1. Introduction

Designing multimedia technology, such as augmented reality (AR), for inclusive education, ensuring that digital learning tools are accessible and usable by individuals with diverse abilities, presents a complex and urgent challenge [

1,

2]. Educational technologies, particularly immersive multimedia systems, must accommodate a wide range of user needs—including visual, auditory, motor, and cognitive—without compromising either pedagogical efficacy or user experience [

3]. Traditional, linear development methodologies often prove inadequate for this task, as they typically lack the embedded mechanisms for continuous user feedback and iterative refinement necessary to address the fluid and nuanced nature of accessibility requirements. In contrast, Design-Based Research (DBR) and Agile Scrum (AS) are two prominent methodologies celebrated for their user-centered, iterative frameworks [

4]. This paper explores a novel synthesis of these two approaches to facilitate the design and development of inclusive educational technology, as exemplified by our project, creating an accessible AR learning content authoring tool.

Design-Based Research (DBR) is an educational research paradigm focused on addressing authentic problems through systematic, iterative cycles of design, implementation, and analysis [

5,

6]. Rooted in pragmatic inquiry, DBR generates both a functional intervention and a set of design principles or theoretical knowledge grounded in real-world contexts. Its cyclical nature—involving continuous analysis, design, and evaluation—relies on close collaboration with practitioners and a blend of qualitative and quantitative methods to ensure the solution is both effective and theoretically sound [

7,

8]. However, DBR is also resource-intensive and challenging. Its iterations can be time-consuming and unpredictable, sometimes exceeding available time or funding [

9]. Researchers must also be cautious of potential biases resulting from their deep involvement in the design process, which can compromise objective analysis [

10,

11]. Furthermore, because DBR studies are often context-specific, ensuring that findings generalize to other settings is an ongoing concern [

12]. These challenges suggest the need for careful planning and perhaps complementary approaches to keep projects on track.

Complementing this, AS is a widely adopted software project management framework built on an empirical process control model that emphasizes iterative development, frequent delivery of working software, and continuous stakeholder feedback [

13]. Scrum organizes teams into time-boxed sprints, governed by specific roles (e.g., Product Owner, Scrum Master) and ceremonies (e.g., daily stand-ups, sprint reviews) to enable rapid adaptation to change [

14,

15]. For educational software, Scrum's focus on demonstrable, working prototypes and responsiveness to emerging user needs can effectively align the engineering process with evolving pedagogical requirements.

Despite their distinct origins—DBR from educational research and AS from software engineering—the two methodologies share a fundamental commitment to iterative design and continuous stakeholder involvement [

4,

16]. This common ground suggests a powerful synergy: DBR provides the rigorous research framework to ensure the educational intervention contributes new knowledge and is contextually valid, while AS offers the structured development framework to efficiently manage the engineering process and deliver functional software [

16]. However, integrating these frameworks is not without its challenges and raises critical questions for practitioners and researchers: How can the data collection and analysis activities of a DBR cycle be effectively integrated into Scrum's sprint-based cadence? What mechanisms are needed to sustain a sharp focus on accessibility and inclusion within the rapid iterations of agile development? And how should the roles and responsibilities of researchers, developers, and end-users be coordinated in this hybrid process?

This paper addresses these questions by documenting our experience in the Accessible AR Authoring Tool Project, where we explicitly integrated DBR and AS to design an inclusive learning tool. The project's central goal was to empower non-technical instructors, including those with disabilities, to create engaging AR learning experiences. Over multiple DBR cycles, we collaborated with instructors and students to identify accessibility needs, implement specific features, and evaluate the tool in authentic educational settings. A key contribution is the proposal of a practical, hybrid methodology that integrates DBR and AS to systematically address accessibility and inclusivity in the design of educational multimedia systems, demonstrating how this approach can bridge research rigor with development efficiency. Throughout this process, we meticulously documented the best practices that emerged and the obstacles we encountered.

In the following sections, we first establish the methodological foundations of this work by providing an overview of DBR and AS. We then review the related literature on hybrid methodologies, positioning our study as a novel approach specifically tailored to inclusive multimedia design. We proceed to detail our methodological integration of DBR and AS in the AR project, including our innovative use of accessibility-focused user stories. Next, we present the best practices and challenges distilled from our experience, offering concrete strategies for mitigation. We conclude with a discussion of our findings in relation to existing literature and provide actionable recommendations for researchers and developers in the fields of HCI and accessibility.

2. Background: Methodological Foundations

2.1. Design-Based Research (DBR) for Multimedia Systems

Design-Based Research (DBR) emerged in the early 2000s as a powerful methodology for bridging the gap between controlled laboratory studies and the complexities of real-world educational contexts [

7]. Instead of isolating variables, DBR engages directly with authentic learning environments to generate both practical solutions and theoretical insights [

6,

17]. A classic DBR project involves multiple iterative cycles: researchers identify a problem in practice, design an intervention (such as an educational game or an AR authoring tool), implement it in collaboration with practitioners, and systematically collect data to refine the design [

8,

18]. Through these cycles, DBR generates design principles and localized theories about learning that are grounded in empirical evidence.

Key features of DBR that are particularly relevant to the development of multimedia systems include [

5,

7,

19]:

Pragmatic Collaboration: Researchers and practitioners (e.g., instructors, students) work together in all phases, ensuring that the intervention is not only theoretically sound but also relevant and feasible in a real-world context.

Iterative Refinement: The design of a multimedia artifact is expected to evolve. Early prototypes are treated as empirical tests to learn from, not as final products.

Mixed-Method Evaluation: Qualitative observations, interviews, and quantitative measures (e.g., usage analytics, usability data) are combined to evaluate the effectiveness and user experience of each iteration.

