Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. From AI Definition to Museum Practice: A Brief Overview

3. Methods

- In what ways can AI improve art museum operations (e.g., management, strategy, visitor services, core technical processes) contributing to their resilience and sustainability?

- How is AI applied to optimize collection management in art museums?

- How can AI enhance the visitor experience in art museums to renew interest in art and its context through exhibits and exhibitions?

- What challenges arise from integrating AI in art museum settings, and how can these be effectively addressed within a human-centered cultural management framework?

4. AI-Enhanced Operational & Strategic Efficiency

5. AI-Driven Management of Digital Collections: From Tags to Tales

6. Optimizing Visitor Experience through AI

6.1. AI-powered Chatbots

6.2. Other AI-Driven Visitor Experiences

7. Navigating Challenges with a Human-AI Compass

8. Results-Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Table A1

| A/O | Author(s) / Source | AI Benefits in Museums | Sustainability Impact | AI Challenges in Museums |

|---|---|---|---|---|

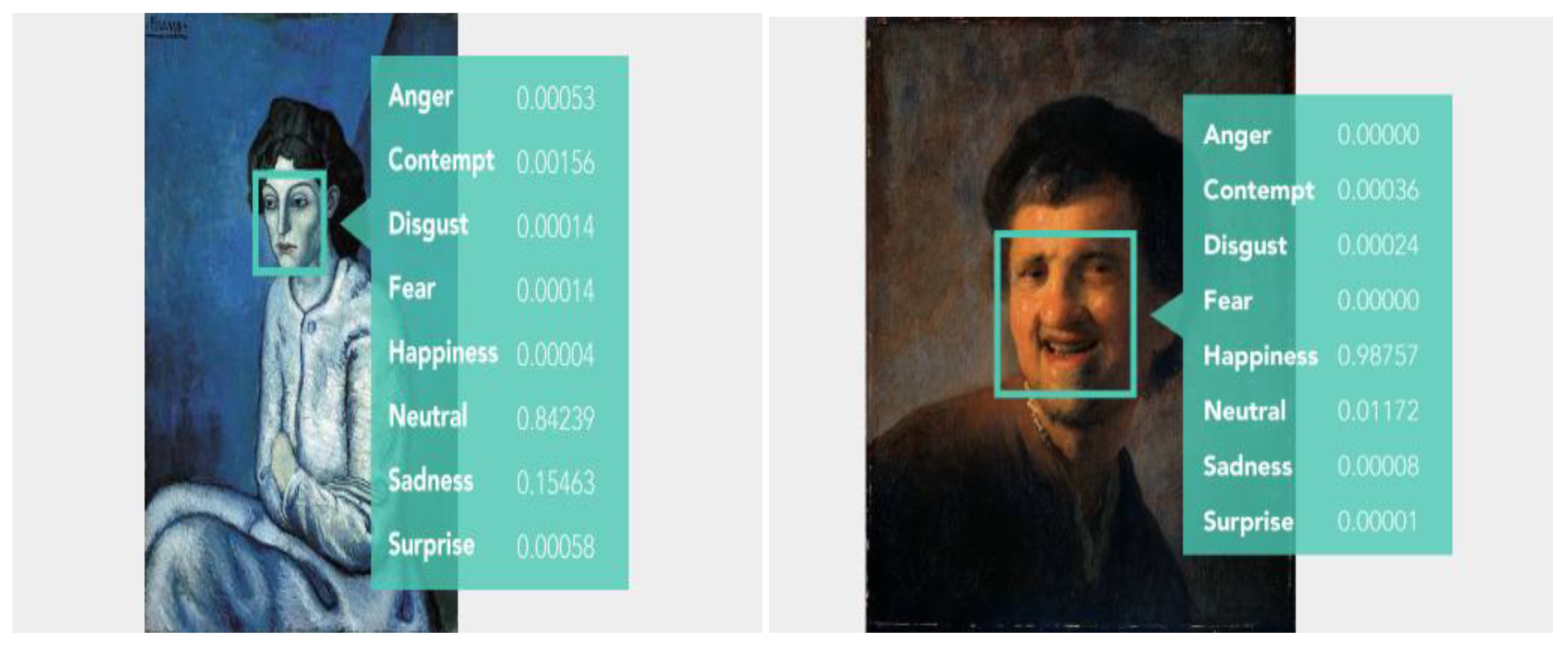

| 1 | [43] | FRT enables quantitative analysis, sitter identification, artist style characterization, objective feature comparison, and statistically robust research in art collections. | Cultural sustainability | FRT in art is challenged by artistic distortions, limited data samples, and the influence of stylistic conventions. |

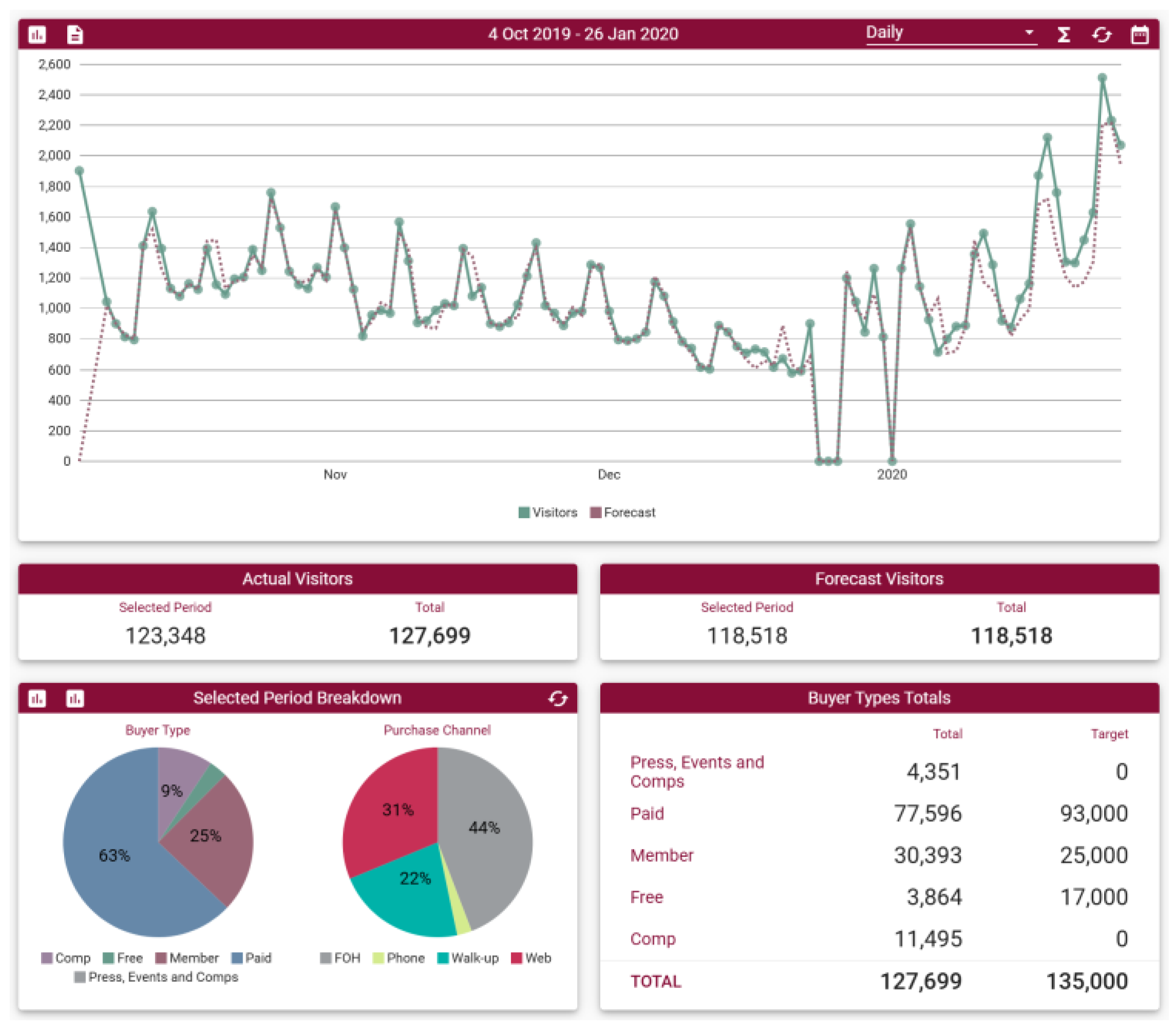

| 2 | [32] | AI aids in analyzing and categorizing collection data.Machine vision improves object identification, pattern recognition, and sentiment analysis. It optimizes ticketing, attendance prediction, membership engagement, and fundraising. It enhances e-commerce through personalized recommendations. | Cultural/ economic/ social sustainability | Requirements include substantial resources, time, tools, and expertise for data structuring and system training. |

| 3 | [44] | At the Smithsonian, AI accelerates botanical research by using DL to identify specimens, detect contamination, and differentiate similar species—streamlining data sorting and allowing scientists to focus on complex research, enhancing productivity. | Economic/ cultural sustainability |

