I. Introduction

The late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries witnessed unprecedented encounters between China and Europe. Among the figures who facilitated this dialogue, Matteo Ricci stands out as a pivotal intermediary. As a member of the Society of Jesus, Ricci arrived in China in 1582 and spent nearly three decades engaging with Chinese officials, literati, and imperial circles. His career coincided with the Jesuits’ broader policy of cultural accommodation, which sought to reconcile Christian doctrine with local traditions in order to secure intellectual and political legitimacy (RULE 2007,41-44; HSIA 2012,33-35).

This article focuses on Ricci’s adaptation to Chinese society, his philosophical and theological engagements, and his role as a cultural bridge between East and West. It argues that while Ricci successfully introduced Western science and reshaped European perceptions of China, his project of syncretism also revealed the inherent tensions of cultural mediation. The following sections trace Ricci’s biography, strategies of adaptation, intellectual clashes, and enduring legacy.

II. Matteo Ricci’s Life and Activities in China

Arrival in Asia and Early Struggles

Ricci left Europe in 1577, spending several years in Goa, where he continued his theological training and learned the basics of missionary life. His initial posting to Macao in 1582 placed him on the threshold of China, then largely closed to European presence except for tightly controlled enclaves. Ricci’s early years were marked by frustration: the Portuguese enclave of Macao was distant from the centres of Chinese power, and access to the mainland was restricted. Nevertheless, with the support of Valignano and the Macau mission, Ricci and Michele Ruggieri were permitted to enter Zhaoqing in Guangdong in 1583, marking the beginning of a remarkable career that would span nearly three decades (Spence 1985,35-38; HSIA 2012,33-36).