Theory Building: DBR seeks to contribute new theories or guidelines for the field. For instance, a decade of DBR has yielded substantive design principles for creating technology-enhanced learning environments.

However, DBR is also resource-intensive and challenging. Its iterative cycles can be time-consuming and unpredictable, sometimes exceeding available time or funding [

9,

10,

11,

20]. These challenges underscore the importance of meticulous planning and complementary strategies to ensure projects stay on track.

2.2. Agile Scrum for Educational Software Development

Agile development methodologies, and Scrum in particular, emerged in the software industry as a response to heavyweight, linear processes [

13,

21]. Scrum is built around a few core ideas that are highly applicable to the fast-paced development of immersive multimedia systems [

22,

23,

24,

25]:

Develop in short, fixed-length cycles (sprints) with a potentially shippable product increment at each sprint’s end. This allows for frequent delivery and testing of multimodal features.

Prioritize a backlog of features (user stories) that can be re-ordered as needs change. The Product Owner represents stakeholders to prioritize these features, ensuring that development effort is focused on the most critical ones.

Emphasize team communication with daily stand-up meetings and close collaboration. Roles are defined to support this, such as the Scrum Master who facilitates the process and a development team that self-organizes to meet sprint goals.

Embrace change: If new requirements or user feedback emerge, they can be incorporated in the next sprint rather than waiting for a long development phase to conclude.

In the context of educational software development, Agile methods have been increasingly adopted to meet the evolving requirements of teachers and learners [

13,

26]. They offer the flexibility and adaptability that are valuable when the target context may shift, or when initial requirements for a complex multimedia system are not fully clear [

25]. For our purposes, Scrum's most relevant aspect was its insistence on continuous user feedback and incremental delivery. This created a built-in mechanism for iterative improvement that directly parallels the cycles of DBR, making it an ideal partner for our research goals. We were aware that common challenges of using Scrum include difficulties with strict project timelines, budget constraints, and the need for a highly cohesive team [

27,

28]. However, by proactively planning for these issues and leveraging the inherent flexibility of our hybrid approach, we were able to mitigate them, ensuring the Scrum framework's benefits were realized without its typical drawbacks [

29].

3. A Hybrid DBR-Scrum Framework for Inclusive Multimedia Design

This study employed a hybrid methodological framework, integrating DBR for the overarching research design and evaluation with AS for software development and project management. This integration was motivated by the complementary affordances of the two approaches: DBR provides an iterative, context-sensitive research paradigm for addressing authentic educational problems [

6,

8], while AS enables adaptive, time-boxed cycles for managing software development complexity and ensuring responsiveness to evolving user needs [

33]. The primary goal was to design and implement an open-source AR learning authoring tool that is accessible to instructors with diverse abilities and technical backgrounds. The project was situated within higher education institutions, which provided a diverse user base and ecological validity for the interventions.

The rationale for integrating DBR and AS lies in their shared reliance on iterative refinement, stakeholder engagement, and responsiveness to feedback. Previous research has demonstrated that Agile practices can strengthen the practical implementation of DBR by aligning development cycles with research phases [

31,

32]. Conversely, DBR’s theoretical grounding prevents Agile teams from prioritizing speed over educational integrity [

34]. Our methodological approach was structured around Plomp’s three high-level DBR phases [