Opaque decision-making, hard-to-verify outcomes, and limited effectiveness in complex genetic analysis, requiring further refinement for broader scientific use. |

| 4 | [64] | Google’s BigQuery dataset of The Met’s public domain artworks enabled advanced image analysis via Cloud Vision API—supporting tasks like recognition, color sorting, and landmark detection—to improve metadata, enhance digital access, and optimize collection management. | Cultural/social/ economic sustainability | |

| 5 | [76] | AI exploration of latent space reveals hidden visual possibilities, enabling smooth shifts between abstraction and realism and expanding creative potential in machine-generated art. | Cultural sustainability | AI art faces challenges in controlling outputs, balancing human and machine creativity, managing tensions between large-scale models and artistic control, and adapting to rapid technological change. It also challenges traditional concepts of authenticity, authorship, and originality, requiring ethical, explainable, context-aware results and ongoing long-term maintenance. |

| 6 | [39] | AI at museums like MoMA, the Broad, and AIC analyzes visitor data to optimize exhibitions, improve ticket distribution, and boost engagement. | Cultural/ economic sustainability |

|

| 7 | [70] | AI uncovers surprising links between unrelated artworks, broadening perspectives and deepening understanding of collections | Cultural sustainability | Challenges in AI-driven art interpretation include frequent misclassification, limited contextual and historical understanding, tension with curatorial authority due to disparities between human and AI perspectives, and disruption of traditional notions of artistic intent and expertise. |

| 8 | [83] | The Museum of Tomorrow’s IRIS+ system uses AI to personalize visitor interactions, promote social and environmental initiatives, enhance accessibility, and continually improve engagement through data analysis, for more tailored experiences. | Social / environmental sustainability | |

| 9 | [72] | AI Analyzes a diverse artwork dataset and generates imaginative variations, expanding creative possibilities. Through open data, it fosters global engagement with art via innovative digital tools. | Cultural/social sustainability |

|

| 10 | [54] | AI improves searchability of large image collections by enhancing metadata and optimizing information retrieval. | Cultural/ economic sustainability |

Difficulties include managing data ambiguity, ensuring precision, and achieving context-specific customization. |

| 11 | [111] | Anti-recommendation systems promote discovery and serendipity, exposing visitors to diverse content and enriching cultural experiences by reducing echo chambers. | Cultural/social sustainability |

|

| 12 | [12] | AI enhances visitor experiences with personalized recommendations and interactive assistance, while streamlining collection management through clustering and automating repetitive tasks. | Cultural/ economic sustainability |

Requires accurate, representative data and clear task definitions; integrating AI into museum workflows remains complex. |

| 13 | [65] | The Met’s Open Access program and public API allow developers and researchers to interact with its collection data, enabling innovations like training computer vision models for artwork tagging. | Cultural/social/ economic sustainability |

Art interpretation subjectivity, limited training data, diverse collections, and gender identification complexity. |

| 14 | [63] | AI improves object discoverability and cataloging by enriching metadata and accelerating large dataset analysis, enhancing research efficiency and visual interpretation. | Cultural/ economic sustainability |

Risk of bias (gender, cultural inaccuracies) and offensive outcomes; requires careful monitoring for ethical, accurate AI use in cultural contexts. |

| 15 | [40,41,42] | Integrating AI with MET in museums enhances data analysis, personalizes visitor experiences, optimizes exhibit design, and detects social interactions, delivering insights that boost engagement and streamline operations. | Cultural/social/ economic sustainability |

Current eye-tracking systems face technical limits. MET systems struggle with cost and accuracy in dynamic settings. |

| 16 | [36] | AI provides solutions to museum challenges through efficient data analysis, accurate attendance forecasting, and metadata creation. It supports strategic planning in pricing, marketing, and operations, driving audience growth and engagement. Partnerships with tech companies grant access to advanced tools. By being transparent about AI use and offering public programs, museums can enhance visitor literacy and critically engage with AI’s societal impact. | Cultural /economic /social sustainability |

Ethical and governance concerns include questionable practices, brandwashing, and lack of regulation. Data and algorithmic issues involve bias and insufficient training data. Operational challenges require human quality assurance and aligning AI with the museum’s mission, balancing commercial goals with scholarship and critical dialogue. |

| 17 | [49] | AI uncovers new connections between museum objects, complementing curation and enriching the narrative, while making complex themes accessible to diverse audience and enhancing engagement. | Cultural/social sustainability |

Balancing human and AI roles alongside AI’s physical limitations. |

| 18 | [117] | Integrating AI in smart museums enables intelligent, human-centered displays that boost engagement and accessibility. It streamlines exhibit layout, route planning, and real-time audience analysis for precise artifact presentation. | Cultural/social/ economic sustainability |

AI-driven 3D modeling may lack artistic nuance, while optimization algorithms require refinement for real-time precision and fluid interaction. |

| 19 | [46] | AI enhances painting and calligraphy authentication by combining hyperspectral imaging with convolutional neural networks for faster, more accurate forgery detection. | Cultural/ economic sustainability |

|

| 20 | [34] | AI modernizes visitor experiences through personalization and NLP chatbots, enriches education through interactive storytelling and feedback analysis, and enhances operational efficiency via visitor flow prediction and resource allocation. It supports data-driven decisions, improves knowledge management through integrated learning frameworks, and provides security and behavioral insights via visitor tracking and social interaction mapping. | Cultural/ economic sustainability |

Key challenges include ethical concerns, the need for strategic AI integration, process redesign, financial constraints, staff mindset shifts and skill gaps, and the technical complexity of integrating Big Data, ML, NLP, and neural networks. |

| 21 | [13] | AI-powered digital design enables museums to create visually compelling and aesthetically pleasing spaces.AI enhances the interactive experience of museum visitors, allowing them to engage more deeply with the cultural content, creating a more immersive and participatory learning environment. | Cultural/social sustainability |

Requires ongoing hardware and technological advancements for optimal performance and integration. |

| 22 | [66] | It helps museum curators improve cultural metadata quality and information retrieval by automating artwork annotation, refining search results, and using semantic reasoning with ML for more accurate predictions. | Cultural/ economic sustainability |

Challenges include ensuring annotation accuracy and efficiency, limitations of iconographic thesauruses for diverse artworks, difficulties in applying ML algorithms to art collections, and complexities in integrating semantic and visual data. |

