Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To develop high frequency model of induction motor per phase model for common mode and differential mode impedance characteristics.

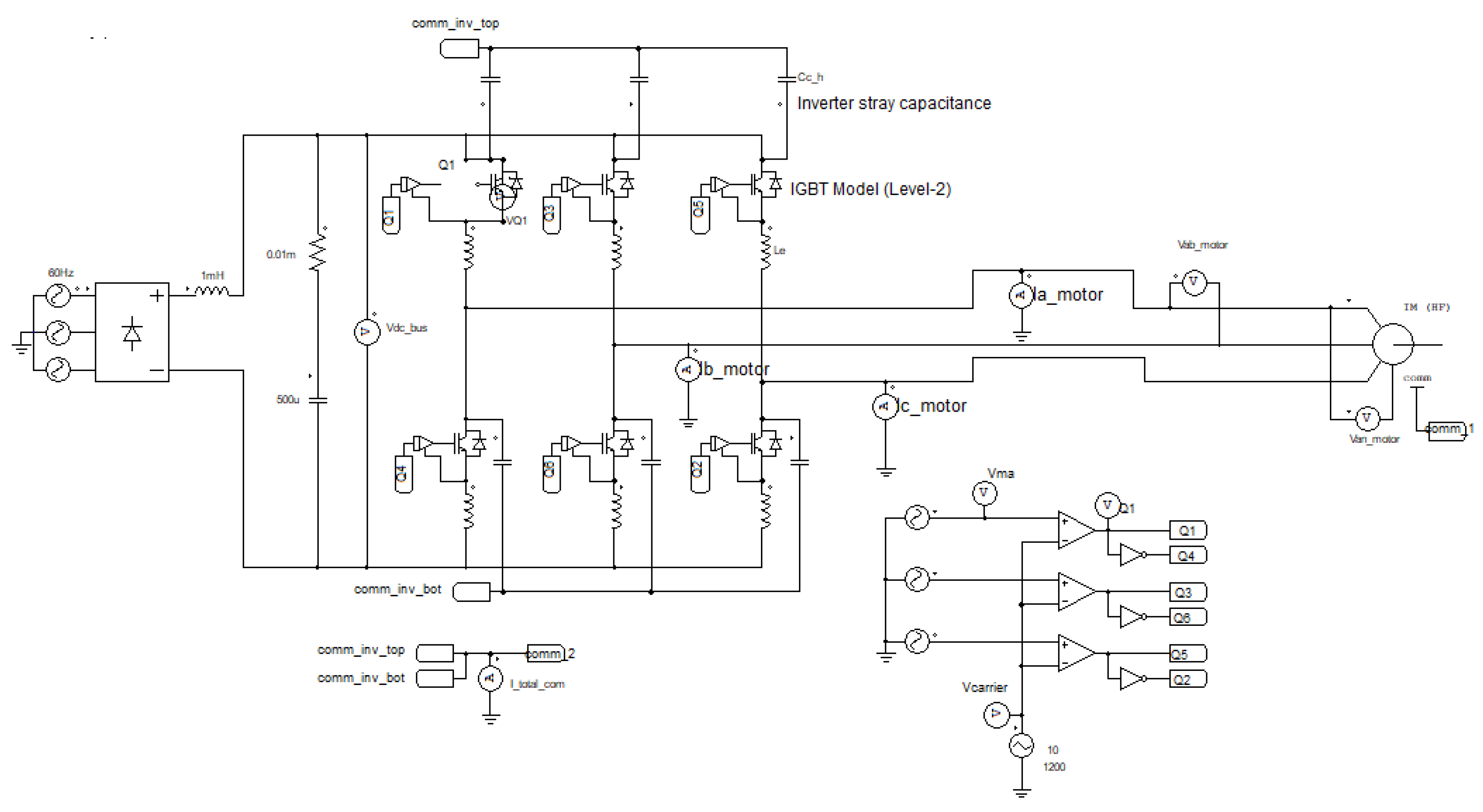

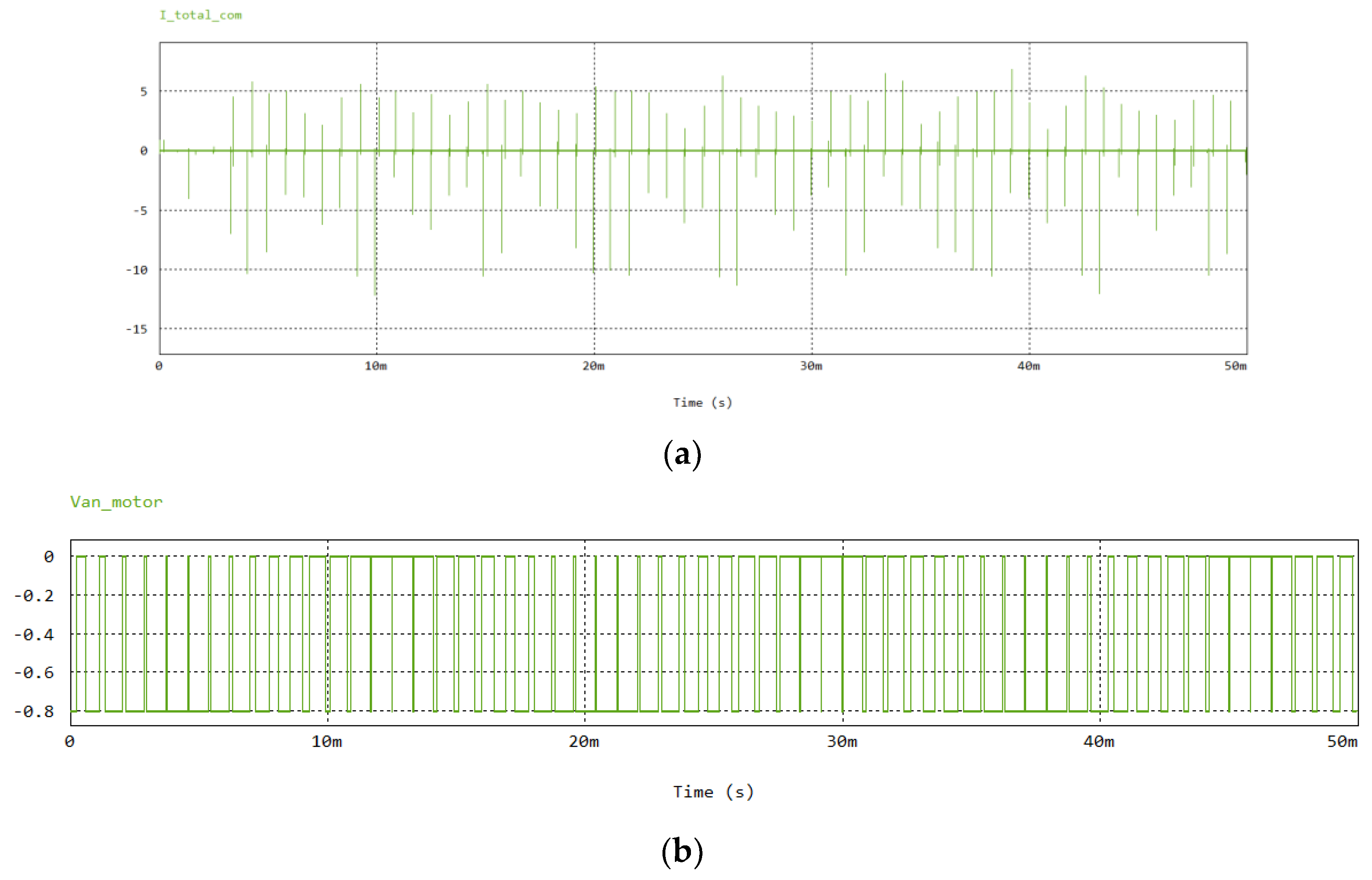

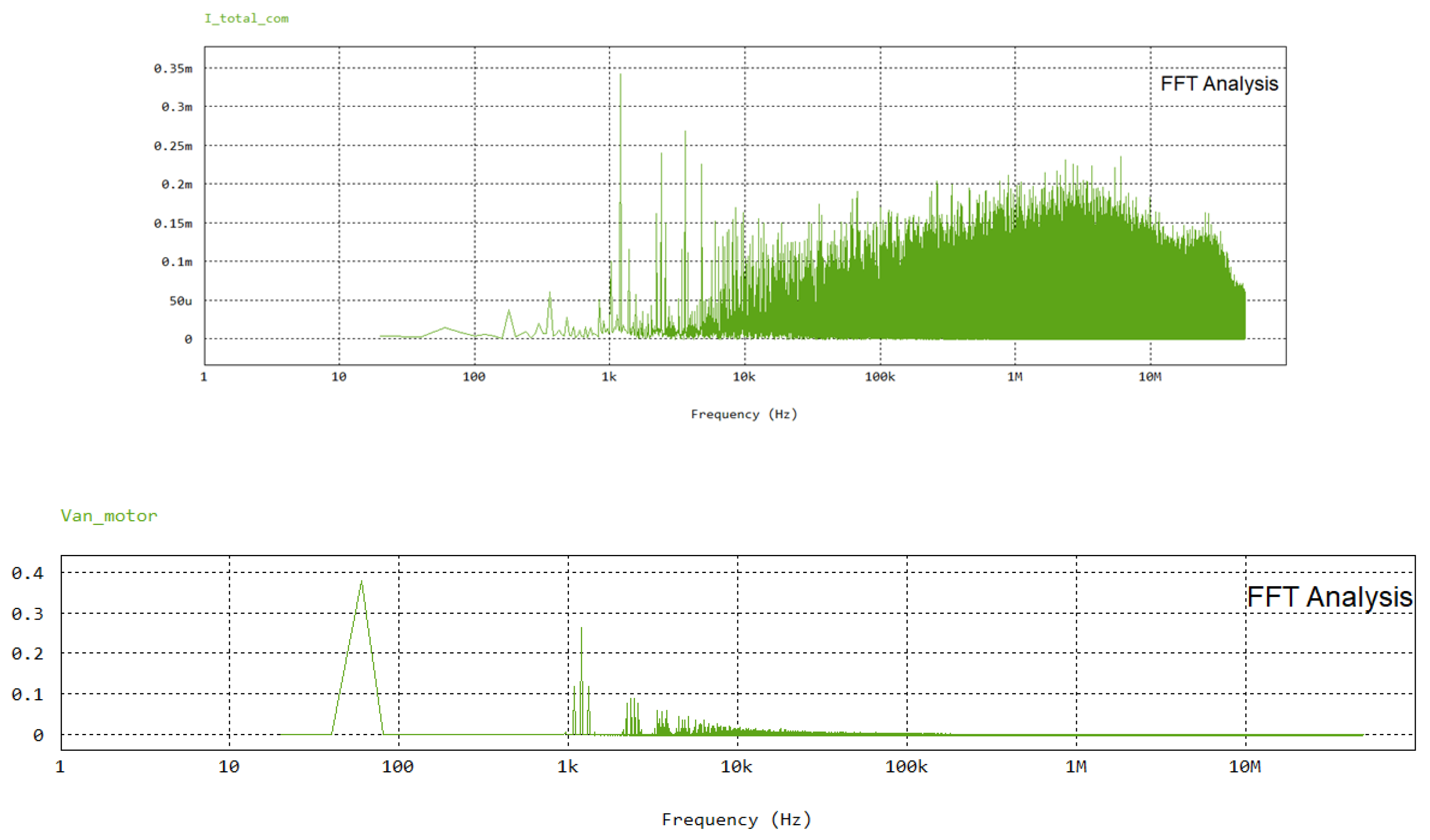

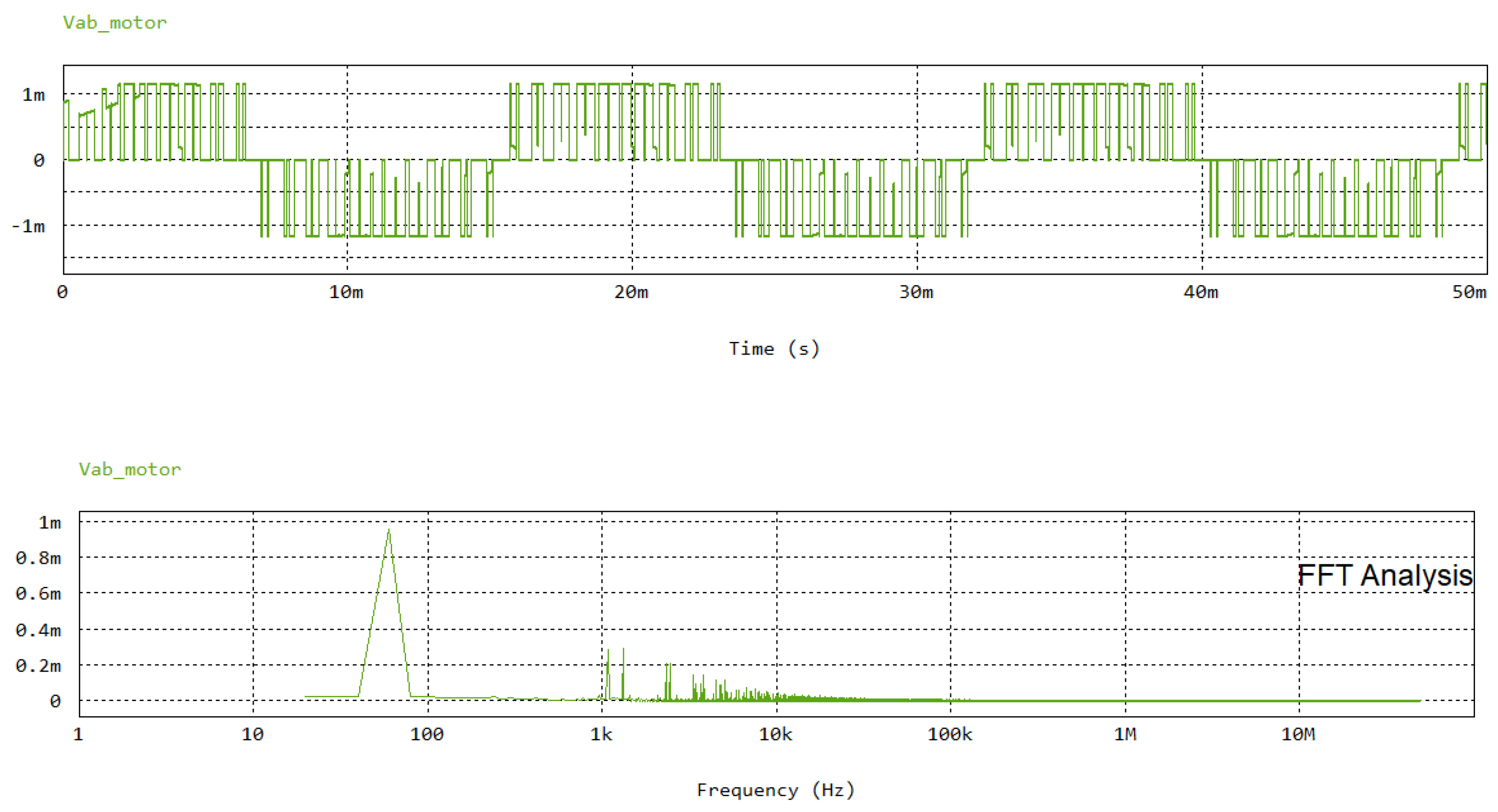