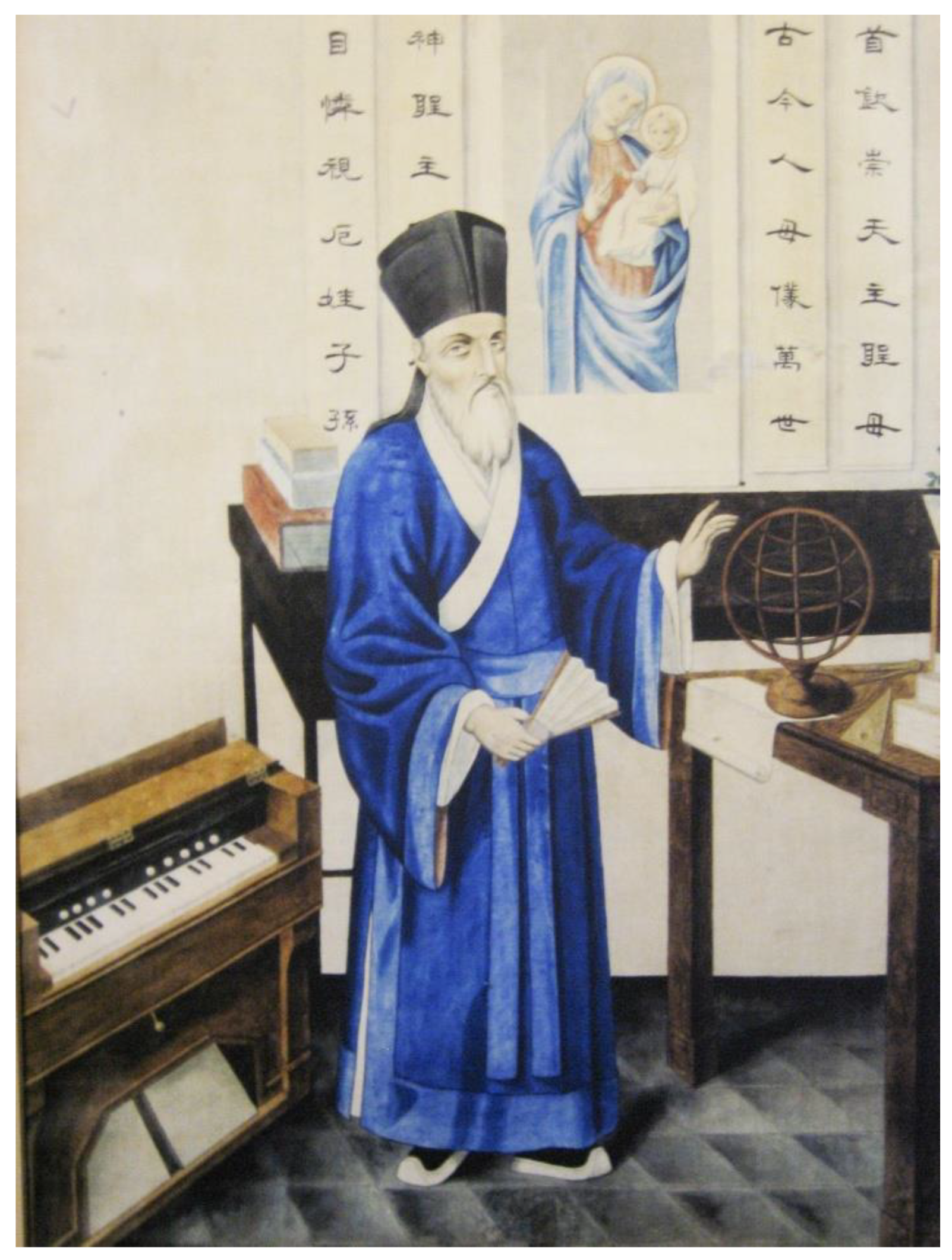

At first, Ricci adopted the garb of a Buddhist monk, believing that a religious identity might elicit tolerance. Yet this decision soon proved counterproductive, as local officials and literati often regarded Buddhist clergy with suspicion, associating them with corruption or social marginality (Gernet 1985, 87–90). Ricci quickly realised that successful integration required him to present himself as a Confucian literatus, a shift that transformed his social position and opened access to circles of power. As Fontana (2011,101-04) notes, Ricci carefully presented himself as a scholar-official rather than a foreign missionary, adapting his dress and manners accordingly. His letters, preserved in the monumental Fonti Ricciane (Elia 1942,55-60), reveal his strategic concern for cultural accommodation. This decision illustrates the broader Jesuit strategy of accommodatio, developed in Japan and India, but applied with particular nuance in China (Rule 1986,42-45; Stanbury 2000,178-80).

Establishing Intellectual Credentials

Ricci’s entry into literati networks depended on more than attire. He devoted himself to the study of the Chinese language and the Confucian canon. Assisted by Chinese tutors, Ricci memorised the Four Books and Five Classics, and within a decade became capable of composing elegant essays in classical Chinese. This remarkable linguistic achievement allowed him not only to preach but also to debate with officials on philosophy, astronomy, and ethics. By presenting himself as a scholar conversant with the revered traditions of China, Ricci established a legitimacy that no European before him had attained (Spence 1985,51-53; Meynard 2015,212-14).

At the same time, Ricci employed his knowledge of European science to captivate Chinese audiences. He introduced mechanical clocks, prisms, and maps as tokens of Western learning, drawing curiosity and admiration. Such instruments were not merely curiosities but pedagogical tools, embodying the precision and rationality that Jesuits sought to associate with Christianity.

As Xu Guangqi observed in a memorial to the emperor in 1606:

“The Western scholar Li Madou is a man of great virtue and learning. He has mastered the classics of our land, and in his conversations he is never arrogant, but always respectful. His explanations of the patterns of heaven and earth are clear and precise, and his instruments surpass anything our artisans can make. He does not seek wealth, but only to share knowledge(Standaert 2019,539).”

As scholars note, these artefacts functioned simultaneously as instruments of science and as rhetorical devices of persuasion (Elman 2005,61-63; Brockey 2007,133-35).

Mobility Across Ming China

Ricci’s career was marked by gradual movement northwards, from the southern provinces to the imperial capital. Each relocation reflected both opportunity and necessity. In Shaozhou and Nanchang, he cultivated friendships with local literati, some of whom—like Li Zhizao and Xu Guangqi—would become crucial converts and collaborators. In Nanchang, Ricci engaged in debates on philosophy and religion, while in Nanjing he encountered prominent officials whose patronage facilitated his eventual move to Beijing (HSIA 2012,97-100).

His 1601 entry into Beijing, sanctioned by the Wanli Emperor, represented the culmination of long years of effort. Ricci and his companions were granted residence in the capital, where they served as court astronomers and presented European gifts, including clocks and maps, that fascinated the emperor and his officials. Although Ricci never secured an imperial audience, his presence in Beijing provided the Jesuits with unprecedented access to the heart of Chinese power (Brockey 2007,221-25; HSIA 2012,133-35).

Works and Writings

Ricci’s literary output was vast and influential. His Tianzhu shiyi (The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven), published in 1603, sought to demonstrate the compatibility of Confucian moral teaching with Christian doctrine, while simultaneously exposing the deficiencies of Buddhism and Daoism. Written in the form of a dialogue, it exemplified Jesuit rhetorical strategy: to frame Christianity as fulfilling rather than overturning Chinese ethical traditions (Mungello 1989,145-48).

His Jiaoyou lun (Treatise on Friendship) drew on Cicero and other classical sources to argue that Christian charity was congruent with Confucian ren (benevolence). This work resonated deeply with literati culture, which valued friendship as a key moral and social category. Ricci’s appropriation of Confucian vocabulary and literary form demonstrates the extent of his accommodation, though scholars debate whether it represented genuine synthesis or strategic translation (Rule 1986,153-56; Meynard 2015,210-12).