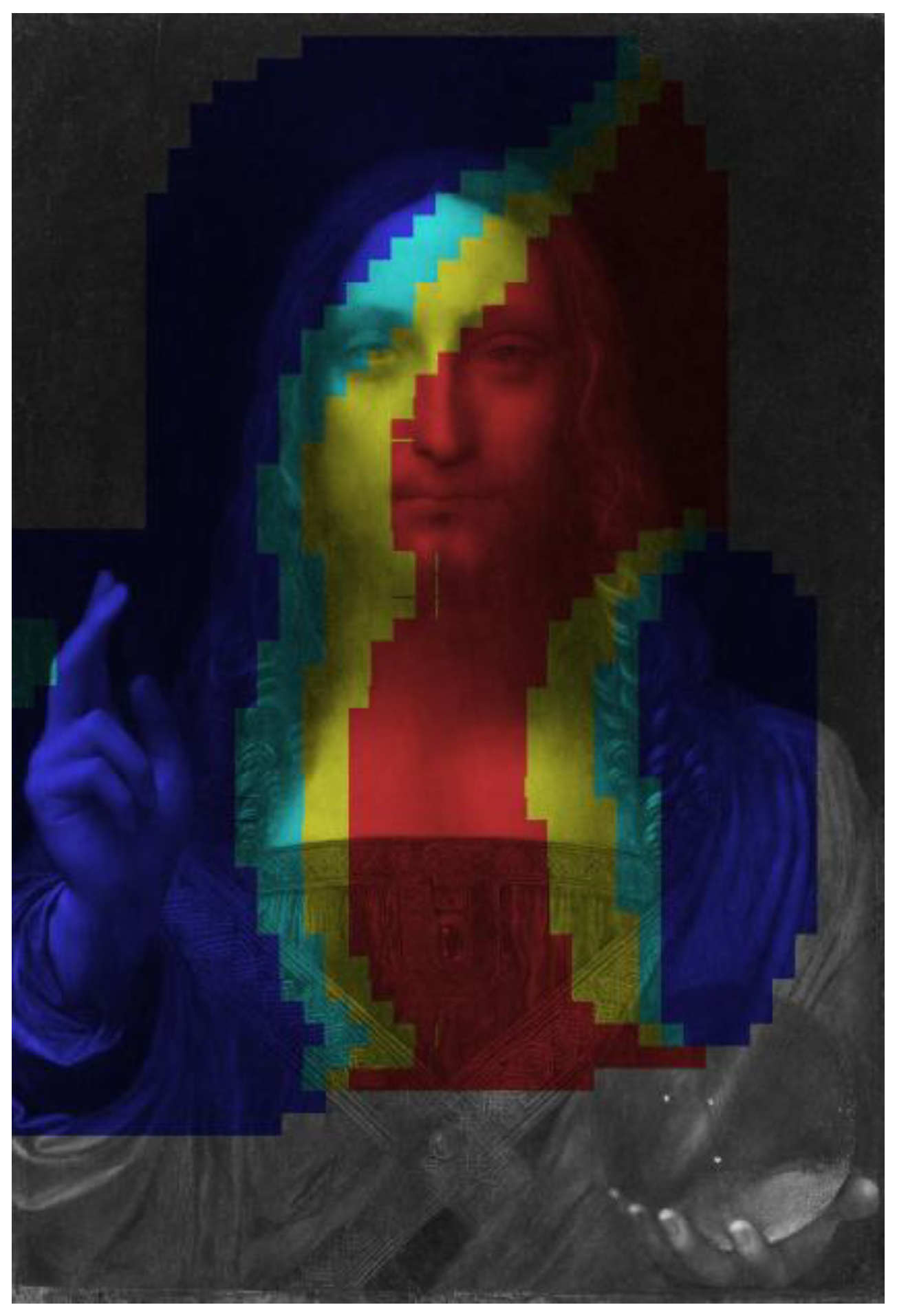

| 23 | [47] | AI-generated "probability maps" improve art authentication by detecting forgeries and attributing works accurately, using CNN technology for precise visual pattern and brushstroke analysis, enhancing scholarly understanding. | Cultural/economic sustainability |

There is a need to combine AI methods with traditional scientific analysis and human expertise, requiring careful and often complex integration. |

| 24 | [78] | In art, AI creates dynamic, data-driven works that explore new perceptions and abstractions, creating novel forms and visuals that push traditional boundaries. | Cultural sustainability |

|

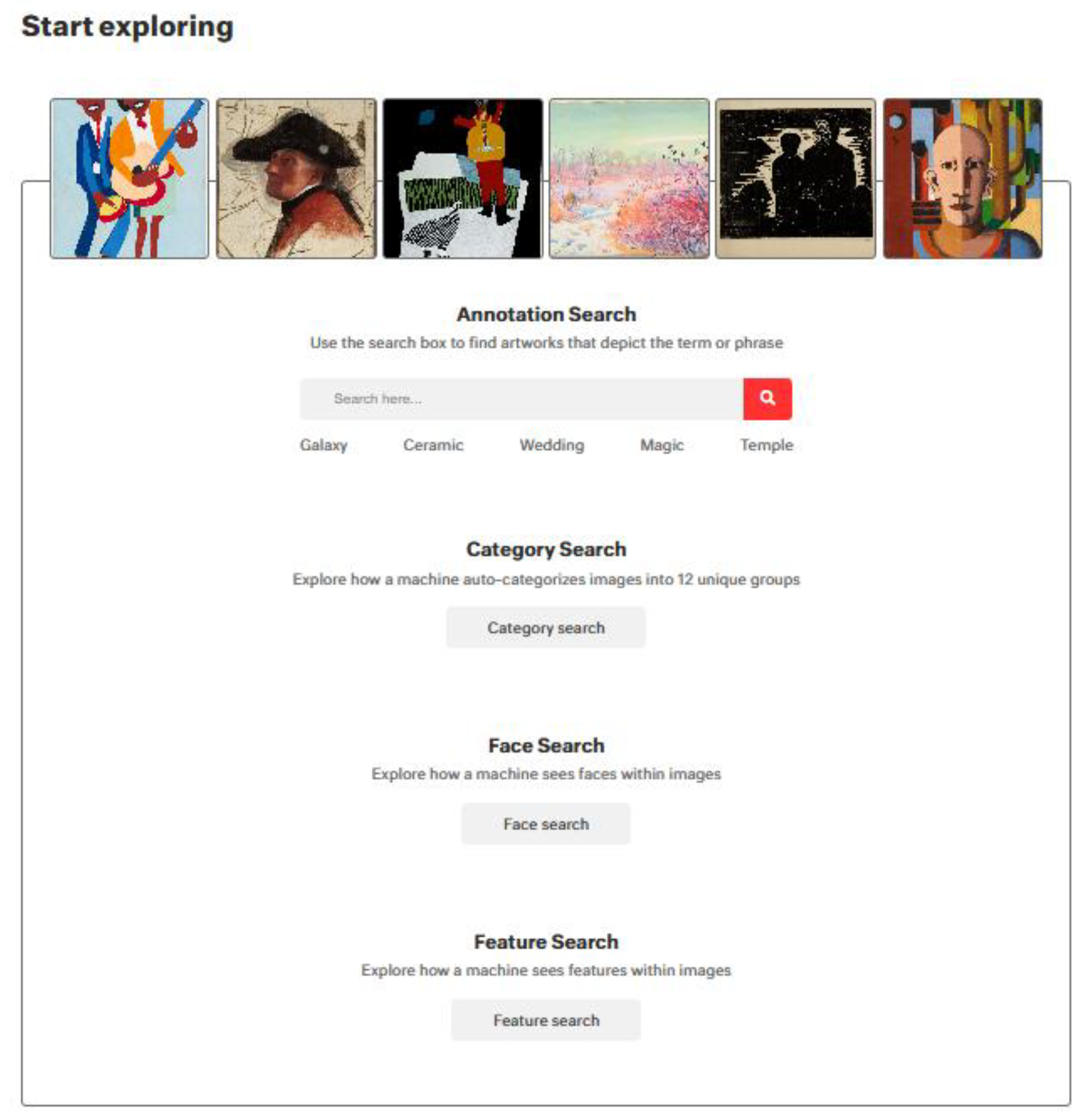

| 25 | [59] | AI (ML) systems enable art museums to uncover patterns in cultural data through methods like “distant seeing,” optimize archival resource use, and promote public education and AI literacy by serving as testbeds for diverse audiences. | Cultural / social sustainability |

Challenges include labor exploitation, environmental harm, limited public involvement, and the overwhelming complexity of AI that discourages critical understanding and engagement. |

