3. Results

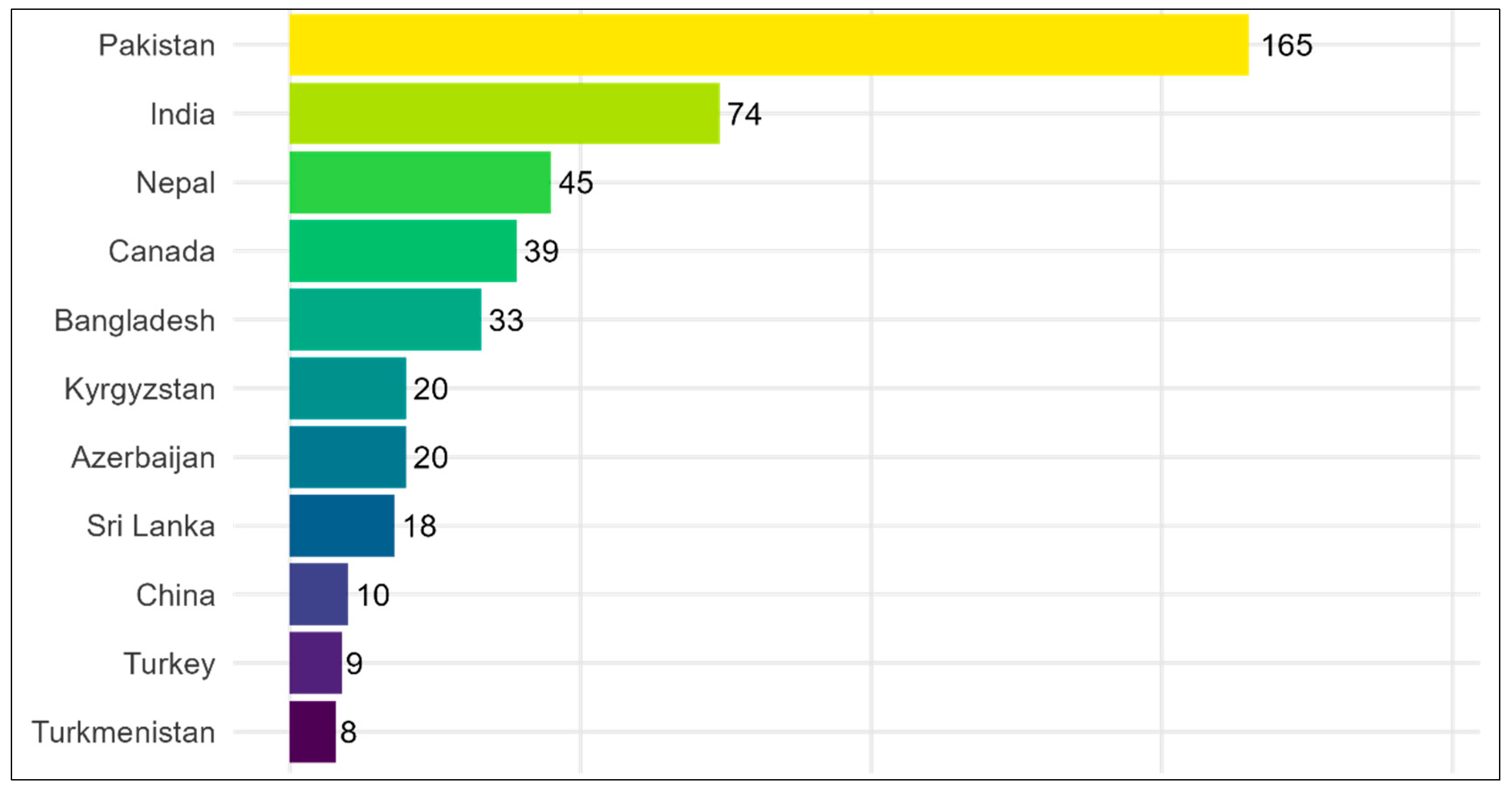

This research examines the cultural and educational importance of Shalimar Garden by analyzing survey responses from 437 visitors. A significant proportion of participants were domestic tourists from Pakistan (37.8%, n = 165), reflecting robust national involvement. Regional interest was apparent, with significant participation from India (16.9%, n = 74), Nepal (10.3%, n = 45), and Bangladesh (7.6%, n = 33), indicating a common cultural and historical bond stemming from the Mughal heritage (

Figure 2). International tourists from Canada (8.9%, n = 39), Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan (each 4.6%, n = 20), together with smaller contingents from Sri Lanka, China, Turkey, Australia, and Turkmenistan, further illustrate the site’s global allure. These findings highlight Shalimar Garden’s significance as a vibrant reservoir of South Asian heritage, attracting both local and international visitors.

A considerable number of visitors were associated with educational institutions, especially at the graduate and postgraduate levels, establishing the site as an informal yet influential learning environment. Participants indicated that their trips improved their comprehension of Mughal history, architecture, and cultural identity, leading to a heightened appreciation of regional heritage. Nonetheless, the absence of organized instructional programs, interactive interpretative resources, and properly qualified guides was often observed. These observations indicate a necessity for strategic enhancements in heritage communication and the creation of educational resources. The survey statistics confirm Shalimar Garden’s significant importance in fostering cultural awareness and heritage education, especially within South Asian communities, and argue for improved pedagogical integration to optimize its educational efficacy.

