Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Museums, Museology, and Museum Objects

2.2. Digital Transformation in the Museum

2.3. Conservation and Digital Integration

3. Research Objectives and Methodology

3.1. Research Objectives

- 1)

- 2)

- 3)

3.2. Research Methodology

- Case Study Selection: The Eleusis re-exhibition was selected based on its recent completion, extensive conservation documentation, and institutional openness to digital innovation initiatives.

- Artifact Selection: Two culturally significant objects were chosen, the Inscription “Hierophant” and the statue of Antinous. These were selected for their documentation completeness, historical significance, and the diversity of conservation challenges they represent.

- Platform Comparison: Systematic evaluation of Synthesia (AI avatar video) versus Clipchamp (AI voiceover video) for museum content creation applications.

- Content Delivery System: Implementation of QR code-based access system for seamless visitor engagement.

- Evaluation Criteria: Assessment based on production efficiency, content quality standards, visitor accessibility requirements, and long-term institutional sustainability considerations.

4. Case Study Archaeological Museum Of Eleusis

4.1. Research Context and Implementation Framework

- Comprehensive conservation documentation availability, ensuring sufficient technical data for content development Historical and cultural significance warranting enhanced visitor engagement and interpretive investment

- Diversity of conservation challenges to effectively test various content generation approaches and methodologies

- Strategic exhibition placement suitable for seamless QR code integration and visitor accessibility

- 1)

- Source material: Comprehensive conservation reports, technical documentation, and detailed mounting specifications from the re-exhibition process

- 2)

- Visual assets: High-resolution photographs documenting both conservation treatment stages and final installation phases, captured during the re-exhibition project, supplemented with contextual museum environment shots and detailed artifact imagery

- 3)

- Language adaptation: Technical conservation terminology systematically simplified for general audiences through AI-assisted processing via ChatGPT, with two different prompt strategies

- a)

- Case 1: “HIEROPHANT” Inscription (Synthesia) with prompts specifically designed to accommodate both adult and child visitors

- b)

- Case 2: Antinous Statue (Clipchamp) with prompts specifically designed for adult visitor comprehension levels

- 1)

- Content review: All generated materials supervised and formally approved by qualified museum conservation personnel

- 2)

- Platforms: All AI-assisted processing and QR code generation were carried out using the free versions of Synthesia, Clipchamp and QR Code Monkey code to ensure cost-effectiveness and accessibility.