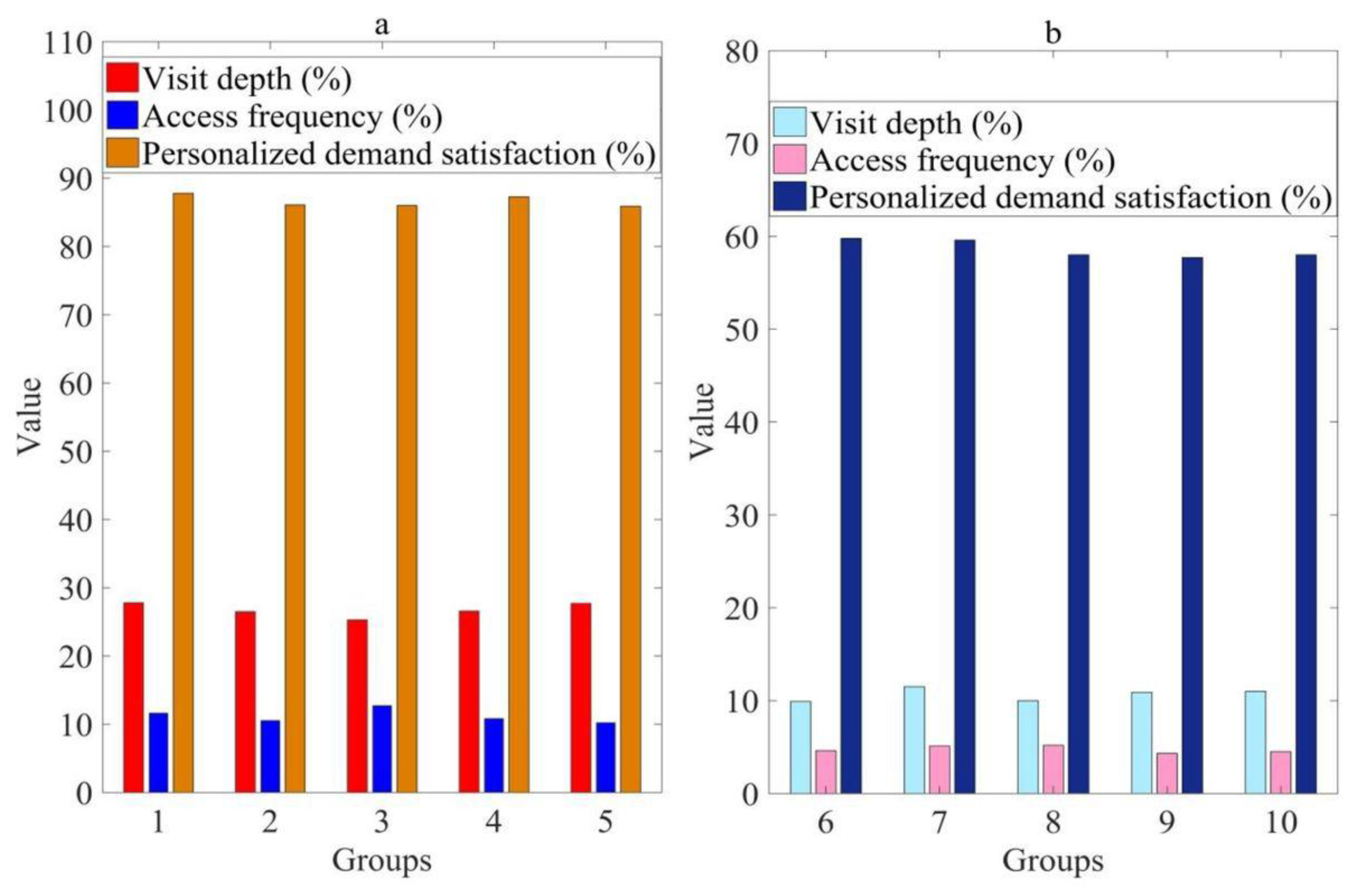

| 26 | [14] | AI interactive systems, powered by database management, enhance in-depth exhibition design, offer diverse personalized experiences, boost visitor satisfaction, optimize museum management (visitor flow, resource use), and promote cultural value transmission. | Economic/social/ cultural sustainability |

|

| 27 | [38,48] | AI aids in preserving aging and fading artworks, as demonstrated by the Rijksmuseum and the Van Gogh Museum. | Cultural economic sustainability |

|

| 28 | [55] | AI enhances access and discoverability, improves data handling efficiency, and fosters innovative learning and interaction methods. | Social/cultural sustainability | AI faces critical concerns including reinforcement of power structures like Eurocentrism and bias, unchecked tech solutionism, knowledge concentration, environmental impacts, and a need for transparency due to hidden labor, biased data, and poor documentation. |

| 29 | [131] | AI boosts knowledge discovery by uncovering complex patterns, fuels innovation with advanced data processing, and enriches cultural engagement through new ways to explore archives and art. | Cultural sustainability | Environmental impact covers energy use, carbon footprint, resource extraction, and exploitation. AI embeds biases and ethical concerns reflecting its creators’ values. There’s also a risk of tech solutionism and power concentration (e.g., Silicon Valley), highlighting the need for equity and decolonization. |

| 30 | [119] | AI enriches visitor experience by sparking creativity, enabling human-AI co-creation, and encouraging public dialogue. | Social/ cultural sustainability | Ethical issues include training data concerns, missing artist consent and compensation, loss of curatorial control, and GenAI “hallucinations.” |

| 31 | [35] | AI improves visitor services and education, enhances museum experiences, optimizes management and workflows, boosts collection care, and advances research and analysis. | Cultural /social/ economic sustainability | Unaddressed biases reinforce structural racism, colonialism, and gender inequality; AI-powered chatbots and robots risk replacing curatorial and service staff; and unequal global development leads to dominance by select countries and companies. |

| 32 | [15] | AI helps museums strengthen visitor relationships by personalizing experiences, aiding navigation, and providing real-time answers to art-related questions. | Social/ cultural/ economic sustainability |

Underuse of interactive AI leads to one-way social media communication and low user engagement, limiting meaningful visitor interactions. |

| 33 | [67] | At Nasjonalmuseet, AI boosts digitization, accessibility, and relevance through semantic search, contextual understanding, advanced image analysis, feedback-driven refinement, and open-source AI. | Cultural/social/ economic sustainability |

Challenges include content sensitivity, multilingual ambiguities, slow performance, and reliance on commercial AI models misaligned with cultural heritage needs. |

| 34 | [45] | AI tools are reshaping fine arts by enabling rapid creation, analysis, and transformation of artworks, while challenging traditional views of human creativity. | Cultural/social/ economic sustainability |

|

| 35 | [20] | AI enhances museum experiences through customization, interactive content, real-time insights, and immersive engagement, while also improving data analytics, digital preservation, security, curatorial decision-making, conservation tracking, and visitor behavior analysis. | Cultural/social/ economic sustainability |

AI implementation faces challenges like interpretation difficulties, lack of expertise, restricted data access (due to privacy, security, and quality), high infrastructure costs, privacy concerns, and ethical issues like bias, transparency, and consent. |

| 36 | [8] | AI-driven personalization enhances visitor engagement and satisfaction, improves brand perception of heritage sites, supports cultural heritage preservation, and increases visitor duration. | Cultural /economic sustainability | Data privacy and security concerns. |

| 37 | [25] | AI empowers museums to integrate into digital knowledge cultures, create immersive hybrid experiences, foster public dialogue and ethical reflection on AI, enhance education for critical engagement with AI tools, and advance collection analysis through sophisticated image and context recognition—strengthening their cultural and educational mission. | Cultural /social /economic sustainability | Ethical concerns (privacy, bias, data accuracy, agency, inclusion), misalignment of AI pace with museum workflows, skepticism and hesitation, loss of contextual data in ML preparation, hallucinations, and the need to adapt education and publications for AI tools. |

| 38 | [80] | AI enhances visitor engagement through chatbots and robot critics, automates content creation and recommendations, supports research and analytics for collections, and enables creative content like text-to-image and voice generation. | Cultural /social sustainability | AI adoption in museums faces resource constraints, algorithmic errors, ownership and copyright issues of AI-generated content, bias amplification, oversimplification, minority erasure, AI hallucinations, risks to vulnerable groups (e.g., via geolocation, FRT), and uncertain long-term impacts. |

| 39 | [37] | AI optimizes operations and strategy by analyzing visitor behavior, refining exhibition design, managing crowds, allocating resources, and forecasting attendance. It enhances visitor engagement with personalized recommendations and virtual assistants, advances heritage preservation via digitization and reconstruction, expands audience reach by promoting inclusivity and global collaboration, and sustains relevance by driving innovation and addressing public needs. | Cultural /social / economic sustainability | Ethical concerns include data privacy, algorithmic bias, and accessibility; integration challenges involve technical barriers, high costs, and the need for skilled staff. |

| 40 | [52] | AI automates metadata tagging, enhances search and discovery, and offers personalized recommendations. It improves accessibility for people with disabilities, supports mindfulness to reduce stress, and fosters engagement by enabling visitor interaction and contribution to exhibits. | Cultural/social sustainability |

