Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

28 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

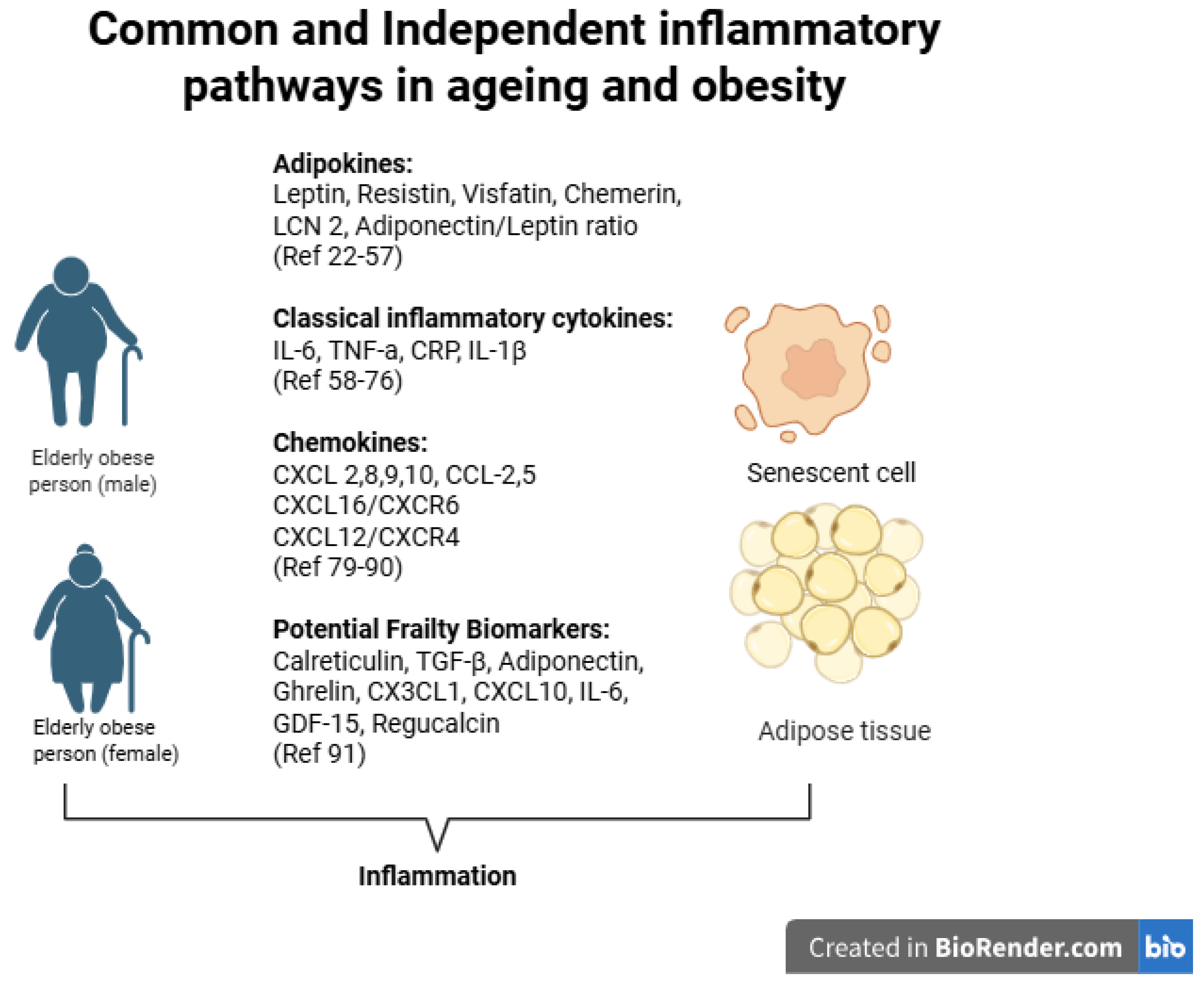

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Changes of Adipose Tissue During Aging

4. Plasma Visfatin Levels in Obesity and Ageing

5. Leptin

6. Retinol Binding Protein 4 (RBP4) in Obesity and Aging

7. Chemerin in Obesity and Ageing

8. Resistin in Obesity and Ageing

9. Lipocalin 2 in Obesity and Ageing

10. TNF-a, IL-1β and IL-6 in Obesity and Ageing

11. CRP Levels in Obesity and Ageing

12. The Role of Chemokines in Obesity and Ageing

13. Conclusions

References

- Obesity and overweight [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- World Population Ageing 2019.