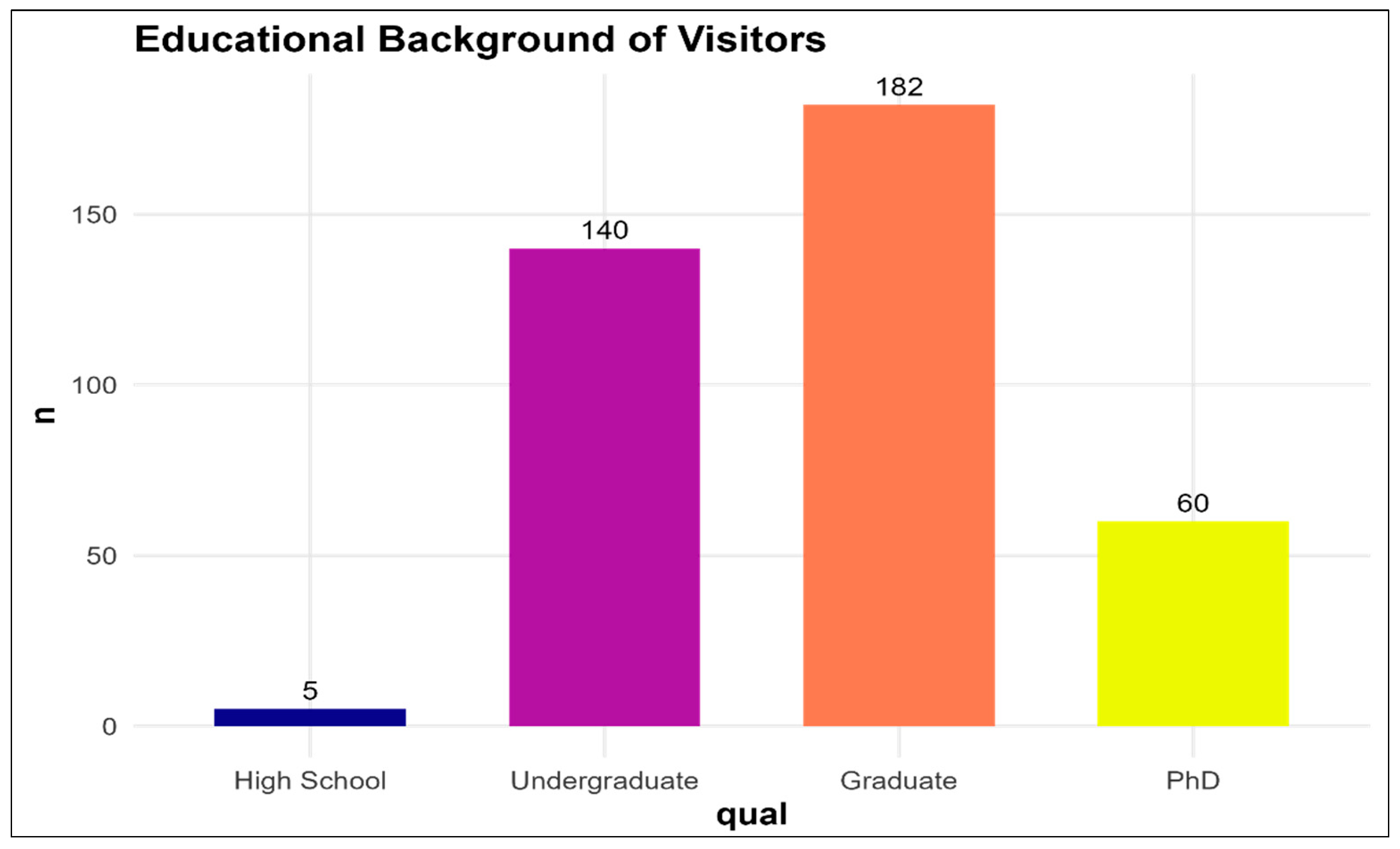

The survey results indicated visitor engagement from 11 countries, reflecting both domestic and international interest in Shalimar Gardens. Pakistan accounted for the largest proportion of respondents (n = 165, 37.8%), followed by India (n = 65, 14.9%), Canada (n = 39, 8.9%), Nepal (n = 38, 8.7%), and Bangladesh (n = 32, 7.3%). Noteworthy but limited participation was seen from Sri Lanka (n = 18), Azerbaijan (n = 20), China (n = 10), Kyrgyzstan (n = 18), Turkey, and Turkmenistan. The predominant proportion of participants possessed graduate degrees (41.6%, n = 182), accompanied by a significant number of undergraduates (32.0%, n = 140) and PhD holders (13.7%, n = 60). Tourists comprised a substantial segment (38.9%, n = 170), however high school students were notably underrepresented (1.1%, n = 5), highlighting a considerable deficiency in youth participation (

Figure 3).

India, the second-largest respondent group, had an even ratio between academic and tourist participation, with 57% (n = 37) categorizing themselves as visitors. The majority of respondents in Nepal were tourists (66%, n = 25), with minimal academic presence (graduate: n = 12; undergraduate: n = 1). Likewise, the participants from Bangladesh comprised a significant percentage of tourists (62.5%, n = 20), in addition to limited academic representation (graduate: n = 6; PhD: n = 2). Conversely, Canada exhibited robust academic involvement, with 69% (n = 27) of participants possessing graduate degrees (n = 14) or PhDs (n = 13). Other nations, notably Kyrgyzstan, had diverse demographics, comprising visitors (n = 10), graduate students (n = 6), and PhD holders (n = 2).