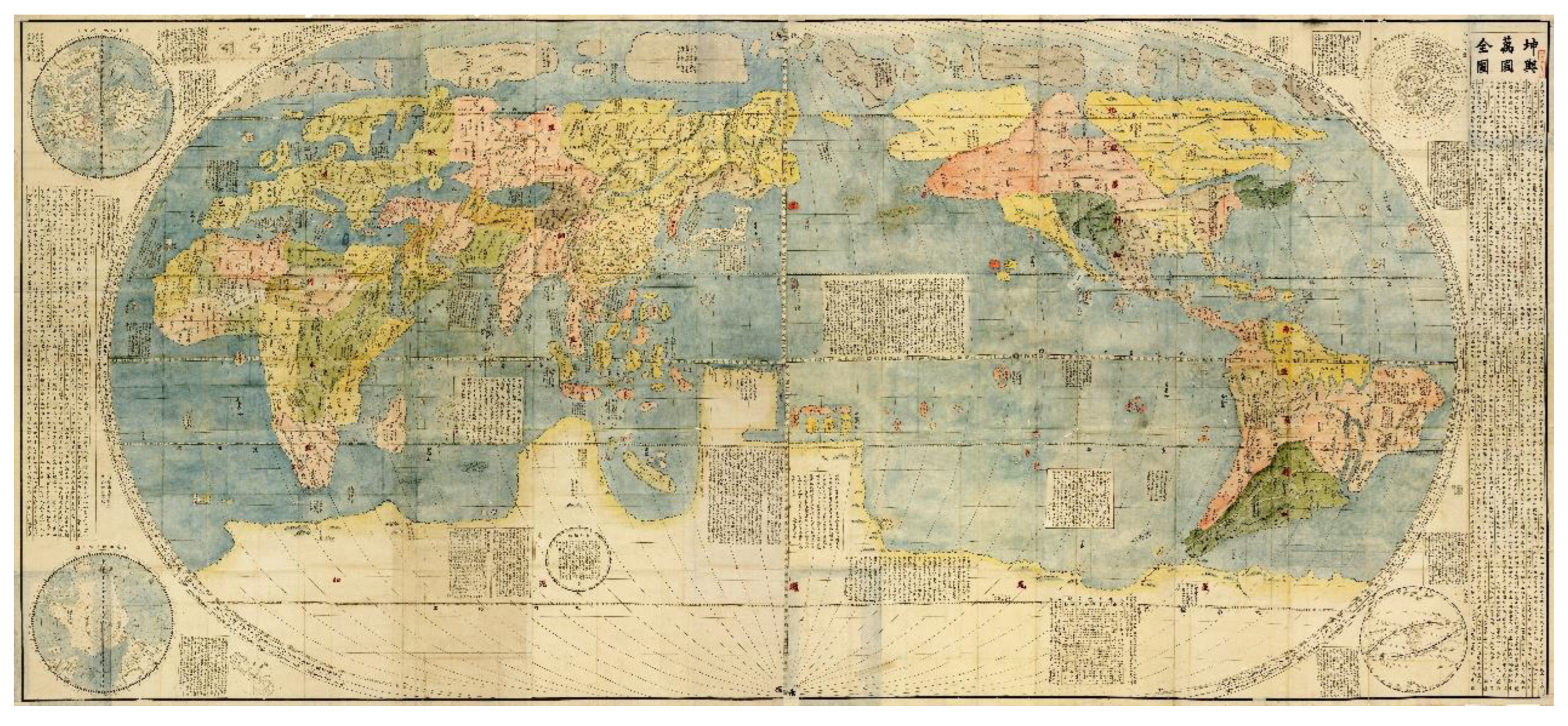

Perhaps most striking were Ricci’s scientific contributions. His collaboration with Xu Guangqi in translating Euclid’s Elements introduced deductive reasoning and axiomatic proof into Chinese mathematical discourse, challenging traditional modes of learning (Elman 2005,85-88). His maps, particularly the Kunyu wanguo quantu (Map of the Ten Thousand Countries), reshaped Chinese geographical imagination by situating China within a global framework, sparking both admiration and anxiety (Spence 1985,141-44; HSIA 2012,199-202).

Building a Circle of Converts

Ricci’s efforts bore fruit in the conversion of prominent Chinese literati. Xu Guangqi, a high-ranking official and polymath, became a Christian in 1603 and later played a central role in translating Western science into Chinese. Li Zhizao and Yang Tingyun, both respected scholars, likewise converted, forming what has been called the “Three Pillars” of early Chinese Christianity (Mungello 2013,101-03). These figures not only defended Christianity in public but also ensured that Ricci’s translations and treatises reached wider audiences. Their involvement underscores the extent to which Ricci’s mission relied on literati collaboration and patronage (Standaert 2019,315-18).

