The analysis of quantitative and qualitative outputs of schools of thought concerned with urban morphology is crucial for comprehending the urban fabric. These outputs provide important tools for understanding the physical, social, and economic aspects of urban areas. Together, these approaches provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex nature of urban environments and can inform policy decisions related to urban planning and development.

4.1. The Three Schools of Urban Morphology

Numerous studies have been conducted on urban morphology. Moudon and many other language researchers divide them into three major schools: British, Italian, and French [

34]. It is impossible to discuss the many aspects of urban morphology, such as geography, architecture, and urban design, without mentioning these schools of thought, which reflect different types of research; thus, such a classification is critical. The three major schools of urban morphology in Europe have proposed conceptual tools for rationally describing the built environment. They are the University of Birmingham research group, which is based on Conzen's work; the Italian school, which is based on the work of Saverio Muratori; and the French school of Versailles, which is based on the work of Castex and Panerai.

Driven by heritage concerns, the physiological approach initiated by Conzen [

35] mainly favored the study of small towns of medieval origin in England before extending to more complex urban forms. The method consists of dividing the entire urban fabric into systems and studying them separately before analyzing their interactions. Four systems are recognized as being relevant: the

parcel system which divides the land into units of land ownership; the

street system that allows movement between the plots; the

built system, i.e., all buildings regardless of their function or form; and the

system of open spaces, space not built and not included in the street system, whether public or private. The plot and road systems form a coupling called the “mode of distribution” of urban space, while the systems of buildings and open spaces form a coupling called the “mode of occupation” of the urban territory. The first occurs in a two-dimensional space while the second requires a three-dimensional representation. At the level of buildings, only the large volumetric variations are considered, the detailed analysis of the various constructions not being the object of this type of analysis.

Furthermore, a priority of the analysis relates to the persistence or the lifetime of the elements which are part of each of these systems. In the case of the urban plan, these elements tend to oppose a strong resistance to the changes. For example, the very numerous and very old networks of paths through the urban area that are still visible in the landscape today. The use of the ground and the uses of the built forms, on the other hand, tend to be much more ephemeral, the building being in an intermediate position in its resistance to change. Four distinct processes are considered to study these changes. What Conzen [

35] calls “accumulation” concerns the introduction of new urban forms during successive historical periods, and which fit into existing fabrics because they meet the needs of the inhabitants.

Adaptation, on the other hand, is the way in which old forms are modified while retaining their usefulness when needs have changed.

Transformation is a change caused by the existing urban form while

replacement is the substitution of existing forms by others under the pressure of new needs [

35].

The study of these change processes affecting the systems identified by morphological analysis results in the production of maps delimiting the "morphological regions" or landscape units of a city that can be ranked according to their historical origins and types of resistance to change, providing the opportunity to visualize a community's cultural identity. Since Conzen conducted his study of Alnwick [

36] and published it in 1960 i.e., in the past 60 years his school of thought has advanced considerably. Journal of Urban Morphology is a good starting point.

The British approach is a theory that contends recent urban changes are not entirely new occurrences, but rather the continuation of previous alterations processes. This is the cornerstone of the British strategy. As a result, the British school of thought conducts its research on urban morphology by taking into account specific study domains and following a predetermined methodology. Meanwhile, it considers the existing circumstances, as well as the process of change [

37].

The Italian school of typo-morphology developed during the 1960s from the pioneering work of Saverio Muratori [

38] in his study of Venice and Rome. The approach intends to combine the study of urban morphology and that of architectural typology in order to think in terms of the relationship between the urban form (road network, plots, boundaries, etc.,) and the typology; that is, the types of construction (position of the building in the plot, internal distribution, etc.), one type being obtained by the search for co-presence, invariants, on the one hand, and deviations and variations on the other, in the features of the building and the urban form.

Typo-morphology is intended as a response to the crisis of the modern movement in architecture. While the latter disregarded the history of the place, the approach proposed by Muratori is an attempt to reintegrate the history inscribed in the form of the building, in the street and in the plot, within the process of design, an "active history" which, starting from the breakdown of types of urban fabric, is capable of guiding the choices of the present for a long-term project[

39]. Going back in time, the “historical parcellography” developed by Muratori is inspired by the descriptive methods of archeology by applying them to the field of art history, traditionally dominated until then by archival scholarship. It leads its author to describe the typologies of habitat as generators of urban forms and to sketch through this an analysis which reconnects with the tradition of "embellishments" and then "aesthetics of cities" which had dominated the thought of the 19th century. For Muratori, an understanding of history is therefore a prerequisite for the project and this principle will strongly influence the thinking of his followers: Aldo Rossi, Carlo Aymonino, Vittorio Gregotti and Gianfranco Caniggia [

40].

According to Aldo Rossi, indeed the architecture of the city is that of its form which seems like a summary of the total character of urban objects, including their origins [

41]. His criticism of functionalism and organicism is clear, where he asserted “

Functionalism and organicism, the two main currents that have penetrated modern architecture, reveal their common roots, the reason for their weakness, and their fundamental ambiguity…the urban type is reduced to a simple scheme…of thoroughfares, and the architecture is considered to have no autonomous value” [

41]. There is a dialectical relationship between the typology of material objects that make up the city and history as a revelation of shared values. Rossi sees the city as a collection of material objects, man-made material objects, which are built over time. In addition, he views history as the study of the actual formation and structure of urban objects, which is a synthesis of shared values.

The

type, according to Muratori, is built from the relationships between the elements of the plot, the street network, and the built and unbuilt fabrics. The type he explains is "something permanent,” a logical principle that exists within and which constitutes the form [

38]. Types for Muratori and his followers aid in explaining the continuity of the urban structure, with its permanent characteristics and distinct identities. They transmit shared values over time and shape and direct the city's future, contributing to its evolution. Similar to Rossi, where the built environment reveals society; the urban form is a result of the history and memory of its inhabitants; each place is unique and has its own identity.

The Italian school of urban morphology examines what is happening by examining types in the city's tissue. This approach aids in understanding how cities have evolved and changed over time, with special attention paid to different neighborhoods that are evolving differently even though they are participating equally in the growth around them; understanding these differences can also tell us something about why one area may be more prosperous than another—or whether some change has been for the better or for the worse.