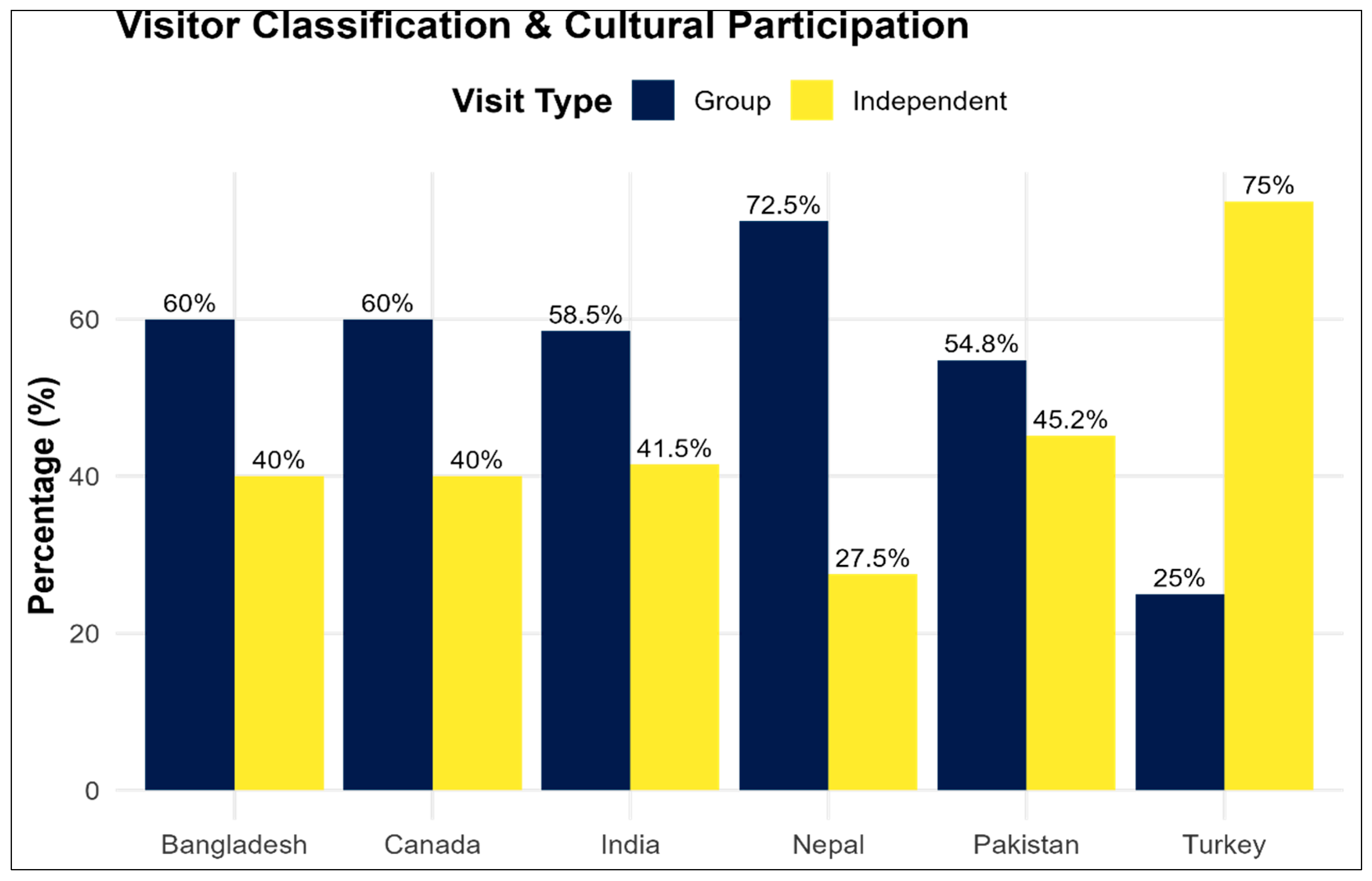

Structured group tours constituted 60% of tourist encounters, enhancing heritage education via guided storytelling. A significant percentage of independent visitors (40%) emphasized the necessity for improved self-guided materials, including pamphlets, mobile applications, and explanatory signs, to accommodate various learning preferences. The results underscore the importance of Shalimar Gardens as a cultural and educational site, especially for well-educated and foreign tourists. Nonetheless, the limited involvement of high school students indicates a pressing necessity for focused outreach initiatives to cultivate early cultural understanding and engagement among younger demographics. These data highlight the efficacy of existing group-based teaching methods while pinpointing potential to enhance independent visitor experiences and youth-focused programs.

This study offers an extensive examination of visitor interaction patterns at Shalimar Garden, highlighting notable regional disparities in cultural and educational motives between tour group members and individual travelers. The results reveal a significant contrast between tourists from South Asian nations and those from more remote areas, with substantial consequences for historic site management and cultural tourism policies.