Legacy at Death

When Ricci died in Beijing in 1610, he was honoured by both Jesuits and Chinese officials. The Wanli Emperor granted him burial in the capital—a privilege never before accorded to a foreigner. This symbolic act reflected the unique position Ricci had achieved as a cultural intermediary. His death marked not the end but the beginning of a new phase of Jesuit activity, as his writings and converts ensured the continuation of the mission. Yet his legacy also planted the seeds of future controversy, as debates over rituals and accommodation would erupt in the decades that followed (Gernet and Gernet 1985,141-43; HSIA 2012,215-18).

Assessment of Ricci’s Role

Historians remain divided in their assessment of Ricci. Some, like Jonathan Spence, have celebrated him as a genius of cultural memory and translation, while others, like Jacques Gernet, emphasise the asymmetries of power and the ultimate incompatibility of Christianity and Confucianism. More recent scholarship situates Ricci within the broader dynamics of global intellectual history, viewing him not as a solitary genius but as part of the Jesuit network that stretched from Rome to Goa, Macao, and Beijing (Elman 2005,61-63; Mungello 2013,115-18).

Ricci’s life in China thus illustrates the multiple dimensions of cultural encounter: linguistic mastery, scientific exchange, philosophical debate, and religious controversy. His activities established the foundations of a Sino–Western dialogue that would reverberate across centuries, shaping both Chinese intellectual life and European perceptions of the Middle Kingdom.

III. Matteo Ricci’s Cultural Adaptation: From “The Other” to “Western Confucian”

The Jesuit Principle of Accommodatio

The Society of Jesus developed its missionary strategy around the principle of accommodatio, a doctrine articulated most clearly by Alessandro Valignano, the Visitor to Asian missions. In his Il Cerimoniale per i Missionari del Giappone (1581), Valignano insisted that Europeans must adopt local customs and languages if they hoped to succeed in non-Christian lands (Rule 1986, 39–41). Whereas earlier missionaries had often demanded radical cultural separation, Jesuits were encouraged to learn local scripts, wear indigenous attire, and present Christianity as compatible with existing traditions. Ricci embodied this strategy in China, recognising that credibility among the Confucian literati required more than the preaching of doctrine: it demanded full participation in the social and intellectual codes of the elite.

The notion of accommodatio was not without controversy within the Jesuit order. Some critics feared that excessive adaptation risked diluting the faith or sowing confusion. Yet Ricci, following Valignano’s guidance, believed that the Gospel could only be heard if expressed through the idioms of Confucian morality and cosmology (Mungello 1989,52-55). In this respect, Ricci’s project mirrored the efforts of Jesuits in India, such as Roberto de Nobili, who adopted the dress and customs of Brahmins in Madurai. Both cases reveal how Jesuit missionaries experimented with cultural translation, negotiating the tension between orthodoxy and flexibility (Standaert 2019,175-77).As Ross (1994,73-75) and Boxer (1951,115-19) note, Jesuit experiments in Japan and India demonstrated the diversity of accommodatio practices. Lach (2010,15-18) reminds us that such strategies unfolded within a Europe increasingly fascinated by Asia’s intellectual and cultural heritage.

Language Mastery and Intellectual Integration

Perhaps Ricci’s most extraordinary accomplishment was his mastery of the Chinese written language. Early missionaries had relied on interpreters or produced rudimentary phrasebooks, but Ricci undertook a systematic study of classical Chinese under the guidance of literati tutors. He immersed himself in the Analects and Mencius, memorised large sections of the Confucian canon, and eventually composed essays, treatises, and dialogues in a style that contemporaries judged to be refined and persuasive (Spence 1985,51-54).

Language was more than a practical tool; it was a medium of intellectual legitimacy. By writing in classical Chinese, Ricci signalled respect for Chinese civilisation and demonstrated his claim to participate in literati discourse. This effort won him the admiration of figures such as Xu Guangqi and Li Zhizao, who saw in Ricci not a foreign intruder but a fellow scholar. As Meynard (2015,210-12)observes, Ricci’s use of Confucian terminology—particularly terms like li (principle), qi (material force), and ren (benevolence)—functioned as a “hermeneutic bridge” between Christian theology and Chinese philosophy.

Ricci’s engagement with the Chinese lexicon also contributed to the evolution of scientific and religious vocabulary, as Zhao (2024,55-60) demonstrates. Recent computational text-reuse analysis further quantifies Ricci’s reliance on Confucian classics, confirming that his accommodation was not merely rhetorical but deeply textual (McManus et al. 2025,7-10).