Challenges include reliability, biased outputs, privacy concerns, ethical use, need for skilled human oversight, resource demands for AI training, scarce in-house expertise, and high implementation costs. |

| 41 | [3] | AI transforms collection management and experience design, personalizes visitor journeys, and preserves cultural treasures via advanced digitization. It boosts engagement, streamlines operations, promotes inclusivity, and reinforces museums’ roles as stewards of knowledge, culture, and education, reshaping museum-public relationships for continued relevance and innovation in the digital age. | Cultural/social sustainability |

Ethical concerns include biases, transparency, accountability, and privacy, with implications for human rights, dignity, cultural values, and social responsibility. There are risks of reinforcing inequalities or distorting cultural representation, highlighting the need for robust ethical frameworks. |

| 42 | [118] | AI personalizes online experiences, boosts interactivity through gamification, AR/3D, and simulations, improves accessibility with image recognition and multilingual support, enhances artistic design, deepens educational storytelling, and drives data-informed curation. | Cultural/social sustainability | Data privacy concerns (e.g., GDPR compliance in the British Museum case), bias in narratives requiring adaptability, and ethical responsibility in AI deployment through strategic oversight. |

| 43 | [129] | AI transforms museum collection management and visitor experiences by enhancing accessibility and personalization, optimizing operations, preserving cultural heritage, ensuring ongoing relevance and innovation, and fostering critical public dialogue while enriching educational and cultural engagement. | Cultural/social/economic sustainability | Implementing AI in museums faces challenges including skepticism about its necessity and impact, operational and ethical issues such as bias, lack of transparency, overstimulation, and inclusivity paradoxes, fear rooted in low AI literacy and concerns over replacing human expertise, and limited research on AI’s actual benefits and risks, which may impede effective adoption and competitive advantage. |

| 44 | [17] | AI-powered Automatic Exhibition Guide Systems provide personalized audio-visual guides on mobile devices, boosting visitor engagement. | Cultural/social sustainability |

High costs and ongoing maintenance requirements. |

| 45 | [9] | Enhances digital storytelling AI enhances online visitor experiences, supports collection management, and enriches digital storytelling. |

Cultural sustainability | No direct effect on visitation rates has been observed. Challenges include data privacy, algorithmic bias, historical data accuracy, reliance on funding and digitization policies, limited regional adoption, and the need for qualitative, longitudinal research. |

| 46 | AI-powered Chatbots [84,85,87,88,90,91,92,95,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] | AI chatbots enhance visitor accessibility, engagement, and satisfaction through personalized, on-demand assistance. They offer real-time support for wayfinding, exhibitions, and services, integrate gamification, and provide deeper historical insights. Supporting educational goals, they blend learning with entertainment, while virtual conversations with historical figures create immersive, emotional, and cognitive experiences. | Cultural/social sustainability |

Concerns include understanding diverse queries, budget constraints, limited human-like comprehension, contextual sensitivity, lack of full accessibility in one-size-fits-all solutions, privacy issues, and AI output bias. |

| 47 | Other AI-driven Visitor Experiences [51,53,74,96,112,113,114,116,120,121,123,124,125,126,127] | AI-powered interactive museum implementations enrich visitor experiences with dynamic, co-created content tailored to individual preferences, empowering visitors. They turn static exhibits into immersive, multisensory interactions that inspire creativity, motivate participation, and deepen emotional and cognitive engagement. | Cultural/ social sustainability |

AI implementation faces challenges including high costs, reliability, transparency, data privacy, bias, cultural context understanding, art misinterpretation, and over-reliance on AI. |

References

- Tang, X., Li, X., Ding, Y., Song, M., & Bu, Y. (2020). The Pace of Artificial Intelligence Innovations: Speed, Talent, and Trial-and-Error. J. Informetrics, 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Russell, S., & Norvig, P. (2021). Artificial intelligence. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition). Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/artificial-intelligence/ accessed on 24 Mai 2025).

- Siri, A. (2024). Emerging Trends and Future Directions in Artificial Intelligence for Museums: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis Based on Scopus (1983-2024). Geopolitical, Social Security and Freedom Journal, 7 (1). [CrossRef]

- Mossavar-Rahmani, F., Zohuri, B. (2024). ChatGPT and beyond the Next Generation of AI Evolution (A Communication). Journal of Energy and Power Engineering 18, 146-154. [CrossRef]

- PwC. (2017). A Decade of Digital: Keeping Pace with Transformation. Global Digital IQ Survey; 2017. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/ee/et/publications/pub/pwc-digital-iq-report.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Qin, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, X., Skare, M. (2023). Artificial Intelligence and Economic Development: An Evolutionary Investigation and Systematic Review. J Knowl Econ 15, 1736–1770. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Kanaujia, A., Singh, V. K., & Vinuesa, R. (2023). Artificial intelligence for Sustainable Development Goals: Bibliometric patterns and concept evolution trajectories. Sustainable Development, 32(1), 724–754. [CrossRef]

- Saihood, G.S.W., Haddad, A.T.H., & Eyada, F. (2023). Personalized Experiences Within Heritage Buildings : Leveraging AI For Enhanced Visitor Engagement. 2023 16th International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering (DeSE), 474-479, Istanbul, Turkiye, 474-479. [CrossRef]

- Kiourexidou, M., & Stamou, S. (2025). Interactive Heritage: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Digital Museums. Electronics, 14(9), 1884. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-H., Rust, R.T. (2018). Artificial Intelligence in Service. Journal of Service Research, 21(2), 155-172. [CrossRef]

- Nisiotis, L., Alboul, L. (2021). Initial Evaluation of an Intelligent Virtual Museum Prototype Powered by AI, XR and Robots. In: International Conference on Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality and Computer Graphics. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 290-305. [CrossRef]

- Summers, K. (2019). Magical Machinery? What AI can do for museums. American Alliance of Museums. Available online: https://www.aam-us.org/2019/05/03/magical-machinery-what-ai-can-do-for-museums/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Wang, B. (2021). Digital design of Smart Museum based on Artificial Intelligence. Mobile Information Systems, 2021, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Cai, P., Zhang, K., & Pan, Y. (2023). Application of AI Interactive Device Based on Database Management System in Multidimensional Design of Museum Exhibition Content. [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.C., Faraci, R. (2023). Next-Generation Museum: A Metaverse Journey into the Culture. Sinergie Italian Journal of Management, 41(1), 147–176. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-H., & Rust, R. T. (2020). A strategic framework for artificial intelligence in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49(1), 30–50. [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-C., Li, I.-C., Wang, C.-Y., Shih, C.-H., Srinivaas, M., Yang, W.-T., Kao, C.-F., & Su, T.-J. (2025). Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Art Preservation and Exhibition Spaces. Applied Sciences, 15(2), 562. [CrossRef]

- Villaespesa, E., Murphy, O. (2021) This is not an apple! Benefits and challenges of applying computer vision to museum collections. Museum Management and Curatorship, 36(4), 362-383. [CrossRef]

- Cetinic, E., She, J. (2021). Understanding and Creating Art with AI: Review and Outlook. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications (TOMM) 18: 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Rani, S., Dong J., Dhaneshwar S., Siyanda X., Prabhat R. S. (2023). Exploring the Potential of Artificial Intelligence and Computing Technologies in Art Museums. ITM Web of Conferences 53. [CrossRef]

- Beckett, L. (2024). World’s first AI art museum to explore ‘creative potential of machines’ in LA. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/sep/25/ai-art-museum-los-angeles-dataland (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Oxford English Dictionary (OED). (2023). Artificial intelligence. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, H., Prins, C., Schrijvers, E. (2023). Artificial Intelligence: Definition and Background. In: Mission AI. Research for Policy. Springer, Cham (pp. 25-37). [CrossRef]