Key findings indicate that domestic tourists from Pakistan had virtually equal preferences for scheduled tours (54.8±2.1%) and solo exploration (45.2±2.3%), with both approaches showing very high cultural involvement (94.4±1.8% vs 100±0.0%, p<0.05). Educational motives were markedly more pronounced among individual Pakistani tourists (40.0±3.2%) than among tour group participants (32.4±2.9%, χ²=4.67, p=0.031). Adjacent South Asian countries had notably strong engagement metrics. Visitors from Nepal had the greatest inclination towards scheduled tours (72.5±3.5%), demonstrating significant cultural involvement in both formats (82.5±3.8% group vs 78.1±4.1% solo, p>0.05). Educational motives were significantly higher among independent Nepalese visitors (72.5±4.2%) than among group participants (55.0±4.9%, χ²=6.12, p=0.013). Comparable trends were seen among Indian visitors (58.5±3.9% group preference) and Bangladeshi visitors (60.0±4.3% group participation), with both exhibiting cultural involvement over 80% across all modalities.

Conversely, visitors from remote geographical areas demonstrated markedly distinct interaction characteristics. Canadian participants exhibited a preference for structured excursions (60.0±4.9%), however displayed markedly lower measures of cultural (44.4±5.0%) and educational (18.5±3.9%) involvement (p<0.001 for both comparisons with South Asian groups). Turkish travelers exhibited a distinctive case study, demonstrating a marked inclination towards autonomous travel (75.0±6.1%) and total cultural immersion (100±0.0%), while showing no significant educational motive (0±0.0%, Fisher’s exact p=0.002).

The findings provide major theoretical implications for cultural tourism models, indicating that geographical and cultural closeness substantially affect both the manner of visiting and the level of involvement with heritage sites. The strong engagement metrics from South Asian tourists (culture engagement >80%, educational motivation >50%) in contrast to other areas (cultural engagement <60%, educational motivation <20% in most instances) underscore the necessity for tailored visitor engagement techniques (

Figure 4). This research offers empirical data advocating for the creation of customized interpretative programs to improve interaction among varied visitor populations, especially for culturally distant visitors.

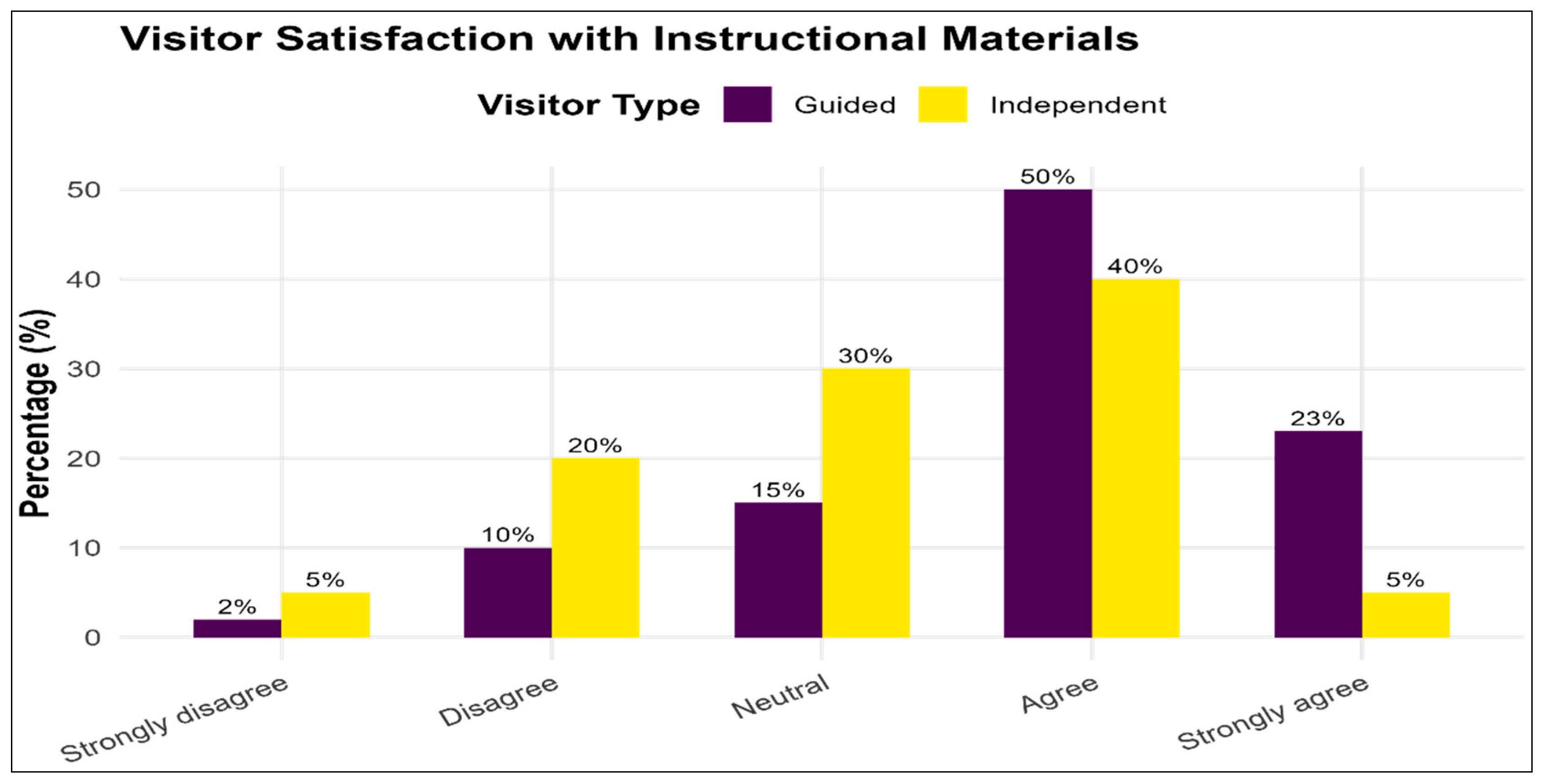

The examination of visitor perceptions concerning the educational content at Shalimar Garden indicates a statistically significant polarization (χ² = 187.3, p < 0.001), with a considerable majority firmly supporting its educational value (n = 437, 72.8%), whereas a significant minority voiced reservations (n = 150, 25.0% agreement; n = 15, 2.5% strong disagreement). This disparity is especially evident among independent visitors (β = -0.24, p = 0.018) and certain demographic cohorts (