At the same time, Ricci’s linguistic adaptation was not without distortion. To render Christian concepts intelligible, he borrowed Confucian or Daoist terms, sometimes stretching their meanings. For instance, he translated “God” as Tianzhu (Lord of Heaven), a term that resonated with Chinese cosmology but risked conflating the Christian Creator with the impersonal Tian of Confucian thought (Spence 1985,119-21). This semantic negotiation illustrates both the creativity and the ambiguity of his project.

Rituals, Filial Piety, and the Seeds of Controversy

Ricci’s interpretation of Chinese rituals illustrates the subtle balancing act of accommodation. He argued that ancestral rites were civic ceremonies expressing filial piety rather than acts of religious worship. On this basis, he permitted Chinese Christians to continue performing them, provided they were understood as cultural rather than theological practices (Ricci 1985,123-23). This position reassured Confucian literati that Christianity did not undermine filial obligations, which were central to the moral fabric of society.

Yet Ricci’s stance foreshadowed later disputes. Jacques Gernet (1985,141-43)argues that Jesuit minimisation of the religious dimensions of ritual misrepresented Confucian cosmology. The Vatican would later condemn such practices, sparking the infamous Chinese Rites Controversy that divided missionaries and alienated Chinese converts. Scholars have shown that this interpretation planted the seeds of the later Chinese Rites Controversy (Cummins 1993,131-34). More recent research frames these tensions as part of a broader pattern of conflict and integration in late Ming encounters with Western missionaries (Zhang and Mao 2024). What Ricci saw as pragmatic adaptation thus became the source of one of the greatest conflicts in early modern global Christianity.

Self-Presentation as “Western Confucian”

Beyond clothing and rituals, Ricci cultivated an identity as a “Western Confucian.” He styled himself not as a prophet of a foreign creed but as a scholar committed to moral cultivation, textual study, and rational inquiry. In some writings, he even compared himself to the hermit-scholars of Chinese tradition, emphasising his detachment from worldly ambition and his pursuit of wisdom (Spence 1985,63-64). This rhetorical strategy aligned him with literati ideals of moral integrity and reinforced his credibility as a teacher.

At the same time, Ricci consistently emphasised the superiority of Christian revelation. His persona as a Confucian scholar was not intended to dissolve doctrinal boundaries but to create a space in which Christian truths could be heard. Rule (1986,102-05) observes that Ricci’s cultural adaptation was instrumental: it provided a pathway to dialogue, but one whose ultimate aim was conversion. The tension between openness and exclusivity thus defined his mission.

Scholarly Assessments

Historians remain divided on how to evaluate Ricci’s adaptation. Some, like Jonathan Spence, emphasise his brilliance as a cultural translator who created new possibilities of dialogue. Others, like Jacques Gernet, underscore the asymmetries of power and the inherent incompatibility between Confucian cosmology and Christian theology. More recent work situates Ricci within the framework of global intellectual history, viewing him as one node in a network of Jesuit strategies across Asia (Elman 2005,61-63; Mungello 2013,115-18).

Meynard (2015,211-14) suggests that Ricci’s writings reveal both genuine appreciation for Confucian ethics and calculated rhetorical manoeuvres designed to facilitate conversion. Standaert (2019,362-65) highlights how his interpretation of rituals inadvertently triggered long-term disputes within the Church. New work has also examined Ricci’s intellectual engagement with the Taizhou school, suggesting further dimensions of convergence and conflict (Xie 2023).These divergent assessments underscore the ambivalence of Ricci’s cultural identity: simultaneously “the other” and “one of us,” both foreign missionary and Confucian scholar.

IV. The Clash: Syncretising Confucianism and Christianity

Accommodation Reaches Its Limits

While Ricci’s adaptation strategy enabled unprecedented dialogue with the Chinese literati, it inevitably confronted limits when core theological doctrines of Christianity clashed with Confucian cosmology. The principle of accommodatio worked best in areas of moral ethics or scientific knowledge, where analogies could be drawn. But once questions of metaphysics, creation, and ultimate truth were raised, Ricci’s synthesis revealed its fragility. His writings, especially The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven (Tianzhu shiyi), exemplify both the possibilities of intellectual convergence and the tensions of theological exclusivity (Mungello 1989,145-50; Meynard 2015,67-70).

“The Lord of Heaven is the sovereign master of heaven and earth, the creator of all things. He has neither beginning nor end, and from Him all things derive their existence. Human beings should revere Him, serve Him, and keep Him ever in mind, for He is the origin of our lives and the final destiny to which we return(Ricci 1985,59-60).”