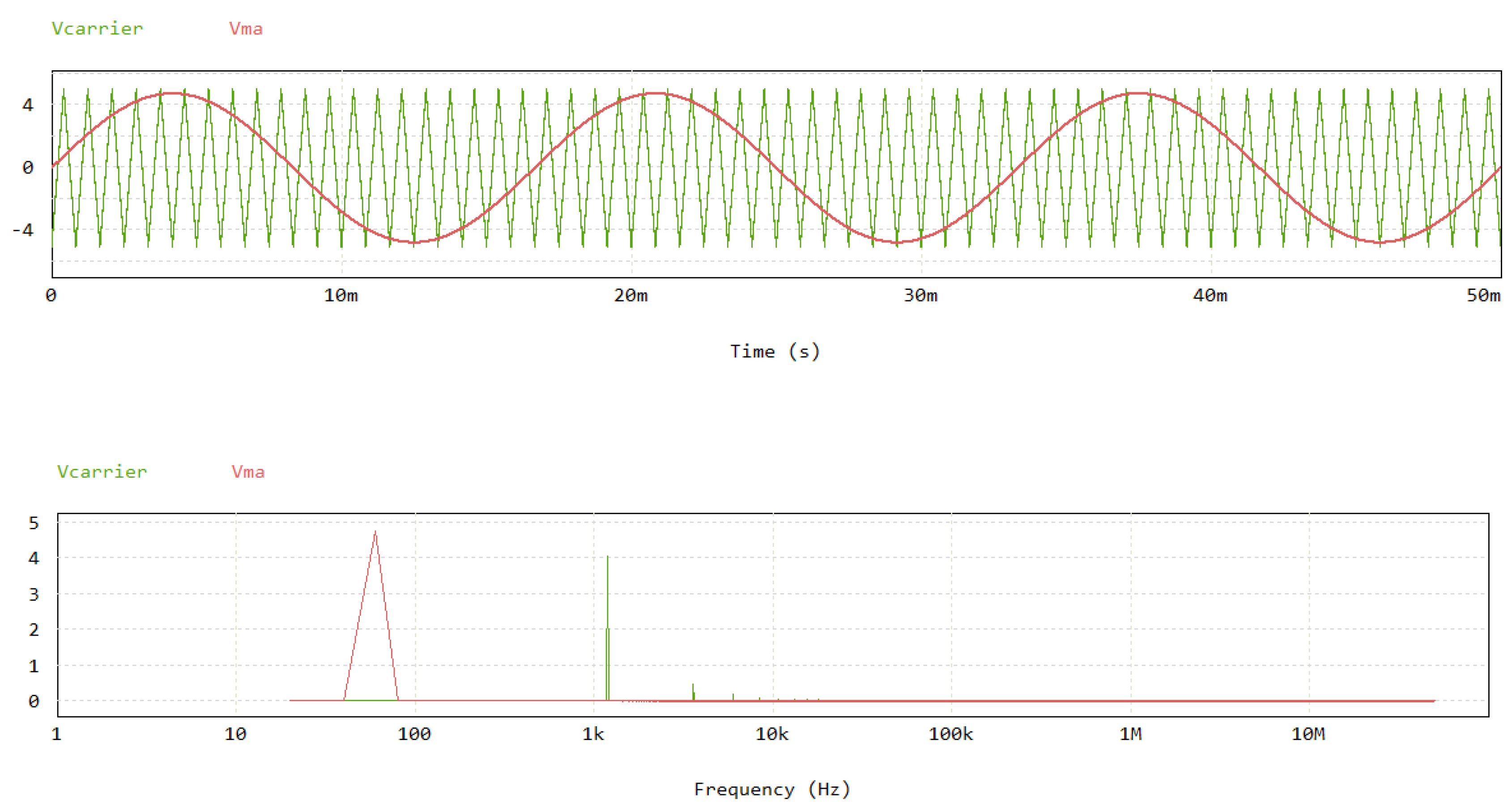

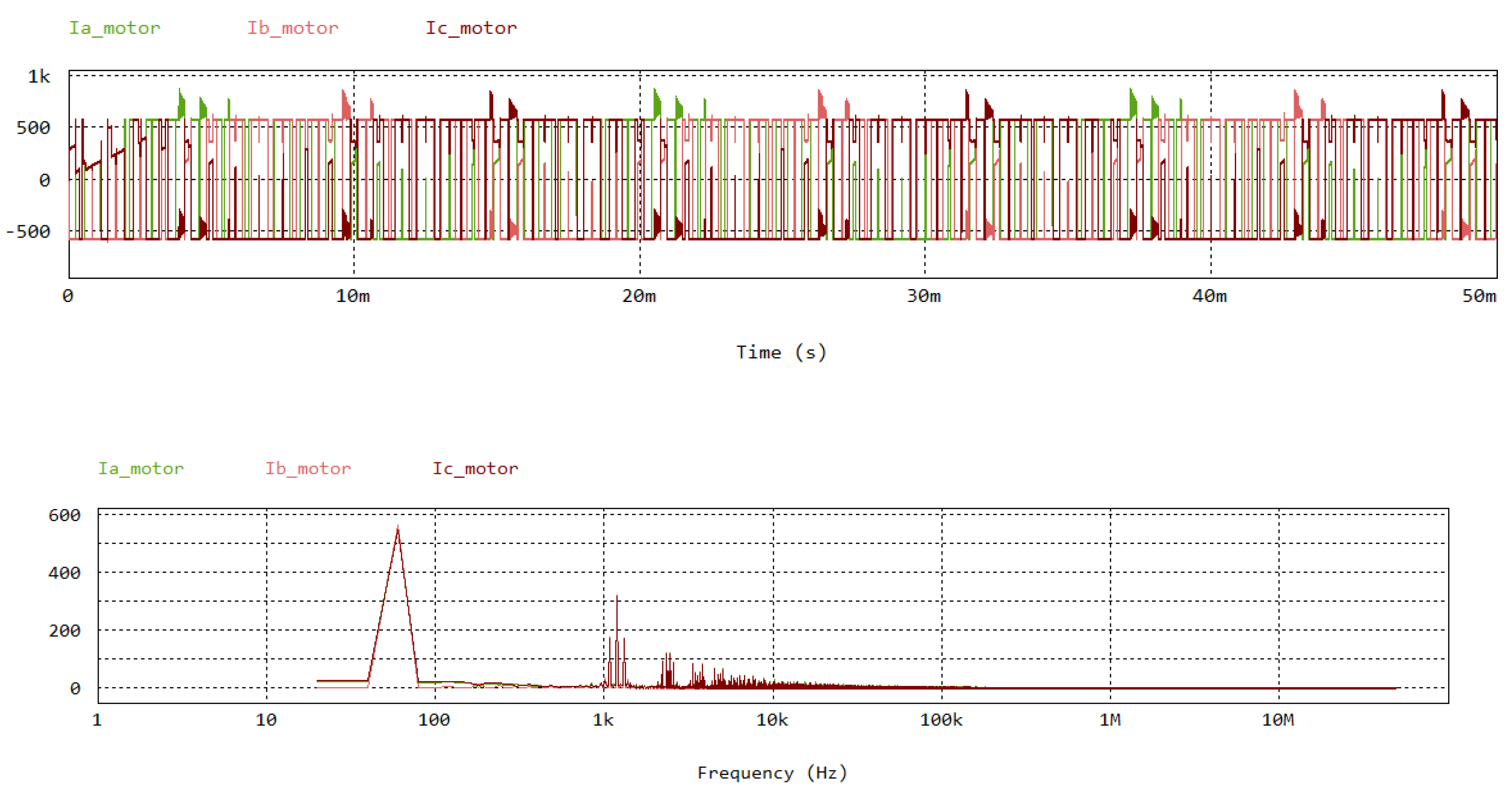

- The High frequency model of the IM drive for common mode characteristics was tested by the POWERSIM simulation model.