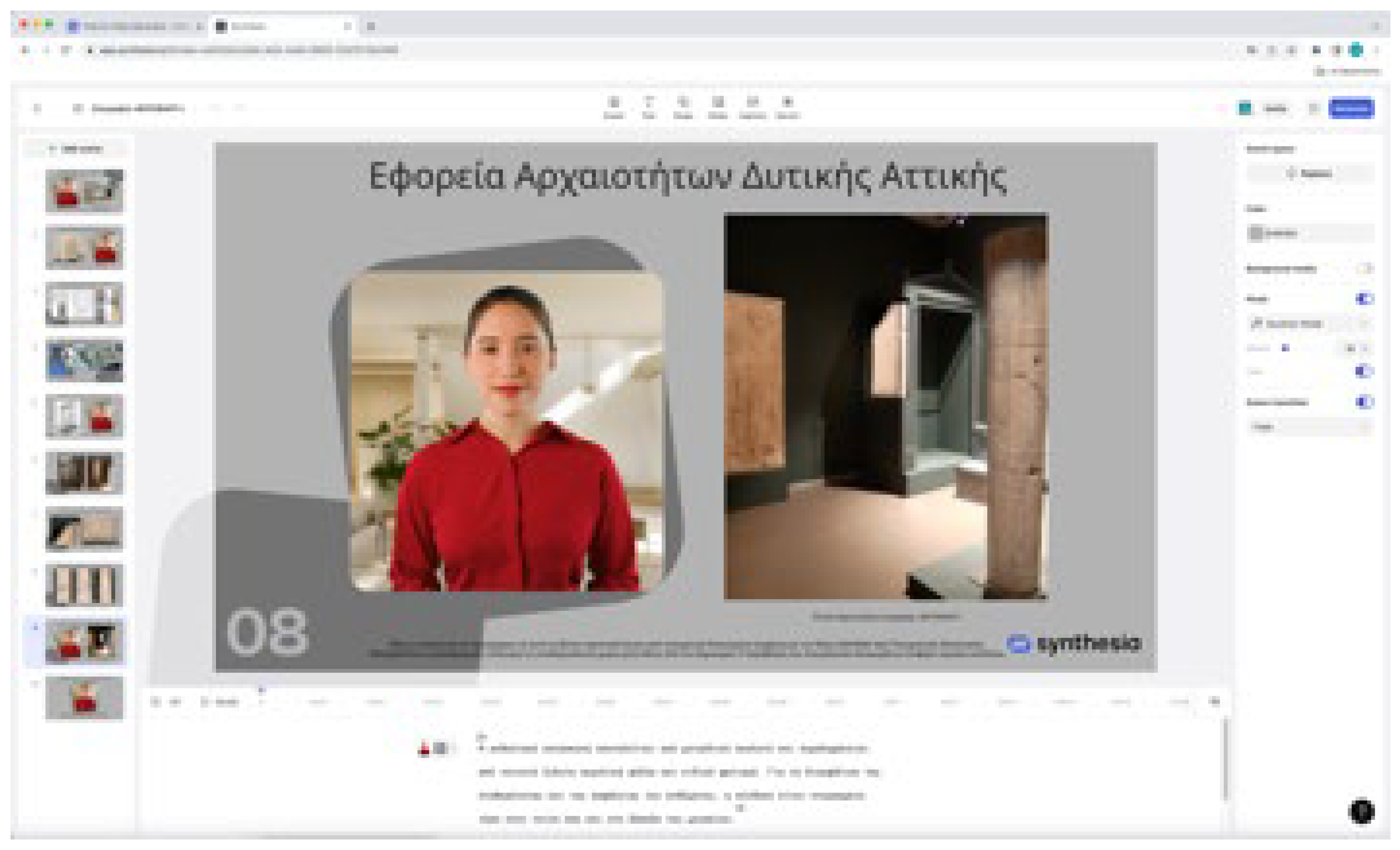

4.2. Case 1: “HIEROPHANT” Inscription (Synthesia)

- Platform: Synthesia (AI avatar-based video generation system)

- Template configuration: Graphic Knowledge Base template selected for educational content presentation

- Avatar selection: “Alex” (red shirt configuration), friendly female presenter with neutral, approachable appearance designed for diverse audience engagement

- Voice generation: AI-powered voice synthesis configured for Greek language

- Visual integration: Strategic combination of high-quality conservation photographs with supplementary contextual information

- Technical features utilized: Advanced script-to-video conversion capabilities with professional avatar presentation

- Content specifications: Script length of approximately 233 words, targeting 1:38 minute duration for optimal visitor attention spans

- Primary access method: QR codes generated via QR Code Monkey platform for reliable, cost-effective visitor access

- Physical integration approach: QR codes designed for printing and mounting in close proximity to exhibit displays (proposed implementation)

- Secondary access provision: Direct URL availability through the museum’s existing digital resource infrastructure (proposed enhancement)