The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven (1603)

Ricci’s most ambitious theological work, The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven, was written in classical Chinese in the form of a dialogue between a Western scholar and a Chinese literatus. Ricci argued that the Confucian concept of Tian (Heaven) was equivalent to the Christian Deus or Tianzhu (Lord of Heaven). By aligning Confucian reverence for Heaven with Christian monotheism, Ricci sought to establish common ground. He insisted that ancient Confucians had recognised a supreme, personal deity, but that this knowledge had been obscured by later Neo-Confucian speculation (Ricci 1985,119-21).

For sympathetic literati like Xu Guangqi, Ricci’s argument was persuasive: Christianity could be interpreted as a restoration of the original moral clarity of Confucius and Mencius. However, for others, Ricci’s reading seemed a selective reinterpretation of Confucian texts to fit Christian categories. Jacques Gernet (1985,151-54) contends that Ricci imposed alien theological concepts upon Confucian cosmology, thus distorting its meaning. Peterson (2010,810-15) further argues that Ricci’s reading was shaped by Thomist categories, which limited his ability to appreciate the immanent dimensions of Confucian metaphysics. Similarly, De Bary (2009,42-45) emphasises that Ricci’s attempt to identify Tian with a personal creator was a radical departure from mainstream Neo-Confucian thought.This criticism underscores the asymmetry of dialogue: Ricci was less interested in mutual synthesis than in demonstrating that Confucianism contained seeds of Christian truth.

The Treatise on Friendship

Ricci’s Jiaoyou lun (Treatise on Friendship), written between 1595 and 1598, illustrates another attempt at synthesis.

“Among the many things that are valued in human life, friendship is the most esteemed. For friendship alone enables us to complete the imperfections of our nature, and to enlarge the scope of our virtue. A true friend is like another self, sharing joys and sorrows alike, and never abandoning one in times of adversity(Ricci 2009,21).”

Drawing on Cicero and classical Christian sources, Ricci argued that genuine friendship is grounded in virtue and truth. He compared this to Confucian notions of ren (benevolence) and loyalty, thereby creating a bridge between the moral discourses of East and West (Spence 1985,95-97).

The treatise appealed to literati culture, where friendship was an esteemed value and often celebrated in poetry and essays. Ricci’s classical Chinese style won admiration, and the text circulated widely. Yet here again, scholars differ in interpretation. Paul Rule (Rule 1986,153-56) regards the treatise as a brilliant example of Jesuit adaptation, while Thierry Meynard(2015,212-15) warns against overestimating its syncretism: beneath the surface harmony, Ricci subtly redirected Confucian ethics towards Christian charity (caritas), thus redefining the moral foundation.

Polemics Against Buddhism and Daoism

Ricci’s accommodation of Confucianism was paralleled by a sharp rejection of Buddhism and Daoism. As Tang (2016,88-92) notes, Ricci’s rejection of Buddhism and Daoism was framed not only in theological terms but also as a strategy to align Christianity with the ruling Confucian ideology.In debates with monks such as Sanhuai, Ricci dismissed Buddhist metaphysics as nihilistic and socially harmful. Jesuit accounts portray Ricci as decisively defeating Buddhist interlocutors through rational disputation (Hsia 2012,118-21). Yet modern historians urge caution: these sources reflect missionary triumphalism and cannot be taken as neutral records. In fact, Buddhist critiques of Christianity likely carried more weight than Jesuit writings admitted(Gernet 1985).

Ricci’s rejection of Buddhism stemmed partly from strategic concerns. By aligning Christianity with Confucianism and against Buddhism, Ricci sought to embed his faith within the ruling ideology of the literati. In this sense, his polemics were less about genuine philosophical engagement than about political positioning. This tactic, however, reinforced antagonism between Christian converts and Buddhist communities, planting seeds of later tension.

Toward a “Christian Confucianism”?

Some scholars have described Ricci’s project as creating a hybrid “Christian Confucianism.” By appropriating Confucian ethical language, dressing as a scholar, and interpreting rituals in civic rather than religious terms, Ricci fashioned a discourse that seemed to merge elements of both traditions. Jonathan Spence (1985,97-99) portrays Ricci as a cultural genius who constructed a “memory palace” in which Western and Chinese categories coexisted.

Yet other scholars caution against exaggerating the degree of synthesis. David Mungello (1989,155-59) argues that Ricci’s adaptation remained strategic: Christianity was always presented as the fulfilment of Confucianism, never as its equal. Nicolas Standaert (2019,362-65) highlights that Ricci’s interpretation of rituals, while pragmatic, was ultimately rejected by the papacy, demonstrating the limits of syncretism. Cummins (1993,131-34) underscores that Ricci’s flexible interpretation of rituals opened the way for internal Jesuit disputes. More recently, Zhang and Mao (2024) situate Ricci’s hybrid discourse within the larger dynamics of religious negotiation and state ideology in late Ming China.In this view, Ricci’s so-called Christian Confucianism was less a stable hybrid than a temporary experiment shaped by historical contingencies.