The French school of Versailles, led by architect Jean Castex, sociologist Jean-Charles Depaule, and architect-urban planner Philippe Panerai [

42], adopted certain theoretical concepts from the Italian school of thought as responses to modernism. Nonetheless, intelligent debate about urban life influenced the development of inventive architecture. It was also linked to the harsh criticism of sociologists such as "Henry Lefebvre."

The French approach to urban morphology is then informed by sociology as well as architecture. This two-sided perspective leads to a number of goals, including a strong connection with sociological sciences, an examination of how people and their environments are linked in two ways, and the discovery of a way to discuss design theory in both theoretical and practical terms [

37]. This way of looking at things has resulted in some significant discoveries, such as the fact that cities are not only physical places, but also social creations. This point of view has also demonstrated the importance of considering how urban spaces function and appear.

Due to the examination of various models and theories, the French school of thought does not believe in any distinction between "before" and "after." It considers how an idea affects patterns, types, and forms in relation to one another. The most significant feature is its consideration of theories of urban form creation. Because traditional morphological analysis cannot explain modernism and its new spatial concept, the French school of thought developed its own framework to incorporate observational and perceptual studies [

37].

Panerai and Castex write in their book

Urban Forms: The Death and Life of the Urban Block [

42], French architects conducted methodological-morphological experiments. Urban planners continued to believe that the magic of planning was based on large scales, and sociologists who sought out city residents and criticized bulldozer restoration swayed numerous political factions. They consider the consequences of this type of refurbishment to be equivalent to dismissal [

42]. As a result, it is clear that the impact of French renovations established and clarified a collection of scholarly ideas on the theme of urban form.

Panerai and Castex developed the "Island" concept as a critical component required to study the city of the twenty-first century because modernism and its new spatial concept cannot be understood through traditional morphological analysis. As a reaction to Modernism's negative effects, the concept of "Island" provides an alternative approach to morphological studies' deficiencies in the third dimension. As a result, the French school of thought developed its own framework for incorporating perception and observational studies [

43].

Before concluding this section's analysis, we compare each school's Theoretical foundation, Main purpose, Approach, and Early Pioneers using a comparison chart.

The three schools of urban morphology, the contributions of which we have just summarized, without a doubt constitute important tools in the training and practice of architects and urban planners (

Table 1). Nevertheless, several criticisms have been voiced [

43,

44]. Such criticisms are based on an old conception of the city, described by some as nostalgic, which above all refers to a dated – and therefore obsolete – functioning and form of the city. For example, spatial continuity, parcel divisions, and streets are not understood in the same way in the old city as they are in the modern one, especially in view of its metropolitan transformation. Such approaches cannot then be suitable for objects as different as the traditional city and the new metropolitan reality, where the connection to transport networks matters more than the contiguity to the built front and where the investment cycles of real estate capital follow, as well as the influence of logic that was not present in the traditional city. Accordingly, some believe that the interest of these morphological analyses is limited to the description of urban forms and cannot be an instrument of their realizations which are part of a context study and not in an urban project.