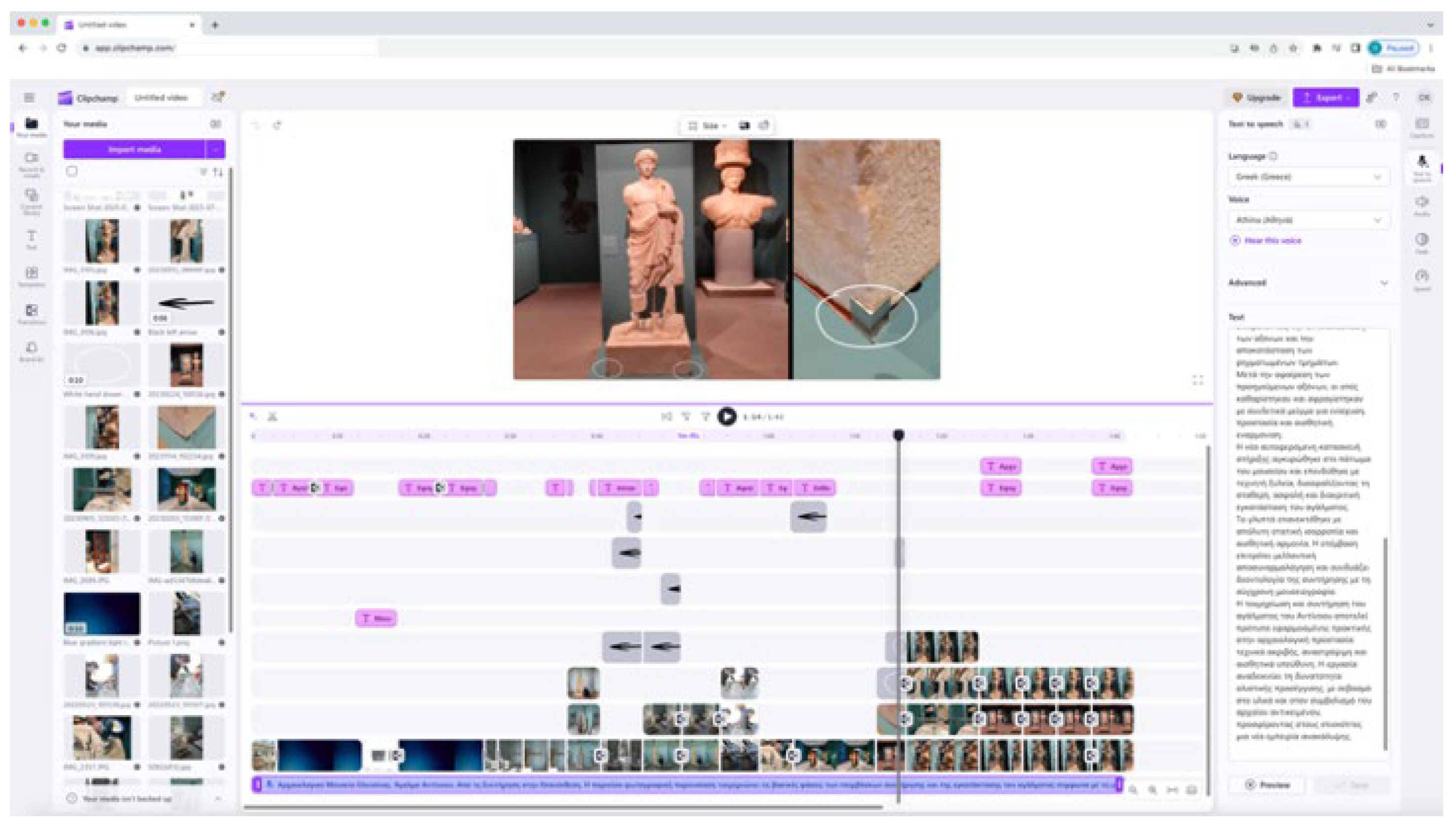

4.3. Case 2: Antinous Statue (Clipchamp)

- Platform: Clipchamp (AI-assisted video editing and production system)

- Voice generation: AI-powered voice synthesis configured for Greek language delivery

- Voice selection: “Athina” voice profile selected for natural, engaging presentation suitable for museum contexts

- Visual integration: Strategic combination of conservation treatment photographs with comprehensive contextual information and interpretive elements

- Technical features utilized: Dynamic captioning system, sophisticated pitch and speed adjustment capabilities for natural, accessible delivery

- Content specifications: Script length of approximately 180 words, targeting 1:43 minute duration for optimal visitor engagement

- Primary hosting platform: YouTube (unlisted configuration for institutional content control and privacy management)

- Access method: QR codes generated via QR Code Monkey platform for reliable visitor access

- Physical integration approach: QR codes designed for printing and mounting in close proximity to exhibit displays (proposed implementation)

- Secondary access provision: Direct URL availability through the museum’s existing digital resource infrastructure (proposed enhancement)

5. Comparative Analysis

5.1. Production Analysis

- Content preparation phase: Systematic script development and comprehensive visual asset compilation specifically designed for conservation documentation presentation

- Video production capabilities: Demonstrated highly efficient content generation capabilities suitable for resource-constrained institutional environments