Seeds of the Rites Controversy

The theological ambiguities in Ricci’s writings foreshadowed the later Chinese Rites Controversy of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Jesuits continued to defend the legitimacy of Confucian rituals as civic practices, while rival orders, particularly the Dominicans and Franciscans, denounced them as idolatrous. The papacy ultimately sided with the latter, condemning Jesuit accommodation. Hu (2023)shows that Ricci’s cautious accommodation became a contested legacy, dividing later Jesuit generations. Mungello (1994,95-98) situates the controversy within broader debates about authority and orthodoxy in early modern Catholicism. In retrospect, Ricci’s strategy appears both visionary and precarious: it opened space for dialogue but created doctrinal ambiguities that the Church could not tolerate (Hsia 2012,215-18).

Thus, Ricci’s attempt to synthesise Confucianism and Christianity reveals the paradox of cross-cultural engagement. His writings demonstrated remarkable intellectual empathy, yet they also exposed the boundaries beyond which neither Confucian orthodoxy nor Catholic dogma could compromise. The clash was not simply between East and West but between competing visions of universality—Confucian moral order and Christian salvation.

V. Communication and Dialogue: Matteo Ricci’s Role as a Cultural Bridge

Mathematics and Scientific Translation

Among Ricci’s most enduring contributions was his translation work in mathematics. In 1607, Ricci collaborated with Xu Guangqi to translate the first six books of Euclid’s Elements. This translation introduced to Chinese readers not just geometrical propositions but a method of reasoning based on axioms, postulates, and deductive proofs. For Chinese literati trained in textual commentary and analogical reasoning, Euclidean demonstration represented a strikingly different epistemology (Elman 2005,85-88).

The translation was highly influential among members of the shixue (practical learning) movement, who sought alternatives to what they saw as sterile Neo-Confucian scholasticism. Xu Guangqi himself praised the clarity and rigor of Euclidean geometry, linking it to moral cultivation and governance. Ricci’s work thus catalysed a rethinking of knowledge practices within Ming intellectual life. Scholars such as Elman(2005,92-95) argue that the encounter with Jesuit science set the stage for later transformations in Qing mathematics and astronomy.(Lach 2010; Raj 2007)This translational project aligns with the broader Jesuit networks of global knowledge circulation (Lach 2010; Raj 2007).

Yet the translation also raises questions about cultural translation. Key terms such as “point” (Dian in Chinese) and “line” (Xian in Chinese) were rendered using Chinese characters that carried different semantic fields. Did Chinese readers truly grasp Euclidean abstraction, or did they interpret it through existing frameworks of correlative cosmology? Meynard (2015,214-16) warns against assuming that Ricci’s translation produced a simple transfer of ideas. Instead, it generated a hybrid discourse in which European mathematical logic was reinterpreted within Chinese categories.

Geography and Cartography

Ricci’s Kunyu wanguo quantu (Map of the Ten Thousand Countries of the Earth), first produced in 1602, was another landmark of cross-cultural knowledge. The map presented the world as a globe, with continents accurately proportioned, and placed China not at the centre but as one nation among many. For Chinese audiences accustomed to Sinocentric maps, this representation was revolutionary. It revealed the existence of distant continents such as Europe, Africa, and the Americas, expanding horizons beyond traditional geography (Spence 1985,141-44).

Figure 2.

Kunyu wanguo quantu (Map of the Ten Thousand Countries of the Earth), coloured edition, c. 1604. Copy of Matteo Ricci’s 1602 map with Japanese katakana transliterations of Chinese place names. Unattributed. Image Database of the Kano Collection, Tohoku University Library, Japan.

Figure 2.

Kunyu wanguo quantu (Map of the Ten Thousand Countries of the Earth), coloured edition, c. 1604. Copy of Matteo Ricci’s 1602 map with Japanese katakana transliterations of Chinese place names. Unattributed. Image Database of the Kano Collection, Tohoku University Library, Japan.

The reception of the map was complex. Some literati were fascinated by the scope of the world it revealed, while others were unsettled by its challenge to the established worldview. The map circulated widely, copied by Chinese engravers and incorporated into local gazetteers, testifying to its impact (Hsia 2012,199-202). Yet its significance went beyond geography: it symbolised a new epistemology in which empirical observation and measurement displaced inherited tradition.

European observers also learned from Ricci’s maps. His reports informed European cartographers about Chinese geography and administrative divisions, helping to correct misconceptions. Thus, Ricci’s cartography operated in both directions: bringing the world to China and China to the world.