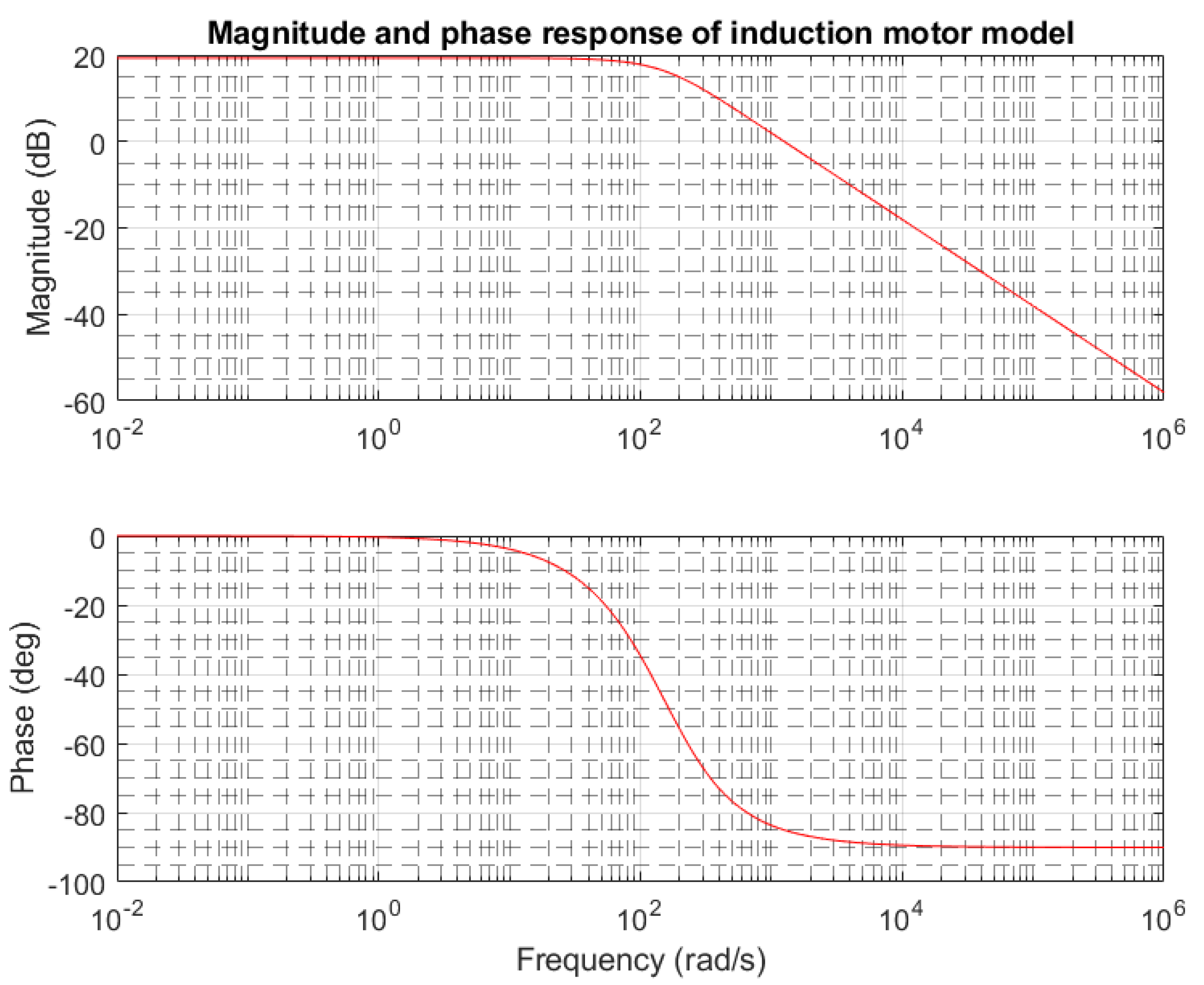

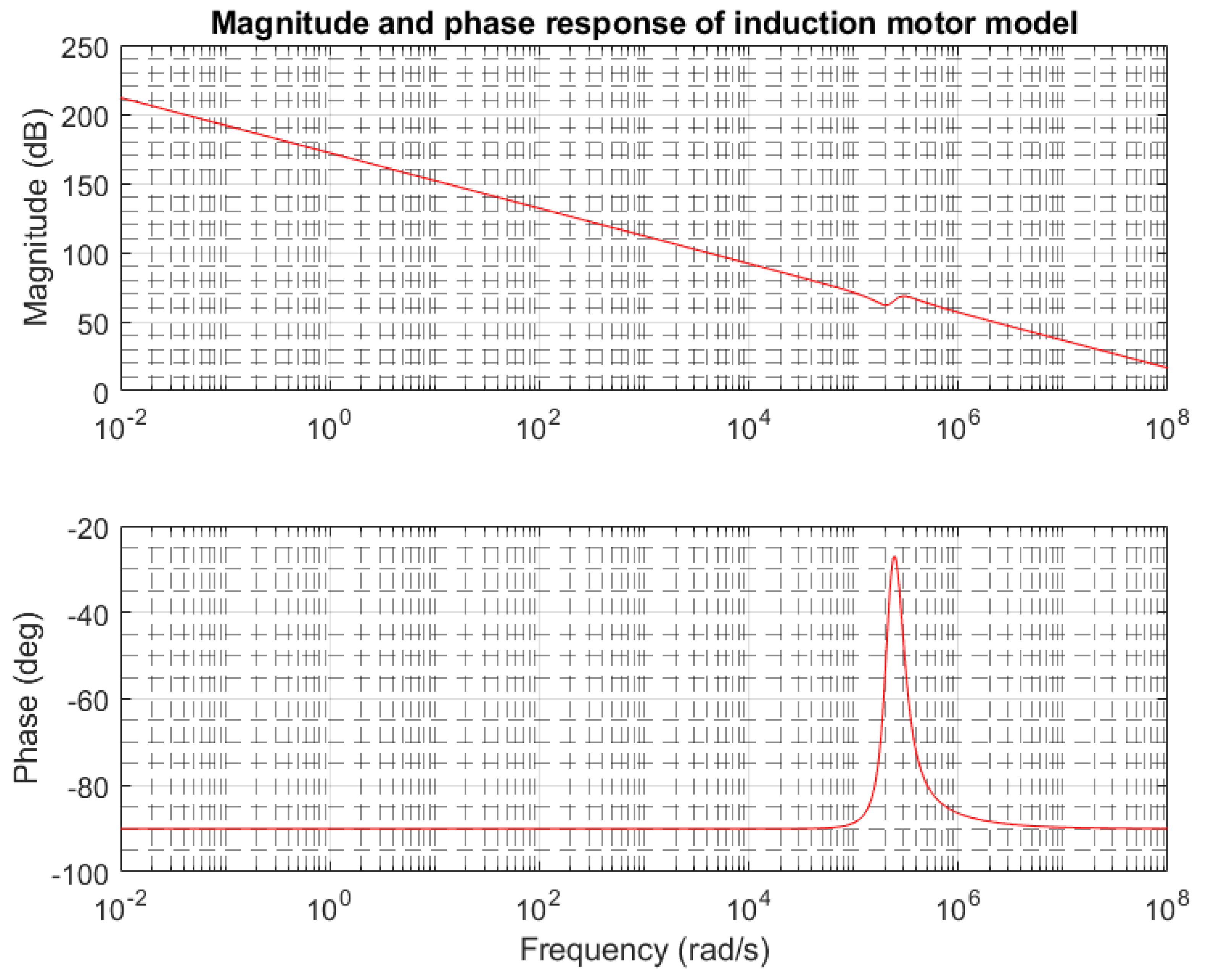

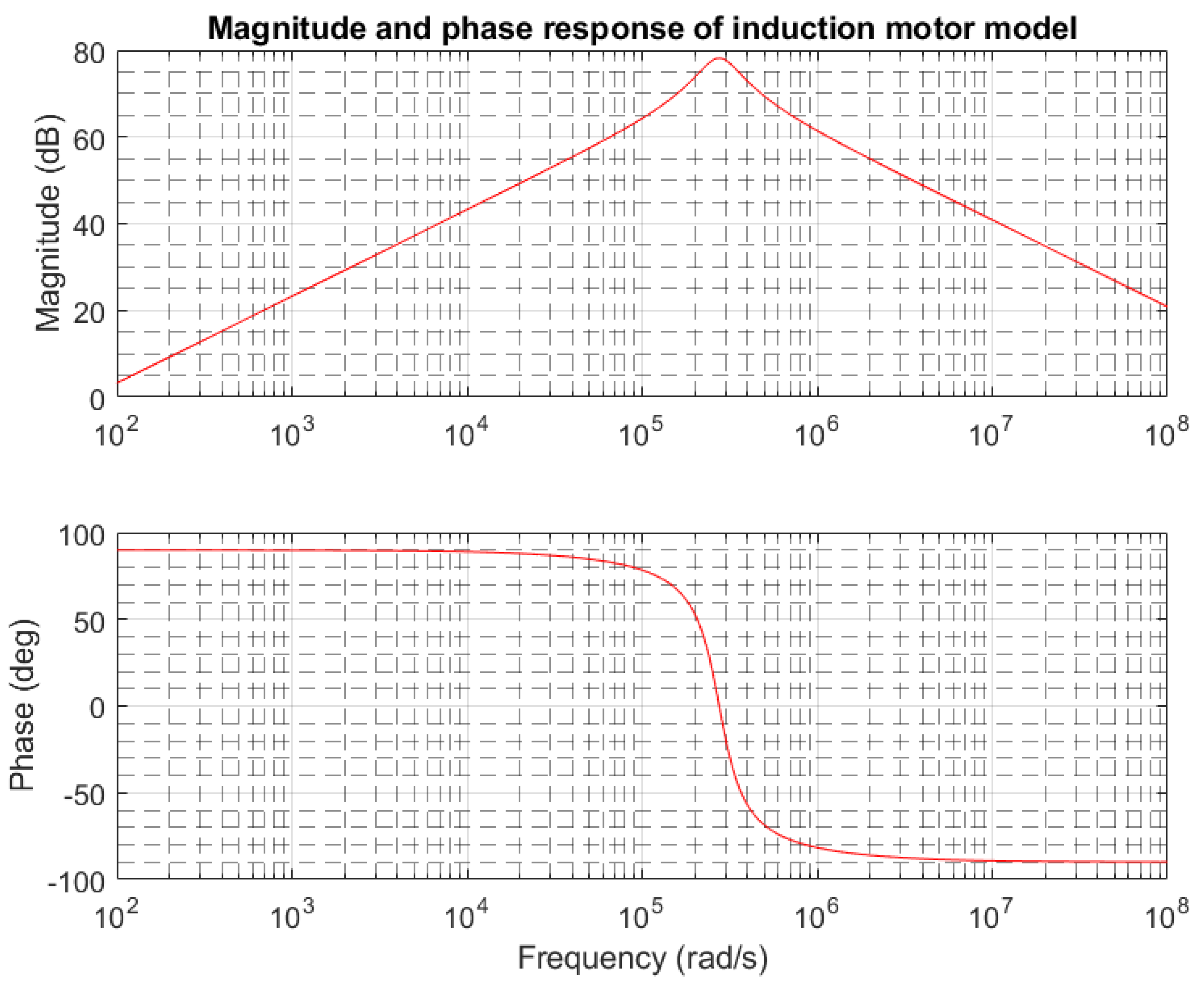

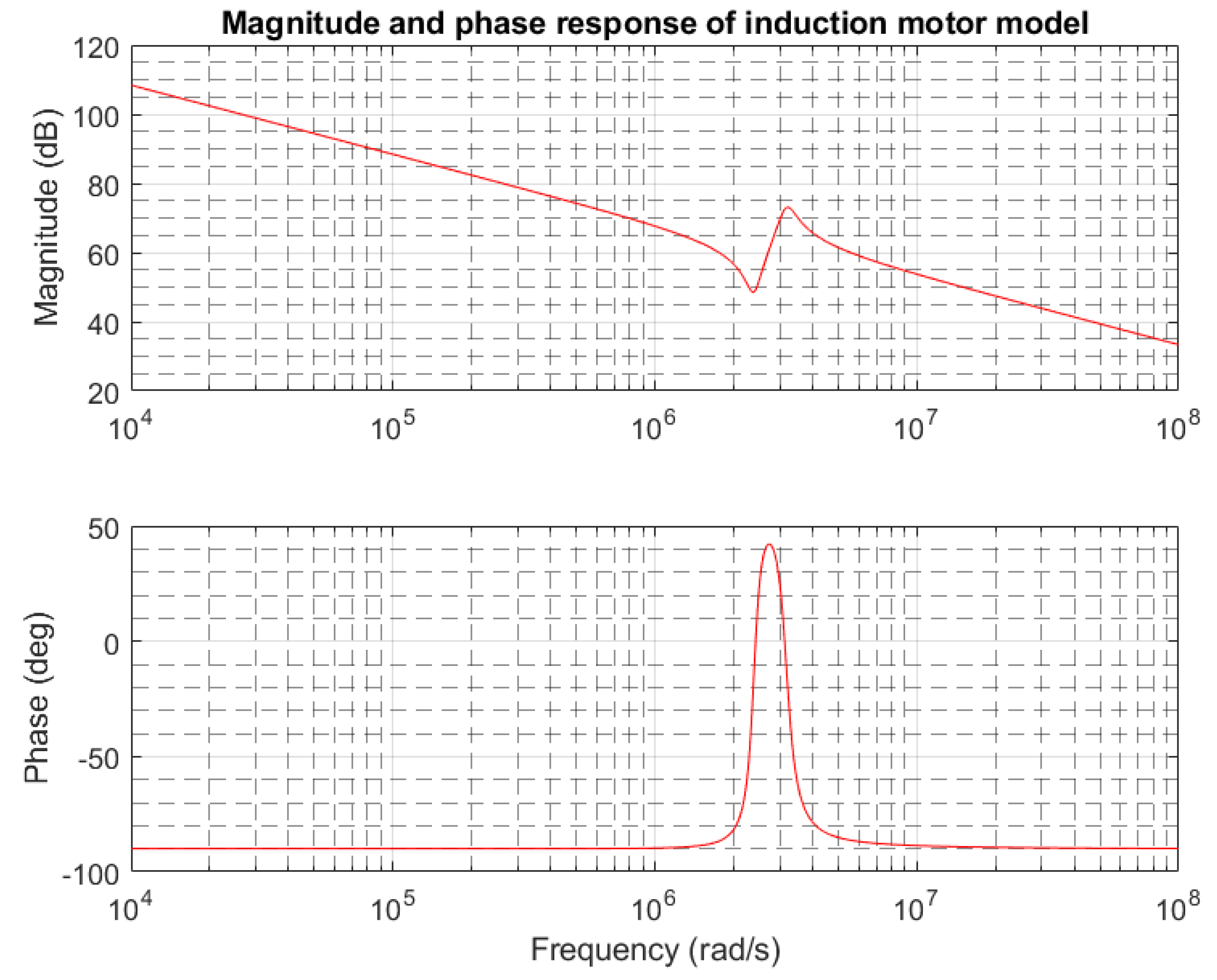