- Aune D, Sen A, Prasad M, Norat T, Janszky I, Tonstad S, et al. BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. BMJ. 2016 May 4;353:i2156. [CrossRef]

- Khanna D, Khanna S, Khanna P, Kahar P, Patel BM. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus. 2022 Feb;14(2):e22711. [CrossRef]

- Trim WV, Walhin JP, Koumanov F, Bouloumié A, Lindsay MA, Chen YC, et al. Divergent immunometabolic changes in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle with ageing in healthy humans. The Journal of Physiology. 2022;600(4):921–47.

- Tam BT, Morais JA, Santosa S. Obesity and ageing: Two sides of the same coin. Obes Rev. 2020 Apr;21(4):e12991. [CrossRef]

- Pérez LM, Pareja-Galeano H, Sanchis-Gomar F, Emanuele E, Lucia A, Gálvez BG. ‘Adipaging’: ageing and obesity share biological hallmarks related to a dysfunctional adipose tissue. J Physiol. 2016 June 15;594(12):3187–207. [CrossRef]

- Schosserer M, Grillari J, Wolfrum C, Scheideler M. Age-Induced Changes in White, Brite, and Brown Adipose Depots: A Mini-Review. Gerontology. 2017 Dec 7;64(3):229–36. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Farias M, Fos-Domenech J, Serra D, Herrero L, Sánchez-Infantes D. White adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity and aging. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021 Oct;192:114723. [CrossRef]

- Cinti S. The adipose organ at a glance. Dis Model Mech. 2012 Sept;5(5):588–94. [CrossRef]

- Antoniades C, Tousoulis D, Vavlukis M, Fleming I, Duncker DJ, Eringa E, et al. Perivascular adipose tissue as a source of therapeutic targets and clinical biomarkers. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 12;44(38):3827–44. [CrossRef]

- Kuk JL, Saunders TJ, Davidson LE, Ross R. Age-related changes in total and regional fat distribution. Ageing Research Reviews. 2009 Oct 1;8(4):339–48. [CrossRef]

- Tchkonia T, Morbeck DE, Von Zglinicki T, Van Deursen J, Lustgarten J, Scrable H, et al. Fat tissue, aging, and cellular senescence. Aging Cell. 2010 Oct;9(5):667–84. [CrossRef]

- Srikakulapu P, McNamara CA. B Lymphocytes and Adipose Tissue Inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2020 May;40(5):1110–22. [CrossRef]

- Pfannenberg C, Werner MK, Ripkens S, Stef I, Deckert A, Schmadl M, et al. Impact of Age on the Relationships of Brown Adipose Tissue With Sex and Adiposity in Humans. Diabetes. 2010 Apr 27;59(7):1789–93. [CrossRef]

- Zoico E, Rubele S, De Caro A, Nori N, Mazzali G, Fantin F, et al. Brown and Beige Adipose Tissue and Aging. Front Endocrinol [Internet]. 2019 June 20 [cited 2025 Apr 27];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.orghttps://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2019.00368/full. [CrossRef]

- Villarroya F, Cereijo R, Gavaldà-Navarro A, Villarroya J, Giralt M. Inflammation of brown/beige adipose tissues in obesity and metabolic disease. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2018;284(5):492–504. [CrossRef]

- Hirata Y, Tabata M, Kurobe H, Motoki T, Akaike M, Nishio C, et al. Coronary Atherosclerosis Is Associated With Macrophage Polarization in Epicardial Adipose Tissue. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011 July 12;58(3):248–55. [CrossRef]

- Menzel A, Samouda H, Dohet F, Loap S, Ellulu MS, Bohn T. Common and Novel Markers for Measuring Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Ex Vivo in Research and Clinical Practice—Which to Use Regarding Disease Outcomes? Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Mar 9;10(3):414.