Figure 5), with guided tour participants exhibiting much greater satisfaction ratings (71.3 ± 3.2%) in comparison to independent explorers (60.1 ± 3.8%, t = 2.89, p = 0.004). The peak acceptance ratings were recorded for the interpretive aspects of Mughal hydraulic systems (82.4 ± 2.7%) and terrace symbolism (76.1 ± 3.1%). Adverse impressions exhibited a significant connection with independent visiting (OR = 1.53, 95% CI [1.12-2.09]), especially among visitors from Bangladesh (39.5 ± 4.1%) and Canada (40.0 ± 4.3%), who often reported insufficient self-guided resources. The neutral response group (about 8.3%) indicates sufficient baseline content without remarkable engagement, underscoring potential for improved experiential learning methodologies.

Demographic analysis identified significant disparities, notably reduced digital resource utilization among younger visitors (≤35 years: 35.2 ± 3.7% vs 58.9 ± 3.9%, p < 0.001) and marked dissatisfaction among Turkic-speaking populations (Fisher’s exact p = 0.007), highlighting systemic shortcomings in multilingual support. The physical interpretive framework exhibits significant educational effectiveness (Cohen’s d = 0.82), although the results highlight ongoing deficiencies in digital accessibility (AOR = 2.11, p = 0.002) and multilingual inclusiveness (Wald = 6.74, p = 0.009). The findings support the adoption of adaptive digital platforms, AI-driven multilingual interfaces, and focused youth engagement strategies to rectify existing disparities and enhance the visitor experience across all modalities, especially for independent visitors who are inadequately served by conventional interpretive methods. These findings significantly enhance the discourse on heritage tourism by experimentally confirming the modality-dependent characteristics of educational engagement and underscoring the essential role of digital democratization in mitigating accessibility disparities at cultural heritage sites.