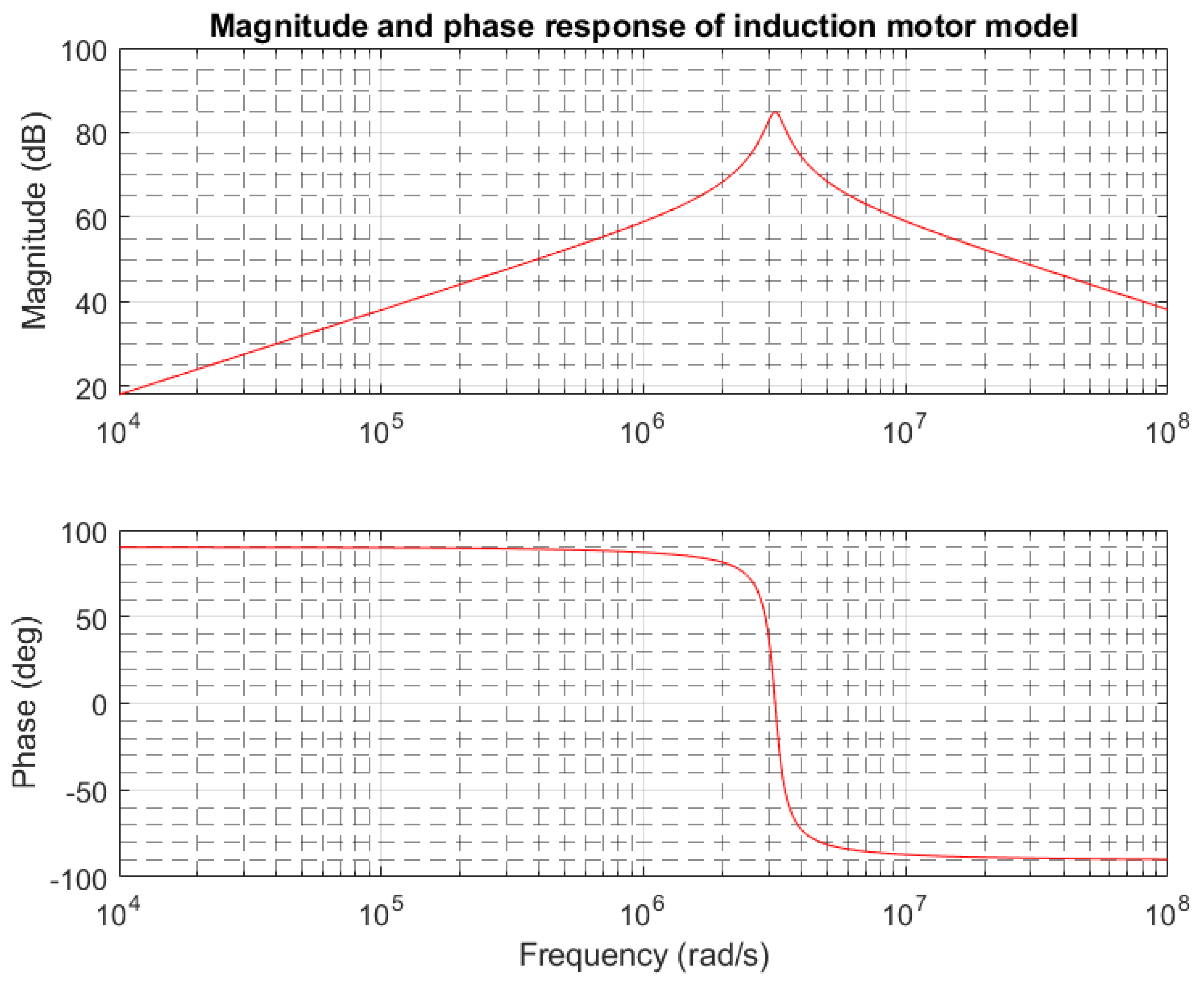

- Analyze common mode and differential mode impedance (magnitude and phase) frequency response bode plots of high frequency induction motors.