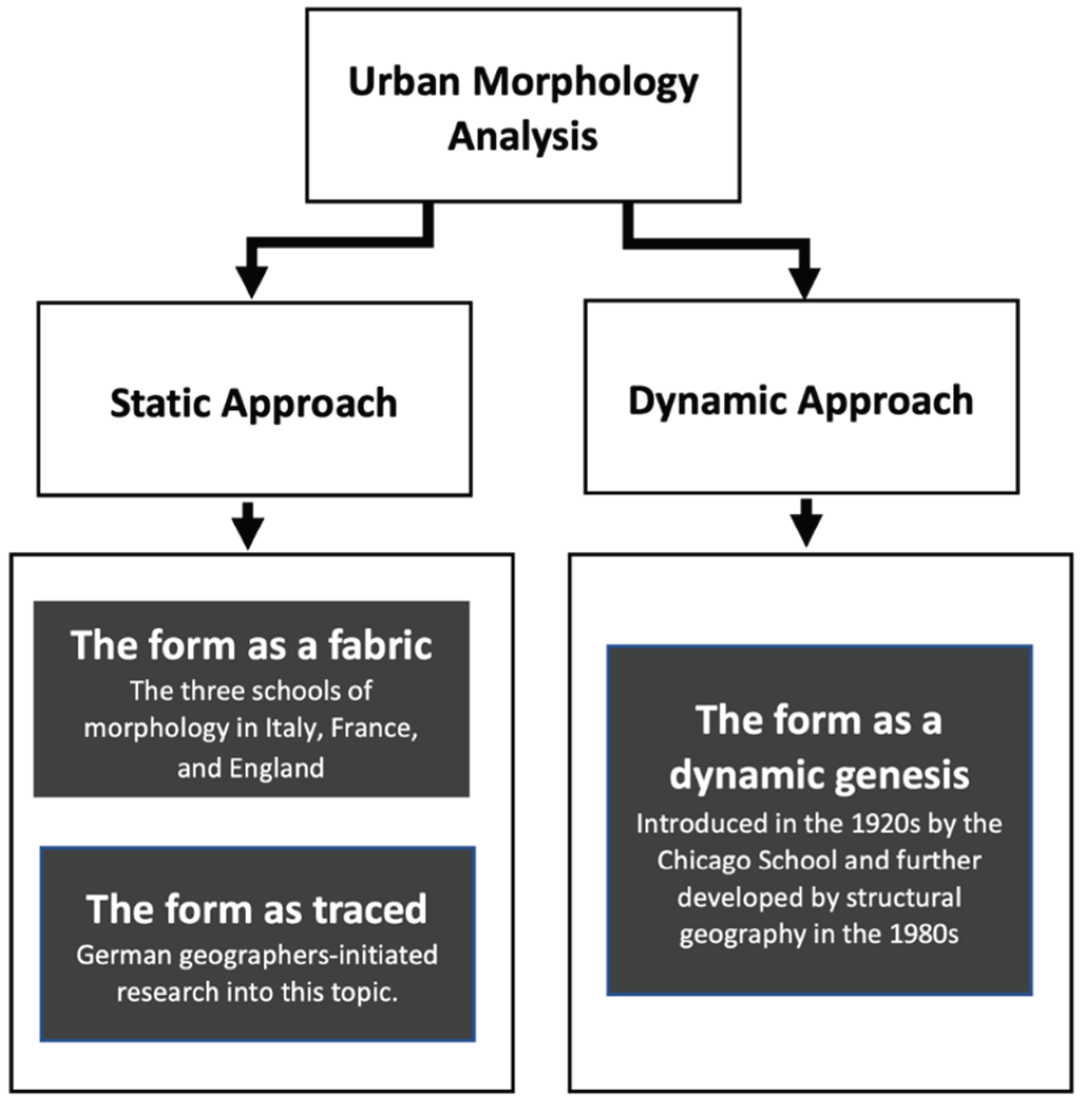

4.2. The Dynamic Approaches to Urban Form

The theoretical approaches presented thus far address the issue of urban forms from a static standpoint, each favoring classification or typology in order to propose tools for intervention in the built fabric in their own way. They are thus primarily taxonomic and descriptive, even if some are interested in genesis processes but limit their research to history or economic production modes. One particular limitation of this approach is that it does not allow for the prediction of the effects of an intervention on the surrounding territory, assuming that what is desired is a transformation of form rather than a change in function. Another shortcoming is that these approaches frequently fall into the trap of essentialism, attempting to identify those elements that constitute the "essence" of a city and are thus unalterable. Finally, it should be noted that the majority of these theories are developed from a Eurocentric viewpoint, making them difficult to apply to non-Western contexts. As a result, theoretical frameworks that can account for the dynamic and complex nature of cities, as well as their geographical and cultural specificity, are required.

This section will supplement those by proposing models of city spatial organization generated by dynamic processes related to individual or group mobility. Both dynamic and explanatory approaches to space occupation will be used for the appropriation and development of these spaces. We begin with the work of the Chicago School, whose authors were among the first in the first half of the twentieth century to develop genesis models. We then turn our attention to more recent theories, such as the structural theory of urban morphogenesis, whose original concepts deepen and enrich the previous theories' intuitions and hypotheses. Understanding these theories allows us to gain a more complete understanding of how cities are organized and evolve over time.

4.2.1. The Chicago School

The Chicago School [

45,

46,

47] considers the city a human community, where people, institutions, and space are interdependent. The city's social mechanism places people far from their homes. The development of the city's districts, which leads to a configuration, and the complexity of population movements for space occupation are spontaneous, unplanned external processes. Self-organized processes resemble life formation.

No social class or group dominates space layout in the Chicago School's city. The city is organized by self-organizing processes like living things, not impersonal social forces. Chicago School authors use animal and plant ecology terms. A "super-organism" city considers society and space. It considers the impact of space on individuals and institutions. It means studying how space and cities affect social group formation. Robert Park, leader of the Chicago School, says people can affirm and reproduce their lifestyles through urban space. Large cities, with more selection and segregation, have morphological characteristics not found in smaller populations[

31,

48].

Park says urban planning distinguishes a city from a village or small town. The city isn't buildings and people. It's space-organized, giving the city individual or group positions. In this way, society's morphology depends on individual relationships. We can only understand social ties by studying this type of organization, positional relationships in the city. Competition regulates positional relationships despite socioeconomic, cultural, project, and action differences. This phenomenon resembles animals and plants fighting for life [

49].

Prestigious businesses, political power institutions, and large company social centers will occupy the city's most coveted areas and strategic positions, creating urban organizing centers. Residential habitat distribution appears subordinate to land appropriation but follows similar laws. Light industries around the central business district polarize modest residential neighborhoods for workers and new immigrants. Wealthier social strata live in single-family homes far from central congestion [

49].

Park calls the city's distinct zones "natural areas" whose borders are "natural limits" because both are the result of a double process of genesis: a self-organized selection process through competition between individuals and groups for the appropriation and occupation of urban space and an integration process motivated by the affirmation of individuals' group membership. No outside actor or planner controls these processes. These processes unfold naturally, creating zones with natural, not artificial, boundaries [

49]. The city's space does not match census sectors or legal and political districts. The city's space is the result of self-organizing forces that delimit zones where social groups establish themselves without official limits imposed for specific reasons.

4.2.2. The Relationship of Spatial Organization to the Economy

Park, Burgess, McKenzie, and Wirth describe competition, interaction, and association in terms of money. Land and real estate rent regulate land use competition, as do unequal opportunities for social actors to occupy the most coveted and expensive sites. Urban space competition mirrors animal ecology's "struggle for life." This appropriation seems competition- and market-regulated. The "strongest" is the one with a privileged location and the financial capacity to defeat his competitors and retain the coveted location, according to McKenzie's texts [

50]. Thus, land prices reflect competition and constraint. Land and building owners no longer invest in maintaining and enhancing a pending real estate heritage, causing physical and social degradation in transition zones around the central core. Groupings are based on economics.

Chicago school competition goes beyond market-based competition. Competition means crisis, upheavals, transformations, mutations, etc. Dynamic, not linear, leading to stable equilibrium. This competitive atmosphere will inspire new mobility ideas. "Agglomeration pulse" allows spatial study of social changes. This is different from commuting or shopping. Daily, weekly, or seasonal vessel movements demonstrate a stable equilibrium. The Chicago school's mobility concerns urban space appropriation and occupation. Park: “

Mobility (…) measures social change and social disorganization, because a social change is always based on a change of position in space and any social change, even that which we describe as progress, involves social disorganization” [

13].

Mobility creates urban jobs through individual and group movements towards spatial occupation zones whose social content it can modify and push back. It shows the city's demographics. Mobility can affect land values and the distribution of activities and residences. "Something's happening" when land values rise or change quickly. These cities are changing. As a result, land prices aren't indicators of a stable, static distribution of activities and people. Dynamic localizations are of interest. Classical economics and the Chicago School disagree on the definition of competition. Dynamic notions of dominance, invasion, and succession that explain city configurations are not based on spatial economics' simple aggregation of individual behaviors.