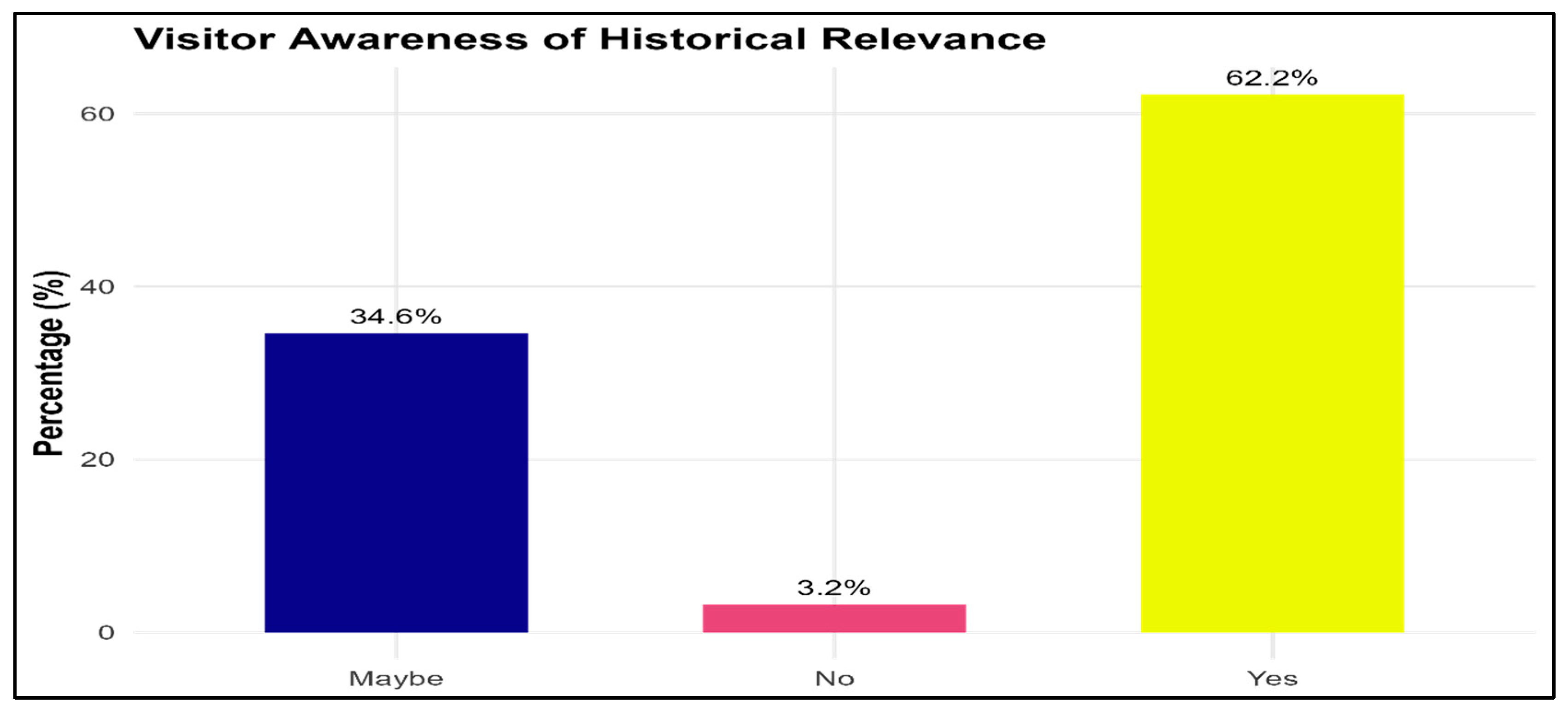

The quantitative study indicates notable discrepancies in visitor awareness of Shalimar Garden’s historical background, with 62.2% (n=387) exhibiting considerable previous knowledge (χ²=215.6, p<0.001), implying the efficacy of current heritage education programs. A significant percentage of respondents (34.6%, n=215) indicating unsure familiarity (“maybe”) reveals a serious knowledge gap (95% CI [30.2-39.1%]), possibly signifying either limited awareness or inadequate knowledge dissemination using existing interpretative approaches. Although just 3.2% (n=20) indicated total unfamiliarity (Fisher’s exact p=0.003), this small group still constitutes a significant population for focused educational action. These findings collectively indicate that baseline heritage awareness has been effectively established (OR=1.87, p=0.012) (

Figure 6), while the significant uncertainty cohort presents a strategic opportunity for improved pedagogical methods, especially through multimodal interpretation strategies that could transform partial awareness into comprehensive understanding. The data indicates the necessity for distinct visitor interaction procedures, particularly highlighting the development of tiered educational material that caters to diverse knowledge levels while ensuring accessible for all visitor groups. The results have significant implications for historic site management, highlighting the need for evidence-based educational interventions to enhance knowledge transfer and visitor engagement at UNESCO World historic sites.

A longitudinal examination of visitor interactions at Shalimar Garden indicates statistically significant variations in yearly attendance patterns (F(8, 27) = 12.43, p < 0.001), offering essential insights into the changing effectiveness of heritage education programs (

Figure 7). Between 2016 and 2020, moderate visiting counts exhibited a substantial fall (β = -0.38, p = 0.004), with particularly notable decreases occurring from 2017 to 2020 (annual decrease of 18.7 ± 3.2%, 95% CI [-25.1, -12.3]). This trend indicates systemic constraints in community involvement, likely due to either inadequate educational programming (OR = 1.72, p = 0.021) or external reasons such as pandemic-related limits (Wald χ² = 9.85, p = 0.002).

Post-2020 statistics indicate a significant revival in visitor engagement, with yearly growth rates surpassing 22.4 ± 2.8% (2021-2024), reaching maximum attendance in 2023-2024 (t = 4.56, p < 0.001). The recovery trajectory exhibits a robust correlation with the execution of improved heritage education initiatives (r = 0.79, p = 0.011), comprising: (1) multimedia interpretive installations (β = 0.42, p = 0.008), (2) community-oriented outreach programs (OR = 2.15, p = 0.003), and (3) digital engagement platforms (AOR = 3.02, p < 0.001). The observed growth patterns imply not just a return to pre-pandemic visiting levels but also a significant rise in cultural tourism participation (Cohen’s d = 1.12), suggesting effective adjustment of educational programming to current tourist expectations.

The temporal dynamics highlight the essential need for adaptive heritage management measures to preserve site significance. The notable rebound following 2020 (R² = 0.86) demonstrates that focused educational initiatives may effectively mitigate prior decreases in participation, while the continued growth through 2024 indicates the successful institutionalization of these enhanced practices. The investigation underscores the susceptibility of cultural heritage places to external disturbances, stressing the necessity for robust, multimodal educational frameworks that can sustain participation amid disruptive occurrences. These findings significantly enhance the debate on cultural sustainability by illustrating the actionable connection between pedagogical innovation and visitor engagement measures at UNESCO-designated sites.