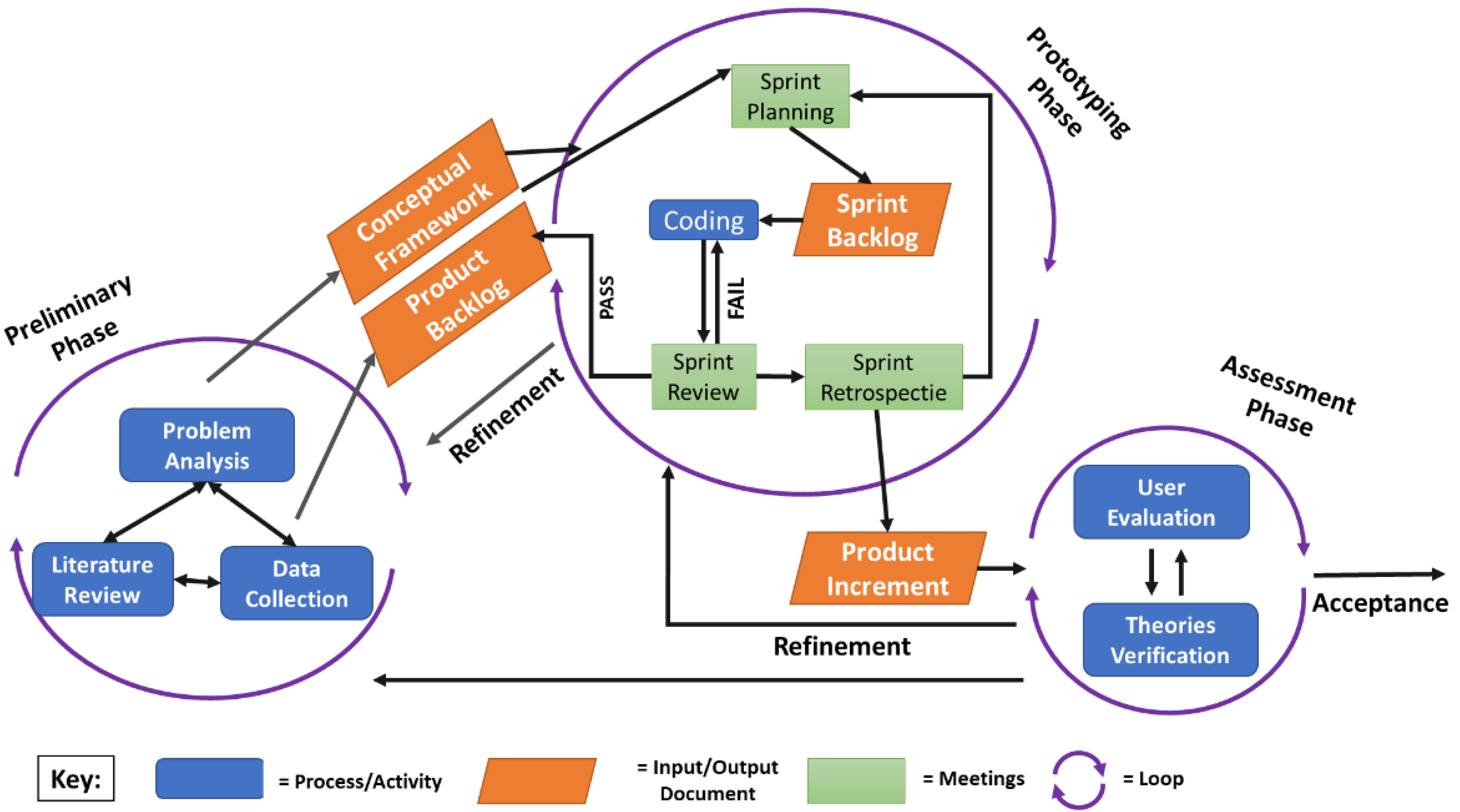

8]—preliminary, prototyping, and assessment phases—dynamically aligned with a series of two-week Scrum sprints. This integration is visually represented in

Figure 1, which illustrates how DBR’s research-oriented cycles informed and were operationalized through Scrum’s development-oriented iterations.

3.1. Phase 1: Preliminary Research & Analysis

The first phase was dedicated to identifying the authentic design problem and establishing foundational requirements. In line with DBR’s emphasis on grounding design in real-world challenges [

7], we conducted a literature review on AR in education, AR authoring tools, accessibility evaluation of AR, and captioning strategy in the AR environment [

1,

35]. We also conducted a document analysis of the Accessibility Guidelines, specifically the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) [

36] and the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) [

37], which provided normative and pedagogical benchmarks for inclusivity.

This literature review was complemented by empirical context analysis through semi-structured interviews and surveys with potential users, including instructors with visual and hearing impairments. This multi-method approach is consistent with best practices in DBR, which requires triangulation of theoretical and contextual insights to frame the design problem [

19,

38]. The analysis revealed a critical gap: existing AR authoring tools were largely inaccessible, lacking essential features such as synchronized captioning and multimodal navigation [

39].

From these insights, we defined a conceptual framework for the inclusive AR authoring tool, grounded in UDL and WCAG. A product vision and an initial backlog of prioritized features were derived and expressed as user stories to maintain alignment with Scrum practices [

40].

3.1.1. The Role of Accessibility-Focused User Stories

A cornerstone of our methodology was prioritizing accessibility-focused user stories. Prior work in inclusive design emphasizes the importance of embedding accessibility requirements from the outset rather than treating them as add-ons [

41,

42]. To ensure this, we developed detailed user personas (e.g., a blind instructor, a deaf student, a novice teacher) based on the preliminary research. These personas informed user stories written in the canonical format (“As a [user], I want [feature], so that [benefit]”) [

40,

43], which explicitly foregrounded accessibility needs.

For example:

As an instructor with visual impairment, I want the interface to be fully voice-input navigable, so that I can create AR content independently without sight.

As a deaf student, I want synchronized captions for all audio in AR experiences, so that I can access equivalent information.

As a novice teacher with limited technical experience, I want guided templates, so that I can author AR content without coding skills.

Each user story specified the user, the accessibility requirement, and its intended benefit, serving simultaneously as design guidance and acceptance criteria. By giving these stories high priority in the product backlog, accessibility became a non-negotiable design principle integrated into the earliest development sprints [

44].

3.2. Phase 2: Iterative Development & Formative Evaluation

The second phase comprised multiple DBR micro-cycles, executed through two-week Scrum sprints. The cross-functional team consisted of software developers (Scrum Development Team), educational researchers (one of whom acted as Product Owner to represent user needs), and a Scrum Master. In alignment with DBR’s collaborative ethos [

5,

45], practitioner collaborators, such as users with disabilities, were engaged as critical stakeholders throughout.

During each sprint, developers implemented prioritized user stories, while daily stand-ups were adapted to incorporate both technical progress and reflections on user feedback. This ensured that research considerations informed development on a daily basis. A kanban board was used to manage both technical and research tasks, consistent with recommendations for hybrid Agile–research projects [

4].

At the conclusion of each sprint, a Sprint Review presented a working increment to end-users for immediate feedback. This aligns with DBR’s emphasis on testing conjectures in authentic settings [

46,

47]. For example, an early prototype revealed a major flaw in the voice-input navigation system when tested by a blind instructor; this insight was immediately integrated into the subsequent sprint backlog. Sprint Retrospectives were expanded beyond Scrum’s process focus to also address DBR’s reflective stage, prompting the team to refine both research questions and data collection strategies.

After a cluster of sprints, formative evaluations were conducted through usability surveys, observational studies, and semi-structured interviews. Findings informed the revision of design principles and the generation of new accessibility-focused user stories, closing the DBR micro-cycle.

3.3. Phase 3: Summative Evaluation

The final phase involved a summative evaluation to assess the effectiveness and inclusivity of the final intervention. Following recommendations for evaluating DBR outcomes [

6], we deployed the tool in a stakeholder workshop where students and instructors created and engaged with AR materials. Data were collected on accessibility outcomes (e.g., compliance with WCAG standards), learning outcomes (e.g., perceived ease of use, content comprehension), and user satisfaction. This triangulated evidence provided a robust assessment of the intervention’s viability and effectiveness in real-world contexts.