2. Materials and Methods

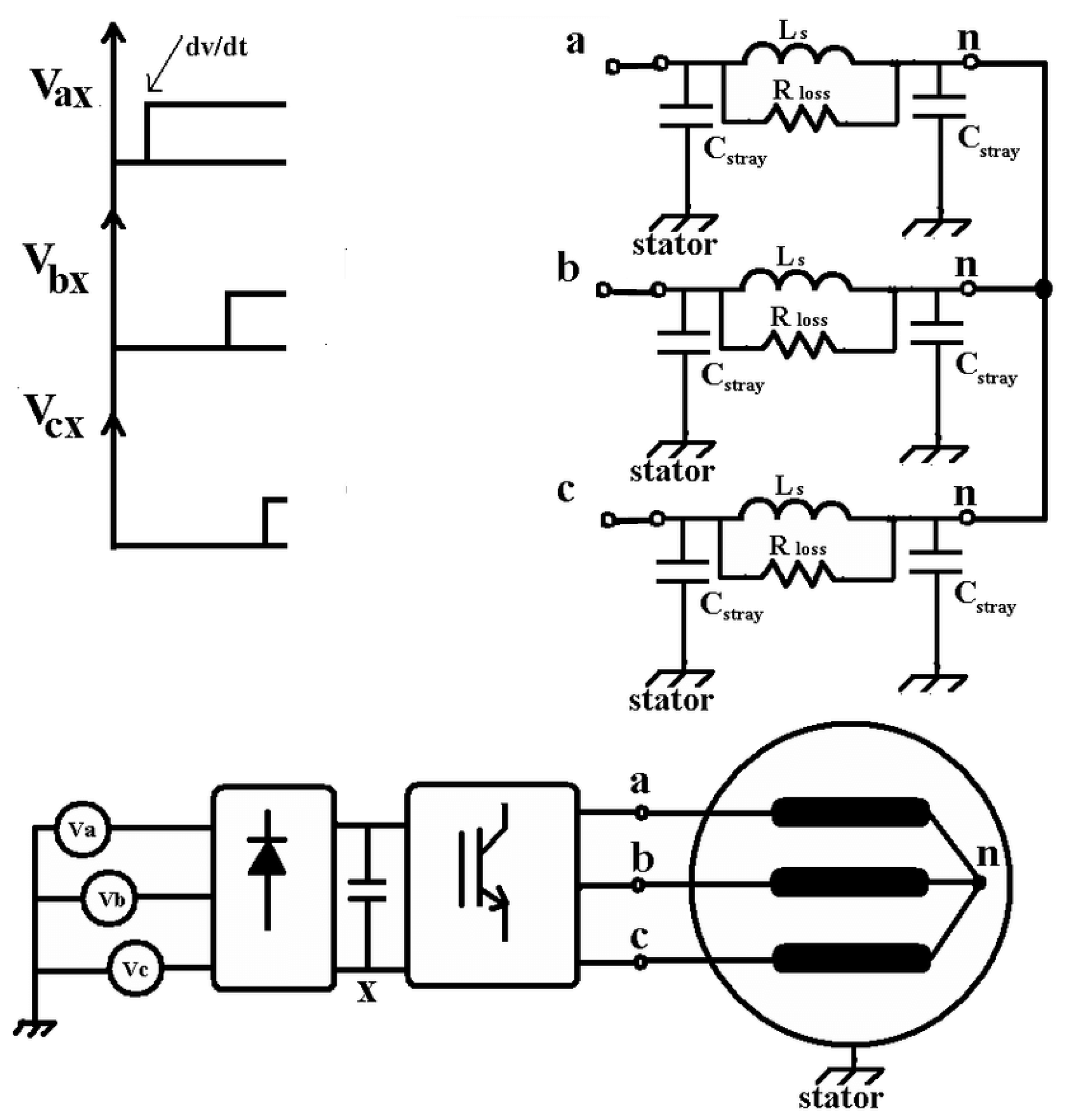

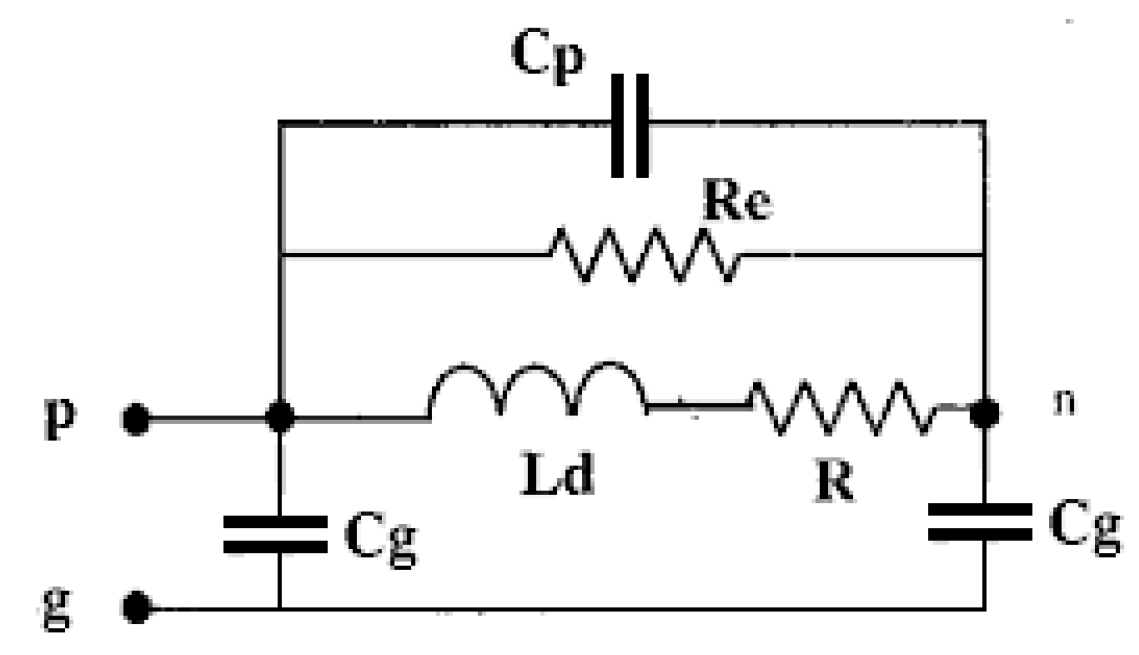

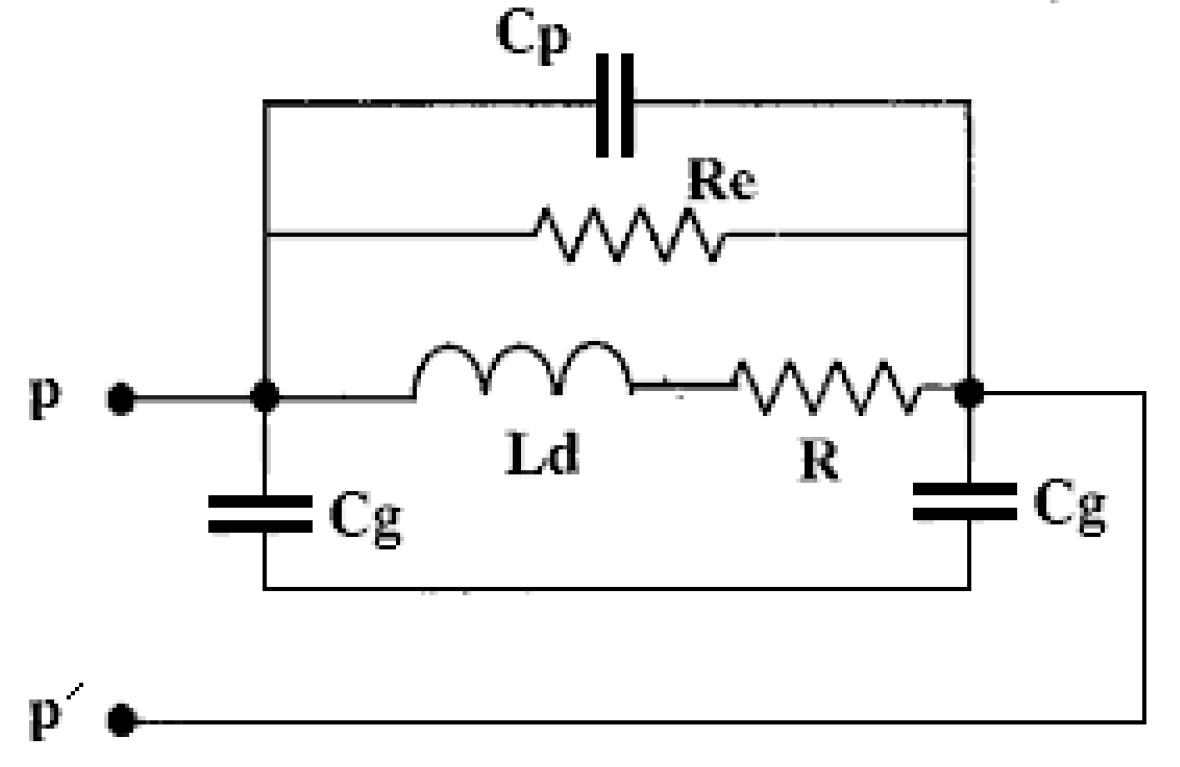

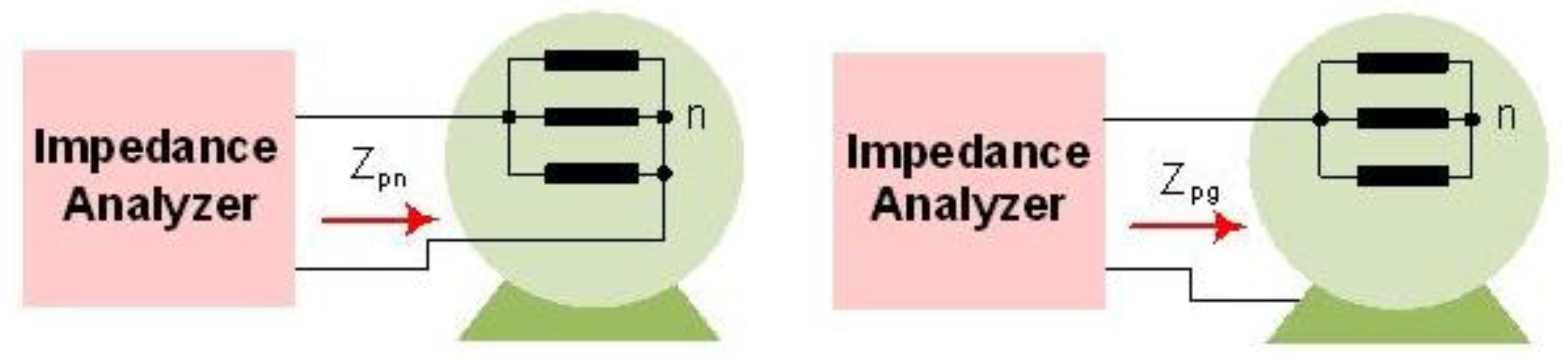

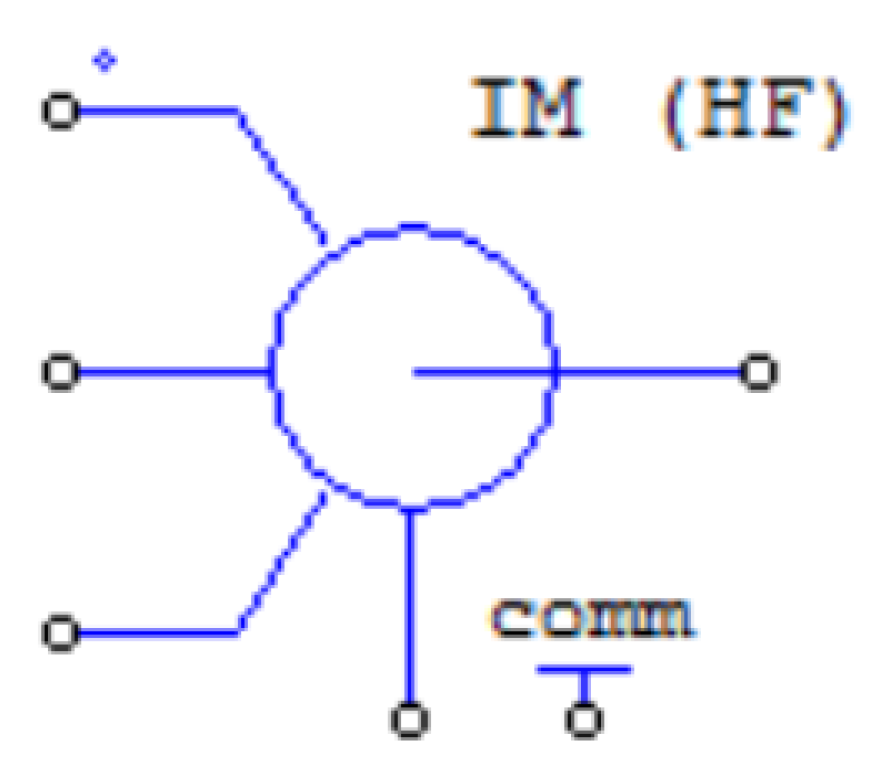

2.1. High Frequency Model for Induction Motor

2. Simulation of High Frequency Induction Motor Drive

- Rs: Stator Resistance;

- Ls: Stator winding leakage inductance;

- Rr: Rotor winding resistance with respect to stator side;

- Lr: Rotor winding leakage inductance with respect to stator side;

- Lm: Magnetizing inductance;

- P: Total number of poles;

- J: Moment of inertia

- Cg: Winding to ground capacitance;

- Rg: Resistance due to motor frame;

- Re: Eddy current resistance in the motor core;

- Rt: Skin effect resistance at high-frequency;

- Lt: Skin effect inductance at high-frequency;

- Ct: Skin effect capacitance at high frequency;

3. Results and Discussion

4. Discussion of High Frequency IM Impedance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, Z.; Jiang, D.; Zou, T.; Qu, R. Dual-Segment Three-Phase PMSM with Dual Inverters for Leakage Current and Common-Mode EMI Reduction. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 5606–5619. [CrossRef]

- Mazurck, P.; Michalski, A.; Swiatck, H.; Mazzetti, C.; Flisowski, Z. Hazard for insulation and relevant emc problems due to voltages in circuits of motor supply by pwm converters. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE Bologna Power Tech Conference Proceedings, Bologna, Italy, 23–26 June 2003; Volume 2, pp. 728–732.

- Ferreira, F.J.; Trovão, J.P.; De Almeida, A.T. Motor bearings and insulation system condition diagnosis by means of common-mode currents and shaft-ground voltage correlation. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Electrical Machines, ICEM’08, Vilamoura, Portugal, 6–9 September 2008; pp. 1–6.

- Spadacini, G.; Grassi, F.; Pignari, S.A. Conducted emissions in the powertrain of electric vehicles. IEEE Int. Symp. Electromagn. Compat. 2017, 69, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Robles, E.; Fernandez, M.; Andreu, J.; Ibarra, E.; Ugalde, U. Advanced power inverter topologies and modulation techniques for common-mode voltage elimination in electric motor drive systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110746. [CrossRef]

- Plazenet, T.; Boileau, T.; Caironi, C.; Nahid-Mobarakeh, B. An overview of shaft voltages and bearing currents in rotating machines. In Proceedings of the IEEE Industry Application Society, 52nd Annual Meeting: IAS 2016, Portland, OR, USA, 2–6 October 2016; pp. 1–8.

- Zare, F. Practical approach to model electric motors for electromagnetic interference and shaft voltage analysis. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2010, 4, 727–738. [CrossRef]

- Miloudi, H.; Bendaoud, A.; Miloudi, M.; Dickmann, S.; Schenke, S. Common mode and differential mode characteristics of AC motor for EMC analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Wroclaw, Poland, 5–9 September 2016; pp. 765–769.

- Lee, S.; Liu, M.; Lee, W.; Sarlioglu, B. Comparison of High-Frequency Impedance of AC Machines with Circumferential and Toroidal Winding Topologies for SiC MOSFET Machine Drives. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Detroit, MI, USA, 11–15 October 2020; pp. 3572–3579.

- Xiong, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X. A high-frequency motor model constructed based on vector fitting method. In Proceedings of the 2019 Joint International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Sapporo and Asia-Pacific International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, EMC Sapporo/APEMC 2019, Sapporo, Japan, 3–7 June 2019; pp. 191–194.

- Xiong, Y.; Chen, X.; Zong, L.; Li, X.; Nie, X.; Yang, G.; Zhao, X. An Electric Drive System Modelling Method Based on Module Behavior. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Microwave and Millimeter Wave Technology, ICMMT 2019—Proceedings, Guangzhou, China, 19–22 May 2019; pp. 1–3.

