporting the use of LLMs in dermatology. It aims to inform scalable AI-assisted solutions for clinical documentation, retrospective cohort assembly, and decision support in chronic dermatoses.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 94 electronic medical records (EMRs) of patients diagnosed with psoriasis and treated at the Dermatology and Psoriasis Clinic at Sheba Medical Center. The EMRs were written in a hybrid of Hebrew and English and included patient anamnesis, physical examination findings, treatment history, and management plans. A board-certified dermatologist manually reviewed each record to annotate all treatments specifically administered for psoriasis. Treatments documented for other dermatologic conditions were ignored. Each patient case was transformed into a structured dataset entry, with binary indicator variables corresponding to 83 possible treatments. Each treatment was labeled TRUE if used for treating psoriasis and FALSE otherwise, resulting in a sparse matrix.

To evaluate automated extraction, we applied ChatGPT-4o, a general-purpose multimodal language model developed by OpenAI. A custom GPT agent was created on OpenAI’s platform (psoriasis-treatment-extractor), with the following exact instructions: 'The GPT will read a mix of Hebrew and English summaries provided by the user, extracting only the treatments related to psoriasis. If a treatment is mentioned, the GPT will identify whether the patient received it, note the patient’s response to the treatment, and specify the duration or number of treatment courses if mentioned. The GPT will avoid mentioning treatments for other diseases and focus solely on psoriasis-related information. Mention only treatments in the past and not treatments planned for the future.' The model was not provided with a predefined medication list and relied solely on the textual content of each EMR. Each note was entered individually in a new session, with the model instructed not to save any data for future training. The extracted treatments were then manually copied into a binary-coded table identical in structure to the expert-annotated dataset.

We then obtained parallel binary classifications—one from the human expert and one from ChatGPT-4o—for each of the 94 records and 83 treatments. To assess model performance, we calculated accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, specificity, Cohen’s Kappa, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).

Evaluation was conducted at multiple levels: (1) a global level, treating each treatment-patient combination as a separate binary instance (7,802 in total); (2) treatment-wise, where each treatment was evaluated as a separate classification task (limited to treatments with at least five positive cases); and (3) group-level, where treatments were clustered into pharmacologic categories (e.g., biologics, topical steroids) to increase statistical stability and interpretability.

Table 1 outlines the pharmacologic categories and their corresponding treatments used to group medications for the group-level analysis. Lastly, we computed per-record Cohen’s Kappa to assess agreement on a patient-level basis.

All analyses were conducted using R (version 4.4.1).

IRB approval status: Reviewed and approved by the Sheba Medical Center Ethics Committee, approval number 1083-24-SMC.

Results

Of the 94 psoriasis cases included in the study, 55 were female (58.5%) and 39 were male (41.5%). The age range of patients was 18.9 to 86.7 years. Clinical visit notes averaged 278 ± 154 words in length. The number of psoriasis treatments per patient varied from zero (in five cases) to twelve, with a median of three and a mean of 3.2. Some treatments, including Loratadine, Dexacort, and IV Experimental therapy, were rare—appearing only once—and were missed by the model. Conversely, ChatGPT-4o misidentified three treatments as psoriasis-related that were actually indicated for other conditions.

At the global level, ChatGPT-4o demonstrated strong overall performance across 7,802 binary instances (83 treatments × 94 records). It achieved a recall of 0.91 and a precision of 0.96, resulting in an F1-score of 0.94. Specificity and accuracy both reached 0.99, and Cohen’s Kappa was 0.93, indicating strong agreement with expert annotations beyond chance. The model’s AUC was 0.98, reflecting excellent discrimination between prescribed and non-prescribed treatments.