- Savulescu-Fiedler I, Mihalcea R, Dragosloveanu S, Scheau C, Baz RO, Caruntu A, et al. The Interplay between Obesity and Inflammation. Life. 2024 July;14(7):856.

- Spray L, Richardson G, Haendeler J, Altschmied J, Rumampouw V, Wallis SB, et al. Cardiovascular inflammaging: Mechanisms, consequences, and therapeutic perspectives. Cell Reports Medicine [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 17]. [CrossRef]

- Curat CA, Wegner V, Sengenès C, Miranville A, Tonus C, Busse R, et al. Macrophages in human visceral adipose tissue: increased accumulation in obesity and a source of resistin and visfatin. Diabetologia. 2006 Apr 1;49(4):744–7. [CrossRef]

- Skoczylas A. [The role of visfatin in the pathophysiology of human]. Wiad Lek. 2009;62(3):190–6.

- Kamińska A, Kopczyńska E, Bronisz A, Żmudzińska M, Bieliński M, Borkowska A, et al. An evaluation of visfatin levels in obese subjects. Endokrynologia Polska. 2010;61(2):169–73.

- Pagano C, Pilon C, Olivieri M, Mason P, Fabris R, Serra R, et al. Reduced Plasma Visfatin/Pre-B Cell Colony-Enhancing Factor in Obesity Is Not Related to Insulin Resistance in Humans. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006 Aug 1;91(8):3165–70. [CrossRef]

- Jurdana M, Petelin A, Černelič Bizjak M, Bizjak M, Biolo G, Jenko-Pražnikar Z. Increased serum visfatin levels in obesity and its association with anthropometric/biochemical parameters, physical inactivity and nutrition. e-SPEN Journal. 2013 Apr 1;8(2):e59–67. [CrossRef]

- Haider DG, Schindler K, Schaller G, Prager G, Wolzt M, Ludvik B. Increased Plasma Visfatin Concentrations in Morbidly Obese Subjects Are Reduced after Gastric Banding. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006 Apr 1;91(4):1578–81. [CrossRef]

- García-Fuentes E, García-Almeida JM, García-Arnés J, García-Serrano S, Rivas-Marín J, Gallego-Perales JL, et al. Plasma Visfatin Concentrations in Severely Obese Subjects Are Increased After Intestinal Bypass. Obesity. 2007;15(10):2391–5. [CrossRef]

- Berndt J, Klöting N, Kralisch S, Kovacs P, Fasshauer M, Schön MR, et al. Plasma Visfatin Concentrations and Fat Depot–Specific mRNA Expression in Humans. Diabetes. 2005 Oct 1;54(10):2911–6.

- de Luis DA, Gonzalez Sagrado M, Conde R, Aller R, Izaola O, Romero E. Effect of a hypocaloric diet on serum visfatin in obese non-diabetic patients. Nutrition. 2008 June 1;24(6):517–21. [CrossRef]

- Farr OM, Gavrieli A, Mantzoros CS. Leptin applications in 2015: what have we learned about leptin and obesity? Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2015 Oct;22(5):353.

- Obradovic M, Sudar-Milovanovic E, Soskic S, Essack M, Arya S, Stewart AJ, et al. Leptin and Obesity: Role and Clinical Implication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021 May 18;12:585887.

- Faggioni R, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Leptin regulation of the immune response and the immunodeficiency of malnutrition. The FASEB Journal. 2001;15(14):2565–71. [CrossRef]

- Myers MG, Heymsfield SB, Haft C, Kahn BB, Laughlin M, Leibel RL, et al. Challenges and opportunities of defining clinical leptin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012 Feb 8;15(2):150–6. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo AG, Crujeiras AB, Casanueva FF, Carreira MC. Leptin, Obesity, and Leptin Resistance: Where Are We 25 Years Later? Nutrients. 2019 Nov 8;11(11):2704. [CrossRef]

- La Cava A, Matarese G. The weight of leptin in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004 Dec;4(5):371–9. [CrossRef]

- Laule C, Rahmouni K. Leptin and Associated Neural Pathways Underlying Obesity-Induced Hypertension. Comprehensive Physiology. 2025;15(1):e8. [CrossRef]