- HLEG. High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence. (2019). A definition of AI: Main capabilities and scientific disciplines. European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=56341 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Thiel, S. (2023). Managing AI Developing Strategic and Ethical Guidelines for Museums. In S. Thiel & J. Bernhardt (Eds.), AI in Museums. Reflections, Perspectives and Applications (Edition Museum 74, pp 83-98). Transcript. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A. (1959). Some Studies in Machine Learning Using the Game of Checkers. IBM Journal 3(3): 210–229. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5392560 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Koza, J.R., Bennett, F.H., Andre, D., Keane, M.A. (1996). Automated Design of Both the Topology and Sizing of Analog Electrical Circuits Using Genetic Programming. In: Gero, J.S., Sudweeks, F. (eds) Artificial Intelligence in Design ’96. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Avlonitou, C., Papadaki, E. (2025) AI: An Active and Innovative Tool for Artistic Creation. Arts 2025, 14(3), 52; [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Li, S., Liu, Y., Yan, Z., Dai, Y., Yu, P.S., & Sun, L. (2023). A Comprehensive Survey of AI-Generated Content (AIGC): A History of Generative AI from GAN to ChatGPT. [CrossRef]

- Zao-Sanders, M. (2025). Generative AI: How People Are Really Using Gen AI in 2025. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2025/04/how-people-are-really-using-gen-ai-in-2025 (accessed on 30 Mai 2025).

- Ao, X., Du, S., & Tian, X. (2023). The application status and development trends of intelligent voice recognition systems in museums. In G. Grigoras & P. Lorenz (ed.), Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Big Data and Algorithms (CAIBDA 2023), Zhengzhou, China, 103-112. [CrossRef]

- Ciecko, B. (2017). Examining the Impact of Artificial Intelligence in Museums. MW17: MW 2017. Available online: http://mw17.mwconf.org/paper/exploring-artificial-intelligence-in-museums/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Maerten, A-S., Soydaner, D. (2023). From paintbrush to pixel: A review of deep neural networks in AI-generated art. [CrossRef]

- Vidu, C., Zbuchea, A., Pinzaru, F. (2021). Old meets new: integrating Artificial Intelligence in museums’ management practices. Strategica. Shaping the Future of Business and Economy. 830-844. Available online: https://strategica-conference.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/63-1.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Hufschmidt, I. (2023). Troubleshoot? A Global Mapping of AI in Museums. In S. Thiel & J. Bernhardt (Eds.), AI in Museums. Reflections, Perspectives and Applications (Edition Museum 74, 131-149). Transcript. [CrossRef]

- Villaespesa, E. & Murphy, O. (2020). The Museums + AI Network - AI: A Museum Planning Toolkit. [CrossRef]

- Falola, T. (2024). Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytics for Enhancing mseum experiences: Exploring historical narratives, visitor engagement, and digital transformation in the age of innovation. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science, 6(1), 4221-4236. https://www.doi.org/10.56726/IRJMETS49059.

- Consultancy.eu. (2023). AI tool helps Van Gogh Museum sieve through visitor feedback. Available online: https://www.consultancy.eu/news/9635/ai-tool-helps-van-gogh-museum-sieve-through-visitor-feedback?utm_source (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Levere, J.L. (2018). Artificial Intelligence, Like a Robot, Enhances Museum Experiences. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/25/arts/artificial-intelligence-museums.html (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Santini, T., Brinkmann, H., Reitstätter, L., Leder, H., Rosenberg, R., Rosenstiel, W., & Kasneci, E. (2018). The art of pervasive eye tracking: unconstrained eye tracking in the Austrian Gallery Belvedere. In Proceedings of the 7th Workshop on Pervasive Eye Tracking and Mobile Eye-Based Interaction (PETMEI '18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 5, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Garbutt, M., East, S., Spehar, B., Estrada-Gonzalez, V., Carson-Ewart, B., & Touma, J. (2020). The embodied gaze: exploring applications for Mobile Eye Tracking in the art museum. Visitor Studies, 23(1), 82-100. [CrossRef]

- Reitstätter, L., Brinkmann, H., Santini, T., Specker, E., Dare, Z., Bakondi, F., Miscená, A., Kasneci, E., Leder, H., & Rosenberg, R. (2020). The Display Makes a Difference: A Mobile Eye Tracking Study on the Perception of Art before and after a Museum’s Rearrangement. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 13(2), 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R., Rudolph, C., & Roy-Chowdhury, A.K. (2015). Computerized Face Recognition in Renaissance Portrait Art: A quantitative measure for identifying uncertain subjects in ancient portraits. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 32, 85-94. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.P. (2017). How artificial intelligence could revolutionize museum research. Smithsonian Magazine. Available online:https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-artificial-intelligence-could-revolutionize-museum-research-180967065/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Oksanen, A., Cvetkovic, A., Akin, N., Latikka, R., Bergdahl, J., Chen, Y., & Savela, N. (2023). Artificial intelligence in fine arts: A systematic review of empirical research. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 1(2), Article 100004. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Zhang, P., Du, J., & Xu, Z. (2021). Painting and calligraphy identification method based on hyperspectral imaging and convolution neural network. Spectroscopy Letters, 54(9), 645–664. [CrossRef]

- Frank, S. J., & Frank, A. M. (2022). Complementing connoisseurship with artificial intelligence. Curator: The Museum Journal, 65(4), 835–868. [CrossRef]

- Rijksmuseum. (2022). Rijksmuseum Publishes 717-Gigapixel Photograph of “The Night Watch”. Available online: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/press/press-releases/rijksmuseum-publishes-717-gigapixel-photograph-of-the-night-watch (accessed on 24 Mai 2025).

- Engdahl, E. (2021). Past Forward. Activatint The Henry Ford Archive of Innovation: A Table of Digital Connections. The Henry Ford website. Available online: https://www.thehenryford.org/explore/blog/a-table-of-digital-connections (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Ohm, T. (2023). Algorithmic exhibition-making. Curating with networks and word embeddings. In S. Thiel & J. Bernhardt (Eds.), AI in Museums. Reflections, Perspectives and Applications (Edition Museum 74, 209-215). Transcript. [CrossRef]

- Nasher Museum. (2023). Behind the Scenes of an AI-generated Exhibition. Available online: https://nasher.duke.edu/stories/behind-the-scenes-of-an-ai-generated-exhibition/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Osterman, M (2024). Dreaming of AI: Transforming Museum Experiences. BPOC's Website [Video]. Youtube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yATltB9mjAw (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Rogers, J. (2024). AI art show shakes up perceptions of art and technology. University of Miami. Available online: https://news.miami.edu/as/stories/2024/04/ai-art-show-shakes-up-perceptions-of-art-and-technology.html (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Engel, C. & Mangiafico P. & Issavi, J. & Lukas, D. (2019). Computer vision and image recognition in archaeology. In Proceedings of the Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Data Discovery and Reuse (AIDR '19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 5, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Fuchsgruber, L. (2023). Dead End or Way Out? Generating Critical information about painting collections with AI. In S. Thiel & J. Bernhardt (Eds.), AI in Museums. Reflections, Perspectives and Applications (Edition Museum 74, pp 65-72). Transcript. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553), 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R., Hussain, M., Hill, R., & Allen, P. (2024). A Comprehensive Review of Convolutional Neural Networks for Defect Detection in Industrial Applications. IEEE Access, 12, 94250-94295. [CrossRef]

- Wen, J., Ma, B. (2024). Enhancing museum experience through deep learning and multimedia technology. Heliyon 10(12). e32706. [CrossRef]

- Bunz, M. (2023). The Role of Culture in the Intelligence of AI. In S. Thiel & J. Bernhardt (Eds.), AI in Museums. Reflections, Perspectives and Applications (Edition Museum 74, pp 23-29). Transcript. [CrossRef]

- Boztas, S. (2024). Rijksmuseum launches AI tool to help make connections in 800,000-strong collection. The “art explorer” project allows the Dutch museum's vast holdings to be more searchable. The Art Newspaper. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/11/29/rijksmuseum-takes-first-steps-in-ai-to-help-make-connections-in-800000-strong-collection (accessed on 30 Mai 2025).

- Rijksmuseum. (2025). Art Explorer. Available online: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/kunstverkenner (accessed on 24 Mai 2025).