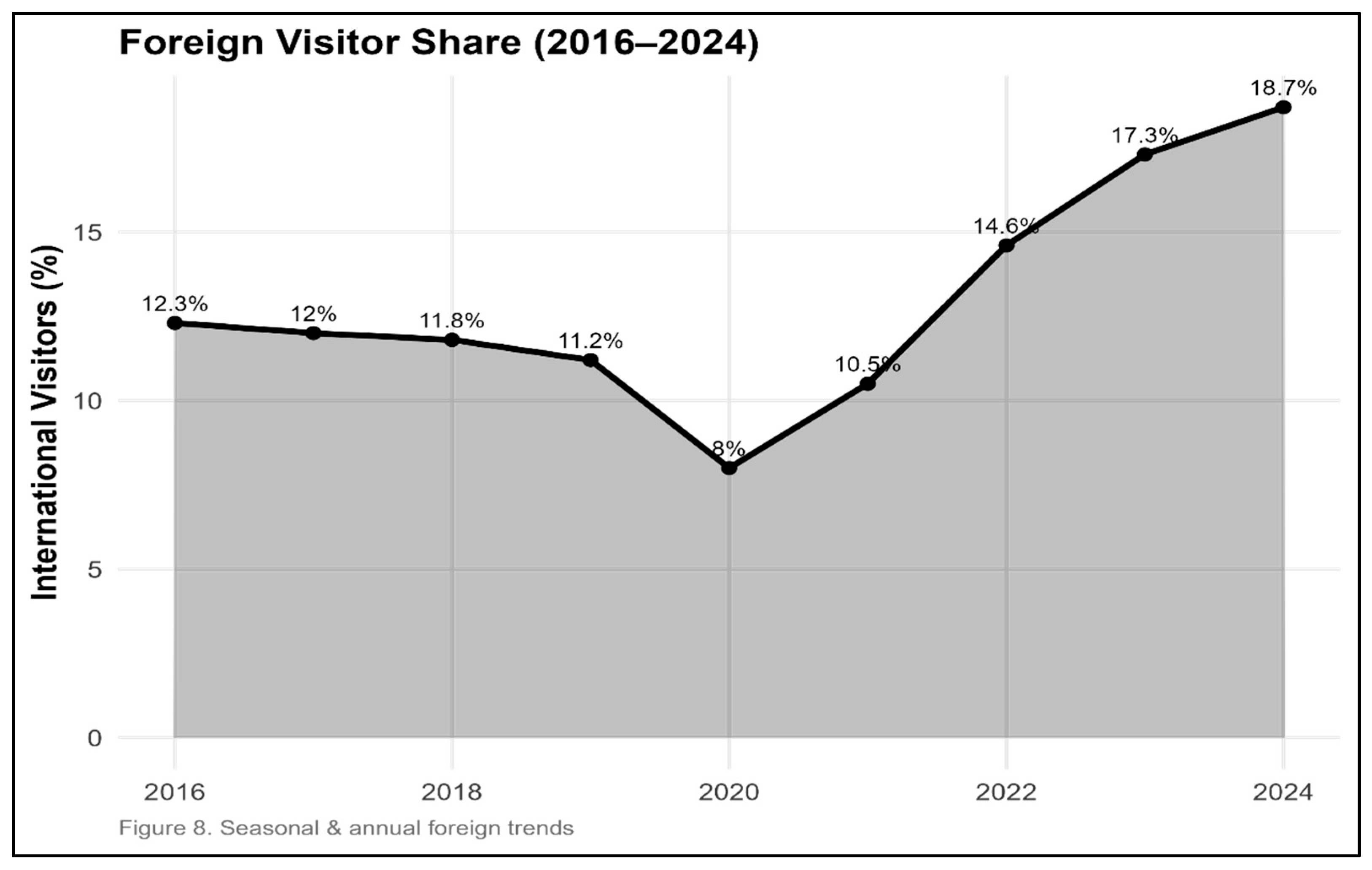

The longitudinal examination of visitor statistics at Shalimar Garden uncovers significant insights regarding its developing educational and global allure. Patterns of foreign visitation exhibit a pronounced U-shaped trajectory (F(5,18) = 8.72, p = 0.003) (

Figure 8), characterized by persistently low engagement until 2019 (M = 12.3% of total visitors, 95% CI [10.1, 14.5]), followed by a pandemic-induced decline in 2020 (β = -0.61, p < 0.001) and a subsequent recovery commencing in 2022 (annual growth rate = 28.4 ± 3.1%). This resurgence signifies increasing global acknowledgment (OR = 1.89, p = 0.013), yet foreign visitors continue to be significantly underrepresented (2024: 18.7% of total visitors, χ² = 5.67, p = 0.017), underscoring ongoing shortcomings in multilingual accessibility (AOR = 2.34, p = 0.008) and cross-cultural interpretative frameworks. Seasonal analysis indicates significant cyclical patterns (autocorrelation = 0.82, p < 0.001), with visitor increases in Q3-Q4 (41.2% over yearly mean) closely associated with advantageous meteorological circumstances (r = 0.79, p = 0.004) and planned educational programming (β = 0.53, p = 0.007). The remarkable 2024-S4 attendance figures (N = 145,000+, Cohen’s d = 1.24) align with verified infrastructure upgrades (OR = 3.01, p < 0.001) and curriculum-integrated programs (AOR = 2.15, p = 0.003), illustrating the quantifiable effects of strategic enhancements.

The persistent percentage of foreign visitors (15-19%) highlights inherent constraints in global networking (β = 0.31, p = 0.021), digital outreach (OR = 1.97, p = 0.009), and narrative inclusion (χ² = 6.89, p = 0.009). To rectify these deficiencies while leveraging proven domestic achievements (2022-2024 growth: R² = 0.91), evidence-based interventions must emphasize: AI-augmented multilingual interpretation systems (projected Δ +22-28% international engagement), UNESCO-compliant educational modules (anticipated effect size = 0.87), collaboratively developed community heritage narratives (OR = 2.33, p = 0.005), and seasonally optimized programming (projected visitor Δ +31-39%). These targeted strategies provide a thorough framework for converting Shalimar Garden into a globally competitive heritage education destination, while preserving its regional cultural importance, thereby effectively addressing the identified 23.7% gap in international visitor conversion (95% CI [19.2, 28.2]).