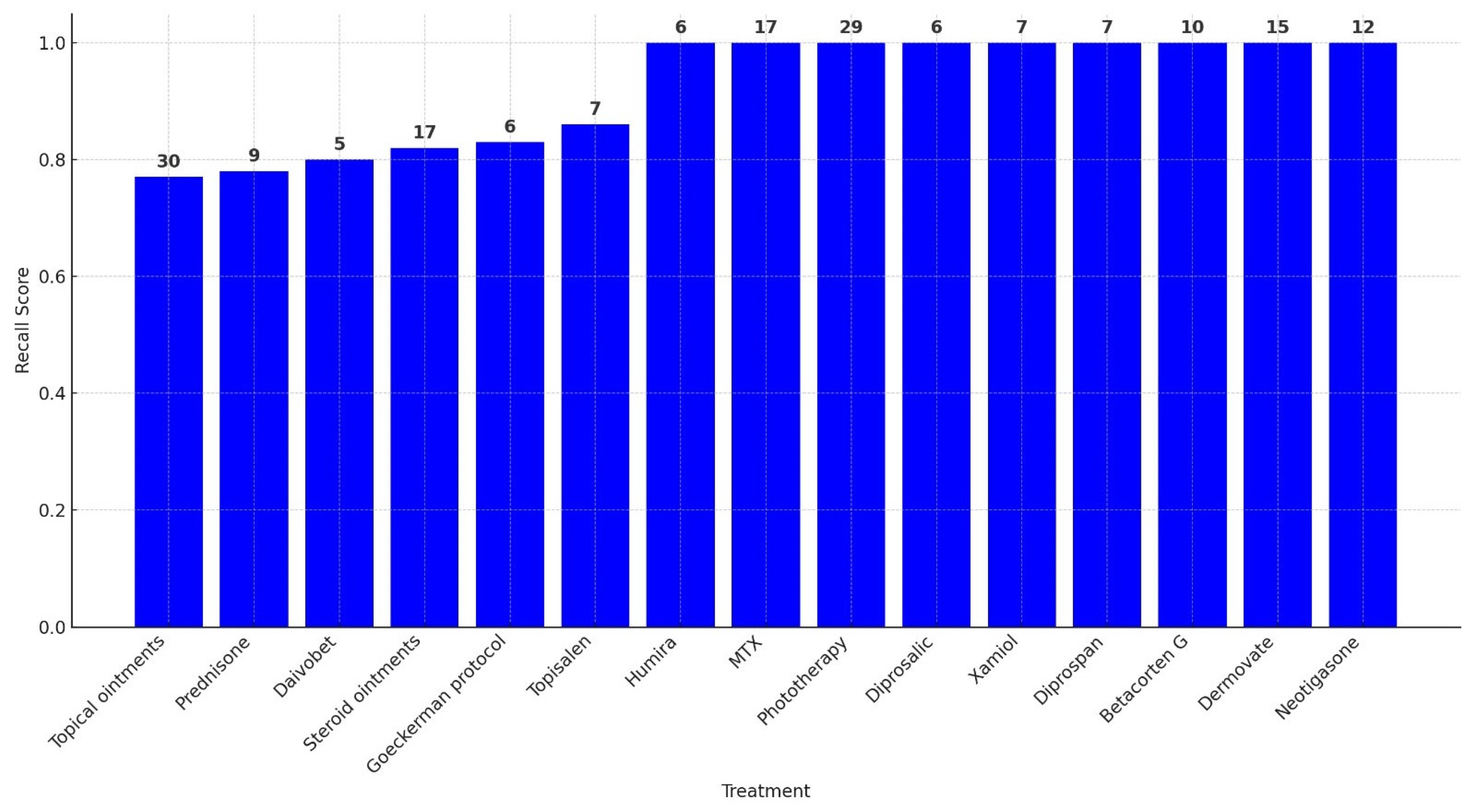

A treatment-wise evaluation, limited to treatments administered in at least five patient records, confirmed these trends. Perfect precision (1.00) was observed for nearly all treatments, indicating a low false positive rate. Recall values were more variable, ranging from 0.77 for treatments such as unspecified topical ointments to 1.00 for well-documented therapies including Humira, MTX, Phototherapy, and Dermovate. The F1-score exceeded 0.90 for most treatments. Specificity was consistently near 1.00. Cohen’s Kappa values ranged from 0.79 to 1.00, with most above 0.86, and AUC scores were uniformly strong, all exceeding 0.88.

Table 2 presents the full set of performance metrics for these treatments, while

Figure 1 illustrates their respective recall values.