4.2.3. The Models Developed by the Chicago School

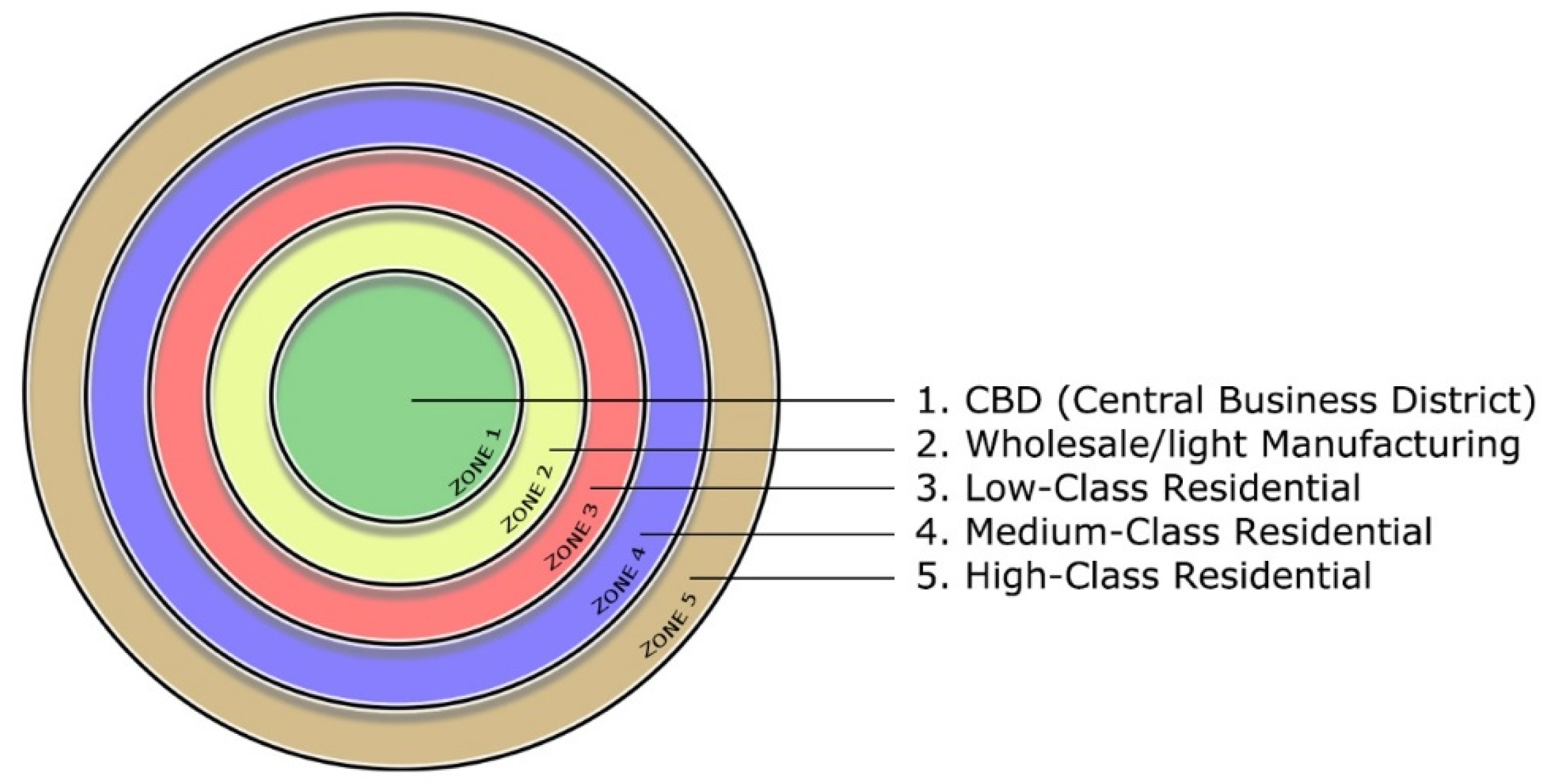

The early 20th-century Chicago School developed spatial models. These models were created to study North American cities, but they're useful for understanding other large cities, especially those with high immigration. Ernest Burgess proposed a concentric model for Chicago in 1925. (Figure 8).

Figure 2.

The concentric Burgess models. Source: Redeveloped from [

45].

Figure 2.

The concentric Burgess models. Source: Redeveloped from [

45].

Most roads converge in Zone 1, Chicago's CBD. It includes the Town Hall, public administration, department stores, luxury hotels, theaters, performance halls, skyscrapers, and corporate and bank headquarters. 500,000 people worked there in the first half of the 20th century.

Zone 2 is a densely built, deteriorating area with poorly maintained buildings. The wealthy abandoned this area of quality buildings long ago. Land values no longer rise. Plots of land and buildings are invested in by speculators, so they fall or vary in price suddenly. The whole sector is socially unstable because industries and labor are being replaced by marginalized people living in decrepit housing. This is Hobohemia, the "tramp" district near the Loop. Here, newcomers settle, and ethnic diversity is highest. There's Little Italy, the Jewish Quarter, Chinatown, the Greek Quarter, the Polish Quarter, and “Bronzeville”, “the Black Metropolis” on Chicago’s South Side.

Zone 3 is continuously built and has a population with modest incomes but better family and community structure. Workers who left Zone 2 slums have moved into newer apartment buildings or small houses where they are sometimes owners or tenants. Zone 4 comprises luxury houses and apartments. Shopping areas, hotels, villas, and mansions abound. This is where the wealthy live and embrace the American individualistic lifestyle. There are many parks and green spaces. Zone 5 includes rural suburbs, where small estates are far from the business center and attract middle-class workers who commute daily.

Such a concentric zoning translates city growth stages and refers to a plant ecology model. In nature, resistant species colonize bare earth first. New plants gradually replace the original inhabitants. There are dominance and succession phases. The same is true for urban growth: Burgess’ model shows a succession of occupation patterns. Zone 2 initially attracted a wealthy population and dilapidated luxury buildings over time. Later, these buildings became apartments and urban parks were subdivided to house the poor and migrants.

Let's keep two ideas in mind: on the one hand, there is competition between social groups in the city for land use, and on the other hand, social belonging is reflected spatially; neighborhoods are not only distinguished by their distance from the center, but also by their occupations, which affect the social composition of the residents. Dynamically, Burgess model has:

An attractiveness of the center. This attractiveness is due to most jobs being performed in the city center and the value of having a short commute to work.

A process known as "invasion", which occurs as a result of this attractiveness. It is an agglomeration effect centered on the appealing center.

The aspect of “resistance on the spot”, as a reaction to social group competition. This opposition is manifested by the assertion that individuals are members of a group. Members of groups prefer to reside together and prefer that members of other groups reside elsewhere.