All phases were systematically documented to ensure transparency and replicability, in accordance with methodological standards in DBR [

19]. The findings from these evaluations are synthesized in the following section as best practices and challenges for integrating DBR and AS in the design of inclusive multimedia systems.

4. Best Practices for Integrating DBR with Scrum in Inclusive Multimedia Design

Drawing on the iterative development of the accessible AR learning authoring tool, this study identified several best practices that facilitated the successful integration of DBR with Scrum. These practices are proposed as guidelines for teams undertaking similar projects at the intersection of inclusive multimedia technology, user-centered design, and agile development.

4.1. Engage End-Users Continuously

In DBR–Agile integration, end-users should be regarded as co-designers rather than peripheral testers. From the earliest problem-analysis phase, we engaged instructors and students, including those with disabilities, in interviews, co-design workshops, and usability tests. Their involvement continued through sprint reviews and formal evaluations, ensuring that each development increment of the AR authoring tool was validated against authentic user needs. This practice aligns with DBR’s principle of collaborative partnership [

5,

6] and Agile’s user-centered ethos [

48]. Prior research highlights that sustained practitioner participation enhances both ecological validity and the relevance of design outcomes [

7,

49]. By embedding users in every sprint cycle, we not only surfaced issues early but also cultivated shared ownership of accessibility outcomes.

4.2. Use Accessibility-Focused User Stories

Accessibility requirements are often marginalized or treated as compliance checklists [

50]. To counter this, we explicitly phrased user stories from the perspective of users with specific accessibility needs, e.g., “As a blind instructor, I want the multimedia interface to be fully navigable by voice, so I can independently create AR content.” This practice reinforced empathy within the development team, provided concrete acceptance criteria, and ensured accessibility was central rather than peripheral to backlog prioritization. Inclusive design literature recommends integrating disability personas and scenarios at the earliest stages of design [

37,

51,

52]. In line with these recommendations, we recommend always including disability personas in the product backlog and regularly refining user stories to avoid assumptions or bias. Our experience suggests that accessibility-focused stories can act as “living artefacts” [

40], evolving alongside user insights while continuously anchoring the team in inclusive design goals.

4.3. Align Iteration Cycles

A central methodological adaptation was synchronizing DBR iterations with Scrum sprints. We structured one DBR cycle around approximately two to three Scrum sprints, culminating in a more formal formative evaluation. This hybrid structure balanced Scrum’s rapid delivery with DBR’s emphasis on theory-informed reflection[

19]. For example, within six weeks, we were able to have a functional prototype that could be tested. Prior work has emphasized the value of aligning Agile iterations with DBR cycles to accelerate feedback and learning in educational contexts [

31,

32]. We therefore recommend aligning DBR evaluation milestones with sprint reviews to ensure that user interactions directly inform both multimedia design artefacts and emergent theory.

4.4. Define Roles and Responsibilities Clearly

Blending research and development teams risks role confusion. We mitigated this by adopting hybrid role definitions. The Product Owner role was assigned to the lead researcher, ensuring accessibility remained a top priority in backlog management and that research questions were explicitly addressed. Developers were expected not only to implement features but also to contribute observational insights to research, while the Scrum Master facilitated processes that accommodated additional research needs (e.g., scheduling usability testing). Confrey [

31] emphasizes the importance of clear communication and role definition in sustaining DBR projects with Agile methodologies. Our adaptation reinforces that assigning the researcher as Product Owner can balance product-oriented and research-oriented priorities, avoiding conflict while enhancing accountability.

4.5. Maintain a Dual Focus: Product and Knowledge

A recurrent risk in DBR–Agile integration is privileging either the product (software artefact) or knowledge generation (research contribution) to the detriment of the other [

53]. We addressed this by explicitly treating both goals as inseparable deliverables. Sprint reviews and retrospectives included reflective questions such as “What design principle emerged?” and “Which accessibility assumption was challenged?” Research tasks (e.g., “Analyze interview data from prototype test”) were tracked alongside development tasks on the kanban board, ensuring equal visibility and accountability. This approach resonates with calls to ensure that design experiments generate both practical artefacts and theoretical insights [

38,

46]. By embedding research analysis into each sprint, we upheld scientific rigor while maintaining Agile’s delivery velocity.

4.6. Adapt Agile Artefacts for Research

Scrum artefacts were adapted to better fit DBR requirements. Our product backlog incorporated both feature stories and research stories, ensuring systematic attention to data collection and analysis tasks. Sprint backlogs and burndown charts were used flexibly, acknowledging that research activities (e.g., thematic coding of interviews) progress differently from coding tasks. We also maintained a design journal linked to backlog items, documenting which design principles were supported or challenged by user feedback. This traceability is essential in DBR to connect artefact design decisions with empirical evidence [

19]. Such adaptations ensured that Agile artefacts not only drove software development but also strengthened research accountability and transparency.

4.7. Embrace Scrumban for Flexibility

While Scrum provided cadence and structure, we incorporated Kanban principles—creating a Scrumban approach—to address the inherent unpredictability of field research [

54,

55]. For instance, user testing sessions often shifted due to participants’ availability, requiring adjustments to sprint goals. Work-in-progress (WIP) limits and continuous flow mechanisms allowed us to remain flexible without compromising Scrum’s discipline. Scrumban has been recognized as a pragmatic adaptation in complex contexts where both planned iterations and emergent tasks coexist [

56]. For DBR projects in multimedia technology, this hybrid approach strikes a balance between the need for research responsiveness and the benefits of structured iteration.