- Quality assurance protocols: Multiple iterative review cycles necessary to ensure adherence to scholarly standards and institutional quality requirements

- Platform cost analysis: Free tier functionality proved sufficient for current project scope and institutional requirements

- Professional supervision framework: Continuous conservator oversight during all production stages ensured scientific accuracy, cultural sensitivity, and maintenance of high-quality visual standards

5.2. Platform Comparison

| Platform | Platform Comparison Matrix | |

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Synthesia | Rapid content production enabling quick deployment | Subscription model required for advanced institutional features |

| Accessible interface suitable for non-technical museum staff | Single-platform dependency creating sustainability concerns | |

| Streamlined presentation format with easy content modifications | Limited avatar expressiveness and emotional range | |

| Dynamic captioning system and multilingual support | Avatar presentation may be perceived as impersonal or distracting by some visitors | |

| Professional avatar appearance | AI voice quality in Greek requires improvement for natural delivery | |

| Avatar presentation may be more appealing to younger audiences | Reduced flexibility in visual presentation options | |

| Initial familiarization period necessary for optimal utilization | ||

| Requires comprehensive preparation of visual assets and materials | ||

| Clipchamp | Complete creative control over visual presentation and narrative flow | Advanced technical skills necessary for optimal implementation |

| Platform independence reducing vendor lock-in risks | Extended editing time demanding greater staff investment | |

| Natural-sounding AI voice narration specifically optimized for Greek language | Moderate technical learning curve for museum personnel | |

| Seamless integration of high-quality conservation photographs | Requires comprehensive preparation of visual assets and materials | |

| Dynamic captioning system and multilingual support | Dependence on external hosting platforms for content distribution | |

| Avatar-free format | Absence of avatar may be less engaging for younger visitors | |

| Avatar-free format, may be more appealing to adult audiences. | ||

- The comparative analysis reveals that institutional priorities and resources should guide platform selection. Museums with limited technical expertise and tight timelines may benefit from

6. Discussion And Future Work

Acknowledgments

References

- “On cultural heritage and collective memory,” Archaeology Newsroom, Archaeology & Arts, 2012.

- M. Andreadaki-Vlazaki, “Foreword,” in Management and Promotion of Sites and Monuments, S. Vlizos and N. Pantzou, Eds. Athens, Greece: Diadrasis, 2021.

- H. Mendoza and A. Santana Talavera, “Governance strategies for the management of museums and heritage institutions,” Heritage, vol. 8, no. 4, p. 127, 2025. [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- E. Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. London, UK: Routledge, 1992.

- K. Drotner, V. K. Drotner, V. Dziekan, R. Parry, and K. C. Schrøder, The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Media and Communication. London, UK: Routledge, 2019.

- International Council of Museums (ICOM), “Code of ethics for museums,” Paris, France: International Council of Museums, 2009.

- International Council of Museums (ICOM), “Museum definition,” 2022.

- France Archives, “Georges Henri Rivière (1897–1985),” 2014.

- Colin, Basic concepts of museology. Paris, France: International Council of Museums (ICOM), 2010.

- Digital Transformation Strategy Initiative in Cultural Heritage: The Case of Tate Museum, 2021. [Online]. Available: ResearchGate.

- M. Shah, “Digital experience service in modern museums,” ViitorCloud Blog, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://viitorcloud.

- The Tate’s Digital Transformation, Harvard Case Solution & Analysis, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.thecasesolutions.com/the-tates-digital-transformation-2-69781.

- Getty Blog, “Beyond digitization: New possibilities in digital art history,” 2015. [Online]. Available: https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/beyond-digitization-new-possibilities-in-digital-art-history/.

- Digitaltransform.gr., “Digitization and publication of selected collections of the National Archaeological Museum and the former Royal Estate of Tatoi,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.digitaltransform.gr/psifiopoiisi-kai-dimosiopoiisi-epilegmenon-syllogon-tou-ethnikou-archaiologikou-mouseiou-kai-tou-proin-vasilikou-ktimatos-tatoiou/.

- Acropolis Museum, “Acropolis Museum digital guide,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.theacropolismuseum.gr/psifiakos-odigos-moyseioy-akropolis.