- Harvard Art Museums. (2025). Explore. AI at Harvard Art Museums. Available online: https://ai.harvardartmuseums.org/explore (accessed on 31 Mai 2025).

- Ciecko, B. (2020). AI Sees What? The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Machine Vision for Museum Collections. MW20:MW2020. Available online: https://mw20.museweb.net/paper/ai-sees-what-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly-of-machine-vision-for-museum-collections/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Robinson, S. (2017). When art meets big data: Analyzing 200,000 items from The Met collection in BigQuery. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/gcp/when-art-meets-big-data-analyzing-200000-items-from-the-met-collection-in-bigquery (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Choi, J. (2020). Engaging the Data Science Community with Met Open Access API. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/met-api-computer-learning (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Bobasheva, A., Gandon, F., & Precioso, F. (2022). Learning and reasoning for cultural metadata quality: Coupling symbolic AI and machine learning over a semantic web knowledge graph to support museum curators in improving the quality of cultural metadata and Information Retrieval. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 15(3), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Nasjonalmuseet. (2023). Semantic search in an online collection. Nasjonalmuseet beta. Available online: https://beta.nasjonalmuseet.no/2023/08/add-semantic-search-to-a-online-collection/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Barandy, K. (2020). MIT develops MosAIc algorithm to find hidden connections between art across cultures. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/art/mit-csail-mosaic-algorithm-art-hidden-connections-08-10-2020/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- MoMA. (n.d.). Identifying art through machine learning. The Museum of Modern Art. Available online: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/history/identifying-art (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Jones, B. (2018). Computers saw Jesus, graffiti, and selfies in this art, and critics were floored. Digital Trends. Available online: https://www.digitaltrends.com/computing/philadelphia-art-gallery-the-barnes-foundation-uses-machine-learning/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Fenstermaker, W. (2019). How Artificial Intelligence Sees Art History. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/articles/2019/2/artificial-intelligence-machine-learning-art-authorship (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Kessler, M. (2019). The Met x Microsoft x MIT:A Closer Look at the Collaboration. The Met Blog. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2019/met-microsoft-mit-reveal-event-video (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Schneider, T. (2019). The Gray Market: How the Met’s Artificial Intelligence Initiative Masks the Technology’s Larger Threats (and Other Insights). Artnet News. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/news/metropolitan-museum-artificial-intelligence-1461730 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Burghardt, S. (2023). Alt-ering the Art Institute of Chicago. Available online: https://blog.cogapp.com/alt-ering-the-art-institute-of-chicago-60317e4b5363 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Manovich, Lev. (1999). Avant-Garde as Software. Available online: https://manovich.net/index.php/projects/avant-garde-as-software (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Elliott, L. (2018). Mario Klingemann. Memories of Passersby I (Companion Version), 2018. Available online: https://daily.xyz/artwork/0x123456/2?originId=10061 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Anadol. R. (2022). Space in the Mind of a Machine: Immersive Narratives. Architectural Design, 92(3), 28-37. [CrossRef]

- MoMA (2022).Refik Anadol on AI, algorithms, and the machine as Witness. Magazine moma. Available online: https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/821 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Blanco, A.D., Kroupi, E., Soria-Frisch, A., Gazzaley, A., Anadol, R., Maiques, A., Ruffini, G. (2024). Exploring the Neural Impact of AI-Generated Art at MoMA: An EEG Study on Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised. [CrossRef]

- Boiano S., Borda A., Gaia G., Di Fraia, G. (2024). Ethical AI and Museums: Challenges and new directions. Proceedings of EVA London 2024 (EVA 2024).

- Varitimiadis, S., Kotis, K.I., Skamagis, A., Tzortzakakis, A., Tsekouras, G.E., & Spiliotopoulos, D. (2020). Towards implementing an AI chatbot platform for museums. International Conference on Cultural Informatics, Communication & Media Studies 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Merritt, E. (2018). IRIS part two: How to embed a museum’s personality and values in AI. American Alliance of Museums. Available online: https://www.aam-us.org/2018/06/19/iris-part-two-how-to-embed-a-museums-personality-and-values-in-ai/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Morena, D. (2018). IRIS+ Part One: Designing + Coding a Museum AI. American Alliance of Museums website. Available online: https://www.aam-us.org/2018/06/12/iris-part-one-designing-coding-a-museum-ai/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Noh, Y.-G., & Hong, J.-H. (2021). Designing Reenacted Chatbots to Enhance Museum Experience. Applied Sciences, 11(16), 7420. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. (2024). Enhancing art museum experience with a chatbot tour guide (Master's thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology). DiVA Portal. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1885513/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Museums of the City of Paris. (2018). Chatbot: Paris Musées launches a conversational interface to direct visitors. Available online: https://www.parismusees.paris.fr/en/news/chatbot-paris-musees-launches-a-conversational-interface-to-direct-visitors (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Nunez, C. (2021). Making an art collection browsable by voice. Available online: https://www.amazon.science/latest-news/art-institute-of-chicago-alexa-conversations-art-museum-skill (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Gerber, K. (2018). Tour Akron Art Museum with Dot the Chatbot. Available online: https://www.theformgroup.com/articles/2018/10/17/tour-akron-art-museum-with-dot-the-chatbot (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- The Voice of Art. (2018). IBM Watson Video. Connexis Digital Mentors Channel. [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogpv984_60A (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Cecilia, A. (2022). The Voice of Art: IBM Watson Artificial Intelligence at a Brazilian Museum. Available online: https://anacecilia.digital/en/the-voice-of-art-ibm-watson-artificial-intelligence-at-a-brazilian-museum/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Vicelli, P., Kunsch, A., K. (2024). A Voz da Arte – Projeto de Inteligência Artificial feito em parceria com a IBM. Pinacoteca de São Paulo. Available online: https://pinacoteca.org.br/blog/bastidores/a-voz-da-arte-o-projeto-de-ia-entre-pina-e-ibm/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Gaia, G., Boiano, S., Borda, A. (2019). Engaging Museum Visitors with AI: The Case of Chatbots. In: Giannini, T., Bowen, J. (eds) Museums and Digital Culture. Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Case Museo Di Milano. (n.d.). Chat Game nelle case museo. Available online: https://casemuseo.it/chat-game-nelle-case-museo/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Ask Mona. (2024). Revolutionizing the Museum Experience: The Conversational Agent at MNBAQ. Available online: https://www.askmona.fr/en/article-revolutionizing-the-museum-experience-the-conversational-agent-at-mnbaq (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Raymond, M-H. (2024). The growing use of AI in museums and cultural venues. Available online: https://iatourisme.com/en/the-growing-use-of-ai-in-museums-and-cultural-venues/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Asharq Al-Awsat. (2024). Parisian Museums Use AI, Immersive Tech to Lure Young Audience. Available online: https://english.aawsat.com/culture/4821701-parisian-museums-use-ai-immersive-tech-lure-young-audience (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Deakin, T. (2022). A Conversational AI Guide at Centre Pompidou. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/a-conversational-ai-guide-at-centre-pompidou/?utm_source (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Open AI. (2024). Collaborating with The Met to Awaken “Sleeping Beauties” with AI. Available online: https://openai.com/index/the-met-museum/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- The Met. (2024). Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion. Available online: https://chatnataliepotter.metmuseum.org/visit (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Prelević, I.,S., Zehra, Z. (2023). Aesthetics of deepfake – Sphere of art and entertainment industry. Facta Universitatis, Series: Visual Arts and Music, 9(2), 87–100. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. (2019). Deepfake Salvador Dalí takes selfies with museum visitors. It’s surreal, all right. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/10/18540953/salvador-dali-lives-deepfake-museum (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Richardson, J. (2019). Art meets Artificial Intelligence as museum resurrects Salvador Dalí. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/dali-lives-art-meets-artificial-intelligence/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Mihailova, M. (2021). To Dally with Dalí: Deepfake (Inter)faces in the Art Museum. Convergence, 27(4), 882-898. [CrossRef]

- Boucheyras, T. (2024). Grâce à l'intelligence artificielle, cette entreprise permet de discuter avec des personnages historiques. https://france3-regions.franceinfo.fr/grand-est/bas-rhin/strasbourg-0/grace-a-l-intelligence-artificielle-cette-entreprise-permet-de-discuter-avec-des-personnages-historiques-2900885.html.