4.8. Foster Frequent Communication and Reflection

Finally, communication and reflection were emphasized beyond conventional Agile practice. In addition to daily stand-ups, we held mid-sprint checkpoints whenever user engagements occurred and biweekly consultations with accessibility experts. These mechanisms ensured alignment, minimized the risk of diverging priorities, and reinforced accountability to end-user needs. Agile scholarship consistently emphasizes communication as central to team effectiveness [

57,

58]. Our adaptation extended this principle to include external collaborators and users, echoing DBR’s requirement for ongoing reflection and knowledge generation [

19].

5. Challenges and Potential Mitigation Strategies

The integration of DBR and Scrum proved productive for developing an inclusive AR authoring tool, but introduced complexities beyond those of single-method approaches. Below, we discuss the main challenges encountered and the strategies employed to address them, highlighting pragmatic lessons for multimedia research and practice.

5.1. Balancing Research and Development Priorities

A persistent challenge was balancing the dual goals of producing a robust software artefact and generating generalizable research insights. Developers emphasized product quality (e.g., managing technical debt, implementing new features), while researchers required pauses for data collection and analysis. This tension has been widely observed in interdisciplinary projects where academic and industry priorities intersect [

19,

46].

Mitigation: We allocated explicit sprint capacity for both research and development tasks, and alternated sprint emphasis (“dev-heavy” vs. “research-heavy”) to manage workload. Maintaining parallel roadmaps (product and research) ensured that milestones such as user studies were synchronized with relevant feature releases. The Product Owner role, held by the lead researcher, was instrumental in making informed trade-offs, echoing prior recommendations on unified leadership in hybrid projects [

31].

5.2. Scope Creep and Iteration Management

The openness of DBR and Agile created risks of scope expansion as stakeholder feedback revealed new possibilities. Such scope creep is a known challenge in design research, particularly due to the emergence of new insights [

53].

Mitigation: We employed a “feature budget” per DBR cycle, prioritizing non-negotiable accessibility features and deferring enhancements to future iterations. This strategy combined the Agile principle of a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) [

59] with DBR’s notion of satisficing [

53], ensuring the artefact was sufficiently functional for research purposes without uncontrolled expansion.

5.3. Timing and Scheduling Conflicts

Scrum’s fixed sprint cadence often conflicted with stakeholders' schedules, such as holiday seasons that disrupted planned evaluations. Similar timing challenges have been noted in other DBR projects [

19,

47].

Mitigation: We adopted a Scrumban approach, introducing buffer sprints to absorb delays. This adaptation reflects Agile’s principle of “responding to change” [

54] and has been recommended in hybrid Agile–research contexts [

56].

5.4. Ensuring Rigor in Data Collection and Analysis

Agile’s rapid iterations risked producing anecdotal rather than systematic data, potentially undermining DBR’s research integrity. Similar risks of insufficient rigor have been flagged in design experiments [

46].

Mitigation: We standardized data collection instruments (e.g., consistent usability surveys across iterations) and allocated dedicated “analysis sprints” following major evaluations. During these, developers focused on refactoring and technical debt, while researchers analyzed data. This balance preserved Agile momentum while maintaining research rigor.

5.5. Iteration Fatigue

Repeated cycles led to fatigue among instructors and developers, with reduced enthusiasm for testing by the third DBR iteration. Iteration fatigue is a known issue in participatory design projects with prolonged engagement [

60].

Mitigation: We maintained enthusiasm by celebrating incremental successes at sprint reviews to sustain morale and by attending conferences and publishing our results. Publishing interim results provided external validation, reinforcing the value of continued engagement. This practice aligns Agile’s ethos of celebrating small wins [

61,

62] with DBR’s emphasis on meaningful, cumulative impact [

63].

5.6. Transferability and Generalization

A common critique of DBR is limited generalizability due to its context-specific nature [

7]. We faced concerns about whether findings would extend beyond the specific AR tool and institutional context.

Mitigation: To enhance transferability, we articulated underlying design principles (e.g., multimodal feedback, accessibility-first user stories) alongside tool-specific findings. We also tested prototypes across varied institutional contexts and sought external expert review, aligning with recommendations to document both process and principles for broader applicability [

64,

65].

These challenges underscore that while integrating DBR and Scrum offers significant advantages for inclusive multimedia design, it requires deliberate strategies for balance, scope control, scheduling, communication, rigor, sustainability, and transferability. By systematically documenting these challenges and their mitigation, this study provides practical insights for researchers and practitioners seeking to employ hybrid methodologies in educational multimedia system design.

6. Discussion

6.1. Interpreting the Findings: Toward a Pragmatic Model for Inclusive Multimedia Design

This study demonstrates that integrating DBR with Agile Scrum constitutes a pragmatic and effective methodological framework for designing inclusive multimedia systems. The best practices identified—ranging from continuous user engagement to accessibility-focused user stories—function not simply as ad hoc solutions but as interdependent elements of a coherent model. Together, they address the dual demands of DBR (theory-driven inquiry in authentic contexts) and Scrum (empirical, incremental software development). Previous research has highlighted tensions between the need for rigorous knowledge production and the drive for efficient software delivery [

66,

67]. Our findings suggest that this tension can be constructively managed by embedding research activities into Scrum artifacts and ceremonies, thereby ensuring that development remains evidence-driven while research outcomes remain practically grounded.

The model presented here foregrounds accessibility as a central design principle, demonstrating that inclusivity need not be relegated to compliance checklists or peripheral testing [

44,

68]. By reconfiguring standard Agile artefacts—particularly user stories—as accessibility-first design tools, the framework extends Agile’s user-centered ethos toward a more ethically-grounded inclusive practice. This approach reflects broader calls in HCI and multimedia research to embed equity and accessibility at the foundation of design processes rather than treating them as retrofits [

51,

69].