- Zhuo Q, Wang Z, Fu P, Piao J, Tian Y, Xu J, et al. Comparison of adiponectin, leptin and leptin to adiponectin ratio as diagnostic marker for metabolic syndrome in older adults of Chinese major cities. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2009 Apr 1;84(1):27–33. [CrossRef]

- Rizza RA. Pathogenesis of fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: implications for therapy. Diabetes. 2010 Nov;59(11):2697–707. [CrossRef]

- Bik W, Baranowska-Bik A, Wolinska-Witort E, Kalisz M, Broczek K, Mossakowska M, et al. Assessment of adiponectin and its isoforms in Polish centenarians. Experimental Gerontology. 2013 Apr 1;48(4):401–7. [CrossRef]

- Moraes-Vieira PM, Yore MM, Dwyer PM, Syed I, Aryal P, Kahn BB. RBP4 Activates Antigen-Presenting Cells, Leading to Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Systemic Insulin Resistance. Cell Metabolism. 2014 Mar 4;19(3):512–26.

- Lambadiari V, Kadoglou NP, Stasinos V, Maratou E, Antoniadis A, Kolokathis F, et al. Serum levels of retinol-binding protein-4 are associated with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014 Dec;13(1):121. [CrossRef]

- Ingelsson E, Lind L. Circulating Retinol-Binding Protein 4 and Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly. Diabetes Care. 2009 Apr 1;32(4):733–5. [CrossRef]

- Zabetian-Targhi F, Mahmoudi MJ, Rezaei N, Mahmoudi M. Retinol Binding Protein 4 in Relation to Diet, Inflammation, Immunity, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Advances in Nutrition. 2015 Nov 1;6(6):748–62.

- Gavi S, Qurashi S, Stuart LM, Lau R, Melendez MM, Mynarcik DC, et al. Influence of age on the association of retinol-binding protein 4 with metabolic syndrome. Obesity. 2008;16(4):893–5. [CrossRef]

- Sell H, Laurencikiene J, Taube A, Eckardt K, Cramer A, Horrighs A, et al. Chemerin Is a Novel Adipocyte-Derived Factor Inducing Insulin Resistance in Primary Human Skeletal Muscle Cells. Diabetes. 2009 Dec;58(12):2731–40. [CrossRef]

- Ernst MC, Issa M, Goralski KB, Sinal CJ. Chemerin Exacerbates Glucose Intolerance in Mouse Models of Obesity and Diabetes. Endocrinology. 2010 May 1;151(5):1998–2007. [CrossRef]

- Coimbra S, Brandão Proença J, Santos-Silva A, Neuparth MJ. Adiponectin, Leptin, and Chemerin in Elderly Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Close Linkage with Obesity and Length of the Disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:701915. [CrossRef]

- Aronis KN, Sahin-Efe A, Chamberland JP, Spiro A, Vokonas P, Mantzoros CS. Chemerin levels as predictor of acute coronary events: A case–control study nested within the veterans affairs normative aging study. Metabolism. 2014 June;63(6):760–6. [CrossRef]

- Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, Brown EJ, Banerjee RR, Wright CM, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001 Jan 18;409(6818):307–12.

- Gencer B, Auer R, de Rekeneire N, Butler J, Kalogeropoulos A, Bauer DC, et al. Association between resistin levels and cardiovascular disease events in older adults: The health, aging and body composition study. Atherosclerosis. 2016 Feb;245:181–6. [CrossRef]

- Ohmori R, Momiyama Y, Kato R, Taniguchi H, Ogura M, Ayaori M, et al. Associations between serum resistin levels and insulin resistance, inflammation, and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 July 19;46(2):379–80. [CrossRef]

- Krizanac M, Mass Sanchez PB, Weiskirchen R, Asimakopoulos A. A Scoping Review on Lipocalin-2 and Its Role in Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021 Jan;22(6):2865. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Zhang Q, Zhao X, Dong G, Li C. Diagnostic and prognostic value of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, matrix metalloproteinase-9, and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1 for sepsis in the Emergency Department: an observational study. Critical Care. 2014 Nov 19;18(6):634. [CrossRef]