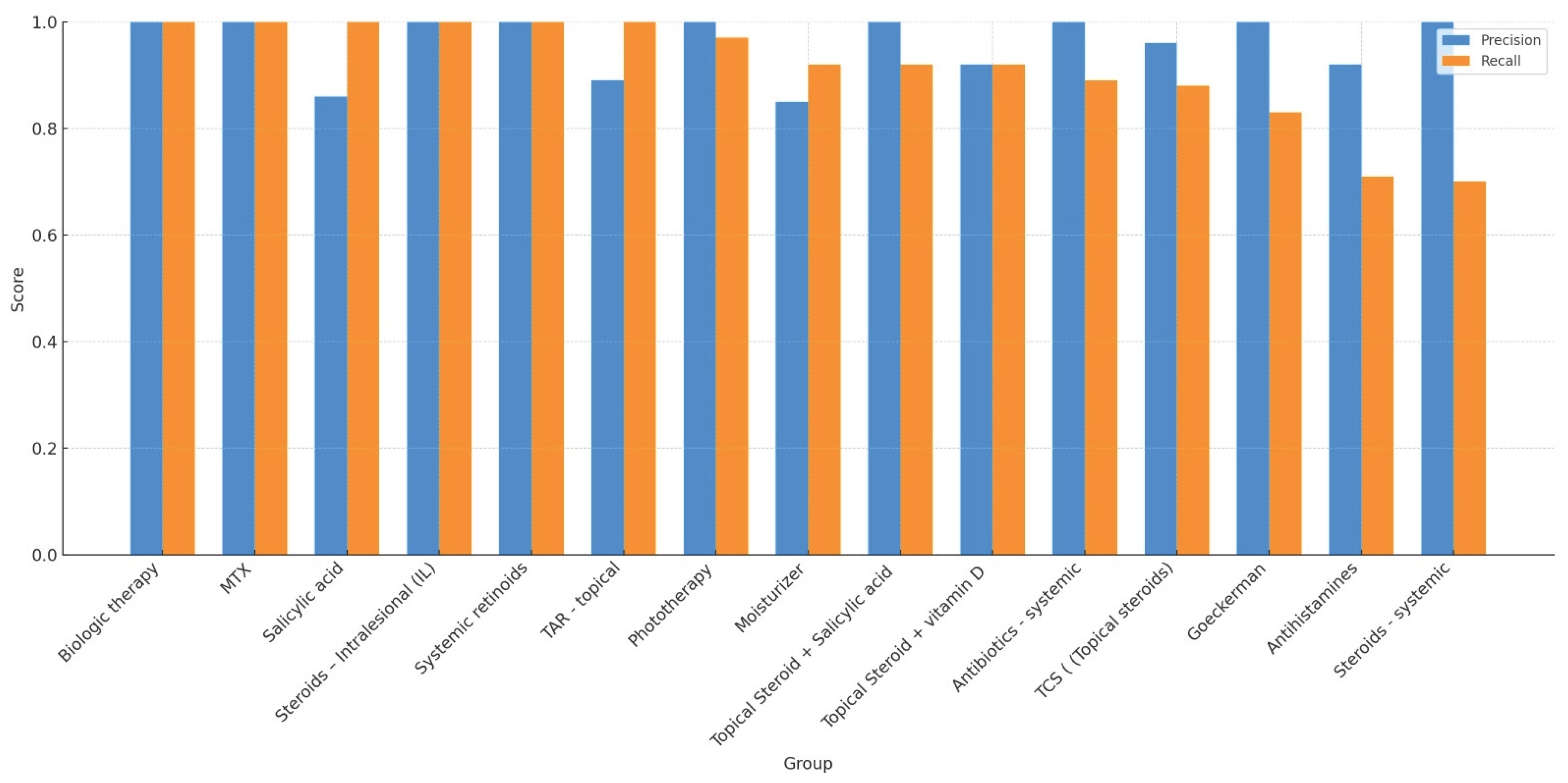

To enhance statistical stability, a group-level analysis was performed by aggregating treatments into pharmacologic categories. We included 15 of 23 possible categories, excluding those with fewer than five total observations. Categories included biologics, topical steroids, systemic antibiotics, antihistamines, and systemic retinoids. ChatGPT-4o maintained excellent precision across all included groups, ranging from 0.85 to 1.00. Recall values ranged from 0.70 (e.g., systemic steroids, antihistamines) to 1.00 (e.g., biologics, MTX, salicylic acid), with most groups exceeding 0.89. Group-level F1-scores were generally ≥0.90, and specificity and accuracy remained high. AUC values consistently exceeded 0.92 across all categories. Cohen’s Kappa was above 0.90 in nearly all groups.