6.2. Relationship to Prior Work

This work contributes to the growing literature on DBR–Agile integration by situating inclusivity at the center of methodological hybridization. Prior research has explored such integrations with varied emphases: pedagogical practice [

30], leadership and team management [

31], methodological tailoring for vocational education [

32], bridging research paradigms [

17], and conceptual framework development [

4]. Our study complements and extends these contributions by providing a detailed, situated case study of hybrid methodology applied to accessible multimedia technology design.

Specifically, our findings extend Confrey’s [

31] argument that Agile supports DBR sustainability by demonstrating how Agile artefacts can be systematically adapted to prioritize accessibility. They also respond to Cochrane’s [

32] caution that Agile risks privileging delivery speed over theoretical rigor by showing how accessibility-focused user stories and synchronized DBR–Scrum cycles preserve both research and design quality. Unlike Kastl and Romeike [

30], who focus on pedagogy, our contribution lies in system-level product design, offering actionable insights for HCI and multimedia researchers developing real-world tools. Finally, while Fahd et al. [

17] and Smith-Nunes [

4] offer theoretical integration frameworks, our study provides an empirical complement by demonstrating concrete adaptations, challenges, and mitigation strategies.

6.3. Broader Implications and Future Work

The lessons derived from this project are not confined to the development of an AR authoring tool. The identified practices—such as the systematic use of accessibility-focused user stories, the adaptation of Agile ceremonies for research reflection, and the use of Scrumban for flexibility—constitute transferable strategies for other multimedia contexts, including virtual reality learning environments, cross-modal data visualizations, and interactive multimedia for diverse learners. Our findings, therefore, contribute to ongoing debates on inclusive multimedia design [

70,

71,

72] by offering a replicable blueprint for aligning technological innovation with societal responsibility.

Nonetheless, the findings are shaped by the specific institutional and technological context of this project. As with most DBR studies, transferability depends on documenting both processes and underlying principles [

12,

64]. Future research should test the scalability of this hybrid framework in various contexts, such as K–12 education, vocational training, or informal learning, and with different multimedia technologies. Longitudinal studies are also needed to investigate the sustainability of hybrid practices and their long-term impact on team dynamics, accessibility outcomes, and organizational culture.

7. Conclusions

This paper presented a systematic and situated account of integrating DBR and Agile Scrum to design inclusive multimedia technology. By strategically blending DBR’s iterative, theory-driven inquiry with Scrum’s structured, empirical development cycles, we demonstrated that it is possible to deliver a functional system while generating generalizable design knowledge. The primary contribution lies in articulating a set of best practices and mitigation strategies—including accessibility-focused user stories, synchronized DBR–Scrum cycles, and adapted Agile artefacts—that directly support accessibility in immersive multimedia systems.

By centering inclusivity within this hybrid framework, the study advances a socio-technical approach to system design, moving beyond accessibility as compliance toward accessibility as a guiding design principle. This model provides a replicable blueprint for researchers and practitioners in multimedia and HCI who seek to integrate rigorous research with efficient development while ensuring equity and inclusivity. Ultimately, the study underscores that the future of multimedia technology must not only be innovative but also accessible, ensuring that diverse users are co-creators and beneficiaries of technological progress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Deogratias Shidende; Supervision, Sabine Moebs; Visualization, Deogratias Shidende; Writing – original draft, Deogratias Shidende; Writing – review & editing, Deogratias Shidende and Sabine Moebs.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were not required for this non-interventional research because no personal data were collected or processed; responses were fully anonymous and could not be linked to individuals. Under GDPR Recital 26 and the German Research Foundation (DFG), projects in which the entire data collection is anonymous fall outside the scope of data protection review/notification.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study consist solely of documenting the DBR/Agile processes. They can be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR |

Augmented Reality |

| DBR |

Designed-Based Research |

| AS |

Agile Scrum |

| HCI |

Human Computer Interaction |

| MVP |

Minimum Viable Product |

| WCAG |

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines |

| UDL |

Universal Design for Learning |

References

- Shidende, D., Kessel, T., Treydte, A., Moebs, S.: A Systematic Literature Review of Accessibility Evaluation Methods for Augmented Reality Applications. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 306, 575–582 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Westin, T., Neves, J., Mozelius, P., Sousa, C., Mantovan, L.: Inclusive AR-games for Education of Deaf Children: Challenges and Opportunities. Eur. Conf. Games Based Learn. 16, 597–604 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Bray, A., Devitt, A., Banks, J., Sanchez Fuentes, S., Sandoval, M., Riviou, K., Byrne, D., Flood, M., Reale, J., Terrenzio, S.: What next for Universal Design for Learning? A systematic literature review of technology in UDL implementations at second level. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 55, 113–138 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Smith-Nunes, G.: AgileDBR: Blending Industry and Academic Practice. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 1–18 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T., Shattuck, J.: Design-Based Research: A Decade of Progress in Education Research? Educ. Res. 41, 16–25 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Hannafin, M.J.: Design-based research and technology-enhanced learning environments. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 53, 5–23 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Design-Based Research Collective: Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educ. Res. 32, 5–8 (2003).

- Plomp, T.: Educational design research: An introduction. Educ. Des. Res. 11–50 (2013).