- Open Culture. (2024). “Hello Vincent”: A Generative AI Project Brings Vincent Van Gogh to Life at the Musée D’Orsay. Available online: https://www.openculture.com/2024/02/hello-vincent.html?utm_source (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Louvre Shop. (n.d.). Available online: https://boutique.louvre.fr/en/ (accessed on 17 Mai 2025).

- V&A Shop. (2025). Victoria and Albert Museum. Available online: https://www.vam.ac.uk/shop (accessed on 30 Mai 2025).

- The MET store. (2025). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available online: https://store.metmuseum.org/ (accessed on 30 Mai 2025).

- Kosmopoulos, D., & Styliaras, G. (2018). A survey on developing personalized content services in museums. Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 47, 54–77. [CrossRef]

- Dossis, M.F., Kazanidis, I., Valsamidis, S.I., Kokkonis, G., Kontogiannis, S. (2018). Proposed open source framework for interactive IoT smart museums. In Proceedings of the 22nd Pan-Hellenic Conference on Informatics (PCI '18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 294–299. [CrossRef]

- Frost, S., Thomas, M.M., & Forbes, A.G. (2019). Art I Don’t Like: An Anti-Recommender System for Visual Art. MW19:MW2019. Available online: https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/art-i-dont-like-an-anti-recommender-system-for-visual-art/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- TBIH. IMAGINES. (2024). Media Museum at Sound & Vision. [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9XTHYKCTXPc (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- SEGD (Society for Experiential Graphic Design), 2023. MIT Museum. Available online: https://segd.org/projects/mit-museum/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Deakin, T. (2023). This New Museum In The Netherlands Has Embraced Gamification For Learning. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/new-museum-gamification-for-learning/?utm (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC). (2023). BSC and Prado Museum teach AI to view and interpret works of art. Available online: https://www.bsc.es/news/bsc-news/bsc-and-prado-museum-teach-ai-view-and-interpret-works-art (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- HPC. (2023). BSC and Prado Museum Teach AI to View and Interpret Works of Art. Available online: https://www.hpcwire.com/off-the-wire/bsc-and-prado-museum-teach-ai-to-view-and-interpret-works-of-art/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Sha, Y., Zhang, S., Feng, T., & Yang, T. (2021). Research on the intelligent display of cultural relics in smart museums based on intelligently optimized Digital Images. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2021(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., & Yezhova, O. (2024). Strategy of design online museum exhibition contents from the perspective of artificial intelligence. Art and Design, (2), 80–89. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, Y., Preiß, C. (2023). Say the Image, Don’t Make It. Empowering human-AI co-creation through the interactive installation Wishing Well. In S. Thiel & J. Bernhardt (Eds.), AI in Museums. Reflections, Perspectives and Applications (Edition Museum 74, pp 245-255). Transcript. [CrossRef]

- MIT Museum. (2022). New MIT Museum Opens to the Public October 2, 2022. Available online: https://mitmuseum.mit.edu/announcements/press-release-september-8-2022 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Shi, W. (n.d.) AI: Mind the Gap. Available online: https://shi-weili.com/ai-mind-the-gap (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Bluecadet. (n.d.) Essential MIT. Available online: https://www.bluecadet.com/work/mit-museum (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Hewitt, D. (2023). The MIT Museum’s Collaborative Poetry: Co-Creating Verses with AI. Available online: https://thenextarchives.com/ideas/the-mit-museums-collaborative-poetry-co-creating-verses-with-ai/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Timeline. (2024). Tech That Animates Drawings With AI At Dubai Art Museum. [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=id2ydJUCPes (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Tathastu Buddy. (2024). Revolutionizing Art: Dubai Museum Showcases Stunning AI-Driven Paintings and Animations. Where Creativity Meets Technology: Explore the Future of Art Through AI Innovations. Available online: https://www.tathastulifestyle.com/tecnology-in-art/revolutionizing-art-dubai-museum-showcases-stunning-ai-driven-paintings-and-animations/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Consultancy.eu. (2021). Magnus helps Van Gogh Museum launch a WeChat app. Available online: https://www.consultancy.eu/news/6611/magnus-helps-van-gogh-museum-launch-a-wechat-app (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Charr, M. (2024). How AI and a Superstar DJ are Transforming Visits at the Museum Barberini. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/how-ai-and-a-superstar-dj-are-transforming-museum-visits-at-the-museum-barberini/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Museum Barberini, Potsdam. (2025). The Museum Barberini Celebrates 150 Years of Impressionism. Available online: https://www.museum-barberini.de/en/mediathek/15875/the-museum-barberini-celebrates-150-years-of-impressionism (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Derda, I., Predescu, D. (2025): Towards humancentric AI in museums: practitioners’ perspectives and technology acceptance of visitor-centered AI for value (co-)creation. Museum Management and Curatorship, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Grba, D. (2022). Deep Else: A Critical Framework for AI Art. Digital 2 (1): 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Hajri, O. (2023). The hidden costs of AI. Decolonization from practice back to theory. In S. Thiel & J. Bernhardt (Eds.), AI in Museums. Reflections, Perspectives and Applications (Edition Museum 74, pp 57-64). Transcript. [CrossRef]

- Gillard, A., Levy, C.F., Nannini, L., Gåtam, N., King, A., Tylstedt, B., Upadhyaya, N. (2024). Living with AI – Critical Questions for the Social Sciences and Humanities: Reboot: Ethical AI Through a Behavioral Lens. 2023 WASP-HS Conference. Available online: https://framerusercontent.com/assets/qfNomBmpxNQfXH00CnehKOk5hH0.pdf (accessed on 15 Mai 2025).

- Sterling, C. (2024). Museums after progress. Museums & Social Issues, 18(1–2), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- ICOM-OECD. (2019). Culture and local development: Maximizing the impact. Guide for local governments, communities and museums. Available online: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/ICOM-OECD-GUIDE_EN_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- ICOM (2022). ICOM approves a new museum definition. International Council of Museums. Available online: https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-approves-a-new-museum-definition/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Cameron, D. (2004). The museum, a temple or the forum. In G. Anderson (Ed.), Reinventing the museum: Historical and contemporary perspectives on the paradigm shift (pp. 61–73). Altamira Press. Available online: https://www.elmuseotransformador.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/The-Museum-A-Temple-or-the-forum.pdf (accessed on 10 Mai 2025).

- Hite, R., Childers, G., Hoffman, J. (2024). Cultural-historical activity theory as an integrative model of socioscientific issue based learning in museums using extended reality technologies. Int J Sci Educ Part B. 2024:1-6. [CrossRef]

- Avlonitou, C, Papadaki, E and Kavoura, A. (2025). How Smart Can Museums Be? The Role of Cutting-Edge Technologies in Making Modern Museums Smarter . F1000Research 2025, 14:480. [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L., Cowls, J., Beltrametti, M. et al. (2018). AI4People—An Ethical Framework for a Good AI Society: Opportunities, Risks, Principles, and Recommendations. Minds & Machines 28, 689–707. [CrossRef]

- IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems. (2019). Ethically Aligned Design: A vision for prioritizing human well-being with autonomous and intelligent systems (First Edition). IEEE Standards Association. Available online: https://standards.ieee.org/content/ieee-standards/en/industry-connections/ec/autonomous-systems.htm (accessed on 30 Mai 2025).

- Unesco. (2021). Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. The Recommendation. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- European Parliament, (2023). EU AI Act: first regulation on artificial intelligence. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20230601STO93804/eu-ai-act-first-regulation-on-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Leslie, D., Rincón, C., Briggs, M., Perini, A.,Jayadeva, S., Borda, A., Bennett, SJ. Burr, C.,Aitken, M., Katell, M., Fischer, C., Wong, J., and Kherroubi G. I. (2023). AI Fairness in Practice.The Alan Turing Institute. [CrossRef]

- MA. Museum Association. (2024). Guide An ethical approach to AI. Available online: https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/in-practice/2024/05/guide-an-ethical-approach-to-ai/# (accessed on 17 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).