Table 3 presents the complete set of performance metrics for each treatment category.

Figure 2 provides a visual comparison of precision and recall values across these categories. Despite variability in recall for a few categories, particularly systemic steroids and antihistamines, the model's precision and agreement with expert annotation remained consistently high. These findings underscore ChatGPT-4o’s strong performance in extracting real-world psoriasis treatments across diverse pharmacologic domains and documentation styles.

Discussion

The current era of healthcare is marked by unprecedented growth in clinical data, both in volume and in complexity. Electronic medical records (EMRs), originally introduced to streamline documentation and improve continuity of care, have paradoxically created new burdens on clinicians. Numerous studies have highlighted that physicians now spend more time entering data into EMRs than they do in face-to-face patient encounters, with documentation often extending beyond clinical hours and contributing substantially to professional burnout [

17,

18]. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as “pajama time,” highlights how the promise of digitization has not yet fully materialized in everyday practice. Instead of improving efficiency, EMRs have frequently added layers of administrative work that detract from clinical care.

The development and integration of artificial intelligence (AI) systems capable of parsing unstructured medical text and generating structured visit summaries is not merely a technological innovation but a systemic necessity. Healthcare systems worldwide are grappling with rising patient volumes, workforce shortages, and escalating costs. These pressures magnify the need for scalable solutions that can alleviate the administrative load while simultaneously improving the fidelity of medical data. In this context, large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT represent a paradigm shift: rather than asking clinicians to adapt their documentation practices to rigid data-entry forms, AI systems can adapt to the natural language of clinicians, extracting key details with high precision and recall [

19].

Furthermore, the transition from free-text narratives to structured, analyzable data is a cornerstone for modern healthcare priorities such as value-based care, population health management, and precision medicine. Longitudinal tracking of treatments, responses, and adverse events is indispensable for both individual patient care and research into real-world treatment outcomes. Historically, this has required labor-intensive chart review and manual abstraction, limiting the scale and timeliness of insights. By automating the structuring of treatment histories directly from narrative notes, AI-based systems can unlock vast amounts of previously inaccessible information, enabling rapid cohort identification, large-scale retrospective analyses, and data-driven decision support [

20].

It is important to situate this transformation within a broader technological trajectory. The past decade has witnessed incremental advances in natural language processing applied to clinical documentation, ranging from rule-based systems to statistical models and domain-specific machine learning approaches. Each stage improved performance but remained constrained by brittle rules or narrow vocabularies. The emergence of general-purpose LLMs, trained in vast multilingual corpora and capable of contextual reasoning, represents a step change in capability. Unlike earlier systems, these models are not limited to recognizing predefined keywords or phrases but can interpret ambiguous descriptions, handle linguistic variability, and infer clinical relevance across diverse contexts. This allows them to engage with EMRs in a manner that is far closer to human clinical reasoning, bridging the gap between free-text notes and structured data repositories [

21].

Beyond efficiency and accuracy, the integration of AI into clinical documentation has broader implications for the physician–patient relationship and the future of medical practice. By reducing the time spent on clerical tasks, AI-assisted systems have the potential to restore clinicians’ focus to direct patient care, improving satisfaction on both sides of the clinical encounter [

22]. At the same time, the ability to generate comprehensive, accurate, and standardized summaries enhances communication among multidisciplinary teams, reduces the risk of missed information, and supports continuity of care across healthcare settings.

From a research standpoint, these developments also herald a new era in medical knowledge generation. The ability to query large EMR databases with AI tools enables researchers to identify patient subgroups, treatment patterns, and outcome trajectories at a speed and scale that manual chart review could never achieve. This creates opportunities for rapid hypothesis generation, real-world evidence studies, and post-marketing surveillance, all of which are increasingly recognized as essential complements to randomized controlled trials in guiding clinical decision-making.