- Abella V, Scotece M, Conde J, Gómez R, Lois A, Pino J, et al. The potential of lipocalin-2/NGAL as biomarker for inflammatory and metabolic diseases. Biomarkers. 2015 Nov 17;20(8):565–71. [CrossRef]

- Daoud MS, Alshareef FH, Alnaami AM, Amer OE, Hussain SD, Al-Daghri NM. Prospective changes in lipocalin-2 and adipocytokines among adults with obesity. Sci Rep. 2025 Aug 6;15(1):28794. [CrossRef]

- Lögdberg L, Wester L. Immunocalins: a lipocalin subfamily that modulates immune and inflammatory responses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000 Oct 18;1482(1–2):284–97. [CrossRef]

- Auguet T, Quintero Y, Terra X, Martínez S, Lucas A, Pellitero S, et al. Upregulation of lipocalin 2 in adipose tissues of severely obese women: positive relationship with proinflammatory cytokines. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011 Dec;19(12):2295–300. [CrossRef]

- Law IKM, Xu A, Lam KSL, Berger T, Mak TW, Vanhoutte PM, et al. Lipocalin-2 Deficiency Attenuates Insulin Resistance Associated With Aging and Obesity. Diabetes. 2010 Apr;59(4):872–82. [CrossRef]

- Oh SJ, Lee JK, Shin OS. Aging and the Immune System: the Impact of Immunosenescence on Viral Infection, Immunity and Vaccine Immunogenicity. Immune Netw. 2019 Nov 14;19(6):e37. [CrossRef]

- Tylutka A, Walas Ł, Zembron-Lacny A. Level of IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β and age-related diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024 Mar 1;15. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Rodríguez L, López-Hoyos M, Muñoz-Cacho P, Martínez-Taboada VM. Aging is associated with circulating cytokine dysregulation. Cellular Immunology. 2012 Jan 1;273(2):124–32.

- Milan-Mattos JC, Anibal FF, Perseguini NM, Minatel V, Rehder-Santos P, Castro CA, et al. Effects of natural aging and gender on pro-inflammatory markers. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2019;52:e8392. [CrossRef]

- Silva RCMC. The dichotomic role of cytokines in aging. Biogerontology. 2024 Dec 2;26(1):17. [CrossRef]

- Ghanemi A, Yoshioka M, St-Amand J. Ageing and Obesity Shared Patterns: From Molecular Pathogenesis to Epigenetics. Diseases. 2021 Nov 29;9(4):87. [CrossRef]

- Lisko I, Tiainen K, Stenholm S, Luukkaala T, Hurme M, Lehtimäki T, et al. Inflammation, adiposity, and mortality in the oldest old. Rejuvenation Res. 2012 Oct;15(5):445–52.

- Tchkonia T, Morbeck DE, Von Zglinicki T, Van Deursen J, Lustgarten J, Scrable H, et al. Fat tissue, aging, and cellular senescence. Aging Cell. 2010 Oct;9(5):667–84.

- Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011 Feb;11(2):85–97. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Wang Q, Wang Y, Ma C, Zhao Q, Yin H, et al. Interleukin-6 promotes visceral adipose tissue accumulation during aging via inhibiting fat lipolysis. International Immunopharmacology. 2024 May 10;132:111906. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001 July 18;286(3):327–34.

- Mooney RA. Counterpoint: Interleukin-6 does not have a beneficial role in insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007 Feb;102(2):816–8; discussion 818-819.

- Gruver A, Hudson L, Sempowski G. Immunosenescence of ageing. The Journal of Pathology. 2007;211(2):144–56. [CrossRef]

- Salam N, Rane S, Das R, Faulkner M, Gund R, Kandpal U, et al. T cell ageing: Effects of age on development, survival & function. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2013 Nov;138(5):595.