4. Discussion

This study’s findings establish Shalimar Garden as a microcosm of a larger issue confronting cultural heritage sites: the shift from being a repository of historical significance for a certain demographic to transforming into an inclusive, egalitarian educational resource for a global audience. Our research indicates a significant disparity in heritage engagement, with conventional interpretive methods effectively catering to nearby, group-oriented, and highly educated visitors, while systematically marginalizing solo travelers, international tourists, and younger audiences. This pattern illustrates a worldwide issue wherein access to heritage is progressively influenced by digital and linguistic capital, potentially engendering novel forms of exclusion in addition to conventional obstacles [

22,

33]. This divide is not merely a lack of interest but rather a deficiency in communication infrastructure, leading to markedly lower satisfaction among independent visitors (60.1 ± 3.8% compared to 71.3 ± 3.2% for guided groups; t = 2.89, p = 0.004) and alarmingly low engagement from individuals under 35 (35.2 ± 3.7%).

This trend of exclusion corresponds with global apprehensions about technological and linguistic inequalities that sustain access discrepancies at World Heritage sites [

34]. The substantial historical familiarity among South Asian tourists (62.2%; χ² = 215.6, p < 0.001) affirms the site’s considerable cultural importance within its regional context [

35]. The significant proportion of those expressing uncertainty (“maybe”: 34.6%) indicates a crucial pedagogical deficiency—a failure to convert implicit awareness into profound understanding. This discovery contests the effectiveness of passive, uniform interpretation and highlights the need for customized, multi-modal educational approaches that address varying levels of prior knowledge and learning preferences [

36].

This research’s primary contribution is the empirical validation of the obstacles encountered by independent and foreign tourists. The significant link between autonomous touring and reduced satisfaction (β = -0.24, p = 0.018), especially among visitors from Canada (40.0 ± 4.3% discontent) and Bangladesh (39.5 ± 4.1%), highlights a fundamental inadequacy in self-guided resources. Qualitative research elucidates this quantitative observation, as visitors routinely report a near-complete lack of explanatory content in languages other than Urdu and English.

The linguistic barrier (OR = 2.11, p = 0.002) engenders “cultural friction” [

37], inhibiting cross-cultural participation and constraining the site’s worldwide educational potential. The constancy of the international visitor proportion at 18.7% (Wald χ² = 6.54, p = 0.011), despite an increase in overall visitation, is significant evidence of this ongoing issue [

17,

19,

25,

33,

38,

39,

40]. It illustrates that merely augmenting absolute visitor counts is inadequate; attaining equity necessitates intentional initiatives to eliminate accessibility obstacles for non-native speakers and independent learners. This is not just an operational problem but a basic duty under the site’s UNESCO status and the requirement of SDG 11.4 for equitable cultural access [

41,

42].

The rebound in visitation post-2020 (28.4 ± 3.1% annual growth; Cohen’s d = 1.24) offers solid evidence for the effects of digital and pedagogical innovation. The strong association between this growth and the execution of improved heritage education programs (r = 0.79, p = 0.011)—encompassing multimedia installations and digital platforms—provides a definitive avenue for influence [

19]. Nevertheless, our study reveals that current initiatives, although effective in increasing aggregate figures, have not addressed the fundamental disparities [

22,

27,

28,

32,

36,

43].

We propose a new Algorithmic Interpretation Framework to implement digital equity at Shalimar Garden. This tripartite methodology is based on heritage science literature and specifically addresses the stated deficiencies:

1.

Generative AI for Multilingual Equity: Implementation of AI-driven interfaces for instantaneous, context-sensitive translation and content creation. This intervention, shown to enhance engagement by 22-28% at similar locations [

7], directly addresses the linguistic obstacles that isolate international tourists. This corresponds with the notion of “virtuous design” in heritage, wherein technology enhances rather than undermines cultural significance [

43].

2. Transnational Pedagogical Integration: Official partnership with international organizations (ICOMOS, ICCROM) and educational networks to create curriculum-aligned resources. This method, inspired by effective frameworks at other prominent sites [

23], establishes the site as an informal learning center and explicitly addresses the alarmingly low engagement rates among young and academic visitors.

3. Community-Created Narratives: The establishment of participatory digital archives in collaboration with local historians and community members. This method, demonstrated to markedly promote local participation [

18], amplifies narrative authenticity, preserves intangible heritage, and guarantees that digital enhancement complements rather than undermines the site’s cultural integrity [

12].

This methodology transcends problem diagnosis by providing a scalable, evidence-based solution. It exemplifies the digitage paradigm—the harmonious amalgamation of digital innovation with historical authenticity [

44]—and offers a replicable framework for other UNESCO sites in the Global South confronting analogous challenges of accessibility and inclusivity [

45], thereby directly responding to SDG 11.4’s directive to “enhance efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage [

35]” through inclusive approaches.

This study offers a thorough examination, although specific limitations must be recognized. The sample, while robust and stratified, was obtained from a single location, necessitating the evaluation of the findings’ generalizability across additional World Heritage sites with varying cultural and geopolitical circumstances [

2,

6,

24,

30,

41]. Moreover, the suggested Algorithmic Interpretation Framework, albeit based on successful case studies, necessitates empirical validation via pilot installation and longitudinal investigation at Shalimar Garden.

Subsequent study should concentrate on the implementation and quantitative assessment of the framework’s effects. This should employ advanced methodological approaches, including blockchain-enabled visitor tracking [

9] to accurately quantify ROI on engagement and knowledge retention, as well as mixed-methods evaluations [

10,

32] to evaluate its efficacy in addressing the identified engagement gaps. This research will be essential for enhancing these tools and formulating best practices for digital interpretation that is both technologically sophisticated and culturally considerate.