The adoption of advanced AI tools such as ChatGPT-4o for treatment extraction from EMRs offers significant advantages for both clinical practice and research. In the clinical setting, one of the most promising benefits is the potential to generate comprehensive summaries of a patient’s treatment history with reduced effort and improved accuracy. Traditionally, compiling such summaries during patient intake or follow-up visits requires clinicians to sift through lengthy and often fragmented medical records manually, a process that is both time-consuming and prone to error. While the current use of AI-powered extraction does not yet result in substantial time savings, it introduces a structured and consistent approach to retrieving relevant treatments, which may reduce the risk of missing critical information[

9,

15]. As technology continues to evolve, it may also lead to meaningful time savings in clinical workflows. Moreover, once generative AI models can consistently extract treatments with high precision, EMRs can serve as contextual input for interactive models, enabling the use of clinical notes as file-based data sources in a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) framework, forming the basis for informed, case-specific conversations with an AI assistant.

For research, the implications are equally profound. AI models can be leveraged to perform large-scale cohort identification and retrospective analyses that would be infeasible with manual review. For instance, researchers can efficiently query the EMR database to identify all patients who did not respond to methotrexate (MTX) or who have been treated with a specific medication, supporting studies of treatment effectiveness, safety, and real-world outcomes[

9,

14]. This capability accelerates the pace of clinical research, enables rapid hypothesis generation and testing, and facilitates the development of precision medicine approaches by uncovering nuanced patterns in treatment response across diverse patient populations. As these tools continue to evolve, their integration into clinical and research workflows promises to enhance the quality, efficiency, and impact of both patient care and medical discovery.

This study explored ChatGPT-4o’s ability to accurately identify therapies associated with psoriasis from complex, multilingual (Hebrew-English hybrid) medical records, distinguish them from treatments for other conditions, and compare its extraction accuracy to that of expert human annotation. The goal determined the feasibility and reliability of integrating advanced AI tools into clinical and research workflows for the automated identification of treatments in dermatology.

There is an abundance of LLMs available in the AI ecosystem. We chose OpenAI’s GPT because it has the highest market share (footnotes 2,3) and is widely used as a research baseline (footnote 4). In addition, this study builds on our previous work with ChatGPT[

7]. There are also open-sourced models that can be used, and even further fine-tuned to a specific domain, such as Mistral[

16]. However, in this work, we aimed to evaluate the performance of a general-purpose model in informing and guiding potential users, focusing on the most commonly used publicly accessible option. It is worth noting that other models may achieve higher accuracy, particularly when trained explicitly on EMRs.

One main challenge in extracting treatment histories from unstructured EMRs is the variability in how treatments are described. In some cases, the documentation includes specific drug names, such as methotrexate or calcipotriol, which the model can more reliably recognize as administered treatments. However, in other instances, the clinical notes refer to general treatment categories, such as “topical treatments,” “topical steroids,” or “biologic therapies”, without naming a particular medication. While these general terms likely indicate actual therapeutic use, they pose a challenge for the model in determining whether and how to classify them as concrete treatments for psoriasis.

In our study, ChatGPT-4o demonstrated high overall performance, with an accuracy of 0.99, a precision of 0.96, a recall of 0.91, and an F1 score of 0.94. Cohen’s Kappa (0.93) and AUC (0.98) further supported its excellent discriminative ability and agreement with expert annotations. Treatment-specific and pharmacologic-group analyses highlighted strong overall metrics, although some variability in recall was observed, particularly for treatments with less explicit or more ambiguous documentation.

While ChatGPT-4o performed robustly in treatment identification, a deeper exploration of groups with lower recall provides important insights into model behavior and highlights areas for refinement. For example, the relatively low recall for systemic steroids and antihistamines, despite their presence in many patient records, corresponds with the lower Cohen’s Kappa values for these treatment groups listed in

Table 3 (antihistamines κ = 0.79; systemic steroids κ = 0.77). These findings likely reflect not only model limitations but also clinical and contextual ambiguity. Systemic steroids are generally not recommended for psoriasis due to the risk of rebound flares, and their use is typically confined to atypical cases or early diagnostic workups. In several instances, patients may have received systemic steroids before a definitive diagnosis of psoriasis was established, making it technically correct to list them as part of the treatment history, but potentially confusing for the model, which lacks the ability to infer temporal context or diagnostic intent. Similarly, antihistamines are often prescribed to patients with psoriasis suffering from severe pruritus, yet they are not disease-modifying agents and may be recorded as general symptomatic treatments. This variability in clinical context, coupled with nonspecific phrasing in electronic medical records (EMRs), likely contributed to the model’s reduced ability to identify these therapies as psoriasis-related treatments consistently. In other instances, ChatGPT-4o identified medications that the human investigator did not explicitly mention.