- Minichiello, A., Caldwell, L.: A Narrative Review of Design-Based Research in Engineering Education: Opportunities and Challenges | Studies in Engineering Education. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Fowler, S., Cutting, C., Fiedler, S.H.D., Leonard, S.N.: Design-based research in mathematics education: trends, challenges and potential. Math. Educ. Res. J. 35, 635–658 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Lee, Y.-Y.: Challenges and opportunities of design-based research in applied linguistics: Insights from a scoping review. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 4, 100178 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Easterday, M.W., Lewis, D.R., Gerber, E.M.: Design-based research process: Problems, phases, and applications. Presented at the (2014).

- Tona, C., Jiménez, S., Juárez-Ramírez, R., Pacheco López, R.G., Quezada, Á., Guerra-García, C.: Scrumlity: An Agile Framework Based on Quality of User Stories. Program. Comput. Softw. 48, 702–715 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Hayati, N., Kadarohman, A., Sopandi, W., Martoprawiro, M.A.: Implementation of the Scrum Methodology in Learning Chemistry to Improve Scientific Literacy: A Review. KnE Soc. Sci. 9, 129–139 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A., Baham, C., Davis, J.: An Investigation Into Product Owner Practices in Scrum Implementations. In: Agile Scrum Implementation and Its Long-Term Impact on Organizations. pp. 99–113. IGI Global (2021).

- Shidende, D.: Design and implementation of accessible open-source augmented reality learning authoring tool. In: Proceedings of the Doctoral Consortium of the Sixteenth European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning co-located with the Sixteenth European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning (EC-TEL 2021). pp. 22–30. CEUR-WS. org, Bolzano, Italy (2021).

- Fahd, K., Miah, S.J., Ahmed, K., Venkatraman, S., Miao, Y.: Integrating design science research and design based research frameworks for developing education support systems. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26, 4027–4048 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Reeves, T.C.: Design research from a technology perspective. In: Educational Design Research. Routledge (2006).

- McKenney, S., Reeves, T.: Conducting Educational Design Research. Routledge, London (2018). [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, H., Moonaghi, H.K., Golbaf, R.: Design-Based Research: Definition, Characteristics, Application and Challenges. J. Educ. Black Sea Reg. 5, 26–35 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Maier, P., Ma, Z., Bloem, R.: Towards a Secure SCRUM Process for Agile Web Application Development. In: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security. pp. 1–8. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA (2017). [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A., Bhardwaj, S., Saraswat, S.: SCRUM model for agile methodology. In: 2017 International Conference on Computing, Communication and Automation (ICCCA). pp. 864–869 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Mabiletsa, O., Omowunmi, I., Viljoen, S., Farrell, J., Ngqwemla, L.: Immersive Interactive Technology: a Case Study of a Wine Farm. In: 2020 ITU Kaleidoscope: Industry-Driven Digital Transformation (ITU K). pp. 1–7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H., Nonaka, I.: The new new product development game. Harv. Bus. Rev. 64, 137–146 (1986).

- Sarkar, T., Moharana, B., Rakhra, M., Cheema, G.S.: Comparative Analysis of Empirical Research on Agile Software Development Approaches. In: 2024 11th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO). pp. 1–6 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mabiletsa, O., Viljoen, S.J., Farrell, J.A., Ngqwemla, L., Isafiade, O.E.: An Immersive Tractor Application for Sustainability: A South African Land Reform and Learners’ Perspective. In: International Journal of Virtual and Augmented Reality. pp. 35–54 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Berezutskyi, I., Tsiutsiura, S., Rusan, I., Sachenko, I., Danylyshyn, S.: Disadvantages of Using Scrum Model in IT Projects. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Smart Information Systems and Technologies (SIST). pp. 89–93 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A., Butt, S.A., Jamal, T., Gochhait, S.: Agile Scrum Issues at Large-Scale Distributed Projects: Scrum Project Development At Large. Int. J. Softw. Innov. 8, 85–94 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lorber, A.A., Mish, K.D.: How We Successfully Adapted Agile for a Research-Heavy Engineering Software Team. In: 2013 Agile Conference. pp. 156–163 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Kastl, P., Romeike, R.: Agile projects to foster cooperative learning in heterogeneous classes. In: 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON). pp. 1182–1191 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Confrey, J.: Leading a Design-Based Research Team Using Agile Methodologies to Build Learner-Centered Software. In: Leatham, K.R. (ed.) Designing, Conducting, and Publishing Quality Research in Mathematics Education. pp. 123–142. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2019). [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, T.: hybrid Design based research for Agile Software development (hDAS) in ISD contexts: a discovery from studying how to design MUVEs for VET. In: 6th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’20). pp. 875–882. Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València (2020).

- Schwaber, K., Beedle, M.: Agile Software Development with Scrum. Prentice Hall PTR, USA (2001).

- Cochrane, T., Davis, N.E., Mackey, J.: Design-Based Research with AGILE Sprints to Produce MUVES in Vocational Education. In: Utilizing Virtual and Personal Learning Environments for Optimal Learning. pp. 291–313. IGI Global Scientific Publishing (2016). [CrossRef]

- Shidende, D., Kessel, T., Treydte, A., Moebs, S.: A Personalized Captioning Strategy for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Users in an Augmented Reality Environment. In: De Paolis, L.T., Arpaia, P., and Sacco, M. (eds.) Extended Reality. pp. 3–21. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham (2024). [CrossRef]

- W3C: Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1, https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/, last accessed 2022/11/10.

- Rose, D.: Universal Design for Learning. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 15, 47–51 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, D.H.J.M.: How theory and design-based research can mature PBL practice and research. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 24, 879–891 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Shidende, D., Kessel, T., Moebs, S.: Towards Accessible Augmented Reality Learning Authoring Tool: A Case of MirageXR. In: 2023 IST-Africa Conference (IST-Africa). pp. 1–13 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Cohn, M.: User Stories Applied: For Agile Software Development. Addison-Wesley Professional (2004).