- Gries, M.A.; Mirafzal, B. Permanent magnet motor-drive frequency response characterization for transient phenomena and conducted EMI analysis. In Proceedings of the 2008 Twenty-Third Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, Austin, TX, USA, 24–28 February 2008; pp. 1767–1775.

- Schinkel, M.; Weber, S.; Guttowski, S.; John, W.; Reichl, H. Efficient HF Modeling and Model Parameterization of Induction Machines for Time and Frequency Domain Simulations. In Proceedings of the Twenty-First Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, 2006. APEC ’06, Dallas, TX, USA, 19–23 March 2006; Volume 2006, pp. 1181–1186.

- Zhang, D.; Kong, L.; Wen, X. High frequency model of interior permanent magnet motor for EMI analysis. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference and Expo Transportation Electrification Asia-Pacific (ITEC Asia-Pacific), Beijing, China, 31 August–3 September 2014; pp. 1–6.

- Radja, N.; Rachek, M.; Larbi, S.N. Improved RLMC-Circuit HF-Dependent Parameters Using FE-EM Computation Dedicated to Predict Fast Transient Voltage Along Insulated Windings. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2019, 61, 301–308. [CrossRef]

- Magdun, O.; Binder, A.; Purcarea, C.; Rocks, A. High-frequency induction machine models for calculation and prediction of common mode stator ground currents in electric drive systems. In Proceedings of the 2009 13th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications, EPE ’09, Barcelona, Spain, 8–10 September 2009; pp. 1–8.

- Heidler, B.; Brune, K.; Doppelbauer, M. High-frequency model and parameter identification of electrical machines using numerical simulations. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference (IEMDC), Coeur d’Alene, ID, USA, 10–13 May 2015; pp. 1221–1227.

- Mohammed, O.A.; Ganu, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z.; Abed, N. Study of high frequency model of permanent magnet motor. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Electric Machines and Drives, San Antonio, TX, USA, 15 May 2005; pp. 622–627.

- Jaritz, M.; Jaeger, C.; Bucher, M.; Smajic, J.; Vukovic, D.; Blume, S. An Improved Model for Circulating Bearing Currents in Inverter-Fed AC Machines. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 13–15 February 2019; pp. 225–230.

- De Gersem, H.; Henze, O.; Weiland, T.; Binder, A. Transmission-line modelling of wave propagation effects in machine windings. In Proceedings of the 2008 13th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, Poznan, Poland, 1–3 September 2008; pp. 2385–2392.

- Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Gao, C.; Wang, S.; Qiu, J.; Zhu, J.G.; Guo, Y. Analysis of inter-turn insulation of high voltage electrical machine by using multi-conductor transmission line model. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 1905–1908. [CrossRef]

- Sarrio, J.E.R.; Martis, C.; Chauvicourt, F. Numerical Computation of Parasitic Slot Capacitances in Electrical Machines. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference and Exposition on Electrical And Power Engineering (EPE), Iasi, Romania, 22–23 October 2020; pp. 146–150.

- Birnkammer, F.; Chen, J.; Pinhal, D.B.; Gerling, D. Influence of the Modeling Depth and Voltage Level on the AC Losses in Parallel Conductors of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2018, 28, 1–5.

- Ruiz-Sarrio, J.E.; Chauvicourt, F.; Gyselinck, J.; Martis, C. High-Frequency Modelling of Electrical Machine Windings Using Numerical Methods. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference (IEMDC), Hartford, CT, USA, 17–20 May 2021; pp. 1–7. [CrossRef.

- Vidmar, G.; Miljavec, D. A Universal High-Frequency Three-Phase Electric-Motor Model Suitable for the Delta- and Star-Winding Connections. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 4365–4376. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Rostam, M.; Shahabi, M.; Shayegani-Akmal, A.A. High frequency lumped parameter model for EMI problems and over voltage analysis of Induction motor. J. Electr. Eng. 2013, 13, 278–283.