- Lapice E, Maione S, Patti L, Cipriano P, Rivellese AA, Riccardi G, et al. Abdominal Adiposity Is Associated With Elevated C-Reactive Protein Independent of BMI in Healthy Nonobese People. Diabetes Care. 2009 Sept 1;32(9):1734–6. [CrossRef]

- Casas JP, Shah T, Hingorani AD, Danesh J, Pepys MB. C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease: a critical review. J Intern Med. 2008 Oct;264(4):295–314. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson WL, Koenig W, Fröhlich M, Sund M, Lowe GD, Pepys MB. Immunoradiometric assay of circulating C-reactive protein: age-related values in the adult general population. Clin Chem. 2000 July;46(7):934–8. [CrossRef]

- Direct Proinflammatory Effect of C-Reactive Protein on Human Endothelial Cells [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 17]. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/01.CIR.102.18.2165. [CrossRef]

- Kittel-Schneider S, Kaspar M, Berliner D, Weber H, Deckert J, Ertl G, et al. CRP genetic variants are associated with mortality and depressive symptoms in chronic heart failure patients. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2018 July;71:133–41. [CrossRef]

- Hughes CE, Nibbs RJB. A guide to chemokines and their receptors. FEBS J. 2018 Aug;285(16):2944–71.

- Xue W, Fan Z, Li L, Lu J, Zhai Y, Zhao J. The chemokine system and its role in obesity. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234(4):3336–46. [CrossRef]

- Kern PA, Saghizadeh M, Ong JM, Bosch RJ, Deem R, Simsolo RB. The expression of tumor necrosis factor in human adipose tissue. Regulation by obesity, weight loss, and relationship to lipoprotein lipase. J Clin Invest. 1995 May 1;95(5):2111–9. [CrossRef]

- He W, Wang H, Yang G, Zhu L, Liu X. The Role of Chemokines in Obesity and Exercise-Induced Weight Loss. Biomolecules. 2024 Sept 4;14(9):1121. [CrossRef]

- Bai Y, Sun Q. Macrophage recruitment in obese adipose tissue. Obes Rev. 2015 Feb;16(2):127–36. [CrossRef]

- Inouye KE, Shi H, Howard JK, Daly CH, Lord GM, Rollins BJ, et al. Absence of CC chemokine ligand 2 does not limit obesity-associated infiltration of macrophages into adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2007 Sept;56(9):2242–50. [CrossRef]

- Lee SC, Lee YJ, Choi I, Kim M, Sung JS. CXCL16/CXCR6 Axis in Adipocytes Differentiated from Human Adipose Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Regulates Macrophage Polarization. Cells. 2021 Dec 3;10(12):3410. [CrossRef]

- Kim D, Kim J, Yoon JH, Ghim J, Yea K, Song P, et al. CXCL12 secreted from adipose tissue recruits macrophages and induces insulin resistance in mice. Diabetologia. 2014 July;57(7):1456–65. [CrossRef]

- Moreno B, Hueso L, Ortega R, Benito E, Martínez-Hervas S, Peiro M, et al. Association of chemokines IP-10/CXCL10 and I-TAC/CXCL11 with insulin resistance and enhance leukocyte endothelial arrest in obesity. Microvasc Res. 2022 Jan;139:104254. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro SMTL, Lopes LR, Paula Costa G de, Figueiredo VP, Shrestha D, Batista AP, et al. CXCL-16, IL-17, and bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) are associated with overweight and obesity conditions in middle-aged and elderly women. Immunity & Ageing. 2017 Mar 11;14(1):6. [CrossRef]

- Bonfante H de L, Almeida C de S, Abramo C, Grunewald STF, Levy RA, Teixeira HC. CCL2, CXCL8, CXCL9 and CXCL10 serum levels increase with age but are not altered by treatment with hydroxychloroquine in patients with osteoarthritis of the knees. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017 Dec;20(12):1958–64.

- Sayed N, Huang Y, Nguyen K, Krejciova-Rajaniemi Z, Grawe AP, Gao T, et al. An inflammatory aging clock (iAge) based on deep learning tracks multimorbidity, immunosenescence, frailty and cardiovascular aging. Nat Aging. 2021 July;1:598–615. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso AL, Fernandes A, Aguilar-Pimentel JA, De Angelis MH, Guedes JR, Brito MA, et al. Towards frailty biomarkers: Candidates from genes and pathways regulated in aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Research Reviews. 2018 Nov;47:214–77. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary JK, Danga AK, Kumari A, Bhardwaj A, Rath PC. Role of chemokines in aging and age-related diseases. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2025 Feb 1;223:112009. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).