- National Gallery of Art, “Free images and open access,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nga.gov/artworks/free-images-and-open-access.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Terms and conditions of use,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.metmuseum.org/policies/terms-and-conditions.

- S. Pansoni, S. S. Pansoni, S. Tiribelli, M. Paolanti, F. Di Stefano, E. Frontoni, E. S. Malinverni, and B. Giovanola, “Artificial intelligence and cultural heritage: Design and assessment of an ethical framework,” The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, vol. XLVIII-M-2-2023, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://isprs-archives.copernicus.org/articles/XLVIII-M-2-2023/1149/2023/isprs-archives-XLVIII-M-2-2023-1149-2023.pdf.

- Mimeta, “The future of AI-driven cultural heritage?” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mimeta.org/mimeta-news-on-censorship-in-art/2025/3/12/is-now-the-future-of-ai-driven-cultural-heritage. 2025.

- Linkfactory, “Digital strategies for museums 2021–2022,” 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.linkfactory.dk/sites/default/files/2021-10/Digital%20strategies%20for%20museums%202021%3A2022%20%20LinkFactory.pdf.

- M. Charr, “The role of digital engagement in museums,” MuseumNext, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.museumnext.com/article/the-role-of-digital-engagement-in-museums/.

- Europeana, “Europeana collections.” [Online]. Available: https://www.europeana.eu/. Accessed: Aug. 29, 2025.

- Google Arts & Culture, “Online museum collections and virtual exhibitions.” [Online]. Available: https://artsandculture.google.com/. Accessed: Aug. 29, 2025.

- P. F. Marty, “Museum websites and museum visitors: Before and after the museum visit. Museum Management and Curatorship 2007, 22, 337–360. [CrossRef]

- P. F. Marty, “Museum websites and museum visitors: Digital museum resources and their use. Museum Management and Curatorship 2008, 23, 81–99. [CrossRef]

- N. Proctor, “Digital: Museum as platform, curator as champion, in the age of social media,” , vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 35–43, 2010. [Online]. Curator: The Museum Journal 2010, 53, 35–43. [CrossRef]

- A.P. O. S. Vermeeren, et al., “Future museum experience design: Crowds, ecosystems and novel technologies,” in Museum Experience Design, A. Vermeeren, Ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2018, pp. 1–16. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- D. Schmalstieg and T. Hollerer, Augmented Reality: Principles and Practice. Boston, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley, 2016.

- Vassilakis, et al., “exhiSTORY: Smart exhibits that tell their own stories,” Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 81, pp. 542–556, 2018. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- V. Poulopoulos and M. Wallace, “Digital technologies and the role of data in cultural heritage: The past, the present and the future,” Big Data and Cognitive Computing, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 73, 2023. [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- J. Cronyn, The Elements of Archaeological Conservation. London, UK: Routledge, 1990.

- UNESCO Digital Library, “Staff training, the conservator-restore,” Museum, vol. XXXIX, no. 4, pp. 231–233, 1987.

- M. Hatzidaki, “The necessity of documentation of conservation work: The documentation of conservation and the conservation of documentation,” in Proceedings of the conference on the topic: Conservation and Exhibition of Preserved Works. Technical Problems—Aesthetic Problems, Series: Small Museological Issues 1, 2005, pp. 23–28.

- Caple, Conservation Skills: Judgement, Method and Decision Making. London, UK: Routledge, 2000.

- N. Stolow, Procedures and Conservation-Standards for Museum Collections in Transit and on Exhibition. Paris, France: UNESCO, 1981.

- UNESCO and ICCROM, “Endangered heritage: Emergency evacuation of heritage collections,” 2016.

- European Commission, “Europe’s digital decade: Digital targets for 2030,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-decade-targets.

- R. Yin, Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage, 2018.

- S. Sylaiou, F. S. Sylaiou, F. Liarokapis, K. Kotsakis, and P. Patias, “Virtual museums: A survey and some issues for consideration. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2009, 10, 520–528. [Google Scholar]

- My Eleusis, “Eleusinian mysteries,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://myeleusis.com/. Accessed: Sep. 10, 2025.

- UNESCO, “Recommendation concerning the protection and promotion of museums and collections, their diversity and their role in society,” Paris, France: UNESCO, 2015.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).