Resistance on the spot has two outcomes: if it fails, it leads to position abandonment and repression in the periphery (groups abandoning neighborhoods); if it succeeds, it manifests as adaptation on the spot and position consolidation (formation of quarters: the Greek Quarter, Bronzeville, Chinatown, etc.).

The various concentric zones are formed as a result of such a dynamic sequence of invasion-resistance-abandonment-adaptation.

In this model, the city grows from the center outward, and it expands in all directions at the same rate. Isotropic model. In growing areas, people move to the border. Certain activities or social groups determine the city's evolution. Natural factors affect city growth. Lake Michigan limits Chicago's growth to the north, west, and south. Lakeshore areas are densely developed.

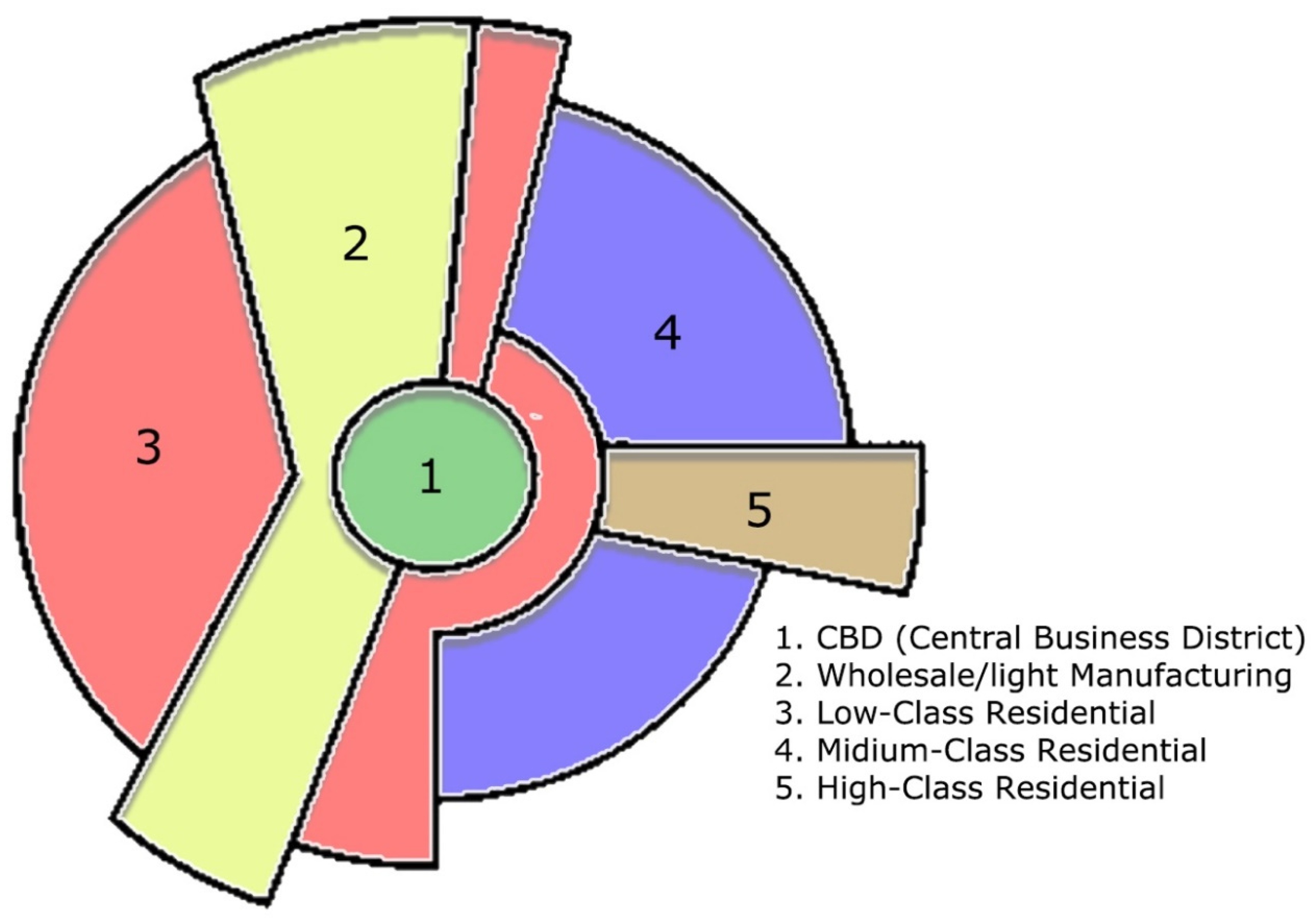

In (1939) Homer Hoyt added transportation disruptions to the Burgess model. This "sector" model describes growth and transformation by adding divergent rays, axes, or sectors. The concentric model ignored the structuring effects of transport routes on neighboring areas, with places near routes being more attractive. Hoyt adds permanence and local specialization to the previous model: neighborhoods along radial roads can develop faster. This creates a city model organized by direction (Figure 9).

Figure 3.

Hoyt's sector model. Source: Redeveloped from [

45].

Figure 3.

Hoyt's sector model. Source: Redeveloped from [

45].

Zone 1 is a business center, 2 is wholesale businesses and industries, 3 is working-class, 4 is middle-class, and 5 is wealthy. not duplicate Zone 5 no longer sits on the city's outskirts but enters along an attractive axis. In Chicago, this attractive axis is the waterfront property to the east of downtown, known as the "Magnificent Mile" (as well as the Gold Coast residential area to the north), home to many of the city's landmark commercial buildings: the Wrigley Building, Tribune Tower, the Chicago Water Tower, and the Allerton, Drake, and Intercontinental Hotels. Zone 2 industrial and wholesale are affected.

Hoyt's model has both a center and radial path attractiveness, with the same dynamic sequence as Burgess’ model of “invasion, resistance, abandonment, and adaptation.” It responds to social group competition. If the resistance fails, it leads to periphery repression or local adaptation. Therefore, Hoyt's model assumes the same dynamic processes that shape the city. This model is more refined than Burgess' because it introduces axes to organize and structure space. From this sectoral model, urban growth factors follow:

Attractive high-rent areas contribute to a city's growth.

During growth, sectors can widen and lengthen.

When a high-rent class moves into an area, they stay for a long time.

High-rent neighborhoods are moving outward. These sectors don't invade others. They fill empty spaces.

When a high-rent class leaves, a low-rent class moves in.