A detailed examination of these lower-performing cases revealed several distinct patterns: One notable source of error was ChatGPT-4o incorrectly interpreting planned future treatments as treatments already administered. This misunderstanding primarily stemmed from ambiguities in clinical documentation, where future treatment plans were not clearly distinguished from historical or ongoing treatments. While this distinction is clear to human clinicians due to context or clinical familiarity, ChatGPT-4o occasionally struggled with this nuance. This emphasizes the need for more explicit differentiation within clinical notes between historical, current, and future treatment plans to enhance NLP accuracy. However, as the models improve, we believe their ability to distinguish past treatments from recommendations will also improve.

An interesting and proactive behavior exhibited by ChatGPT-4o was its holistic approach to psoriasis patient management. ChatGPT-4o occasionally suggested medications not specifically annotated by the human reviewer as psoriasis treatments but identified them as potential therapies due to their management of known comorbidities associated with psoriasis. For instance, ChatGPT-4o spontaneously listed statins used for treating hypercholesterolemia as potentially relevant treatments, justifying their inclusion by citing the well-established association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Similarly, ChatGPT-4o independently considered psychiatric medications prescribed for depression as related to psoriasis management, due to the documented association between psoriasis and depression.

Furthermore, ChatGPT-4o proactively identified in some cases antifungal treatments prescribed empirically for suspected tinea pedis, reasoning that these treatments could be relevant in cases where clinicians might face diagnostic ambiguity between psoriasis and fungal infections or when treating fungal infections complicating psoriasis plaques. GPT-4o provided these additional interpretations with explanatory remarks, allowing human reviewers to explicitly determine their relevance.

Other medications proactively listed by ChatGPT-4o included liraglutide (Saxenda) for obesity management, reflecting careful consideration of obesity as an important comorbidity that dermatologists closely monitor in patients with psoriasis. ChatGPT-4o also noted medical cannabis usage, expressing appropriate reservations about its explicit classification as a psoriasis treatment but nevertheless flagging its potential clinical relevance.

These proactive inclusions by ChatGPT-4o highlight the sophisticated, clinically informed reasoning that AI models can perform, surpassing the strict labeling provided by human reviewers. However, this also suggests the necessity of clear instructions in AI prompts regarding whether to include or explicitly exclude treatments for psoriasis-associated comorbidities, depending on the intended clinical or research context. For research purposes, this ability may lead to more insights into treatment options and patterns.

Another practical reason for treatment misidentification observed was ChatGPT-4o’s occasional misreading or incorrect interpretation of medication names. For instance, ChatGPT-4 mistakenly read "Dermovate" instead of “Daivobet” (both spelled in Hebrew), a misinterpretation that highlights the inherent limitations of AI in recognizing medication names. This demonstrates that, despite overall impressive accuracy, the model can still make specific identification errors, reinforcing the continued necessity of human oversight. These types of errors are also expected to decrease with more training and model improvements.

This work should be viewed within the broader transformation taking place in medicine. Across specialties, AI tools are being developed to analyze patient records and generate structured summaries for both clinical practice and research. Our study demonstrates how this vision can be operationalized: using a general-purpose language model, we showed that treatment information embedded in dermatology notes can be reliably extracted and organized. Although psoriasis was chosen as an initial test case, the approach extends to other chronic diseases where treatment histories are equally complex and clinically significant. By demonstrating that a non-specialized LLM can achieve high accuracy in parsing treatments from routine EMRs, this work provides proof of concept for scalable AI-assisted medical record summarization. Such capabilities have the potential to reduce clinicians’ documentation burden, strengthen continuity of care, and unlock new opportunities for real-world data analysis across the medical field.