- Barua, T., Rahman, M.A.: A Systematic Literature Review of User-Centric Design in Digital Business Systems Enhancing Accessibility, Adoption, and Organisational Impact. Am. J. Sch. Res. Innov. 2, 193–216 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Saju, M.H., Alwidian, S., Mazumder, P., Azim, A.: A Structured Approach to Accessibility in Software Development Lifecycle. In: 2025 IEEE/ACM International Workshop on Designing Software (Designing). pp. 39–46 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ecar, M., Kepler, F., da Silva, J.P.S.: Cosmic user story standard. In: International Conference on Agile Software Development. pp. 3–18. Springer (2018).

- Lazar, J., Goldstein, D.F., Taylor, A.: Ensuring Digital Accessibility through Process and Policy. Morgan Kaufmann (2015).

- Silva, M. , Roberto, R., Radu, I., Cavalcante, P., Schneider, B., Teichrieb, V.: Development of Design Principles for AR Authoring Tools for Education Based on Teacher’s Perspectives. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 17, 677–690 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Cobb, P. , Confrey, J., diSessa, A., Lehrer, R., Schauble, L.: Design Experiments in Educational Research. Educ. Res. 32, 9–13 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Amiel, T. , Reeves, T.C.: Design-Based Research and Educational Technology: Rethinking Technology and the Research Agenda. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 11, 29–40 (2008).

- Taslim, A. : Towards a Framework for Integration of User-Centered Design and Agile Methodology. J. Comput. Sci. 3, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B. , Phipps, L., Swift, E.: Developing a Holistic Approach for E-Learning Accessibility. Can. J. Learn. Technol. Rev. Can. L’apprentissage Technol. 30, (2004).

- Seale, J. : E-learning and Disability in Higher Education: Accessibility Research and Practice. Routledge, New York (2013). [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.J. , Coleman, R., Keates, S., Lebbon, C.: Inclusive Design: Design for the Whole Population. Springer Science & Business Media (2013).

- Story, M.F., Mueller, J.L., Mace, R.L.: The Universal Design File: Designing for People of All Ages and Abilities. Revised Edition. (1998).

- van den Akker, J. , Gravemeijer, K., McKenney, S., Nieveen, N.: Educational design research: the value of variety. In: Educational Design Research. Routledge (2006).

- Campanelli, A.S. , Parreiras, F.S.: Agile methods tailoring – A systematic literature review. J. Syst. Softw. 110, 85–100 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Ladas, C.: Scrumban - Essays on Kanban Systems for Lean Software Development. Lulu.com (2009).

- Ahmad, M.O. , Markkula, J., Oivo, M.: Kanban in software development: A systematic literature review. In: 2013 39th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications. pp. 9–16 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Moe, N.B. , Dingsøyr, T., Dybå, T.: A teamwork model for understanding an agile team: A case study of a Scrum project. Inf. Softw. Technol. 52, 480–491 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Zaimovic, T. , Kozic, M., Efendić, A., Džanić, A.: Self - Organizing Teams in Software Development – Myth or Reality. TEM J. 1565–1571 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Jones, W. , Gun, P., Foumani, M.: An MVP Approach to Developing Complex Hybrid Simulation Models. In: 2022 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC). pp. 1176–1187 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, J. , Hertzum, M.: Sustained Participatory Design: Extending the Iterative Approach. Des. Issues. 28, 10–21 (2012).

- Ranganath, P. : Elevating Teams from “Doing” Agile to “Being” and “Living” Agile. In: 2011 Agile Conference. pp. 187–194 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.: Sooner Safer Happier: Antipatterns and Patterns for Business Agility. IT Revolution (2020).

- Fowler, S. , Leonard, S.N.: Using design based research to shift perspectives: a model for sustainable professional development for the innovative use of digital tools. Prof. Dev. Educ. 50, 192–204 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Reinmann, G. : Outline of a holistic design-based research model for higher education. EDeR Educ. Des. Res. 4, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Tammeleht, A. : Iteration type I of holistic DBR - transferability of design Principles. EDeR Educ. Des. Res. 6, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gregg, D.G. , Kulkarni, U.R., Vinzé, A.S.: Understanding the Philosophical Underpinnings of Software Engineering Research in Information Systems. Inf. Syst. Front. 3, 169–183 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Staron, M. : Action Research in Software Engineering: Metrics’ Research Perspective (Invited Talk). In: Catania, B., Královič, R., Nawrocki, J., and Pighizzini, G. (eds.) SOFSEM 2019: Theory and Practice of Computer Science. pp. 39–49. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2019). [CrossRef]

- Nicoson, E. , Ha-Brookshire, J.: Beyond Accessibility Compliance: Exploring the Role of Information on Apparel Shopping Websites for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Societies. 15, 90 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Burgstahler, S. : Universal Design: Process, Principles, and Applications. DO-IT (2009).

- Kaimara, P. , Deliyannis, I., Oikonomou, A.: Content Design for Inclusive Educational Environments. In: Daniela, L. (ed.) Inclusive Digital Education. pp. 97–121. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2022). [CrossRef]

- Persson, H. , Åhman, H., Yngling, A.A., Gulliksen, J.: Universal design, inclusive design, accessible design, design for all: different concepts—one goal? On the concept of accessibility—historical, methodological and philosophical aspects. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 14, 505–526 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Turel, V. , Kılıç, E.: The Inclusion and Design of Cultural Differences in Interactive Multimedia Environments. In: Human Rights and the Impact of ICT in the Public Sphere: Participation, Democracy, and Political Autonomy. pp. 245–267. IGI Global Scientific Publishing (2014). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).