High-rent areas develop along the most efficient transport routes, either toward an affluent suburb or shopping centers or natural parks.

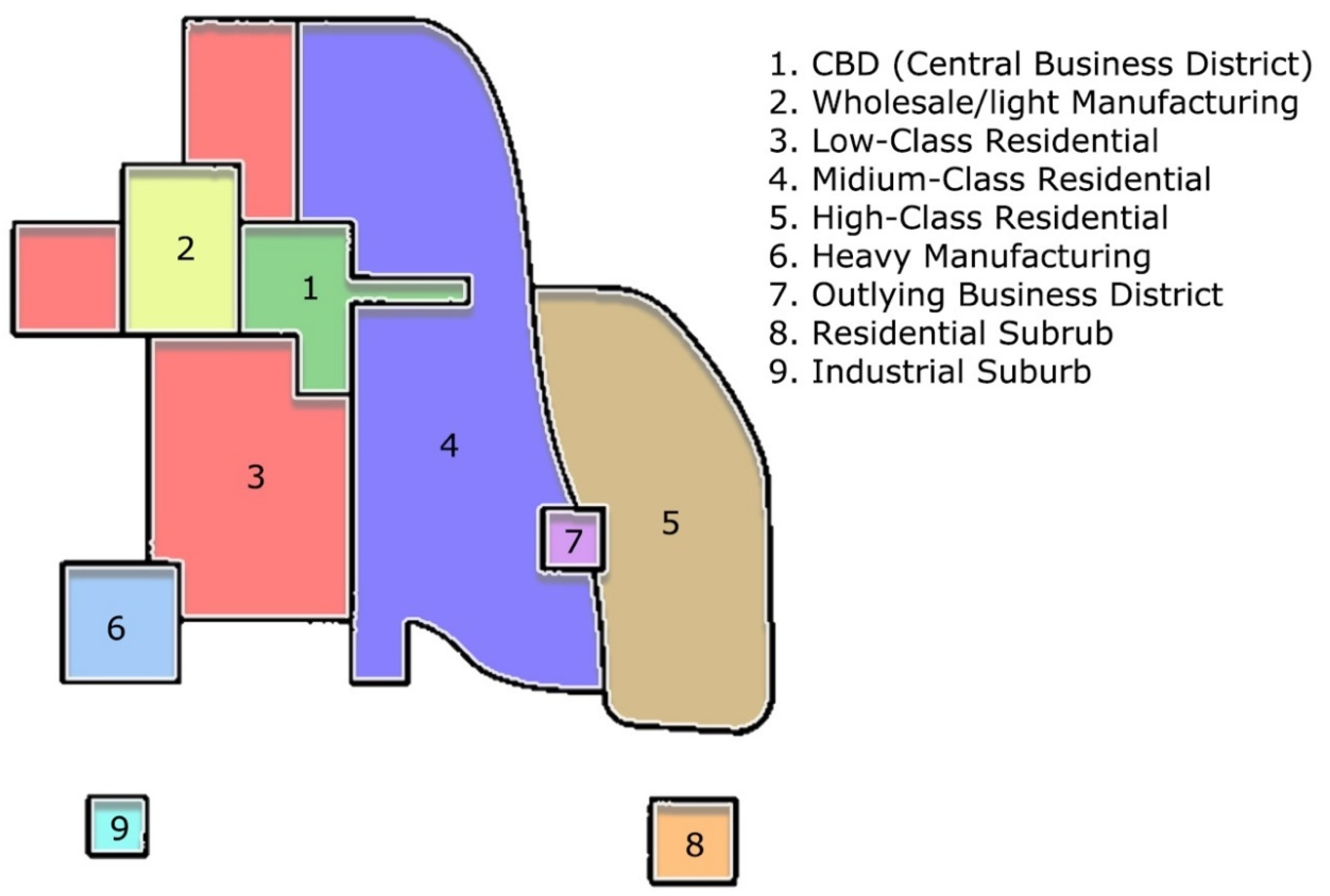

As a result, Hoyt's model complements Burgess's model. A combination of the two models, a spatial division into concentric rings within which appears a differentiation by sector, can be very useful. However, the Chicago school of thought proposed a third model. This is known as the "multiple nuclei" model. Hoyt's model proposed that a city can have multiple attractive places connected by transportation axes (Figure 10). In this sense, Harris and Ullman proposed a polycentric city scheme in 1945. With the multi-kernel model, the scheme introduced by Burgess and perfected by Hoyt becomes more complicated. The existence of three factors contributes to the development of independent centers:

Agglomeration economies, or the clustering of similar and complementary activities in the same industry

A distance between wealthy or affluent and underprivileged neighborhoods

Competition for land use, certain activities, or certain social groups not having the means to afford more advantageous locations.

Figure 4.

The multiple nuclei model of Harris and Ullman. Source: Redeveloped from [

45].

Figure 4.

The multiple nuclei model of Harris and Ullman. Source: Redeveloped from [

45].

In Harris and Ullman's model, there are several appealing centers: well-defined places as well as specific axes aligned with transport routes, resulting in greater sector differentiation. However, the same dynamic processes are always at work: the invasion-resistance-abandonment-adaptation sequence.

The three Chicago school models generate the city's abstract spatial structure. In these models, urbanites' mobility isn't random. It follows privileged directions: centripetal from periphery to center (invasion) and centrifugal from center to periphery (succession). Collective representations of group membership and rejection govern cultural and social grouping. Because of their mobility, ethnic communities and social groups expand in the city. Spatial positions determine social groups' existence. They can assert themselves and rearrange because they're stable [

48,

49,

50].

Many global cities have been studied using these three models (Paris, Rome, Montreal) [

50,

51,

52]. They're also used together to analyze complementary city aspects. In this case, concentric zoning areas help understand the distribution of people from family status statistics, while sectors seem better suited to the distribution of groups by socioeconomic level and the multiple nuclei at the spatialization of ethnic communities. They remain interesting despite theoretical limits that make new morphogenesis models possible.

4.3. New Model of Morphogenesis

In the past 30 years, research on complex systems has deepened the Chicago school's hypothesis of self-organized genesis processes. According to Dauphiné [

53], there are three types of complexity in urban studies: 1) structural complexity, which characterizes the emergence of spatial structures from the interactions of multiple social agents, 2) level complexity, linked to the interweaving of different scales or levels of organization, and 3) dynamic complexity, involving non-linear evolution processes that lead to unpredictability of the system's future effects, even when the factors are simple. A city can respond to all three types of complexity simultaneously[

53].