- Gavrilenko, V.; Gavrilenko, V. Characterization of Winding Insulation of Electrical Machines Fed by Voltage Waves with High dV/dt. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paris-Saclay, Université polytechnique de Tomsk (Russie), Gif-sur-Yvette, France, 2020.

- Wu, Y.; Bi, C.; Jia, K.; Jin, D.; Li, H.; Yao, W.; Liu, G. High-frequency modelling of permanent magnet synchronous motor with star connection. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2018, 12, 539–546.

- Volpe, G.; Popescu, M.; Marignetti, F.; Goss, J. AC winding losses in automotive traction e-machines: A new hybrid calculation method. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference, IEMDC 2019, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–15 May 2019; pp. 2115–2119.

- Toulabi, M.S.; Wang, L.; Bieber, L.; Filizadeh, S.; Jatskevich, J. A Universal High-Frequency Induction Machine Model and Characterization Method for Arbitrary Stator Winding Connections. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2019, 34, 1164–1177. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Monge, J. Bordonau, D. Boroyevich, and S. Somavilla, “The nearest three virtual space vector PWM—A modulation for the comprehensive neutral point balancing in the three-level NPC inverter,” IEEE Power Electron. Lett., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 11–15, Mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Rachev, and L. Dimitrov, Study on electric vehicle induction motor drive. Proceedings of 13th International Conference ‘Research and Development in Mechanical Industry’ RaDMI 2013, Kopaonik, Serbia, 2013, vol. 2, pp. 920–926. ISBN 978-86-6075-043-5.

- Cho, K. R., & Seok, J. K. (2009). Induction motor rotor temperature estimation based on a high-frequency model of a rotor bar. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 45(4), 1267-1275.

- Vahedi, H., Sheikholeslami, A., Tavakoli Bina, M., & Vahedi, M. (2011). Review and simulation of fixed and adaptive hysteresis current control considering switching losses and high-frequency harmonics. Advances in power electronics, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Buso, S., Fasolo, S., Malesani, L., & Mattavelli, P. (2000). A dead-beat adaptive hysteresis current control. IEEE Transactions on industry applications, 36(4), 1174-1180.

- Amin, M. M., & Mohammed, O. A. (2011, September). A three-phase high frequency semi-controlled battery charging power converter for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. In 2011 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (pp. 2641-2648). IEEE.

- Kar, C., & Mohanty, A. R. (2008). Vibration and current transient monitoring for gearbox fault detection using multiresolution Fourier transform. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 311(1-2), 109-132.

- Raj, R. A., Shreelakshmi, M. P., & George, S. (2020, December). Multiband Hysteresis Current Controller for Three Level BLDC Motor Drive. In 2020 International Conference on Power, Instrumentation, Control and Computing (PICC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Ben Salem, F., & Feki, M. (2019). An Improved DTC Induction Motor for Electric Vehicle Propulsion: An Intention to Provide a Comfortable Ride. Solving Transport Problems: Towards Green Logistics, 185-201.

- Choudhury, A., Pillay, P., & Williamson, S. S. (2014). DC-link voltage balancing for a three-level electric vehicle traction inverter using an innovative switching sequence control scheme. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics, 2(2), 296-307. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Fan, F., Sun, Q., Tu, P., & See, K. Y. (2022, September). High-frequency modeling of induction motor using multilayer perceptron. In 2022 Asia-Pacific International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility (APEMC) (pp. 222-224). IEEE.

- Mohammadi-Rostam, M., & Shahabi, M. (2016). Modeling induction motor for prediction of high frequency problems. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Electrical Engineering, 40, 13-22.

- Mohammadi-Rostam, M., Shahabi, M., & Shayegani-Akmal, A. A. (2013). High frequency lumped parameter model for EMI problems and over voltage analysis of Induction motor. J. Electr. Eng, 13, 278-283.

- Degano, M., Zanchetta, P., Clare, J., & Empringham, L. (2010, July). HF induction motor modeling using genetic algorithms and experimental impedance measurement. In 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (pp. 1296-1301). IEEE.

- Cacciato, M., Consoli, A., Finocchiaro, L., & Testa, A. (2005, September). High frequency modeling of bearing currents and shaft voltage on electrical motors. In 2005 International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (Vol. 3, pp. 2065-2070). IEEE.

- Zare, F. (2008). High frequency model of an electric motor based on measurement results. Australian Journal of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, 4(1), 17-24.

- Ocak, H., & Loparo, K. A. (2004). Estimation of the running speed and bearing defect frequencies of an induction motor from vibration data. Mechanical systems and signal processing, 18(3), 515-533. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Fan, F., Sun, Q., Tu, P., & See, K. Y. (2022). High-Frequency Modeling of Star-Connected Induction Motors Using Multilayer Perceptron.

- Miloudi, H., Miloudi, M., Gourbi, A., Bermaki, M. H., Bendaoud, A., & Zeghoudi, A. (2022). A high-frequency modeling of AC motor in a frequency range from 40 Hz to 110 MHz. Electrical Engineering & Electromechanics, (6), 3-7.

- Degano, M., Zanchetta, P., Empringham, L., Lavopa, E., & Clare, J. (2012). HF induction motor modeling using automated experimental impedance measurement matching. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 59(10), 3789-3796. [CrossRef]

- Magdun, O., & Binder, A. (2013). High-frequency induction machine modeling for common mode current and bearing voltage calculation. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 50(3), 1780-1790.

- Karakaşlı, V., Gross, F., Braun, T., De Gersem, H., & Griepentrog, G. (2022). High-frequency modeling of delta-and star-connected induction motors. IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility, 64(5), 1533-1544.

- Mirafzal, B., Skibinski, G. L., Tallam, R. M., Schlegel, D. W., & Lukaszewski, R. A. (2007). Universal induction motor model with low-to-high frequency-response characteristics. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 43(5), 1233-1246.

- Jia, K., Bohlin, G., Enohnyaket, M., & Thottappillil, R. (2013). Modelling an AC motor with high accuracy in a wide frequency range. IET Electric Power Applications, 7(2), 116-122. [CrossRef]

- Boglietti, A., Cavagnino, A., & Lazzari, M. (2007). Experimental high-frequency parameter identification of AC electrical motors. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 43(1), 23-29.

- Riehl, R. R., & Ruppert Filho, E. (2007, October). A simplified method for determining the high frequency induction motor equivalent electrical circuit parameters to be used in EMI effect. In 2007 International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS) (pp. 1244-1248). IEEE.

- Ryu, Y., Park, B. R., & Han, K. J. (2015). Estimation of high-frequency parameters of AC machine from transmission line model. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, 51(3), 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, H., Imdad, K., Chaudhry, M. U., Iqbal, M. M., Bolshev, V., Hussain, A., ... & Jasiński, M. (2022). Electric Vehicle Transient Speed Control Based on Vector Control FM-PI Speed Controller for Induction Motor. Applied Sciences, 12(17), 8694. [CrossRef]

- Zare, F. (2006, November). Modelling of electric motors for electromagnetic compatibility analysis. In AUPEC 2006.

- Miloudi, H., Bendaoud, A., Miloudi, M., Dickmann, S., & Schenke, S. (2016, September). Common mode and differential mode characteristics of AC motor for EMC analysis. In 2016 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility-EMC EUROPE (pp. 765-769). IEEE.

| Symbol | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Rs | Stator resistance | 0.087 |

| Ls | Stator leakage inductance | 0.8m |

| Rr | Rotor resistance | 0.227 |

| Lr | Rotor leakage inductance | 0.8m |

| Lm | Magnetizing inductance | 34.7m |

| P | No of poles | 4 |

| J | Moment of inertia | 1.662 |

| Cg | Winding to ground capacitance | 190p |

| Rg | Resistance due to motor frame | 1000k |

| Re | Eddy current resistance | 17.49k |

| Rt | Skin effect resistance | 0.324k |

| Lt | Skin effect inductance | 0.27m |

| Ct | Skin effect capacitance | 29p |

| Le | IGBT’s Emitter parasitic inductance | 7.5 nH |

| Cch | Stray capacitance among collector and ground of IGBT | 0.1 nF |

| M | Master/Slave mode | 1 |

| Symbol | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cg | Winding to turn distributive coupling capacitance | 0.125e-8 F |

| Cp | Turn to turn distributive coupling capacitance | 2.8221e-10 F |

| L | Phase Leakage Inductance | 0.0145 H |

| R | Stator Winding Resistance | 8.1242e+03 Ω |

| Re | Eddy current resistance inside magnetic core and motor frame | 5 Ω |

| Symbol | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cg | Winding to turn distributive coupling capacitance | 190e-12 F |

| Cp | Turn to turn distributive coupling capacitance | 29e-12 F |

| L | Phase Leakage Inductance | 0.8e-03 H |

| R | Stator Winding Resistance | 17.49e+03 Ω |

| Re | Eddy current resistance inside magnetic core and motor frame | 0.324e+3 Ω |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).