“The literati of this kingdom are very eager to learn about the things of Europe, especially concerning mathematics, astronomy, and geography. They are astonished at the precision of our instruments, and they receive us with great honour when we present them with such knowledge. Yet, concerning matters of religion, they are suspicious, for they fear all that might disturb their ancient customs(Ricci 1953,215-216).”

Language, Literature, and Missionary Linguistics

Ricci’s linguistic contributions extended beyond translation of classical texts. He participated in the development of early Chinese–Portuguese lexicons, laying the groundwork for missionary linguistics (Standaert 2019,421-24). He composed dialogues, essays, and moral treatises in elegant classical Chinese, such as the Jiaoyou lun, which circulated among literati networks. His facility with language allowed him to insert Christian ideas into Chinese literary genres, blurring the line between foreign doctrine and native discourse. Ricci’s writings circulated in literati circles, where they were read not only as theological works but also as elegant literary essays (Chow 2007,155-58). His cultural strategy also included music and art: Jesuit polyphony, imported instruments, and devotional paintings fascinated Chinese audiences, functioning as aesthetic demonstrations of European sophistication (Bailey 1999,45-48; Feng 2024).

Music and art also played a role. Ricci introduced Western polyphony, played instruments such as the clavichord, and displayed European religious paintings. These artefacts fascinated Chinese audiences, offering glimpses of alternative aesthetic traditions. As Brockey (2007,214-17) notes, Ricci’s use of material culture was not incidental: objects carried symbolic power, demonstrating the sophistication of Western civilisation and lending credibility to its religion.

Ambivalence and Boundaries

Despite these achievements, Ricci’s role as a cultural bridge was marked by ambivalence. His accommodation enabled genuine exchanges, yet his rejection of Buddhism and insistence on Christian exclusivity revealed the boundaries of dialogue. Paul Rule (1986,201-03) underscores that Ricci never abandoned the aim of conversion, even as he adopted Confucian forms. Dialogue, therefore, was instrumental rather than open-ended. Later Jesuit figures such as Schall von Bell and Buglio continued to wrestle with these tensions, reflecting what Brockey (Brockey 2014,210-13) calls the “fractured legacy” of Ricci’s accommodation strategy.

Ricci’s project demonstrates the double-edged nature of cultural translation. On one hand, it produced new hybrid knowledge and reshaped intellectual landscapes. On the other, it exposed tensions between persuasion and coercion, dialogue and dogma. His legacy is thus best understood not as seamless harmony but as a historical experiment fraught with contradictions.

VI. Conclusion

Matteo Ricci’s career in late Ming China remains one of the most striking examples of cross-cultural encounter in the early modern world. His mastery of language, adoption of literati customs, and introduction of Western science made him a unique mediator between civilisations. Through works on mathematics, cartography, ethics, and theology, he reshaped Chinese intellectual life and simultaneously furnished Europeans with new understandings of China (Elman 2005,85-88; Hsia 2012,215-18). Later Jesuit missionaries continued to grapple with the tensions inherent in Ricci’s strategy, reflecting what Brockey (2014,210-13) has termed its “fractured legacy.”

Yet Ricci’s adaptation strategy also revealed profound limits. His insistence on Christian orthodoxy, his critique of Neo-Confucian metaphysics, and his hostility toward Buddhism prevented genuine synthesis. What he offered was not a neutral dialogue but a project of translation directed toward conversion. The apparent convergence of Confucianism and Christianity masked deeper incompatibilities that would erupt in the Rites Controversy, when the Vatican condemned precisely the practices Ricci had defended (Gernet 1985,141-43; Standaert 2019,362-65). As Mungello (1994,95-98) shows, the debates surrounding Chinese rituals were not merely local disputes but part of broader struggles over authority and orthodoxy in early modern Catholicism.

Ricci’s legacy must therefore be understood with nuance. He was not simply a cultural hero or a manipulative proselytiser, but a historical actor navigating the complexities of intercultural communication. His writings and activities testify to the possibilities of empathy, curiosity, and intellectual exchange, while also reminding us of the boundaries imposed by doctrinal exclusivity and cultural asymmetry. Hu (2023) emphasises that Ricci’s legacy was reinterpreted by later Chinese converts and Jesuit successors alike, underscoring its contested and dynamic nature.

From the perspective of global intellectual history, Ricci exemplifies the dynamics of cultural translation: selective borrowing, strategic adaptation, and contested interpretation. His work demonstrates that dialogue between traditions is never frictionless but always shaped by power, faith, and interpretation. In Subrahmanyam’s (2011,49-52) framework of “connected histories,” Ricci emerges as a paradigmatic node linking disparate intellectual worlds, exemplifying both the promise and the instability of early modern global encounters. In this sense, Ricci’s legacy endures as a reminder of both the potential and the fragility of cross-cultural encounters.