Thus, researchers have used Ylya Prigogine's theory [

54] of dissipative structures to show that the evolution of city systems is subject to self-organized nonlinear dynamics. Others have used Mandelbrot [

55]fractal geometry to model the fragmentation of fabrics and the interlocking of scales (fractal “self-similarity”, urban fabric that looks similar at different scales) in the city. Others have relied on physicist Hermann Haken's synergetics [

56] to reconstruct how multiple levels of organization weigh on the city, from the individual decisions of social agents to those of entities and collectives that govern us[

57]. All these works are part of a vast scientific program that Alain Boutot called a "morphological revolution" [

58]. The same applies to the theory of urban morphogenesis developed by Desmarais and Ritchot [

33].

4.3.1. The Theory of Urban Morphogenesis

The concepts of urban morphogenesis come from Gilles Ritchot [

59,

60] structural geography, which Desmarais [

50] showed could be enriched by morpho-dynamic models developed by mathematicians of morphological structures like René Thom and Jean Petitot [

61,

62]. This theory explains how the complexity of city fabrics (architectural forms, parcels, islets, road networks, neighborhoods) is organized by simpler hidden forms (spatial structures) generated by self-organized dynamics. As previously stated, the theory incorporates three types of complexity: structural complexity (the study of interactions between social actors for the appropriation and occupation of urban space); level complexity (the analysis of three spatial layers superimposed in the genesis of forms); and dynamic complexity (the study of three types of self-organized processes that occur over time) (anthropological, political and economic).

Desmarais and Ritchot [

33] define urban form generation as a "morphogenetic pathway" that spans levels ranging from the deepest to the most visible. They are as follows:

The investment of anthropological values in very particular organizing centers that they call “vacuums”.

Flows or trajectories of political control of settlement mobility appropriating spaces around vacuums.

Conflicting settlement mobility trajectories create hidden structural positions.

The diversified valuation of these positions by the situation rent.

the construction of concrete forms of spatial occupation stimulated by rent.

the profitability of concrete forms through economic activities.

This global process includes three hierarchical layers of spatiality where deep vacuums are created by anthropological investment; hidden forms or positional structures result from political appropriation; Economic occupation dynamics determine the surface layer of concrete forms.

The concept of "vacuum" was introduced to address the origin of cities and their first "ecumene's", or areas of permanent inhabitation. This concept designates a semiotic-dynamic structuring void. On the one hand, vacuums are invested with anthropological values that make them attractive by conditioning a temporary gathering of the concerned populations within their neighborhood. On the other hand, they are subject to a ban on permanent residence, which constrains the dispersal of these populations outside their neighborhood and their installation in a distant location.

The symbolic values spatialized by vacuums correspond to deep meanings, called “unconscious codes” that include sacred and profane, salvation or fall, sovereignty, strength, fecundity as described by Claude Lévi-Strauss [

63], interoceptive semes identified by Algirdas Julien Greimas [

64], or subjective pregnancies noted by René Thom [

62,

65]. It is for these reasons that vacuums become gathering places for society's founding rituals. The ban on permanent residence forces the populations to leave the vacuums and return to their homes, which is repulsive.

The

Lavinium, or the Celtic sanctuary of Lendit at the origins of Rome and Paris, the dance square in the center of the Bororo village in the Amazon or the one far from the Melanesian villages in the Vanuatu archipelago, the Buddhist stupa or the Sumerian ziggurat are all examples of vacuums analyzed by Desmarais [

66,

67,

68]. The values and duration of the prohibition change over time and space, but these two conditions must be met for a vacuum to exist. Partial lifting of the ban may allow certain groups of actors – priests, warrior-kings, or high figures in society – to permanently reside inside a vacuum, thus the construction of a temple, palace, citadel, or set of prestigious monuments whose architectural characteristics symbolize the values invested in the place, while a total lifting of the forbidden would abolish any singularity of the place.

Deep spatial structuring is followed by dynamic spatial appropriation in which political control of settlement mobility intervenes. For the founders of the Chicago School, qualitative changes in spatial appropriation and occupation shaped the city. This hypothesis can be deepened by Desmarais and Ritchot's [

33] concept of "political control of establishment mobility." This concept accounts not only for the movement needed to change locations, but also for the political balance of power involved. If a social actor controls his movement towards a place of establishment, his trajectory is "endoregulated." If another actor or an unfavorable context constrains his movement, his trajectory is "exoregulated." "Exoregulated" describes its trajectory. The political modality of power that controls displacements for space appropriation and occupation is not only economic, as we saw with the Chicago school's notion of competition. Controlling establishment mobility can play on other registers, such as property law.

By crossing “endoregulated” and “exoregulated” qualities with the two directions mobility trajectories can take in a city (polarizing or centripetal flows from the periphery to the center and diffusing or centrifugal flows from the center to the periphery), we identify four classes of mobility leading to as many positions in the urban space: the gathering which brings together the polarizing “endoregulated” trajectories; the dispersion which brings together the diffusing endo (

Table 2).

The four classes of establishment mobility correspond to as many sequences that are articulated between them according to a cyclical dynamic: the evasion of social actors from the center who control their mobility towards the periphery conditions the subsequent gathering of other endoregulated actors in this center, which is accompanied by a rise in land and property values that forces the poorer actors who have remained ostracized to the periphery. When these trajectories meet in the city, conflicts and competitions for appropriation and occupation of positions arise, generating differentiation and complex spatial structuring over time.

4.3.2. The Structuring of Space

We have already mentioned that the three models proposed by the Chicago School for reconstructing city internal structures are based on the same hidden representation of space: an "isotropic" space with attributes that are identical in all directions. This model, however, raises two major concerns:

Defined by differentiated structural positions and generated by the four classes of trajectories recognized by urban morphogenesis, an "anisotropic" representation of space is recommended. This method seems essential "to understand spatial structures." Because, to develop

“an evolutionary theory, it is necessary to conceive of a relative space, which is defined by these positions and these flows” [

69].

The anisotropic space model by Desmarais and Ritchot [

26] reconstructs how "morphogenetic gradients" structure the space of cities in qualitatively distinct positions. High-value gradients, or "ridge lines," created by “endoregulated” flows intersect low-value depressions, or "thalweg lines." The spatial structures are an "axiological relief" of polarities. The superposition of two ridge lines locates a massif of very high value where “endoregulated” gathering is present; the crossing of two thalweg lines corresponds to a basin of very low value where “exoregulated” concentration is present; the superposition of a ridge line and a thalweg line result in a collar effect, a "threshold" of mean value where gathering, and concentration are co-present with equal intensity (Figure 11). This threshold configuration model has been used to model the growth of Paris, Rome, and Montreal.

Figure 5.

Threshold configuration. Source [

51].

Figure 5.

Threshold configuration. Source [

51].

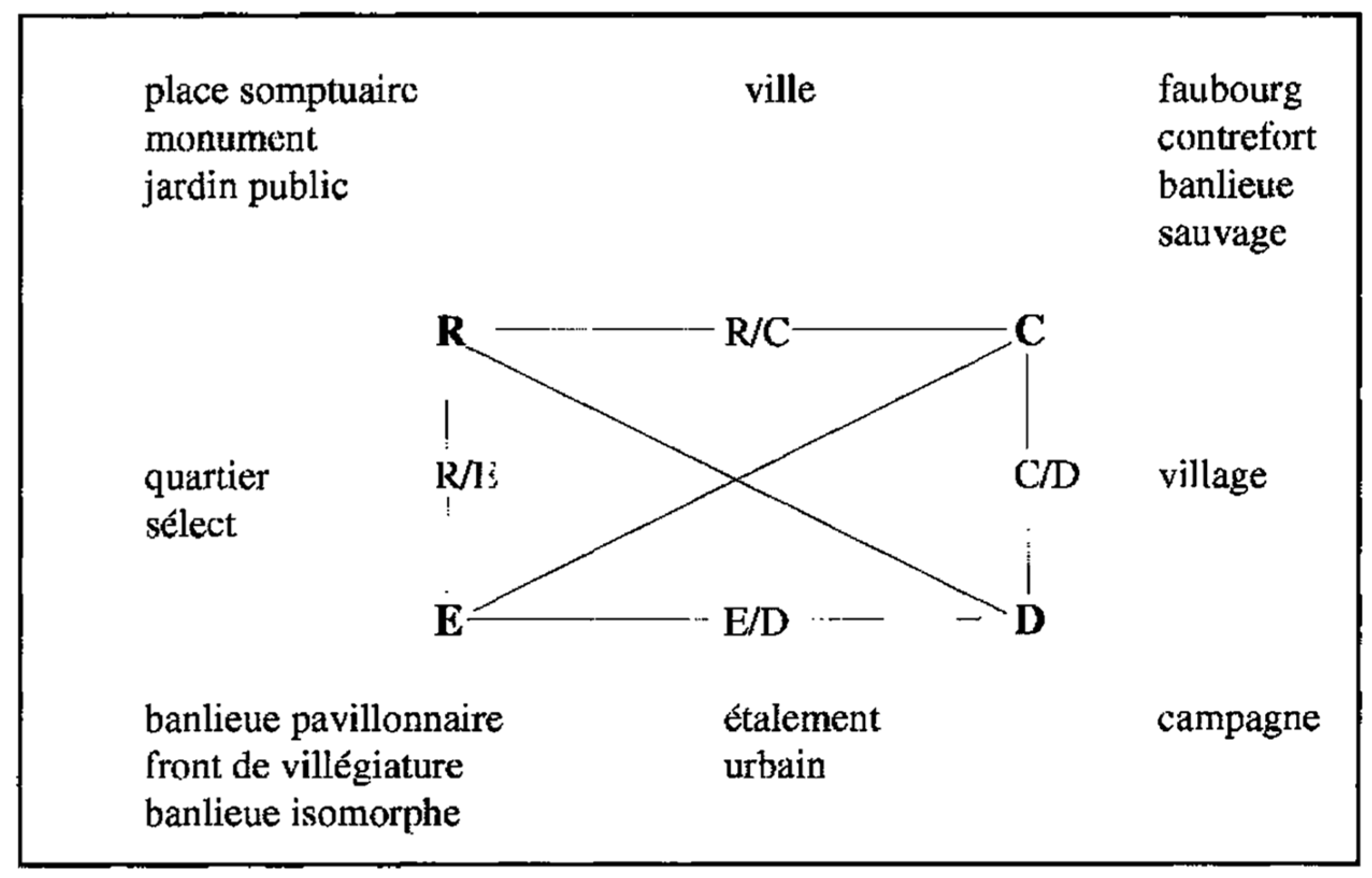

To conclude the morphogenesis school review, consider a few benchmarks for better understanding the relationship between the concrete forms that comprise urban landscapes and the hidden forms that structure them. (Figure 12) shows some examples of relationships between different neighborhood units and the structural positions generated by the trajectories:

Monumental forms with sought-after architecture, sumptuous urban squares, temples, institutional buildings, luxury apartment towers, and large urban parks are gathering places (R).

Working-class suburbs and neighborhoods, low-rent complexes (HLM foothills), and informal housing neighborhoods (wilderness suburbs) are concentrations (C).

The city is organized structurally by a threshold configuration where (R/C) positions overlap. High-value buildings and low-value suburbs rub shoulders.

The city's influence villages externalize (C/D) positions. In each, an institutional island (church, town hall, post office, etc.) stands out from craft houses, shops, and workshops.

The countryside is typical of dispersed positions (D) dependent on the city because livestock and agriculture have low demographic densities.

The sprawl of suburbs often far from the dense agglomeration project concrete urban forms (E/D) onto rural positions.

Affluent suburbs as well as luxurious resort fronts materialize escapes (E).

Bourgeois and select neighborhoods combine positions of escape and positions of assembly (R/E).

Artisan, commercial or middle-class neighborhoods combine escape and concentration (E/C).

Certain public squares or monumental voids materialize vacuums that give rise to gatherings followed by dispersals (R/D).

These are only a few examples among many. At this level of concrete form diversity, the conceptual tools developed by urban morphogenesis theory can be used in conjunction with those proposed by the theories of urban morphology presented in this chapter. Thus, description and explanation can complement one another and serve as guides for the urban project.

Figure 6.

The relationship between concrete forms and abstract forms. Source [

33].

Figure 6.

The relationship between concrete forms and abstract forms. Source [

33].